Cleisthenes (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cleisthenes ( ; ), or Clisthenes (), was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient

In 507 BC, during the time Cleisthenes was leading Athenian politics, and probably at his instigation, democratic

In 507 BC, during the time Cleisthenes was leading Athenian politics, and probably at his instigation, democratic

Perseus Project

*

BBC – History – The Democratic Experiment

* {{Authority control 6th-century BC Athenians Ancient legislators Alcmaeonidae Athenian democracy Eponymous archons 500s BC deaths 570s BC births Year of birth uncertain

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC

__NOTOC__

The year 508 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. In the Roman Empire it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Poplicola and Tricipitinus (or, less frequently, year 246 '' Ab urbe condita''). The denomination 508 BC for ...

. For these accomplishments, historians refer to him as "the father of Athenian democracy". He was a member of the aristocratic Alcmaeonid

The Alcmaeonidae (; , ; Attic: , ) or Alcmaeonids () were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological Alcmaeon, the great-grandson of Nestor.

In the 7th to late 5th ...

clan. He was the younger son of Megacles

Megacles or Megakles () was the name of several notable men of ancient Athens, as well as an officer of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

First archon

The first Megacles was possibly a legendary archon of Athens from 922 BC to 892 BC.

Archon eponymous

The s ...

and Agariste making him the maternal grandson of the tyrant Cleisthenes of Sicyon

Cleisthenes ( ; ) was the tyrant of Sicyon from , who aided in the First Sacred War against Kirrha that destroyed that city in 595 BC. He was also said to have organized a successful war against Argos because of his anti- Dorian feelings. After ...

. He was also credited with increasing the power of the Athenian citizens' assembly and for reducing the power of the nobility over Athenian politics.

In 510 BC, Spartan troops helped the Athenians overthrow the tyrant Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; ; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, and lectured on poetry, grammar, his ...

, son of Peisistratus

Pisistratus (also spelled Peisistratus or Peisistratos; ; – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular ...

. Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I (; Greek Κλεομένης; died c. 490 BC) was Agiad King of Sparta from c. 524 to c. 490 BC. One of the most important Spartan kings, Cleomenes was instrumental in organising the Greek resistance against the Persian Empire of Da ...

, king of Sparta, put in place a pro-Spartan oligarchy headed by Isagoras

Isagoras (), son of Tisander, was an Athenian aristocrat in the late 6th century BC.

He had remained in Athens during the tyranny of Hippias, but after Hippias was overthrown, he became involved in a struggle for power with Cleisthenes, a fello ...

. However, Cleisthenes, with the support of the middle class and aided by democrats, took over. Cleomenes intervened in 508 and 506 BC, but could not stop Cleisthenes and his Athenian supporters. Through Cleisthenes' reforms, the people of Athens endowed their city with isonomic

''Isonomia'' (ἰσονομία "equality of political rights,"Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English LexiconThe Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes", Mogens Herman Hansen, , p. 81-84 from the Greek ἴσος ''isos'' ...

institutions—equal rights for all citizens (though only free men and women were citizens)—and established ostracism

Ostracism (, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often us ...

as a punishment.

Biography

Historians estimate that Cleisthenes was born around 570 BC. A member of theAlcmaeonidae

The Alcmaeonidae (; , ; Attic: , ) or Alcmaeonids () were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narrati ...

family, Cleisthenes was the uncle of Pericles

Pericles (; ; –429 BC) was a Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Ancient Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and was acclaimed ...

' mother, Agariste, and of Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

' maternal grandfather, Megacles. He was the son of Agariste and grandson of Cleisthenes of Sicyon

Cleisthenes ( ; ) was the tyrant of Sicyon from , who aided in the First Sacred War against Kirrha that destroyed that city in 595 BC. He was also said to have organized a successful war against Argos because of his anti- Dorian feelings. After ...

. Unlike his grandfather who was a tyrant, he adopted politically democratic concepts. When Pisistratus took power in Athens as a tyrant, he exiled his political opponents and the Alcmaeonidae. After Pisistratus' death in 527 BC, Cleisthenes returned to Athens and became the eponymous archon

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

. A few years later, Pisistratus' successors, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

and Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; ; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, and lectured on poetry, grammar, his ...

