Crusades Films on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Crusades were a series of

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor

Urban II died on 29 July 1099, fourteen days after the capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, but before news of the event had reached Rome. He was succeeded by

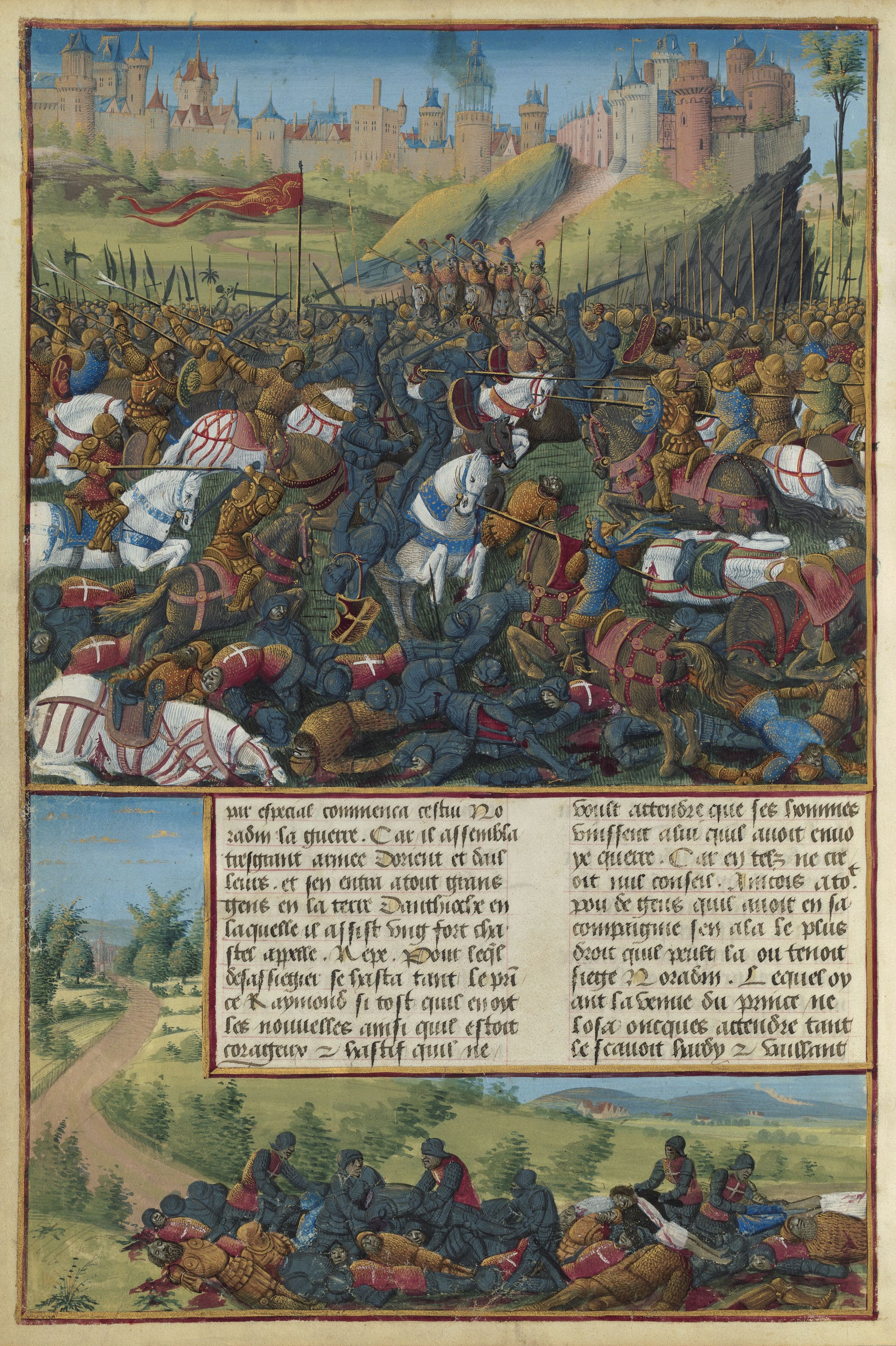

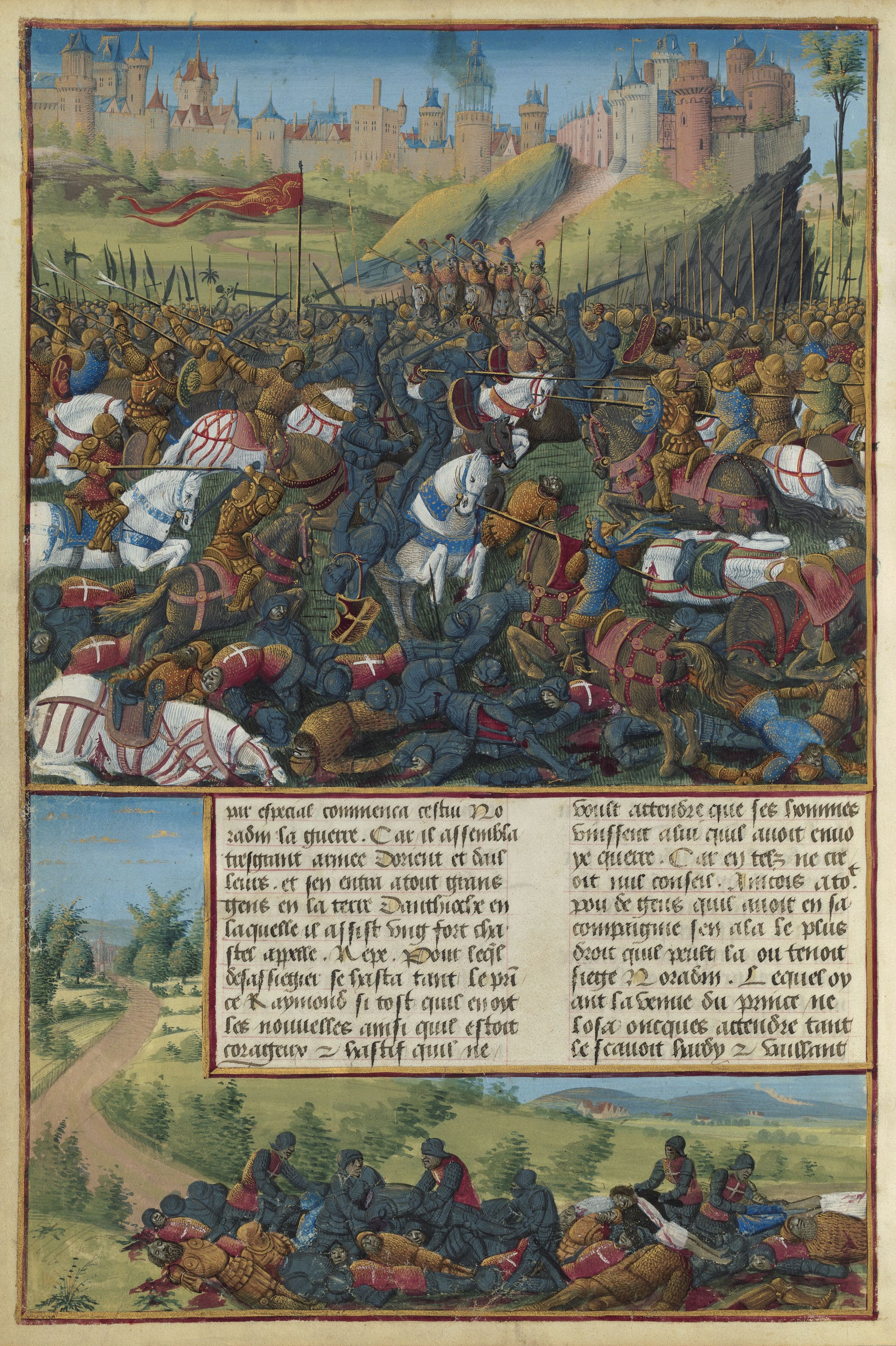

Urban II died on 29 July 1099, fourteen days after the capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, but before news of the event had reached Rome. He was succeeded by  In April 1118, Baldwin I died of illness while raiding in Egypt. His cousin, Baldwin of Edessa, was unanimously elected his successor. In June 1119, Ilghazi, now

