DUNNOTTAR CASTLE Large on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dunnottar Castle (, "fort on the shelving slope") is a ruined

A chapel at Dunnottar is said to have been founded by

A chapel at Dunnottar is said to have been founded by

Religious and political conflicts continued to be played out at Dunnottar through the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1685, during the rebellion of the Earl of Argyll against the new king James VII, 167 Covenanters were seized and held in a cellar at Dunnottar. The prisoners included 122 men and 45 women associated with the Whigs, an anti-Royalist group within the Covenanter movement, and had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new king. The Whigs were imprisoned from May 24 until late July. A group of 25 escaped, although two of these were killed in a fall from the cliffs, and another 15 were recaptured. Five prisoners died in the vault, and 37 of the Whigs were released after taking the oath of allegiance. The remaining prisoners were

Religious and political conflicts continued to be played out at Dunnottar through the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1685, during the rebellion of the Earl of Argyll against the new king James VII, 167 Covenanters were seized and held in a cellar at Dunnottar. The prisoners included 122 men and 45 women associated with the Whigs, an anti-Royalist group within the Covenanter movement, and had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new king. The Whigs were imprisoned from May 24 until late July. A group of 25 escaped, although two of these were killed in a fall from the cliffs, and another 15 were recaptured. Five prisoners died in the vault, and 37 of the Whigs were released after taking the oath of allegiance. The remaining prisoners were

The seized estates of the Earl Marischal were purchased in 1720 for £41,172, by the

The seized estates of the Earl Marischal were purchased in 1720 for £41,172, by the

Dunnottar's strategic location allowed its owners to control the coastal terrace between the North Sea cliffs and the hills of the

Dunnottar's strategic location allowed its owners to control the coastal terrace between the North Sea cliffs and the hills of the

The approach to the castle is overlooked by outworks on the "Fiddle Head", a promontory on the western side of the headland. The entrance is through the well-defended main gate, set in a curtain wall which entirely blocks a cleft in the rocky cliffs. The gate has a

The approach to the castle is overlooked by outworks on the "Fiddle Head", a promontory on the western side of the headland. The entrance is through the well-defended main gate, set in a curtain wall which entirely blocks a cleft in the rocky cliffs. The gate has a

The late 14th-century tower house has a stone-vaulted basement, and originally had three further storeys and a garret above. Measuring , the tower house stood high to its gable. The principal rooms included a

The late 14th-century tower house has a stone-vaulted basement, and originally had three further storeys and a garret above. Measuring , the tower house stood high to its gable. The principal rooms included a

The palace, to the north-east of the headland, was built in the late 16th century and early to mid-17th century. It comprises three main wings set out around a quadrangle, and for the most part is probably the work of the 5th Earl Marischal who succeeded in 1581.The order of construction of the palace is debated: Simpson (1966, pp.43–49) interprets the west range as the earliest (possibly before 1580), followed by the north and east ranges together, with the north-east wing added last, in 1645. Cruden follows Simpson, though McKean (2004, pp.173–174) states that the north-east wing is contemporary with the east range, and that the north range is later. Geddes (2001, pp.25–27) suggests that the palace was built from east to west. It provided extensive and comfortable accommodation to replace the rooms in the tower house. In its long, low design it has been compared to contemporary English buildings, in contrast to the Scottish tradition of taller towers still prevalent in the 16th century.

Seven identical lodgings are arranged along the west range, each opening onto the quadrangle and including windows and fireplaces. Above the lodgings of the west range comprised a gallery. Now roofless, the gallery originally had an elaborate oak ceiling, and on display was a Roman tablet taken from the

The palace, to the north-east of the headland, was built in the late 16th century and early to mid-17th century. It comprises three main wings set out around a quadrangle, and for the most part is probably the work of the 5th Earl Marischal who succeeded in 1581.The order of construction of the palace is debated: Simpson (1966, pp.43–49) interprets the west range as the earliest (possibly before 1580), followed by the north and east ranges together, with the north-east wing added last, in 1645. Cruden follows Simpson, though McKean (2004, pp.173–174) states that the north-east wing is contemporary with the east range, and that the north range is later. Geddes (2001, pp.25–27) suggests that the palace was built from east to west. It provided extensive and comfortable accommodation to replace the rooms in the tower house. In its long, low design it has been compared to contemporary English buildings, in contrast to the Scottish tradition of taller towers still prevalent in the 16th century.

Seven identical lodgings are arranged along the west range, each opening onto the quadrangle and including windows and fireplaces. Above the lodgings of the west range comprised a gallery. Now roofless, the gallery originally had an elaborate oak ceiling, and on display was a Roman tablet taken from the

Dunnottar Castle homepageDunecht Estates homepageGhosts, History, Photographs and Paintings of Dunnottar Castle from Aboutaberdeen.com

