designer babies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A designer baby is an

Embryos for PGD are obtained from IVF procedures in which the oocyte is artificially fertilised by sperm. Oocytes from the woman are harvested following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), which involves fertility treatments to induce production of multiple oocytes. After harvesting the oocytes, they are fertilised ''

Embryos for PGD are obtained from IVF procedures in which the oocyte is artificially fertilised by sperm. Oocytes from the woman are harvested following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), which involves fertility treatments to induce production of multiple oocytes. After harvesting the oocytes, they are fertilised ''

The CRISPR/Cas9 system (

The CRISPR/Cas9 system ( Upon system delivery to a cell, Cas9 and the gRNA bind, forming a

Upon system delivery to a cell, Cas9 and the gRNA bind, forming a

As of 2023, He has resumed research in genetic medicine after his three year imprisonment by the Chinese government for his "illegal medical practices." He has since shifted his focus to the treatment of genetic diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), after his release. Despite backlashes from the Lulu and Nana case, he has been appointed as the inaugural director of the Genetic Medicine Institute at Wuchang University of Technology in Wuhan in September 2023. He's application to work in Hong Kong was initially granted a visa, however, it was later revoked due to ongoing ethical and legal challenges surrounding his career.

As of 2023, He has resumed research in genetic medicine after his three year imprisonment by the Chinese government for his "illegal medical practices." He has since shifted his focus to the treatment of genetic diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), after his release. Despite backlashes from the Lulu and Nana case, he has been appointed as the inaugural director of the Genetic Medicine Institute at Wuchang University of Technology in Wuhan in September 2023. He's application to work in Hong Kong was initially granted a visa, however, it was later revoked due to ongoing ethical and legal challenges surrounding his career.

embryo

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sp ...

or fetus

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic development, embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Pren ...

whose genetic makeup has been intentionally selected or altered, often to exclude a particular gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

or to remove genes associated with disease, to achieve desired traits. This process usually involves preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD or PIGD) is the genetic profiling of embryos prior to implantation (as a form of embryo profiling), and sometimes even of oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered in a similar fashion to prenatal ...

(PGD), which analyzes multiple human embryos

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

to identify genes associated with specific disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

s and characteristics, then selecting embryos that have the desired genetic makeup. While screening for single genes is commonly practiced, advancements in polygenic screening are becoming more prominent, though only a few companies currently offer it. This technique uses an algorithm to aggregate the estimated effects of numerous genetic variants tied to an individual's risk for a particular condition or trait. Other methods of altering a baby's genetic information involve directly editing the genome before birth, using technologies such as CRISPR

CRISPR (; acronym of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. Each sequence within an individual prokaryotic CRISPR is d ...

. A controversial example of this can be seen in the 2018 case involving Chinese twins Lulu and Nana, which had their genomes edited to resist HIV infection, sparking widespread criticism and legal debates.

This highlights the implications of germline engineering, which involves introducing the desired genetic material into the embryo or parental germ cells

A germ cell is any cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually. In many animals, the germ cells originate in the primitive streak and migrate via the gut of an embryo to the developing gonads. There, they undergo ...

. This process is typically prohibited by law, however, regulations vary globally. Editing embryos in this manner can result in genetic changes that are passed down to future generations, raising significant controversy and ethical concerns. While some scientists advocate for its use in treating genetic diseases, others warn that it could lead to misuse for non-medical purposes, such as cosmetic enhancements and modification of human traits.

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD or PIGD) is a procedure in which embryos are screened prior to implantation. The technique is used alongside ''in vitro'' fertilisation (IVF) to obtain embryos for evaluation of the genome – alternatively, oocytes can be screened prior tofertilisation

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a zygote and initiate its development into a new individual organism or of ...

. The technique was first used in 1989.

PGD is used primarily to select embryos for implantation in the case of possible genetic defects, allowing identification of mutated

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA replication, DNA or viral rep ...

or disease-related alleles

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), but they can also have insertions and deletions ...

and selection against them. It is especially useful in embryos from parents where one or both carry a heritable disease. PGD can also be used to select for embryos of a certain sex, most commonly when a disease is more strongly associated with one sex than the other (as is the case for X-linked disorders which are more common in males, such as haemophilia

Haemophilia (British English), or hemophilia (American English) (), is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a long ...

). Infants born with traits selected following PGD are sometimes considered to be designer babies.

One application of PGD is the selection of ' saviour siblings', children who are born to provide a transplant (of an organ or group of cells) to a sibling with a usually life-threatening disease. Saviour siblings are conceived through IVF and then screened using PGD to analyze genetic similarity to the child needing a transplant, to reduce the risk of rejection.

Process

Embryos for PGD are obtained from IVF procedures in which the oocyte is artificially fertilised by sperm. Oocytes from the woman are harvested following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), which involves fertility treatments to induce production of multiple oocytes. After harvesting the oocytes, they are fertilised ''

Embryos for PGD are obtained from IVF procedures in which the oocyte is artificially fertilised by sperm. Oocytes from the woman are harvested following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), which involves fertility treatments to induce production of multiple oocytes. After harvesting the oocytes, they are fertilised ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

'', either during incubation with multiple sperm cells in culture, or ''via'' intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI ) is an in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure in which a single sperm cell is injected directly into the cytoplasm of an egg. This technique is used in order to prepare the gametes for the obtention of embr ...

(ICSI), where sperm is directly injected into the oocyte. The resulting embryos are usually cultured for 3–6 days, allowing them to reach the blastomere

In biology, a blastomere is a type of cell produced by cell division (cleavage) of the zygote after fertilization; blastomeres are an essential part of blastula formation, and blastocyst formation in mammals.

