Cultural Cold War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cultural Cold War was a set of

The CIA, in particular, used a wide range of

The CIA, in particular, used a wide range of

This 30-day arts festival, held in Paris, was sponsored by the CCF in 1952 in order to alter the image of the U.S. as having a bleak and empty cultural scene. The CCF under Nabokov believed that American modernist culture could serve as an ideological resistance to the Soviet Union. As a result, the CCF commissioned nine different orchestras to perform concertos, operas, and ballets by over 70 composers who had been labeled by communist commissars as "degenerate" and "sterile." This included compositions by

This 30-day arts festival, held in Paris, was sponsored by the CCF in 1952 in order to alter the image of the U.S. as having a bleak and empty cultural scene. The CCF under Nabokov believed that American modernist culture could serve as an ideological resistance to the Soviet Union. As a result, the CCF commissioned nine different orchestras to perform concertos, operas, and ballets by over 70 composers who had been labeled by communist commissars as "degenerate" and "sterile." This included compositions by

During the

During the

''Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture, and the Cold War''.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. * Wenderski, Michał. ''Art and Politics During the Cold War: Poland and the Netherlands''. London: Routledge, 2024. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cia And The Cultural Cold War Central Intelligence Agency Cold War CIA-funded propaganda Propaganda in the United States

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

campaigns waged by the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, with each country promoting their own culture, arts, literature, and music. In addition, less overtly, their opposing political choices and ideologies at the expense of the other. Many of the battles were fought in Europe or in European Universities, with Communist Party leaders depicting the United States as a cultural black hole while pointing to their own cultural heritage as proof that they were the inheritors of the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

. The U.S. responded by accusing the Soviets of "disregarding the inherent value of culture," and subjugating art to the controlling policies of a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

political system, even as they felt saddled with the responsibility of preserving and fostering western civilization

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompasses the social no ...

's best cultural traditions, given the many European artists who took refuge in the United States before, during, and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

History

Role of the CIA and the CCF

In 1950, theCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA) surreptitiously created the Congress for Cultural Freedom

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an anti-communist cultural organization founded on 26 June 1950 in West Berlin. At its height, the CCF was active in thirty-five countries. In 1966 it was revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency w ...

(CCF) to counter the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist–Leninist communist parties in Europe which existed from 1947 to 1956. Formed in the wake of the dissolution ...

's "peace offensive." At its peak, the Congress had "offices in thirty-five countries, employed dozens of personnel, published over twenty prestige magazines, held art exhibition

An art exhibition is traditionally the space in which art objects (in the most general sense) meet an audience. The exhibit is universally understood to be for some temporary period unless, as is occasionally true, it is stated to be a "permanen ...

s, owned a news and features service, organized high-profile international conferences, and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances." The point of these endeavors was to "showcase" U.S. and European high culture, including not just musical works but painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

s, ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

s, and other artistic avenues, for the benefit of nonaligned foreign intellectuals.Wilford, Hugh. The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America. London, England: Harvard University Press, 2008.

CCF and music

Many U.S. government organizations used American music to persuade audiences worldwide that the U.S. was a cradle for the growth of music. The CIA and, in turn the CCF, were reluctant to patronize America's musical avant-garde, which included artists such experimental musicians asMilton Babbitt

Milton Byron Babbitt (May 10, 1916 – January 29, 2011) was an American composer, music theorist, mathematician, and teacher. He was a Pulitzer Prize and MacArthur Fellowship recipient, recognized for his serial and electronic music.

Biography ...

and John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and Extended technique, non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one ...

. The CCF took a more conservative approach, as outlined under its General Secretary, Nicolas Nabokov, and concentrated its efforts on presenting older European works that had been banned or condemned by the Communist Party.

The CCF provided partial funding for the Darmstadt Summer Course from 1946 to 1956. This was the beginning of the Darmstadt School

Darmstadt School refers to a group of composers who were associated with the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music (Darmstädter Ferienkurse) from the early 1950s to the early 1960s in Darmstadt, Germany, and who shared some aesth ...

of composers which helped pioneer the avant-garde techniques of Serialism

In music, serialism is a method of composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though some of his contemporaries were also ...

.

In 1952, the CCF sponsored the Festival of Twentieth-Century Masterpieces of Modern Arts in Paris. Over the next thirty days, the festival hosted nine separate orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, ...

s which performed works by over 70 composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

s, many of whom had been dismissed by communist critics as "degenerate" and "sterile," including composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

and Claude Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

. The festival opened with a performance of Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ( – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of ...

