Cold War Fiction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Playground equipment constructed during the Cold War was intended to foster children's curiosity and excitement about the

Playground equipment constructed during the Cold War was intended to foster children's curiosity and excitement about the

/ref> In 1961, at the height of the

excerpt and text search

* Day, Tony and Maya H. T. Liem. ''Cultures at War: The Cold War and Cultural Expression in Southeast Asia'' (2010) * Defty, Andrew. ''Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945-53: The Information Research Department'' (London: Routledge, 2004) on a British agency * Devlin, Judith, and Christoph H Muller. ''War of Words: Culture and the Mass Media in the Making of the Cold War in Europe'' (2013) * Fletcher, Katy. "Evolution of the Modern American Spy Novel." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1987) 22(2): 319–331

in Jstor

* Footitt, Hilary. "'A hideously difficult country': British propaganda to France in the early Cold War." ''Cold War History'' (2013) 13#2 pp: 153–169. * Gumbert, Heather. ''Envisioning Socialism: Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic'' (2014

excerpt and text search

* * * Hixson, Walter L. ''Parting the curtain: Propaganda, culture, and the Cold War'' (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997) * Iber, Patrick, ''Neither peace nor freedom: The cultural Cold War in Latin America''. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2015. * Jones, Harriet. "The Impact of the Cold War" in Paul Addison, and Harriet Jones, editors, ''A Companion to Contemporary Britain: 1939-2000'' (2008) ch 2 * Kuznick, Peter J. ed. ''Rethinking Cold War Culture'' (2010

excerpt and text search

* Major, Patrick. "Future Perfect?: Communist Science Fiction in the Cold War." ''Cold War History'' (2003) 4(1): 71–96. * Marwick, Arthur. ''The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, c.1958-c.1974'' (Oxford University Press, 1998). * Miceli, Barbara. "Super-secret spies, living next door: Family and Soft Power in The Americans". "Screening American Nostalgia" (edited by Susan Flynn and Antonia McKay), (McFarland, 2021, pp. 80–98). * Orwell, George. (1949). ''Nineteen-Eighty-Four''. London: Secker & Warburg. (later edn. ) * Polger, Uta G. ''Jazz, Rock, and Rebels: Cold War Politics and American Culture in a Divided Germany'' (2000) * Shaw, Tony. ''British cinema and the Cold War: the state, propaganda and consensus'' (IB Tauris, 2006) * Vowinckel, Annette, Marcus M. Pavk and Thomas Lindenberger, eds. ''Cold War Cultures: Perspectives on Eastern & Western Societies'' (2012) * Wenderski, Michał. "Art and Politics During the Cold War: Poland and the Netherlands" (Routledge, 2024)

A Historical Look at Campaign Commercials

*{{KLOV game, id=8715, name=Missile Command Cold War Cold War terminology Cultural history Articles containing video clips

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

was reflected in culture through music, movies, books, television, and other media, as well as sports, social beliefs, and behavior. Major elements of the Cold War included the threat of communist expansion, a nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

, and – connected to both – espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

. Many works use the Cold War as a backdrop or directly take part in a fictional conflict between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. The period 1953–62 saw Cold War themes becoming mainstream as a public preoccupation.

Fiction

Spy stories

Cloak and dagger

"Cloak and dagger" was a fighting style common by the time of the Renaissance involving a knife hidden beneath a cloak. The term later came into use as a metaphor, referring to situations involving intrigue, secrecy, espionage, or mystery.

Over ...

stories became part of the popular culture of the Cold War in both East and West, with innumerable novels and movies that showed how polarized and dangerous the world was. Soviet audiences were thrilled by spy stories showing how their KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

agents protected the motherland by foiling dirty work by the intelligence agencies of the United States, United Kingdom, and Israel. After 1963, Hollywood increasingly depicted the CIA as clowns (as in the comedy TV series ''Get Smart

''Get Smart'' is an American comedy television series parodying the Spy fiction, secret agent genre that had become widely popular in the first half of the 1960s with the release of the ''James Bond'' films. It was created by Mel Brooks and Bu ...

'') or villains (as in Oliver Stone's 1992 film ''JFK

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until Assassination of John F. Kennedy, his assassination in 1963. He was the first Catholic Chur ...

''). Ian Fleming's infamous spy novels about the MI6 agent James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

