Clinton Engineering Works on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the

In 1942, the

In 1942, the

Although War Department policy maintained that land should be acquired by direct purchase, time was short and thus it was decided to proceed immediately with condemnation. This allowed access to the site for construction crews, provided faster compensation to the owners, and expedited the handling of property with defective titles. On 28 September 1942, the ORD Real Estate Branch opened a project office in Harriman with a staff of 54 surveyors, appraisers, lawyers and office workers. The ORD Real Estate Branch was quite busy at this time, as it was also acquiring land for the

Although War Department policy maintained that land should be acquired by direct purchase, time was short and thus it was decided to proceed immediately with condemnation. This allowed access to the site for construction crews, provided faster compensation to the owners, and expedited the handling of property with defective titles. On 28 September 1942, the ORD Real Estate Branch opened a project office in Harriman with a staff of 54 surveyors, appraisers, lawyers and office workers. The ORD Real Estate Branch was quite busy at this time, as it was also acquiring land for the

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster by the S-1 Committee in June 1942. The design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September, Groves authorized construction of four more racetracks, known as Alpha II. Construction began in February 1943.

When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in November, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely. A more serious problem arose when the magnetic coils started shorting out. In December, Groves ordered a magnet broken open, and handfuls of rust were found inside. Groves then ordered the racetracks to be torn down and the magnets sent back to the factory to be cleaned. A

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster by the S-1 Committee in June 1942. The design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September, Groves authorized construction of four more racetracks, known as Alpha II. Construction began in February 1943.

When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in November, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely. A more serious problem arose when the magnetic coils started shorting out. In December, Groves ordered a magnet broken open, and handfuls of rust were found inside. Groves then ordered the racetracks to be torn down and the magnets sent back to the factory to be cleaned. A

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

that during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

produced the enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

. It consisted of production facilities arranged at three major sites, various utilities including a power plant

A power station, also referred to as a power plant and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility for the electricity generation, generation of electric power. Power stations are generally connected to an electr ...

, and the town of Oak Ridge. It was in East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 coun ...

, about west of Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located on the Tennessee River and had a population of 190,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division ...

, and was named after the town of Clinton, to the north. The production facilities were mainly in Roane County, and the northern part of the site was in Anderson County. The Manhattan District Engineer, Kenneth Nichols, moved the Manhattan District headquarters from Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

to Oak Ridge in August 1943. During the war, CEW's advanced research was managed for the government by the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

.

Construction workers were housed in a community known as Happy Valley. Built by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1943, this temporary community housed 15,000 people. The township of Oak Ridge was established to house the production staff. The operating force peaked at 50,000 workers just after the end of the war. The construction labor force peaked at 75,000, and the combined employment peak was 80,000. The town was developed by the federal government as a segregated community; Black American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

s lived only in an area known as Gamble Valley, in government-built "hutments" (one-room shacks) on the south side of what is now Tuskegee Drive.

Site selection

In 1942, the

In 1942, the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

was attempting to construct the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

s. This would require production facilities, and by June 1942 the project had reached the stage where their construction could be contemplated. On 25 June, the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May ...

(OSRD) S-1 Executive Committee deliberated on where they should be located. Brigadier General Wilhelm D. Styer recommended that the different manufacturing facilities be built at the same site in order to simplify security and construction. Such a site would require a substantial tract of land to accommodate both the facilities and housing for the thousands of workers. The plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

processing plant needed to be from the site boundary and any other installation, in case radioactive fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

escaped. While security and safety concerns suggested a remote site, it still needed to be near sources of labor and accessible by road and rail transportation. A mild climate that allowed construction to proceed throughout the year was desirable. Terrain separated by ridges would reduce the impact of accidental explosions, but they could not be so steep as to complicate construction. The substratum

Substrata, plural of substratum, may refer to:

*Earth's substrata, the geologic layering of the Earth

*''Hypokeimenon'', sometimes translated as ''substratum'', a concept in metaphysics

*Substrata (album), a 1997 ambient music album by Biosphere

* ...

needed to be firm enough to provide good foundations but not so rocky that it would hinder excavation work. It was estimated that the proposed plants would need access to 150,000 kW of electrical power and of water per minute. A War Department policy held that, as a rule, munitions facilities should not be located west of the Sierra or Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington (state), Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as m ...

s, east of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

, or within of the Canadian or Mexican borders.

Several sites were considered in the Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North C ...

, two in the Chicago area, one near the Shasta Dam

Shasta Dam (called Kennett Dam before its construction) is a concrete arch-gravity dam across the Sacramento River in Northern California in the United States. At high, it is the eighth-tallest dam in the United States. Located at the north e ...

in California, and some in Washington state

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

, where the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It has also been known as SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear R ...

was eventually established. An OSRD team had selected the Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located on the Tennessee River and had a population of 190,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division ...

area in April 1942, and in May Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

, the director of the Metallurgical Laboratory, had met with Gordon R. Clapp, the general manager of the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

(TVA). The Chief Engineer of the Manhattan District (MED), Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

James C. Marshall, asked Colonel Leslie R. Groves Jr. to undertake a study within the Army's Office of the Chief of Engineers

The Chief of Engineers is a principal United States Army staff officer at The Pentagon. The Chief advises the Army on engineering matters, and serves as the Army's topographer and proponent for real estate and other related engineering programs. ...

. After receiving assurances that the TVA could supply the required quantity of electric power if given priority for procuring some needed equipment, Groves also concluded that the Knoxville area was suitable. The only voice of dissent at the 25 June meeting was Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American accelerator physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation for ...

, who wanted the electromagnetic separation plant located much nearer to his Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 3 ...

in California. The Shasta Dam area remained under consideration for the electromagnetic plant until September, by which time Lawrence had dropped his objection.

On 1 July, Marshall and his deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Nichols, surveyed sites in the Knoxville area with representatives of the TVA and Stone & Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the earl ...

, the designated construction contractor. No perfectly suitable site was found, and Marshall even ordered another survey of the Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the most populous city in eastern Washington and the county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It lies along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south o ...

area. At the time, the proposed nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

, gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radiu ...

and gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

technologies were still in the research stage, and the design of the plant was a long way off. The schedules—which called for construction work on the nuclear reactor to commence by 1 October 1942, the electromagnetic plant by 1 November, the centrifugal plant by 1 January 1943, and the gaseous diffusion plant by 1 March—were unrealistic. While work could not commence on the plants, a start could be made on the housing and administrative buildings. Stone & Webster therefore drew up a detailed report on the most promising site west of Knoxville. Stephane Groueff later wrote:

The site was located in Roane County and Anderson County and lay roughly halfway between the two county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or parish (administrative division), civil parish. The term is in use in five countries: Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, and the United States. An equiva ...

s of Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

and Clinton. Its greatest drawback was that a major road, Tennessee State Route 61, ran through it. Stone & Webster considered the possibility of re-routing the road. The Ohio River Division of the Corps of Engineers estimated that it would cost $4.25 million (equivalent to $ in ) to purchase the entire site.

