Conscience People on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A conscience is a

A conscience is a

Retrieved 31 December 2013. and been the subject of many prominent examples of literature, music and film.

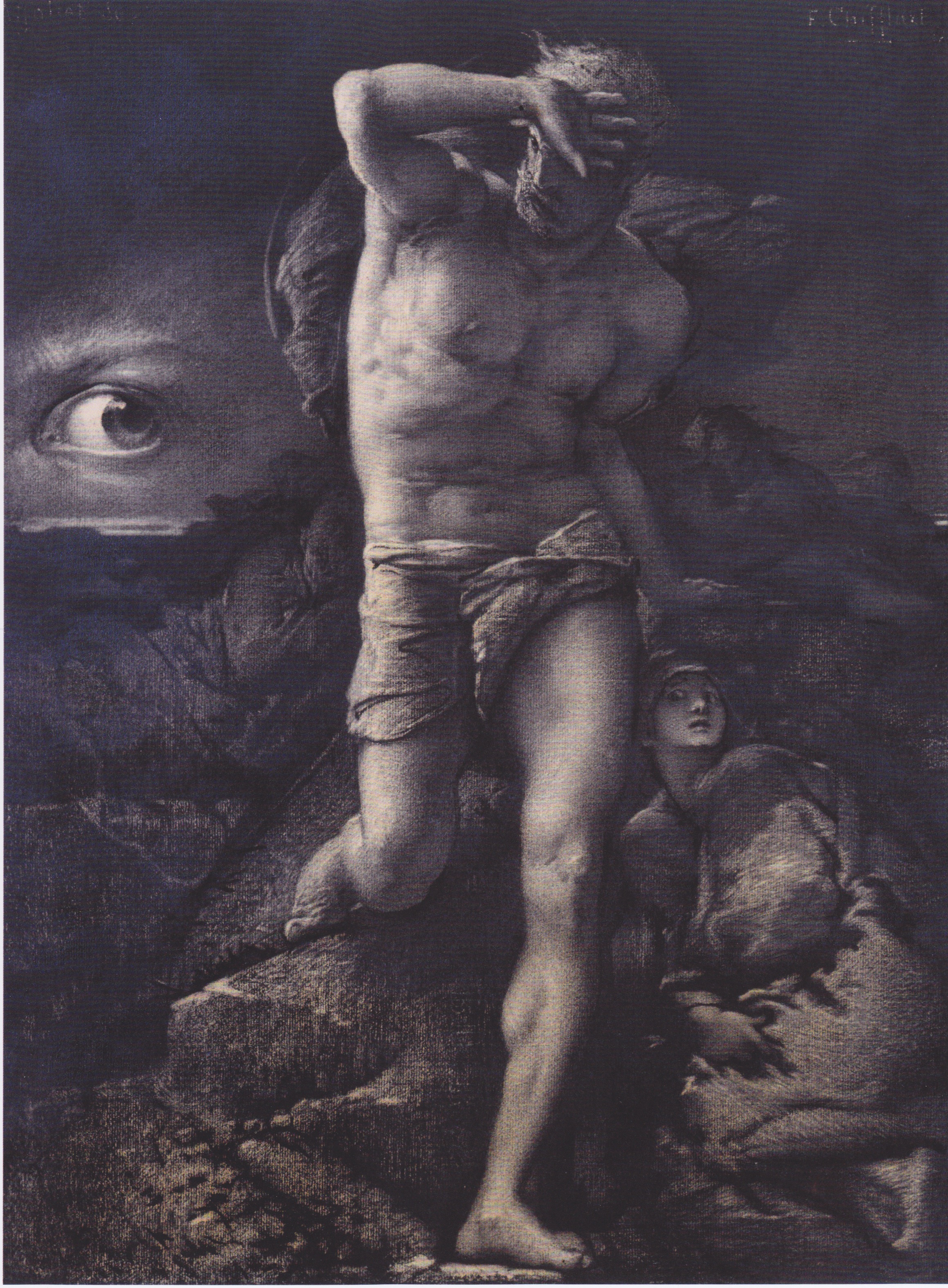

In the literary traditions of the

In the literary traditions of the  Conscience also features prominently in

Conscience also features prominently in  In the

In the  This dilemma of obedience in conscience to divine or state law, was demonstrated dramatically in

This dilemma of obedience in conscience to divine or state law, was demonstrated dramatically in

The secular approach to conscience includes

The secular approach to conscience includes

Michel Glautier argues that conscience is one of the instincts and drives which enable people to form societies: groups of humans without these drives or in whom they are insufficient cannot form societies and do not reproduce their kind as successfully as those that do.

Michel Glautier argues that conscience is one of the instincts and drives which enable people to form societies: groups of humans without these drives or in whom they are insufficient cannot form societies and do not reproduce their kind as successfully as those that do.

Some medieval Christian

Some medieval Christian  In the 13th century,

In the 13th century,

Other philosophers expressed a more sceptical and pragmatic view of the operation of "conscience" in society.

John Locke in his ''Essays on the Law of Nature'' argued that the widespread fact of human conscience allowed a philosopher to infer the necessary existence of objective moral laws that occasionally might contradict those of the state. Locke highlighted the metaethics problem of whether accepting a statement like "follow your ''conscience''" supports subject (philosophy), subjectivist or objectivity (philosophy), objectivist conceptions of conscience as a guide in concrete morality, or as a spontaneous revelation of eternal and immutable principles to the individual: "if conscience be a proof of innate principles, contraries may be innate principles; since some men with the same bent of conscience prosecute what others avoid." Thomas Hobbes likewise pragmatically noted that opinions formed on the basis of ''conscience'' with full and honest conviction, nevertheless should always be accepted with humility as potentially erroneous and not necessarily indicating absolute knowledge or truth. William Godwin expressed the view that ''conscience'' was a memorable consequence of the "perception by men of every creed when the descend into the scene of busy life" that they possess

As

Other philosophers expressed a more sceptical and pragmatic view of the operation of "conscience" in society.

John Locke in his ''Essays on the Law of Nature'' argued that the widespread fact of human conscience allowed a philosopher to infer the necessary existence of objective moral laws that occasionally might contradict those of the state. Locke highlighted the metaethics problem of whether accepting a statement like "follow your ''conscience''" supports subject (philosophy), subjectivist or objectivity (philosophy), objectivist conceptions of conscience as a guide in concrete morality, or as a spontaneous revelation of eternal and immutable principles to the individual: "if conscience be a proof of innate principles, contraries may be innate principles; since some men with the same bent of conscience prosecute what others avoid." Thomas Hobbes likewise pragmatically noted that opinions formed on the basis of ''conscience'' with full and honest conviction, nevertheless should always be accepted with humility as potentially erroneous and not necessarily indicating absolute knowledge or truth. William Godwin expressed the view that ''conscience'' was a memorable consequence of the "perception by men of every creed when the descend into the scene of busy life" that they possess

As  Albert Einstein, as a self-professed adherent of humanism and rationalism, likewise viewed an enlightened religious person as one whose ''conscience'' reflects that he "has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value."

Einstein often referred to the "inner voice" as a source of both moral and physical knowledge: "Quantum mechanics is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings one closer to the secrets of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice."

Simone Weil who fought for the French resistance (the Maquis (World War II), Maquis) argued in her final book ''The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind'' that for society to become more just and protective of liberty, obligations should take precedence over rights in moral and political philosophy and a spiritual awakening should occur in the ''conscience'' of most citizens, so that social obligations are viewed as fundamentally having a transcendent origin and a beneficent impact on human character when fulfilled. Simone Weil also in that work provided a psychological explanation for the mental peace associated with a ''good conscience'': "the liberty of men of goodwill, though limited in the sphere of action, is complete in that of conscience. For, having incorporated the rules into their own being, the prohibited possibilities no longer present themselves to the mind, and have not to be rejected."

Alternatives to such

Albert Einstein, as a self-professed adherent of humanism and rationalism, likewise viewed an enlightened religious person as one whose ''conscience'' reflects that he "has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value."

Einstein often referred to the "inner voice" as a source of both moral and physical knowledge: "Quantum mechanics is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings one closer to the secrets of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice."

Simone Weil who fought for the French resistance (the Maquis (World War II), Maquis) argued in her final book ''The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind'' that for society to become more just and protective of liberty, obligations should take precedence over rights in moral and political philosophy and a spiritual awakening should occur in the ''conscience'' of most citizens, so that social obligations are viewed as fundamentally having a transcendent origin and a beneficent impact on human character when fulfilled. Simone Weil also in that work provided a psychological explanation for the mental peace associated with a ''good conscience'': "the liberty of men of goodwill, though limited in the sphere of action, is complete in that of conscience. For, having incorporated the rules into their own being, the prohibited possibilities no longer present themselves to the mind, and have not to be rejected."

Alternatives to such  The philosopher Peter Singer considers that usually when we describe an action as conscientious in the critical sense we do so in order to deny either that the relevant agent was motivated by selfish desires, like greed or ambition, or that he acted on whim or impulse.

Moral anti-realists debate whether the moral facts necessary to activate conscience supervenience, supervene on natural facts with ''Empirical evidence, a posteriori'' necessity; or arise ''a priori'' because moral facts have a primary intension and naturally identical worlds may be presumed morally identical. It has also been argued that there is a measure of moral luck in how circumstances create the obstacles which ''conscience'' must overcome to apply moral principles or human rights and that with the benefit of enforceable property rights and the rule of law, access to universal health care plus the absence of high adult and infant mortality from conditions such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and famine, people in relatively prosperous developed countries have been spared pangs of ''conscience'' associated with the physical necessity to steal scraps of food, bribe tax inspectors or police officers, and commit murder in guerrilla wars against corrupt government forces or rebel armies. Roger Scruton has claimed that true understanding of ''conscience'' and its relationship with ''morality'' has been hampered by an "impetuous" belief that philosophical questions are solved through the analysis of language in an area where clarity threatens vested interests. Susan Sontag similarly argued that it was a symptom of psychological immaturity not to recognise that many morally immature people willingly experience a form of delight, in some an erotic breaking of taboo, when witnessing violence, suffering and pain being inflicted on others. Jonathan Glover wrote that most of us "do not spend our lives on endless landscape gardening of our self" and our ''conscience'' is likely shaped not so much by heroic struggles, as by choice of partner, friends and job, as well as where we choose to live. Garrett Hardin, in a famous article called "The Tragedy of the Commons", argues that any instance in which society appeals to an individual exploiting a commons to restrain himself or herself for the general good—by means of his or her ''conscience''—merely sets up a system which, by selectively diverting societal power and physical resources to those lacking in ''conscience'', while fostering guilt (including anxiety about his or her individual contribution to over-population) in people acting upon it, actually works toward the elimination of conscience from the race.Garrett Hardin

The philosopher Peter Singer considers that usually when we describe an action as conscientious in the critical sense we do so in order to deny either that the relevant agent was motivated by selfish desires, like greed or ambition, or that he acted on whim or impulse.