In April 1118, Baldwin I died of illness while raiding in Egypt. His cousin, Baldwin of Edessa, was unanimously elected his successor. In June 1119, Ilghazi, now

Chapter XVII. The Latin States under Baldwin III and Amalric I, 1143–1174

. In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). ''A History of the Crusades: Volume One. The First Hundred Years''. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 528–563. Following John's death, the Byzantine army withdrew, leaving Zengi unopposed. Fulk's death later in the year left

The fall of Edessa caused great consternation in Jerusalem and Western Europe, tempering the enthusiastic success of the First Crusade. Calls for a new crusadethe

The fall of Edessa caused great consternation in Jerusalem and Western Europe, tempering the enthusiastic success of the First Crusade. Calls for a new crusadethe

Chapter XV. The Second Crusade

". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). ''A History of the Crusades: Volume One. The First Hundred Years''. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 463–512. The aftermath of the Crusade saw the Muslim world united around

Chapter XVIII. The Rise of Saladin, 1169–1189

". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). ''A History of the Crusades: Volume One. The First Hundred Years''. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 563–589.

After the

After the

Chapter XIX. The Decline and Fall of Jerusalem, 1174–1189

". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). ''A History of the Crusades: Volume One. The First Hundred Years''. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 590–621.

Frederick took the cross in March 1188.Johnson, Edgar N. (1977).

Frederick took the cross in March 1188.Johnson, Edgar N. (1977).

The Crusades of Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI

". In Setton, K., ''A History of the Crusades: Volume II.'' pp. 87–122. Frederick sent an ultimatum to Saladin, demanding the return of Palestine and challenging him to battle and in May 1189, Frederick's host departed for Byzantium. In March 1190, Frederick embarked to Asia Minor. The armies coming from western Europe pushed on through Anatolia, defeating the Turks and reaching as far as

In 1198, the recently elected Pope Innocent III announced a new crusade, organised by three Frenchmen: Theobald of Champagne; Louis of Blois; and Baldwin of Flanders. After Theobald's premature death, the Italian Boniface of Montferrat replaced him as the new commander of the campaign. They contracted with the

In 1198, the recently elected Pope Innocent III announced a new crusade, organised by three Frenchmen: Theobald of Champagne; Louis of Blois; and Baldwin of Flanders. After Theobald's premature death, the Italian Boniface of Montferrat replaced him as the new commander of the campaign. They contracted with the

The Fifth Crusade

". In Setton, K., ''A History of the Crusades: Volume II''. pp. 343–376. Andrew II left for Acre in August 1217, joining

Andrew II left for Acre in August 1217, joining

The

The

The Crusade of Frederick II

". In Setton, K. ''A History of the Crusades: Volume II''. pp. 377–448. Of all the European sovereigns, only Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, was in a position to regain Jerusalem. Frederick was, like many of the 13th-century rulers, a serial ''crucesignatus'', having taken the cross multiple times since 1215. After much wrangling, an onerous agreement between the emperor and Pope

In 1229, Frederick II and the Ayyubid sultan

In 1229, Frederick II and the Ayyubid sultan

The Crusades of 1239–1241 and Their Aftermath

. ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', Vol. 50, No. 1 (1987). pp. 32–60. On 1 September 1239, Theobald arrived in Acre, and was soon drawn into the Ayyubid civil war, which had been raging since the death of al-Kamil in 1238. At the end of September, al-Kamil's brother

The

The

Chapter XIV. The Crusades of Louis IX

". In Wolff, Robert L. and Hazard, H. W. (eds.). ''A History of the Crusades: Volume II, The Later Crusades 1187–1311''. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 487–521. At the end of 1244, Louis was stricken with a severe malarial infection and he vowed that if he recovered he would set out for a Crusade. His life was spared, and as soon as his health permitted him, he took the cross and immediately began preparations.James Thomson Shotwell (1911). " Louis IX. of France". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 17. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. The next year, the pope presided over On 28 February 1250, Turanshah arrived from Damascus and began an Egyptian offensive, intercepting the boats that brought food from Damietta. The Franks were quickly beset by famine and disease. The Battle of Fariskur fought on 6 April 1250 would be the decisive defeat of Louis' army. Louis knew that the army must be extricated to Damietta and they departed on the morning of 5 April, with the king in the rear and the Egyptians in pursuit. The next day, the Muslims surrounded the army and attacked in full force. On 6 April, Louis' surrender was negotiated directly with the sultan by Philip of Montfort. The king and his entourage were taken in chains to Mansurah and the whole of the army was rounded up and led into captivity.

The Egyptians were unprepared for the large number of prisoners taken, comprising most of Louis' force. The infirm were executed immediately and several hundred were decapitated daily. Louis and his commanders were moved to Mansurah, and negotiations for their release commenced. The terms agreed to were harsh. Louis was to ransom himself by the surrender of Damietta and his army by the payment of a million

On 28 February 1250, Turanshah arrived from Damascus and began an Egyptian offensive, intercepting the boats that brought food from Damietta. The Franks were quickly beset by famine and disease. The Battle of Fariskur fought on 6 April 1250 would be the decisive defeat of Louis' army. Louis knew that the army must be extricated to Damietta and they departed on the morning of 5 April, with the king in the rear and the Egyptians in pursuit. The next day, the Muslims surrounded the army and attacked in full force. On 6 April, Louis' surrender was negotiated directly with the sultan by Philip of Montfort. The king and his entourage were taken in chains to Mansurah and the whole of the army was rounded up and led into captivity.

The Egyptians were unprepared for the large number of prisoners taken, comprising most of Louis' force. The infirm were executed immediately and several hundred were decapitated daily. Louis and his commanders were moved to Mansurah, and negotiations for their release commenced. The terms agreed to were harsh. Louis was to ransom himself by the surrender of Damietta and his army by the payment of a million

The military expeditions undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, and 13thcenturies to recover the Holy Land from Muslims provided a template for warfare in other areas that also interested the Latin Church. These included the 12th and 13thcentury conquest of Muslim

The military expeditions undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, and 13thcenturies to recover the Holy Land from Muslims provided a template for warfare in other areas that also interested the Latin Church. These included the 12th and 13thcentury conquest of Muslim  By the beginning of the 13thcentury papal reticence in applying crusades against the papacy's political opponents and those considered heretics had abated. Innocent III proclaimed a crusade against Catharism that failed to suppress the heresy itself but ruined the culture of the

By the beginning of the 13thcentury papal reticence in applying crusades against the papacy's political opponents and those considered heretics had abated. Innocent III proclaimed a crusade against Catharism that failed to suppress the heresy itself but ruined the culture of the

According to the historian Joshua Prawer no major European poet, theologian, scholar or historian settled in the crusader states. Some went on pilgrimage, and this is seen in new imagery and ideas in western poetry. Although they did not migrate east themselves, their output often encouraged others to journey there on pilgrimage.

