Cuon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The dhole ( ; ''Cuon alpinus'') is a

''Canis alpinus'' was the

''Canis alpinus'' was the

The dhole's general tone of the fur is reddish, with the brightest hues occurring in winter. In the winter coat, the back is clothed in a saturated rusty-red to reddish colour with brownish highlights along the top of the head, neck and shoulders. The throat, chest, flanks, and belly and the upper parts of the limbs are less brightly coloured, and are more yellowish in tone. The lower parts of the limbs are whitish, with dark brownish bands on the anterior sides of the forelimbs. The muzzle and forehead are greyish-reddish. The tail is very luxuriant and fluffy, and is mainly of a reddish-ocherous colour, with a dark brown tip. The summer coat is shorter, coarser and darker. The dorsal and lateral

The dhole's general tone of the fur is reddish, with the brightest hues occurring in winter. In the winter coat, the back is clothed in a saturated rusty-red to reddish colour with brownish highlights along the top of the head, neck and shoulders. The throat, chest, flanks, and belly and the upper parts of the limbs are less brightly coloured, and are more yellowish in tone. The lower parts of the limbs are whitish, with dark brownish bands on the anterior sides of the forelimbs. The muzzle and forehead are greyish-reddish. The tail is very luxuriant and fluffy, and is mainly of a reddish-ocherous colour, with a dark brown tip. The summer coat is shorter, coarser and darker. The dorsal and lateral

Historically, the dhole lived in

Historically, the dhole lived in

Dholes are far less

Dholes are far less

In India, the

In India, the

Once large prey is caught, one dhole grabs the prey's nose, while the rest of the pack pulls the animal down by the flanks and hindquarters. They do not use a killing bite to the throat. They occasionally blind their prey by attacking the eyes.

Once large prey is caught, one dhole grabs the prey's nose, while the rest of the pack pulls the animal down by the flanks and hindquarters. They do not use a killing bite to the throat. They occasionally blind their prey by attacking the eyes.

Like African wild dogs, but unlike wolves, dholes are not known to actively hunt people. They are known to eat

Like African wild dogs, but unlike wolves, dholes are not known to actively hunt people. They are known to eat

In some areas, dholes are

In some areas, dholes are

Dhole Home PageArchive

*ARKive �

images and movies of the dholeSaving the dhole: The forgotten 'badass' Asian dog more endangered than tigers

''The Guardian'' (25 June 2015)

Photos of dhole in Bandipur

{{Authority control Canina (subtribe) Taxa named by Peter Simon Pallas Mammals described in 1811 Carnivorans of Asia Mammals of South Asia Mammals of Southeast Asia Endangered fauna of Asia Pleistocene mammals of Asia Extant Middle Pleistocene first appearances Species that are or were threatened by habitat fragmentation Endangered Fauna of China

canid

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a family (biology), biological family of caniform carnivorans, constituting a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). The family includes three subfamily, subfamilies: the Caninae, a ...

native to South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

. It is anatomically distinguished from members of the genus ''Canis

''Canis'' is a genus of the Caninae which includes multiple extant taxon, extant species, such as Wolf, wolves, dogs, coyotes, and golden jackals. Species of this genus are distinguished by their moderate to large size, their massive, well-develo ...

'' in several aspects: its skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

is convex rather than concave in profile, it lacks a third lower molar, and the upper molars possess only a single cusp

A cusp is the most pointed end of a curve. It often refers to cusp (anatomy), a pointed structure on a tooth.

Cusp or CUSP may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Cusp (singularity), a singular point of a curve

* Cusp catastrophe, a branch of bifu ...

as opposed to between two and four. During the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, the dhole ranged throughout Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, with its range also extending into Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

(with a single putative, controversial record also reported from North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

) but became restricted to its historical range 12,000–18,000 years ago. It is now extinct in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, parts of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, and possibly the Korean peninsula

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically divided at or near the 38th parallel between North Korea (Dem ...

and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

.

Genetic evidence indicates that the dhole was the result of reticulate evolution

Reticulate evolution, or network evolution is the origination of a lineage through the partial merging of two ancestor lineages, leading to relationships better described by a phylogenetic network than a bifurcating tree. Reticulate patterns can ...

, emerging from the hybridization between a species closely related to genus ''Canis'' and one from a lineage closely related to the African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called painted dog and Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lycaon'', which is disti ...

(''Lycaon pictus'').

The dhole is a highly social animal, living in large clans without rigid dominance hierarchies

In the zoological field of ethology, a dominance hierarchy (formerly and colloquially called a pecking order) is a type of social hierarchy that arises when members of animal social groups interact, creating a ranking system. Different types of ...

and containing multiple breeding females. Such clans usually consist of about 12 individuals, but groups of over 40 are known. It is a diurnal pack hunter which preferentially targets large and medium-sized ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s. In tropical forests, the dhole competes with the tiger

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is a large Felidae, cat and a member of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Asia. It has a powerful, muscular body with a large head and paws, a long tail and orange fur with black, mostly vertical stripes. It is ...

(''Panthera tigris'') and the leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant cat species in the genus ''Panthera''. It has a pale yellowish to dark golden fur with dark spots grouped in rosettes. Its body is slender and muscular reaching a length of with a ...

(''Panthera pardus''), targeting somewhat different prey species, but still with substantial dietary overlap.

It is listed as Endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, inv ...

on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

, as populations are decreasing and estimated to comprise fewer than 2,500 mature individuals. Factors contributing to this decline include habitat loss, loss of prey, competition with other species, persecution due to livestock predation, and disease transfer from domestic dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers ...

s.

Etymology and naming

Theetymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

of "dhole" is unclear. The possible earliest written use of the word in English occurred in 1808 by soldier Thomas Williamson, who encountered the animal in Ramghur district, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. He stated that ''dhole'' was a common local name for the species. In 1827, Charles Hamilton Smith

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Hamilton Smith, Royal Guelphic Order, KH, Military Order of William, KW, Royal Society, FRS, Linnean Society of London, FLS (26 December 1776 – 21 September 1859) was a British Army officer, artist, naturalist, ant ...

claimed that it was derived from a language spoken in 'various parts of the East'.

