Deep-sea Community on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A deep-sea community is any

The first discovery of any deep-sea

The first discovery of any deep-sea

PDF

Two scientists, J. Corliss and J. van Andel, first witnessed dense chemosynthetic clam beds from the submersible ''

station 225

The reported depth was 4,475

The ocean can be conceptualized as being divided into various zones, depending on depth, and presence or absence of

The ocean can be conceptualized as being divided into various zones, depending on depth, and presence or absence of

These animals have

These animals have

/ref> The

The mesopelagic zone is the upper section of the midwater zone, and extends from below

The mesopelagic zone is the upper section of the midwater zone, and extends from below

The bathyal zone is the lower section of the midwater zone, and encompasses the depths of . Light does not reach this zone, giving it its nickname "the midnight zone"; due to the lack of light, it is less densely populated than the epipelagic zone, despite being much larger. Fish find it hard to live in this zone, as there is crushing pressure, cold temperatures of , a low level of

The bathyal zone is the lower section of the midwater zone, and encompasses the depths of . Light does not reach this zone, giving it its nickname "the midnight zone"; due to the lack of light, it is less densely populated than the epipelagic zone, despite being much larger. Fish find it hard to live in this zone, as there is crushing pressure, cold temperatures of , a low level of

The abyssal zone remains in perpetual darkness at a depth of . The only organisms that inhabit this zone are

The abyssal zone remains in perpetual darkness at a depth of . The only organisms that inhabit this zone are

Deep sea

Deep sea

/ref> Another scientific team, from the

community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

of organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s associated by a shared habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

in the deep sea

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combination of low tempe ...

. Deep sea communities remain largely unexplored, due to the technological and logistical challenges and expense involved in visiting this remote biome

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Tansley added the ...

. Because of the unique challenges (particularly the high barometric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013.2 ...

, extremes of temperature, and absence of light), it was long believed that little life existed in this hostile environment. Since the 19th century however, research has demonstrated that significant biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

exists in the deep sea.

The three main sources of energy and nutrients for deep sea communities are marine snow

In the deep ocean, marine snow (also known as "ocean dandruff") is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to ...

, whale fall

A whale fall occurs when the Carrion, carcass of a whale has fallen onto the ocean floor, typically at a depth greater than , putting them in the Bathyal zone, bathyal or abyssal zones. On the sea floor, these carcasses can create complex local ...

s, and chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

at hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s and cold seep

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where seepage of fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other hydrocarbons occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. ''Cold'' does not mean that the temperature ...

s.

History

Prior to the 19th century scientists assumed life was sparse in the deep ocean. In the 1870sSir Charles Wyville Thomson

Sir Charles Wyville Thomson (5 March 1830 – 10 March 1882) was a Scottish natural historian and marine zoologist. He served as the chief scientist on the ''Challenger'' expedition; his work there revolutionized oceanography and led to his b ...

and colleagues aboard the Challenger expedition

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific programme that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by W ...

discovered many deep-sea creatures of widely varying types.

The first discovery of any deep-sea

The first discovery of any deep-sea chemosynthetic

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

community including higher animals was unexpectedly made at hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s in the eastern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

during geological explorations (Corliss et al., 1979).Minerals Management Service

The Minerals Management Service (MMS) was an agency of the United States Department of the Interior that managed the nation's natural gas, oil and other mineral resources on the outer continental shelf (OCS).

Due to perceived conflict of intere ...

Gulf of Mexico OCS Region (November 2006). "Gulf of Mexico OCS Oil and Gas Lease Sales: 2007–2012. Western Planning Area Sales 204, 207, 210, 215, and 218. Central Planning Area Sales 205, 206, 208, 213, 216, and 222. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Volume I: Chapters 1–8 and Appendices". U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, New Orleans. page 3-27Two scientists, J. Corliss and J. van Andel, first witnessed dense chemosynthetic clam beds from the submersible ''

DSV Alvin

''Alvin'' (DSV-2) is a crewed deep-ocean research submersible owned by the United States Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) of Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The original vehicle was built by General Mills' Electr ...

'' on February 17, 1977, after their unanticipated discovery using a remote camera sled two days before.

The Challenger Deep

The Challenger Deep is the List of submarine topographical features#List of oceanic trenches, deepest known point of the seabed of Earth, located in the western Pacific Ocean at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, in the ocean territory o ...

is the deepest surveyed point of all of Earth's oceans; it is located at the southern end of the Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deep sea, deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maxi ...

near the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, between the 12th and 21st pa ...

group. The depression is named after HMS ''Challenger'', whose researchers made the first recordings of its depth on 23 March 1875 astation 225

The reported depth was 4,475

fathom

A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems equal to , used especially for measuring the depth of water. The fathom is neither an international standard (SI) unit, nor an internationally accepted non-SI unit. H ...

s (8184 meters) based on two separate soundings. In 1960, Don Walsh

Don Walsh (November 2, 1931 – November 12, 2023) was an American oceanographer, U.S. Navy officer and marine policy specialist. While aboard the bathyscaphe ''Trieste'', he and Jacques Piccard made a record maximum descent in the Challeng ...

and Jacques Piccard

Jacques Piccard (28 July 19221 November 2008) was a Swiss oceanographer and engineer, known for having developed submarines for studying ocean currents. In the Challenger Deep, he and Lieutenant Don Walsh of the United States Navy were the fi ...

descended to the bottom of the Challenger Deep in the ''Trieste'' bathyscaphe

A bathyscaphe () is a free-diving, self-propelled deep-sea submersible, consisting of a crew cabin similar to a '' Bathysphere'', but suspended below a float rather than from a surface cable, as in the classic ''Bathysphere'' design.