Human blastomere characteristics

In ...

or blastocyst

The blastocyst is a structure formed in the early embryonic development of mammals. It possesses an inner cell mass (ICM) also known as the ''embryoblast'' which subsequently forms the embryo, and an outer layer of trophoblast cells called the ...

stage.

Once embryos reach the desired stage of development, cells are biopsied and genetically screened. The screening procedure varies based on the nature of the disorder being investigated.

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) is a process in which DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

sequences are amplified to produce many more copies of the same segment, allowing screening of large samples and identification of specific genes. The process is often used when screening for monogenic disorders, such as cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

.

Another screening technique, fluorescent ''in situ'' hybridisation (FISH) uses fluorescent probes which specifically bind to highly complementary sequences

: ''For complementary sequences in biology, see complementarity (molecular biology). For integer sequences with complementary sets of members see Lambek–Moser theorem.''

In applied mathematics, complementary sequences (CS) are pairs of sequences ...

on chromosomes

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most importa ...

, which can then be identified using fluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. A fluorescence micro ...

. FISH is often used when screening for chromosomal abnormalities such as aneuploidy

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, for example a human somatic (biology), somatic cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more plo ...

, making it a useful tool when screening for disorders such as Down syndrome.

Following the screening, embryos with the desired trait (or lacking an undesired trait such as a mutation) are transferred into the mother's uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

, then allowed to develop naturally.

Regulation

PGD regulation is determined by individual countries' governments, with some prohibiting its use entirely, including inAustria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

.

In many countries, PGD is permitted under very stringent conditions for medical use only, as is the case in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Whilst PGD in Italy and Switzerland is only permitted under certain circumstances, there is no clear set of specifications under which PGD can be carried out, and selection of embryos based on sex is not permitted. In France and the UK, regulations are much more detailed, with dedicated agencies setting out framework for PGD. Selection based on sex is permitted under certain circumstances, and genetic disorders for which PGD is permitted are detailed by the countries' respective agencies.

In contrast, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

federal law does not regulate PGD, with no dedicated agencies specifying regulatory framework by which healthcare professionals must abide. Elective sex selection is permitted, accounting for around 9% of all PGD cases in the U.S., as is selection for desired conditions such as deafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is writte ...

or dwarfism

Dwarfism is a condition of people and animals marked by unusually small size or short stature. In humans, it is sometimes defined as an adult height of less than , regardless of sex; the average adult height among people with dwarfism is . '' ...

.

Polygenic risk score (PRS) screening

In the 2020s, companies such as Orchid Bioscience began offering polygenic risk scores (PRS) analysis for embryos during IVF. PRS estimates the likelihood of complex traits, such as height and intelligence, or diseases like diabetes, by summarizing data from thousands of genetic markers. However, many geneticists and bioethicists argue that PRS predictions lack clinical validity and promote eugenic practices that can prioritize socially desirable characteristics. They believe this approach risks reinforcing societal biases that may not be realistic and limits the autonomy and identity of the child as it restricts their life within a framework of genetic predictions. A 2021 study found that PRS explains only 5-10% of variance in educational attainment, highlighting its limited predictive ability.Pre-implantation Genetic Testing

Based on the specific analysis conducted: PGT-M (Preimplantation Genetic Testing for monogenic diseases) is a technique used during IVF to detect hereditary diseases caused bymutations

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitosi ...

or alterations of the DNA sequence with a single gene.

PGT-A (Preimplantation Genetic Testing for aneuploidy): It is used to diagnose numerical abnormalities ( aneuploidies).

Human germline engineering

Human germline engineering is a process in which the human genome is edited within agerm cell

A germ cell is any cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually. In many animals, the germ cells originate in the primitive streak and migrate via the gut of an embryo to the developing gonads. There, they unde ...

, such as a sperm cell or oocyte (causing heritable changes), or in the zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

or embryo following fertilization. Germline engineering results in changes in the genome being incorporated into every cell in the body of the offspring (or of the individual following embryonic germline engineering). This process differs from somatic cell

In cellular biology, a somatic cell (), or vegetal cell, is any biological cell forming the body of a multicellular organism other than a gamete, germ cell, gametocyte or undifferentiated stem cell. Somatic cells compose the body of an organism ...

engineering, which does not result in heritable changes. Most human germline editing is performed on individual cells and non-viable embryos, which are destroyed at a very early stage of development. In November 2018, however, a Chinese scientist, He Jiankui

He Jiankui ( zh, s=贺建奎, p=Hè Jiànkuí ; born 1984) is a Chinese biophysicist known for his controversial first use of genome editing in humans.

He served as associate professor of biology at the Southern University of Science and ...

, announced that he had created the first human germline genetically edited babies.

Genetic engineering relies on a knowledge of human genetic information, made possible by research such as the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

, which identified the position and function of all the genes in the human genome. As of 2019, high-throughput sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

methods allow genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing or just genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a single time. This entails sequencing all of an organism's ...

to be conducted very rapidly, making the technology widely available to researchers.

Germline modification is typically accomplished through techniques which incorporate a new gene into the genome of the embryo or germ cell in a specific location. This can be achieved by introducing the desired DNA directly to the cell for it to be incorporated, or by replacing a gene with one of interest. These techniques can also be used to remove or disrupt unwanted genes, such as ones containing mutated sequences.

Whilst germline engineering has mostly been performed in mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

and other animals, research on human cells ''in vitro'' is becoming more common. Most commonly used in human cells are germline gene therapy and the engineered nuclease system CRISPR/Cas9.

Germline gene modification

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is Health technology, medical technology that aims to produce a therapeutic effect through the manipulation of gene expression or through altering the biological properties of living cells.

