Convict Transportation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of

/ref> It remained little used under Scots Law until the early 19th century. In Australia, a convict who had served part of his time might apply for a

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later termed the

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later termed the

"Asylum for Mankind": America, 1607–1800

pp. 124–127 For the ensuing decade, men were instead sentenced to hard labour and women were imprisoned. Finding alternative locations to send convicts was not easy, and the act was extended twice by the Criminal Law Act 1778 ( 18 Geo. 3. c. 62) and the Criminal Law Act 1779 ( 19 Geo. 3. c. 54). This resulted in a 1779 inquiry by a parliamentary committee on the entire subject of transportation and punishment; initially the

A short history of British colonial policy

pp. 262–269 (1897) In 1787, when transportation resumed to the chosen Australian colonies, the far greater distance added to the terrible experience of exile, and it was considered more severe than the methods of imprisonment employed for the previous decade. The

In 1787, the

In 1787, the

UK National archives

Convict life – State Library of NSW

Convict Transportation Registers

Convict Queenslanders

Forced migration History of immigration to Australia Convictism in Australia Punishments Crime in Australia Penal labour

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convicts ...

ed criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies

A penal colony or exile colony is a Human settlement, settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colony, colonial territory. Although the te ...

became their destination. While the prisoner

A prisoner, also known as an inmate or detainee, is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement or captivity in a prison or physical restraint. The term usually applies to one serving a Sentence (law), se ...

s may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did not have the resources to return home.

Origin and implementation

Banishment

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

or forced exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

from a polity or society has been used as a punishment since at least the 5th century BCE in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

. The practice of penal transportation reached its height in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Transportation removed the offender from society, mostly permanently, but was seen as more merciful than capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

. This method was used for criminals, debtors, military prisoners, and political prisoners.

Penal transportation was also used as a method of colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

. For example, from the earliest days of English colonial schemes, new settlements beyond the seas were seen as a way to alleviate domestic social problems of criminals and the poor as well as to increase the colonial labour force, for the overall benefit of the realm.

Great Britain and the British Empire

Initially based on theroyal prerogative of mercy

In the English and British tradition, the royal prerogative of mercy is one of the historic royal prerogatives of the British monarch, by which they can grant pardons (informally known as a royal pardon) to convicted persons. The royal prer ...

, and later under English law

English law is the common law list of national legal systems, legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly English criminal law, criminal law and Civil law (common law), civil law, each branch having its own Courts of England and Wales, ...

, transportation was an alternative sentence imposed for a felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that r ...

. It was typically imposed for offences for which death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

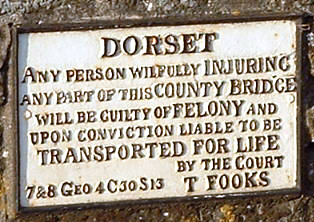

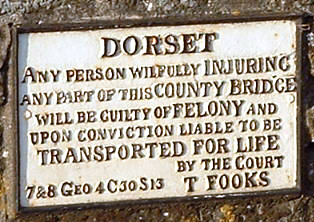

was deemed too severe. By 1670, as new felonies were defined, the option of being sentenced to transportation was allowed. Depending on the crime, the sentence was imposed for life or for a set period of years. If imposed for a period of years, the offender was permitted to return home after serving their time, but had to make their own way back. Many offenders thus stayed in the colony as free persons, and might obtain employment as jailers or other servants of the penal colony.

England transported an estimated 50,000 to 120,000 convicts and political prisoners, as well as prisoners of war from Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, to its overseas colonies in the Americas from the 1610s until early in the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

in 1776, when transportation to America was temporarily suspended by the Criminal Law Act 1776

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies becam ...

( 16 Geo. 3. c. 43). The practice was mandated in Scotland by the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1785.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts o ...

. c. 48), but was less used there than in England. Transportation on a large scale resumed with the departure of the First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

in 1787, and continued there until 1868.

Transportation was not used by Scotland before the Act of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

; following union, the Transportation Act 1717

The Piracy Act 1717 ( 4 Geo. 1. c. 11), sometimes called the Transportation Act 1717 or the Felons' Act 1717 (1718 in New Style), was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain that established a regulated, bonded system to transport crimina ...

( 4 Geo. 1. c. 11) specifically excluded its use in Scotland. Under the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1785.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts o ...

. c. 46) the Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a ...

specifically extended the usage of transportation to Scotland."An act for the effectual transportation of felons, and other offenders, in that part of Great Britain called Scotland, and to authorize the removal of prisoners in certain places."/ref> It remained little used under Scots Law until the early 19th century. In Australia, a convict who had served part of his time might apply for a

ticket of leave

A ticket of leave was a document of parole issued to convicts who had shown they could now be trusted with some freedoms. Originally the ticket was issued in United Kingdom, Britain and later adapted by the United States, Canada, and Ireland.

...

