Chromosome 15q Partial Deletion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A chromosome is a package of

A chromosome is a package of

Each eukaryotic chromosome consists of a long linear DNA molecule associated with

Each eukaryotic chromosome consists of a long linear DNA molecule associated with  In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structure, where it is wrapped around

In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structure, where it is wrapped around

During

During

In the early stages of

In the early stages of

In general, the

In general, the

Chromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content of a cell. They can cause genetic conditions in humans, such as Down syndrome, although most aberrations have little to no effect. Some chromosome abnormalities do not cause disease in carriers, such as

Chromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content of a cell. They can cause genetic conditions in humans, such as Down syndrome, although most aberrations have little to no effect. Some chromosome abnormalities do not cause disease in carriers, such as

Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes that are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid.

Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes that are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid.

An Introduction to DNA and Chromosomes

from HOPES: Huntington's Outreach Project for Education at Stanford

Chromosome Abnormalities at AtlasGeneticsOncology

On-line exhibition on chromosomes and genome (SIB)

What Can Our Chromosomes Tell Us?

from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

Try making a karyotype yourself

from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

Chromosome News from Genome News Network

European network for Rare Chromosome Disorders on the Internet

Ensembl.org

Genographic Project

Home reference on Chromosomes

from the U.S. National Library of Medicine

Visualisation of human chromosomes

and comparison to other species

Unique – The Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group

Support for people with rare chromosome disorders {{Authority control Nuclear substructures Cytogenetics

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

containing part or all of the genetic material

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic aci ...

of an organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone, histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a bobbin, spool. The nucleosome ...

-forming packaging protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s; in eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

cells, the most important of these proteins are the histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

s. Aided by chaperone proteins, the histones bind to and condense

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor ...

the DNA molecule to maintain its integrity. These eukaryotic chromosomes display a complex three-dimensional structure that has a significant role in transcriptional regulation

In molecular biology and genetics, transcriptional regulation is the means by which a cell regulates the conversion of DNA to RNA ( transcription), thereby orchestrating gene activity. A single gene can be regulated in a range of ways, from al ...

.

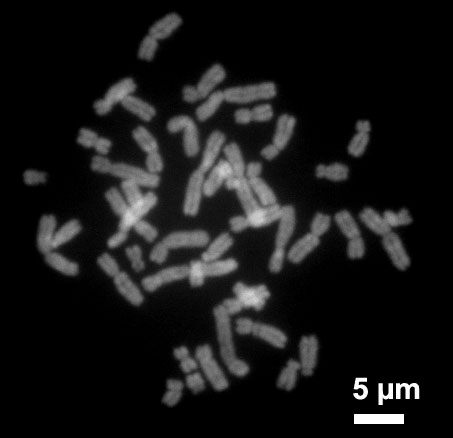

Normally, chromosomes are visible under a light microscope

The optical microscope, also referred to as a light microscope, is a type of microscope that commonly uses visible spectrum, visible light and a system of lens (optics), lenses to generate magnified images of small objects. Optical microscopes ...

only during the metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

of cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

, where all chromosomes are aligned in the center of the cell in their condensed form. Before this stage occurs, each chromosome is duplicated (S phase

S phase (Synthesis phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during S ...

), and the two copies are joined by a centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

—resulting in either an X-shaped structure if the centromere is located equatorially, or a two-armed structure if the centromere is located distally; the joined copies are called 'sister chromatids

A sister chromatid refers to the identical copies ( chromatids) formed by the DNA replication of a chromosome, with both copies joined together by a common centromere. In other words, a sister chromatid may also be said to be 'one-half' of the du ...

'. During metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

, the duplicated structure (called a 'metaphase chromosome') is highly condensed and thus easiest to distinguish and study. In animal cells, chromosomes reach their highest compaction level in anaphase

Anaphase () is the stage of mitosis after the process of metaphase, when replicated chromosomes are split and the newly-copied chromosomes (daughter chromatids) are moved to opposite poles of the cell. Chromosomes also reach their overall maxim ...

during chromosome segregation

Chromosome segregation is the process in eukaryotes by which two sister chromatids formed as a consequence of DNA replication, or paired homologous chromosomes, separate from each other and migrate to opposite poles of the nucleus. This segreg ...

.

Chromosomal recombination during meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

and subsequent sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

plays a crucial role in genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

. If these structures are manipulated incorrectly, through processes known as chromosomal instability

Chromosomal instability (CIN) is a type of genomic instability in which chromosomes are unstable, such that either whole chromosomes or parts of chromosomes are duplicated or deleted. More specifically, CIN refers to the increase in rate of addi ...

and translocation, the cell may undergo mitotic catastrophe

Mitotic catastrophe has been defined as either a cellular mechanism to prevent potentially cancerous cells from proliferating or as a mode of cellular death that occurs following improper cell cycle progression or entrance. Mitotic catastrophe can ...

. This will usually cause the cell to initiate apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, leading to its own death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

, but the process is occasionally hampered by cell mutations that result in the progression of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

.

The term 'chromosome' is sometimes used in a wider sense to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

in cells, which may or may not be visible under light microscopy. In a narrower sense, 'chromosome' can be used to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin during cell division, which are visible under light microscopy due to high condensation.

