''Dimetrodon'' ( or ; ) is an extinct

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of

sphenacodontid synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

that lived during the

Cisuralian

The Cisuralian, also known as the Early Permian, is the first series/epoch of the Permian. The Cisuralian was preceded by the Pennsylvanian and followed by the Guadalupian. The Cisuralian Epoch is named after the western slopes of the Ural Mou ...

(Early Permian)

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided b ...

of the

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

period, around 295–272 million years ago.

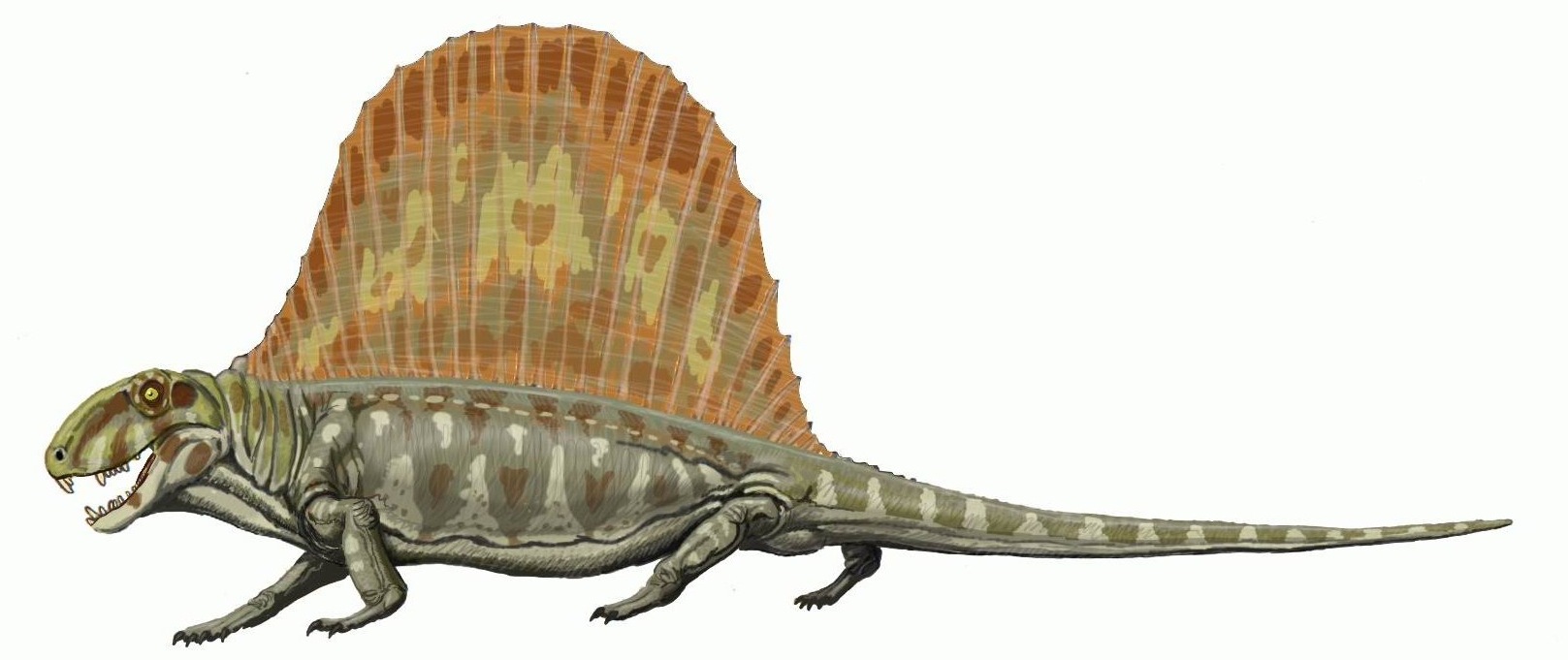

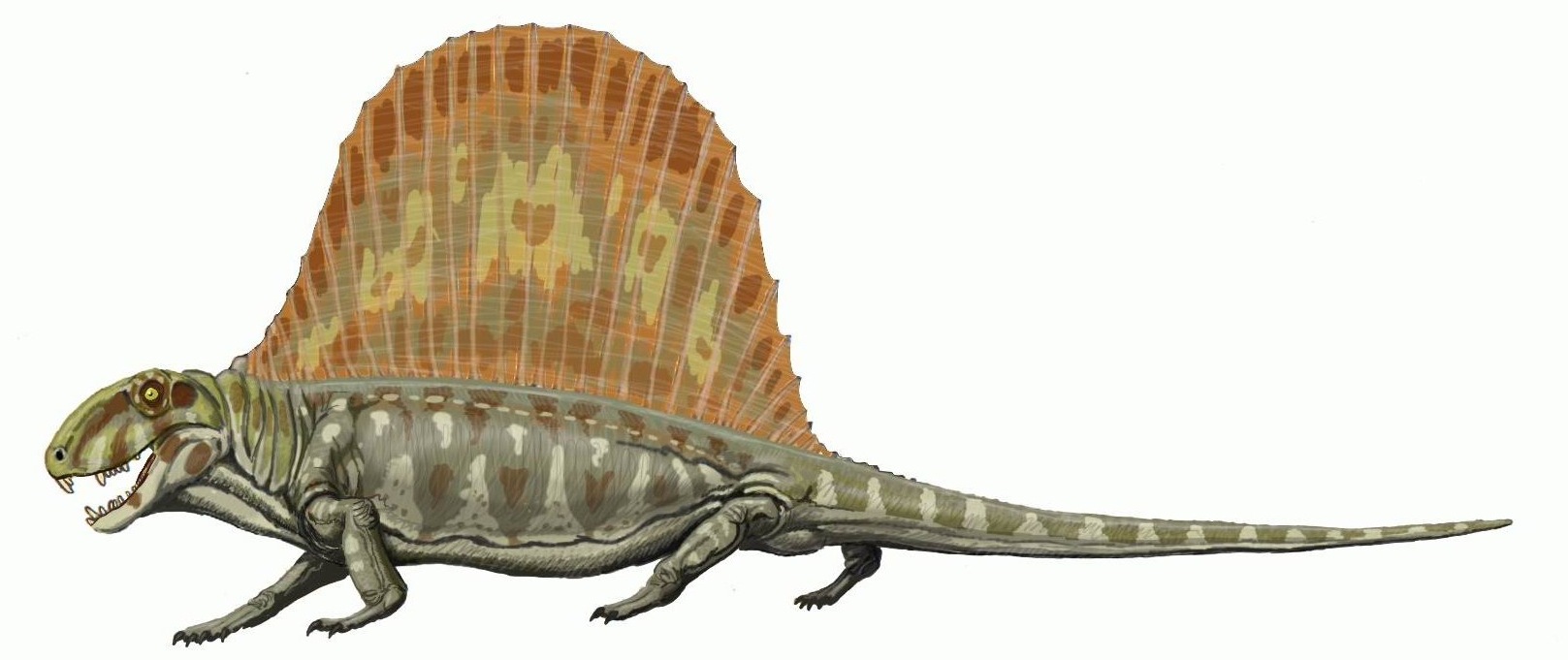

With most species measuring long and weighing , the most prominent feature of ''Dimetrodon'' is the large

neural spine sail on its back formed by elongated spines extending from the

vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

e. It was an obligate

quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion in which animals have four legs that are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four legs is said to be a quadruped (fr ...

