Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Corinth ( ; ; ; ) was a

Cypselus was the son of

Cypselus was the son of

He ruled for thirty years and was succeeded as tyrant by his son

He ruled for thirty years and was succeeded as tyrant by his son

In

In  In 491 BC, Corinth mediated between

In 491 BC, Corinth mediated between  Herodotus, who was believed to dislike the Corinthians, mentions that they were considered the second best fighters after the Athenians.

In 458 BC, Corinth was defeated by Athens at

Herodotus, who was believed to dislike the Corinthians, mentions that they were considered the second best fighters after the Athenians.

In 458 BC, Corinth was defeated by Athens at

Corinth is mentioned many times in the

Corinth is mentioned many times in the

The city was largely destroyed in the earthquakes of AD 365 and AD 375, followed by Alaric's invasion in 396. The city was rebuilt after these disasters on a monumental scale, but covered a much smaller area than previously. Four churches were located in the city proper, another on the citadel of the

The city was largely destroyed in the earthquakes of AD 365 and AD 375, followed by Alaric's invasion in 396. The city was rebuilt after these disasters on a monumental scale, but covered a much smaller area than previously. Four churches were located in the city proper, another on the citadel of the

During the

During the

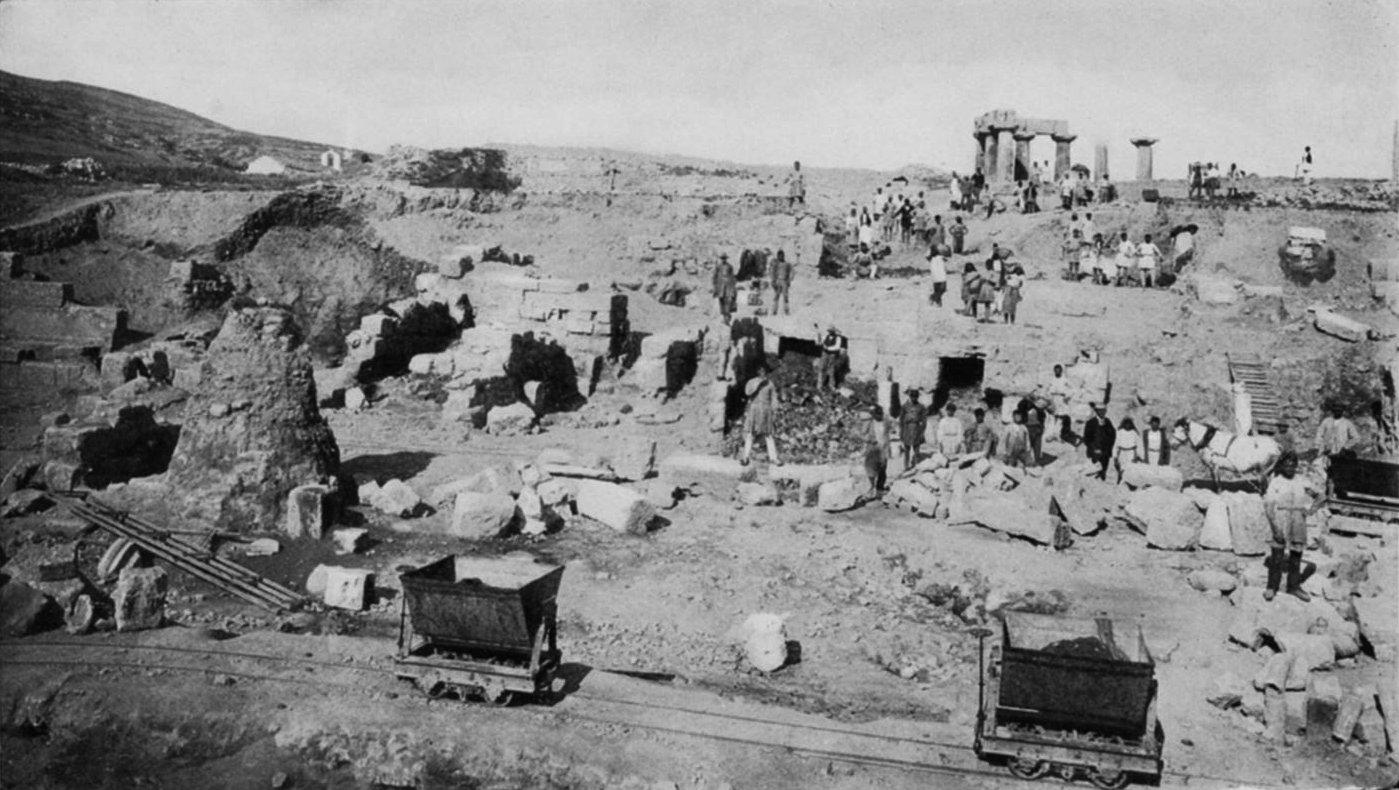

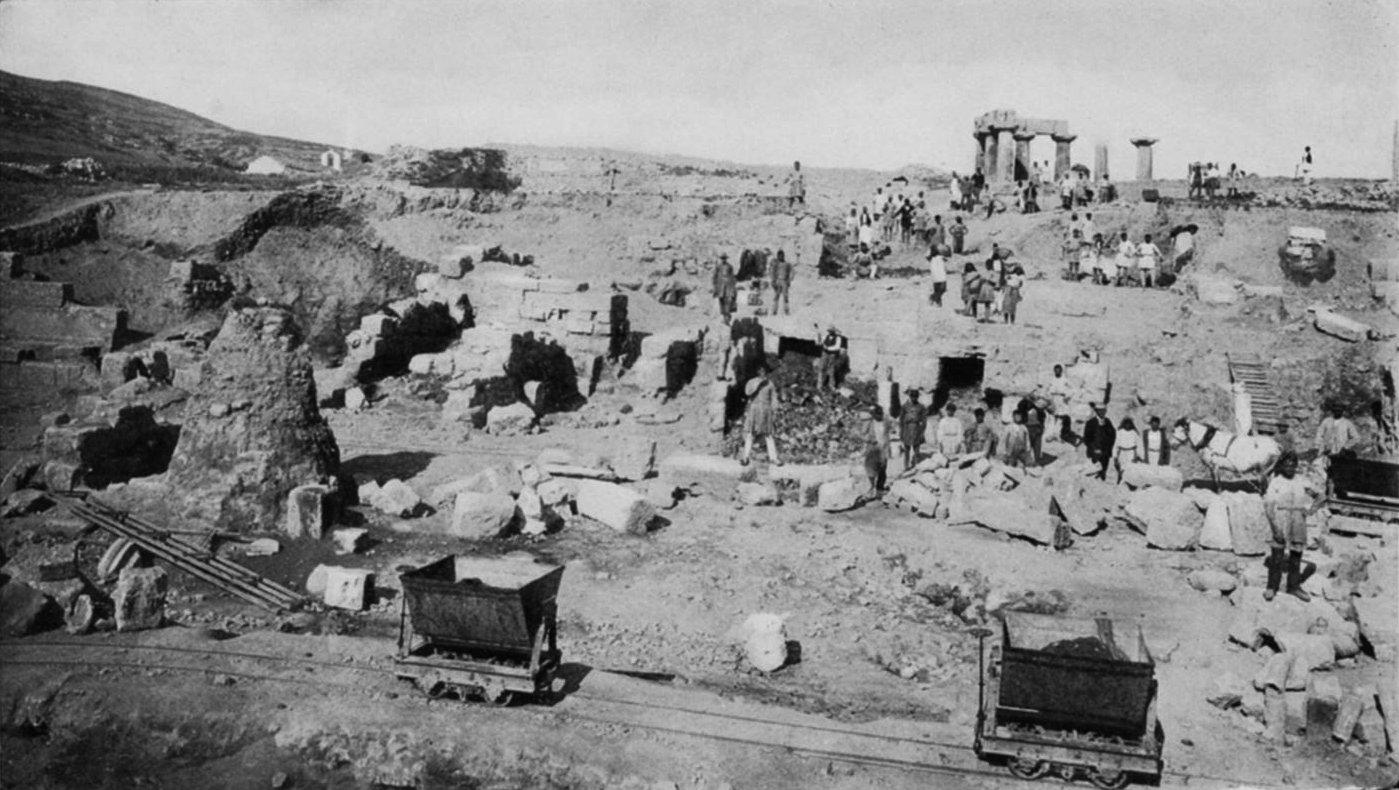

The Corinth Excavations by the

The Corinth Excavations by the

Google books

* H. N. Fowler and R. Stillwell, ''Corinth I: Introduction, Topography, Architecture'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1932. * Hammond, ''A History of Greece.'' Oxford University Press. 1967. History of Greece, including Corinth from the early civilizations (6000–850) to the splitting of the empire and Antipater's occupation of Greece (323–321). * I. Thallon-Hill and L. S. King, ''Corinth IV, i: Decorated Architectural Terracottas'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1929. * J. C. Biers, ''Corinth XVII: The Great Bath on the Lechaion Road'', Princeton 1985. * J. H. Kent, ''Corinth VIII, iii: The Inscriptions, 1926–1950'', Princeton 1966. * K. M. Edwards, ''Corinth VI: Coins, 1896–1929'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1933. * K. W. Slane, ''Corinth XVIII, ii: The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: The Roman Pottery and Lamps'', Princeton 1990. * Kagan, Donald. ''The Fall of the Athenian Empire''. New York: Cornell University Press. 