Elizabeth Rona on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth Rona (20 March 1890 – 27 July 1981) was a Hungarian nuclear chemist, known for her work with

Rona began her postdoctoral training in 1912 at the Animal Physiology Institute in Berlin and the

Rona began her postdoctoral training in 1912 at the Animal Physiology Institute in Berlin and the  When Hevesy left Budapest, in 1918

When Hevesy left Budapest, in 1918

Worldcat Publications Erzsébet Róna

Worldcat Publications Elisabeth Róna

Worldcat Publications Elizabeth Rona

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rona, Elizabeth 1890 births 1981 deaths Hungarian women chemists Hungarian chemists Hungarian educators Hungarian women educators 20th-century women scientists Eötvös Loránd University alumni Trinity Washington University faculty Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies faculty University of Miami faculty Jewish women scientists Manhattan Project people

radioactive isotopes

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transferr ...

. After developing an enhanced method of preparing polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic characte ...

samples, she was recognized internationally as the leading expert in isotope separation and polonium preparation. Between 1914 and 1918, during her postdoctoral study with George de Hevesy

George Charles de Hevesy (born György Bischitz; hu, Hevesy György Károly; german: Georg Karl von Hevesy; 1 August 1885 – 5 July 1966) was a Hungarian radiochemist and Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate, recognized in 1943 for his key rol ...

, she developed a theory that the velocity of diffusion depended on the mass of the nuclide

A nuclide (or nucleide, from nucleus, also known as nuclear species) is a class of atoms characterized by their number of protons, ''Z'', their number of neutrons, ''N'', and their nuclear energy state.

The word ''nuclide'' was coined by Truma ...

s. As only a few atomic elements had been identified, her confirmation of the existence of "Uranium-Y" (now known as thorium-231

Thorium (90Th) has seven naturally occurring isotopes but none are stable. One isotope, 232Th, is ''relatively'' stable, with a half-life of 1.405×1010 years, considerably longer than the age of the Earth, and even slightly longer than the gene ...

) was a major contribution to nuclear chemistry. She was awarded the Haitinger Prize The Haitinger Prize of the Austrian Academy of Sciences was founded in 1904 by the chemist and factory director, Ludwig Camillo Haitinger (1860–1945), who created the award in honor of his father, Karl Ludwig Haitinger. From 1905 to 1943 it was a ...

by the Austrian Academy of Sciences in 1933.

After immigrating to the United States in 1941, she was granted a Carnegie Fellowship

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world. Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establis ...

to continue her research and provided technical information on her polonium extraction methods to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Later in her career, she became a nuclear chemistry professor at the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies and after 15 years there transferred to the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Miami

The University of Miami (UM, UMiami, Miami, U of M, and The U) is a private research university in Coral Gables, Florida. , the university enrolled 19,096 students in 12 colleges and schools across nearly 350 academic majors and programs, ...

. At both Oak Ridge and Miami, she continued her work on the geochronology

Geochronology is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, whereas relative geochronology is p ...

of seabed elements and radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares t ...

. She was posthumously inducted into the Tennessee Women's Hall of Fame The Tennessee Women's Hall of Fame is a non-profit, volunteer organization that recognizes women who have contributed to history of the U.S. state of Tennessee.

History

The organization was founded and incorporated as a non-profit organization in ...

in 2015.