Etymology

The word ''chromosome'' () comes from theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

words (', "colour") and (', "body"), describing the strong stain

A stain is a discoloration that can be clearly distinguished from the surface, material, or medium it is found upon. They are caused by the chemical or physical interaction of two dissimilar materials. Accidental staining may make materials app ...

ing produced by particular dye

Juan de Guillebon, better known by his stage name DyE, is a French musician. He is known for the music video of the single "Fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction that involves supernatural or Magic (supernatural), magical ele ...

s. The term was coined by the German anatomist Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer, referring to the term 'chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

', which was introduced by Walther Flemming

Walther Flemming (21 April 1843 – 4 August 1905) was a German biologist and a founder of cytogenetics.

He was born in Sachsenberg (now part of Schwerin) as the fifth child and only son of the psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Flemming (1799–1880 ...

.

Some of the early karyological terms have become outdated. For example, 'chromatin' (Flemming 1880) and 'chromosom' (Waldeyer 1888) both ascribe color to a non-colored state.

History of discovery

Otto Bütschli

Johann Adam Otto Bütschli (3 May 1848 – 2 February 1920) was a German zoologist and professor at the University of Heidelberg. He specialized in invertebrates and insect development. Many of the groups of protists were first recognized by him.

...

was the first scientist to recognize the structures now known as chromosomes.

In a series of experiments beginning in the mid-1880s, Theodor Boveri

Theodor Heinrich Boveri (12 October 1862 – 15 October 1915) was a German zoologist, comparative anatomist and co-founder of modern cytology. He was notable for the first hypothesis regarding cellular processes that cause cancer, and for descr ...

gave definitive contributions to elucidating that chromosomes are the vectors of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

, with two notions that became known as 'chromosome continuity' and 'chromosome individuality'.

Wilhelm Roux

Wilhelm Roux (9 June 1850 – 15 September 1924) was a German zoologist and pioneer of experimental embryology.

Early life

Roux was born and educated in Jena, German Confederation where he attended university and studied under Ernst Haeckel. He a ...

suggested that every chromosome carries a different genetic configuration, and Boveri was able to test and confirm this hypothesis. Aided by the rediscovery at the start of the 1900s of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

's earlier experimental work, Boveri identified the connection between the rules of inheritance and the behaviour of the chromosomes. Two generations of American cytologist

Cell biology (also cellular biology or cytology) is a branch of biology that studies the structure, function, and behavior of cells. All living organisms are made of cells. A cell is the basic unit of life that is responsible for the living an ...

s were influenced by Boveri: Edmund Beecher Wilson

Edmund Beecher Wilson (October 19, 1856 – March 3, 1939) was a pioneering American zoologist and geneticist. He wrote one of the most influential textbooks in modern biology, ''The Cell''. He discovered the chromosomal XY sex-determination s ...

, Nettie Stevens

Nettie Maria Stevens (July 7, 1861 – May 4, 1912) was an American geneticist who discovered sex chromosomes. In 1905, soon after the rediscovery of Mendel's paper on genetics in 1900, she observed that male mealworms produced two kinds of sp ...

, Walter Sutton

Walter Stanborough Sutton (April 5, 1877 – November 10, 1916) was an American geneticist and biologist whose most significant contribution to present-day biology was his theory that the Mendelian laws of inheritance could be applied to chromo ...

and Theophilus Painter

Theophilus Shickel Painter (August 22, 1889 – October 5, 1969) was an American zoologist best known for his work on the structure and function of chromosomes, especially the sex-determination genes X and Y in humans. He was the first to discove ...

(Wilson, Stevens, and Painter actually worked with him).

In his famous textbook, ''The Cell in Development and Heredity'', Wilson linked together the independent work of Boveri and Sutton (both around 1902) by naming the chromosome theory of inheritance the ' Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory' (sometimes known as the 'Sutton–Boveri chromosome theory'). Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

remarks that the theory was hotly contested by some famous geneticists, including William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscover ...

, Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen (3 February 1857 – 11 November 1927) was a Danish pharmacist, botanist, plant physiologist, and geneticist. He is best known for coining the terms gene, phenotype and genotype, and for his 1903 "pure line" experiments in ...

, Richard Goldschmidt

Richard Benedict Goldschmidt (April 12, 1878 – April 24, 1958) was a German geneticist. He is considered the first to attempt to integrate genetics, development, and evolution. He pioneered understanding of reaction norms, genetic assimilatio ...

and T.H. Morgan, all of a rather dogmatic mindset. Eventually, absolute proof came from chromosome maps in Morgan's own laboratory.

The number of human chromosomes was published by Painter in 1923. By inspection through a microscope, he counted 24 pairs of chromosomes, giving 48 in total. His error was copied by others, and it was not until 1956 that the true number (46) was determined by Indonesian-born cytogeneticist

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis an ...

Joe Hin Tjio

Joe Hin Tjio (; 2 November 1919 – 27 November 2001), was an Indonesian-born American cytogeneticist. He was renowned as the first person to recognize the normal number of human chromosomes on 22 December 1955 at the Institute of Genetics of t ...

.

Prokaryotes

Theprokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s – bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

– typically have a single circular chromosome

A circular chromosome is a chromosome in bacteria, archaea, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, in the form of a molecule of circular DNA, unlike the linear chromosome of most eukaryotes.

Most prokaryote chromosomes contain a circular DNA molecule. ...

