Edward Lloyd (singer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

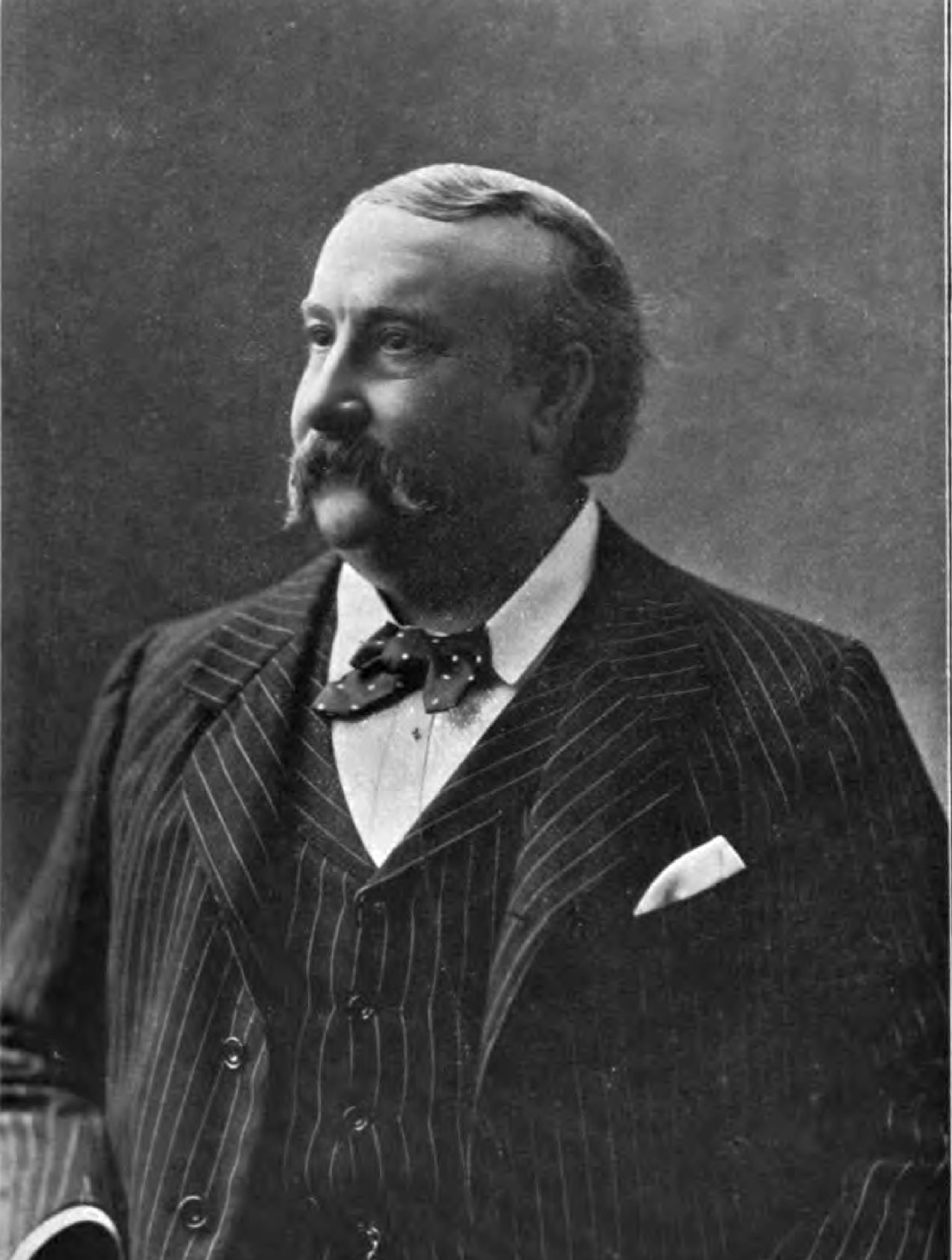

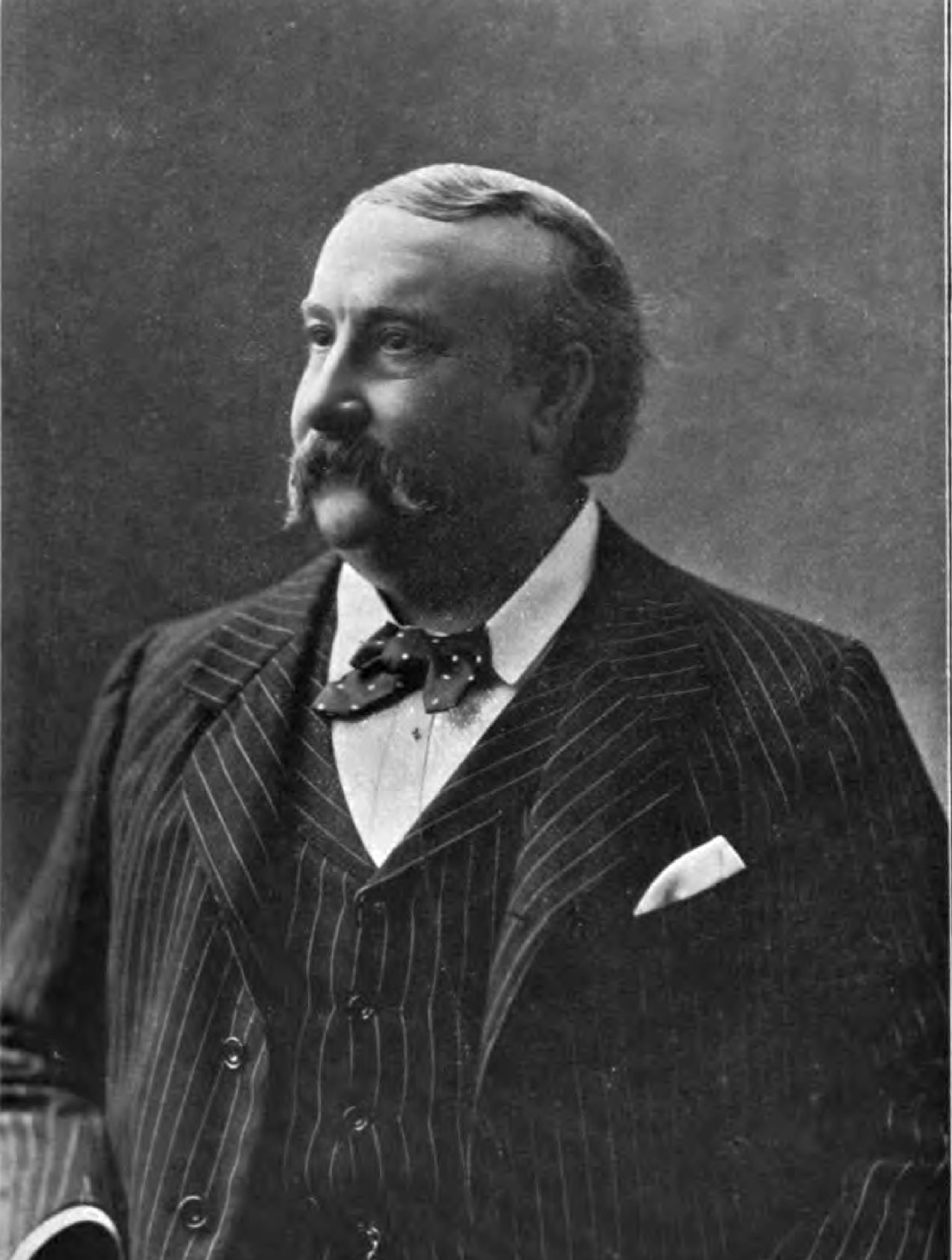

Edward Lloyd (7 March 1845 – 31 March 1927) was a British

In 1877, when

In 1877, when

Lloyd was very active during the heyday of

Lloyd had an ovation at

tenor

A tenor is a type of male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. Composers typically write music for this voice in the range from the second B below m ...

singer who excelled in concert and oratorio

An oratorio () is a musical composition with dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists and orchestra or other ensemble.

Similar to opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguisha ...

performance, and was recognised as a legitimate successor of John Sims Reeves

John Sims Reeves (21 October 1821 – 25 October 1900) was an English operatic, oratorio and ballad tenor vocalist during the mid-Victorian era.