Early life and education

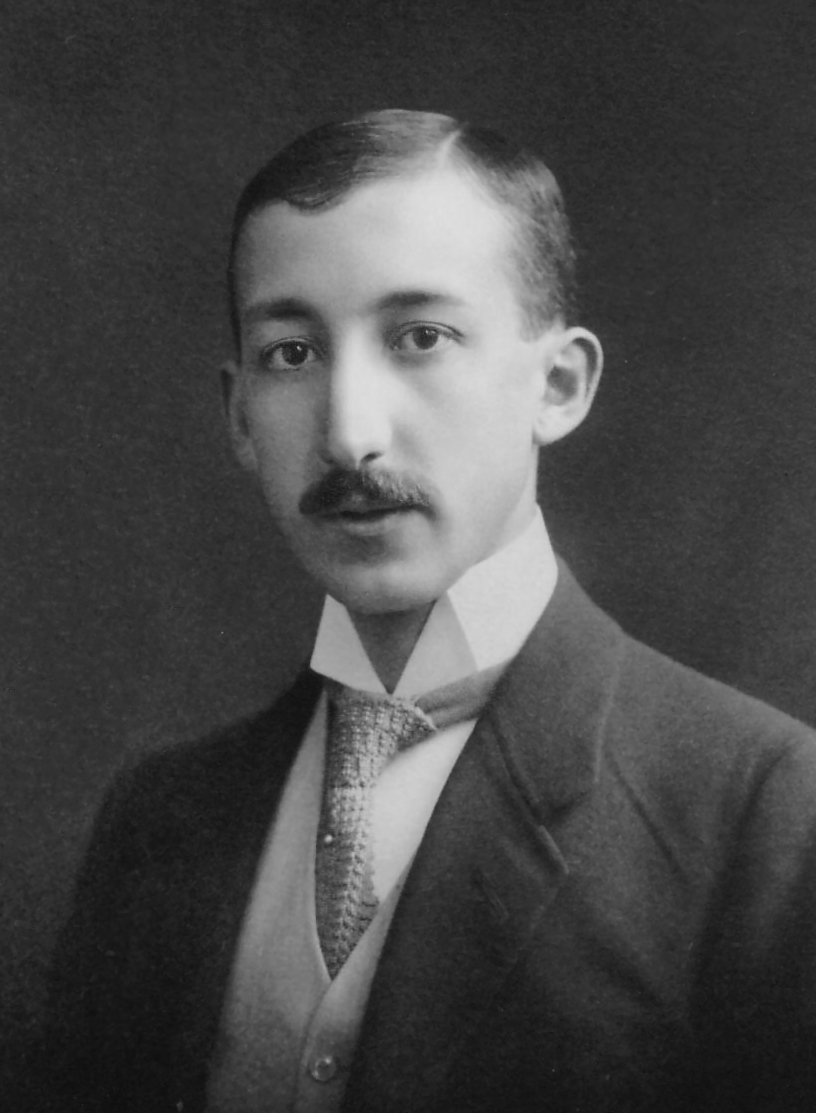

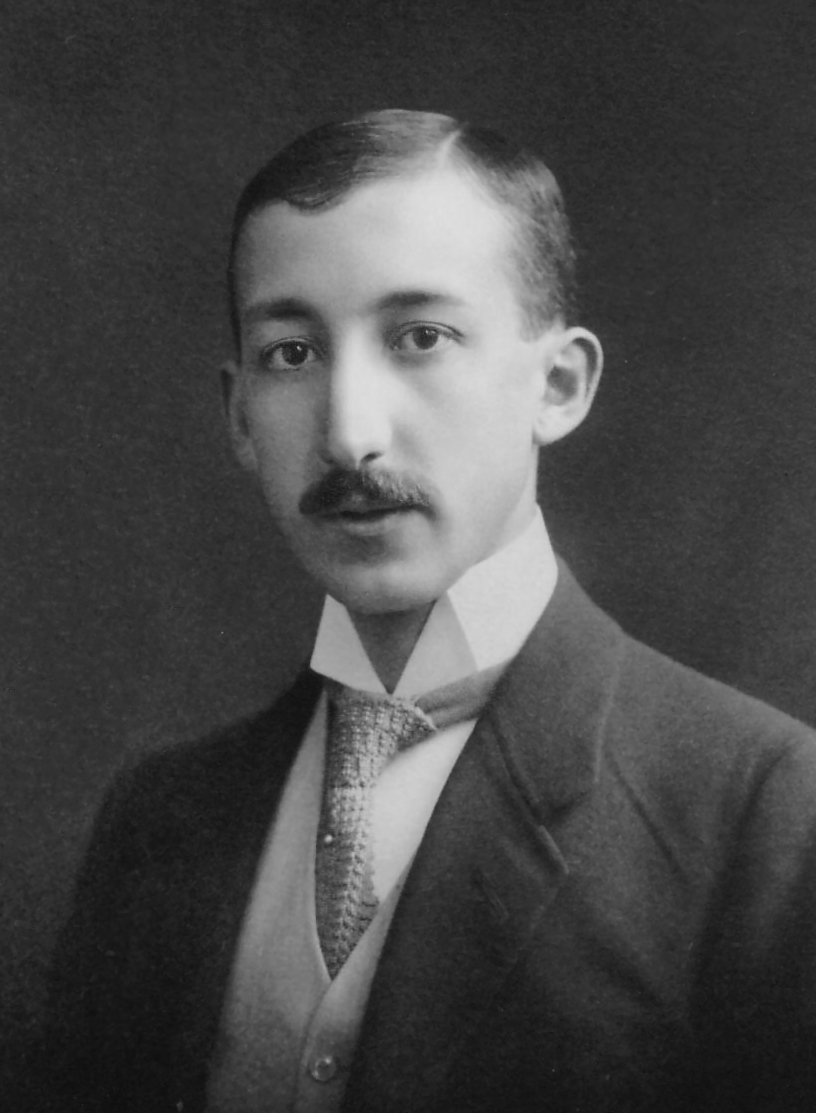

Elizabeth Rona was born on 20 March 1890 inBudapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Hungary, to Ida, (née Mahler) and Samuel Róna. Her father was a prosperous Jewish physician who worked with Louis Wickham and Henri-August Dominici, founders of radium therapy, to introduce the techniques to Budapest, and installed one of the first x-ray machines there. Elizabeth wanted to become a physician like her father, but Samuel believed that it would be too difficult for a woman to attain. Though he died when she was in her second year of university, Rona's father had encouraged her and spurred her interest in science from a young age. She enrolled in the Philosophy Faculty at the University of Budapest

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which ...

, studying chemistry, geochemistry, and physics, receiving her PhD in 1912.

Early career

Rona began her postdoctoral training in 1912 at the Animal Physiology Institute in Berlin and the

Rona began her postdoctoral training in 1912 at the Animal Physiology Institute in Berlin and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science ( German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over b ...

, studying yeast as a reagent. In 1913 she transferred to Karlsruhe University

The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT; german: Karlsruher Institut für Technologie) is a public research university in Karlsruhe, Germany. The institute is a national research center of the Helmholtz Association.

KIT was created in ...

, working under the direction of Kasimir Fajans

Kazimierz Fajans (Kasimir Fajans in many American publications; 27 May 1887 – 18 May 1975) was a Polish American physical chemist of Polish-Jewish origin, a pioneer in the science of radioactivity and the discoverer of chemical element protact ...

, the discoverer of isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass number ...

s, for the next eight months. During the summer of 1914, she studied at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

, but returned to Budapest at the outbreak of World War I. Taking a position at Budapest's Chemical Institute, she completed a scientific paper on the "diffusion constant of radon in water". Working with George de Hevesy

George Charles de Hevesy (born György Bischitz; hu, Hevesy György Károly; german: Georg Karl von Hevesy; 1 August 1885 – 5 July 1966) was a Hungarian radiochemist and Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate, recognized in 1943 for his key rol ...