. The chromosomes of most bacteria (also called genophore

The nucleoid (meaning '' nucleus-like'') is an irregularly shaped region within the prokaryotic cell that contains all or most of the genetic material. The chromosome of a typical prokaryote is circular, and its length is very large compared to ...

s), can range in size from only 130,000 base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s in the endosymbiotic

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

bacteria '' Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola'' and '' Candidatus Tremblaya princeps'', to more than 14,000,000 base pairs in the soil-dwelling bacterium ''Sorangium cellulosum

''Sorangium cellulosum'' is a soil-dwelling Gram-negative bacterium of the group myxobacteria. It is motile and shows gliding motility. Under stressful conditions this motility, as in other myxobacteria, the cells congregate to form fruiting b ...

''.

Some bacteria have more than one chromosome. For instance, Spirochaete

A spirochaete () or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (also called Spirochaetes ), which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) Gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or ...

s such as ''Borrelia burgdorferi

''Borrelia burgdorferi'' is a bacterial species of the spirochete class in the genus '' Borrelia'', and is one of the causative agents of Lyme disease in humans. Along with a few similar genospecies, some of which also cause Lyme disease, it m ...

'' (causing Lyme disease

Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a tick-borne disease caused by species of ''Borrelia'' bacteria, Disease vector, transmitted by blood-feeding ticks in the genus ''Ixodes''. It is the most common disease spread by ticks in th ...

), contain a single ''linear'' chromosome. ''Vibrio

''Vibrio'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, which have a characteristic curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection or soft-tissue infection called Vibriosis. Infection is commonly associated with eati ...

s'' typically carry two chromosomes of very different size. Genomes of the genus ''Burkholderia

''Burkholderia'' is a genus of Pseudomonadota whose pathogenic members include the ''Burkholderia cepacia'' complex, which attacks humans and plants; ''Burkholderia mallei'', responsible for glanders, a disease that occurs mostly in horses and r ...

'' carry one, two, or three chromosomes.

Structure in sequences

Prokaryotic chromosomes have less sequence-based structure than eukaryotes. Bacteria typically have a one-point (theorigin of replication

The origin of replication (also called the replication origin) is a particular sequence in a genome at which replication is initiated. Propagation of the genetic material between generations requires timely and accurate duplication of DNA by semi ...

) from which replication starts, whereas some archaea contain multiple replication origins. The genes in prokaryotes are often organized in operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

s and do not usually contain intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gen ...

s, unlike eukaryotes.

DNA packaging

Prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s do not possess nuclei. Instead, their DNA is organized into a structure called the nucleoid

The nucleoid (meaning '' nucleus-like'') is an irregularly shaped region within the prokaryotic cell that contains all or most of the genetic material. The chromosome of a typical prokaryote is circular, and its length is very large compared to ...

. The nucleoid is a distinct structure and occupies a defined region of the bacterial cell. This structure is, however, dynamic and is maintained and remodeled by the actions of a range of histone-like proteins, which associate with the bacterial chromosome. In archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

, the DNA in chromosomes is even more organized, with the DNA packaged within structures similar to eukaryotic nucleosomes.

Certain bacteria also contain plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

s or other extrachromosomal DNA

Extrachromosomal DNA (abbreviated ecDNA) is any DNA that is found off the chromosomes, either inside or outside the nucleus of a cell. Most DNA in an individual genome is found in chromosomes contained in the nucleus. Multiple forms of extrachrom ...

. These are circular structures in the cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

that contain cellular DNA and play a role in horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

. In prokaryotes and viruses, the DNA is often densely packed and organized; in the case of archaea, by homology to eukaryotic histones, and in the case of bacteria, by histone-like proteins.

Bacterial chromosomes tend to be tethered to the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

of the bacteria. In molecular biology application, this allows for its isolation from plasmid DNA by centrifugation of lysed bacteria and pelleting of the membranes (and the attached DNA).

Prokaryotic chromosomes and plasmids are, like eukaryotic DNA, generally supercoiled

DNA supercoiling refers to the amount of twist in a particular DNA strand, which determines the amount of strain on it. A given strand may be "positively supercoiled" or "negatively supercoiled" (more or less tightly wound). The amount of a st ...

. The DNA must first be released into its relaxed state for access for transcription, regulation, and replication.

Eukaryotes

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, forming a compact complex of proteins and DNA called ''chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

.'' Chromatin contains the vast majority of the DNA in an organism, but a small amount inherited maternally can be found in the mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

. It is present in most cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

, with a few exceptions, for example, red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s.

Histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

s are responsible for the first and most basic unit of chromosome organization, the nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone, histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a bobbin, spool. The nucleosome ...

.

Eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s (cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

with nuclei such as those found in plants, fungi, and animals) possess multiple large linear chromosomes contained in the cell's nucleus. Each chromosome has one centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

, with one or two arms projecting from the centromere, although, under most circumstances, these arms are not visible as such. In addition, most eukaryotes have a small circular mitochondrial genome

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the DNA contained in ...

, and some eukaryotes may have additional small circular or linear cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

ic chromosomes.

In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structure, where it is wrapped around

In the nuclear chromosomes of eukaryotes, the uncondensed DNA exists in a semi-ordered structure, where it is wrapped around histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

s (structural proteins), forming a composite material called chromatin.

Interphase chromatin

The packaging of DNA into nucleosomes causes a 10 nanometer fibre which may further condense up to 30 nm fibres. Most of the euchromatin in interphase nuclei appears to be in the form of 30-nm fibers. Chromatin structure is the more decondensed state, i.e. the 10-nm conformation allows transcription.interphase

Interphase is the active portion of the cell cycle that includes the G1, S, and G2 phases, where the cell grows, replicates its DNA, and prepares for mitosis, respectively. Interphase was formerly called the "resting phase," but the cell i ...