The floa ...

. At this great depth a small flounder-like fish was seen moving away from the spotlight of the bathyscaphe.

The Japanese remote operated vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROUV) or remotely operated vehicle (ROV) is a free-swimming submersible craft used to perform underwater observation, inspection and physical tasks such as valve operations, hydraulic functions and other ge ...

(ROV) '' Kaiko'' became the second vessel to reach the bottom of the Challenger Deep in March 1995. ''Nereus

In Greek mythology, Nereus ( ; ) was the eldest son of Pontus (the Sea) and Gaia ( the Earth), with Pontus himself being a son of Gaia. Nereus and Doris became the parents of 50 daughters (the Nereids) and a son ( Nerites), with whom Nereus ...

'', a hybrid remotely operated vehicle (HROV) of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it i ...

, is the only vehicle capable of exploring ocean depths beyond 7000 meters. ''Nereus'' reached a depth of 10,902 meters at the Challenger Deep on May 31, 2009. On 1 June 2009, sonar mapping of the Challenger Deep by the Simrad EM120 multibeam sonar bathymetry system aboard the R/V ''Kilo Moana'' indicated a maximum depth of . The sonar system uses phase

Phase or phases may refer to:

Science

*State of matter, or phase, one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist

*Phase (matter), a region of space throughout which all physical properties are essentially uniform

*Phase space, a mathematica ...

and amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of am ...

bottom detection, with an accuracy of better than 0.2% of water depth (this is an error of about 22 meters at this depth).

Environment

Darkness

sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

. Nearly all life forms

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to life forms:

A life form (also spelled life-form or lifeform) is an entity that is living, such as plants (flora), animals (fauna), and fungi ( funga). It is estimated tha ...

in the ocean depend on the photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

activities of phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

and other marine plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s to convert carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

into organic carbon

Total organic carbon (TOC) is an analytical parameter representing the concentration of organic carbon in a sample. TOC determinations are made in a variety of application areas. For example, TOC may be used as a non-specific indicator of wa ...

, which is the basic building block of organic matter

Organic matter, organic material or natural organic matter is the large source of carbon-based compounds found within natural and engineered, terrestrial, and aquatic environments. It is matter composed of organic compounds that have come fro ...

. Photosynthesis in turn requires energy from sunlight to drive the chemical reactions that produce organic carbon.

The stratum of the water column

The (oceanic) water column is a concept used in oceanography to describe the physical (temperature, salinity, light penetration) and chemical ( pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient salts) characteristics of seawater at different depths for a defined ...

up till which sunlight penetrates is referred to as the photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

. The photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

can be subdivided into two different vertical regions. The uppermost portion of the photic zone, where there is adequate light to support photosynthesis by phytoplankton and plants, is referred to as the euphotic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

(also referred to as the ''epipelagic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

'', or ''surface zone''). The lower portion of the photic zone, where the light intensity is insufficient for photosynthesis, is called the dysphotic zone (dysphotic means "poorly lit" in Greek). The dysphotic zone is also referred to as the ''mesopelagic zone'', or the ''twilight zone''. Its lowermost boundary is at a thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is

a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct te ...

of , which, in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

generally lies between 200 and 1000 meters.

The euphotic zone is somewhat arbitrarily defined as extending from the surface to the depth where the light intensity is approximately 0.1–1% of surface sunlight irradiance

In radiometry, irradiance is the radiant flux ''received'' by a ''surface'' per unit area. The SI unit of irradiance is the watt per square metre (symbol W⋅m−2 or W/m2). The CGS unit erg per square centimetre per second (erg⋅cm−2⋅s−1) ...

, depending on season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperat ...

, latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and degree of water turbidity

Turbidity is the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by large numbers of individual particles that are generally invisible to the naked eye, similar to smoke in air. The measurement of turbidity is a key test of both water clarity and wa ...

. In the clearest ocean water, the euphotic zone may extend to a depth of about 150 meters, or rarely, up to 200 meters. Dissolved substances and solid particles absorb and scatter light, and in coastal regions the high concentration of these substances causes light to be attenuated rapidly with depth. In such areas the euphotic zone may be only a few tens of meters deep or less. The dysphotic zone, where light intensity is considerably less than 1% of surface irradiance, extends from the base of the euphotic zone to about 1000 meters. Extending from the bottom of the photic zone down to the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

is the aphotic zone

The aphotic zone (aphotic from Greek prefix + "without light") is the portion of a lake or ocean where there is little or no sunlight. It is formally defined as the depths beyond which less than 1 percent of sunlight penetrates. Above the apho ...

, a region of perpetual darkness.

Since the average depth of the ocean is about 3688 meters, the photic zone represents only a tiny fraction of the ocean's total volume. However, due to its capacity for photosynthesis, the photic zone has the greatest biodiversity and biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

of all oceanic zones. Nearly all primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

in the ocean occurs here. Any life forms present in the aphotic zone must either be capable of movement upwards through the water column into the photic zone for feeding, or must rely on material sinking from above, or must find another source of energy and nutrition, such as occurs in chemosynthetic

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

found near hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s and cold seep

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where seepage of fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other hydrocarbons occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. ''Cold'' does not mean that the temperature ...

s.

