Czar Alexander I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander I (; – ) was

The Orthodox Church initially exercised little influence on Alexander's life. The young emperor was determined to reform the inefficient, highly centralised systems of government that Russia relied upon. While retaining for a time the old ministers, one of the first acts of his reign was to appoint the Private Committee, comprising young and enthusiastic friends of his own—

The Orthodox Church initially exercised little influence on Alexander's life. The young emperor was determined to reform the inefficient, highly centralised systems of government that Russia relied upon. While retaining for a time the old ministers, one of the first acts of his reign was to appoint the Private Committee, comprising young and enthusiastic friends of his own—

Called an autocrat and "

Called an autocrat and "

Meanwhile, Napoleon, a little deterred by the Russian autocrat's youthful ideology, never gave up hope of detaching him from the coalition. He had no sooner entered

Meanwhile, Napoleon, a little deterred by the Russian autocrat's youthful ideology, never gave up hope of detaching him from the coalition. He had no sooner entered

Events were rapidly heading towards the rupture of the Franco-Russian alliance. While Alexander assisted Napoleon in the war of 1809, he declared plainly that he would not allow the

Events were rapidly heading towards the rupture of the Franco-Russian alliance. While Alexander assisted Napoleon in the war of 1809, he declared plainly that he would not allow the  Relations between France and Russia worsened progressively after 1810. By 1811, it became clear that Napoleon was not adhering to his side of the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit. He had promised assistance to Russia in its war against the Ottoman Empire, but as the campaign went on, France offered no support at all.

With war imminent between France and Russia, Alexander started to prepare the ground diplomatically. In April 1812, Russia and Sweden signed an agreement for mutual defence. A month later, Alexander secured his southern flank through the

Relations between France and Russia worsened progressively after 1810. By 1811, it became clear that Napoleon was not adhering to his side of the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit. He had promised assistance to Russia in its war against the Ottoman Empire, but as the campaign went on, France offered no support at all.

With war imminent between France and Russia, Alexander started to prepare the ground diplomatically. In April 1812, Russia and Sweden signed an agreement for mutual defence. A month later, Alexander secured his southern flank through the

A week later Napoleon entered Moscow, but there was no delegation to meet the Emperor. The Russians had evacuated the city, and the city's governor, Count

A week later Napoleon entered Moscow, but there was no delegation to meet the Emperor. The Russians had evacuated the city, and the city's governor, Count

Camping outside the city on 29 March, the Coalition armies were to assault the city from its northern and eastern sides the next morning on 30 March. The battle started that same morning with intense artillery bombardment from the Coalition positions. Early in the morning the Coalition attack began when the Russians attacked and drove back the French skirmishers near Belleville before being driven back themselves by French cavalry from the city's eastern suburbs. By 7:00 a.m. the Russians attacked the Young Guard near

Camping outside the city on 29 March, the Coalition armies were to assault the city from its northern and eastern sides the next morning on 30 March. The battle started that same morning with intense artillery bombardment from the Coalition positions. Early in the morning the Coalition attack began when the Russians attacked and drove back the French skirmishers near Belleville before being driven back themselves by French cavalry from the city's eastern suburbs. By 7:00 a.m. the Russians attacked the Young Guard near

Once a supporter of limited liberalism, as seen in his approval of the

Once a supporter of limited liberalism, as seen in his approval of the  He still declared his belief in "free institutions, though not in such as age forced from feebleness, nor contracts ordered by popular leaders from their sovereigns, nor constitutions granted in difficult circumstances to tide over a crisis." "Liberty", he maintained, "should be confined within just limits. And the limits of liberty are the principles of order".

It was the apparent triumph of the principles of disorder in the revolutions of

He still declared his belief in "free institutions, though not in such as age forced from feebleness, nor contracts ordered by popular leaders from their sovereigns, nor constitutions granted in difficult circumstances to tide over a crisis." "Liberty", he maintained, "should be confined within just limits. And the limits of liberty are the principles of order".

It was the apparent triumph of the principles of disorder in the revolutions of

At the

At the

File:Death Alexander I of Russia.jpg, Death of Alexander I in Taganrog (19th century lithograph)

File:Alexandre1 Palace Taganrog.jpg,

He received the following orders and decorations:Russian Imperial Army - Emperor Alexander I Pavlovich of Russia

He received the following orders and decorations:Russian Imperial Army - Emperor Alexander I Pavlovich of Russia

(In Russian)

excerpt

* McConnell, Allen. ''Tsar Alexander I: Paternalistic Reformer'' (1970

online free to borrow

* Palmer, Alan. ''Alexander I: Tsar of War and Peace'' (Faber & Faber, 2014). * Rey, Marie-Pierre. ''Alexander I.: the Tsar who defeated Napoleon'' (2012) * Zawadzki, Hubert. "Between Napoleon and Tsar Alexander: The Polish Question at Tilsit, 1807." ''Central Europe'' 7.2 (2009): 110–124.

Emperor of Russia

The emperor or empress of all the Russias or All Russia, ''Imperator Vserossiyskiy'', ''Imperatritsa Vserossiyskaya'' (often titled Tsar or Tsarina/Tsaritsa) was the monarch of the Russian Empire.

The title originated in connection with Russia' ...

from 1801, the first King of Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It ...

from 1815, and the Grand Duke of Finland

Grand Duke of Finland, or, more accurately, the Grand Prince of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinas, sv, Storfurste av Finland, rus, Великий князь Финляндский, r=Velikiy knyaz' Finlyandskiy, p=vʲɪˈlʲikɪj knʲæsʲ f� ...

from 1809 to his death. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I

Paul I (russian: Па́вел I Петро́вич ; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination. Officially, he was the only son of Peter III and Catherine the Great, although Catherine hinted that he was fathered by her l ...

and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg

Sophie is a version of the female given name Sophia, meaning "wise".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Sophie of Thuringia, Duchess o ...

.

The son of Grand Duke Paul Petrovich, later Paul I, Alexander succeeded to the throne after his father was murdered. He ruled Russia during the chaotic period of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. As prince and during the early years of his reign, Alexander often used liberal rhetoric, but continued Russia's absolutist policies in practice. In the first years of his reign, he initiated some minor social reforms and (in 1803–04) major liberal educational reforms, such as building more universities. Alexander appointed Mikhail Speransky

Count Mikhail Mikhailovich Speransky (russian: Михаи́л Миха́йлович Спера́нский; 12 January 1772 – 23 February 1839) was a Russian reformist during the reign of Alexander I of Russia, to whom he was a close advisor. ...

, the son of a village priest, as one of his closest advisors. The Collegia

A (plural ), or college, was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the ''Lex Julia'' during the reign of Julius Caesar as Consul and Dictator of the Roman Republic (49–44 BC), and their reaf ...

were abolished and replaced by the State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of South Korea, headed by the President

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative autho ...

, which was created to improve legislation. Plans were also made to set up a parliament and sign a constitution.