, permitting some prescribed freedoms

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and ...

. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family, and to contribute to the development of the colony.

Historical background

Trend towards more flexibility of sentencing

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later termed the

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later termed the Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to by this name in its own time; the name was g ...

. This was due to both the particularly large number of offences which were punishable by execution (usually by hanging), and to the limited choice of sentences available to judges for convicted criminals. With modifications to the traditional benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy ( Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

, which originally exempted only clergymen from the general criminal law, it developed into a legal fiction

A legal fiction is a construct used in the law where a thing is taken to be true, which is not in fact true, in order to achieve an outcome. Legal fictions can be employed by the courts or found in legislation.

Legal fictions are different from ...

by which many common offenders of "clergyable" offences were extended the privilege to avoid execution. Many offenders were pardoned as it was considered unreasonable to execute them for relatively minor offences, but under the rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, it was equally unreasonable for them to escape punishment entirely. With the development of colonies, transportation was introduced as an alternative punishment, although legally it was considered a condition of a pardon, rather than a sentence in itself. Convicts who represented a menace to the community were sent away to distant lands. A secondary aim was to discourage crime for fear of being transported. Transportation continued to be described as a public exhibition of the king's mercy. It was a solution to a real problem in the domestic penal system. There was also the hope that transported convicts could be rehabilitated and reformed by starting a new life in the colonies. In 1615, in the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

, a committee of the council had already obtained the power to choose from the prisoners those that deserved pardon and, consequently, transportation to the colonies. Convicts were chosen carefully: the Acts of the Privy Council showed that prisoners "for strength of bodie or other abilities shall be thought fit to be employed in foreign discoveries or other services beyond the Seas".

During the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

overcame the popular prejudice against subjecting Christians to slavery or selling them into foreign parts, and initiated group transportation of military and civilian prisoners. With the Restoration, the penal transportation system and the number of people subjected to it, started to change inexorably between 1660 and 1720, with transportation replacing the simple discharge of clergyable felons after branding the thumb. Alternatively, under the second act dealing with Moss-trooper brigands on the Scottish border, offenders had their benefit of clergy taken away, or otherwise at the judge's discretion, were to be transported to America, "there to remaine and not to returne". There were various influential agents of change: judges' discretionary powers influenced the law significantly, but the king's and Privy Council's opinions were decisive in granting a royal pardon from execution.

The system changed one step at a time: in February 1663, after that first experiment, a bill was proposed to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

to allow the transporting of felons, and was followed by another bill presented to the Lords to allow the transportation of criminals convicted of felony within clergy or petty larceny. These bills failed, but it was clear that change was needed. Transportation was not a sentence in itself, but could be arranged by indirect means. The reading test, crucial for the benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy ( Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

, was a fundamental feature of the penal system, but to prevent its abuse, this pardoning process was used more strictly. Prisoners were carefully selected for transportation based on information about their character and previous criminal record. It was arranged that they fail the reading test, but they were then reprieved and held in jail, without bail, to allow time for a royal pardon (subject to transportation) to be organised.

Transportation as a commercial transaction

Transportation became a business: merchants chose from among the prisoners on the basis of the demand for labour and their likely profits. They obtained a contract from the sheriffs, and after the voyage to the colonies they sold the convicts asindentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as paymen ...

s. The payment they received also covered the jail fees, the fees for granting the pardon, the clerk's fees, and everything necessary to authorise the transportation. These arrangements for transportation continued until the end of the 17th century and beyond, but they diminished in 1670 due to certain complications. The colonial opposition was one of the main obstacles: colonies were unwilling to collaborate in accepting prisoners: the convicts represented a danger to the colony and were unwelcome. Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

enacted laws to prohibit transportation in 1670, and the king was persuaded to respect these.

The penal system was also influenced by economics: the profits obtained from convicts' labour boosted the economy of the colonies and, consequently, of England. Nevertheless, it could be argued that transportation was economically deleterious because the aim was to enlarge population, not diminish it; but the character of an individual convict was likely to harm the economy. King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

(1688–1697) (part of the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

) and the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

(1701–14) adversely affected merchant shipping and hence transportation. In the post-war period there was more crime and hence potentially more executions, and something needed to be done. In the reigns of Queen Anne (1702–14) and George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

(1714–27), transportation was not easily arranged, but imprisonment was not considered enough to punish hardened criminals or those who had committed capital offences, so transportation was the preferred punishment.

Transportation Act 1717

There were several obstacles to the use of transportation. In 1706 the reading test for claiming benefit of clergy was abolished ( 6 Ann. c. 9). This allowed judges to sentence "clergyable" offenders to aworkhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

or a house of correction. But the punishments that then applied were not enough of a disincentive to commit crime: another solution was needed. The Transportation Act was introduced into the House of Commons in 1717 under the Whig government. It legitimised transportation as a direct sentence, thus simplifying the penal process.