Hyperbaricity

These animals have

These animals have evolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

to survive the extreme pressure of the sub-photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

s. The pressure increases by about one atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

every ten meters. To cope with the pressure, many fish are rather small, usually not exceeding 25 cm in length. Also, scientists have discovered that the deeper these creatures live, the more gelatinous their flesh and more minimal their skeletal structure. These creatures have also eliminated all excess cavities that would collapse under the pressure, such as swim bladders.

Pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

is the greatest environmental factor acting on deep-sea organisms. In the deep sea, although most of the deep sea is under pressures between 200 and 600 atm, the range of pressure is from 20 to 1,000 atm. Pressure exhibits a great role in the distribution of deep sea organisms. Until recently, people lacked detailed information on the direct effects of pressure on most deep-sea organisms, because virtually all organisms trawled from the deep sea arrived at the surface dead or dying. With the advent of traps that incorporate a special pressure-maintaining chamber, undamaged larger metazoan

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ho ...

animals have been retrieved from the deep sea in good condition. Some of these have been maintained for experimental purposes, and we are obtaining more knowledge of the biological effects of pressure.

Temperature

The two areas of greatest and most rapidtemperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

change in the oceans are the transition zone between the surface waters and the deep waters, the thermocline, and the transition between the deep-sea floor and the hot water flows at the hydrothermal vents. Thermoclines vary in thickness from a few hundred meters to nearly a thousand meters. Below the thermocline, the water mass of the deep ocean is cold and far more homogeneous. Thermoclines are strongest in the tropics, where the temperature of the epipelagic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

is usually above 20 °C. From the base of the epipelagic, the temperature drops over several hundred meters to 5 or 6 °C at 1,000 meters. It continues to decrease to the bottom, but the rate is much slower. Below 3,000 to 4,000 m, the water is isothermal

An isothermal process is a type of thermodynamic process in which the temperature ''T'' of a system remains constant: Δ''T'' = 0. This typically occurs when a system is in contact with an outside thermal reservoir, and a change in the sys ...

. At any given depth, the temperature is practically unvarying over long periods of time. There are no seasonal temperature changes, nor are there any annual changes. No other habitat on earth has such a constant temperature.

Hydrothermal vents are the direct contrast with constant temperature. In these systems, the temperature of the water as it emerges from the "black smoker" chimneys may be as high as 400 °C (it is kept from boiling by the high hydrostatic pressure) while within a few meters it may be back down to 2–4 °C.

Salinity

Salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

is constant throughout the depths of the deep sea. There are two notable exceptions to this rule:

#In the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, water loss through evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the Interface (chemistry), surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. A high concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evapora ...

greatly exceeds input from precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

and river runoff. Because of this, salinity in the Mediterranean is higher than in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

. Evaporation is especially high in its eastern half, causing the water level to decrease and salinity to increase in this area. The resulting pressure gradient pushes relatively cool, low-salinity water from the Atlantic Ocean across the basin. This water warms and becomes saltier as it travels eastward, then sinks in the region of the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

and circulates westward, to spill back into the Atlantic over the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

. The net effect of this is that at the Strait of Gibraltar, there is an eastward surface current of cold water of lower salinity from the Atlantic, and a simultaneous westward current of warm saline water from the Mediterranean in the deeper zones. Once back in the Atlantic, this chemically distinct Mediterranean Intermediate Water can persist for thousands of kilometers away from its source.

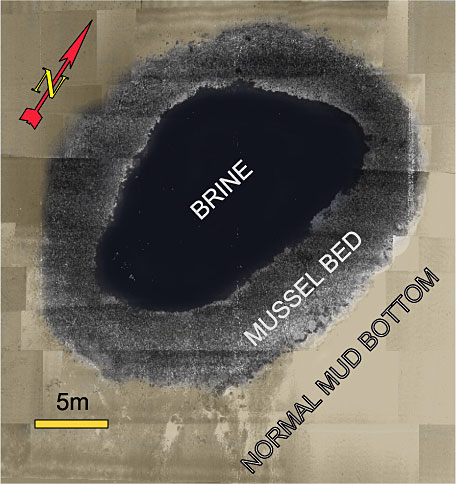

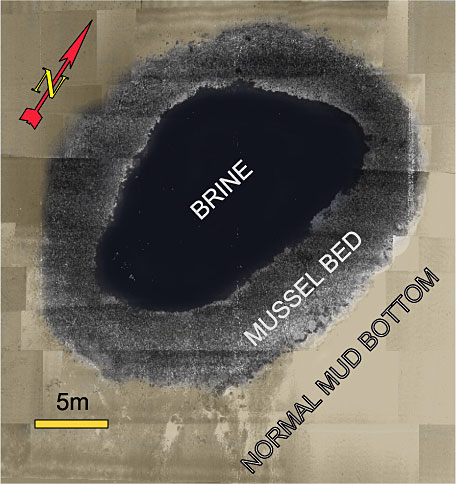

# Brine pools are large areas of brine

Brine (or briny water) is a high-concentration solution of salt (typically sodium chloride or calcium chloride) in water. In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawat ...

on the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

. These pools are bodies of water that have a salinity that is three to five times greater than that of the surrounding ocean. For deep sea brine pools the source of the salt is the dissolution of large salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

deposits through salt tectonics

upright=1.7

Salt tectonics, or halokinesis, or halotectonics, is concerned with the geometries and processes associated with the presence of significant thicknesses of evaporites containing rock salt within a stratigraphic sequence of rocks. This ...