In foreign policy, he changed Russia's position towards France four times between 1804 and 1812 among neutrality, opposition, and alliance. In 1805 he joined Britain in the War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition)

* In French historiography, it is known as the Austrian campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Autriche de 1805) or the German campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Allemagne de 1805) was a European conflict spanni ...

against Napoleon, but after suffering massive defeats at the battles of Austerlitz and Friedland

Friedland may refer to:

Places

Czech Republic

* Frýdlant v Čechách (''Friedland im Isergebirge'')

* Frýdlant nad Ostravicí (''Friedland an der Ostrawitza'')

* Frýdlant nad Moravicí (''Friedland an der Mohra'')

France

* , street in P ...

, he switched sides and formed an alliance with Napoleon by the Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, wh ...

(1807) and joined Napoleon's Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

. He fought a small-scale naval war against Britain between 1807 and 1812 as well as a short war against Sweden (1808–09) after Sweden's refusal to join the Continental System. Alexander and Napoleon hardly agreed, especially regarding Poland, and the alliance collapsed by 1810. Alexander's greatest triumph came in 1812 when Napoleon's invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign, the Second Polish War, the Army of Twenty nations, and the Patriotic War of 1812 was launched by Napoleon Bonaparte to force the Russian Empire back into the continental block ...

proved to be a catastrophic disaster for the French. As part of the winning coalition against Napoleon, he gained territory in Finland and Poland. He formed the Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance (german: Heilige Allianz; russian: Священный союз, ''Svyashchennyy soyuz''; also called the Grand Alliance) was a coalition linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. It was created after ...

to suppress revolutionary movements in Europe which he saw as immoral threats to legitimate Christian monarchs. He also helped Austria's Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

in suppressing all national and liberal movements.

During the second half of his reign, Alexander became increasingly arbitrary, reactionary, and fearful of plots against him; as a result he ended many of the reforms he made earlier. He purged schools of foreign teachers, as education became more religiously driven as well as politically conservative. Speransky was replaced as advisor with the strict artillery inspector Aleksey Arakcheyev

Count Alexey Andreyevich Arakcheyev or Arakcheev (russian: граф Алексе́й Андре́евич Аракче́ев) ( – ) was an Imperial Russian general and statesman during the reign of Tsar Alexander I.

He served under Tsars Paul ...

, who oversaw the creation of military settlements

Military settlements (russian: Военные поселения) represented a special organization of the Russian military forces in 1810–1857, which allowed the combination of military service and agricultural employment.

The beginning of ...

. Alexander died of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

in December 1825 while on a trip to southern Russia. He left no legitimate children, as his two daughters died in childhood. Neither of his brothers wanted to become emperor. After a period of great confusion (that presaged the failed Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

of liberal army officers in the weeks after his death), he was succeeded by his younger brother, Nicholas I.

Early life

Alexander was born at 10:45, on 23 December 1777 inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, and he and his younger brother Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given nam ...

were raised by their grandmother, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

. He was baptized on 31 December in Grand Church of the Winter Palace

The Grand Church of the Winter Palace (russian: Собор Спаса Нерукотворного Образа в Зимнем дворце) in Saint Petersburg, sometimes referred to as the Winter Palace's cathedral, was consecrated in 1763. I ...

by mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in t ...

d archpriest Ioann Ioannovich Panfilov (confessor of Empress Catherine II), his godmother was Catherine the Great and his godfathers were Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 unt ...

and Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

. He was named after Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholic Church, Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocacy, advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, ...

- Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky (russian: Александр Ярославич Невский; ; 13 May 1221 – 14 November 1263) served as Prince of Novgorod (1236–40, 1241–56 and 1258–1259), Grand Prince of Kiev (1236–52) and Grand ...

. Some sources allege that she planned to remove her son (Alexander's father) Paul I from the succession altogether. From the free-thinking atmosphere of the court of Catherine and his Swiss tutor, Frédéric-César de La Harpe, he imbibed the principles of Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

's gospel of humanity. But from his military governor, Nikolay Saltykov, he imbibed the traditions of Russian autocracy. Andrey Afanasyevich Samborsky, whom his grandmother chose for his religious instruction, was an atypical, unbearded Orthodox priest

Presbyter is, in the Bible, a synonym for ''bishop'' (''episkopos''), referring to a leader in local church congregations. In modern Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox usage, it is distinct from ''bishop'' and synonymous with priest. Its li ...

. Samborsky had long lived in England and taught Alexander (and Constantine) excellent English, very uncommon for potential Russian autocrats at the time.

On 9 October 1793, when Alexander was still 15 years old, he married 14-year-old Princess Louise of Baden, who took the name Elizabeth Alexeievna. His grandmother was the one who presided over his marriage to the young princess. Until his grandmother's death, he was constantly walking the line of allegiance between his grandmother and his father. His steward Nikolai Saltykov

Count, then Prince Nikolay Ivanovich Saltykov (russian: Николай Иванович Салтыков, 31 October 1736 – 28 May 1816), a member of the Saltykov noble family, was a Russian Imperial Field Marshal and courtier best known ...

helped him navigate the political landscape, engendering dislike for his grandmother and dread in dealing with his father.

Catherine had the Alexander Palace

The Alexander Palace (russian: Александровский дворец, ''Alexandrovskiy dvorets'') is a former imperial residence near the town of Tsarskoye Selo in Russia, on a plateau about south of Saint Petersburg. The Palace was c ...

built for the couple. This did nothing to help his relationship with her, as Catherine would go out of her way to amuse them with dancing and parties, which annoyed his wife. Living at the palace also put pressure on him to perform as a husband, though he felt only a brother's love for the Grand Duchess. He began to sympathize more with his father, as he saw visiting his father's fiefdom at Gatchina as a relief from the ostentatious court of the empress. There, they wore simple Prussian military uniforms, instead of the gaudy clothing popular at the French court they had to wear when visiting Catherine. Even so, visiting the tsarevich did not come without a bit of travail. Paul liked to have his guests perform military drills, which he also pushed upon his sons Alexander and Constantine. He was also prone to fits of temper, and he often went into fits of rage when events did not go his way.

Tsarevich

Catherine's death in November 1796, before she could appoint Alexander as her successor, brought his father,Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chr ...

, to the throne. Alexander disliked him as emperor even more than he did his grandmother. He wrote that Russia had become a "plaything for the insane" and that "absolute power disrupts everything". It is likely that seeing two previous rulers abuse their autocratic powers in such a way pushed him to be one of the more progressive Romanov tsars of the 19th and 20th centuries. Among the rest of the country, Paul was widely unpopular. He accused his wife of conspiring to become another Catherine and seize power from him as his mother did from his father. He also suspected Alexander of conspiring against him, despite his son's earlier refusal to seize power from Paul.