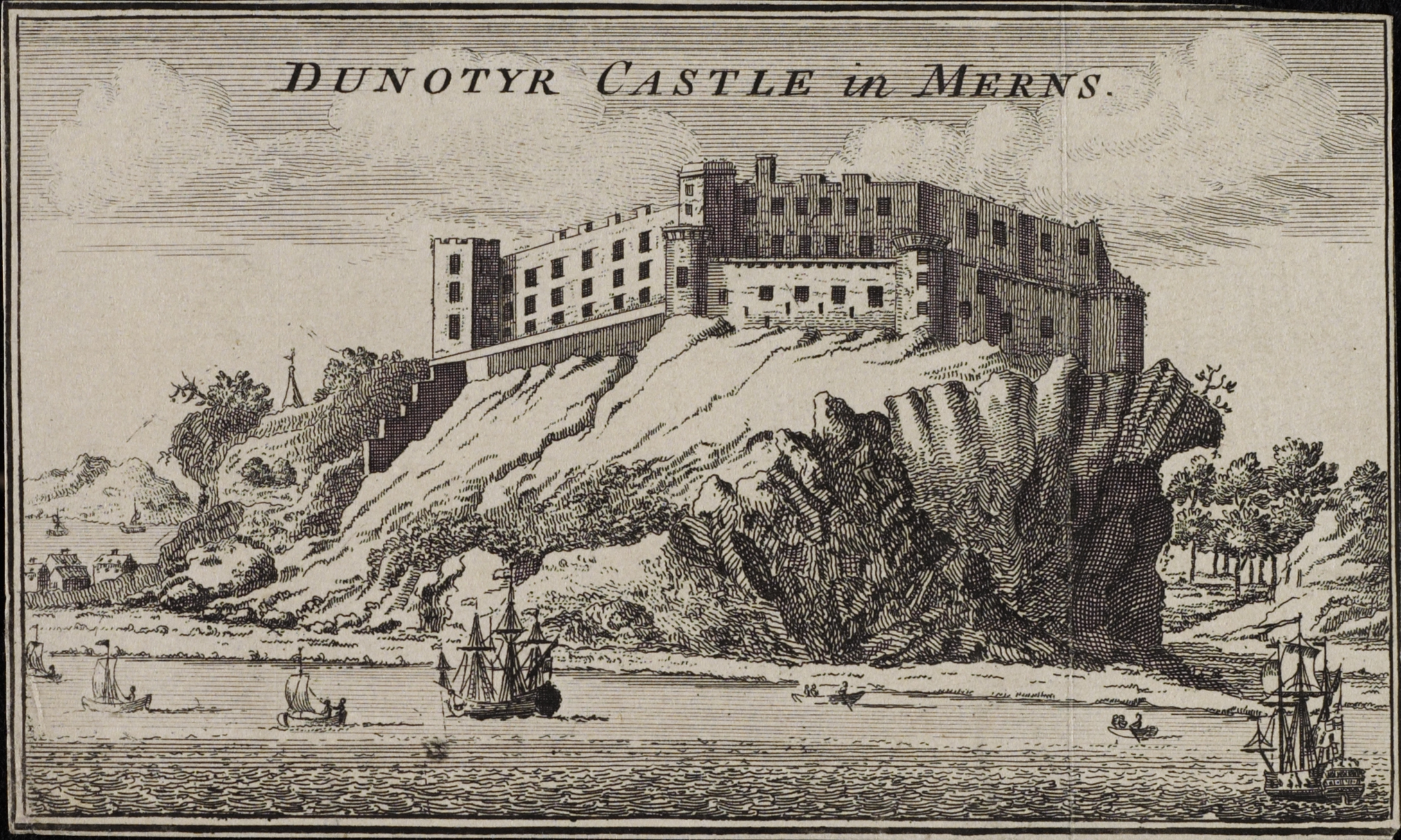

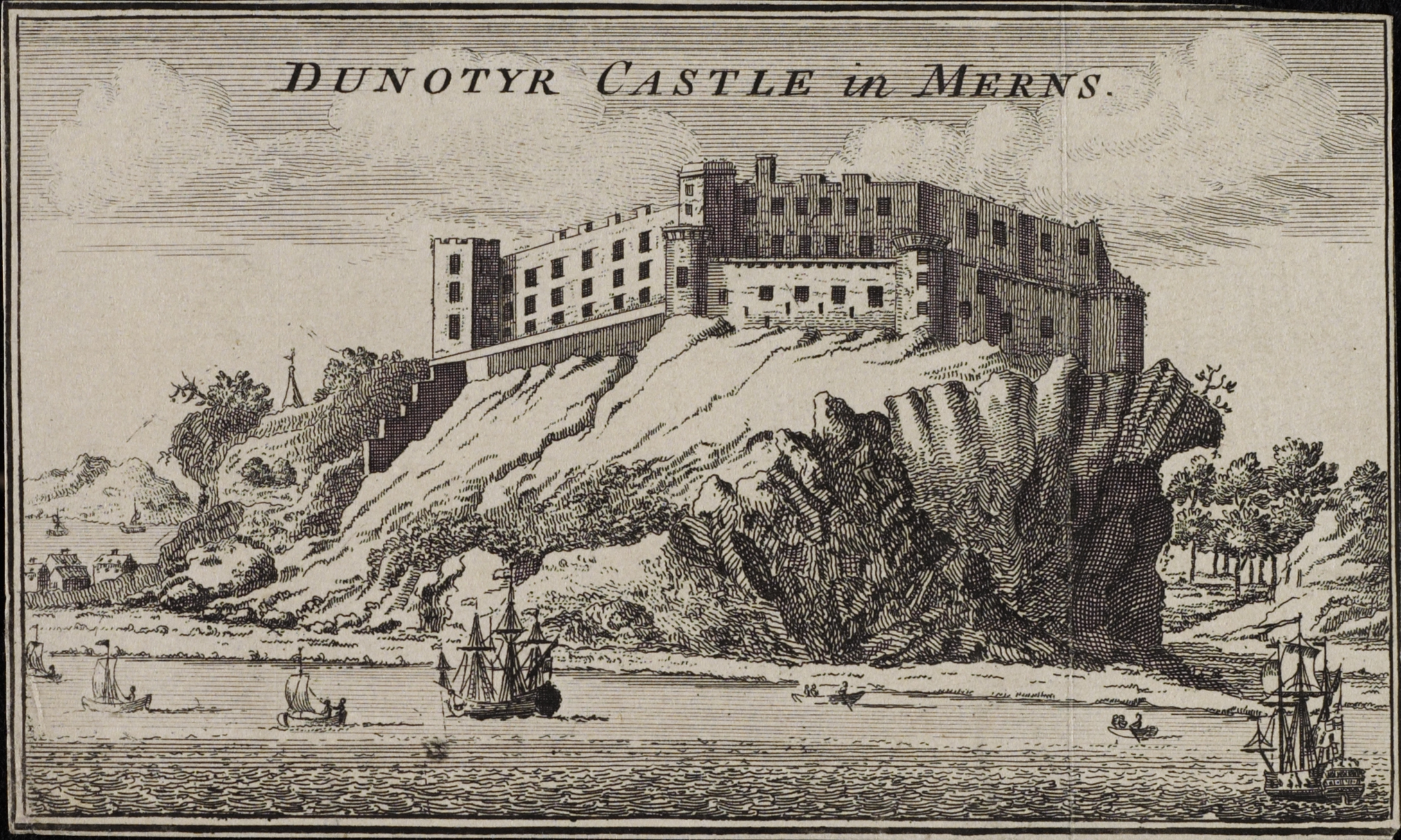

Engraving of Dunottar in 1693

by

Dunnotter Castle Virtual Tour

{{Kincardine and Mearns, Aberdeenshire places, state = collapsed Headlands of Scotland Listed castles in Scotland Promontory forts in Scotland Ruined castles in Aberdeenshire Scheduled monuments in Aberdeenshire Romanesque architecture in Scotland 13th-century establishments in Scotland Stonehaven Landforms of Aberdeenshire Castles in Aberdeenshire

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

fortress

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from L ...

located upon a rocky headland on the northeast coast of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, about south of Stonehaven

Stonehaven ( ) is a town on the northeast coast of Scotland, south of Aberdeen. It had a population of 11,177 at th2022 Census

Stonehaven was formerly the county town of Kincardineshire, succeeding the now abandoned town of Kincardine, Aberd ...

in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire (; ) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the Shires of Scotland, historic county of Aberdeenshire (historic), Aberdeenshire, which had substantial ...

