David Josiah Brewer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

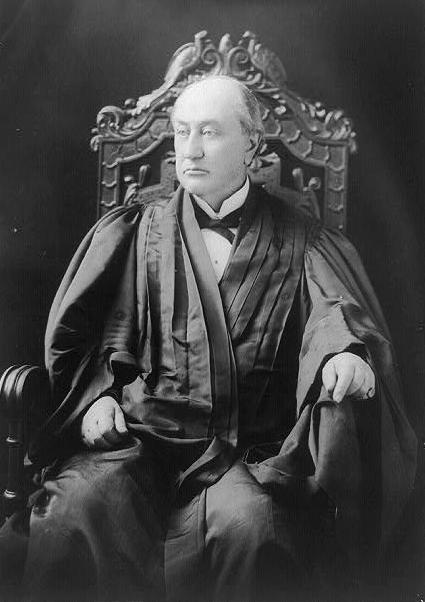

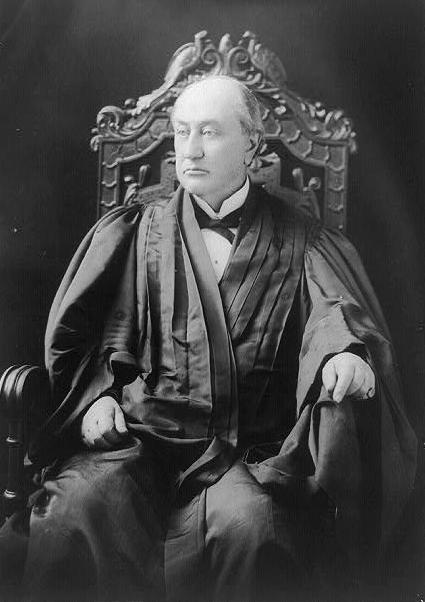

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an

David Josiah Brewer was born on June 20, 1837, in

David Josiah Brewer was born on June 20, 1837, in

Justice

Justice

Brewer joined the majority in the case of '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'', a decision that, according to Brodhead, "contributed much to he Fuller Court'sreputation for favoritism toward corporate and other forms of wealth". ''Pollock'' involved a provision of the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 that levied a two-percent tax on incomes and corporate profits that exceeded $4000 a year. Its challengers took the tax to court, where they argued that it was a

Brewer joined the majority in the case of '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'', a decision that, according to Brodhead, "contributed much to he Fuller Court'sreputation for favoritism toward corporate and other forms of wealth". ''Pollock'' involved a provision of the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 that levied a two-percent tax on incomes and corporate profits that exceeded $4000 a year. Its challengers took the tax to court, where they argued that it was a

One of Brewer's best-known opinions came in '' Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States''. The case arose when the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church hired E. Walpole Warren, a British clergyman, to be the church's rector. The church was fined $1000 for violating the Alien Contract Labor Act of 1885, under which it was "unlawful for any person, company, partnership, or corporation... to prepay the transportation, or in any way assist or encourage the importation or migration of any alien... under contract... to perform labor or service of any kind in the United States". The statute did not exempt members of the clergy, and according to Semonche "the words were clear and the application logically unassailable". Yet in an opinion by Brewer, the Court unanimously reversed the conviction. Writing that "if a literal construction of the words of a statute be absurd, the act must be so construed as to avoid the absurdity", Brewer reasoned that the law was clearly intended to forbid the importation of unskilled laborers rather than ministers. The case's emphasis on Congress's intent over the statute's text marked a turning point in the Court's treatment of

One of Brewer's best-known opinions came in '' Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States''. The case arose when the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church hired E. Walpole Warren, a British clergyman, to be the church's rector. The church was fined $1000 for violating the Alien Contract Labor Act of 1885, under which it was "unlawful for any person, company, partnership, or corporation... to prepay the transportation, or in any way assist or encourage the importation or migration of any alien... under contract... to perform labor or service of any kind in the United States". The statute did not exempt members of the clergy, and according to Semonche "the words were clear and the application logically unassailable". Yet in an opinion by Brewer, the Court unanimously reversed the conviction. Writing that "if a literal construction of the words of a statute be absurd, the act must be so construed as to avoid the absurdity", Brewer reasoned that the law was clearly intended to forbid the importation of unskilled laborers rather than ministers. The case's emphasis on Congress's intent over the statute's text marked a turning point in the Court's treatment of

According to the historian Linda Przybyszewski, Brewer was "probably the most widely read jurist in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century" due to what Justice Holmes characterized as his "itch for public speaking". He spoke prolifically on various issues, often drawing criticism from his colleagues for his frankness. The topic about which he spoke most fervently was peace: in his public addresses he decried imperialism, arms buildups, and the horrors of war. He supported the peaceable resolution of international disputes via

According to the historian Linda Przybyszewski, Brewer was "probably the most widely read jurist in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century" due to what Justice Holmes characterized as his "itch for public speaking". He spoke prolifically on various issues, often drawing criticism from his colleagues for his frankness. The topic about which he spoke most fervently was peace: in his public addresses he decried imperialism, arms buildups, and the horrors of war. He supported the peaceable resolution of international disputes via

Works by David J. Brewer

at

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is a Justice (title), justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the J ...

from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

, he supported states' rights, opposed broad interpretations of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amon ...

, and voted to strike down economic regulations that he felt infringed on the freedom of contract. He and Justice Rufus W. Peckham were the "intellectual leaders" of the Fuller Court

The Fuller Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1888 to 1910, when Melville Fuller served as the eighth Chief Justice of the United States. Fuller succeeded Morrison R. Waite as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and F ...