(it could walk only on four legs) and had a tall, curved skull with large teeth of different sizes set along the jaws. Most fossils have been found in the

Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

, the majority of these coming from a geological deposit called the

Red Beds of Texas and Oklahoma. More recently, its fossils have also been found in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and over a dozen species have been named since the

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

was first erected in 1878.

''Dimetrodon'' is often mistaken for a

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

or portrayed as a contemporary of dinosaurs in

popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...

, but it became extinct by the middle

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

, some 40 million years before the advent of dinosaurs.

Although

reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

-like in appearance and physiology, ''Dimetrodon'' is much more closely related to

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, as it belongs to the closest

sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

to

therapsids, the latter of which contains the direct ancestor of mammals.

''Dimetrodon'' is traditionally assigned to the

paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

group "

pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

s", a term now considered obsolete and replaced by terms such as "primitive synapsids" or "basal synapsids"; another name "

mammal-like reptiles" is also used traditionally but incorrectly for non-mammalian synapsids

due to some of the features shared with modern mammals such as

tooth specialization and

endothermy, but that term is now also defunct. ''Dimetrodon''

skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

has a single opening (

temporal fenestra) behind each eye, a feature shared among all synapsids, unlike the skulls of reptiles and birds, both of which belonging to the clade

Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, which diverged from the synapsids at least since the

Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

.

''Dimetrodon'' was probably one of the

apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s of the Cisuralian ecosystems, feeding on fish and

tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, including reptiles and

amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s. Smaller ''Dimetrodon'' species may have had different

ecological roles. The sail of ''Dimetrodon'' may have been used to stabilize its spine or to heat and cool its body as a form of

thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

. Some recent studies argue that the sail would have been ineffective at removing heat from the body, due to large species being discovered with small sails and small species being discovered with large sails, essentially ruling out heat regulation as its main purpose. The sail was most likely used in

courtship display

A courtship display is a set of display behaviors in which an animal, usually a male, attempts to attract a mate; the mate exercises choice, so sexual selection acts on the display. These behaviors often include ritualized movement ("dances"), ...

, including threatening away rivals or showing off to potential mates.

Description

''Dimetrodon'' was a

quadrupedal, sail-backed synapsid that most likely had a semi-sprawling posture between that of a mammal and a lizard and also could walk in a more upright stance with its body and the majority or all of its tail off the ground. Most ''Dimetrodon'' species ranged in length from and are estimated to have weighed between .

The smallest known species ''D. teutonis'' was about long and weighed .

Skull

A single large opening on either side of the back of the skull links ''Dimetrodon'' to mammals and distinguishes it from most of the earliest sauropsids, which either lack openings or have two openings. Features such as ridges on the inside of the nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nas ...

and a ridge at the back of the lower jaw are thought to be part of an evolutionary progression from early four-limbed land-dwelling vertebrates to mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s.

The skull of ''Dimetrodon'' is tall and compressed laterally, or side-to-side. The eye sockets are positioned high and far back in the skull. Behind each eye socket on each side is a single hole called an infratemporal fenestra. An additional hole in the skull, the pineal foramen (or "third eye") along the midline between the parietal bones, can be seen when viewed from above. The back of the skull (the occiput

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the ...

) is oriented at a slight upward angle, a feature that it shares with all other early synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

s.premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

bone, is raised above the part of the jaw formed by the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

bone to form a maxillary "step". Within this step is a diastema, a gap in the tooth row. Its skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

was more heavily built than a dinosaur's skull.

Teeth

The size of the teeth varies greatly along the length of the jaws, lending ''Dimetrodon'' its name, which means "two measures of tooth" in reference to sets of small and large teeth. Many teeth are widest at their midsections and narrow closer to the jaws, giving them the appearance of a teardrop. Teardrop-shaped teeth are unique to ''Dimetrodon'' and other closely related sphenacodontids, which helps to distinguish them from other early synapsids.

Many teeth are widest at their midsections and narrow closer to the jaws, giving them the appearance of a teardrop. Teardrop-shaped teeth are unique to ''Dimetrodon'' and other closely related sphenacodontids, which helps to distinguish them from other early synapsids.synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

s, the teeth of most ''Dimetrodon'' species are serrated at their edges.[Abler, W.L. 2001. A kerf-and-drill model of tyrannosaur tooth serrations. p. 84-89. In: ''Mesozoic Vertebrate Life''. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.] The dinosaur '' Albertosaurus'' had similarly crack-like serrations, but, at the base of each serration was a round void, which would have functioned to distribute force over a larger surface area

The surface area (symbol ''A'') of a solid object is a measure of the total area that the surface of the object occupies. The mathematical definition of surface area in the presence of curved surfaces is considerably more involved than the d ...

and prevent the stresses of feeding from causing the crack to spread through the tooth. Unlike ''Albertosaurus'', ''Dimetrodon'' teeth lacked adaptations that would stop cracks from forming at their serrations.Secodontosaurus

''Secodontosaurus'' (meaning "cutting-tooth lizard") is an extinct genus of "pelycosaur" synapsids that lived from between about 285 to 272 million years ago during the Early Permian. Like the well known ''Dimetrodon'', ''Secodontosaurus'' is a c ...

''). The second-largest species, ''D. grandis'', has denticle serrations similar to those of sharks and theropod dinosaurs, making its teeth even more specialized for slicing through flesh. As ''Dimetrodons prey grew larger, the various species responded by growing to larger sizes and developing ever-sharper teeth. The thickness and mass of the teeth of ''Dimetrodon'' may also have been an adaptation for increasing dental longevity.

Nasal cavity

On the inner surface of the nasal section of the skull are ridges called nasoturbinals, which may have supported cartilage that increased the area of the olfactory epithelium

The olfactory epithelium is a specialized epithelium, epithelial tissue inside the nasal cavity that is involved in olfaction, smell. In humans, it measures

and lies on the roof of the nasal cavity about above and behind the nostrils. The olfact ...

, the layer of tissue that detects odors. These ridges are much smaller than those of later synapsids from the Late Permian and Triassic, whose large nasoturbinals are taken as evidence for warm-bloodedness because they may have supported mucous membranes that warmed and moistened incoming air. Thus, the nasal cavity of ''Dimetrodon'' is transitional between those of early land vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s and mammals.

Jaw joint and ear

Another transitional feature of ''Dimetrodon'' is a ridge in the back of the jaw called the reflected lamina, which is found on the articular bone, which connects to the quadrate bone of the skull to form the jaw joint. In later mammal ancestors, the articular and quadrate separated from the jaw joint, while the articular developed into the malleus

The ''malleus'', or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibra ...

bone of the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which transfer the vibrations ...

. The reflected lamina became part of a ring called the tympanic annulus that supports the ear drum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit changes in pressur ...

in all living mammals.