.

The surviving buildings are largely of the 15th and 16th centuries, but the site is believed to have been fortified in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. Dunnottar has played a prominent role in the history of Scotland

The recorded history of Scotland begins with the Scotland during the Roman Empire, arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the Roman province, province of Roman Britain, Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. No ...

through to the 18th-century Jacobite risings

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

because of its strategic location and defensive strength.

Dunnottar is best known as the place where the Honours of Scotland

The Honours of Scotland (, ), informally known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, are the regalia that were worn by List of Scottish monarchs, Scottish monarchs at their Coronation_of_the_British_monarch#Scottish_coronations, coronation. Kept in the ...

, the Scottish crown jewels, were hidden from Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

's invading army in the 17th century. The property of the Keiths from the 14th century, and the seat of the Earl Marischal

The title of Earl Marischal was created in the Peerage of Scotland for William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland.

History

The office of Marischal of Scotland (or ''Marascallus Scotie'' or ''Marscallus Scotiae'') had been hereditary, held ...

, Dunnottar declined after the last Earl forfeited his titles by taking part in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland for the exiled Stuarts.

At Braemar, Aberdeenshire, local landowner the Ear ...

. The castle was restored in the 20th century and is now open to the public.

The ruins of the castle are spread over , surrounded by steep cliffs that drop to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, below. A narrow strip of land joins the headland to the mainland, along which a steep path leads up to the gatehouse. The various buildings within the castle include the 14th-century tower house as well as the 16th-century palace. Dunnottar Castle is a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

, and twelve structures on the site were listed buildings

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, H ...

.

History

Early Middle Ages

A chapel at Dunnottar is said to have been founded by

A chapel at Dunnottar is said to have been founded by St Ninian

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason, he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedicatio ...

in the 5th century, although it is not clear when the site was first fortified, but in any case the legend is late and highly implausible. Possibly the earliest written reference to the site is found in the ''Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' () are annals of History of Ireland, medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luin� ...

'' which record two sieges of 'Dún Foither' in 681 and 694. The earlier event has been interpreted as an attack by Brude, the Pictish king of Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

, to extend his power over the north-east coast of Scotland. The ''Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

The ''Chronicle of the Kings of Alba'', or ''Scottish Chronicle'', is a short written chronicle covering the period from the time of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpín) (d. 858) until the reign of Kenneth II (Cináed mac Maíl Coluim) (r. 971� ...

'' records that King Donald II of Scotland, the first ruler to be called ''rí Alban'' (King of Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English-language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingd ...

), was killed at Dunnottar during an attack by Vikings in 900. The English king Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ; ; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern histori ...

led a force into Scotland in 934, and raided as far north as Dunnottar according to the account of Symeon of Durham

__NOTOC__

Symeon (or Simeon) of Durham (fl. c.1090 to c. 1128 ) was an English chronicler and a monk of Durham Priory.

Biography

Symeon was a Benedictine monk at Durham Cathedral at the end of the eleventh century. He may have been one of 23 mo ...

.

W. D. Simpson speculated that a motte

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or Bailey (castle), bailey, surrounded by a protective Rampart (fortificati ...

might lie under the present castle, but excavations in the 1980s failed to uncover substantive evidence of early medieval fortification. The discovery of a group of Pictish stones

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the River Clyde, Clyde-River Forth, Forth line and on the Eastern side of the ...

at Dunnicaer, a nearby sea stack

A stack or sea stack is a geological landform consisting of a steep and often vertical column or columns of rock in the sea near a coast, formed by wave erosion. Stacks are formed over time by wind and water, processes of coastal geomorphology. ...

, has prompted speculation that Dún Foither was actually located on the adjacent headland of Bowduns, to the north.

Later Middle Ages

During the reign of KingWilliam the Lion

William the Lion (), sometimes styled William I (; ) and also known by the nickname ; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Alba from 1165 to 1214. His almost 49 ...

(ruled 1165–1214), Dunnottar was a centre of local administration for The Mearns. The castle is named in the ''Roman de Fergus

The ''Roman de Fergus'' is an Arthurian romance written in Old French probably at the very beginning of the 13th century, by a very well educated author who named himself Guillaume le Clerc (William the Clerk). The main character is Fergus, ...

'', an early 13th-century Arthurian

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a leader of the post-Ro ...

romance, in which the hero Fergus must travel to Dunnottar to retrieve a magic shield.Simpson (1966), p. 4. In May 1276, a church on the site was consecrated by William Wishart, Bishop of St Andrews. The poet Blind Harry

Blind Harry ( 1440 – 1492), also known as Harry, Hary or Henry the Minstrel, is renowned as the author of ''The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace'', more commonly known as '' The Wallace''. This is ...

relates that William Wallace

Sir William Wallace (, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army at the Battle of St ...

captured Dunnottar from the English in 1297, during the Wars of Scottish Independence

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and 14th centuries.

The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of Scotla ...

. He is said to have imprisoned 4,000 English prisoners of war in the church and burned them alive.Coventry (2006), pp. 278–279.

In 1336, Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

ordered William Sinclair, 8th Baron of Roslin, to sail eight ships to the partially ruined Dunnottar for the purpose of rebuilding and fortifying the site as a forward resupply base for his northern campaign. Sinclair took with him 160 soldiers, horses, and a corps of masons and carpenters.Sumption (1991). Edward himself visited in July, but the English efforts were undone before the end of the year when the Scottish Regent Sir Andrew Murray led a force that captured and again destroyed the defences of Dunnottar.

