Coronation Banquet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

English coronations were traditionally held at

English coronations were traditionally held at  A third recension was probably compiled during the reign of Henry I and was used at the coronation of his successor,

A third recension was probably compiled during the reign of Henry I and was used at the coronation of his successor,

The ''Liber Regalis'' was translated into English for the first time for the coronation of James I in 1603, partly as a result of the

The ''Liber Regalis'' was translated into English for the first time for the coronation of James I in 1603, partly as a result of the

The idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of

The idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of  In early modern coronations, the events inside the abbey were usually recorded by artists and published in elaborate

In early modern coronations, the events inside the abbey were usually recorded by artists and published in elaborate

The Archbishop of Canterbury, who has precedence over all other clergy and all laypersons except members of the royal family, traditionally officiates at coronations; in his absence, another bishop appointed by the monarch may take the archbishop's place. There have, however, been several exceptions. William I was crowned by the

The Archbishop of Canterbury, who has precedence over all other clergy and all laypersons except members of the royal family, traditionally officiates at coronations; in his absence, another bishop appointed by the monarch may take the archbishop's place. There have, however, been several exceptions. William I was crowned by the

Before the entrance of the sovereign, the litany of the saints is sung during the procession of the clergy and other dignitaries. For the entrance of the monarch, an anthem from Psalm 122, ''

Before the entrance of the sovereign, the litany of the saints is sung during the procession of the clergy and other dignitaries. For the entrance of the monarch, an anthem from Psalm 122, ''

After the Communion service is interrupted, the anthem '' Come, Holy Ghost'' is recited, as a prelude to the act of anointing. After this anthem, the Archbishop recites a prayer in preparation for the anointing, which is based on the ancient prayer ''Deus electorum fortitudo'' also used in the anointing of French kings. After this prayer, the coronation anthem ''Zadok the Priest'' (by George Frederick Handel) is sung by the choir; meanwhile, the ''crimson robe'' is removed, and the sovereign proceeds to the

After the Communion service is interrupted, the anthem '' Come, Holy Ghost'' is recited, as a prelude to the act of anointing. After this anthem, the Archbishop recites a prayer in preparation for the anointing, which is based on the ancient prayer ''Deus electorum fortitudo'' also used in the anointing of French kings. After this prayer, the coronation anthem ''Zadok the Priest'' (by George Frederick Handel) is sung by the choir; meanwhile, the ''crimson robe'' is removed, and the sovereign proceeds to the

The Archbishop of Canterbury lifts St Edward's Crown from the high altar, sets it back down, and says a prayer: "Oh God, the crown of the faithful; bless we beseech thee and sanctify this thy servant our king/queen, and as thou dost this day set a crown of pure gold upon his/her head, so enrich his/her royal heart with thine abundant grace, and crown him/her with all princely virtues through the King Eternal Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen". This prayer is the translation of the ancient formula ''Deus tuorum Corona fidelium'', which first appeared in the twelfth-century third recension.

The

The Archbishop of Canterbury lifts St Edward's Crown from the high altar, sets it back down, and says a prayer: "Oh God, the crown of the faithful; bless we beseech thee and sanctify this thy servant our king/queen, and as thou dost this day set a crown of pure gold upon his/her head, so enrich his/her royal heart with thine abundant grace, and crown him/her with all princely virtues through the King Eternal Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen". This prayer is the translation of the ancient formula ''Deus tuorum Corona fidelium'', which first appeared in the twelfth-century third recension.

The

Robes with which the Sovereign is invested (worn thereafter until Communion):

* '' Colobium sindonis'' ("shroud tunic") – the first robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a loose white undergarment of fine linen cloth edged with a lace border, open at the sides, sleeveless and cut low at the neck. It symbolises the derivation of royal authority from the people.

* ''Supertunica'' – the second robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a long coat of gold silk which reaches to the ankles and has wide-flowing sleeves. It is lined with rose-coloured silk, trimmed with gold lace, woven with national symbols and fastened by a sword belt. It derives from the full dress uniform of a consul of the

Robes with which the Sovereign is invested (worn thereafter until Communion):

* '' Colobium sindonis'' ("shroud tunic") – the first robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a loose white undergarment of fine linen cloth edged with a lace border, open at the sides, sleeveless and cut low at the neck. It symbolises the derivation of royal authority from the people.

* ''Supertunica'' – the second robe with which the sovereign is invested. It is a long coat of gold silk which reaches to the ankles and has wide-flowing sleeves. It is lined with rose-coloured silk, trimmed with gold lace, woven with national symbols and fastened by a sword belt. It derives from the full dress uniform of a consul of the

Historically, the coronation was immediately followed by a banquet held in

Historically, the coronation was immediately followed by a banquet held in

Coronations and the Royal Archives

at the Royal Family website

Coronations: An ancient ceremony

at the Royal Collection Trust website

A Synopsis of English and British Coronations

Planning the next Accession and Coronation: FAQs

by The Constitution Unit,

Book describing English medieval Coronation found in Pamplona

at the Medieval History of Navarre website (in Spanish)

''Elizabeth is Queen'' (1953)

47-minute documentary by

Coronation 1937 – Technicolor – Sound

newsreel by

Long to Reign Over Us, Chapter Three: The Coronation

by Lord Wakehurst on the Royal Channel at YouTube {{Anglican Liturgy, state=collapsed Monarchy of the United Kingdom Culture of the United Kingdom

The

The coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

of the monarch of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

is an initiation

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformatio ...

ceremony in which they are formally invested with regalia

Regalia ( ) is the set of emblems, symbols, or paraphernalia indicative of royal status, as well as rights, prerogatives and privileges enjoyed by a sovereign, regardless of title. The word originally referred to the elaborate formal dress and ...

and crowned at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. It corresponds to the coronations that formerly took place in other European monarchies, which have all abandoned coronations in favour of inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

or enthronement

An enthronement is a ceremony of inauguration, involving a person—usually a monarch or religious leader—being formally seated for the first time upon their throne. Enthronements may also feature as part of a larger coronation rite.