Moral anti-realists debate whether the moral facts necessary to activate conscience supervenience, supervene on natural facts with ''Empirical evidence, a posteriori'' necessity; or arise ''a priori'' because moral facts have a primary intension and naturally identical worlds may be presumed morally identical. It has also been argued that there is a measure of moral luck in how circumstances create the obstacles which ''conscience'' must overcome to apply moral principles or human rights and that with the benefit of enforceable property rights and the rule of law, access to universal health care plus the absence of high adult and infant mortality from conditions such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and famine, people in relatively prosperous developed countries have been spared pangs of ''conscience'' associated with the physical necessity to steal scraps of food, bribe tax inspectors or police officers, and commit murder in guerrilla wars against corrupt government forces or rebel armies. Roger Scruton has claimed that true understanding of ''conscience'' and its relationship with ''morality'' has been hampered by an "impetuous" belief that philosophical questions are solved through the analysis of language in an area where clarity threatens vested interests. Susan Sontag similarly argued that it was a symptom of psychological immaturity not to recognise that many morally immature people willingly experience a form of delight, in some an erotic breaking of taboo, when witnessing violence, suffering and pain being inflicted on others. Jonathan Glover wrote that most of us "do not spend our lives on endless landscape gardening of our self" and our ''conscience'' is likely shaped not so much by heroic struggles, as by choice of partner, friends and job, as well as where we choose to live. Garrett Hardin, in a famous article called "The Tragedy of the Commons", argues that any instance in which society appeals to an individual exploiting a commons to restrain himself or herself for the general good—by means of his or her ''conscience''—merely sets up a system which, by selectively diverting societal power and physical resources to those lacking in ''conscience'', while fostering guilt (including anxiety about his or her individual contribution to over-population) in people acting upon it, actually works toward the elimination of conscience from the race.Garrett Hardin

"The Tragedy of the Commons"

''Science'', Vol. 162, No. 3859 (13 December 1968), pp. 1243–48. Also available her

an

here.

John Ralston Saul expressed the view in ''The Unconscious Civilization'' that in contemporary developed nations many people have acquiesced in turning over their sense of right and wrong, their ''critical conscience'', to technical experts; willingly restricting their moral freedom of choice to limited consumer actions ruled by the ideology of the free market, while citizen participation in public affairs is limited to the isolated act of voting and private-interest lobbying turns even elected representatives against the public interest. Some argue on religious or philosophical grounds that it is blameworthy to act against ''conscience'', even if the judgement of ''conscience'' is likely to be erroneous (say because it is inadequately informed about the facts, or prevailing moral (humanist or religious), professional ethical, legal and human rights norms). Failure to acknowledge and accept that conscientious judgements can be seriously mistaken, may only promote situations where one's conscience is manipulated by others to provide unwarranted justifications for non-virtuous and selfish acts; indeed, insofar as it is appealed to as glorifying ideological content, and an associated extreme level of devotion, without adequate constraint of external, altruistic, normative justification, conscience may be considered morally blind and dangerous both to the individual concerned and humanity as a whole. Langston argues that philosophers of virtue ethics have unnecessarily neglected ''conscience'' for, once conscience is trained so that the principles and rules it applies are those one would want all others to live by, its practise cultivates and sustains the virtues; indeed, amongst people in what each society considers to be the highest state of moral development there is little disagreement about how to act. Emmanuel Levinas viewed conscience as a revelatory encountering of resistance to our selfish powers, developing morality by calling into question our naive sense of freedom of will to use such powers arbitrarily, or with violence, this process being more severe the more rigorously the goal of our self was to obtain control.Emmanuel Levinas. ''Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority''. Lingis A (trans) Duquesne University Press, Pittsburgh, PA 1998. pp. 84, 100–01 In other words, the welcoming of the ''Other'', to Levinas, was the very essence of ''conscience'' properly conceived; it encouraged our ego to accept the fallibility of assuming things about other people, that selfish freedom of will "does not have the last word" and that realising this has a transcendent purpose: "I am not alone ... in conscience I have an experience that is not commensurate with any a priori [see a priori and a posteriori] framework-a conceptless experience."

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, English litigants began to petition the Lord Chancellor of England for relief from unjust judgments. As Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Chancellor intervened to allow for "merciful exceptions" to the King's laws, "to ensure that the King's conscience was right before God". The Chancellor's office evolved into the Court of Chancery and the Chancellor's decisions evolved into the body of law known as Equity (law), equity.

English humanist lawyers in the 16th and 17th centuries interpreted conscience as a collection of universal principles given to man by god at creation to be applied by reason; this gradually reforming the medieval Roman law-based system with forms of action, written pleadings, use of juries and patterns of litigation such as Demurrer and Assumpsit that displayed an increased concern for elements of right and wrong on the actual facts. A conscience vote in a parliament allows legislators to vote without restrictions from any political party to which they may belong. In his trial in Jerusalem Nazi war crime, war criminal

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, English litigants began to petition the Lord Chancellor of England for relief from unjust judgments. As Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Chancellor intervened to allow for "merciful exceptions" to the King's laws, "to ensure that the King's conscience was right before God". The Chancellor's office evolved into the Court of Chancery and the Chancellor's decisions evolved into the body of law known as Equity (law), equity.

English humanist lawyers in the 16th and 17th centuries interpreted conscience as a collection of universal principles given to man by god at creation to be applied by reason; this gradually reforming the medieval Roman law-based system with forms of action, written pleadings, use of juries and patterns of litigation such as Demurrer and Assumpsit that displayed an increased concern for elements of right and wrong on the actual facts. A conscience vote in a parliament allows legislators to vote without restrictions from any political party to which they may belong. In his trial in Jerusalem Nazi war crime, war criminal