In the 14th century, Dunnottar was granted to William de Moravia, 5th Earl of Sutherland (d.1370);McGladdery (2004). in 1346, a licence to crenellate was issued by David II.Geddes (2001), pp. 25–27. Around 1359, William Keith, Marischal of Scotland, married Margaret Fraser, niece of Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (), was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert led Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against Kingdom of Eng ...

, and was granted the barony of Dunnottar at this time. Keith then gave the lands of Dunnottar to his daughter Christian and son-in-law William Lindsay of Byres, but in 1392 an excambion

In Scots law, excambion is the exchange of land. The deed whereby this is effected is termed "Contract of Excambion".

There is an implied real warranty in this contract, so that if one portion is evicted or taken away on a superior title, the party ...

(exchange) was agreed whereby Keith regained Dunnottar and Lindsay took lands in Fife. William Keith completed construction of the tower house at Dunnottar, but was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in communion with other members of the con ...

for building on the consecrated ground associated with the parish church. Keith had provided a new parish church closer to Stonehaven, but was forced to write to the Pope, Benedict XIII, who issued a bull in 1395 lifting the excommunication. William Keith's descendants were made Earls Marischal in the mid 15th century, and they held Dunottar until the 18th century.

16th-century rebuilding

James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

came to Dunnottar on 15 October 1504. A child played a musical instrument called a monochord

A monochord, also known as sonometer (see below), is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument, involving one (mono-) string ( chord). The term ''monochord'' is sometimes used as the class-name for any musical stringed instrument ...

for him, and he gave money to poor people. The king had brought his Italian minstrels and an African drummer, known as the " More taubronar".

Through the 16th century, the Keiths improved and expanded their principal seats: at Dunnottar and also at Keith Marischal

Keith Marischal is a Scottish Baronial country house lying in the parish of Humbie, East Lothian, Scotland. The original building was an L Plan Castle, "L-shaped" Tower house, built long before 1589 when it was extended into a U-shaped courtyard ...

in East Lothian. James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

visited Dunnottar in 1504, and in 1531 James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

exempted the Earl's men from military service on the grounds that Dunnottar was one of the "principall strenthis of our realme". Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, visited in 1562 after the Battle of Corrichie

The Battle of Corrichie was fought on the slopes of the Hill of Fare in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, on 28 October 1562. It was fought between the forces of George Gordon, 4th Earl of Huntly, chief of Clan Gordon, and the forces of Mary, Queen of ...

, and returned in 1564. James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

stayed for 10 days in 1580, as part of his progress

Progress is movement towards a perceived refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. It is central to the philosophy of progressivism, which interprets progress as the set of advancements in technology, science, and social organization effic ...

through Fife and Angus, during which a meeting of the Privy Council was convened at Dunnottar.

King James came again on 17 April 1589 and spent the night at Cowie Cowie may refer to:

People

*Cowie (surname)

Places

*Cowie, Aberdeenshire, an historic fishing village located at the north side of Stonehaven, Scotland

**Cowie Castle, a ruined castle in Aberdeenshire, Scotland

**Chapel of St. Mary and St. Nathal ...

watching for the Catholic rebel earls of Huntly and Erroll. During the rebellion of Catholic nobles in 1592, Dunnottar was captured by Captain Carr on behalf of the Earl of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existing marquessate in Scotland, and the second-oldest in the British Isles; only the English ma ...

, but was restored to Lord Marischal just a few weeks later.

In 1581, George Keith succeeded as 5th Earl Marischal, and began a large-scale reconstruction that saw the medieval fortress converted into a more comfortable home. As the founder of Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has been the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. The building was constructed for and is on long-term lease fr ...

in Aberdeen, the 5th Earl valued Dunnottar as much for its dramatic situation as for its security. A "palace" comprising a series of ranges around a quadrangle was built on the north-eastern cliffs, creating luxurious living quarters with sea views. The 13th-century chapel was restored and incorporated into the quadrangle. An impressive stone gatehouse was constructed, now known as Benholm's Lodging, featuring numerous gun ports facing the approach. Although impressive, these are likely to have been fashionable embellishments rather than genuine defensive features. The earl had a suite of 'Samson

SAMSON (Software for Adaptive Modeling and Simulation Of Nanosystems) is a computer software platform for molecular design being developed bOneAngstromand previously by the NANO-D group at the French Institute for Research in Computer Science an ...

' tapestries which may have represented his religious outlook.

Civil wars

In 1639,William Keith, 7th Earl Marischal

William Keith, 7th Earl Marischal (16141670 or 1671) was a Scottish nobleman and Covenanter. He was the eldest son of William Keith, 6th Earl Marischal.

Life

During the English Civil War, the 7th Earl Marischal joined James Graham, 1st Marque ...

, came out in support of the Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

, a Presbyterian movement who opposed the established Episcopal Church and the changes which Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was attempting to impose. With James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman, poet, soldier and later viceroy and captain general of Scotland. Montrose initially joined the Covenanters in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, but subsequ ...

, he marched against the Catholic James Gordon, 2nd Viscount Aboyne

James Gordon, 2nd Viscount Aboyne (c. 1620 – February 1649) was the second son of George Gordon, 2nd Marquess of Huntly, a Scotland, Scottish royalist commander in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Early life

Aboyne was a member of the powerf ...

, Earl of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existing marquessate in Scotland, and the second-oldest in the British Isles; only the English ma ...

, and defeated an attempt by the Royalists to seize Stonehaven

Stonehaven ( ) is a town on the northeast coast of Scotland, south of Aberdeen. It had a population of 11,177 at th2022 Census

Stonehaven was formerly the county town of Kincardineshire, succeeding the now abandoned town of Kincardine, Aberd ...

. However, when Montrose changed sides to the Royalists and marched north, Marischal remained in Dunnottar, even when given command of the area by Parliament, and even when Montrose burned Stonehaven.Stevenson (2004).

Marischal then joined with the Engager

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamentarians after his defeat in the First Civil War.

...

faction, who had made a deal with the king, and led a troop of horse to the Battle of Preston (1648)

The battle of Preston was fought on 17 August 1648 during the Second English Civil War. A Roundhead, Parliamentarian army commanded by Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant General Oliver Cromwell attacked a considerably larger force ...

in support of the royalists. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Engagers gave their allegiance to his son and heir. Charles II was proclaimed king, arriving in Scotland in June 1650. He visited Dunnottar in July 1650, but his presence in Scotland prompted Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

to lead a force into Scotland, defeating the Scots at Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the Anglo–Scottish border, English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and ...

in September 1650.