(the period of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

where the cell is not dividing), two types of chromatin can be distinguished:

* Euchromatin

Euchromatin (also called "open chromatin") is a lightly packed form of chromatin (DNA, RNA, and protein) that is enriched in genes, and is often (but not always) under active transcription. Euchromatin stands in contrast to heterochromatin, which ...

, which consists of DNA that is active, e.g., being expressed as protein.

* Heterochromatin

Heterochromatin is a tightly packed form of DNA or '' condensed DNA'', which comes in multiple varieties. These varieties lie on a continuum between the two extremes of constitutive heterochromatin and facultative heterochromatin. Both play a rol ...

, which consists of mostly inactive DNA. It seems to serve structural purposes during the chromosomal stages. Heterochromatin can be further distinguished into two types:

** ''Constitutive heterochromatin'', which is never expressed. It is located around the centromere and usually contains repetitive sequences.

** ''Facultative heterochromatin'', which is sometimes expressed.

Metaphase chromatin and division

mitosis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new Cell nucleus, nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identic ...

or meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

(cell division), the chromatin double helix becomes more and more condensed. They cease to function as accessible genetic material ( transcription stops) and become a compact transportable form. The loops of thirty-nanometer chromatin fibers are thought to fold upon themselves further to form the compact metaphase chromosomes of mitotic cells. The DNA is thus condensed about ten-thousand-fold.

The chromosome scaffold

In biology, the chromosome scaffold is the backbone that supports the structure of the chromosomes. It is composed of a group of Non-histone protein, non-histone proteins that are essential in the structure and maintenance of eukaryotic chromosome ...

, which is made of proteins such as condensin

Condensins are large protein complexes that play a central role in chromosome condensation and segregation during mitosis and meiosis (Figure 1). Their subunits were originally identified as major components of mitotic chromosomes assembled in ' ...

, TOP2A

DNA topoisomerase IIα is a human enzyme encoded by the ''TOP2A'' gene.

Topoisomerase IIα relieves topological DNA stress during transcription, condenses chromosomes, and separates chromatids. It catalyzes the transient breaking and rejoining o ...

and KIF4, plays an important role in holding the chromatin into compact chromosomes. Loops of thirty-nanometer structure further condense with scaffold into higher order structures.

This highly compact form makes the individual chromosomes visible, and they form the classic four-arm structure, a pair of sister chromatid

A chromatid (Greek ''khrōmat-'' 'color' + ''-id'') is one half of a duplicated chromosome. Before replication, one chromosome is composed of one DNA molecule. In replication, the DNA molecule is copied, and the two molecules are known as chrom ...

s attached to each other at the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

. The shorter arms are called '' p arms'' (from the French ''petit'', small) and the longer arms are called '' q arms'' (''q'' follows ''p'' in the Latin alphabet; q-g "grande"; alternatively it is sometimes said q is short for ''queue'' meaning tail in French). This is the only natural context in which individual chromosomes are visible with an optical microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory equipment, laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic ...

.

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes are best described by a linearly organized longitudinally compressed array of consecutive chromatin loops.

During mitosis, microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nanometer, nm and have an inner diameter bet ...

s grow from centrosomes located at opposite ends of the cell and also attach to the centromere at specialized structures called kinetochore

A kinetochore (, ) is a flared oblique-shaped protein structure associated with duplicated chromatids in eukaryotic cells where the spindle fibers, which can be thought of as the ropes pulling chromosomes apart, attach during cell division to ...

s, one of which is present on each sister chromatid

A chromatid (Greek ''khrōmat-'' 'color' + ''-id'') is one half of a duplicated chromosome. Before replication, one chromosome is composed of one DNA molecule. In replication, the DNA molecule is copied, and the two molecules are known as chrom ...

. A special DNA base sequence in the region of the kinetochores provides, along with special proteins, longer-lasting attachment in this region. The microtubules then pull the chromatids apart toward the centrosomes, so that each daughter cell inherits one set of chromatids. Once the cells have divided, the chromatids are uncoiled and DNA can again be transcribed. In spite of their appearance, chromosomes are structurally highly condensed, which enables these giant DNA structures to be contained within a cell nucleus.

Human chromosomes

Chromosomes in humans can be divided into two types:autosome

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosomes ...

s (body chromosome(s)) and allosome (sex chromosome

Sex chromosomes (also referred to as allosomes, heterotypical chromosome, gonosomes, heterochromosomes, or idiochromosomes) are chromosomes that

carry the genes that determine the sex of an individual. The human sex chromosomes are a typical pair ...

(s)). Certain genetic traits are linked to a person's sex and are passed on through the sex chromosomes. The autosomes contain the rest of the genetic hereditary information. All act in the same way during cell division. Human cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes (22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes), giving a total of 46 per cell. In addition to these, human cells have many hundreds of copies of the mitochondrial genome

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the DNA contained in ...

. Sequencing

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which succ ...

of the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

has provided a great deal of information about each of the chromosomes. Below is a table compiling statistics for the chromosomes, based on the Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute, previously known as The Sanger Centre and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, is a non-profit organisation, non-profit British genomics and genetics research institute, primarily funded by the Wellcome Trust.

It is l ...

's human genome information in the Vertebrate Genome Annotation (VEGA) database. Number of genes is an estimate, as it is in part based on gene prediction

In computational biology, gene prediction or gene finding refers to the process of identifying the regions of genomic DNA that encode genes. This includes protein-coding genes as well as RNA genes, but may also include prediction of other functio ...

s. Total chromosome length is an estimate as well, based on the estimated size of unsequenced heterochromatin

Heterochromatin is a tightly packed form of DNA or '' condensed DNA'', which comes in multiple varieties. These varieties lie on a continuum between the two extremes of constitutive heterochromatin and facultative heterochromatin. Both play a rol ...

regions.