1987. * M. C. Sturgeon, ''Corinth IX, ii: Sculpture: The Reliefs from the Theater'', Princeton 1977. * M. K. Risser, ''Corinth VII, v: Corinthian Conventionalizing Pottery'', Princeton 2001. * N. Bookidis and R. S. Stroud, ''Corinth XVIII, iii: The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: Topography and Architecture'', Princeton 1997. * O. Broneer, ''Corinth I, iv: The South Stoa and Its Roman Successor''s, Princeton 1954. * O. Broneer, ''Corinth IV, ii: Terracotta Lamps'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1930. * O. Broneer, ''Corinth X: The Odeum'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1932. * Partial text from Easton's Bible Dictionary, 1897 * R. Carpenter and A. Bon, ''Corinth III, ii: The Defenses of Acrocorinth and the Lower Town'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1936. * R. L. Scranton, ''Corinth I, iii: Monuments in the Lower Agora and North of the Archaic Temple'', Princeton 1951. * R. L. Scranton, ''Corinth XVI: Mediaeval Architecture in the Central Area of Corinth'', Princeton 1957. * R. Stillwell, ''Corinth II: The Theatre'', Princeton 1952. * R. Stillwell, R. L. Scranton, and S. E. Freeman, ''Corinth I, ii: Architectur''e, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1941. * Results of the American School of Classical Studies Corinth Excavations published in Corinth Volumes I to XX, Princeton. * Romano, David Gilman. ''Athletics and Mathematics in Archaic Corinth: the Origins of the Greek Stadion.'' Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 206. 1993. * S. Herbert, ''Corinth VII, iv: The Red-Figure Pottery'', Princeton 1977. * S. S. Weinberg, ''Corinth I, v: The Southeast Building, The Twin Basilicas, The Mosaic House'', Princeton 1960. * S. S. Weinberg, ''Corinth VII, i: The Geometric and Orientalizing Pottery'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1943. * Salmon, J. B. ''Wealthy Corinth: A History of the City to 338 BC''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1984. * Scahill, David. The Origins of the Corinthian Capital. In ''Structure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek World.'' Edited by Peter Schultz and Ralf von den Hoff, 40–53. Oxford: Oxbow. 2009. * see also

Ancient Corinth – The Complete Guide

Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Fortress of Acrocorinth

Excavations at Ancient Corinth

(American School of Classical Studies at Athens)

ASCSA.net

Online archaeological databases of the Corinth Excavations

Coins of Ancient Corinth (Greek)

Coins of Ancient Corinth under the Romans

Corinthian Matters

a blog whose subject is Corinthian Archaeology

American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Corinth Excavations of the ASCSA