Emperor

Ascension

Alexander became Emperor of Russia when his father was assassinated 23 March 1801. Alexander, then 23 years old, was in the palace at the moment of the assassination and his accession to the throne was announced by General Nicholas Zubov, one of the assassins. Historians still debate Alexander's role in his father's murder. The most common theory is that he was let into the conspirators' secret and was willing to take the throne but insisted that his father should not be killed. Becoming emperor through a crime that cost his father's life would give Alexander a strong sense of remorse and shame. Alexander I succeeded to the throne on 23 March 1801 and was crowned in theKremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of the kremlins (Ru ...

on 15 September of that year.

Domestic policy

The Orthodox Church initially exercised little influence on Alexander's life. The young emperor was determined to reform the inefficient, highly centralised systems of government that Russia relied upon. While retaining for a time the old ministers, one of the first acts of his reign was to appoint the Private Committee, comprising young and enthusiastic friends of his own—

The Orthodox Church initially exercised little influence on Alexander's life. The young emperor was determined to reform the inefficient, highly centralised systems of government that Russia relied upon. While retaining for a time the old ministers, one of the first acts of his reign was to appoint the Private Committee, comprising young and enthusiastic friends of his own—Viktor Kochubey

Prince Viktor Pavlovich Kochubey (); ( – ) was a Russian statesman and close aide of Alexander I of Russia. Of Ukrainian origin, he was a great-grandson of Vasily Kochubey. He took part in the Privy Committee that outlined Government reform of ...

, Nikolay Novosiltsev

Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev (Novoselcev) (russian: Граф Никола́й Никола́евич Новосельцев (Новоси́льцев), pl, Nikołaj Nowosilcow) (1761–1838) was a Russian statesman and a close aide t ...

, Pavel Stroganov and Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski (; lt, Аdomas Jurgis Čartoriskis; 14 January 177015 July 1861), in English known as Adam George Czartoryski, was a Polish nobleman, statesman, diplomat and author.

The son of a wealthy prince, he began his political c ...

—to draw up a plan of domestic reform, which was supposed to result in the establishment of a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

in accordance with the teachings of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

A few years into his reign the liberal Mikhail Speransky

Count Mikhail Mikhailovich Speransky (russian: Михаи́л Миха́йлович Спера́нский; 12 January 1772 – 23 February 1839) was a Russian reformist during the reign of Alexander I of Russia, to whom he was a close advisor. ...

became one of the emperor's closest advisors, and he drew up many plans for elaborate reforms. In the Government reform of Alexander I

The early Russian system of government instituted by Peter the Great, which consisted of various state committees, each named '' Collegium'' with subordinate departments named '' Prikaz'', was largely outdated by the 19th century. The responsib ...

the old Collegia

A (plural ), or college, was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the ''Lex Julia'' during the reign of Julius Caesar as Consul and Dictator of the Roman Republic (49–44 BC), and their reaf ...

were abolished and new Ministries were created in their place, led by ministers responsible to the Crown. A Council of Ministers under the chairmanship of the Sovereign dealt with all interdepartmental matters. The State Council

The State Council, constitutionally synonymous with the Central People's Government since 1954 (particularly in relation to local governments), is the chief administrative authority of the People's Republic of China. It is chaired by the pr ...

was created to improve the technique of legislation. It was intended to become the Second Chamber of representative legislature. The Governing Senate

The Governing Senate (russian: Правительствующий сенат, Pravitelstvuyushchiy senat) was a legislative, judicial, and executive body of the Russian Emperors, instituted by Peter the Great to replace the Boyar Duma and last ...

was reorganized as the Supreme Court of the Empire. The codification of the laws initiated in 1801 was never carried out during his reign.

Alexander wanted to resolve another crucial issue in Russia, the status of the serfs, although this was not achieved until 1861 (during the reign of his nephew Alexander II). His advisors quietly discussed the options at length. Cautiously, he extended the right to own land to most classes of subjects, including state-owned peasants, in 1801 and created a new social category of "free agriculturalist Free agriculturalists (russian: Во́льные хлебопа́шцы, Свободные хлебопашцы, literally, free ploughmen) were a category of peasants in the Russian Empire in 19th century.

This was the official reference to the ...

," for peasants voluntarily emancipated by their masters, in 1803. The great majority of serfs were not affected.

When Alexander's reign began, there were three universities in Russia, at Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Vilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional ur ...

(Vilnius), and Dorpat

Tartu is the second largest city in Estonia after the Northern European country's political and financial capital, Tallinn. Tartu has a population of 91,407 (as of 2021). It is southeast of Tallinn and 245 kilometres (152 miles) northeast of ...

(Tartu). These were strengthened, and three others were founded at St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering ...

. Literary and scientific bodies were established or encouraged, and his reign became noted for the aid lent to the sciences and arts by the Emperor and the wealthy nobility. Alexander later expelled foreign scholars.

After 1815 the military settlements

Military settlements (russian: Военные поселения) represented a special organization of the Russian military forces in 1810–1857, which allowed the combination of military service and agricultural employment.

The beginning of ...

(farms worked by soldiers and their families under military control) were introduced, with the idea of making the army, or part of it, self-supporting economically and for providing it with recruits.

Views held by his contemporaries

Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

", a man of the world and a mystic, Alexander appeared to his contemporaries as a riddle which each read according to his own temperament. Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

thought him a "shifty Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

", and called him the Talma of the North, as ready to play any conspicuous part. To Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

he was a madman to be humoured. Castlereagh, writing of him to Lord Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He held many important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secreta ...

, gave him credit for "grand qualities", but added that he is "suspicious and undecided"; and to Jefferson he was a man of estimable character, disposed to do good, and expected to diffuse through the mass of the Russian people "a sense of their natural rights". In 1803, Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

dedicated his Opus 30 Violin Sonatas to Alexander who in response gave him a diamond at the Congress of Vienna where they met in 1814.

Napoleonic Wars

Alliances with other powers

Upon his accession, Alexander reversed many of the unpopular policies of his father, Paul, denounced the League of Armed Neutrality, and made peace withBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

(April 1801). At the same time he opened negotiations with Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire. Soon afterwards at Memel he entered into a close alliance with Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, not as he boasted from motives of policy, but in the spirit of true chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

, out of friendship

Friendship is a relationship of mutual affection between people. It is a stronger form of interpersonal bond than an "acquaintance" or an "association", such as a classmate, neighbor, coworker, or colleague.

In some cultures, the concept of ...

for the young King Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, w ...

and his beautiful wife Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Duchess Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Luise Auguste Wilhelmine Amalie; 10 March 1776 – 19 July 1810) was Queen of Prussia as the wife of King Frederick William III. The couple's happy, though short-lived, marriage produced nine chil ...

.

