Rallying is a wide-ranging form of

motorsport

Motorsport or motor sport are sporting events, competitions and related activities that primarily involve the use of Car, automobiles, motorcycles, motorboats and Aircraft, powered aircraft. For each of these vehicle types, the more specific term ...

with various competitive motoring elements such as speed tests (sometimes called "rally racing" in United States), navigation tests, or the ability to reach waypoints or a destination at a prescribed time or average speed. Rallies may be short in the form of trials at a single venue, or several thousand miles long in an extreme endurance rally.

Depending on the format, rallies may be organised on private or public roads, open or closed to traffic, or off-road in the form of cross country or rally-raid. Competitors can use

production

Production may refer to:

Economics and business

* Production (economics)

* Production, the act of manufacturing goods

* Production, in the outline of industrial organization, the act of making products (goods and services)

* Production as a stat ...

vehicles which must be

road-legal if being used on open roads or specially built competition vehicles suited to crossing specific terrain.

In most cases rallying distinguishes itself from other forms of motorsport by not running directly against other competitors over laps of a

circuit, but instead in a point-to-point format in which participants leave at regular intervals from one or more start points.

Rally types

Rallies generally fall under two categories, road rallies and cross-country (off-road). Different types of rally are described however a rally may be a mix of types.

Road rallies

Road rallies are the original form held on public highways open to traffic. In its annually published

International Sporting Code The International Sporting Code (ISC) is a set of rules applicable to all four-wheel motorsport as governed by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). It was first implemented in 1926.

The ISC consists of 20 articles and several Adde ...

, the

Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile

The Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA; ) is an international organisation with two primary functions surrounding use of the automobile. Its mobility division advocacy, advocates the interests of motoring organisations, the automot ...

(FIA) includes the following definition of rally:

Regularity rally

In an exclusively regularity rally, the aim is to adhere to the itinerary by following the route and arriving and departing at checkpoints at the prescribed time, with penalties applied to entrants who arrive early, late or who deviate from the route. The entrants with the fewest penalties at the end of the rally are the winners. In trying to maintain the set average speed/s, the reliability of the vehicle, and the ability of the crew to drive, navigate and follow the itinerary is tested. Most non-regularity rally itineraries follow this base structure even where driving tests or special stages are used, however these would not then be described as a regularity rally.

Time-Speed-Distance (TSD rally)

Similar to a regularity rally, the itinerary may advise a time and/or distance, or may only advise a target average speed with no indication where the checkpoints may be.

Navigational rally

The ability of the crew to follow road signs or directions of varying depth of information is tested.

Gimmick rallies

Gimmick rallies have less of a concern on timekeeping or driving ability and include other fun and games. Examples include:

* Monte-Carlo styles (Monte Carlo, Pan Am, Pan Carlo, Continental)

* logic

* observation

* treasure hunts

These rallies are primarily amateur events.

File:Porsche Speedster Sachs Franken Classic 2018 5201320.jpg, alt=, Porsche Speedster in a regularity rally for historic vehicles, no additional safety equipment such as a roll cage or helmets are needed

File:Ford WRC sur circulation public.JPG, alt=, Ford Focus

The Ford Focus is a compact car (C-segment in Europe) manufactured by Ford Motor Company from 1998 until 2025. It was created under Alexander Trotman's Ford 2000 plan, which aimed to globalize model development and sell one compact vehicle worl ...

on a road section of a WRC rally

File:Rallye des Princesses 2014 Châteaudun.jpg, alt=, Road rally passing through an urban setting

File:Lancia Fulvia 1.6 Coupé HF - 1972 Press-on-Regardless Rally.jpg, alt=, Crew repairing a Lancia Fulvia on an urban street of the 1972 Press on Regardless Rally

File:Ttarga Tasmania 2010 Car 626 Start.jpg, alt=, Start of a targa road rally

Stage rallying simply divides the route from the start to the finish of any rally into stages, not necessarily exclusively for speed tests on ''special stages''. Each stage may have different targets or rules attached. In the FIA ecoRally Cup for example, energy performance is measured on regularity stages ran in conformity with the clock. A gimmick rally may have stages with varying difficulty of the puzzle element.

Speed competitions

Road rallies must use

special stages where speed is used to determine the classification of the rally's competitors; the quickest time to complete the special stages wins the rally. These are sections of road closed to traffic and authorised to be used for speed tests. Special stages are linked by open roads where navigation, timekeeping, and road traffic law rules must be followed. These open road sections are sometimes called transport stages, somewhat complementing special stages in the make-up of a stage rally. These are the most common format of professional and commercial rallies and rally championships. The FIA organises the

World Rally Championship

The World Rally Championship (abbreviated as WRC) is an international rallying series owned and governed by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile, FIA. Inaugurated in 1973, it is the oldest FIA world championship after Formula One. E ...

, Regional Rally Championships; and many countries' motorsport governing bodies organise domestic rallying championships using speed competitions. The stages may vary from flat asphalt and mountain passes to rough forest tracks, from ice and snow to desert sand, each chosen to provide a challenge for the crew and a test of the car's performance and reliability. A single-venue rally takes place without the need for public road sections though the format and rules remain.

In the wake of the ever more advanced rally cars of the late 20th and 21st century is a trend towards historic rallying (also known as

classic rally Classic rallying, or historic rallying, is a type of road rally suitable for most standard classic cars, with no special equipment needed (the equipment allowed depends on the particular rally). These rallies are more about enjoyment than speed, a ...

ing), in which older cars can continue to rally. Historic rallies are usually regularity rallies with no speed tests arranged. This discipline attracts some former professional drivers back into the sport. Other drivers started their competition careers in historic rallying.

File:2018 Rally de Portugal - Hyundai i20 Coupe WRC.jpg, alt=, Hyundai i20 Coupe contests a special stage of a WRC rally

File:PROKOP - TOMANEK en SS14 La Figuera 2 - panoramio.jpg, alt=, Closed asphalt public highway used as a special stage

File:2010 1000 Lakes Rally Harju 14.JPG, alt=, Urban 'street stage'

File:Forest road junction in Craigvinean Forest - geograph.org.uk - 500942.jpg, alt=, Ford Escort on a historic rally's special stage

File:The Snowman Rally 2010 - geograph.org.uk - 1732909.jpg, alt=, Snowy rally special stage

Cross-country rallies

Also commonly known by its types

rally-raid or

baja; cross-country rallies take place mostly off-road using similar competitive elements to road and special stage rallying competitions. When off-road, waypoints and markers are set using GPS systems, although competitors cannot use GPS for navigation. Crews must choose how best to cross the terrain to the next waypoint whilst respecting the navigational instructions provided in the roadbook. The challenge is mostly navigational and endurance. The

World Rally-Raid Championship was inaugurated in 2022, including the annual

Dakar Rally

The Dakar Rally () or simply "The Dakar" (), formerly known as the Paris–Dakar Rally (), is an annual rally raid organised by the Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO). It is an off-road endurance event traversing terrain much tougher than convent ...

in its calendar, with joint sanctioning by the FIA and

FIM

FIM may refer to:

Organizations and companies

* Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme, the International Motorcycling Federation

* Flint Institute of Music, in Michigan, United States

* Fox Interactive Media, now News Corp. Digital Media

* ...

.

Hill Rally

Hill rallies are a type of cross-country event found in the United Kingdom and defined and governed by

Motorsport UK

Motorsport UK (MSUK), formerly known as the Motor Sports Association (MSA), is a national membership organisation and governing body for four-wheel motorsport in the United Kingdom. Legally, it is a not-for-profit private company limited by guar ...

.

Touring assembly

Assemblies of car enthusiasts and their vehicles may still colloquially be called rallies, even if they involve merely the task of getting to the location (often on a trailer). However, static assemblies that simply 'meet' (akin to a caravan or

steam rally

A steam fair or (steam rally) is a regular organised gathering of historic steam-powered vehicles and machinery, open to the public. Typical exhibits include: traction engines, steam rollers, steam wagons, and steam cars. Often, the scope is wide ...