Historians consider the crusader military architecture of the Middle East to demonstrate a synthesis of the European, Byzantine and Muslim traditions and to be the most original and impressive artistic achievement of the crusades. Castles were a tangible symbol of the dominance of a Latin Christian minority over a largely hostile majority population. They also acted as centres of administration. Modern historiography rejects the 19th-century consensus that Westerners learnt the basis of military architecture from the Near East, as Europe had already experienced rapid development in defensive technology before the First Crusade. Direct contact with Arab fortifications originally constructed by the Byzantines did influence developments in the east, but the lack of documentary evidence means that it remains difficult to differentiate between the importance of this design culture and the constraints of situation. The latter led to the inclusion of oriental design features such as large water reservoirs and the exclusion of occidental features such as moats.

Typically, crusader church design was in the

According to the historian Joshua Prawer no major European poet, theologian, scholar or historian settled in the crusader states. Some went on pilgrimage, and this is seen in new imagery and ideas in western poetry. Although they did not migrate east themselves, their output often encouraged others to journey there on pilgrimage.

Historians consider the crusader military architecture of the Middle East to demonstrate a synthesis of the European, Byzantine and Muslim traditions and to be the most original and impressive artistic achievement of the crusades. Castles were a tangible symbol of the dominance of a Latin Christian minority over a largely hostile majority population. They also acted as centres of administration. Modern historiography rejects the 19th-century consensus that Westerners learnt the basis of military architecture from the Near East, as Europe had already experienced rapid development in defensive technology before the First Crusade. Direct contact with Arab fortifications originally constructed by the Byzantines did influence developments in the east, but the lack of documentary evidence means that it remains difficult to differentiate between the importance of this design culture and the constraints of situation. The latter led to the inclusion of oriental design features such as large water reservoirs and the exclusion of occidental features such as moats.

Typically, crusader church design was in the

Select Bibliography of the Crusades

. (A History of the Crusades, volume, VI) Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989, pp. 511–664. Modern Historiography'',Tyerman, Christopher (2006). "Historiography, Modern". ''The Crusades: An Encyclopedia''. pp. 582–588. and ''Crusades (Bibliography and Sources'').Bréhier, Louis René (1908). " Crusades (Sources and Bibliography)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. The histories describing the Crusades are broadly of three types: (1) The

religious wars

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a War, war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the exte ...

initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

and its surrounding territories from Muslim rule. Beginning with the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

, which culminated in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, these expeditions spanned centuries and became a central aspect of European political, religious, and military history.

In 1095, after a Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

request for aid,Helen J. Nicholson, ''The Crusades'', (Greenwood Publishing, 2004), 6. Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II (; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening the Council of Clermon ...

proclaimed the first expedition at the Council of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

While the council ...

. He encouraged military support for Byzantine emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

AlexiosI Komnenos and called for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in Western Europe, there was an enthusiastic response. Participants came from all over Europe and had a variety of motivations. These included religious salvation, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic or political advantage. Later expeditions were conducted by generally more organised armies, sometimes led by a king. All were granted papal indulgences

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for (forgiven) sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission bef ...

. Initial successes established four Crusader states

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

: the County of Edessa

The County of Edessa (Latin: ''Comitatus Edessanus'') was a 12th-century Crusader state in Upper Mesopotamia. Its seat was the city of Edessa (modern Şanlıurfa, Turkey).

In the late Byzantine period, Edessa became the centre of intellec ...

; the Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch (; ) was one of the Crusader states created during the First Crusade which included parts of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and History of Syria#Medieval era, Syria. The principality was much smaller than the County of ...

; the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1 ...

; and the County of Tripoli

The County of Tripoli (1102–1289) was one of the Crusader states. It was founded in the Levant in the modern-day region of Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli, northern Lebanon and parts of western Syria.

When the Crusades, Frankish Crusaders, mostly O ...

. A European presence remained in the region in some form until the fall of Acre

The siege of Acre (also called the fall of Acre) took place in 1291 and resulted in the Crusaders' losing control of Acre to the Mamluks. It is considered one of the most important battles of the period. Although the crusading movement continu ...

in 1291. After this, no further large military campaigns were organised.

Other church-sanctioned campaigns include crusades against Christians not obeying papal rulings and heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

, those against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and ones for political reasons. The struggle against the Moors

The term Moor is an Endonym and exonym, exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslims, Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a s ...

in the Iberian Peninsula–the ''Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

–''ended in 1492 with the Fall of Granada

The Granada War was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1492 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It ended with the defeat of G ...

. From 1147, the Northern Crusades

The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were Christianization campaigns undertaken by Catholic Church, Catholic Christian Military order (society), military orders and kingdoms, primarily against the paganism, pagan Balts, Baltic, Baltic Finns, ...

were fought against pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

tribes in Northern Europe. Crusades against Christians

Crusades against Christians were Christian religious wars dating from the 11thcentury First Crusade when papal reformers began equating the universal church with the papacy. Later in the 12th century the focus of crusades century focus changed ...

began with the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

in the 13th century and continued through the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, a ...

in the early 15th century. Crusades against the Ottomans began in the late 14th century and include the Crusade of Varna

The Crusade of Varna was an unsuccessful military campaign mounted by several European leaders to check the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Central Europe, specifically the Balkans between 1443 and 1444. It was called by Pope Eugene IV ...

. Popular crusades, including the Children's Crusade

The Children's Crusade was a failed Popular crusades, popular crusade by European Christians to establish a second Latin Church, Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Holy Land in the early 13th century. Some sources have narrowed the date to 1212. ...

of 1212, were generated by the masses and were unsanctioned by the Church.

Terminology

The term "crusade" first referred to military expeditions undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, and 13thcenturies to theHoly Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. The conflicts to which the term is applied have been extended to include other campaigns initiated, supported and sometimes directed by the Latin Church with varying objectives, mostly religious, sometimes political. These differed from previous Christian religious wars in that they were considered a penitential exercise, and so earned participants remittance from penalties for all confessed sins. What constituted a crusade has been understood in diverse ways, particularly regarding the early Crusades, and the precise definition remains a matter of debate among contemporary historians.

At the time of the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

, , "journey", and , "pilgrimage" were used for the campaign. Crusader terminology remained largely indistinguishable from that of Christian pilgrimage during the 12thcentury. A specific term for a crusader in the form of "one signed by the cross"emerged in the early 12th century. This led to the French term the way of the cross. By the mid 13thcentury the cross became the major descriptor of the crusades with "the cross overseas"used for crusades in the eastern Mediterranean, and "the cross this side of the sea"for those in Europe. The use of , "crusade" in Middle English can be dated to , but the modern English "crusade" dates to the early 1700s. The Crusader states

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

of Syria and Palestine were known as the "Outremer

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

" from the French ''outre-mer'', or "the land beyond the sea".

Crusades and the Holy Land, 1095–1291

Background

By the end of the 11thcentury, the period of Islamic Arab territorial expansion had been over for centuries. The Holy Land's remoteness from focus of Islamic power struggles enabled relative peace and prosperity in Syria and Palestine. Contact between the Muslim world and Western Europe was minimal outside theIberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. The Byzantine Empire and the Islamic world were long standing centres of wealth, culture and military power. The Arab-Islamic world tended to view Western Europe as a backwater that presented little organised threat. By 1025, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus (; 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar Slayer (, ), was the senior Byzantine emperor from 976 to 1025. He and his brother Constantine VIII were crowned before their father Romanos II died in 963, but t ...

had extended territorial recovery to its furthest extent. The frontiers stretched east to Iran. Bulgaria and much of southern Italy were under control, and piracy was suppressed in the Mediterranean Sea. The empire's relationships with its Islamic neighbours were no more quarrelsome than its relationships with the Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

or the Western Christians. The Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

in Italy; to the north Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks, , Middle Turkic languages, Middle Turkic: , , , , , , ka, პაჭანიკი, , , ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Pečenezi, separator=/, Печенези, also known as Pecheneg Turks were a semi-nomadic Turkic peopl ...

, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

and Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

; and Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turks, Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate society, Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persi ...

in the east all competed with the Empire and the emperors recruited mercenarieseven on occasions from their enemiesto meet this challenge.

The political situation in Western Asia was changed by later waves of Turkic migration

The Turkic migrations were the spread of Turkic peoples, Turkic tribes and Turkic languages across Eurasia between the 4th and 11th centuries. In the 6th century, the Göktürks overthrew the Rouran Khaganate in what is now Mongolia and expanded in ...

, in particular the arrival of the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turks, Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate society, Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persi ...

in the 10thcentury. Previously a minor ruling clan from Transoxania

Transoxiana or Transoxania (, now called the Amu Darya) is the Latin name for the region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tur ...

, they had recently converted to Islam and migrated into Iran. In two decades following their arrival they conquered Iran, Iraq and the Near East. The Seljuks and their followers were from the Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

tradition. This brought them into conflict in Palestine and Syria with the Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

who were Shi'ite

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood to ...

. The Seljuks were nomadic, Turkic speaking and occasionally shamanistic, very different from their sedentary, Arabic speaking subjects. This difference and the governance of territory based on political preference, and competition between independent princes rather than geography, weakened existing power structures. In 1071, Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes

Romanos IV Diogenes (; – ) was Byzantine emperor from 1068 to 1071. Determined to halt the decline of the Byzantine military and to stop Turkish incursions into the empire, he is nevertheless best known for his defeat and capture in 1071 at ...

attempted confrontation to suppress the Seljuks' sporadic raiding, leading to his defeat at the battle of Manzikert

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, Iberia (theme), Iberia (modern Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army ...

. Historians once considered this a pivotal event but now Manzikert is regarded as only one further step in the expansion of the Great Seljuk Empire

The Seljuk Empire, or the Great Seljuk Empire, was a high medieval, culturally Turco-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, established and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. The empire spanned a total area of from Anatolia and the Levant ...

.

The evolution of a Christian theology of war developed from the link of Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

to Christianity, according to which citizens were required to fight the empire's enemies. This doctrine of holy war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent t ...

dated from the 4th-century theologian Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman province), Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced th ...

. He maintained that aggressive war was sinful, but acknowledged a "just war

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. It has bee ...

" could be rationalised if it was proclaimed by a legitimate authority, was defensive or for the recovery of lands, and without an excessive degree of violence. Violent acts were commonly used for dispute resolution in Western Europe, and the papacy attempted to mitigate this. Historians have thought that the Peace and Truce of God

The Peace and Truce of God () was a movement in the Middle Ages led by the Catholic Church and was one of the most influential mass peace movements in history. The goal of both the ''Pax Dei'' and the ''Treuga Dei'' was to limit the violence o ...

movements restricted conflict between Christians from the 10thcentury; the influence is apparent in Urban II's speeches. Other historians assert that the effectiveness was limited and it had died out by the time of the crusades. Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform mo ...

developed a system of recruitment via oaths for military resourcing that his successor Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII (; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church.

One of the great ...

extended across Europe. In the 11thcentury, Christian conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom was sponsored by the Church, including the siege of Barbastro and the Norman conquest of Sicily

The Normans, Norman conquest of southern Italy lasted from 999 to 1194, involving many battles and independent conquerors. In 1130, the territories in southern Italy united as the Kingdom of Sicily, which included the island of Sicily, the sout ...

. In 1074, GregoryVII planned a display of military power to reinforce the principle of papal sovereignty. His vision of a holy war supporting Byzantium against the Seljuks was the first crusade prototype, but lacked support.

The First Crusade was an unexpected event for contemporary chroniclers, but historical analysis demonstrates it had its roots in earlier developments with both clerics and laity recognising Jerusalem's role in Christianity as worthy of penitential pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

. In 1071, Jerusalem was captured by the Turkish warlord Atsiz

Ala al-Din wa-l-Dawla Abu'l-Muzaffar Atsiz ibn Muhammad ibn Anushtegin (; 1098 – 1156), better known as Atsiz () was the second Khwarazmshah from 1127 to 1156. He was the son and successor of Muhammad I.

Ruler of Khwarazm Warfare with the ...

, who seized most of Syria and Palestine as part of the expansion of the Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persian culture.

The founder of th ...

throughout the Middle East. The Seljuk hold on the city was weak and returning pilgrims reported difficulties and the oppression of Christians. Byzantine desire for military aid converged with increasing willingness of the western nobility to accept papal military direction.

First Crusade

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos (, – 15 August 1118), Latinization of names, Latinized as Alexius I Comnenus, was Byzantine Emperor, Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. After usurper, usurping the throne, he was faced with a collapsing empire and ...

requested military aid from Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II (; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening the Council of Clermon ...

at the Council of Piacenza. He was probably expecting a small number of mercenaries he could direct. Alexios had restored the Empire's finances and authority but still faced numerous foreign enemies. Later that year at the Council of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

While the council ...

, Urban raised the issue again and preached a crusade. Almost immediately, the French priest Peter the Hermit

Peter the Hermit ( 1050 – 8 July 1115 or 1131), also known as Little Peter, Peter of Amiens (French language, fr. ''Pierre d'Amiens'') or Peter of Achères (French language, fr. ''Pierre d'Achères''), was a Roman Catholic priest of Amiens and ...

gathered thousands of mostly poor in the People's Crusade

The People's Crusade was the beginning phase of the First Crusade whose objective was to retake the Holy Land, and Jerusalem in particular, from Islamic rule. In 1095, after the head of the Roman Catholic Church Pope Urban II started to urge faith ...

. Traveling through Germany, German bands massacred Jewish communities in the Rhineland massacres

The Rhineland massacres, also known as the German Crusade of 1096 or ''Gzerot Tatnó'' (, "Edicts of 4856"), were a series of mass murders of Jews perpetrated by mobs of French and German Christians of the People's Crusade in the year 1096 ( ...

during wide-ranging anti-Jewish activities. Jews were perceived to be as much an enemy as Muslims. They were held responsible for the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

, and were more immediately visible. People wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were many closer to home. Quickly after leaving Byzantine-controlled territory on their journey to Nicaea

Nicaea (also spelled Nicæa or Nicea, ; ), also known as Nikaia (, Attic: , Koine: ), was an ancient Greek city in the north-western Anatolian region of Bithynia. It was the site of the First and Second Councils of Nicaea (the first and seve ...

, these crusaders were annihilated in a Turkish ambush at the Battle of Civetot

The Battle of Civetot was fought between the forces of the People's Crusade and of the Seljuk Turks of Anatolia on 21 October 1096. The battle brought an end to the People's Crusade; some of the survivors joined the Princes' Crusade.

Backgrou ...

.