Non-capital convicts (clergyable felon

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that ...

s usually destined for branding on the thumb, and petty larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Engla ...

convicts usually destined for public whipping) were directly sentenced to transportation to the American colonies for seven years. A sentence of fourteen years was imposed on prisoners guilty of capital offences pardoned by the king. Returning from the colonies before the stated period was a capital offence. The bill was introduced by William Thomson, the Solicitor General

A solicitor general is a government official who serves as the chief representative of the government in courtroom proceedings. In systems based on the English common law that have an attorney general or equivalent position, the solicitor general ...

, who was "the architect of the transportation policy". Thomson, a supporter of the Whigs, was Recorder Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a newsp ...

of London and became a judge in 1729. He was a prominent sentencing officer at the Old Bailey and the man who gave important information about capital offenders to the cabinet.

One reason for the success of this Act was that transportation was financially costly. The system of sponsorship by merchants had to be improved. Initially the government rejected Thomson's proposal to pay merchants to transport convicts, but three months after the first transportation sentences were pronounced at the Old Bailey, his suggestion was proposed again, and the Treasury contracted Jonathan Forward

Jonathan Forward (1680–1760) was a London merchant primarily responsible for convict transportation to the American colonies from 1718 to 1739. In accordance with the Transportation Act 1717, Forward was contracted to transport felons from Ne ...

, a London merchant, for the transportation to the colonies. The business was entrusted to Forward in 1718: for each prisoner transported overseas, he was paid £3 (), rising to £5 in 1727 (). The Treasury also paid for the transportation of prisoners from the Home Counties.

The "Felons' Act" (as the Transportation Act was called) was printed and distributed in 1718, and in April twenty-seven men and women were sentenced to transportation. The Act led to significant changes: both petty and grand larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Eng ...

were punished by transportation (seven years), and the sentence for any non-capital offence was at the judge's discretion. In 1723 an Act was presented in Virginia to discourage transportation by establishing complex rules for the reception of prisoners, but the reluctance of colonies did not stop transportation.

In a few cases before 1734, the court changed sentences of transportation to sentences of branding on the thumb or whipping, by convicting the accused for lesser crimes than those of which they were accused. This manipulation phase came to an end in 1734. With the exception of those years, the Transportation Act led to a decrease in whipping of convicts, thus avoiding potentially inflammatory public displays. Clergyable discharge continued to be used when the accused could not be transported for reasons of age or infirmity.

Women and children

Penal transportation was not limited to men or even to adults. Men, women, and children were sentenced to transportation, but its implementation varied by sex and age. From 1660 to 1670, highway robbery,burglary

Burglary, also called breaking and entering (B&E) or housebreaking, is a property crime involving the illegal entry into a building or other area without permission, typically with the intention of committing a further criminal offence. Usually ...

, and horse theft

Horse theft is the crime of stealing horses. A person engaged in stealing horses is known as a horse thief. Historically, punishments were often severe for horse theft, with several cultures pronouncing the sentence of death upon actual or pre ...

were the offences most often punishable with transportation for men. In those years, five of the nine women who were transported after being sentenced to death were guilty of simple larceny, an offence for which benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy ( Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

was not available for women until 1692. Also, merchants preferred young and able-bodied men for whom there was a demand in the colonies.

All these factors meant that most women and children were simply left in jail. Some magistrates supported a proposal to release women who could not be transported, but this solution was considered absurd: this caused the Lords Justices to order that no distinction be made between men and women. Women were sent to the Leeward Islands

The Leeward Islands () are a group of islands situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean. Starting with the Virgin Islands east of Puerto Rico, they extend southeast to Guadeloupe and its dependencies. In Engl ...

, the only colony that accepted them, and the government had to pay to send them overseas. In 1696 Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

refused to welcome a group of prisoners because most of them were women; Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

similarly accepted convicts but not "women, children nor other infirm persons".

Thanks to transportation, the number of men whipped and released diminished, but whipping and discharge were chosen more often for women. The reverse was true when women were sentenced for a capital offence, but actually served a lesser sentence due to a manipulation of the penal system: one advantage of this sentence was that they could be discharged thanks to benefit of clergy while men were whipped. Women with young children were also supported since transportation unavoidably separated them. The facts and numbers revealed how transportation was less frequently applied to women and children because they were usually guilty of minor crimes and they were considered a minimal threat to the community.