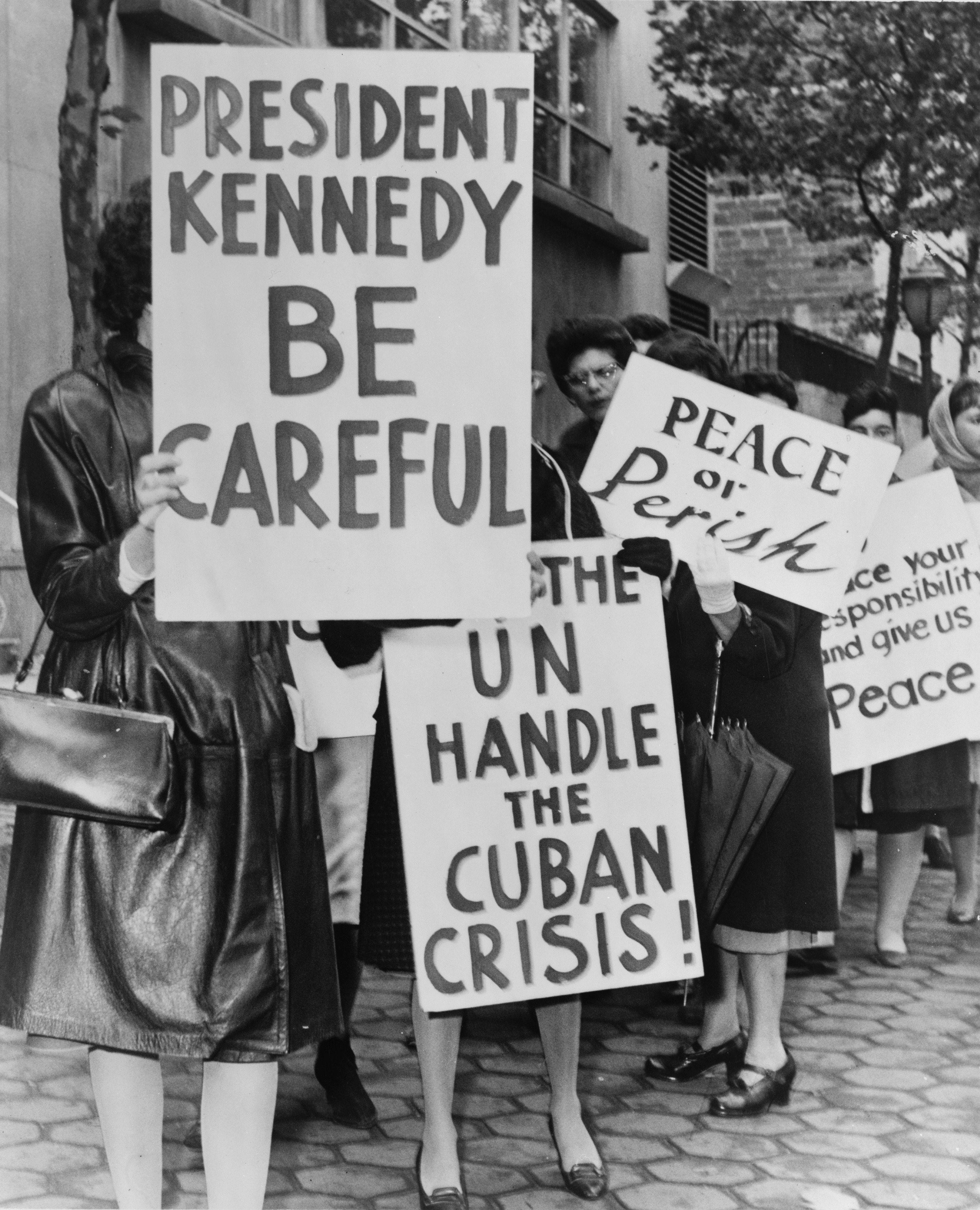

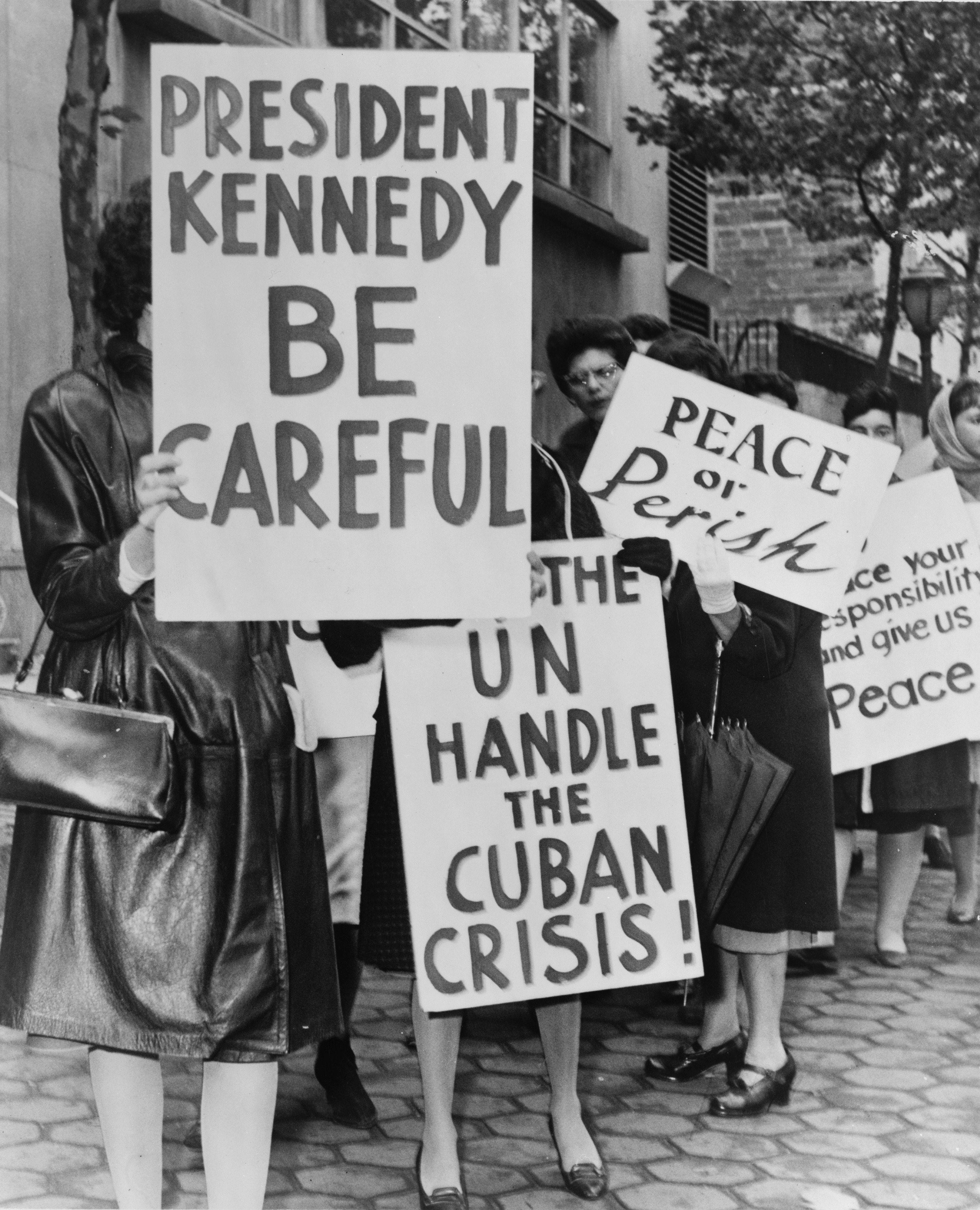

also referenced elements of the Cold War when being adapted into films. One example of this includes the first Bond film, Dr. No, which was released in 1962 and used the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

as a plot base. However, Cuba was substituted for Jamaica in the film.

Books and other works

* '' Atomsk'' by Paul Linebarger, published in 1949, is the first espionage novel of the Cold War. * ''Alas, Babylon

''Alas, Babylon'' is a 1959 novel by American writer Pat Frank. It is an early example of post-nuclear apocalyptic fiction and has an entry in David Pringle's book '' Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels''. The novel deals with the effects of ...

'' by Pat Frank

Harry Hart "Pat" Frank (May5, 1907October12, 1964) was an American newspaperman, writer, and government consultant. Perhaps the "first of the post-Hiroshima doomsday authors", ''Time'' (obituary), 23 October 1964, p 108. his best known work is ...

* '' Arc Light'' by Eric L. Harry

* ''Cat's Cradle

''Cat's Cradle'' is a satirical postmodern novel, with science fiction elements, by American writer Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut's fourth novel, it was first published on March 18, 1963, exploring and satirizing issues of science, technology, the p ...

'' by Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut ( ; November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American author known for his Satire, satirical and darkly humorous novels. His published work includes fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfict ...

* ''The Dispossessed

''The Dispossessed'' (subtitled ''An Ambiguous Utopia'') is a 1974 anarchist utopian science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, one of her seven Hainish Cycle novels. It is one of a small number of books to win all three Hugo, ...

'' by Ursula Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin ( ; Kroeber; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author. She is best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the ''Earthsea'' fantas ...

is a science fiction novel exploring the differences in culture and philosophy between several alien societies, including that of an anarcho-syndicalist planet where most of the novel is set.

* ''Red Alert

Red Alert or red alert may refer to:

Alert states

* Red alert, a high alert state

* Red Alert, the "attack imminent" alert signal for the US civil defense siren

* Red alert state, the most serious alert state in the UK BIKINI state system

* Red ...