) are not considered a form of motorsport. A touring assembly may have an organised route and simple passage controls but not any form of competition held or prizes given. One example, the

Gumball 3000

Gumball 3000 is a brand known for the annual Gumball 3000 Rally, an international celebrity motor rally that takes place on public roads. The brand was founded in 1999 by English entrepreneur Maximillion Cooper, with his vision to combine cars, ...

, which calls itself a rally not a race''

', explicitly states in its terms that no form of competition between participants must take place. The FIA defined this activity under 'rally of the touring kind' at least until 2007, though have now separated the term 'Touring Assembly' without using the word rally in its definition.

Rally derivatives and relatives

Trials

*

Hillclimbing

Hillclimbing, also known as hill climbing, speed hillclimbing, or speed hill climbing, is a branch of motorsport in which drivers compete against the clock to complete an uphill course. It is one of the oldest forms of motorsport, since the firs ...

: Though not a form of rally, hillclimbing could be described in related terms as one special stage that climbs a hill. Cars start at intervals from one start point to one finish point. This discipline allows for many types of vehicles including single-seaters and can be arranged at one venue.

*

Autocross

Autocross is a form of motorsport in which competitors are timed to complete a short course using automobiles on a dirt or grass surface, excepting where sealed surfaces are used in United States. Rules vary according to the governing or sanctioni ...

: Similar to hillclimbing, cars also start at intervals and are timed to complete a course, usually temporary and marked out with cones with the intent of demanding good car handling rather than speed. Cars can be single-seaters with roll cages used in

crosskart racing.

* Rallysprint: Very condensed form of trials-type driving with no particular global definition. Usually run with

touring cars

Touring car racing is a motorsport road racing competition that uses race-prepared touring cars. It has both similarities to and significant differences from stock car racing, which is popular in the United States.

While the cars do not move a ...

at single venues or a single stage without road sections, co-drivers or itineraries, and competitors may even switch cars depending on the agreed rules of competition.

*

Gymkhana

Gymkhana () (, , , , ) is a British Raj term which originally referred to a place of assembly. The meaning then altered to denote a place where skill-based contests were held. "Gymkhana" is an Anglo-Indian expression, which is derived from the ...

/Autoslalom: Similar to autocross but with very precise and extravagant handling requirements such as

donuts

A doughnut or donut () is a type of pastry made from leavened fried dough. It is popular in many countries and is prepared in various forms as a sweet snack that can be homemade or purchased in bakeries, supermarkets, food stalls, and franch ...

and

drifting.

Racing

*

Rallycross

Rallycross is a form of sprint style motorsport held on a mixed-surface circuit (racing), racing circuit using modified production touring automobile, cars or prototype racing cars. It began in the 1960s as a cross between rallying and autocross ...

: Created for a British TV programme in 1967 where rally drivers were allowed to directly compete in groups of four in short sprint races on a circuit. Rallycross has grown to have FIA World and European Championships with specifically developed cars that out-power standard rally cars.

* Formula Rally: Originating as part of the ''Bologna Motor Show'' in Italy, in December 1985, was a show race of rally drivers in an arena occupied by around 50,000 spectators, a "Mickey Mouse Course" had been created, on which two players (starting from different starting places) competed for the overall victory in the final through a ''knock-out system'' over preliminary rounds, quarter-finals and semi-finals. Formula Rally is practiced mostly in Italy and Germany.

*

Ice Racing: The ''ice races'' of the ''

Andros Trophy'', run in France, have their roots in rallying. As early as the 1970s, car ice races were contested in the French Maritime Alps in the winter sports centres of Chamonix ''(24h sur Glace de Chamonix)'' and Serre Chevalier with rally cars that were still relatively tame at the time. Later, the participants developed far more efficient vehicles for this purpose; for the ''Andros trophy'' almost exclusively very potent prototypes with all-wheel drive and synchronous steering of the front and rear wheels.

*

Enduro

Enduro is a form of motorcycle sport run on extended cross-country, off-road courses. Enduro consists of many different obstacles and challenges. The main type of enduro event, and the format to which the World Enduro Championship is run, is ...

: A similar, but not identical sporting form to rally for motorcycles.

History

Etymology

The word '

''rally'

'' comes from the French verb rallier''

', meaning to reunite or regroup urgently during a battle. It was in use since at least the seventeenth century and continues to mean to synergise with haste for a purpose. By the time of the invention of the motor car, it was in use as a noun to define the organised mass gathering of people, not to protest or demonstrate, but to promote or celebrate a social, political or religious cause. Motor car rallies were probably being arranged as motor clubs and

automobile associations

An automobile association, also referred to as a motoring club, motoring association, or motor club, is an organization, either for-profit or non-profit, which motorists (drivers and vehicle owners) can join to enjoy benefits provided by the club ...

were beginning to form shortly after the first motor cars were being produced.

"Auto Rallies" were common events in the USA in the early twentieth century for the purpose of political

caucusing, however many of these rallies were coincidentally aimed at motorists who could attend in convenient fashion rather than being a motoring rally. One early example of a true motor rally, the 1909 Auto Rally Day in

Denison, Iowa

Denison is a city in Crawford County, Iowa, United States, along the Boyer River, and located in both Denison Township and East Boyer Township. The population was 8,373 at the time of the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Crawford Count ...

, United States, gathered approximately 100 vehicles owned by local residents for no other real reason than to give rides to members of the public, using fuel paid for by local businessmen who hoped the event would help sell cars.

In the case of the 1910 Good Roads Rally held in

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, a rally was organised to promote the need for better roads. The rally itself had no competition and most vehicles were expected to be parked for its duration. The programme included a visit to some ongoing roadworks, a vehicle parade, with food, drink, dancing and music also arranged. However, the Automobile Club of

Columbia, who had members attending the event, independently organised their own road competition to contest on the journey between the two cities. A prize of $10 was awarded to the motorist "approximating the most ideal schedule" between two secret points along the route and who had "the most nearly correct idea of a pleasant and sensible pleasure tour" between the two cities. Though this format of competition itself would later become known as a regularity 'rally', it wasn't at the time, however the trophy and prize were awarded at the rally.

The first known use of the word rally to include a road competition was the 1911 Monaco Rally (later

Monte Carlo Rally

The Monte Carlo Rally or Rallye Monte-Carlo (officially Rallye Automobile Monte-Carlo) is a rallying event organized each year by the Automobile Club de Monaco. From its inception in 1911 by Albert I, Prince of Monaco, Prince Albert I, the rally ...

). It was organised by a group of wealthy locals who formed the "Sport Automobile Vélocipédique Monégasque" and bankrolled by the "Société des Bains de Mer" (the "sea bathing company"), the operators of the famous casino who were keen to attract wealthy and adventurous motorists to their 'rallying point'. Competitors could start at various locations but with a speed limit of 25kph imposed, the competitive elements were partly based on cleanliness, condition and elegance of the cars and required a jury to choose a winner. However, getting to Monaco in winter was a challenge in itself. A second event was held in 1912.

Rallying as road competitions

Origins of motorsport

Rallying as a form of road competition can be traced back to the origins of motorsport, including the world's first known motor race; the 1894

Paris–Rouen Horseless Carriage Competition (''Concours des Voitures sans Chevaux''). Sponsored by a Paris newspaper, ''

Le Petit Journal'', it attracted considerable public interest and entries from leading manufacturers. The official winner was

Albert Lemaître

Albert Lemaître (5 February 1864 – 27 July 1912), (aka Georges LemaîtreSome modern anglophone secondary sources (and myriad derivative internet sites) use the name Georges Lemaître, but the leading contemporary French sources of the 1890s– ...

driving a 3 hp

Peugeot

Peugeot (, , ) is a French automobile brand owned by Stellantis.

The family business that preceded the current Peugeot companies was established in 1810, making it the oldest car company in the world. On 20 November 1858, Émile Peugeot applie ...

, although the

''Comte'' de Dion had finished first but his steam-powered vehicle was ineligible for the official competition.

The event led to a period of city-to-city road races being organised in Europe and the USA, which introduced many of the features found in later rallies: individual start times with cars running against the clock rather than head to head; time controls at the entry and exit points of towns along the way; road books and route notes; and driving over long distances on ordinary, mainly gravel, roads, facing hazards such as dust, traffic, pedestrians and farm animals.