The development of this alliance was interrupted by the short-lived peace of October 1801, and for a while it seemed as though France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Russia might come to an understanding. Carried away by the enthusiasm of Frédéric-César de La Harpe, who had returned to Russia from Paris, Alexander began openly to proclaim his admiration for French institutions and for the person of Napoleon Bonaparte. Soon, however, came a change. La Harpe, after a new visit to Paris, presented to Alexander his ''Reflections on the True Nature of the Consul for Life'', which, as Alexander said, tore the veil from his eyes and revealed Bonaparte "as not a true patriot", but only as "the most famous tyrant the world has produced". Later on, La Harpe and his friend Henri Monod lobbied Alexander, who persuaded the other Allied powers opposing Napoleon to recognise Vaud

Vaud ( ; french: (Canton de) Vaud, ; german: (Kanton) Waadt, or ), more formally the canton of Vaud, is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of ten districts and its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat of arms ...

ois and Argovian independence, in spite of Bern's attempts to reclaim them as ''subject lands''. Alexander's disillusionment was completed by the execution of the duc d'Enghien

Duke of Enghien (french: Duc d'Enghien, pronounced with a silent ''i'') was a noble title pertaining to the House of Condé. It was only associated with the town of Enghien for a short time.

Dukes of Enghien – first creation (1566–1569)

The ...

on trumped up charges. The Russian court went into mourning for the last member of the House of Condé

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

, and diplomatic relations with France were broken off. Alexander was especially alarmed and decided he had to somehow curb Napoleon's power.

Opposition to Napoleon

In opposing Napoleon I, "the oppressor of Europe and the disturber of the world's peace," Alexander in fact already believed himself to be fulfilling a divine mission. In his instructions to Niklolay Novosiltsov, his special envoy in London, the emperor elaborated the motives of his policy in language that appealed little to the prime minister,William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the Un ...

. Yet the document is of great interest, as it formulates for the first time in an official dispatch the ideals of international policy that were to play a conspicuous part in world affairs at the close of the revolutionary epoch. Alexander argued that the outcome of the war was not only to be the liberation of France, but the universal triumph of "the sacred rights of humanity". To attain this it would be necessary "after having attached the nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

s to their government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

by making these incapable of acting save in the greatest interests of their subjects, to fix the relations of the states amongst each other on more precise rules, and such as it is to their interest to respect".

A general treaty was to become the main basis of the relations of the states forming "the European Confederation". While he believed the effort would not attain universal peace, it would be worthwhile if it established clear principles for the prescriptions of the rights of nations. The body would assure "the positive rights of nations" and "the privilege of neutrality," while asserting the obligation to exhaust all resources of mediation to retain peace, and would form "a new code of the law of nations".

1807 loss to French forces

Meanwhile, Napoleon, a little deterred by the Russian autocrat's youthful ideology, never gave up hope of detaching him from the coalition. He had no sooner entered

Meanwhile, Napoleon, a little deterred by the Russian autocrat's youthful ideology, never gave up hope of detaching him from the coalition. He had no sooner entered Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

in triumph than he opened negotiations with Alexander; he resumed them after the Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz i ...

(2 December). Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

and France, he urged, were "geographical allies"; there was, and could be, between them no true conflict of interests; together they might rule the world. But Alexander was still determined "to persist in the system of disinterestedness in respect of all the states of Europe which he had thus far followed", and he again allied himself with the Kingdom of Prussia. The campaign of Jena and the battle of Eylau

The Battle of Eylau, or Battle of Preussisch-Eylau, was a bloody and strategically inconclusive battle on 7 and 8 February 1807 between Napoléon's ''Grande Armée'' and the Imperial Russian Army under the command of Levin August von Bennig ...

followed; and Napoleon, though still intent on the Russian alliance, stirred up Poles, Turks and Persians to break the obstinacy of the Tsar. A party too in Russia itself, headed by the Tsar's brother Constantine Pavlovich, was clamorous for peace; but Alexander, after a vain attempt to form a new coalition, summoned the Russian nation to a holy war against Napoleon as the enemy of the Orthodox faith. The outcome was the rout of Friedland (13/14 June 1807). Napoleon saw his chance and seized it. Instead of making heavy terms, he offered to the chastened autocrat his alliance, and a partnership in his glory.

The two Emperors met at Tilsit

Sovetsk (russian: Сове́тск; german: Tilsit; Old Prussian: ''Tilzi''; lt, Tilžė; pl, Tylża) is a town in Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the south bank of the Neman River which forms the border with Lithuania.

Geography

...

on 25 June 1807. Napoleon knew well how to appeal to the exuberant imagination of his new-found friend. He would divide with Alexander the Empire of the world; as a first step he would leave him in possession of the Danubian

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

principalities and give him a free hand to deal with Finland; and, afterwards, the Emperors of the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, when the time should be ripe, would drive the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

from Europe and march across Asia to the conquest of India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, a realization of which was finally achieved by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

a few years later, and would change the course of modern history. Nevertheless, a thought awoke in Alexander's impressionable mind an ambition to which he had hitherto been a stranger. The interests of Europe as a whole were utterly forgotten.

Prussia

The brilliance of these new visions did not, however, blind Alexander to the obligations of friendship, and he refused to retain theDanubian principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th ce ...

as the price for suffering a further dismemberment of Prussia. "We have made loyal war", he said, "we must make a loyal peace". It was not long before the first enthusiasm of Tilsit began to wane. The French remained in Prussia, the Russians on the Danube, and each accused the other of breach of faith. Meanwhile, however, the personal relations of Alexander and Napoleon were of the most cordial character, and it was hoped that a fresh meeting might adjust all differences between them. The meeting took place at Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits ...

in October 1808 and resulted in a treaty that defined the common policy of the two Emperors. But Alexander's relations with Napoleon nonetheless suffered a change. He realised that in Napoleon sentiment never got the better of reason, that as a matter of fact he had never intended his proposed "grand enterprise" seriously, and had only used it to preoccupy the mind of the Tsar while he consolidated his own power in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

. From this moment the French alliance was for Alexander also not a fraternal agreement to rule the world, but an affair of pure policy. He used it initially to remove "the geographical enemy" from the gates of Saint Petersburg by wresting Finland from Sweden (1809), and he hoped further to make the Danube the southern frontier of Russia.

Franco-Russian alliance

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

to be crushed out of existence. Napoleon subsequently complained bitterly of the inactivity of the Russian troops during the campaign. The tsar in turn protested against Napoleon's encouragement of the Poles. In the matter of the French alliance he knew himself to be practically isolated in Russia, and he declared that he could not sacrifice the interest of his people and empire to his affection for Napoleon. "I don't want anything for myself", he said to the French ambassador, "therefore the world is not large enough to come to an understanding on the affairs of Poland, if it is a question of its restoration".

Alexander complained that the Treaty of Vienna, which added largely to the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

, had "ill requited him for his loyalty", and he was only mollified for the time being by Napoleon's public declaration that he had no intention of restoring Poland, and by a convention, signed on 4 January 1810, but not ratified, abolishing the Polish name and orders of chivalry.