'' by Peter George

* '' Resurrection Day'' by Brendan DuBois

* '' Twilight 2000'', role-playing game

A role-playing game (sometimes spelled roleplaying game, or abbreviated as RPG) is a game in which players assume the roles of player character, characters in a fictional Setting (narrative), setting. Players take responsibility for acting out ...

.

* '' Warday'' by Whitley Strieber

Louis Whitley Strieber (; born June 13, 1945) is an American writer best known for his horror novels '' The Wolfen'' and '' The Hunger'' and for '' Communion'', a non-fiction account of his alleged experiences with non-human entities. He has mai ...

and James Kunetka

* '' Red Storm Rising'' a 1986 novel by Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military science, military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of ...

, about a conventional NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

/Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

war.

** Other Tom Clancy novels which are part of the Jack Ryan universe, most especially ''The Hunt for Red October

''The Hunt for Red October'' is the debut novel by American author Tom Clancy, first published on October 1, 1984, by the Naval Institute Press. It depicts Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius as he seemingly goes rogue with his country's cutt ...

'' and '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'', though all of his books from this era are featured against a background of east–west conflict. Later '' Red Rabbit'' narrates a "What-If" scenario of the Soviets being behind the 1981 assassination attempt on the Pope.

* ''1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

'' by George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

* Frederick Forsyth

Frederick McCarthy Forsyth ( ; 25 August 1938 – 9 June 2025) was an English novelist and journalist. He was best known for thrillers such as ''The Day of the Jackal'', ''The Odessa File'', ''The Fourth Protocol'', ''The Dogs of War (novel), ...

's spy novels sold in the hundreds of thousands. '' The Fourth Protocol'', whose title refers to a series of conventions that, if broken, will lead to nuclear war and that are now, of course, all broken except for the fourth and last thread, was made into a major film starring British actor Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine (born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite, 14 March 1933) is a retired English actor. Known for his distinct Cockney accent, he has appeared in more than 160 films over Michael Caine filmography, a career that spanned eight decades an ...

.

* '' The Manchurian Candidate'', by Richard Condon, took a different approach and portrayed a Communist conspiracy against the US acting not through leftists or pacifists but through a thinly veiled allusion to Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

. The logic of this was that if McCarthyists were accusing so many people of being communist agents, it could only be to divert attention from the real communists. The theme of collusion between international communists and Western rightists would be picked up again by many movies ('' Goldfinger'', ''A View to a Kill

''A View to a Kill'' is a 1985 spy film, the fourteenth in the ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions, and the seventh and final appearance of Roger Moore as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. Although the title is adapted from ...

'') or television shows (episodes of ''MacGyver

Angus "Mac" MacGyver is the title character and the protagonist in the TV series ''MacGyver''. He is played by Richard Dean Anderson in the MacGyver (1985 TV series), 1985 original series. Lucas Till portrays a younger version of MacGyver in Mac ...

'' or ''Airwolf

''Airwolf'' is an American action military drama television series. It centers on a high-technology attack helicopter, code-named '' Airwolf'', and its crew. They undertake various exotic missions, many involving espionage, with a Cold War the ...

''), which would feature an alliance between power-hungry communists attacking the free world from the outside and profit-driven capitalists undermining it for financial gain.

* '' The Ugly American'' by William J. Lederer and Eugene Burdick. Originally published in 1958, this book tells the story of how the US government handled foreign policy very poorly. The main character, Homer Atkins, discovers this sad truth when he is dispatched to the fictitious country of Sarkhan (in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

.)

* ''One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

''One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich'' (, ) is a short novel by the Russian writer and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, first published in November 1962 in the Soviet literary magazine ''Novy Mir'' (''New World'').Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system. He was a ...

. This acclaimed book, first published in 1962, exposed the horrors of the Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

n prison camps during WWII

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

under the Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

regime. It is a semi-autobiographical tale about a dutiful soldier who is sent to a Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

n camp, after being falsely accused of treason. Solzhenitsyn received the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

in literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

.

* ''Starship Troopers

''Starship Troopers'' is a military science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Written in a few weeks in reaction to the US suspending nuclear tests, the story was first published as a two-part serial in ''The Magazine of ...

'' by Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

*Twilight Struggle

''Twilight Struggle: The Cold War, 1945–1989'' is a board game for two players, published by GMT Games in 2005. Players are the United States and Soviet Union contesting each other's influence on the world map by using cards that correspond to ...

is a 2005 card-based board game by GMT Games

GMT Games is a California-based wargaming publisher founded in 1990. The company has become well known for graphically attractive games that range from "monster games" of many maps and counters, to quite simple games suitable for introducing new ...

that depicts the events of the entire Cold War, starting from Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

to Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

. The game was turned into a video game in 2016.

Cinema

Use as early Cold War propaganda

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union each invested heavily in propaganda designed to sway both domestic and foreign opinion in the respective country's favor, especially using motion pictures. The quality gap between American and Soviet film gave the Americans a distinct advantage over the Soviet Union; the United States was readily prepared to utilize their cinematic superiority as a way to effectively impact the public opinion in a way the Soviet Union could not. Americans hoped that achievements in cinema would compensate for America's failure to keep up with Soviet development ofnuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

and advancements in space technology. The use of film as an effective form of widespread propaganda transformed cinema into another Cold War battlefront alongside the arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

and Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

. Films from both the United States and Soviet Union can be seen as artifacts of propaganda as well as resistance.

US cinema

The Americans took advantage of their pre-existing cinematic advantage over the Soviet Union, using movies as another way to create the Communist enemy. In the early years of the Cold War (between 1948 and 1953), seventy explicitly anti-communist films were released. American films incorporated a wide scale of Cold War themes and issues into all genres of film, which gave American motion pictures a particular lead over Soviet film. Despite the audiences' lack of zeal for Anti-Communist/Cold War related cinema, the films produced evidently did serve as successful propaganda in both the United States and the Soviet Union. The films released during this time received a response from the Soviet Union, which subsequently released its own array of films to combat the depiction of the Communist threat. Several organizations played a key role in ensuring that Hollywood acted in the national best interest of the US, like the Catholic Legion of Decency and theProduction Code Administration

The Motion Picture Association (MPA) is an American trade association representing the five major film studios of the United States, the mini-major Amazon MGM Studios, as well as the video streaming services Netflix and Amazon Prime Video. Fo ...

, which acted as two conservative groups that controlled a great deal of the national repertoire during the early stages of the Cold War. These groups filtered out politically subversive or morally questionable movies. More blatantly illustrating the shift from cinema as an art form to cinema as a form of strategic weapon, the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals ensured that filmmakers adequately expressed their patriotism. Beyond these cinema-specific efforts, the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

played a surprisingly large role in the production of movies, instituting a triangular-shaped film strategy: FBI set up a surveillance operation in Hollywood, made efforts to pinpoint and blacklist Communists, secretly laundered intelligence through HUAC

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty an ...

