Republicanism in the Netherlands is a movement that strives to abolish the

Dutch monarchy

The monarchy of the Netherlands is governed by the country's charter and constitution, roughly a third of which explains the mechanics of succession, accession, and abdication; the roles and duties of the monarch; the formalities of communica ...

and replace it with a

republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

. The popularity of the organised

republican movement that seeks to abolish the monarchy in its entirety has been suggested to be a minority among the people of the Netherlands, according to opinion polls (according to one 2023 poll, 37%).

Terminology

In discussions on forms of government, it is common to refer to certain 'models', based on how other countries are constituted:

*Spanish model: a

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

in which the monarch at least nominally has limited political power.

*Swedish model: a constitutional monarchy in which the monarch has an entirely

ceremonial role in law as well as in fact.

*German model: a

parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the Executive (government), executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). ...

in which Parliament elects the President who serves as head of state and who has little to no power.

*American model: a

presidential republic

A presidential, strong-president, or single-executive system (sometimes also congressional system) is a form of government in which a head of government (usually titled " president") heads an executive branch that derives its authority and l ...

in which the President is elected by the people and serves as head of state and head of government.

*French model: a

semi-presidential republic

A semi-presidential republic, or dual executive republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliament ...

in which the President is directly elected by the population and shares power with a Prime Minister.

[Van den Bergh (2002), p. 42.]

Historical development

1581–1795: Dutch Republic

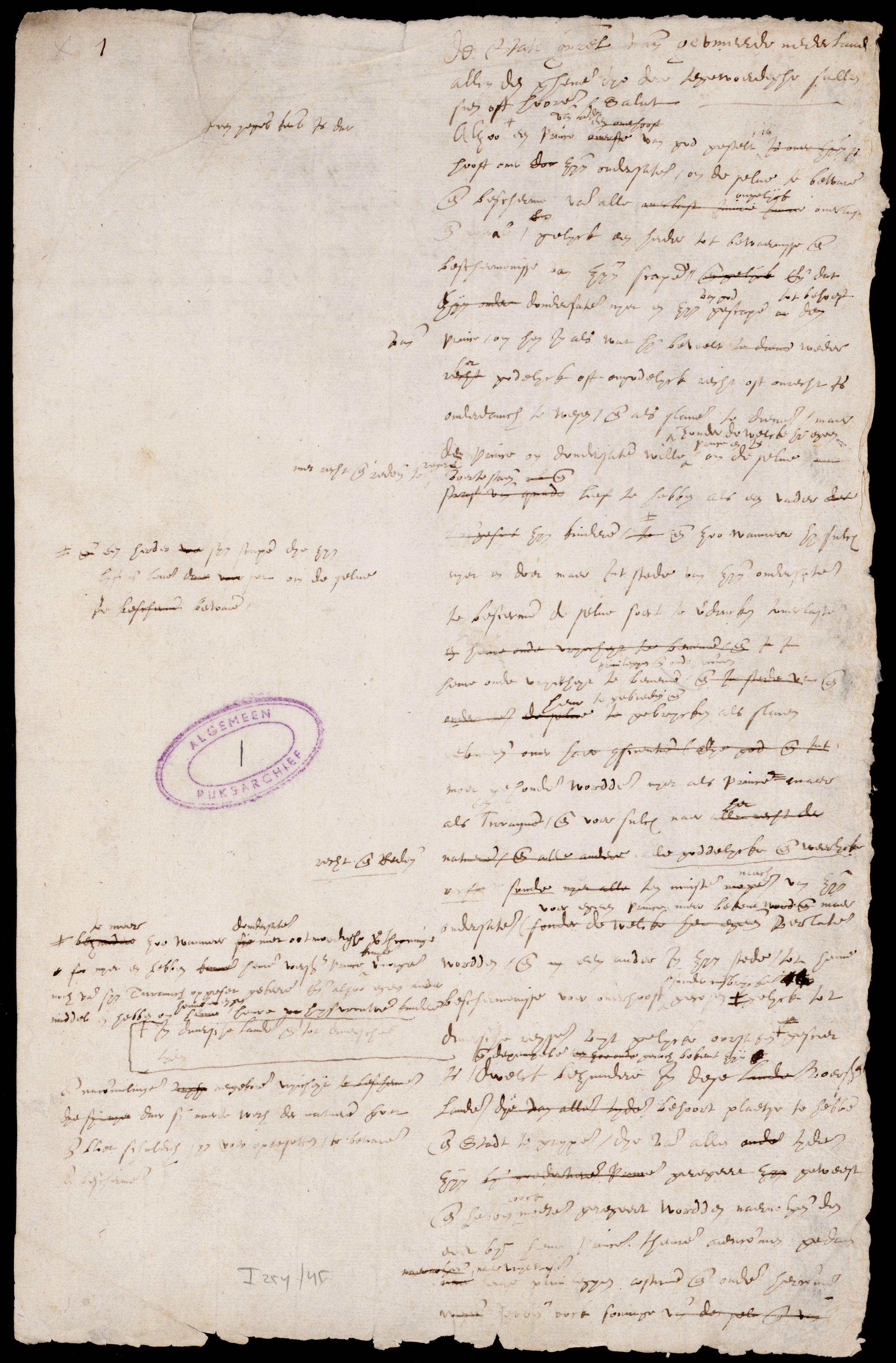

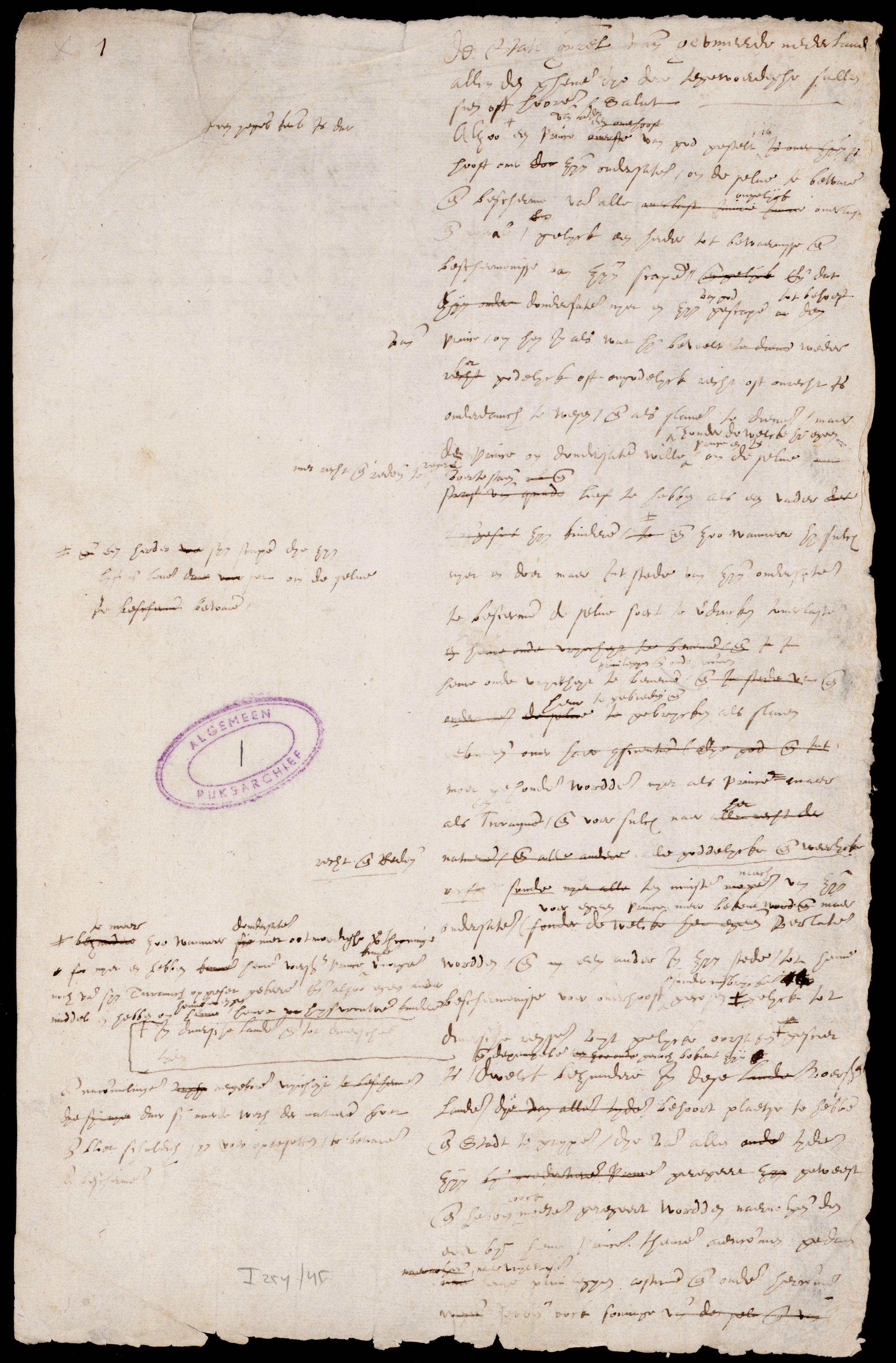

Establishment of the Republic

The Netherlands emerged as a state during the

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

(1568–1648), declaring their independence from the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

in 1581. After futile attempts to find a hereditary head of state, the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

was proclaimed in 1588. However, the war initially had neither the achievement of political independence nor the establishment of a republic as its ultimate goal, nor were the

Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the ...

excluded from it on purpose. Rather, the inability of the Habsburg regime to adequately address religious, social and political unrest (that was originally most pressing in

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

and

Brabant), led to an irreconcilable situation. An independent Calvinist-dominated republic in the Northern Netherlands, opposed to the continuously Spanish Catholic-dominated royalist Southern Netherlands, was the unintended, improvised result. As the war progressed however, the

House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau (, ), also known as the House of Orange because of the prestige of the princely title of Orange, also referred to as the Fourth House of Orange in comparison with the other noble houses that held the Principality of Or ...

played an increasingly important role, finally accumulating all

stadtholder

In the Low Countries, a stadtholder ( ) was a steward, first appointed as a medieval official and ultimately functioning as a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and ...

ates and military leadership positions within the Dutch Republic by 1590. Struggles between the House of Orange, which gradually built up a dynasty with monarchical aspirations, and the

Dutch States Party

The Dutch States Party () was a republican political faction, and one of the two main factions of the Dutch Republic from the early 1600s to the mid-1700s. They favored the power of the ''regenten'' and opposed the Orangist "pro-prince" (''prin ...

, a loose coalition of factions that favoured a republican, in most cases more or less

oligarchical

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or through ...

form of government, continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Loevesteiners and Enlightenment

In 1610, lawyer

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius ( ; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Hugo de Groot () or Huig de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, statesman, poet and playwright. A teenage prodigy, he was born in Delft an ...

(1583–1645) wrote ''On the Antiquity of the Batavian Republic'', which attempted to show the States of Holland had always been sovereign (even since the

Batavians

The Batavi were an ancient Germanic tribe that lived around the modern Dutch Rhine delta in the area that the Romans called Batavia, from the second half of the first century BC to the third century AD. The name is also applied to several mil ...

), and could appoint or depose a prince whenever they so desired. The works' main purpose was to justify the Revolt against the Spanish Empire, and the independent existence of the emergent Dutch Republic.

Modern historians agree that ever since the stadtholderate of

Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

Frederick Henry (; 29 January 1584 – 14 March 1647) was the sovereign prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from his older half-brother's death on 23 April 1625 until his ...

(1625–1647), the Princes of Orange had sought to turn the Dutch Republic into a monarchy under their rule. The 1650 imprisonment of several pro-States regenten and a

failed coup d'état by Frederick Henry's son and successor, stadtholder

William II, Prince of Orange

William II (Dutch language, Dutch: ''Willem II''; 27 May 1626 – 6 November 1650) was sovereign Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrecht, Guelders, Lordship of Ove ...

, led to the rise of the

Loevestein faction

The Loevestein faction () or the Loevesteiners were a Dutch States Party in the second half of the 17th century in the County of Holland, the dominant province of the Dutch Republic. It claimed to be the party of "true freedom" against the stad ...

under leadership of

Johan de Witt

Johan de Witt (24 September 1625 – 20 August 1672) was a Dutch statesman and mathematician who was a major political figure during the First Stadtholderless Period, when flourishing global trade in a period of rapid European colonial exp ...

, which sought to establish a republic without Orange.

Indeed, after William II's failed power grab and unexpected death, the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders and Overijssel decided not to appoint a new stadtholder at all, beginning the

First Stadtholderless Period

The First Stadtholderless Period (1650–72; ) was the period in the history of the Dutch Republic in which the office of Stadtholder was vacant in five of the seven Dutch provinces (the provinces of Friesland and Groningen (province), Groningen, ...

(1650–1672/5) in five of the seven United Provinces.

Moreover, after the Dutch Republic was defeated by the

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

in the

First Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

(1652–1654), the States of Holland led by Johan de Witt were forced to sign the

Act of Seclusion

The Act of Seclusion was an Act of the States of Holland, required by a secret annex in the Treaty of Westminster (1654) between the United Provinces and the Commonwealth of England in which William III, Prince of Orange, was excluded from the ...

, meaning William's son

William III of Orange

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 167 ...

was excluded from holding the office of stadtholder of Holland.

The legitimacy of necessity of the strange office of stadtholder was increasingly questioned and undermined, especially when it seemed evident that the House of Orange sought to make the office hereditary and had shown the willingness to use military violence in order to increase the stadtholderate's power.

The best known and most outspoken author representing the Loevesteiners was

Pieter de la Court

Pieter de la Court (1618 – May 28, 1685) was a Dutch economist and businessman, he is the progenitor of the De la Court family. He thought about the economic importance of free competition and was an advocate of the republican form of gov ...

(1618–1685), who rejected monarchism in favour of a republican government in several of his writings. In the preface to the ''Interest of Holland'' (1662) he wrote: "No greater evil could befall the residents of Holland, than to be ruled by a Monarch, Lord or Chief: and (...) on the contrary, the Lord God cannot bestow a greater blessing upon a country, built on such foundations, than by constituting a free Republican or State-wise Government." In ''Aanwysing der heilsame politike Gronden en Maximen van de Republike van Holland en West-Vriesland'' (1669), he attacked the monarchy even more viciously.

Philosopher

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

(1632–1677), who regularly cited De la Court's works, described in his unfinished ''Tractatus Politicus'' (1677) how the ideal state, a democratic republic, should function. According to Spinoza, kings have a natural tendency to pursue their own personal interests, and entrust large portions of power to confidants (who lack any official mandate, but often ''de facto'' run the country if the king is a weakling). These confidants are often noblemen, making it an aristocracy instead of a monarchy in practice. The best monarchy is a quasi-monarchy, a

crowned republic

A crowned republic, also known as a monarchical republic, is a system of monarchy where the monarch's role is almost entirely ceremonial and where nearly all of the royal prerogatives are exercised in such a way that the monarch personally has ...

in which princes have as little power as possible. Spinoza proposes a council of state, elected by citizens, to take the most important decisions, and replace the murderous and pillaging royal mercenary armies by an unpaid draft army of citizens that defends its own country for self-preservation. If this council of state is large and representative enough, there will never be a majority in favour of war, because of all the suffering, destruction and high taxes it will cause.

Pastor and philosopher

Frederik van Leenhof

Frederik van Leenhof (1 September 1647 – 13 October 1715) was a Dutch pastor and philosopher active in Zwolle, who caused an international controversy because of his Spinozist work ''Heaven on Earth'' (1703). This controversy is extensively ...

(1647–1715), who secretly admired the ideas of the very controversial Spinoza, held a thinly veiled plea for a kind of

meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods or political power are vested in individual people based on ability and talent, rather than ...

republic in ''De Prediker van den wijzen en magtigen Konink Salomon'' (1700), whilst rejecting monarchy ("without doubt the most imperfect

ule

Ule is a German surname

Personal names in German-speaking Europe consist of one or several given names (''Vorname'', plural ''Vornamen'') and a surname (''Nachname, Familienname''). The ''Vorname'' is usually gender-specific. A name is usually ...

) and

aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

. Hereditary succession is worthless; only

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

provides legitimacy, and true sovereignty is the common good of the community. Royal

standing armies

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

of

mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

are to be abolished, lest they be used to oppress the king's subjects; instead, the state should train its citizens and form a militia to be able to defend the common good.