In ...

ceremonies. A coronation is a symbolic formality and does not signify the official beginning of the monarch's reign; ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' and '' de facto'' his or her reign commences from the moment of the preceding monarch's death or abdication, maintaining legal continuity of the monarchy.

The coronation usually takes place several months after the death of the monarch's predecessor, as it is considered a joyous occasion that would be inappropriate while mourning continues. This interval also gives planners enough time to complete the required elaborate arrangements. The most recent coronation took place on 6 May 2023 to crown King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

and Queen Camilla

Camilla (born Camilla Rosemary Shand, later Parker Bowles, 17 July 1947) is List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms as the wife of King Charles III.

Camilla was raised in East ...

.

The ceremony is performed by the archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, the most senior cleric in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, of which the monarch is supreme governor

The Supreme Governor of the Church of England is the titular head of the Church of England, a position which is vested in the British monarch.

. Other clergy and members of the British nobility

The British nobility is made up of the peerage and the gentry of the British Isles.

Though the UK is today a constitutional monarchy with strong democratic elements, historically the British Isles were more predisposed towards aristocratic gove ...

traditionally have roles as well. Most participants wear ceremonial uniforms or robes, and before the most recent coronation, some wore coronet

In British heraldry, a coronet is a type of crown that is a mark of rank of non-reigning members of the royal family and peers. In other languages, this distinction is not made, and usually the same word for ''crown'' is used irrespective of ra ...

s. Many government officials and guests attend, including representatives of other countries.

The essential elements of the coronation have remained largely unchanged for the past 1,000 years. The sovereign is first presented to, and acclaimed by, the people. The sovereign then swears an oath to uphold the law and the Church. Following that, the monarch is anointed

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body. By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or oth ...

with holy oil, invested with regalia, and crowned, before receiving the homage of their subjects. Consorts of kings are then anointed and crowned as queens. The service ends with a closing procession, and since the 20th century it has been traditional for the royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

to appear later on the balcony of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

to greet crowds and watch a flypast

''FlyPast'' is an aircraft magazine, published monthly, edited by Tom Allett, Steve Beebee and Jamie Ewan.

History and profile

The magazine started as a bi-monthly edition in May/June 1981 and its first editor was the late Mike Twite. It is ow ...

.

History

English coronations

English coronations were traditionally held at

English coronations were traditionally held at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, with the monarch seated on the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, also known as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair that is used by British monarchs when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronation. The chair was commissioned in 1296 b ...

. Main elements of the coronation service and the earliest form of oath can be traced to the ceremony devised by Saint Dunstan

Dunstan ( – 19 May 988), was an English bishop and Benedictine monk. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised. His work restored monastic life in En ...

for King Edgar's coronation in 973 AD at Bath Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is a parish church of the Church of England and former Benedictines, Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, Bath, Somerset, England. Founded in the 7th century, i ...

. It drew on ceremonies used by the kings of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

and those used in the ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

of bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

s. Two versions of coronation services, known as ''ordines'' (from the Latin ''ordo'' meaning "order") or recension

Recension is the practice of editing or revising a text based on critical analysis. When referring to manuscripts, this may be a revision by another author. The term is derived from the Latin ("review, analysis").

In textual criticism (as is the ...

s, survive from before the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

. It is not known if the first recension was ever used in England, and it was the second recension which was used by Edgar in 973 and by subsequent Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

and early Norman kings.

A third recension was probably compiled during the reign of Henry I and was used at the coronation of his successor,

A third recension was probably compiled during the reign of Henry I and was used at the coronation of his successor, Stephen

Stephen or Steven is an English given name, first name. It is particularly significant to Christianity, Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; he is w ...

, in 1135. While retaining the most important elements of the Anglo-Saxon rite, it may have borrowed from the consecration of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

from the ''Pontificale Romano-Germanicum

The ''Pontificale Romano-Germanicum'' ("Roman-Germanic pontifical"), also known as the ''PRG'', is a set of Latin documents of Catholic liturgical practice compiled in Saint Alban's Abbey, Mainz, under the reign of William (archbishop of Mainz), ...

'', a book of German liturgy compiled in Mainz

Mainz (; #Names and etymology, see below) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and with around 223,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 35th-largest city. It lies in ...

in 961, thus bringing the English tradition into line with continental practice. It remained in use until the coronation of Edward II in 1308 when the fourth recension was first used, having been compiled over several preceding decades. Although influenced by its French counterpart, the new ''ordo'' focussed on the balance between the monarch and his nobles and on the oath, neither of which concerned the absolutist French kings. One manuscript of this recension is the '' Liber Regalis'' at Westminster Abbey which has come to be regarded as the definitive version.

Following the start of the Reformation in England

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church. These events we ...