, and further helped in producing movies that "fostered he FBIimage as the protector of the American people." The FBI additionally endorsed films, including Oscar winner '' The Hoaxters''.

In the 1960s, Hollywood began using spy films

The spy film, also known as the spy thriller, is a genre of film that deals with the subject of fictional espionage, either in a realistic way (such as the adaptations of John le Carré) or as a basis for fantasy (such as many James Bond fil ...

to create the enemy through film. Previously, the influence of the Cold War could be seen in many, if not all, genres of American film. By the 1960s, spy films were effectively a "weapon of confrontation between the two world systems." Both sides heightened paranoia and created a sense of constant unease in viewers through the increased production of spy films. Film depicted the enemy in a way that caused both sides to increase general suspicion of foreign and domestic threat.

Soviet cinema

Between 1946 and 1954, the Soviet Union mimicked the US adoption of cinema as a weapon. The Central United Film Studios and the Committee on Cinema Affairs were committed to the Cold War battle. UnderStalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's rule, movies could only be made within strict confines. Cinema and government were, as it stood, inextricably linked. Many films were banned for being insufficiently patriotic. Nonetheless, the Soviet Union produced a plethora of movies with the aim to blatantly function as negative propaganda.

In the same fashion as the United States, the Soviets were eager to depict their enemy in the most unflattering light possible. Between 1946 and 1950, 45.6% of on-screen villains in Soviet films were either American or British. Films addressed non-Soviet themes that emerged in American film in an attempt to derail the criticism and paint the US as the enemy. Attacks made by the United States against the Soviet Union were simply used as material by Soviet filmmakers for their own attacks on the US. Soviet cinema during this time took its liberty with history: "Did the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

engage in the mass rapes of German women and pillage German art treasures, factories, and forests? In Soviet cinema, the opposite was true in '' he Meeting on the Elbe'." This demonstrated the heightened paranoia of the Soviet Union.

Despite efforts made to elevate the status of cinema, such as changing the Committee of Cinema Affairs to the Ministry of Cinematography, cinema did not seem to work as invigorating propaganda as was planned. Although the anti-American films were notably popular with audiences, the Ministry did not feel the message had reached the general public, perhaps due to the fact that the majority of moviegoers seeing the films produced were, perhaps, the Soviets most likely to admire American culture.

After Stalin's death, a Main Administration of Cinema Affairs replaced the Ministry, allowing the filmmakers more freedom due to the lack of direct government control. Many of the films released throughout the late 1950s and 1960s focused on spreading a positive image of Soviet life, intent to prove that Soviet life was indeed better than American life.

Russian science fiction emerged from a prolonged period of censorship in 1957, opened up by de-Stalinization and real Soviet achievements in the space race, typified by Ivan Efremov's galactic epic, ''Andromeda'' (1957). Official Communist science fiction transposed the laws of historical materialism to the future, scorning Western nihilistic writings and predicting a peaceful transition to universal communism. Scientocratic visions of the future nevertheless implicitly critiqued the bureaucratically developed socialism of the present. Dissident science fiction writers emerged, such as the Strugatski brothers, Boris and Arkadi, with their "social fantasies," problematizing the role of intervention in the historical process, or Stanislaw Lem's tongue-in-cheek exposures of man's cognitive limitations.

Films depicting nuclear war

* '' Duck and Cover,'' a 1951 educational movie explaining what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. * '' Five,'' a 1951 film about five survivors, one woman and four men, of an atomic war that has wiped out the rest of the human race (while leaving all infrastructure intact). The five come together at a remote, isolated hillside house inSouthern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural List of regions of California, region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. Its densely populated coastal reg ...

, where they try to figure out how to survive while also being forced to face an unknown future.

* '' On the Beach'' (1959) depicted a gradually dying, post-apocalyptic world in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

that remained after a nuclear Third World War.

* '' Ladybug Ladybug'' (1963) an elementary school nuclear bomb warning alarm sounds.

* '' Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'' (1964) – A black comedy

Black comedy, also known as black humor, bleak comedy, dark comedy, dark humor, gallows humor or morbid humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally ...

film that satirizes the Cold War and the threat of nuclear warfare.

* ''Fail-Safe

In engineering, a fail-safe is a design feature or practice that, in the event of a failure causes, failure of the design feature, inherently responds in a way that will cause minimal or no harm to other equipment, to the environment or to people. ...

'' (1964) – A film based on a novel of the same name about an American bomber crew and nuclear tensions.

* ''The War Game

''The War Game'' is a 1966 British pseudo-documentary film that depicts a nuclear war and its aftermath. Written, directed and produced by Peter Watkins for the BBC, it caused dismay within the BBC and within government, and was withdrawn bef ...

'' (BBC, 1965; aired 1985) – Depicts the effects of a nuclear war in Britain following a conventional war that escalates to nuclear war.

* '' Damnation Alley'' (20th Century Fox, 1977) – Surprise ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

attack launched on the United States, and the subsequent efforts of a small band of survivors from a missile silo

A missile launch facility, also known as an underground missile silo, launch facility (LF), or nuclear silo, is a vertical cylindrical structure constructed underground, for the storage and launching of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM ...

in the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert (; ; ) is a desert in the rain shadow of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains and Transverse Ranges in the Southwestern United States. Named for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous Mohave people, it is located pr ...

in California to reach another group of survivors in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

.

* '' The Children's Story'' (1982) short film, which originally aired on TV's Mobil Showcase, depicts the first day of indoctrination of an elementary school classroom by a new teacher, representing a totalitarian government that has taken over the United States. It is based on the 1960 short story of the same name by James Clavell

James Clavell (born Charles Edmund Dumaresq Clavell; 10 October 1921 – 7 September 1994) was a British and American writer, screenwriter, director, and World War II veteran and prisoner of war. Clavell is best known for his ''Asian Saga'' nov ...

.

* '' The Day After'' (1983) – This made-for-television-movie by ABC that depicts the consequences of a nuclear war in Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is a city in and the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70 in Kansas, Interstate 70, between the Kansas River ...

and the surrounding area.

* ''WarGames

''WarGames'' is a 1983 American techno-thriller film directed by John Badham, written by Lawrence Lasker and Walter F. Parkes, and starring Matthew Broderick, Dabney Coleman, John Wood and Ally Sheedy. Broderick plays David Lightman, a ...

'' (1983) – About a young computer hacker

A hacker is a person skilled in information technology who achieves goals and solves problems by non-standard means. The term has become associated in popular culture with a security hackersomeone with knowledge of bug (computing), bugs or exp ...

who unknowingly hacks into a defense computer and risks starting a nuclear war.

* ''Testament

A testament is a document that the author has sworn to be true. In law it usually means last will and testament.

Testament or The Testament can also refer to:

Books

* ''Testament'' (comic book), a 2005 comic book

* ''Testament'', a thriller no ...

