Elihu Root on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

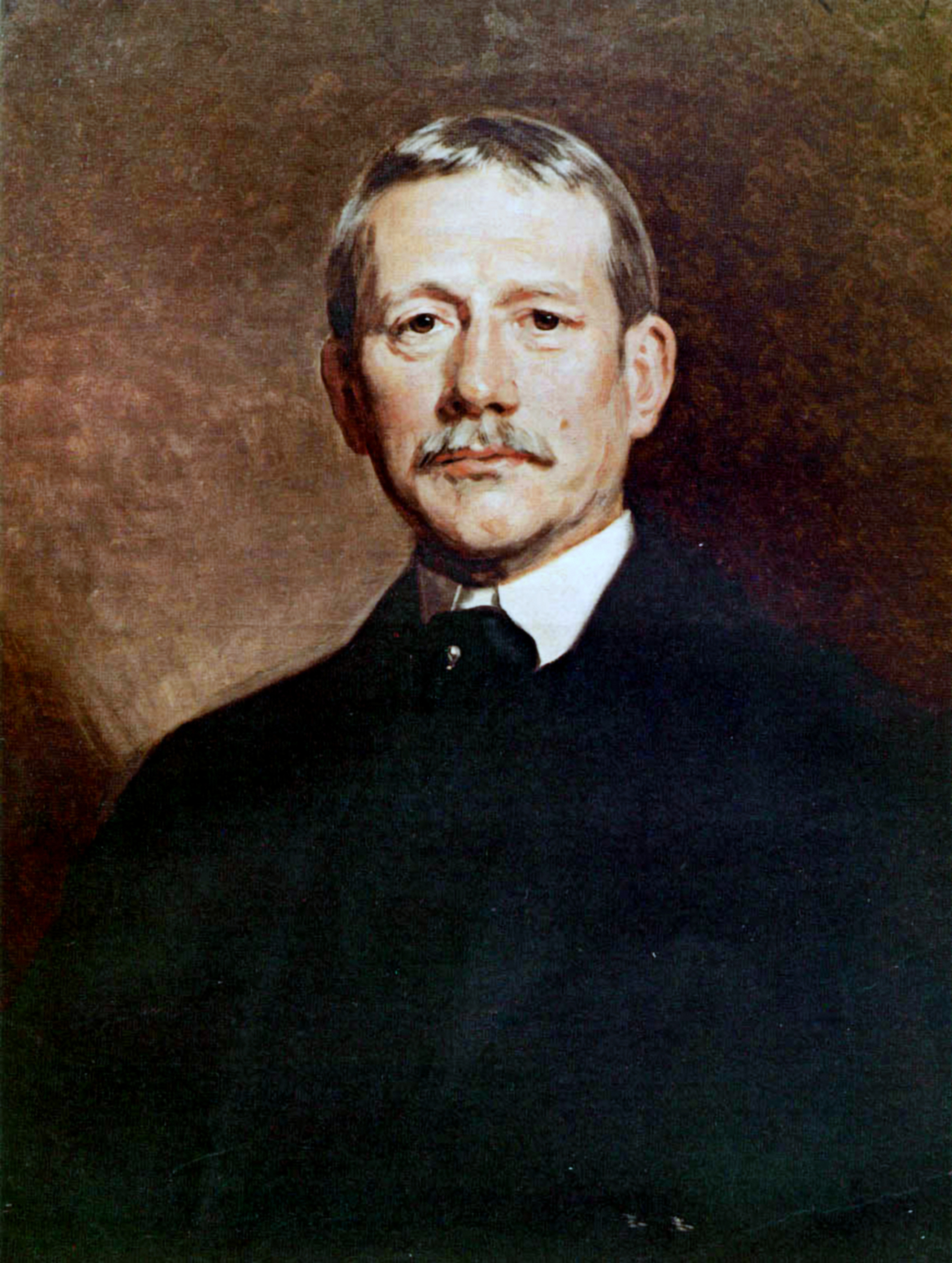

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as the 41st

Early in his legal career, Root joined the Union League Club, where he met a number of young New York Republicans. He avoided political office personally, believing that it would obstruct his legal career. As an example, he cited Robert H. Strahan, an early law partner who had entered state politics. "It ruined him as a lawyer," Root said in 1930. "He got in the habit politicians have of sitting around and talking instead of working." Nevertheless, after his 1878 marriage and move to East 55th Street, Root became actively involved in the Republican Party organization in his well-to-do State Assembly district. He also expanded his involvement at the Union League Club, where his father-in-law was an active member. In 1879, he was elected to the Club's executive committee.

Through the Club, Root met

Early in his legal career, Root joined the Union League Club, where he met a number of young New York Republicans. He avoided political office personally, believing that it would obstruct his legal career. As an example, he cited Robert H. Strahan, an early law partner who had entered state politics. "It ruined him as a lawyer," Root said in 1930. "He got in the habit politicians have of sitting around and talking instead of working." Nevertheless, after his 1878 marriage and move to East 55th Street, Root became actively involved in the Republican Party organization in his well-to-do State Assembly district. He also expanded his involvement at the Union League Club, where his father-in-law was an active member. In 1879, he was elected to the Club's executive committee.

Through the Club, Root met

At Root's appointment, the Department of War had a public reputation for inefficiency, corruption, and scandals which had characterized Alger's tenure and the war. His immediate focus was reforming military administration, which he viewed as a prerequisite for success in territorial administration or any future military campaign. Though the United States had just completed a successful, brief military campaign against Spain, its officer corps was still organized on peacetime terms; Root set about permanently placing the United States military on a war footing. Root worked closely with Adjutant General Henry Clark Corbin and William Harding Carter.

