Cultural And Scientific Conference For World Peace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the

In August 1948 through the initiative of the

In August 1948 through the initiative of the

The

The

''Report on the Communist "peace" offensive. A campaign to disarm and defeat the United States'', 1951

/ref>

''100 years of Peace Making: A History of the International Peace Bureau and other international peace movement organisations and networks''

, Pax förlag, International Peace Bureau, January 1991. One delegate to the Congress, the Swedish artist , heard no spontaneous contributions or free discussions, only prepared speeches, and described the atmosphere there as "agitated", "aggressive" and "warlike". A speech given at Paris by

The WPC was directed by the International Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party through the

The WPC was directed by the International Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party through the

(book), ''A History of the World in 100 Objects''. Muhammad al-Ashmar and

, CIA. *

"The KGB: Eyes of the Kremlin"

''Time'', 14 February 1983.

p. 42

As a result of this confrontation, 40 non-aligned organizations decided to form a new international body, the

"Oxford Conference of Non-aligned Peace Organizations"

, 30 January 1963. From about 1982, following the proclamation of

"The Independent Peace Movements in Eastern Europe"

, ''Peace Magazine'', December 1985. In December 1982, the Soviet Peace Committee President, Yuri Zhukov, returning to the rhetoric of the mid-1950s, wrote to several hundred non-communist peace groups in Western Europe accusing the

"The Ghost Ship of Lönnrotinkatu"

, ''Peace Magazine'', May–June 1992. Following the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union, the WPC lost most of its support, income and staff and dwindled to a small core group. Its international conferences now attract only a tenth of the delegates that its Soviet-backed conferences could attract ( see below), although it still issues statements couched in similar terms to those of its historic appeals.

''Moscow and the Peace Offensive''

, 1982. In 1968 it re-assumed its name and moved to Helsinki,

''Foreign Policies of the Soviet Union''

, Hoover Press, 1991, , pp. 79–88. After the year 2000 and the shifting of the Head office to

''The Last of the WPC Mohicans''

, The View from the Left Bank, 1 August 2011.

''Peace at Home and All Over the World''

, Moscow: International Federation for Peace and Conciliation, p. 345.

** Armenian Committee for Peace and Conciliation

** National Peace Committee of Republic of Azerbaijan

**

''World Peace Council Collected Records, 1949 – 1996''

in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection. * * * At the

The Danish Peace Academy

* ttp://www.britishpathe.com/record.php?id=69117 Pathe News film of 1962 Moscow Congress {{DEFAULTSORT:World Peace Council Organizations based in Athens Organizations established in 1949 Communist front organizations

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist–Leninist communist parties in Europe which existed from 1947 to 1956. Formed in the wake of the dissolution ...

and propped up by the Soviet Union. Throughout the Cold War, WPC engaged in propaganda efforts on behalf of the Soviet Union, whereby it criticized the United States and its allies while defending the Soviet Union's involvement in numerous conflicts.

The organization had the stated goals of advocating for universal disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing Weapon, weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, ...

, sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

, independence, peaceful co-existence, and campaigns against imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

and all forms of discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

. The organization's propagandizing for the USSR led to the decline of its influence over the peace movement in non-Communist countries.

Its first president was the French physicist and activist Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

. It was based in Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

, Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, from 1968 to 1999, and since in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

.

History

Origins

In August 1948 through the initiative of the

In August 1948 through the initiative of the Communist Information Bureau

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxism-Leninism, Marxist–Leninist communist party, communist parties in Europe which existed from 1947 to 1956. Forme ...

(Cominform) a "World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace

The World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace () was an international conference held on 25 to 28 August 1948 at Wrocław University of Technology. It was organized in the aftermath of the Second World War by the authorities of the Pol ...

" was held in Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

, Poland.Milorad Popov, "The World Council of Peace," in Witold S. Sworakowski (ed.), ''World Communism: A Handbook, 1918–1965.'' Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1973; pg. 488.

This gathering established a permanent organisation called the International Liaison Committee of Intellectuals for Peace—a group which joined with another international Communist organisation, the Women's International Democratic Federation

The Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) is an international women's rights organization. Established in 1945, it was most active during the Cold War when, according to historian Francisca de Haan, it was "the largest and probably ...

to convene a second international conclave in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

in April 1949, a meeting designated the World Congress of Partisans for Peace (Congrès Mondial des Partisans de la Paix). Some 2,000 delegates from 75 countries were in attendance at this foundation gathering in the French capital.

A new permanent organization emerged from the April 1949 conclave, the World Committee of Partisans for Peace. At a Second World Congress held in Warsaw in November 1950, this group adopted the new name World Peace Council (WPC). The origins of the WPC lay in the Cominform's doctrine that the world was divided between "peace-loving" progressive forces led by the Soviet Union and "warmongering" capitalist countries led by the United States, declaring that peace "should now become the pivot of the entire activity of the Communist Parties", and most western Communist parties followed this policy.

In 1950, Cominform adopted the report of Mikhail Suslov

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov (; 25 January 1982) was a Soviet people, Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union#Secretariat, Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Sovi ...

, a senior Soviet official, praising the Partisans for Peace and resolving that, "The Communist and Workers' Parties must utilize all means of struggle to secure a stable and lasting peace, subordinating their entire activity to this" and that "Particular attention should be devoted to drawing into the peace movement trade unions, women's, youth, cooperative, sport, cultural, education, religious and other organizations, and also scientists, writers, journalists, cultural workers, parliamentary and other political and public leaders who act in defense of peace and against war."

Lawrence Wittner, a historian of the post-war peace movement, argues that the Soviet Union devoted great efforts to the promotion of the WPC in the early post-war years because it feared an American attack and American superiority of arms at a time when the US possessed the atom bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear explo ...

but the Soviet Union had not yet developed it. This was in opposition to the theory that America had no plans to attack anyone, and the purpose of the WPC was to disarm the US and the NATO alliance for a future Soviet attack.