'' (PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

, 1983) – Depicts the after-effects of a nuclear war in a small town, 100 miles north of San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

.

* '' Countdown to Looking Glass'' (HBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American pay television service, which is the flagship property of namesake parent-subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is based a ...

, 1984) – A film that presents a simulated news broadcast about a nuclear war.

* '' Threads'' (BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

, 1984) – A film that is set in the British city of Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

and shows the long-term results of a nuclear war on the surrounding area.

* '' The Sacrifice'' (Sweden, 1986) – A philosophical drama about nuclear war.

* '' The Manhattan Project'' (1986) – Though not about a nuclear war, it was seen as a cautionary tale.

* '' When the Wind Blows'' (1986) – An animated film about an elderly British couple in a post-nuclear war world.

* '' Miracle Mile'' (1988) – A film about two lovers in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

leading up to a nuclear war.

* '' By Dawn's Early Light'' (HBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American pay television service, which is the flagship property of namesake parent-subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is based a ...

, 1990) – About rogue Soviet military officials framing NATO for a nuclear attack in order to spark a full-blown nuclear war.

* '' On the Beach'' ( Showtime, 2000) – A remake of the 1959 film.

* ''Fail-Safe'' (CBS, 2000) – A remake of the 1964 film.

Films depicting a conventional United States–Soviet Union war

In addition to fears of a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, during the Cold War, there were also fears of a direct, large scale conventional conflict between the two superpowers. * '' Invasion U.S.A.'' (1952) – The 1952 film showed a Soviet invasion of the United States succeeding because the citizenry had fallen into moral decay,war profiteering

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives unreasonable profit (economics), profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteerin ...

, and isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

. The film was later parodied on Mystery Science Theater 3000

''Mystery Science Theater 3000'' (abbreviated as ''MST3K'') is an American science fiction comedy television series created by Joel Hodgson. The show premiered on WUCW, KTMA-TV (now WUCW) in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on November 24, 1988. It then ...

.

* '' Red Nightmare'', a 1962 government-sponsored short subject narrated by Jack Webb

John Randolph Webb (April 2, 1920 – December 23, 1982) was an American actor, television producer, Television director, director, and screenwriter, most famous for his role as Joe Friday in the Dragnet (franchise), ''Dragnet'' franchise ...

, imagined a Soviet-dominated United States as a result of the protagonist's negligence of his "all-American" duties.

* ''World War III

World War III, also known as the Third World War, is a hypothetical future global conflict subsequent to World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). It is widely predicted that such a war would involve all of the great powers, ...

'', a 1982 NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

miniseries about a Soviet invasion of Alaska.

* ''Red Dawn

''Red Dawn'' is a 1984 American action drama film directed by John Milius, from a screenplay co-written with Kevin Reynolds. The film depicts a fictional World War III centering on a military invasion of the United States by an alliance of ...

'' (1984) – presented a conventional Soviet attack with limited, strategic Soviet nuclear strikes on the United States, aided by allies from Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

, and the exploits of a group of high schoolers who form a guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

group to oppose them.

* '' Invasion U.S.A.'' (1985) – This film depicts a Soviet agent leading Latin American Communist guerillas launching attacks in the United States, and an ex-CIA agent played by Chuck Norris

Carlos Ray "Chuck" Norris (born March 10, 1940) is an American martial artist and actor. Born in Oklahoma, Norris first gained fame when he won the amateur Middleweight Karate champion title in 1968, which he held for six consecutive years. H ...

opposing him and his mercenaries.

* '' Amerika'' (ABC, 1987), a peaceful takeover of the United States by the Soviet Union.

Films depicting Cold War espionage

* '' Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy'' is a 2011Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

spy thriller adaptation of the 1974 John le Carré novel of the same name. It is set in London in the early 1970s and follows the hunt for a Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

at the top of the British secret service.

*''The Spy Who Came In from the Cold

''The Spy Who Came in from the Cold'' is a 1963 Cold War spy fiction, spy novel by the British author John le Carré. It depicts Alec Leamas, a United Kingdom, British intelligence officer, being sent to East Germany as a faux Defection, defect ...

'' is a 1965 British Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

spy film

The spy film, also known as the spy thriller, is a film genre, genre of film that deals with the subject of fictional espionage, either in a realistic way (such as the adaptations of John le Carré) or as a basis for fantasy (such as many Jame ...

based on the 1963 John le Carré novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

. The film depicts a British agent's mission as a faux defector to East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

to sow damaging disinformation about a powerful East German intelligence officer.

*''Firefox

Mozilla Firefox, or simply Firefox, is a free and open-source web browser developed by the Mozilla Foundation and its subsidiary, the Mozilla Corporation. It uses the Gecko rendering engine to display web pages, which implements curr ...

'' is a 1982 film based on a Craig Thomas novel of the same name. The plot details an American plot to steal a highly advanced Soviet fighter aircraft ( MiG-31 Firefox) which is capable of Mach 6, is invisible to radar, and carries weapons controlled by thought.

* ''The Hunt for Red October

''The Hunt for Red October'' is the debut novel by American author Tom Clancy, first published on October 1, 1984, by the Naval Institute Press. It depicts Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius as he seemingly goes rogue with his country's cutt ...

'' is a 1990 film based on the 1984 Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military science, military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of ...

novel of the same name about the captain of a technologically advanced Soviet ballistic missile submarine that attempts to defect to the United States.

* James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

first appeared in 1953. While the primary antagonists in the majority of the novels were Soviet agents, the films were only vaguely based on the Cold War. The Bond movies followed the political climate of the time in their depictions of Soviets and "Red" Chinese. In the 1954 version of ''Casino Royale'', Bond was an American agent working with the British to destroy a ruthless Soviet agent in France, but became more widely known as Agent 007, James Bond, of Her Majesty's Secret Service, who was played by Sean Connery

Sir Thomas Sean Connery (25 August 1930 – 31 October 2020) was a Scottish actor. He was the first actor to Portrayal of James Bond in film, portray the fictional British secret agent James Bond (literary character), James Bond in motion pic ...

until 1971 and by several actors since. Although Bond films often used the Cold War as a backdrop, the Soviet Union itself was almost never Bond's enemy, that role being more often left to fictional and apolitical criminal organizations (like the infamous SPECTRE

Spectre, specter or the spectre may refer to:

Religion and spirituality

* Vision (spirituality)

* Apparitional experience

* Ghost

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Spectre'' (1977 film), a made-for-television film produced and writt ...

). However, Red China was in league with Bond's enemies in the films '' Goldfinger'', '' You Only Live Twice'' and '' The Man With the Golden Gun'', while some later movies (''Octopussy

''Octopussy'' is a 1983 spy film and the thirteenth in the List of James Bond films, ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions. It is the sixth to star Roger Moore as the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6 agent James Bond filmography, J ...

'', '' The Living Daylights'') featured a rogue Soviet general as the enemy.