. The brine often contains high concentrations of methane, providing energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

to chemosynthetic

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

extremophile

An extremophile () is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, press ...

s that live in this specialized biome

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Tansley added the ...

. Brine pools are also known to exist on the Antarctic continental shelf where the source of brine is salt excluded during formation of sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

. Deep sea and Antarctic brine pools can be toxic to marine animals. Brine pools are sometimes called ''seafloor lakes'' because the dense brine creates a halocline

A halocline (or salinity chemocline), from the Greek words ''hals'' (salt) and ''klinein'' (to slope), refers to a layer within a body of water ( water column) where there is a sharp change in salinity (salt concentration) with depth.

Haloclin ...

which does not easily mix with overlying seawater. The high salinity raises the density of the brine, which creates a distinct surface and shoreline for the pool.NOAA exploration of a brine pool/ref> The

deep sea

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combination of low tempe ...

, or deep layer, is the lowest layer in the ocean, existing below the thermocline, at a depth of or more. The deepest part of the deep sea is Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deep sea, deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maxi ...

located in the western North Pacific. It is also the deepest point of the Earth's crust. It has a maximum depth of about 10.9 km which is deeper than the height of Mount Everest

Mount Everest (), known locally as Sagarmatha in Nepal and Qomolangma in Tibet, is Earth's highest mountain above sea level. It lies in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas and marks part of the China–Nepal border at it ...

. In 1960, Don Walsh

Don Walsh (November 2, 1931 – November 12, 2023) was an American oceanographer, U.S. Navy officer and marine policy specialist. While aboard the bathyscaphe ''Trieste'', he and Jacques Piccard made a record maximum descent in the Challeng ...

and Jacques Piccard

Jacques Piccard (28 July 19221 November 2008) was a Swiss oceanographer and engineer, known for having developed submarines for studying ocean currents. In the Challenger Deep, he and Lieutenant Don Walsh of the United States Navy were the fi ...

reached the bottom of Mariana Trench in the ''Trieste'' bathyscaphe. The pressure is about 11,318 metric tons-force per square meter (110.99 MPa

MPA or mPa may refer to:

Academia

Academic degrees

* Master of Performing Arts

* Master of Professional Accountancy

* Master of Public Administration

* Master of Public Affairs

Schools

* Mesa Preparatory Academy

* Morgan Park Academy

* M ...

or 16100 psi

Psi, PSI or Ψ may refer to:

Alphabetic letters

* Psi (Greek) (Ψ or ψ), the twenty-third letter of the Greek alphabet

* Psi (Cyrillic), letter of the early Cyrillic alphabet, adopted from Greek

Arts and entertainment

* "Psi" as an abbreviat ...

).

Zones

Mesopelagic

The mesopelagic zone is the upper section of the midwater zone, and extends from below

The mesopelagic zone is the upper section of the midwater zone, and extends from below sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

. This is colloquially known as the "twilight zone" as light can still penetrate this layer, but it is too low to support photosynthesis. The limited amount of light, however, can still allow organisms to see, and creatures with a sensitive vision can detect prey, communicate, and orientate themselves using their sight. Organisms in this layer have large eyes to maximize the amount of light in the environment.

Most mesopelagic fish make daily vertical migrations, moving at night into the epipelagic zone, often following similar migrations of zooplankton, and returning to the depths for safety during the day. These vertical migrations often occur over a large vertical distances, and are undertaken with the assistance of a swimbladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ in bony fish that functions to modulate buoyancy, and thus allowing the fish to stay at desired water depth without having to maintain lift via swimming, w ...

. The swimbladder is inflated when the fish wants to move up, and, given the high pressures in the mesopelagic zone, this requires significant energy. As the fish ascends, the pressure in the swimbladder must adjust to prevent it from bursting. When the fish wants to return to the depths, the swimbladder is deflated. Some mesopelagic fishes make daily migrations through the thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is

a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct te ...

, where the temperature changes between , thus displaying considerable tolerances for temperature change.

Mesopelagic fish usually lack defensive spines, and use colour and bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms. Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorgani ...

to camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

them from other fish. Ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture their prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey u ...

s are dark, black or red. Since the longer, red, wavelengths of light do not reach the deep sea, red effectively functions the same as black. Migratory forms use countershaded silvery colours. On their bellies, they often display photophore

A photophore is a specialized anatomical structure found in a variety of organisms that emits light through the process of boluminescence. This light may be produced endogenously by the organism itself (symbiotic) or generated through a mut ...

s producing low grade light. For a predator from below, looking upwards, this bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms. Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorgani ...

camouflages the silhouette of the fish. However, some of these predators have yellow lenses that filter the (red deficient) ambient light, leaving the bioluminescence visible.