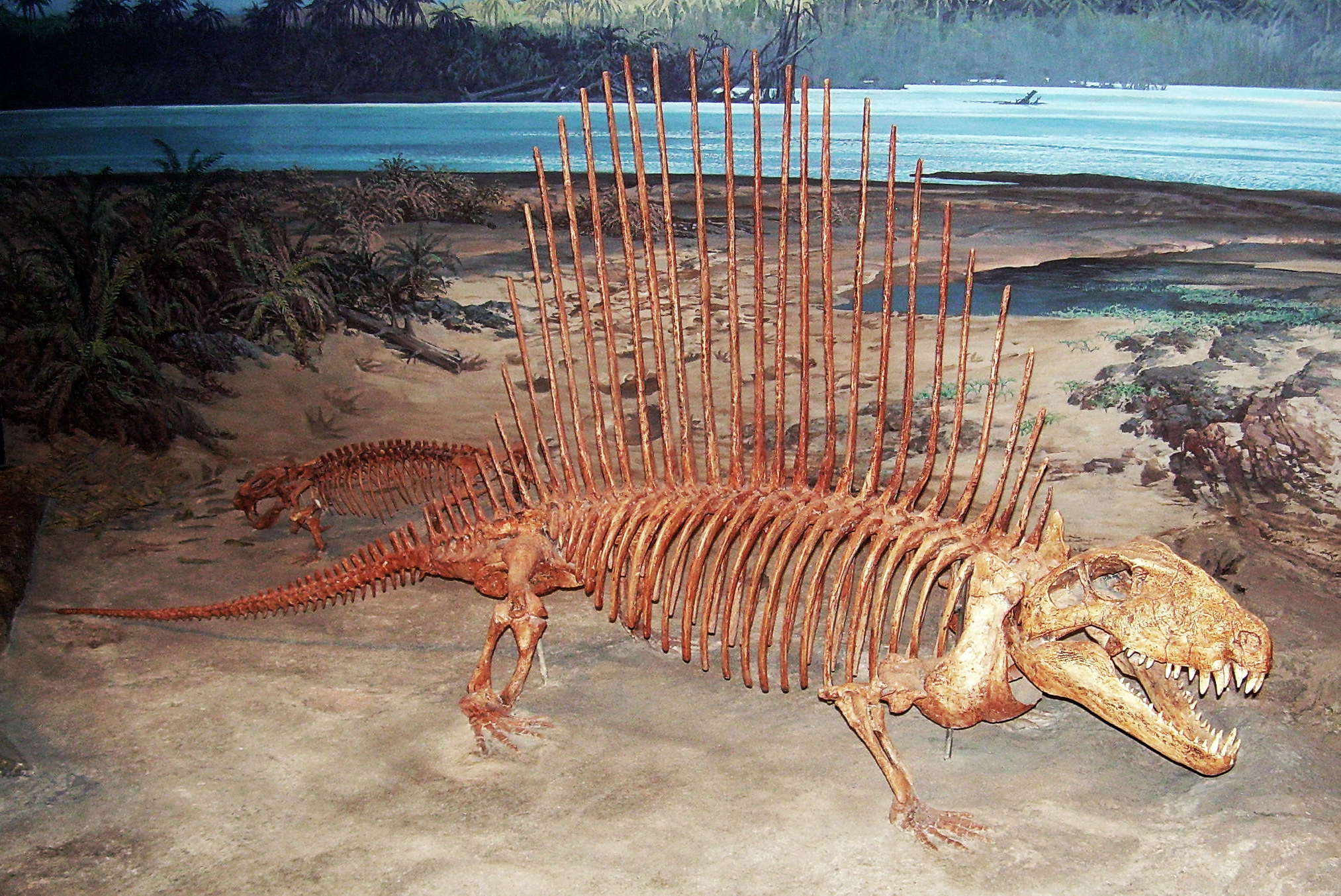

Tail

The tail of ''Dimetrodon'' makes up a large portion of its total body length and includes around 50 caudal vertebrae. Tails were missing or incomplete in the first described skeletons of ''Dimetrodon''. The only caudal vertebrae known were the 11 closest to the hip. Since these first few caudal vertebrae narrow rapidly as they progress farther from the hip, many paleontologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries thought that ''Dimetrodon'' had a very short tail. A largely complete tail of ''Dimetrodon'' was not described until 1927.

The tail of ''Dimetrodon'' makes up a large portion of its total body length and includes around 50 caudal vertebrae. Tails were missing or incomplete in the first described skeletons of ''Dimetrodon''. The only caudal vertebrae known were the 11 closest to the hip. Since these first few caudal vertebrae narrow rapidly as they progress farther from the hip, many paleontologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries thought that ''Dimetrodon'' had a very short tail. A largely complete tail of ''Dimetrodon'' was not described until 1927.

Sail

The sail of ''Dimetrodon'' is formed by elongated neural spines projecting from the vertebrae. Each spine varies in cross-sectional shape from its base to its tip in what is known as "dimetrodont" differentiation.

The sail of ''Dimetrodon'' is formed by elongated neural spines projecting from the vertebrae. Each spine varies in cross-sectional shape from its base to its tip in what is known as "dimetrodont" differentiation.periosteum

The periosteum is a membrane that covers the outer surface of all bones, except at the articular surfaces (i.e. the parts within a joint space) of long bones. (At the joints of long bones the bone's outer surface is lined with "articular cartila ...

, a layer of tissue surrounding the bone, is covered in small grooves that presumably supported the blood vessels that vascularized the sail.cortical bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, an ...

that grew over these breaks is highly vascularized, suggesting that soft tissue must have been present on the sail to supply the site with blood vessel

Blood vessels are the tubular structures of a circulatory system that transport blood throughout many Animal, animals’ bodies. Blood vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to most of the Tissue (biology), tissues of a Body (bi ...

s.lamellar bone

A bone is a Stiffness, rigid Organ (biology), organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red blood cell, red and white blood cells, store minerals, provi ...

makes up most of the neural spine's cross-sectional area, and contains lines of arrested growth that can be used to determine the age of each individual at death.

Skin

Scaly body impressions that likely were made by ''Dimetrodon teutonis'' were described in 2025 from the Early Permian Tambach Formation Bromacker site in Germany. Given the ichnogenus name ''Bromackerichnus'', the impressions left by animals resting on mud show a scaly epidermis pattern on the belly, and on the underside of the forelimbs and the tail, supporting the idea that early synapsids in general had a scaly body covering similar to reptiles. The fossilized bodies of the varanopid '' Ascendonanus'' with preserved soft tissues from the Early Permian of Germany also indicate some early synapsids may have had squamate-like scales. However, the taxonomic placement of varanopids has been debated between synapsids or closer to diapsid reptiles. Some synapsid groups later developed bare, glandular skin, as indicated by the fossils of the dinocephalian therapsid '' Estemmenosuchus'' from the middle Permian of Russia, which show its skin would have been smooth and well-provided with glands. ''Estemmenosuchus'' also had osteoderms embedded in its skin. Later synapsids evolved hair and whiskers that became characteristics of

Scaly body impressions that likely were made by ''Dimetrodon teutonis'' were described in 2025 from the Early Permian Tambach Formation Bromacker site in Germany. Given the ichnogenus name ''Bromackerichnus'', the impressions left by animals resting on mud show a scaly epidermis pattern on the belly, and on the underside of the forelimbs and the tail, supporting the idea that early synapsids in general had a scaly body covering similar to reptiles. The fossilized bodies of the varanopid '' Ascendonanus'' with preserved soft tissues from the Early Permian of Germany also indicate some early synapsids may have had squamate-like scales. However, the taxonomic placement of varanopids has been debated between synapsids or closer to diapsid reptiles. Some synapsid groups later developed bare, glandular skin, as indicated by the fossils of the dinocephalian therapsid '' Estemmenosuchus'' from the middle Permian of Russia, which show its skin would have been smooth and well-provided with glands. ''Estemmenosuchus'' also had osteoderms embedded in its skin. Later synapsids evolved hair and whiskers that became characteristics of mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

.