Wrocław 1948 and New York 1949

The

The World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace

The World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace () was an international conference held on 25 to 28 August 1948 at Wrocław University of Technology. It was organized in the aftermath of the Second World War by the authorities of the Pol ...

met in Wrocław on 6 August 1948.Wittner, Lawrence S., ''One World or None: A History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement Through 1953'' (Vol. 1 of ''The Struggle Against the Bomb'') Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Stanford University Press (SUP) is the publishing house of Stanford University. It is one of the oldest academic presses in the United States and the first university press to be established on the West Coast. It is currently a member of the Ass ...

, 1993. Paperback edition, 1995. Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and Internationalism (politics), internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentiet ...

, the chair of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, chaired the meeting in the hope of bridging Cold War divisions, but later wrote that "there was no discussion in the ordinary sense of the word." Speakers delivered lengthy condemnation of the West and praises of the Soviet Union. Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

had been invited to send an address, but when the organisers found that it advocated world government and that his representative refused to change it, they substituted another document by Einstein without his consent, leaving Einstein feeling that he had been badly used.

The Congress elected a permanent International Committee of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace (also known as the International Committee of Intellectuals for Peace and the International Liaison Committee of Intellectuals for Peace) with headquarters in Paris. It called for the establishment of national branches and national meetings along the same lines as the World Congress. In accordance with this policy, a Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international organization created in 1949 by the Cominform and propped up by the Soviet Union. Throughout the Cold War, WPC engaged in propaganda efforts on behalf of the Soviet Union, whereby it criticized ...

was held in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in March 1949 at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel Waldorf can have the following meanings:

People

* Stephen Waldorf (born 1957), film editor

* William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor (1848–1919), financier and statesman

* Waldorf Astor, 2nd Viscount Astor (1879–1952), businessman and po ...

, sponsored by the National Council of Arts, Sciences and Professions The National Council of (the) Arts, Sciences and Professions (NCASP or ASP) was a United States–based socialist organization of the 1950s. Entertainment trade publication ''Box Office'' characterized the ASP as, "an independent organization to su ...

.Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty an ...

''Report on the Communist "peace" offensive. A campaign to disarm and defeat the United States'', 1951

/ref>

Paris and Prague 1949

The World Congress of Partisans for Peace in Paris (20 April 1949) repeated the Cominform line that the world was divided between "a non-aggressive Soviet group and a war-minded imperialistic group, headed by the United States government". It established a World Committee of Partisans for Peace, led by a twelve-person Executive Bureau and chaired by ProfessorFrédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist, High Commissioner for Atomic Energy and member of the French Institute

The ; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the . It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute manages approximately ...

. Most of the Executive were Communists.Santi, Rainer''100 years of Peace Making: A History of the International Peace Bureau and other international peace movement organisations and networks''

, Pax förlag, International Peace Bureau, January 1991. One delegate to the Congress, the Swedish artist , heard no spontaneous contributions or free discussions, only prepared speeches, and described the atmosphere there as "agitated", "aggressive" and "warlike". A speech given at Paris by

Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

—the polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

lawyer, folksinger, and actor son of a runaway slave

''Runaway Slave'' is the debut studio album by American hip hop duo Showbiz and A.G. It was released on September 22, 1992, via Payday/London Records. The album was produced by Showbiz and fellow D.I.T.C. crew member Diamond D. It features g ...

—was widely quoted in the American press for stating that African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

should not and would not fight for the United States in any prospective war against the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

; following his return, he was subsequently blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

and his passport confiscated for years. The Congress was disrupted by the French authorities who refused visas to so many delegates that a simultaneous Congress was held in Prague." Robeson's performance of "The March of the Volunteers

The "March of the Volunteers", originally titled the "March of the Anti-Manchukuo Counter-Japan Volunteers", is the official national anthem of the People's Republic of China since 1978. Unlike previous Chinese state anthems, it was written e ...

" in Prague for the delegation from the incipient People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

was its earliest formal use as the country's national anthem. Picasso's lithograph, ''La Colombe'' (The Dove) was chosen as the emblem for the Congress and was subsequently adopted as the symbol of the WPC.

Sheffield and Warsaw 1950

In 1950, the World Congress of the Supporters of Peace adopted a permanent constitution for the World Peace Council, which replaced the Committee of Partisans for Peace. The opening congress of the WPC condemned the atom-bomb and the American involvement in the Korean War. The WPC was used by the Soviet Union to promote baseless claims that the United States used biological weapons in theKorean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

It followed the Cominform line, recommending the creation of national peace committees in every country, and rejected pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

and the non-aligned peace movement. It was originally scheduled for Sheffield but the British authorities, who wished to undermine the WPC, refused visas to many delegates and the Congress was forced to move to Warsaw. British Prime Minister Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

denounced the Congress as a "bogus forum of peace with the real aim of sabotaging national defence" and said there would be a "reasonable limit" on foreign delegates. Among those excluded by the government were Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Ilya Ehrenburg

Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (, ; – August 31, 1967) was a Soviet writer, revolutionary, journalist and historian.

Ehrenburg was among the most prolific and notable authors of the Soviet Union; he published around one hundred titles. He becam ...

, Alexander Fadeyev, and Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

. The number of delegates at Sheffield was reduced from an anticipated 2,000 to 500, half of whom were British.

1950s

The WPC was directed by the International Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party through the

The WPC was directed by the International Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party through the Soviet Peace Committee The Soviet Peace Committee (SPC, also known as Soviet Committee for the Defense of Peace, SCDP, ) was a state-sponsored organization responsible for coordinating peace movements active in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1949 and existed until t ...

, although it tended not to present itself as an organ of Soviet foreign policy, but rather as the expression of the aspirations of the "peace loving peoples of the world".

In its early days the WPC attracted numerous "political and intellectual superstars", including W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

, Howard Fast

Howard Melvin Fast (November 11, 1914 – March 12, 2003) was an American novelist and television writer. Fast also wrote under the pen names E.V. Cunningham and Walter Ericson.

Biography Early life

Fast was born in New York City. His mother, ...

, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

, Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon (; 3 October 1897 – 24 December 1982) was a French poet who was one of the leading voices of the Surrealism, surrealist movement in France. He co-founded with André Breton and Philippe Soupault the surrealist review ''Littératur ...

, Jorge Amado

Jorge Amado ( 10 August 1912 – 6 August 2001) was a Brazilian writer of the modernist school. He remains the best-known of modern Brazilian writers, with his work having been translated into some 49 languages and popularized in film, includi ...

, Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda ( ; ; born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto; 12 July 190423 September 1973) was a Chilean poet-diplomat and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. Neruda became known as a poet when he was 13 years old an ...

, György Lukacs

György () is a Hungarian version of the name '' George''. Some notable people with this given name:

* György Alexits (1899–1978), Hungarian mathematician

* György Almásy (1867–1933), Hungarian asiologist, traveler, zoologist and ethnog ...

, Renato Guttuso

Aldo Renato Guttuso (26 December 1911 – 18 January 1987) was an Italian painter and politician. He is considered to be among the most important Italian artists of the 20th century and is among the key figures of Italian expressionism. His art i ...

, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

, Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

,"Congress For Peace - Vienna 1952"(book), ''A History of the World in 100 Objects''. Muhammad al-Ashmar and

Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

. Most were Communists or fellow travellers

A fellow traveller (also fellow traveler) is a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member. In the early history of the Sov ...

.

In the 1950s, congresses were held in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Berlin, Helsinki and Stockholm. The January 1952 World Congress of People in Vienna represented Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's strategy of peaceful coexistence, resulting in a more broad-based conference. Among those attending were Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

and Hervé Bazin

Hervé Bazin (; 17 April 191117 February 1996) was a French writer, whose best-known novels covered semi-autobiographical topics of teenage rebellion and dysfunctional families.

Biography

Bazin, born Jean-Pierre Hervé-Bazin in Angers, Maine ...

. In 1955, another WPC meeting in Vienna launched an "Appeal against the Preparations for Nuclear War", with grandiose claims about its success.

Following the Soviet invasion of Hungary

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

in 1956, the WPC convened a conference in Helsinki in December 1956. Although there were reportedly "serious differences" regarding the Hungarian situation within both the WPC and national peace movements, the conference passed a unanimous resolution blaming the Hungarian government for the Soviet invasion, citing "the faults of an internal regime as well as their exploitation by foreign propagandists". The resolution also called for the withdrawal of Soviet troops and the restoration of Hungarian sovereignty.

The WPC led the international peace movement in the decade after the Second World War, but its failure to speak out against the Soviet suppression of the 1956 Hungarian uprising

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

and the resumption of Soviet nuclear tests in 1961 marginalised it, and in the 1960s it was eclipsed by the newer, non-aligned peace organizations like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

. At first, Communists denounced the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament for "splitting the peace movement" but they were compelled to join it when they saw how popular it was.

1960s

Throughout much of the 1960s and early 1970s, the WPC campaigned against the US's role in theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. Opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* ''The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Comedy ...

to the Vietnam War was widespread in the mid-1960s and most of the anti-war activity had nothing to do with the WPC, which decided, under the leadership of J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular boo ...

, to take a softer line with non-aligned peace groups in order to secure their co-operation. In particular, Bernal believed that the WPC's influence with these groups was jeopardized by China's insistence that the WPC give unequivocal support to North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

in the war.Wernicke, Günther, "The World Peace Council and the Antiwar Movement in East Germany", in Daum, A. W., L. C. Gardner and W. Mausbach (eds), ''America, The Vietnam War and the World'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

In 1968, the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The ...

occasioned unprecedented dissent from Soviet policy within the WPC. It brought about such a crisis in the Secretariat that in September that year only one delegate supported the invasion. However, the Soviet Union soon reasserted control, and according to the US State Department, "The WPC's eighth world assembly in East Berlin in June 1969 was widely criticized by various participants for its lack of spontaneity and carefully orchestrated Soviet supervision. As the British General Secretary of the International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace and a delegate to the 1969 assembly wrote (''Tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

'', 4 July 1969): 'There were a number f delegateswho decided to vote against the general resolution for three reasons (a) it was platitudinous (b) it was one sided and (c) in protest against restrictions on minorities and the press within the assembly. This proved impossible in the end for no vote was taken.'"

Activities

Until the late 1980s, the World Peace Council's principal activity was the organization of large international congresses, nearly all of which had over 2,000 delegates representing most of the countries of the world. Most of the delegates came from pro-Communist organizations, with some observers from non-aligned bodies. There were also meetings of the WPC Assembly, its highest governing body. The congresses and assemblies issued statements, appeals and resolutions that called for world peace in general terms and condemned US weapons policy, invasions and military actions. The US Department of State described the congresses as follows: "The majority of participants in the assemblies are Soviet and East European communist party members, representatives of foreign communist parties, and representatives of other Soviet-backed international fronts. Token noncommunist participation serves to lend an element of credibility. Discussion usually is confined to the inequities of Western socioeconomic systems and attacks on the military and foreign policies of the United States and other imperialist, fascist nations. Resolutions advocating policies favored by the U.S.S.R. and other communist nations are passed by acclamation, not by vote. In most cases, delegates do not see the texts until they are published in the communist media. Attempts by noncommunist delegates to discuss Soviet actions (such as theinvasion of Afghanistan

Shortly after the September 11 attacks in 2001, the United States declared the war on terror and subsequently led a multinational military operation against Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. The stated goal was to dismantle al-Qaeda, which had exe ...

) are dismissed as interference in internal affairs or anti-Soviet propaganda. Dissent among delegates often is suppressed and never acknowledged in final resolutions or communiques. All assemblies praise the U.S.S.R. and other progressive societies and endorse Soviet foreign policy positions."

The WPC was involved in demonstrations and protests especially in areas bordering US military installation

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and Military operation, operations. A military base always provides ...

s in Western Europe believed to house nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s. It campaigned against US-led military operations, especially the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, although it did not condemn similar Soviet actions in Hungary and in Afghanistan.