Reeves began his singing career in 1838 but continued his vocal studies until 1847. He soon establ ...

as the foremost tenor exponent of that genre during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Early training in choral tradition

Edward Lloyd was born in London, into a musical family. His mother was Louise Lloyd, née Hopkins, of the well-known Hopkins musical family. His father Richard Lloyd had, by invitation, assisted as a counter-tenor on 'Show Sundays' atWorthing

Worthing ( ) is a seaside town and borough in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 113,094 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Br ...

when choral concerts were directed by the fourteen-year-old Sims Reeves. Young Lloyd began singing as a chorister at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, and in 1866 became a member of both Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

and King's College chapels in the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. In 1869 he joined the choir of St Andrew's, Wells Street (under Barnby) and was engaged for the Chapel Royal

A chapel royal is an establishment in the British and Canadian royal households serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the royal family.

Historically, the chapel royal was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarc ...

in 1869–71. In 1871 he sang in the St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets the 26th and 27th chapters of th ...

at the Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

Festival, and came prominently to public attention. He never sang in the theatre, possibly because he was short of stature (Charles Santley

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English opera and oratorio singer with a ''bravura''From the Italian verb ''bravare'', to show off. A florid, ostentatious style or a passage of music requiring technical skill ...

heard him described as 'a nice, plump little gentleman.'). In 1873 he made his first appearance at St James' Hall with the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

. In the year of his retirement in 1900, he became the Gold Medallist of that Society.

Vocal characteristics

Herman Klein

Herman Klein (born Hermann Klein; 23 July 1856 – 10 March 1934) was an English music critic, author and teacher of singing. Klein's famous brothers included Charles Klein, Charles and Manuel Klein. His second wife was the writer Kathleen Cla ...

, who heard Lloyd early in his career, was surpassingly impressed by his voice and delivery. He called its quality 'most exquisite', with an amazingly smooth legato, comparable to the great tenor Antonio Giuglini

Antonio Giuglini (16 or 17 January 1825 – 12 October 1865) was an Italian operatic tenor. During the last eight years of his life, before he developed signs of mental instability, he earned renown as one of the leading stars of the operatic ...

. "Edward Lloyd's is one of those pure, natural voices that never lose their sweetness, but preserve their charm so long as there are breath and power to sustain them. His method is, to my thinking, irreproachable and his style absolutely inimitable. His versatility was greater than that of Sims Reeves, though he was never a stage tenor; for he was equally at home in music of every period and of every school. In Bach and Handel, in modern oratorio, in the Italian aria, in Lied, romance or ballad, he was equally capable of arousing genuine admiration." His performance of 'Love in her eyes sits playing' (Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

, ''Acis and Galatea

Acis and Galatea (, ) are characters from Greek mythology later associated together in Ovid's ''Metamorphoses''. The episode tells of the love between the mortal Acis and the Nereid (sea-nymph) Galatea; when the jealous Cyclops Polyphemus kil ...

'') he called 'absolutely unsurpassable', and greater than any Handelian singing heard thereafter. This extremely high praise came from a most discerning critic. David Bispham

David Scull Bispham (January 5, 1857 – October 2, 1921) was an American operatic baritone.

Biography

Bispham was born on January 5, 1857, in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalitie ...

considered him the foremost tenor of the concert platform.

Handel Festivals and the mantle of Reeves

In 1877, when

In 1877, when Sims Reeves

John Sims Reeves (21 October 1821 – 25 October 1900) was an English operatic, oratorio and ballad tenor vocalist during the mid-Victorian era.

Reeves began his singing career in 1838 but continued his vocal studies until 1847. He soon establ ...

withdrew from his engagement for the Handel Triennial Festival at the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

over the controversy concerning Concert pitch

Concert pitch is the pitch reference to which a group of musical instruments are tuned for a performance. Concert pitch may vary from ensemble to ensemble, and has varied widely over time. The ISO defines international standard pitch as A440, ...

, Lloyd was engaged instead. He had performed there in ''Acis and Galatea'' in 1874, and participated in every subsequent festival there until his retirement in 1900. In these performances before huge audiences in that immense space, his beautiful, resonant and clarion voice carried wonderfully. These festivals might include full performances of ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

'', ''Israel in Egypt

''Israel in Egypt'', HWV 54, is a biblical oratorio by the composer George Frideric Handel. Most scholars believe the libretto was prepared by Charles Jennens, who also compiled the biblical texts for Handel's ''Messiah''. It is composed enti ...

'' and ''Judas Maccabaeus

Judas Maccabaeus or Maccabeus ( ), also known as Judah Maccabee (), was a Jewish priest (''kohen'') and a son of the priest Mattathias. He led the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire (167–160 BCE).

