Death March (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A death march is a forced

A death march is a forced

Forced marches were utilized against slaves who were bought or captured by slave traders in

Forced marches were utilized against slaves who were bought or captured by slave traders in

As part of Native American removal in the United States, approximately 6,000

As part of Native American removal in the United States, approximately 6,000

During the

During the

A death march is a forced

A death march is a forced march

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March. The March equinox on the 20 or 2 ...

of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

, other captives, or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinct from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

requires that prisoners must be moved away from a danger zone such as an advancing front line, to a place that may be considered more secure. It is not required to evacuate prisoners who are too unwell or injured to move. In times of war, such evacuations can be difficult to carry out.

Death marches usually feature harsh physical labor and abuse, neglect of prisoner injury and illness, deliberate starvation and dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild deh ...

, humiliation

Humiliation is the abasement of pride, which creates mortification or leads to a state of being Humility, humbled or reduced to lowliness or submission. It is an emotion felt by a person whose social status, either by force or willingly, has ...

, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

, and execution of those unable to keep up the marching pace. The march may end at a prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as Prisoner of war, prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, inte ...

or internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

, or it may continue until all those who are forced to march are dead.

Notable death marches

Jingkang incident

In 1127, during the Jin–Song wars, the forces of the Jurchen-ledJin dynasty

Jin may refer to:

States Jìn 晉

* Jin (Chinese state) (晉國), major state of the Zhou dynasty, existing from the 11th century BC to 376 BC

* Jin dynasty (266–420) (晉朝), also known as Liang Jin and Sima Jin

* Jin (Later Tang precursor) ...

besieged and sacked the Imperial palaces in Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng

Kaifeng ( zh, s=开封, p=Kāifēng) is a prefecture-level city in east-Zhongyuan, central Henan province, China. It is one of the Historical capitals of China, Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and ...

), the capital of the Han-led Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

. The Jin forces captured the Song ruler, Emperor Qinzong

Emperor Qinzong of Song (23 May 1100 – 14 June 1161), personal name Zhao Huan, was the ninth emperor of the Song dynasty of China and the last emperor of the Northern Song dynasty.

Emperor Qinzong was the eldest son and heir apparent of Empe ...

, along with his father, the retired

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one's active working life. A person may also semi-retire by reducing work hours or workload.

Many people choose to retire when they are elderly or incapable of doing their j ...

Emperor Huizong Huizong are different temple names used for emperors of China. It may refer to:

* Wang Yanjun (died 935, reigned 928–935), emperor of the Min dynasty

* Emperor Huizong of Western Xia (1060–1086, reigned 1067–1086), emperor of Western Xia

*Emp ...

, as well as many members of the imperial family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarch, monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or emperor, empress, and the term papal family describes the family of ...

and officials of the Song imperial court. According to '' The Accounts of Jingkang'', Jin troops looted the imperial library and palace. Jin troops also abducted all the female servants and imperial musicians. The imperial family was abducted and their residences were looted. Facing the prospect of captivity and enslavement by the Jurchens, numerous palace women chose to take their own lives. The remaining captives, over 14,000 people, were forced to march alongside the seized assets towards the Jin capital. Their entourage – almost all the ministers and generals of the Northern Song dynasty – suffered from illness, dehydration, and exhaustion, and many never made it. Upon arrival, each person had to go through a ritual where the person had to be naked and wearing only sheep skins.

