Descant Horn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A descant, discant, or is any of several different things in

A descant, discant, or is any of several different things in

<< <<

\new Staff

\new Staff

\new Staff

>> >>

\layout

\midi

Among composers of descants during 1915 to 1934 were

Selection of hymnal descants

Melody types Musical terminology

A descant, discant, or is any of several different things in

A descant, discant, or is any of several different things in music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, depending on the period in question; etymologically, the word means a voice (''cantus'') above or removed from others. The ''Harvard Dictionary of Music'' states:

A descant is a form of medieval music

Medieval music encompasses the sacred music, sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the Dates of classical music eras, first and longest major era of Western class ...

in which one singer sang a fixed melody

A melody (), also tune, voice, or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combination of Pitch (music), pitch and rhythm, while more figurativel ...

, and others accompanied with improvisations

Improvisation, often shortened to improv, is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. The origin of the word itself is in the Latin "improvisus", which literally means un-foreseen. Improvis ...

. The word in this sense comes from the term ' (descant "above the book"), and is a form of Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainsong, plainchant, a form of monophony, monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek language, Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed main ...

in which only the melody is notated but an improvised polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chord ...

is understood. The ' had specific rules governing the improvisation of the additional voices.

Later on, the term came to mean the treble or soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hertz, Hz to A5 in Choir, choral ...

singer in any group of voices, or the higher pitched line in a song. Eventually, by the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, descant referred generally to counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

. Nowadays the counterpoint meaning is the most common.

Descant can also refer to the highest pitched of a group of instruments, particularly the descant viol

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

or recorder Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a newsp ...

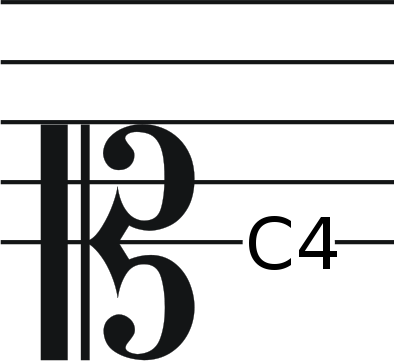

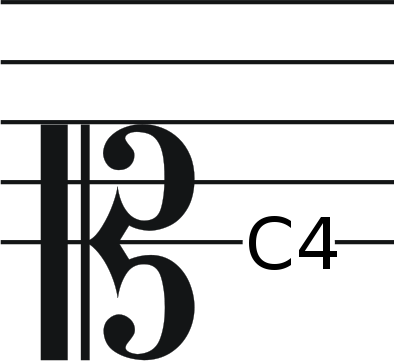

. Similarly, it can also be applied to the soprano clef

A clef (from French: 'key') is a musical symbol used to indicate which notes are represented by the lines and spaces on a musical staff. Placing a clef on a staff assigns a particular pitch to one of the five lines or four spaces, whic ...

.

In modern usage, especially in the context of church music, descant can also refer to a high, florid melody sung by a few sopranos as a decoration for a hymn.

Origin and development

Descant is a type of medieval polyphony characterized by relatively strict note-for-notecounterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

. It is found in the organum

''Organum'' () is, in general, a plainchant melody with at least one added voice to enhance the harmony, developed in the Middle Ages. Depending on the mode and form of the chant, a supporting bass line (or '' bourdon'') may be sung on the sam ...

with a plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ; ) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. Plainsong was the exclusive for ...

tenor (i.e. low voice; ''vox principis''), and in the conductus

The ''conductus'' (plural: ''conducti'') was a sacred Latin song in the Middle Ages, one whose poetry and music were newly composed. It is non-liturgical since its Latin lyric borrows little from previous chants. The conductus was northern Fren ...

without the requirement of a plainchant tenor. It is sometimes contrasted with the organum in a more restricted sense of the term (see 12-century Aquitanian polyphony below).Rudolf Flotzinger

Rudolf Flotzinger (born 22 September 1939) is an Austrian musicologist.

Career

Born in Vorchdorf (Austria), Flotzinger graduated from the where he was a student from 1951 to 1958.

, "Discant escant, descaunt(e), deschant, deschaunt(e), dyscant; verb: discanten, §I. Discant in France, Spain and Germany, 1. Etymology, Definition, ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie

Stanley John Sadie (; 30 October 1930 – 21 March 2005) was a British musicologist, music critic, and editor. He was editor of the sixth edition of the '' Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' (1980), which was published as the first edition ...

and John Tyrrell. (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001); Janet Knapp, "Discant", ''Harvard Dictionary of Music'', fourth edition, edited by Don Michael Randel, Harvard University Press Reference Library 16 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003) .