GIS data and Maps for Corinth and Greece

{{DEFAULTSORT:Corinth (Ancient Greece) 7th-century BC establishments in Greece Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Peloponnese (region) Greek city-states Pauline churches Populated places in ancient Corinthia Principality of Achaea Roman sites in Greece 4th-century BC disestablishments in Greece

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

(''polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

'') on the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

, the narrow stretch of land that joins the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

peninsula to the mainland of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, roughly halfway between Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

. The modern city of Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

is located approximately northeast of the ancient ruins. Since 1896, systematic archaeological investigations of the Corinth Excavations

Corinth ( ; ; ; ) was a city-state (''polis'') on the Isthmus of Corinth, the narrow stretch of land that joins the Peloponnese peninsula to the mainland of Greece, roughly halfway between Athens and Sparta. The modern city of Corinth is l ...

by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA; ) is one of 19 foreign archaeological institutes in Athens, Greece.

It is a member of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers (CAORC). CAORC is a private not-for-profit federat ...

have revealed large parts of the ancient city, and recent excavations conducted by the Greek Ministry of Culture have brought to light important new facets of antiquity.

For Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

, Corinth is well known from the two letters from Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

in the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

, the First Epistle to the Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians () is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author, Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church i ...

and the Second Epistle to the Corinthians

The Second Epistle to the Corinthians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author named Saint Timothy, Timothy, and is addressed to the church in Ancient Corin ...

. Corinth is also mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

as part of Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

's missionary travels. In addition, the second book of Pausanias' ''Description of Greece

''Description of Greece'' () is the only surviving work by the ancient "geographer" or tourist Pausanias (geographer), Pausanias (c. 110 – c. 180).

Pausanias' ''Description of Greece'' comprises ten books, each of them dedicated to some ...

'' is devoted to Corinth.

Ancient Corinth was one of the largest and most important cities of Greece, with a population of 90,000 in 400 BC. The Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

demolished Corinth in 146 BC, built a new city in its place in 44 BC, and later made it the provincial capital of Greece.

History

Prehistory and founding myths

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

pottery suggests that the site of Corinth was occupied from at least as early as 6500 BC, and continually occupied into the Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, when, it has been suggested, the settlement acted as a centre of trade. However, there is a huge drop in ceramic remains during the Early Helladic II phase and only sparse ceramic remains in the EHIII and MH phases; thus, it appears that the area was very sparsely inhabited in the period immediately before the Mycenaean period

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainla ...

. There was a settlement on the coast near Lechaio

Lechaio () is a village in the municipal unit of Assos-Lechaio in Corinthia, Greece. It is situated on the coast of the Gulf of Corinth, 8 km west of Corinth and 12 km southeast of Kiato. The Greek National Road 8 passes through the town ...

n which traded across the Corinthian Gulf; the site of Corinth itself was likely not heavily occupied again until around 900 BC, when it is believed that the Dorians

The Dorians (; , , singular , ) were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Greeks, Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans (tribe), Achaeans, and Ionians). They are almost alw ...

settled there.

According to Corinthian myth as reported by Pausanias, the city was founded by Corinthos, a descendant of the god Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

. However, other myths hold that it was founded by the goddess Ephyra, a daughter of the Titan

Titan most often refers to:

* Titan (moon), the largest moon of Saturn

* Titans, a race of deities in Greek mythology

Titan or Titans may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Fictional entities

Fictional locations

* Titan in fiction, fictiona ...

Oceanus

In Greek mythology, Oceanus ( ; , also , , or ) was a Titans, Titan son of Uranus (mythology), Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethys (mythology), Tethys, and the father of the River gods (Greek mythology), river gods ...

, thus the ancient name of the city (also Ephyra).

It seems likely that Corinth was also the site of a Bronze Age Mycenaean palace-city, like Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

, Tiryns

Tiryns ( or ; Ancient Greek: Τίρυνς; Modern Greek: Τίρυνθα) is a Mycenaean archaeological site in Argolis in the Peloponnese, and the location from which the mythical hero Heracles was said to have performed his Twelve Labours. It ...

, or Pylos

Pylos (, ; ), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of ...

. According to myth, Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος ''Sísyphos'') was the founder and king of Ancient Corinth, Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He reveals Zeus's abduction of Aegina (mythology), Aegina to the river god As ...

was the founder of a race of ancient kings at Corinth. It was also in Corinth that Jason

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece is featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Med ...

, the leader of the Argonauts

The Argonauts ( ; ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, ''Argo'', named after it ...

, abandoned Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; ; ) is the daughter of Aeëtes, King Aeëtes of Colchis. Medea is known in most stories as a sorceress, an accomplished "wiktionary:φαρμακεία, pharmakeía" (medicinal magic), and is often depicted as a high- ...

. The Catalogue of Ships

The Catalogue of Ships (, ''neōn katálogos'') is an epic catalogue in Book 2 of Homer's ''Iliad'' (2.494–759), which lists the contingents of the Achaean army that sailed to Troy. The catalogue gives the names of the leaders of each conting ...

in the Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

lists the Corinthians amid the contingent fighting in the Trojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

under the leadership of Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans during the Trojan War. He was the son (or grandson) of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of C ...

.

In a Corinthian myth recounted to Pausanias in the 2nd century AD, Briareus, one of the Hecatonchires

In Greek mythology, the Hecatoncheires (), also called Hundred-Handers or Centimanes (; ), were three monstrous giants, of enormous size and strength, each with fifty heads and one hundred arms. They were individually named Cottus (the furious), ...

, was the arbitrator in a dispute between Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

and Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; ; Homeric Greek: ) is the god who personification, personifies the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion ("the one above") an ...

, respectively gods of the sea and the sun. His verdict was that the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

, the area closest to the sea, belonged to Poseidon, and the acropolis of Corinth (Acrocorinth

Acrocorinth (, 'Upper Corinth' or 'the acropolis of ancient Corinth') is a monolithic rock overlooking the ancient city of Corinth, Greece. In the estimation of George Forrest, "It is the most impressive of the acropolis of mainland Greece."

W ...