Patriots

From the 1770s onwards, the

Patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

emerged as a third faction besides the Orangists and Loevesteiners. The Patriots were themselves divided: the aristocratic ''oudpatriotten'' or "Old Patriots" (the Loevesteiners' successors) either sought to enter the existing power factions, or to reduce or eliminate Orange's power, but had no desire for democratisation that could threaten their own privileges. The democratic Patriots wanted to found a

democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democracies.

Whil ...

, sought complete equality and the eventual abolishment of the aristocracy as well. As the latter group grew in size and radicalised, this led some Old Patriots to reverse their allegiance back to Orange.

[Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "patriotten". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.]

Discontented with the hereditary system of allocating posts, the decline of the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

's Asian trade, unemployment in the textile industry and the desire of democratisation, the middle and upper classes looked towards the

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and its

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

and the Dutch

Act of Abjuration

The Act of Abjuration (; ) is the declaration of independence by many of the provinces of the Netherlands from their allegiance to Philip II of Spain, during the Dutch Revolt.

Signed on 26 July 1581, in The Hague, the Act formally confirmed a ...

and began to reclaim their rights (first written down in the 1579

Union of Utrecht

The Union of Utrecht () was an alliance based on an agreement concluded on 23 January 1579 between a number of Habsburg Netherlands, Dutch provinces and cities, to reach a joint commitment against the king, Philip II of Spain. By joining forces ...

). The lower classes largely remained supportive of the existing Orange stadtholderian regime, which supported the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

against the American rebels. 1780 is generally regarded as the outbreak of the major conflict between Patriots and Orangists, when their opposing policies on the American War of Independence stirred up domestic conflict. When the Republic threatened to join the

First League of Armed Neutrality

The First League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance of European naval powers between 1780 and 1783 which was intended to protect neutral shipping against the British Royal Navy's wartime policy of unlimited search of neutral shipping for Frenc ...

to defend its right to trade with the American colonies in revolt, Britain declared war: the

Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (; 1780–1784) was a conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The war, contemporary with the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), broke out over British and Dutch disagreements on t ...

(1780–1784). The Patriots seized the occasion to try to rid themselves from Orange altogether, and allied themselves with the American republican revolutionaries. This was most clearly expressed in the 1781 pamphlet ''

Aan het Volk van Nederland

''Aan het Volk van Nederland'' (; English: ''To the People of the Netherlands'') was a pamphlet distributed by window covering, window-covered carriages across all major cities of the Dutch Republic in the night of 25 to 26 September 1781. It cla ...

'' ("To the People of the Netherlands"), anonymously distributed by

Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol. Partly thanks to his influence in the

States General, the Netherlands became the second country to officially recognise the young

American Republic in 1782. Between 1782 and 1787, democratic Patriotism managed to establish itself in parts of the Republic. From 1783 onwards, the Patriots formed

militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

or

paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

groups called ''

exercitiegenootschap

An exercitiegenootschap (, ''exercise company'') or militia was a military organisation in the 18th century Netherlands, in the form of an armed private organization with a democratically chosen administration, aiming to train the citizens and th ...

pen'' or ''

vrijcorpsen''.

[, 49.] They tried to persuade the prince and city governments to allow non-

Calvinists

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

into the

vroedschap

The ''vroedschap'' () was the name for the (all male) city council in the early modern Netherlands; the member of such a council was called a ''vroedman'', literally a "wise man". An honorific title of the ''vroedschap'' was the ''vroede vadere ...

. In 1784, they held their first national meeting. The total number of Patriot volunteer militiamen is estimated to have been around 28,000.

The provinces of Holland and Utrecht became strongholds of democratic Patriots in 1785, and William V fled from The Hague to

Nijmegen

Nijmegen ( , ; Nijmeegs: ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and the ninth largest of the Netherlands as a whole. Located on the Waal River close to the German border, Nijmegen is one of the oldest cities in the ...

that year.

In 1787, he was finally able to restore his power with the

Prussian invasion of Holland

The Prussian invasion of Holland was a military campaign under the leadership of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, against the rise of the democratic Patriottentijd, Patriot movement in the Dutch Republic in September–October 1787 ...

. Many Patriots fled the country to Northern France.

French revolutionaries supported by the

Batavian Legion (consisting of fled Patriots)

conquered the Dutch Republic in 1795, founding the

vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic (; ) was the Succession of states, successor state to the Dutch Republic, Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 after the Batavian Revolution and ended on 5 June 1806, with the acce ...

.

1795–1806: Batavian Republic

The last stadtholder,

William V William V may refer to:

* William V, Duke of Aquitaine (969–1030)

* William V of Montpellier (1075–1121)

* William V, Marquess of Montferrat (1191)

* William V, Count of Nevers (before 11751181)

* William V, Duke of Jülich (1299–1361)

* Will ...

, fled with his son

William Frederick to England on 18 January 1795, where they were granted a subsidy to compensate for the loss of all their possessions in the Netherlands, confiscated by the Batavian government. After losing hope of restoring the Orange dynasty following the disastrous

Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland

The Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland (or Anglo-Russian expedition to Holland, or Helder Expedition) was a military campaign from 27 August to 19 November 1799 during the War of the Second Coalition, in which an expeditionary force of British and ...

, William Frederick commenced negotiations with First Consul

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

of the

French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

.

[Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Willem ederland§1. Willem I. Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.] His attempts to be appointed President of the Batavian Republic while forsaking his hereditary succession were unsuccessful, as were his enormous demands of 117 million

guilders

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' (" gold penny"). This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Rom ...

in compensation for the lost domains and alleged debt he demanded from the Batavian Republic.

[Van den Bergh (2002), p. 54.] In December 1801, William V issued the

Oranienstein Letters, in which he formally recognised the Batavian Republic, as Napoleon demanded as precondition for any compensation. He would later refuse Napoleon's offer of

Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a city in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the city hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

Histor ...

and

Corvey

The Princely Abbey of Corvey ( or ) is a former Benedictine abbey and ecclesiastical principality now in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was one of the half-dozen self-ruling '' princely abbeys'' of the Holy Roman Empire from the Late Middl ...

, which arguably demonstrated his selflessness.

[Encarta s.v. "Willem ederlanden§1. Willem V."] Unlike his father, however, and despite his father's protestations,

William Frederick continued pursuing more financial and territorial compensation, and eventually settled for the

Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda

Nassau-Orange-Fulda (sometimes also named ''Fulda and Corvey'') was a short-lived principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1803 to 1806. It was created for William Frederick, the son and heir of William V, Prince of Orange, the ousted stadthol ...

and a 5 million guilder indemnity by the Batavian Republic in 1802, whilst renouncing all his claims to the Netherlands. According to republicans, this demonstrated his personal greed and lack of any real devotion to the Dutch people.

Moreover, when Napoleon discovered that his vassal William Frederick was secretly plotting with Prussia and refused to join the

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine or Rhine Confederation, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austrian Empire, Austria ...

in 1806, he took Fulda from him again, after which William Frederick went into Prussian and later Austrian military service instead.

1806–1830: Early monarchies

The Netherlands became a constitutional monarchy in 1806, after

French Emperor

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First French Empire and the Second French Empire. The emperor of France was an absolute monarch.

Details

After rising to power by ...

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

appointed his younger brother

Louis Bonaparte

Louis Bonaparte (born Luigi Buonaparte; 2 September 1778 – 25 July 1846) was a younger brother of Napoleon, Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. He was a monarch in his own right from 1806 to 1810, ruling over the Kingdom of Holland (a French c ...

as vassal king over the

Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland ( (contemporary), (modern); ) was the successor state of the Batavian Republic. It was created by Napoleon Bonaparte in March 1806 in order to strengthen control over the Netherlands by replacing the republican governmen ...

which replaced the Batavian Commonwealth. After a brief annexation by France, in which Napoleon ruled directly over the Netherlands (1810–1813), William Frederick of Orange returned to restore his dynasty following Napoleon's defeat at the

Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig, also known as the Battle of the Nations, was fought from 16 to 19 October 1813 at Leipzig, Saxony. The Coalition armies of Austria, Prussia, Sweden, and Russia, led by Tsar Alexander I, Karl von Schwarzenberg, and G ...