Conflict with Urban II meant that King Philip I of France

Philip I ( – 29 July 1108), called the Amorous (French: ''L’Amoureux''), was King of the Franks from 1060 to 1108. His reign, like that of most of the early Capetians, was extraordinarily long for the time. The monarchy began a modest recove ...

and Holy Roman Emperor HenryIV declined to participate. Aristocrats from France, western Germany, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

and Italy led independent contingents in loose, fluid arrangements based on bonds of lordship, family, ethnicity and language. The elder statesman Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse

Raymond of Saint-Gilles ( 1041 – 28 February 1105), also called Raymond IV of Toulouse or Raymond I of Tripoli, was the count of Toulouse, duke of Narbonne, and margrave of Provence from 1094, and one of the leaders of the First Crusade from 10 ...

was foremost, rivaled by the relatively poor but martial Italo-Norman

The Italo-Normans (), or Siculo-Normans (''Siculo-Normanni'') when referring to Sicily and Southern Italy, are the Italian-born descendants of the first Norman conquerors to travel to Southern Italy in the first half of the eleventh century. ...

Bohemond of Taranto

Bohemond I of Antioch ( 1054 – 5 or 7 March 1111), also known as Bohemond of Taranto or Bohemond of Hauteville, was the prince of Taranto from 1089 to 1111 and the prince of Antioch from 1098 to 1111. He was a leader of the First Crusade, leadi ...

and his nephew Tancred

Tancred or Tankred is a masculine given name of Germanic origin that comes from ''thank-'' (thought) and ''-rath'' (counsel), meaning "well-thought advice". It was used in the High Middle Ages mainly by the Normans (see French Tancrède) and espec ...

. Godfrey of Bouillon

Godfrey of Bouillon (; ; ; ; 1060 – 18 July 1100) was a preeminent leader of the First Crusade, and the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1099 to 1100. Although initially reluctant to take the title of king, he agreed to rule as pri ...

and his brother Baldwin

Baldwin may refer to:

People

* Baldwin (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname

Places Canada

* Baldwin, York Regional Municipality, Ontario

* Baldwin, Ontario, in Sudbury District

* Baldwin's Mills, ...

also joined with forces from Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

, Lotharingia

Lotharingia was a historical region and an early medieval polity that existed during the late Carolingian and early Ottonian era, from the middle of the 9th to the middle of the 10th century. It was established in 855 by the Treaty of Prüm, a ...

, and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. These five princes were pivotal to the campaign, which was augmented by a northern French army led by Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose ( – February 1134, ), the eldest son of William the Conqueror, was Duke of Normandy as Robert II from 1087 to 1106.

Robert was also an unsuccessful pretender to the throne of the Kingdom of England. The epithet "Curthose" ...

, Count Stephen II of Blois

Stephen Henry (in French, ''Étienne Henri'', in Old French, ''Estienne Henri''; – 19 May 1102) was the count of Blois and County of Chartres, Chartres. He led an army during the First Crusade, was at the siege of Nicaea, surrender of the ci ...

, and Count Robert II of Flanders

Robert II, Count of Flanders ( 1065 – 5 October 1111) was Count of Flanders from 1093 to 1111. He became known as Robert of Jerusalem (''Robertus Hierosolimitanus'') or Robert the Crusader after his exploits in the First Crusade.

Early lif ...

. The total number may have reached as many as 100,000 people including non-combatants. They traveled eastward by land to Constantinople where they were cautiously welcomed by the emperor. Alexios persuaded many of the princes to pledge allegiance to him and that their first objective should be Nicaea, the capital of the Sultanate of Rum

The Sultanate of Rum was a culturally Turco-Persian Sunni Muslim state, established over conquered Byzantine territories and peoples (Rum) of Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks following their entry into Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. ...

. Sultan Kilij Arslan Kilij Arslan, meaning ''Sword Lion'' in Turkish, was the name of four sultans of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm:

*Kilij Arslan I reigned as of 1092, died 1107

*Kilij Arslan II reigned as of 1156, died 1192

* Kilij Arslan III reigned as of 1204, died ...

left the city to resolve a territorial dispute, enabling its capture after the siege of Nicaea

The siege of Nicaea was the first major battle of the First Crusade, taking place from 14 May to 19 June 1097. The city was under the control of the Seljuk Turks who opted to surrender to the Byzantines in fear of the crusaders breaking into the ...

and a Byzantine naval assault in the high point of Latin and Greek co-operation.

The first experience of Turkish tactics, using lightly armoured mounted archers, occurred when an advanced party led by Bohemond and Robert was ambushed at the battle of Dorylaeum. The Normans resisted for hours before the arrival of the main army caused a Turkish withdrawal. The army marched for three months to the former Byzantine city Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, that had been in Muslim control since 1084. Starvation, thirst and disease reduced numbers, combined with Baldwin's decision to leave with 100 knights and their followers to carve out his own territory in Edessa. The siege of Antioch

The siege of Antioch took place during the First Crusade in 1097 and 1098, on the crusaders' way to Jerusalem through Syria (region), Syria. Two sieges took place in succession. The first siege, by the crusaders against the city held by the Sel ...

lasted eight months. The crusaders lacked the resources to fully invest the city; the residents lacked the means to repel the invaders. Then Bohemond persuaded a guard in the city to open a gate. The crusaders entered, massacring the Muslim inhabitants and many Christians amongst the Greek Orthodox, Syrian and Armenian communities. A force to recapture the city was raised by Kerbogha

Qiwam al-Dawla Kerbogha (), known as Kerbogha or Karbughā, was the Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman List of rulers of Mosul#Seljuk Atabegs, atabeg of Mosul during the First Crusade and was renowned as a soldier.

Early life

Kerbogha was a Selju ...

, the effective ruler of Mosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

. The Byzantines did not march to the assistance of the crusaders after the deserting Stephen of Blois told them the cause was lost. Alexius retreated from Philomelium, where he received Stephen's report, to Constantinople. The Greeks were never truly forgiven for this perceived betrayal and Stephen was branded a coward. Losing numbers through desertion and starvation in the besieged city, the crusaders attempted to negotiate surrender but were rejected. Bohemond recognised that the only option was open combat and launched a counterattack. Despite superior numbers, Kerbogha's armywhich was divided into factions and surprised by the Crusaders' commitmentretreated and abandoned the siege. Raymond besieged Arqa in February 1099 and sent an embassy to al-Afdal Shahanshah

Al-Afdal Shahanshah (; ; 1066 – 11 December 1121), born Abu al-Qasim Shahanshah bin Badr al-Jamali, was a vizier of the Fatimid caliphs of Egypt. According to a later biographical encyclopedia, he was surnamed al-Malik al-Afdal ("the excellen ...

, the vizier of Fatimid Egypt

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, it ...

, seeking a treaty. The Pope's representative Adhemar died, leaving the crusade without a spiritual leader. Raymond failed to capture Arqa and in May led the remaining army south along the coast. Bohemond retained Antioch and remained, despite his pledge to return it to the Byzantines. Local rulers offered little resistance, opting for peace in return for provisions. The Frankish envoys returned accompanied by Fatimid representatives. This brought the information that the Fatimids had recaptured Jerusalem. The Franks offered to partition conquered territory in return for the city. Refusal of the offer made it imperative that the crusade reach Jerusalem before the Fatimids made it defensible.

The first attack on the city, launched on 7 June 1099, failed, and the siege of Jerusalem became a stalemate, before the arrival of craftsmen and supplies transported by the Genoese to Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

tilted the balance. Two large siege engines were constructed and the one commanded by Godfrey breached the walls on 15 July. For two days the crusaders massacred the inhabitants and pillaged the city. Historians now believe the accounts of the numbers killed have been exaggerated, but this narrative of massacre did much to cement the crusaders' reputation for barbarism. Godfrey secured the Frankish position by defeating an Egyptian force at the Battle of Ascalon

The Battle of Ascalon took place on 12 August 1099 shortly after the capture of Jerusalem, and is often considered the last action of the First Crusade. The crusader army led by Godfrey of Bouillon defeated and drove off a Fatimid army.