Two years later, Smith connected this word with 'mad, crazy', and erroneously compared the Turkish word with and (cfr. also ; ), which are in fact from the Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

*''dwalaz'' 'foolish, stupid'. Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

wrote nearly 80 years later that the word was not used by the natives living within the species' range. The Merriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster, Incorporated is an list of companies of the United States by state, American company that publishes reference work, reference books and is mostly known for Webster's Dictionary, its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary pub ...

''Dictionary'' theorises that it may have come from the .

Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog, Indian wild dog, whistling dog, red dog, and red wolf.

Taxonomy and evolution

''Canis alpinus'' was the

''Canis alpinus'' was the binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

proposed by Peter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (22 September 1741 – 8 September 1811) was a Prussia, Prussian zoologist, botanist, Ethnography, ethnographer, Exploration, explorer, Geography, geographer, Geology, geologist, Natura ...

in 1811, who described its range as encompassing the upper levels of Udskoi Ostrog in Amurland, towards the eastern side and in the region of the upper Lena River

The Lena is a river in the Russian Far East and is the easternmost river of the three great rivers of Siberia which flow into the Arctic Ocean, the others being Ob (river), Ob and Yenisey. The Lena River is long and has a capacious drainage basi ...

, around the Yenisei River and occasionally crossing into China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. This northern Russian range reported by Pallas during the 18th and 19th centuries is "considerably north" of where this species occurs today.

''Canis primaevus'' was a name proposed by Brian Houghton Hodgson

Brian Houghton Hodgson (1 February 1801 – 23 May 1894) was a pioneer natural history, naturalist and ethnologist working in India and Nepal where he was a British Resident (title), Resident. He described numerous species of birds and mammals fr ...

in 1833 who thought that the dhole was a primitive ''Canis'' form and the progenitor

In genealogy, a progenitor (rarer: primogenitor; or ''Ahnherr'') is the founder (sometimes one that is legendary) of a family, line of descent, gens, clan, tribe, noble house, or ethnic group.. Ebenda''Ahnherr:''"Stammvater eines Geschlec ...

of the domestic dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers ...

. Hodgson later took note of the dhole's physical distinctiveness from the genus ''Canis'' and proposed the genus ''Cuon''.

The first study on the origins of the species was conducted by paleontologist Erich Thenius, who concluded in 1955 that the dhole was a post-Pleistocene descendant of a golden jackal-like ancestor. The paleontologist Bjorn Kurten wrote in his 1968 book ''Pleistocene Mammals of Europe'' that the primitive dhole ''Canis majori'' Del Campana 1913 —the remains of which have been found in Villafranchian

Villafranchian age ( ) is a period of geologic time (3.5–1.0 Ma) spanning the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene used more specifically with European Land Mammal Ages. Named by Italian geologist Lorenzo Pareto for a sequence of terrestrial se ...

era Valdarno

The Valdarno is the valley of the river Arno, from Florence to the sea. The name applies to the entire river basin, though usage of the term generally excludes Casentino and the valleys formed by major tributaries.

Some towns in the area:

* R ...

, Italy and in China—was almost indistinguishable from the genus ''Canis''. In comparison, the modern species has greatly reduced molars and the cusp

A cusp is the most pointed end of a curve. It often refers to cusp (anatomy), a pointed structure on a tooth.

Cusp or CUSP may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Cusp (singularity), a singular point of a curve

* Cusp catastrophe, a branch of bifu ...

s have developed into sharply trenchant points. During the Early Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, more widely known as the Middle Pleistocene (its previous informal name), is an Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale or a Stage (stratigraphy), stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocen ...

there arose both ''Canis majori stehlini'' that was the size of a large wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a Canis, canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of Canis lupus, subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, includin ...

, and the early dhole ''Canis alpinus'' Pallas 1811 which first appeared at Hundsheim and Mosbach

Mosbach (; South Franconian: ''Mossbach'') is a town in the north of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is the seat of the Neckar-Odenwald district and has a population of approximately 25,000 distributed in six boroughs: Mosbach Town, Lohrbach, ...

in Germany. In the Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

era the European dhole

The European dhole (''Cuon alpinus europaeus'') was a paleosubspecies of the dhole, which ranged throughout much of Western and Central Europe during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Like the modern Asiatic populations, it was a more progressive ...

(''C. a. europaeus'') was modern-looking and the transformation of the lower molar into a single cusped, slicing tooth had been completed; however, its size was comparable with that of a wolf. This subspecies became extinct in Europe at the end of the late Würm

Wurm or Würm may refer to:

Places

* Wurm (Rur), a river in North Rhine-Westphalia in western Germany

* Würm (Amper), a river in Bavaria, southeastern Germany

** Würm glaciation, an Alpine ice age, named after the Bavarian river

* Würm (Nagold ...

period, but the species as a whole still inhabits a large area of Asia. The European dhole may have survived up until the early Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, and what is believed to be dhole remains have been found at Riparo Fredian in northern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

dated 10,800 years old.

The vast Pleistocene range of this species also included numerous islands in Asia that this species no longer inhabits, such as Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

and possibly Palawan

Palawan (, ), officially the Province of Palawan (; ), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in terms of total area of . The capital and largest c ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. Middle Pleistocene dhole fossils have also been found in the Matsukae Cave in northern Kyushu

is the third-largest island of Japan's Japanese archipelago, four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa Island, Okinawa and the other Ryukyu Islands, Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Ryukyu Islands, Islands ...

Island in western Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and in the Lower Kuzuu fauna in Tochigi Prefecture

is a landlocked Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Tochigi Prefecture has a population of 1,897,649 (1 June 2023) and has a geographic area of 6,408 Square kilometre, km2 (2,474 Square mile, sq mi ...

in Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

Island, east Japan. Dhole fossils from the Late Pleistocene dated to about 10,700 years before present are known from the Luobi Cave or Luobi-Dong cave in Hainan Island

Hainan is an island province and the southernmost province of China. It consists of the eponymous Hainan Island and various smaller islands in the South China Sea under the province's administration. The name literally means "South of the Sea ...

in south China

South China ( zh, s=, p=Huá'nán, j=jyut6 naam4) is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is ...

where they no longer exist. Additionally, fossils of canidae possibly belonging to dhole have been excavated from Dajia River

Dajia River () is the fifth-longest river in Taiwan located in the north-central of the island. It flows through Taichung City for 142 km.