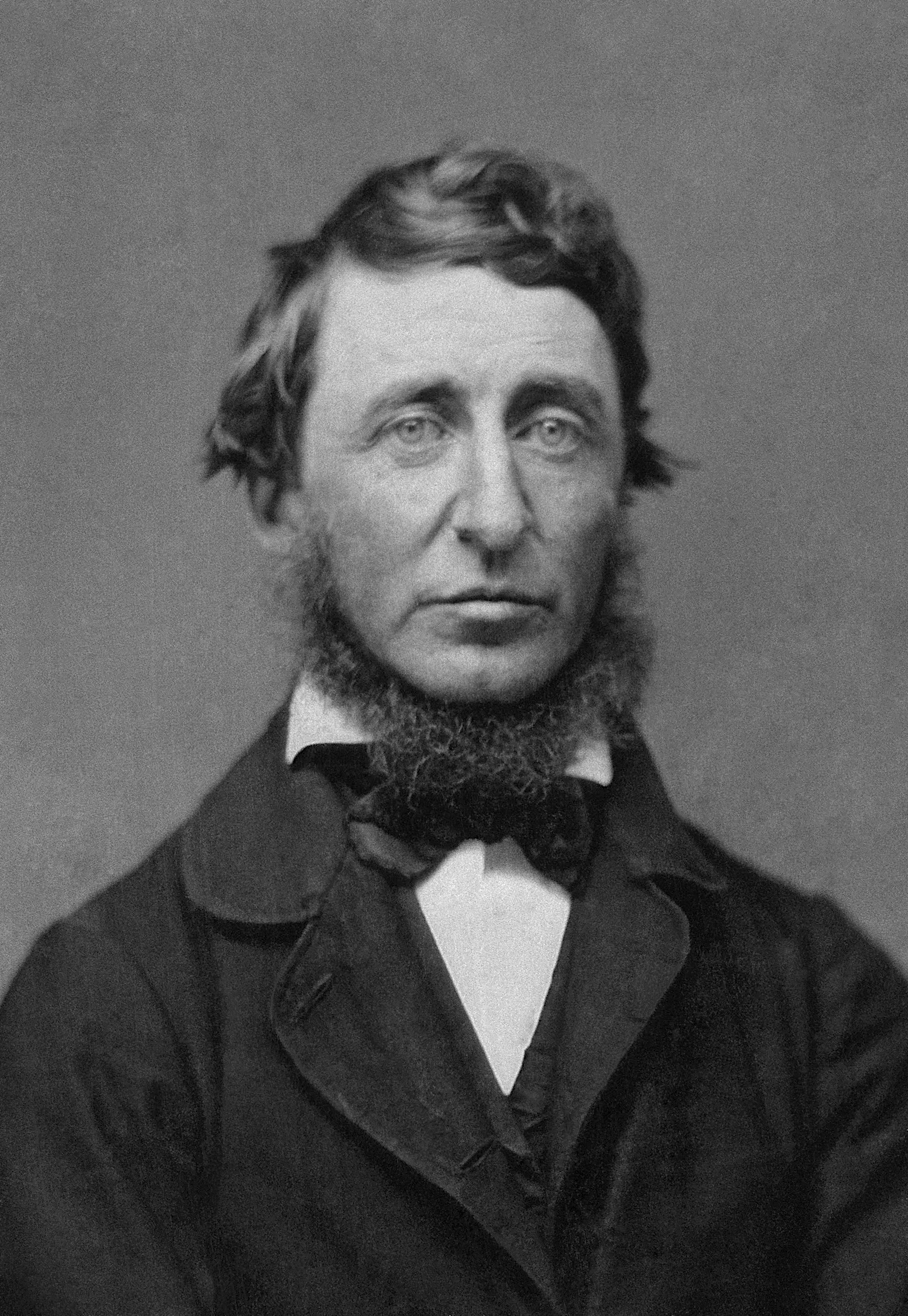

John Rawls in his ''A Theory of Justice'' defines a conscientious objector as an individual prepared to undertake, in public (and often despite widespread condemnation), an action of civil disobedience to a legal rule justifying it (also in public) by reference to contrary foundational social virtues (such as justice as liberty or fairness) and the principles of morality and law derived from them.John Rawls. ''A Theory of Justice''. Oxford University Press. London 1971. pp. 368–70 Rawls considered civil disobedience should be viewed as an appeal, warning or admonishment (showing general respect and fidelity to the rule of law by the non-violence and transparency of methods adopted) that a law breaches a community's fundamental virtue of justice. Objections to Rawls' theory include first, its inability to accommodate conscientious objections to the society's basic appreciation of justice or to emerging moral or ethical principles (such as respect for the rights of the natural environment) which are not yet part of it and second, the difficulty of predictably and consistently determining that a majority decision is just or unjust. ''Conscientious objection'' (also called conscientious refusal or evasion) to obeying a law, should not arise from unreasoning, naive "traditional conscience", for to do so merely encourages infantile abdication of responsibility to calibrate the law against moral or human rights norms and disrespect for democratic institutions. Instead it should be based on "critical conscience' – seriously thought out, conceptually mature, personal moral or religious beliefs held to be fundamentally incompatible (that is, not merely inconsistent on the basis of selfish desires, whim or impulse), for example, either with all laws requiring conscription for military service, or legal compulsion to fight for or financially support the State in a particular war. A famous example arose when Henry David Thoreau the author of ''Walden'' was willingly jailed for refusing to pay a tax because he profoundly disagreed with a government policy and was frustrated by the corruption and injustice of the democratic machinery of the State (polity), state. A more recent case concerned Kimberly Rivera, a private in the US Army and mother of four children who, having served three months in Iraq War decided the conflict was immoral and sought refugee status in Canada in 2012 (see List of Iraq War resisters), but was deported and arrested in the US.

John Rawls in his ''A Theory of Justice'' defines a conscientious objector as an individual prepared to undertake, in public (and often despite widespread condemnation), an action of civil disobedience to a legal rule justifying it (also in public) by reference to contrary foundational social virtues (such as justice as liberty or fairness) and the principles of morality and law derived from them.John Rawls. ''A Theory of Justice''. Oxford University Press. London 1971. pp. 368–70 Rawls considered civil disobedience should be viewed as an appeal, warning or admonishment (showing general respect and fidelity to the rule of law by the non-violence and transparency of methods adopted) that a law breaches a community's fundamental virtue of justice. Objections to Rawls' theory include first, its inability to accommodate conscientious objections to the society's basic appreciation of justice or to emerging moral or ethical principles (such as respect for the rights of the natural environment) which are not yet part of it and second, the difficulty of predictably and consistently determining that a majority decision is just or unjust. ''Conscientious objection'' (also called conscientious refusal or evasion) to obeying a law, should not arise from unreasoning, naive "traditional conscience", for to do so merely encourages infantile abdication of responsibility to calibrate the law against moral or human rights norms and disrespect for democratic institutions. Instead it should be based on "critical conscience' – seriously thought out, conceptually mature, personal moral or religious beliefs held to be fundamentally incompatible (that is, not merely inconsistent on the basis of selfish desires, whim or impulse), for example, either with all laws requiring conscription for military service, or legal compulsion to fight for or financially support the State in a particular war. A famous example arose when Henry David Thoreau the author of ''Walden'' was willingly jailed for refusing to pay a tax because he profoundly disagreed with a government policy and was frustrated by the corruption and injustice of the democratic machinery of the State (polity), state. A more recent case concerned Kimberly Rivera, a private in the US Army and mother of four children who, having served three months in Iraq War decided the conflict was immoral and sought refugee status in Canada in 2012 (see List of Iraq War resisters), but was deported and arrested in the US.

In the Second World War, Great Britain granted conscientious-objection status not just to complete pacifists, but to those who objected to fighting in that particular war; this was done partly out of genuine respect, but also to avoid the disgraceful and futile persecutions of conscientious objectors that occurred during the First World War.

Amnesty International organises campaigns to protect those arrested and or incarcerated as a prisoner of conscience because of their conscientious beliefs, particularly concerning intellectual, political and artistic freedom of expression and association. Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma, was the winner of the 2009 Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award. In legislation, a conscience clause (medical), conscience clause is a provision in a statute that excuses a health professional from complying with the law (for example legalising surgical or pharmaceutical abortion) if it is incompatible with religious or conscientious beliefs.

Expressed justifications for refusing to obey laws because of conscience vary. Many conscientious objectors are so for religious reasons—notably, members of the peace churches, historic peace churches are pacifist by doctrine. Other objections can stem from a deep sense of responsibility toward humanity as a whole, or from the conviction that even acceptance of work under military orders acknowledges the principle of conscription that should be everywhere condemned before the world can ever become safe for real democracy. A conscientious objector, however, does not have a primary aim of changing the law. John Dewey considered that conscientious objectors were often the victims of "moral innocency" and inexpertness in moral training: "the moving force of events is always too much for conscience".Dykhuizen, George. ''The Life and Mind of John Dewey''. Southern Illinois University Press. London. 1978. p. 165 The remedy was not to deplore the wickedness of those who manipulate world power, but to connect ''conscience'' with forces moving in another direction- to build institutions and social environments predicated on the rule of law, for example, "then will conscience itself have compulsive power instead of being forever the martyred and the coerced." As an example, Albert Einstein who had advocated ''conscientious objection'' during the First World War and had been a longterm supporter of War Resisters' International reasoned that "radical pacifism" could not be justified in the face of Nazi rearmament and advocated a world federalist organization with its own professional army.

Samuel Johnson pointed out that an appeal to conscience should not allow the law to bring unjust suffering upon another. ''Conscience'', according to Johnson, was nothing more than a conviction felt by ourselves of something to be done or something to be avoided; in questions of simple unperplexed morality, ''conscience'' is very often a guide that may be trusted.James Boswell. ''Life of Johnson''. Oxford University Press. London. 1927 Vol. I 1709–1776. p. 505. But before ''conscience'' can conclusively determine what morally should be done, he thought that the state of the question should be thoroughly known. "No man's conscience", said Johnson "can tell him the right of another man ... it is a conscience very ill informed that violates the rights of one man, for the convenience of another."

In the Second World War, Great Britain granted conscientious-objection status not just to complete pacifists, but to those who objected to fighting in that particular war; this was done partly out of genuine respect, but also to avoid the disgraceful and futile persecutions of conscientious objectors that occurred during the First World War.

Amnesty International organises campaigns to protect those arrested and or incarcerated as a prisoner of conscience because of their conscientious beliefs, particularly concerning intellectual, political and artistic freedom of expression and association. Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma, was the winner of the 2009 Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award. In legislation, a conscience clause (medical), conscience clause is a provision in a statute that excuses a health professional from complying with the law (for example legalising surgical or pharmaceutical abortion) if it is incompatible with religious or conscientious beliefs.

Expressed justifications for refusing to obey laws because of conscience vary. Many conscientious objectors are so for religious reasons—notably, members of the peace churches, historic peace churches are pacifist by doctrine. Other objections can stem from a deep sense of responsibility toward humanity as a whole, or from the conviction that even acceptance of work under military orders acknowledges the principle of conscription that should be everywhere condemned before the world can ever become safe for real democracy. A conscientious objector, however, does not have a primary aim of changing the law. John Dewey considered that conscientious objectors were often the victims of "moral innocency" and inexpertness in moral training: "the moving force of events is always too much for conscience".Dykhuizen, George. ''The Life and Mind of John Dewey''. Southern Illinois University Press. London. 1978. p. 165 The remedy was not to deplore the wickedness of those who manipulate world power, but to connect ''conscience'' with forces moving in another direction- to build institutions and social environments predicated on the rule of law, for example, "then will conscience itself have compulsive power instead of being forever the martyred and the coerced." As an example, Albert Einstein who had advocated ''conscientious objection'' during the First World War and had been a longterm supporter of War Resisters' International reasoned that "radical pacifism" could not be justified in the face of Nazi rearmament and advocated a world federalist organization with its own professional army.

Samuel Johnson pointed out that an appeal to conscience should not allow the law to bring unjust suffering upon another. ''Conscience'', according to Johnson, was nothing more than a conviction felt by ourselves of something to be done or something to be avoided; in questions of simple unperplexed morality, ''conscience'' is very often a guide that may be trusted.James Boswell. ''Life of Johnson''. Oxford University Press. London. 1927 Vol. I 1709–1776. p. 505. But before ''conscience'' can conclusively determine what morally should be done, he thought that the state of the question should be thoroughly known. "No man's conscience", said Johnson "can tell him the right of another man ... it is a conscience very ill informed that violates the rights of one man, for the convenience of another."