, the boy king Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

had been crowned in the first Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

coronation in 1547, during which Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

preached a sermon against idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

and "the tyranny of the bishops of Rome". However, six years later, he was succeeded by his half-sister Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

, who restored the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

rite. In 1559, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

underwent the last English coronation under the auspices of the Catholic Church; however, Elizabeth's insistence on changes to reflect her Protestant beliefs resulted in several bishops refusing to officiate at the service, and it was conducted by the low-ranking bishop of Carlisle

The Bishop of Carlisle is the Ordinary (officer), Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Carlisle in the Province of York.

The diocese covers the county of Cumbria except for Alston Moor and the former Sedbergh Rural District. The Episcop ...

, Owen Oglethorpe.

Scottish coronations

Scottish coronations were traditionally held atScone Abbey

Scone Abbey (originally Scone Priory) was a house of Augustinian canons located in Scone, Perthshire ( Gowrie), Scotland. Dates given for the establishment of Scone Priory have ranged from 1114 A.D. to 1122 A.D. However, historians have long b ...

in Perthshire

Perthshire (Scottish English, locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore, Angus and Perth & Kinross, Strathmore ...

, with the monarch seated on the Stone of Destiny. The original rituals were a fusion of ceremonies used by the kings of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

, based on the inauguration of Aidan by Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

in 574, and by the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

from whom the Stone of Destiny came. A crown does not seem to have been used until the inauguration of Alexander II in 1214. The ceremony included the laying on of hands

The laying on of hands is a religious practice. In Judaism, ''semikhah'' (, "leaning f the hands) accompanies the conferring of a blessing or authority.

In Christianity, Christian churches, chirotony. is used as both a symbolic and formal met ...

by a senior cleric and the recitation of the king's genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

.Thomas, pp. 46–47. The Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews (, ) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews (), the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

The name St Andrews is not the town or ...

(from 1472 an archbishop) usually presided, but other bishops and archbishops also performed at some coronations.

After the coronation of John Balliol

John Balliol or John de Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as Toom Tabard (meaning 'empty coat'), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

, the Stone was taken to Westminster Abbey in 1296 and in 1300–1301 Edward I of England had it incorporated into the English Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, also known as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair that is used by British monarchs when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronation. The chair was commissioned in 1296 b ...

. Its first certain use at an English coronation was that of Henry IV in 1399. Pope John XXII in a bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

of 1329 granted the kings of Scotland the right to be anointed and crowned. No record exists of the exact form of the medieval rituals, but a later account exists of the coronation of the 17-month-old infant James V at Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most historically and architecturally important castles in Scotland. The castle sits atop an Intrusive rock, intrusive Crag and tail, crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill ge ...

in 1513. The ceremony was held in a church, since demolished, within the castle walls and was conducted by the Bishop of Glasgow

The Archbishop of Glasgow is an archiepiscopal title that takes its name after the city of Glasgow in Scotland. The position and title were abolished by the Church of Scotland in 1689; and, in the Catholic Church, the title was restored by Pope ...

, because the Archbishop of St Andrews had been killed at the Battle of Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton or Brainston Moor was fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland and resulted in an English victory ...

. It is likely that the child would have been knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed before the start of the ceremony. The coronation itself started with a sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

, followed by the anointing and crowning, then the coronation oath, in this case taken for the child by an unknown noble or priest, and finally an oath of fealty and acclamation by the congregation.

James VI had been crowned in the Church of the Holy Rude

The Church of the Holy Rude (Scottish Gaelic: ''Eaglais na Crois Naoimh'') is the medieval parish church of Stirling, Scotland. It is named after the Holyrood (cross), Holy Rood, a relic of the True Cross on which Jesus was crucified. The church ...

at Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

in 1567. After the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

, he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 25 July 1603. His son Charles I travelled north for a Scottish coronation at Holyrood Abbey

Holyrood Abbey is a ruined abbey of the Canons Regular in Edinburgh, Scotland. The abbey was founded in 1128 by David I of Scotland. During the 15th century, the abbey guesthouse was developed into a List of British royal residences,

royal r ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

in 1633, but caused consternation amongst the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

Scots by his insistence on elaborate High Anglican

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although used in connection with various Christian ...

ritual, arousing "gryt feir of inbriginge of poperie". Charles II underwent a simple Presbyterian coronation ceremony at Scone

A scone ( or ) is a traditional British and Irish baked good, popular in the United Kingdom and Ireland. It is usually made of either wheat flour or oatmeal, with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often ...

in 1651, but his brother James VII and II was never crowned in Scotland, although Scottish peers attended his 1685 coronation in London, setting a precedent for future ceremonies. The coronation of Charles II was the last to take place in Scotland, and no bishop presided as the episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

had been abolished; the ''de facto'' head of government, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll (March 160727 May 1661) was a Scottish nobleman, politician, and peer. The ''de facto'' head of Scotland's government during most of the conflict of the 1640s and 1650s known as the Wars of the Three K ...

, crowned Charles instead.