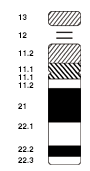

Based on the micrographic characteristics of size, position of the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

and sometimes the presence of a chromosomal satellite, the human chromosomes are classified into the following groups:

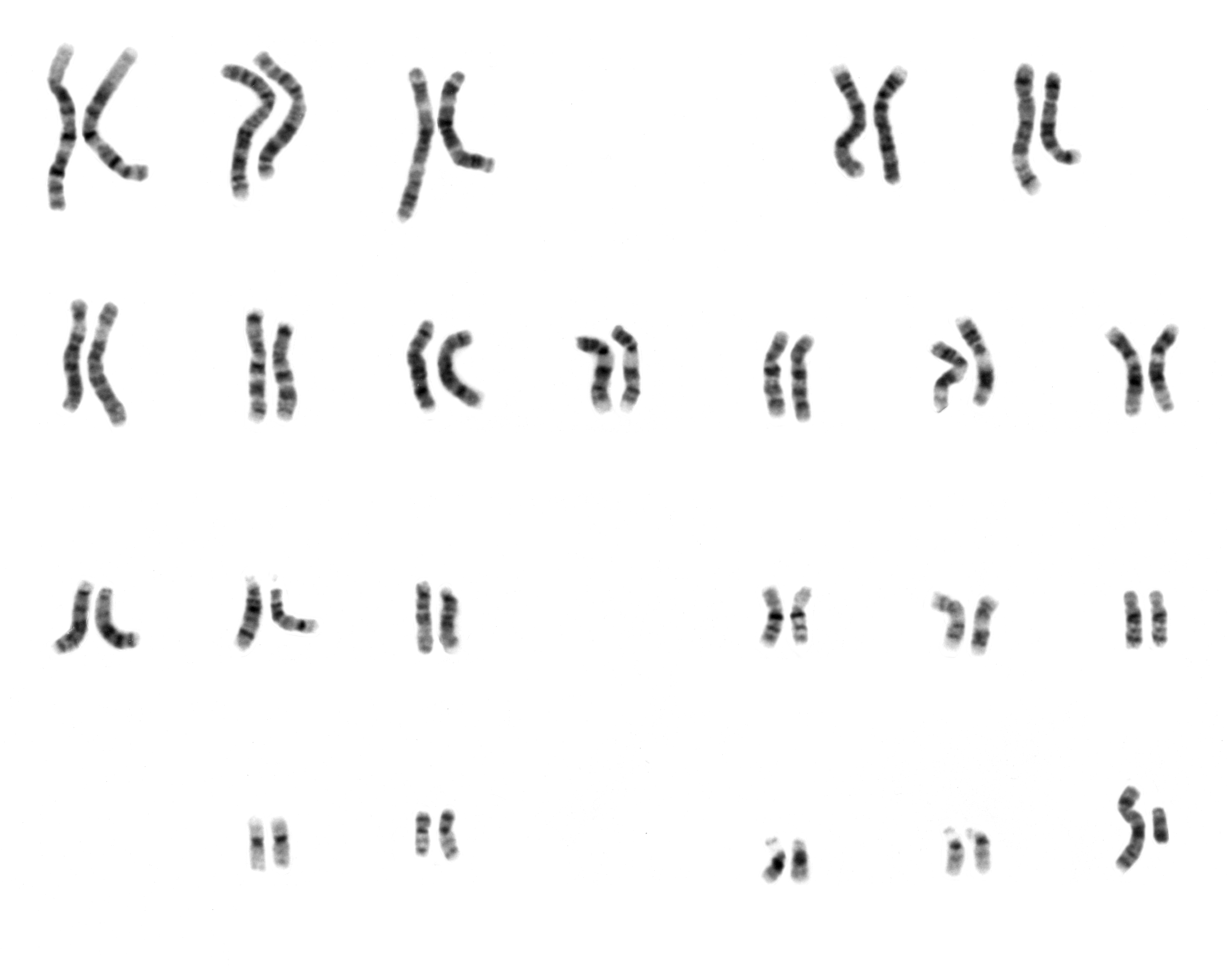

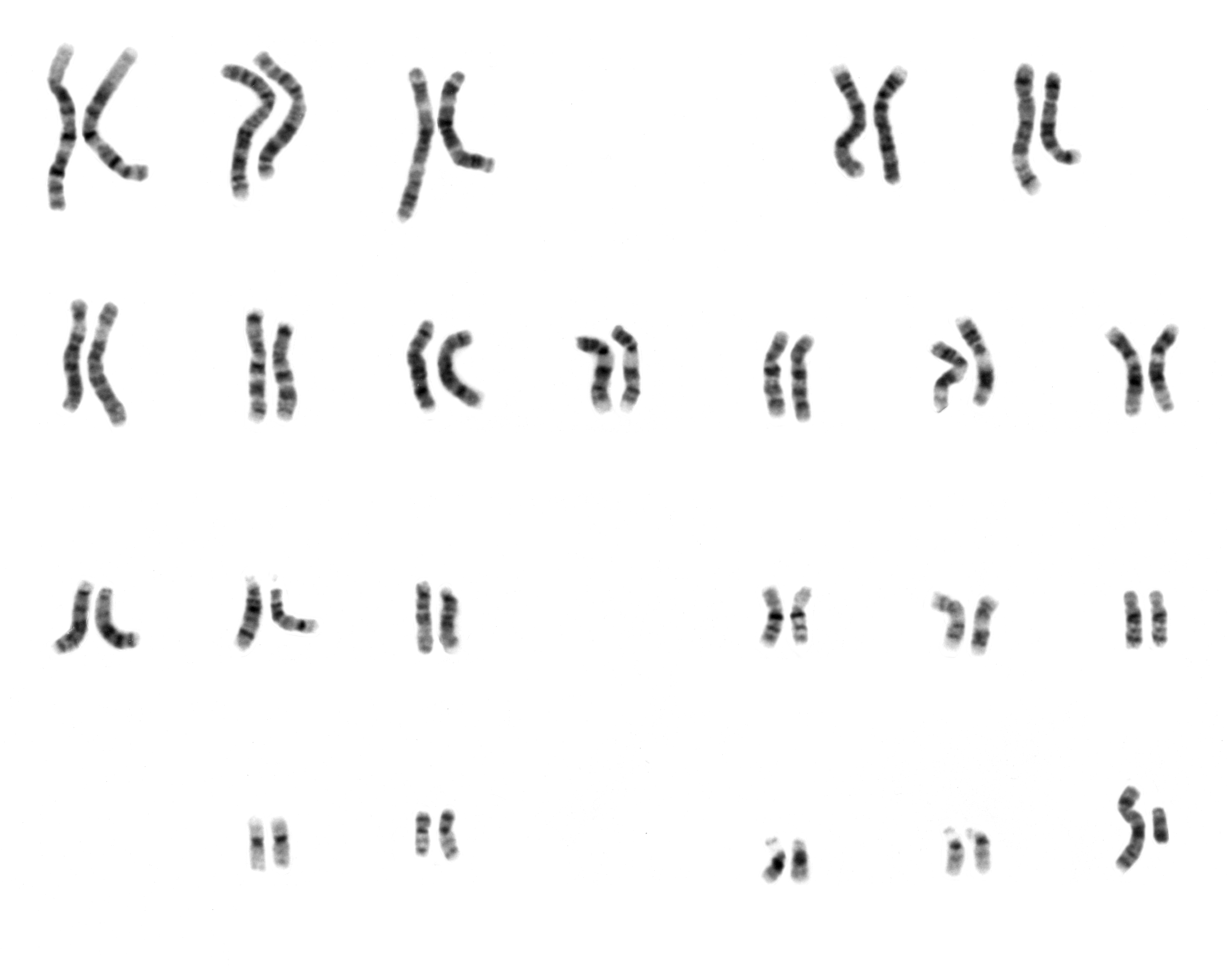

Karyotype

In general, the

In general, the karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by de ...

is the characteristic chromosome complement of a eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis an ...

.

Although the replication and transcription of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are often highly variable. There may be variation between species in chromosome number and in detailed organization.

In some cases, there is significant variation within species. Often there is:

:1. variation between the two sexes

:2. variation between the germline

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that develop into germ cells. In other words, they are the cells that form gametes ( eggs and sperm), which can come together to form a zygote. They dif ...

and soma

Soma may refer to:

Businesses and brands

* SOMA (architects), a New York–based firm of architects

* Soma (company), a company that designs eco-friendly water filtration systems

* SOMA Fabrications, a builder of bicycle frames and other bicycle ...

(between gamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s and the rest of the body)

:3. variation between members of a population, due to balanced genetic polymorphism

:4. geographical variation between races

:5. mosaics

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

or otherwise abnormal individuals.

Also, variation in karyotype may occur during development from the fertilized egg.

The technique of determining the karyotype is usually called ''karyotyping''. Cells can be locked part-way through division (in metaphase) in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

(in a reaction vial) with colchicine

Colchicine is a medication used to prevent and treat gout, to treat familial Mediterranean fever and Behçet's disease, and to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction. The American College of Rheumatology recommends colchicine, nonstero ...