His chief obstacle was Commanding General of the Army

At Root's appointment, the Department of War had a public reputation for inefficiency, corruption, and scandals which had characterized Alger's tenure and the war. His immediate focus was reforming military administration, which he viewed as a prerequisite for success in territorial administration or any future military campaign. Though the United States had just completed a successful, brief military campaign against Spain, its officer corps was still organized on peacetime terms; Root set about permanently placing the United States military on a war footing. Root worked closely with Adjutant General Henry Clark Corbin and William Harding Carter.

His chief obstacle was Commanding General of the Army

Root's primary administrative challenge as Secretary of War was the effort to establish control of the Philippine Islands. Though American government of the islands was internationally recognized under the Treaty of Paris, the native independence movement resisted imperial control. Relative to Cuba and Puerto Rico, the islands' distance and the relative underdevelopment of Spanish institutions made administration far more challenging.

Root's primary goal was the establishment of a civilian governor-general (as had been applied in Cuba) rather than a military governor; however, he felt that education of the native population was necessary before such a transition could be successful. In 1900, Root guided the establishment of the Philippine commission, led by

Root's primary administrative challenge as Secretary of War was the effort to establish control of the Philippine Islands. Though American government of the islands was internationally recognized under the Treaty of Paris, the native independence movement resisted imperial control. Relative to Cuba and Puerto Rico, the islands' distance and the relative underdevelopment of Spanish institutions made administration far more challenging.

Root's primary goal was the establishment of a civilian governor-general (as had been applied in Cuba) rather than a military governor; however, he felt that education of the native population was necessary before such a transition could be successful. In 1900, Root guided the establishment of the Philippine commission, led by

Root died in 1937 in New York City, with his family by his side. A simple service was held in Clinton, led by Episcopal bishop E.H. Coley of the Episcopal Diocese of Central New York. Root is buried, along with his wife Clara (d. 1928), at the Hamilton College Cemetery.

Root was the last surviving member of the McKinley Cabinet and the last Cabinet member to have served in the 19th century.

Root died in 1937 in New York City, with his family by his side. A simple service was held in Clinton, led by Episcopal bishop E.H. Coley of the Episcopal Diocese of Central New York. Root is buried, along with his wife Clara (d. 1928), at the Hamilton College Cemetery.

Root was the last surviving member of the McKinley Cabinet and the last Cabinet member to have served in the 19th century.

“A Requisite for the Success of Popular Diplomacy”

''

"Statesman and Useful Citizen" ''Vanity Fair'', 1915

*"The Government and the Coming Hague Conference." ''The Advocate of Peace (1894–1920)'' 69, no. 5 (1907): 112–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25752898. *"The Need of Popular Understanding of International Law." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 1, no. 1 (1907): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2307/2186279. *"The Sanction of International Law." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 2, no. 3 (1908): 451–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2186324. *"The Basis of Protection to Citizens Residing Abroad." ''Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting (1907-1917)'' 4 (1910): 16–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25656384. *"The Real Monroe Doctrine." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 8, no. 3 (1914): 427–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/2187489. *"The Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Nations Adopted by the American Institute of International Law." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 10, no. 2 (1916): 211–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2187520. *"The Invisible Government." ''The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science'' 64 (1916): viii–xi. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1013701. *"The Outlook for International Law." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 10, no. 1 (1916): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/2187357. *"Theodore Roosevelt." ''The North American Review'' 210, no. 769 (1919): 754–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25120404. *"PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE." ''American Bar Association Journal'' 6, no. 7 (1920): 181–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25700734. *"The Constitution of an International Court of Justice." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 15, no. 1 (1921): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/2187931. *"The Codification of International Law." ''The American Journal of International Law'' 19, no. 4 (1925): 675–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2188306. *Root, Elihu, and J. Ramsay MacDonald. "The Risks of Peace." ''Foreign Affairs'' 8, no. 1 (1929): i–xiii. https://doi.org/10.2307/20028758. Books

''The Citizen's Part in Government''

''Experiments in Government and the Essentials of the Constitution''

''Addresses on International Subjects''

''The Military and Colonial Policy of the United States: Addresses and Reports by Elihu Root''

“Theodore Roosevelt”

'' The North American Review'', November 1919. (p. 754) — A speech delivered for the Rocky Mountain Club on October 27, 1919.

''The Short Ballot and the “Invisible Government”: An Address by Elihu Root''

New York: The National Short Ballot Organization, 1919. — This address was delivered at the New York Constitutional Convention on August 30, 1915, in support of a resolution to reduce the number of elective state officers and combine the 152 state departments into 17. The measure was popularly known as the “Short Ballot”.

online

* * * * * * * * * * *

on www.nobel-winners.com

State Department Biography

* *

1922

CFR Website - Continuing the Inquiry: The Council on Foreign Relations from 1921 to 1996

History of the council by Peter Grose, a council member.

