cocoliztli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

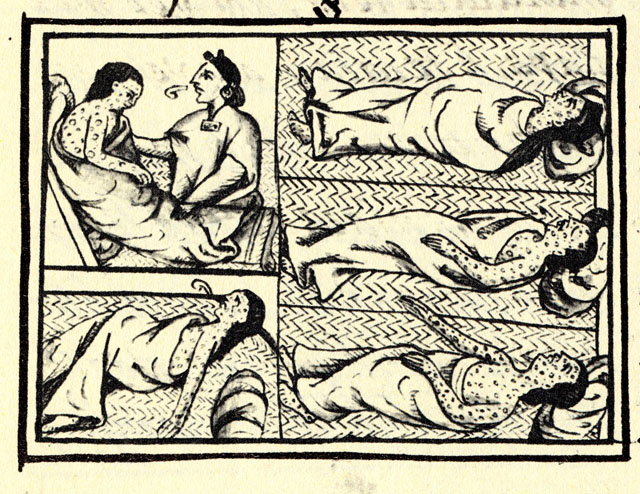

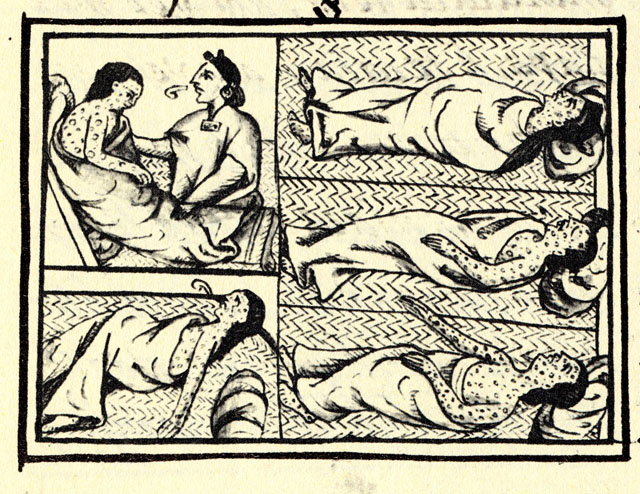

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in

At least 12 epidemics are attributed to ''cocoliztli'', with the largest occurring in 1545, 1576, 1736, and 1813. Soto ''et al.'' have hypothesized that a sizeable hemorrhagic fever outbreak could have contributed to the earlier collapse of the Classic Mayan civilization (AD 750–950). However, most experts believe other factors, including climate change, played a larger role.

''Cocoliztli'' epidemics usually occurred within two years of a major drought. The epidemic in 1576 occurred after a drought stretching from

At least 12 epidemics are attributed to ''cocoliztli'', with the largest occurring in 1545, 1576, 1736, and 1813. Soto ''et al.'' have hypothesized that a sizeable hemorrhagic fever outbreak could have contributed to the earlier collapse of the Classic Mayan civilization (AD 750–950). However, most experts believe other factors, including climate change, played a larger role.

''Cocoliztli'' epidemics usually occurred within two years of a major drought. The epidemic in 1576 occurred after a drought stretching from

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

during the 16th century. The Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

people called it ''cocoliztli'', Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

for pestilence. It ravaged the Mexican highlands in epidemic proportions, resulting in the demographic collapse of some Indigenous populations.

Based on the death toll, this outbreak is often referred to as the worst epidemic in the history of Mexico. Subsequent outbreaks continued to baffle both Spanish and native doctors, with little consensus among modern researchers on the pathogenesis

In pathology, pathogenesis is the process by which a disease or disorder develops. It can include factors which contribute not only to the onset of the disease or disorder, but also to its progression and maintenance. The word comes .

Descript ...

. However, recent bacterial genomic studies have suggested that Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

, specifically a serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or Cell (biology), cells are classified together based on their shared reactivity ...

of ''Salmonella enterica

''Salmonella enterica'' (formerly ''Salmonella choleraesuis'') is a rod-shaped, flagellate, facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative bacterium and a species of the genus ''Salmonella''. It is divided into six subspecies, arizonae (IIIa), diarizonae ...