Classification history

Earliest discoveries

The earliest discovery of ''Dimetrodon'' fossils were of a maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

recovered in 1845 by a man named Donald McLeod, living in the British colony of Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island is an island Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. While it is the smallest province by land area and population, it is the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

.mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

of '' Bathygnathus borealis'', a large carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they ar ...

related to '' Thecodontosaurus,''International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

(ICZN) in 2015, which was approved in 2019.

First descriptions by Cope

Fossils now attributed to ''Dimetrodon'' were first studied by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

in the 1870s. Cope had obtained the fossils along with those of many other Permian tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s from several collectors who had been exploring a group of rocks in Texas called the Red Beds

Red beds (or redbeds) are sedimentary rocks, typically consisting of sandstone, siltstone, and shale, that are predominantly red in color due to the presence of ferric oxides. Frequently, these red-colored sedimentary strata locally contain t ...

. Among these collectors were Swiss naturalist Jacob Boll, Texas geologist W. F. Cummins, and amateur paleontologist Charles Hazelius Sternberg

Charles Hazelius Sternberg (June 15, 1850 – July 20, 1943) was an American fossil collector and paleontology, paleontologist. He was active in both fields from 1876 to 1928, and collected fossils for Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel C. Marsh, ...

.American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

or to the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

's Walker Museum (most of the Walker fossil collection is now housed in the Field Museum of Natural History).

Sternberg sent some of his own specimens to German paleontologist Ferdinand Broili at Munich University, although Broili was not as prolific as Cope in describing specimens. Cope's rival Othniel Charles Marsh also collected some bones of ''Dimetrodon'', which he sent to the Walker Museum.arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

habits, as in the existing genus ''Basilicus'', where a similar crest exists."

Early 20th century descriptions

In the first few decades of the 20th century, American paleontologists E. C. Case authored many studies on ''Dimetrodon'' and described several new species. He received funding from the Carnegie Institution for his study of many ''Dimetrodon'' specimens in the collections of the

In the first few decades of the 20th century, American paleontologists E. C. Case authored many studies on ''Dimetrodon'' and described several new species. He received funding from the Carnegie Institution for his study of many ''Dimetrodon'' specimens in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

and several other museums.

New specimens

In the decades following Romer and Price's monograph, many ''Dimetrodon'' specimens were described from localities outside Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

and Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

. The first was described from the Four Corners region of Utah in 1966

Species

Twenty

Twenty species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of ''Dimetrodon'' have been named since the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

was first described in 1878. Many have been synonymized with older named species, and some now belong to different genera.

Summary

''Dimetrodon limbatus''

''Dimetrodon limbatus'' was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877 as ''Clepsydrops limbatus''.

''Dimetrodon limbatus'' was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877 as ''Clepsydrops limbatus''.[ (The name ''Clepsydrops'' was first coined by Cope in 1875 for sphenacodontid remains from Vermilion County, Illinois, and was later employed for many sphenacontid specimens from Texas; many new species of sphenacodontids from Texas were assigned to either ''Clepsydrops'' or ''Dimetrodon'' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.) Based on a specimen from the Red Beds of Texas, it was the first known sail-backed synapsid. In 1940, paleontologists Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price reassigned ''C. limbatus'' to the genus ''Dimetrodon'', making ''D. limbatus'' the ]type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Dimetrodon''.Washington County, Ohio

Washington County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 59,711. Its county seat is Marietta. The county, the oldest in the state, is named for George Washington. Wa ...

, which correspond to a relatively large individual. These remains are slightly older than others assigned to ''D. limbatus'' from the west, although potential ''D. limbatus'' remains from New Mexico may be concurrent with it.

''Dimetrodon incisivus''

The first use of the name ''Dimetrodon'' came in 1878 when Cope named the species ''Dimetrodon incisivus'' along with ''Dimetrodon rectiformis'' and ''Dimetrodon gigas''.[

]

''Dimetrodon rectiformis''

''Dimetrodon rectiformis'' was named alongside ''Dimetrodon incisivus'' in Cope's 1878 paper, and was the only one of the three named species to preserve elongated neural spines.[ In 1907, paleontologist E. C. Case moved ''D. rectiformis'' into the species ''D. incisivus''.][ ''D. incisivus'' was later synonymous with the type species ''Dimetrodon limbatus'', making ''D. rectiformis'' a synonym of ''D. limbatus''.][

]

''Dimetrodon semiradicatus''

Described in 1881 on the basis of upper jaw bones, ''Dimetrodon semiradicatus'' was the last species named by Cope.[ ''D. incisivus and ''D. semiradicatus'' are now considered synonyms of ''D. limbatus''.][

]

''Dimetrodon dollovianus''

''Dimetrodon dollovianus'' was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1888 as ''Embolophorus dollovianus''. In 1903, E. C. Case published a lengthy description of ''E. dollovianus'', which he later referred to ''Dimetrodon''.

''Dimetrodon grandis''

Paleontologist E. C. Case named a new species of sail-backed synapsid, ''Theropleura grandis'', in 1907.[ In 1940, Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price reassigned ''Theropleura grandis'' to ''Dimetrodon'', erecting the species ''D. grandis''.][

]

''Dimetrodon gigas''

In his 1878 paper on fossils from Texas, Cope named ''Clepsydrops gigas'' along with the first named species of ''Dimetrodon'', ''D. limbatus'', ''D. incisivus'', and ''D. rectiformis''.[ Case reclassified ''C. gigas'' as a new species of ''Dimetrodon'' in 1907.][ Case also described a very well preserved skull of ''Dimetrodon'' in 1904, attributing it to the species ''Dimetrodon gigas''.]

''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes''

''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' was named by E. C. Case in 1907 and is still considered a valid species of ''Dimetrodon''.

''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' was named by E. C. Case in 1907 and is still considered a valid species of ''Dimetrodon''.[

]

''Dimetrodon macrospondylus''

''Dimetrodon macrospondylus'' was first described by Cope in 1884 as ''Clepsydrops macrospondylus''. In 1907, Case reclassified it as ''Dimetrodon macrospondylus''.[

]

''Dimetrodon platycentrus''

''Dimetrodon platycentrus'' was first described by Case in his 1907 monograph. It is now considered a synonym of ''Dimetrodon macrospondylus''.[

]

''Dimetrodon natalis''

Paleontologist Alfred Romer erected the species ''Dimetrodon natalis'' in 1936, previously described as ''Clepsydrops natalis''. ''D. natalis'' was the smallest known species of ''Dimetrodon'' at that time, and was found alongside remains of the larger-bodied ''D. limbatus''.

Paleontologist Alfred Romer erected the species ''Dimetrodon natalis'' in 1936, previously described as ''Clepsydrops natalis''. ''D. natalis'' was the smallest known species of ''Dimetrodon'' at that time, and was found alongside remains of the larger-bodied ''D. limbatus''.

''Dimetrodon booneorum''

''Dimetrodon booneorum'' was first described by Alfred Romer in 1937 on the basis of remains from Texas.[

]

''"Dimetrodon" kempae''

''Dimetrodon kempae'' was named by Romer in 1937, in the same paper as ''D. booneorum'', ''D. loomisi'', and ''D. milleri''.[ ''Dimetrodon kempae'' was named on the basis of a single humerus and a few vertebrae, and may therefore be a '']nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'' that cannot be distinguished as a unique species of ''Dimetrodon''.[ In 1940, Romer and Price raised the possibility that ''D. kempae'' may not fall within the genus ''Dimetrodon'', preferring to classify it as Sphenacodontidae '']incertae sedis

or is a term used for a taxonomy (biology), taxonomic group where its broader relationships are unknown or undefined. Alternatively, such groups are frequently referred to as "enigmatic taxa". In the system of open nomenclature, uncertainty ...