The term continued to be used down to modern times with changing senses, at first for polyphony in general, then to differentiate a subcategory of polyphony (either in contrast to organum, or for improvised as distinct from written polyphony). By extension it became the name of a part that is added above the tenor, and later as the name of the highest part in a polyphonic setting (the equivalent of "cantus", "superius", and "soprano"). Finally, it was adopted as the name of the highest register of instruments such as recorders, cornets, viols, and organ stops.

"English discant is three-voice parallelism in first-inversion triads." However, because it allowed only three, four, or at most five such chords in succession, emphasizing contrary motion as the basic condition, it "did not differ from the general European discant tradition of the time".Ernest H. Sanders and Peter M. Lefferts, "Discant: II. English Discant", ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001). Because English discant technique has commonly been associated with such a succession of first-inversion triads, it has inevitably become confused with ''fauxbourdon

Fauxbourdon (also fauxbordon, and also commonly two words: faux bourdon or faulx bourdon, and in Italian falso bordone) – Music of France, French for ''false drone'' – is a technique of musical harmony, harmonisation used in the late Medieval ...

'', with which it has "no connection whatsoever".Sylvia W. Kenney, "'English Discant' and Discant in England", ''Musical Quarterly'' 45, no. 1 (January 1959): pp. 26–48. Citation on pp. 26 and 41. This misinterpretation was first brought forward in 1936 by Manfred Bukofzer

Manfred Fritz Bukofzer (27 March 1910 – 7 December 1955) was a German-born American musicologist.

Life and career

He studied at Heidelberg University and the Stern conservatory in Berlin, but left Germany in 1933 for Switzerland, where he o ...

, but has been proved invalid, first in 1937 by Thrasybulos Georgiades

Thrasybulos Georgios Georgiades (; Athens, 4 January 1907 – Munich, 15 March 1977) was a Greek musicologist, pianist, civil engineer and philosopher. He was for many years director of the Institute of Musicology at the Ludwig Maximilian Universi ...

, and then by Sylvia Kenney

Sylvia Wisdom Kenney (November 27, 1922 – October 31, 1968) was an American musicologist. She originally performed as a violist and played for the United Service Organizations in World War II. After completing her graduate studies, she worked ...

and Ernest H. Sanders. A second hypothesis, that an unwritten tradition of this kind of parallel discant existed in England before 1500, "is supported neither by factual evidence nor by probability".

In hymns

Hymn tune

A hymn tune is the melody of a musical composition to which a hymn text is sung. Musically speaking, a hymn is generally understood to have four-part (or more) harmony, a fast harmonic rhythm (chords change frequently), with or without refrain ...

descants are counter-melodies, generally at a higher pitch than the main melody. Typically they are sung in the final or penultimate verse of a hymn.

Although the English Hymnal

''The English Hymnal'' is a hymn book which was published in 1906 for the Church of England by Oxford University Press. It was edited by the clergyman and writer Percy Dearmer and the composer and music historian Ralph Vaughan Williams, and wa ...

of 1906 did not include descants, this influential hymnal, whose music editor was Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams ( ; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

, served as a source of tunes for which the earliest known hymn tune descants were published. These were in collections compiled by Athelstan Riley

John Athelstan Laurie Riley (10 August 1858 – 17 November 1945) was an English Hymnwriter, hymn writer and hymn translator.

Biography

Riley was born in Paddington, London, and attended Pembroke College, Oxford, where obtained his BA in 1881 ...

, who wrote "The effect is thrilling; it gives the curious impression of an ethereal choir joining in the worship below; and those who hear it for the first time often turn and look up at the roof!". An example of a descant from this collection (for the British national anthem) goes as follows:

Alan Gray

Alan Gray (23 December 1855 – 27 September 1935) was an English organist and composer.

Life and career

Gray was born in into a well-known York family (the Grays of Grays Court). His father William Gray was a solicitor and (in 1844) Lor ...

, Geoffrey Shaw, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Several of their descants appear in what is possibly the earliest hymnal to include descants, ''Songs of Praise

''Songs of Praise'' is a BBC Television religious programme that presents Christian hymns, worship songs and inspirational performances in churches of varying denominations from around the UK alongside interviews and stories reflecting how Ch ...

'' (London: Oxford University Press, 1925, enlarged, 1931, reprinted 1971).

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, new editions of hymnals increased the number of included descants. For example, the influential ''Hymnal 1940'' (Episcopal) contains no descants, whereas its successor, ''The Hymnal 1982

''The Hymnal 1982'' is the primary hymnal of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. It is one in a series of seven official hymnals of the Episcopal Church, including ''The Hymnal 1940''. Unlike many Anglican churches (including t ...

'', contains 32. Among other currently used hymnals, ''The Worshiping Church'' contains 29 descants; ''The Presbyterian Hymnal'', 19; ''The New Century Hymnal

''The New Century Hymnal'' is a comprehensive hymnal and worship book published in 1995 for the United Church of Christ. The hymnal contains a wide-variety of traditional Christian hymns and worship songs, many contemporary hymns and songs, and a s ...