Modern coronations

The ''Liber Regalis'' was translated into English for the first time for the coronation of James I in 1603, partly as a result of the

The ''Liber Regalis'' was translated into English for the first time for the coronation of James I in 1603, partly as a result of the reformation in England

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church. These events we ...

requiring services to be understood by the people, but also an attempt by antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

s to recover a lost English identity from before the Norman Conquest. In 1685, James II, who was a Catholic, ordered a truncated version of the service omitting the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

, but this was restored for later monarchs. Only four years later, the service was again revised by Henry Compton Henry Compton may refer to:

* Henry Compton (bishop) (1632–1713), English bishop and nobleman

* Henry Compton, 1st Baron Compton (1544–1589), English peer, MP for Old Sarum

* Henry Combe Compton (1789–1866), British Conservative Party polit ...

for the coronation of William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

. The Latin text was resurrected for the 1714 coronation of the German-speaking George I, since it was the only common language between the king and the clergy. Perhaps because the 1761 coronation of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

had been beset by "numerous mistakes and stupidities", the next time around, spectacle overshadowed the religious aspect of the service. The coronation of George IV

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George IV as king of the United Kingdom took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on 19 July 1821. Originally scheduled for 1 August of the previous year, the ceremony had been postponed due t ...

in 1821 was an expensive and lavish affair with a vast amount of money being spent on it.

George's brother and successor William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded hi ...

had to be persuaded to be crowned at all; his coronation at a time of economic depression in 1831 cost only one sixth of that spent on the previous event. Traditionalists threatened to boycott what they called a " Half Crown-nation".Strong, p. 401. The king merely wore his robes over his uniform as Admiral of the Fleet

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

. For this coronation, a number of economising measures were made which would set a precedent followed by future monarchs. The assembly of peers and ceremonial at Westminster Hall involving the presentation of the regalia to the monarch was eliminated. The procession from Westminster Hall to the Abbey on foot was likewise eliminated and in its place, a state procession by coach from St James's Palace to the abbey was instituted, an important feature of the modern event. The coronation banquet after the service proper was also terminated.

When Victoria was crowned in 1838, the service followed the pared-down precedent set by her uncle, and the under-rehearsed ceremonial, again presided over by William Howley

William Howley (12 February 1766 – 11 February 1848) was a clergyman in the Church of England. He served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1828 to 1848.

Early life, education, and interests

Howley was born in 1766 at Ropley, Hampshire, wher ...

, was marred by mistakes and accidents. The music in the abbey was widely criticised in the press, only one new piece having been written for it, and the large choir and orchestra were badly coordinated.

In the 20th century, liturgical scholars sought to restore the spiritual meaning of the ceremony by rearranging elements with reference to the medieval texts, creating a "complex marriage of innovation and tradition". The greatly increased pageantry of the state processions was intended to emphasise the strength and diversity of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

.

Bringing coronations to the people

The idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of

The idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

who was a 10-year-old boy, thought unlikely to command respect simply by his physical appearance. On the day before the coronation, the boy king and his retinue were met outside the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

by the lord mayor

Lord mayor is a title of a mayor of what is usually a major city in a Commonwealth realm, with special recognition bestowed by the sovereign. However, the title or an equivalent is present in other countries, including forms such as "high mayor". A ...

, aldermen

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law with similar officials existing in the Netherlands (wethouder) and Belgium (schepen). The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking membe ...

and the livery companies

A livery company is a type of guild or professional association that originated in medieval times in London, England. Livery companies comprise London's ancient and modern trade associations and guilds, almost all of which are Style (form of a ...

, and he was conducted to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

where he spent the night in vigil

A vigil, from the Latin meaning 'wakefulness' ( Greek: , or ), is a period of purposeful sleeplessness, an occasion for devotional watching, or an observance. The Italian word has become generalized in this sense and means 'eve' (as in "on t ...

. The following morning, the king travelled on horseback in a great procession through the decorated city streets to Westminster. Bands played along the route, the public conduits flowed with red and white wine, and an imitation castle had been built in Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

, probably to represent the New Jerusalem

In the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible, New Jerusalem (, ''YHWH šāmmā'', YHWH sthere") is Ezekiel's prophetic vision of a city centered on the rebuilt Holy Temple, to be established in Jerusalem, which would be the capital of the ...

, where a girl blew gold leaf

upA gold nugget of 5 mm (0.2 in) in diameter (bottom) can be expanded through hammering into a gold foil of about 0.5 m2 (5.4 sq ft). The Japan.html" ;"title="Toi gold mine museum, Japan">Toi gold mine museum, Japan.

Gold leaf is gold that has ...

over the king and offered him wine. Similar, or even more elaborate pageants continued until the coronation of Charles II in 1661. Charles's pageant was watched by Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

who wrote: "So glorious was the show with gold and silver that we were not able to look at it". James II abandoned the tradition of the pageant to pay for jewels for his queen and thereafter there was only a short procession on foot from Westminster Hall

Westminster Hall is a medieval great hall which is part of the Palace of Westminster in London, England. It was erected in 1097 for William II (William Rufus), at which point it was the largest hall in Europe. The building has had various functio ...

to the abbey. For the coronation of William IV and Adelaide in 1831, a state procession from St James's Palace to the abbey was instituted, and this pageantry is an important feature of the modern event.