's ''The Rite of Spring

''The Rite of Spring'' () is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1913 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; the original choreography was by Vaslav Nijinsky ...

'', as performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five (orchestras), Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in ...

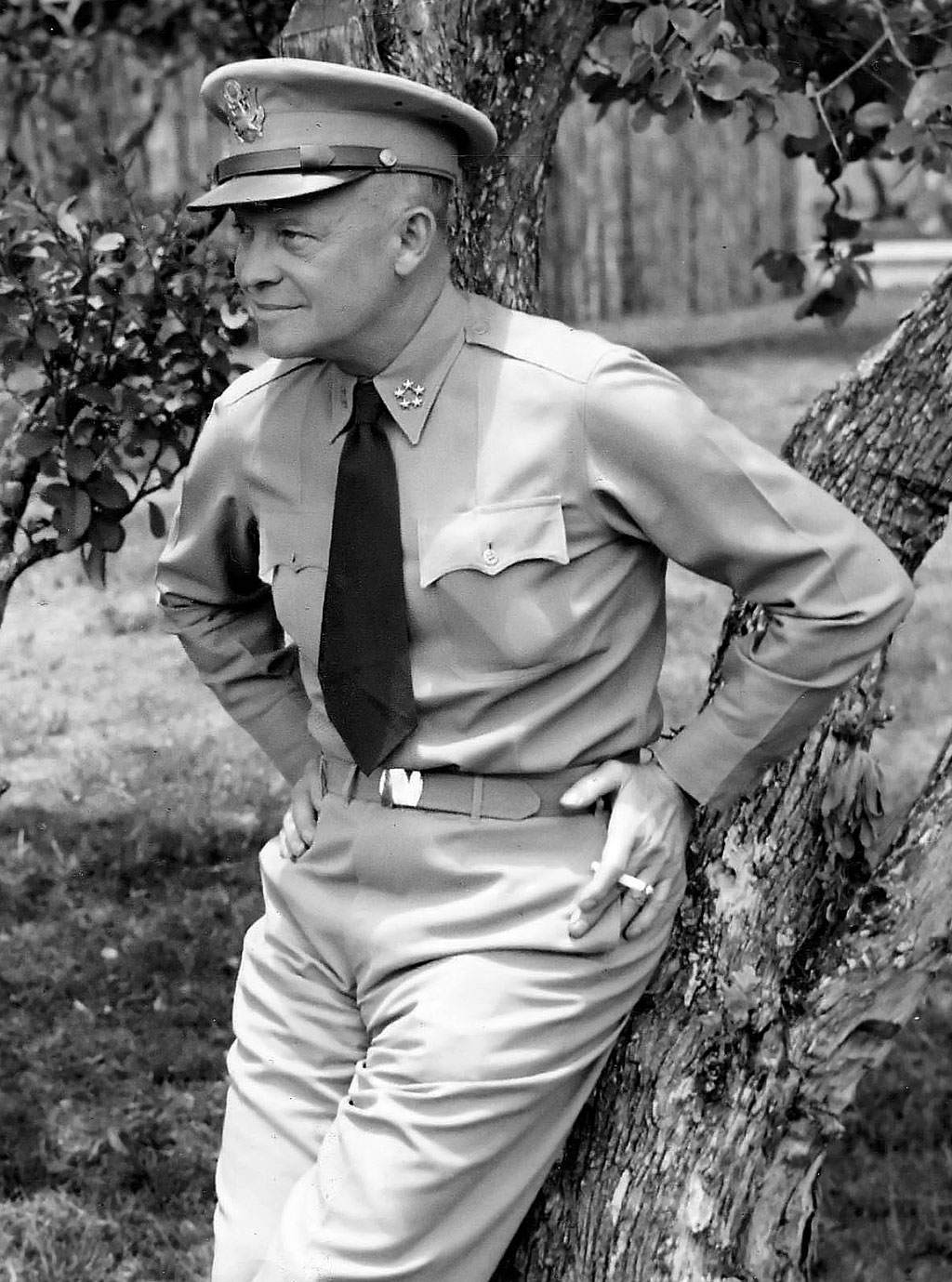

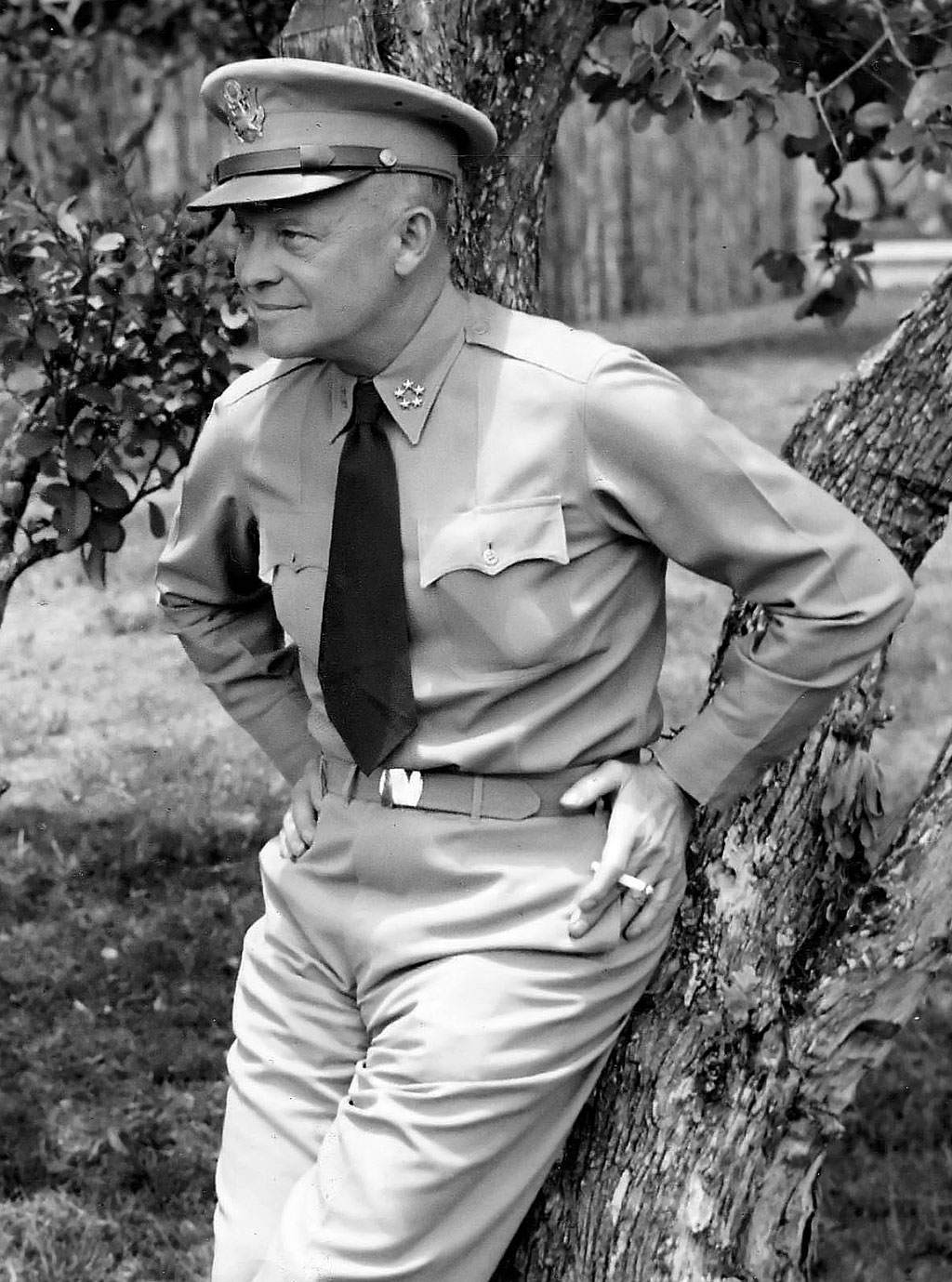

. Thomas Braden

Thomas Wardell Braden (February 22, 1917 – April 3, 2009) was an American CIA official, journalist–– best remembered as the author of ''Eight Is Enough'', which spawned a television program–– and co-host of the CNN show ''Crossfire ...

, a senior member of the CIA said: "The Boston Symphony Orchestra won more acclaim for the U.S. in Paris than John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

or Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

could have brought with a hundred speeches".

The CIA, in particular, used a wide range of

The CIA, in particular, used a wide range of musical genre

A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions. Genre is to be distinguished from musical form and musical style, although in practice these terms are sometim ...

s, including Broadway musicals, and even the jazz of Dizzy Gillespie, to convince music enthusiasts across the globe that the U.S. was committed to the musical arts as much as they were to the literary and visual arts. Under the leadership of Nabokov, the CCF organized impressive musical events that were anti-communist in nature, transporting America's prime musical talents to Berlin, Paris, and London to provide a steady series of performances and festivals. In order to promote cooperation between artists and the CCF, and thus extend their ideals, the CCF provided financial aid to artists in need of monetary assistance.