''.[

]

''Dimetrodon loomisi''

''Dimetrodon loomisi'' was first described by Alfred Romer in 1937 along with ''D. booneorum'', ''D. kempae'', and ''D. milleri''.

''Dimetrodon loomisi'' was first described by Alfred Romer in 1937 along with ''D. booneorum'', ''D. kempae'', and ''D. milleri''.[ Remains have been found in Texas and Oklahoma.

]

''Dimetrodon milleri''

''Dimetrodon milleri'' was described by Romer in 1937.

''Dimetrodon milleri'' was described by Romer in 1937.[ It is one of the smallest species of ''Dimetrodon'' in North America and may be closely related to ''D. occidentalis'', another small-bodied species.][ ''D. milleri'' is known from two skeletons, one nearly complete (MCZ 1365) and another less complete but larger (MCZ 1367). ''D. milleri'' is the oldest known species of ''Dimetrodon''.

Besides its small size, ''D. milleri'' differs from other species of ''Dimetrodon'' in that its neural spines are circular rather than figure-eight shaped in cross-section. Its vertebrae are also shorter in height relative to the rest of the skeleton than those of other ''Dimetrodon'' species. The skull is tall and the snout is short relative to the temporal region. A short vertebrae and tall skull are also seen in the species ''D. booneorum'', ''D. limbatus'' and ''D. grandis'', suggesting that ''D. milleri'' may be the first of an evolutionary progression between these species.

]

''Dimetrodon angelensis''

''Dimetrodon angelensis'' was named by paleontologist Everett C. Olson in 1962.

''Dimetrodon angelensis'' was named by paleontologist Everett C. Olson in 1962.

''Dimetrodon occidentalis''

''Dimetrodon occidentalis'' was named in 1977 from New Mexico.[ Its name means "western ''Dimetrodon''" because it is the only North American species of ''Dimetrodon'' known west of Texas and Oklahoma. It was named on the basis of a single skeleton belonging to a relatively small individual. The small size of ''D. occidentalis'' is similar to that of ''D. milleri'', suggesting a close relationship. ''Dimetrodon'' specimens found in Utah and Arizona probably also belong to ''D. occidentalis''.][

]

''Dimetrodon teutonis''

''Dimetrodon teutonis'' was named in 2001 from the Thuringian Forest

The Thuringian Forest (''Thüringer Wald'' in German language, German ) is a mountain range in the southern parts of the Germany, German state of Thuringia, running northwest to southeast. Skirting from its southerly source in foothills to a gorg ...

of Germany and was the first species of ''Dimetrodon'' to be described outside North America. It is also the smallest species of ''Dimetrodon''.[

]

Species assigned to different genera

''Dimetrodon cruciger''

In 1878, Cope published a paper called "The Theromorphous Reptilia" in which he described ''Dimetrodon cruciger''.Edaphosaurus

''Edaphosaurus'' (, meaning "pavement lizard" for dense clusters of its teeth) is a genus of extinct edaphosaurid synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous ...

'', a genus which Cope named in 1882 on the basis of skulls that evidently belonged to herbivorous animals given their blunt crushing teeth.

''Dimetrodon longiramus''

E. C. Case named the species ''Dimetrodon longiramus'' in 1907 on the basis of a scapula and elongated mandible from the Belle Plains Formation of Texas.[ In 1940, Romer and Price recognized that the ''D. longiramus'' material belonged to the same taxon as another specimen described by paleontologist ]Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and Paleontology, paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight Origin of birds#Origin of bird flight, cursorially (by ...

in 1916, which included a similarly elongated mandible and a long maxilla.[ Williston did not consider his specimen to belong to ''Dimetrodon'' but instead classified it as an ophiacodontid.]

Phylogenetic classification

''Dimetrodon'' is an early member of a group called synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

s, which include mammals and many of their extinct relatives, though it is not an ancestor of any mammal (which appeared millions of years later). It is often mistaken for a dinosaur in popular culture, despite having become extinct some 40 million years (Ma) before the first appearance of dinosaurs in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

period. As a synapsid, ''Dimetrodon'' is more closely related to mammals than to dinosaurs or any living reptile. By the early 1900s most paleontologists called ''Dimetrodon'' a reptile in accordance with Linnean taxonomy, which ranked Reptilia as a class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

and ''Dimetrodon'' as a genus within that class. Mammals were assigned to a separate class, and ''Dimetrodon'' was described as a "mammal-like reptile". Paleontologists theorized that mammals evolved from this group in (what they called) a reptile-to-mammal transition.

Phylogenetic taxonomy of Synapsida

Under phylogenetic systematics, the descendants of the

Under phylogenetic systematics, the descendants of the last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of ''Dimetrodon'' and all living reptiles would include all mammals because ''Dimetrodon'' is more closely related to mammals than to any living reptile. Thus, if it is desired to avoid the clade that contains both mammals and the living reptiles, then ''Dimetrodon'' must not be included in that clade—nor any other "mammal-like reptile". Descendants of the last common ancestor of mammals and reptiles (which appeared around 310 Ma in the Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

) are therefore split into two clades: Synapsida, which includes ''Dimetrodon'' and mammals, and Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, which includes living reptiles and all extinct reptiles more closely related to them than to mammals.Sphenacodontia

Sphenacodontia is a stem-based taxon, stem-based clade of derived synapsids. It was defined by Amson and Laurin (2011) as "the largest clade that includes ''Haptodus baylei'', ''Haptodus garnettensis'' and ''Sphenacodon ferox'', but not ''Edaphos ...

, which was first proposed as an early synapsid group in 1940 by paleontologists Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price, along with the groups Ophiacodontia and Edaphosauria.Therapsida

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including l ...

, which included the closest relatives to mammals. Romer and Price placed another group of early synapsids called varanopids within Sphenacodontia, considering them to be more primitive than other sphenacodonts like ''Dimetrodon''.phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

, but varanodontids are now considered more basal synapsids, falling outside clade Sphenacodontia. Within Sphenacodontia is the group Sphenacodontoidea, which in turn contains Sphenacodontidae and Therapsida

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including l ...

. Sphenacodontidae is the group containing ''Dimetrodon'' and several other sail-backed synapsids like '' Sphenacodon'' and ''Secodontosaurus

''Secodontosaurus'' (meaning "cutting-tooth lizard") is an extinct genus of "pelycosaur" synapsids that lived from between about 285 to 272 million years ago during the Early Permian. Like the well known ''Dimetrodon'', ''Secodontosaurus'' is a c ...

'', while Therapsida includes mammals and their mostly Permian and Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

relatives.

Below is the cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

Clade Synapsida, which follows this phylogeny of Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

as modified from the analysis of Benson (2012).

Paleobiology

Function of neural spines

Paleontologists have proposed many ways in which the sail could have functioned in life. Some of the first to think about its purpose suggested that the sail may have served as camouflage among reeds while ''Dimetrodon'' waited for prey, or as an actual boat-like sail to catch the wind while the animal was in the water.

Paleontologists have proposed many ways in which the sail could have functioned in life. Some of the first to think about its purpose suggested that the sail may have served as camouflage among reeds while ''Dimetrodon'' waited for prey, or as an actual boat-like sail to catch the wind while the animal was in the water.