, according to the legal academic Owen M. Fiss. Brewer has been viewed negatively by most scholars, though a few have argued that his reputation as a reactionary deserves to be reconsidered.

Born in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

(modern-day İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

, Turkey) to Congregationalist missionaries, Brewer attended Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a Private university, private liberal arts college, liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut, United States. It was founded in 1831 as a Men's colleges in the United States, men's college under the Methodi ...

, Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, and Albany Law School

Albany Law School is a private law school in Albany, New York. It was founded in 1851 and is the oldest independent law school in the nation. It is accredited by the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary ...

. He headed west and settled in Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth () is the county seat and largest city of Leavenworth County, Kansas, Leavenworth County, Kansas, United States. Part of the Kansas City metropolitan area, Leavenworth is located on the west bank of the Missouri River, on the site o ...

, where he practiced law. Brewer was elected to a county judgeship in 1862; he later served as judge of Kansas's First Judicial District and as the county attorney for Leavenworth County. In 1870, he was elected to the Kansas Supreme Court

The Kansas Supreme Court is the highest judicial authority in the U.S. state of Kansas. Composed of seven justices, led by Chief Justice Marla Luckert, the court supervises the legal profession, administers the judicial branch, and serves as t ...

, where he served for fourteen years, participating in decisions on segregation, property rights, women's rights, and other issues. President Chester A. Arthur appointed him as a federal circuit judge in 1884. When Justice Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English Association football, footballer who played as an Forward (association football)#Outside forward, outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the Br ...

of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

died in 1889, President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

nominated Brewer to succeed him. Despite some objections from prohibitionists, the U.S. Senate voted 53–11 to confirm Brewer, and he took the oath of office on January 6, 1890.

Brewer opposed governmental interference in the free market and rejected the Supreme Court's decision in '' Munn v. Illinois'' (1877), which had upheld the states' power to regulate businesses, writing: "The paternal theory of government is to me odious." He joined the majority in decisions such as ''Lochner v. New York

''Lochner v. New York'', 198 U.S. 45 (1905), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court holding that a New York (state), New York State statute th ...

'' (1905), in which the Court invoked the doctrine of substantive due process

due process is a principle in United States constitutional law that allows courts to establish and protect substantive laws and certain fundamental rights from government interference, even if they are unenumerated elsewhere in the U.S. Consti ...

to strike down a New York labor law. Brewer was not uniformly hostile to regulations, however; his majority opinion in ''Muller v. Oregon

''Muller v. Oregon'', 208 U.S. 412 (1908), was a list of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court. Women were permitted by state mandate fewer working h ...

'' (1908) sustained an Oregon law that set maximum working hours for female laborers. He joined the majority to strike down the federal income tax in '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'' (1895), and, writing for the Court in the case of ''In re Debs

''In re Debs'', 158 U.S. 564 (1895), was a labor law case of the United States Supreme Court, which upheld a contempt of court conviction against Eugene V. Debs. Debs had the American Railway Union continue its 1894 Pullman Strike in violatio ...

'' (1895), he expanded the judiciary's equitable authority by upholding an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

against the organizers of a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

. He favored a narrow interpretation of the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce and consequently prohibits unfair monopolies. It was passed by Congress and is named for S ...

in '' United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'' (1895), but he cast the deciding vote in '' Northern Securities Co. v. United States'' (1904) to block a corporate merger on antitrust grounds.

Brewer generally ruled against African-Americans in civil rights cases, although he consistently voted in favor of Chinese immigrants. He opposed imperialism and, in the Insular Cases, rejected the idea that the Constitution did not apply in full to the territories. His majority opinion in '' Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States'' (1892) contained a frequently criticized claim that the United States "is a Christian nation". Off the bench, he was a prolific public speaker who decried Progressive reforms and criticized President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. He advocated for peace and served on an arbitral commission that resolved a boundary dispute between Venezuela and the United Kingdom. He remained on the Supreme Court until his death in 1910.

Early life

David Josiah Brewer was born on June 20, 1837, in

David Josiah Brewer was born on June 20, 1837, in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

(modern-day İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

, Turkey), which was at the time a part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. He was the fourth child of Josiah Brewer, a Massachusetts-born Congregationalist missionary to the Mediterranean, and his wife Emilia A. Field, a member of the prominent Field family whose brothers included David Dudley Field (a well-known attorney), Stephen J. Field (a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), Cyrus W. Field (who developed the trans-Atlantic cable), and Henry M. Field (a clergyman). The family returned to the United States in 1838; the elder Brewer pastored several congregations in New England and served as the chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

of a Connecticut state penitentiary.

When Brewer was fifteen years old, he enrolled at Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a Private university, private liberal arts college, liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut, United States. It was founded in 1831 as a Men's colleges in the United States, men's college under the Methodi ...

in Connecticut. At Wesleyan, he joined the Peithologian literary society and a group known as the Mystical Seven. Brewer transferred to Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

two years later; he took classes in political philosophy, the U.S. Constitution, Hebrew, mathematics, theology, and other topics. His classmates included Henry Billings Brown, who later served with him on the Supreme Court, and Chauncey Depew, a future senator. Brewer expressed interest in politics during his college years, and he wrote numerous forceful letters to the editor

A letter to the editor (LTE) is a letter sent to a publication about an issue of concern to the reader. Usually, such letters are intended for publication. In many publications, letters to the editor may be sent either through conventional mai ...