The ...

on 12 August. Most of the crusaders considered their pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe. When it came to the future governance of the city it was Godfrey who took leadership and the title of '' Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri,'' Defender of the Holy Sepulchre. The presence of troops from Lorraine ended the possibility that Jerusalem would be an ecclesiastical domain and the claims of Raymond. Godfrey was left with a mere 300 knights and 2,000 infantry. Tancred also remained with the ambition to gain a princedom of his own.

The Islamic world seems to have barely registered the crusade; certainly, there is limited written evidence before 1130. This may be in part due to a reluctance to relate Muslim failure, but it is more likely to be the result of cultural misunderstanding. Al-Afdal Shahanshah and the Muslim world mistook the crusaders for the latest in a long line of Byzantine mercenaries, not religiously motivated warriors intent on conquest and settlement. The Muslim world was divided between the Sunnis of Syria and Iraq and the Shi'ite Fatimids of Egypt. The Turks had found unity unachievable since the death of Sultan Malik-Shah in 1092, with rival rulers in Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

. In addition, in Baghdad, Seljuk sultan Berkyaruq

Rukn al-Din Abu'l-Muzaffar Berkyaruq ibn Malikshah (; 1079/80 – 1105), better known as Berkyaruq (), was the fifth sultan of the Seljuk Empire from 1094 to 1105.

The son and successor of Malik-Shah I (), he reigned during the opening stages of ...

and Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir

Abu'l-Abbas Ahmad ibn Abdallah al-Muqtadi () usually known simply by his regnal name Al-Mustazhir billah () (b. April/May 1078 – 6 August 1118 d.) was the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad from 1094 to 1118. He succeeded his father al-Muqtadi as the C ...

were engaged in a power struggle. This gave the Crusaders a crucial opportunity to consolidate without any pan-Islamic counter-attack.

Early 12th century

Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II (; 1050 1055 – 21 January 1118), born Raniero Raineri di Bleda, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 August 1099 to his death in 1118. A monk of the Abbey of Cluny, he was creat ...

who continued the policies of his predecessors in regard to the Holy Land. Godfrey died in 1100. Dagobert of Pisa

Dagobert (or Daibert or Daimbert) (died 1105) was the first Archbishop of Pisa and the second Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem after the city was captured in the First Crusade.

Early life

Little is known of Dagobert's early life, but he is thought t ...

, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem

The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem () is the Latin Catholic ecclesiastical patriarchate in Jerusalem, officially seated in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem is the archbishop of Latin Church Catholics of th ...

and Tancred looked to Bohemond to come south, but he was captured by the Danishmends

The Danishmendids or Danishmends () were a Turkish dynasty. These terms also refer to the Turkish Anatolian Beyliks, state in Anatolia. It existed from 1071/1075 to 1178 and is also known as the Danishmendid Beylik (). The dynasty was centered or ...

. The Lorrainers foiled the attempt to seize power and enabled Godfrey's brother, Baldwin I, to take the crown.

Paschal II promoted the large-scale Crusade of 1101

The Crusade of 1101, also known as the Crusade of the Faint-Hearted, was launched in the aftermath of the First Crusade with calls for reinforcements from the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem and to rescue the famous Bohemond of Taranto fr ...

in support of the remaining Franks. This new crusade was a similar size to the First Crusade and joined in Byzantium by Raymond of Saint-Gilles

Raymond of Saint-Gilles ( 1041 – 28 February 1105), also called Raymond IV of Toulouse or Raymond I of Tripoli, was the count of Toulouse, duke of Narbonne, and margrave of Provence from 1094, and one of the leaders of the First Crusade from 10 ...

. Command was fragmented and the force split in three:

* A largely Lombard force was harried by Kilij Arslan's forces and finally destroyed in three days at the battle of Mersivan in August 1101. Some of the leadership, including Raymond, Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 un ...

and Anselm IV of Milan, survived to retreat to Constantinople.

* A force led by William II of Nevers

William II, Count of Nevers (French: ''Guillaume II'', born prior to 1089, reigned 1098 – 21 August 1148), was a crusader in the Crusade of 1101.

Family

He was a son of Renauld II, Count of Nevers and his second wife Agnes of Beaugency.Consta ...

attempted catch up with the Lombards but was caught and routed at Heraclea. The destitute leaders eventually reached Antioch.

* William IX of Aquitaine

William IX ( or , ; 22 October 1071 – 10 February 1126), called the Troubadour, was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and Count of Poitou (as William VII) between 1086 and his death. He was also one of the leaders of the Crusade of 1101.

Thoug ...

, Welf IV of Bavaria, Ida of Formbach-Ratelnberg

Ida of Austria ( 1055 – September 1101) was a Margravine of Austria by marriage to Leopold II of Austria. She was a crusader, participating in the Crusade of 1101 with her own army.Steven Runciman: ''Geschichte der Kreuzzüge'' ('A History of ...

and Hugh, Count of Vermandois

Hugh (1057 – October 18, 1101), called the Great (, ) was the first count of Vermandois from the House of Capet. He is known primarily for being one of the leaders of the First Crusade. His nickname ''Magnus'' (greater or elder) is probably a ...

reached Heraclea later and were also defeated. Again the leaders fled the field and survived, although Hugh died of his wounds at Tarsus and Ida disappeared. The remnants of the army helped Raymond capture Tortosa

Tortosa (, ) is the capital of the '' comarca'' of Baix Ebre, in Catalonia, Spain.

Tortosa is located at above sea level, by the Ebro river, protected on its northern side by the mountains of the Cardó Massif, of which Buinaca, one of the hi ...

.

The defeat of the crusaders proved to the Muslim world that the crusaders were not invincible, as they appeared to be during the First Crusade. Within months of the defeat, the Franks and Fatimid Egypt began fighting in three battles at Ramla, and one at Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

:

* In the first

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

on 7 September 1101, Baldwin I and 300 knights narrowly defeated the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah.

* In the second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

on 17 May 1102, al-Afdal's son Sharaf al-Ma'ali and a superior force inflicted a major defeat on the Franks. Stephen of Blois and Stephen of Burgundy from the Crusade of 1101 were among those killed. Baldwin I fled to Arsuf.

* Victory at the battle of Jaffa on 27 May 1102 saved the kingdom from virtual collapse.

* In the third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', i.e., the third in a series of fractional parts in a sexagesimal number system

Places

* 3rd Street (di ...

at Ramla on 28 August 1102, a coalition of Fatimid and Damescene forces were defeated again by Baldwin I and 500 knights.

Baldwin of Edessa, later king of Jerusalem as Baldwin II, and Patriarch Bernard of Valence Bernard of Valence (died 1135) was the Latin Patriarch of Antioch from 1100 to 1135.

Originally from Valence, Bernard was part of the army of Raymond of Saint-Gilles and attended the Battle of Harran and Battle of Ager Sanguinis with Roger of Sa ...

ransomed Bohemond for 100,000 gold pieces. Baldwin and Bohemond then jointly campaigned to secure Edessa's southern front. On 7 May 1104, the Frankish army was defeated by the Seljuk rulers of Mosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

and Mardin

Mardin (; ; romanized: ''Mārdīn''; ; ) is a city and seat of the Artuklu District of Mardin Province in Turkey. It is known for the Artuqids, Artuqid architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on a rocky hill near the Tigris ...

at the battle of Harran

The Battle of Harran took place on 7 May 1104 between the Crusader states of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Edessa, and the Seljuk Turks. It was the first major battle against the newfound Crusader states in the aftermath of the F ...