Groves became the director of the Manhattan Project on 23 September, with the rank of brigadier general. That afternoon, he took a train to Knoxville, where he met with Marshall. After touring the site, Groves concluded that the site "was an even better choice than I had anticipated". He called Colonel John J. O'Brien of the Corps of Engineers' Real Estate Branch and told him to proceed with acquiring the land. The site was initially known as the Kingston Demolition Range; it officially became the Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) in January 1943 and was given the codename Site X. After the township was established in mid-1943, the name Oak Ridge was chosen from employee suggestions. The site met the Manhattan District's approval because "its rural connotation held outside curiosity to a minimum". Oak Ridge then became the site's postal address, but the site was not officially renamed Oak Ridge until 1947.

Land acquisition

Although War Department policy maintained that land should be acquired by direct purchase, time was short and thus it was decided to proceed immediately with condemnation. This allowed access to the site for construction crews, provided faster compensation to the owners, and expedited the handling of property with defective titles. On 28 September 1942, the ORD Real Estate Branch opened a project office in Harriman with a staff of 54 surveyors, appraisers, lawyers and office workers. The ORD Real Estate Branch was quite busy at this time, as it was also acquiring land for the

Although War Department policy maintained that land should be acquired by direct purchase, time was short and thus it was decided to proceed immediately with condemnation. This allowed access to the site for construction crews, provided faster compensation to the owners, and expedited the handling of property with defective titles. On 28 September 1942, the ORD Real Estate Branch opened a project office in Harriman with a staff of 54 surveyors, appraisers, lawyers and office workers. The ORD Real Estate Branch was quite busy at this time, as it was also acquiring land for the Dale Hollow Reservoir

The Dale Hollow Reservoir is a reservoir situated on the Kentucky/Tennessee border. The lake is formed by the damming of the Obey River, above its juncture with the Cumberland River at river mile 380. Portions of the lake also cover the Wolf Riv ...

, so some staff were borrowed from the Federal Land Bank and the TVA. The next day, Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson

Robert Porter Patterson Sr. (February 12, 1891 – January 22, 1952) was an American judge who served as United States Under Secretary of War, Under Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and US Secretary of War, U.S. Secretary of ...

authorized the acquisition of at an estimated cost of $3.5 million (equivalent to $ in ). At the request of the ORD Real Estate Branch attorneys, the District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee issued an order of possession on 6 October, effective the next day. Recognizing the hardship that it would cause to the landowners, it restricted immediate exclusive possession to properties "essential to full and complete development of the project".

Over 1,000 families lived on the site on farms or in the hamlets of Elza, Robertsville, and Scarboro. The first that most heard about the acquisition was when a representative from the ORD visited to inform them that their land was being acquired. Some returned home from work one day to find an eviction notice nailed to their door or to a tree in the yard. Most were given six weeks to leave, but some were given just two. The government took possession of 13 tracts for immediate construction work on 20 November 1942. By May 1943, 742 declarations had been filed covering . Most residents were told to prepare to leave between 1 December and 15 January. In cases where this would cause undue hardship, the MED allowed residents to stay beyond this date. For some it was the third time that they had been evicted by the government, having previously been evicted for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States in the southeastern United States, southeast, with parts in North Carolina and Tennessee. The park straddles the ridgeline o ...

in the 1920s and the TVA's Norris Dam in the 1930s. Many expected that, like the TVA, the Army would provide assistance to help them relocate; but unlike the TVA, the Army had no mission to improve the area or the lot of the local people, and thus no funds had been allocated for the purpose. Tires were in short supply in wartime America, and moving vehicles were difficult to find. Some residents had to leave behind possessions that they were unable to take with them.

A delegation of landowners presented the ORD Real Estate Branch with a petition protesting the acquisition of their property on 23 November 1942, and that night over 200 landowners held a meeting at which they agreed to hire lawyers and appraisers to challenge the federal government. Local newspapers and politicians were sympathetic to their cause. By the end of May 1943, agreements were reached covering 416 tracts totaling , but some landowners rejected the government's offers. The ORD Real Estate Branch invoked a procedure under Tennessee law that allowed for a jury of five citizens appointed by the federal district court to review the compensations offered. They handled five cases in which they proposed higher values than those of the ORD appraisers, but the landowners rejected them as well, so the Army discontinued the use of this method. In response to rising public criticism, O'Brien commissioned a review by the Department of Agriculture

An agriculture ministry (also called an agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister f ...

. It found that the appraisals had been fair and just, and that farmers had overestimated the size and productivity of their land.

The landowners turned to their local Congressman

A member of congress (MOC), also known as a congressman or congresswoman, is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The t ...

, John Jennings, Jr. On 1 February 1943, Jennings introduced a resolution in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

calling for a committee to investigate the values offered to the landowners. He also complained to Patterson that buildings and facilities were being demolished by the MED. On 9 July, Andrew J. May, the chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs, appointed an investigating subcommittee chaired by Tennessee Representative Clifford Davis, who selected Dewey Short of Missouri and John Sparkman

John Jackson Sparkman (December 20, 1899 – November 16, 1985) was an American jurist and politician from the state of Alabama. A Southern Democrat, Sparkman served in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1946 and the United ...

of Alabama as its other members. Public hearings were held in Clinton on 11 August and in Kingston the following day. The committee report, presented in December 1943, made a number of specific recommendations concerning the Corps of Engineers' land acquisition process, but neither Congress nor the War Department moved to provide additional compensation for the landowners.

In July 1943, Groves prepared to issue Public Proclamation No. 2, declaring the site a military exclusion area. He asked Marshall to present it to Governor of Tennessee

The governor of Tennessee is the head of government of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the commander-in-chief of the U.S. state, state's Tennessee Military Department, military forces. The governor is the only official in the Government of Tenne ...

Prentice Cooper. Marshall, in turn, delegated the task to the area engineer, Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Thomas T. Crenshaw, who sent a junior officer, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

George B. Leonard. Cooper was unimpressed; he told Leonard that he had not been informed about the purpose of the CEW and that the Army had kicked the farmers off their land and had not compensated the counties for the roads and bridges which would be closed. In his opinion it was "an experiment in socialism", a New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

project being undertaken in the name of the war effort. Instead of reading the proclamation, he tore it up and threw it in a waste paper basket. Marshall went to Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

to apologize to Cooper, who refused to talk to him. Nichols, who succeeded Marshall as chief engineer of the Manhattan District, met Cooper on 31 July and offered compensation in the form of federal financing for road improvements. Cooper accepted an offer from Nichols to visit the CEW, which he did on 3 November.