'', 10; ''Chalice Hymnal'', 21. The Vocal Descant Edition for ''Worship, Third Edition'' (GIA Publications, 1994) offers 254 descants by composers such as Hal Hopson

Hal H. Hopson (born 12 June 1933) is a full-time composer and church musician residing in Cedar Park, Texas. He has over 3000 published works, which comprise almost every musical form in church music. With a special interest in congregational song ...

, David Hurd

David Hurd (born 1950) is a composer, concert organist, choral director and educator.

Education

Hurd attended the High School of Music & Art, the Juilliard School, both in New York City, and Oberlin College. He holds honorary doctorates from Ber ...

, Robert Powell

Robert Thomas Powell ( ; born 1 June 1944) is an English actor who is known for the title roles in '' Mahler'' (1974) and '' Jesus of Nazareth'' (1977), and for his portrayal of secret agent Richard Hannay in '' The Thirty Nine Steps'' (1978) ...

, Richard Proulx, and Carl Schalk

Carl Flentge Schalk (September 26, 1929 – January 24, 2021) was a noted Lutheran composer, author, and lecturer. Between 1965 and 2004 he taught church music at Concordia University Chicago.

.

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, the ''Carols for Choirs

''Carols for Choirs'' is a collection of choral scores, predominantly of Christmas carols and hymns, first published in 1961 by Oxford University Press. It was edited by Sir David Willcocks and Reginald Jacques, and is a widely used source o ...

'' collection, which features descants by David Willcocks

Sir David Valentine Willcocks, (30 December 1919 – 17 September 2015) was a British choral conductor, organist, composer and music administrator. He was particularly well known for his association with the Choir of King's College, Cambridg ...

and others to well known Christmas tunes such as "O come, all ye faithful

"O Come, All Ye Faithful", also known as "", is a Christmas carol that has been attributed to various authors, including John Francis Wade (1711–1786), John Reading (1645–1692), King John IV of Portugal (1604–1656), and anonymous Ciste ...

" has contributed to the enduring popularity of the genre.

12th-century Aquitanian polyphony

This style was dominant in early 12th centuryAquitanian Aquitanian may refer to:

*Aquitanian (stage), a geological age, the first stage of the Miocene Epoch

*Aquitanian language, an ancient language spoken in the region later known as Gascony

*Aquitani (or Aquitanians), were a people living in what is n ...

polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chord ...

, and can be identified by the following characteristics:

# Both the tenor and upper parts move at about the same rate, using the ''equalitas punctorum'' (an approximately equal rate of movement in all the voices) with between one and three notes in the upper part to every note in the tenor part. At the end of a phrase however, in discant style, the upper part may have more notes, thus producing a more melisma

Melisma (, , ; from , plural: ''melismata''), informally known as a vocal run and sometimes interchanged with the term roulade, is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in ...

tic passage at a cadence.

# Throughout the discant passages, the two parts interchange between consonant intervals: octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

s, fifths.

# Discant style is characterised by the use of rhythmic modes throughout each part. In earlier types of organum, rhythm was either not notated as in organum purum, or notated in only the upper voice part, however Notre Dame composers devised a way of notating rhythm using ligatures and six different types of rhythmic modes.

Examples of this can be found in some of Léonin

Léonin (also Leoninus, Leonius, Leo; ) was the first known significant composer of polyphonic organum. He was probably French, probably lived and worked in Paris at the Notre-Dame Cathedral and was the earliest member of the Notre Dame schoo ...

’s late 12th-century settings. These settings are often punctuated with passages in discant style, where both the tenor and upper voice move in modal rhythms, often the tenor part in mode 5 (two long notes) and the upper part in mode 1 (a long then short note). Therefore it is easier to imagine how discant style would have sounded, and we can make a guess as to how to recreate the settings. It is suggested by scholars such as Grout

Grout is a dense substance that flows like a liquid yet hardens upon application, often used to fill gaps or to function as reinforcement in existing structures. Grout is generally a mixture of water, cement, and sand, and is frequently employe ...

, that Léonin used this non-melisma

Melisma (, , ; from , plural: ''melismata''), informally known as a vocal run and sometimes interchanged with the term roulade, is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in ...

tic style in order to mirror the grandeur of Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. It ...

itself.

Current research suggests that the word 'discantus' was formed with the intention of providing a separate term for a newly developed type of polyphony. If true, then it is ironic that the newer term, "discantus", ended up being applied to the older note-against-note style, while the older word "organum" was transferred to the more innovative style of florid-against-sustained-note polyphony. This may have been partly because the 12th century was an era that believed in progress, so that the more familiar "organum" was kept for the style then considered to be the most up-to-date.Rudolf Flotzinger

Rudolf Flotzinger (born 22 September 1939) is an Austrian musicologist.