Elihu Root Papers, 1845-1937 (Papers, 1904-1937)

from Hamilton College Library, Clinton, New York. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Root, Elihu 1845 births 1937 deaths American people of English descent People from Clinton, Oneida County, New York New York (state) Republicans American Nobel laureates American prosecutors Fellows of the American Statistical Association The Hague Academy of International Law people Hamilton College (New York) alumni Members of the Institut de Droit International New York (state) lawyers New York University School of Law alumni Nobel Peace Prize laureates Members of the Sons of the American Revolution United States attorneys for the Southern District of New York United States secretaries of state United States secretaries of war Republican Party United States senators from New York (state) Presidents of the Council on Foreign Relations Presidents of the New York City Bar Association Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Progressive Era in the United States Theodore Roosevelt administration cabinet members McKinley administration cabinet members 19th-century American politicians General Society of Colonial Wars North American Trust Company people Mathematicians from New York (state) Carnegie Endowment for International Peace People associated with Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman Corresponding fellows of the British Academy 1924 United States presidential electors Presidents of the American Society of International Law Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters 20th-century United States senators Members of the American Philosophical Society

United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the President of the United States, U.S. president's United States Cabinet, Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's Presidency of George Washington, administration. A similar position, called either "Sec ...

under presidents William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

and the 38th United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

under Roosevelt. In both positions as well as a long legal career, he pioneered the American practice of international law. Root is sometimes considered the prototype of the 20th-century political " wise man", advising presidents on a range of foreign and domestic issues. He also served as a United States Senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

from New York and received the 1912 Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

.

Root was a leading New York City lawyer who moved frequently between high-level appointed government positions in Washington, D.C., and private-sector

The private sector is the part of the economy which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The private sector employs most of the workforce ...

legal practice in New York. He headed organizations such as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) is a nonpartisan international affairs think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C., with operations in Europe, South Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East, as well as the United States. Foun ...

and the American Society of International Law

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, ...

.

As Secretary of War from 1899 to 1904, Root administered colonial possessions won in the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

. Root favored a paternalistic approach to colonial administration, emphasizing technology, engineering, and disinterested public service. He helped craft the Foraker Act

The Foraker Act, , officially known as the Organic Act of 1900, is a United States federal law that established civilian (albeit limited popular) government on the island of Puerto Rico, which had recently become a possession of the United State ...

of 1900, the Platt Amendment of 1901, and the Philippine Organic Act (1902). Root also modernized the Army into a professional military apparatus with a general staff, restructured the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

, and established the U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a United States Army, U.S. Army staff college in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, with a Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle postal address, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle B ...

.

Root returned to the Roosevelt administration as Secretary of State from 1905 to 1909. He modernized the consular service by minimizing patronage, maintained the Open Door Policy in China, promoted friendly relations with Latin America, and resolved frictions with Japan over the immigration and treatment of Japanese citizens to the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast and the Western Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the Contiguous United States, contig ...

. He negotiated 24 bilateral international arbitration

International arbitration can refer to arbitration between companies or individuals in different states, usually by including a provision for future disputes in a contract (typically referred to as international commercial arbitration) or betwee ...

treaties, which led to the creation of the Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

.

As a United States Senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, Root was a conservative supporter of President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, playing a central role in Taft's nomination to a second term at the 1912 Republican National Convention

The 1912 Republican National Convention was held at the Chicago Coliseum, Chicago, Illinois, from June 18 to June 22, 1912. The party nominated President of the United States, President William Howard Taft and Vice President of the United States, ...

. By 1916, he was a leading proponent of military preparedness

Combat readiness is a condition of the armed forces and their constituent Military organization, units and formations, warships, aircraft, weapon systems or other military technology and equipment to perform during combat military operations, or fu ...

with the expectation that the United States would enter World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

sent him to Russia in 1917 in an unsuccessful effort to establish an alliance with the new revolutionary government that had replaced the Czar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

. Root supported Wilson's vision of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

but with reservations along the lines proposed by Republican senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

.

Early life and education

Elihu Root was born on February 15, 1845, inClinton, Oneida County, New York

Clinton (or ''Ka-dah-wis-dag'', "white field" in Seneca language) is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 1,942 at the 2010 census, declining to 1,683 in the 2020 ...

, to Oren Root and Nancy Whitney Buttrick, both of English descent. His father was a professor of mathematics at Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, Clinton, New York. It was established as the Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and received its c ...

.

Elihu studied at local schools, including the Clinton Grammar School and the Williston Seminary, where he was a classmate of G. Stanley Hall

Granville Stanley Hall (February 1, 1844 – April 24, 1924) was an American psychologist and educator who earned the first doctorate in psychology awarded in the United States of America at Harvard University in the nineteenth century. His ...

, before enrolling at Hamilton. He joined the Sigma Phi

The Sigma Phi Society () is an American college fraternity. Established in 1827 at Union College in Schenectady, New York, it was the second Greek letter Fraternities and sororities, fraternal organization founded in the United States. Sigma Phi ...

Society and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

society. After graduation, Root was an instructor of physical education for two years at Williston Seminary and taught for one year at the Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

Free Academy.

Despite his parents' encouragement to become a Presbyterian minister, Root moved to New York City in 1865 with his brother Wally and sought a career in the law. He enrolled at New York University School of Law

The New York University School of Law (NYU Law) is the law school of New York University, a private research university in New York City.

Established in 1835, it was the first law school established in New York City and is the oldest survivin ...

and earned money teaching American history at elite girls' schools. At the time, most law students in the United States applied for admission to the bar after one year of study, but Root stayed on for a second year, essentially a private tutelage under Professor John Norton Pomeroy

John Norton Pomeroy (April 12, 1828 – February 15, 1885) was an American lawyer, writer, and law professor. “Perhaps the most important text book writer of the last third of the nineteenth century,” Pomeroy is one of the foremost contri ...