The sources of the Dajia are: Hsuehshan and Nanhu Mountain in the Central Mountain Range. The Dajia ...

in Taichung County

Taichung County was a County (Taiwan), county in central Taiwan between 1945 and 2010. The county seat was in Yuanlin Township before 1950 and Fengyuan District, Fongyuan City after 1950.

History

Taichung County was established on 26 November ...

, Taiwan.

A single record of the dhole is known from North America. This consists of a jaw fragment and teeth of Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

age found in San Josecito Cave in northeast Mexico, dating to around 27–11,000 years ago. Other researchers have either considered this record as "insufficient" or suggested that further corroboration is required for the definitive taxonomic attribution of these specimens.

Dholes are also known from the Middle and Late Pleistocene fossil record of Europe. In 2021, the analyses of the mitochondrial

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used ...

genomes

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

extracted from the fossil remains of two extinct European dhole specimens from the Jáchymka cave, Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

dated 35,000–45,000 years old indicate that these were genetically basal to modern dholes and possessed much greater genetic diversity.

The dhole's distinctive morphology has been a source of much confusion in determining the species' systematic position among the Canidae. George Simpson placed the dhole in the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Simocyoninae alongside the African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called painted dog and Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lycaon'', which is disti ...

and the bush dog

The bush dog (''Speothos venaticus'') is a canine found in Central and South America. In spite of its extensive range, it is very rare in most areas except in Suriname, Guyana and Peru; it was first described by Peter Wilhelm Lund from fossils ...

, on account of all three species' similar dentition. Subsequent authors, including Juliet Clutton-Brock, noted greater morphological similarities to canids of the genera ''Canis'', '' Dusicyon'' and '' Alopex'' than to either '' Speothos'' or '' Lycaon'', with any resemblance to the latter two being due to convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.

Some authors consider the extinct ''Canis'' subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

''Xenocyon

''Xenocyon'' ("strange dog") is an extinct group of canids, either considered a distinct genus or a subgenus of ''Canis''. The group includes ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''africanus'', ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ''antonii'' and ''Canis'' (''Xenocyon'') ...

'' as ancestral to both the genus ''Lycaon'' and the genus ''Cuon''. Subsequent studies on the canid genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

revealed that the dhole and African wild dog are closely related to members of the genus ''Canis''. This closeness to ''Canis'' may have been confirmed in a menagerie in Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

, where according to zoologist Reginald Innes Pocock

Reginald Innes Pocock, (4 March 1863 – 9 August 1947) was a British zoologist.

Pocock was born in Clifton, Bristol, the fourth son of Rev. Nicholas Pocock and Edith Prichard. He began showing interest in natural history at St. Edward's ...

there is a record of a dhole that interbred with a golden jackal. DNA sequencing of the Sardinian dhole (''Cynotherium sardous'') an extinct small canine species formerly native to the island of Sardinia in the Mediterranean, and which has often been suggested to have descended from ''Xenocyon'', has found that it is most closely related to the living dhole among canines.

Admixture with the African wild dog

In 2018,whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing or just genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a single time. This entails sequencing all of an organism's ...

was used to compare all members (apart from the black-backed and side-striped jackals) of the genus ''Canis'', along with the dhole and the African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called painted dog and Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lycaon'', which is disti ...

(''Lycaon pictus''). There was strong evidence of ancient genetic admixture

Genetic admixture occurs when previously isolated populations interbreed resulting in a population that is descended from multiple sources. It can occur between species, such as with hybrids, or within species, such as when geographically dista ...

between the dhole and the African wild dog. Today, their ranges are remote from each other; however, during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

era the dhole could be found as far west as Europe. The study proposes that the dhole's distribution may have once included the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, from where it may have admixed with the African wild dog in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. However, there is no evidence of the dhole having existed in the Middle East nor North Africa, though the ''Lycaon'' was present in Europe during the Early Pleistocene, with its last record in the region dating to 830,000 years ago. Genetic evidence from the Sardinan dhole suggests that both Sardinian and modern dholes (which are estimated to have split from each other around 900,000 years ago) share ancestry from the ''Lycaon'' lineage, but this ancestry is significantly higher in modern dholes than in the Sardinian dhole.

Subspecies

Historically, up to ten subspecies of dholes have been recognised. , seven subspecies are recognised. However, studies on the dhole'smtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the DNA contained in ...

and microsatellite

A microsatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain Sequence motif, DNA motifs (ranging in length from one to six or more base pairs) are repeated, typically 5–50 times. Microsatellites occur at thousands of locations within an organ ...

genotype showed no clear subspecific distinctions. Nevertheless, two major phylogeographic groupings were discovered in dholes of the Asian mainland, which likely diverged during a glaciation event. One population extends from South, Central and North India (south of the Ganges) into Myanmar, and the other extends from India north of the Ganges into northeastern India, Myanmar, Thailand and the Malaysian Peninsula. The origin of dholes in Sumatra and Java is, , unclear, as they show greater relatedness to dholes in India, Myanmar and China rather than with those in nearby Malaysia. However, the Canid Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

(IUCN) states that further research is needed because all of the samples were from the southern part of this species' range and the Tien Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

subspecies has distinct morphology.

In the absence of further data, the researchers involved in the study speculated that Javan and Sumatran dholes could have been introduced to the islands by humans. Fossils of dhole from the early Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, more widely known as the Middle Pleistocene (its previous informal name), is an Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale or a Stage (stratigraphy), stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocen ...

have been found in Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

.