, she was asked to verify a new element at the time was termed Uranium-Y, now known as Th-231. Though others had failed to confirm the element, Rona was able to separate the Uranium-Y from interfering elements, proving it was a beta emitter ( β-emission) with a half-life of 25 hours. The Hungarian Academy of Sciences

The Hungarian Academy of Sciences ( hu, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, MTA) is the most important and prestigious learned society of Hungary. Its seat is at the bank of the Danube in Budapest, between Széchenyi rakpart and Akadémia utca. Its mai ...

published her findings. Rona first coined the terms " isotope labels" and "tracers

Tracer may refer to:

Science

* Flow tracer, any fluid property used to track fluid motion

* Fluorescent tracer, a substance such as 2-NBDG containing a fluorophore that is used for tracking purposes

* Histochemical tracer, a substance used for t ...

" during this study, noting that the velocity of diffusion depended on the mass of the nuclides. Though contained in a footnote, this was the basis for the development of the mass spectrograph

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

ic and heavy water studies later performed by other scientists. In addition to her scientific proficiency, Rona spoke English, French, German, and Hungarian.

When Hevesy left Budapest, in 1918

When Hevesy left Budapest, in 1918 Franz Tangl

Franz Tangl (Budapest, January 26, 1866 – Budapest, December 19, 1917), was a Hungarian physiologist and pathologist, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Along with pathologist Paul Clemens von Baumgarten, the eponymous Baumgarten- ...

, a noted biochemist and physiologist of the University of Budapest, offered Rona a teaching position. She taught chemistry to selected students whom Tangl felt had insufficient knowledge to complete the course work, becoming the first woman to teach chemistry at university level in Hungary.

The apartment in which Rona and her mother were living was seized when the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

invaded Hungary in 1919. Owing to political instability and the persecution of those with communist sympathies during the countering White Terror

White Terror is the name of several episodes of mass violence in history, carried out against anarchists, communists, socialists, liberals, revolutionaries, or other opponents by conservative or nationalist groups. It is sometimes contrasted wit ...