The first attempt at modifying human DNA ...

is the delivery of a nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

(usually DNA or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

) into a cell as a pharmaceutical agent to treat disease. Most commonly it is carried out using a vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

, which transports the nucleic acid (usually DNA encoding a therapeutic gene) into the target cell. A vector can transduce a desired copy of a gene into a specific location to be expressed as required. Alternatively, a transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

can be inserted to deliberately disrupt an unwanted or mutated gene, preventing transcription and translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

of the faulty gene products to avoid a disease phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

.

Gene therapy in patients is typically carried out on somatic cells in order to treat conditions such as some leukaemias and vascular diseases

Vascular disease is a class of diseases of the vessels of the circulatory system in the human body, body, including blood vessels – the arteries and veins, and the lymphatic vessels. Vascular disease is a subgroup of cardiovascular disease. Diso ...

.

Human germline gene therapy in contrast is restricted to ''in vitro'' experiments in some countries, whilst others prohibited it entirely, including Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Switzerland.

Whilst the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Service ...

in the US does not currently allow '' in utero'' germline gene transfer clinical trials, ''in vitro'' trials are permitted. The NIH guidelines state that further studies are required regarding the safety of gene transfer protocols before ''in utero'' research is considered, requiring current studies to provide demonstrable efficacy of the techniques in the laboratory. Research of this sort is currently using non-viable embryos to investigate the efficacy of germline gene therapy in treatment of disorders such as inherited mitochondrial diseases

Mitochondrial disease is a group of disorders caused by mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are the organelles that generate energy for the cell and are found in every cell of the human body except red blood cells. They convert the energy of ...

.

Gene transfer to cells is usually by vector delivery. Vectors are typically divided into two classes – viral and non-viral.

Viral vectors

Viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almo ...

infect cells by transducing their genetic material into a host's cell, using the host's cellular machinery to generate viral proteins needed for replication and proliferation. By modifying viruses and loading them with the therapeutic DNA or RNA of interest, it is possible to use these as a vector to provide delivery of the desired gene into the cell.

Retroviruses

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. After invading a host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

are some of the most commonly used viral vectors, as they not only introduce their genetic material into the host cell, but also copy it into the host's genome. In the context of gene therapy, this allows permanent integration of the gene of interest into the patient's own DNA, providing longer lasting effects.

Viral vectors work efficiently and are mostly safe but present with some complications, contributing to the stringency of regulation on gene therapy. Despite partial inactivation of viral vectors in gene therapy research, they can still be immunogenic

Immunogenicity is the ability of a foreign substance, such as an antigen, to provoke an immune response in the body of a human or other animal. It may be wanted or unwanted:

* Wanted immunogenicity typically relates to vaccines, where the injectio ...

and elicit an immune response

An immune response is a physiological reaction which occurs within an organism in the context of inflammation for the purpose of defending against exogenous factors. These include a wide variety of different toxins, viruses, intra- and extracellula ...

. This can impede viral delivery of the gene of interest, as well as cause complications for the patient themselves when used clinically, especially in those who already have a serious genetic illness. Another difficulty is the possibility that some viruses will randomly integrate their nucleic acids into the genome, which can interrupt gene function and generate new mutations.

This is a significant concern when considering germline gene therapy, due to the potential to generate new mutations in the embryo or offspring.

Non-viral vectors

Non-viral methods of nucleic acidtransfection

Transfection is the process of deliberately introducing naked or purified nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells. It may also refer to other methods and cell types, although other terms are often preferred: " transformation" is typically used to des ...

involved injecting a naked DNA plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

into cell for incorporation into the genome. This method used to be relatively ineffective with low frequency of integration, however, efficiency has since greatly improved, using methods to enhance the delivery of the gene of interest into cells. Furthermore, non-viral vectors are simple to produce on a large scale and are not highly immunogenic.

Some non-viral methods are detailed below:

*Electroporation

Electroporation, also known as electropermeabilization, is a microbiological and biotechnological technique in which an electric field is applied to cells to briefly increase the permeability of the cell membrane. The application of a high-vo ...

is a technique in which high voltage pulses are used to carry DNA into the target cell across the membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

. The method is believed to function due to the formation of pores across the membrane, but although these are temporary, electroporation results in a high rate of cell death

Cell death is the event of a biological cell ceasing to carry out its functions. This may be the result of the natural process of old cells dying and being replaced by new ones, as in programmed cell death, or may result from factors such as di ...

which has limited its use. An improved version of this technology, electron-avalanche transfection, has since been developed, which involves shorter (microsecond) high voltage pulses which result in more effective DNA integration and less cellular damage.

*The gene gun

In genetic engineering, a gene gun or biolistic particle delivery system is a device used to deliver exogenous DNA (transgenes), RNA, or protein to cells. By coating particles of a heavy metal with a gene of interest and firing these micro-projec ...

is a physical method of DNA transfection, where a DNA plasmid is loaded onto a particle of heavy metal (usually gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

) and loaded onto the 'gun'. The device generates a force to penetrate the cell membrane, allowing the DNA to enter whilst retaining the metal particle.

*Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small fragments of nucleic aci ...

are used as chemical vectors for gene therapy, often used to disrupt mutated DNA sequences to prevent their expression. Disruption in this way can be achieved by introduction of small RNA molecules, called siRNA

Small interfering RNA (siRNA), sometimes known as short interfering RNA or silencing RNA, is a class of double-stranded non-coding RNA molecules, typically 20–24 base pairs in length, similar to microRNA (miRNA), and operating within the RN ...

, which signal cellular machinery to cleave the unwanted mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

sequences to prevent their transcription. Another method utilises double-stranded oligonucleotides, which bind transcription factors

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fun ...

required for transcription of the target gene. By competitively binding these transcription factors, the oligonucleotides can prevent the gene's expression.