Characteristics

The dhole's general tone of the fur is reddish, with the brightest hues occurring in winter. In the winter coat, the back is clothed in a saturated rusty-red to reddish colour with brownish highlights along the top of the head, neck and shoulders. The throat, chest, flanks, and belly and the upper parts of the limbs are less brightly coloured, and are more yellowish in tone. The lower parts of the limbs are whitish, with dark brownish bands on the anterior sides of the forelimbs. The muzzle and forehead are greyish-reddish. The tail is very luxuriant and fluffy, and is mainly of a reddish-ocherous colour, with a dark brown tip. The summer coat is shorter, coarser and darker. The dorsal and lateral

The dhole's general tone of the fur is reddish, with the brightest hues occurring in winter. In the winter coat, the back is clothed in a saturated rusty-red to reddish colour with brownish highlights along the top of the head, neck and shoulders. The throat, chest, flanks, and belly and the upper parts of the limbs are less brightly coloured, and are more yellowish in tone. The lower parts of the limbs are whitish, with dark brownish bands on the anterior sides of the forelimbs. The muzzle and forehead are greyish-reddish. The tail is very luxuriant and fluffy, and is mainly of a reddish-ocherous colour, with a dark brown tip. The summer coat is shorter, coarser and darker. The dorsal and lateral guard hair

Guard hair or overhair is the outer layer of hair of most mammals, which overlay the fur. Guard hairs are long and coarse and protect the rest of the pelage (fur) from abrasion and frequently from moisture. They are visible on the surface of the ...

s in adults measure in length. Dholes in the Moscow Zoo

The Moscow Zoo or Moskovsky Zoopark () is a zoo, the largest in Russia.

History

The Moscow Zoo was founded in 1864 by professor-biologists, K.F. Rulje, S.A. Usov and A.P. Bogdanov, from the Moscow State University. In 1919, the zoo was natio ...

moult once a year from March to May. A melanistic individual was recorded in the northern Coimbatore

Coimbatore (Tamil: kōyamputtūr, ), also known as Kovai (), is one of the major Metropolitan cities of India, metropolitan cities in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Noyy ...

Forest Division in Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

.