[Grand Prix History online](_blank)

(retrieved 11 June 2017)

From 24 September-3 October 1895, the ''

Automobile Club de France

The Automobile Club of France () (ACF) is a men's club founded on 12 November 1895 by Albert de Dion, , and its first president, the Dutch-born Baron Étienne van Zuylen van Nyevelt.

The Automobile Club of France, also known in French as "ACF" o ...

'' sponsored the longest race to date, a event from

Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

to

Agen

Agen (, , ) is the prefecture of the Lot-et-Garonne department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Southwestern France. It lies on the river Garonne, southeast of Bordeaux. In 2021, the commune had a population of 32,485.

Geography

The city of Agen l ...

and back. Because it was held in ten stages, it can be considered the first stage rally. The first three places were taken by a Panhard, a Panhard, and a three-wheeler

De Dion-Bouton

De Dion-Bouton was a French automobile manufacturer and railcar manufacturer, which operated from 1883 to 1953. The company was founded by the Marquis Jules-Albert de Dion, Georges Bouton, and Bouton's brother-in-law Charles Trépardoux.

Ste ...

.

In the

Paris–Madrid race :''See also the 1911 Paris to Madrid air race.''

The Paris–Madrid race of May 1903 was an early experiment in auto racing, organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF) and the Spanish Automobile Club, Automóvil Club Español.

At the time ...

of May 1903, the

Mors of

Fernand Gabriel took just under five and a quarter hours for the to Bordeaux, an average of 105 km/h (65.3 mph). Speeds had now exceeded the safe limits of dusty highways thronged with spectators and open to other traffic, people and animals and there were numerous crashes, many injuries and eight deaths. The French government stopped the race and banned this style of event. From then on, racing in Europe (apart from Italy) would be on closed circuits, initially on long loops of public highway and then, in 1907, on the first purpose-built track, England's

Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

.

Italy had been running road competitions since 1895, when a reliability trial was run from

Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

to

Asti

Asti ( , ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) of 74,348 inhabitants (1–1–2021) located in the Italy, Italian region of Piedmont, about east of Turin, in the plain of the Tanaro, Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and ...

and back. The country's first true motor race was held in 1897 along the shore of Lake Maggiore, from Arona to Stresa and back. This led to a long tradition of road racing, including events like Sicily's

Targa Florio

The Targa Florio was a public road Endurance racing (motorsport), endurance automobile race held in the mountains of Sicily near the island's capital of Palermo, Sicily, Palermo. Founded in 1906 Targa Florio, 1906, it was the oldest sports car ra ...

(from 1906) and ''Giro di Sicilia'' (Tour of Sicily, 1914), which went right round the island, both of which continued on and off until after World War II. The first Alpine event was held in 1898, the Austrian Touring Club's three-day Automobile Run through South Tyrol, which included the infamous

Stelvio Pass.

In

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, the legal maximum speed of precluded road racing, but in April and May 1900, the

Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland (the forerunner of the Royal Automobile Club) organised the Thousand Mile Trial, a 15-day event linking Britain's major cities in order to promote this novel form of transport. Seventy vehicles took part, the majority of them trade entries. They had to complete thirteen stages of route varying in length from at average speeds of up to the legal limit of , and tackle six hillclimb or speed tests. On rest days and at lunch halts, the cars were shown to the public in exhibition halls. This event was followed in 1901 by a five-day trial based in Glasgow The Scottish Automobile Club organised an annual Glasgow–London non-stop trial from 1902 to 1904, then the Scottish Reliability Trial from 1905.

[Cowbourne 2005 p 279] The Motor Cycling Club allowed cars to enter its trials and runs from 1904 (London–

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, London–

Land's End

Land's End ( or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

, London–

Exeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

).

In 1908 the Royal Automobile Club held its International Touring Car Trial, and in 1914 the Light Car Trial for manufacturers of cars up to 1400 cc, to test comparative performances. In 1924, the exercise was repeated as the Small Car Trials.

In

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, the Herkomer Trophy was first held in 1905, and again in 1906. This challenging five-day event attracted over 100 entrants to tackle its road section, a

hillclimb and a speed trial, but it was marred by poor organisation and confusing regulations. One participant had been Prince Henry of Austria, who with the Imperial Automobile Club of Germany, later created the first ''Prinz Heinrich Fahrt'' (Prince Henry Trial) in 1908. Another trial was held in 1910. These were very successful, attracting top drivers and works cars from major teams – several manufacturers added "Prince Henry" models to their ranges. The first Alpine Trial was held in 1909, in Austria, and by 1914 this was the toughest event of its kind, producing a star performance from Britain's

James Radley in his

Rolls-Royce Alpine Eagle.

In

Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

and

Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

The Last Race of the Empirewas held in the days prior to the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914. This period was later called the

July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

. A 706 mile car race of six stages through what is now Estonia and Latvia. The race was the third Baltic Automobile and Aero Club competition for the

Grand Duchess Victoria Feodrovna Prize. The participants were mainly of Tsarist Russian and German Nobility.

Two ultra-long distance challenges took place at this time. The

Peking-Paris of 1907 was not officially a competition, but a "raid", the French term for an expedition or collective endeavour whose promoters, the newspaper "Le Matin", rather optimistically expected participants to help each other; it was 'won' by Prince

Scipione Borghese

Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese (; 1 September 1577 – 2 October 1633) was an Italian cardinal, art collector and patron of the arts. A member of the Borghese family, he was the patron of the painter Caravaggio and the artist Bernini. His legac ...

,

Luigi Barzini, and Ettore Guizzardi in an

Itala

Itala may refer to:

* Itala (company), an Italian car manufacturer

** Itala Special, a special custom-built Grand Prix race car

* Itala (given name), an Italian given name

* Itala, Sicily, a municipality in Sicily

* Itala Film, an Italian film com ...

. The

New York–Paris of the following year, which went via Japan and

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, was won by George Schuster and others in a

Thomas Flyer. Each event attracted only a handful of adventurous souls, but in both cases the successful drivers exhibited characteristics modern rally drivers would recognise: meticulous preparation, mechanical skill, resourcefulness, perseverance and a certain single-minded ruthlessness. Rather gentler (and more akin to modern rallying) was the

Glidden Tour

The Glidden Tours, also known as the National Reliability Runs, were promotional events held during the automotive Brass Era by the American Automobile Association (AAA) and organized by the group's chairman, Augustus Post. The AAA, a proponent ...

, run by the

American Automobile Association

American Automobile Association (AAA) is a federation of motor clubs throughout North America. AAA is a privately held not-for-profit national member association and service organization with over 60 million members in the United States and Cana ...

between 1902 and 1913, which had timed legs between control points and a marking system to determine the winners.

Interwar years

The First World War brought a lull to motorsport. The Monte Carlo Rally was not revived until 1924, but since then, apart from World War II and its aftermath, it has been an annual event and remains a regular round of the World Rally Championship. In the 1930s, helped by the tough winters, it became the premier European rally, attracting 300 or more participants.

In the 1920s, numerous variations on the Alpine theme sprang up in Austria, Italy, France, Switzerland and Germany. The most important of these were Austria's ''Alpenfahrt'', which continued into its 44th edition in 1973, Italy's ''Coppa delle Alpi'', and the ''Coupe Internationale des Alpes'' (International Alpine Trial), organised jointly by the automobile clubs of Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and, latterly, France. This last event, run from 1928 to 1936, attracted strong international fields vying for an individual Glacier Cup or a team Alpine Cup, including successful

Talbot

Talbot is a dormant automobile marque introduced in 1902 by British-French company Clément-Talbot. The founders, Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, 20th Earl of Shrewsbury and Adolphe Clément-Bayard, reduced their financial interests in their Clément ...

,

Riley Riley may refer to:

Businesses

* Riley (brand), British sporting goods brand founded in 1878

* Riley Motor, British motorcar and bicycle manufacturera 1890–1969

* Riley Technologies, American auto racing constructor and team, founded by Bob ...