The end of transportation

The outbreak of theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

(1775–1783) halted transportation to America. Parliament claimed that "the transportation of convicts to his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America ... is found to be attended with various inconveniences, particularly by depriving this kingdom of many subjects whose labour might be useful to the community, and who, by proper care and correction, might be reclaimed from their evil course"; they then passed the Criminal Law Act 1776 ( 16 Geo. 3. c. 43) "An act to authorize ... the punishment by hard labour of offenders who, for certain crimes, are or shall become liable to be transported to any of his Majesty's colonies and plantations."Marilyn C. Baseler"Asylum for Mankind": America, 1607–1800

pp. 124–127 For the ensuing decade, men were instead sentenced to hard labour and women were imprisoned. Finding alternative locations to send convicts was not easy, and the act was extended twice by the Criminal Law Act 1778 ( 18 Geo. 3. c. 62) and the Criminal Law Act 1779 ( 19 Geo. 3. c. 54). This resulted in a 1779 inquiry by a parliamentary committee on the entire subject of transportation and punishment; initially the

Penitentiary Act 1779

The Penitentiary Act 1779 ( 19 Geo. 3. c. 74) was a act of the Parliament of Great Britain passed in 1779 which introduced a policy of state prisons for the first time. The act was drafted by the prison reformer John Howard and the jurist Will ...

was passed, introducing a policy of state prisons as a measure to reform the system of overcrowded prison hulk

A prison ship, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoner of war, prisoners of war or civilian internees. Some prison ships were hulk (ship type), hulked. W ...

s that had developed, but no prisons were ever built as a result of the act. The Transportation, etc. Act 1784 ( 24 Geo. 3. Sess. 2. c. 56) and the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1785.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts o ...

. c. 46) also resulted to help alleviate overcrowding. Both acts empowered the Crown to appoint certain places within his dominions, or outside them, as the destination for transported criminals; the acts would move convicts around the country as needed for labour, or where they could be utilized and accommodated.

The overcrowding situation and the resumption of transportation would be initially resolved by Orders in Council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

on 6 December 1786, by the decision to establish a penal colony in New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, on land previously claimed for Britain in 1770, but as yet not settled by Britain or any other European power. The British policy toward Australia, specifically for use as a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer ...

, within their overall plans to populate and colonise the continent, would differentiate it from America, where the use of convicts was only a minor adjunct to its overall policy.Hugh Edward EgertonA short history of British colonial policy

pp. 262–269 (1897) In 1787, when transportation resumed to the chosen Australian colonies, the far greater distance added to the terrible experience of exile, and it was considered more severe than the methods of imprisonment employed for the previous decade. The

Transportation Act 1790

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelines, an ...

( 30 Geo. 3. c. 47) officially enacted the previous orders in council into law, stating "his Majesty hath declared and appointed... that the eastern coast of New South Wales, and the islands thereunto adjacent, should be the place or places beyond the seas to which certain felons, and other offenders, should be conveyed and transported ... or other places". The act also gave "authority to remit or shorten the time or term" of the sentence "in cases where it shall appear that such felons, or other offenders, are proper objects of the royal mercy".

At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation for life became the maximum penalty for several offences which had previously been punishable by death. With complaints starting in the 1830s, sentences of transportation became less common in 1840 since the system was perceived to be a failure: crime continued at high levels, people were not dissuaded from committing felonies, and the conditions of convicts in the colonies were inhumane. Although a concerted programme of prison building ensued, the Short Titles Act 1896

The Short Titles Act 1896 (59 & 60 Vict. c. 14) is an Acts of Parliament in the United Kingdom, act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It replaces the Short Titles Act 1892 (55 & 56 Vict. c. 10).

This act was retained for the Republic of I ...

lists seven other laws relating to penal transportation in the first half of the 19th century.

The system of criminal punishment by transportation, as it had developed over nearly 150 years, was officially ended in Britain in the 1850s, when that sentence was substituted by imprisonment with penal servitude

Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included inv ...

, and intended to punish. The Penal Servitude Act 1853

Penal Servitude Act is a stock short title which was used in the United Kingdom for legislation relating to penal servitude. The abolition of penal servitude has rendered this short title obsolete in that country.

List

:The Penal Servitude Act ...

( 16 & 17 Vict. c. 99), long titled "An Act to substitute, in certain Cases, other Punishment in lieu of Transportation," enacted that with judicial discretion, lesser felonies, those subject to transportation for less than 14 years, could be sentenced to imprisonment with labour for a specific term. To provide confinement facilities, the general change in sentencing was passed in conjunction with the Convict Prisons Act 1853

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convicts ...

( 16 & 17 Vict. c. 121), long titled "An Act for providing Places of Confinement in England or Wales for Female Offenders under Sentence or Order of Transportation." The Penal Servitude Act 1857

Penal is a town in south Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. It lies south of San Fernando, Princes Town, and Debe, and north of Moruga, Morne Diablo and Siparia. Penal is noted as a heartland of Hindu and Indo-Trinidadian culture.

History

Up t ...

( 20 & 21 Vict. c. 3) ended the sentence of transportation in virtually all cases, with the terms of sentence initially being of the same duration as transportation. While transport was greatly reduced following enactment of the 1857 act, the last convicts sentenced to transportation arrived in Western Australia in 1868. During the 80 years of its use to Australia, the number of transported convicts totalled about 162,000 men and women. Over time the alternative terms of imprisonment would be somewhat reduced from their terms of transportation.