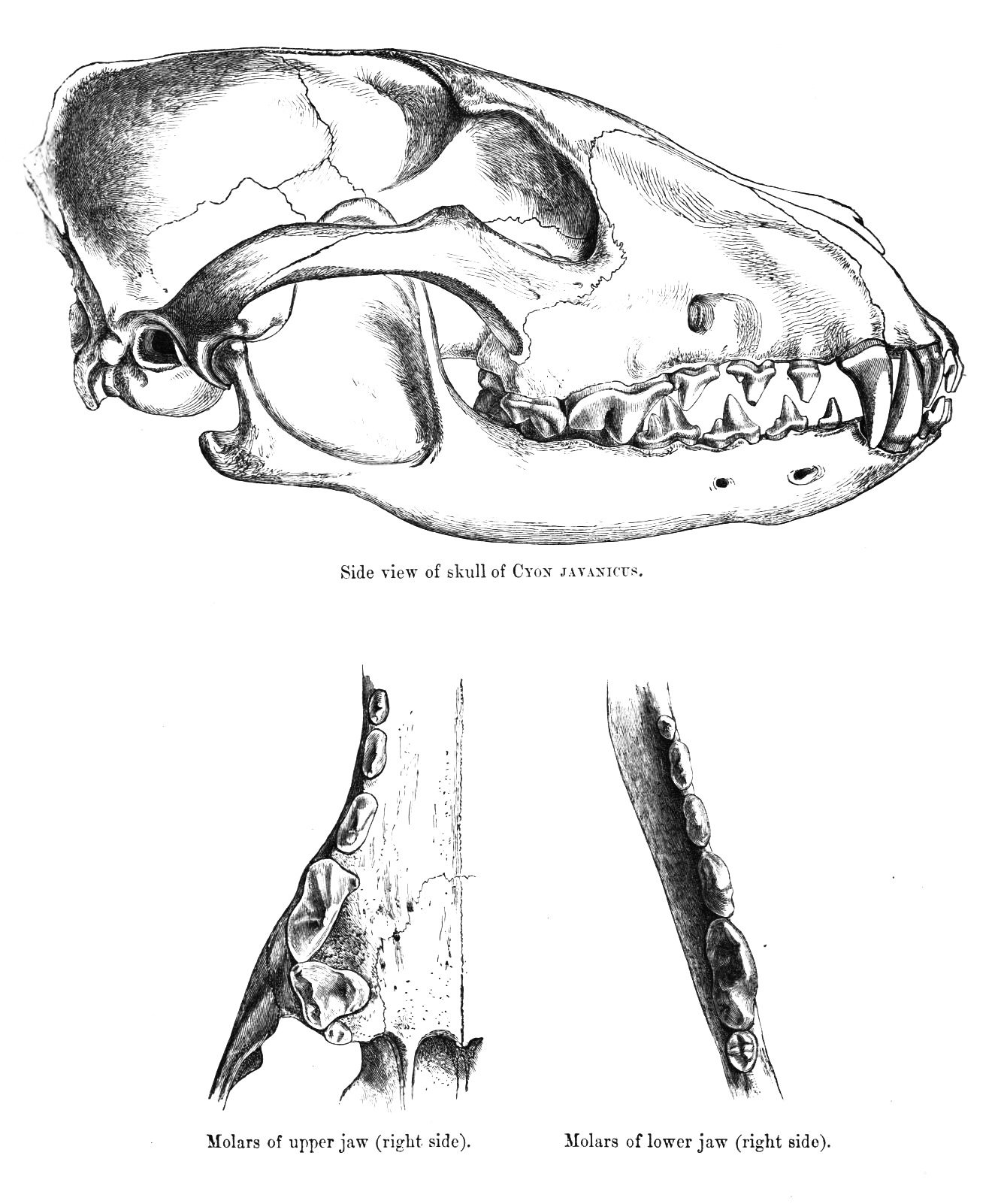

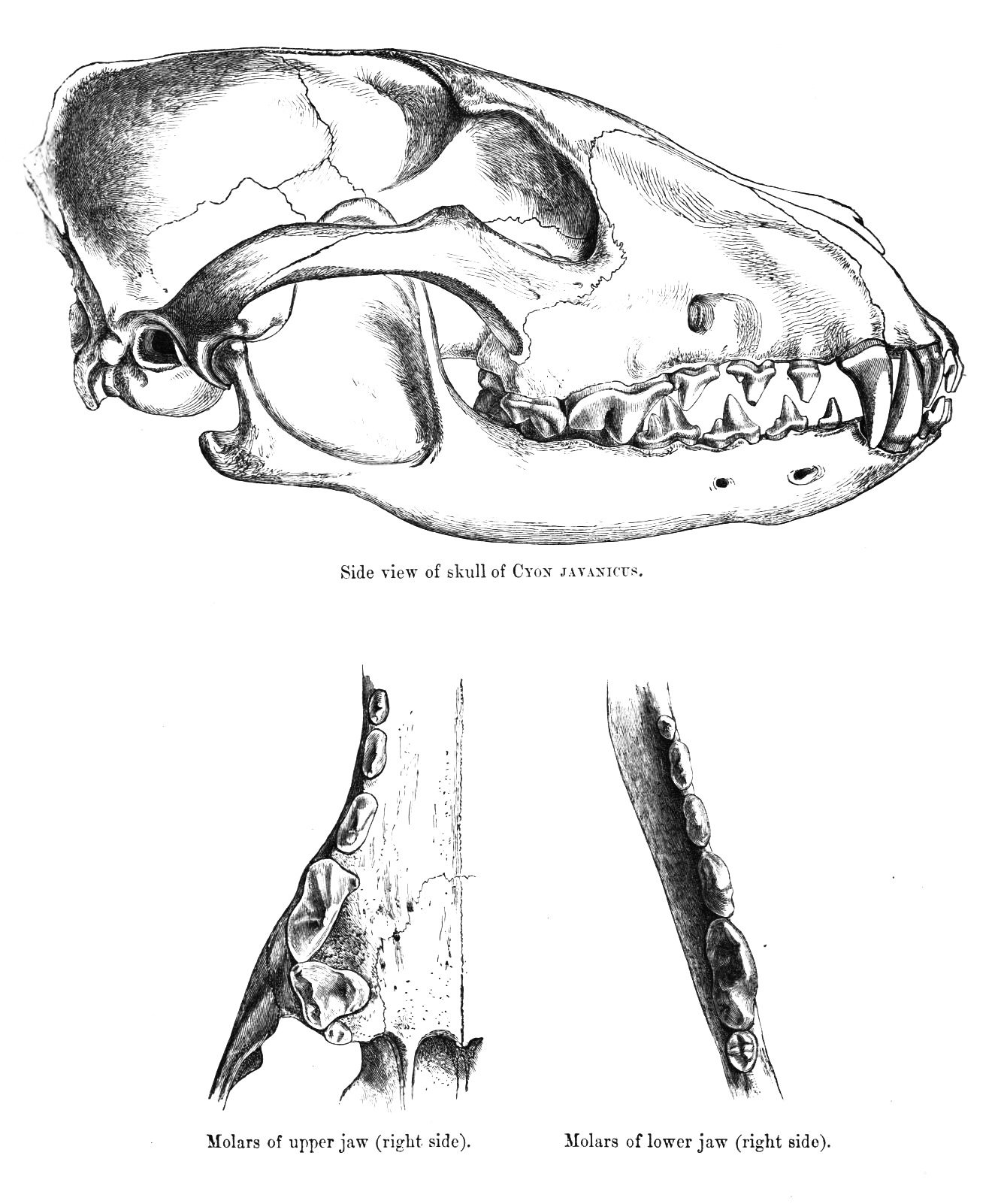

The dhole has a wide and massive skull with a well-developed sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

, and its masseter muscle

In anatomy, the masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. Found only in mammals, it is particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. The most obvious muscle of mastication is the masseter muscle, since it is the ...

s are highly developed compared to other canid species, giving the face an almost hyena

Hyenas or hyaenas ( ; from Ancient Greek , ) are feliform carnivoran mammals belonging to the family Hyaenidae (). With just four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the order Carnivora and one of the sma ...

-like appearance. The rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

is shorter than that of domestic dogs and most other canids. It has six rather than seven lower molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

.

The upper molars are weak, being one third to one half the size of those of wolves and have only one cusp

A cusp is the most pointed end of a curve. It often refers to cusp (anatomy), a pointed structure on a tooth.

Cusp or CUSP may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Cusp (singularity), a singular point of a curve

* Cusp catastrophe, a branch of bifu ...

as opposed to between two and four, as is usual in canids, an adaptation thought to improve shearing ability and thus speed of prey consumption. This may allow dholes to compete more successfully with kleptoparasite

Kleptoparasitism (originally spelt clepto-parasitism, meaning "parasitism by theft") is a form of feeding in which one animal deliberately takes food from another. The strategy is Evolutionarily stable strategy, evolutionarily stable when stealin ...

s. In terms of size, dholes average about in length (excluding a long tail), and stand around at the shoulders. Adult females can weigh , while the slightly larger male may weigh . The mean weight of adults from three small samples was .

In appearance, the dhole has been variously described as combining the physical characteristics of the gray wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

and the red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe and Asia, plus ...

, and as being "cat-like" on account of its long backbone and slender limbs.

Distribution and habitat

Historically, the dhole lived in

Historically, the dhole lived in Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

and throughout Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

including Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

and Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

, though it is now considered to be regionally extinct in these regions. Historical record in South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

from the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty

The ''Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty'', sometimes called ''sillok'' () for short, are state-compiled and published records, called Veritable Records, documenting the reigns of the kings of the Joseon dynasty in Korea. Kept from 1392 ...

also indicate that the dhole once inhabited Yangju in Gyeonggi Province

Gyeonggi Province (, ) is the most populous province in South Korea.

Seoul, the nation's largest city and capital, is in the heart of the area but has been separately administered as a provincial-level ''special city'' since 1946. Incheon, ...

, but it is now also extinct in South Korea, with the last known capture reports in 1909 and 1921 from Yeoncheon

Yeoncheon County (''Yeoncheon-gun'') is a county in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. The county seat is Yeoncheon-eup (연천읍) and sits on Gyeongwon Line, the Korail railroad line connecting Seoul, South Korea (ROK), with North Korea (DPRK).