African slave trade

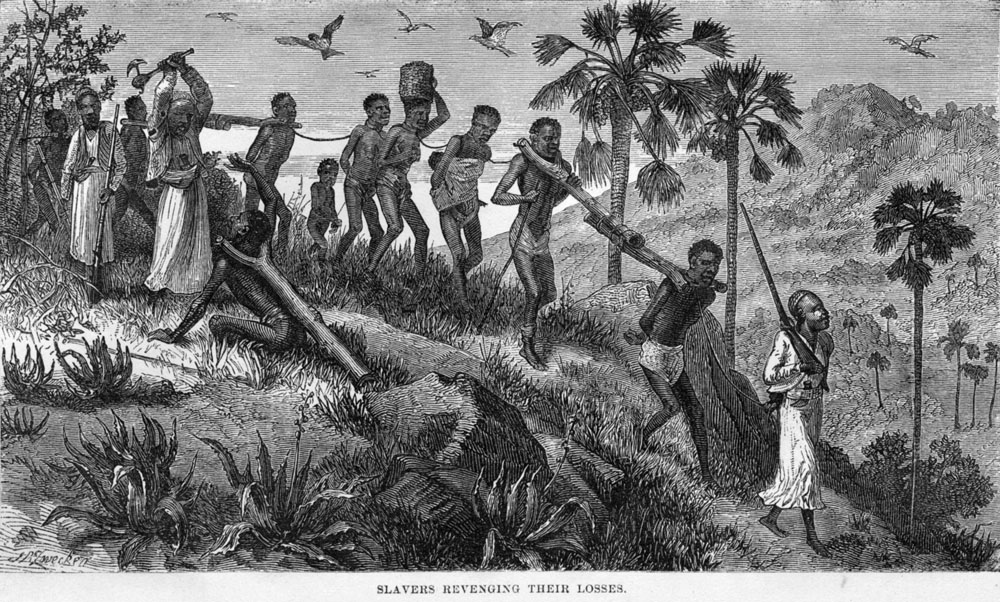

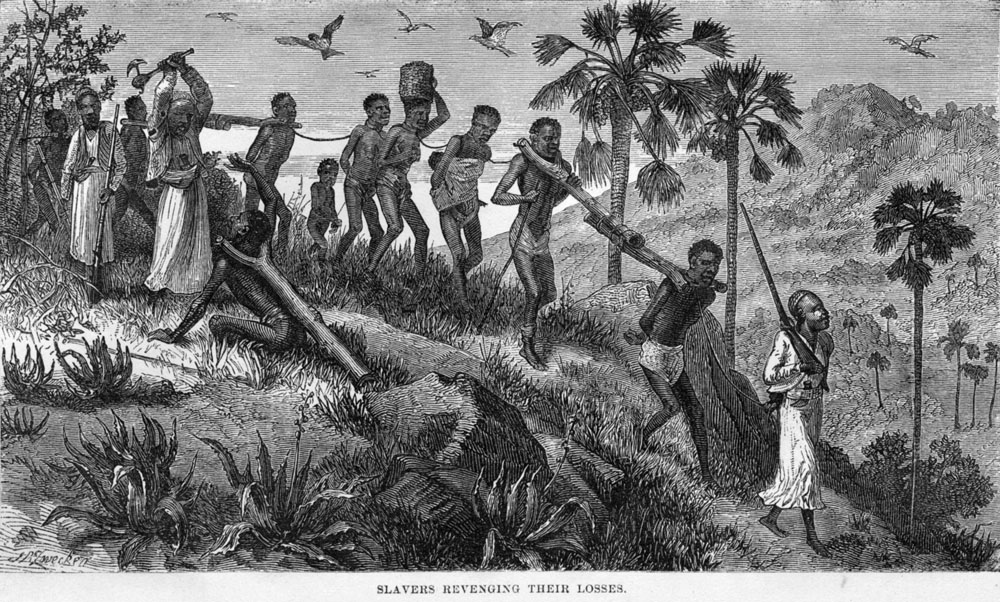

Forced marches were utilized against slaves who were bought or captured by slave traders in

Forced marches were utilized against slaves who were bought or captured by slave traders in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. They were shipped to other lands as part of the East African slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade, involved the capture and transportation of predominately slavery in Africa, sub-Saharan African slaves along the coasts, such as the Swahili Coast and the Horn of Afri ...

with Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

and the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

. Sometimes, the merchants shackled the slaves and provided insufficient food. Slaves who became too weak to walk were frequently killed or left to die.