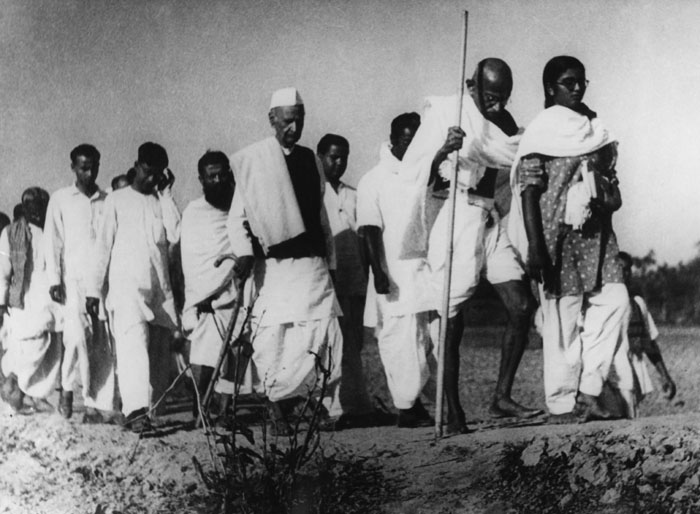

Civil disobedience as nonviolent protest or civil resistance are also acts of conscience, but are designed by those who undertake them chiefly to change, by appealing to the majority and democratic processes, laws or government policies perceived to be incoherent with fundamental social virtues and principles (such as justice, equality or respect for intrinsic human dignity). Civil disobedience, in a properly functioning democracy, allows a minority who feel strongly that a law infringes their sense of justice (but have no capacity to obtain legislative amendments or a referendum on the issue) to make a potentially apathetic or uninformed majority take account of the intensity of opposing views. A notable example of civil resistance or satyagraha ("satya" in sanskrit means "truth and compassion", "agraha" means "firmness of will") involved Mahatma Gandhi making salt in India when that act was prohibited by a United Kingdom, British statute, in order to create moral pressure for law reform. Rosa Parks similarly acted on conscience in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama refusing a legal order to give up her seat to make room for a white passenger; her action (and the similar earlier act of 15-year-old Claudette Colvin) led to the Montgomery bus boycott. Rachel Corrie was a US citizen allegedly killed by a bulldozer operated by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) while involved in direct action (based on the nonviolent principles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi) to prevent demolition of the home of local Palestinian people, Palestinian pharmacist Samir Nasrallah. Al Gore has argued "If you're a young person looking at the future of this planet and looking at what is being done right now, and not done, I believe we have reached the stage where it is time for civil disobedience to prevent the construction of new coal plants that do not have carbon capture and sequestration." In 2011, NASA climate scientist James E. Hansen, environmental leader Phil Radford and Professor Bill McKibben were arrested for opposing a tar sands oil pipeline and Canadian renewable energy professor Mark Jaccard was arrested for opposing mountain-top coal mining; in his book Storms of my Grandchildren Hansen calls for similar civil resistance on a global scale to help replace the 'business-as-usual' Kyoto Protocol cap and trade system, with a progressive carbon tax at emission source on the oil, gas and coal industries – revenue being paid as dividends to low carbon footprint families.James Hansen. Tell Barack Obama the Truth – The Whole Truth. accessed 10 December 2009.

Notable historical examples of ''conscientious noncompliance'' in a different professional context included the manipulation of the visa process in 1939 by Japanese Consul-General Chiune Sugihara in Kaunas (the temporary capital of Lithuania between Germany and the Soviet Union) and by Raoul Wallenberg in Hungary in 1944 to allow Jews to escape almost certain death. Ho Feng-Shan the Chinese Consul-General in Vienna in 1939, defied orders from the Chinese ambassador in Berlin to issue Jews with visas for Shanghai. John Rabe a German member of the Nazi Party likewise saved thousands of Chinese from massacre by the Japanese military at Nanjing Massacre, Nanjing. The White Rose German student movement against the Nazis declared in their 4th leaflet: "We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!" ''Conscientious noncompliance'' may be the only practical option for citizens wishing to affirm the existence of an international moral order or 'core' historical rights (such as the right to life, right to a fair trial and freedom of opinion) in states where non-violent protest or civil disobedience are met with prolonged arbitrary detention, torture, forced disappearance, murder or persecution.

The controversial Milgram experiment into obedience (human behavior), obedience by Stanley Milgram showed that many people lack the psychological resources to openly resist

Civil disobedience as nonviolent protest or civil resistance are also acts of conscience, but are designed by those who undertake them chiefly to change, by appealing to the majority and democratic processes, laws or government policies perceived to be incoherent with fundamental social virtues and principles (such as justice, equality or respect for intrinsic human dignity). Civil disobedience, in a properly functioning democracy, allows a minority who feel strongly that a law infringes their sense of justice (but have no capacity to obtain legislative amendments or a referendum on the issue) to make a potentially apathetic or uninformed majority take account of the intensity of opposing views. A notable example of civil resistance or satyagraha ("satya" in sanskrit means "truth and compassion", "agraha" means "firmness of will") involved Mahatma Gandhi making salt in India when that act was prohibited by a United Kingdom, British statute, in order to create moral pressure for law reform. Rosa Parks similarly acted on conscience in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama refusing a legal order to give up her seat to make room for a white passenger; her action (and the similar earlier act of 15-year-old Claudette Colvin) led to the Montgomery bus boycott. Rachel Corrie was a US citizen allegedly killed by a bulldozer operated by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) while involved in direct action (based on the nonviolent principles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi) to prevent demolition of the home of local Palestinian people, Palestinian pharmacist Samir Nasrallah. Al Gore has argued "If you're a young person looking at the future of this planet and looking at what is being done right now, and not done, I believe we have reached the stage where it is time for civil disobedience to prevent the construction of new coal plants that do not have carbon capture and sequestration." In 2011, NASA climate scientist James E. Hansen, environmental leader Phil Radford and Professor Bill McKibben were arrested for opposing a tar sands oil pipeline and Canadian renewable energy professor Mark Jaccard was arrested for opposing mountain-top coal mining; in his book Storms of my Grandchildren Hansen calls for similar civil resistance on a global scale to help replace the 'business-as-usual' Kyoto Protocol cap and trade system, with a progressive carbon tax at emission source on the oil, gas and coal industries – revenue being paid as dividends to low carbon footprint families.James Hansen. Tell Barack Obama the Truth – The Whole Truth. accessed 10 December 2009.

Notable historical examples of ''conscientious noncompliance'' in a different professional context included the manipulation of the visa process in 1939 by Japanese Consul-General Chiune Sugihara in Kaunas (the temporary capital of Lithuania between Germany and the Soviet Union) and by Raoul Wallenberg in Hungary in 1944 to allow Jews to escape almost certain death. Ho Feng-Shan the Chinese Consul-General in Vienna in 1939, defied orders from the Chinese ambassador in Berlin to issue Jews with visas for Shanghai. John Rabe a German member of the Nazi Party likewise saved thousands of Chinese from massacre by the Japanese military at Nanjing Massacre, Nanjing. The White Rose German student movement against the Nazis declared in their 4th leaflet: "We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!" ''Conscientious noncompliance'' may be the only practical option for citizens wishing to affirm the existence of an international moral order or 'core' historical rights (such as the right to life, right to a fair trial and freedom of opinion) in states where non-violent protest or civil disobedience are met with prolonged arbitrary detention, torture, forced disappearance, murder or persecution.

The controversial Milgram experiment into obedience (human behavior), obedience by Stanley Milgram showed that many people lack the psychological resources to openly resist

The microcredit initiatives of Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus have been described as inspiring a "war on poverty that blends social conscience and business savvy".

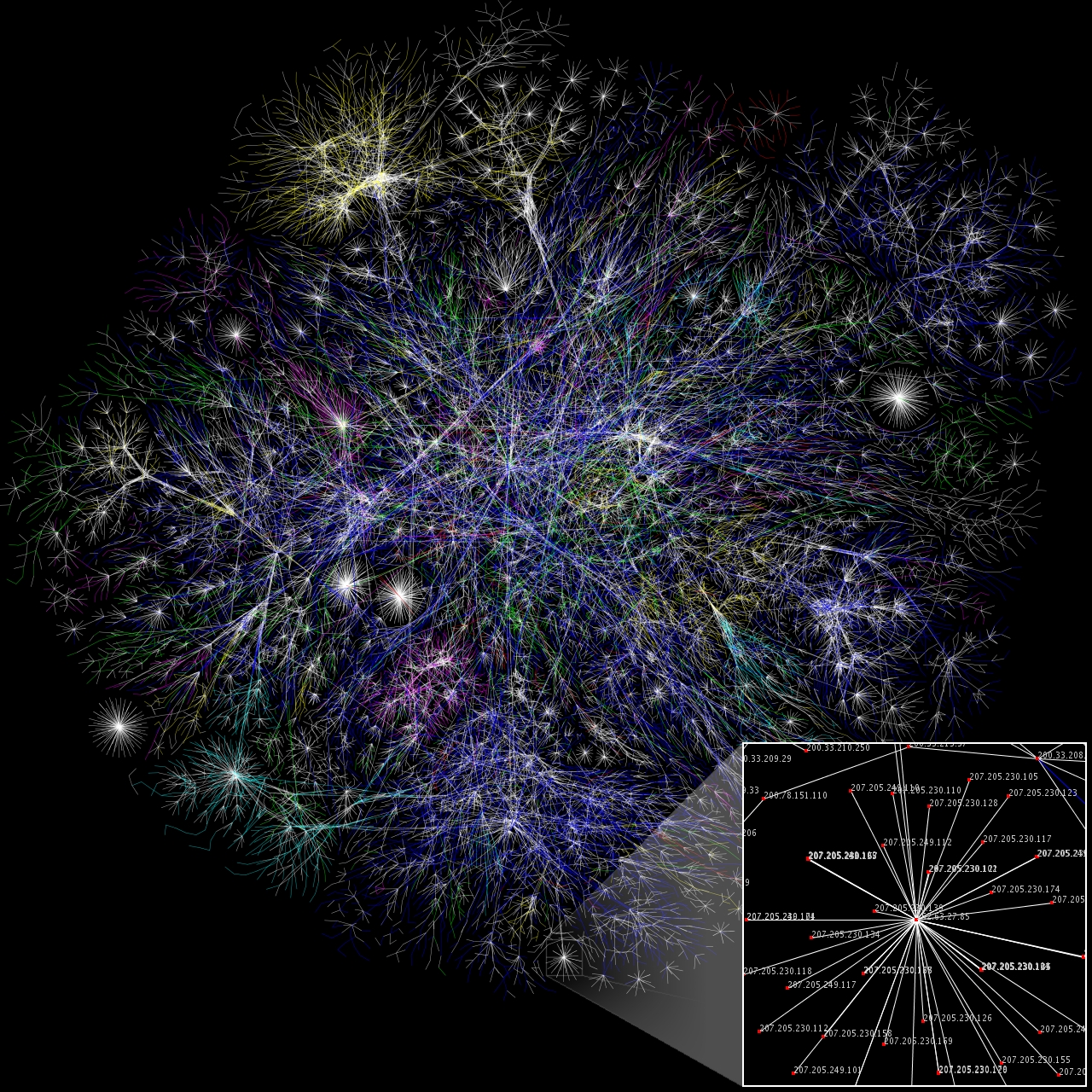

The Green party politician Bob Brown (who was arrested by the Tasmanian state police for a conscientious act of civil disobedience during the Franklin Dam protest) expresses ''world conscience'' in these terms: "the universe, through us, is evolving towards experiencing, understanding and making choices about its future'; one example of policy outcomes from such thinking being a global tax (see Tobin tax) to alleviate global poverty and protect the biosphere, amounting to 1/10 of 1% placed on the worldwide speculative currency market. Such an approach sees ''world conscience'' best expressing itself through political reforms promoting democratically based globalisation or ''planetary democracy'' (for example internet voting for global governance organisations (see world government) based on the model of "one person, one vote, one value") which gradually will replace contemporary market-based globalisation.