. Baldwin II and his cousin, Joscelin of Courtenay, were captured. Bohemond and Tancred retreated to Edessa where Tancred assumed command. Bohemond returned to Italy, taking with him much of Antioch's wealth and manpower. Tancred revitalised the beleaguered principality with victory at the battle of Artah

The Battle of Artah was fought in 1105 between Crusader forces and the Seljuk Turks at the town of Artah near Antioch. The Turks were led by Fakhr al-Mulk Ridwan of Aleppo, while the Crusaders were led by Tancred, Prince of Galilee, regent of ...

on 20 April 1105 over a larger force, led by the Seljuk Ridwan of Aleppo

Ridwan ( – 10 December 1113) was a Seljuk emir of Aleppo from 1095 until his death.

Ridwan was born to the Seljuk prince Tutush, who had established a principality in Syria after his brother, Sultan Malik-Shah I granted him the region ...

. He was then able to secure Antioch's borders and push back his Greek and Muslim enemies. Under Paschal's sponsorship, Bohemond launched a version of a crusade in 1107 against the Byzantines, crossing the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

and besieging Durrës. The siege failed; Alexius hit his supply lines, forcing his surrender. The terms laid out in the Treaty of Devol

The Treaty of Deabolis () was an agreement made in 1108 between Bohemond I of Antioch and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, in the wake of the First Crusade. It is named after the Byzantine fortress of Deabolis (modern Devol, Albania). Alth ...

were never enacted because Bohemond remained in Apulia and died in 1111, leaving Tancred as notional regent for his son Bohemond II. In 1007, the people of Tell Bashir

Tell may refer to:

*Tell (archaeology), a type of archaeological site

*Tell (name), a name used as a given name and a surname

*Tell (poker), a subconscious behavior that can betray information to an observant opponent

Arts, entertainment, and m ...

ransomed Joscelin and he negotiated Baldwin's release from Jawali Saqawa

Jawali Saqawa (d. 1109), also known as Chavli Saqaveh, was a Turkoman adventurer who was atabeg of Mosul from 1106–1109. In 1104, Jawali held Baldwin II as prisoner until he was ransomed in 1108. He had purloined Baldwin from Jikirmish of Mo ...

, atabeg of Mosul, in return for money, hostages and military support. Tancred and Baldwin, supported by their respective Muslim allies, entered violent conflict over the return of Edessa leaving 2,000 Franks dead before Bernard of Valence, patriarch of both Antioch and Edessa, adjudicated in Baldwin's favour.

On 13 May 1110, Baldwin II and a Genoese fleet captured Beirut. In the same month, Muhammad I Tapar

Muhammad I Tapar (, ; 20 January 1082 – 18 April 1118), was the sultan of the Seljuk Empire from 1105 to 1118. He was a son of Malik-Shah I () and Taj al-Din Khatun Safariya.

Reign

Muhammad was born in 20 January 1082. He succeeded his nephew, ...

, sultan of the Seljuk Empire, sent an army to recover Syria, but a Frankish defensive force arrived at Edessa, ending the short siege of the city. On 4 December, Baldwin captured Sidon, aided by a flotilla of Norwegian pilgrims led by Sigurd the Crusader

Sigurd the Crusader (; ; 1089 – 26 March 1130), also known as Sigurd Magnusson and Sigurd I, was King of Norway from 1103 to 1130. His rule, together with his half-brother Øystein (until Øystein died in 1123), has been regarded by historian ...

. Next year, Tancred's extortion from Antioch's Muslim neighbours provoked the inconclusive battle of Shaizar

In the Battle of Shaizar in 1111, a Crusader army commanded by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem and a Seljuk army led by Mawdud ibn Altuntash of Mosul fought to a tactical draw, but a withdrawal of Crusader forces.

Background

Beginning in 1110 ...

between the Franks and an Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

army led by the governor of Mosul, Mawdud

Mawdud ibn Ahmad (; died 2 October 1113) was a Muslim military leader who was atabeg of Mosul from 1109 to 1113. He organized several expeditions to reconquer lands from the Crusaders and defeated them at the Battle of al-Sannabra.

Biography

Ma ...

. Tancred died in 1112 and power passed to his nephew Roger of Salerno

Roger of Salerno (or Roger of the Principate) ( 1080 – June 28, 1119) was regent of the Principality of Antioch from 1112 to 1119.

He was the son of Richard of the Principate and the 2nd cousin of Tancred, Prince of Galilee, both participants o ...

. In May 1113, Mawdud invaded Galilee with Toghtekin

Zahir al-Din Toghtekin or Tughtekin (Modern ; Arabicised epithet: ''Zahir ad-Din Tughtikin''; died February 12, 1128), also spelled Tughtegin, was a Turkoman military leader, who was ''emir'' of Damascus from 1104 to 1128. He was the founder ...

, atabeg of Damascus. On 28 June this force surprised Baldwin, chasing the Franks from the field at the battle of al-Sannabra

In the Battle of al-Sannabra (1113), a Crusader army led by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem was defeated by a Muslim army sent by the Sultan of the Seljuk Turks and commanded by Mawdud ibn Altuntash of Mosul.

Background

Beginning in 1110, the Se ...

. Mawdud was killed by Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

The origin of the term is the medieval Order of Assassins, a sect of Shia Islam 1090–1275 CE.

Assassin, or variants, may also refer to:

Fictional characters

* Assassin, in the Japanese adult ...

. Bursuq ibn Bursuq

Bursuq ibn Bursuq, also known as Bursuk ibn Bursuk (died in 1116 or 1117), was the emir (or lord) of Hamadan.

General

He was the most notable son of Bursuq the Elder. Bursuq ibn Bursuq was a Turkic general in the service of the Seljuq Sultan ...

led the Seljuk army in 1115 against an alliance of the Franks, Toghtekin, his son-in-law Ilghazi

Najm al-Din Ilghazi ibn Artuq (; died November 8, 1122) was the Turkoman Artukid ruler of Mardin from 1107 to 1122. He was born into the Oghuz tribe of Döğer.

Biography

His father Artuk Bey was the founder of the Artukid dynasty, and had ...

and the Muslims of Aleppo. Bursuq feigned retreat and the coalition disbanded. Only the forces of Roger and Baldwin of Edessa remained, but, heavily outnumbered, they were victorious on 14 September at the first battle of Tell Danith.

In April 1118, Baldwin I died of illness while raiding in Egypt. His cousin, Baldwin of Edessa, was unanimously elected his successor. In June 1119, Ilghazi, now

In April 1118, Baldwin I died of illness while raiding in Egypt. His cousin, Baldwin of Edessa, was unanimously elected his successor. In June 1119, Ilghazi, now emir of Aleppo

The monarchs of Aleppo reigned as kings, emirs and sultans of the city and its surrounding region since the later half of the 3rd millennium BC, starting with the kings of Armi, followed by the Amorite dynasty of Yamhad. Muslim rule of the city ...

, attacked Antioch with more than 10,000 men. Roger of Salerno

Roger of Salerno (or Roger of the Principate) ( 1080 – June 28, 1119) was regent of the Principality of Antioch from 1112 to 1119.

He was the son of Richard of the Principate and the 2nd cousin of Tancred, Prince of Galilee, both participants o ...

's army of 700 knights, 3,000 foot soldiers and a corps of Turcopole

During the period of the Crusades, turcopoles (also "turcoples" or "turcopoli"; from the , literally "sons of Turks") were locally recruited mounted archers and light cavalry employed by the Byzantine Empire and the Crusader states. A leader of t ...

s was defeated at the battle of Ager Sanguinis

In the Battle of ''Ager Sanguinis'', also known as the Battle of the Field of Blood, the Battle of Sarmada, or the Battle of Balat, Roger of Salerno's Crusader army of the Principality of Antioch was annihilated by the army of Ilghazi of Mard ...