However, because the CCF failed to offer much support for classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be #Relationship to other music traditions, distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical mu ...

associated with the likes of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: �joːhan zeˈbasti̯an baχ ( – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety of instruments and forms, including the or ...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

, and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

, it was deemed an “authoritarian” tool of Soviet communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and wartime German and Italian fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. The CCF also distanced itself from experimental musical avant-garde artists such as Milton Babbitt and John Cage, preferring to focus on earlier European works that had been banned or condemned as "formalist" by Soviet authorities.

Nicolas Nabokov, Secretary General of the CCF

Nicolas Nabokov was a Russian-born composer and writer who developed CCF's music program while serving as the organization's Secretary-General. His compositions include several notable musical works, the first of which was the ballet-oratorio

An oratorio () is a musical composition with dramatic or narrative text for choir, soloists and orchestra or other ensemble.

Similar to opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguisha ...

Ode, produced by Serge Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), also known as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario an ...

's Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo

The company Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo (with a plural name) was formed in 1932 after the death of Sergei Diaghilev and the demise of Ballets Russes. Its director was Wassily de Basil (usually referred to as Colonel W. de Basil), and it ...

, in 1928 and ''Lyrical Symphony'' in 1931. Nabokov moved to the U.S. in 1933 to serve as a lecturer in music for the Barnes Foundation

The Barnes Foundation is an art collection and educational institution promoting the appreciation of art and horticulture. Originally in Merion, the art collection moved in 2012 to a new building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, ...

. A year after moving to the U.S., Nabokov composed the ballet ''Union Pacific''. He went on to teach music at Wells College

Wells College was a private liberal arts college in Aurora, New York, a village in the Finger Lakes region of the state. From its founding in 1868 until it became coeducational in 2005, Wells was a women's college. The college maintained acad ...

in New York from 1936 to 1941, and later at St. John's College in Maryland. In 1939, Nabokov officially became a U.S citizen.

In 1945, Nabokov moved to Germany to work for the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) was a written report created by a board of experts assembled to produce an impartial assessment of the effects of the Anglo-American strategic bombing of Nazi Germany during the European theatre ...

as a civilian cultural adviser. He returned to the U.S. just two years later to teach at the Peabody Conservatory

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a private music and dance conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliated with Johns Hopkins in 1977.

History

Philanthropist and ...

before becoming the Secretary-General of the newly created CCF in 1951. Nabokov remained in this position for over fifteen years, spearheading popular music and cultural festivals during his tenure. During this time he also wrote music for the opera ''Rasputin's End'' in 1958 and was commissioned by the New York City Ballet

New York City Ballet (NYCB) is a ballet company founded in 1948 by choreographer George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein. Balanchine and Jerome Robbins are considered the founding choreographers of the company. Léon Barzin was the company's fir ...

to compose music for ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'' in 1966. When the CCF disbanded in 1967, Nabokov returned to a career in teaching at several universities throughout the U.S., and composed music for the opera ''Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and his three companions as ...

'' in 1973.

Festival of Twentieth-Century Masterpieces of Modern Arts

This 30-day arts festival, held in Paris, was sponsored by the CCF in 1952 in order to alter the image of the U.S. as having a bleak and empty cultural scene. The CCF under Nabokov believed that American modernist culture could serve as an ideological resistance to the Soviet Union. As a result, the CCF commissioned nine different orchestras to perform concertos, operas, and ballets by over 70 composers who had been labeled by communist commissars as "degenerate" and "sterile." This included compositions by

This 30-day arts festival, held in Paris, was sponsored by the CCF in 1952 in order to alter the image of the U.S. as having a bleak and empty cultural scene. The CCF under Nabokov believed that American modernist culture could serve as an ideological resistance to the Soviet Union. As a result, the CCF commissioned nine different orchestras to perform concertos, operas, and ballets by over 70 composers who had been labeled by communist commissars as "degenerate" and "sterile." This included compositions by Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

, Erik Satie

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie (born 17 May 18661 July 1925), better known as Erik Satie, was a French composer and pianist. The son of a French father and a British mother, he studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, Paris Conservatoire but was an undi ...

, Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian and American composer, music theorist, teacher and writer. He was among the first Modernism (music), modernists who transformed the practice of harmony in 20th-centu ...

, Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( ; ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 19255 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war contemporary classical music.

Born in Montb ...

, Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic music, Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and ...

, Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith ( ; ; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German and American composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advo ...

, and Claude Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

.