, an increasing amount of work at the Institute fell to Rona. When offered a position in 1921 to return to Dahlem and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, by Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

, Rona resigned. She joined Hahn's staff in Berlin to separate ionium

Thorium (90Th) has seven naturally occurring isotopes but none are stable. One isotope, 232Th, is ''relatively'' stable, with a half-life of 1.405×1010 years, considerably longer than the age of the Earth, and even slightly longer than the gene ...

(now known as Th-230) from uranium. Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic

Hyperinflation affected the German Papiermark, the currency of the Weimar Republic, between 1921 and 1923, primarily in 1923. It caused considerable internal political instability in the country, the occupation of the Ruhr by France and Belgium ...

forced her transfer to the Textile Fiber Institute of Kaiser Wilhelm, as practical research was the only work permitted at the time. Theoretical research with no essential application was not a priority. Her training allowed her to return to a more stable Hungary and accept a position in a textile factory there in 1923. She did not care for the work and soon left, joining the staff of the Institute for Radium Research of Vienna in 1924 at the request of Stefan Meyer. Her research there focused on measuring the absorption and range of hydrogen rays, as well as on developing polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic characte ...

as an alternative radioactive material to radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rathe ...

.

Austria

As early as 1926, Meyer had written toIrène Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie (; ; 12 September 1897 – 17 March 1956) was a French chemist, physicist and politician, the elder daughter of Pierre and Marie Curie, and the wife of Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Jointly with her husband, Joliot-Curie was a ...

suggesting that Rona work with her to learn how his laboratory could make their own polonium samples. Once Hans Pettersson

Prof Hans Petterson FRSFor HFRSE RSAS (1888–1966) was a 20th century Swedish physicist and oceanographer.

Early life

Hans Petterson was born in Forshalla near Gothenburg on 26 August 1888, the son of the chemist and oceanographer Otto P ...

was able to secure funds to pay Rona's expenses, Joliot-Curie allowed her to come and study polonium separation at the Curie Institute in Paris. Rona developed an enhanced method of preparing polonium sources and producing alpha-emissions.( α-emission). Gaining recognition as an expert in the field, she took those skills back to the Radium Institute along with a small disc of polonium. This disc allowed her to create lab specimens of polonium, which were used in much of the Institute's subsequent research.

Her skills were in high demand and she formed many collaborations in Vienna, working with Ewald Schmidt

Ewald is a given name and surname used primarily in Germany and Scandinavia. It derives from the Germanic roots ''ewa'' meaning "law" and '' wald'' meaning "power, brightness". People and concepts with the name include:

Surnames

* Douglas Ewald ( ...

on the modification of Paul Bonét-Maury

Paul Albert Antoine Bonét-Maury (7 February 1900, Paris, 6th arrondissement, to 17 April 1972, 13th arrondissement) was an early French judoka, president of the Fédération française de judo, and a French radiobiologist.

Biography

Paul Bonét- ...

's method of vaporizing polonium; with Marietta Blau

Marietta Blau (29 April 1894 – 27 January 1970) was an Austrian physicist credited with developing photographic nuclear emulsions that were usefully able to image and accurately measure high-energy nuclear particles and events, significantly a ...

on photographic emulsions of hydrogen rays; and with Hans Pettersson. In 1928, Pettersson asked her to analyze a sample of sea bottom sediment to determine its radium content. Because the lab she was working in was contaminated, she took the samples to the oceanographic laboratory at Bornö Marine Research Station

Bornö Marine Research Station, owned by the Bornö Institute for Ocean and Climate Studies, is located at Holma on the island Stora Bornö in Gullmarsfjorden, about north of Gothenburg, Sweden. It was built in 1902 by and , both pioneers of Sw ...

on Stora Bornö Stora Bornö is an island in Gullmarn fjord, belonging to the Lysekil Municipality.

Stora Bornö is about long from north to south and is largely covered with pine forests. The island's highest point is above sea level and in many places the sho ...

in Gullmarsfjorden

Gullmarn, also known as Gullmarsfjorden or Gullmaren, is a threshold fjord in the middle of Bohuslän Archipelago on the west coast of Sweden. It is the largest of the Bohuslän fjords with a length of and a width ranging from . At its mouth, t ...