, including a fiery denunciation of the Supreme Court's ''Dred Scott'' decision. One Yale classmate recalled that the future justice had a reputation for "jumping up on the slightest provocation to make a speech, especially on political lines". Brewer graduated from Yale in 1856, receiving an A.B. degree with honors.

Upon his graduation, Brewer moved to New York City, where he read law

Reading law was the primary method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship un ...

in the office of his uncle David Dudley Field. After a year, he enrolled at Albany Law School

Albany Law School is a private law school in Albany, New York. It was founded in 1851 and is the oldest independent law school in the nation. It is accredited by the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary ...

, from which he received an LL.B. degree in 1858. Brewer pondered whether to remain in New York with his uncle David or to move to California to work with his uncle Stephen, but he eventually rejected both options, declaring: "I don't want to grow up to be my uncle's nephew." He moved to Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City, Missouri, abbreviated KC or KCMO, is the largest city in the U.S. state of Missouri by List of cities in Missouri, population and area. The city lies within Jackson County, Missouri, Jackson, Clay County, Missouri, Clay, and Pl ...

; after practicing law there for a few months, he joined the Pike's Peak gold rush and headed west in search of fortune. Having found no gold, he settled in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, a city of about ten thousand that was both a center of regional commerce and the home of several notable figures in Kansas's legal community.

Career

After a short period of work at a law firm in Leavenworth, Brewer began a legal practice of his own with a partner. In 1861, he was appointed commissioner of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Kansas, an administrative position in which he issued warrants and completed paperwork. He continued to practice law, and he served as a second lieutenant in the "Lane Rifles," a UnionHome Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting ...

, during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. In 1862, after unsuccessfully seeking the Republican nomination for a seat in the state legislature, he hesitantly accepted a nomination to be the party's candidate for judge of Leavenworth County's criminal and probate courts. Although he was only twenty-five years old, he won the election. As a judge, Brewer punished criminals harshly; despite his inexperience, he quickly gained a reputation as a competent jurist. Having been urged by several local attorneys to run, Brewer sought and won election in 1864 as judge of the First Judicial District of Kansas, which encompassed Leavenworth and Wyandotte counties. In that position, he held a general in contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

and ruled that a man who was one-quarter black had the right to vote. Brewer was elected county attorney in 1868, serving until 1870; he also resumed the private practice of law.

Kansas Supreme Court (1870–1884)

In 1870, the state's Republicans unexpectedly nominated Brewer instead of incumbent Justice Jacob Safford for a seat on theKansas Supreme Court

The Kansas Supreme Court is the highest judicial authority in the U.S. state of Kansas. Composed of seven justices, led by Chief Justice Marla Luckert, the court supervises the legal profession, administers the judicial branch, and serves as t ...

. In the heavily Republican state, Brewer won the general election handily; he was easily reelected in 1876 and 1882. According to Brian J. Moline, his opinions on the state Supreme Court, "while well within the conventions of the time, exhibit an individualistic, even progressive, instinct". In a landmark women's rights decision in ''Wright v. Noell'', he ruled in favor of a woman who had been elected to serve as county superintendent of public instruction, reversing a lower court's holding that she was ineligible to serve. Brewer rendered rulings that were sympathetic to Native Americans, and he emphasized the best interests of the child

Best interests or best interests of the child is a child rights principle, which derives from Article 3 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which says that "in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private ...

in child custody cases.

In ''Board of Education v. Tinnon'', Brewer dissented when the court held that the city of Ottawa, Kansas

Ottawa (pronounced ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Franklin County, Kansas, Franklin County, Kansas, United States. It is located on both banks of the Marais des Cygnes River near the center of Franklin County. As of the 2020 United ...

, could not lawfully segregate its schools. Justice Daniel M. Valentine's opinion for a 2–1 majority concluded that local school boards had no authority beyond the powers expressly given to them by state law; since state law did not expressly authorize school boards to create separate schools for blacks and whites, he determined that segregation in Ottawa was not permissible. In what the law professor Andrew Kull characterized as an "angry dissent", Brewer disagreed. He maintained that school boards could act without explicit authorization from the legislature, and he also argued that racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, writing that "each State has the power to classify school children by color, sex, or otherwise, as to its legislature shall seem wisest and best". In his biography of Brewer, the historian Michael J. Brodhead maintained that the justice's reasoning was "not overtly racist" and rested instead on his longstanding support for local self-governance; the legal scholar Arnold M. Paul, by contrast, argued that the opinion exhibited "an insensitivity to social problems... combined with a simplistic legal formalism".

According to Paul, cases in the 1880s involving Kansas's prohibition of alcohol

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

"mark the decisive turning points in Brewer's shift to hard-line conservatism". In ''State v. Mugler'', a brewer challenged a state law that forbade the manufacture of beer, arguing that it deprived him of his property without due process of law

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

. The court ruled against him on the basis that the law fell within the state's police power. Although Brewer did not formally dissent, he expressed his reservations about the majority's conclusions, suggesting that the law in effect deprived the brewer of his property without just compensation

Just compensation is a right enshrined in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (and counterpart state constitutions), which is invoked whenever private property is taken by the government. Under some state constitutions, it is also owed ...