David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

wrote of the East African slave trade:

Forced displacement of Native Americans

As part of Native American removal in the United States, approximately 6,000

As part of Native American removal in the United States, approximately 6,000 Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

were forced to leave Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

and move to the newly forming Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

(modern-day Oklahoma) in 1831. Only about 4,000 Choctaw arrived in 1832. In 1836, after the Creek War

The Creek War (also the Red Stick War or the Creek Civil War) was a regional conflict between opposing Native American factions, European powers, and the United States during the early 19th century. The Creek War began as a conflict within th ...

, the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

deported 2,500 Muskogee from Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

in chains as prisoners of war. The rest of the tribe (12,000) followed, deported by the Army. Upon arrival to Indian Territory, 3,500 died of infection. In 1838, the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation ( or ) is the largest of three list of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized tribes of Cherokees in the United States. It includes people descended from members of the Cherokee Nation (1794–1907), Old Cheroke ...

was forced by order of President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

to march westward towards Indian Territory. This march became known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

. An estimated 4,000 men, women, and children died during relocation. When the Round Valley Indian Reservation

Round or rounds may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Having no sharp corners, as an ellipse, circle, or sphere

* Rounding, reducing the number of significant figures in a number

* Round number, ending with one or more zeroes

* Round (crypto ...

was established, the Yuki people

The Yuki (also known as Yukiah) are an Indigenous people of California who were traditionally divided into three groups: ''Ukomno'om'' ("Valley People", or Yuki proper), ''Huchnom'' ("Outside the Valley"), and ''Ukohtontilka'' or ''Ukosontilka'' ...

(as they came to be called) of Round Valley were forced into a difficult and unusual situation. Their traditional homeland was not completely taken over by settlers as in other parts of California. Instead, a small part of it was reserved especially for their use as well as the use of other Indians, many of whom were enemies of the Yuki. The Yuki had to share their home with strangers who spoke other languages, lived with other beliefs, and used the land and its products differently. Indians came to Round Valley as they did to other reservations– by force. The word "drive," widely used at the time, is descriptive of the practice of "rounding up" Indians and "driving" them like cattle to the reservation where they were "corralled" by high picket fences. Such drives took place in all weathers and seasons, and the elderly and sick often did not survive. During the Long Walk of the Navajo

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (), was the deportation and ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government and the United States A ...

in August 1863, all Konkow Maidu were to be sent to the Bidwell Ranch in Chico and then be taken to the Round Valley Reservation

The Round Valley Indian Tribe, originally known as the Covelo Indian Community, is a federally recognized confederation of Native American tribes. These include the Yuki, Wailaki, Concow (or Konkow), Little Lake and other Pomo, Nomlaki, and Pit R ...

at Covelo in Mendocino County. Any Indians remaining in the area were to be shot. Maidu were rounded up and marched under guard west out of the Sacramento Valley and through to the Coastal Range. 461 Native Americans started the trek, 277 finished. They reached Round Valley on 18 September 1863. After the Yavapai Wars

The Yavapai Wars, or the Tonto Wars, were a series of armed conflicts between the Yavapai and Tonto tribes against the United States in the Arizona Territory. The period began no later than 1861, with the arrival of American settlers on Yavapai ...

, 375 Yavapai

The Yavapai ( ) are a Native American tribe in Arizona. Their Yavapai language belongs to the Upland Yuman branch of the proposed Hokan language family.

Today Yavapai people are enrolled in the following federally recognized tribes:

* Fort ...

perished during deportations out of 1,400 remaining Yavapai.

Congo Free State

King Leopold II

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Le ...

sanctioned the creation of "child colonies" in his Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

which had orphaned Congolese kidnapped and sent to schools operated by Catholic missionaries in which they would learn to work or be soldiers; these were the only schools funded by the state. More than 50% of the children sent to the schools died of disease, and thousands more died in the forced marches into the colonies. In one such march, 108 boys were sent over to a mission school and only 62 survived, eight of whom died a week later.