. The anti-French reactionary and Orangist ambiance amongst the Dutch populace, and the military forces of the conservative

Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

A fraction (from , "broken") represents a part of a whole or, more generally, ...

that occupied the Low Countries, allowed him first to establish the

Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands

The Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands () was a short-lived sovereign principality and the precursor of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in which it was reunited with the Southern Netherlands in 1815. The principality was procl ...

(1813–1815), a constitutional monarchy. During the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, in which the European courts designed the

Restoration, William lobbied successfully to unite the territories of the former Dutch Republic and

Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The period began with the acquisition by the Austrian Habsburg monarchy of the former Spanish Netherlands under the Treaty of Ras ...

under his rule (confirmed by the

Eight Articles of London

The Eight Articles of London, also known as the London Protocol of 21 June 1814, were a secret convention between the Great Powers: the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Austrian Empire, and the Russian Empire (the four leading nations ...

). Next, he seized the opportunity of

Napoleon's return to assume the title of King

William I William I may refer to:

Kings

* William the Conqueror (–1087), also known as William I, King of England

* William I of Sicily (died 1166)

* William I of Scotland (died 1214), known as William the Lion

* William I of the Netherlands and Luxembour ...

of the

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed from 1815 to 1839. The United Netherlands was created in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars through the fusion of territories t ...

on 16 March 1815 (confirmed by the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna on 9 June). His authority as an

enlightened despot

Enlightened absolutism, also called enlightened despotism, refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhance ...

stretched much further now than it had even been under his stadtholder ancestors during the Dutch Republic. After the

Belgian Revolution

The Belgian Revolution (, ) was a conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

The ...

in 1830, the power of the Orange-Nassau family was again restricted to the Northern Netherlands, and the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

gradually gained influence through a series of constitutional reforms.

1830–1848: Democratisation

William I's abdication

At first, William I refused to recognise

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

's independence, and moreover he thought that if the Netherlands, then a powerful continental empire on paper, were again reduced to the old Dutch Republic's boundaries, there would be no point to a monarchy. His popularity suffered more and more because of his rejection to acknowledge Belgium, whilst maintaining an extremely expensive army that he intended to retake the South with. Opposition within the States-General became increasingly hostile until he finally agreed to sign the

Treaty of London (1839)

The Treaty of London of 1839, was signed on 19 April 1839 between the major European powers, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, and the Kingdom of Belgium. It was a direct follow-up to the 1831 Treaty of the XVIII Articles, which the Neth ...

. This necessitated a constitutional reform, during which the parliamentary opposition succeeded in introducing the principle of

ministerial responsibility

In Westminster system, Westminster-style governments, individual ministerial responsibility is a constitutional convention (political custom), constitutional convention that a Cabinet (government), cabinet minister (government), minister bears th ...

. King William vehemently detested this reform, so strongly that he was unwilling to continue his rule, and it was one of the reasons for his abdication on 7 October 1840. Another was that he threatened to lose what popularity he had left by his marriage with the half-Catholic Belgian courtesan

Henrietta d'Oultremont

Countess Henriëtte Adriana Maria Ludovica Flora d'Oultremont de Wégimont (28 February 1792 in Maastricht–26 October 1864 at Rahe Castle in Aachen) was the second, morganatic, wife of the first Dutch king, William I. Being the morganatic ...

, that many regarded as treason.

Acknowledging his failed reign in 1840, he commented "Ne veut-on plus de moi? On n'a qu'à le dire; je n'ai pas besoin d'eux." ("Don't people want me anymore? They only have to say so; I don't need them.") and that "je suis né republicain" ("I was born as a republican").

Eillert Meeter

In May 1840, journalist, publisher and republican revolutionary Eillert Meeter and 25 comrades were arrested in Groningen after removing a painting of William I from a pub and toasting on the republic. They were suspected of conspiracy against the monarchy, but released three months later because the allegations could not be proven. Nevertheless, the public prosecutor tried to convict Meeter to four years imprisonment for his anti-authoritarian writings in his magazine ''De Tolk der Vrijheid'' ("The Spokesman of Freedom"); he fled to Belgium in February 1841, and eventually to Paris. From there, he requested and was granted amnesty by King

William II, and moved to Amsterdam. As an investigative journalist, he gathered all kinds of scandalous stories of William II's personal life, including his attempts to become king of France or Belgium, a conspiracy against his own father when he wanted to remarry, and finally the king's secret

homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexu ...

(considered perverse at the time). From 1840 to 1848, King William II frequently paid Meeter well to keep him silent. In 1857, Meeter published his memoires including his findings on royal affairs in English in London, ''Holland, Its Institutions, Its Press, Kings and Prisons'', and although he had been accused of being a liar ever since, documents from the Royal House Archive in 2004 revealed he had written the truth.

1848 Constitutional Reform

William II, who was more popular than his father, was also more willing to listen to his advisors. When the

Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

raged throughout Europe, with nationalists and liberals revolting and sometimes killing noblemen and royals in the process, William II was genuinely concerned for his safety and to lose his powers. Overnight, he changed from a conservative to a liberal, and agreed to the far-reaching

Constitutional Reform of 1848 on 11 October 1848. He accepted the introduction of full ministerial responsibility in the constitution, leading to a system of

parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the legisl ...

, with the House of Representatives directly elected by the voters within a system of single-winner

electoral district

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

s. Parliament was accorded the right to amend government law proposals and to hold investigative hearings. The States-Provincial, themselves elected by the voter, appointed by majorities for each province the members of the Senate from a select group of upper class citizens. A commission chaired by the liberal

Thorbecke was appointed to draft the new proposed constitution, which was finished on 19 June.

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

was enlarged (though still limited to

census suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to vo ...

), as was the bill of rights with the

freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of individuals to peaceably assemble and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their ideas. The right to free ...

, the

privacy of correspondence, freedom of ecclesiastical organisation and the

freedom of education

Freedom of education is the right for parents to have their children educated in accordance with their religious and other views, allowing groups to be able to educate children without being impeded by the nation state.

Freedom of education is a ...

.

In 1865, literary critic

Conrad Busken Huet

Conrad Busken Huet (28 December 1826, The Hague – 1 May 1886, Paris) was a Dutch pastor, journalist and literary critic.

Biography

Busken Huet, son of a Hague civil servant, attended Gymnasium Haganum and studied theology at Leiden Universi ...

famously commented: "One may complain or be proud about it, since 1848 the Netherlands has in fact been a democratic republic with a prince from the House of Orange as hereditary president."

1848–1890: Waning popularity

During the reign of

William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily ()

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg (1817–1890)

N ...

, the Dutch royal house's popularity waned, because William III had much trouble complying to the Constitutional Reform of 1848. He would rather exert the same power as his predecessors did. In 1866, after the Second Thorbecke cabinet, he formed a

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

cabinet. That cabinet was immediately voted out in the House of Representatives over the controversial royal appointment of

Pieter Mijer

Pieter Mijer (12 April 1881 – 10 March 1963) was a Dutch fencer. He competed in the individual épée event at the 1928 Summer Olympics

The 1928 Summer Olympics (), officially the Games of the IX Olympiad (), was an international mult ...

to

Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies

The governor-general of the Dutch East Indies (, ) represented Dutch rule in the Dutch East Indies between 1610 and Dutch recognition of the independence of Indonesia in 1949. Occupied by Japanese forces between 1942 and 1945, followed by the ...

. Instead of dismissing the cabinet, the king dissolved Parliament and organised new elections. All voters received a letter that urged them to vote conservative. Although the conservatives won, they did not attain a majority. Nevertheless, the cabinet did not step down.

Luxembourg Crisis

In 1867, William attempted to sell

Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

to

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, to both restore the European balance of power after the unexpected

Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

defeat in the

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

(1866), and alleviate his personal financial troubles. His decision greatly angered

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

(artificially agitated by Chancellor

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

), triggering the

Luxembourg Crisis

The Luxembourg Crisis (, ) was a diplomatic dispute and confrontation in 1867 between France and Prussia over the political status of Luxembourg.

The confrontation almost led to war between the two parties, but was peacefully resolved by the ...