), closest to the sky, belonged to Helios.

The Upper Peirene spring is located within the walls of the acropolis. Pausanias (2.5.1) says that it was put there by Asopus

Asopus (; ''Āsōpos'') is the name of four different rivers in Greece and one in Turkey. In Greek mythology, it was also the name of the God (male deity), gods of those rivers. Zeus carried off Aegina (mythology), Aegina, Asopus' daughter, and ...

, repaying Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος ''Sísyphos'') was the founder and king of Ancient Corinth, Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He reveals Zeus's abduction of Aegina (mythology), Aegina to the river god As ...

for information about the abduction of Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

by Zeus. According to legend, the winged horse Pegasus

Pegasus (; ) is a winged horse in Greek mythology, usually depicted as a white stallion. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as horse-god, and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa. Pegasus was the brother of Chrysaor, both born from Medusa's blood w ...

drank at the spring, and was captured and tamed by the Corinthian hero Bellerophon

Bellerophon or Bellerophontes (; ; lit. "slayer of Belleros") or Hipponous (; lit. "horse-knower"), was a divine Corinthian hero of Greek mythology, the son of Poseidon and Eurynome, and the foster son of Glaukos. He was "the greatest her ...

.

Corinth under the Bacchiadae

Corinth had been a backwater in Greece in the 8th century BC. TheBacchiadae

The Bacchiadae ( ''Bakkhiadai''), a tightly knit Doric clan, were the ruling family of ancient Corinth in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE, a period of Corinthian cultural power.

History

Corinth had been a backwater in eighth-century Greece ...

(, ) were a tightly-knit Doric clan and the ruling kinship group of archaic Corinth in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, a period of expanding Corinthian cultural power. In 747 BC (a traditional date), an aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

ousted the Bacchiadai Prytaneis and reinstituted the kingship, about the time the Kingdom of Lydia (the endonymic

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

''Basileia Sfard'') was at its greatest, coinciding with the ascent of Basileus Meles, King of Lydia. The Bacchiadae, numbering perhaps a couple of hundred adult males, took power from the last king Telestes (from the House of Sisyphos

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος ''Sísyphos'') was the founder and king of Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He reveals Zeus's abduction of Aegina to the river god Asopus, thereby incurring Zeus's wrath ...

) in Corinth. The Bacchiads dispensed with kingship and ruled as a group, governing the city by annually electing a ''prytanis

The ''prytaneis'' (πρυτάνεις; sing.: πρύτανις ''prytanis'') were the executives of the '' boule'' of Ancient Athens. They served in a prytaneion.

Origins

When Cleisthenes reorganized the Athenian government in 508/7 BCE, he rep ...

'' (who held the kingly position for his brief term), probably a council (though none is specifically documented in the scant literary materials), and a ''polemarch

A polemarch (, from , ''polémarchos'') was a senior military title in various ancient Greek city states ('' poleis''). The title is derived from the words '' polemos'' ('war') and ''archon'' ('ruler, leader') and translates as 'warleader' or 'wa ...

os'' to head the army.

During Bacchiad rule from 747 to 650 BC, Corinth became a unified state. Large scale public buildings and monuments were constructed at this time. In 733 BC, Corinth established colonies at Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

and Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

. By 730 BC, Corinth emerged as a highly advanced Greek city with at least 5,000 people.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

tells the story of Philolaus of Corinth, a Bacchiad who was a lawgiver at Thebes. He became the lover of Diocles, the winner of the Olympic games. They both lived for the rest of their lives in Thebes. Their tombs were built near one another and Philolaus' tomb points toward the Corinthian country, while Diocles' faces away.

In 657 BC, polemarch Cypselus

Cypselus (, ''Kypselos'') was the first tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC.

With increased wealth and more complicated trade relations and social structures, Greek city-states tended to overthrow their traditional hereditary priest-kings; ...

obtained an oracle from Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

which he interpreted to mean that he should rule the city.

He seized power and exiled the Bacchiadae.

Corinth under the tyrants

Cypselus

Cypselus (, ''Kypselos'') was the first tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC.

With increased wealth and more complicated trade relations and social structures, Greek city-states tended to overthrow their traditional hereditary priest-kings; ...

(, ) was the first tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

of Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

in the 7th century BC. From 658–628 BC, he removed the Bacchiad aristocracy from power and ruled for three decades. He built temples to Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

and Poseidon in 650 BC.

Cypselus was the son of

Cypselus was the son of Eëtion

In Greek mythology, Eëtion or Eetion (; ) is the king of the Anatolian city of Cilician Thebe. He is said to be the father of Andromache, the wife of the Trojan prince Hector. In the sixth book of the ''Iliad'', Andromache tells her husband th ...

and a disfigured woman named Labda. He was a member of the Bacchiad kin and usurped the power in archaic matriarchal right of his mother. According to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, the Bacchiadae heard two prophecies from the Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

c oracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

that the son of Eëtion

In Greek mythology, Eëtion or Eetion (; ) is the king of the Anatolian city of Cilician Thebe. He is said to be the father of Andromache, the wife of the Trojan prince Hector. In the sixth book of the ''Iliad'', Andromache tells her husband th ...

would overthrow their dynasty, and they planned to kill the baby once he was born. However, the newborn smiled at each of the men sent to kill him, and none of them could bear to strike the blow.

Labda then hid the baby in a chest, and the men could not find him once they had composed themselves and returned to kill him. (Compare the infancy of Perseus

In Greek mythology, Perseus (, ; Greek language, Greek: Περσεύς, Romanization of Greek, translit. Perseús) is the legendary founder of the Perseid dynasty. He was, alongside Cadmus and Bellerophon, the greatest Greek hero and slayer of ...

.) The ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

chest of Cypselus was richly worked and adorned with gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

. It was a votive offering at Olympia, where Pausanias gave it a minute description in his 2nd century AD travel guide.