, or "field of blood". Roger was among the many killed. Baldwin II's counter-attack forced the offensive's end, after an inconclusive second battle of Tell Danith.

In January 1120 the secular and ecclesiastical leaders of the Outremer gathered at the Council of Nablus

The Council of Nablus was a council of ecclesiastic and secular lords in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, held on January 16, 1120.

History

The council was convened at Nablus by Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and King Baldwin II of Jerusalem. ...

. The council laid a foundation of a law code for the kingdom of Jerusalem that replaced common law. The council also heard the first direct appeals for support made to the Papacy and Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

. They responded with the Venetian Crusade

The Venetian Crusade of 1122–1124 was an expedition to the Holy Land launched by the Republic of Venice that succeeded in capturing Tyre.

It was an important victory at the start of a period when the Kingdom of Jerusalem would expand to it ...

, sending a large fleet that supported the capture of Tyre in 1124. In April 1123, Baldwin II was ambushed and captured by Belek Ghazi

Belek Ghazi (''Nuruddevle Belek'' or ''Balak'') was a Turkish bey in the early 12th century.

Early life

His father was Behram and his grandfather was Artuk Bey, an important figure of the Seljuk Empire in the 11th century. He was a short-term ...

while campaigning north of Edessa, along with Joscelin I, Count of Edessa

Joscelin I (died 1131) was a Frankish nobleman of the House of Courtenay who ruled as the lord of Turbessel, prince of Galilee (1112–1119) and count of Edessa (1118–1131). The County of Edessa reached its zenith during his rule. Captured ...

. He was released in August 1024 in return for 80,000 gold pieces and the city of Azaz

Azaz () is a city in northwest Syria, roughly north-northwest of Aleppo. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Azaz had a population of 31,623 at the 2004 census.

. In 1129, the Council of Troyes

There have been a number of synods held at Troyes:

Council of 867

The council was held on orders of Pope Nicholas I, to deal with Hincmar of Reims and his quarrels. The decrees were signed on 2 November 867. The Council ruled that no bishop coul ...

approved the rule of the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

for Hugues de Payens

, commonly known in French as or ( – 24 May 1136), was the co-founder and first Grand Master of the Knights Templar.

Origin and early life

The Latin text of William of Tyre's ''History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea'', dated , calls him , ...

. He returned to the East with a major force including Fulk V of Anjou

Fulk of Anjou (, or ''Foulques''; – 13 November 1143), also known as Fulk the Younger, was the king of Jerusalem from 1131 until 1143 as the husband and co-ruler of Queen Melisende. Previously, he was the count of Anjou as Fulk V from 1109 t ...

. This allowed the Franks to capture the town of Banias

Banias (; ; Judeo-Aramaic, Medieval Hebrew: , etc.; ), also spelled Banyas, is a site in the Golan Heights near a natural spring, once associated with the Greek god Pan. It had been inhabited for 2,000 years, until its Syrian population fle ...

during the Crusade of 1129

The Crusade of 1129 or the Damascus Crusade was a military campaign of the Kingdom of Jerusalem with forces from the other crusader states and from western Europe against the Emirate of Damascus. The brainchild of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, t ...

. Defeat at Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Marj al-Saffar

Marj al-Saffar or Marj al-Suffar ( ') is a large plain to the south of Damascus. Marj al-Saffar is bounded to the north by the right bank of the al-A'waj river, which flows from Mount Hermon to the Sabkhat al-Hijana. In the south the plain is bound ...

ended the campaign and Frankish influence on Damascus for years.

The Levantine Franks sought alliances with the Latin West through the marriage of heiresses to wealthy martial aristocrats. Constance of Antioch

Constance of Hauteville (c. 1128–1163) was the ruling Prince of Antioch, princess of Antioch from 1130 to 1163. She was the only child of Bohemond II of Antioch and Alice of Antioch, Alice of Jerusalem. Constance succeeded her father at the age ...

was married to Raymond of Poitiers

Raymond of Poitiers (c. 1105 – 29 June 1149) was Prince of Antioch from 1136 to 1149. He was the younger son of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, and his wife Philippa, Countess of Toulouse, born in the very year that his father the Duke began hi ...

, son of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine

William IX ( or , ; 22 October 1071 – 10 February 1126), called the Troubadour, was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and Count of Poitou (as William VII) between 1086 and his death. He was also one of the leaders of the Crusade of 1101.

Thoug ...

. Baldwin II's eldest daughter Melisende of Jerusalem

Melisende ( 1105 – 11 September 1161) was the queen of Jerusalem from 1131 to 1152. She was the first female ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the first woman to hold a public office in the crusader kingdom. She was already legendary in he ...

was married to Fulk of Anjou in 1129. When Baldwin II died on 21 August 1131, Fulk and Melisende were consecrated joint rulers of Jerusalem. Despite conflict caused by the new king appointing his own supporters and the Jerusalemite nobles attempting to curb his rule, the couple were reconciled and Melisende exercised significant influence. When Fulk died in 1143, she became joint ruler with their son, Baldwin III of Jerusalem

Baldwin III (1130 – 10 February 1163) was the king of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Queen Melisende and King Fulk. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he eventu ...

. At the same time, the advent of Imad ad-Din Zengi

Imad al-Din Zengi (; – 14 September 1146), also romanized as Zangi, Zengui, Zenki, and Zanki, was a Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman atabeg of the Seljuk Empire, who ruled Emir of Mosul, Mosul, Emirate of Aleppo, Aleppo, Hama, and, later, Ede ...

saw the Crusaders threatened by a Muslim ruler who would introduce ''jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

'' to the conflict, joining the powerful Syrian emirates in a combined effort against the Franks. He became atabeg of Mosul in September 1127 and used this to expand his control to Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

in June 1128. In 1135, Zengi moved against Antioch and, when the Crusaders failed to put an army into the field to oppose him, he captured several important Syrian towns. He defeated Fulk at the battle of Ba'rin

In the Battle of Ba'rin (also known as Battle of Montferrand) in 1137, a Crusader force commanded by King Fulk of Jerusalem was scattered and defeated by Zengi, the Atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo. This setback resulted in the permanent loss of the ...

of 1137, seizing Ba'rin Castle.

In 1137, Zengi invaded Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis (from , meaning "three cities") may refer to:

Places Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in the Pelasgiotis district, Thessaly, near Larissa ...

, killing the count Pons of Tripoli

Pons ( 1098 – 25 March 1137) was count of Tripoli from 1112 to 1137. He was a minor when his father, Bertrand, died in 1112. He swore fealty to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in the presence of a Byzantine embassy. His advisors sent ...

. Fulk intervened, but Zengi's troops captured Pons' successor Raymond II of Tripoli

Raymond II (; 1116 – 1152) was count of Tripoli from 1137 to 1152. He succeeded his father, Pons, who was killed during a campaign that a commander from Damascus launched against Tripoli. Raymond accused the local Christians of betraying his ...

, and besieged Fulk in the border castle of Montferrand. Fulk surrendered the castle and paid Zengi a ransom for his and Raymond's freedom. John II Komnenos

John II Komnenos or Comnenus (; 13 September 1087 – 8 April 1143) was List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as "John the Beautiful" or "John the Good" (), he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexio ...

, emperor since 1118, reasserted Byzantine claims to Cilicia and Antioch, compelling Raymond of Poitiers