The microcredit initiatives of Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus have been described as inspiring a "war on poverty that blends social conscience and business savvy".

The Green party politician Bob Brown (who was arrested by the Tasmanian state police for a conscientious act of civil disobedience during the Franklin Dam protest) expresses ''world conscience'' in these terms: "the universe, through us, is evolving towards experiencing, understanding and making choices about its future'; one example of policy outcomes from such thinking being a global tax (see Tobin tax) to alleviate global poverty and protect the biosphere, amounting to 1/10 of 1% placed on the worldwide speculative currency market. Such an approach sees ''world conscience'' best expressing itself through political reforms promoting democratically based globalisation or ''planetary democracy'' (for example internet voting for global governance organisations (see world government) based on the model of "one person, one vote, one value") which gradually will replace contemporary market-based globalisation.

The American cardiologist Bernard Lown and the Russian cardiologist Yevgeniy Chazov were motivated in ''conscience'' through studying the catastrophic public health consequences of nuclear war in establishing International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985 and continues to work to "heal an ailing planet".

The American cardiologist Bernard Lown and the Russian cardiologist Yevgeniy Chazov were motivated in ''conscience'' through studying the catastrophic public health consequences of nuclear war in establishing International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985 and continues to work to "heal an ailing planet".

Worldwide expressions of ''conscience'' contributed to the decision of the French government to halt atmospheric nuclear tests at Mururoa in the Pacific in 1974 after 41 such explosions (although below-ground nuclear tests continued there into the 1990s). A challenge to ''world conscience'' was provided by an influential 1968 article by Garrett Hardin that critically analyzed the dilemma in which multiple individuals, acting independently after rationally consulting self-interest (and, he claimed, the apparently low 'survival-of-the-fittest' value of ''conscience''-led actions) ultimately destroy a shared limited resource, even though each acknowledges such an outcome is not in anyone's long-term interest. Hardin's conclusion that commons areas are practicably achievable only in conditions of low population density (and so their continuance requires state restriction on the freedom to breed), created controversy additionally through his direct deprecation of the role of ''conscience'' in achieving individual decisions, policies and laws that facilitate global justice and peace, as well as sustainability and sustainable development of world commons areas, for example including those officially designated such under United Nations treaties (see common heritage of humanity). Areas designated common heritage of humanity under international law include the Moon, Outer Space, deep sea bed, Antarctica, the world cultural and natural heritage (see World Heritage Convention) and the human genome. It will be a significant challenge for ''world conscience'' that as world oil, coal, mineral, timber, agricultural and water reserves are depleted, there will be increasing pressure to commercially exploit common heritage of mankind areas. The philosopher Peter Singer has argued that the United Nations Millennium Development Goals represent the emergence of an ethics based not on national boundaries but on the idea of one world. Ninian Smart has similarly predicted that the increase in global travel and communication will gradually draw the world's religions towards a pluralistic and transcendental humanism characterized by an "open spirit" of empathy and compassion.

Noam Chomsky has argued that forces opposing the development of such a world conscience include free market ideologies that valorise corporate greed in nominal electoral democracies where advertising, shopping malls and indebtedness, shape citizens into apathetic consumers in relation to information and access necessary for democratic participation. John Passmore has argued that mystical considerations about the global expansion of all human consciousness, should take into account that if as a species we do become something much superior to what we are now, it will be as a consequence of ''conscience'' not only implanting a goal of moral perfectibility, but assisting us to remain periodically anxious, passionate and discontented, for these are necessary components of care and compassion. The ''Committee on Conscience'' of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum has targeted genocides such as those in Rwanda, Bosnia, Darfur, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congo and Chechnya as challenges to the world's conscience. Oscar Arias Sanchez has criticised global arms industry spending as a failure of conscience by nation states: "When a country decides to invest in arms, rather than in education, housing, the environment, and health services for its people, it is depriving a whole generation of its right to prosperity and happiness. We have produced one firearm for every ten inhabitants of this planet, and yet we have not bothered to end hunger when such a feat is well within our reach. This is not a necessary or inevitable state of affairs. It is a deliberate choice" (see Campaign Against Arms Trade). US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, after meeting with the 14th Dalai Lama during the 2008 Tibetan unrest, 2008 violent protests in Tibet and aftermath said: "The situation in Tibet is a challenge to the conscience of the world." Nelson Mandela, through his example and words, has been described as having shaped the conscience of the world.

The philosopher Peter Singer has argued that the United Nations Millennium Development Goals represent the emergence of an ethics based not on national boundaries but on the idea of one world. Ninian Smart has similarly predicted that the increase in global travel and communication will gradually draw the world's religions towards a pluralistic and transcendental humanism characterized by an "open spirit" of empathy and compassion.

Noam Chomsky has argued that forces opposing the development of such a world conscience include free market ideologies that valorise corporate greed in nominal electoral democracies where advertising, shopping malls and indebtedness, shape citizens into apathetic consumers in relation to information and access necessary for democratic participation. John Passmore has argued that mystical considerations about the global expansion of all human consciousness, should take into account that if as a species we do become something much superior to what we are now, it will be as a consequence of ''conscience'' not only implanting a goal of moral perfectibility, but assisting us to remain periodically anxious, passionate and discontented, for these are necessary components of care and compassion. The ''Committee on Conscience'' of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum has targeted genocides such as those in Rwanda, Bosnia, Darfur, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congo and Chechnya as challenges to the world's conscience. Oscar Arias Sanchez has criticised global arms industry spending as a failure of conscience by nation states: "When a country decides to invest in arms, rather than in education, housing, the environment, and health services for its people, it is depriving a whole generation of its right to prosperity and happiness. We have produced one firearm for every ten inhabitants of this planet, and yet we have not bothered to end hunger when such a feat is well within our reach. This is not a necessary or inevitable state of affairs. It is a deliberate choice" (see Campaign Against Arms Trade). US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, after meeting with the 14th Dalai Lama during the 2008 Tibetan unrest, 2008 violent protests in Tibet and aftermath said: "The situation in Tibet is a challenge to the conscience of the world." Nelson Mandela, through his example and words, has been described as having shaped the conscience of the world.

The Right Livelihood Award is awarded yearly in Sweden to those people, mostly strongly motivated by ''conscience'', who have made exemplary practical contributions to resolving the great challenges facing our planet and its people. In 2009, for example, along with Catherine Hamlin (obstetric fistula and see fistula foundation)), David Suzuki (promoting awareness of climate change) and Alyn Ware (nuclear disarmament), René Ngongo shared the Right Livelihood Award "for his courage in confronting the forces that are destroying the Congo Basin's rainforests and building political support for their conservation and sustainable use". Avaaz is one of the largest global on-line organizations launched in January 2007 to promote conscience-driven activism on issues such as climate change, human rights, animal rights, corruption, poverty, and conflict, thus "closing the gap between the world we have and the world most people everywhere want".

Conscience played a major role in the actions by anaesthetist Stephen Bolsin to whistleblow (see list of whistleblowers) on incompetent paediatric cardiac surgeons at the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Jeffrey Wigand was motivated by conscience to expose the Big Tobacco scandal, revealing that executives of the companies knew that cigarettes were addictive and approved the addition of carcinogenic ingredients to the cigarettes. David Graham (epidemiologist), David Graham, a Food and Drug Administration employee, was motivated by conscience to whistleblow that the arthritis pain-reliever Vioxx increased the risk of cardiovascular deaths although the manufacturer suppressed this information. Rick Piltz, from the U.S. Climate change, global warming Science Program, blew the whistle on a White House official who ignored majority scientific opinion to edit a climate change report ("Our Changing Planet") to reflect the Presidency of George W. Bush, Bush administration's view that the problem was unlikely to exist. Muntadhar al-Zaidi, an Iraqi journalist, was imprisoned and allegedly tortured for his act of conscience in throwing his shoes at George W. Bush. Mordechai Vanunu, an Israeli former nuclear technician, acted on conscience to reveal details of Israel's nuclear weapons program to the United Kingdom, British press in 1986; was kidnapped by Israeli agents, transported to Israel, convicted of treason and spent 18 years in prison, including more than 11 years in solitary confinement.

Conscience played a major role in the actions by anaesthetist Stephen Bolsin to whistleblow (see list of whistleblowers) on incompetent paediatric cardiac surgeons at the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Jeffrey Wigand was motivated by conscience to expose the Big Tobacco scandal, revealing that executives of the companies knew that cigarettes were addictive and approved the addition of carcinogenic ingredients to the cigarettes. David Graham (epidemiologist), David Graham, a Food and Drug Administration employee, was motivated by conscience to whistleblow that the arthritis pain-reliever Vioxx increased the risk of cardiovascular deaths although the manufacturer suppressed this information. Rick Piltz, from the U.S. Climate change, global warming Science Program, blew the whistle on a White House official who ignored majority scientific opinion to edit a climate change report ("Our Changing Planet") to reflect the Presidency of George W. Bush, Bush administration's view that the problem was unlikely to exist. Muntadhar al-Zaidi, an Iraqi journalist, was imprisoned and allegedly tortured for his act of conscience in throwing his shoes at George W. Bush. Mordechai Vanunu, an Israeli former nuclear technician, acted on conscience to reveal details of Israel's nuclear weapons program to the United Kingdom, British press in 1986; was kidnapped by Israeli agents, transported to Israel, convicted of treason and spent 18 years in prison, including more than 11 years in solitary confinement.