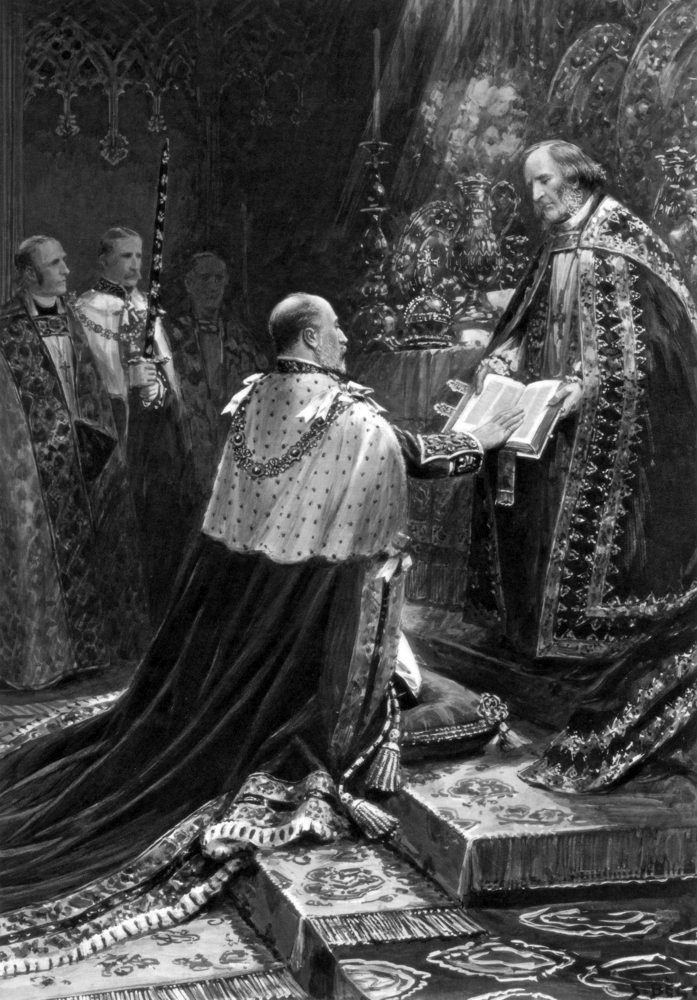

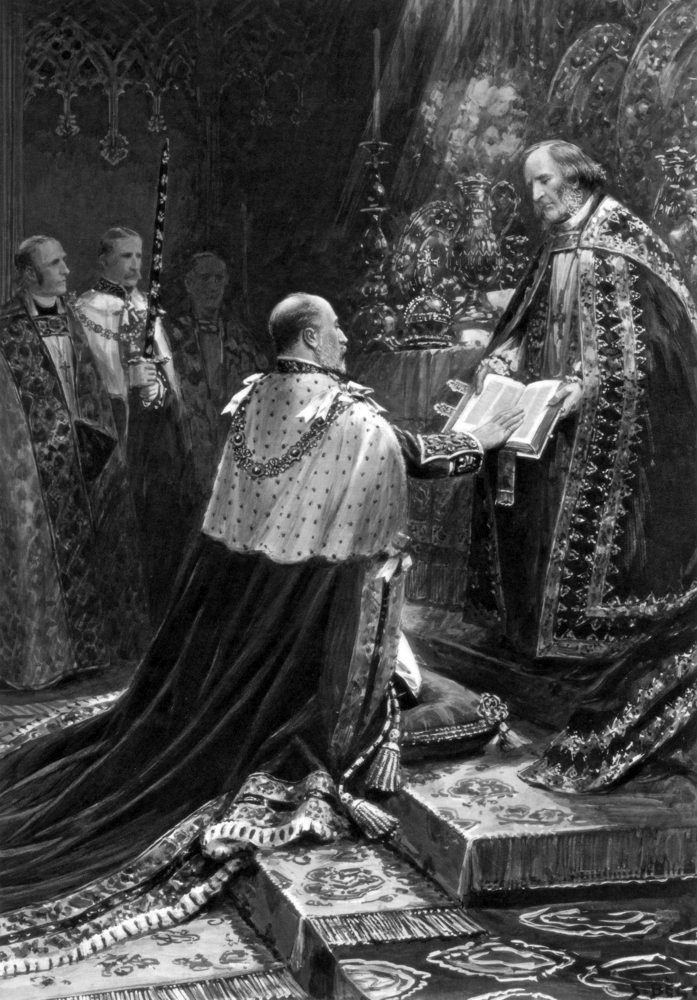

In early modern coronations, the events inside the abbey were usually recorded by artists and published in elaborate

In early modern coronations, the events inside the abbey were usually recorded by artists and published in elaborate folio

The term "folio" () has three interconnected but distinct meanings in the world of books and printing: first, it is a term for a common method of arranging Paper size, sheets of paper into book form, folding the sheet only once, and a term for ...

books of engravings,Strong, p. 415. the last of these was published in 1905 depicting the coronation which had taken place three years earlier.Strong, p. 432. Re-enactments of the ceremony were staged at London and provincial theatres; in 1761, a production featuring the Westminster Abbey choir at the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is a theatre in Covent Garden, central London. The building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. The ROH is the main home of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orch ...

in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

ran for three months after the real event. In 1902, a request to record the ceremony on a gramophone record

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English) or a vinyl record (for later varieties only) is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The g ...

was rejected, but Sir Benjamin Stone photographed the procession into the abbey. Nine years later, at the coronation of George V, Stone was allowed to photograph the recognition, the presentation of the swords, and the homage.

The coronation of George VI in 1937 was broadcast on radio by the British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public broadcasting, public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved in ...

(BBC), and parts of the service were filmed and shown in cinemas. The state procession was shown live

Live may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Live!'' (2007 film), 2007 American film

* ''Live'' (2014 film), a 2014 Japanese film

* ''Live'' (2023 film), a Malayalam-language film

*'' Live: Phát Trực Tiếp'', a Vietnamese-langua ...

on the new BBC Television Service

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's oldest and Flagship (broadcasting), flagship channel, and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includ ...