Bathyal

The bathyal zone is the lower section of the midwater zone, and encompasses the depths of . Light does not reach this zone, giving it its nickname "the midnight zone"; due to the lack of light, it is less densely populated than the epipelagic zone, despite being much larger. Fish find it hard to live in this zone, as there is crushing pressure, cold temperatures of , a low level of

The bathyal zone is the lower section of the midwater zone, and encompasses the depths of . Light does not reach this zone, giving it its nickname "the midnight zone"; due to the lack of light, it is less densely populated than the epipelagic zone, despite being much larger. Fish find it hard to live in this zone, as there is crushing pressure, cold temperatures of , a low level of dissolved oxygen

Oxygen saturation (symbol SO2) is a relative measure of the concentration of oxygen that is dissolved or carried in a given medium as a proportion of the maximal concentration that can be dissolved in that medium at the given temperature. It can ...

, and a lack of sufficient nutrients. What little energy is available in the bathypelagic zone filters from above in the form of detritus, faecal material, and the occasional invertebrate or mesopelagic fish. About 20% of the food that has its origins in the epipelagic zone falls down to the mesopelagic zone, but only about 5% filters down to the bathypelagic zone. The fish that do live there may have reduced or completely lost their gills, kidneys, hearts, and swimbladders, have slimy instead of scaly skin, and have a weak skeletal and muscular build. This lack of ossification is an adaptation to save energy when food is scarce.

Most of the animals that live in the bathyal zone are invertebrates such as sea sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and are o ...

s, cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s, and echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as ...

s. With the exception of very deep areas of the ocean, the bathyal zone usually reaches the benthic zone on the seafloor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

.

Abyssal and hadal

The abyssal zone remains in perpetual darkness at a depth of . The only organisms that inhabit this zone are

The abyssal zone remains in perpetual darkness at a depth of . The only organisms that inhabit this zone are chemotroph

A chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic ( chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic ( chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phot ...

s and predators that can withstand immense pressures, sometimes as high as . The hadal zone (named after Hades

Hades (; , , later ), in the ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the Greek underworld, underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea ...

, the Greek god

In ancient Greece, deities were regarded as immortal, anthropomorphic, and powerful. They were conceived of as individual persons, rather than abstract concepts or notions, and were described as being similar to humans in appearance, albeit larg ...

of the underworld) is a zone designated for the deepest trenches

A trench is a type of excavation or depression in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a swale or a bar ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches res ...

in the world, reaching depths of below . The deepest point in the hadal zone is the Marianas Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maximum known ...

, which descends to and has a pressure of .

Energy sources

Marine snow

The upper photic zone of the ocean is filled withparticulate organic matter

Particulate organic matter (POM) is a fraction of total organic matter operationally defined as that which does not pass through a filter pore size that typically ranges in size from 0.053 millimeters (53 μm) to 2 millimeters.

Particulate org ...

(POM), especially in the coastal areas and the upwelling areas. However, most POM is small and light. It may take hundreds, or even thousands of years for these particles to settle through the water column into the deep ocean. This time delay is long enough for the particles to be remineralized and taken up by organisms in the food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

.

In the deep Sargasso Sea

The Sargasso Sea () is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre. Unlike all other regions called seas, it is the only one without land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Oc ...

, scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it i ...

(WHOI) found what became known as marine snow

In the deep ocean, marine snow (also known as "ocean dandruff") is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to ...

in which the POM are repackaged into much larger particles which sink at much greater speed, falling like snow.

Because of the sparsity of food, the organisms living on and in the bottom are generally opportunistic. They have special adaptations for this extreme environment: rapid growth, effect larval dispersal mechanism and the ability to use a 'transient' food resource. One typical example is wood-boring bivalves

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

, which bore into wood and other plant remains and are fed on the organic matter from the remains.

Occasional surface blooms

Sometimes sudden access to nutrients near the surface leads to blooms of plankton, algae or animals such assalp

A salp (: salps, also known colloquially as “sea grape”) or salpa (: salpae or salpas) is a barrel-shaped, Plankton, planktonic tunicate in the family Salpidae. The salp moves by contracting its gelatinous body in order to pump water thro ...

s, which becomes so numerous that they will sink all the way to the bottom without being consumed by other organisms. These short bursts of nutrients reaching the seafloor can exceed years of marine snow, and are rapidly consumed by animals and microbes. The waste products becomes part of the deep-sea sediments, and recycled by animals and microbes that feed on mud for years to come.

Whale falls

For the deep-sea ecosystem, the death of awhale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

is the most important event. A dead whale can bring hundreds of tons of organic matter to the bottom. Whale fall

A whale fall occurs when the Carrion, carcass of a whale has fallen onto the ocean floor, typically at a depth greater than , putting them in the Bathyal zone, bathyal or abyssal zones. On the sea floor, these carcasses can create complex local ...

community progresses through three stages:

# Mobile scavenger stage: Big and mobile deep-sea animals arrive at the site almost immediately after whales fall on the bottom. Amphipods

Amphipoda () is an order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphip ...

, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s, sleeper shark

The Somniosidae are a family of sharks in the order Squaliformes, commonly known as sleeper sharks. The common name "''sleeper shark''" comes from their slow swimming, low activity level, and perceived non-aggressive nature.