The festival opened with a performance of Igor Stravinsky's ''Rite of Spring'', conducted by Stravinsky and Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (; 4 April 18751 July 1964) was a French (later American) conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1 ...

, the original conductor in 1913 when the ballet instigated a riot by the Parisian public. The entire Boston Symphony Orchestra was brought to Paris to perform the overture for the large sum of $160,000. The performance was so powerful in uniting the public under a common anti-Soviet stance that American journalist Tom Braden remarked that "the Boston Symphony Orchestra won more acclaim for the U.S. in Paris than John Foster Dulles or Dwight D. Eisenhower could have brought with a hundred speeches." An additional revolutionary performance at the festival was Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassic ...

's ''Four Saints'', an opera that contained an all-black cast. This performance was selected to counter European criticisms of the treatment of African Americans living in the U.S.

Participation of Louis Armstrong

During the

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and several era ...

was promoted around the world as a symbol of US culture, racial progress, and foreign policy

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

. It was during the Jim Crow Era

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

that Armstrong was appointed a Goodwill Jazz Ambassador, and his job entailed representing the American government's commitment to advance the liberties of African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

s at home, while also working to endorse the social freedom of those abroad.

Armstrong's visit to Africa's Gold Coast was hugely successful and attracted magnificent crowds and widespread press coverage. His band's performance in Accra

Accra (; or ''Gaga''; ; Ewe: Gɛ; ) is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , had a population of ...

resulted in public enthusiasm due to what was deemed an "unbiased support for the African course".

Although Armstrong was indeed advocating the US foreign policy strategies in Africa, he did not whole-heartedly agree with some of the American government's decisions in the South. During the 1957 school desegregation

In the United States, school integration (also known as desegregation) is the process of ending race-based segregation within American public, and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and ...

crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Arkansas, most populous city of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city's population was 202,591 as of the 2020 census. The six-county Central Arkan ...

, Armstrong made it a point to openly criticize President Eisenhower and Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus

Orval Eugene Faubus ( ; January 7, 1910 – December 14, 1994) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Arkansas, 36th Governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967, as a member of the Democratic Party (United States), D ...

. Instigated by Faubus's decision to use the National Guard to prevent Black students from integrating into Little Rock High School, Armstrong abandoned his ambassadorship periodically, jeopardizing the US's attempt to use Armstrong to represent America's racial position abroad, specifically in the Soviet Union.

It was not until Eisenhower sent federal troops to uphold integration that Armstrong reconsidered and went back to his position with the State Department. Although he had deserted his trip to the Soviet Union, he later went on to tour several times for the US government, including a six-month African tour in 1960–1961. It was during this time that Armstrong continued to criticize the American government for dragging its feet on the Civil Rights issue, highlighting the contradictory nature of the Goodwill Jazz Ambassadors' mission. Armstrong and Dave

Dave may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Dave'' (film), a 1993 film starring Kevin Kline and Sigourney Weaver

* ''Dave'' (musical), a 2018 stage musical adaptation of the 1993 film

* ''Dave'' (TV series), a 2020 American comedy series

* ...

and Iola Brubeck

David Warren Brubeck (; December 6, 1920 – December 5, 2012) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Often regarded as a foremost exponent of cool jazz, Brubeck's work is characterized by unusual time signatures and superimposing contrasti ...

(other Ambassadors at the time) asserted that although they represented the American government, they did not represent all of the same policies.

Ultimately, although America no doubt benefited from the tours by black artists (including Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

and Dizzy Gillespie), these ambassadors did not advocate a singularly American identity. They instead encouraged solidarity among black people, and were constantly contesting those policies that did not fully sympathize with the aims of the civil rights movement.

See also

* * * * * *References

Further reading

* Appy, Christian G. ''Cold War Constructions: The Political Culture of United States Imperialism, 1945–1966''. Culture, Politics, and the Cold War. Amherst: TheUniversity of Massachusetts Press

The University of Massachusetts Press is a university press that is part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The press was founded in 1963, publishing scholarly books and non-fiction. The press imprint is overseen by an interdisciplinar ...

, 2000.

* Klein, Michael. ''An American Half-century: Postwar Culture and Politics in the USA''. London & Boulder, Colorado: Pluto Press, 1994.

* Rubin, Andrew N''Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture, and the Cold War''.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. * Wenderski, Michał. ''Art and Politics During the Cold War: Poland and the Netherlands''. London: Routledge, 2024. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cia And The Cultural Cold War Central Intelligence Agency Cold War CIA-funded propaganda Propaganda in the United States