,

MG and

Triumph teams from Britain and increasingly strong and well funded works representation from

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's Germany, keen to prove its engineering and sporting prowess with successful marques like

Adler,

Wanderer

Wanderer, Wanderers, or The Wanderer may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film, television, and theater

* The Wanderer (1913 film), ''The Wanderer'' (1913 film), a silent film

* The Wanderer (1925 film), ''The Wanderer'' (1925 film), a silen ...

and Trumpf.

The French started their own ''

Rallye des Alpes Françaises'' in 1932, which continued after World War II as the ''Rallye International des Alpes'', the name often shortened to ''Coupe des Alpes''. Other rallies started between the wars included Britain's

RAC Rally

Wales Rally GB was the most recent iteration of the United Kingdom's premier international motor rally, which ran under various names since the first event held in 1932. It was consistently a round of the FIA World Rally Championship (WRC) cal ...

(1932) and Belgium's ''

Liège-Rome-Liège'' or just Liège, officially called "Le Marathon de la Route" (1931), two events of radically different character; the former a gentle tour between cities from various start points, "rallying" at a seaside resort with a series of manoeuvrability and car control tests; the latter a thinly disguised road race over some of Europe's toughest mountain roads.

In Ireland, the first ''Ulster Motor Rally'' (1931) was run from multiple starting points. After several years in this format, it transitioned into the

Circuit of Ireland Rally. In Italy,

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's government encouraged motorsport of all kinds and facilitated road racing, so the sport quickly restarted after World War I. In 1927 the ''

Mille Miglia

The Mille Miglia (, ''Thousand Miles'') was an open-road, motorsport Endurance racing (motorsport), endurance race established in 1927 by the young Counts :it:Franco Mazzotti, Francesco Mazzotti and Aymo Maggi. It took place in Italy 24 times f ...

'' (Thousand Mile) was founded, run over a loop of highways from

Brescia

Brescia (, ; ; or ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the region of Lombardy, in Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Lake Garda, Garda and Lake Iseo, Iseo. With a population of 199,949, it is the se ...

to Rome and back. It continued in this form until 1938.

The Liège of August 1939 was the last major event before World War II. Belgium's

Jean Trasenster (

Bugatti

Automobiles Ettore Bugatti was a German then French automotive industry, manufacturer of high performance vehicle, high-performance automobiles. The company was founded in 1909 in the then-German Empire, German city of Molsheim, Alsace, by the ...

) and France's

Jean Trevoux (

Hotchkiss) tied for first place, denying the German

works teams shortly before their countries were overrun. This was one of five Liège wins for Trasenster; Trevoux won four Montes between 1934 and 1951.

Post-World War II years

= Europe

=

Rallying was again slow to get under way after a major war, but by the 1950s there were many long-distance road rallies. In Europe, the Monte Carlo Rally, the French and Austrian Alpines, and the Liège were joined by a host of new events that quickly established themselves as classics: the Lisbon Rally (Portugal, 1947), the Tulip Rally (the Netherlands, 1949), the Rally to the Midnight Sun (Sweden, 1951, now the

Swedish Rally

The Rally Sweden (), formerly the KAK-Rally, the International Swedish Rally, and later the Uddeholm Swedish Rally, is an automobile rally competition held in February in Värmland, Sweden and relocated to Umeå in 2022. First held in 1950, as a ...

), the Rally of the 1000 Lakes (Finland, 1951 – now the

Rally Finland

Rally Finland (formerly known as the Neste Rally Finland, Neste Oil Rally Finland, 1000 Lakes Rally and Rally of the Thousand Lakes; , ) is a rallying, rally competition in the Finnish Lakeland in Central Finland. The rally is driven on wide an ...

), and the

Acropolis Rally

The Acropolis Rally of Greece () is a Rallying, rally competition that is part of the World Rally Championship, World Rally Championship (WRC). The rally is held on very dusty, rough, rocky and fast mountain roads in mainland Greece, usually dur ...

(Greece, 1956). The RAC Rally gained International status on its return in 1951, but for 10 years its emphasis on map-reading navigation and short manoeuvrability tests made it unpopular with foreign crews. The ''

FIA'' created in 1953 a

European Rally Championship

The European Rally Championship (officially FIA European Rally Championship) is an rallying, automobile rally competition held annually on the European continent and organized by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA).

The champion ...

(at first called the "Touring Championship") of eleven events; it was first won by

Helmut Polensky

Helmut Polensky (10 October 1915, Berlin – 6 November 2011, Saint-Tropez) was a German people, German Motorcycle racing, moto racer, Auto racing, racing driver and racing car constructor.

Life outside racing

Polensky was the youngest of ...

of Germany. This was the premier international rallying championship until 1973, when the FIA created the

World Rally Championship for Manufacturers.

Initially, most of the major post-war rallies were fairly gentlemanly, but the organisers of the French Alpine and the Liège (which moved its turning point from Rome into Yugoslavia in 1956) straight away set difficult time schedules: the ''Automobile Club de Marseille et Provence'' laid on a long tough route over a succession of rugged passes, stated that cars would have to be driven flat out from start to finish, and gave a coveted ''

Coupe des Alpes'' ("Alpine Cup") to anyone achieving an unpenalised run; while Belgium's Royal Motor Union made clear no car was expected to finish the Liège unpenalised – when one did (1951 winner

Johnny Claes

Octave John Claes (; 11 August 1916 – 3 February 1956) was a British-born racing driver who competed for Belgium. Before his fame as a racing driver, Claes was also a jazz trumpeter and successful bandleader in Britain.

Early life and jazz ...

in a

Jaguar XK120

The Jaguar XK120 is a sports car manufactured by Jaguar between 1948 and 1954. It was Jaguar's first sports car since SS 100 production ended in 1939. The XK120 was launched in open two-seater or (US) roadster form at the 1948 London Motor Sho ...

) they tightened the timing to make sure it never happened again. These two events became the ones for "the men" to do. The Monte, because of its glamour, got the media coverage and the biggest entries (and in snowy years was also a genuine challenge); while the Acropolis took advantage of Greece's appalling roads to become a truly tough event. In 1956 came Corsica's ''

Tour de Corse

The Tour de Corse is a rally first held in 1956 on the island of Corsica. It was the French round of the World Rally Championship from the inaugural 1973 season until 2008, was part of the Intercontinental Rally Challenge from 2011 to 2012, and ...

'', 24 hours of virtually non-stop flat out driving on some of the narrowest and twistiest mountain roads on the planet – the first major rally to be won by a woman, Belgium's in a

Renault Dauphine

The Renault Dauphine () is a rear-engine, rear-wheel-drive four-door economy car, economy sedan (car), sedan with three-box styling, manufactured and marketed by Renault from 1956 to 1967 across a single generation.

Along with such cars as the C ...

.

These events were road races in all but name, but in Italy such races were still allowed, and the ''Mille Miglia'' continued until a serious accident in 1957 caused it to be banned. Meanwhile, in 1981, the ''Tour de France'' was revived by the Automobile-Club de Nice as a different kind of rally, based primarily on a series of races at circuits and hillclimbs around the country. It was successful for a while and continued until 1986. It spawned similar events in a few other countries, but none survive.

= South America

=

In countries where there was no shortage of demanding roads across remote terrain, other events sprang up. In South America, the biggest of these took the form of long distance city to city races, each around , divided into daily legs. The first was the ''Gran Premio del Norte'' of 1940, run from

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

to

Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

and back; it was won by

Juan Manuel Fangio

Juan Manuel Fangio (, ; 24 June 1911 – 17 July 1995) was an Argentine racing driver, who competed in Formula One from to . Nicknamed "el Chueco" and "el Maestro", Fangio won five Formula One World Drivers' Championship titles and—at the ti ...

in a much modified

Chevrolet

Chevrolet ( ) is an American automobile division of the manufacturer General Motors (GM). In North America, Chevrolet produces and sells a wide range of vehicles, from subcompact automobiles to medium-duty commercial trucks. Due to the promi ...

coupé

A coupe or coupé (, ) is a passenger car with a sloping or truncated rear roofline and typically with two doors.

The term ''coupé'' was first applied to horse-drawn carriages for two passengers without rear-facing seats. It comes from the Fr ...