ZFNs

Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) are enzymes generated by fusing a zinc finger DNA-binding domain to a DNA-cleavage domain. Zinc finger recognizes between 9 and 18 bases of sequence. Thus by mixing those modules, it becomes easier to target any sequence researchers wish to alter ideally within complex genomes. A ZFN is amacromolecular

A macromolecule is a "molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass." Polymers are physi ...

complex formed by monomers in which each subunit contains a zinc domain and a FokI endonuclease domain. The FokI domains must dimerize for activities, thus narrowing target area by ensuring that two close DNA-binding events occurs.

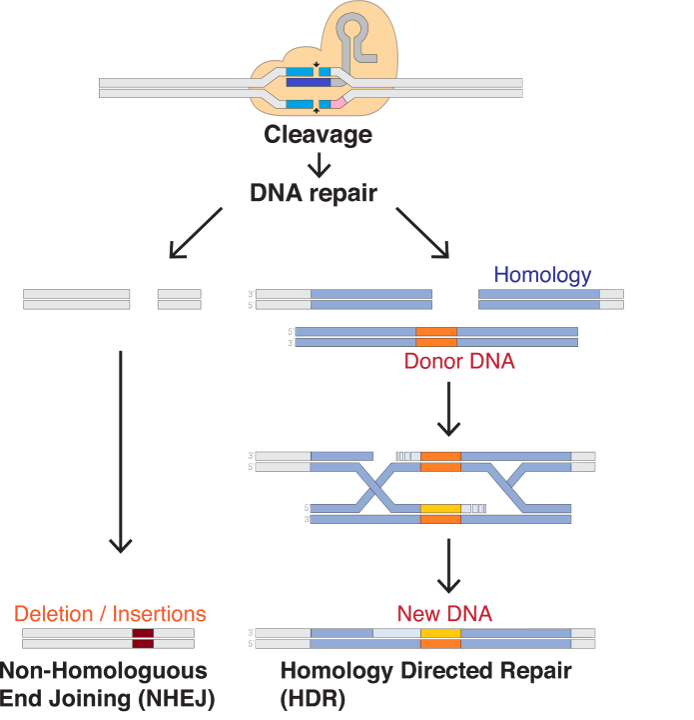

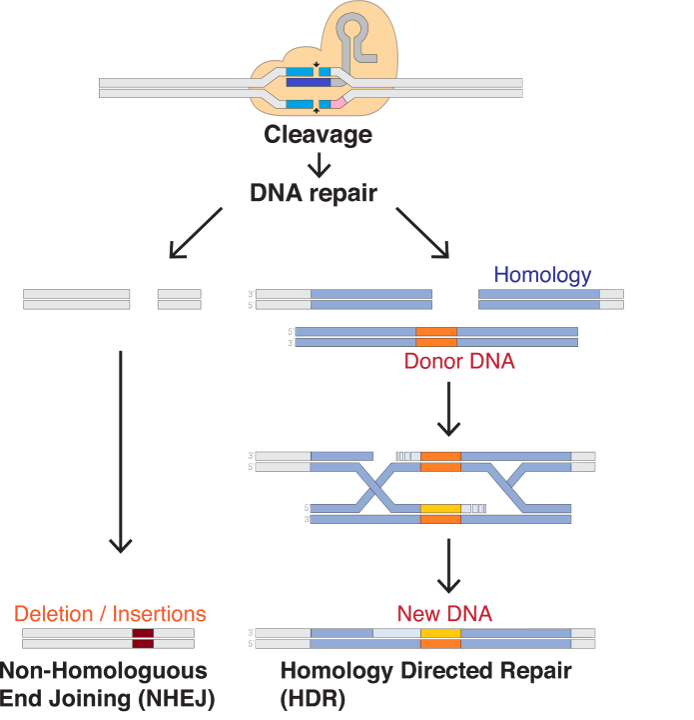

The resulting cleavage event enables most genome-editing technologies to work. After a break is created, the cell seeks to repair it.

* A method is NHEJ, in which the cell polishes the two ends of broken DNA and seals them back together, often producing a frame shift.

* An alternative method is homology-directed repairs. The cell tries to fix the damage by using a copy of the sequence as a backup. By supplying their own template, researcher can have the system to insert a desired sequence instead.

The success of using ZFNs in gene therapy depends on the insertion of genes to the chromosomal target area without causing damage to the cell. Custom ZFNs offer an option in human cells for gene correction.

CRISPR/Cas9

The CRISPR/Cas9 system (

The CRISPR/Cas9 system (CRISPR

CRISPR (; acronym of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. Each sequence within an individual prokaryotic CRISPR is d ...

– Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, Cas9

Cas9 (CRISPR associated protein 9, formerly called Cas5, Csn1, or Csx12) is a 160 dalton (unit), kilodalton protein which plays a vital role in the immunological defense of certain bacteria against DNA viruses and plasmids, and is heavily utili ...

– CRISPR-associated protein 9) is a genome editing technology based on the bacterial

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

antiviral CRISPR/Cas system. The bacterial system has evolved to recognize viral nucleic acid sequences and cut these sequences upon recognition, damaging infecting viruses. The gene editing technology uses a simplified version of this process, manipulating the components of the bacterial system to allow location-specific gene editing.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system broadly consists of two major components – the Cas9 nuclease

In biochemistry, a nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds that link nucleotides together to form nucleic acids. Nucleases variously affect single and ...

and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA contains a Cas-binding sequence and a ~20 nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

spacer sequence, which is specific and complementary to the target sequence on the DNA of interest. Editing specificity can therefore be changed by modifying this spacer sequence.