, again exiled Cleisthenes. In 514 BC, Harmodius and Aristogeiton

Harmodius (Ancient Greek, Greek: Ἁρμόδιος, ''Harmódios'') and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτων, ''Aristogeíton''; both died 514 BC) were two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides (τυραννόκτον ...

assassinated Hipparchus, causing Hippias to further harden his attitude towards the people of Athens. This led Cleisthenes to ask the Oracle of Delphi

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophecy, prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by Deity, deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divina ...

to persuade the Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

ns to help him free Athens from tyranny. Cleisthenes' plea for assistance was accepted by the Oracle as his family had previously helped rebuild the sanctuary when it was destroyed by fire.

Rise to power

With help from the Spartans and theAlcmaeonidae

The Alcmaeonidae (; , ; Attic: , ) or Alcmaeonids () were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narrati ...

(Cleisthenes' ''genos'', "clan"), he was responsible for overthrowing Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; ; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, and lectured on poetry, grammar, his ...

, the tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

son of Pisistratus

Pisistratus (also spelled Peisistratus or Peisistratos; ; – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular p ...

. After the collapse of Hippias' tyranny, Isagoras

Isagoras (), son of Tisander, was an Athenian aristocrat in the late 6th century BC.

He had remained in Athens during the tyranny of Hippias, but after Hippias was overthrown, he became involved in a struggle for power with Cleisthenes, a fello ...

and Cleisthenes were rivals for power, but Isagoras won the upper hand by appealing to the Spartan king Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I (; Greek Κλεομένης; died c. 490 BC) was Agiad King of Sparta from c. 524 to c. 490 BC. One of the most important Spartan kings, Cleomenes was instrumental in organising the Greek resistance against the Persian Empire of Dar ...

to help him expel Cleisthenes. He did so on the pretext of the Alcmaeonid curse. Consequently, Cleisthenes left Athens as an exile, and Isagoras was unrivalled in power within the city. Isagoras set about dispossessing hundreds of Athenians of their homes and exiling them on the pretext that they too were cursed. He also attempted to dissolve the Boule (βουλή), a council of Athenian citizens appointed to run the daily affairs of the city. However, the council resisted, and the Athenian people declared their support of the council. Isagoras and his partisans were forced to flee to the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

, remaining besieged there for two days. On the third day they fled the city and were banished. Cleisthenes was subsequently recalled, along with hundreds of exiles, and he assumed leadership of Athens. Promptly after his instatement as leader, he commissioned a bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

memorial

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects such as home ...

from the sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

Antenor

__NOTOC__

Antenor (, ''Antḗnōr''; BC) was an Athenian sculptor. He is recorded as the creator of the joint statues of the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton funded by the Athenians on the expulsion of Hippias. These statues were ...

in honour of the lovers and tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

s Harmodius and Aristogeiton

Harmodius (Ancient Greek, Greek: Ἁρμόδιος, ''Harmódios'') and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτων, ''Aristogeíton''; both died 514 BC) were two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides (τυραννόκτον ...

, whom Hippias had executed.

Reformations and governance of Athens

Political reorganization

After this victory, Cleisthenes began to reform the government of Athens. In order to forestall strife between the traditional clans, which had led to thetyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

in the first place, he changed the political organization from the four traditional tribes, which were based on family relations, and which formed the basis of the upper-class Athenian political power network, into ten tribes according to their area of residence (their ''deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or (, plural: ''demoi'', δήμοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside existed in the 6th century BC and earlier, bu ...

''), which would form the basis of a new democratic power structure. It is thought that there may have been 139 demes (though this is still a matter of debate), each organized into three groups called ''trittyes

The ''trittyes'' (; ''trittúes''), singular ''trittys'' (; τριττύς ''trittús'') were part of the organizational structure that divided the population in ancient Attica, and is commonly thought to have been established by the reforms of ...

'' ("thirds"), with ten ''demes'' divided among three regions in each trittyes (a city region, ''asty

Asty (; ) was the physical space of a city or town in Ancient Greece, especially as opposed to the political concept of a ''polis'', which encompassed the entire territory and citizen body of a city-state.

In Classical Athens, the ''asty'' was ...