Dungan Revolt (1862–1877)

During theDungan Revolt (1862–1877)

The Dungan Revolt (1862–1877), also known as the Tongzhi Hui Revolt (, Xiao'erjing: تُجِ خُوِ لُوًا, ) or Hui (Muslim) Minorities War, was a war fought in 19th-century western China, mostly during the reign of the Tongzhi Emp ...

, 700,000 to 800,000 Hui Muslims

The Hui people are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the northwestern provinces and in the Zhongyuan region. According to the 2 ...

from Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

were deported to Gansu

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

in China, in a process in which most were killed along the way from thirst, starvation, and massacres by the militia escorting them, with only a few thousand surviving.

Armenian Genocide

TheArmenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

resulted in the death of up to 1,500,000 people from 1915 to 1918. Under the cover of World WarI, the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

sought to cleanse Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

of its Armenian population. As a result, much of the Armenian population was exiled from large parts of Western Armenia

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, ''Arevmdian Hayasdan'') is a term to refer to the western parts of the Armenian highlands located within Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that comprise the historic ...

and forced to march to the Syrian desert. Many were rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

d, tortured, and killed on their way to the 25 concentration camps set up in the Syrian desert. The most infamous camps were the Deir ez-Zor camps, where an estimated 150,000 Armenians were killed.

World War I

Grand Duke Nicolas, who was still commander-in-chief of the Western forces, after suffering serious defeats at the hands of the German army, decided to implement the decrees for the German Russians living under his army's control, principally in theVolhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

province. The lands were to be expropriated, and the owners deported to Siberia. The land was to be given to Russian war veterans once the war was over. In July 1915, without prior warning, 150,000 German settlers from Volhynia were arrested and shipped to internal exile in Siberia and Central Asia. (Some sources indicate that the number of deportees reached 200,000). Ukrainian peasants took over their lands. While precise figures remain elusive, estimates suggest that the mortality rate associated with these deportations ranged from 30% to 50%, translating to a death toll between 63,000 and 100,000 individuals.

In the eastern part of Russian Turkestan

Russian Turkestan () was a colony of the Russian Empire, located in the western portion of the Central Asian region of Turkestan. Administered as a Krai or Governor-Generalship, it comprised the oasis region to the south of the Kazakh Steppe, b ...

, after the suppression of the Urkun

The Central Asian revolt of 1916, also known as the Semirechye Revolt and as Urkun in Kyrgyzstan, was an anti-Russian uprising by the indigenous inhabitants of Russian Turkestan sparked by the conscription of Muslims into the Russian military ...

uprising against the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

tens of thousands of surviving Kyrgyz and Kazakhs

The Kazakhs (Kazakh language, Kazakh: , , , ) are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia and Eastern Europe. They share a common Culture of Kazakhstan, culture, Kazakh language, language and History of Kazakhstan, history ...

fled toward China. In the Tien-Shan mountains

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

, thousands died in mountain passes over 3,000 meters high.

World War II

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, death marches of POWs occurred in both German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly military occupation, militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the governmen ...

and the Japanese colonial empire

The territorial conquests of the Empire of Japan in the Western Pacific Ocean and East Asia began in 1895 with its victory over Qing China in the First Sino-Japanese War. Subsequent victories over the Russian Empire (Russo-Japanese War) and the ...

. Death marches of those held in Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

were common in the later stages of the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

as Allied forces closed in on the camps. One infamous death march occurred in January 1945, as the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

advanced on German-occupied Poland. Nine days before the Red Army arrived at the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

, the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (; ; SS; also stylised with SS runes as ''ᛋᛋ'') was a major paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II.

It beg ...

'' marched nearly 60,000 prisoners out of the camp towards Wodzisław Śląski

Wodzisław Śląski (; , , , , ) is a city in Silesian Voivodeship, southern Poland with 47,992 inhabitants (2019). It is the seat of Wodzisław County.

It was previously in Katowice Voivodeship (1975–1998); close to the border with the Czech ...