On 18 March 1950, the WPC launched its Stockholm Appeal at a meeting of the Permanent Committee of the World Peace Congress, calling for the absolute prohibition of nuclear weapons. The campaign won popular support, collecting, it is said, 560 million signatures in Europe, most from socialist countries, including 10 million in France (including that of the young Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

), and 155 million signatures in the Soviet Union – the entire adult population. Several non-aligned peace groups who had distanced themselves from the WPC advised their supporters not to sign the Appeal.

In June 1975 the WPC launched a second Stockholm Appeal during a period of détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

between East and West. It declared that, "The victories of peace and détente have created a new international climate, new hopes, new confidence, new optimism among the peoples."

In the 1980s it campaigned against the deployment of U.S. missiles in Europe.

It published two magazines, ''New Perspectives'' and ''Peace Courier''. Its current magazine is ''Peace Messenger''.

Associated groups

In accordance with the Comniform's 1950 resolution to draw into the peace movement trade unions, women's and youth organisations, scientists, writers and journalists, etc., several Communist mass organisations supported the WPC, for example: *Christian Peace Conference

The Christian Peace Conference () was an international organization based in Prague and founded in 1958 by Josef Hromádka, a pastor who had spent the war years in the United States, moving back to Czechoslovakia when the war ended and Heinrich V ...

* International Federation of Resistance Fighters

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

* International Institute for Peace

The International Institute For Peace (IIP) was established in Vienna, Austria, in 1956 to conduct research on peace and promote the peaceful resolution of conflict. Operating globally alongside organizations like the Economic and Social Council ...

* International Association of Democratic Lawyers

International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) is an international organization of left-wing and progressive jurists' associations with sections and members in 50 countries and territories. Along with facilitating contact and exchange of v ...

* International Organization of Journalists

Logotype of the IOJ

The International Organization of Journalists (IOJ, ) was an international press workers' organization based in Prague, Czechoslovakia, during the Cold War. It was one of dozens of front organizations launched by the Soviet Un ...

* International Union of Students

The International Union of Students (IUS) was a worldwide nonpartisan association of university student organizations.

The IUS was the umbrella organization for 155 such students' organizations across 112 countries and Territory (administrative ...

* World Federation of Democratic Youth

The world is the totality of entities, the whole of reality, or everything that exists. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique, while others talk of a "plu ...

* World Federation of Scientific Workers

The World Federation of Scientific Workers (WFSW) is an international federation of scientific associations. It is an NGO in official partnership with Unesco. Its goal is to be involved internationally in all aspects of the role of science, the ...

* World Federation of Trade Unions

The World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) is an international federation of trade union, trade unions established on October 3, 1945. Founded in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, the organization built on the pre-war legacy of the Int ...

''Effect of Invasion of Czechoslovakia on Soviet Fronts'', CIA. *

Women's International Democratic Federation

The Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) is an international women's rights organization. Established in 1945, it was most active during the Cold War when, according to historian Francisca de Haan, it was "the largest and probably ...

Relations with non-aligned peace groups

The WPC has been described as caught in contradictions as "it sought to become a broad world movement while being instrumentalized increasingly to serve foreign policy in the Soviet Union and nominally socialist countries." From the 1950s until the late 1980s it tried to use non-aligned peace organizations to spread the Soviet point of view, alternately wooing and attacking them, either for their pacifism or their refusal to support the Soviet Union. Until the early 1960s there was limited co-operation between such groups and the WPC, but they gradually dissociated themselves as they discovered it was impossible to criticize the Soviet Union at WPC conferences. From the late 1940s to the late 1950s the WPC, with its large budget and high-profile conferences, dominated the peace movement, to the extent that the movement became identified with the Communist cause. The formation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Britain in 1957 sparked a rapid growth in the unaligned peace movement and its detachment from the WPC. However, the public and some Western leaders still tended to regard all peace activists as Communists. For example, US PresidentRonald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

said that the big peace demonstrations in Europe in 1981 were "all sponsored by a thing called the World Peace Council, which is bought and paid for by the Soviet Union",E. P. Thompson, "Resurgence in Europe and the rôle of END", in J. Minnion and P. Bolsover (eds), ''The CND Story'', London: Allison and Busby

Allison & Busby (A & B) is a publishing house based in London established by Clive Allison and Margaret Busby in 1967. The company has built up a reputation as a leading independent publisher.

Background

Launching as a publishing company in May ...

, 1983. and Soviet defector Vladimir Bukovsky

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Soviet and Russian Human rights activists, human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the Soviet dissid ...

claimed that they were co-ordinated at the WPC's 1980 World Parliament of Peoples for Peace in Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

. The FBI reported to the United States House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

that the WPC-affiliated U.S. Peace Council

The U.S. Peace Council is a peace and disarmament activist organization founded in 1979. It is affiliated with the World Peace Council and represents its American section. Its current president is Alfred Marder.

Backdrop

In the early 1980s, NAT ...

was one of the organizers of a large 1982 peace protest in New York City, but said that the KGB had not manipulated the American movement "significantly."John Kohan"The KGB: Eyes of the Kremlin"

''Time'', 14 February 1983.

International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War

International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) is a non-partisan federation of national medical groups in 63 countries, representing doctors, medical students, other health workers, and concerned people who share the goal of ...

was said to have had "overlapping membership and similar policies" to the WPC.U.S. Congress. House. Select Committee on Intelligence, ''Soviet Covert Action: The Forgery Offensive'', 6 and 19 Feb. 1980, 96th Cong., 2d sess., 1963. Washington, DC: GPO, 1980. and the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs is an international organization that brings together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats. It was fo ...

and the Dartmouth Conferences were said to have been used by Soviet delegates to promote Soviet propaganda. Joseph Rotblat

Sir Joseph Rotblat (4 November 1908 – 31 August 2005) was a Polish and British physicist. During World War II he worked on Tube Alloys and the Manhattan Project, but left the Los Alamos Laboratory on grounds of conscience after it became ...