Transportation locations

Transportation to North America

From the early 1600s until theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

of 1776, the British colonies in North America received transported British criminals. Destinations were the island colonies of the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

and the mainland colonies that became the United States of America.

In the 17th century transportation was carried out at the expense of the convicts or the shipowners. The Transportation Act 1717

The Piracy Act 1717 ( 4 Geo. 1. c. 11), sometimes called the Transportation Act 1717 or the Felons' Act 1717 (1718 in New Style), was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain that established a regulated, bonded system to transport crimina ...

allowed courts to sentence convicts to seven years' transportation to America. In 1720, an extension authorized payments by the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

to merchants contracted to take the convicts to America. The Transportation Act made returning from transportation a capital offence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

. The number of convicts transported to North America is not verified: John Dunmore Lang

John Dunmore Lang (25 August 1799 – 8 August 1878) was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian rep ...

has estimated 50,000, and Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his historical fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler' ...

has proposed 120,000. Maryland received a larger felon quota than any other province. Many prisoners were taken in battle from Ireland or Scotland and sold into indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an " indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or s ...

, usually for a number of years. The American Revolution brought transportation to the North American mainland to an end. The remaining British colonies (in what is now Canada) were regarded as unsuitable for various reasons, including the possibility that transportation might increase dissatisfaction with British rule among settlers and/or the possibility of annexation by the United States – as well as the ease with which prisoners could escape across the border.

After the termination of transportation to North America, British prisons became overcrowded, and dilapidated ships moored in various ports were pressed into service as floating gaols known as "hulks". Following an 18th-century experiment in transporting convicted prisoners to Cape Coast Castle

Cape Coast Castle () is one of about forty slave fort, "slave castles", or large commercial forts, built on the Gold Coast (region), Gold Coast of West Africa (now Ghana) by European traders. It was originally a Portuguese "feitoria" or Factory ( ...

(modern Ghana) and the Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

(Senegal) in West Africa, British authorities turned their attention to New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

(in what would become Australia).

From the 1820s until the 1860s, convicts were sent to the Imperial fortress

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, Lord Salisbury described Malta, Gibraltar, Bermuda, and Halifax as Imperial fortresses at the 1887 Colonial Conference, though by that point they had been so designated for decades. Later histor ...

colony of Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

(part of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

) to work on the construction of the Royal Naval Dockyard and other defence works, including at the East End of the archipelago, where they were accommodated aboard the hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk ...

of HMS ''Thames'' at an area still known as " Convict Bay", at St. George's town.

Transportation to Australia

In 1787, the

In 1787, the First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

, a group of convict ship

A convict ship was any ship engaged on a voyage to carry convicted felons under sentence of penal transportation from their place of conviction to their place of exile.

Description

A convict ship, as used to convey convicts to the British colo ...

s departed from England to establish the first colonial settlement in Australia, as a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer ...

. The First Fleet included boats containing food and animals from London. The ships and boats of the fleet would explore the coast of Australia by sailing all around it looking for suitable farming land and resources. The fleet arrived at Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal language, Dharawal: ''Kamay'') is an open oceanic embayment, located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point a ...

, Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

on 18 January 1788, then moved to Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove (Eora language, Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central ...

(modern-day Circular Quay

Circular Quay is a harbour, former working port and now international passenger shipping terminal, public piazza and tourism precinct, heritage area, and transport node located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, on the northern edge of the ...

) and established the first permanent European settlement in Australia. This marked the beginning of the European colonisation of Australia.

Violent conflict on the Australian frontier between indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

and the colonists began only months after the First Fleet landed, lasting over a century. Convicts forced to work in the bush

"The bush" is a term mostly used in the English vernacular of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, where it is largely synonymous with hinterlands or backwoods. The fauna and flora contained within the bush is typically native to the regi ...

on the frontier were sometimes the victims of indigenous attacks, while convicts and ex-convicts also attacked indigenous people in some instances, such as the Myall Creek Massacre

The Myall Creek massacre was the killing of at least 28 unarmed Aboriginal people in the Colony of New South Wales by eight colonists on 10 June 1838 at the Myall Creek in the north of the colony. Seven perpetrators were convicted of murder ...

. In the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars

The Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars (1794–1816) were a series of conflicts where British forces, including armed settlers and detachments of the British Army in Australia, fought against Indigenous clans inhabiting the Hawkesbury River region an ...

, a group of Irish convicts joined the Aboriginal coalition of Eora

The Eora (; also ''Yura'') are an Aboriginal Australian people of New South Wales. Eora is the name given by the earliest European settlers to a group of Aboriginal people belonging to the clans along the coastal area of what is now known as ...

, Gandangara

The Gandangara people, also spelled Gundungara, Gandangarra, Gundungurra and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people in south-eastern New South Wales, Australia. Their traditional lands include present day Goulburn, Wollondilly Sh ...