. He graduated in 1867 with a Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

and was admitted to the bar on June 18, 1867.

Legal and business career

Upon his admission to the bar, Root completed a year of unpaid apprenticeship at the leading New York City firm Mann and Parsons. In 1868, he and several other young lawyers founded the firm of Strahan & Root with offices on Pine Street. He had various partners through 1897, when a disagreement led to the dissolution of his firm and the formation of Root, Howard, Winthrop & Stimson, a predecessor of the modern firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman. His early work was assorted and menial, but expanded rapidly after he met John J. Donaldson, the president of theBank of North America

The Bank of North America was the first chartered bank in the United States, and served as the country's first ''de facto'' central bank. It was chartered by the Congress of the Confederation on May 26, 1781, and opened in Philadelphia, Pennsy ...

, through their pastor. Donaldson hired Root as a Latin tutor and was impressed with his ability as a lawyer, eventually sending him personal matters and small cases for the Bank. In March 1869, Root was hired to reorganize the bank to acquire a state charter. Soon after, Alexander Compton was elevated to the partnership, and the firm was renamed Compton & Root. Root's public profile and professional reputation were enhanced by his defense of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

boss William M. Tweed

William Magear "Boss" Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878) was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political machine that played a major role in the politics of 19th ...

, and Compton & Root grew throughout the 1870s into a varied practice with a primary focus on banks, railroads, wills and estates, and municipal government.

Root was admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

in 1881. In 1883, President Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

appointed him U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, the chief government attorney in New York City. As U.S. Attorney, Root headed the prosecutions for the Ward and Grant fraud which precipitated the Panic of 1884

The Panic of 1884 was an economic panic during the Depression of 1882–1885. It was unusual in that it struck at the end rather than the beginning of the recession. The panic created a credit shortage that led to a significant economic decline i ...

.

Through 1899, Root took on many other prominent and wealthy clients, including Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

, Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

, Charles Anderson Dana

Charles Anderson Dana (August 8, 1819 – October 17, 1897) was an American journalist, author, and senior government official. He was a top aide to Horace Greeley as the managing editor of the powerful Republican newspaper '' New-York Tribune ...

, William C. Whitney, Thomas Fortune Ryan, the Havemeyer family, Charlie Delmonico, and E. H. Harriman. In 1889, Root advised Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The speaker of the United States House of Representatives, commonly known as the speaker of the House or House speaker, is the Speaker (politics), presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives, the lower chamber of the United ...

Thomas Brackett Reed on his controversial efforts to revise the House rules.

On January 19, 1898, Root was elected a member of the executive committee of the newly formed North American Trust Company.

After moving to Washington in 1899, Root never again became partner in a firm. His public career lasted through 1915, when Root returned to practice in an of counsel

Of counsel is the title of an attorney in the legal profession of the United States who often has a relationship with a law firm or an organization but is neither an associate nor partner. Some firms use titles such as "counsel", "special couns ...

role at his son's firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland. Around that time, Root was elected the 38th president of the American Bar Association.

Defense of Tweed ring

In December 1871,Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

boss William M. Tweed

William Magear "Boss" Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878) was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political machine that played a major role in the politics of 19th ...

was indicted on charges of deceit and fraud in connection to his real estate dealings and political corruption. Tweed retained eminent defense counsel led by David Dudley Field; Root joined the case on behalf of Tweed's co-defendant James Ingersoll, a furniture manufacturer who stood accused of fraudulently billing the city government for millions of dollars. Root's law partner, Alexander Compton, was Ingersoll's cousin by marriage, and Compton turned the case over to Root due to his courtroom experience. Despite his family's dismay, he accepted the case and joined Tweed's defense in addition to Ingersoll's.

The Tweed case stretched on for years, with the first trial commencing more than fifteen months after the indictment and ending in a hung jury. Four more indictments were brought in November 1873 after the defense's failed attempt to get judge Noah Davis to recuse himself. Root took a minor role in the proceedings, examining jurors and occasionally cross-examining the prosecution witnesses. The jury returned a guilty verdict on two hundred and four counts; Davis imposed a sentence of twelve years and a $12,750 fine, later reduced on appeal. Three of Tweed's attorneys were fined for contempt of court; Root was not among them. Instead, Davis addressed the junior attorneys:

"I know how young lawyers are apt to follow their seniors. ... lihu Root and Willard Bartlett">Willard_Bartlett.html" ;"title="lihu Root and Willard Bartlett">lihu Root and Willard Bartlettdisplayed great ability during the trial. I shall impose no penalty, except what they may find in these few words of advice: I ask you young gentlemen, to remember that good faith to a client never can justify or require bad faith to your own consciences, and that however good a thing it may be to be known as successful and great lawyers, it is even a better thing to be known as honest men."Root took a more active role in the Ingersoll defense, successfully appealing a jurisdictional issue to the New York Court of Appeals. Judge Allen remarked to Root's co-counsel that Root's argument "was not excelled by any in the case." Ingersoll was ultimately sentenced to five years but was pardoned by Governor Samuel J. Tilden. After Root had risen to national prominence, his work on the Tweed case formed the basis for public attacks from newspapers owned and directed by

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

, particularly after Root opposed Hearst's 1906 campaign for governor. Hearst exaggerated Root's role in the case and implied he had advised Tweed on political corruption before his indictment. Root's fee in the case, paid partly in cash and partly by a real estate transfer, also came in for criticism, with Hearst papers implying that Root had inherited Tweed's mansion. In fact, Tweed was penniless after paying the fines assessed against him, and his heavily encumbered real estate holdings were his lone assets.