. Prime Minister

Julius van Zuylen van Nijevelt

Julius Philip Jacob Adriaan, Count van Zuylen van Nijevelt (19 August 1819 – 1 July 1894) was a conservative Dutch politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1860 until 1861, and again from 1866 until 1868. During his second min ...

was able to prevent war between Prussia, the Netherlands and France by hosting a conference between the Great Powers, resulting in the

Treaty of London (1867)

The Treaty of London (), often called the Second Treaty of London after the 1839 Treaty, granted Luxembourg full independence and neutrality. It was signed on 11 May 1867 in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War and the Luxembourg Crisis. I ...

.

[Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. Luxemburgse kwestie.] The cabinet was heavily criticised by the liberals in Parliament, because it had threatened the Netherlands' neutrality whilst it should have stayed out of the matter, which was William's sole responsibility as the Grand Duke of Luxembourg. Parliament rejected the cabinet's foreign budget plans in November, leading the cabinet to offer its resignation to King William, but the furious William decided to dissolve Parliament instead. The newly elected House of Representatives maintained its opposition and again rejected the foreign budget, and approved the motion-Blussé van Oud-Alblas, condemning the needless dissolution of Parliament that had not served the country's interests in any way. This time the cabinet did step down, resulting in a parliamentary victory.

The Luxembourg Crisis confirmed the parliamentary system's working, and reduced the royal influence on politics:

1. Ministers have to have Parliament's trust;

2. Using the budget right, Parliament can force Ministers to step down;

3. The King can only exercise his right to appoint or fire Ministers if the majority of Parliament agrees;

4. The government can dissolve one or both Houses of Parliament in case of a conflict; however, if the new Parliament maintains its old standpoint, the government has to give in.

Dynastic troubles

The king's personal life was a frequent source of discontent not just amongst Dutch politicians and occasionally the populace, but also abroad (he became exceptionally notorious for his

exhibitionism

Exhibitionism is the act of exposing in a public or semi-public context one's intimate parts – for example, the breasts, genitals or buttocks. As used in psychology and psychiatry, it is substantially different. It refers to an uncontrolla ...

at

Lake Geneva

Lake Geneva is a deep lake on the north side of the Alps, shared between Switzerland and France. It is one of the List of largest lakes of Europe, largest lakes in Western Europe and the largest on the course of the Rhône. Sixty percent () ...

). His solitary decision, a few weeks after Queen

Sophie of Württemberg

Sophie of Württemberg (Sophie Friederike Matilda; 17 June 1818 – 3 June 1877) was Queen of the Netherlands as the first wife of King William III. Sophie separated from William in 1855 but continued to perform her duties as queen in public. ...

's death, to raise French opera singer

Émilie Ambre

Émilie Gabrielle Adèle Ambre (''née'' Ambroise; 1849 – April 1898) was a French opera singer who performed leading soprano roles in Europe and North America and later became a singing teacher. Born in French Algeria and trained at the Marseil ...

to 'comtesse d'Ambroise', granting her a luxurious residence in

Rijswijk

Rijswijk (), formerly known as Ryswick ( ) in English, is a town and municipality in the western Netherlands, in the province of South Holland. Its population was 59.642 in 2024, and it has an area of , of which is water.

The municipality also i ...

and expressing the intent to marry her without the cabinet's consent, led to political upheaval. His cousin

Prince Frederick demanded William to abdicate if he were to continue his plans. Eventually, William conceded and married 20-year-old

Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont

Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Adelheid Emma Wilhelmina Theresia; 2 August 1858 – 20 March 1934) was Queen of the Netherlands and Grand Duchess of Luxembourg as the wife of King-Grand Duke William III. An immensely popular member of the Dutc ...

instead. All of these actions gave the monarchy a bad name, so much so that throughout the 1880s there were serious calls to abolish the kingship.

Outspoken republican writers, journalists and their publishers were increasingly

Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

such as

Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis

Ferdinand Jacobus Domela Nieuwenhuis (31 December 1846 – 18 November 1919) was a Dutch socialist politician and later a social anarchist and anti-militarist. He was a Lutheran preacher who, after he lost his faith, started a political figh ...

(together with Sicco Roorda van Eysinga thought to be behind the 1887 anonymous libel against William III, titled ''

From the life of King Gorilla''). Unlike his father though, William III would not pay to keep his critics silent, but had them arrested and jailed or exiled. Seeing the rise of Socialism as a threat, several Liberals who had been traditionally republican, started the

Orangist countermovement.

The death of William III, who had no male successor (his sons

William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

and

Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

died in 1879 and 1884, respectively), was seized on by Luxembourg to declare its independence by breaking the personal union with the Netherlands on the grounds of the

lex Salica

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is debated. The written text is in Late L ...

; however, via the

Nassau-Weilburg

The House of Nassau-Weilburg, a branch of the House of Nassau, ruled a division of the County of Nassau, which was a state in what is now Germany, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, from 1344 to 1806.

On 17 July 1806, upon the dissolution of t ...

branch, the monarchy was continued there.

1890–1948: Recovery through reorientation

Succession secured, republic prevented

Queen-regent

Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont

Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Adelheid Emma Wilhelmina Theresia; 2 August 1858 – 20 March 1934) was Queen of the Netherlands and Grand Duchess of Luxembourg as the wife of King-Grand Duke William III. An immensely popular member of the Dutc ...

and Queen

Wilhelmina were able to recover much of the popular support lost under William III. They successfully changed the role of the royal family to symbolise the nation's unity, determination, and virtue.

In 1890, when Wilhelmina took office, rumours were spread by Socialist satirical magazine ''

De Roode Duivel'' ("The Red Devil") that William III was not her real father, but Emma's confidant . This would undermine the legitimacy of Wilhelmina's reign. Although no hard evidence exists for the allegations, and the consensus amongst historians is that they are false,

the rumours were stubborn, and still feature in

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

circulating in republican circles.

The author of the rumour, the later parliamentarian and senator

Louis Maximiliaan Hermans, was sentenced to six months imprisonment for

lèse-majesté

''Lèse-majesté'' or ''lese-majesty'' ( , ) is an offence or defamation against the dignity of a ruling head of state (traditionally a monarch but now more often a president) or of the state itself. The English name for this crime is a mod ...

in 1895 for a different article and cartoon in ''De Roode Duivel'', mocking the two queens.

There were considerably more concerns over the royal dynasty's future, when Wilhelmina's marriage with

Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (; ; 19 April 1876 – 3 July 1934) was Prince of the Netherlands from 7 February 1901 until his death in 1934 as the husband of Queen Wilhelmina. He remains the longest-serving Dutch consort.

Biography

Henry ...

(since 1901) repeatedly resulted in

miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion, is an end to pregnancy resulting in the loss and expulsion of an embryo or fetus from the womb before it can fetal viability, survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks ...

. Had the House of Orange died out, the throne would likely have passed to

Prince Heinrich XXXII Reuss of Köstritz

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The fema ...

, leading the Netherlands into an undesirable strong influence of the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

that would threaten Dutch independence. Not just Socialists, but now also

Anti-Revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution has occurred, in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "c ...

politicians including Prime Minister

Abraham Kuyper

Abraham Kuyper ( , ; 29 October 1837 – 8 November 1920) was the Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1901 and 1905, an influential neo-Calvinist pastor and a journalist. He established the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, which upo ...

and Liberals such as

Samuel van Houten advocated the restoration of the Republic in Parliament in case the marriage remained childless.

The birth of

Princess Juliana

Juliana (; Juliana Louise Emma Marie Wilhelmina; 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1948 until her abdication in 1980.

Juliana was the only child of Queen Wilhelmina and Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. She r ...

in 1909 put the question to rest.

Failed Socialist revolution

In

Red Week of November 1918, at the end of the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the attempt by activist

Pieter Jelles Troelstra

Pieter Jelles Troelstra (; 20 April 186012 May 1930) was a Dutch lawyer, journalist and politician active in the socialist workers' movement. He is most remembered for his fight for universal suffrage and his failed call for revolution at the en ...

to launch a

Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

after the examples elsewhere in Europe, failed. Instead, mass demonstrations in favour of the house of Orange were held, most notably on the Malieveld in

The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

on 18 November 1918, where Queen Wilhelmina, Prince Henry and the young Princess Juliana were cheered on by thousands of people waving orange flags. After Troelstra's mistake, most Socialists and Social Democrats gradually became monarchists during the 1920s and 1930s. At the birth of

Princess Irene on 5 August 1939,

SDAP party leader

Koos Vorrink declared: 'For the overwhelming majority of the Dutch people, the national unity and our national tradition are symbolised in the persons of the House of Orange-Nassau. That fact has now been accepted without reservation by the Social Democratic Workers' Party.' Three days later, several Socialist Ministers took office for the first time in the Netherlands.