, Dharug

The Dharug or Darug people, are a nation of Aboriginal Australian clans, who share ties of kinship, country and culture. In pre-colonial times, they lived as hunters in the region of current day Sydney. The Darug speak one of two dialects o ...

and Tharawal

The Tharawal people and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people, identified by the Yuin language. Traditionally, they lived as hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans with ties of kinship, scattered along the coasta ...

nations in their fight against the colonists.

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island ( , ; ) is an States and territories of Australia, external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head, New South Wales, Evans Head and a ...

, east of the Australian mainland, was a convict penal settlement from 1788 to 1794, and again from 1824 to 1847. In 1803, Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

(modern-day Tasmania) was also settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (modern Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

, Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

) in 1824. The other Australian colonies

The states and territories are the national subdivisions and second level of government of Australia. The states are partially sovereignty, sovereign, administrative divisions that are autonomous administrative division, self-governing polity, ...

were established as "free settlements", as non-convict colonies were known. However, the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just ''Swan River'', was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, an ...

(Western Australia) accepted transportation from England and Ireland in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage

In economics, a shortage or excess demand is a situation in which the demand for a product or service exceeds its supply in a market. It is the opposite of an excess supply ( surplus).

Definitions

In a perfect market (one that matches a s ...

.

Two penal settlements were established near modern-day Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

but both were abandoned shortly after. Later, a free settlement was established and this settlement later accepted some convict transportation.

Until the massive influx of immigrants during the Australian gold rushes

During the Australian gold rushes, starting in 1851, significant numbers of workers moved from elsewhere in History of Australia, Australia and overseas to where gold had been discovered. Gold had been found several times before, but the Colo ...

of the 1850s, free settlers had been outnumbered by penal convicts and their descendants. However, compared to the British American colonies

The British colonization of the Americas is the history of establishment of control, settlement, and colonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland, and, after 1707, Great Britain. Colonization efforts began in the late 16 ...

, Australia received a larger number of convicts.

Convicts were generally treated harshly, forced to work against their will, often doing hard physical labour and dangerous jobs. In some cases they were cuffed and chained in work gangs. The majority of convicts were men, although a significant portion were women. Some were as young as 10 when convicted and transported to Australia. Most were guilty of relatively minor crimes like theft of food/clothes/small items, but some were convicted of serious crimes like rape or murder. Convict status was not inherited by children, and convicts were generally freed after serving their sentence, although many died during transportation or during their sentence.

Convict assignment

Convict assignment was the practice used in many penal colonies of assigning convicts to work for private individuals. Contemporary abolitionists characterised the practice as virtual slavery, and some, but by no means all, latter-day historians h ...

(sending convicts to work for private individuals) occurred in all penal colonies aside from Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

, and can be compared with the practice of convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor that was practiced historically in the Southern United States before it was formally abolished during the 20th century. Under this system, private individuals and corporations could lease la ...

in the United States.

Transportation from Great Britain and Ireland ended at different times in different colonies, with the last being in 1868, although it had become uncommon several years earlier thanks to the loosening of laws in Britain, changing sentiment in Australia, and groups such as the Anti-Transportation League.

In 2015, an estimated 20% of the Australian population had convict ancestry. In 2013, an estimated 30% of the Australian population (about 7 million) had Irish ancestry – the highest percentage outside of Ireland – thanks partially to historical convict transportation.

Transportation from British India

InBritish India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

– including the province of Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

(now Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

) and the port of Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

(now part of Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

) – Indian independence activists

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Associated with India

* of or related to India

** Indian people

** Indian diaspora

** Languages of India

** Indian English, a dialect of the English language

** Indian cuisine

Associated with indigenous peoples o ...

were penally transported to the Andaman Islands

The Andaman Islands () are an archipelago, made up of 200 islands, in the northeastern Indian Ocean about southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a mari ...

. A penal colony was established there in 1857 with prisoners from the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

. As the Indian independence movement swelled, so did the number of prisoners who were penally transported.

The Cellular Jail

The Cellular Jail, also known as Kālā Pānī (), was a British colonial prison in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The prison was used by the colonial government of India for the purpose of exiling criminals and political prisoners. Many ...

in Port Blair

Port Blair (), officially named Sri Vijaya Puram, is the capital city of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a union territory of India in the Bay of Bengal. It is also the local administrative sub-division (''tehsil'') of the islands, the headqu ...

, South Andaman Island

South Andaman Island is the southernmost island of the Great Andaman and is home to the majority of the population of the Andaman Islands.

It belongs to the South Andaman administrative district, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman a ...

, also called Kālā Pānī or Kalapani (Hindi for black waters), was constructed between 1896 and 1906 as a high-security prison with 698 individual cells for solitary confinement

Solitary confinement (also shortened to solitary) is a form of imprisonment in which an incarcerated person lives in a single Prison cell, cell with little or no contact with other people. It is a punitive tool used within the prison system to ...