, where they were put on freight trains to other camps. Approximately 15,000 prisoners died on the way. The death marches were judged during the Nuremberg trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

to be a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

. On the Eastern Front, death marches were amongst the forms of German atrocities committed against Soviet prisoners of war

During World War II, Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) held by Nazi Germany and primarily in the custody of the German Army were starved and subjected to deadly conditions. Of nearly six million who were captured, around three million died during ...

.

During the NKVD prisoner massacres

The NKVD prisoner massacres were a series of mass executions of political prisoners carried out by the NKVD, the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union, across Eastern Europe, primarily in Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic states ...

in 1941, NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

personnel led prisoners on death marches to various locations in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

; upon arriving to pre-designated execution sites, the survivors were summarily executed

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

. After the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

in February 1943, numerous German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

Approximately three million German prisoners of war were captured by the Soviet Union during World War II, most of them during the great advances of the Red Army in the last year of the war. The POWs were employed as forced labor in the Soviet ...

were subject to death marches; after enduring a period of captivity near Stalingrad, they were sent by the Soviet authorities on a "death march across the frozen steppe" to labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see British and American spelling differences, spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are unfree labour, forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have ...

s elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

The Brno death march

The Brno death marchRozumět dějinám, Zdeněk Beneš, p. 208 () began late on the night of 30 May 1945 when the ethnic German minority in Brno ( ) was forcibly deported to nearby Austria following the capture of the city by the Allies during Wo ...

during the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a broader series of Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950), evacuations and deportations of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II.

...

occurred in May 1945. The Bleiburg repatriations

The Bleiburg repatriations ( see terminology) were a series of forced repatriations from Allied-occupied Austria of Axis-affiliated individuals to Yugoslavia in May 1945 after the end of World War II in Europe. During World War II, Yugoslav terr ...

also occurred in May 1945 (during the last days of World War II and after), a total of 280,000 Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, were involved in the Independent State of Croatia evacuation to Austria. Mostly Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaša – Croatian Revolutionar ...

and the Croatian Home Guard, but also civilians and refugees, tried to flee the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

and the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, and marched northwards through Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

to Allied-occupied Austria

Austria was occupied by the Allies of World War II, Allies and declared independence from Nazi Germany on 27 April 1945 (confirmed by the Berlin Declaration (1945), Berlin Declaration for Germany on 5 June 1945), as a result of the Vienna offen ...

. However, the British refused to accept their surrender and directed them to surrender to Yugoslav forces, who subjected them to death marches back to Yugoslavia, resulting in the death of 70–80,000 people.

In the Pacific theatre, the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces

The Imperial Japanese Armed Forces (IJAF, full or Nippon-gun () for short, meaning "Japanese Forces") were the unified forces of the Empire of Japan. Formed during the Meiji Restoration in 1868,"One can date the 'restoration' of imperial rul ...

conducted death marches of Allied POWs, including the 1942 Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March was the Death march, forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of around 72,000 to 78,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POWs) from the municipalities of Bagac and Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula to Camp ...

and the 1945 Sandakan Death Marches

The Sandakan Death Marches were a series of forced marches in Borneo from Sandakan to Ranau which resulted in the deaths of 2,434 Allied prisoners of war held captive by the Empire of Japan during the Pacific campaign of World War II at the ...

. The former forcibly transferred 60–80,000 POWs to Balanga, resulting in the deaths of 2,500–10,000 Filipino and 100–650 American POWs, while the latter caused the deaths of 2,345 Australian and British POWs, of which only 6 survived. Lieutenant-General Masaharu Homma

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Homma commanded the Japanese 14th Army, which invaded the Philippines and perpetrated the Bataan Death March. After the war, Homma was convicted of war crimes relating ...

was charged with failure to control his troops in 1945 in connection with the Bataan Death March. Both the Bataan and Sandakan death marches were judged by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on 29 April 1946 to Criminal procedure, try leaders of the Empire of Japan for their cri ...

to be war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s.