At the awards ceremony for the 200 metres at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City John Carlos, Tommie Smith and Peter Norman ignored death threats and official warnings to take part in an anti-racism protest that destroyed their respective careers. W. Mark Felt an agent of the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation who retired in 1973 as the Bureau's Associate Director, acted on conscience to provide reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with information that resulted in the Watergate scandal. Conscience was a major factor in US Public Health Service officer Peter Buxtun revealing the Tuskegee syphilis experiment to the public. The 2008 attack by the Israeli military on civilian areas of Palestinian territories, Palestinian Gaza Strip, Gaza was described as a "stain on the world's conscience". Conscience was a major factor in the refusal of Aung San Suu Kyi to leave Burma despite house arrest and persecution by the military dictatorship in that country.

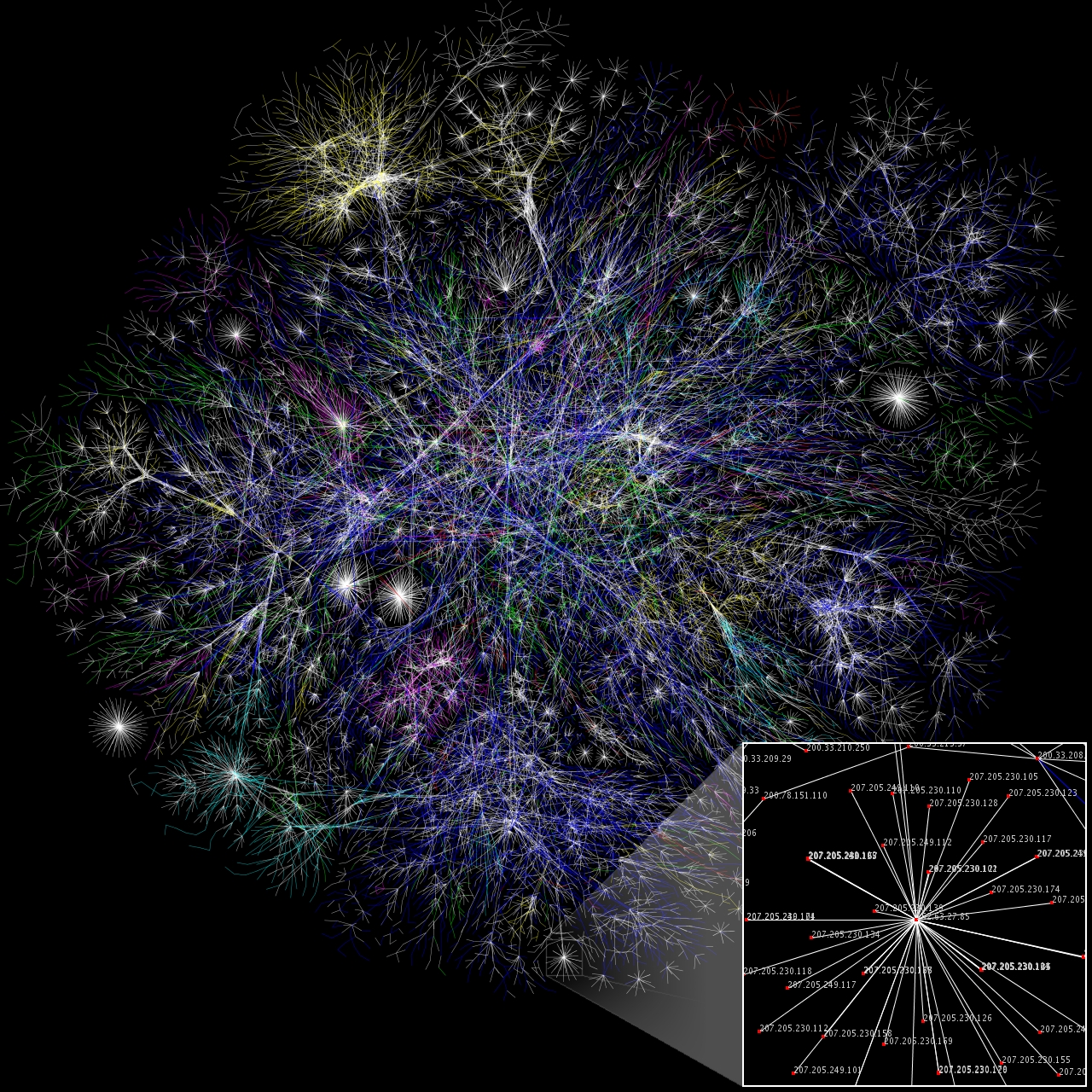

''Conscience'' was a factor in Peter Galbraith's criticism of fraud in the 2009 Afghanistan election despite it costing him his United Nations job. Conscience motivated Bunnatine Greenhouse to expose irregularities in the contracting of the Halliburton company for work in Iraq. Naji al-Ali a popular cartoon artist in the Arab world, loved for his defense of the ordinary people, and for his criticism of repression and despotism by both the Israeli military and Yasser Arafat's PLO, was murdered for refusing to compromise with his conscience. The journalist Anna Politkovskaya provided (prior to her murder) an example of conscience in her opposition to the Second Chechen War and then-Russian President Vladimir Putin. Conscience motivated the Russian human rights activist Natalia Estemirova, who was abducted and murdered in Grozny, Chechnya in 2009. The Death of Neda Agha-Soltan arose from conscience-driven protests against the 2009 Iranian presidential election. Muslim lawyer Shirin Ebadi (winner of the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize) has been described as the 'conscience of the Islamic Republic' for her work in protecting the human rights of women and children in Iran. The human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, often referred to as the 'conscience of China' and who had previously been arrested and allegedly tortured after calling for respect for human rights and for constitutional reform, was abducted by Chinese security agents in February 2009. 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo in his final statement before being sentenced by a closed Chinese court to over a decade in jail as a political prisoner of conscience stated: "For hatred is corrosive of a person’s wisdom and conscience; the mentality of enmity can poison a nation’s spirit." Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer in Russia, was arrested, held without trial for almost a year and died in custody, as a result of exposing corruption. On 6 October 2001 Laura Whittle was a naval gunner on HMAS Adelaide (FFG 01) under orders to implement a new border protection policy when they encountered the SIEV-4 (Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel-4) refugee boat in choppy seas. After being ordered to fire warning shots from her 50 calibre machinegun to make the boat turn back she saw it beginning to break up and sink with a father on board holding out his young daughter that she might be saved (see Children Overboard Affair). Whittle jumped without a life vest 12 metres into the sea to help save the refugees from drowning thinking "this isn't right; this isn't how things should be." In February 2012 journalist Marie Colvin was deliberately targeted and killed by the Syrian Army in Homs during the Syrian Revolution, Syrian uprising and Siege of Homs, after she decided to stay at the "epicentre of the storm" in order to "expose what is happening". In October 2012 the Taliban organised the attempted murder of Malala Yousafzai a teenage girl who had been campaigning, despite their threats, for female education in Pakistan. In December 2012 the 2012 Delhi gang rape case was said to have stirred the collective conscience of India to civil disobedience and public protest at the lack of legal action against rapists in that country (see Rape in India) In June 2013 Edward Snowden revealed details of a US National Security Agency internet and electronic communication PRISM (surveillance program) because of a conscience-felt obligation to the freedom of humanity greater than obedience to the laws that bound his employment.

At the awards ceremony for the 200 metres at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City John Carlos, Tommie Smith and Peter Norman ignored death threats and official warnings to take part in an anti-racism protest that destroyed their respective careers. W. Mark Felt an agent of the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation who retired in 1973 as the Bureau's Associate Director, acted on conscience to provide reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with information that resulted in the Watergate scandal. Conscience was a major factor in US Public Health Service officer Peter Buxtun revealing the Tuskegee syphilis experiment to the public. The 2008 attack by the Israeli military on civilian areas of Palestinian territories, Palestinian Gaza Strip, Gaza was described as a "stain on the world's conscience". Conscience was a major factor in the refusal of Aung San Suu Kyi to leave Burma despite house arrest and persecution by the military dictatorship in that country.

''Conscience'' was a factor in Peter Galbraith's criticism of fraud in the 2009 Afghanistan election despite it costing him his United Nations job. Conscience motivated Bunnatine Greenhouse to expose irregularities in the contracting of the Halliburton company for work in Iraq. Naji al-Ali a popular cartoon artist in the Arab world, loved for his defense of the ordinary people, and for his criticism of repression and despotism by both the Israeli military and Yasser Arafat's PLO, was murdered for refusing to compromise with his conscience. The journalist Anna Politkovskaya provided (prior to her murder) an example of conscience in her opposition to the Second Chechen War and then-Russian President Vladimir Putin. Conscience motivated the Russian human rights activist Natalia Estemirova, who was abducted and murdered in Grozny, Chechnya in 2009. The Death of Neda Agha-Soltan arose from conscience-driven protests against the 2009 Iranian presidential election. Muslim lawyer Shirin Ebadi (winner of the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize) has been described as the 'conscience of the Islamic Republic' for her work in protecting the human rights of women and children in Iran. The human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, often referred to as the 'conscience of China' and who had previously been arrested and allegedly tortured after calling for respect for human rights and for constitutional reform, was abducted by Chinese security agents in February 2009. 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo in his final statement before being sentenced by a closed Chinese court to over a decade in jail as a political prisoner of conscience stated: "For hatred is corrosive of a person’s wisdom and conscience; the mentality of enmity can poison a nation’s spirit." Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer in Russia, was arrested, held without trial for almost a year and died in custody, as a result of exposing corruption. On 6 October 2001 Laura Whittle was a naval gunner on HMAS Adelaide (FFG 01) under orders to implement a new border protection policy when they encountered the SIEV-4 (Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel-4) refugee boat in choppy seas. After being ordered to fire warning shots from her 50 calibre machinegun to make the boat turn back she saw it beginning to break up and sink with a father on board holding out his young daughter that she might be saved (see Children Overboard Affair). Whittle jumped without a life vest 12 metres into the sea to help save the refugees from drowning thinking "this isn't right; this isn't how things should be." In February 2012 journalist Marie Colvin was deliberately targeted and killed by the Syrian Army in Homs during the Syrian Revolution, Syrian uprising and Siege of Homs, after she decided to stay at the "epicentre of the storm" in order to "expose what is happening". In October 2012 the Taliban organised the attempted murder of Malala Yousafzai a teenage girl who had been campaigning, despite their threats, for female education in Pakistan. In December 2012 the 2012 Delhi gang rape case was said to have stirred the collective conscience of India to civil disobedience and public protest at the lack of legal action against rapists in that country (see Rape in India) In June 2013 Edward Snowden revealed details of a US National Security Agency internet and electronic communication PRISM (surveillance program) because of a conscience-felt obligation to the freedom of humanity greater than obedience to the laws that bound his employment.