. Surviving prisoners were repatriated in 1937. The penal settlement was shut down in 1945. An estimated 80,000 political prisoners were transported to the Cellular Jail which became known for its harsh conditions, including forced labor; prisoners who went on hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

s were frequently force-fed.

France

France transported convicts toDevil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953, in the Salvation Islan ...

and New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

in the 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries. Devil's Island, a French penal colony in Guiana

The Guianas, also spelled Guyanas or Guayanas, are a geographical region in north-eastern South America. Strictly, the term refers to the three Guianas: Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, formerly British, Dutch, and French Guiana respectiv ...

, was used for transportation from 1852 to 1953. New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

became a French penal colony from the 1860s until the end of the transportations in 1897; about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners (most notably Communards

The Communards () were members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. After the suppression of the Commune by the French Army in May 1871, 43,000 Communards we ...

) were sent to New Caledonia.

Henri Charrière

Henri Charrière (; 16 November 1906 – 29 July 1973) was a French writer, convicted of murder in 1931 by the French courts and pardoned in 1970. He wrote the 1969 novel '' Papillon'', a memoir of his incarceration in and escape from a p ...

(16 November 1906 – 29 July 1973) was a French writer, convicted in 1931 as a murderer by the French courts and pardoned in 1970. He wrote the novel '' Papillon'', a semi-autobiographical novel of his incarceration in and escape from a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer ...

in French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

.

The most significant individual transported prisoner is probably French army officer Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the Fre ...

, wrongly convicted of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

in a trial in 1894, held in an atmosphere of antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. He was sent to Devil's Island. The case became a cause célèbre

A ( , ; pl. ''causes célèbres'', pronounced like the singular) is an issue or incident arousing widespread controversy, outside campaigning, and heated public debate. The term is sometimes used positively for celebrated legal cases for th ...

known as the Dreyfus Affair, and Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906.

Soviet Union

Unlike normal penal transportation, many Soviet people were transported as criminals in forms ofdeportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or is under sen ...

being proclaimed as enemies of the people in a form of collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group or whole community for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member or some members of that group or area, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends a ...

. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Soviet Union transported up to 1.9 million people from its western republics to Siberia and the Central Asian republics of the Union. Most were persons accused of treasonous collaboration with Nazi Germany, or of Anti-Soviet rebellion. Following the death of Joseph Stalin

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose shor ...

, most of them were rehabilitated. Populations targeted included Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (, ; ) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov and close to Ukraine nearer to the south.

Recruited as immigrants to Russia in the ...

, Chechens

The Chechens ( ; , , Old Chechen: Нахчой, ''Naxçoy''), historically also known as ''Kistin, Kisti'' and ''Durdzuks'', are a Northeast Caucasian languages, Northeast Caucasian ethnic group of the Nakh peoples native to the North Caucasus. ...

, and Caucasian Turkic populations. The transportations had a twofold objective: to remove potential liabilities from the warfront, and to provide human capital for the settlement and industrialization of the largely underpopulated eastern regions. The policy continued until February 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

in his speech, "On the Personality Cult and Its Consequences

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" () was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 Febr ...

", condemned the transportation as a violation of Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

principles. Whilst the policy itself was rescinded, the transported populations did not begin to return to their original metropoles until after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991.

Modern Russia

The Russian government today still sends their convicts andpolitical prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s to prisons that echo those of the Soviet Union. The journey to these prisons and labor camps is long and arduous.

In many cases, the Russian penitentiary system utilizes special cars. These cars contain five large compartments and three smaller compartments. The larger car is 3.5 meters squared. The size of the larger car is approximately the same as normal Russian railcar spaces. The larger compartments have six and a half individual sleeping spaces. There are three bunks on each wall and a half bunk that goes between the two middle bunks. The half bunk is not full sized and prevents prisoners from standing up in the car. For food, prisoners are given dehydrated food three times a day and limited amounts of hot water to rehydrate their meals. Bedding is not provided nor are mattresses. During transit, prisoners do not have access to proper medical treatment. The medication that a prisoner would normally take is carried by guards. Transportation routes are often cyclical and prisoners do not know where they are going. This sense of unease and unknowing has been known to increase feelings of isolation. Prisoners have very limited access to toilets while on the trains, about every five to six hours. While the trains are stationary they have no access at all. This can be very difficult as trains often are kept at stations or train depot

A train station, railroad station, or railway station is a Rail transport, railway facility where trains stop to load or unload passenger train, passengers, freight rail transport, freight, or both. It generally consists of at least one railwa ...

s for extended periods of time.

While traveling to and from train stations, prisoners are transported in vans. While the time spent in vans is usually shorter than the time spent in trains, the conditions are still quite bad. The vans normally have two larger compartments that can fit 10 prisoners. Within the compartments there is a smaller compartment that is used to keep "at risk" prisoners safe. The smaller compartment is known as a stakan and is smaller than 0.5 meter squared.