Nichols and Cooper came to an agreement about the Solway Bridge. Although it was in Knox County, Anderson County had contributed $27,000 towards its construction. Knox County was still paying off the bonds, but the bridge was no longer accessible to the county and was usable only by CEW workers. Nichols negotiated a deal in which Knox County was paid $25,000 annually for the bridge, of which $6,000 was to be used to maintain the access road. County Judge Thomas L. Seeber then threatened to close the Edgemoor Bridge unless Anderson County was similarly compensated. An agreement was reached under which Anderson County received $10,000 for the bridge and $200 per month. Knox County did not keep its side of the bargain to maintain the road, which was damaged by heavy traffic and became impassable after torrential rains in 1944. The Army was forced to spend $5,000 per month on road works in Knox County.

Additional parcels of land were acquired during 1943 and 1944 for access roads, a railway spur, and for security purposes, bringing the total to about . The Harriman office closed on 10 June 1944 but reopened on 1 September to deal with the additional parcels. The final acquisition was completed on 1 March 1945. The final cost of the land acquired was around $2.6 million (equivalent to $ in ), about $47 per acre.

Facilities

X-10 graphite reactor

On 2 February 1943,DuPont

Dupont, DuPont, Du Pont, duPont, or du Pont may refer to:

People

* Dupont (surname) Dupont, also spelled as DuPont, duPont, Du Pont, or du Pont is a French surname meaning "of the bridge", historically indicating that the holder of the surname re ...

began construction of the plutonium semiworks on an isolated site in Bethel Valley about southwest of Oak Ridge. Intended as a pilot plant

A pilot plant is a pre-commercial production system that employs new production technology and/or produces small volumes of new technology-based products, mainly for the purpose of learning about the new technology. The knowledge obtained is then ...

for the larger production facilities at the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It has also been known as SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear R ...

, it included the air-cooled graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

- moderated X-10 Graphite Reactor. There was also a chemical separation plant, research laboratories, waste storage area, training facility for Hanford staff, and administrative and support facilities that included a laundry, cafeteria, first aid center and fire station. Because of the subsequent decision to construct water-cooled reactors at Hanford, only the chemical separation plant operated as a true pilot. The facility was known as the Clinton Laboratories and was operated by the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

as part of the Metallurgical Laboratory project.

The X-10 Graphite Reactor was the world's second artificial nuclear reactor after Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

's Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

and was the first reactor designed and built for continuous operation. It consisted of a block, long on each side, of nuclear graphite cubes, weighing around , surrounded by of high-density concrete as a radiation shield. There were 36 horizontal rows of 35 holes. Behind each was a metal channel into which uranium fuel slugs could be inserted. The cooling system was driven by three large electric fans.

Construction work on the reactor had to wait until DuPont had completed the design. Excavation commenced on 27 April 1943, but a large pocket of soft clay was discovered, necessitating additional foundations. Further delays occurred from wartime difficulties in procuring building materials. There was also an acute shortage of common and skilled labor: the contractor had only three-quarters of the required workforce, and less after high turnover and absenteeism, mainly the result of poor accommodations and difficulties in commuting. The township of Oak Ridge was still under construction, and barracks were built to house workers. Special arrangements with individual workers increased their morale and reduced turnover. Further delays were caused by unusually heavy rainfall, with falling in July 1943, more than twice the average of .

of graphite blocks were purchased from National Carbon, and the construction crews began stacking it in September 1943. Cast uranium billets came from Metal Hydrides, Mallinckrodt

Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals plc is an American-Irish domiciled manufacturer of specialty pharmaceuticals (namely, adrenocorticotropic hormone), generic drugs and imaging agents. In 2017, it generated 90% of its sales from the U.S. healthcare s ...

and other suppliers. These were extruded into cylindrical slugs and canned by Alcoa

Alcoa Corporation (an acronym for "Aluminum Company of America") is an American industrial corporation. It is the world's eighth-largest producer of aluminum. Alcoa conducts operations in 10 countries. Alcoa is a major producer of primary alu ...

, which started production on 14 June 1943. General Electric and the Metallurgical Laboratory developed a new welding technique; the new equipment was installed in the production line at Alcoa in October 1943. Supervised by Compton, Martin D. Whitaker and Fermi, the reactor went critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

* Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing i ...

on 4 November with about of uranium. A week later the load was increased to , raising its power generation to 500 kW, and by the end of the month the first 500 mg of plutonium was created. Modifications over time raised the power to 4,000 kW in July 1944.

Construction commenced on the pilot separation plant before a chemical process for separating plutonium from uranium had been selected. In May 1943, DuPont managers decided to use the bismuth phosphate process. The plant consisted of six cells, separated from each other and the control room by thick concrete walls. The equipment was operated remotely from the control room. Construction work was completed on 26 November, but the plant could not operate until the reactor started producing irradiated uranium slugs. The first batch was received on 20 December, allowing the first plutonium to be produced in early 1944. By February, the reactor was irradiating a ton of uranium every three days. Over the next five months, the efficiency of the separation process was improved, with the percentage of plutonium recovered increasing from 40 to 90 percent. X-10 operated as a plutonium production plant until January 1945, when it was turned over to research activities. By this time, 299 batches of irradiated slugs had been processed.

In September 1942, Compton asked Whitaker to form a skeleton operating staff for X-10. Whitaker became director of the Clinton Laboratories, and the first permanent operating staff arrived at X-10 from the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago in April 1944, by which time DuPont began transferring its technicians to the site. They were augmented by one hundred technicians in uniform from the Army's Special Engineer Detachment. By March 1944, there were 1,500 people working at X-10.

A radioisotope

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess numbers of either neutrons or protons, giving it excess nuclear energy, and making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ...

building, a steam plant, and other structures were added in April 1946 to support the laboratory's peacetime educational and research missions. All work was completed by December, adding another $1,009,000 (equivalent to $ in ) to the cost of construction at X-10 and bringing the total cost to $13,041,000 (equivalent to $ in ). Operational costs added $22,250,000 (equivalent to $ in ).

Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant

Electromagnetic isotope separation was developed by Lawrence at the University of California Radiation Laboratory. This method employed devices known ascalutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derive ...

s, a hybrid of the standard laboratory mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

and cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

. The name was derived from the words "California", "university" and "cyclotron". In the electromagnetic separation process, a magnetic field deflects charged uranium particles according to mass. The process was neither scientifically elegant nor industrially efficient. Compared with a gaseous diffusion plant or a nuclear reactor, an electromagnetic separation plant would consume more scarce materials, require more manpower to operate, and cost more to build. The process was approved because it was based on proven technology and therefore represented less risk. It could be built in stages and rapidly reach industrial capacity.

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster by the S-1 Committee in June 1942. The design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September, Groves authorized construction of four more racetracks, known as Alpha II. Construction began in February 1943.