, the first major outside broadcast

Outside or Outsides may refer to:

* Wilderness

Books and magazines

* ''Outside'', a book by Marguerite Duras

* Outside (magazine), ''Outside'' (magazine), an outdoors magazine

Film, theatre and TV

* Outside TV (formerly RSN Television), a televi ...

. At Elizabeth II's coronation in 1953, most of the proceedings inside the abbey were also televised by the BBC. Originally, events as far as the choir screen were to be televised live, with the remainder to be filmed and released later after any mishaps were edited out. This would prevent television viewers from seeing most of the highlights of the coronation, including the actual crowning, live; it led to controversy in the press and even questions in parliament. The organising committee subsequently decided that the entire ceremony would be televised, except for the anointing and communion, which had also been excluded from photography at the last coronation. It was revealed 30 years later that the about-face was due to the personal intervention of the Queen. It is estimated that over 20 million people watched the broadcast in the United Kingdom. The coronation contributed to the increase of public interest in television, which rose significantly.

Commonwealth realms

The need to include the various elements of theBritish Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

in coronations was not considered until 1902, when it was attended by the prime ministers and governors-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

of the British Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of colonial self-governance increased (and, in ...

s, by then almost completely autonomous

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be defi ...

, and also by many of the rulers of the Indian Princely States

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Associated with India

* of or related to India

** Indian people

** Indian diaspora

** Languages of India

** Indian English, a dialect of the English language

** Indian cuisine

Associated with indigenous peoples o ...

and the various British Protectorate

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

s. An Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

was held afterwards. In 1911, the procession inside Westminster Abbey included the banners of the dominions, India and the Home Nations. By 1937, the Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly increased the autonomy of the Dominions of the British Commonwealth.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of t ...

had made the dominions fully independent, and the wording of the coronation oath was amended to include their names and confine the elements concerning religion to the United Kingdom.

Thus since 1937, the monarch has been simultaneously crowned as sovereign of several independent nations besides the United Kingdom, known since 1953 as the Commonwealth realms

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the ...

. Elizabeth II was asked, for example: "Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?" In 2023, the oath was amended to avoid reciting the realms other than the United Kingdom during the coronation of Charles III

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Charles III and his wife, Queen Camilla, Camilla, as Monarchy of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth re ...

.

Preparations

Timing

The timing of the coronation has varied throughout British history. King Edgar's coronation was some 15 years after his accession in 959 and may have been intended to mark the high point of his reign, or that he reached the age of 30, the age at whichJesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

Christ was baptised. Harold II was crowned on the day after the death of his predecessor, Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

, the rush probably reflecting the contentious nature of Harold's succession;Strong, p. 38. whereas the first Norman monarch, William I, was also crowned on the day he became king, 25 December 1066, but three weeks since the surrender of English nobles and bishops at Berkhampstead, allowing time to prepare a spectacular ceremony. Most of his successors were crowned within weeks, or even days, of their accession. Edward I was fighting in the Ninth Crusade

Lord Edward's Crusade, sometimes called the Ninth Crusade, was a military expedition to the Holy Land under the command of Edward I of England, Prince Edward Longshanks (later king as Edward I) in 1271 – 1272. In practice an extension of t ...

when he acceded to the throne in 1272; he was crowned soon after his return in 1274. Edward II's coronation, similarly, was delayed by a campaign in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in 1307. Henry VI was only a few months old when he acceded in 1422; he was crowned in 1429, but did not officially assume the reins of government until he was deemed of sufficient age, in 1437. Pre-modern coronations were usually either on a Sunday, the Christian Sabbath

Many Christians observe a weekly day set apart for rest and worship called a Sabbath in obedience to God's commandment to remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Early Christians, at first mainly Jewish, observed the seventh-day (Saturday) S ...

, or on a Christian holiday

The liturgical year, also called the church year, Christian year, ecclesiastical calendar, or kalendar, consists of the cycle of liturgical days and seasons that determines when feast days, including celebrations of saints, are to be obser ...

. Edgar's coronation was at Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day, Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spiri ...

, William I's on Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a Religion, religious and Culture, cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by coun ...

Day, possibly in imitation of the Byzantine emperors, and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

's was on Ascension Day

The Feast of the Ascension of Jesus Christ (also called the Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord, Ascension Day, Ascension Thursday, or sometimes Holy Thursday) commemorates the Christian belief of the bodily Ascension of Jesus into Heaven. It ...

. Elizabeth I consulted her astrologer

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, teacher, astrologer, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divination, ...

, before deciding on an auspicious date. The coronations of Charles II in 1661 and Anne in 1702 were on St George's Day

Saint George's Day is the Calendar of saints, feast day of Saint George, celebrated by Christian churches, countries, regions, and cities of which he is the Patronages of Saint George, patron saint, including Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bu ...

, the feast of the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of England.

Under the Hanoverian monarchs in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was deemed appropriate to extend the waiting period to several months, following a period of mourning for the previous monarch and to allow time for preparation of the ceremony.

In the case of every monarch between George IV and George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

, at least one year passed between accession and coronation. Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

was not crowned and his successor George VI was crowned 5 months after his accession. The coronation date of his predecessor had already been set; planning simply continued with a new monarch. The coronation of Charles III and Camilla

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Charles III and his wife, Queen Camilla, Camilla, as Monarchy of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth re ...

was held on 6 May 2023, eight months after he acceded to the throne.