''; a coastal region, '' paralia''; and an inland region, ''mesogeia

The Mesogeia or Mesogaia (, "Midlands") is a geographical region of Attica in Greece.

History

The term designates since antiquity the inland portion of the Attic peninsula. The term acquired a technical meaning with the reforms of Cleisthenes in ...

'').Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 21 D.M Lewis argues that Cleisthenes established the ''deme'' system in order to balance the central unifying force that a tyranny has with the democratic concept of having the people (instead of a single person) at the peak of political power. Another by-product of the ''deme'' system was that it split up and weakened his political adversaries. Cleisthenes also abolished patronymics in favour of ''demonymics'' (a name given according to the ''deme'' to which one belongs), thus increasing Athenians' sense of belonging to a ''deme''. This and the other aforementioned reforms had an additional effect in that they worked to include (wealthy, male) foreign citizens in Athenian society.

He also established sortition

In governance, sortition is the selection of public officer, officials or jurors at random, i.e. by Lottery (probability), lottery, in order to obtain a representative sample.

In ancient Athenian democracy, sortition was the traditional and pr ...

– the random selection of citizens to fill government positions rather than kinship or heredity. It is also speculated that, in another move to lower the barriers of kinship and heredity when it comes to participation in Athenian society, Cleisthenes made it so foreign residents of Athens were eligible to become legally privileged. In addition, he reorganized the Boule, created with 400 members under Solon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

, so that it had 500 members, 50 from each tribe. He also introduced the bouleutic oath, "To advise according to the laws what was best for the people". The court system ( Dikasteria – law courts) was reorganized and had from 201–5001 jurors selected each day, up to 500 from each tribe. It was the role of the Boule to propose laws to the assembly of voters, who convened in Athens around forty times a year for this purpose. The bills proposed could be rejected, passed, or returned for amendments by the assembly.

Introduction of ostracism

Cleisthenes also may have introducedostracism

Ostracism (, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often us ...

(first used in 487 BC), whereby a vote by at least 6,000 citizens would exile a citizen for ten years. The initial and intended purpose was to vote for a citizen deemed to be a threat to the democracy, most likely anyone who seemed to have ambitions to set himself up as tyrant. However, soon after, any citizen judged to have too much power in the city tended to be targeted for exile (e.g., Xanthippus

Xanthippus (; , ; 520 – 475 BC) was a wealthy Ancient Athens, Athenian politician and general during the Greco-Persian Wars. He was the son of Ariphron and father of Pericles, both prominent Athenian statesmen. A marriage to Agariste, niece ...

in 485–84 BC). Under this system, the exiled man's property was maintained, but he was not physically in the city where he could possibly create a new tyranny. One later ancient author records that Cleisthenes himself was the first person to be ostracized.

Cleisthenes called these reforms ''isonomia

''Isonomia'' (ἰσονομία "equality of political rights,"Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English LexiconThe Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes", Mogens Herman Hansen, , p. 81-84 from the Greek ἴσος ''isos'' ...

'' ("equality vis à vis law", ''iso-'' meaning equality; ''nomos'' meaning law), instead of '' demokratia''. Cleisthenes' life after his reforms is unknown as no ancient texts mention him thereafter.