Honours of Scotland

Charles II was crowned atScone Palace

Scone Palace is a Category A- listed historic house near the village of Scone and the city of Perth, Scotland. Ancestral seat of Earls of Mansfield, built in red sandstone with a castellated roof, it is an example of the Gothic Revival style ...

on 1 January 1651, at which the Honours of Scotland

The Honours of Scotland (, ), informally known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, are the regalia that were worn by List of Scottish monarchs, Scottish monarchs at their Coronation_of_the_British_monarch#Scottish_coronations, coronation. Kept in the ...

(the regalia of crown, sword and sceptre) were used. However, with Cromwell's troops in Lothian, the honours could not be returned to Edinburgh. The Earl Marischal, as Marischal of Scotland, had formal responsibility for the honours, and in June the Privy Council duly decided to place them at Dunnottar.Groome (1885), pp. 442–443. They were brought to the castle by Katherine Drummond, hidden in sacks of wool.Baigent (2004). Sir George Ogilvie (or Ogilvy) of Barras was appointed lieutenant-governor of the castle, and given responsibility for its defence.Henderson & Furgol (2004).

In November 1651, Cromwell's troops called on Ogilvie to surrender, but he refused. During the subsequent blockade of the castle, the removal of the Honours of Scotland was planned by Elizabeth Douglas, wife of Sir George Ogilvie, and Christian Fletcher, wife of James Granger, minister of Kinneff Parish Church. The king's papers were first removed from the castle by Anne Lindsay, a kinswoman of Elizabeth Douglas, who walked through the besieging force with the papers sewn into her clothes. Two stories exist regarding the removal of the honours themselves. Fletcher stated in 1664 that over the course of three visits to the castle in February and March 1652, she carried away the crown, sceptre, sword and sword case hidden amongst sacks of goods. Another account, given in the 18th century by a tutor to the Earl Marischal, records that the honours were lowered from the castle onto the beach, where they were collected by Fletcher's servant and carried off in a creel (basket) of seaweed. Having smuggled the honours from the castle, Fletcher and her husband buried them under the floor of the Old Kirk at Kinneff.

By May 1652 the commander of the blockade, Colonel Thomas Morgan, had taken delivery of the artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

necessary for the reduction of Dunnottar. Ogilvie surrendered on 24 May, on condition that the garrison could go free. Finding the honours gone, the Cromwellians imprisoned Ogilvie and his wife in the castle until the following year, when a false story was put about suggesting that the honours had been taken overseas. Much of the castle property was removed, including twenty-one brass cannons, and Marischal was required to sell further lands and possessions to pay fines imposed by Cromwell's government.

At the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the honours were removed from Kinneff Church and returned to the king. Ogilvie quarrelled with Marischal's mother over who would take credit for saving the honours, though he was eventually rewarded with a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

cy. Fletcher was awarded 2,000 merks by Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

but the sum was never paid.

Whigs and Jacobites

Religious and political conflicts continued to be played out at Dunnottar through the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1685, during the rebellion of the Earl of Argyll against the new king James VII, 167 Covenanters were seized and held in a cellar at Dunnottar. The prisoners included 122 men and 45 women associated with the Whigs, an anti-Royalist group within the Covenanter movement, and had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new king. The Whigs were imprisoned from May 24 until late July. A group of 25 escaped, although two of these were killed in a fall from the cliffs, and another 15 were recaptured. Five prisoners died in the vault, and 37 of the Whigs were released after taking the oath of allegiance. The remaining prisoners were

Religious and political conflicts continued to be played out at Dunnottar through the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1685, during the rebellion of the Earl of Argyll against the new king James VII, 167 Covenanters were seized and held in a cellar at Dunnottar. The prisoners included 122 men and 45 women associated with the Whigs, an anti-Royalist group within the Covenanter movement, and had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new king. The Whigs were imprisoned from May 24 until late July. A group of 25 escaped, although two of these were killed in a fall from the cliffs, and another 15 were recaptured. Five prisoners died in the vault, and 37 of the Whigs were released after taking the oath of allegiance. The remaining prisoners were transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln.

It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she ...

to Perth Amboy, New Jersey

Perth Amboy is a city (New Jersey), city in northeastern Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, within the New York metropolitan area, New York Metro Area. As of the 2020 United States census, the city' ...

, as part of a colonisation scheme devised by George Scot of Pitlochie. Many, like Scot himself, died on the voyage. The cellar, located beneath the "King's Bedroom" in the 16th-century castle buildings, has since become known as the "Whigs' Vault".

Both the Jacobites (supporters of the exiled Stuarts

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been hel ...

) and the Hanoverians

The House of Hanover ( ) is a European royal house with roots tracing back to the 17th century. Its members, known as Hanoverians, ruled Hanover, Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Empire at various times during the 17th to 20th centurie ...

(supporters of George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

and his descendants) used Dunnottar Castle. In 1689, during Viscount Dundee's campaign in support of the deposed James VII, the castle was garrisoned for William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

with Lord Marischal appointed captain. Seventeen suspected Jacobites from Aberdeen were seized and held in the fortress for around three weeks, including George Liddell, professor of mathematics at Marischal College. In the Jacobite Rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Francis Edward Stuart, James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland ...

George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal, took an active role with the rebels, leading cavalry at the Battle of Sheriffmuir

The Battle of Sheriffmuir (, ) was an engagement in 1715 at the height of the Jacobite rising of 1715, Jacobite rising in Scotland. The battlefield has been included in the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland and protected by Histor ...

. After the subsequent abandonment of the rising Lord Marischal fled to the Continent, eventually becoming French ambassador for Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

of Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. Meanwhile, in 1716, his titles and estates including Dunnottar were declared forfeit

Forfeit or forfeiture may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Forfeit'', a 2007 thriller film starring Billy Burke

* "Forfeit", a song by Chevelle from '' Wonder What's Next''

* '' Forfeit/Fortune'', a 2008 album by Crooked Fingers

...

to the crown.