Thermoregulation

In 1940, Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price proposed that the sail served a thermoregulatory function, allowing individuals to warm their bodies with the Sun. In the following years, many models were created to estimate the effectiveness of thermoregulation in ''Dimetrodon''. For example, in a 1973 article in the journal ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'', paleontologists C. D. Bramwell and P. B. Fellgett estimated that it took a individual about one and a half hours for its body temperature to rise from .endothermic

An endothermic process is a chemical or physical process that absorbs heat from its surroundings. In terms of thermodynamics, it is a thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, ...

, controlling their body temperature internally through heightened metabolism. Turner and Tracy noted that early therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids closely related to mammals, had long limbs which can release heat in a manner similar to that of the sail of ''Dimetrodon''. The homeothermy that developed in animals like ''Dimetrodon'' may have carried over to therapsids through a modification of body shape, which would eventually develop into the warm-bloodedness of mammals. Recent studies on the sail of ''Dimetrodon'' and other sphenacodontids support Haack's 1986 contention that the sail was poorly adapted to releasing heat and maintaining a stable body temperature. The presence of sails in small-bodied species of ''Dimetrodon'' such as ''D. milleri'' and ''D. teutonis'' does not fit the idea that the sail's purpose was thermoregulation because smaller sails are less able to transfer heat and because small bodies can absorb and release heat easily on their own. Moreover, close relatives of ''Dimetrodon'' such as '' Sphenacodon'' have very low crests that would have been useless as thermoregulatory devices.

Recent studies on the sail of ''Dimetrodon'' and other sphenacodontids support Haack's 1986 contention that the sail was poorly adapted to releasing heat and maintaining a stable body temperature. The presence of sails in small-bodied species of ''Dimetrodon'' such as ''D. milleri'' and ''D. teutonis'' does not fit the idea that the sail's purpose was thermoregulation because smaller sails are less able to transfer heat and because small bodies can absorb and release heat easily on their own. Moreover, close relatives of ''Dimetrodon'' such as '' Sphenacodon'' have very low crests that would have been useless as thermoregulatory devices.amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

-wide study that found tachymetabolic endothermy to have been widespread throughout, and likely plesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, an ...

to both synapsids

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

and sauropsids. For ''Dimetrodon'' the evidence was the endothermy-indicative size of the foramina through which blood was delivered to their long bones and the high blood pressure that would have been necessary to provide blood to the tops of the well-vascularised spines supporting the sail.

Larger bodied specimens of ''Dimetrodon'' have larger sails relative to their size, an example of positive allometry. Positive allometry may benefit thermoregulation because it means that, as individuals get larger, surface area increases faster than mass. Larger-bodied animals generate a great deal of heat through metabolism, and the amount of heat that must be dissipated from the body surface is significantly greater than what must be dissipated by smaller-bodied animals. Effective heat dissipation can be predicted across many different animals with a single relationship between mass and surface area. However, a 2010 study of allometry in ''Dimetrodon'' found a different relationship between its sail and body mass: the actual scaling exponent of the sail was much larger than the exponent expected in an animal adapted to heat dissipation. The researchers concluded that the sail of ''Dimetrodon'' grew at a much faster rate than was necessary for thermoregulation, and suggested that sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ...

was the primary reason for its evolution.

Sexual selection

The allometric exponent for sail height is similar in magnitude to the scaling of interspecific antler length to shoulder height in cervids. Furthermore, as Bakker (1970) observed in the context of ''Dimetrodon'', many lizard species raise a dorsal ridge of skin during threat and courtship displays, and positively allometric, sexually dimorphic frills and dewlaps are present in extant lizards (Echelle et al. 1978; Christian et al. 1995). There is also evidence of sexual dimorphism both in the robustness of the skeleton and in the relative height of the spines of ''D. limbatus'' (Romer and Price 1940).

Sexual dimorphism

''Dimetrodon'' may have been sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, meaning that males and females had slightly different body sizes. Some specimens of ''Dimetrodon'' have been hypothesized as males because they have thicker bones, larger sails, longer skulls, and more pronounced maxillary "steps" than others. Based on these differences, the mounted skeletons in the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

(AMNH 4636) and the Field Museum of Natural History may be males and the skeletons in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science ( MCZ 1347) and the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History may be females.[

]

Paleoecology

Fossils of ''Dimetrodon'' are known from the United States (Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Ohio), Canada (

Fossils of ''Dimetrodon'' are known from the United States (Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Ohio), Canada (Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island is an island Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. While it is the smallest province by land area and population, it is the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

) and Germany, areas that were part of the supercontinent Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

during the Early Permian. Within the United States, almost all material attributed to ''Dimetrodon'' has come from three geological groups in north-central Texas and south-central Oklahoma: the Clear Fork Group, the Wichita Group, and the Pease River Group.tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, or four-limbed vertebrates. In addition to ''Dimetrodon'', the most common tetrapods in the Red Beds and throughout Early Permian deposits in the southwestern United States, are the amphibians '' Archeria'', '' Diplocaulus'', '' Eryops'', and '' Trimerorhachis'', the reptiliomorph '' Seymouria'', the reptile '' Captorhinus'', and the synapsids '' Ophiacodon'' and ''Edaphosaurus

''Edaphosaurus'' (, meaning "pavement lizard" for dense clusters of its teeth) is a genus of extinct edaphosaurid synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous ...

''. These tetrapods made up a group of animals that paleontologist Everett C. Olson called the "Permo-Carboniferous chronofauna", a fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

that dominated the continental Euramerican ecosystem for several million years.

Food web

Olson made many inferences on the paleoecology of the Texas Red beds and the role of ''Dimetrodon'' within its ecosystem. He proposed several main types of ecosystems in which the earliest tetrapods lived. ''Dimetrodon'' belonged to the most primitive ecosystem, which developed from aquatic food webs. In it, aquatic plants were the

Olson made many inferences on the paleoecology of the Texas Red beds and the role of ''Dimetrodon'' within its ecosystem. He proposed several main types of ecosystems in which the earliest tetrapods lived. ''Dimetrodon'' belonged to the most primitive ecosystem, which developed from aquatic food webs. In it, aquatic plants were the primary producer

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

s and were largely fed upon by fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

and aquatic invertebrates. Most land vertebrates fed on these aquatic primary consumers. ''Dimetrodon'' was probably the top predator of the Red Beds ecosystem, feeding on a variety of organisms such as the shark ''Xenacanthus

''Xenacanthus'' (from Ancient Greek wikt:ξένος, ξένος, xénos, 'foreign, alien' + wikt:ἄκανθος, ἄκανθος, akanthos, 'spine') is an extinct genus of Xenacanthida, xenacanth cartilaginous fish. It lived in freshwater environ ...

'', the aquatic amphibians '' Trimerorhachis'' and '' Diplocaulus'', and the terrestrial tetrapods '' Seymouria'' and '' Trematops''. Insects are known from the Early Permian Red Beds and were probably involved to some degree in the same food web as ''Dimetrodon'', feeding small reptiles like '' Captorhinus''. The Red Beds assemblage also included some of the first large land-living herbivores like ''Edaphosaurus

''Edaphosaurus'' (, meaning "pavement lizard" for dense clusters of its teeth) is a genus of extinct edaphosaurid synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous ...

'' and '' Diadectes''. Feeding primarily on terrestrial plants, these herbivores did not derive their energy from aquatic food webs. According to Olson, the best modern analogue for the ecosystem ''Dimetrodon'' inhabited is the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of flooded grasslands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orlando with the K ...

.tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s is unusual in that there are few large-bodied synapsids serving the role of top predators. ''D. teutonis'' is estimated to have been only in length, too small to prey on the large diadectid herbivores that are abundant in the Bromacker assemblage. It more likely ate small vertebrates and insects. Only three fossils can be attributed to large predators, and they are thought to have been either large varanopids or small sphenacodonts, both of which could potentially prey on ''D. teutonis''. In contrast to the lowland deltaic Red Beds of Texas, the Bromacker deposits are thought to have represented an upland environment with no aquatic species. It is possible that large-bodied carnivores were not part of the Bromacker assemblage because they were dependent on large aquatic amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s for food.

See also

*

*

* Olson's Extinction

Olson's Extinction was a mass extinction that occurred in the late Cisuralian or early Guadalupian epoch of the Permian period, predating the much larger Permian–Triassic extinction event.

The event is named after American paleontologist E ...

— an extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

that wiped out most of the pelycosaurian synapsids, including ''Dimetrodon''

References

External links

''Dimetrodon''

Palaeos Palaeos.com is a web site on biology, paleontology, phylogeny and geology and which covers the history of Earth. The site is well respected and has been used as a reference by professional paleontologists such as Michael J. Benton, the professor of ...

page on ''Dimetrodon''

Introduction to the Pelycosaurs

University of California Museum of Paleontology

The University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) is a paleontology museum located on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley.

The museum is within the Valley Life Sciences Building (VLSB), designed by George W. Kelham ...

webpage on early synapsids, including ''Dimetrodon''

*

{{Authority control

Permian Germany

Sphenacodontidae

Cisuralian synapsids of Europe

Cisuralian synapsids of North America

Prehistoric synapsid genera

Transitional fossils

Taxa named by Edward Drinker Cope

Fossil taxa described in 1878

Cisuralian genus first appearances

Cisuralian genus extinctions

Apex predators

''Dimetrodon'' was a quadrupedal, sail-backed synapsid that most likely had a semi-sprawling posture between that of a mammal and a lizard and also could walk in a more upright stance with its body and the majority or all of its tail off the ground. Most ''Dimetrodon'' species ranged in length from and are estimated to have weighed between . The smallest known species ''D. teutonis'' was about long and weighed . The larger species of ''Dimetrodon'' were among the largest predators of the Early Permian, although the closely related '' Tappenosaurus'', known from skeletal fragments in slightly younger rocks, may have been even larger at an estimated long. Although some ''Dimetrodon'' species could grow very large, many juvenile specimens are known.

''Dimetrodon'' was a quadrupedal, sail-backed synapsid that most likely had a semi-sprawling posture between that of a mammal and a lizard and also could walk in a more upright stance with its body and the majority or all of its tail off the ground. Most ''Dimetrodon'' species ranged in length from and are estimated to have weighed between . The smallest known species ''D. teutonis'' was about long and weighed . The larger species of ''Dimetrodon'' were among the largest predators of the Early Permian, although the closely related '' Tappenosaurus'', known from skeletal fragments in slightly younger rocks, may have been even larger at an estimated long. Although some ''Dimetrodon'' species could grow very large, many juvenile specimens are known.

The tail of ''Dimetrodon'' makes up a large portion of its total body length and includes around 50 caudal vertebrae. Tails were missing or incomplete in the first described skeletons of ''Dimetrodon''. The only caudal vertebrae known were the 11 closest to the hip. Since these first few caudal vertebrae narrow rapidly as they progress farther from the hip, many paleontologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries thought that ''Dimetrodon'' had a very short tail. A largely complete tail of ''Dimetrodon'' was not described until 1927.

The tail of ''Dimetrodon'' makes up a large portion of its total body length and includes around 50 caudal vertebrae. Tails were missing or incomplete in the first described skeletons of ''Dimetrodon''. The only caudal vertebrae known were the 11 closest to the hip. Since these first few caudal vertebrae narrow rapidly as they progress farther from the hip, many paleontologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries thought that ''Dimetrodon'' had a very short tail. A largely complete tail of ''Dimetrodon'' was not described until 1927.

The sail of ''Dimetrodon'' is formed by elongated neural spines projecting from the vertebrae. Each spine varies in cross-sectional shape from its base to its tip in what is known as "dimetrodont" differentiation. Near the vertebra body, the spine cross section is laterally compressed into a rectangular shape and, closer to the tip, it takes on a figure-eight shape as a groove runs along either side of the spine. The figure-eight shape is thought to reinforce the spine, preventing bending and fractures. A cross-section of the spine of one specimen of ''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' is rectangular in shape but preserves figure-eight shaped rings close to its center, indicating that the shape of spines may change as individuals age. The microscopic anatomy of each spine varies from base to tip, indicating where it was embedded in the muscles of the back and where it was exposed as part of a sail. The lower or proximal portion of the spine has a rough surface that would have served as an anchoring point for the epaxial muscles of the back and also has a network of connective tissues called Sharpey's fibers that indicate it was embedded within the body. Higher up on the distal (outer) portion of the spine, the bone surface is smoother. The

The sail of ''Dimetrodon'' is formed by elongated neural spines projecting from the vertebrae. Each spine varies in cross-sectional shape from its base to its tip in what is known as "dimetrodont" differentiation. Near the vertebra body, the spine cross section is laterally compressed into a rectangular shape and, closer to the tip, it takes on a figure-eight shape as a groove runs along either side of the spine. The figure-eight shape is thought to reinforce the spine, preventing bending and fractures. A cross-section of the spine of one specimen of ''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' is rectangular in shape but preserves figure-eight shaped rings close to its center, indicating that the shape of spines may change as individuals age. The microscopic anatomy of each spine varies from base to tip, indicating where it was embedded in the muscles of the back and where it was exposed as part of a sail. The lower or proximal portion of the spine has a rough surface that would have served as an anchoring point for the epaxial muscles of the back and also has a network of connective tissues called Sharpey's fibers that indicate it was embedded within the body. Higher up on the distal (outer) portion of the spine, the bone surface is smoother. The  Scaly body impressions that likely were made by ''Dimetrodon teutonis'' were described in 2025 from the Early Permian Tambach Formation Bromacker site in Germany. Given the ichnogenus name ''Bromackerichnus'', the impressions left by animals resting on mud show a scaly epidermis pattern on the belly, and on the underside of the forelimbs and the tail, supporting the idea that early synapsids in general had a scaly body covering similar to reptiles. The fossilized bodies of the varanopid '' Ascendonanus'' with preserved soft tissues from the Early Permian of Germany also indicate some early synapsids may have had squamate-like scales. However, the taxonomic placement of varanopids has been debated between synapsids or closer to diapsid reptiles. Some synapsid groups later developed bare, glandular skin, as indicated by the fossils of the dinocephalian therapsid '' Estemmenosuchus'' from the middle Permian of Russia, which show its skin would have been smooth and well-provided with glands. ''Estemmenosuchus'' also had osteoderms embedded in its skin. Later synapsids evolved hair and whiskers that became characteristics of