Distribution and hab ...

s and hagfish

Hagfish, of the Class (biology), class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and Order (biology), order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped Agnatha, jawless fish (occasionally called slime eels). Hagfish are the only known living Animal, animals that h ...

are all scavengers.

# Opportunistic stage: Organisms arrive which colonize the bones and surrounding sediments that have been contaminated with organic matter from the carcass and any other tissue left by the scavengers. One genus is ''Osedax

''Osedax'' is a genus of deep-sea siboglinid polychaetes, commonly called boneworms, zombie worms, or bone-eating worms. ''Osedax'' is Latin for "bone-eater". The name alludes to how the worms bore into the bones of whale carcasses to reach en ...

'', a tube worm. The larva is born without sex. The surrounding environment determines the sex of the larva. When a larva settles on a whale bone, it turns into a female; when a larva settles on or in a female, it turns into a dwarf male. One female ''Osedax'' can carry more than 200 of these male individuals in its oviduct.

# Sulfophilic stage: Further decomposition of bones and seawater sulfate reduction happen at this stage. Bacteria create a sulphide-rich environment analogous to hydrothermal vents. Polynoids, bivalves, gastropods

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and from the land. Ther ...

and other sulphur-loving creatures move in.

Chemosynthesis

Hydrothermal vents

Hydrothermal vents

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hots ...

were discovered in 1977 by scientists from Scripps Institution of Oceanography. So far, the discovered hydrothermal vents are all located at the boundaries of plates: East Pacific, California, Mid-Atlantic ridge, China and Japan.

New ocean basin material is being made in regions such as the Mid-Atlantic ridge as tectonic plates pull away from each other. The rate of spreading of plates is 1–5 cm/yr. Cold sea water circulates down through cracks between two plates and heats up as it passes through hot rock. Minerals and sulfides are dissolved into the water during the interaction with rock. Eventually, the hot solutions emanate from an active sub-seafloor rift, creating a hydrothermal vent.