Cypselus grew up and fulfilled the prophecy. Corinth had been involved in wars with Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

* Argus (Greek myth), several characters in Greek mythology

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer in the United Kingdom

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

and Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, and the Corinthians were unhappy with their rulers. Cypselus was polemarch

A polemarch (, from , ''polémarchos'') was a senior military title in various ancient Greek city states ('' poleis''). The title is derived from the words '' polemos'' ('war') and ''archon'' ('ruler, leader') and translates as 'warleader' or 'wa ...

at the time (around 657 BC), the archon

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

in charge of the military, and he used his influence with the soldiers to expel the king. He also expelled his other enemies, but allowed them to set up colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

in northwestern Greece.

He also increased trade with the colonies in Italy and Sicily. He was a popular ruler and, unlike many later tyrants, he did not need a bodyguard and died a natural death. Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

reports that "Cypselus of Corinth had made a vow that if he became master of the city, he would offer to Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

the entire property of the Corinthians. Accordingly, he commanded them to make a return of their possessions."

The city sent forth colonists to found new settlements in the 7th century BC, under the rule of Cypselus (r. 657–627 BC) and his son Periander

Periander (; ; died c. 585 BC) was the second tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. Periander's rule brought about a prosperous time in Corinth's history, as his administrative skill made Corinth one of the wealthiest city ...

(r. 627–587 BC). Those settlements were Epidamnus

Epidamnos ''(Ancient Greek: Επίδαμνος, Albanian: Epidamn)'', later known as Dyrrachium ''(Latin: Dyrrhachium, Greek: Δυρράχιον, Albanian: Dyrrah)'', was a prominent city on the Adriatic coast, located in modern-day Durrës, Alb ...

(modern day Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the List of cities and towns in Albania#List, second most populous city of the Albania, Republic of Albania and county seat, seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is one of Albania's oldest ...

, Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

), Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

, Ambracia

Ambracia (; , occasionally , ''Ampracia'') was a city of ancient Greece on the site of modern Arta. It was founded by the Corinthians in 625 BC and was situated about from the Ambracian Gulf, on a bend of the navigable river Arachthos (or ...

, Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

(modern day town of Corfu), and Anactorium

Anactorium or Anaktorion () was a town in ancient Acarnania, situated on the promontory on the Ambraciot Gulf. On entering the Ambraciot Gulf from the Ionian Sea it was the first town in Acarnania after Actium, from which it was distant 40 stad ...

. Periander also founded Apollonia in Illyria (modern day Fier

Fier (; sq-definite, Fieri, Latin: ''Fierum'') is the seventh most populous city of the Republic of Albania and seat of Fier County and Fier Municipality. It is situated on the bank of Gjanica River in the Myzeqe Plain between the Seman in ...

, Albania) and Potidaea

__NOTOC__

Potidaea (; , ''Potidaia'', also Ποτείδαια, ''Poteidaia'') was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, Chalcidice, Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas at t ...

(in Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; , alternatively Halkidiki), also known as Chalcidice, is a peninsula and regional units of Greece, regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedon ...

). Corinth was also one of the nine Greek sponsor-cities to found the colony of Naukratis

Naucratis or Naukratis (Ancient Greek: , "Naval Command"; Egyptian language, Egyptian: , , , Coptic language, Coptic: ) was a city and trading-post in ancient Egypt, located on the Canopus, Egypt, Canopic (western-most) branch of the Nile river, ...

in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, founded to accommodate the increasing trade volume between the Greek world and pharaonic Egypt during the reign of Pharaoh Psammetichus I

Wahibre Psamtik I (Ancient Egyptian: ) was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Saite period, ruling from the city of Sais, Egypt, Sais in the Nile delta between 664 and 610 BC. He was installed by Ashurbanipal of the Neo- ...

of the 26th Dynasty

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXVI, alternatively 26th Dynasty or Dynasty 26) was the last native dynasty of ancient Egypt before the Persian conquest in 525 BC (although other brief periods of rule by Egyptians followed). T ...

.

He ruled for thirty years and was succeeded as tyrant by his son

He ruled for thirty years and was succeeded as tyrant by his son Periander

Periander (; ; died c. 585 BC) was the second tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. Periander's rule brought about a prosperous time in Corinth's history, as his administrative skill made Corinth one of the wealthiest city ...

in 627 BC. The treasury that Cypselus built at Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

was apparently still standing in the time of Herodotus, and the chest of Cypselus

Cypselus (, ''Kypselos'') was the first tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC.

With increased wealth and more complicated trade relations and social structures, Greek city-states tended to overthrow their traditional hereditary priest-kings; C ...

was seen by Pausanias at Olympia in the 2nd century AD. Periander

Periander (; ; died c. 585 BC) was the second tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. Periander's rule brought about a prosperous time in Corinth's history, as his administrative skill made Corinth one of the wealthiest city ...

brought Corcyra to order in 600 BC.

Periander

Periander (; ; died c. 585 BC) was the second tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. Periander's rule brought about a prosperous time in Corinth's history, as his administrative skill made Corinth one of the wealthiest city ...

was considered one of the Seven Wise Men of Greece

The Seven Sages or Seven Wise Men was the title given to seven philosophers, statesmen, and law-givers of the 7th–6th centuries BCE who were renowned for their wisdom.

The Seven Sages

The list of the seven sages given in Plato's '' Protag ...

. During his reign, the first Corinthian coins

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

were struck. He was the first to attempt to cut across the Isthmus to create a seaway between the Corinthian and the Saronic Gulfs. He abandoned the venture due to the extreme technical difficulties that he met, but he created the Diolkos

The Diolkos (, from the Greek , "across", and , "portage machine") was a paved trackway near Corinth in Ancient Greece which enabled boats to be moved overland across the Isthmus of Corinth. The shortcut allowed ancient vessels to avoid the ...

instead (a stone-built overland ramp). The era of the Cypselids was Corinth's golden age, and ended with Periander's nephew , named after the hellenophile Egyptian Pharaoh Psammetichus I (see above).

Periander killed his wife Melissa. His son Lycophron found out and shunned him, and Periander exiled the son to Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

. Periander later wanted Lycophron to replace him as ruler of Corinth, and convinced him to come home to Corinth on the condition that Periander go to Corcyra. The Corcyreans heard about this and killed Lycophron to keep away Periander.