. (Mugler appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but in '' Mugler v. Kansas'', it ruled that the prohibition law was constitutional.) Brewer's opinion in ''Mugler'' presaged the protective attitude toward property rights that he later displayed on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Eighth Circuit (1884–1889)

When Judge John F. Dillon resigned in 1879, several state officials encouraged President Rutherford B. Hayes to nominate Brewer to the ensuing vacancy on the federalcircuit court

Circuit courts are court systems in several common law jurisdictions. It may refer to:

* Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region or country to different towns or cities where they will hear cases;

* Courts that s ...

for the Eighth Circuit. George W. McCrary was appointed instead, but when McCrary resigned in 1884, President Chester A. Arthur nominated Brewer to take his place. Brewer characterized the Eighth Circuit as "an empire in itself": it encompassed Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska, to which North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming were added several years after his appointment. As a circuit judge, he heard a wide variety of cases, including federal civil disputes, matters arising under the court's diversity jurisdiction

In the law of the United States, diversity jurisdiction is a form of subject-matter jurisdiction that gives United States federal courts the power to hear lawsuits that do not involve a federal question. For a federal court to have diversity ju ...

, and the occasional criminal prosecution. Most cases were under the circuit court's original jurisdiction

In common law legal systems, original jurisdiction of a court is the power to hear a case for the first time, as opposed to appellate jurisdiction, when a higher court has the power to review a lower court's decision.

India

In India, the S ...

, although Brewer heard a few appeals from federal district courts.

In ''Chicago & N.W. Railway Co. v. Dey'', a railroad company argued that the rates set by the Iowa Railroad Commission were unreasonable and should be enjoined. Despite the Supreme Court's 1877 decision in '' Munn v. Illinois'' that legislatures had the authority to determine whether rates were reasonable, Brewer ruled in the railroad's favor, issuing a preliminary injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable reme ...

on the grounds that it was unlawful to impose rates that did not adequately compensate the company. Paul argued that the decision was squarely at odds with ''Munn'', although Brodhead maintained that such claims are "at the very least misleading" since Brewer later lauded the commission and upheld the rates. In ''State v. Walruff'', Brewer firmly reiterated the position that he had expressed in ''Mugler'', appealing to "the guarantees of safety and protection to private property" to rule that the Fourteenth Amendment required Kansas to compensate beer manufacturers affected by prohibition laws. Citing ''Walruff'' and other cases, Paul commented that the future justice's "growing conservatism" was evident during this period.

Supreme Court nomination

Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English Association football, footballer who played as an Forward (association football)#Outside forward, outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the Br ...

's death in March 1889 created a vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court for President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

to fill. It took Harrison nearly nine months to select a nominee, during which time he considered forty candidates. Politicians from Matthews's home state of Ohio, including Governor Joseph Foraker, urged him to appoint the prominent Cincinnati attorney Thomas McDougall; after McDougall declined to be considered, Foraker lent his support to William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, who was then a municipal judge in Cincinnati. Other candidates suggested to Harrison included the Detroit attorney Alfred Russell, whom Vice President Levi P. Morton

Levi Parsons Morton (May 16, 1824 – May 16, 1920) was the 22nd vice president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He also served as List of ambassadors of the United States to France, United States ambassador to France, as a United States H ...

endorsed, and McCrary, who was favored by many Midwestern politicians and jurists. Harrison eventually narrowed the field to two candidates, both of whom were conservative Republicans from the Midwest: Brewer—who had the vigorous support of Senator Preston B. Plumb of Kansas and Chief Justice Albert H. Horton of the Kansas Supreme Court—and Henry Billings Brown, a federal judge from Michigan who was endorsed by several of that state's prominent political figures. During the selection process, a letter came to Harrison's attention in which Brewer suggested that Brown—his friend and former classmate at Yale—should be appointed instead of him. Harrison was reputedly so impressed by Brewer's unselfishness that he decided to nominate him to the Court.

Harrison announced his selection of the surprised Brewer on December 4, 1889, sending the nomination to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Prohibitionists, maintaining that Brewer's opinion in ''Walruff'' was "conclusive proof of what we already fear—the total surrender to the liquor dealers of the country", expressed opposition, but the selection was otherwise viewed favorably. The Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

, chaired by George F. Edmunds, considered the nomination for a week, longer than usual; despite some criticism, its members endorsed Brewer's nomination. The full Senate, in a secret session that ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' characterized as "absurd", heard prolonged speeches from several members who opposed the nominee on the grounds that he was hostile to prohibition or partial toward the railroad interests. Brewer was confirmed on December 18, 1889, by a vote of 53–11, and he took the oath of office on January 6, 1890.

Supreme Court (1890–1910)

Brewer remained on the Court for twenty years, serving until his death in 1910. In the 4,430 cases in which he participated, he wrote 539 majority or plurality opinions, 65 dissenting opinions, and 14 concurring opinions.Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his t ...

was chief justice throughout Brewer's tenure; the Fuller Court

The Fuller Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1888 to 1910, when Melville Fuller served as the eighth Chief Justice of the United States. Fuller succeeded Morrison R. Waite as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and F ...

has been described as mainly loyal to business interests and laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

economic principles, although late-twentieth-century revisionist scholars have rejected that narrative. Brewer has often been described as an extremely conservative justice. According to Paul, he "held to a strictly conservative, sometimes reactionary, position on the Court, opposing firmly the expansion of government regulatory power, state or federal" and making "little pretense of 'judicial self-restraint' and few compromises to Court consensus". Some scholars argued in the 1990s that Brewer's jurisprudence was less extreme than generally thought, contending that his reputation as a reactionary was based largely on a small and unrepresentative sample of his comments and opinions. While accepting that "Brewer can fairly be labeled a conservative", the legal scholar J. Gordon Hylton wrote in 1994 that "to say that he was a self-conscious defender of the interests of corporate America or an enthusiastic disciple of laissez-faire is both unfair and inaccurate".