'' known as Paratyphi C, was at least partially responsible for this initial outbreak. Others believe ''cocoliztli'' was caused by an indigenous viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of diseases. "Viral" means a health problem caused by infection from a virus, " hemorrhagic" means to bleed, and "fever" means an unusually high body temperature. Bleeding and fever are comm ...

, perhaps exacerbated by the worst drought

A drought is a period of drier-than-normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, ...

s to affect that region in 500 years and poor living conditions for Indigenous peoples of Mexico

Indigenous peoples of Mexico (), Native Mexicans () or Mexican Native Americans (), are those who are part of communities that trace their roots back to populations and communities that existed in what is now Mexico before the arrival of Europe ...

following the Spanish conquest

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It ...

( 1519).

History

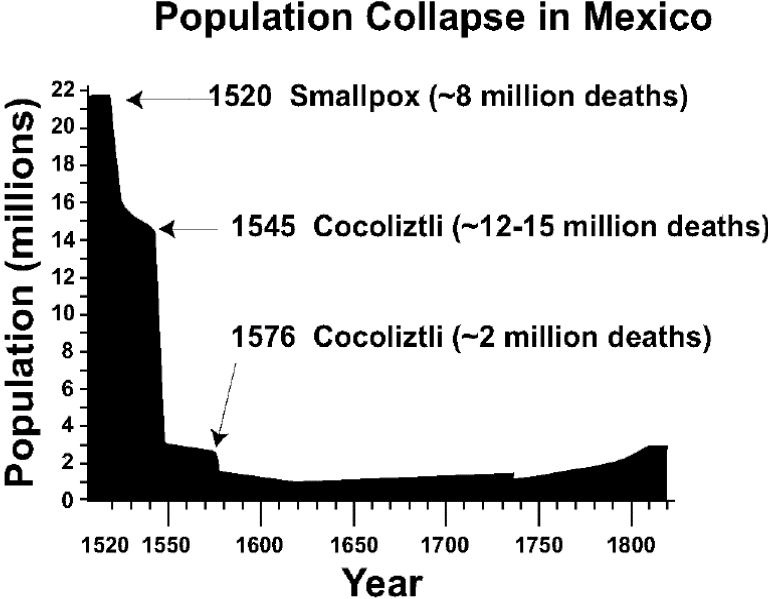

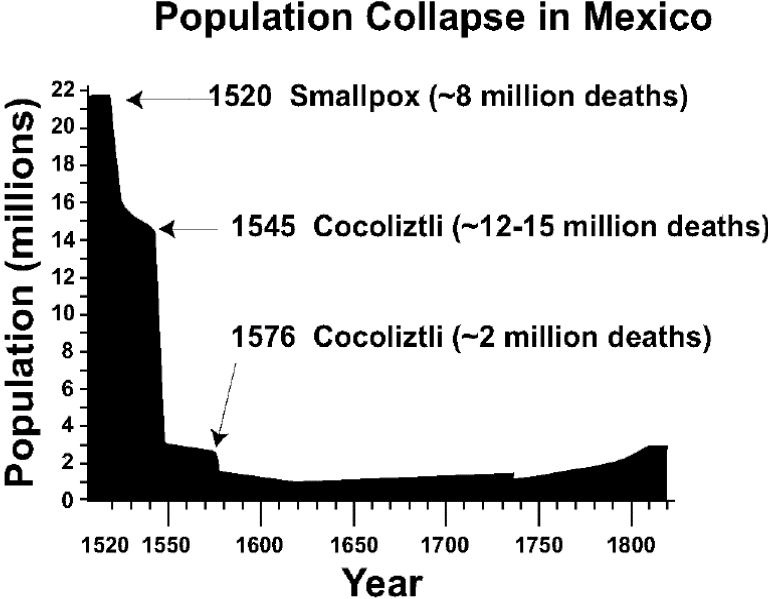

At least 12 epidemics are attributed to ''cocoliztli'', with the largest occurring in 1545, 1576, 1736, and 1813. Soto ''et al.'' have hypothesized that a sizeable hemorrhagic fever outbreak could have contributed to the earlier collapse of the Classic Mayan civilization (AD 750–950). However, most experts believe other factors, including climate change, played a larger role.