, one of the leaders of the Pugwash movement, said that although a few participants in Pugwash conferences from the Soviet Union "were obviously sent to push the party line ... the majority were genuine scientists and behaved as such".

As the non-aligned peace movement "was constantly under threat of being tarnished by association with avowedly pro-Soviet groups", many individuals and organizations "studiously avoided contact with Communists and fellow-travellers." Some western delegates walked out of the Wrocław conference of 1948, and in 1949 the World Pacifist Meeting warned against active collaboration with Communists. In the same year, several members of the British Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

, including Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Fir ...

, Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten as o ...

, and Sybil Morrison, criticised the WPC-affiliated British Peace Committee for what they saw as its "unquestioning hero-worship" of the Soviet Union. In 1950, several Swedish peace organizations warned their supporters against signing the WPC's Stockholm Appeal. In 1953, the International Liaison Committee of Organizations for Peace

The International Peace Bureau (IPB; ), founded in 1891, is one of the world's oldest international peace federations. The organisation was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1910 for acting "as a link between the peace societies of the various ...

stated that it had "no association with the World Peace Council". In 1956, a year in which the WPC condemned the Suez war

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

but not the Russian suppression of the 1956 Hungarian uprising, the German section of War Resisters International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 40 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 un ...

condemned it for its failure to respond to Soviet H-bomb tests. In Sweden, Aktionsgruppen Mot Svensk Atombomb discouraged its members from participating in Communist-led peace committees. The WPC attempted to co-opt the eminent peace campaigner Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, much to his annoyance, and in 1957 he refused the award of the WPC's International Peace Prize. In Britain, CND

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucle ...

advised local groups in 1958 not to participate in a forthcoming WPC conference. In the US, SANE rejected WPC appeals for co-operation. A final break occurred during the WPC's 1962 World Congress for Peace and Disarmament in Moscow. The WPC had invited non-aligned peace groups, who were permitted to criticize Soviet nuclear testing, but when western activists including the British Committee of 100 tried to demonstrate in Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', p=ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːɪtʲ) is one of the oldest and largest town square, squares in Moscow, Russia. It is located in Moscow's historic centre, along the eastern walls of ...

against Soviet weapons and the Communist system, their banners were confiscated and they were threatened with deportation."Moscow Peace Congress: Criticism Allowed", ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', October 1982p. 42

As a result of this confrontation, 40 non-aligned organizations decided to form a new international body, the

International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace The International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace was an organisation formed by peace groups from western and non-aligned nations in 1963.

As a result of confrontation between western and Soviet delegates at the 1962 World Congress for Pea ...

, which was not to have Soviet members.Donald Keys and Homer A. Jack"Oxford Conference of Non-aligned Peace Organizations"

, 30 January 1963. From about 1982, following the proclamation of

martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland () existed between 13 December 1981 and 22 July 1983. The Polish United Workers' Party, government of the Polish People's Republic drastically restricted everyday life by introducing martial law and a military junta in an a ...

, the Soviet Union adopted a harder line with non-aligned groups, apparently because their failure to prevent the deployment of Cruise and Pershing Pershing may refer to:

Military

* John J. Pershing (1860–1948), U.S. General of the Armies

** MGM-31 Pershing, U.S. ballistic missile system

** Pershing II Weapon System, U.S. ballistic missile

** M26 Pershing, U.S. tank

** Pershing boot, a type ...

missiles.Bacher, John"The Independent Peace Movements in Eastern Europe"

, ''Peace Magazine'', December 1985. In December 1982, the Soviet Peace Committee President, Yuri Zhukov, returning to the rhetoric of the mid-1950s, wrote to several hundred non-communist peace groups in Western Europe accusing the

Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation

The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, established in 1963, continues the work of the philosopher and activist Bertrand Russell in the areas of peace, social justice, and human rights, with a specific focus on the dangers of nuclear war. Ken Coates ...

of "fueling the cold war by claiming that both NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

and the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

bear equal responsibility for the arms race and international tension. Zhukov denounced the West Berlin Working Group for a Nuclear-Free Europe, organizers of a May 1983 European disarmament conference in Berlin, for allegedly siding with NATO, attempting to split the peace movement, and distracting the peaceloving public from the main source of the deadly threat posed against the peoples of Europe-the plans for stationing a new generation of nuclear missiles in Europe in 1983." In 1983, the British peace campaigner E. P. Thompson

Edward Palmer Thompson (3 February 1924 – 28 August 1993) was an English historian, writer, socialist and peace campaigner. He is best known for his historical work on the radical movements in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in partic ...

, a leader of European Nuclear Disarmament

European Nuclear Disarmament (END) was a Europe-wide movement for a "nuclear-free Europe from Poland to Portugal” that put on annual European Nuclear Disarmament conventions from 1982 to 1991.

Origins

The founding statement of END was the Eu ...

, attended the World Peace Council's World Assembly for Peace and Life Against Nuclear War in Prague at the suggestion of the Czech dissident group Charter 77

Charter 77 (''Charta 77'' in Czech language, Czech and Slovak language, Slovak) was an informal civic initiative in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic from 1976 to 1992, named after the document Charter 77 from January 1977. Founding members ...

and raised the issue of democracy and civil liberties in the Communist states, only for Assembly to respond by loudly applauding a delegate who said that "the so-called dissident issue was not a matter for the international peace movement, but something that had been injected into it artificially by anti-communists." The Hungarian student peace group, Dialogue, also tried to attend the 1983 Assembly but were met with tear gas, arrests, and deportation to Hungary; the following year the authorities banned it.

Rainer Santi, in his history of the International Peace Bureau

The International Peace Bureau (IPB; ), founded in 1891, is one of the world's oldest international peace federations. The organisation was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1910 for acting "as a link between the peace societies of the various ...