The ancient epic of the Indian subcontinent, the Mahabharata of Vyasa, contains two pivotal moments of ''conscience''. The first occurs when the warrior Arjuna being overcome with compassion against killing his opposing relatives in war, receives counsel (see Bhagavad-Gita) from Krishna about his spiritual duty ("work as though you are performing a sacrifice for the general good"). The second, at the end of the saga, is when king Yudhishthira having alone survived the moral tests of life, is offered eternal bliss, only to refuse it because a faithful dog is prevented from coming with him by purported divine rules and laws. The French author Montaigne (1533–1592) in one of the most celebrated of Essays (Montaigne), his essays ("On experience") expressed the benefits of living with a clear conscience: "Our duty is to compose our character, not to compose books, to win not battles and provinces, but order and tranquillity in our conduct. Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live properly". In his famous Japanese travel journal ''Oku no Hosomichi'' (''Narrow Road to the Deep North'') composed of mixed haiku poetry and prose, Matsuo Bashō (1644–94) in attempting to describe the eternal in this perishable world is often moved in ''conscience''; for example by a thicket of summer grass being all that remains of the dreams and ambitions of ancient warriors. Chaucer's "Franklin's Tale" in ''The Canterbury Tales'' recounts how a young suitor releases a wife from a rash promise because of the respect in his ''conscience'' for the freedom to be truthful, gentle and generous.

The critic A. C. Bradley discusses the central problem of Shakespeare's tragic character Hamlet as one where conscience in the form of moral scruples deters the young Prince with his "great anxiety to do right" from obeying his father's hell-bound ghost and murdering the usurping King ("is't not perfect conscience to quit him with this arm?" (v.ii.67)).

Bradley develops a theory about Hamlet's moral agony relating to a conflict between "traditional" and "critical" conscience: "The conventional moral ideas of his time, which he shared with the Ghost, told him plainly that he ought to avenge his father; but a deeper conscience in him, which was in advance of his time, contended with these explicit conventional ideas. It is because this deeper conscience remains below the surface that he fails to recognise it, and fancies he is hindered by cowardice or Sloth (deadly sin), sloth or passion (emotion), passion or what not; but it emerges into light in that speech to Horatio. And it is just because he has this nobler moral nature in him that we admire and love him". The opening words of Shakespeare's Sonnet 94 ("They that have pow'r to hurt, and will do none") have been admired as a description of ''conscience''. So has John Donne's commencement of his poem '':s:Goodfriday, 1613. Riding Westward'': "Let man's soul be a sphere, and then, in this, Th' intelligence that moves, devotion is;"

Anton Chekhov in his plays ''The Seagull'', ''Uncle Vanya'' and ''Three Sisters (play), Three Sisters'' describes the tortured emotional states of doctors who at some point in their careers have turned their back on conscience. In his short stories, Anton Chekhov, Chekhov also explored how people misunderstood the voice of a tortured conscience. A promiscuous student, for example, in ''The Fit'' describes it as a "dull pain, indefinite, vague; it was like anguish and the most acute fear and despair ... in his breast, under the heart" and the young doctor examining the misunderstood agony of compassion experienced by the factory owner's daughter in ''From a Case Book'' calls it an "unknown, mysterious power ... in fact close at hand and watching him." Characteristically, Chekhov's own conscience drove him on the long journey to Sakhalin to record and alleviate the harsh conditions of the prisoners at that remote outpost. As Irina Ratushinskaya writes in the introduction to that work: "Abandoning everything, he travelled to the distant island of Sakhalin, the most feared place of exile and forced labour in Russia at that time. One cannot help but wonder why? Simply, because the lot of the people there was a bitter one, because nobody really knew about the lives and deaths of the exiles, because he felt that they stood in greater need of help that anyone else. A strange reason, maybe, but not for a writer who was the epitome of all the best traditions of a Russian man of letters. Russian literature has always focused on questions of conscience and was, therefore, a powerful force in the moulding of public opinion."

E. H. Carr writes of Dostoevsky's character the young student Raskolnikov in the novel ''Crime and Punishment'' who decides to murder a 'vile and loathsome' old woman money lender on the principle of transcending conventional morals: "the sequel reveals to us not the pangs of a stricken ''conscience'' (which a less subtle writer would have given us) but the tragic and fruitless struggle of a powerful intellect to maintain a conviction which is incompatible with the essential nature of man."

The ancient epic of the Indian subcontinent, the Mahabharata of Vyasa, contains two pivotal moments of ''conscience''. The first occurs when the warrior Arjuna being overcome with compassion against killing his opposing relatives in war, receives counsel (see Bhagavad-Gita) from Krishna about his spiritual duty ("work as though you are performing a sacrifice for the general good"). The second, at the end of the saga, is when king Yudhishthira having alone survived the moral tests of life, is offered eternal bliss, only to refuse it because a faithful dog is prevented from coming with him by purported divine rules and laws. The French author Montaigne (1533–1592) in one of the most celebrated of Essays (Montaigne), his essays ("On experience") expressed the benefits of living with a clear conscience: "Our duty is to compose our character, not to compose books, to win not battles and provinces, but order and tranquillity in our conduct. Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live properly". In his famous Japanese travel journal ''Oku no Hosomichi'' (''Narrow Road to the Deep North'') composed of mixed haiku poetry and prose, Matsuo Bashō (1644–94) in attempting to describe the eternal in this perishable world is often moved in ''conscience''; for example by a thicket of summer grass being all that remains of the dreams and ambitions of ancient warriors. Chaucer's "Franklin's Tale" in ''The Canterbury Tales'' recounts how a young suitor releases a wife from a rash promise because of the respect in his ''conscience'' for the freedom to be truthful, gentle and generous.

The critic A. C. Bradley discusses the central problem of Shakespeare's tragic character Hamlet as one where conscience in the form of moral scruples deters the young Prince with his "great anxiety to do right" from obeying his father's hell-bound ghost and murdering the usurping King ("is't not perfect conscience to quit him with this arm?" (v.ii.67)).

Bradley develops a theory about Hamlet's moral agony relating to a conflict between "traditional" and "critical" conscience: "The conventional moral ideas of his time, which he shared with the Ghost, told him plainly that he ought to avenge his father; but a deeper conscience in him, which was in advance of his time, contended with these explicit conventional ideas. It is because this deeper conscience remains below the surface that he fails to recognise it, and fancies he is hindered by cowardice or Sloth (deadly sin), sloth or passion (emotion), passion or what not; but it emerges into light in that speech to Horatio. And it is just because he has this nobler moral nature in him that we admire and love him". The opening words of Shakespeare's Sonnet 94 ("They that have pow'r to hurt, and will do none") have been admired as a description of ''conscience''. So has John Donne's commencement of his poem '':s:Goodfriday, 1613. Riding Westward'': "Let man's soul be a sphere, and then, in this, Th' intelligence that moves, devotion is;"

Anton Chekhov in his plays ''The Seagull'', ''Uncle Vanya'' and ''Three Sisters (play), Three Sisters'' describes the tortured emotional states of doctors who at some point in their careers have turned their back on conscience. In his short stories, Anton Chekhov, Chekhov also explored how people misunderstood the voice of a tortured conscience. A promiscuous student, for example, in ''The Fit'' describes it as a "dull pain, indefinite, vague; it was like anguish and the most acute fear and despair ... in his breast, under the heart" and the young doctor examining the misunderstood agony of compassion experienced by the factory owner's daughter in ''From a Case Book'' calls it an "unknown, mysterious power ... in fact close at hand and watching him." Characteristically, Chekhov's own conscience drove him on the long journey to Sakhalin to record and alleviate the harsh conditions of the prisoners at that remote outpost. As Irina Ratushinskaya writes in the introduction to that work: "Abandoning everything, he travelled to the distant island of Sakhalin, the most feared place of exile and forced labour in Russia at that time. One cannot help but wonder why? Simply, because the lot of the people there was a bitter one, because nobody really knew about the lives and deaths of the exiles, because he felt that they stood in greater need of help that anyone else. A strange reason, maybe, but not for a writer who was the epitome of all the best traditions of a Russian man of letters. Russian literature has always focused on questions of conscience and was, therefore, a powerful force in the moulding of public opinion."

E. H. Carr writes of Dostoevsky's character the young student Raskolnikov in the novel ''Crime and Punishment'' who decides to murder a 'vile and loathsome' old woman money lender on the principle of transcending conventional morals: "the sequel reveals to us not the pangs of a stricken ''conscience'' (which a less subtle writer would have given us) but the tragic and fruitless struggle of a powerful intellect to maintain a conviction which is incompatible with the essential nature of man."