''Cocoliztli'' epidemics usually occurred within two years of a major drought. The epidemic in 1576 occurred after a drought stretching from

At least 12 epidemics are attributed to ''cocoliztli'', with the largest occurring in 1545, 1576, 1736, and 1813. Soto ''et al.'' have hypothesized that a sizeable hemorrhagic fever outbreak could have contributed to the earlier collapse of the Classic Mayan civilization (AD 750–950). However, most experts believe other factors, including climate change, played a larger role.

''Cocoliztli'' epidemics usually occurred within two years of a major drought. The epidemic in 1576 occurred after a drought stretching from Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. Proponents of the viral theory of ''cocoliztli'' suggest the relationship between drought and outbreak may reflect increased numbers of rodents

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

carrying viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of diseases. "Viral" means a health problem caused by infection from a virus, " hemorrhagic" means to bleed, and "fever" means an unusually high body temperature. Bleeding and fever are comm ...

during the rains that followed the drought.

''Cocoliztli'' seemed to preferentially, but not exclusively, target native people. Gonzalo de Ortiz, an ''encomendero

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including military protection and education. In pr ...

'', wrote ''"envió Dios tal enfermedad sobre ellos que de quarto partes de indios que avia se llevó las tres"'' (God sent down such sickness upon the Indians that three out of every four of them perished). Accounts by Toribio de Benavente Motolinia

Toribio of Benavente (1482, Benavente, Spain – 1565, Mexico City, New Spain), also known as Motolinía, was a Franciscan missionary who was one of the famous Twelve Apostles of Mexico who arrived in New Spain in May 1524. His published writing ...

, an early Spanish missionary, seem to contradict Ortiz’s sentiment by suggesting that 60–90% of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

's total population decreased, regardless of ethnicity. However, the modern consensus is that Indigenous people were most affected by ''cocoliztli'', followed by Africans. Europeans experienced lower mortality rates than other groups. One noteworthy European casualty of ''cocoliztli'' was Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún ( – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he jour ...

, a Spanish clergyman and author of the Florentine Codex, who contracted the disease in 1546. Sahagún suffered ''cocoliztli'' a second time in 1590 and subsequently died.

Sources and vectors

The social and physical environment of Colonial Mexico was likely key in allowing the outbreak of 1545–1548 to reach the heights that it did. Following the conquest, the Spanish colonists forced the Aztecs and other Indigenous peoples onto easily governable'' reducciones'' (congregations) that focused on agricultural production and conversion to Christianity. Weakened by war and chronic disease outbreaks, the native peoples' health suffered further under the new system. The ''reducciones'' brought people and animals in much closer contact with one another. Animals imported from the Old World were potential disease vectors for illnesses. The Aztecs and other Indigenous groups affected by the outbreak were disadvantaged due to their lack of exposure tozoonotic diseases

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (b ...

. Given that many Old World pathogens may have caused the ''cocoliztli'' outbreak, it is significant that all but two of the most common species of domestic mammalian livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

( llamas and alpacas being the exceptions) come from the Old World.

At the same time, droughts plagued Central America, with tree-ring data showing that the outbreak occurred during a megadrought

A megadrought is an exceptionally severe drought, lasting for many years and covering a wide area.

Definition

There is no exact definition of a megadrought. The term was first used by Connie Woodhouse and Jonathan Overpeck in their 1998 pap ...

. The lack of water may have worsened sanitation and hygiene. Megadroughts were reported before both the 1545 and 1576 outbreaks. Additionally, periodic rains during a supposed megadrought, such as those hypothesized for shortly before 1545, would have increased the presence of New World rats and mice. These animals may have carried arenavirus

An arenavirus is a bi- or trisegmented ambisense RNA virus that is a member of the family ''Arenaviridae''. These viruses infect rodents and occasionally humans. A class of novel, highly divergent arenaviruses, properly known as reptarenavirus ...

es capable of causing hemorrhagic fevers. The effects of drought and crowded settlements could explain disease transmission, especially if feces spread the pathogen.

Extent

Scholars suspect ''cocoliztli'' emerged in the southern and central Mexico Highlands, near modern-dayPuebla City

Puebla de Zaragoza (; ; ), formally Heroica Puebla de Zaragoza, formerly Puebla de los Ángeles during colonial times, or known simply as Puebla, is the seat of Puebla Municipality. It is the capital and largest city of the state of Puebla, and t ...