Later history

York Buildings Company

The York Buildings Company was an English company in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Waterworks

The full name of the company was The Governor and Company for Raising the Thames Water at York Buildings. The undertaking was established in ...

who dismantled much of the castle. In 1761, the Earl briefly returned to Scotland and bought back Dunnottar only to sell it five years later to Alexander Keith (1736–1819), an Edinburgh lawyer who served as Knight Marischal of Scotland. Dunnottar was held by Alexander Keith and then his son, Sir Alexander Keith (1768–1832) before being inherited in 1852 by Sir Patrick Keith-Murray of Ochtertyre, who in turn sold it in July 1873 to Major Alexander Innes of Cowie and Raemoir for about £80,000. It was purchased by Weetman Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray

Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray, (15 July 1856 – 1 May 1927), known as Sir Weetman Pearson, Bt between 1894 and 1910, and as Lord Cowdray between 1910 and 1917, was an English engineer, oil industrialist, Benefactor (law), be ...

, in 1925, after which his wife embarked on a programme of repairs. Since that time, the castle has remained in the family, and has been open to the public, attracting 52,500 visitors in 2009, and over 135,000 visitors in 2019.

Dunnottar Castle, and the headland on which is stands, was designated as a Scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

in 1970.

In 1972, twelve of the structures at Dunnottar were listed. Three buildings were listed at category A as being of "national importance": the keep; the entrance gateway; and Benholm's Lodging. The remaining listings were at category B as being of "regional importance". However, in 2018, the listed status for those buildings was removed as part of Historic Environment Scotland

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) () is an executive non-departmental public body responsible for investigating, caring for and promoting Scotland's historic environment. HES was formed in 2015 from the merger of government agency Historic Sc ...

's "Dual Designation 2A Project".

The Hon.

''The Honourable'' (Commonwealth English) or ''The Honorable'' (American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of cert ...

Charles Anthony Pearson, the younger son of the 3rd Viscount Cowdray, currently owns and runs Dunnottar Castle which is part of the Dunecht Estates. Portions of the 1990 film ''Hamlet'', starring Mel Gibson

Mel Columcille Gerard Gibson (born January 3, 1956) is an American actor and filmmaker. The recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Mel Gibson, multiple accolades, he is known for directing historical films as well for his act ...

and Glenn Close

Glenda Veronica Close (born March 19, 1947) is an American actress. In a career spanning over five decades on Glenn Close on screen and stage, screen and stage, she has received List of awards and nominations received by Glenn Close, numerous ac ...

, were shot there. In the Disney

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

movie '' Brave'', Dunnottar Castle was chosen for Merida's home.