, said that the WPC "always had difficulty in securing cooperation from West European and North American peace organisations because of its obvious affiliation with Socialist countries and the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. Especially difficult to digest, was that instead of criticising the Soviet Union's unilaterally resumed atmospheric nuclear testing in 1961, the WPC issued a statement rationalizing it. In 1979 the World Peace Council explained the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan as an act of solidarity in the face of Chinese and US aggression against Afghanistan." Rob Prince, a former secretary of the WPC, suggested that it simply failed to connect with the western peace movement because it used most of its funds on international travel and lavish conferences. It had poor intelligence on Western peace groups, and, even though its HQ was in Helsinki, had no contact with Finnish peace organizations.

After the demise of the Soviet Union

By the mid-1980s the Soviet Peace Committee "concluded that the WPC was a politically expendable and spent force", although it continued to provide funds until 1991. As the Soviet Peace Committee was the conduit for Soviet direction of the WPC, this judgement represented a downgrading of the WPC by the Soviet Communist Party. UnderMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, the Soviet Peace Committee developed bilateral international contacts "in which the WPC not only played no role, but was a liability." Gorbachev never even met WPC President Romesh Chandra

Romesh Chandra (30 March 1919 – 4 July 2016) was a leader of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the president of the World Peace Council from 1977 to 1990. He joined the CPI in 1939 and took part in the Indian independence struggle ...

and excluded him from many Moscow international forums.Prince, R."The Ghost Ship of Lönnrotinkatu"

, ''Peace Magazine'', May–June 1992. Following the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union, the WPC lost most of its support, income and staff and dwindled to a small core group. Its international conferences now attract only a tenth of the delegates that its Soviet-backed conferences could attract ( see below), although it still issues statements couched in similar terms to those of its historic appeals.

Location

The WPC first set up its offices in Paris, but was accused by the French government of engaging in "fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

" activities and was expelled in 1952. It moved to Prague and then to Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

.Clews, John, ''Communist Propaganda Techniques'', New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964 In 1957 it was banned by the Austrian government. It was invited to Prague but did not move there, had no official HQ but continued to operate in Vienna under cover of the International Institute for Peace.Barlow, J. G.''Moscow and the Peace Offensive''

, 1982. In 1968 it re-assumed its name and moved to Helsinki,

Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, where it remained until 1999. In 2000 it re-located to Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Greece.

Funding

The WPC was receiving financial contributions from friendly countries and from the Soviet Peace Committee during its history until 1991.Richard Felix Staar''Foreign Policies of the Soviet Union''

, Hoover Press, 1991, , pp. 79–88. After the year 2000 and the shifting of the Head office to

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, its current finances derive exclusively from Membership Fees and contributions/donations by members and friends, based on the rules and regulations adopted in 2008, during the 19th Assembly of the WPC held in Caracas/Venezuela. The executive committee and Assemblies receive financial reports on income and expenses.

Allegations of CIA measures against the WPC

TheCongress for Cultural Freedom

The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was an anti-communist cultural organization founded on 26 June 1950 in West Berlin. At its height, the CCF was active in thirty-five countries. In 1966 it was revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency w ...

was founded in 1950 with the support of the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

to counter the propaganda of the emerging WPC, and Phillip Agee

Philip Burnett Franklin Agee (; January 19, 1935 – January 7, 2008) was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) case officer and writer of the 1975 bestseller, ''Inside the Company: CIA Diary'', detailing his experiences in the Agency. Age ...

claimed that the WPC was a Soviet front for propaganda which CIA covertly tried to neutralize and to prevent the WPC from organizing outside the Communist bloc.

Current organisation

The WPC currently states its goals as: Actions against imperialist wars and occupation of sovereign countries and nations; prohibition of all weapons of mass destruction; abolition of foreign military bases; universal disarmament under effective international control; elimination of all forms ofcolonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

, racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but primarily affects women and girls. It has been linked to gender roles and stereotypes, and may include the belief that one sex or gender is int ...

and other forms of discrimination; respect for the right of peoples to sovereignty and independence, essential for the establishment of peace; non-interference in the internal affairs of nations; peaceful co-existence between states with different political systems; negotiations instead of use of force in the settlement of differences between nations.

The WPC is a registered NGO at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and co-operates primarily with the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

. It cooperates with United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

(UNESCO), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) is an intergovernmental organization within the United Nations Secretariat that promotes the interests of developing countries in world trade. It was established in 1964 by the United Nations General Assembl ...

(UNCTAD), United Nations Industrial Development Organization

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (French: Organisation des Nations unies pour le développement industriel; French/Spanish acronym: ONUDI) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that assists countries in e ...

(UNIDO), International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the firs ...

(ILO), and other UN specialized agencies, special committees and departments. It is said to have successfully influenced their agendas, the terms of discussion and the orientations of their resolutions. It also cooperates with the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, the League of Arab States

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

* ''League of Legends'', a 2009 multiplayer online battle a ...

, and other inter-governmental bodies.

Leadership

*President:Pallab Sengupta

Basirhat Lok Sabha constituency is one of the 543 parliamentary constituencies in India. The constituency centres on Basirhat in West Bengal. All the seven assembly segments of No. 18 Basirhat Lok Sabha constituency are in North 24 Pargana ...

, All India Peace and Solidarity Organisation (AIPSO)

*General Secretary: Thanasis Pafilis

Athanasios Pafilis (Greek: Αθανάσιος Παφίλης) (born 8 November 1954) is a Greek communist politician, member of the Hellenic Parliament and member of the central committee of the Communist Party of Greece. He is also the General S ...