1948–1980: Juliana period

Greet Hofmans affair

After the war, the royal house was plagued by affairs, most notably of faith healer

Greet Hofmans,

who managed to exert excessive control over the new Queen Juliana during 1948–1956. Hofmans divided the royal court into two camps before being forcibly removed after Juliana's husband,

Prince Bernhard

Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld (later Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands; 29 June 1911 – 1 December 2004) was Prince of the Netherlands from 6 September 1948 to 30 April 1980 as the husband of Queen Juliana. They had four daughters to ...

, leaked information on the power struggle to the German magazine ''

Der Spiegel

(, , stylized in all caps) is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg. With a weekly circulation of about 724,000 copies in 2022, it is one of the largest such publications in Europe. It was founded in 1947 by John Seymour Chaloner ...

''. But because the

Labour Party (PvdA, successor of the SDAP) and all other parties to its political right defended the monarchy in times of need, it was generally relatively safe from threats.

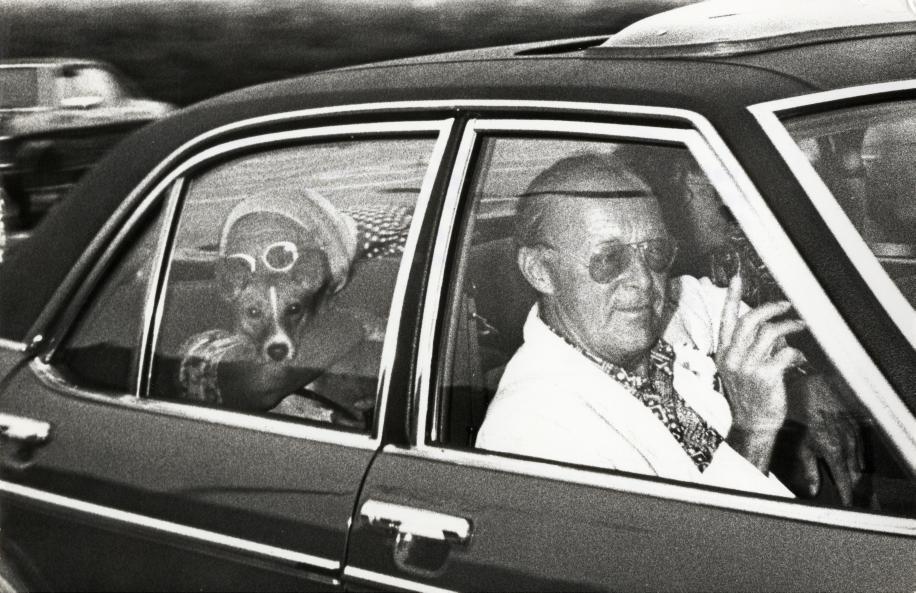

Beatrix–Claus marriage controversy

A brief peak in republicanism was caused by the announced engagement of

Crown Princess Beatrix to the German nobleman

Klaus von Amsberg on 10 June 1965. Although he had been member of the

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth ( , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth wing of the German Nazi Party. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. From 1936 until 1945, it was th ...

and briefly served in the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

, an official investigation concluded he had not committed any war crimes. The States-General granted him Dutch citizenship as Claus van Amsberg and approved of the

affiance. Nevertheless, the general public still resented the German occupation and oppression during the war, and a significant portion of the population opposed the marriage. On the occasion of the marriage, 109 years after Eillert Meeter had published his

anti-monarchist book in English, it was translated to Dutch

as ''Holland, kranten, kerkers en koningen''. Jewish organisations were offended that Amsterdam, where many Jews had been deported by the Nazis during the war, had been chosen as the wedding location, and the couple proposed

Baarn

Baarn () is a municipality and a town in the Netherlands, near Hilversum in the province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht.

The municipality of Baarn

The municipality of Baarn consists of the following towns: Baarn, Eembrugge, Lage Vuursche.

T ...

instead, but the government insisted on the capital.

The wedding day on 10 March 1966 saw violent protests, most notably by the anarchist-artist group

Provo. They included such memorable slogans as "Claus, 'raus!" (Claus, get out!). The wedding carriage's ride to and from the church in Amsterdam, where the Provo movement had been stirring up trouble for quite some time, was disrupted by riots with smoke bombs and fireworks; one smoke bomb was thrown at the wedding carriage by a group of Provos.

According to several newspapers, there were about a thousand rioters. Many of them chanted "Revolution!" and "Claus, 'raus!".

Crowd control barrier

Crowd control barriers (also referred to as crowd control barricades, with some versions called a French barrier or bike rack in the USA, and mills barriers in Hong Kong) are commonly used at many public events. They are frequently visible at ...

s and flagpoles were overthrown, bikes and mopeds thrown on the streets, and in the

Kalverstraat

The Kalverstraat (, ) is a busy shopping street of Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands. The street runs roughly North-South for about 750 meters, from Dam Square to Muntplein square.

The Kalverstraat is the most expensive shopping stree ...

a car was pushed over. For a time, it was thought that Beatrix would be the last monarch of the Netherlands. However, over time, Claus became accepted by the public.

Rise of republican parties

Until 1965, there were two small explicitly republican parties present in the House of Representatives, both left-wing: the

Pacifist Socialist Party

The Pacifist Socialist Party (, PSP) was a Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in the Netherlands. It is one of the predecessors of GroenLinks.

Party history

Before 1957

In 1955, a group of "politically homeless" activists ...

(PSP) and the

Communist Party of the Netherlands

The Communist Party of the Netherlands (, , CPN) was a communist party in the Netherlands. The party was founded in 1909 as the Social Democratic Party (Netherlands), Social Democratic Party (SDP) and merged with the Pacifist Socialist Party, the ...

(CPN). The engagement of Beatrix and Claus in June 1965 was seized upon by the PSP to stress its republican ideas more strongly, but the CPN harshly condemned the PSP's "principally republican" stance in an open letter, stating it considered "the threat of German revanchism" to be much more serious, and "everything that distracts from that, is repulsive." The engagement further inspired the foundation of a number of new parties, of which

Democrats 66

Democrats 66 (; D66) is a social liberal and progressive political party in the Netherlands, which is positioned on the centre to centre-left of the political spectrum. It is a member of the Liberal International (LI) and the Alliance of Li ...

would become the most successful.

On 22 December 1965,

the Republican Party Netherlands was founded by Arend Dunnewind and others in Rotterdam. Late February, Prime Minister

Jo Cals

Jozef Maria Laurens Theo "Jo" Cals (18 July 1914 – 30 December 1971) was a Dutch politician of the Catholic People's Party (KVP) and jurist who served as Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 14 April 1965 until 22 November 1966.

Cals studie ...

responded to a concerned RPN letter, assuring them that civil servants could sign up for party membership without being fired. Already in January 1966 a schism occurred and the two splinters registered separately at the Election Council (Kiesraad) in October, although they were already negotiating a reconciliation by then. Eventually, they decided not to participate in the

1967 general election.

Amsterdam

Liberal Party (VVD) council member

Hans Gruijters

Johannes Petrus Adrianus "Hans" Gruijters (; 30 June 1931 – 17 April 2005) was a Dutch politician and co-founder of the Democrats 66 (D66) party and journalist.

Biography

Hans Gruijters studied psychology and political and social sciences at ...

refused to attend the wedding reception ("I've got better things to do"), and later criticised the police actions against the protesters. The royalist VVD leadership reprimanded him, after which Gruijters discontentedly left the party. Together with

Hans van Mierlo, Erik Visser, Peter Baehr and others, he decided it was time for political innovation. In the political programme of the new party D'66, founded on 14 October 1966, the need for 'radical democratisation' is discussed, meaning 'the voter directly chooses his government' and 'standards of democratic expediency should determine the form of government—monarchy or republic.' However, the party explained that 'the reason to change the form of government is currently not present', although it did seek to end the king's role in the

cabinet formation

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

.