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah ("Ded ...

'' on successive nights, each being exceptionally demanding for the tenor (but extremely rewarding for one equal to the task). The earliest 'live' recording of a British concert was made at the Crystal Palace 1888 Festival performance of ''Israel in Egypt'', in which Lloyd was the principal tenor, though unfortunately the selections on the surviving three wax cylinder records do not include any of his actual singing.

Creator of Oratorio roles

Lloyd created many of the great tenor roles in late Victorian oratorio and concert works. In the Hallé Concerts atManchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

he appeared with Charles Santley and Anna Williams in the first performance of an oratorio by Edward Hecht. More significantly, he created lead roles in ''The Martyr of Antioch

''The Martyr of Antioch'' is a choral work described as a "Sacred Musical Drama" by the English composer Arthur Sullivan. It was first performed on 15 October 1880 at the triennial Leeds Festival (classical music), Leeds Music Festival, having be ...

'' (Leeds Festival

The Reading and Leeds Festivals are a pair of annual music festivals that take place in Reading, Berkshire, Reading and Leeds in England. The events take place simultaneously on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday of the August bank holiday weekend ...

1880) and ''The Golden Legend

The ''Golden Legend'' ( or ''Legenda sanctorum'') is a collection of 153 hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that was widely read in Europe during the Late Middle Ages. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived.Hilary Maddo ...

'' (1886) of Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

; in the ''Judith

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical book included in the Septuagint and the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Christian Old Testament of the Bible but Development of the Hebrew Bible canon, excluded from the ...

'' (1888) and ''King Saul

Saul (; , ; , ; ) was a monarch of ancient Israel and Judah and, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament, the first king of the United Monarchy, a polity of uncertain historicity. His reign, traditionally placed in the late elevent ...

'' of Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 1848 – 7 October 1918), was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill, Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is ...

; and in the ''La rédemption

''La Rédemption'' (''The Redemption'') is an oratorio in three parts by Charles Gounod arranged for the first time in 1882.

Composition

''La Rédemption'' is based on much earlier sketches, which were finished only after his publisher, Novello, ...

'' (Birmingham Triennial Music Festival

The Birmingham Triennial Musical Festival, in Birmingham, England, founded in 1784, was the longest-running European classical music, classical music festival of its kind. It last took place in 1912.

History

The first music festival, over th ...

, 1882) and '' Mors et Vita'' (1884) of Charles Gounod

Charles-François Gounod (; ; 17 June 181818 October 1893), usually known as Charles Gounod, was a French composer. He wrote twelve operas, of which the most popular has always been ''Faust (opera), Faust'' (1859); his ''Roméo et Juliette'' (18 ...

. Lloyd was, therefore, entirely identified with the largest works of the Sacred Musical Drama so characteristic of his age.

The early 1890s in London

OratorioLloyd was very active during the heyday of

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

's reviewing days. Shaw thought Lloyd in his best vein in Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonie ...

's ''St. Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally ...

'' at the Crystal Palace in November 1889; in June 1890 he found the massed performance (3000 executants) an ordeal, but thought Edward Lloyd sang 'without a fault', when Watkin Mills Watkin is an English surname formed as a diminutive of the name Watt (also Wat), a popular Middle English given name itself derived as a pet form of the name Walter.

First found in a small Welsh village in 1629.

Within the United Kingdom it is asso ...

and Mme Patey were in excellent form and Mme Albani

Dame Emma Albani, DBE (born Marie-Louise-Emma-Cécile Lajeunesse; 1 November 18473 April 1930) was a Canadian-British operatic coloratura soprano, later spinto soprano and dramatic soprano of the 19th and early 20th century, the first Canadian ...

her usual self. Shaw despised the massed festivals, but usually much admired Lloyd. In June 1891 at Crystal Palace, if Santley was the hero of the hour, Lloyd was delightful in ''Love in her eyes sits playing'' and in one of the ''Chandos Anthems

''Chandos Anthems'', Händel-Werke-Verzeichnis, HWV 246–256, is the common name of a set of anthems written by George Frideric Handel. These sacred choral compositions number eleven; a twelfth of disputed authorship is not considered here. T ...

''. But he was out of sorts for ''The enemy said'' on the following night, though he had to repeat it, and sustained his reputation.