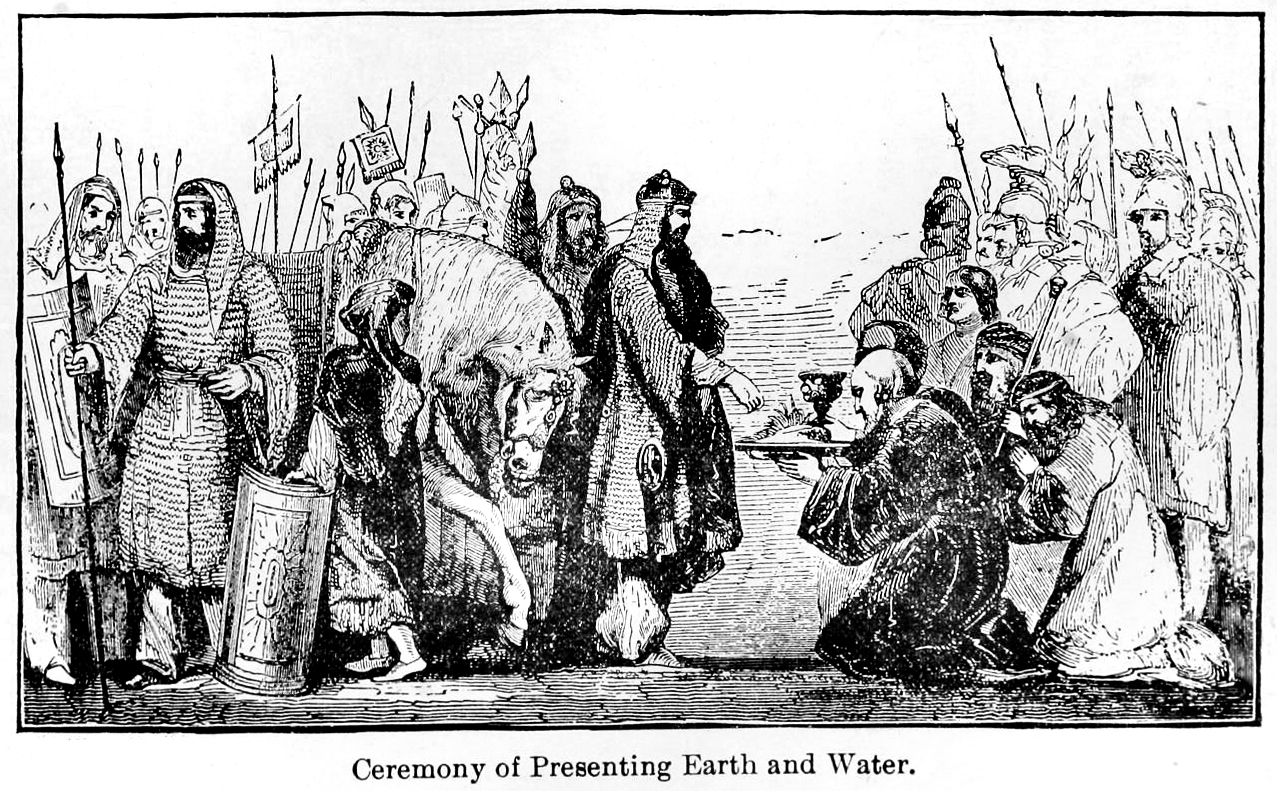

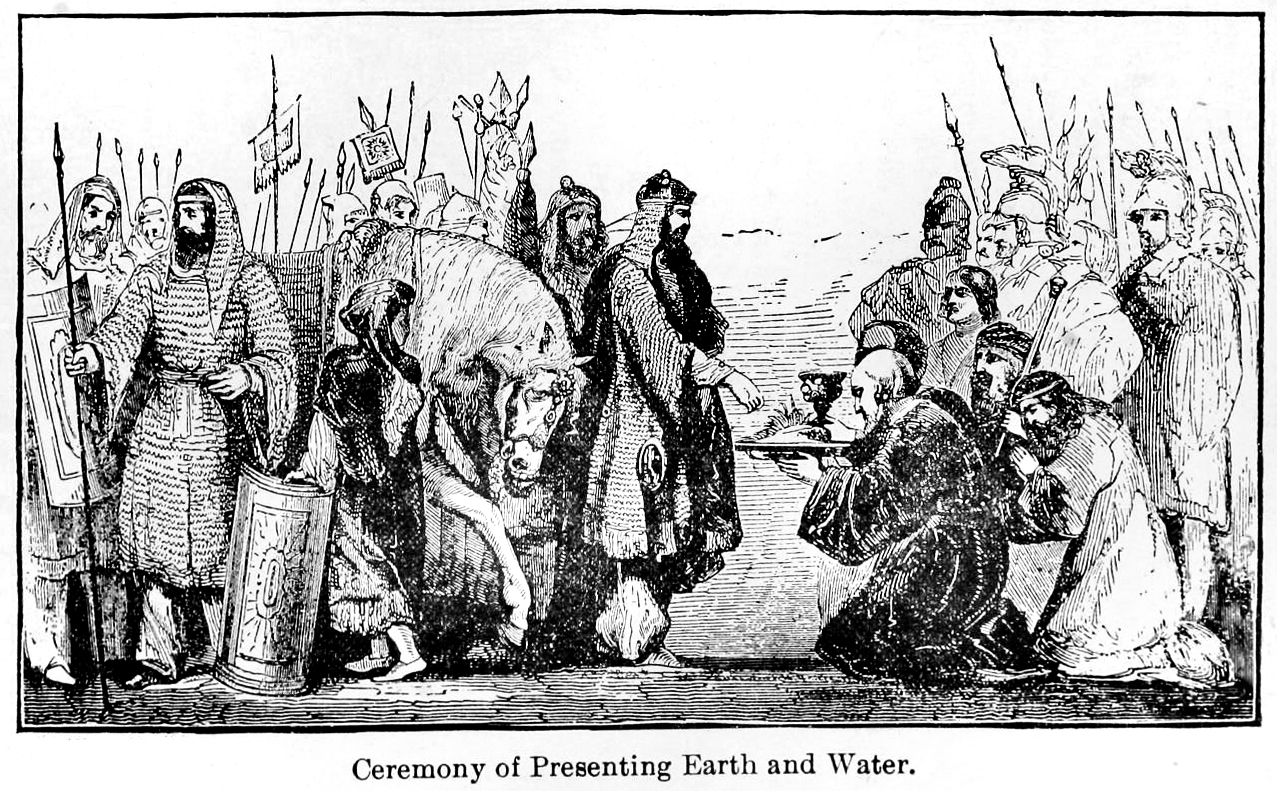

Attempt to obtain Persian support

In 507 BC, during the time Cleisthenes was leading Athenian politics, and probably at his instigation, democratic

In 507 BC, during the time Cleisthenes was leading Athenian politics, and probably at his instigation, democratic Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

sent an embassy to Artaphernes

Artaphernes (Greek language, Greek: Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian language, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median language, Median ''Rtafarnah''), was influential circa 513–492 BC and was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I. ...

, brother of Darius I

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

, and Achaemenid Satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

, of Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

in the capital of Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

, looking for Persian assistance in order to resist the threats from Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

. Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

reports that Artaphernes had no previous knowledge of the Athenians, and his initial reaction was "Who are these people?" Artaphernes asked the Athenians for "Water and Earth", a symbol of submission, if they wanted help from the Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the large ...

king. The Athenian ambassadors apparently accepted to comply, and to give "Earth and Water

"Earth and water" (; ) is a phrase that represents the demand by the Achaemenid Empire for formal tribute from surrendered cities and nations. It appears in the writings of the Greek historian and geographer Herodotus, particularly with regard t ...