U.S. Attorney for the Southern District (1883–85)

Early in his legal career, Root joined the Union League Club, where he met a number of young New York Republicans. He avoided political office personally, believing that it would obstruct his legal career. As an example, he cited Robert H. Strahan, an early law partner who had entered state politics. "It ruined him as a lawyer," Root said in 1930. "He got in the habit politicians have of sitting around and talking instead of working." Nevertheless, after his 1878 marriage and move to East 55th Street, Root became actively involved in the Republican Party organization in his well-to-do State Assembly district. He also expanded his involvement at the Union League Club, where his father-in-law was an active member. In 1879, he was elected to the Club's executive committee.

Through the Club, Root met

Early in his legal career, Root joined the Union League Club, where he met a number of young New York Republicans. He avoided political office personally, believing that it would obstruct his legal career. As an example, he cited Robert H. Strahan, an early law partner who had entered state politics. "It ruined him as a lawyer," Root said in 1930. "He got in the habit politicians have of sitting around and talking instead of working." Nevertheless, after his 1878 marriage and move to East 55th Street, Root became actively involved in the Republican Party organization in his well-to-do State Assembly district. He also expanded his involvement at the Union League Club, where his father-in-law was an active member. In 1879, he was elected to the Club's executive committee.

Through the Club, Root met Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

, an experienced Manhattan attorney and the powerful Collector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at ...

. In 1879, Arthur and Alonzo B. Cornell persuaded Root to stand for the Court of Common Pleas. Root viewed the campaign as hopeless given the city's Democratic reputation, took no part in the campaign, and was relieved to lose the election. He never again stood for a popular election, other than as a delegate to party conventions, but his association with Arthur rapidly advanced his national profile. In 1880, Arthur was elected Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

with Root's support. Root attended the inauguration and was among the friends at Arthur's New York home on September 19, 1881, when the Vice President was informed that President James A. Garfield had succumbed to an assassin's bullet and that he had succeeded to the presidency. In 1881, Root encountered another future President: Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, who was elected to the State Assembly from Root's district. Root actively supported the young Roosevelt's career by signing Roosevelt's nomination papers, aiding in efforts to sideline a rival candidate, and speaking on behalf of his 1886 mayoral campaign.

Though many observers expected Arthur would offer Root appointment as Attorney General or to another cabinet post, in March 1883 he appointed Root United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York

The United States attorney for the Southern District of New York is the United States Attorney, chief federal law enforcement officer in eight contiguous New York counties: the counties (coextensive boroughs of New York City) of New York County, ...

. There was limited opposition to his nomination given that Arthur was trying to force out a political rival, Stewart L. Woodford, who had been appointed by Garfield, but he was approved by the Senate and sworn in on March 12. The role was part-time, with Root devoting his mornings to the Attorney's office and his afternoons to his private practice. Many of his cases were suits for the refund of customs duties paid under protest.

International law

As U.S. Attorney, Root had his first exposure tointernational law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, which would become the cornerstone of his public legacy. He prosecuted two cases for violation of United States neutrality laws against vessels for aiding Haitian and Colombian insurgents and defended the government in the Head Money Cases, a challenge to the Immigration Act of 1882 on grounds that it conflicted with international treaties with the Republic of the Netherlands. The suit was appealed to the Supreme Court, where the government prevailed.

Ward and Grant prosecutions

Root's highest profile case as U.S. Attorney was the prosecution for embezzlement of James C. Fish, a partner in Ward and Grant, aPonzi scheme

A Ponzi scheme (, ) is a form of fraud that lures investors and pays Profit (accounting), profits to earlier investors with Funding, funds from more recent investors. Named after Italians, Italian confidence artist Charles Ponzi, this type of s ...

trading on the name of former President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and his son, Ulysses Jr. The collapse of Ward and Grant precipitated the Panic of 1884

The Panic of 1884 was an economic panic during the Depression of 1882–1885. It was unusual in that it struck at the end rather than the beginning of the recession. The panic created a credit shortage that led to a significant economic decline i ...

. Fish offered a defense of ignorance, claiming that he had been fooled by the scheme, just as the Grants had been. For six weeks, Root devoted his full attention to the case, including the deposition of former President Grant, who died before a verdict was reached. The jury returned a guilty verdict after a night of deliberation, and Fish was sentenced to ten years in prison.

The Fish verdict won Root praise in the press. According to the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American conservative news website and former newspaper based in Manhattan, New York. From 2009 to 2021, it operated as an (occasional and erratic) online-only publisher of political and economic opinion pieces, as we ...

'', "The manner in which he conducted the prosecution... has won him high praise wherever reports of the trial have been published. The cross-examination of the defendant was characterized by exceptional acumen and professional skill, and was made much more effective than it would otherwise have been by Mr. Root's evident familiarity with the details of the banking business." The '' Mail and Express'' wrote: "The credit of the result must be awarded mainly to the District Attorney." In particular, Root was credited with vindicating the late President: "The unspeakable meanness of the conspirators in trying to save themselves by implicating General Grant in their fraudulent transactions... was dealt with in terms of deserved scorn and severity by the District Attorney."