. These cells are then stained, photographed, and arranged into a ''karyogram'', with the set of chromosomes arranged, autosomes in order of length, and sex chromosomes (here X/Y) at the end.

Like many sexually reproducing species, humans have special gonosomes (sex chromosomes, in contrast to autosome

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosomes ...

s). These are XX in females and XY in males.

History and analysis techniques

Investigation into the human karyotype took many years to settle the most basic question: ''How many chromosomes does a normaldiploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

human cell contain?'' In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia

A spermatogonium (plural: ''spermatogonia'') is an undifferentiated male germ cell. Spermatogonia undergo spermatogenesis to form mature spermatozoa in the seminiferous tubules of the testicles.

There are three subtypes of spermatogonia in human ...

and 48 in oogonia

An oogonium (: oogonia) is a small diploid cell which, upon maturation, forms a primordial follicle in a female fetus or the female (haploid or diploid) gametangium of certain thallophytes.

In the mammalian fetus

Oogonia are formed in lar ...

, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism. In 1922, Painter

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

was not certain whether the diploid number of man is 46 or 48, at first favouring 46. He revised his opinion later from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on humans having an XX/XY system.

New techniques were needed to definitively solve the problem:

# Using cells in culture

# Arresting mitosis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new Cell nucleus, nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identic ...

in metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

by a solution of colchicine

Colchicine is a medication used to prevent and treat gout, to treat familial Mediterranean fever and Behçet's disease, and to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction. The American College of Rheumatology recommends colchicine, nonstero ...