Within the PvdA, the innovative "

New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

" movement appeared, publishing the September 1966 manifesto ''Tien over Rood'' ("Ten About Red"), of which point 7 read: "It is desirable that the Netherlands become a republic as soon as queen Juliana's reign ends."

In October 1968, Klaas Hilberink founded the Republican Democrats Netherlands (RDN) in

Hoogeveen

Hoogeveen (; or '' 't Oveine'') is a municipality and a town in the Dutch province of Drenthe.

Population centres

Elim, Fluitenberg, Hoogeveen and Noordscheschut, which still have the canals which used to be throughout the town. Other v ...

, which shortly thereafter sought to merge with the Republican Party Netherlands. Hilberink reported in May 1970 that the RDN would partake in the

1971 general election, but this did not occur.

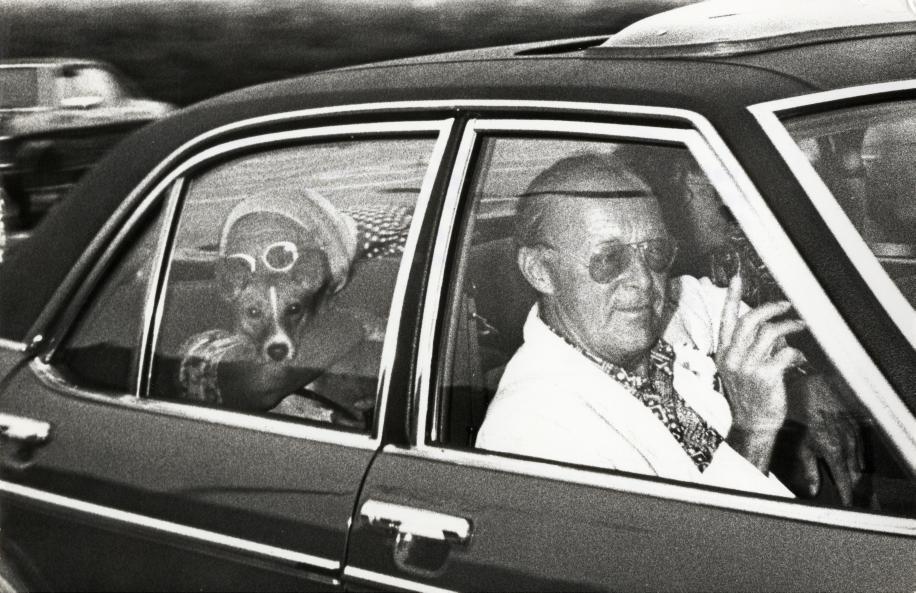

Lockheed scandal

In February 1976, the huge international

Lockheed bribery scandals

The Lockheed bribery scandals encompassed bribes and contributions made by officials of U.S. aerospace company Lockheed from the late 1950s to the 1970s in the process of negotiating the sale of aircraft. The scandal caused considerable pol ...

came out during public hearings by an investigative commission of the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. Key political and military people from

West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, the Netherlands and

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

had been bribed by

aircraft manufacturer

An aerospace manufacturer is a company or individual involved in the various aspects of designing, building, testing, selling, and maintaining aircraft, aircraft parts, missiles, rockets, or spacecraft. Aerospace is a high technology industry.

...

Lockheed Martin

The Lockheed Martin Corporation is an American Arms industry, defense and aerospace manufacturer with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta on March 15, 1995. It is headquartered in North ...

. Prince Bernhard, Inspector-General of the Armed Forces, appeared to be the Dutch person involved: an inquiry by a Commission of Three showed that he had accepted bribes to the value of 1.1 million guilders to try to persuade

Defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indust ...

to purchase Lockheed aircraft (specifically, the

Lockheed P-3 Orion

The Lockheed P-3 Orion is a four-engined, turboprop Anti-submarine warfare, anti-submarine and maritime patrol aircraft, maritime surveillance aircraft developed for the United States Navy and introduced in the 1960s. It is based on the Lockheed ...

).

On 20 August, the

Den Uyl cabinet

The Den Uyl cabinet was the cabinet of the Netherlands from 11 May 1973 until 19 December 1977. The cabinet was formed by the social democratic Labour Party (Netherlands), Labour Party (PvdA), the Christian democratic Catholic People's Party (KV ...

convened a crisis meeting, during which the Commission of Three's conclusions were unanimously confirmed, and earnest discussions ensued over which measures should be taken, and the consequences they would have for the queenship of Juliana, who would have threatened to abdicate if her husband were to be prosecuted. A minority of ministers, especially

Henk Vredeling (Defence, PvdA), found that prosecution was necessary;

Hans Gruijters

Johannes Petrus Adrianus "Hans" Gruijters (; 30 June 1931 – 17 April 2005) was a Dutch politician and co-founder of the Democrats 66 (D66) party and journalist.

Biography

Hans Gruijters studied psychology and political and social sciences at ...

(D66) even argued that the monarchy should be relinquished. However, a majority, including PvdA Ministers who were publicly critical about the monarchy, opined that the constitutional establishment could not be endangered and order should return as soon as possible, and feared to lose the vote of the still mostly royalist population during the next elections, in case prosecution were to be pursued.

Because Bernhard had, according to the government, damaged the state's interests through his actions, he was honourably discharged from his most prominent military functions by Royal Decree on 9 September 1976; he was also no longer allowed to wear his uniform at official events. According to

Cees Fasseur, this was "the last great scandal that shook the monarchy to its foundations." In 1977, the PvdA included in its

party platform

A political party platform (American English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British and often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principal goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, t ...

a statement (Part II, Article 4) that it sought to introduce an elected head of state, thereby henceforth officially striving to abolish the monarchy. The PvdA

overwhelmingly won the 1977 elections, but failed to form a new government. It is likely that Juliana would have already abdicated in 1978 if there would have been a second Den Uyl cabinet.

Change of throne 1980

Discussion on republic silenced

When Juliana announced her abdication on 31 January 1980, discussions on the form of government resurfaced in

purple

Purple is a color similar in appearance to violet light. In the RYB color model historically used in the arts, purple is a secondary color created by combining red and blue pigments. In the CMYK color model used in modern printing, purple is ...

political circles, in which republican members, mainly from the youth wings, clashed with the royalist party boards. A motion by the

Young Socialists, urging the PvdA to act on its goal of a republic as stated in the party platform, was rejected by the party council and thus not voted on. After a

Young Liberals (JOVD) commission declared that an elected head of state would be 'desirable', the JOVD main board declared that the JOVD "has no need for a different form of government" at all, "seeing the excellent manner in which queen Juliana has performed her work." VVD chair

Frits Korthals Altes

Frederik "Frits" Korthals Altes (15 May 1931 – 19 February 2025) was a Dutch politician of the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) and jurist. He was granted the honorary title of Minister of State on 26 October 2001.

Background

Ko ...

said he regretted the JOVD commission's statement, arguing monarchism is not a matter of political opinion, but of 'being Dutch' (implying republicans are not Dutch), and moreover claiming: 'The bond between the House of Orange and the Netherlands is above any discussion.' In response to clamour for discussion on the most desirable form of government from D'66 members, D'66 parliamentary leader

Jan Terlouw

Jan Cornelis Terlouw (15 November 1931 – 16 May 2025) was a Dutch politician, physicist and author. A member of the Democrats 66 (D66) party, he served as Deputy Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 1981 to 1982 under Prime Minister Dries ...

said discussion itself was good, but wondered "whether striving towards the theoretically best is also the most desirable", concluding that as long as everything works alright, there is no reason for change. The D'66 main board distanced itself from the anti-monarchist statements.

[

According to a February 1980 ''Algemeen Dagblad'' survey, only 67% of Dutch citizens had 'much confidence' in Beatrix as the new queen (higher amongst Christian Democrats (CDA) and Liberals, lower amongst D'66 and especially PvdA voters), but 89% remained in favour of the monarchy, 6% had no preference, and only 5% were convinced republicans (CDA and VVD: 3%; PvdA: 11%; D'66: 2%).]Roel van Duijn

Roeland Hugo Gerrit (Roel) van Duijn (born 20 January 1943) is a Dutch politician, political activist and writer. He was a founder of Provo and the Kabouterbeweging. He was alderman for the Political Party of Radicals and later wardcouncillo ...

said he expected tough actions against the monarchy during the investiture, even more fierce than in 1966 when he led them himself.