Just before his resignation, Root successfully won an indictment of Fish's co-conspirator, Ferdinand Ward. He quietly submitted his resignation to President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

on July 1, 1885. Two other members of the conspiracy were later prosecuted, and Root returned from private life to assist with the prosecutions.

Secretary of War (1899–1904)

In July 1899, PresidentWilliam McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

offered Root a position in his cabinet as Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. The offer came on the heels of the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

. In general, the war had been a success, but Secretary Russell A. Alger had come under heavy criticism for his management of the department, and McKinley had requested his resignation. At first, Root declined, but accepted when he realized "McKinley wanted a lawyer to run the governments of the islands."

As Secretary of War, Root actively framed the establishment of civilian governments in the new American territories of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. He also modernized the Department of War. His rapid success and popularity led Root to become the first choice of the Republican National Committee for the vice presidential nomination in 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15 ...

by December 1899, but McKinley had objected to losing his Secretary of War, and Root himself preferred to stay in the Cabinet. The nomination ultimately went to Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

over his own objection and led to his ascension as President upon the assassination of McKinley in 1901.

During the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

of 1900, Root handled foreign policy matters for Secretary of State John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a Secretary to the President of the United States, private secretary for Abraha ...

, who was ill.

Root resigned from the cabinet on February 1, 1904, and returned to private practice as a lawyer. He was succeeded by William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

.

Military reforms

At Root's appointment, the Department of War had a public reputation for inefficiency, corruption, and scandals which had characterized Alger's tenure and the war. His immediate focus was reforming military administration, which he viewed as a prerequisite for success in territorial administration or any future military campaign. Though the United States had just completed a successful, brief military campaign against Spain, its officer corps was still organized on peacetime terms; Root set about permanently placing the United States military on a war footing. Root worked closely with Adjutant General Henry Clark Corbin and William Harding Carter.

His chief obstacle was Commanding General of the Army

At Root's appointment, the Department of War had a public reputation for inefficiency, corruption, and scandals which had characterized Alger's tenure and the war. His immediate focus was reforming military administration, which he viewed as a prerequisite for success in territorial administration or any future military campaign. Though the United States had just completed a successful, brief military campaign against Spain, its officer corps was still organized on peacetime terms; Root set about permanently placing the United States military on a war footing. Root worked closely with Adjutant General Henry Clark Corbin and William Harding Carter.

His chief obstacle was Commanding General of the Army Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was a United States Army officer who served in the American Civil War (1861–1865), the later American Indian Wars (1840–1890), and the Spanish–American War,

(1898). From 1895 to 1903 ...

; the offices of Commanding General and Secretary of War had long been engaged in a power struggle, and Root's reforms would directly implicate Miles's authority. Root proposed the establishment of a General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

led by the office of Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

. The Chief of Staff was to be a general officer of the Army answerable directly to the Secretary of War and the President. The Chief of Staff would carry out the Secretary's instructions and supervise discipline and maneuvers. The reorganization was accomplished by an act of Congress passed on February 14, 1903. Root also changed the procedures for promotions and also devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line. Working with Secretary of the Navy William Henry Moody

William Henry Moody (December 23, 1853 – July 2, 1917) was an American politician and jurist who held positions in all three branches of the Government of the United States. He represented parts of Essex County, Massachusetts, Essex Count ...

, Root established closer coordination between the Army and Navy, including the establishment of a joint board under General Orders No. 107.

Root also sought to enhance military training. To that end, he enlarged the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

and established the U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a United States Army, U.S. Army staff college in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, with a Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle postal address, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle B ...

and additional training posts, especially Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

. He likewise provided for additional National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

officer training programs at Fort Leavenworth for those volunteer officers who had shown capacity during the Spanish–American War; per Root's instructions, the National Guard would also be equipped with the same arms as the regular army and examinations would be administered to qualify members for higher command.

Territorial administration

As a result of theSpanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, the United States held military control of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. As Secretary of War, Root was tasked with the administration of martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

on the islands and the eventual transition to civilian government. Under the terms of the Teller Amendment

The Teller Amendment was an amendment to a joint resolution of the United States Congress, enacted on April 20, 1898, in reply to President William McKinley's War Message. The amendment was introduced after the USS ''Maine'' exploded in February ...

, the United States was additionally bound to return "control of ubato its people." Particularly in the Philippines, the United States also faced militant insurgency from natives who resisted their transfer from one foreign empire to another.

He worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, ensured a charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the United States from Puerto Rico. When the Anti-Imperialist League attacked American policies in the Philippines, Root defended the policies and counterattacked the critics, saying they prolonged the insurgency.

For this work, he relied on legal advisor Charles Edward Magoon

Charles Edward Magoon (December 5, 1861 – January 14, 1920) was an American lawyer, judge, diplomat, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor of the Panama Canal Zone; he also served as Minister to Panama at the same time. He was ...

. Magoon had been hired at the Bureau of Insular Affairs by Root's predecessor, Russell Alger, and drafted an internal report taking the official position that residents of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and other territories became subject to all the rights granted by the Constitution. After Root's appointment, Magoon controversially revised the department's legal position to require an Act of Congress, as had been passed in the cases of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

and Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, to regulate the rights of territorial subjects. This revised position was upheld by the Supreme Court in a series of landmark decisions collectively known as the Insular Cases

The Insular Cases are a series of opinions by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1901 about the status of U.S. territories acquired in the Spanish–American War. Some scholars also include cases regarding territorial status decided up unt ...

.