". Artaphernes also advised the Athenians that they should receive back the Athenian tyrant Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; ; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, and lectured on poetry, grammar, his ...

. The Persians threatened to attack Athens if they did not accept Hippias. Nevertheless, the Athenians preferred to remain democratic despite the danger from the Achaemenid Empire, and the ambassadors were disavowed and censured upon their return to Athens.

There is a possibility that the Achaemenid ruler now saw the Athenians as subjects who had solemnly promised submission through the gift of "Earth and Water", and that subsequent actions by the Athenians, such as their intervention in the Ionian revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris (Asia Minor), Doris, Ancient history of Cyprus, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Achaemenid Empire, Persian rule, lasting from 499 ...

, were perceived as a breach of oath and a rebellion against the central authority of the Achaemenid ruler.

Citations

References

Primary sources

* . See original text iPerseus Project

*

Secondary sources

* * * * David Ames Curtis: Translator's Foreword to Pierre Vidal-Maquet and Pierre Lévêque's ''Cleisthenes the Athenian: An Essay on the Representation of Space and Time in Greek Thought from the End of the Sixth Century to the Death of Plato'' (1993–1994) http://kaloskaisophos.org/rt/rtdac/rtdactf/rtdactfcleisthenes.htmlFurther reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

*BBC – History – The Democratic Experiment

* {{Authority control 6th-century BC Athenians Ancient legislators Alcmaeonidae Athenian democracy Eponymous archons 500s BC deaths 570s BC births Year of birth uncertain