Since a period of time has often passed between accession and coronation, some monarchs were never crowned. Edward V

Edward V (2 November 1470 – ) was King of England from 9 April to 25 June 1483. He succeeded his father, Edward IV, upon the latter's death. Edward V was never crowned, and his brief reign was dominated by the influence of his uncle and Lord ...

and Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554), also known as Lady Jane Dudley after her marriage, and nicknamed as the "Nine Days Queen", was an English noblewoman who was proclaimed Queen of England and Ireland on 10 July 1553 and reigned ...

were both deposed before they could be crowned, in 1483 and 1553, respectively. Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

also went uncrowned, as he abdicated in 1936 before the end of the customary one-year period between accession and coronation. A monarch, however, accedes to the throne the moment their predecessor dies, not when they are crowned, hence the traditional proclamation: "The king is dead, long live the king!

"The king is dead, long live the king!" is a traditional proclamation made following the accession of a new monarch in various countries. The seemingly contradictory phrase simultaneously announces the death of the previous monarch and asserts co ...

"

Location

TheAnglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

monarchs used various locations for their coronations, including Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames, colloquially known as Kingston, is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, south-west London, England. It is situated on the River Thames, south-west of Charing Cross. It is an ancient market town, notable as ...

, London, and Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

. The last Anglo-Saxon monarch, Harold II, was crowned at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

in 1066; the location was preserved for all future coronations. When London was under the control of rebels, Henry III was crowned at Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

in 1216; he later chose to have a second coronation at Westminster in 1220. Two hundred years later, Henry VI also had two coronations; as king of England in London in 1429, and as king of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

in Paris in 1431.

Coronation of consorts and others

Coronations may be performed for a person other than the reigning monarch. In 1170,Henry the Young King

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. In 1170, he became titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Maine. Henry th ...

, heir apparent to the throne, was crowned as a second king of England, subordinate to his father Henry II; such coronations were common practice in mediaeval France and Germany, but this is only one of two instances of its kind in England (the other being that of Ecgfrith of Mercia in 796, crowned whilst his father, Offa of Mercia

Offa ( 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death in 796. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of ...

, was still alive). More commonly, a king's wife is crowned as queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king, and usually shares her spouse's social Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and status. She holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles and may be crowned and anointed, but hi ...

. If the king is already married at the time of his coronation, a joint coronation of both king and queen may be performed. The first such coronation was of Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

in 1154; eighteen such coronations have been performed, including that of the co-rulers William III and Mary II. The most recent was that of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

and his wife Camilla in 2023. If the king married, or remarried, after his coronation, or if his wife was not crowned with him for some other reason, she might be crowned in a separate ceremony. The first such separate coronation of a queen consort in England was that of Matilda of Flanders in 1068; the last was Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

's in 1533. The most recent king to wed post-coronation, Charles II, did not have a separate coronation for his bride, Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza (; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, King Charles II, which la ...

. In some instances, the king's wife was simply unable to join him in the coronation ceremony due to circumstances preventing her from doing so. In 1821, George IV's estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Caroline Amelia Elizabeth; 17 May 1768 – 7 August 1821) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Queen of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until her ...

was not invited to the ceremony; when she showed up at Westminster Abbey anyway, she was denied entry and turned away. Following the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

declined the crown but underwent a coronation in all but name in his second investiture as Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

in 1657.

Participants

Clergy

The Archbishop of Canterbury, who has precedence over all other clergy and all laypersons except members of the royal family, traditionally officiates at coronations; in his absence, another bishop appointed by the monarch may take the archbishop's place. There have, however, been several exceptions. William I was crowned by the

The Archbishop of Canterbury, who has precedence over all other clergy and all laypersons except members of the royal family, traditionally officiates at coronations; in his absence, another bishop appointed by the monarch may take the archbishop's place. There have, however, been several exceptions. William I was crowned by the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

, since the Archbishop of Canterbury had been appointed by the Antipope

An antipope () is a person who claims to be Bishop of Rome and leader of the Roman Catholic Church in opposition to the officially elected pope. Between the 3rd and mid-15th centuries, antipopes were supported by factions within the Church its ...

Benedict X, and this appointment was not recognised as valid by the Pope. Edward II was crowned by the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire.

The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' the offic ...

because the Archbishop of Canterbury had been exiled by Edward I. Mary I, a Catholic, refused to be crowned by the Protestant Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

; the coronation was instead performed by the Bishop of Winchester. Elizabeth I was crowned by the Bishop of Carlisle

The Bishop of Carlisle is the Ordinary (officer), Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Carlisle in the Province of York.

The diocese covers the county of Cumbria except for Alston Moor and the former Sedbergh Rural District. The Episcop ...

(to whose see is attached no special precedence) because the senior prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Minister (Christianity), Christian clergy who is an Ordinary (church officer), ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which me ...

s were "either dead, too old and infirm, unacceptable to the queen, or unwilling to serve". Finally, when James II was deposed and replaced with William III and Mary II jointly, the Archbishop of Canterbury refused to recognise the new sovereigns; he had to be replaced by the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

, Henry Compton Henry Compton may refer to:

* Henry Compton (bishop) (1632–1713), English bishop and nobleman

* Henry Compton, 1st Baron Compton (1544–1589), English peer, MP for Old Sarum

* Henry Combe Compton (1789–1866), British Conservative Party polit ...