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classif ...

refers to the forced transfer of various groups from the 1930s up to the 1950s ordered by Joseph Stalin and may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population (often classified as "enemies of workers"), deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite directions to fill the ethnically cleansed territories. Soviet archives documented 390,000 deaths during kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

forced resettlement

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but they also occur d ...

and up to 400,000 deaths of persons deported to forced settlements in the Soviet Union

Special settlements in the Soviet Union were the result of population transfers and were performed in a series of operations organized according to social class or nationality of the deported. Resettling of "enemy classes" such as prosperous ...

during the 1940s; however Steven Rosefield and Norman Naimark put overall deaths closer to some 1 to 1.5 million perishing as a result of the deportations — of those deaths, the deportation of Crimean Tatars

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars (, Cyrillic: Къырымтатар халкъынынъ сюргюнлиги) or the ('exile') was the ethnic cleansing and the cultural genocide of at least 191,044 Crimean Tatars that was carried out ...

and the deportation of Chechens were recognized as genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

s by Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the two legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it ...

respectively.

Lydda Death March

During the1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, 50,000-70,000 Palestinians

Palestinians () are an Arab ethnonational group native to the Levantine region of Palestine.

*: "Palestine was part of the first wave of conquest following Muhammad's death in 632 CE; Jerusalem fell to the Caliph Umar in 638. The indigenou ...

were expelled from the cities of Lydda

Lod (, ), also known as Lydda () and Lidd (, or ), is a city southeast of Tel Aviv and northwest of Jerusalem in the Central District of Israel. It is situated between the lower Shephelah on the east and the coastal plain on the west. The ci ...

(also spelled Lod) and Ramla

Ramla (), also known as Ramle (, ), is a city in the Central District of Israel. Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with significant numbers of both Jews and Arabs.

The city was founded in the early 8th century CE by the Umayyad caliph S ...

by the Israeli military

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branches: the Israeli Ground Forces, the Israeli Air Force, an ...

. Occurring as a part of the broader 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight

In the 1948 Palestine war, more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs – about half of Mandatory Palestine's predominantly Arab population – fled from their homes or were expelled. Expulsions and attacks against Palestinians were carried out by the ...

and the Nakba

The Nakba () is the ethnic cleansing; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; of Palestinian Arabs through their violent displacement and dispossession of land, property, and belongings, along with the destruction of their s ...

, the operation is widely considered to have been an instance of ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

. Ramla'a residents were expelled by bus, but Lydda's residents had to walk 10–15 miles to meet up with the lines of the Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army, of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of the Jordan, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, an independent state, with a final Ar ...

. Many people died from the heat, thirst, and exhaustion on the journey and the event has come to be known as the Lydda Death March

In July 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war, the Palestinian towns of Lydda (also known as Lod) and Ramle were captured by the Israeli Defense Forces and their residents (totalling 50,000–70,000 people) were violently expelled. The expulsio ...

.

Reports vary regarding how many died. Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref

Aref al-Aref (; 1892–1973) was a Palestinian people, Palestinian journalist, historian and politician. He served as mayor of East Jerusalem in the 1950s during the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank.

Biography Early life

Aref al-Aref was ...

estimated 500 died in the expulsion from Lydda, and that 350 of that number died from thirst and exhaustion. Nur Masalha

Nur ad-Din Masalha (, ; born 4 January 1957) is a Palestinian writer, historian, and academic. His work focuses on the history, politics, and theology of Palestine, including themes such as the Palestinian Nakba, Zionism, and liberation theolog ...

estimated 350 deaths in the "expulsion and forced march" from Lydda. Israeli historian Benny Morris

Benny Morris (; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. Morris was initially associated with the ...

has written that it was a "handful and perhaps dozens." John Bagot Glubb

Lieutenant-General Sir John Bagot Glubb, KCB, CMG, DSO, OBE, MC, KStJ, KPM (16 April 1897 – 17 March 1986), known as Glubb Pasha (; and known as Abu Hunaik by the Jordanians), was a British military officer who led and trained Transj ...

wrote that "nobody will ever know how many children died." Nimr al-Khatib

Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib ( (1918 – 15 November 2010) was a Palestinian leader and pro-Husayni head of the Arab Higher Committee in Haifa during the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine. He founded an Islamic society called ''Jam‘i ...

estimated that 335 people died. Morris calls this number "certainly an exaggeration", while historian Michael Palumbo called Khatib's estimate "a very conservative figure."