# Pretreating cells in a hypotonic solution

In chemical biology, tonicity is a measure of the effective osmotic pressure gradient; the water potential of two solutions separated by a partially-permeable cell membrane. Tonicity depends on the relative concentration of selective membrane ...

, which swells them and spreads the chromosomes

# Squashing the preparation on the slide forcing the chromosomes into a single plane

# Cutting up a photomicrograph and arranging the result into an indisputable karyogram.

It took until 1954 before the human diploid number was confirmed as 46. Considering the techniques of Winiwarter and Painter, their results were quite remarkable. Chimpanzees

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close relative the ...

, the closest living relatives to modern humans, have 48 chromosomes as do the other great apes

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); '' Gorilla'' (the ...

: in humans two chromosomes fused to form chromosome 2

Chromosome 2 is one of the twenty-three pairs of chromosomes in humans. People normally have two copies of this chromosome. Chromosome 2 is the second-largest human chromosome, spanning more than 242 million base pairs and representing almost ei ...

.

Aberrations

Chromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content of a cell. They can cause genetic conditions in humans, such as Down syndrome, although most aberrations have little to no effect. Some chromosome abnormalities do not cause disease in carriers, such as

Chromosomal aberrations are disruptions in the normal chromosomal content of a cell. They can cause genetic conditions in humans, such as Down syndrome, although most aberrations have little to no effect. Some chromosome abnormalities do not cause disease in carriers, such as translocations

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes "balanced" and "unbalanced" translocation, with three main types: "reciprocal", "nonreciprocal" and "Robertsonian" transloc ...

, or chromosomal inversion

An inversion is a chromosome rearrangement in which a segment of a chromosome becomes inverted within its original position. An inversion occurs when a chromosome undergoes a two breaks within the chromosomal arm, and the segment between the two b ...

s, although they may lead to a higher chance of bearing a child with a chromosome disorder. Abnormal numbers of chromosomes or chromosome sets, called aneuploidy

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, for example a human somatic (biology), somatic cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more plo ...

, may be lethal or may give rise to genetic disorders. Genetic counseling

Genetic counseling is the process of investigating individuals and families affected by or at risk of genetic disorders to help them understand and adapt to the medical, psychological and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease. ...

is offered for families that may carry a chromosome rearrangement.

The gain or loss of DNA from chromosomes can lead to a variety of genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosome abnormality. Although polygenic disorders ...

s. Human examples include:

* Cri du chat

Cri du chat syndrome is a rare genetic disorder due to a partial chromosome deletion on chromosome 5. Its name is a French term ("cat-cry" or " call of the cat") referring to the characteristic cat-like cry of affected children. It was first ...

, caused by the deletion of part of the short arm of chromosome 5. "Cri du chat" means "cry of the cat" in French; the condition was so-named because affected babies make high-pitched cries that sound like those of a cat. Affected individuals have wide-set eyes, a small head and jaw, moderate to severe mental health problems, and are very short.

* DiGeorge syndrome

DiGeorge syndrome, also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, is a syndrome caused by a microdeletion on the long arm of chromosome 22. While the symptoms can vary, they often include congenital heart problems, specific facial features, frequent ...

, also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Symptoms are mild learning disabilities in children, with adults having an increased risk of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

. Infections are also common in children because of problems with the immune system's T cell-mediated response due to an absence of hypoplastic thymus.

* Down syndrome, the most common trisomy, usually caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21 (trisomy 21

A trisomy is a type of polysomy in which there are three instances of a particular chromosome, instead of the normal two. A trisomy is a type of aneuploidy (an abnormal number of chromosomes).

Description and causes

Most organisms that repro ...

). Characteristics include decreased muscle tone, stockier build, asymmetrical skull, slanting eyes, and mild to moderate developmental disability.

* Edwards syndrome Edwards may refer to:

People

* Edwards (surname), an English surname

* Edwards family, a prominent family from Chile

* Edwards Barham (1937–2014), American politician

* Edwards Davis (1873–1936), American actor, producer, and playwright

* Edwa ...

, or trisomy-18, the second most common trisomy. Symptoms include motor retardation, developmental disability, and numerous congenital anomalies causing serious health problems. Ninety percent of those affected die in infancy. They have characteristic clenched hands and overlapping fingers.

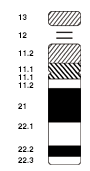

* Isodicentric 15

Isodicentric 15, also called marker chromosome 15 syndrome, idic(15), partial tetrasomy 15q, or inverted duplication 15 (inv dup 15), is a chromosome abnormality in which a child is born with extra genetic material from chromosome 15. People wit ...

, also called idic(15), partial tetrasomy 15q, or inverted duplication 15 (inv dup 15).

* Jacobsen syndrome

Jacobsen syndrome is a rare chromosomal disorder resulting from deletion of genes from chromosome 11 that includes band 11q24.1. It is a congenital disorder. Since the deletion takes place on the q arm of chromosome 11, it is also called 11q ...

, which is very rare. It is also called the 11q terminal deletion disorder. Those affected have normal intelligence or mild developmental disability, with poor expressive language skills. Most have a bleeding disorder called Paris-Trousseau syndrome.

* Klinefelter syndrome

Klinefelter syndrome (KS), also known as 47,XXY, is a chromosome anomaly where a male has an extra X chromosome. These complications commonly include infertility and small, poorly functioning testicles (if present). These symptoms are often n ...