Corinth after the tyrants

581 BC: Periander's nephew and successor was assassinated, ending the tyranny. 581 BC: theIsthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year be ...

were established by leading families.

570 BC: the inhabitants started to use silver coins called 'colts' or 'foals'.

550 BC: Construction of the Temple of Apollo at Corinth (early third quarter of the 6th century BC).

550 BC: Corinth allied with Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

.

525 BC: Corinth formed a conciliatory alliance with Sparta against Argos.

519 BC: Corinth mediated between Athens and Thebes.

Around 500 BC: Athenians and Corinthians entreated Spartans not to harm Athens by restoring the tyrant.

Just before the classical period, according to Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

, the Corinthians developed the trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

which became the standard warship of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

until the late Roman period. Corinth fought the first naval battle on record against the Hellenic city of Corcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

.Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

1:13 The Corinthians were also known for their wealth due to their strategic location on the isthmus, through which all land traffic had to pass en route to the Peloponnese, including messengers and traders.

Classical Corinth

In

In classical times

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

, Corinth rivaled Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Thebes in wealth, based on the Isthmian traffic and trade. Until the mid-6th century, Corinth was a major exporter of black-figure pottery

Black-figure pottery painting (also known as black-figure style or black-figure ceramic; ) is one of the styles of Ancient Greek vase painting, painting on pottery of ancient Greece, antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th a ...

to city-states around the Greek world, later losing their market to Athenian artisans.

In classical times

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

and earlier, Corinth had a temple of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, employing some thousand hetairas (temple prostitutes) (see also Temple prostitution in Corinth). The city was renowned for these temple prostitutes, who served the wealthy merchants and the powerful officials who frequented the city. Lais, the most famous hetaira, was said to charge tremendous fees for her extraordinary favours. Referring to the city's exorbitant luxuries, Horace is quoted as saying: "" ("not everyone is able to go to Corinth").

Corinth was also the host of the Isthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year be ...

. During this era, Corinthians developed the Corinthian order

The Corinthian order (, ''Korinthiakós rythmós''; ) is the last developed and most ornate of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Ancient Roman architecture, Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric or ...

, the third main style of classical architecture after the Doric and the Ionic. The Corinthian order was the most complicated of the three, showing the city's wealth and the luxurious lifestyle, while the Doric order evoked the rigorous simplicity of the Spartans, and the Ionic was a harmonious balance between these two following the cosmopolitan philosophy of Ionians like the Athenians.

The city had two main ports: to the west on the Corinthian Gulf lay Lechaio

Lechaio () is a village in the municipal unit of Assos-Lechaio in Corinthia, Greece. It is situated on the coast of the Gulf of Corinth, 8 km west of Corinth and 12 km southeast of Kiato. The Greek National Road 8 passes through the town ...

n, which connected the city to its western colonies (Greek: apoikiai

Greek colonisation refers to the expansion of Archaic Greeks, particularly during the 8th–6th centuries BC, across the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea.

The Archaic expansion differed from the Iron Age migrations of the Greek Dark Ages ...

) and Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

, while to the east on the Saronic Gulf the port of Kenchreai

Kechries (, rarely Κεχρεές) is a village in the municipality of Corinth in Corinthia in Greece, part of the community of Xylokeriza. Population 319 (2021). It takes its name from the ancient port town Kenchreai or Cenchreae (), which was s ...

served the ships coming from Athens, Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. Both ports had docks for the city's large navy.

In 491 BC, Corinth mediated between

In 491 BC, Corinth mediated between Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

and Gela

Gela (Sicilian and ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the regional autonomy, Autonomous Region of Sicily, Italy; in terms of area and population, it is the largest municipality on the southern coast of Sicily. Gela is part of the Province o ...

in Sicily.

During the years 481–480 BC, the Conference at the Isthmus of Corinth (following conferences at Sparta) established the Hellenic League, which allied under the Spartans to fight the war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

against Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. The city was a major participant in the Persian Wars, sending 400 soldiers to defend Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

and supplying forty warships for the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a victory for the outnumbered Greeks.

The battle was fou ...

under Adeimantos and 5,000 hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldi ...

with their characteristic Corinthian helmet

The Corinthian helmet originated in ancient Greece and took its name from the city-state of Corinth. It was a helmet made of bronze which in its later styles covered the entire head and neck, with slits for the eyes and mouth. A large curved pro ...

s) in the following Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Polis, Greek city-states (including Sparta, Cla ...

. The Greeks obtained the surrender of Theban collaborators with the Persians. Pausanias took them to Corinth where they were put to death.

Following the Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Empire, Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Polis, Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting over the course of three days, it wa ...

and the subsequent Battle of Artemisium

The Battle of Artemisium or Artemision was a series of naval engagements over three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle took place simultaneously with the land battle at Thermopylae, in August or September 480 BC, off t ...

, which resulted in the captures of Euboea

Euboea ( ; , ), also known by its modern spelling Evia ( ; , ), is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete, and the sixth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by ...

, Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

, and Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

, the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Polis, Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world ...

were at a point where now most of mainland Greece to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

had been overrun.

Herodotus, who was believed to dislike the Corinthians, mentions that they were considered the second best fighters after the Athenians.

In 458 BC, Corinth was defeated by Athens at

Herodotus, who was believed to dislike the Corinthians, mentions that they were considered the second best fighters after the Athenians.

In 458 BC, Corinth was defeated by Athens at Megara

Megara (; , ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

.

Peloponnesian War

In 435 BC, Corinth and its colonyCorcyra

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

went to war over Epidamnus

Epidamnos ''(Ancient Greek: Επίδαμνος, Albanian: Epidamn)'', later known as Dyrrachium ''(Latin: Dyrrhachium, Greek: Δυρράχιον, Albanian: Dyrrah)'', was a prominent city on the Adriatic coast, located in modern-day Durrës, Alb ...

. In 433 BC, Athens allied with Corcyra against Corinth. The Corinthian war against the Corcyrans was the largest naval battle between Greek city states until that time. In 431 BC, one of the factors leading to the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

was the dispute between Corinth and Athens over Corcyra, which possibly stemmed from the traditional trade rivalry between the two cities or, as Thucydides relates – the dispute over the colony of Epidamnus.