, Greek Committee for International Détente and Peace (EEDYE)

*Executive Secretary: Iraklis Tsavdaridis, Greek Committee for International Détente and Peace (EEDYE)

Secretariat

The members of the Secretariat of the WPC are: * All India Peace and Solidarity Organization (AIPSO) * Brazilian Center for Solidarity with the People and the Struggle for Peace (CEBRAPAZ) *Greek Committee for International Détente and Peace

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(EEDYE)

* South African Peace Initiative (SAPI)

* Sudan Peace and Solidarity Council (SuPSC)

* Cuban Institute for the Friendship of the Peoples (ICAP)

* US Peace Council (USPC)

* Japan Peace Committee

*Portuguese Council for Peace and Cooperation

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

(CPPC)

* Palestinian Committee for Peace and Solidarity (PCPS)

* Nepal Peace and Solidarity Council (NPSC)

* Cyprus Peace Council (CyPC)

* Syrian National Peace Council (SNPC)

Peace prizes

The WPC awards several peace prizes, some of which, it has been said, were awarded to politicians who funded the organization.Prince, Rob''The Last of the WPC Mohicans''

, The View from the Left Bank, 1 August 2011.

Congresses and assemblies

The highest WPC body, the Assembly, meets every three years.WPC Assemblies

*The World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace

The World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace () was an international conference held on 25 to 28 August 1948 at Wrocław University of Technology. It was organized in the aftermath of the Second World War by the authorities of the Poli ...

held in Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

on 6 August 1948 established the International Committee of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace.

* The World Congress of Partisans for Peace held on 20 April 1949 Paris & Prague established a World Committee of Partisans for Peace, which is considered the founding Congress of the WPC

*#Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

& Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, April 1949

*#Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, November 1950

*#Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, December 1952

*#Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

, June 1955

*#Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

, July 1958

*#Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, July 1962

*#Helsinki

Helsinki () is the Capital city, capital and most populous List of cities and towns in Finland, city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipali ...

, July 1965

*#Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, June 1969

*#Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

, May 1971

*#Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, October 1973

*#Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, May 1977

*#Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, September 1980

*#Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, June 1983

*#Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, April 1986

*#Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, May 1990

*#Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

, October 1996

*#Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, May 2000

*#Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, May 2004

*#Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

, April 2008

*#Kathmandu

Kathmandu () is the capital and largest city of Nepal, situated in the central part of the country within the Kathmandu Valley. As per the 2021 Nepal census, it has a population of 845,767 residing in 105,649 households, with approximately 4 mi ...

, July 2012

*# São Luís, November 2016

*#Hanoi

Hanoi ( ; ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Vietnam, second-most populous city of Vietnam. The name "Hanoi" translates to "inside the river" (Hanoi is bordered by the Red River (Asia), Red and Black River (Asia), Black Riv ...

, November 2022

Presidents

*Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

(1950–58)

* John Desmond Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular boo ...

(1959–65)

* Isabelle Blume (1965–69)

* Romesh Chandra

Romesh Chandra (30 March 1919 – 4 July 2016) was a leader of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the president of the World Peace Council from 1977 to 1990. He joined the CPI in 1939 and took part in the Indian independence struggle ...

(General Secretary in 1966–1977; President in 1977–90)

* Evangelos Maheras (1990–93)

* Albertina Sisulu

Albertina Sisulu Order for Meritorious Service, OMSG ( Nontsikelelo Thethiwe; 21 October 1918 – 2 June 2011) was a South African anti-apartheid activist. A member of the African National Congress (ANC), she was the founding co-president of th ...

(1993–2002)

* Niranjan Singh Maan (General Secretary)

* Orlando Fundora López

Orlando commonly refers to:

* Orlando, Florida, a city in the United States

Orlando may also refer to:

People

* Orlando (given name), a masculine name, includes a list of people with the name

* Orlando (surname), includes a list of people with ...

(2002–08)

* Maria do Socorro Gomes Coelho (2008–2022)

* Pallab Sengupta

Basirhat Lok Sabha constituency is one of the 543 parliamentary constituencies in India. The constituency centres on Basirhat in West Bengal. All the seven assembly segments of No. 18 Basirhat Lok Sabha constituency are in North 24 Pargana ...

(2022-)