. This event was repeated in 1947, and in 1948 an even more ambitious one was held, the ''Gran Premio de la América del Sur'' from Buenos Aires to

Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

,

Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

—Fangio had an accident in which his co-driver was killed. Then in 1950 came the fast and dangerous

Carrera Panamericana

The Carrera Panamericana was a border-to-border sedan (stock and touring and sports car) rally racing event on open roads in Mexico similar to the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio in Italy. Running for five consecutive years from 1950 to 1954, i ...

, a road race in stages across Mexico to celebrate the opening of the asphalt highway between the

Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

and United States borders, which ran until 1954. All these events fell victim to the cost – financial, social and environmental – of putting them on in an increasingly complex and developed world, although smaller road races continued long after, and a few still do in countries like

Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

.

= Africa

=

In Africa, 1950 saw the first French-run

Algiers-Cape Town Rally

The Algiers-Cape Town Rally (or Mediterranean Rally) was an automobile rally competition organised by ''Les Amis du Sahara et de l'Eurafrique'' with the assistance of various African Automobile Clubs including ''the Association sportif de l'automob ...

, a rally from the Mediterranean to

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

; it was run on and off until 1961, when the new political situation hastened its demise. In 1953 East Africa saw the demanding Coronation Safari, which went on to become the

Safari Rally

The Safari Rally is an automobile rally held in Kenya. It was first held in 1953 as a celebration of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The event was part of the World Rally Championship from 1973 until 2002, before returning in 2021. It is h ...

and a World Championship round, to be followed in due course by the

Rallye du Maroc and the

Rallye Côte d'Ivoire

The Rallye Côte d'Ivoire, perhaps better known as the Rallye Bandama as it was originally called, or the Ivory Coast Rally, is a rally race held annually in Côte d'Ivoire in Africa. In common with other races on the continent, it is known for i ...

. Australia's

Redex Round Australia Trial also dates from 1953, although this remained isolated from the rest of the rallying world.

= North America

=

Canada hosted one of the world's longest and most gruelling rallies in the 1960s, the Shell 4000 Rally. It was the only one sanctioned by the

FIA in North America.

Intercontinental rallying

The quest for longer and tougher events saw the re-establishment of the intercontinental rallies beginning with the

London–Sydney Marathon held in 1968. The rally trekked across Europe, the Middle-East and the sub-continent before boarding a ship in Bombay to arrive in Fremantle eight days later before the final push across Australia to Sydney. It attracted over 100 crews including a number of works teams and top drivers; it was won by the

Hillman Hunter

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products ( fur/ hide, bone/tusks, ...

of Andrew Cowan/Brian Coyle/Colin Malkin. The huge success of this event saw the creation of the World Cup Rallies, linked to Association Football's FIFA World Cup. The first was the

1970 London to Mexico World Cup Rally which saw competitors travel from London eastwards across to Bulgaria before turning westwards on a more southerly route before boarding a ship in Lisbon. Disembarking in Rio de Janeiro the route travelled southward into Argentina before turning northwards along the western coast of South America before arriving in Mexico City. The

Ford Escort of Hannu Mikkola and Gunnar Palm won. These were followed in 1974 by the London-Sahara-Munich World Cup Rally, and in 1977 by the Singapore Airlines London-Sydney Rally.

Introduction of special stages

Rallying became very popular in Sweden and Finland in the 1950s, thanks in part to the invention there of the ''specialsträcka'' (Swedish) or ''erikoiskoe'' (Finnish), or special stage. These were shorter sections of route, usually on minor or private roads—predominantly gravel in these countries—away from habitation and traffic, which were separately timed. These provided the solution to the conflict inherent in the notion of driving as fast as possible on ordinary roads. The idea spread to other countries, albeit more slowly to the most demanding events.

The

RAC Rally

Wales Rally GB was the most recent iteration of the United Kingdom's premier international motor rally, which ran under various names since the first event held in 1932. It was consistently a round of the FIA World Rally Championship (WRC) cal ...

had formally become an International event in 1951, but Britain's laws precluded the closure of public highways for special stages. This meant it had to rely on short manoeuvrability tests, regularity sections and night map-reading navigation to find a winner, which made it unattractive to foreign crews. In 1961, Jack Kemsley was able to persuade the

Forestry Commission

The Forestry Commission is a non-ministerial government department responsible for the management of publicly owned forests and the regulation of both public and private forestry in England.

The Forestry Commission was previously also respons ...

to open their many hundreds of miles of well surfaced and sinuous gravel roads, and the event was transformed into one of the most demanding and popular in the calendar, by 1983 having over of stage. It was later renamed

Rally GB

Wales Rally GB was the most recent iteration of the United Kingdom's premier international motor rally, which ran under various names since the first event held in 1932. It was consistently a round of the FIA World Rally Championship (WRC) cal ...

.

Off road (cross country) rallying

In 1967, a group of American off-roaders created the Mexican 1000 rally, a tough 1,000-mile race for cars and motorcycles which ran the length of the

Baja California peninsula, much of it initially over roadless desert. Which quickly gained fame as the

Baja 1000

The Baja 1000 is an annual Mexican off-road motorsport race held on the Baja California Peninsula, with a course of up to about 850 or more miles. It is one of the most prestigious off-road races in the world, having attracted competitors from ...

, today run by the

SCORE International

SCORE International (Southern California Off Road Enthusiasts) is an off-road racing sanctioning body in the sport of desert racing. Founded by Mickey Thompson in 1973, SCORE International was purchased from Sal Fish in late 2012. and is run ...

. "Baja" events, relatively short cross-country rallies, now take place in a number of other countries worldwide.

In 1979, a young Frenchman,

Thierry Sabine, founded an institution when he organized the first "rallye-raid" from

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

to

Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

, in Senegal, the event now called the

Dakar Rally

The Dakar Rally () or simply "The Dakar" (), formerly known as the Paris–Dakar Rally (), is an annual rally raid organised by the Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO). It is an off-road endurance event traversing terrain much tougher than convent ...

. From amateur beginnings it quickly became a massive commercial circus catering for cars, motorcycles and trucks, and spawned other similar events. From 2008 to 2019, it was held in South America before moving to Saudi Arabia exclusively in 2020.

Characteristics of a rally

Itinerary

All rallies follow at least one itinerary, essentially a schedule of the points along the route that define the rally. A common (single) itinerary may begin and end with a ceremonial start and finish that confirm the bounds of the competition. Many rallies’ itineraries are divided into legs, usually corresponding with days on multi-day rallies dividing overnight rest periods; sections, usually between ''services'' or ''regroups''; and stages, individual point-to-point lengths of road. A loop is often used to describe a section that begins and ends in the same place, for example from a central service park.

A time control is usually found at each point on the itinerary, a timecard is carried by the crews and handed to an official at each control point to be filled in as proof of following the itinerary correctly. As crews start each leg, section and stage at intervals (for example of two minutes), each crew will have a different due or target time to arrive at each control, with penalties applied for being too early or late.

A crew can be excluded from a rally if they are found to be over time limit or outside total lateness (OTL). This is a maximum permitted lateness set, often 30 minutes, to prevent rally officials having to wait too long for the last car.

Long rallies may include one or more service, a window of time where mechanics are permitted to repair or prepare the car. Outside these services only the driver and co-driver can work on the car, although they must still respect the timing requirements of the rally. A flexi-service allows teams to use the same group of mechanics with flexibility in the timing, for example if two cars are due to arrive at two minute intervals, the second cars' 45 minute service can be delayed whilst the first car is serviced. During overnight halts between legs cars are held in a quarantine environment called

parc fermé

''Parc fermé'', literally meaning "closed park" in French, is a secure area at a motor racing circuit where the cars are kept at some times during a race meeting in order to prevent modifications.

Area

According to the FIA Formula One regulati ...

where it is not permitted to work on the cars.

Other examples of features of an itinerary include passage controls, which ensure competitors are following the correct route but have no due time window, the timecard may be stamped or the cars may be observed by officials. Refuel, light fitting and tyre zones allow competitors to refuel, fit lights for ''night stages'' run in darkness, or exchange used tyres for new. Regroups act to gather competitors in one location and reset the time intervals which may have grown or shrunk.