In addition to poor transit conditions, prisoners are severely limited in their communication with the outside world. Prisoners are denied the right to communicate with their lawyers and families. This can be difficult for their families because they do not know where the prisoner is or what has happened to them.

In popular culture

Performing arts

Penal transportation is a feature of many broadsides, a new type of folk song that developed in eighteenth-century England. A number of these transportation ballads have been collected from traditional singers. Examples include "Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

," " The Black Velvet Band," " The Peeler and the Goat", and "The Fields of Athenry

"The Fields of Athenry" is a song written in 1979 by Pete St John in the style of an Irish folk ballad. Set during the Great Famine of the 1840s, the lyrics feature a fictional man from near Athenry in County Galway, who stole food for his ...

."

Timberlake Wertenbaker

Timberlake Wertenbaker is a British-based playwright, screenplay writer, and translator who has written plays for the Royal Court, the Royal Shakespeare Company and others. She has been described in ''The Washington Post'' as "the doyenne of po ...

's play ''Our Country's Good

''Our Country's Good'' is a 1988 play written by British playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker, adapted from the Thomas Keneally novel '' The Playmaker''. The story concerns a group of Royal Marines and convicts in a penal colony in New South Wales ...

'' is set in 1780s in the first Australian penal colony. In the 1988 play, convicts

A convict is "a person found Guilt (law), guilty of a crime and Sentence (law), sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a commo ...

and Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

arrive aboard a First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

ship and settle New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

. Convicts and guards interact as they rehearse a theatre production

Stagecraft is a technical aspect of theatrical, film, and video production. It includes constructing and rigging scenery; hanging and focusing of lighting; design and procurement of costumes; make-up; stage management; audio engineering; and p ...

, which the governor had suggested as an alternate form of entertainment instead of watching public hangings.

Literature

One of the key characters inCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

's novel ''Great Expectations

''Great Expectations'' is the thirteenth novel by English author Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. The novel is a bildungsroman and depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip. It is Dickens' second novel, after ''Dav ...

'' is an escaped convict, Abel Magwitch

Abel Magwitch is a major fictional character from Charles Dickens' 1861 novel ''Great Expectations''.

Synopsis

Charles Dickens set his story in the early 19th century, setting his character Abel Magwitch to meet a man called Compeyson at the Epso ...

. Pip helps him in the opening pages of the novel. Magwitch, who had been apprehended shortly after the young Pip had helped him, was thereafter sentenced to transportation for life to New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. While so exiled, he earned the fortune that he later would use to help Pip. Further, it was Magwitch's desire to see the "gentleman" that Pip had become that motivated him to illegally return to England, which ultimately led to his arrest and death. ''Great Expectations'' was published in serial form in 1860–1861. In Dickens's novel ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', is the second novel by English author Charles Dickens. It was originally published as a serial from 1837 to 1839 and as a three-volume book in 1838. The story follows the titular orphan, who, ...

'', the Artful Dodger

Jack Dawkins, better known as the Artful Dodger, is a character in Charles Dickens's 1838 novel ''Oliver Twist''. The Dodger is a pickpocket and his nickname refers to his skill and cunning in that occupation. In the novel, he is the leader of th ...

is convicted and transported to Australia.

''My Transportation for Life'', Indian freedom fighter Veer Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (28 May 1883 – 26 February 1966 ), was an Indian politician, activist and writer. Savarkar developed the Hindu nationalist political ideology of Hindutva while confined at Ratnagiri in 1922. The prefix "Veer" (mea ...

's memoir of his imprisonment, is set in the British Cellular Jail

The Cellular Jail, also known as Kālā Pānī (), was a British colonial prison in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The prison was used by the colonial government of India for the purpose of exiling criminals and political prisoners. Many ...

in the Andaman Islands

The Andaman Islands () are an archipelago, made up of 200 islands, in the northeastern Indian Ocean about southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a mari ...

. Savarkar was imprisoned there from 1911 to 1921.

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a novelist and writer from Prague who was Jewish, Austrian, and Czech and wrote in German. He is widely regarded as a major figure of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of Litera ...

's story "In der Strafkolonie" ("In the Penal Colony

"In the Penal Colony" ("") (also translated as "In the Penal Settlement") is a short story by Franz Kafka written in German in October 1914, revised in November 1918, and first published in October 1919. As in some of Kafka's other writings, the ...

"), published in 1919, was set in an unidentified penal settlement where condemned prisoners were executed by a brutal machine. The work was later adapted for several other media, including an opera by Philip Glass

Philip Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century. Glass's work has been associated with minimal music, minimalism, being built up fr ...

.

The novel '' Papillon'' tells the story of Henri Charrière

Henri Charrière (; 16 November 1906 – 29 July 1973) was a French writer, convicted of murder in 1931 by the French courts and pardoned in 1970. He wrote the 1969 novel '' Papillon'', a memoir of his incarceration in and escape from a p ...