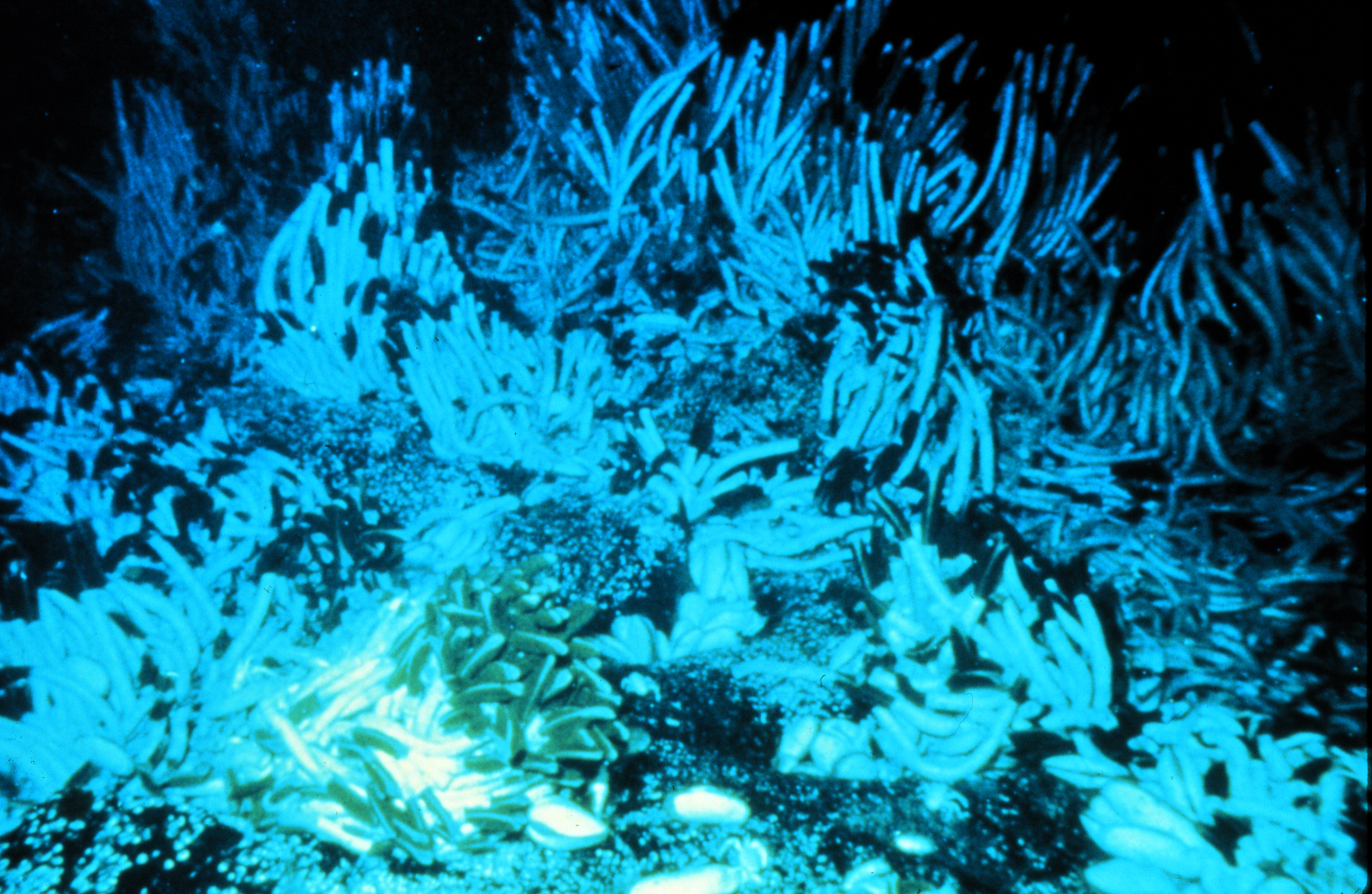

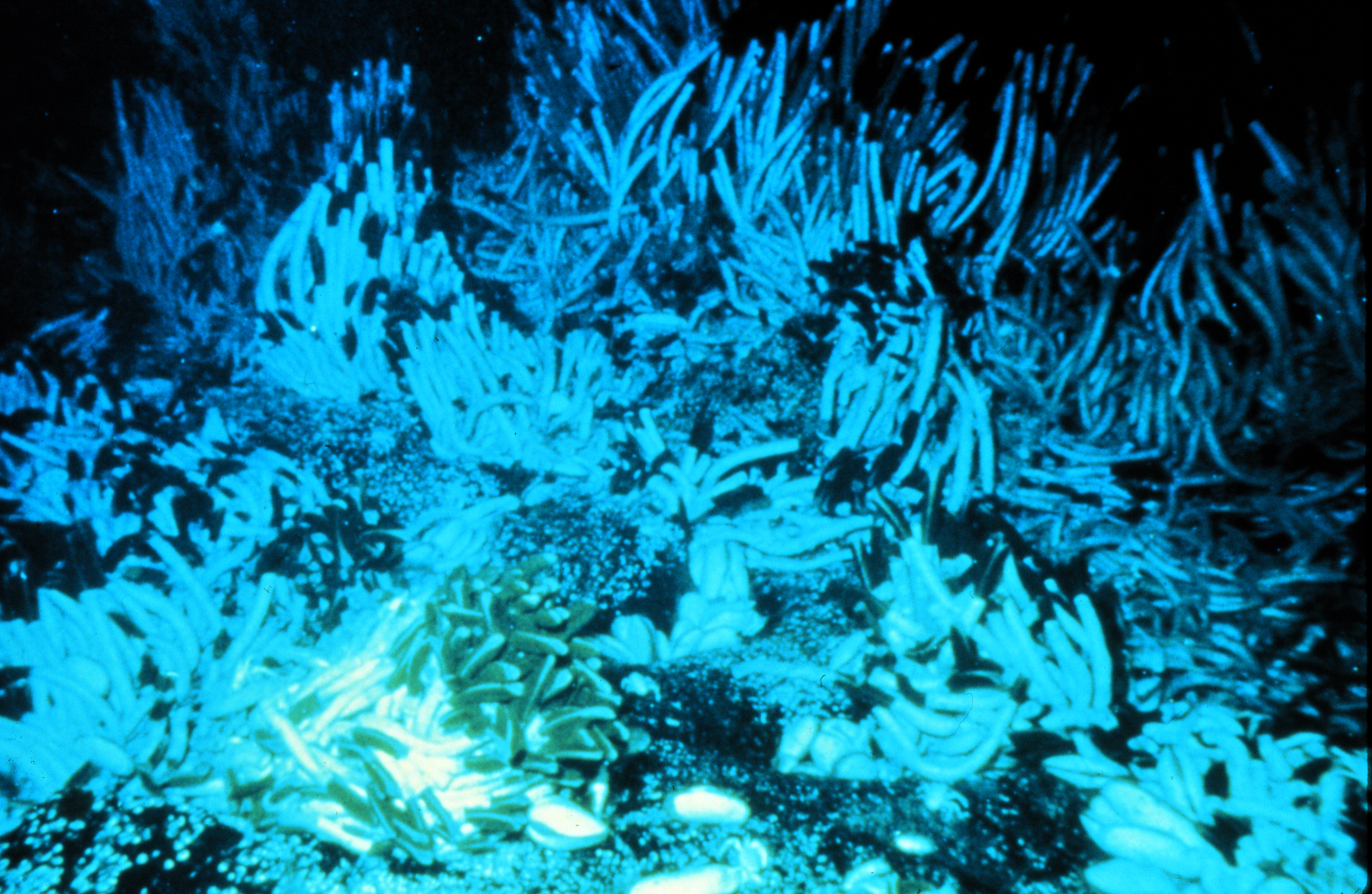

Chemosynthesis of bacteria provide the energy and organic matter for the whole food web in vent ecosystems. These vents spew forth very large amounts of chemicals, which these bacteria can transform into energy. These bacteria can also grow free of a host and create mats of bacteria on the sea floor around hydrothermal vents, where they serve as food for other creatures. Bacteria are a key energy source in the food chain. This source of energy creates large populations in areas around hydrothermal vents, which provides scientists with an easy stop for research. Organisms can also use chemosynthesis to attract prey or to attract a mate.

Giant tube worm

''Riftia pachyptila'', commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the giant beardworm, is a marine invertebrate in the phylum Annelida (formerly grouped in phylum Pogonophora and Vestimentifera) related to tube worms ...

s can grow to tall because of the richness of nutrients. Over 300 new species have been discovered at hydrothermal vents.