A road book may be published and distributed to competitors detailing the itinerary, the route they must follow and any supplementary regulations they must follow. The route can be marked out in tulip diagrams, a form of illustrating the navigational requirements or other standard icons.

Special stage

Special stages (SS) must be used when using timing for classifying competitors in speed competitions. These stages are preceded by a time control marking the boundary of a road section and the special stage. The competitors proceed to the start line from where they begin the special stage at a prescribed time, and are timed until they cross the flying finish in motion before safely coming to a stop at the stop control which acts as a time control for the following road section and the place for the crews to find out their time of completing the stage. To avoid interruptions and hindering other competitors the road between the time control and the end of the start line zone, and between the flying finish and stop control are both considered as under parc fermé conditions, crews are not allowed to get out of their car.

A Super Special Stage runs contrary to the ordinary running of a special stage, the reasons for which should be explained in the supplementary regulations. This may be where head-to-head stages are run in a crossover loop style, or if a short asphalt city stage with

donuts

A doughnut or donut () is a type of pastry made from leavened fried dough. It is popular in many countries and is prepared in various forms as a sweet snack that can be homemade or purchased in bakeries, supermarkets, food stalls, and franch ...

around hay bails is run on a gravel rally for example.

A Power Stage is used in the WRC and European Rally Championship, it is simply a nominated special stage that alone awards championship points to the fastest crews.

A Shakedown is often included in an itinerary but does not form part of the competition. Crews can do multiple passes of a special stage to practice or trial different set ups. In some championships, a Qualifying Stage may also run alongside a shakedown to determine road order, the order in which competitors will compete.

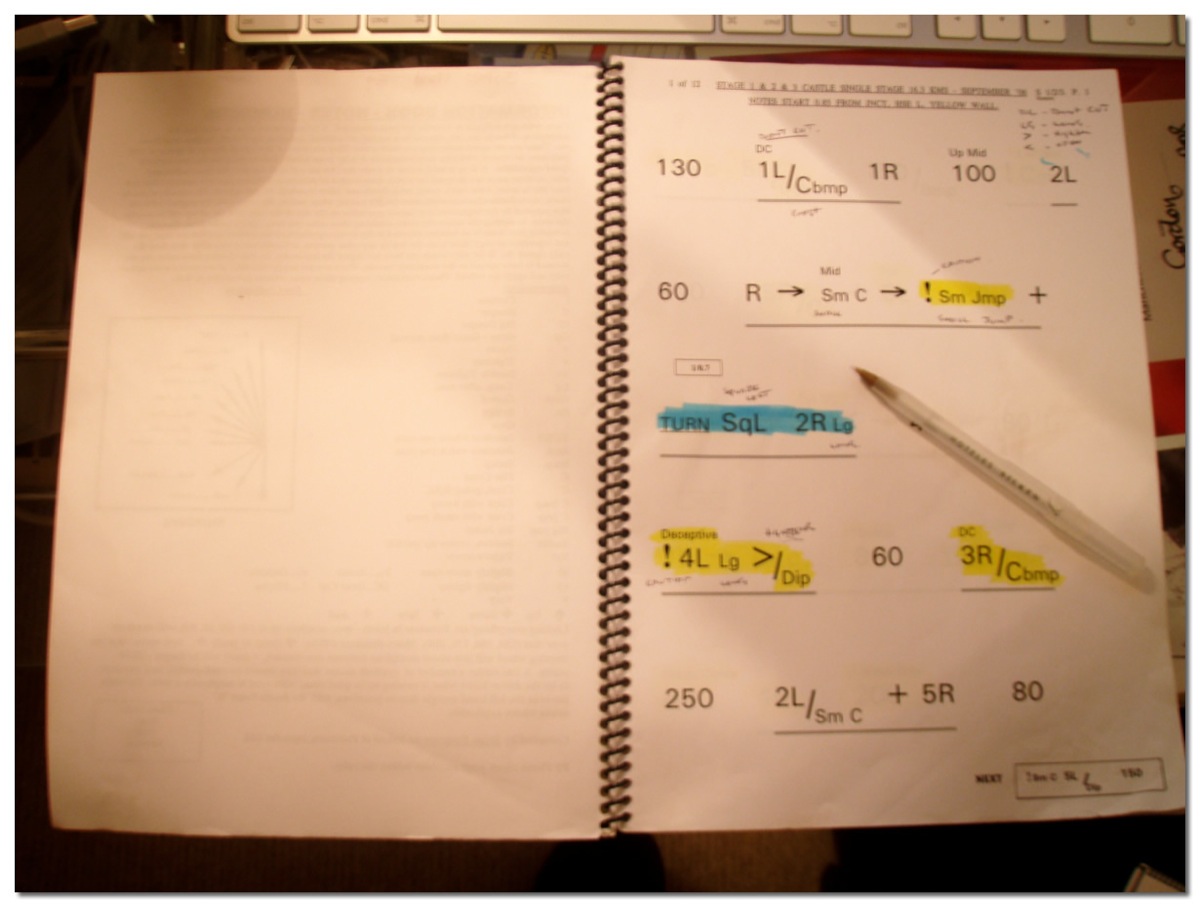

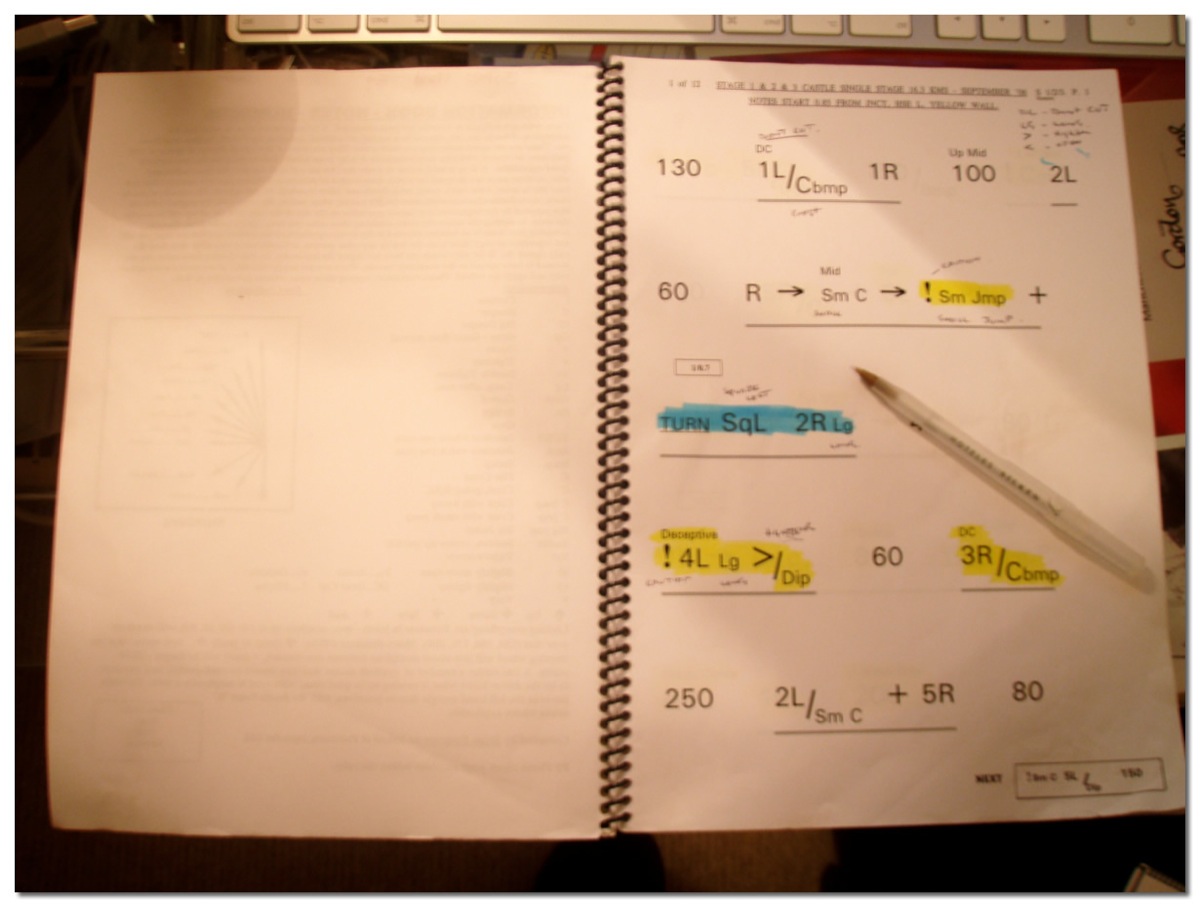

Recce and pacenotes

Pacenotes are a unique and major tool in modern special stage rallying. They provide a detailed description of the course and conditions ahead and allow the driver to form a mental image beyond the visible to be able to drive as fast as possible.