Hi ...

of Gyeonggi Province

Gyeonggi Province (, ) is the most populous province in South Korea.

Seoul, the nation's largest city and capital, is in the heart of the area but has been separately administered as a provincial-level ''special city'' since 1946. Incheon, ...

. The current presence of dholes in North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

is considered uncertain. The dholes also once inhabited the alpine steppes extending into Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

to the Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory and constitutes an eastern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a Kashmir#Kashmir dispute, dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947 and India an ...

area, though they disappeared from 60% of their historic range in India during the past century. In India, Myanmar, Indochina, Indonesia and China, it prefers forested areas in alpine zone

Alpine tundra is a type of natural region or biome that does not contain trees because it is at high elevation, with an associated alpine climate, harsh climate. As the latitude of a location approaches the poles, the threshold elevation for alp ...

s and is occasionally sighted in plain

In geography, a plain, commonly known as flatland, is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and ...

s regions.

In the Bek-Tosot Conservancy of southern Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

, the possible presence of the dholes was considered likely based on genetic samples collected in 2019. This was the first record of dholes from the country in almost three decades.

The dhole might still be present in the Tunkinsky National Park in extreme southern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

near Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is a rift lake and the deepest lake in the world. It is situated in southern Siberia, Russia between the Federal subjects of Russia, federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast, Irkutsk Oblasts of Russia, Oblast to the northwest and the Repu ...

. It possibly still lives in the Primorsky Krai

Primorsky Krai, informally known as Primorye, is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (a krais of Russia, krai) of Russia, part of the Far Eastern Federal District in the Russian Far East. The types of inhabited localities in Russia, ...

province in far eastern Russia, where it was considered a rare and endangered species in 2004, with unconfirmed reports in the Pikthsa-Tigrovy Dom protected forest area; no sighting was reported in other areas since the late 1970s.

Currently, no other recent reports are confirmed of dholes being present in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, so the IUCN considered them to be extinct in Russia. However, the dhole might be present in the eastern Sayan Mountains

The Sayan Mountains (, ; ) are a mountain range in southern Siberia spanning southeastern Russia (Buryatia, Irkutsk Oblast, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Tuva and Khakassia) and northern Mongolia. Before the rapid expansion of the Tsardom of Russia, the mou ...

and in the Transbaikal

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia ( rus, Забайка́лье, r=Zabaykal'ye, p=zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ), or Dauria (, ''Dauriya'') is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal at the south side of the eastern Si ...

region; it has been sighted in Tofalaria in the Irkutsk Oblast

Irkutsk Oblast (; ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast), located in southeastern Siberia in the basins of the Angara River, Angara, Lena River, Lena, and Nizhnyaya Tunguska Rivers. The administrative center is ...

, the Republic of Buryatia

Buryatia, officially the Republic of Buryatia, is a Republics of Russia, republic of Russia located in the Russian Far East. Formerly part of the Siberian Federal District, it has been administered as part of the Far Eastern Federal District sin ...

and Zabaykalsky Krai

Zabaykalsky Krai is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (a krai), located in the Russian Far East. Its administrative center is Chita, Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita. As of the Russian Census (2010), 2010 Census, the population was ...

.

One pack was sighted in the Qilian Mountains

The Qilian Mountains (), together with the Altyn-Tagh sometimes known as the Nan Shan, as it is to the south of the Hexi Corridor, is a northern outlier of the Kunlun Mountains, forming the border between Qinghai and the Gansu provinces of n ...

in 2006.

In 2011 to 2013, local government officials and herders reported the presence of several dhole packs at elevations of near Taxkorgan Nature Reserve in the Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

Autonomous Region. Several packs and a female adult with pups were also recorded by camera trap

A camera trap is a camera that is automatically triggered by motion in its vicinity, like the presence of an animal or a human being. It is typically equipped with a motion sensor—usually a passive infrared (PIR) sensor or an active infrared ...

s at elevations of around in Yanchiwan National Nature Reserve in the northern Gansu Province

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

in 2013–2014.

Dholes have been also reported in the Altyn-Tagh

Altyn-Tagh (also Altun Mountains or Altun Shan) is a mountain range in Northwestern China that separates the Eastern Tarim Basin from the Tibetan Plateau. The western third is in Xinjiang while the eastern part forms the border between Qinghai t ...

Mountains.

In China's Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

Province, dholes were recorded in Baima Xueshan Nature Reserve in 2010–2011. Dhole samples were obtained in Jiangxi

; Gan: )

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 =

, translit_lang1_type3 =

, translit_lang1_info3 =

, image_map = Jiangxi in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_caption = Location ...

Province in 2013.

Confirmed records by camera-trapping since 2008 have occurred in southern and western Gansu

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

province, southern Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

province, southern Qinghai

Qinghai is an inland Provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. It is the largest provinces of China, province of China (excluding autonomous regions) by area and has the third smallest population. Its capital and largest city is Xin ...

province, southern and western Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

province, western Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

province, the southern Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

Autonomous Region and in the Southeastern Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

Autonomoous Region. There are also historical records of dhole dating to 1521–1935 in Hainan Island, but the species is no longer present and is estimated to have become extinct around 1942.

The dhole occurs in most of India south of the Ganges, particularly in the Central Indian Highlands and the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Eastern Ghats

The Eastern Ghats is a mountain range that stretches along the East Coast of India, eastern coast of the Indian peninsula. Covering an area of , it traverses the states and union territories of India, states of Odisha, Telangana, Andhra Prade ...

. It is also present in Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northeast India. It was formed from the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and India declared it as a state on 20 February 1987. Itanagar is its capital and la ...

, Assam

Assam (, , ) is a state in Northeast India, northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra Valley, Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . It is the second largest state in Northeast India, nor ...

, Meghalaya

Meghalaya (; "the abode of clouds") is a states and union territories of India, state in northeast India. Its capital is Shillong. Meghalaya was formed on 21 January 1972 by carving out two districts from the Assam: the United Khasi Hills an ...

and West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

and in the Indo-Gangetic Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the Northern Plain or North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain spanning across the northern and north-eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. It encompasses North India, northern and East India, easte ...