The Syracusans sent envoys to Corinth and Sparta to seek allies against Athenian invasion. The Corinthians "voted at once to aid he Syracusansheart and soul".Thucydides, Book 6.88 The Corinthians also sent a group to Lacedaemon to rouse Spartan assistance. After a convincing speech from the Athenian renegade Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

, the Spartans agreed to send troops to aid the Sicilians.

In 404 BC, Sparta refused to destroy Athens, angering the Corinthians. Corinth joined Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

* Argus (Greek myth), several characters in Greek mythology

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer in the United Kingdom

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

, and Athens against Sparta in the Corinthian War

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Greece, Thebes, Classical Athens, Athens, Ancient Corinth, Corinth and Argos, Peloponnese, Argos, backe ...

.

Demosthenes later used this history in a plea for magnanimous statecraft, noting that the Athenians of yesteryear had had good reason to hate the Corinthians and Thebans for their conduct during the Peloponnesian War, yet they bore no malice whatever.

Corinthian War

In 395 BC, after the end of the Peloponnesian War, Corinth and Thebes, dissatisfied with the hegemony of their Spartan allies, moved to support Athens against Sparta in theCorinthian War

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Greece, Thebes, Classical Athens, Athens, Ancient Corinth, Corinth and Argos, Peloponnese, Argos, backe ...

.

As an example of facing danger with knowledge, Aristotle used the example of the Argives who were forced to confront the Spartans in the battle at the Long Walls of Corinth

Long may refer to:

Measurement

* Long, characteristic of something of great duration

* Long, characteristic of something of great length

* Longitude (abbreviation: long.), a geographic coordinate

* Longa (music), note value in early music mensu ...

in 392 BC.

379–323 BC

In 379 BC, Corinth, switching back to thePeloponnesian League

The Peloponnesian League () was an alliance of ancient Greek city-states, dominated by Sparta and centred on the Peloponnese, which lasted from c. 550 to 366 BC. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War (431–4 ...

, joined Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

in an attempt to defeat Thebes and eventually take over Athens.

In 366 BC, the Athenian Assembly

The ecclesia or ekklesia () was the assembly of the citizens in city-states of ancient Greece.

The ekklesia of Athens

The ekklesia of ancient Athens is particularly well-known. It was the popular assembly, open to all male citizens as soon a ...

ordered Chares to occupy the Athenian ally and install a democratic government. This failed when Corinth, Phlius and Epidaurus allied with Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

.

Demosthenes recounts how Athens had fought the Spartans in a great battle near Corinth. The city decided not to harbor the defeated Athenian troops, but instead sent heralds to the Spartans. But the Corinthian heralds opened their gates to the defeated Athenians and saved them. Demosthenes notes that they “chose along with you, who had been engaged in battle, to suffer whatever might betide, rather than without you to enjoy a safety that involved no danger.”

These conflicts further weakened the city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

of the Peloponnese and set the stage for the conquests of Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

.

Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

warned that Philip's military force exceeded that of Athens and thus they must develop a tactical advantage. He noted the importance of a citizen army as opposed to a mercenary force, citing the mercenaries of Corinth who fought alongside citizens and defeated the Spartans.

In 338 BC, after having defeated Athens and its allies, Philip II created the League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (, ''koinòn tõn Hellḗnōn''; or simply , ''the Héllēnes''), was a federation of Greek states created by Philip IIDiodorus Siculus, Book 16, 89. «διόπερ ἐν Κορί� ...

to unite Greece (included Corinth and Macedonia) in the war against Persia. Philip was named hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' ...

of the League.

In the spring of 337 BC, the Second congress of Corinth established the Common Peace

The idea of the Common Peace (Κοινὴ Εἰρήνη, ''Koinē Eirēnē'') was one of the most influential concepts of 4th century BC Greek political thought, along with the idea of Panhellenism. The term described both the concept of a desirab ...

.

Hellenistic period

By 332 BC,Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

was in control of Greece, as hegemon.

During the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, Corinth, like many other Greece cities, never quite had autonomy. Under the successors of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, Greece was contested ground, and Corinth was occasionally the battleground for contests between the Antigonids, based in Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, and other Hellenistic powers. In 308 BC, the city was captured from the Antigonids by Ptolemy I, who claimed to come as a liberator of Greece from the Antigonids. However, the city was recaptured by Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinization of names, Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male name, male Greek given names, given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, ...

in 304 BC.

Corinth remained under Antigonid control for half a century. After 280 BC, it was ruled by the faithful governor Craterus

Craterus, also spelled Krateros (; 370 BC – 321 BC), was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. Throughout his life, he was a loyal royalist and supporter of Alexander the Great.Anson, Edward M. (2014)p.24 ...

; but, in 253/2 BC, his son Alexander of Corinth

Alexander () (died 247 BC) was a Macedonian governor and tyrant of Corinth. He was the son of Craterus who had faithfully governed Corinth and Chalcis for his half-brother Antigonus II Gonatas. His grandmother was Phila, the celebrated daughter ...

, moved by Ptolemaic Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

*Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining t ...

subsidies, resolved to challenge the Macedonian supremacy and seek independence as a tyrant. He was probably poisoned in 247 BC; after his death, the Macedonian king Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas (, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian Greek ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for his victory over the Gauls who had inv ...

retook the city in the winter of 245/44 BC.

The Macedonian rule was short-lived. In 243 BC, Aratus of Sicyon

Aratus of Sicyon (Ancient Greek: Ἄρατος ὁ Σικυώνιος; 271–213 BC) was a politician and military commander of Hellenistic period, Hellenistic Ancient Greece, Greece. He was elected strategos of the Achaean League 17 times, lead ...

, using a surprise attack, captured the fortress of Acrocorinth and convinced the citizenship to join the Achaean League

The Achaean League () was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era confederation of polis, Greek city-states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea (ancient region), Achaea in the northwestern Pelopon ...

.