But if Alexander suspected Napoleon's intentions, Napoleon was no less suspicious of Alexander. Partly to test his sincerity, Napoleon sent an almost peremptory request for the hand of the grand-duchess Anna Pavlovna, the tsar's youngest sister. After some little delay Alexander returned a polite refusal, pleading the princess's tender age and the objection of the dowager empress to the marriage. Napoleon's answer was to refuse to ratify the 4 January convention, and to announce his engagement to the archduchess Marie Louise in such a way as to lead Alexander to suppose that the two marriage treaties had been negotiated simultaneously. From this time on, the relationship between the two emperors gradually became more and more strained.

Another personal grievance for Alexander towards Napoleon was the annexation of Oldenburg by France in December 1810, as the Duke of Oldenburg (3 January 17542 July 1823) was the uncle of the tsar. Furthermore, the disastrous impact of the Continental System on Russian trade made it impossible for the emperor to maintain a policy that was Napoleon's chief motive for the alliance.

Alexander kept Russia as neutral as possible in the ongoing French war with Britain. He did, however, allow trade to continue secretly with Britain and did not enforce the blockade required by the Continental System. In 1810, he withdrew Russia from the Continental System and trade between Britain and Russia grew.

Relations between France and Russia worsened progressively after 1810. By 1811, it became clear that Napoleon was not adhering to his side of the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit. He had promised assistance to Russia in its war against the Ottoman Empire, but as the campaign went on, France offered no support at all.

With war imminent between France and Russia, Alexander started to prepare the ground diplomatically. In April 1812, Russia and Sweden signed an agreement for mutual defence. A month later, Alexander secured his southern flank through the

Relations between France and Russia worsened progressively after 1810. By 1811, it became clear that Napoleon was not adhering to his side of the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit. He had promised assistance to Russia in its war against the Ottoman Empire, but as the campaign went on, France offered no support at all.

With war imminent between France and Russia, Alexander started to prepare the ground diplomatically. In April 1812, Russia and Sweden signed an agreement for mutual defence. A month later, Alexander secured his southern flank through the Treaty of Bucharest (1812)

The Treaty of Bucharest between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, was signed on 28 May 1812, in Manuc's Inn in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, indu ...

, which ended the war against the Ottomans formally. His diplomats managed to extract promises from Prussia and Austria that should Napoleon invade Russia, the former would help Napoleon as little as possible and that the latter would give no aid at all.

The minister of war, Barclay de Tolly, had managed the reform and improvement of the Russian land forces before the start of the 1812 campaign. Primarily on the advice of his sister and Count Aleksey Arakcheyev

Count Alexey Andreyevich Arakcheyev or Arakcheev (russian: граф Алексе́й Андре́евич Аракче́ев) ( – ) was an Imperial Russian general and statesman during the reign of Tsar Alexander I.

He served under Tsars Paul ...

, Alexander did not take operational control as he had done during the 1805 campaign, instead delegating control to his generals, Michael Barclay de Tolly, Prince Pyotr Bagration

Prince Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration (10 July 1765 – 24 September 1812) was a Georgian general and prince serving in the Russian Empire, prominent during the Napoleonic Wars.

Bagration, a member of the Bagrationi dynasty, was born in Tbilisi. His ...

and Mikhail Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov ( rus, Князь Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов, Knyaz' Mikhaíl Illariónovich Goleníshchev-Kutúzov; german: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kut ...

.

War against Persia

Despite brief hostilities in the Persian Expedition of 1796, eight years of peace passed before a new conflict erupted between the two empires. After the Russian annexation of Georgia in 1801, a subject ofPersia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

for centuries, and the incorporation of the Derbent khanate

The Derbent Khanate ( fa, خانات دربند, Khānāt-e Darband; az, Dərbənd Xanlığı) was a Caucasian khanate that was established in Afsharid Iran. It corresponded to southern Dagestan and its center was at Derbent.

History

Large part ...

as well quickly thereafter, Alexander was determined to increase and maintain Russian influence in the strategically valuable Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

region. In 1801, Alexander appointed Pavel Tsitsianov

Prince Pavel Dmitriyevich Tsitsianov (russian: Павел Дмитриевич Цицианов), also known as Pavle Dimitris dze Tsitsishvili ( ka, პავლე ციციშვილი; —) was a Georgian nobleman and a prominent genera ...

, a die-hard Russian imperialist of Georgian origin, as Russian commander in chief of the Caucasus. Between 1802 and 1804 he proceeded to impose Russian rule on Western Georgia and some of the Persian controlled khanates around Georgia. Some of these khanates submitted without a fight, but the Ganja Khanate

The Ganja Khanate ( fa, خانات گنجه, translit=Khānāt-e Ganjeh, az, گنجه خنليغى, translit=Gəncə xanlığı, ) was a semi-independent Caucasian khanate that was established in Afsharid Iran and existed in the territory of ...

resisted, prompting an attack. Ganja was ruthlessly sacked during the siege of Ganja, with some 3,000

7,000

inhabitants of Ganja executed, and thousands more expelled to Persia. These attacks by Tsitsianov formed another casus belli.

On 23 May 1804, Persia demanded withdrawal from the regions Russia had occupied, comprising what is now Georgia, Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, Дагеста́н, , dəɡʲɪˈstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н, Respúblika Dagestán, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North ...

, and parts of Azerbaijan. Russia refused, stormed Ganja, and declared war. Following an almost ten-year stalemate centred around what is now Dagestan, east Georgia, Azerbaijan, northern Armenia, with neither party being able to gain the clear upper hand, Russia eventually managed to turn the tide. After a series of successful offensives led by General Pyotr Kotlyarevsky

Pyotr Stepanovich Kotlyarevsky (23 June 1782 – 2 November 1852) was a Russian military hero of the early 19th century.

Biography

He was born in the village of Olkhovatka near Kharkiv into a cleric's family. Kotlyarevsky was brought up in an i ...

, including a decisive victory in the storming of Lankaran

The siege of Lankaran ( fa, یورش به لنکران — ; russian: Штурм Ленкорани) took place on 1 January 1813 as part of the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813). The siege was noted for its bitterness and cruelty.

After a sie ...

, Persia was forced to sue for peace. In October 1813, the Treaty of Gulistan

The Treaty of Gulistan (russian: Гюлистанский договор; fa, عهدنامه گلستان) was a peace treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and Iran on 24 October 1813 in the village of Gulistan (now in the Goranboy Distr ...

, negotiated with British mediation and signed at Gulistan, made the Persian Shah Fath Ali Shah

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar ( fa, فتحعلىشاه قاجار, Fatḥ-ʻAli Šâh Qâjâr; May 1769 – 24 October 1834) was the second Shah (king) of Qajar Iran. He reigned from 17 June 1797 until his death on 24 October 1834. His reign saw the irr ...

cede all Persian territories in the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

and most of its territories in the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

to Russia. This included what is now Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, Дагеста́н, , dəɡʲɪˈstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н, Respúblika Dagestán, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North ...