. Hence, in almost all cases where the Archbishop of Canterbury has failed to participate, his place has been taken by a senior cleric: the Archbishop of York is second in precedence, the Bishop of London third, the Bishop of Durham fourth, and the Bishop of Winchester fifth.

Bishops Assistant

From the moment they enter the Abbey until the moment they leave, the monarch is flanked by two supporting bishops of the Church of England.The part played by two supporting bishops dates back to the coronation ofThe Bishop of Durham stands on the monarch's right and the Bishop of Bath and Wells on their left. During the Coronation of KingEdgar Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear"). Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...in 973: two bishops led him by hand into Bath Abbey. Since the coronation ofRichard I Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion () because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior, was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ru ...in 1189, the Bishops of Bath & Wells and Durham have assumed this duty.

Custom has it that they accompany the monarch throughout the ceremony, flanking them as they process from the entrance of Westminster Abbey and standing either side of St Edward's Chair during the anointing. Bishops Assistant may also carry the Bible, paten, and chalice in the procession.

Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, Queen Camilla

Camilla (born Camilla Rosemary Shand, later Parker Bowles, 17 July 1947) is List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms as the wife of King Charles III.

Camilla was raised in East ...

was similarly accompanied by Bishops Assistant – the Bishops of Hereford and of Norwich – on her right and left respectively.

Great Officers of State

TheGreat Officers of State

Government in medieval monarchies generally comprised the king's companions, later becoming the royal household, from which the officers of state arose. These officers initially had household and governmental duties. Later some of these offic ...

traditionally participate during the ceremony. The offices of Lord High Steward

The Lord High Steward is the first of the Great Officers of State in England, nominally ranking above the Lord Chancellor.

The office has generally remained vacant since 1421, and is now an ''ad hoc'' office that is primarily ceremonial and ...

and Lord High Constable have not been regularly filled since the 15th and 16th centuries respectively; they are, however, revived for coronation ceremonies. The Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal but above the Lord High Constable of England, Lord High Constable. The office of Lo ...

enrobes the sovereign with the ceremonial vestments, with the aid of the Groom of the Robes and the Master

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

(in the case of a king) or Mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a female lover of a married man

** Royal mistress

* Maîtresse-en-titre, official mistress of a ...

(in the case of a queen) of the Robes.

The Barons Barons may refer to:

*Baron (plural), a rank of nobility

*Barons (surname), a Latvian surname

*Barons, Alberta, Canada

* ''Barons'' (TV series), a 2022 Australian drama series

* ''The Barons'', a 2009 Belgian film

Sports

* Birmingham Barons, a Min ...

of the Cinque Ports

The confederation of Cinque Ports ( ) is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier (Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to ...

also participated in the ceremony. Formerly, the barons were the members of the House of Commons representing the Cinque Ports of Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

, New Romney

New Romney is a market town in Kent, England, on the edge of Romney Marsh, an area of flat, rich agricultural land reclaimed from the sea after the harbour began to silt up. New Romney, one of the original Cinque Ports, was once a sea port, w ...

, Hythe, Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

and Sandwich

A sandwich is a Dish (food), dish typically consisting variously of meat, cheese, sauces, and vegetables used as a filling between slices of bread, or placed atop a slice of bread; or, more generally, any dish in which bread serves as a ''co ...

. Reforms in the 19th century, however, integrated the Cinque Ports into a regular constituency system applied throughout the nation. At later coronations, barons were specially designated from among the city councillors for the specific purpose of attending coronations. Originally, the barons were charged with bearing a ceremonial canopy over the sovereign during the procession to and from Westminster Abbey. The last time the barons performed such a task was at the coronation of George IV

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George IV as king of the United Kingdom took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on 19 July 1821. Originally scheduled for 1 August of the previous year, the ceremony had been postponed due t ...

in 1821. The barons did not return for the coronations of William IV (who insisted on a simpler, cheaper ceremonial) and Victoria. At coronations since Victoria's, the barons have attended the ceremony, but they have not carried canopies.

Other claims to attend the coronation

Many landowners and other persons have honorific "duties" or privileges at the coronation. Such rights have traditionally been determined by a special Court of Claims, over which the Lord High Steward traditionally presided. The first recorded Court of Claims was convened in 1377 for the coronation ofRichard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Joan, Countess of Kent. R ...

. By the Tudor period, the hereditary post of Lord High Steward had merged with the Crown, and so Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement wit ...

began the modern tradition of naming a temporary Steward for the coronation only, with separate commissioners to carry out the actual work of the court.

In 1952, for example, the court accepted the claim of the Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the abbey's status as a royal peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterb ...

to advise the Queen on the proper procedure during the ceremony (for nearly a thousand years he and his predecessor abbots have kept an unpublished Red Book of practices), the claim of the Lord Bishop of Durham and the Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells to walk beside the Queen as she entered and exited the Abbey and to stand on either side of her through the entire coronation ritual, the claim of the Earl of Shrewsbury

Earl of Shrewsbury () is a hereditary title of nobility created twice in the Peerage of England. The second earldom dates to 1442. The holder of the Earldom of Shrewsbury also holds the title of Earl of Waterford (1446) in the Peerage of Ireland ...

in his capacity as Lord High Steward of Ireland

The office of Lord High Steward of Ireland is a hereditary position of Great Officer of State in the United Kingdom. Currently held by the Earl of Shrewsbury, it is sometimes referred to as the Hereditary Great Seneschal. While most of Ireland a ...

to carry a white staff. The legal claim of the Scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

s of Westminster School