When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in November, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely. A more serious problem arose when the magnetic coils started shorting out. In December, Groves ordered a magnet broken open, and handfuls of rust were found inside. Groves then ordered the racetracks to be torn down and the magnets sent back to the factory to be cleaned. A

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster by the S-1 Committee in June 1942. The design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September, Groves authorized construction of four more racetracks, known as Alpha II. Construction began in February 1943.

When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in November, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely. A more serious problem arose when the magnetic coils started shorting out. In December, Groves ordered a magnet broken open, and handfuls of rust were found inside. Groves then ordered the racetracks to be torn down and the magnets sent back to the factory to be cleaned. A pickling

Pickling is the process of food preservation, preserving or extending the shelf life of food by either Anaerobic organism, anaerobic fermentation (food), fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The pickling procedure typically affects t ...

plant was established on-site to clean the pipes and fittings. The second Alpha I became operational near the end of January 1944; the first Beta and first and third Alpha I's came online in March, and the fourth Alpha I became operational in April. The four Alpha II racetracks were completed between July and October 1944.

Tennessee Eastman was hired to manage Y-12 on the usual cost-plus

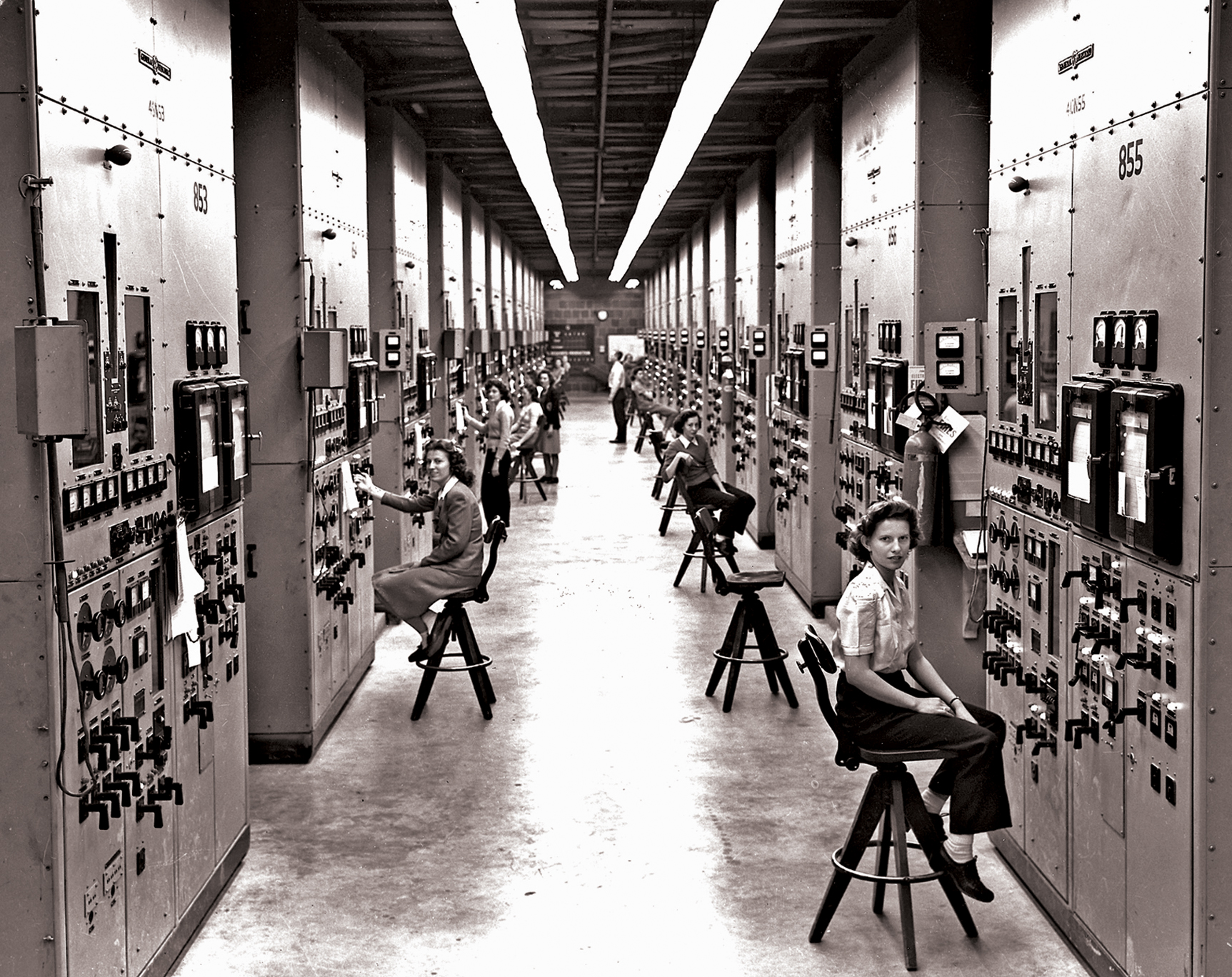

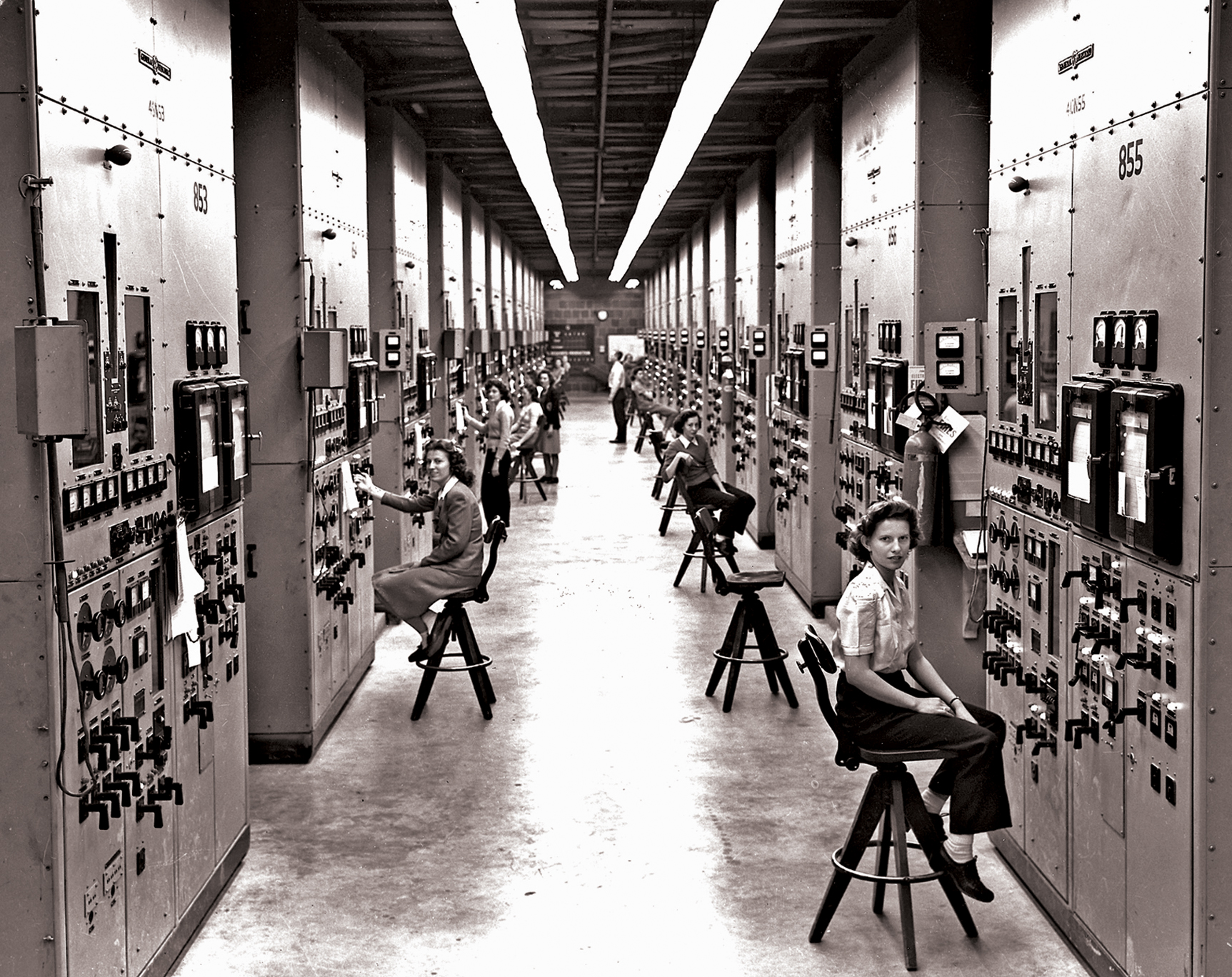

A cost-plus contract, also termed a cost plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, ''plus'' an additional payment to allow for risk and incentive sharing.Calutron Girls, were outperforming his doctorate-level scientists. They agreed to a production race and Lawrence lost, a morale boost for the Tennessee Eastman workers and supervisors. The girls were "trained like soldiers not to reason why", while "the scientists could not refrain from time-consuming investigation of the cause of even minor fluctuations of the dials".

Y-12 initially enriched the

The most promising but also the most challenging method of isotope separation was

The most promising but also the most challenging method of isotope separation was

The

The

The Army presence at Oak Ridge increased in August 1943 when Nichols replaced Marshall as head of the Manhattan Engineer District. One of his first tasks was to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although the name of the district did not change. In September 1943 the administration of community facilities was outsourced to Turner Construction Company through a subsidiary, the Roane-Anderson Company. The company was paid a fee of $25,000 per month on a cost-plus contract, about 1 percent of the $2.8 million monthly cost of running the town facilities. Roane-Anderson did not take over everything at once, and a phased takeover started with Laundry No. 1 on 17 October 1943; transportation and garbage collection soon followed. It assumed responsibility for water and sewage in November and electricity in January 1944. The number of Roane-Anderson workers peaked at around 10,500 in February 1945, including concessionaires and subcontractors. Thereafter, numbers declined to 2,905 direct employees and 3,663 concessionaires and subcontractors when the Manhattan Project ended on 31 December 1946.

By mid-1943, it had become clear that the initial estimates of the size of the town had been too low, and a second phase of construction was required. Plans now called for a town of 42,000 people. Work began in the fall of 1943, and continued into the late summer of 1944. Only 4,793 of a planned total of 6,000 family houses were built, mostly on the East Town area and the undeveloped stretch along State Route 61. They were supplemented by 55 new dormitories, 2,089 trailers, 391 hutments, a