Description

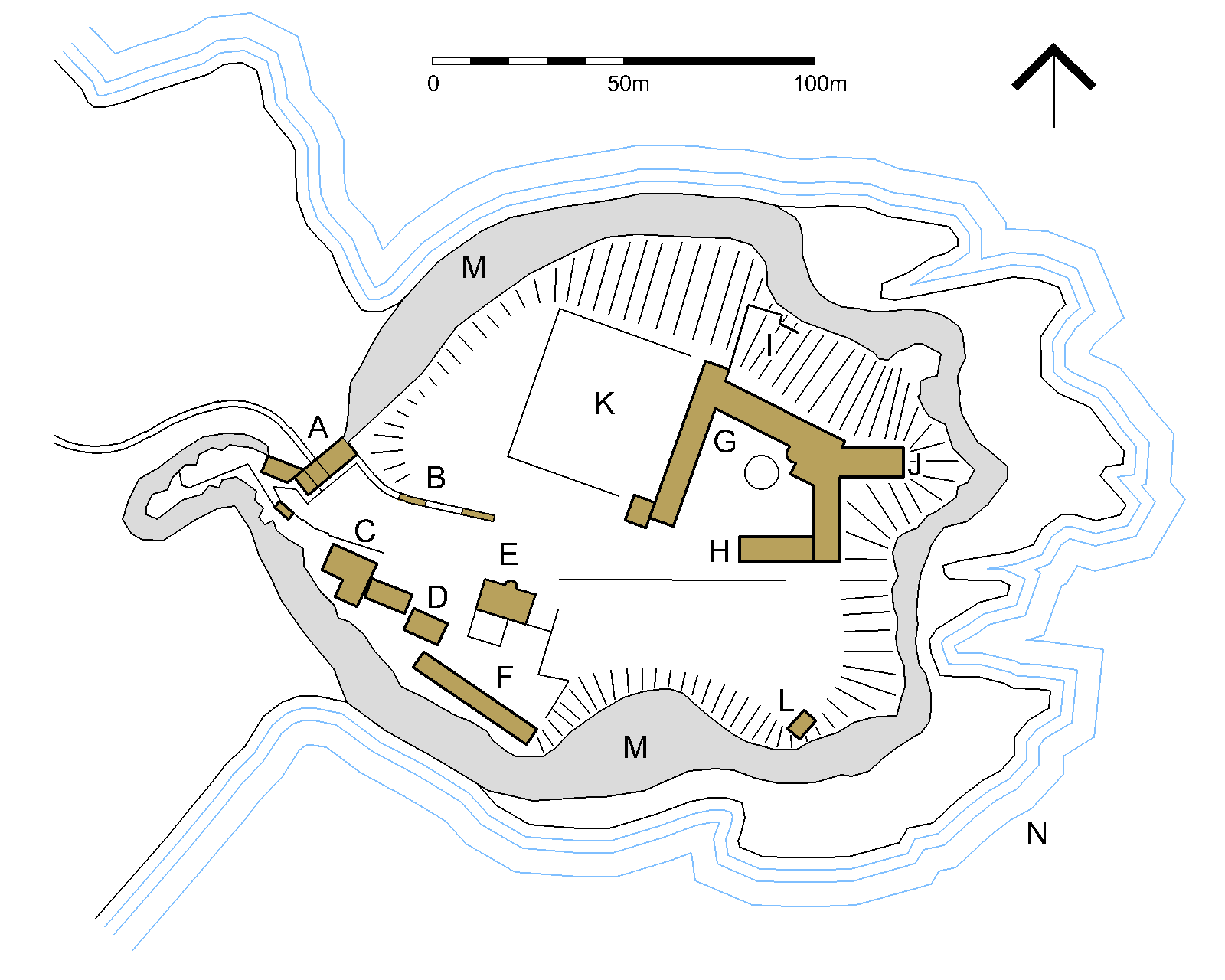

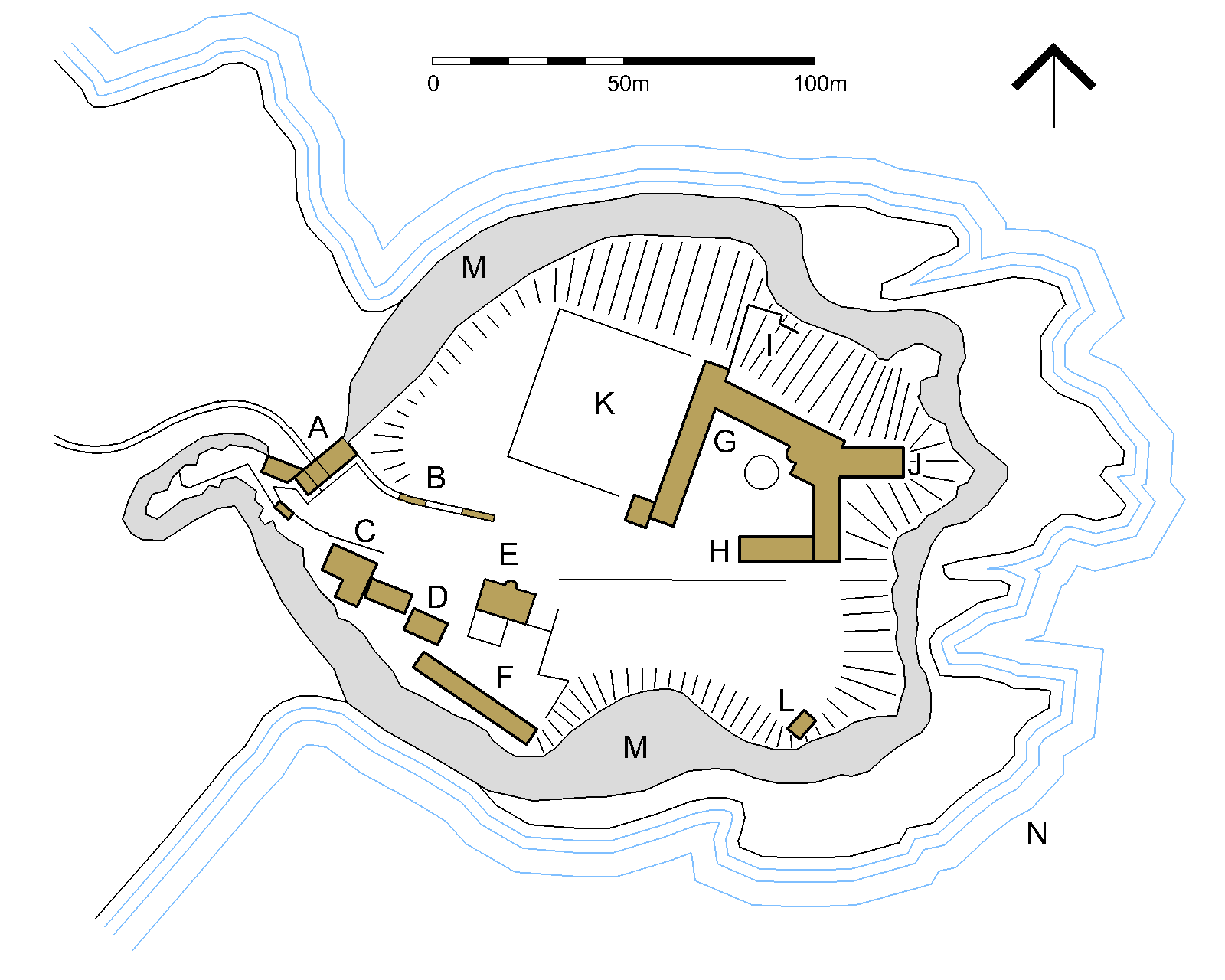

Dunnottar's strategic location allowed its owners to control the coastal terrace between the North Sea cliffs and the hills of the

Dunnottar's strategic location allowed its owners to control the coastal terrace between the North Sea cliffs and the hills of the Mounth

The Mounth ( ) is the broad upland in northeast Scotland between the Highland Boundary and the River Dee, at the eastern end of the Grampians.

Name and etymology

The name ''Mounth'' is ultimately of Pictish origin. The name is derived from ...

, inland, which enabled access to and from the north-east of Scotland. The site is accessed via a steep, footpath (with modern staircases) from a car park on the coastal road, or via a cliff-top path from Stonehaven.

Dunnottar's several buildings, put up between the 13th and 17th centuries, are arranged across a headland covering around . The dominant building, viewed from the land approach, is the 14th-century keep

A keep is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in castles that were fortified residen ...

or tower house. The other principal buildings are the gatehouse; the chapel; and the 16th-century "palace" which incorporates the "Whigs' Vault".

Defences

The approach to the castle is overlooked by outworks on the "Fiddle Head", a promontory on the western side of the headland. The entrance is through the well-defended main gate, set in a curtain wall which entirely blocks a cleft in the rocky cliffs. The gate has a

The approach to the castle is overlooked by outworks on the "Fiddle Head", a promontory on the western side of the headland. The entrance is through the well-defended main gate, set in a curtain wall which entirely blocks a cleft in the rocky cliffs. The gate has a portcullis

A portcullis () is a heavy, vertically closing gate typically found in medieval fortifications. It consists of a latticed Grille (architecture), grille made of wood and/or metal, which slides down grooves inset within each jamb of the gateway.

...

and has been partly blocked up. Alongside the main gate is the 16th-century Benholm's Lodging, a five-storey building cut into the rock, which incorporated a prison with apartments above. Three tiers of gun ports face outwards from the lower floors of Benholm's Lodging, while inside the main gate, a group of four gun ports face the entrance. The entrance passage then turns sharply to the left, running underground through two tunnels to emerge near the tower house.

Simpson contends that these defences are "without exception the strongest in Scotland", although later writers have doubted the effectiveness of the gun ports. Cruden notes that the alignment of the gun ports in Benholm's Lodging, facing across the approach rather than along, means that they are of limited efficiency. The practicality of the gun ports facing the entrance has also been questioned, though an inventory of 1612 records that four brass cannons were placed here.