Upon system delivery to a cell, Cas9 and the gRNA bind, forming a

Upon system delivery to a cell, Cas9 and the gRNA bind, forming a ribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating inter ...

complex. This causes a conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

in Cas9, allowing it to cleave DNA if the gRNA spacer sequence binds with sufficient homology to a particular sequence in the host genome. When the gRNA binds to the target sequence, Cas will cleave the locus, causing a double-strand break

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

(DSB).

The resulting DSB can be repaired by one of two mechanisms –

*Non-Homologous End Joining

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is a pathway that repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. It is called "non-homologous" because the break ends are directly ligated without the need for a homologous template, in contrast to homology directed repair ...

(NHEJ) - an efficient but error-prone mechanism, which often introduces insertions and deletions (indels

Indel (insertion-deletion) is a molecular biology term for an insertion or deletion of bases in the genome of an organism. Indels ≥ 50 bases in length are classified as structural variants.

In coding regions of the genome, unless the lengt ...

) at the DSB site. This means it is often used in knockout

A knockout (abbreviated to KO or K.O.) is a fight-ending, winning criterion in several full-contact combat sports, such as boxing, kickboxing, Muay Thai, mixed martial arts, karate, some forms of taekwondo and other sports involving striking, ...

experiments to disrupt genes and introduce loss of function mutations.

*Homology Directed Repair

Homology-directed repair (HDR) is a mechanism in cells to repair double-strand DNA lesions. The most common form of HDR is homologous recombination. The HDR mechanism can only be used by the cell when there is a homologous piece of DNA presen ...

(HDR) - a less efficient but high-fidelity process which is used to introduce precise modifications into the target sequence. The process requires adding a DNA repair template including a desired sequence, which the cell's machinery uses to repair the DSB, incorporating the sequence of interest into the genome.

Since NHEJ is more efficient than HDR, most DSBs will be repaired ''via'' NHEJ, introducing gene knockouts. To increase frequency of HDR, inhibiting genes associated with NHEJ and performing the process in particular cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

phases (primarily S and G2) appear effective.

CRISPR/Cas9 is an effective way of manipulating the genome ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

'' in animals as well as in human cells ''in vitro'', but some issues with the efficiency of delivery and editing mean that it is not considered safe for use in viable human embryos or the body's germ cells. As well as the higher efficiency of NHEJ making inadvertent knockouts likely, CRISPR can introduce DSBs to unintended parts of the genome, called off-target effects. These arise due to the spacer sequence of the gRNA conferring sufficient sequence homology to random loci in the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, which can introduce random mutations throughout. If performed in germline cells, mutations could be introduced to all the cells of a developing embryo.

There are developments to prevent unintended consequences otherwise known as off-target effects due to gene editing. There is a race to develop new gene editing technologies that prevent off-target effects from occurring with some of the technologies being known as biased off-target detection, and Anti-CRISPR Proteins. For biased off-target effects detection, there are several tools to predict the locations where off-target effects may take place. Within the technology of biased off-target effects detection, there are two main models, Alignment Based Models that involve having the sequences of gRNA being aligned with sequences of genome, after which then the off-target locations are predicted. The second model is known as the Scoring-Based Model where each piece of gRNA is scored for their off-target effects in accordance with their positioning.

Regulation on CRISPR use

In 2015, the International Summit on Human Gene Editing was held inWashington D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, hosted by scientists from China, the UK and the U.S. The summit concluded that genome editing of somatic cells using CRISPR and other genome editing tools would be allowed to proceed under FDA

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

regulations, but human germline engineering would not be pursued.

In February 2016, scientists at the Francis Crick Institute

The Francis Crick Institute (formerly the UK Centre for Medical Research and Innovation) is a biomedical research centre in London, which was established in 2010 and opened in 2016. The institute is a partnership between Cancer Research UK, Im ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

were given a license permitting them to edit human embryos using CRISPR to investigate early development. Regulations were imposed to prevent the researchers from implanting the embryos and to ensure experiments were stopped and embryos destroyed after seven days.

In November 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui

He Jiankui ( zh, s=贺建奎, p=Hè Jiànkuí ; born 1984) is a Chinese biophysicist known for his controversial first use of genome editing in humans.

He served as associate professor of biology at the Southern University of Science and ...

announced that he had performed the first germline engineering on viable human embryos, which have since been brought to term. The research claims received significant criticism, and Chinese authorities suspended He's research activity. Following the event, scientists and government bodies have called for more stringent regulations to be imposed on the use of CRISPR technology in embryos, with some calling for a global moratorium on germline genetic engineering. Chinese authorities have announced stricter controls will be imposed, with Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping, pronounced (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (China), chairman of the Central Military Commission ...

and government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

premier Li Keqiang

Li Keqiang ( zh, s=李克强, p=Lǐ Kèqiáng; 3 July 1955 – 27 October 2023) was a Chinese economist and politician who served as the seventh premier of China from 2013 to 2023. He was also the second-ranked member of the Politburo Standing ...

calling for new gene-editing legislations to be introduced.

As of January 2020, germline genetic alterations are prohibited in 24 countries by law and also in 9 other countries by their guidelines. The Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

's Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, also known as the Oviedo Convention, has stated in its article 13 "Interventions on the human genome" as follows: "An intervention seeking to modify the human genome may only be undertaken for preventive, diagnostic or therapeutic purposes and only if its aim is not to introduce any modification in the genome of any descendants". Nonetheless, wide public debate has emerged, targeting the fact that the Oviedo Convention Article 13 should be revisited and renewed, especially due to the fact that it was constructed in 1997 and may be out of date, given recent technological advancements in the field of genetic engineering.