, Georgia, and most of Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

. It also began a large demographic shift in the Caucasus, as many Muslim families emigrated to Persia

French invasion

In the summer of 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia. It was the occupation ofMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

and the desecration of the Kremlin, considered to be the sacred centre of Holy Russia, that changed Alexander's sentiment for Napoleon into passionate hatred. The campaign of 1812 was the turning point for Alexander's life; after the burning of Moscow, he declared that his own soul had found illumination, and that he had realized once and for all the divine revelation to him of his mission as the peacemaker of Europe.

While the Russian army retreated deep into Russia for almost three months, the nobility pressured Alexander to relieve the commander of the Russian army, Field Marshal Barclay de Tolly

Barclay de Tolly () is the name of a Baltic German noble family of Scottish origin ( Clan Barclay). During the time of the Revolution of 1688 in Britain, the family migrated to Swedish Livonia from Towy ( Towie) in Aberdeenshire. Its subseque ...

. Alexander complied and appointed Prince Mikhail Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov ( rus, Князь Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов, Knyaz' Mikhaíl Illariónovich Goleníshchev-Kutúzov; german: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kut ...

to take over command of the army. On 7 September, the Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

faced the Russian army at a small village called Borodino

The Battle of Borodino (). took place near the village of Borodino on during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. The ' won the battle against the Imperial Russian Army but failed to gain a decisive victory and suffered tremendous losses. Napoleo ...

, west of Moscow. The battle that followed was the largest and bloodiest single-day action of the Napoleonic Wars, involving more than 250,000 soldiers and resulting in 70,000 casualties. The outcome of the battle was inconclusive. The Russian army, undefeated in spite of heavy losses, was able to withdraw the following day, leaving the French without the decisive victory Napoleon sought.

A week later Napoleon entered Moscow, but there was no delegation to meet the Emperor. The Russians had evacuated the city, and the city's governor, Count

A week later Napoleon entered Moscow, but there was no delegation to meet the Emperor. The Russians had evacuated the city, and the city's governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin

Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin (russian: Фёдор Васильевич Ростопчин) ( – ) was a Russian statesman and General of the Infantry who served as the Governor-General of Moscow during the French invasion of Russia ...

, ordered several strategic points in Moscow to be set ablaze. The loss of Moscow did not compel Alexander to sue for peace. After staying in the city for a month, Napoleon moved his army out southwest toward Kaluga, where Kutuzov was encamped with the Russian army. The French advance toward Kaluga was checked by the Russian army, and Napoleon was forced to retreat to the areas already devastated by the invasion. In the weeks that followed the starved and suffered from the onset of the Russian Winter

Russian Winter, sometimes personified as "General Frost" or "General Winter", is an aspect of the climate of Russia that has contributed to military failures of several invasions of Russia. Mud is a related contributing factor that impairs mili ...

. Lack of food and fodder for the horses and persistent attacks upon isolated troops from Russian peasants and Cossacks led to great losses. When the remnants of the French army eventually crossed the Berezina River in November, only 27,000 soldiers remained; the had lost some 380,000 men dead and 100,000 captured. Following the crossing of the Berezina, Napoleon left the army and returned to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

to protect his position as Emperor and to raise more forces to resist the advancing Russians. The campaign ended on 14 December 1812, with the last French troops finally leaving Russian soil.

The campaign was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Napoleon's reputation was severely shaken, and French hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

in Europe was weakened. The , made up of French and allied forces, was reduced to a fraction of its initial strength. These events triggered a major shift in European politics. France's ally Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, soon followed by Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, broke their imposed alliance with Napoleon and switched sides, triggering the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, and a number of German States defeated ...

.

War of the Sixth Coalition

With the Russian army following up victory over Napoleon in 1812, the Sixth Coalition was formed with Russia, Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, Sweden, Spain, and other nations. Although the French were victorious in the initial battles during the campaign in Germany, they were eventually defeated at theBattle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig (french: Bataille de Leipsick; german: Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, ); sv, Slaget vid Leipzig), also known as the Battle of the Nations (french: Bataille des Nations; russian: Битва народов, translit=Bitva ...

in the autumn of 1813, which proved to be a decisive victory. Following the battle, the Pro-French Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria a ...

collapsed, thereby losing Napoleon's hold on territory east of the Rhine

The Rhine ; french: Rhin ; nl, Rijn ; wa, Rén ; li, Rien; rm, label=Sursilvan, Rein, rm, label=Sutsilvan and Surmiran, Ragn, rm, label=Rumantsch Grischun, Vallader and Puter, Rain; it, Reno ; gsw, Rhi(n), including in Alsatian dialect, Al ...

. Alexander, being the supreme commander of the Coalition forces in the theatre and the paramount monarch among the three main Coalition monarchs, ordered all Coalition forces in Germany to cross the Rhine and invade France.

The Coalition forces, divided into three groups, entered northeastern France in January 1814. Facing them in the theatre were the French forces numbering only about 70,000 men. In spite of being heavily outnumbered, Napoleon defeated the divided Coalition forces in the battles at Brienne

The County of Brienne was a medieval county in France centered on Brienne-le-Château.

Counts of Brienne

* Engelbert I

* Engelbert II

* Engelbert III

* Engelbert IV

* Walter I (? – c. 1090)

* Erard I (c. 1090 – c. 1120?)

* Walter I ...

and La Rothière

La Rothière () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France.

Population

See also

* Communes of the Aube department

*Parc naturel régional de la Forêt d'Orient

Orient Forest Regional Natural Park ( French: ''Parc natur ...

, but could not stop the Coalition's advance. Austrian emperor Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe ...

and King Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

felt demoralized upon hearing about Napoleon's victories since the start of the campaign. They even considered ordering a general retreat. But Alexander was far more determined than ever to victoriously enter Paris whatever the cost, imposing his will upon Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg

Karl Philipp, Fürst zu Schwarzenberg (or Charles Philip, Prince of Schwarzenberg; 18/19 April 1771 – 15 October 1820) was an Austrian Generalissimo. He fought in the Battle of Wagram (1809) but the Austrians lost decisively against Napol ...

, and the wavering monarchs. On 28 March, Coalition forces advanced towards Paris, and the city surrendered on 31 March. Until this battle it had been nearly 400 years since a foreign army had entered Paris, during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantag ...

.