The Army presence at Oak Ridge increased in August 1943 when Nichols replaced Marshall as head of the Manhattan Engineer District. One of his first tasks was to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although the name of the district did not change. In September 1943 the administration of community facilities was outsourced to Turner Construction Company through a subsidiary, the Roane-Anderson Company. The company was paid a fee of $25,000 per month on a cost-plus contract, about 1 percent of the $2.8 million monthly cost of running the town facilities. Roane-Anderson did not take over everything at once, and a phased takeover started with Laundry No. 1 on 17 October 1943; transportation and garbage collection soon followed. It assumed responsibility for water and sewage in November and electricity in January 1944. The number of Roane-Anderson workers peaked at around 10,500 in February 1945, including concessionaires and subcontractors. Thereafter, numbers declined to 2,905 direct employees and 3,663 concessionaires and subcontractors when the Manhattan Project ended on 31 December 1946.

By mid-1943, it had become clear that the initial estimates of the size of the town had been too low, and a second phase of construction was required. Plans now called for a town of 42,000 people. Work began in the fall of 1943, and continued into the late summer of 1944. Only 4,793 of a planned total of 6,000 family houses were built, mostly on the East Town area and the undeveloped stretch along State Route 61. They were supplemented by 55 new dormitories, 2,089 trailers, 391 hutments, a  Although expected to accommodate the needs of the entire workforce, by late 1944 expansion of both the electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion plants led to forecasts of a population of 62,000. This prompted another round of construction that saw an additional 1,300 family units and 20 dormitories built. More shopping and recreational facilities were added, the schools were expanded to accommodate 9,000 students. Police and fire services were expanded, the telephone system was upgraded, and a 50-bed annex was added to the hospital.

The number of school children reached 8,223 in 1945. Few issues resonated more with the scientists and highly skilled workers than the quality of the education system. Although school staff were nominally employees of the Anderson County Education Board, the school system was run autonomously, with federal funding under the supervision of administrators appointed by the Army. Teachers enjoyed salaries that were considerably higher than those of Anderson County. The population of Oak Ridge peaked at 75,000 in May 1945, by which time 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works, and 10,000 by Roane-Anderson.

In addition to the township, there were a number of temporary camps established for construction workers. It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The largest, the trailer camp at Gamble Valley, had four thousand units. Another, at Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. The population of the construction camps declined as the construction effort tapered off, but they continued to be occupied in 1946.

The main shopping area was Jackson Square, with about 20 shops. The Army attempted to keep prices down by encouraging competition, but this met with limited success due to the captive nature of the population, and the requirements of security, which meant that firms and goods could not freely move in and out. The Army could give prospective concessionaires only vague information about how many people were in or would be in the town, and concessions were only for the duration of the war. Concessions were therefore charged a percentage of their profits in rental rather than a fixed fee. The Army avoided imposing draconian price controls, but limited prices to those of similar goods in Knoxville. By 1945, community amenities included 6 recreation halls, 36 bowling alleys, 23 tennis courts, 18 ball parks, 12 playgrounds, a swimming pool, a 9,400-volume library, and a newspaper.