Lloyd was good again at Birmingham in October, and in a Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

concert aria in the December centenary celebration. In June 1892 a proposed Crystal Palace performance of Handel's ''Samson

SAMSON (Software for Adaptive Modeling and Simulation Of Nanosystems) is a computer software platform for molecular design being developed bOneAngstromand previously by the NANO-D group at the French Institute for Research in Computer Science an ...

'' was substituted by the familiar ''Judas Maccabaeus'' to spare Lloyd the difficulty of the new role. However the ''Judas'' came off well, with the usual line-up of Santley, Lloyd, Albani and Patey. He appeared on 2 December 1893 at the official opening of the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

, in Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonie ...

's ''Hymn of Praise'', with Mme Albani and Margaret Hoare, under the direction of Frederick Cowen

Sir Frederic Hymen Cowen (29 January 1852 – 6 October 1935), was an English composer, conductor and pianist.

Early years and musical education

Cowen was born Hymen Frederick Cohen at 90 Duke Street, Kingston, Jamaica, the fifth and last c ...

. In 1894 it was again ''Love in her eyes'' which Lloyd sang to perfection, though again he, Mme Albani, Ben Davies and Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic lyric coloratura soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early twentieth century, and was the f ...

all had to accord first place in popular esteem to Charles Santley, who received stupendous applause. On Jubilee Sunday 1897 he performed the Mendelssohn ''Hymn of Praise'' with Mme Albani and Agnes Nicholls

Agnes Helen Nicholls CBE (14 July 1876 – 21 September 1959) was one of the greatest English sopranos of the 20th century, both in the concert hall and on the operatic stage.

Born in Cheltenham, Nicholls was the daughter of a director of Ca ...

.

Concert operaLloyd had an ovation at

St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones (architect), Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regen ...

for his ''Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

's forging scene'' in July 1888 under Hans Richter. The Philharmonic orchestra gave him a 'mundane' accompaniment in Lohengrin's grail narration in January 1889, and in Siegfried's forge his laugh was too well-bred, 'hardly the exultant shout of a young giant over his anvil'; and William Nicholl was out of tune as Mime. In July 1889 even Richter's wonderful conducting of Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

's ''Damnation of Faust

''La Damnation de Faust'' (English: ''The Damnation of Faust''), Op. 24 is a French musical composition for four solo voices, full seven-part chorus, large children's chorus and orchestra by the French composer Hector Berlioz. He called it a ' ...

'' could not (for Shaw) redeem Lloyd's 'wanton tampering' and 'annoyingly vulgar alteration' of important passages, and even in performances a few years later did not quite forget it, though he admitted Lloyd had set a standard in the work.

In March 1890 his 'Preislied' from ''Meistersinger

A (German for "master singer") was a member of a German guild for lyric poetry, composer, composition and a cappella, unaccompanied art song of the 14th to 16th centuries. The Meistersingers were drawn from middle class males for the most part ...

'' was the key attraction at Crystal Palace. In July 1890, Lloyd 'sang well', but tended to 'jingoism', 'genteel piety' and 'sentimentality' in the ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wo ...

'' Act 3 under Richter, but 'he was not Lohengrin.' In March 1891 his ''Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; ), often stylized "The Tannhäuser", was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and 1265.

His name ...

'' in a concert performance of the last act was 'beyond cavil'. At the Richter concert of June 1891 he sang Tannhäuser's ''Rome Narrative'' and the Siegfried forging music 'very tunefully and smoothly, without, however, for a moment relinquishing his original character as Mr Edward Lloyd.' In the ''Lohengrin'' and ''Tannhäuser'' third acts repeated at Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

in May 1894, Lloyd was 'playing a little to the gallery by a style of declamation not exactly classic, though sufficiently sincere and effective.'

Elgar: ''Caractacus'' and ''Gerontius''

As the creator of Sacred roles, it was natural that he was chosen to give first performances of lead roles inElgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

's ''Caractacus

Caratacus was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the Catuvellauni tribe, who resisted the Roman conquest of Britain.

Before the Roman invasion, Caratacus is associated with the expansion of his tribe's territory. His apparent success led ...

'' (1898) and ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Opus number, Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from The Dream of Gerontius (poem), the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man' ...