Current members

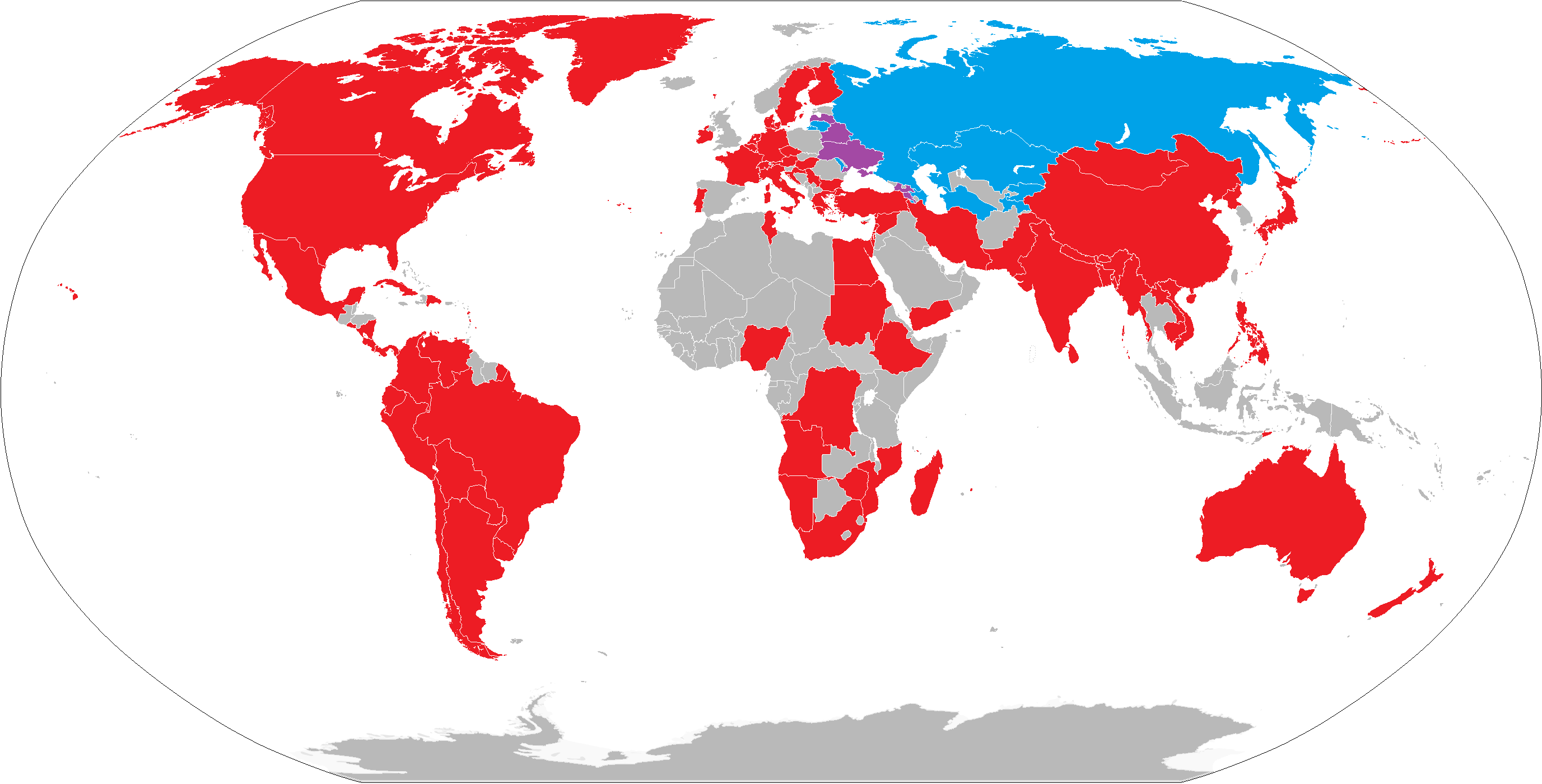

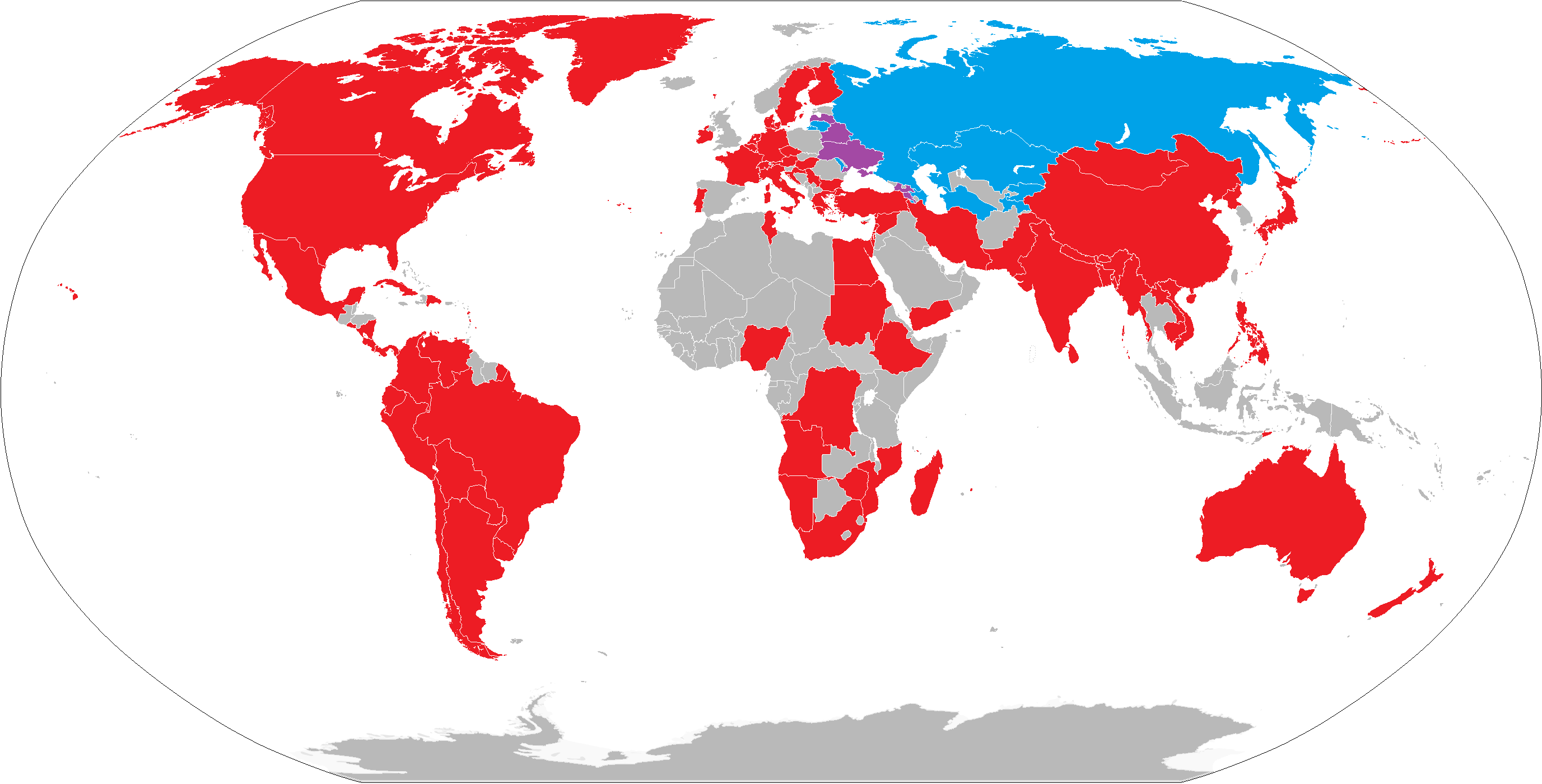

Under its current rules, WPC members are national and international organizations that agree with its main principles and any of its objectives and pay membership fees. Other organizations may join at the discretion of the executive committee or become associate members. Distinguished individuals may become honorary members at the discretion of the executive committee. As of March 2014, the WPC lists the following organizations among its "members and friends".Current Communist States

* Chinese Association for Peace and Disarmament *Cuban Movement for Peace and Sovereignty of the Peoples