In Cuba, the American challenge was to arrange for the transition to civilian government while preserving order and guaranteeing protection against international predation. Root established the island's first republican form of government under the command of Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

. This was accomplished by the Cuban constitution of 1901, and the American military government withdrew in 1902.

Philippine-American War

Root's primary administrative challenge as Secretary of War was the effort to establish control of the Philippine Islands. Though American government of the islands was internationally recognized under the Treaty of Paris, the native independence movement resisted imperial control. Relative to Cuba and Puerto Rico, the islands' distance and the relative underdevelopment of Spanish institutions made administration far more challenging.

Root's primary goal was the establishment of a civilian governor-general (as had been applied in Cuba) rather than a military governor; however, he felt that education of the native population was necessary before such a transition could be successful. In 1900, Root guided the establishment of the Philippine commission, led by

Root's primary administrative challenge as Secretary of War was the effort to establish control of the Philippine Islands. Though American government of the islands was internationally recognized under the Treaty of Paris, the native independence movement resisted imperial control. Relative to Cuba and Puerto Rico, the islands' distance and the relative underdevelopment of Spanish institutions made administration far more challenging.

Root's primary goal was the establishment of a civilian governor-general (as had been applied in Cuba) rather than a military governor; however, he felt that education of the native population was necessary before such a transition could be successful. In 1900, Root guided the establishment of the Philippine commission, led by William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, as a move toward autonomous civil government. The first step in his proposed process was the establishment of municipal governments and administrative divisions. The commission was to be guided by the principles of the Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

.

Alaskan boundary dispute

In addition to his duties as Secretary of War, Root was one of three Americans appointed by President Roosevelt (withHenry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

and George Turner) to an international arbitration court to resolve the boundary dispute between Alaska and Great Britain. The dispute arose as a result of the Klondike Gold Rush of 1900, which heightened interest in the region and tensions over the exact boundary between the regions.

On October 20, 1903, the dispute was resolved by British jurist Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone in favor of the United States on every point of contention.

Secretary of State (1905–1909)

Root's retirement from public office was brief, but he remained active in public life, delivering speeches in defense of Roosevelt's policies in Panama and in the Northern Securities case. AfterMark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and ...

died in February 1904, shortly after Root's resignation, Root declined to succeed him as chair of the Republican National Committee. He also repeatedly refused efforts to draft him as the Republican candidate for Governor in the 1904 election; instead, he focused on securing Roosevelt's nomination to a full term at the national convention, where he delivered the opening speech.

After the death of John Hay, President Roosevelt named Root as United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

and he returned to the cabinet on July 7, 1905. As secretary, Root placed the consular service under the civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

. He maintained the Open Door Policy in the Far East.

On a tour of Latin America in 1906, Root persuaded those governments to participate in the Hague Peace Conference. He worked with Japan to limit emigration to the United States and on dealings with China. He established the Root–Takahira Agreement

The was a major 1908 agreement between the United States and the Empire of Japan that was negotiated between United States Secretary of State Elihu Root and Japanese Ambassador to the United States Takahira Kogorō. It was a statement of longsta ...

. He worked with Great Britain in arbitration of issues between the United States and Canada on the Alaska boundary dispute

The Alaska boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which then controlled Canada's foreign relations. It was resolved by arbitration in 1903. The dispute had existe ...

, and competition in the North Atlantic fisheries. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

for his efforts for spreading the use of arbitration in resolving international disputes.

United States Senator (1909–1915)

Overview

In January 1909, Root was elected by the legislature as aU.S. Senator from New York

Below is a list of U.S. senators who have represented the State of New York in the United States Senate since 1789. The date of the start of the tenure is either the first day of the legislative term (senators who were elected regularly before th ...

, serving from March 4, 1909, to March 3, 1915. He was a member of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He chose not to seek re-election in 1914

This year saw the beginning of what became known as the First World War, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip ...

.

During and after his Senate service, Root served as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) is a nonpartisan international affairs think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C., with operations in Europe, South Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East, as well as the United States. Foun ...

, from 1910 to 1925.

In 1912, as a result of his work to bring nations together through arbitration and cooperation, Root received the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

.

Notable Policy Positions

In a 1910 letter published by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', Root supported the proposed income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

amendment, which was ratified as the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Sixteenth Amendment (Amendment XVI) to the United States Constitution allows Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states on the basis of population. It was passed by Congress in 1909 in response to the 1895 ...

:

It is said that a very large part of any income tax under the amendment would be paid by citizens of New York... The reason why the citizens of New York will pay so large a part of the tax in New York City is the chief financial and commercial center of a great country with vast resources and industrial activity. For many years Americans engaged in developing the wealth of all parts of the country have been going to New York to secure capital and market their securities and to buy their supplies. Thousands of men who have amassed fortunes in all sorts of enterprises in other states have gone to New York to live because they like the life of the city or because their distant enterprises require representation at the financial center. The incomes of New York are in a great measure derived from the country at large. A continual stream of wealth sets toward the great city from the mines and manufactories and railroads outside of New York.

Election of 1912 and Judicial Authority

During the 1912 presidential election, Root was placed in a difficult position regarding his two friends and political partners:William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. Beginning in 1910, Roosevelt had begun challenging the absolute authority of judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which a government's executive, legislative, or administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. In a judicial review, a court may invalidate laws, acts, or governmental actions that are in ...