's Terai

The Terai or Tarai is a lowland region in parts of southern Nepal and northern India that lies to the south of the outer foothills of the Himalayas, the Sivalik Hills and north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

This lowland belt is characterised by ...

region. Dhole populations in the Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than 100 pea ...

s and northwest India are fragmented.

In 2011, dhole packs were recorded by camera traps in the Chitwan National Park

Chitwan National Park is the first national park of Nepal. It was established in 1973 as the Royal Chitwan National Park and was granted the status of a World Heritage Site in 1984. It covers an area of in the Terai of south-central Nepal. It ra ...

. Its presence was confirmed in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area

Kanchenjunga Conservation Area is a protected area in the Himalayas of eastern Nepal that was established in 1997. It covers in the Taplejung District and comprises two peaks of Kanchenjunga. In the north it adjoins the Qomolangma National Nat ...

in 2011 by camera traps. In February 2020, dholes were sighted in the Vansda National Park, with camera traps confirming the presence of two individuals in May of the same year. This was the first confirmed sighting of dholes in Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

since 1970.

In Bhutan

Bhutan, officially the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked country in South Asia, in the Eastern Himalayas between China to the north and northwest and India to the south and southeast. With a population of over 727,145 and a territory of , ...

, the dhole is present in Jigme Dorji National Park

Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP), named after the late Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, is the second-largest National Park of Bhutan.

History

It was established in 1974 and stretches over an area of 4316 km2, thereby spanning all three climate z ...

.

In Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

, it inhabits forest reserves in the Sylhet

Sylhet (; ) is a Metropolis, metropolitan city in the north eastern region of Bangladesh. It serves as the administrative center for both the Sylhet District and the Sylhet Division. The city is situated on the banks of the Surma River and, as o ...

area, as well the Chittagong Hill Tracts

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (), often shortened to simply the Hill Tracts and abbreviated to CHT, refers to the three hilly districts within the Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar (Burma) in the east: Kh ...

in the southeast. Recent camera trap photos in the Chittagong in 2016 showed the continued presence of the dhole. These regions probably do not harbour a viable population, as mostly small groups or solitary individuals were sighted.

In Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

, the dhole is present in several protected areas. In 2015, dholes and tigers were recorded by camera-traps for the first time in the hill forests of Karen State

Kayin State (, ; ; , ), formerly known as Karen State, is a state of Myanmar. The capital city is Hpa-An, also spelled Pa-An.

The terrain of the state is mountainous; with the Dawna Range running along the state in a NNW–SSE direction, and ...

.

Its range is highly fragmented in the Malaysian Peninsula, Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

, Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

and Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, with the Vietnamese population considered to be possibly extinct. In 2014, camera trap videos in the montane tropical forests at in the Kerinci Seblat National Park in Sumatra revealed its continued presence. A camera trapping survey in the Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

The Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary () is a protected area at the western extremities of the Cardamom Mountains in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. Founded in 1977, it is an IUCN Category IV wildlife sanctuary, with an area of 674,352 rai ~ ...

in Thailand from January 2008 to February 2010 documented one healthy dhole pack. In northern Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

, dholes were studied in Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area. Camera trap surveys from 2012 to 2017 recorded dholes in the same Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area.

In Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, dholes were sighted only in Pu Mat National Park in 1999, in Yok Don National Park in 2003 and 2004; and in Ninh Thuan Province in 2014.

A disjunct dhole population was reported in the area of Trabzon

Trabzon, historically known as Trebizond, is a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. The city was founded in 756 BC as "Trapezous" by colonists from Miletus. It was added into the Achaemenid E ...

and Rize

Rize (; ; ; ka, რიზე}; ) is a coastal city in the eastern part of the Black Sea Region of Turkey. It is the seat of Rize Province and Rize District.Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

near the border with Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

in the 1990s. This report was not considered to be reliable. One single individual was claimed to have been shot in 2013 in the nearby Kabardino-Balkaria

Kabardino-Balkaria (), officially the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, is a republic of Russia located in the North Caucasus. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 904,200. Its capital is Nalchik. The area contains the highest mountain in ...

Republic of Russia in the central Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

; its remains were analysed in May 2015 by a biologist from the Kabardino-Balkarian State University

Kabardino-Balkarian State University (KBSU); ''Kabardino_Balkarskii gosudarstvennii universitet imeni H. M. Berbekova'', often abbreviated КБГУ, ''KBSU'') is a coeducational and public research university located in Nalchik, Kabardino-Balk ...

, who concluded that the skull was indeed that of a dhole. In August 2015, researchers from the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

and the Karadeniz Technical University started an expedition to track and document possible Turkish population of dhole. In October 2015, they concluded that two skins of alleged dholes in Turkey probably belonged to dogs, pending DNA analysis of samples from the skins, and, having analysed photos of the skull of alleged dhole in Kabardino-Balkaria Republic of Russia, they concluded it was a grey wolf.

Ecology and behaviour

Dholes produce whistles resembling the calls of red foxes, sometimes rendered as ''coo-coo''. How this sound is produced is unknown, though it is thought to help in coordinating the pack when travelling through thick brush. When attacking prey, they emit screaming ''KaKaKaKAA'' sounds. Other sounds include whines (food soliciting), growls (warning), screams, chatterings (both of which are alarm calls) and yapping cries. In contrast to wolves, dholes do nothowl

Howl most often refers to:

* Howling, an animal vocalization in many canine species

* "Howl" (poem), a 1956 poem by Allen Ginsberg

Howl or The Howl may also refer to:

Film

* '' The Howl'', a 1970 Italian film

* ''Howl'' (2010 film), a 2010 Am ...

or bark.

Dholes have a complex body language

Body language is a type of nonverbal communication in which physical behaviors, as opposed to words, are used to express or convey information. Such behavior includes facial expressions, body posture, gestures, eye movement, touch and the use o ...