Although expected to accommodate the needs of the entire workforce, by late 1944 expansion of both the electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion plants led to forecasts of a population of 62,000. This prompted another round of construction that saw an additional 1,300 family units and 20 dormitories built. More shopping and recreational facilities were added, the schools were expanded to accommodate 9,000 students. Police and fire services were expanded, the telephone system was upgraded, and a 50-bed annex was added to the hospital.

The number of school children reached 8,223 in 1945. Few issues resonated more with the scientists and highly skilled workers than the quality of the education system. Although school staff were nominally employees of the Anderson County Education Board, the school system was run autonomously, with federal funding under the supervision of administrators appointed by the Army. Teachers enjoyed salaries that were considerably higher than those of Anderson County. The population of Oak Ridge peaked at 75,000 in May 1945, by which time 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works, and 10,000 by Roane-Anderson.

In addition to the township, there were a number of temporary camps established for construction workers. It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The largest, the trailer camp at Gamble Valley, had four thousand units. Another, at Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. The population of the construction camps declined as the construction effort tapered off, but they continued to be occupied in 1946.

The main shopping area was Jackson Square, with about 20 shops. The Army attempted to keep prices down by encouraging competition, but this met with limited success due to the captive nature of the population, and the requirements of security, which meant that firms and goods could not freely move in and out. The Army could give prospective concessionaires only vague information about how many people were in or would be in the town, and concessions were only for the duration of the war. Concessions were therefore charged a percentage of their profits in rental rather than a fixed fee. The Army avoided imposing draconian price controls, but limited prices to those of similar goods in Knoxville. By 1945, community amenities included 6 recreation halls, 36 bowling alleys, 23 tennis courts, 18 ball parks, 12 playgrounds, a swimming pool, a 9,400-volume library, and a newspaper.

uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

content to between 13 and 15 percent and shipped the first few hundred grams of this to the Manhattan Project's weapons design laboratory, the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

, in March 1944. Only 1 part in 5,825 of the uranium feed emerged as final product; much of the rest was splattered over equipment in the process. Strenuous recovery efforts helped raise production to 10 percent of the uranium-235 feed by January 1945. In February the Alpha racetracks began receiving slightly enriched (1.4 percent) feed from the S-50 thermal diffusion plant, and the next month it received enhanced (5 percent) feed from the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant. By August K-25 was producing uranium sufficiently enriched to feed directly into the Beta tracks.

The Alpha tracks began to suspend operations on 4 September 1945 and ceased operation completely on 22 September. The last two Beta tracks went into full operation in November and December, processing feed from K-25 and K-27. By May 1946, studies suggested that the gaseous plants could fully enrich the uranium by themselves without accidentally creating a critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

. After a trial showed this was the case, Groves ordered all but one Beta track at Y-12 shut down in December 1946. Y-12 remained in use for nuclear weapons processing and materials storage. A production facility for the hydrogen bomb used in Operation Castle

Operation Castle was a United States series of high-yield (high-energy) nuclear tests by Joint Task Force 7 (JTF-7) at Bikini Atoll beginning in March 1954. It followed ''Operation Upshot–Knothole'' and preceded '' Operation Teapot''.

Con ...

in 1954 was hastily installed in 1952.

K-25 gaseous diffusion plant

The most promising but also the most challenging method of isotope separation was

The most promising but also the most challenging method of isotope separation was gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

. Graham's law

Graham's law of effusion (also called Graham's law of diffusion) was formulated by Scottish physical chemist Thomas Graham in 1848. Keith J. Laidler and John M. Meiser, ''Physical Chemistry'' (Benjamin/Cummings 1982), pp. 18–19 Graham fou ...

states that the rate of effusion

In physics and chemistry, effusion is the process in which a gas escapes from a container through a hole of diameter considerably smaller than the mean free path of the molecules. Such a hole is often described as a ''pinhole'' and the escape ...

of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molecular mass

The molecular mass () is the mass of a given molecule, often expressed in units of daltons (Da). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The derived quan ...

, so in a box containing a semi-permeable membrane and a mixture of two gases, the lighter molecules will pass out of the container more rapidly than the heavier molecules. The gas leaving the container is somewhat enriched in the lighter molecules, while the residual gas is somewhat depleted. The idea was that such boxes could be formed into a cascade of pumps and membranes, with each successive stage containing a slightly more enriched mixture. Research into the process was carried out at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

by a group that included Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

, Karl P. Cohen and John R. Dunning.

In November 1942 the Military Policy Committee approved the construction of a 600-stage gaseous diffusion plant. On 14 December, M. W. Kellogg accepted an offer to construct the plant, which was codenamed K-25. A cost-plus fixed fee contract was negotiated, eventually totaling $2.5 million (equivalent to $ in ). A separate corporate entity called Kellex was created for the project, headed by Percival C. Keith, one of Kellogg's vice presidents. The process faced formidable technical difficulties. The highly corrosive gas uranium hexafluoride

Uranium hexafluoride, sometimes called hex, is the inorganic compound with the formula . Uranium hexafluoride is a volatile, white solid that is used in enriching uranium for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

Preparation

Uranium dioxide is co ...

had to be used, as no substitute could be found, and the motors and pumps would have to be vacuum tight and enclosed in inert gas. The biggest problem was the design of the barrier, which would have to be strong, porous and resistant to corrosion by uranium hexafluoride. The best choice for this seemed to be nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

, and Edward Adler and Edward Norris created a mesh barrier from electroplated nickel. A six-stage pilot plant was built at Columbia to test the process, but the Norris-Adler prototype proved to be too brittle. A rival barrier was developed from powdered nickel by Kellex, the Bell Telephone Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

and the Bakelite

Bakelite ( ), formally , is a thermosetting polymer, thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. The first plastic made from synthetic components, it was developed by Belgian chemist ...

Corporation. In January 1944, Groves ordered the Kellex barrier into production.

Kellex's design for K-25 called for a four-story U-shaped structure long containing 54 contiguous buildings. These were divided into nine sections. Within these were cells of six stages. The cells could be operated independently or consecutively within a section. Similarly, the sections could be operated separately or as part of a single cascade. A survey party began construction by marking out the site in May 1943. Work on the main building began in October, and the six-stage pilot plant was ready for operation on 17 April 1944. In 1945 Groves canceled the upper stages of the plant, directing Kellex to instead design and build a 540-stage side feed unit, which became known as K-27. Kellex transferred the last unit to the operating contractor, Union Carbide and Carbon, on 11 September 1945. The total cost, including the K-27 plant completed after the war, came to $480 million (equivalent to $ in ).