Brewer held an activist

Activism consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived common good. Forms of activism range from mandate build ...

conception of the judicial role. His constitutional views were shaped by his religious beliefs, and he emphasized natural justice in his written opinions. According to the legal scholar Owen M. Fiss, Brewer and his "constant ally" Rufus W. Peckham were the "intellectual leaders" of the Fuller Court—justices who, while not always in the majority, were "influential within the dominant coalition and the source of the ideas that gave the Court its sweep and direction". Brewer's views were also aligned with those of his uncle—Justice Stephen J. Field—a staunch defender of property rights with whom he served for eight years. Brewer supported states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

and felt that the judiciary should limit governmental actions that interfere with the free market, although the legal historian Kermit L. Hall writes that his jurisprudence "was not altogether predictable" because " s Congregational, missionary, and anti-slavery roots" gave him "a sympathetic ear for the disadvantaged".

Substantive due process

Brewer and his fellow conservative justices led the Court toward rulings that interpreted theDue Process Clause

A Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which prohibit the deprivation of "life, liberty, or property" by the federal and state governments, respectively, without due proces ...

s of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments broadly to protect property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their Possession (law), possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely ...

from various regulations. Three months after his appointment, he joined the majority in '' Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Co. v. Minnesota'', a case in which the Court struck down the railroad rates set by a Minnesota commission. The decision, which endorsed the idea that the Due Process Clause contained a substantive component that limited state regulatory authority, was at odds with the Court's holding in ''Munn'' that rate-setting was a matter for legislators, not judges, to decide. Strenuously dissenting in '' Budd v. New York'', Brewer derided ''Munn'' as "radically unsound" and, using a phrase that according to Brodhead "has ever since linked his name to opposition to reform", wrote: "The paternal theory of government is to me odious." His opinion for a unanimous Court in '' Reagan v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'' built on the ''Chicago, Milwaukee'' decision, curtailing ''Munn'' and asserting that the judiciary could review the reasonableness of railroad rates. He joined the majority in '' Allgeyer v. Louisiana'', the first case to deploy the liberty of contract doctrine; the decision held that the Due Process Clause protected the right to make contracts.

The era of substantive due process reached its zenith in the 1905 case of ''Lochner v. New York

''Lochner v. New York'', 198 U.S. 45 (1905), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court holding that a New York (state), New York State statute th ...

''. ''Lochner'' involved a New York law that capped hours for bakery workers at sixty hours a week. In a decision widely viewed to be among the Supreme Court's worst, a five-justice majority held the law to be unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause. Brewer joined the Court's opinion, which was written by Peckham; it maintained that due process included a right to enter labor contracts without being subject to unreasonable governmental regulation. Peckham rejected the state's argument that the law was intended to protect workers' health, citing the "common understanding" that baking was not unhealthy. He maintained that bakers could protect their own health, arguing that the law was in fact a labor regulation in disguise. The decision provoked a now-famous dissent from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Cou ...

, who accused the majority of substituting its own economic preferences for the requirements of the Constitution. Brewer voted to strike down labor laws in other cases, such as '' Holden v. Hardy'', which involved a maximum-hour law for miners, and ''Adair v. United States

''Adair v. United States'', 208 U.S. 161 (1908), was a US labor law case of the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court which declared that bans on "yellow-dog contract, yellow-dog" contracts (that forbade workers from joi ...

'', which voided a federal law against yellow-dog contracts.

According to Hylton, the common view that Brewer uniformly opposed regulations is inaccurate.Maintaining that "Brewer's bark proved to be worse than his bite", he observes that the justice voted to uphold state regulatory action in nearly eighty percent of cases. When an Oregon law that kept female employees of factories and laundries from working more than ten hours a day was challenged in the 1908 case of ''Muller v. Oregon

''Muller v. Oregon'', 208 U.S. 412 (1908), was a list of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court. Women were permitted by state mandate fewer working h ...

'', Brewer wrote the Court's unanimous opinion upholding it. He favorably cited an extensive brief filed by Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ( ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to ...

(the Brandeis brief) that, using statistics and other evidence, argued that the law was appropriate as a matter of public policy. In an opinion that has been condemned as patronizing toward women, Brewer argued that Oregon's law was different from the one at issue in ''Lochner'' because female workers were in special need of protection due to their "physical structure and the performance of maternal functions", which put them "at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence". In other cases, he voted to uphold labor regulations involving seamen and those performing hazardous work, and he disfavored attempts to invoke the freedom-of-contract doctrine in cases that did not pertain to employment. Addressing the justice's reasons for upholding some regulations while invalidating others, Hylton comments that "Brewer 'knew an unconstitutional use of the police power when he saw one', but he was never able to define precisely what made it so".