In 2020, Canada amended its Human Reproduction Act to criminalize heritable genome edits, in which penalties include fines up to CAD$500,000 and 10 years imprisonment. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

established a global registry for such practices in 2021 to enhance transparency

Recent Advancements

Following the 2018 incident of the first CRISPR-edited babies byHe Jiankui

He Jiankui ( zh, s=贺建奎, p=Hè Jiànkuí ; born 1984) is a Chinese biophysicist known for his controversial first use of genome editing in humans.

He served as associate professor of biology at the Southern University of Science and ...

, efforts to strengthen regulatory oversights have helped to improve the precision of the procedure. These advancements in genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly insert ge ...

now reduce off-target effects, allowing for more controlled and predictable modifications. Techniques such as prime editing and base editing have offered greater accuracy and fewer unintended mutations. Even so, ethical concerns persist as regulatory enforcement remains inconsistent in nations without strict biosafety laws

Lulu and Nana controversy

The Lulu and Nana controversy refers to the two Chinese twin girls born in November 2018, who had been genetically modified as embryos by the Chinese scientist He Jiankui. The twins are believed to be the first genetically modified babies. The girls' parents had participated in a clinical project run by He, which involved IVF, PGD and genome editing procedures in an attempt to edit the geneCCR5

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

In humans, the ''CCR5'' gene that encodes the CCR5 p ...

. CCR5 encodes a protein used by HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

to enter host cells, so by introducing a specific mutation into the gene CCR5 Δ32 He claimed that the process would confer innate resistance to HIV

A small proportion of humans show partial or apparently complete innate resistance to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. The main mechanism is a mutation of the gene encoding CCR5, which acts as a co-receptor for HIV. It is estimated that the propor ...

.

The project run by He recruited couples wanting children where the man was HIV-positive

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

and the woman uninfected. During the project, He performed IVF with sperm and eggs from the couples and then introduced the CCR5 Δ32 mutation into the genomes of the embryos using CRISPR/Cas9. He then used PGD on the edited embryos during which he sequenced biopsied cells to identify whether the mutation had been successfully introduced. He reported some mosaicism in the embryos, whereby the mutation had integrated into some cells but not all, suggesting the offspring would not be entirely protected against HIV. He claimed that during the PGD and throughout the pregnancy, fetal DNA was sequenced to check for off-target errors introduced by the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, however the NIH released a statement in which they announced "the possibility of damaging off-target effects has not been satisfactorily explored". The girls were born in early November 2018, and were reported by He to be healthy.

His research was conducted in secret until November 2018, when documents were posted on the Chinese clinical trials registry and ''MIT Technology Review

''MIT Technology Review'' is a bimonthly magazine wholly owned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was founded in 1899 as ''The Technology Review'', and was re-launched without "''The''" in its name on April 23, 1998, under then pu ...

'' published a story about the project. Following this, He was interviewed by the ''Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

'' and presented his work on 27 November at the Second International Human Genome Editing Summit which was held in Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

.

Although the information available about this experiment is relatively limited, it is deemed that the scientist erred against many ethical, social and moral rules but also China's guidelines and regulations, which prohibited germ-line genetic modifications in human embryos, while conducting this trial. From a technological point of view, the CRISPR/Cas9 technique is one of the most precise and least expensive methods of gene modification to this day, whereas there are still a number of limitations that keep the technique from being labelled as safe and efficient. During the First International Summit on Human Gene Editing in 2015 the participants agreed that a halt must be set on germline genetic alterations in clinical settings unless and until: "(1) the relevant safety and efficacy issues have been resolved, based on appropriate understanding and balancing of risks, potential benefits, and alternatives, and (2) there is broad societal consensus about the appropriateness of the proposed application". However, during the second International Summit in 2018 the topic was once again brought up by stating: "Progress over the last three years and the discussions at the current summit, however, suggest that it is time to define a rigorous, responsible translational pathway toward such trials". Inciting that the ethical and legal aspects should indeed be revisited G. Daley, representative of the summit's management and Dean of Harvard Medical School depicted Dr. He's experiment as "a wrong turn on the right path".

The experiment was met with widespread criticism and was very controversial, globally as well as in China. Several bioethicists

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health (primarily focused on the human, but also increasingly includes animal ethics), including those emerging from advances in biology, medi ...

, researchers and medical professionals have released statements condemning the research, including Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is a professor of biology at the California Institute of Tech ...

who deemed the work "irresponsible" and one pioneer of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, biochemist Jennifer Doudna

Jennifer Anne Doudna (; born February 19, 1964) is an American biochemist who has pioneered work in CRISPR gene editing, and made other fundamental contributions in biochemistry and genetics. She received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, wit ...

at University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

. The director of the NIH, Francis S. Collins stated that the "medical necessity for inactivation of CCR5 in these infants is utterly unconvincing" and condemned He Jiankui and his research team for 'irresponsible work'. Other scientists, including geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic process ...

George Church of Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

suggested gene editing for disease resistance was "justifiable" but expressed reservations regarding the conduct of He's work.

The Safe Genes program by DARPA has the goal to protect soldiers against gene editing war tactics. They receive information from ethical experts to better predict and understand future and current potential gene editing issues.

The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

has launched a global registry to track research on human genome editing, after a call to halt all work on genome editing.

The Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Peking Union Medical College, also as Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, is a national public medical sciences research institution in Dongcheng, Beijing, Dongcheng, Beijing, China. Originally founded in 1906, it is affiliated with the Nationa ...

responded to the controversy in the journal ''Lancet'', condemning He for violating ethical guidelines documented by the government and emphasizing that germline engineering should not be performed for reproductive purposes. The academy ensured they would "issue further operational, technical and ethical guidelines as soon as possible" to impose tighter regulation on human embryo editing.