The production plant commenced operation in February 1945, and as cascade after cascade came online, the quality of the product increased. By April, K-25 had attained a 1.1 percent enrichment and the output of the S-50 thermal diffusion plant began being used as feed. Some product produced the next month reached nearly 7 percent enrichment. In August, the last of the 2,892 stages commenced operation. K-25 and K-27 achieved their full potential in the early postwar period, when they eclipsed the other production plants and became the prototypes for a new generation of plants. Uranium was enriched by the K-25 gaseous diffusion process until 1985; the plants were then decommissioned and decontaminated. A 235 MW coal-fired power station

A coal-fired power station or coal power plant is a thermal power station which burns coal to generate electricity. Worldwide there are about 2,500 coal-fired power stations, on average capable of generating a gigawatt each. They generate ...

was included for reliability and to provide variable frequency, although most electric power came from the TVA.

S-50 liquid thermal diffusion plant

The thermal diffusion process was based on Sydney Chapman and David Enskog'stheory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

, which explained that when a mixed gas passes through a temperature gradient, the heavier one tends to concentrate at the cold end and the lighter one at the warm end. Since hot gases tend to rise and cool ones tend to fall, this can be used as a means of isotope separation. This process was first demonstrated by Klaus Clusius

Klaus Paul Alfred Clusius (19 March 1903 – 28 May 1963) was a German physical chemist. During World War II, he worked on the German nuclear energy project, also known as the Uranium Club; he worked on isotope separation techniques and heavy wa ...

and Gerhard Dickel in Germany in 1938. It was developed by US Navy scientists but was not one of the enrichment technologies initially selected for use in the Manhattan Project. This was primarily due to doubts about its technical feasibility, but the inter-service rivalry between the Army and Navy also played a part.

The

The Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. Located in Washington, DC, it was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, appl ...

continued the research under Philip Abelson

Philip Hauge Abelson (April 27, 1913 – August 1, 2004) was an American physicist, scientific editor and science writer. Trained as a nuclear physicist, he co-discovered the element neptunium, worked on isotope separation in the Manhattan ...

's direction, but there was little contact with the Manhattan Project until April 1944, when Captain William S. Parsons (the naval officer in charge of ordnance development at Los Alamos) brought director Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

news of encouraging progress in the Navy's experiments on thermal diffusion. Oppenheimer wrote to Groves suggesting that the output of a thermal diffusion plant could be fed into Y-12. Groves set up a committee consisting of Warren K. Lewis, Eger Murphree and Richard Tolman

Richard Chace Tolman (March 4, 1881 – September 5, 1948) was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics and theoretical cosmology. He was a professor at the California In ...

to investigate the idea, and they estimated that a thermal diffusion plant costing $3.5 million (equivalent to $ in ) could enrich of uranium per week to nearly 0.9 percent uranium-235. Groves approved its construction on 24 June 1944.

Groves contracted with the H. K. Ferguson Company of Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

to build the thermal diffusion plant, which was designated S-50. Groves' advisers, Karl Cohen and W. I. Thompson from Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

, estimated that it would take six months to build; Groves gave Ferguson four months. Plans called for the installation of 2,142 diffusion columns arranged in 21 racks. Inside each column were three concentric tubes. Steam, obtained from the nearby K-25 powerhouse at a pressure of and temperature of , flowed downward through the innermost nickel pipe, while water at flowed upward through the outermost iron pipe. Isotope separation occurred in the uranium hexafluoride gas between the nickel and copper pipes.

Work commenced on 9 July 1944, and S-50 began partial operation in September. Ferguson operated the plant through a subsidiary known as Fercleve. The plant produced of 0.852 percent uranium-235 in October. Leaks limited production and forced shutdowns over the next few months, but in June 1945 it produced . By March 1945, all 21 production racks were operating.

Initially the output of S-50 was fed into Y-12. In early September Nichols appointed a production control committee, headed by Major A.V. (Pete) Peterson. Peterson's staff tried various combinations, using mechanical calculating machines, and decided that the S-50 production should be fed to K-25 rather than Y-12, which was done in April 1945. S-50 became the first stage, enriching from 0.71 percent to 0.89 percent. This material was fed into the gaseous diffusion process in the K-25 plant, which produced a product enriched to about 23 percent. This was, in turn, fed into Y-12.

Peterson's charts also showed that the proposed top stages for K-25 should be abandoned, as should Lawrence's recommendation to add more alpha stages to the Y-12 plant. Groves accepted the proposal to add more base units to the K-27 gaseous-diffusion plant and one more Beta stage track for Y-12. These additions were estimated to cost $100 million (equivalent to $ in ), with completion in February 1946. Soon after Japan surrendered in August 1945, Peterson recommended that S-50 be shut down. The Manhattan District ordered this on 4 September. The last uranium hexafluoride was sent to K-25, and the plant had ceased operation by 9 September. S-50 was completely demolished in 1946.

Electric power

Despite protests from TVA that it was unnecessary, the Manhattan District built a coal-fired power plant at K-25 with eight 25,000 KW generators. Steam generated from the K-25 power plant was subsequently used by S-50. Additional power lines were laid from the TVA hydroelectric plants at Norris Dam and Watts Bar Dam, and the Clinton Engineer Works was given its ownelectrical substation

A substation is a part of an electrical generation, transmission, and distribution system. Substations transform voltage from high to low, or the reverse, or perform any of several other important functions. Between the generating station an ...

s at K-25 and K-27. By 1945, power sources were capable of supplying Oak Ridge with up to 310,000 KW, of which 200,000 KW was earmarked for Y-12, 80,000 KW for K-25, 23,000 KW for the township, 6,000 KW for S-50 and 1,000 KW for X-10. Peak demand occurred in August 1945, when all the facilities were running. The peak load was 298,800 KW on 1 September.

The 235,000 KW steam plant was required for reliability; in 1953-55 a rat shorting out a transformer at CEW resulted in a complete loss of load and of several weeks of production. The plant could supply up to five different frequencies, although it was found that variable frequency was not necessary. J.A. Jones Construction built the plant and the gaseous diffusion plant. The site was cleared in June 1943, steam was available from one boiler in March 1944 and in April 15,000 KW was available from the first turbine generator. The plant was the largest single block of steam power built at one time, and with completion in January 1945 in record time.