. Friendly or submissive greetings are accompanied by horizontal lip retraction and the lowering of the tail, as well as licking. Playful dholes open their mouths with their lips retracted and their tails held in a vertical position whilst assuming a play bow. Aggressive or threatening dholes pucker their lips forward in a snarl and raise the hairs on their backs, as well as keep their tails horizontal or vertical. When afraid, they pull their lips back horizontally with their tails tucked and their ears flat against the skull.

Social and territorial behaviour

Dholes are more social than gray wolves, and have less of a dominance hierarchy, as seasonal scarcity of food is not a serious concern for them. In this manner, they closely resemble African wild dogs in social structure. They live inclan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

s rather than pack

Pack or packs may refer to:

Music

* Packs (band), a Canadian indie rock band

* ''Packs'' (album), by Your Old Droog

* ''Packs'', a Berner album

Places

* Pack, Styria, defunct Austrian municipality

* Pack, Missouri, United States (US)

* ...

s, as the latter term refers to a group of animals that always hunt together. In contrast, dhole clans frequently break into small packs of three to five animals, particularly during the spring season, as this is the optimal number for catching fawns. Dominant dholes are hard to identify, as they do not engage in dominance displays as wolves do, though other clan members will show submissive behaviour toward them. Intragroup fighting is rarely observed.

Dholes are far less

Dholes are far less territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

than wolves, with pups from one clan often joining another without trouble once they mature sexually. Clans typically number 5 to 12 individuals in India, though clans of 40 have been reported. In Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, clans rarely exceed three individuals. Unlike other canids, there is no evidence of dholes using urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and many other animals. In placental mammals, urine flows from the Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder and exits the urethra through the penile meatus (mal ...

to mark their territories or travel routes. When urinating, dholes, especially males, may raise one hind leg or both to result in a handstand. Handstand urination is also seen in bush dog

The bush dog (''Speothos venaticus'') is a canine found in Central and South America. In spite of its extensive range, it is very rare in most areas except in Suriname, Guyana and Peru; it was first described by Peter Wilhelm Lund from fossils ...

s (''Speothos venaticus'') and domestic dogs. They may defecate in conspicuous places, though a territorial function is unlikely, as faeces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

are mostly deposited within the clan's territory rather than the periphery. Faeces are often deposited in what appear to be communal latrines. They do not scrape the earth with their feet, as other canids do, to mark their territories.

Denning

Four kinds of den have been described; simple earth dens with one entrance (usually remodeledstriped hyena

The striped hyena (''Hyaena hyaena'') is a species of hyena native to North and East Africa, the Middle East, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Hyaena''. It is listed by the IU ...

or porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp Spine (zoology), spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two Family (biology), families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New ...

dens); complex cavernous earth dens with more than one entrance; simple cavernous dens excavated under or between rocks; and complex cavernous dens with several other dens in the vicinity, some of which are interconnected. Dens are typically located under dense scrub or on the banks of dry rivers or creeks. The entrance to a dhole den can be almost vertical, with a sharp turn three to four feet down. The tunnel opens into an antechamber, from which extends more than one passage. Some dens may have up to six entrances leading up to of interconnecting tunnels. These "cities" may be developed over many generations of dholes, and are shared by the clan females when raising young together. Like African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called painted dog and Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lycaon'', which is disti ...

s and dingo

The dingo (either included in the species ''Canis familiaris'', or considered one of the following independent taxa: ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient (basal (phylogenetics), basal) lineage ...

es, dholes will avoid killing prey close to their dens.

Reproduction and development

In India, the

In India, the mating season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and ch ...

occurs between mid-October and January, while captive dholes in the Moscow Zoo

The Moscow Zoo or Moskovsky Zoopark () is a zoo, the largest in Russia.

History

The Moscow Zoo was founded in 1864 by professor-biologists, K.F. Rulje, S.A. Usov and A.P. Bogdanov, from the Moscow State University. In 1919, the zoo was natio ...

breed mostly in February. Unlike wolf packs, dhole clans may contain more than one breeding female. More than one female dhole may den and rear their litters together in the same den. During mating

In biology, mating is the pairing of either opposite-sex or hermaphroditic organisms for the purposes of sexual reproduction. ''Fertilization'' is the fusion of two gametes. '' Copulation'' is the union of the sex organs of two sexually repr ...

, the female assumes a crouched, cat-like position. There is no copulatory tie

Canine reproduction is the process of sexual reproduction in domestic dogs, wolves, coyotes and other canine species.

Canine sexual anatomy and development Male reproductive system

Erectile tissue

As with all mammals, a dog's penis is made up ...

characteristic of other canids when the male dismounts. Instead, the pair lie on their sides facing each other in a semicircular formation. The gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once i ...

lasts 60–63 days, with litter sizes averaging four to six pups. Their growth rate is much faster than that of wolves, being similar in rate to that of coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

s.

The hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of cell signaling, signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physio ...

metabolites of five males and three females kept in Thai zoos was studied. The breeding males showed an increased level of testosterone

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone and androgen in Male, males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testicles and prostate, as well as promoting se ...

from October to January. The oestrogen

Estrogen (also spelled oestrogen in British English; see spelling differences) is a category of sex hormone responsible for the development and regulation of the female reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics. There are three m ...

level of captive females increases for about two weeks in January, followed by an increase of progesterone

Progesterone (; P4) is an endogenous steroid and progestogen sex hormone involved in the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and embryogenesis of humans and other species. It belongs to a group of steroid hormones called the progestogens and is the ma ...

. They displayed sexual behaviours during the oestrogen peak of the females.

Pups are suckled at least 58 days. During this time, the pack feeds the mother at the den site. Dholes do not use rendezvous sites to meet their pups as wolves do, though one or more adults will stay with the pups at the den while the rest of the pack hunts. Once weaning

Weaning is the process of gradually introducing an infant human or other mammal to what will be its adult diet while withdrawing the supply of its mother's milk. In the United Kingdom, UK, weaning primarily refers to the introduction of solid ...

begins, the adults of the clan will regurgitate food for the pups until they are old enough to join in hunting. They remain at the den site for 70–80 days. By the age of six months, pups accompany the adults on hunts and will assist in killing large prey such as sambar by the age of eight months. Maximum longevity in captivity is 15–16 years.

Hunting behaviour