, arguing that the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

was using its power to strike down necessary reform legislation, as best represented in decisions like ''Lochner v. New York'' (1905). Taft, a lawyer and former judge (and future Supreme Court Chief Justice), was appalled, believing Roosevelt would be a danger to the nation's constitutional order if re-elected. Root, himself a lawyer and constitutional conservative, agreed with some of Roosevelts criticisms on a personal level, but thought that attacking the court's authority in such an open way was extremely dangerous. He himself thought judicial review was "the most valuable contribution of America to political science." While he would not attack his former boss in public, he played a key role in the 1912 Republican National Convention

The 1912 Republican National Convention was held at the Chicago Coliseum, Chicago, Illinois, from June 18 to June 22, 1912. The party nominated President of the United States, President William Howard Taft and Vice President of the United States, ...

as convention chairman. There, he formally counted the delegates that gave the nomination to Taft and offered a speech that aligned the Republican Party with a defense of the Supreme Court's authority. Though Roosevelt would still run as the Progressive "Bull Moose" Party nominee, the split in the Republican Party ensured his defeat. Thereafter, Root and Taft would play an important role in identifying the Republican Party with constitutional conservatism.

World War I

At the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914, Root opposed neutrality. Root promoted the Preparedness Movement

The Preparedness Movement was a campaign led by former Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Leonard Wood, and former President Theodore Roosevelt to strengthen the United States Armed Forces, U.S. military af ...

to get the United States ready for actual participation in the war. He was a leading advocate of American entry into the war on the side of the British and French because he feared the militarism of Germany would be bad for the world and for the United States.

In 1915, Root served as president of the State of New York Constitutional Convention.

In June 1916, he scotched talk that he might contend for the Republican presidential nomination, stating that he was too old to bear the burden of the Presidency. At the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the Republican Party in the United States. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal o ...

, Root reached his peak strength of 103 votes on the first ballot. The Republican presidential nomination went to Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, who lost the election to the Democrat Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

.

Root Commission

In June 1917, at age 72, Root headed a mission to Russia sent by President Wilson to arrange American co-operation with theRussian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

headed by Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early November 1917 ( N.S.).

After th ...

. Root remained in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

for close to a month and was not much impressed by what he saw. American financial aid to the new regime was possible only if the Russians would fight on the Allied side. The Russians, he said, "are sincere, kindly, good people but confused and dazed". He summed up the Provisional Government trenchantly: "No fight, no loans." This provoked the Provisional Government to initiate failed offensives against Austrian forces in July 1917. The resulting steep decline in popularity of the Provisional Government opened the door for the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

party and the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

.

Root was the founding chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

, established in 1918 in New York.

Later career

In the Senate fight in 1919 over American membership in theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, Root supported Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

's proposal of membership with certain reservations that allowed the United States government to decide whether or not it would go to war. The United States never joined, but Root supported the League of Nations and served on the commission of jurists which created the Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

. In 1922, when Root was 77, President Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

appointed him as a delegate to the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

as part of an American team headed by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Root was a presidential elector

In the United States, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president in the presidential election. This process is described in ...

for Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

in the 1924 presidential election.

Root also worked with Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

in programs for international peace and the advancement of science, becoming the first president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) is a nonpartisan international affairs think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C., with operations in Europe, South Asia, East Asia, and the Middle East, as well as the United States. Foun ...

. Root was also among the founders of the American Law Institute

The American Law Institute (ALI) is a research and advocacy group of judges, lawyers, and legal scholars limited to 3,000 elected members and established in 1923 to promote the clarification and simplification of United States common law and i ...

in 1923 and helped create The Hague Academy of International Law in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. Root served as vice president of the American Peace Society

The American Peace Society was a pacifist group founded upon the initiative of William Ladd, in New York City, May 8, 1828. It was formed by the merging of many state and local societies, from New York, Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, ...

, which publishes '' World Affairs'', the oldest U.S. journal on international relations.

Views

Opposition to women's suffrage

Root was a prominent opponent ofwomen's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. As chairman of the judiciary committee of a New York State constitutional convention in 1894, Root spoke against women's right to vote, and he worked to ensure that the right was not included in the state constitution. He would remain an active opponent of feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

for the rest of his career.

Personal life

Family

In 1870, Root accompanied his brother Wally, with whom he had lived in his early days in New York, on a European voyage. Wally suffered fromtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

(then known as incurable "consumption") and believed that the trip would cure his disease. The brothers were together in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

; they followed its progress throughout the summer as Wally's condition worsened. Towards the end of the trip, Elihu had to carry his brother in his arms. They returned to Clinton, where Wally died on November 15, 1870. Elihu paid off his debts.

In 1878, Root married Clara Frances Wales, the daughter of prominent New York Republican Salem Howe Wales. They had three children:

* Edith Root (b. December 1, 1878, m. Ulysses S. Grant III

Ulysses Simpson Grant III (July 4, 1881August 29, 1968) was a United States Army officer and planner. He was the son of Frederick Dent Grant, and the grandson of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army and President of the United ...

)

* Elihu Root Jr. (b. May 7, 1881, m. Alida Stryker)

* Edward Wales Root (b. July 23, 1884)

Elihu Root Jr. graduated from Hamilton College and became an attorney, like his father. He married Alida Stryker, the daughter of Hamilton College president M. Woolsey Stryker.

Religion

Root was a devoutPresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, consistent with his upbringing. Upon first moving to New York City, he enrolled as a member of the Young Men's Christian Association, served as its vice president, contributed essays on Christian manhood to its literary society, and taught Sunday school.

Friendships and professional associations