As of 2023, He has resumed research in genetic medicine after his three year imprisonment by the Chinese government for his "illegal medical practices." He has since shifted his focus to the treatment of genetic diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), after his release. Despite backlashes from the Lulu and Nana case, he has been appointed as the inaugural director of the Genetic Medicine Institute at Wuchang University of Technology in Wuhan in September 2023. He's application to work in Hong Kong was initially granted a visa, however, it was later revoked due to ongoing ethical and legal challenges surrounding his career.

As of 2023, He has resumed research in genetic medicine after his three year imprisonment by the Chinese government for his "illegal medical practices." He has since shifted his focus to the treatment of genetic diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), after his release. Despite backlashes from the Lulu and Nana case, he has been appointed as the inaugural director of the Genetic Medicine Institute at Wuchang University of Technology in Wuhan in September 2023. He's application to work in Hong Kong was initially granted a visa, however, it was later revoked due to ongoing ethical and legal challenges surrounding his career.

Ethical considerations

Editing embryos, germ cells and the generation of designer babies is the subject of ethical debate, as a result of the implications in modifying genomic information in a heritable manner. This includes arguments over unbalanced gender selection and gamete selection. Despite regulations set by individual countries' governing bodies, the absence of a standardized regulatory framework leads to frequent discourse in discussion of germline engineering among scientists, ethicists and the general public.Arthur Caplan

Arthur L. Caplan (born 1950) is an American ethicist and professor of bioethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

He is known for his contributions to the U.S. public policy, including: helping to found the National Marrow D ...

, the head of the Division of Bioethics at New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private university, private research university in New York City, New York, United States. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded in 1832 by Albert Gallatin as a Nondenominational ...

suggests that establishing an international group to set guidelines for the topic would greatly benefit global discussion and proposes instating "religious and ethics and legal leaders" to impose well-informed regulations.

In many countries, editing embryos and germline modification for reproductive use is illegal. As of 2017, the U.S. restricts the use of germline modification and the procedure is under heavy regulation by the FDA and NIH. The American National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

and National Academy of Medicine

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM), known as the Institute of Medicine (IoM) until 2015, is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Medicine is a part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineerin ...

indicated they would provide qualified support for human germline editing "for serious conditions under stringent oversight", should safety and efficiency issues be addressed. In 2019, World Health Organization called human germline genome editing as "irresponsible".

Since genetic modification poses risk to any organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

, researchers and medical professionals must give the prospect of germline engineering careful consideration. The main ethical concern is that these types of treatments will produce a change that can be passed down to future generations and therefore any error, known or unknown, will also be passed down and will affect the offspring. Theologian Ronald Green of Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

has raised concern that this could result in a decrease in genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

and the accidental introduction of new diseases in the future.

When considering support for research into germline engineering, ethicists have often suggested that it can be considered unethical not to consider a technology that could improve the lives of children who would be born with congenital disorders

A birth defect is an abnormal condition that is present at birth, regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can range from mild to severe. Birth de ...

. Geneticist George Church claims that he does not expect germline engineering to increase societal disadvantage, and recommends lowering costs and improving education surrounding the topic to dispel these views. He emphasizes that allowing germline engineering in children who would otherwise be born with congenital defects could save around 5% of babies from living with potentially avoidable diseases. Jackie Leach Scully, professor of social and bioethics

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health (primarily focused on the human, but also increasingly includes animal ethics), including those emerging from advances in biology, me ...

at Newcastle University

Newcastle University (legally the University of Newcastle upon Tyne) is a public research university based in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. It has overseas campuses in Singapore and Malaysia. The university is a red brick university and a mem ...

, acknowledges that the prospect of designer babies could leave those living with diseases and unable to afford the technology feeling marginalized and without medical support. However, Professor Leach Scully also suggests that germline editing provides the option for parents "to try and secure what they think is the best start in life" and does not believe it should be ruled out. Similarly, Nick Bostrom

Nick Bostrom ( ; ; born 10 March 1973) is a Philosophy, philosopher known for his work on existential risk, the anthropic principle, human enhancement ethics, whole brain emulation, Existential risk from artificial general intelligence, superin ...

, an Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

known for his work on the risks of artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capability of computer, computational systems to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making. It is a field of re ...

, proposed that "super-enhanced" individuals could "change the world through their creativity and discoveries, and through innovations that everyone else would use".

Many bioethicists emphasize that germline engineering is usually considered in the best interest of a child, therefore associated should be supported. Dr James Hughes, a bioethicist at Trinity College, Connecticut, suggests that the decision may not differ greatly from others made by parents which are well accepted – choosing with whom to have a child and using contraception to denote when a child is conceived. Julian Savulescu, a bioethicist and philosopher at Oxford University believes parents "should allow selection for non‐disease genes even if this maintains or increases social inequality", coining the term ''procreative beneficence'' to describe the idea that the children "expected to have the best life" should be selected. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics said in 2017 that there was "no reason to rule out" changing the DNA of a human embryo if performed in the child's interest, but stressed that this was only provided that it did not contribute to societal inequality. Furthermore, Nuffield Council in 2018 detailed applications, which would preserve equality and benefit humanity, such as elimination of hereditary disorders and adjusting to warmer climate. Philosopher and Director of Bioethics at non-profit Invincible Wellbeing David Pearce argues that "the question f designer babiescomes down to an analysis of risk-reward ratios - and our basic ethical values, themselves shaped by our evolutionary past." According to Pearce,"it's worth recalling that each act of old-fashioned sexual reproduction is itself an untested genetic experiment", often compromising a child's wellbeing and pro-social capacities even if the child grows in a healthy environment. Pearce thinks that as technology matures, more people may find it unacceptable to rely on "genetic roulette of natural selection".