'', in which the form entirely broke free from the older 'Sacred cantatas' (a term Elgar specifically forbade with reference to ''Gerontius''.) It is well known that the first performance of the latter, which occurred on 3 October 1900 under the baton of Hans Richter at the Birmingham Festival, was a disaster. Having created Caractacus, Lloyd had adapted himself to Elgar's musical idiom. He was certainly very nervous and, far from underestimating the task, suffered great anxiety on this occasion, being near the end of his career and not in particularly good voice. The long and taxing nature of the role, and the frequent standing up to sing and sitting down again, had an unfortunate effect.

In that performance Harry Plunket Greene

Harry Plunket Greene (24 June 1865 – 19 August 1936) was an Irish baritone who was most famous in the formal concert and oratorio repertoire. He wrote and lectured on his art, and was active in the field of musical competitions and examinatio ...

sang the baritone roles and the angel was sung by Marie Brema

Marie Brema (28 February 1856 – 22 March 1925) was a British dramatic mezzo-soprano active in concert, operatic and oratorio roles during the last decade of the 19th and the first decade of the 20th centuries. She was the first British singer ...

. ''Gerontius'' was not only the pivot of Elgar's career as a composer, but a transforming event in musical history. Lloyd's career, rooted in an older musical idiom, was by then almost complete and it was left to a younger generation, notably the tenors John Coates and Gervase Elwes

Gervase Henry Cary-Elwes, DL (15 November 1866 – 12 January 1921), better known as Gervase Elwes, was an English tenor of great distinction, who exercised a powerful influence over the development of English music from the early 1900s up u ...

, to immortalise both the new dynamic of the music, and themselves, in its full spiritual realisation. Elgar still hoped for Edward Lloyd to appear at a festival at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

in March 1904, (to include ''Gerontius'', '' The Apostles'' and ''Caractacus'') but his wish remained unfulfilled: 'the great man will not emerge'. Instead John Coates took the first two roles and Lloyd Chandos the third.

Farewell

After almost thirty years before the public Edward Lloyd gave his farewell concert at theRoyal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

in December 1900, two months after the ''Gerontius'' premiere. Herman Klein

Herman Klein (born Hermann Klein; 23 July 1856 – 10 March 1934) was an English music critic, author and teacher of singing. Klein's famous brothers included Charles Klein, Charles and Manuel Klein. His second wife was the writer Kathleen Cla ...

said that, like his great predecessor Sims Reeves (who had died in October 1900), although Lloyd was quite unlike him in character of voice and method, both exemplified the purest attributes of the ''bel canto'' and upheld the best traditions of the British oratorio school.

Klein thought him more versatile than Reeves, at home in every period and school in music. In Bach and Handel, modern oratorio, Italian aria, Lied, romance and ballad, he was equally capable of arousing admiration: and he could declaim Wagner with a beauty of tone, a fullness of dramatic expression, and a clarity of enunciation that made his German audiences in London shout for very wonder and delight.' Richter considered he was the first tenor to do justice to the Preislied from ''Meistersinger''.

In February 1907 he ceremonially cut the first sod at the site of the Hayes, Middlesex

Hayes is a town in west London. Historically situated within the county of Middlesex, it is now part of the London Borough of Hillingdon. The town's population, including its localities Hayes End, Harlington and Yeading, was recorded in the ...

factory of the Gramophone Company

The Gramophone Company Limited was a British phonograph manufacturer and record label, founded in April 1898 by Emil Berliner. It was one of the earliest record labels.

The company purchased the His Master's Voice painting and trademark righ ...

, Ltd (later HMV).''Opera at Home'' 3rd, Revised, edition 1925, reprint with addenda 1927 (Gramophone Co., London), p. 465. Photograph of Edward Lloyd cutting the first sod at Hayes. He emerged from retirement to sing at the Coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

of George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

in 1911, and at a Benefit Concert in 1915. He died in Worthing

Worthing ( ) is a seaside town and borough in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 113,094 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Br ...

.

Recordings: Discography

The following records were made by Lloyd for theGramophone Company

The Gramophone Company Limited was a British phonograph manufacturer and record label, founded in April 1898 by Emil Berliner. It was one of the earliest record labels.

The company purchased the His Master's Voice painting and trademark righ ...

. They give a fair sample of his ballad repertoire at this date (1904–11), with key representations of his Handel, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Gounod, Balfe and Sullivan. This list is possibly complete.