. Shortly after its initial onset, however, it may have spread as far north as Sinaloa

Sinaloa (), officially the (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, compose the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities, and its capital city is Culiacán Rosales.

It is located in northwest Mexic ...

and as south as Chiapas

Chiapas, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas, is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises Municipalities of Chiapas, 124 municipalities and its capital and large ...

and Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, where it was called ''gucumatz''. It may have spread to South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

to Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

and Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

, although it is hard to be certain that the same disease was described. The outbreak seemed to be limited to higher elevations, as it was nearly absent from coastal regions at sea level, e.g., the plains along the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

.

Symptoms

Although symptomatic descriptions of ''cocoliztli'' are similar to those ofOld World

The "Old World" () is a term for Afro-Eurasia coined by Europeans after 1493, when they became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia in the Eastern Hemisphere, previously ...

diseases, including measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, yellow fever, and typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, many researchers recognize it as a separate disease. According to Francisco Hernández de Toledo

Francisco Hernández de Toledo (c. 1515 – 28 January 1587) was a naturalist and court physician to Philip II of Spain. He was among the first wave of Spanish Renaissance physicians practicing according to the revived principles formulated by Hipp ...

, a physician who witnessed the outbreak in 1576, symptoms included high fever, severe headache, vertigo

Vertigo is a condition in which a person has the sensation that they are moving, or that objects around them are moving, when they are not. Often it feels like a spinning or swaying movement. It may be associated with nausea, vomiting, perspira ...

, black tongue, dark urine, dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

, severe abdominal and chest pain, head and neck nodules, neurological disorders, jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, and profuse bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethr ...

from the nose, eyes, and mouth. Some also describe spotted skin, gastrointestinal hemorrhaging, leading to bloody diarrhea, and bleeding from the eyes, mouth, and vagina.

The onset was rapid and without any precursors that would suggest one was sick. The disease was characterized by an extremely high level of virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

, with death often occurring within a week of the first symptoms, occasionally in as few as 3 or 4 days. Due to the virulence and effectiveness of the disease, recognizing its existence in the archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

has been difficult. This is because ''cocoliztli'', and other diseases that work rapidly, usually do not leave impacts (lesions) on the decedent's bones, despite causing significant damage to the gastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

, respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gr ...

, and other bodily systems.

Causes

Numerous 16th-century accounts detail the outbreak's devastation, but the symptoms do not match any known pathogen. Shortly after 1548, the Spanish started calling the disease ''tabardillo'' (typhus), which the Spanish had recognized since the late 15th century. However, the symptoms of ''cocoliztli'' were still not identical to the typhus or spotted fever observed in the Old World.Francisco Hernández de Toledo

Francisco Hernández de Toledo (c. 1515 – 28 January 1587) was a naturalist and court physician to Philip II of Spain. He was among the first wave of Spanish Renaissance physicians practicing according to the revived principles formulated by Hipp ...

, a Spanish physician, insisted on using the Nahuatl word when describing the disease to correspondents in the Old World. In 1970, a historian named Germaine Somolinos d'Ardois looked systematically at the proposed explanations, including hemorrhagic influenza, leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacterium ''Leptospira'' that can infect humans, dogs, rodents and many other wild and domesticated animals. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, Myalgia, muscle pains, a ...

, malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, typhus, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

, and yellow fever. According to Somolinos d'Ardois, none of these quite matched the 16th-century accounts of ''cocoliztli'', leading him to conclude the disease was a result of a "viral process of hemorrhagic influence." In other words, Somolinos d'Ardois believed ''cocoliztli'' was not the result of any known Old World pathogen but possibly a virus of New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

origins.

There are accounts of similar diseases striking Mexico in pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

times. The '' Codex Chimalpopoca'' states that an outbreak of bloody diarrhea occurred in Colhuacan in 1320. If the disease was indigenous, it was perhaps exacerbated by the worst drought

A drought is a period of drier-than-normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, ...

s to affect that region in 500 years and living conditions for Indigenous peoples of Mexico

Indigenous peoples of Mexico (), Native Mexicans () or Mexican Native Americans (), are those who are part of communities that trace their roots back to populations and communities that existed in what is now Mexico before the arrival of Europe ...

in the wake of the Spanish conquest

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It ...