Conversely, several concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of generating designer babies, especially concerning the inefficiencies currently presented by the technologies. Green stated that although the technology was "unavoidably in our future", he foresaw "serious errors and health problems as unknown genetic side effects in 'edited' children" arise. Furthermore, Green warned against the possibility that "the well-to-do" could more easily access the technologies "..that make them even better off". This concern regarding germline editing exacerbating a societal and financial divide is shared amongst other researches, with the chair of the Nuffield Bioethics Council Professor Karen Yeung stressing that if funding of the procedures "were to exacerbate social injustice, in our view that would not be an ethical approach".

Since 2020, there have been discussions about American studies that use embryos without embryonic implantation with the CRISPR/Cas9 technique that had been modified with HDR (homology-directed repair), and the conclusions from the results were that gene editing technologies are currently not mature enough for real world use and that there is a need for more studies that generate safe results over a longer period of time.

An article in the journal ''Bioscience Reports'' discussed how health in terms of genetics is not straightforward and thus there should be extensive deliberation for operations involving gene editing when the technology gets mature enough for real world use, where all of the potential effects are known on a case-by-case basis to prevent undesired effects on the subject or patient being operated on.

Social aspects also raise concern, as highlighted by Josephine Quintavelle, director of ''Comment on Reproductive Ethics'' at Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL, or informally QM, and formerly Queen Mary and Westfield College) is a public university, public research university in Mile End, East London, England. It is a member institution of the federal University ...

, who states that selecting children's traits is "turning parenthood into an unhealthy model of self-gratification rather than a relationship". In addition, some disability advocates argue that selecting against traits like deafness reinforces societal stigma. This promotes a narrow definition of normalcy. They also warn of the consequences of increased inequality if genetic enhancements become solely accessible to the wealthy.

One major worry among scientists, including Marcy Darnovsky at the Center for Genetics and Society in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, is that permitting germline engineering for correction of disease phenotypes is likely to lead to its use for cosmetic purposes and enhancement. Meanwhile, Henry Greely, a bioethicist at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

in California, states that "almost everything you can accomplish by gene editing, you can accomplish by embryo selection", suggesting the risks undertaken by germline engineering may not be necessary. Alongside this, Greely emphasizes that the beliefs that genetic engineering will lead to enhancement are unfounded, and that claims that we will enhance intelligence and personality are far off – "we just don't know enough and are unlikely to for a long time – or maybe for ever".

Religious Opinions

Religious worries also arise over the possibility of editing human embryos. In a survey conducted by thePew Research Centre

The Pew Research Center (also simply known as Pew) is a nonpartisan American think tank based in Washington, D.C. It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the world. It ...

, it was found that only a third of the Americans surveyed who identified as strongly Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

approved of germline editing. Catholic leaders are in the middle ground. This stance is because, according to Catholicism, a baby is a gift from God, and Catholics believe that people are created to be perfect in God's eyes. Thus, altering the genetic makeup of an infant is unnatural. In 1984, Pope John Paul II addressed that genetic manipulation in aiming to heal diseases is acceptable in the Church. He stated that it "will be considered in principle as desirable provided that it tends to the real promotion of the personal well-being of man, without harming his integrity or worsening his life conditions". However, it is unacceptable if designer babies are used to create a super/superior race including cloning humans. The Catholic Church rejects human cloning even if its purpose is to produce organs for therapeutic usage. The Vatican has stated that "The fundamental values connected with the techniques of artificial human procreation are two: the life of the human being called into existence and the special nature of the transmission of human life in marriage". According to them, it violates the dignity of the individual and is morally illicit.

In Islam, a positive view towards genetic engineering is based on the general principle that Islam aims at facilitating human life. However, according to Islamic law, gene editing can only be permitted if several conditions are met, such as definitively proving the safety and efficacy of the procedures in question. Nevertheless, some researchers consider genetic engineering a promising field of research that is capable of meeting the conditions mentioned above in the future. In addition, a negative view comes from the process used to create a designer baby. Oftentimes, it involves the destruction of some embryos, which may be against the teaching of the Qur'an, Hadith, and Shari'ah law, that stress the responsibility to protect human life. However, there is a consensus among Islamic scholars that ensoulment

In religion and philosophy, ensoulment (from the verb ensoul meaning to endow or imbue with a soul -- earliest ascertainable word use: 1605) is the moment at which a human or other being gains a soul. Some belief systems maintain that a soul is ...

occurs 120 days after conception, well after the embryonic stage of development. Some scholars see the procedure as "acting like God/Allah" and a violation of the religious prohibition against "changing God's/Allah's creation". Other arguments include the possibility of introducing unforeseen mutations and genetic deficiencies, which would be counter to the principle of protecting human life, and undermining the traditional institutions of lineage, marriage and childbirth. With the idea that parents could choose the gender of their child, some Muslims believe that humans have no decision to choose the gender, and that "gender selection is only up to God".

Public Opinon

Surveys of public attitudes towards designer babies and genetic editing have revealed concerns against the technological advancements, showing fears of eugenics and socioeconomic inequality. A 2018Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center (also simply known as Pew) is a nonpartisan American think tank based in Washington, D.C. It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the world. It ...

study found that 72% of the U.S. adults believed non-medical uses of the technologies would be taking it too far, with many drawing parallels to historical Eugenic practices. Similarly, a 2020 international survey published in ''Science (journal)

''Science'' is the peer review, peer-reviewed academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and one of the world's top academic journals.

It was first published in 1880, is currently circulated weekly and h ...

'' reported widespread public concern about the unintended health consequences of genetically modified children and the potential erosion of genetic diversity.

Scientists and policymakers have called for a more inclusive and transparent approach in regulation of the technologies, which underscores the need for collaborative governance frameworks and communication between scientists, policymakers, and the people.

See also

* Biohappiness * Directed evolution (transhumanism) * Epidemiology of genetic disorder *Eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

** New eugenics