Korean War

During the

During the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, in the winter of 1951, 200,000 South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

n National Defense Corps soldiers were forcibly marched by their commanders, with 50,000 to 90,000 soldiers starving to death or dying of disease during the march or in training camps.

This incident is known as the National Defense Corps incident

The National Defense Corps Incident was a death march that occurred between December 1950 and February 1951, during the Korean War, as a result of corruption. The incident refers to both the deaths from starvation during the retreat and the co ...

. During the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, prisoners who were held by the North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

ns underwent what became known as the "Tiger Death March". The march occurred while North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

was being overrun by United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

forces. As North Korean forces retreated to the Yalu River

The Yalu River () or Amnok River () is a river on the border between China and North Korea. Together with the Tumen River to its east, and a small portion of Paektu Mountain, the Yalu forms the border between China and North Korea. Its valle ...

on the border with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, they evacuated their prisoners with them. On 31 October 1950, some 845 prisoners, including about eighty non-combatants, left Manpo

Manpo () is a city of northwestern Chagang Province, North Korea. As of 2008, it had an estimated population of 116,760. It looks across the border to the city of Ji'an, Jilin province, China.

History

Manp'o was incorporated as a city in Octob ...

and went upriver, arriving in Chunggang on 8 November 1950. A year later, fewer than 300 of the prisoners were still alive. The march was named after the brutal North Korean colonel who presided over it, his nickname was "The Tiger". Among the prisoners was George Blake

George Blake ( Behar; 11 November 1922 – 26 December 2020) was a Espionage, spy with Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and worked as a double agent for the Soviet Union. He became a communist and decided to work for the Minist ...

, an MI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

officer who had been stationed in Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

. While he was being held as a prisoner, he became a KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

double agent.

Phnom Penh

The Khmer Rouge marked the beginning of their rule with the forced evacuation of various cities includingPhnom Penh

Phnom Penh is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Cambodia, most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since 1865 and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its political, economic, industr ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

.

See also

*Population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but they also occur d ...

* Forced displacement

Forced displacement (also forced migration or forced relocation) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of perse ...

* List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

* Carolean Death March

The Carolean Death March (), also known as the Catastrophe on Øyfjellet () was the disastrous retreat by a force of Swedish soldiers (known as Caroleans), under the command of Carl Gustaf Armfeldt, across the Tydalen mountain range in Trønd ...

(1718–1719)

* Samsun deportations

The Samsun deportations were a series of death marches orchestrated by the Turkish National Movement as part of its extermination of the Greek community of Samsun, a city in northern Turkey (then still formally the Ottoman Empire), and its environ ...

(1921–1922)

* March of the Living

The March of the Living (, ; ) is an annual educational program which brings students from around the world to Poland, where they explore the remnants of the Holocaust. On Holocaust Memorial Day observed in the Jewish calendar (), thousands of p ...

* Sayfo

The Sayfo (, ), also known as the Seyfo or the Assyrian genocide, was the mass murder and deportation of Assyrian people, Assyrian/Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan (Iran), Azerbaijan province by Ottoman Army ...

(1914–1924)

* Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

During the later stages of World War II and the post-war period, Reichsdeutsche (German citizens) and Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans living outside the Nazi state) fled and were expelled from various Eastern Europe, Eastern and Central European ...

* Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

References

Further reading

*Bibliography of genocide studies

Bibliography (from and ), as a discipline, is traditionally the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology (from ). English author and bibliographer John Carter describes ''bibliograph ...

{{Authority control

War crimes by type

Military marching

Genocide