In many rallies, including those of the World Rally Championship (WRC), drivers are allowed to run on the special stages of the course before the competition begins and create their own pacenotes. This process is called reconnaissance or recce and a low maximum speed is imposed. During reconnaissance, the co-driver writes down shorthand notes on how to best drive the stage. Usually, the drivers call out the turns and road conditions for the co-drivers to write down. These pacenotes are then read aloud through an internal intercom system during the actual rally, allowing the driver to anticipate the upcoming terrain and thus take the course as fast as possible.

Other rallies provide organizer-created "route notes" also referred to as "stage notes" and disallow reconnaissance and use of custom pacenotes. These notes are usually created using a predetermined format, from which a co-driver can optionally add comments or transpose into other pacenote notations. Many North American rallies do not conduct reconnaissance but provide stage notes due to time and budget constraints.

Service park or bivouac

Though not necessary for all rallies, many road rallies have a central service park that acts as a base for servicing, scrutineering, parc fermé and playing host to Rally Headquarters, where the rally officials assemble. Service parks can also be a spectator attraction in their own right, with opportunities to meet and greet the crews and commercial outlets providing goods and services. If the rally is of the touring A to B kind there may be multiple service parks that may be very small and only used once each meaning teams carry as little as possible for simple logistics purposes. A remote service is a small service used once when there are stages far away from a central service park.

In off-road cross countries the service area and support teams may travel with the competitors along the route in a Bivouac. The word means 'camp' and many participants indeed sleep in tents overnight.

Participants

Driver

The driver is the person who

drives the car during the rally. Regardless of the type of rally, a driver needs a

driver's license

A driver's license, driving licence, or driving permit is a legal authorization, or the official document confirming such an authorization, for a specific individual to operate one or more types of motorized vehicles—such as motorcycles, ca ...

issued by a competent authority. No prior experience of rallying is necessary and a debutant can hypothetically compete with a world champion on unfamiliar roads even in speed competitions.

Unless the car is in a scheduled service, only the driver and co-driver can repair or work on the car during the rally with no external assistance allowed. Spectators assisting a crashed car is technically a breach of the rules but is usually overlooked. Driver's and co-drivers often have to make running-repairs and have to change punctured wheels themselves.

Often, a distinction is made between so called 'works' drivers and

privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

drivers. The first is one who competes for a team, usually that of a manufacturer, who provides the car, parts, repairs, logistics and the support personnel. Most of the works drivers of the 1950s were amateurs, paid little or nothing, reimbursed their expenses and given bonuses for winning. Then in 1960 came arguably the first rallying superstar (and one of the first to be paid to rally full-time), Sweden's

Erik Carlsson, driving for

Saab

Saab or SAAB may refer to:

Brands and enterprises

* Saab AB, a Swedish aircraft, aerospace and defence company, still known as SAAB, and together with subsidiaries as Saab Group

** Datasaab, a former computer company, started as spin off from Saab ...

. Contrarily a privateer has to meet all the organization requirements and expenses involved in competing and usually competes for the enjoyment rather than using the sport as a means of promotion or contesting a full championship.

A ''specialist driver'' is used to describe a driver who may have the skills and aptitude to win a rally of a certain surface but not on another. In the World Rally Championship which consists of different surfaces, a tarmac specialist driver may be employed by a team for example, on only the tarmac rounds. A privateer snow specialist may only enter the snow rounds. Some examples of specialist drivers are

Gilles Panizzi

Gilles Panizzi (born 19 September 1965) is a French former rally driver.

Panizzi was born in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Alpes-Maritimes. Like many of his fellow rally racing countrymen, Panizzi spent a great deal of his developmental driving years ...

, who obtained several victories on asphalt in the WRC while on gravel never passed fifth place;

Shekhar Mehta won five editions of the Safari Rally however he never aspired to win the world championship and the Swede

Mats Jonsson achieved his only two victories in the world, in the Rally Sweden. Historically, manufacturers always used local drivers due to their experience which ensured a certain result.

Unlike in many other sports, rally has no gender barriers and everybody can compete on equal terms in this regard, although historically there were cups and trophies only for women. One of the first prominent names was that of the Brit

Pat Moss, sister of F1 driver

Stirling Moss

Sir Stirling Craufurd Moss (17 September 1929 – 12 April 2020) was a British racing driver and sports broadcasting, broadcaster, who competed in Formula One from to . Widely regarded as one of the greatest drivers to never win the Formula On ...

, who won several rallies in her time. Later, Italy's Antonella Mandello, Germany's Isolde Holderies, Britain's Louise Aitken Walker and Sweden's Pernilla Walfridson stood out. The most notable was France's

Michèle Mouton

Michèle Hélène Raymonde Mouton (born 23 June 1951) is a French former rally driver. Competing in the World Rally Championship for the Audi factory team, she took four victories and finished runner-up in the drivers' world championship in 198 ...

who with co-driver,

Fabrizia Pons, became the first women to achieve victories in the world championship, in addition to the championship runner-up slots in 1982. As co-pilots in addition to the aforementioned Pons, the French Michèle Espinos "Biche" stood out, the Swedish

Tina Thörner

Maria Kristina Thörner (born in Säffle, Sweden on February 24, 1966) is a Swedish rally co-driver. Tina Thörner's career in motor sports started in 1990. Since then, she has won three FIA Ladies' World Rally Championship titles, a third and a ...

, the Venezuelan

Ana Goñi

Ana Goñi (born 19 April 1953) is a Venezuelans, Venezuelan rallying, rally co-driver and motorsport personality. She is best known as the co-driver of Swedish rally legend Stig Blomqvist. Aside from her motorsport interests, Goñi is the owner ...

or the Austrian

Ilka Minor

Ilka Minor (born 30 April 1975 in Klagenfurt) is a rallying co-driver from Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal state ...

.

Co-driver

The

co-driver

A co-driver is the navigator of a rally car in the sport of rallying, who sits in the front passenger seat. The co-driver's job is to navigate, commonly by reading off a set of pacenotes to the driver (what lies ahead, where to turn, the severity ...

accompanies the driver inside the car during a ''rally'' stage and is sometimes called a navigator. The co-driver and driver may swap roles although this is uncommon. On all rallies their responsibilities are mostly organizational, assisting to ensure the route is adhered to, the correct timing of the itinerary is met, ensuring completion of the timecard and avoiding penalties for being early or late when arriving at time controls. Usually the co-driver maintains communication with the team as the rally progresses.

On special stages, the co-driver's role is to notate pace notes during reconnaissance and recite them at the correct point the driver demands when competing. This is a skill in itself as it requires reading the notes of the unseen road ahead from a page whilst keeping track of the current location. Theoretically, the more pacenotes a co-driver can deliver gives the driver more detail of the road ahead. Incorrect pace notes called at very high speeds on blind corners or crests can easily lead to accidents.

The co-driver often exercises an important role in strategy, monitoring the state of rivals and in many cases acting as a psychologist, since they also encourage and advise the driver. The rapport between driver and co-driver must therefore be essential and it is common for a driver to change partners throughout their career if they do not feel comfortable. Perhaps for this reason it is very common to find relatives competing. Examples of this are the Panizzi brothers, who raced in France and the world championship, the Vallejo brothers in Spain or the world champion

Marcus Grönholm

Marcus Ulf Johan "Bosse" Grönholm (born February 5, 1968) is a Finland, Finnish former rallying, rally and rallycross driver, being part of a family of the Swedish-speaking population of Finland lineage. His son, Niclas Grönholm, is an upcoming ...

who took his brother-in-law as co-driver during his career.