Hydrothermal vents are entire ecosystems independent from sunlight, and may be the first evidence that the earth can support life without the sun.

Cold seeps

Acold seep

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where seepage of fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other hydrocarbons occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. ''Cold'' does not mean that the temperature ...

(sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

where hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

, methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

and other hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

-rich fluid seepage occurs, often in the form of a brine pool.

Ecology

Deep sea

Deep sea food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

s are complex, and aspects of the system are poorly understood. Typically, predator-prey interactions within the deep are compiled by direct observation (likely from remotely operated underwater vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROUV) or remotely operated vehicle (ROV) is a free-swimming submersible craft used to perform underwater observation, inspection and physical tasks such as valve operations, hydraulic functions and other g ...

s), analysis of stomach contents, and biochemical analysis. Stomach content analysis is the most common method used, but it is not reliable for some species.

In deep sea pelagic ecosystems off of California, the trophic web is dominated by deep sea fishes, cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s, gelatinous zooplankton

Gelatinous zooplankton are fragile animals that live in the water column in the ocean. Their delicate bodies have no hard parts and are easily damaged or destroyed. Gelatinous zooplankton are often transparent. All jellyfish are gelatinous zoopla ...

, and crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s. Between 1991 and 2016, 242 unique feeding relationships between 166 species of predators and prey demonstrated that gelatinous zooplankton have an ecological impact similar to that of large fishes and squid. Narcomedusae

Narcomedusae is an order (biology), order of hydrozoans in the subclass Trachylinae. Members of this order do not normally have a polyp (zoology), polyp stage. The Medusa (biology), medusa has a dome-shaped bell with thin sides. The tentacles ar ...

, siphonophore

Siphonophorae (from Ancient Greek σίφων (siphōn), meaning "tube" and -φόρος (-phóros), meaning "bearing") is an order within Hydrozoa, a class of marine organisms within the phylum Cnidaria. According to the World Register of Marine ...

s (of the family Physonectae

Physonectae is a suborder of siphonophores.

Organisms in the suborder Physonectae follow the classic Siphonophorae, Siphonophore body plan. They are almost all pelagic, and are composed of a colony of specialized zooids that originate from the ...

), ctenophore

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they ar ...

s, and cephalopods consumed the greatest diversity of prey, in decreasing order. Cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

has been documented in squid of the genus '' Gonatus''.

Deep sea mining

Deep sea mining is the extraction of minerals from the seabed of the deep sea. The main ores of commercial interest are polymetallic nodules, which are found at depths of primarily on the abyssal plain. The Clarion–Clipperton zone (CCZ) a ...

has severe consequences for ocean ecosystems. The destruction of habitats, disturbance of sediment layers, and noise pollution threaten marine species. Essential biodiversity can be lost, with unpredictable effects on the food chain. Additionally, toxic metals and chemicals can be released, leading to long-term pollution of seawater. This raises questions about the sustainability and environmental costs of such activities.

Deep sea research

Humans have explored less than 4% of the ocean floor, and dozens of new species of deep sea creatures are discovered with every dive. The submarineDSV Alvin

''Alvin'' (DSV-2) is a crewed deep-ocean research submersible owned by the United States Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) of Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The original vehicle was built by General Mills' Electr ...

—owned by the US Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it i ...

(WHOI) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Woods Hole is a census-designated place in the town of Falmouth in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. It lies at the extreme southwestern corner of Cape Cod, near Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. The population was 78 ...

—exemplifies the type of craft used to explore deep water. This 16 ton submarine can withstand extreme pressure and is easily manoeuvrable despite its weight and size.

The extreme difference in pressure between the sea floor and the surface makes creatures' survival on the surface near impossible; this makes in-depth research difficult because most useful information can only be found while the creatures are alive. Recent developments have allowed scientists to look at these creatures more closely, and for a longer time. Marine biologist Jeffery Drazen has explored a solution: a pressurized fish trap. This captures a deep-water creature, and adjusts its internal pressure slowly to surface level as the creature is brought to the surface, in the hope that the creature can adjust.New Trap May Take Deep-Sea Fish Safely Out of the Dark/ref> Another scientific team, from the

Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie

Pierre and Marie Curie University ( , UPMC), also known as Paris VI, was a public research university in Paris, France, from 1971 to 2017. The university was located on the Jussieu Campus in the Latin Quarter of the 5th arrondissement of Paris, ...

, has developed a capture device known as the PERISCOP

The PERISCOP is a pressurized recovery device designed for retrieving deep-sea marine life at depths exceeding 2,000 metres. The device was designed by Bruce Shillito and Gerard Hamel at the Universite Pierre et Marie Curie. The name is an acronym ...

, which maintains water pressure as it surfaces, thus keeping the samples in a pressurized environment during the ascent. This permits close study on the surface without any pressure disturbances affecting the sample.

See also

*Deep sea fish

Deep-sea fish are fish that live in the darkness below the sunlit surface waters, that is below the epipelagic or photic zone of the sea. The lanternfish is, by far, the most common deep-sea fish. Other deep-sea fishes include the flashlight f ...

* Movile Cave

Movile Cave () is a cave near Mangalia, Constanța County, Romania discovered in 1986 by Cristian Lascu during construction work a few kilometers from the Black Sea coast. It is notable for its unique subterranean groundwater ecosystem abund ...

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Deep Sea Communities Oceanography