* TASS Upolnomochen Zayavit... (TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS, or simply TASS, is a Russian state-owned news agency founded in 1904. It is the largest Russian news agency and one of the largest news agencies worldwide.

TASS is registered as a Federal State Unitary Enterpri ...

is Authorized to Announce ... ) – a Soviet TV series based on Julian Semenov's novel. The plot of the movie is set around fictional African country Nagonia, where CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

agents are preparing a military coup, while KGB agent Slavin is trying to prevent it. Slavin succeeds by blackmailing the corrupt American spy John Glebe.

* The Falcon and the Snowman is a 1985 film directed by John Schlesinger

John Richard Schlesinger ( ; 16 February 1926 – 25 July 2003) was an English film and stage director, and actor. He emerged in the early 1960s as a leading light of the British New Wave, before embarking on a successful career in Hollywood ...

about two young American men, Christopher Boyce and Daulton Lee, who sold United States security secrets to the Soviet Union. The film is based upon the 1979 book ''The Falcon and the Snowman: A True Story of Friendship and Espionage'' by Robert Lindsey.

* ''Gotcha!'' (1985 film) is a film about a college student named Jonathan ( Anthony Edwards) who plays a game called Gotcha in which he hunts and is hunted by other students with paint guns on campus. Jonathan goes to France on vacation, meets a beautiful woman named Sasha ( Linda Fiorentino), travels with her to East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

, and unknowingly becomes involved in the spy game between the US and USSR.

*'' The Kremlin Letter'' is a 1970 American neo-noir

Neo-noir is a film genre that adapts the visual style and themes of 1940s and 1950s American film noir for contemporary audiences, often with more graphic depictions of violence and sexuality. During the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the term ...

espionage thriller

Spy fiction is a genre of literature involving espionage as an important context or plot device. It emerged in the early twentieth century, inspired by rivalries and intrigues between the major powers, and the establishment of modern intellig ...

set in the winter of 1969–1970, at the height of US-Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

tensions.

* '' No Way Out'' a 1987 film about a spy myth that is created to cover up the killing of the mistress of a high American official.

Other films about Soviet Union–United States fears and rivalry

* ''The Third Man

''The Third Man'' is a 1949 film noir directed by Carol Reed, written by Graham Greene, and starring Joseph Cotten as Holly Martins, Alida Valli as Anna Schmidt, Orson Welles as Harry Lime and Trevor Howard as Major Calloway. Set in post-Worl ...

'' (1949) – A major subplot deals with the refugee status

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

of a Czechoslovakian woman, and the Russian attempts to deport her back to Czechoslovakia.

* '' The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming'' (1966) – A film about a Soviet submarine that accidentally runs aground near a small New England town.

* ''Russian Roulette

Russian roulette () is a potentially lethal game of chance in which a player places a single round in a revolver, spins the cylinder, places the muzzle against the head or body (their opponent's or their own), and pulls the trigger. If the ...

'' (1975) – A film starring George Segal

George Segal Jr. (February 13, 1934 – March 23, 2021) was an American actor. He became popular in the 1960s and 1970s for playing both dramatic and comedic roles. After first rising to prominence with roles in acclaimed films such as '' Ship o ...

about a Canadian Mounty attempting to stop a KGB plot to assassinate a Soviet premier in Vancouver.

*'' Telefon'' (1977) – A film starring Charles Bronson

Charles Bronson (born Charles Dennis Buchinsky; November 3, 1921 – August 30, 2003) was an American actor. He was known for his roles in action films and his "granite features and brawny physique". Bronson was born into extreme poverty in ...

and Donald Pleasence

Donald Henry Pleasence (; 5 October 1919 – 2 February 1995) was an English actor. He was known for his "bald head and intense, staring eyes," and played more than 250 stage, film, and television roles across a nearly sixty-year career.

Pleas ...

about the net of deep-cover sleeper agent

A sleeper agent is a spy or operative who is placed in a target country or organization, not to undertake an immediate mission, but instead to act as a potential asset on short notice if activated in the future. Even if not activated, the "sle ...

s in the US who are being activated by the deserted KGB agent.

*The Return of Godzilla

, is a 1984 Japanese ''kaiju'' film directed by Koji Hashimoto, with special effects by Teruyoshi Nakano. Distributed by Toho and produced under their subsidiary Toho Pictures, it is the 16th film in the ''Godzilla'' franchise, the last film ...

(1984) — In the 16th installment of the Toho

is a Japanese entertainment company that primarily engages in producing and distributing films and exhibiting stage plays. It is headquartered in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and is one of the core companies of the Osaka-based Hankyu Hanshin Toho Group. ...

Godzilla

is a fictional monster, or ''kaiju'', that debuted in the eponymous 1954 film, directed and co-written by Ishirō Honda. The character has since become an international pop culture icon, appearing in various media: 33 Japanese films p ...

franchise, a Soviet nuclear submarine is destroyed by the titular creature, causing tensions between the Soviet Union & America until it is proven by the Japanese government that Godzilla was responsible for its destruction. Later in the movie, a Russian nuclear missile is accidentally fired at Godzilla from a space satellite until an American missile detonates it in the stratosphere long before it can strike Godzilla in Tokyo.

* ''Rocky IV

''Rocky IV'' is a 1985 American sports drama film starring, written and directed by Sylvester Stallone. The film is the sequel to '' Rocky III'' (1982) and the fourth installment in the ''Rocky'' franchise. It also stars Talia Shire, Burt You ...

'' (1985) – In this installment of the Rocky saga, Rocky Balboa

Robert "Rocky" Balboa (also known by his ring name the Italian Stallion) is a fictional character and the titular protagonist of the ''Rocky'' franchise. The character was created by Sylvester Stallone, who has also portrayed him in eight of ...

has to fight an extremely powerful boxer from the Soviet Union.

* ''Spies Like Us

''Spies Like Us'' is a 1985 American spy comedy film directed by John Landis, and starring Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd, Steve Forrest, and Donna Dixon. The film presents the comic adventures of two novice intelligence agents sent to the Soviet ...

'' (1985) – A comedy film starring Dan Aykroyd

Daniel Edward Aykroyd ( ; born July 1, 1952) is a Canadian actor, comedian, screenwriter, and producer.

Aykroyd was a writer and an original member of the "Not Ready for Prime Time Players" cast on the NBC sketch comedy series ''Saturday Nigh ...

and Chevy Chase

Cornelius Crane "Chevy" Chase (; born October 8, 1943) is an American comedian, actor, and writer. He became the breakout cast member in the first season of ''Saturday Night Live'' (1975–1976), where his recurring ''Weekend Update'' segment b ...

as decoy agents send to infiltrate the Soviet Union.

* '' Russkies'' (1987) – A movie about a shipwrecked Soviet Navy

The Soviet Navy was the naval warfare Military, uniform service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces. Often referred to as the Red Fleet, the Soviet Navy made up a large part of the Soviet Union's strategic planning in the event of a conflict with t ...

sailor who washes ashore in Key West, Florida and is befriended by three American boys.