Scaly body impressions that likely were made by ''Dimetrodon teutonis'' were described in 2025 from the Early Permian Tambach Formation Bromacker site in Germany. Given the ichnogenus name ''Bromackerichnus'', the impressions left by animals resting on mud show a scaly epidermis pattern on the belly, and on the underside of the forelimbs and the tail, supporting the idea that early synapsids in general had a scaly body covering similar to reptiles. The fossilized bodies of the varanopid '' Ascendonanus'' with preserved soft tissues from the Early Permian of Germany also indicate some early synapsids may have had squamate-like scales. However, the taxonomic placement of varanopids has been debated between synapsids or closer to diapsid reptiles. Some synapsid groups later developed bare, glandular skin, as indicated by the fossils of the dinocephalian therapsid '' Estemmenosuchus'' from the middle Permian of Russia, which show its skin would have been smooth and well-provided with glands. ''Estemmenosuchus'' also had osteoderms embedded in its skin. Later synapsids evolved hair and whiskers that became characteristics of  In the first few decades of the 20th century, American paleontologists E. C. Case authored many studies on ''Dimetrodon'' and described several new species. He received funding from the Carnegie Institution for his study of many ''Dimetrodon'' specimens in the collections of the

In the first few decades of the 20th century, American paleontologists E. C. Case authored many studies on ''Dimetrodon'' and described several new species. He received funding from the Carnegie Institution for his study of many ''Dimetrodon'' specimens in the collections of the  Twenty

Twenty  ''Dimetrodon limbatus'' was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877 as ''Clepsydrops limbatus''. (The name ''Clepsydrops'' was first coined by Cope in 1875 for sphenacodontid remains from Vermilion County, Illinois, and was later employed for many sphenacontid specimens from Texas; many new species of sphenacodontids from Texas were assigned to either ''Clepsydrops'' or ''Dimetrodon'' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.) Based on a specimen from the Red Beds of Texas, it was the first known sail-backed synapsid. In 1940, paleontologists Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price reassigned ''C. limbatus'' to the genus ''Dimetrodon'', making ''D. limbatus'' the

''Dimetrodon limbatus'' was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877 as ''Clepsydrops limbatus''. (The name ''Clepsydrops'' was first coined by Cope in 1875 for sphenacodontid remains from Vermilion County, Illinois, and was later employed for many sphenacontid specimens from Texas; many new species of sphenacodontids from Texas were assigned to either ''Clepsydrops'' or ''Dimetrodon'' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.) Based on a specimen from the Red Beds of Texas, it was the first known sail-backed synapsid. In 1940, paleontologists Alfred Romer and Llewellyn Ivor Price reassigned ''C. limbatus'' to the genus ''Dimetrodon'', making ''D. limbatus'' the  ''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' was named by E. C. Case in 1907 and is still considered a valid species of ''Dimetrodon''.

''Dimetrodon giganhomogenes'' was named by E. C. Case in 1907 and is still considered a valid species of ''Dimetrodon''.

Paleontologist Alfred Romer erected the species ''Dimetrodon natalis'' in 1936, previously described as ''Clepsydrops natalis''. ''D. natalis'' was the smallest known species of ''Dimetrodon'' at that time, and was found alongside remains of the larger-bodied ''D. limbatus''.

Paleontologist Alfred Romer erected the species ''Dimetrodon natalis'' in 1936, previously described as ''Clepsydrops natalis''. ''D. natalis'' was the smallest known species of ''Dimetrodon'' at that time, and was found alongside remains of the larger-bodied ''D. limbatus''.

''Dimetrodon loomisi'' was first described by Alfred Romer in 1937 along with ''D. booneorum'', ''D. kempae'', and ''D. milleri''. Remains have been found in Texas and Oklahoma.

''Dimetrodon loomisi'' was first described by Alfred Romer in 1937 along with ''D. booneorum'', ''D. kempae'', and ''D. milleri''. Remains have been found in Texas and Oklahoma.

''Dimetrodon milleri'' was described by Romer in 1937. It is one of the smallest species of ''Dimetrodon'' in North America and may be closely related to ''D. occidentalis'', another small-bodied species. ''D. milleri'' is known from two skeletons, one nearly complete (MCZ 1365) and another less complete but larger (MCZ 1367). ''D. milleri'' is the oldest known species of ''Dimetrodon''.

Besides its small size, ''D. milleri'' differs from other species of ''Dimetrodon'' in that its neural spines are circular rather than figure-eight shaped in cross-section. Its vertebrae are also shorter in height relative to the rest of the skeleton than those of other ''Dimetrodon'' species. The skull is tall and the snout is short relative to the temporal region. A short vertebrae and tall skull are also seen in the species ''D. booneorum'', ''D. limbatus'' and ''D. grandis'', suggesting that ''D. milleri'' may be the first of an evolutionary progression between these species.

''Dimetrodon milleri'' was described by Romer in 1937. It is one of the smallest species of ''Dimetrodon'' in North America and may be closely related to ''D. occidentalis'', another small-bodied species. ''D. milleri'' is known from two skeletons, one nearly complete (MCZ 1365) and another less complete but larger (MCZ 1367). ''D. milleri'' is the oldest known species of ''Dimetrodon''.

Besides its small size, ''D. milleri'' differs from other species of ''Dimetrodon'' in that its neural spines are circular rather than figure-eight shaped in cross-section. Its vertebrae are also shorter in height relative to the rest of the skeleton than those of other ''Dimetrodon'' species. The skull is tall and the snout is short relative to the temporal region. A short vertebrae and tall skull are also seen in the species ''D. booneorum'', ''D. limbatus'' and ''D. grandis'', suggesting that ''D. milleri'' may be the first of an evolutionary progression between these species.

''Dimetrodon angelensis'' was named by paleontologist Everett C. Olson in 1962. Specimens of the species were reported from the San Angelo Formation of Texas. It is also the largest species of ''Dimetrodon''.

''Dimetrodon angelensis'' was named by paleontologist Everett C. Olson in 1962. Specimens of the species were reported from the San Angelo Formation of Texas. It is also the largest species of ''Dimetrodon''.

Paleontologists have proposed many ways in which the sail could have functioned in life. Some of the first to think about its purpose suggested that the sail may have served as camouflage among reeds while ''Dimetrodon'' waited for prey, or as an actual boat-like sail to catch the wind while the animal was in the water. Another is that the long neural spines could have stabilized the trunk by restricting up-and-down movement, which would allow for a more efficient side-to-side movement while walking.

Paleontologists have proposed many ways in which the sail could have functioned in life. Some of the first to think about its purpose suggested that the sail may have served as camouflage among reeds while ''Dimetrodon'' waited for prey, or as an actual boat-like sail to catch the wind while the animal was in the water. Another is that the long neural spines could have stabilized the trunk by restricting up-and-down movement, which would allow for a more efficient side-to-side movement while walking.

Recent studies on the sail of ''Dimetrodon'' and other sphenacodontids support Haack's 1986 contention that the sail was poorly adapted to releasing heat and maintaining a stable body temperature. The presence of sails in small-bodied species of ''Dimetrodon'' such as ''D. milleri'' and ''D. teutonis'' does not fit the idea that the sail's purpose was thermoregulation because smaller sails are less able to transfer heat and because small bodies can absorb and release heat easily on their own. Moreover, close relatives of ''Dimetrodon'' such as '' Sphenacodon'' have very low crests that would have been useless as thermoregulatory devices. The large sail of ''Dimetrodon'' is thought to have developed gradually from these smaller crests, meaning that over most of the sail's evolutionary history, thermoregulation could not have served an important function.

Although the function of its sail remains uncertain, ''Dimetrodon'' and other Sphenacodontids were likely to have been whole-body endotherms, characterised by a high energy metabolism ( tachymetabolism) and probably a capacity for maintaining a high and stable body temperature. This conclusion was part of an