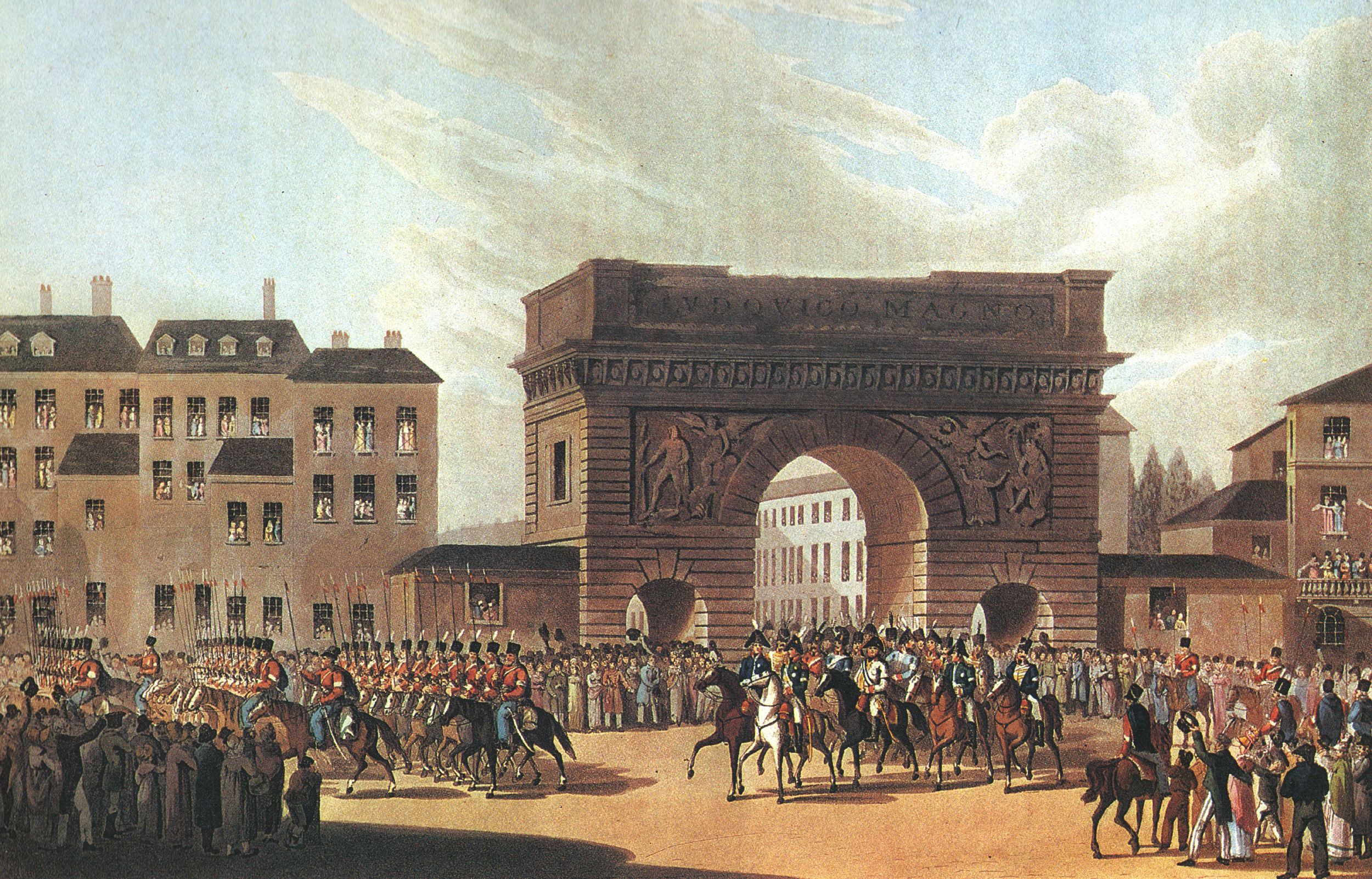

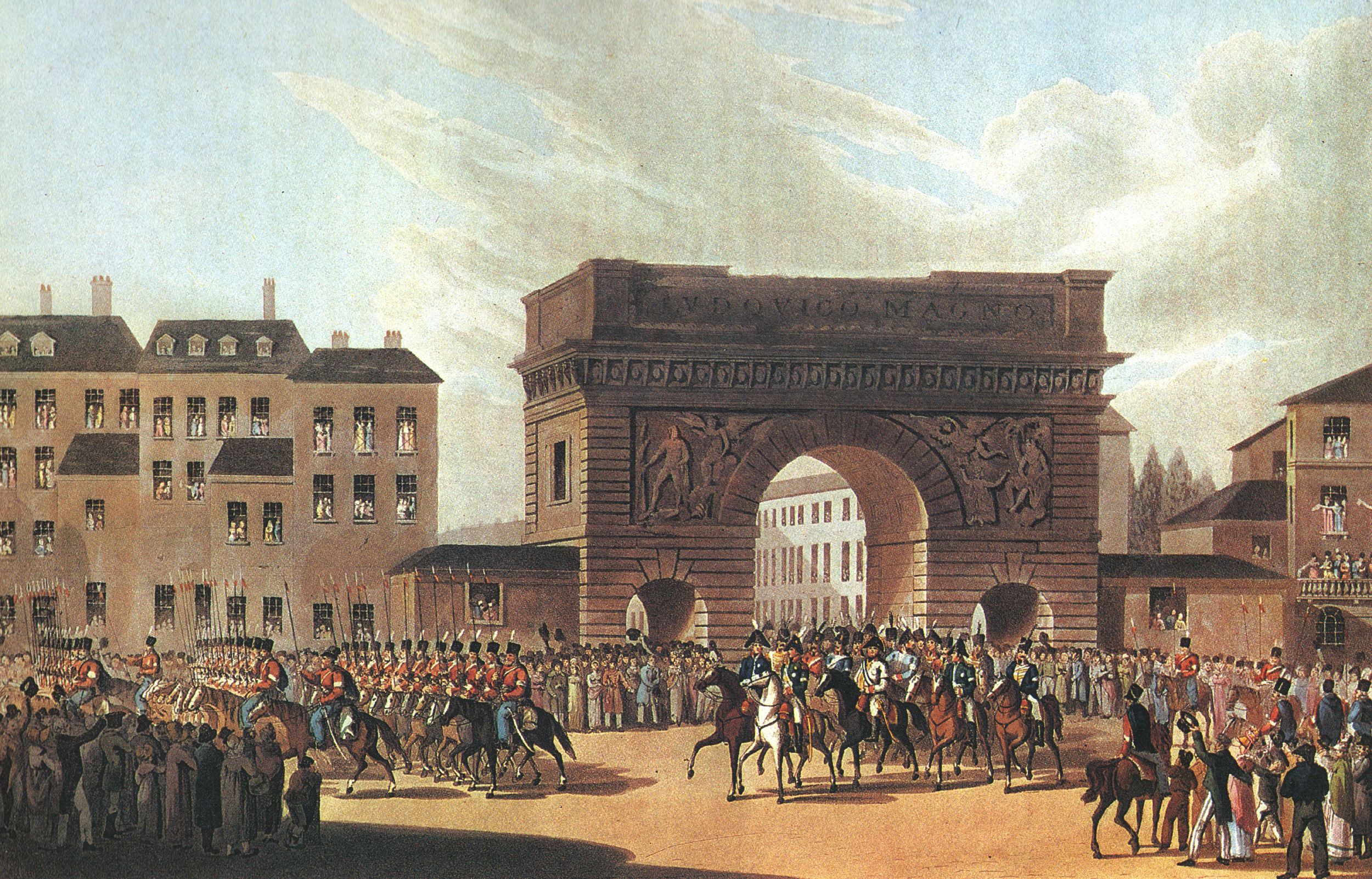

Camping outside the city on 29 March, the Coalition armies were to assault the city from its northern and eastern sides the next morning on 30 March. The battle started that same morning with intense artillery bombardment from the Coalition positions. Early in the morning the Coalition attack began when the Russians attacked and drove back the French skirmishers near Belleville before being driven back themselves by French cavalry from the city's eastern suburbs. By 7:00 a.m. the Russians attacked the Young Guard near

Camping outside the city on 29 March, the Coalition armies were to assault the city from its northern and eastern sides the next morning on 30 March. The battle started that same morning with intense artillery bombardment from the Coalition positions. Early in the morning the Coalition attack began when the Russians attacked and drove back the French skirmishers near Belleville before being driven back themselves by French cavalry from the city's eastern suburbs. By 7:00 a.m. the Russians attacked the Young Guard near Romainville

Romainville () is a commune in the Seine-Saint-Denis department and in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France.