( 1519). Some historians have suggested ''cocoliztli'' was typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, or smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, though the symptoms do not match.

Marr and Kiracofe attempted to build off this work by reexamining Hernandez's account of ''cocoliztli'' and comparing them with various clinical descriptions of other diseases. They suggested that scholars consider New World arenaviruses and the role these pathogens may have played in colonial disease outbreaks. Marr and Kiracofe theorized that arenavirus

An arenavirus is a bi- or trisegmented ambisense RNA virus that is a member of the family ''Arenaviridae''. These viruses infect rodents and occasionally humans. A class of novel, highly divergent arenaviruses, properly known as reptarenavirus ...

es, mainly affecting rodents, were not prominent in the pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

Americas. Consequently, rat and mice infestations brought upon by the arrival of the Spanish may have, combined with climatic and landscape change, brought these arenaviruses into much closer contact with people. Some subsequent research has focused on the viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of diseases. "Viral" means a health problem caused by infection from a virus, " hemorrhagic" means to bleed, and "fever" means an unusually high body temperature. Bleeding and fever are comm ...

diagnosis, placing increasing interest in the geographic spread of the disease.

In 2018, Johannes Krause, an evolutionary geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

The Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology () performs fundamental research into archaeological science. The institute is one of more than 80 research institutes of the Max Planck Society and is located in Jena, Germany.

History

Max Planc ...

, and colleagues discovered new evidence for an Old World culprit. DNA samples from the teeth of 29 sixteenth-century skeletons in the Oaxaca region of Mexico were identified as belonging to a rare strain of the bacterium ''Salmonella enterica'' (subsp. ''enterica'') which causes paratyphoid fever

Paratyphoid fever, also known simply as paratyphoid, is a bacterial infection caused by one of three types of '' Salmonella enterica''. Symptoms usually begin 6–30 days after exposure and are the same as those of typhoid fever. Often, a gradu ...

, suggesting that paratyphoid was the underlying fever behind the disease. The team extracted ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient sources (typically Biological specimen, specimens, but also environmental DNA). Due to degradation processes (including Crosslinking of DNA, cross-linking, deamination and DNA fragmentation, fragme ...

from the teeth of 29 individuals buried at Teposcolula-Yucundaa in Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

, Mexico. The Contact-era site has the only cemetery to be conclusively linked to victims of the outbreak of 1545–1548. The researchers recognized nonlocal microbial infections using the MEGAN alignment tool (MALT), a program that attempts to match fragments of extracted DNA with a database of bacterial genomes.

Within ten individuals, they identified ''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' serovar Paratyphi C, which causes enteric fevers in humans. This strain of ''Salmonella'' is unique to humans and was not found in any soil samples or pre-contact individuals that were used as controls. Enteric fevers, also known as typhoid or paratyphoid, are similar to typhus and were only distinguished from one another in the 19th century. Today, S. Paratyphi C continues to cause enteric fevers and, if untreated, has a mortality rate up to 15%. Infections are primarily limited to developing nations

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreemen ...

in Africa and Asia, although enteric fevers, in general, are still a health threat worldwide. Infections with S. Paratyphi C are rare, as most cases reported (about 27 million in 2000) resulted from serovars S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A.

The recent discovery of S. Paratyphi C within a 13th-century Norwegian cemetery supports these findings. A young female, who likely died from enteric fever, is proof that the pathogen was present in Europe over 300 years before the epidemics in Mexico. Thus, healthy carriers may have brought the bacteria to the New World, where it thrived. Generations of contact with the strain likely aided those who unknowingly carried the bacteria, as it is believed that S. Paratyphi C may have first transferred over to humans from swine in the Old World during or shortly after the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period.