, Sweden, which would become her summer research destination for the next 12 years. Her analyses with Berta Karlik

Berta Karlik (24 January 1904 – 4 February 1990) was an Austrian physicist. She worked for the University of Vienna, eventually becoming the first female professor at the institution. While working with Ernst Foyn she published a paper on the ra ...

on the half-lives of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weakly ...

, thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

, and actinium

Actinium is a chemical element with the symbol Ac and atomic number 89. It was first isolated by Friedrich Oskar Giesel in 1902, who gave it the name ''emanium''; the element got its name by being wrongly identified with a substance A ...

decay identified radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares t ...

and elemental alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay, but may also be pro ...

ranges. In 1933, Rona and Karlik won the Austrian Academy of Sciences Haitinger Prize The Haitinger Prize of the Austrian Academy of Sciences was founded in 1904 by the chemist and factory director, Ludwig Camillo Haitinger (1860–1945), who created the award in honor of his father, Karl Ludwig Haitinger. From 1905 to 1943 it was a ...

.

In 1934, Rona was back in Paris studying with Joliot-Curie, who had discovered artificial radioactivity

Induced radioactivity, also called artificial radioactivity or man-made radioactivity, is the process of using radiation to make a previously stable material radioactive. The husband and wife team of Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot-Curie ...

. Soon after, Curie died and Rona became ill, but she was able to return to Vienna late the following year to share what had been learned with a group of researchers made up of Pettersson, Elizabeth Kara-Michailova, and Ernst Føyn, who was serving as an assistant to Ellen Gleditsch

Ellen Gleditsch (29 December 1879 – 5 June 1968) was a Norwegian radiochemist and Norway's second female professor. Starting her career as an assistant to Marie Curie, she became a pioneer in radiochemistry, establishing the half-life of r ...

at that time. Their studies centered on research of the effect caused by bombarding radionuclides with neutrons. In 1935 Rona consolidated some of these relationships, working on Stora Bornö, then visiting Gleditsch in Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, then traveling to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

to see Hevesy, and later to Kålhuvudet, Sweden to meet with Karlik and Pettersson. One of the projects the group had been working on for several years was to determine if there was any correlation between water depth and radium content, and their seawater research evaluated the concentration of elements in seawater collected from different locations.

After the 1938 Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the Nazi Germany, German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Ger ...

, Rona and Marietta Blau left the Radium Institute because of their Jewish heritage and the antisemitic persecution they experienced in the laboratory. Rona first returned to Budapest and worked in an industrial laboratory, but within a few months, the position was eliminated. She worked from October to December 1938 in Sweden, and then accepted a temporary position for one year at the University of Oslo

The University of Oslo ( no, Universitetet i Oslo; la, Universitas Osloensis) is a public research university located in Oslo, Norway. It is the highest ranked and oldest university in Norway. It is consistently ranked among the top univers ...

, which had been offered by Gleditsch. Reluctant to leave her home, at the end of her year in Oslo, Rona returned to Hungary. She was appointed to a position at the Radium-Cancer Hospital in Budapest, preparing radium for medicinal purposes.

Emigration

Faced with encroachingRussians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

on one side and the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

involvement in Hungary during World War II

During World War II, the Kingdom of Hungary was a member of the Axis powers.Karl Herzfeld

Karl Ferdinand Herzfeld (February 24, 1892 – June 3, 1978) was an Austrian- American physicist.

Education

Herzfeld was born in Vienna during the reign of the Habsburgs over the Austro-Hungarian Empire. "He came from a prominent, recently ...

, who helped her secure a teaching post at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

in Washington, D.C. During this period, she was awarded a Carnegie Fellowship

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world. Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establis ...

to research at the Geophysical Laboratory

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. T ...

of the Carnegie Institute, working on analysis of seawater and sediments. Between 1941 and 1942, she conducted work at Carnegie in conjunction with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, i ...

, measuring the amount of radium in seawater and river water. Her study, completed in 1942, showed that the ratio of radium to uranium was lower in seawater and higher in river water.

After returning from a summer visit to Los Altos, California

Los Altos (; Spanish for "The Heights") is a city in Santa Clara County, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area. The population was 31,625 according to the 2020 census.

Most of the city's growth occurred between 1950 and 1980. Originally ...