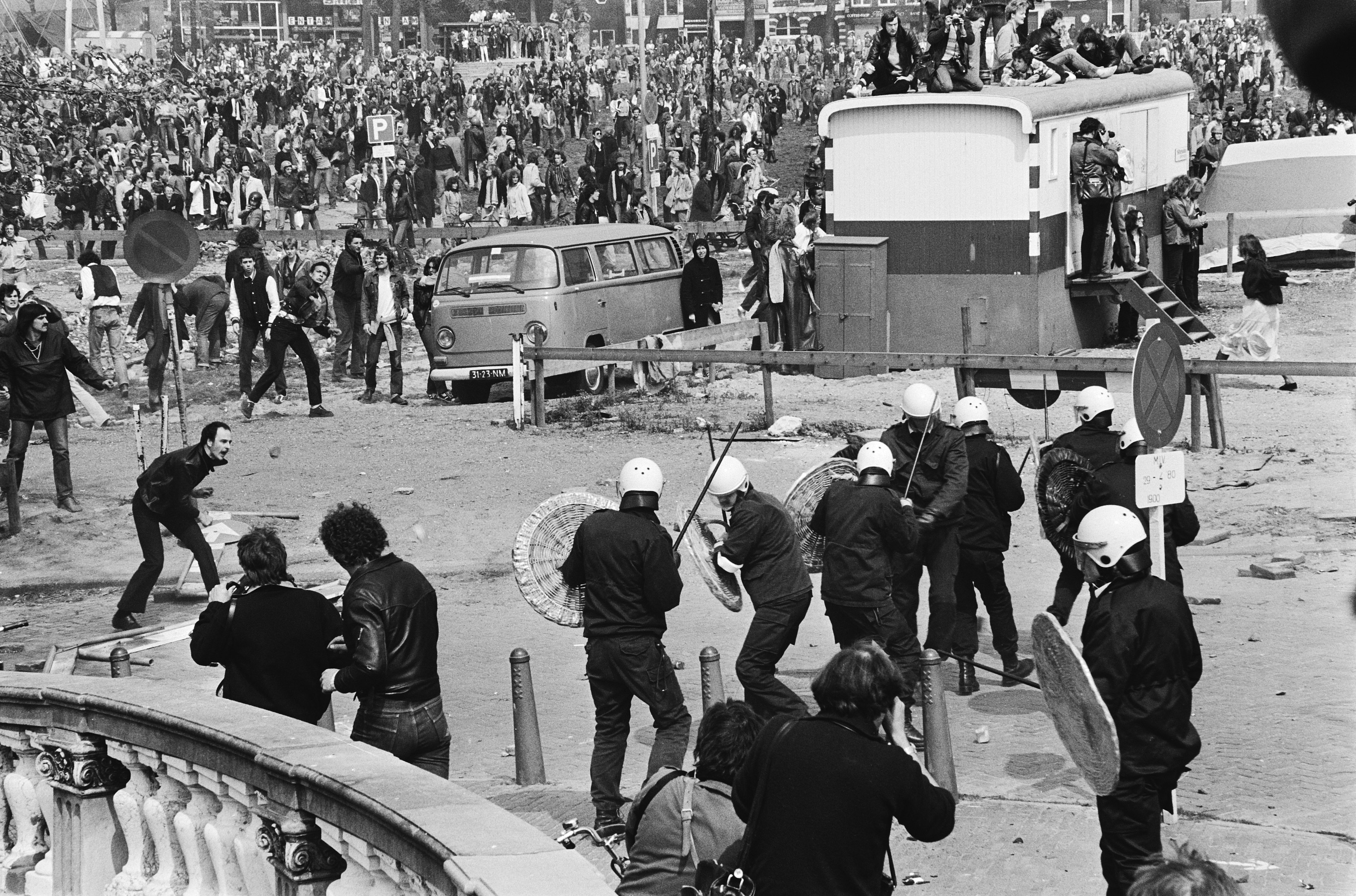

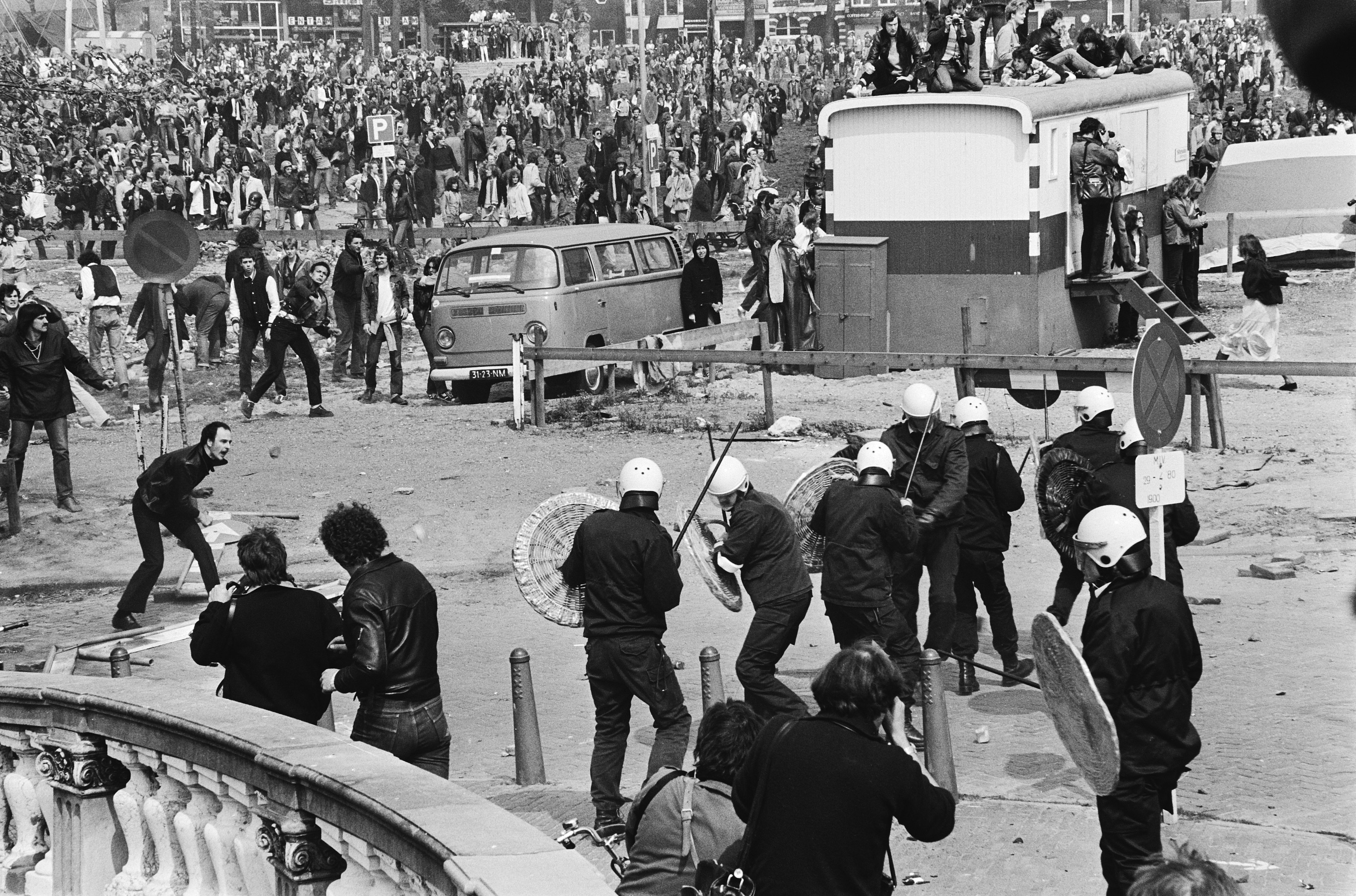

Coronation riots

On 30 April 1980, Queen Juliana abdicated in favour of her daughter

On 30 April 1980, Queen Juliana abdicated in favour of her daughter Beatrix

Beatrix is a Latin feminine given name, most likely derived from ''Viatrix'', a feminine form of the Late Latin name ''Viator'' which meant "voyager, traveller" and later influenced in spelling by association with the Latin word ''beatus'' or "ble ...

in Amsterdam. That day, squatters