Evolutionary geneticist, María Ávila-Arcos, has questioned this evidence since ''S. enterica's'' symptoms are poorly matched with the disease. Ávila-Arcos, Krause’s team, and authors of earlier historical analyses point out that RNA viruses, among other non-bacterial pathogens, have not been investigated. Others have noted that certain symptoms described, including gastrointestinal hemorrhaging, are not present in current observations of S. Paratyphi C infections. Ultimately, a more definitive proposal for the cause of any of the ''cocoliztli'' epidemics of 1545–1548 and 1576–1581 awaits further developments in ancient RNA analysis, and the causes of different outbreaks may differ.

Effects

Death toll

Beyond the estimations done by Motolinia and others for New Spain, most of the death toll figures cited for the outbreak of 1545–1548 are concerned with Aztec populations. Around 800,000 died in theValley of Mexico

The Valley of Mexico (; ), sometimes also called Basin of Mexico, is a highlands plateau in central Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico was a centre for several pre-Columbian civilizations including Teotihuacan, ...

, which led to the widespread abandonment of many Indigenous sites in the area during or shortly after this four-year period. Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during this epidemic have ranged from 5 to 15 million people, making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time.

Other

The effects of the outbreak extended beyond just a loss in terms of population. The lack of Indigenous labor led to a sizeable food shortage, affecting the natives and the Spanish colonists. The death of many Aztecs due to the epidemic led to a void in land ownership, with Spanish colonists of all backgrounds looking to exploit these now vacant lands. Coincidentally, the Spanish Emperor,Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

, had been seeking a way to disempower the ''encomenderos'' and establish a more efficient and "ethical" settlement system.

Starting around the end of the outbreak in 1549, the ''encomederos'', impacted by the loss in profits resulting and unable to meet the demands of New Spain, were forced to comply with the new ''tasaciones'' (regulations). The new ordinances, known as '' Leyes Nuevas,'' aimed to limit the amount of tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of lands which the state con ...

''encomenderos'' could demand while also prohibiting them from exercising absolute control over the labor force. Simultaneously, non-''encomenderos'' began claiming lands lost by the ''encomenderos'', as well as the labor provided by the Indigenous people. This developed into implementing the ''repartimiento

The ''Repartimiento'' () (Spanish, "distribution, partition, or division") was a colonial labor system imposed upon the indigenous population of Spanish America and the Philippines. In concept, it was similar to other tribute-labor systems, such a ...

'' system, which sought to institute a higher level of oversight within the Spanish colonies and maximize the overall tribute extracted for public and crown use. Rules regarding tribute itself were also changed in response to the epidemic of 1545, as fears over future food shortages ran rampant among the Spanish. By 1577, after years of debate and a second major outbreak of ''cocoliztli'', maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

and money were designated as the only two forms of acceptable tribute.

Jennifer Scheper Hughes has argued that after decades of minimal success in Mexico, European missionaries were facing a crisis of faith. Indigenous Catholics, in contrast, turned to the Church, finding power, influence, and their own forms of worship.

Later outbreaks

A second large outbreak of ''cocoliztli'' occurred in 1576, lasting until about 1580. Although less destructive than its predecessor, causing approximately two million deaths, this outbreak appears in much greater detail in colonial accounts. Many of the descriptions of ''cocoliztli'' symptoms, beyond the bleeding, fevers, and jaundice, were recorded during this epidemic. There are 13 cocoliztli epidemics cited in Spanish accounts between 1545 and 1642, with a later outbreak in 1736 taking a similar form but referred to as ''tlazahuatl''.See also

*Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the New World (the Americas) in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemis ...

* Ecological imperialism

* Millenarianism in colonial societies

Millenarianism is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". These movements have been especially common among people living und ...

* Virgin soil epidemic

In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen. Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European ...

* Native American disease and epidemics

The history of Native American disease and epidemics is fundamentally composed of two elements: indigenous diseases and those brought by settlers to the Americas from the Old World (Africa, Asia, and Europe).

Although a variety of infecti ...

* History of smallpox in Mexico

Citations

oGeneral and cited references

* *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cocoliztli epidemic, 1576 1545 disasters 1545 in health 16th-century disease outbreaks 1576 disasters 1576 in health 1545 in New Spain 1576 in New Spain 16th-century epidemics Colonial Mexico Disease outbreaks in Mexico Salmonella Hemorrhagic fevers outbreaks