Federal power

Taxation

Brewer joined the majority in the case of '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'', a decision that, according to Brodhead, "contributed much to he Fuller Court'sreputation for favoritism toward corporate and other forms of wealth". ''Pollock'' involved a provision of the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 that levied a two-percent tax on incomes and corporate profits that exceeded $4000 a year. Its challengers took the tax to court, where they argued that it was a

Brewer joined the majority in the case of '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'', a decision that, according to Brodhead, "contributed much to he Fuller Court'sreputation for favoritism toward corporate and other forms of wealth". ''Pollock'' involved a provision of the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 that levied a two-percent tax on incomes and corporate profits that exceeded $4000 a year. Its challengers took the tax to court, where they argued that it was a direct tax

Although the actual definitions vary between jurisdictions, in general, a direct tax is a tax imposed upon a person or property as distinct from a tax imposed upon a transaction, which is described as an indirect tax. There is a distinction betwee ...

that had not been apportioned evenly among the states, in violation of a provision of the Constitution. The Supreme Court, which had only eight members at the time because Justice Howell Edmunds Jackson was ill, initially split four-to-four on the tax's constitutionality. After Jackson returned to Washington, the justices reheard the case and, in an opinion by Fuller, struck down the tax by a 5–4 vote. (Jackson ended up dissenting, meaning that a justice switched his position; scholars have suggested a number of possible explanations, but Brodhead concludes that Brewer was unlikely to have changed his vote.) The ''Pollock'' decision, which was in effect overruled by the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, has conventionally been condemned as unfaithful to precedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

, at odds with public opinion, and protective of the interests of the rich. In two cases—'' Magoun v. Illinois Trust and Savings Bank'' and '' Knowlton v. Moore''—in which the Court upheld graduated inheritance tax

International tax law distinguishes between an estate tax and an inheritance tax. An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and pro ...

es by votes of 8–1 and 7–1, respectively, Brewer was the sole dissenter.

Interstate commerce

Brewer was generally hesitant to interpret the federal government's power to regulate interstate commerce expansively. He dissented in '' Champion v. Ames'', a case in which the Court sustained a federal law that forbade the interstate transportation of lottery tickets. He joined an opinion by Fuller, who argued that the majority was disturbing the balance between states and the federal government by effectively giving the latter a general police power. In '' United States v. E. C. Knight Co.'', Brewer joined Fuller's opinion for an 8–1 majority holding that theSherman Antitrust Act of 1890

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce and consequently prohibits unfair monopolies. It was passed by Congress and is named for S ...

did not forbid manufacturing monopolies because manufacturing was not commerce. The decision limited the Sherman Act's scope, provoking a dissent from Harlan and complaints that the Court was endeavoring to protect big business from regulation.

Nonetheless, Brewer was not uniformly deferential to the interests of business. In '' Northern Securities Co. v. United States'', he cast the deciding vote to block a merger between James J. Hill and J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ...

, two of the era's leading corporate barons. In a brief concurrence

In Western jurisprudence, concurrence (also contemporaneity or simultaneity) is the apparent need to prove the simultaneous occurrence of both ("guilty action") and ("guilty mind"), to constitute a crime; except in crimes of strict liabilit ...

that according to the legal scholar John E. Semonche "illustrates his integrity, competence, and sophistication" better than any of his other opinions, Brewer expressed support for property rights but concluded that the proposed merger was an unlawful attempt to suppress competition. His opinion endorsed the rule of reason

The rule of reason is a legal doctrine used to interpret the Sherman Antitrust Act, one of the cornerstones of United States antitrust law. While some actions like price-fixing are considered illegal ''per se', ''other actions, such as pos ...

—the idea, later accepted by his colleagues, that the Sherman Act outlawed only unreasonable restraints on commerce. Brewer joined the majority in other decisions that applied the antitrust laws more broadly, including '' United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Association'' and '' Addyston Pipe & Steel Co. v. United States''.

''In re Debs''

In the well-known case of ''In re Debs

''In re Debs'', 158 U.S. 564 (1895), was a labor law case of the United States Supreme Court, which upheld a contempt of court conviction against Eugene V. Debs. Debs had the American Railway Union continue its 1894 Pullman Strike in violatio ...

'', Brewer's opinion for the Court "open dthe door for more extensive use of injunctive power by the government", according to the legal scholar James W. Ely. After members of the American Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first Industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early ...

went on strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

in 1894 against the Pullman Palace Car Company, the federal government sought an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

against the union's leaders, arguing that the strike interfered with the delivery of mail. A federal court issued the injunction and, when Eugene V. Debs and other union officials ignored it, held them in contempt of court. Having been fined and imprisoned, they sought relief before the Supreme Court on the grounds that the court had no authority to issue the injunction. Brewer, writing for a unanimous Court, disagreed. He wrote that the executive branch had the power "to brush away all obstructions" to interstate commerce by force if necessary and concluded that an injunction could lawfully be issued to suppress a public nuisance

In English criminal law, public nuisance is an act, condition or thing that is illegal because it interferes with the rights of the general public.

In Australia

In ''Kent v Johnson'', the Supreme Court of the ACT held that public nuisance is ...

. Brewer was, according to the legal historian Edward A. Purcell Jr., an "impassioned advocate of judicial power", and the ruling in ''Debs'' expanded the federal judiciary's equitable authority. The public generally approved of the decision, although it was deplored by organized labor and, together with the contemporaneous rulings in ''Pollock'' and ''Knight'', provoked charges that the Court was biased toward the wealthy.