Thanks to an alliance agreement with Aratus, the Macedonians recovered Corinth once again in 224 BC; but, after the Roman intervention in 197 BC, the city was permanently brought into the Achaean League. Under the leadership of Philopoemen

Philopoemen ( ''Philopoímēn''; 253 BC, Megalopolis – 183 BC, Messene) was a skilled Greek general and statesman, who was Achaean strategos on eight occasions.

From the time he was appointed as strategos in 209 BC, Philopoemen helped turn ...

, the Achaeans went on to take control of the entire Peloponnesus and made Corinth the capital of their confederation.

Classical Roman era

Roman occupation and development

In 146 BC, Rome declaredwar

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

on the Achaean League. A series of Roman victories culminated in the Battle of Corinth, after which the army of Lucius Mummius

Lucius Mummius (2nd century BC) was a Roman statesman and general. He was consul in the year 146 BC along with Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus.

Mummius was the first of his family to rise to the rank of consul thereby making him a novus homo. He r ...

besieged, captured, and burned the city. Mummius killed all the men and sold the women and children into slavery; he was subsequently given the cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; : ''cognomina''; from ''co-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became hereditar ...

as the conqueror of the Achaean League. There is archeological evidence of some minimal habitation in the years afterwards, but Corinth remained largely deserted until Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

refounded the city as ("colony of Corinth in honour of Julius") in 44 BC, shortly before his assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

. At this time, an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (American English, U.S. English: amphitheater) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ('), meani ...

was built ().

Under the Romans, Corinth was rebuilt as a major city in Southern Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

or Achaia

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaḯa'', ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. The ...

. It had a large mixed population of Romans, Greeks, and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. The city was an important locus for activities of The Roman Imperial Cult, and both Temple E and the Julian Basilica have been suggested as locations of imperial cult activity.

New Testament Corinth

Corinth is mentioned many times in the

Corinth is mentioned many times in the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

, largely in connection with Paul the Apostle's mission there, testifying to the success of Caesar's refounding of the city. Traditionally, the Church of Corinth is believed to have been founded by Paul, making it an Apostolic See

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism, the phrase "The Apostolic See" when capitalized refers specifically to the See of ...

.

The apostle Paul first visited the city in AD 49 or 50, when Gallio, the brother of Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People, fictional characters and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

:

:* Seneca the Elder (c. 54 BC – c. AD 39), a Roman rhetorician, writer and father ...

, was proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

of Achaia. Paul resided here for eighteen months (see ). Here he first became acquainted with Priscilla and Aquila

Priscilla and Aquila were a first-century Christian missionary married couple described in the New Testament. Aquila is traditionally listed among the Seventy Disciples. They lived, worked, and traveled with the Apostle Paul, who described them ...

, with whom he later traveled. They worked here together as tentmakers (from which is derived the modern Christian concept of tentmaking

Tentmaking, in general, refers to the activities of any Christian who, while dedicating herself or himself to the ministry of the Gospel, receives little or no pay for Church work, but performs other ("tentmaking") jobs to provide support. Spec ...

), and regularly attended the synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

.

In AD 51/52, Gallio presided over the trial of the Apostle Paul in Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

. Silas

Silas or Silvanus (; Greek: Σίλας/Σιλουανός; fl. 1st century AD) was a leading member of the Early Christian community, who according to the New Testament accompanied Paul the Apostle on his second missionary journey.

Name and ...

and Timothy

Timothy is a masculine name. It comes from the Greek language, Greek name (Timotheus (disambiguation), Timόtheos) meaning "honouring God", "in God's honour", or "honoured by God". Timothy (and its variations) is a common name in several countries ...

rejoined Paul here, having last seen him in Berea Berea may refer to:

Places Greece

* Beroea, a place mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles, now known as Veria or Veroia

* Veria, historically spelled and sometimes transliterated as Berea and site of the ancient city of Beroea

Lesotho

* Berea D ...

(). suggests that Jewish refusal to accept his preaching here led Paul to resolve no longer to speak in the synagogues where he travelled: "From now on I will go to the Gentiles". However, on his arrival in Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

(), the narrative records that Paul went to the synagogue to preach.

Paul wrote at least two epistles

An epistle (; ) is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The ...

to the Christian church, the First Epistle to the Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians () is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author, Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church i ...

(written from Ephesus) and the Second Epistle to the Corinthians

The Second Epistle to the Corinthians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author named Saint Timothy, Timothy, and is addressed to the church in Ancient Corin ...

(written from Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

). Both canonical epistles occasionally reflect the conflict between the missionary ambitions of the thriving Christian church and a strong desire to remain separate from the surrounding community.

Some scholars believe that Paul visited Corinth for an intermediate "painful visit" (see ) between the first and second epistles. After writing the second epistle, he stayed in Corinth for about three months in the late winter, and there wrote his Epistle to the Romans

The Epistle to the Romans is the sixth book in the New Testament, and the longest of the thirteen Pauline epistles. Biblical scholars agree that it was composed by Paul the Apostle to explain that Salvation (Christianity), salvation is offered ...

.

Based on clues within the Corinthian epistles themselves, some scholars have concluded that Paul wrote possibly as many as four epistles

An epistle (; ) is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The ...

to the church at Corinth. Only two are contained within the Christian canon (First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and Second Epistles to the Corinthians); the other two letters are lost. (The lost letters would probably represent the very first letter that Paul wrote to the Corinthians and the third one, and so the First and Second Letters of the canon would be the second and the fourth if four were written.) Many scholars think that the third one (known as the "letter of the tears"; see 2 Cor 2:4) is included inside the canonical Second Epistle to the Corinthians

The Second Epistle to the Corinthians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author named Saint Timothy, Timothy, and is addressed to the church in Ancient Corin ...

(it would be chapters 10–13). This letter is not to be confused with the so-called "Third Epistle to the Corinthians

The Third Epistle to the Corinthians is an early Christian text written by an unknown author claiming to be Paul the Apostle. It is also found in the Acts of Paul, and was framed as Paul's response to a letter of the Corinthians to Paul. The earl ...

", which is a pseudepigraphical letter written many years after the death of Paul.