Location

It is located from the center of Paris.

History

On 24 July 1867, a part of the territory of Romainville was detached and me ...

in the centre of the French lines and after some time and hard fighting, pushed them back. A few hours later the Prussians, under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt (; 21 December 1742 – 12 September 1819), ''Graf'' (count), later elevated to ''Fürst'' (sovereign prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Kingdom of Prussia, Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (field ...

, attacked north of the city and carried the French position around Aubervilliers

Aubervilliers () is a commune in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, Île-de-France region, northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Albertivillariens'' or ''Albertivillariennes''.

Geography

Locali ...

, but did not press their attack. The Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Wür ...

troops seized the positions at Saint-Maur to the southwest, with Austrian troops in support. The Russian forces then assailed the heights of Montmartre

Montmartre ( , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Right Bank. The historic district established by the City of Paris in 1995 is bordered by Rue C ...

in the city's northeast. Control of the heights was severely contested, until the French forces surrendered.

Alexander sent an envoy to meet with the French to hasten the surrender. He offered generous terms to the French and although having intended to avenge Moscow, he declared himself to be bringing peace to France rather than its destruction. On 31 March Talleyrand gave the key of the city to the tsar. Later that day the Coalition armies triumphantly entered the city with Alexander at the head of the army followed by the King of Prussia and Prince Schwarzenberg. On 2 April, the Senate passed the '' Acte de déchéance de l'Empereur'', which declared Napoleon deposed. Napoleon was in Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissement ...

when he heard that Paris had surrendered. Outraged, he wanted to march on the capital, but his marshals refused to fight for him and repeatedly urged him to surrender. He abdicated in favour of his son on 4 April, but the Allies rejected this out of hand, forcing Napoleon to abdicate unconditionally on 6 April. The terms of his abdication, which included his exile to the Isle of Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National ...

, were settled in the Treaty of Fontainebleau on 11 April. A reluctant Napoleon ratified it two days later, marking the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, and a number of German States defeated ...

.

Postbellum

Peace of Paris and the Congress of Vienna

Alexander tried to calm the unrest of his conscience by correspondence with the leaders of the evangelical revival on the continent, and sought for omens and supernatural guidance in texts and passages of scripture. It was not, however, according to his own account, until he met the Baroness de Krüdener—a religious adventuress who made the conversion of princes her special mission—atBasel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

, in the autumn of 1813, that his soul found peace. From this time a mystic pietism became the avowed force of his political, as of his private actions. Madame de Krüdener, and her colleague, the evangelist Henri-Louis Empaytaz, became the confidants of the emperor's most secret thoughts; and during the campaign that ended in the occupation of Paris the imperial prayer-meetings were the oracle on whose revelations hung the fate of the world.

Such was Alexander's mood when the downfall of Napoleon left him one of the most powerful sovereigns in Europe. With the memory of the treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, wh ...

still fresh in men's minds, it was not unnatural that to cynical men of the world like Klemens Wenzel von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

he merely seemed to be disguising "under the language of evangelical abnegation" vast and perilous schemes of ambition. The puzzled powers were, in fact, the more inclined to be suspicious in view of other, and seemingly inconsistent, tendencies of the emperor, which yet seemed all to point to a like disquieting conclusion. For Madame de Krüdener was not the only influence behind the throne; and, though Alexander had declared war against the Revolution, La Harpe (his erstwhile tutor) was once more at his elbow, and the catchwords of the gospel of humanity were still on his lips. The very proclamations which denounced Napoleon as "the genius of evil", denounced him in the name of "liberty," and of "enlightenment". Conservatives suspected Alexander of a monstrous intrigue by which the eastern autocrat would ally with the Jacobinism of all Europe, aiming at an all-powerful Russia in place of an all-powerful France. At the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

Alexander's attitude accentuated this distrust. Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, (18 June 1769 – 12 August 1822), usually known as Lord Castlereagh, derived from the courtesy title Viscount Castlereagh ( ) by which he was styled from 1796 to 1821, was an Anglo-Irish politician ...

, whose single-minded aim was the restoration of "a just equilibrium" in Europe, reproached the Tsar to his face for a "conscience" which led him to imperil the concert of the powers by keeping his hold on Poland in violation of his treaty obligation.

Liberal political views

Once a supporter of limited liberalism, as seen in his approval of the

Once a supporter of limited liberalism, as seen in his approval of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Konstytucja Królestwa Polskiego) was granted to the 'Congress' Kingdom of Poland by King of Poland Alexander I of Russia in 1815, who was obliged to issue a constitution to the newly recreated Pol ...

in 1815, from the end of the year 1818 Alexander's views began to change. A revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

ary conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

among the officers of the guard, and a plot to kidnap him on his way to the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle, are said to have shaken his liberal beliefs. At Aix he came for the first time into intimate contact with Metternich. From this time dates the ascendancy of Metternich over the mind of the Russian Emperor and in the councils of Europe. It was, however, no case of sudden conversion. Though alarmed by the revolutionary agitation in Germany, which culminated in the murder of his agent, the dramatist August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue (; – ) was a German dramatist and writer who also worked as a consul in Russia and Germany.

In 1817, one of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl L ...

(23 March 1819), Alexander approved of Castlereagh's protest against Metternich's policy of "the governments contracting an alliance against the peoples", as formulated in the Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

of July 1819, and deprecated any intervention of Europe to support "a league of which the sole object is the absurd pretensions of "absolute power".

He still declared his belief in "free institutions, though not in such as age forced from feebleness, nor contracts ordered by popular leaders from their sovereigns, nor constitutions granted in difficult circumstances to tide over a crisis." "Liberty", he maintained, "should be confined within just limits. And the limits of liberty are the principles of order".

It was the apparent triumph of the principles of disorder in the revolutions of

He still declared his belief in "free institutions, though not in such as age forced from feebleness, nor contracts ordered by popular leaders from their sovereigns, nor constitutions granted in difficult circumstances to tide over a crisis." "Liberty", he maintained, "should be confined within just limits. And the limits of liberty are the principles of order".

It was the apparent triumph of the principles of disorder in the revolutions of Naples