"A Christian nation": ''Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States''

One of Brewer's best-known opinions came in '' Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States''. The case arose when the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church hired E. Walpole Warren, a British clergyman, to be the church's rector. The church was fined $1000 for violating the Alien Contract Labor Act of 1885, under which it was "unlawful for any person, company, partnership, or corporation... to prepay the transportation, or in any way assist or encourage the importation or migration of any alien... under contract... to perform labor or service of any kind in the United States". The statute did not exempt members of the clergy, and according to Semonche "the words were clear and the application logically unassailable". Yet in an opinion by Brewer, the Court unanimously reversed the conviction. Writing that "if a literal construction of the words of a statute be absurd, the act must be so construed as to avoid the absurdity", Brewer reasoned that the law was clearly intended to forbid the importation of unskilled laborers rather than ministers. The case's emphasis on Congress's intent over the statute's text marked a turning point in the Court's treatment of

One of Brewer's best-known opinions came in '' Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States''. The case arose when the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church hired E. Walpole Warren, a British clergyman, to be the church's rector. The church was fined $1000 for violating the Alien Contract Labor Act of 1885, under which it was "unlawful for any person, company, partnership, or corporation... to prepay the transportation, or in any way assist or encourage the importation or migration of any alien... under contract... to perform labor or service of any kind in the United States". The statute did not exempt members of the clergy, and according to Semonche "the words were clear and the application logically unassailable". Yet in an opinion by Brewer, the Court unanimously reversed the conviction. Writing that "if a literal construction of the words of a statute be absurd, the act must be so construed as to avoid the absurdity", Brewer reasoned that the law was clearly intended to forbid the importation of unskilled laborers rather than ministers. The case's emphasis on Congress's intent over the statute's text marked a turning point in the Court's treatment of legislative history

Legislative history includes any of various materials generated in the course of creating legislation, such as committee reports, analysis by legislative counsel, committee hearings, floor debates, and histories of actions taken. Legislative his ...

, and the approach it represents has drawn substantial criticism from jurists such as Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectual an ...

, who described the decision as a "prototypical" example of how statutes ought not to be interpreted.

Brewer's opinion in ''Holy Trinity'' also contained a statement that, according to the legal scholar William M. Wiecek, "would be unthinkable today" from a Supreme Court justice: that the United States "is a Christian nation". He cited religious elements of historical documents, court decisions, and "American life as expressed by its laws, its business, its customs and its society" in support of his thesis that Congress could not have intended to bar clergymen from the country. The decision came during an era in which the idea that America was a Protestant country was not particularly controversial, and few objected to Brewer's comments at the time. But legal scholars and later justices have heavily criticized the "Christian nation" claim: for instance, Justice William J. Brennan decried the declaration as "arrogant[]" in a 1984 dissent. Wiecek suggests that, while Brewer was a deeply religious man who favored Christian influence on American culture, the "Christian nation" statement was "a descriptive judgment, not a normative one" and was not of great importance as a matter of law.

Race

Like most of his colleagues, Brewer rarely sided with African-Americans in civil rights cases. Writing for the Court in '' Berea College v. Kentucky'', for instance, he upheld a law that forbade schools from racially integrating their classes.Berea College

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated. It was integrated from as early as 1866 ...

had invoked ''Lochner'' to maintain that the statute infringed on its right to practice an occupation without unreasonable interference by the government. In an opinion that stood in conspicuous conflict with his ordinary support for property rights, Brewer (over Harlan's dissent) rejected that argument, concluding that states had the ability to amend corporate charters. His majority opinion in '' Hodges v. United States'' held that the federal government had no authority to prosecute a group of Arkansas whites who had driven blacks away from their jobs. He interpreted federal laws against peonage

Peon ( English , from the Spanish '' peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control ove ...

narrowly in '' Clyatt v. United States'' and struck down a provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1870 in '' James v. Bowman.'' Of the twenty-nine cases involving African-Americans' civil rights in which he participated, he ruled in their favor only six times. Although Brewer did not cast a vote in the landmark case of '' Plessy v. Ferguson''—he had returned home to Kansas due to the death of his daughter—Paul states that he undoubtedly would have joined the majority opinion upholding "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protectio ...

" segregation laws had he been present.

Citizenship, immigration, and the territories

Brewer "passionately protested the treatment of the Chinese, on both procedural and substantive grounds", according to Fiss. In '' Fong Yue Ting v. United States'', he vigorously dissented when the Court ruled that Chinese non-citizens could be deported without being provided withdue process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

, decrying the majority's understanding of the federal government's powers as "indefinite and dangerous". A displeased Brewer dissented in both '' United States v. Sing Tuck'' and '' United States v. Ju Toy'', immigration cases in which the majority declined to review the decisions of administrative officials; in ''Sing Tuck'', he wrote: "I cannot believe that the courts of this republic are so burdened with controversies about property that they cannot take time to determine the right of personal liberty by one claiming to be a citizen." He joined the majority when the Court held in '' United States v. Wong Kim Ark'' that all persons born on U.S. soil are American citizens, and he dissented when a majority in '' Yamataya v. Fisher'' rebuffed a Japanese deportee's due process claim. Although the Court as a whole sided with Asians in only 6 out of the 23 cases decided during his tenure, Brewer voted in their favor 18 times. Brodhead suggests that the justice, a lifelong advocate of Christian efforts to evangelize the world, may have felt that treating the Chinese compassionately would further the missionary cause.

In the Insular Cases (a group of decisions on whether constitutional protections applied to those living in the territories that the United States acquired after the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

), Brewer opposed Justice Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1845 – May 19, 1921) was an American politician and jurist. A native of Louisiana, White was a Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court justice for 27 years, first as an Associate Justice of ...