Township

Planning for a "government village" to house the workers at the Clinton Engineer Works began in June 1942. Because the site was remote, it was believed more convenient and secure for the workers to live on the site. The gentle slopes of Black Oak Ridge, from which the new town of Oak Ridge got its name, were selected as a suitable location. Brigadier General Lucius D. Clay, the deputy chief of staff of the Army Services of Supply, reminded Marshall of a wartime limit of $7,500 per capita for individual quarters. Groves argued for "economy" with small and simple houses; but Marshall, who had argued for an exemption from the limit, saw no prospect that the kind of workers they needed would be willing to live with their family in substandard accommodation. The houses at CEW were basic but of a higher standard (as specified by Marshall and Nichols) than the houses at Los Alamos (as specified by Groves; and the quality of housing there suffered). The first plan, submitted by Stone & Webster on 26 October 1942, was for a residential community of 13,000 people. As Stone & Webster began work on the production facilities, it became clear that building the township as well would be beyond its capacity. The Army therefore engaged the architectural and engineering firmSkidmore, Owings & Merrill

SOM, an initialism of its original name Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, is a Chicago-based architectural, urban planning, and engineering firm. It was founded in 1936 by Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings. In 1939, they were joined by engineer ...

to design and build the township. The John B. Pierce Foundation were brought in as a consultant. In turn, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill brought in numerous subcontractors. This first phase of construction became known as the East Town. It included some 3,000 family dwellings, an administrative center, three shopping centers, three grade schools for 500 children each and a high school

A secondary school, high school, or senior school, is an institution that provides secondary education. Some secondary schools provide both ''lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper secondary education'' (ages 14 to 18), i.e., ...

for 500, recreation buildings, men's and women's dormitories, cafeterias, a medical services building and a 50-bed hospital. The emphasis was on speed of construction and getting around wartime shortages of materials. Where possible, fiberboard

Fiberboard (American English) or fibreboard (Commonwealth English) is a type of engineered wood product that is made out of wood fibers. Types of fiberboard (in order of increasing density) include particle board or low-density fiberboard (LDF ...

and gypsum board

Drywall (also called plasterboard, dry lining, wallboard, sheet rock, gib board, gypsum board, buster board, turtles board, slap board, custard board, gypsum panel and gyprock) is a panel made of calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum), with or witho ...

were used instead of wood, and foundations were made from concrete blocks rather than poured concrete. The work was completed in early 1944.

In addition to the East Town, a self-contained community known as the East Village, with 50 family units, its own church, dormitories and a cafeteria, was built near the Elza gate. This was intended as a segregated community for Black American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

s, but by the time it was completed, it was required by white people. Black people were instead housed in "hutments" (one-room shacks) in segregated areas, some in "family hutments" created by joining two regular hutments together.

The Army presence at Oak Ridge increased in August 1943 when Nichols replaced Marshall as head of the Manhattan Engineer District. One of his first tasks was to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although the name of the district did not change. In September 1943 the administration of community facilities was outsourced to Turner Construction Company through a subsidiary, the Roane-Anderson Company. The company was paid a fee of $25,000 per month on a cost-plus contract, about 1 percent of the $2.8 million monthly cost of running the town facilities. Roane-Anderson did not take over everything at once, and a phased takeover started with Laundry No. 1 on 17 October 1943; transportation and garbage collection soon followed. It assumed responsibility for water and sewage in November and electricity in January 1944. The number of Roane-Anderson workers peaked at around 10,500 in February 1945, including concessionaires and subcontractors. Thereafter, numbers declined to 2,905 direct employees and 3,663 concessionaires and subcontractors when the Manhattan Project ended on 31 December 1946.

By mid-1943, it had become clear that the initial estimates of the size of the town had been too low, and a second phase of construction was required. Plans now called for a town of 42,000 people. Work began in the fall of 1943, and continued into the late summer of 1944. Only 4,793 of a planned total of 6,000 family houses were built, mostly on the East Town area and the undeveloped stretch along State Route 61. They were supplemented by 55 new dormitories, 2,089 trailers, 391 hutments, a

The Army presence at Oak Ridge increased in August 1943 when Nichols replaced Marshall as head of the Manhattan Engineer District. One of his first tasks was to move the district headquarters to Oak Ridge, although the name of the district did not change. In September 1943 the administration of community facilities was outsourced to Turner Construction Company through a subsidiary, the Roane-Anderson Company. The company was paid a fee of $25,000 per month on a cost-plus contract, about 1 percent of the $2.8 million monthly cost of running the town facilities. Roane-Anderson did not take over everything at once, and a phased takeover started with Laundry No. 1 on 17 October 1943; transportation and garbage collection soon followed. It assumed responsibility for water and sewage in November and electricity in January 1944. The number of Roane-Anderson workers peaked at around 10,500 in February 1945, including concessionaires and subcontractors. Thereafter, numbers declined to 2,905 direct employees and 3,663 concessionaires and subcontractors when the Manhattan Project ended on 31 December 1946.

By mid-1943, it had become clear that the initial estimates of the size of the town had been too low, and a second phase of construction was required. Plans now called for a town of 42,000 people. Work began in the fall of 1943, and continued into the late summer of 1944. Only 4,793 of a planned total of 6,000 family houses were built, mostly on the East Town area and the undeveloped stretch along State Route 61. They were supplemented by 55 new dormitories, 2,089 trailers, 391 hutments, a cantonment

A cantonment (, , or ) is a type of military base. In South Asia, a ''cantonment'' refers to a permanent military station (a term from the British Raj). In United States military parlance, a cantonment is, essentially, "a permanent residential ...

area of 84 hutments and 42 barracks. Some 2,823 of the family units were prefabricated off-site. The high school was expanded to cater for 1,000 students. Two additional primary schools were built, and existing ones were expanded so that they could accommodate 7,000 students.

Although expected to accommodate the needs of the entire workforce, by late 1944 expansion of both the electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion plants led to forecasts of a population of 62,000. This prompted another round of construction that saw an additional 1,300 family units and 20 dormitories built. More shopping and recreational facilities were added, the schools were expanded to accommodate 9,000 students. Police and fire services were expanded, the telephone system was upgraded, and a 50-bed annex was added to the hospital.

The number of school children reached 8,223 in 1945. Few issues resonated more with the scientists and highly skilled workers than the quality of the education system. Although school staff were nominally employees of the Anderson County Education Board, the school system was run autonomously, with federal funding under the supervision of administrators appointed by the Army. Teachers enjoyed salaries that were considerably higher than those of Anderson County. The population of Oak Ridge peaked at 75,000 in May 1945, by which time 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works, and 10,000 by Roane-Anderson.

In addition to the township, there were a number of temporary camps established for construction workers. It was initially intended that the construction workers should live off-site, but the poor condition of the roads and a shortage of accommodations in the area made commuting long and difficult, and in turn made it difficult to find and retain workers. Construction workers therefore came to be housed in large hutment and trailer camps. The largest, the trailer camp at Gamble Valley, had four thousand units. Another, at Happy Valley, held 15,000 people. The population of the construction camps declined as the construction effort tapered off, but they continued to be occupied in 1946.

The main shopping area was Jackson Square, with about 20 shops. The Army attempted to keep prices down by encouraging competition, but this met with limited success due to the captive nature of the population, and the requirements of security, which meant that firms and goods could not freely move in and out. The Army could give prospective concessionaires only vague information about how many people were in or would be in the town, and concessions were only for the duration of the war. Concessions were therefore charged a percentage of their profits in rental rather than a fixed fee. The Army avoided imposing draconian price controls, but limited prices to those of similar goods in Knoxville. By 1945, community amenities included 6 recreation halls, 36 bowling alleys, 23 tennis courts, 18 ball parks, 12 playgrounds, a swimming pool, a 9,400-volume library, and a newspaper.