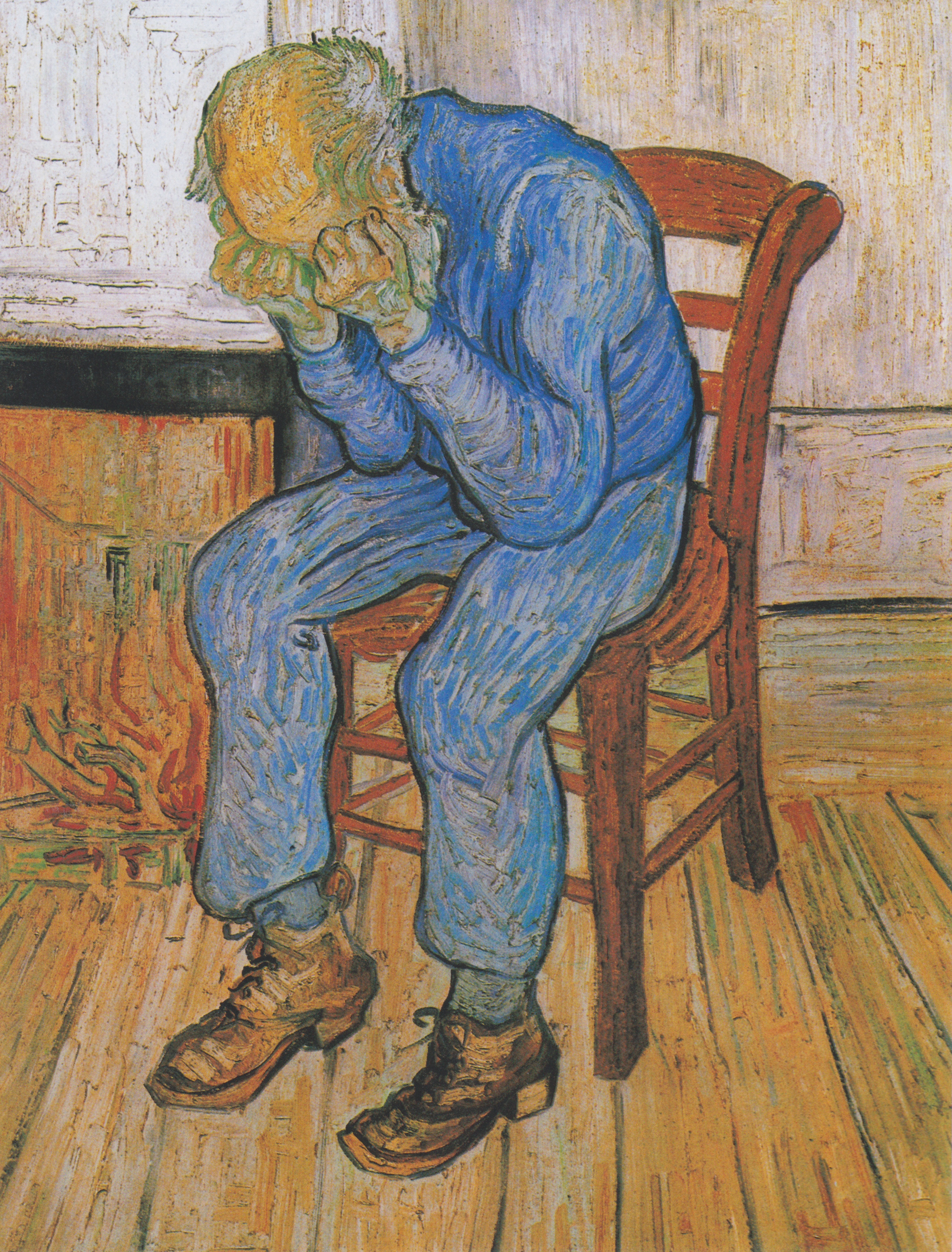

Hermann Hesse wrote his ''Siddhartha (novel), Siddhartha'' to describe how a young man in the time of the  The Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo in 1878 that "one must never let the fire in one's soul die, for the time will inevitably come when it will be needed. And he who chooses poverty for himself and loves it possesses a great treasure and will hear the voice of his conscience address him every more clearly. He who hears that voice, which is God's greatest gift, in his innermost being and follows it, finds in it a friend at last, and he is never alone! ... That is what all great men have acknowledged in their works, all those who have thought a little more deeply and searched and worked and loved a little more than the rest, who have plumbed the depths of the sea of life."

The 1957 Ingmar Bergman film ''The Seventh Seal'' portrays the journey of a medieval knight (Max von Sydow) returning disillusioned from the crusades ("what is going to happen to those of us who want to believe, but aren't able to?") across a plague (disease), plague-ridden landscape, undertaking a game of chess with the Personifications of death, personification of Death until he can perform one meaningful altruistic act of conscience (overturning the chess board to distract Death long enough for a family of jugglers to escape in their wagon).

The Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo in 1878 that "one must never let the fire in one's soul die, for the time will inevitably come when it will be needed. And he who chooses poverty for himself and loves it possesses a great treasure and will hear the voice of his conscience address him every more clearly. He who hears that voice, which is God's greatest gift, in his innermost being and follows it, finds in it a friend at last, and he is never alone! ... That is what all great men have acknowledged in their works, all those who have thought a little more deeply and searched and worked and loved a little more than the rest, who have plumbed the depths of the sea of life."

The 1957 Ingmar Bergman film ''The Seventh Seal'' portrays the journey of a medieval knight (Max von Sydow) returning disillusioned from the crusades ("what is going to happen to those of us who want to believe, but aren't able to?") across a plague (disease), plague-ridden landscape, undertaking a game of chess with the Personifications of death, personification of Death until he can perform one meaningful altruistic act of conscience (overturning the chess board to distract Death long enough for a family of jugglers to escape in their wagon).

The 1942 ''Casablanca (film), Casablanca'' centers on the development of conscience in the cynical American Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) in the face of oppression by the Nazis and the example of the resistance leader Victor Laszlo.

The David Lean and Robert Bolt screenplay for ''Doctor Zhivago (film), Doctor Zhivago'' (an adaptation of Boris Pasternak's novel) focuses strongly on the conscience of a doctor-poet in the midst of the Russian Revolution (1917), Russian Revolution (in the end "the walls of his heart were like paper").

The 1982 Ridley Scott film ''Blade Runner'' focuses on the struggles of conscience between and within a bounty hunter (Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford)) and a renegade replicant android (robot), android (Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer)) in a future society which refuses to accept that forms of artificial intelligence can have aspects of being such as conscience. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote his last great choral composition the Mass in B minor (BWV 232) to express the alternating emotions of loneliness, despair, joy and rapture that arise as ''conscience'' reflects on a departed human life. Here JS Bach's use of counterpoint and contrapuntal settings, his dynamic discourse of melodically and rhythmically distinct voices seeking forgiveness of sins ("''Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis''") evokes a spiraling moral conversation of all humanity expressing his belief that "with devotional music, God is always present in his grace".

Ludwig van Beethoven's meditations on illness, conscience and mortality in the Late String Quartets (Beethoven), Late String Quartets led to his dedicating the third movement of String Quartet in A Minor (1825) Op. 132 (see String Quartet No. 15 (Beethoven), String Quartet No. 15) as a "Hymn of Thanksgiving to God of a convalescent". John Lennon's work "Imagine (John Lennon song), Imagine" owes much of its popular appeal to its evocation of conscience against the atrocities created by war, religious fundamentalism and politics. The Beatles George Harrison-written track "The Inner Light (song), The Inner Light" sets to Indian raga music a verse from the ''Tao Te Ching'' that "without going out of your door you can know the ways of heaven'. In the 1986 movie ''The Mission (1986 film), The Mission'' the guilty conscience and penance of the slave trader Mendoza is made more poignant by the haunting oboe music of Ennio Morricone ("On Earth as it is in Heaven") The song Sweet Lullaby by Deep Forest is based on a traditional Baeggu language, Baegu lullaby from the Solomon Islands called "Rorogwela" in which a young orphan is comforted as an act of conscience by his older brother. The Dream Academy song 'Forest Fire' provided an early warning of the moral dangers of our 'black cloud' 'bringing down a different kind of weather ... letting the sunshine in, that's how the end begins."

The American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA) presents the Conscience-in-Media Award to journalists whom the society deems worthy of recognition for demonstrating "singular commitment to the highest principles of journalism at notable personal cost or sacrifice".Valk, Elizabeth P. (24 February 1992)

Johann Sebastian Bach wrote his last great choral composition the Mass in B minor (BWV 232) to express the alternating emotions of loneliness, despair, joy and rapture that arise as ''conscience'' reflects on a departed human life. Here JS Bach's use of counterpoint and contrapuntal settings, his dynamic discourse of melodically and rhythmically distinct voices seeking forgiveness of sins ("''Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis''") evokes a spiraling moral conversation of all humanity expressing his belief that "with devotional music, God is always present in his grace".

Ludwig van Beethoven's meditations on illness, conscience and mortality in the Late String Quartets (Beethoven), Late String Quartets led to his dedicating the third movement of String Quartet in A Minor (1825) Op. 132 (see String Quartet No. 15 (Beethoven), String Quartet No. 15) as a "Hymn of Thanksgiving to God of a convalescent". John Lennon's work "Imagine (John Lennon song), Imagine" owes much of its popular appeal to its evocation of conscience against the atrocities created by war, religious fundamentalism and politics. The Beatles George Harrison-written track "The Inner Light (song), The Inner Light" sets to Indian raga music a verse from the ''Tao Te Ching'' that "without going out of your door you can know the ways of heaven'. In the 1986 movie ''The Mission (1986 film), The Mission'' the guilty conscience and penance of the slave trader Mendoza is made more poignant by the haunting oboe music of Ennio Morricone ("On Earth as it is in Heaven") The song Sweet Lullaby by Deep Forest is based on a traditional Baeggu language, Baegu lullaby from the Solomon Islands called "Rorogwela" in which a young orphan is comforted as an act of conscience by his older brother. The Dream Academy song 'Forest Fire' provided an early warning of the moral dangers of our 'black cloud' 'bringing down a different kind of weather ... letting the sunshine in, that's how the end begins."

The American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA) presents the Conscience-in-Media Award to journalists whom the society deems worthy of recognition for demonstrating "singular commitment to the highest principles of journalism at notable personal cost or sacrifice".Valk, Elizabeth P. (24 February 1992)

"From the Publisher"

''Time''. Retrieved 20 October 2009. The Ambassador of Conscience Award, Amnesty International's most prestigious human rights award, takes its inspiration from a poem written by Irish Nobel prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney called "The Republic of Conscience".

A conscience is a

A conscience is a cognitive

Cognition is the "mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

process that elicits emotion

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiology, neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavior, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or suffering, displeasure. There is ...

and rational associations based on an individual's moral philosophy