* '' Project X'' (1987) – A film starring Matthew Broderick

Matthew Broderick (born March 21, 1962) is an American actor. He starred in ''WarGames'' (1983) as a teen government hacker, and ''Ladyhawke (film), Ladyhawke'' (1985), a medieval fantasy alongside Rutger Hauer and Michelle Pfeiffer. He play ...

where a US airman works with chimpanzees on Cold War-related projects.

Films about Historical Cold War events

*'' Thirteen Days'' (2001), about the Cuban Missile Crisis. *'' Bridge Of Spies'' (2015), about a spy swap.Television

* ''Airwolf

''Airwolf'' is an American action military drama television series. It centers on a high-technology attack helicopter, code-named '' Airwolf'', and its crew. They undertake various exotic missions, many involving espionage, with a Cold War the ...

''

* ''Danger Man

''Danger Man'' (retitled ''Secret Agent'' in the United States for the revived series, and ''Destination Danger'' and ''John Drake'' in other overseas markets) is a British television series that was broadcast between 1960 and 1962, and again ...

'', (Known as Secret Agent

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ''e ...

in the United States)

* '' I Led Three Lives'' – The first foray into mass culture dealing with the Cold War.

* '' I Spy'' (1965–68 US television series)

* ''Get Smart

''Get Smart'' is an American comedy television series parodying the Spy fiction, secret agent genre that had become widely popular in the first half of the 1960s with the release of the ''James Bond'' films. It was created by Mel Brooks and Bu ...

''

* ''MacGyver

Angus "Mac" MacGyver is the title character and the protagonist in the TV series ''MacGyver''. He is played by Richard Dean Anderson in the MacGyver (1985 TV series), 1985 original series. Lucas Till portrays a younger version of MacGyver in Mac ...

''

* '' The Man from U.N.C.L.E.''

* '' Mission: Impossible''

* '' Quatermass II''

* Several episodes of ''Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the Star Trek: The Original Series, series of the same name and became a worldwide Popular culture, pop-culture Cultural influence of ...

'' featured a futuristic version of the Cold War, in terms of the United Federation of Planets vs. The Klingon Empire and the Romulan Star Empire, analogs for the United States, the Soviet Union, and the People's Republic of China, respectively. "A Taste of Armageddon

"A Taste of Armageddon" is the twenty-third episode of the first season of the American science fiction television series ''Star Trek''. Written by Robert Hamner and Gene L. Coon and directed by Joseph Pevney, it was first broadcast on Februa ...

" also showed the concept of MAD in a war between opposing sides.

* ''Scarecrow and Mrs. King

''Scarecrow and Mrs. King'' is an American television series that aired from October 3, 1983, to May 28, 1987, on CBS. The music underscore was composed by Arthur B. Rubinstein.

The show starred Kate Jackson and Bruce Boxleitner, as divorced ...

''

* ''Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

'' 1976 sitcom

* '' The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show'' 1960s cartoon for children and adults where the villains are Boris and Natasha, who were both parodies of the soviets.

* '' The Sandbaggers''

* ''The Twilight Zone

''The Twilight Zone'' is an American media franchise based on the anthology series, anthology television series created by Rod Serling in which characters find themselves dealing with often disturbing or unusual events, an experience described ...

'', a number of episodes of which depicted fallout shelter

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designated to protect occupants from radioactive debris or fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the Cold War.

Durin ...

s, such as the 1961 episode, '' The Shelter'', produced as a social commentary on the Civil Defense

Civil defense or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from human-made and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency management: Risk management, prevention, mitigation, prepara ...

push during the Berlin Crisis of 1961

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 () was the last major European political and military incident of the Cold War concerning the status of the German capital city, Berlin, and of History of Germany (1945–90), post–World War II Germany. The crisis cul ...

, and the 1987 Ronald Reagan era " Shelter Skelter". Twilight Zone episodes commenting on other aspects of the Cold War, and World Peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

include the 1986 '' A Small Talent for War''.

* ''The Transformers (TV series)

''The Transformers'' is an animated television series that originally aired from September 17, 1984, to November 11, 1987, in syndication

based upon Hasbro and Takara's ''Transformers'' toy line. The first television series in the ''Transfor ...

'', including the fact that the two first seasons take place during the latter years of the Cold War, an episode, ''Prime Target'' directly refers to an event of the episode as ''The highest point of tension between United States and Soviet Union, since the Cuban Missile Crisis''.

Television commercials

Wendy's

Wendy's International, LLC, is an American international fast food restaurant chain founded by Dave Thomas (businessman), Dave Thomas on November 15, 1969, in Columbus, Ohio. Its headquarters moved to Dublin, Ohio, on January 29, 2006. As of D ...

Hamburger Chain ran a television commercial

A television advertisement (also called a commercial, spot, break, advert, or ad) is a span of television programming produced and paid for by an organization. It conveys a message promoting, and aiming to market, a product, service or idea. ...

showing a supposed "Soviet Fashion Show", which featured the same large, unattractive woman wearing the same dowdy outfit in a variety of situations, the only difference being the accessory she carried (for example, a flashlight for 'nightwear' or a beach ball for 'swimwear'). This was supposedly a lampoon on how the Soviet society is characterised with uniformity and standardisation, in contrast to the US characterised with freedom of choice, as highlighted in the Wendy's commercial.

Apple Computer

Apple Inc. is an American multinational corporation and technology company headquartered in Cupertino, California, in Silicon Valley. It is best known for its consumer electronics, software, and services. Founded in 1976 as Apple Computer Co ...

's "1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

" ad, despite paying homage to George Orwell's novel of the same name, follows a more serious yet ambitious take on the freedom vs. totalitarianism theme evident between the US and Soviet societies at the time.

Political commercials

Daisies and mushroom clouds

'' Daisy'' was the most famous campaign commercial of the Cold War. Aired only once, on 7 September 1964, it was a factor inLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

's defeat of Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

in the 1964 presidential election. The contents of the commercial were controversial, and their emotional impact was searing.

The commercial opens with a very young girl standing in a meadow with chirping birds, slowly counting the petals of a daisy as she picks them one by one. Her sweet innocence, along with mistakes in her counting, endear her to the viewer. When she reaches "9", an ominous-sounding male voice is suddenly heard intoning the countdown of a rocket launch

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

. As the girl's eyes turn toward something she sees in the sky, the camera zooms in until one of her pupils fills the screen, blacking it out. The countdown reaches zero, and the blackness is instantly replaced by a simultaneous bright flash and thunder

Thunder is the sound caused by lightning. Depending upon the distance from and nature of the lightning, it can range from a long, low rumble to a sudden, loud crack. The sudden increase in temperature and hence pressure caused by the lightning pr ...

ous sound which is then followed by footage of a nuclear explosion

A nuclear explosion is an explosion that occurs as a result of the rapid release of energy from a high-speed nuclear reaction. The driving reaction may be nuclear fission or nuclear fusion or a multi-stage cascading combination of the two, th ...