, Rona received a vague telegram from the Institute of Optics

The Institute of Optics is a department and research center at the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York. The institute grants degrees at the bachelor's, master's and doctoral levels through the University of Rochester School of Enginee ...

at the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester (U of R, UR, or U of Rochester) is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York. The university grants Undergraduate education, undergraduate and graduate degrees, including Doctorate, do ...

referencing war work and polonium, but no details of an assignment. When Rona responded that she would be interested in helping with the war effort but had immigration issues, Brian O'Brien

Brian O'Brien was an optical physicist and "the founder of the Air Force Studies Board and its chairman for 12 years. O'Brien received numerous awards, including the Medal for Merit, the nation's highest civilian award, for his work on optics in ...

appeared in her office and explained the nature of the confidential work for the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. They proposed buying her method of polonium extraction and gave specific instructions for the type of assistants she might use – someone unfamiliar with chemistry or physics. Her non-citizen status did not preclude her from working for the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May ...

(OSRD), to which she gave her methods without compensation. Before the Manhattan Project, polonium had been used only in small samples, but the project proposed to use both polonium and beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form m ...

to create a reaction forcing neutrons to be ejected and ignite the fission reaction required for the atom bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. Plutonium plants, based on her specifications for what was needed to process element, were built in the New Mexico desert at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, i ...

, but Rona was given no details.

Rona's methods were also used as part of the experiments conducted by the Office of Human Radiation Experiments to determine the effects of human exposure to radiation. Early in her career, she had been exposed to the dangers of radium. Rona's requests for protective gas masks were denied, as Stefan Meyer downplayed the hazards of exposure. She purchased protective gear with her own money, not believing there was no danger. When vials of radioactive material exploded and the laboratory became contaminated, Rona was convinced her mask had saved her. Gleditsch had also warned her of the dangers the year Rona was sick and living in Paris, when Joliot-Curie died, emphasizing the risk of radium-related anemia. In her 1978 book about her experiences, Rona wrote about the damage to bones, hands, and lungs of the scientists studying radioactivity. Since they wore no gloves and frequently poured substances between vials without protection, she noted that their thumbs, forefingers, and ring fingers were often damaged. The secrecy surrounding the project makes it difficult to know if any of the scientists not directly working on any project knew specifically what their contributions were being used for.

Later career

Rona continued teaching until 1946 at Trinity. In 1947, she began working at theArgonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research national laboratory operated by UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facility is located in Lemont, Illinois, outside of Chicago, and is the lar ...

. Her work there focused on ion exchange

Ion exchange is a reversible interchange of one kind of ion present in an insoluble solid with another of like charge present in a solution surrounding the solid with the reaction being used especially for softening or making water demineralised, ...

reactions and she published several works for the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

. In 1948, she became a naturalized U.S. citizen. In 1950, she began research work at the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies as a chemist and senior scientist in nuclear studies. During this period, she collaborated with Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M University System in 1948. As of late 2021, T ...

on the geochronology

Geochronology is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, whereas relative geochronology is p ...

of seabed sediments, dating core samples by estimating their radioactive decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is consid ...

. She retired from Oak Ridge in 1965 and then went to work at the University of Miami

The University of Miami (UM, UMiami, Miami, U of M, and The U) is a private research university in Coral Gables, Florida. , the university enrolled 19,096 students in 12 colleges and schools across nearly 350 academic majors and programs, ...

, teaching at the Institute of Marine Sciences where she worked for a decade. Rona retired for a second time in 1976 and returned to Tennessee in the late 1970s, publishing a book in 1978 on her radioactive tracer methods.

Rona died on 27 July 1981 in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Legacy

Rona did not receive full acknowledgment for her accomplishments during her era. She was posthumously inducted into theTennessee Women's Hall of Fame The Tennessee Women's Hall of Fame is a non-profit, volunteer organization that recognizes women who have contributed to history of the U.S. state of Tennessee.

History

The organization was founded and incorporated as a non-profit organization in ...

in 2015. In 2019 she finally received an obituary in the ''New York Times'', as part of their " Overlooked (obituary feature) series.

Selected works

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *See also

*Timeline of women in science

This is a timeline of women in science, spanning from ancient history up to the 21st century. While the timeline primarily focuses on women involved with natural sciences such as astronomy, biology, chemistry and physics, it also includes women ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Worldcat Publications Erzsébet Róna

Worldcat Publications Elisabeth Róna

Worldcat Publications Elizabeth Rona

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rona, Elizabeth 1890 births 1981 deaths Hungarian women chemists Hungarian chemists Hungarian educators Hungarian women educators 20th-century women scientists Eötvös Loránd University alumni Trinity Washington University faculty Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies faculty University of Miami faculty Jewish women scientists Manhattan Project people