's doctrine of incorporation—the idea that the Constitution did not fully apply to Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico because they had not been "incorporated" by Congress. He joined the majority in '' DeLima v. Bidwell'', a case in which the Court held by a 5–4 vote that Puerto Rico was not a foreign country under federal tariff law. In another Insular Case, '' Downes v. Bidwell'', Brewer joined Fuller's dissent when the Court upheld a provision of the Foraker Act that imposed an otherwise-unconstitutional tariff on Puerto Rico. In that dissent, the Chief Justice accepted that the federal government had the ability to obtain new territories but contended that the Constitution limited its sovereignty over them. Although Brewer did not write an opinion in any of the Insular Cases, he held strong views on the matters they presented: he opposed imperialism in public remarks and wrote a letter to Fuller urging him to "stay on the court till we overthrow this unconstitutional idea of colonial supreme control".

Extrajudicial activities

According to the historian Linda Przybyszewski, Brewer was "probably the most widely read jurist in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century" due to what Justice Holmes characterized as his "itch for public speaking". He spoke prolifically on various issues, often drawing criticism from his colleagues for his frankness. The topic about which he spoke most fervently was peace: in his public addresses he decried imperialism, arms buildups, and the horrors of war. He supported the peaceable resolution of international disputes via

According to the historian Linda Przybyszewski, Brewer was "probably the most widely read jurist in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century" due to what Justice Holmes characterized as his "itch for public speaking". He spoke prolifically on various issues, often drawing criticism from his colleagues for his frankness. The topic about which he spoke most fervently was peace: in his public addresses he decried imperialism, arms buildups, and the horrors of war. He supported the peaceable resolution of international disputes via arbitration

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

, and he served with Fuller on the arbitral tribunal that resolved a boundary dispute between Venezuela and the United Kingdom. Brewer was not an unqualified pacifist, but Brodhead writes that he "was a tireless, dedicated, and eloquent advocate of peace and among the most visible and vocal critics of militarism in his time". He also expressed support for education, charities, and the rights of women and ethnic minorities. Many of Brewer's speeches were later published in print; he also edited ten-volume collections of ''The World's Best Essays'' and ''The World's Best Orations'' and co-authored with Charles Henry Butler a brief treatise on international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

. In his later years, he spoke increasingly on political topics: he decried Progressive reforms and inveighed against President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, who in turn loathed Brewer and stated in private that he had "a sweetbread for a brain" and was a "menace to the welfare of the Nation".

Personal life and death

Brewer adhered to a liberal form of Congregationalism, focusing on Jesus's ethical teachings and God's love for humankind instead of sin, hell, and theological principles more generally. He attended church all his life and taughtSunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

in Kansas and Washington, D.C. A firm supporter of missionary efforts, he was a member of the American Bible Society and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian mission, Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the l ...

. Brewer married Louise R. Landon, a native of Vermont, in 1861; they had four children. Louise died in 1898, and Brewer wed Emma Miner Mott three years afterward. Brewer's hobbies included going to the theater, hunting, playing cards, reading detective stories, and vacationing at a cottage in Vermont on Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

. He was known as a friendly and patient man.

Brewer had planned to retire from the Court when he turned seventy in 1907, but he changed his mind, saying he was "too young in spirit" to retire. In 1909, President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

characterized the Court's state as "pitiable", writing that Fuller was "almost senile", that Harlan was doing "no work", that Brewer was "so deaf that he cannot hear" and had "got beyond the point of commonest accuracy in writing his opinions", and that Brewer and Harlan were sleeping during arguments. On March 28, 1910, Brewer, who had until then been in good health, experienced a massive stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

in his Washington, D.C., home and, before doctors could arrive, died. He was seventy-two years old. The U.S. Senate adjourned on March 29 out of respect for the justice, and Taft stated that he was an "able judge". Brewer's body was returned to Leavenworth, and a funeral was held at that city's First Congregational Church; he was buried at the Mount Muncie Cemetery in nearby Lansing

Lansing () is the capital city of the U.S. state of Michigan. The most populous city in Ingham County, parts of the city extend into Eaton County and north into Clinton County. It is the sixth-most populous city in Michigan with a popul ...

. Taft nominated Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

to take his place.

Legacy

"History has not been kind to David Brewer", comments Fiss. He has faded into obscurity, in part because some of his colleagues—Field, Harlan, and Holmes—were figures of great prominence. Moreover, although public sentiment regarding the justice was mixed in the years following his death, he was almost never discussed favorably after the 1930s, being generally described as an ultra-conservative who adhered closely to laissez-faire principles and made the courts subservient to corporations. Although late-twentieth century revisionist scholarship took a less negative view of the Fuller Court as a whole, Brewer's reputation did not rise: Hylton comments that " advancing a more moderate interpretation of the Fuller Court as a body, some revisionist historians actually made Brewer seem even more of a reactionary figure than before". Nonetheless, a few scholarly voices, including Semonche, Brodhead, Hylton, and Purcell, have favored reevaluating the justice's reputation. Brodhead concluded his 1994 biography of Brewer by writing that he "deserves to be remembered as an important figure of a much misunderstood period in the judicial history of the United States".See also

* List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United StatesNotes

References

External links

Works by David J. Brewer

at

HathiTrust

HathiTrust Digital Library is a large-scale collaborative repository of digital content from research libraries. Its holdings include content digitized via Google Books and the Internet Archive digitization initiatives, as well as content digit ...

*

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brewer, David Josiah

1837 births

1910 deaths

20th-century United States federal judges

Albany Law School alumni

American Congregationalists

District attorneys in Kansas

Field family

George Washington University faculty

Judges of the United States circuit courts

People of Kansas in the American Civil War

Kansas Republicans

Kansas state court judges

Justices of the Kansas Supreme Court

United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

People from İzmir

United States federal judges appointed by Benjamin Harrison

United States federal judges appointed by Chester A. Arthur

Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

Yale College alumni