A second access to the castle leads up from a rocky cove, the aperture to a marine cave on the northern side of the Dunnottar cliffs into which a small boat could be brought. From here a steep path leads to the well-fortified postern gate on the cliff-top, which in turn offers access to the castle via the Water Gate in the palace. Artillery defences, taking the form of earthworks, surround the north-west corner of the castle, facing inland, and the south-east, facing seaward.MacGibbon & Ross (1887), p. 573. A small sentry box or guard house stands by the eastern battery, overlooking the coast.

Tower house and surrounding buildings

The late 14th-century tower house has a stone-vaulted basement, and originally had three further storeys and a garret above. Measuring , the tower house stood high to its gable. The principal rooms included a

The late 14th-century tower house has a stone-vaulted basement, and originally had three further storeys and a garret above. Measuring , the tower house stood high to its gable. The principal rooms included a great hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages. It continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the great cha ...

and a private chamber for the lord, with bedrooms upstairs. Beside the tower house is a storehouse, and a blacksmith's forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the ...

with a large chimney. A stable block is ranged along the southern edge of the headland. Nearby is Waterton's Lodging, also known as the Priest's House, built around 1574,Howard (1995), p. 83. possibly for the use of William Keith (died 1580), son of the 4th Earl Marischal. This small self-contained house includes a hall and kitchen at ground level, with private chambers above, and has a projecting spiral stair on the north side. It is named for Thomas Forbes of Waterton, an attendant of the 7th Earl.

Palace

The palace, to the north-east of the headland, was built in the late 16th century and early to mid-17th century. It comprises three main wings set out around a quadrangle, and for the most part is probably the work of the 5th Earl Marischal who succeeded in 1581.The order of construction of the palace is debated: Simpson (1966, pp.43–49) interprets the west range as the earliest (possibly before 1580), followed by the north and east ranges together, with the north-east wing added last, in 1645. Cruden follows Simpson, though McKean (2004, pp.173–174) states that the north-east wing is contemporary with the east range, and that the north range is later. Geddes (2001, pp.25–27) suggests that the palace was built from east to west. It provided extensive and comfortable accommodation to replace the rooms in the tower house. In its long, low design it has been compared to contemporary English buildings, in contrast to the Scottish tradition of taller towers still prevalent in the 16th century.

Seven identical lodgings are arranged along the west range, each opening onto the quadrangle and including windows and fireplaces. Above the lodgings of the west range comprised a gallery. Now roofless, the gallery originally had an elaborate oak ceiling, and on display was a Roman tablet taken from the

The palace, to the north-east of the headland, was built in the late 16th century and early to mid-17th century. It comprises three main wings set out around a quadrangle, and for the most part is probably the work of the 5th Earl Marischal who succeeded in 1581.The order of construction of the palace is debated: Simpson (1966, pp.43–49) interprets the west range as the earliest (possibly before 1580), followed by the north and east ranges together, with the north-east wing added last, in 1645. Cruden follows Simpson, though McKean (2004, pp.173–174) states that the north-east wing is contemporary with the east range, and that the north range is later. Geddes (2001, pp.25–27) suggests that the palace was built from east to west. It provided extensive and comfortable accommodation to replace the rooms in the tower house. In its long, low design it has been compared to contemporary English buildings, in contrast to the Scottish tradition of taller towers still prevalent in the 16th century.

Seven identical lodgings are arranged along the west range, each opening onto the quadrangle and including windows and fireplaces. Above the lodgings of the west range comprised a gallery. Now roofless, the gallery originally had an elaborate oak ceiling, and on display was a Roman tablet taken from the Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall () was a turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth. Built some twenty years after Hadrian's Wall to the south ...

.The tablet is now in the Hunterian Museum

The Hunterian is a complex of museums located in and operated by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. It is the oldest museum in Scotland. It covers the Hunterian Museum, the Hunterian Art Gallery, the Mackintosh House, the Zoology M ...

, Glasgow. Simpson (1966), p. 43. At the north end of the gallery was a drawing room

A drawing room is a room in a house where visitors may be entertained, and an alternative name for a living room. The name is derived from the 16th-century terms withdrawing room and withdrawing chamber, which remained in use through the 17th ce ...

linked to the north range. The gallery could also be accessed from the Silver House to the south, which incorporated a broad stairway with a treasury above.

The basement of the north range incorporates kitchens and stores, with a dining room and great chamber

The great chamber was the second most important room in a medieval or Tudor English castle, palace, mansion, or manor house after the great hall. Medieval great halls were the ceremonial centre of the household and were not private at all; the g ...

above. At ground floor level is the Water Gate, between the north and west ranges, which gives access to the postern on the northern cliffs. The east and north ranges are linked via a rectangular stair. The east range has a larder, brewhouse and bakery at ground level, with a suite of apartments for the countess above. A north-east wing contains the Earl's apartments, and includes the "King's Bedroom" in which Charles II stayed. In this room is a carved stone inscribed with the arms of the 7th Earl and his wife, and the date 1645. Below these rooms is the Whigs' Vault, a cellar measuring . This cellar, in which the Covenanters were held in 1685, has a large eastern window, as well as a lower vault accessed via a trapdoor in the floor. Of the chambers in the palace, only the dining room and the Silver House remain roofed, having been restored in the 1920s.

The central area contains a circular cistern or fish pond, across and deep,Simpson (1966), pp. 52–53. and a bowling green is located to the west. At the south-east corner of the quadrangle is the chapel, consecrated in 1276 and largely rebuilt in the 16th century. Medieval walling and two 13th-century windows remain, and there is a graveyard to the south.

See also

*Dunnottar Parish Church

Dunnottar Parish Church is a parish church of the Church of Scotland, serving Stonehaven in the south of Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is within the Church of Scotland's Presbytery of Kincardine and Deeside. During 2020, the congregation united to ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Dunnottar Castle homepage

Engraving of Dunottar in 1693

by

John Slezer

John Slezer (before 1650 – 1717) was a German-born military engineer and artist.

Life

Slezer was born in a German-speaking region of Europe, possibly the upper Rhineland. He may have spent his early years in military service to the Hous ...

at National Library of ScotlandDunnotter Castle Virtual Tour

{{Kincardine and Mearns, Aberdeenshire places, state = collapsed Headlands of Scotland Listed castles in Scotland Promontory forts in Scotland Ruined castles in Aberdeenshire Scheduled monuments in Aberdeenshire Romanesque architecture in Scotland 13th-century establishments in Scotland Stonehaven Landforms of Aberdeenshire Castles in Aberdeenshire