Career

Born in Vorchdorf (Austria), Flotzinger graduated from the where he was a student from 1951 to 1958.

, "Organum, §6: ‘Organum’ and ‘Discant’: New Terminology". ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

Discant in three or four voices

The development of modal rhythms enabled the progression from two part discant style to three and four part discant style. This is because, only voices, confined to a set rhythm can be combined effectively to make a set phrase. This was mainly related toPérotin

Pérotin () was a composer associated with the Notre Dame school of polyphony in Paris and the broader musical style of high medieval music. He is credited with developing the polyphonic practices of his predecessor Léonin, with the introd ...

, around 1200. The parts in these three and four part settings were not necessarily related to each other. Evidence suggests that the parts were either related to the tenor part, or composed independently. Either way, this formed the first ‘composition’, and provided a foundation for development, and a new style, ''conductus

The ''conductus'' (plural: ''conducti'') was a sacred Latin song in the Middle Ages, one whose poetry and music were newly composed. It is non-liturgical since its Latin lyric borrows little from previous chants. The conductus was northern Fren ...

'' was developed from the three and four part discant ideas.

See also

*Anglican church music

Anglican church music is music that is written for Christian worship in Anglican religious services, forming part of the liturgy. It mostly consists of pieces written to be sung by a church choir, which may sing ''a cappella'' or accompanied b ...

* Congregational singing

Congregational singing is the practice of the congregation participating in the music of a church, either in the form of hymns or a metrical Psalms or a free form Psalm or in the form of the office of the liturgy (for example Gregorian chants ...

* Hymn tunes

A hymn tune is the melody of a musical composition to which a hymn text is sung. Musically speaking, a hymn is generally understood to have four-part harmony, four-part (or more) harmony, a fast harmonic rhythm (chords change frequently), with o ...

* Last verse harmonisation

* Organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

References

Further reading

* Clark Kimberling, "Hymn Tune Descants, Part 1: 1915–1934", ''The Hymn'' 54 (no. 3) July 2003, pages 20–27. (Reprinted in ''Journal of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society'' 29 (February 2004) 17–20.) * Clark Kimberling, "Hymn Tune Descants, Part 2: 1935–2001", ''The Hymn'' 55 (no. 1) January 2004, pages 17–22. * Crocker, Richard L. 1962. "Discant, Counterpoint, and Harmony". ''Journal of the American Musicological Society'' 15, no. 1:1–21. * Flotzinger, Rudolf. 1969. ''Der Discantussatz im Magnus liber und seiner Nachfolge: mit Beiträgen zur Frage der sogenannten Notre-Dame-Handschriften''. Wiener musikwissenschaftliche Beiträge 8. Vienna, Cologne, and Graz: H. Böhlaus Nachfolger. * Flotzinger, Rudolf, Ernest H. Sanders, and Peter M. Lefferts. 2001. "Discant escant, descaunt(e), deschant, deschaunt(e), dyscant; verb: discanten. ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited byStanley Sadie

Stanley John Sadie (; 30 October 1930 – 21 March 2005) was a British musicologist, music critic, and editor. He was editor of the sixth edition of the '' Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' (1980), which was published as the first edition ...

and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

* Hughes, Andrew. 1966. "Mensural Polyphony for Choir in 15th-Century England", ''Journal of the American Musicological Society'' 19, no. 3 (Fall): 352–69.

* Hughes, Andrew. 1967. "The Old Hall Manuscript: a Re-appraisal". '' Musica Disciplina'' 21:97–129

* Kenney, Sylvia W. 1964. "The Theory of Discant". Chapter 5 of ''Walter Frye and the "Contenance Angloise"'', 91–122. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Reprinted, New York: Da Capo Press, 1980. .

* Knapp, Janet. 2003. "Discant". ''Harvard Dictionary of Music'', fourth edition, edited by Don Michael Randel. Harvard University Press Reference Library 16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. .

* Scott, Ann Besser. 1970. "The Performance of the Old Hall Descant Settings". ''Musical Quarterly'' 56, no. 1 (January): 14–26.

* Spiess, Lincoln B. 1955. "Discant, Descant, Diaphony, and Organum: a Problem in Definitions". ''Journal of the American Musicological Society'' 8, no. 2 (Summer):, 144–47.

* Trowell, Brian. 1959. "Faburden and Fauxbourdon". '' Musica Disciplina'' 8:43–78.

* Waite, William. 1952. "Discantus, Copula, Organum". ''Journal of the American Musicological Society'' 5, no. 2 (Summer): 77–87.

External links

{{Wiktionary, descantSelection of hymnal descants

Melody types Musical terminology