, an explosion similar in appearance to the near surface burst Trinity test

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

of 1945, followed by another cut to footage of a billowing mushroom cloud

A mushroom cloud is a distinctive mushroom-shaped flammagenitus cloud of debris, smoke, and usually condensed water vapour resulting from a large explosion. The effect is most commonly associated with a nuclear explosion, but any sufficiently e ...

.

As the fireball ascends, an edit cut is made, this time to a close-up section of incandescence

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by the thermal motion of particles in matter. All matter with a temperature greater than absolute zero emits thermal radiation. The emission of energy arises from a combination of electron ...

in the mushroom cloud, over which a voiceover

Voice-over (also known as off-camera or off-stage commentary) is a production technique used in radio, television, filmmaking, theatre, and other media in which a descriptive or expository voice that is not part of the narrative (i.e., non- ...

from Johnson is played, which states emphatically, "These are the stakes! To make a world in which all of God's children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die." Another voiceover then says, "Vote for President Johnson on November 3. The stakes are too high for you to stay home." (Two months later, Johnson won the election in an electoral landslide.)

Bear in the woods

Bear in the woods was a1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

campaign advertisement endorsing Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

that depicted a brown bear (likely symbolizing the Soviet Union) wandering through the woods. Despite the fact that the ad never explicitly mentioned the Soviet Union, the Cold War or Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928April 19, 2021) was the 42nd vice president of the United States serving from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Minnesota from 1964 to 1976. ...

, it thematically suggested that Reagan was more capable of dealing with the Soviets than his opponent.

Humor

The 1984 " We begin bombing in five minutes" incident is an example of cold war dark humor. It was a personal microphone gaffe joke between Ronald Reagan, his White House staff and radio technicians that was accidentally leaked to the US populace. At the time, Reagan was well known before this incident for telling Soviet/ Russian jokes in televised debates, many of which have now been uploaded to video hosting websites. :''My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlawRussia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.''

The joke was a parody of the opening line of that day's speech:

:''My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you that today I signed legislation that will allow student religious groups to begin enjoying a right they've too long been denied—the freedom to meet in public high schools during non-school hours, just as other student groups are allowed to do.''

Following his trip to Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

in 1959 and being refused entry into Disneyland

Disneyland is a amusement park, theme park at the Disneyland Resort in Anaheim, California. It was the first theme park opened by the Walt Disney Company and the only one designed and constructed under the direct supervision of Walt Disney, ...

, on security grounds, a dejected Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

joked, "...just now I was told that I could not go to Disneyland, I asked 'Why not?' What is it, do you have rocket launching pads there?" The only person more disappointed than Khrushchev was Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney ( ; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer, voice actor, and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the Golden age of American animation, American animation industry, he introduced several develop ...

himself, who claimed he had been looking forward to showing off his 'submarine fleet', which was actually the '' Submarine Voyage'' ride.

Arts

The United States and the Soviet Union engaged in competition vis-à-vis the arts. Cultural competition played out in Moscow, New York, London, and Paris. In 1946 America opened an exhibition called 'Advancing American Art' which gained popularity with the aims of expressing American art, in response the Soviets opened a respective exhibition showcasing Soviet Realism. The Soviets excelled atballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

and chess

Chess is a board game for two players. It is an abstract strategy game that involves Perfect information, no hidden information and no elements of game of chance, chance. It is played on a square chessboard, board consisting of 64 squares arran ...

, the Americans at jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

and abstract expressionist

Abstract expressionism in the United States emerged as a distinct art movement in the aftermath of World War II and gained mainstream acceptance in the 1950s, a shift from the American social realism of the 1930s influenced by the Great Depressi ...

paintings. The US funded its own ballet troupes, and both used ballet as political propaganda, using dance to reflect life style in the "battle for the hearts and minds of men." The defection of a premier dancer became a major coup.

Chess was inexpensive enough—and the Russians always won until America unleashed Bobby Fischer

Robert James Fischer (March 9, 1943January 17, 2008) was an American Grandmaster (chess), chess grandmaster and the eleventh World Chess Championship, World Chess Champion. A chess prodigy, he won his first of a record eight US Chess Champi ...

. Vastly more expensive was the Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

, as a proxy for scientific supremacy (with a technology with obvious military uses). As well when it came to sports the two countries both competed in the Olympics during the Cold War period which also created severe tension when the West boycotted the first Russian Olympics in 1980.

Music

1940s

As President Franklin D. Roosevelt died and World War II concluded with the detonation of nuclear weapons over Japan in 1945, the stage was quickly set for the emergence of Cold War hostilities between the new superpowers in 1946. Musicians concertizing in the United States during this period were suddenly exposed to rapidly shifting diplomatic and political circumstances. In 1946 the US State Department assumed control of thecultural diplomacy

Cultural diplomacy is a type of soft power that includes the "exchange of ideas, information, art, language and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding". The purpose of cultural diplomac ...

initiatives in South America which were initiated in 1941 by President Roosevelt's Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs

The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, later known as the Office for Inter-American Affairs, was a United States agency promoting inter-American cooperation (Pan-Americanism) during the 1940s, especially in commercial and econ ...

. At first, the State Department continued to encourage leading musicians to concertize and broadcast music in support of its Pan-Americanism

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, an association (a Union), and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means. The term Pan-Amer ...

policy in the region through its Office of International Broadcasting and Cultural Affairs. As a result, live radio broadcasts to South America by such musicians as Alfredo Antonini, Néstor Mesta Cháyres and John Serry Sr. on CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS (an abbreviation of its original name, Columbia Broadcasting System), is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

's '' Viva América'' show continued into the first years of the cold war era. As the decade came to a close, however, the focal point for American foreign policy shifted toward the superpower rivalry in Europe and such cultural broadcasting to South America was gradually eliminated.

1950s and 1960s

Musicians of these decades, especially injazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

and folk music

Folk music is a music genre that includes #Traditional folk music, traditional folk music and the Contemporary folk music, contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be ca ...

, were influenced by the shadow of nuclear war. Probably the most famous, passionate and influential of all was Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan; born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Described as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture over his nearly 70-year ...

, notably in his songs " Masters of War" and "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall

"A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" is a song written by American musician and Nobel laureate Bob Dylan in the summer of 1962 and recorded later that year for his second studio album, '' The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan'' (1963). Its lyrical structure is based ...

" (written just before the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

). In 1965 Barry McGuire

Barry McGuire (born October 15, 1935) is an American singer-songwriter primarily known for his 1965 hit " Eve of Destruction". He was later a singer and songwriter of contemporary Christian music.

Early life

McGuire was born in Oklahoma City; ...

's version of P. F. Sloan's apocalyptic " Eve of Destruction" was a number one hit in the United States and elsewhere.

Van Cliburn