* 3-2024 I'll sing thee songs of Araby (Clay). 1904

* 3-2025 Tom Bowling (Dibdin). 1904

* 3-2026 The Holy City (Adams). 1904

* 3-2027 The Death of Nelson (Braham). 1904

* 3-2028 ''Alice, Where Art Thou?

''Alice, Where Art Thou?'' is a popular British parlour song of the Victorian era. It was composed by Joseph Ascher. The text was by Wellington Guernsey, although it is sometimes attributed to Alfred Bunn, who is best known for " I Dreamt I Dwel ...

'' (Asher). 1904

* 3-2029 Let me like a soldier fall, ''Maritana

''Maritana'' is a three-act opera including both spoken dialogue and some recitatives, composed by William Vincent Wallace, with a libretto by Edward Fitzball (1792–1873). The opera is based on the 1844 French play ''Don César de Bazan'' b ...

'' (Wallace). 1904

* 3-2081 When all the world is fair (Cowen). 1904

* 3-2082 The sea hath its pearls (Cowen). 1904

* 3-2083 When other lips, ''Bohemian Girl'' (Balfe). 1904

* 3-2085 If with all your hearts, ''Elijah'' (Mendelssohn). 1904

* 3-2086 Lend me your aid, ''Reine de Saba'' (Gounod). 1904

* 3-2087 The maid of the mill (Clay). 1904

* 3-2294 Bonnie Mary of Argyle (Landon Ronald, pno). 1905

* 3-2299 The minstrel Boy (Moore).1905

* 3-2801 If with all your hearts, ''Elijah'' (Mendelssohn). 1906–07

* 3-2802 Then shall the righteous shine, ''Elijah'' (Mendelssohn). 1906–07

* 3-2855 Come, Margherita, come, ''Martyr of Antioch'' (Sullivan). 1907

* 3-2856 Awake, awake (Piatti). 1907

* 3-2865 Alice, where art thou? (Asher). 1907

* 3-2870 The song of the south (E Lloyd). 1907

* 3-2889 A farewell (Liddle). 1907

* 3-2922 The sea hath its pearls (Cowen). 1907–08

* 3-2938 Bonnie Mary of Argyle (Nelson). 1908

* 02062 Lend me your aid, ''Irene'' (Gounod). 1905

* 02063 Prize song, ''Meistersinger'' (Wagner). 1905

* 02087 Fleeting years (Greene). 1907

* 02088 Come into the garden, Maud (Balfe). 1907

* 02090 Sing me to sleep (Greene). 1907

* 02095 I'll sing thee songs of Araby (Clay). 1907

* 02101 The minstrel boy (Moore). 1907

* 02118 (a) Songs my mother taught me (Dvořák),(b) Tune thy strings, o gipsy (Dvořák). 1908

* 02123 Sound an alarm, ''Judas Maccabaeus'' (Handel). 1908

* 02139 The star of Bethlehem (Adams) 1908

* 02157 The Holy City (Adams). 1908

* 04792 Rejoice in the Lord (J F Bridge). 1911

Sources

* Bennett, J.R., ''Voices of the Past: I. A Catalogue of Vocal recordings from the English Catalogue of the Gramophone Company, etc'' (?Oakwood Press, 1955). * Bispham, D, ''A Quaker Singer's Recollections'' (Macmillan, New York 1920). * Eaglefield-Hull, A. (Ed''), A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians'' (Dent, London 1924). * Elkin, R., ''Queen's Hall 1893–1941'' (Rider & co, London 1944). * Elkin, R., ''Royal Philharmonic: The Annals of the Royal Philharmonic Society'' (Rider & co, London 1946). * Klein, H., ''Thirty Years of Musical Life in London, 1870–1900'' (Century Co, New York 1903). * Santley, C., ''Reminiscences of my Life'' (Isaac Pitman, London 1909). * Scott, M., ''The Record of Singing to 1914'' (Duckworth, London 1977). * Shaw, G.B., ''Music in London 1890–1894'' (Collected edition, 3 Vols)(Constable, London 1932). * Shaw, G.B., ''London Music in 1888–89 as heard by Corno di Bassetto'' (Constable, London 1937). * Young, P.M., ''Letters of Edward Elgar'' (Geoffrey Bles, London 1956). * ''Opera at Home'', 3rd edition, reprint with addenda, (The Gramophone Company, 1927).References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lloyd, Edward 1845 births 1927 deaths English tenors Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Singers from London Choristers at Westminster Abbey 19th-century British male singers