Team

A rally team is not required and can exist in various forms but is usually only found in professional or commercial speed competition rallying such as is found in the WRC where manufacturer teams are required to enter multiple cars. Commercial teams exist to provide a service to privateers. A driver, co-driver and friends volunteering to help can also be called a team.

* Team principal: The team principal/boss/manager is the authoritative organizer and decision maker. They are ultimately responsible for recruitment of all positions, which rallies or championships to enter, technical development and maintenance of cars, and competitive aims or targets. They are generally a position found in manufacturer teams where they will also be responsible for promotional and commercial activities. In all cases a team principal will also be responsible for the financial management.

* Engineer: The engineer helps develop the car away from a rally, tuning it to be in best form for competition. During a rally, the engineer will assist the driver with the set-up of the car such as fine-tuning the suspension, differentials, gear ratios or deciding on correct tyres. The engineer may also be a mechanic.

* Mechanic: A mechanic repairs and services the car before, after and in scheduled services during the rally. It helps to be multiskilled covering things from panel-beating to electrical diagnostics to changing oil.

* Gravel crew or Route Note Crew: Despite the name, gravel crews are only found on asphalt rallies. These crews drive the stages as late as possible before the zero car to make last minute embellishments to the pace notes on the topic of traction. This is usually from weather conditions such as ice or snow or where gravel has been brought onto the road where cars have cut corners on a previous running of the stage. The gravel crews must work fast as they often run whilst their rally crews are competing other stages making the window for communication narrow.

Officials

* Rally director: Chief organiser and assumes overall responsibility of all competitors and officials.

* Stewards: Ensure the adherence to rules and regulations and decide penalties where breaches are found.

* Clerk of the course: Administration position responsible for compiling timings, results and penalties; compiling documents and communicating notices.

* Scrutineers: Technical position ensuring cars are safe and within regulations.

* Marshals: Usually volunteer positions overseeing the route of the rally, reporting and reacting to incidents.

* Timekeeper: Found at time controls on road sections and the start and finish line of special stages.

Vehicles

Auto manufacturers had entered cars in rallies, and in their forerunner and cousin events, from the very beginning. The 1894 Paris-Rouen race was mainly a competition between them, while the Thousand Mile Trial of 1900 had more trade than private entries. From the time that speed limits were introduced to the various nation's roads, rallies became mostly about reliability than speed. As a result rallies and trials became a great proving ground for any standard production vehicle, with no real need to purposely build a rally competition car until the special stage was introduced in the 1950s.

Although there had been exceptions like the outlandish Ford V8 specials created for the 1936 Monte Carlo Rally, rallies before World War II had tended to be for standard or near-standard production cars. After the war, most competing cars were production

saloons or

sports cars

A sports car is a type of automobile that is designed with an emphasis on dynamic performance, such as handling, acceleration, top speed, the thrill of driving, and racing capability. Sports cars originated in Europe in the early 1910s and ar ...

, with only minor modifications to improve performance, handling, braking and suspension. This naturally kept costs down and allowed many more people to afford the sport using ordinary cars, compared to the rally specials used today.

Groups 1–4

In 1954 the FIA introduced

Appendix J of the

International Sporting Code The International Sporting Code (ISC) is a set of rules applicable to all four-wheel motorsport as governed by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). It was first implemented in 1926.

The ISC consists of 20 articles and several Adde ...

, classifying touring and sports production cars for use in its competitions, including the new European Rally Championship, and cars had to be

homologated in order to compete. The Groups 1–9 within Appendix J changed frequently though

Group 1 Group 1 may refer to:

* Alkali metal, a chemical element classification for Alkali metal

* Group 1 (motorsport), a regulation set of the FIA for series-production touring cars used in motorsport.

* Group One Thoroughbred horse races, the leading e ...

,

Group 2 The term Group 2 may refer to:

* Alkaline earth metal

The alkaline earth metals are six chemical elements in group (periodic table), group 2 of the periodic table. They are beryllium (Be), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), barium (B ...

,

Group 3 Group 3 may refer to:

* Group 3 element, chemical element classification

* Group 3 (motorsport), FIA classification of cars used in auto racing and rallying

* Group 3, the third tier of races in worldwide Thoroughbred horse racing

* Group 3 image ...

and

Group 4 Group 4 may refer to:

*Group 4 element

Group 4 is the second group of transition metals in the periodic table. It contains only the four elements titanium (Ti), zirconium (Zr), hafnium (Hf), and rutherfordium (Rf). The group is also called the t ...

generally held the forms of unmodified or modified, series production touring and grand touring cars used in rallying.

As rallying grew in popularity,

car companies started to introduce special models or variants for rallying, such as the

British Motor Corporation

The British Motor Corporation Limited (BMC) was a United Kingdom, UK-based vehicle manufacturer formed in early 1952 to give effect to an agreed merger of the Morris Motors, Morris and Austin Motor Company, Austin businesses.Morris-Austin Merge ...

's

Mini Cooper Mini Cooper may refer to:

*Performance Cars of the original Mini series with uprated drive train and brakes, called the "Mini Cooper", made by the British Motor Corporation and also the successors 1961–1971, and 1990–2000

*Cars of the Mini (mar ...

, introduced in Group 2 in 1962, and its successor the Mini Cooper S (1963), developed by the

Cooper Car Company

The Cooper Car Company was a British car manufacturer founded in December 1947 by Charles Cooper and his son John Cooper. Together with John's boyhood friend, Eric Brandon, they began by building racing cars in Charles's small gar ...

. Shortly after,

Ford of Britain

Ford Motor Company Limited,The Ford 'companies' or corporate entities referred to in this article are:

* Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, Michigan, USA, incorporated 16 June 1903

* Ford Motor Company Limited, incorporated 7 December 1928. Current ...

first hired

Lotus to create a high-performance version of their

Cortina family car, then in 1968 launched the

Escort Twin Cam, one of the most successful rally cars of its era. Similarly,

Abarth

Abarth & C. S.p.A. () is an Italian racing- and road-car maker and performance division founded by Italo-Austrian Carlo Abarth in 1949. Abarth & C. S.p.A. is owned by Stellantis through its Italian subsidiary. Abarth's logo is a shield with a ...

developed high performance versions of

Fiats 124 roadster and

131 saloon.

Other manufacturers were not content with modifying their 'bread-and-butter' cars.

Renault

Renault S.A., commonly referred to as Groupe Renault ( , , , also known as the Renault Group in English), is a French Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automobile manufacturer established in 1899. The company curr ...

bankrolled the small volume sports-car maker

Alpine to transform their little

A110 Berlinette coupé into a world-beating rally car, and hired a skilled team of drivers to pilot it. In 1974 the

Lancia Stratos

The Lancia Stratos HF (''Tipo 829''), known as Lancia Stratos, is a rear mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive layout, rear mid-engined sports car designed for rallying, made by Italian car manufacturer Lancia. It was highly successful in competition, win ...

became the first car designed from scratch to win rallies.

These makers overcame the rules of FISA (as the FIA was called at the time) by building the requisite number of these models for the road, somewhat inventing the 'homologation special'.

Four-wheel-drive

In 1980, a German car maker,

Audi

Audi AG () is a German automotive manufacturer of luxury vehicles headquartered in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. A subsidiary of the Volkswagen Group, Audi produces vehicles in nine production facilities worldwide.

The origins of the compa ...

, at that time not noted for their interest in rallying, introduced a rather large and heavy coupé version of their family saloon, installed a

turbocharged

In an internal combustion engine, a turbocharger (also known as a turbo or a turbosupercharger) is a forced induction device that is powered by the flow of exhaust gases. It uses this energy to compress the intake air, forcing more air into the ...

2.1

litre

The litre ( Commonwealth spelling) or liter ( American spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metres (m3). A ...

five-cylinder engine, and fitted it with

four-wheel drive

A four-wheel drive, also called 4×4 ("four by four") or 4WD, is a two-axled vehicle drivetrain capable of providing torque to all of its wheels simultaneously. It may be full-time or on-demand, and is typically linked via a transfer case pr ...

, giving birth to the

Audi Quattro