(XXY). Men with Klinefelter syndrome are usually sterile, and tend to be taller than their peers, with longer arms and legs. Boys with the syndrome are often shy and quiet, and have a higher incidence of speech delay

Speech delay, also known as alalia, refers to a delay in the development or use of the mechanisms that produce speech. Speech – as distinct from language – is the actual process of making sounds, using such organs and structures as the lungs, ...

and dyslexia

Dyslexia (), previously known as word blindness, is a learning disability that affects either reading or writing. Different people are affected to different degrees. Problems may include difficulties in spelling words, reading quickly, wri ...

. Without testosterone treatment, some may develop gynecomastia

Gynecomastia (also spelled gynaecomastia) is the non-cancerous enlargement of one or both breasts in men due to the growth of breast tissue as a result of a hormone imbalance between estrogens and androgens. Updated by Brent Wisse (10 Novemb ...

during puberty.

* Patau Syndrome

Patau syndrome is a syndrome caused by a chromosomal abnormality, in which some or all of the cells of the body contain extra genetic material from chromosome 13. The extra genetic material disrupts normal development, causing multiple and co ...

, also called D-Syndrome or trisomy-13. Symptoms are somewhat similar to those of trisomy-18, without the characteristic folded hand.

* Small supernumerary marker chromosome

A small supernumerary marker chromosome (sSMC) is an abnormal extra chromosome. It contains copies of parts of one or more normal chromosomes and like normal chromosomes is located in the cell's nucleus, is replicated and distributed into each d ...

. This means there is an extra, abnormal chromosome. Features depend on the origin of the extra genetic material. Cat-eye syndrome

Cat-eye syndrome (CES) or Schmid–Fraccaro syndrome is a rare condition caused by an abnormal extra chromosome, i.e. a small supernumerary marker chromosome. This chromosome consists of the entire short arm and a small section of the long arm o ...

and isodicentric chromosome 15 syndrome

Isodicentric 15, also called marker chromosome 15 syndrome, idic(15), partial tetrasomy 15q, or inverted duplication 15 (inv dup 15), is a chromosome abnormality in which a child is born with extra genetic material from chromosome 15. People with ...

(or Idic15) are both caused by a supernumerary marker chromosome, as is Pallister–Killian syndrome

The Pallister–Killian syndrome (PKS), also termed tetrasomy 12p mosaicism or the Pallister mosaic aneuploidy syndrome, is an extremely rare and severe genetic disorder. PKS is due to the presence of an extra and abnormal chromosome termed a sma ...

.

* Triple-X syndrome (XXX). XXX girls tend to be tall and thin, and have a higher incidence of dyslexia.

* Turner syndrome

Turner syndrome (TS), commonly known as 45,X, or 45,X0,Also written as 45,XO. is a chromosomal disorder in which cells of females have only one X chromosome instead of two, or are partially missing an X chromosome (sex chromosome monosomy) lea ...

(X instead of XX or XY). In Turner syndrome, female sexual characteristics are present but underdeveloped. Females with Turner syndrome often have a short stature, low hairline, abnormal eye features and bone development, and a "caved-in" appearance to the chest.

* Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome

Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) is a chromosomal deletion syndrome resulting from a partial deletion on the short arm of chromosome 4 el(4)(p16.3) Features include a distinct craniofacial phenotype and intellectual disability.

Signs and sympt ...

, caused by partial deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4. It is characterized by growth retardation, delayed motor skills development, "Greek Helmet" facial features, and mild to profound mental health problems.

* XYY syndrome

XYY syndrome, also known as Jacobs syndrome, is an aneuploid genetic condition in which a male has an extra Y chromosome. There are usually few symptoms. These may include being taller than average and an increased risk of learning disabiliti ...

. XYY boys are usually taller than their siblings. Like XXY boys and XXX girls, they are more likely to have learning difficulties.

Sperm aneuploidy

Exposure of males to certain lifestyle, environmental and/or occupational hazards may increase the risk of aneuploid spermatozoa. In particular, risk of aneuploidy is increased by tobacco smoking, and occupational exposure to benzene,insecticide

Insecticides are pesticides used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. The major use of insecticides is in agriculture, but they are also used in home and garden settings, i ...

s, and perfluorinated compounds. Increased aneuploidy is often associated with increased DNA damage in spermatozoa.

Number in various organisms

In eukaryotes

The number of chromosomes ineukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s is highly variable. It is possible for chromosomes to fuse or break and thus evolve into novel karyotypes. Chromosomes can also be fused artificially. For example, when the 16 chromosomes of yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

were fused into one giant chromosome, it was found that the cells were still viable with only somewhat reduced growth rates.

The tables below give the total number of chromosomes (including sex chromosomes) in a cell nucleus for various eukaryotes. Most are diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

, such as humans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

who have 22 different types of autosome

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosomes ...

s—each present as two homologous pairs—and two sex chromosome

Sex chromosomes (also referred to as allosomes, heterotypical chromosome, gonosomes, heterochromosomes, or idiochromosomes) are chromosomes that

carry the genes that determine the sex of an individual. The human sex chromosomes are a typical pair ...

s, giving 46 chromosomes in total. Some other organisms have more than two copies of their chromosome types, for example bread wheat

Common wheat (''Triticum aestivum''), also known as bread wheat, is a cultivated wheat species. About 95% of wheat produced worldwide is common wheat; it is the most widely grown of all crops and the cereal with the highest monetary yield.

Ta ...

which is ''hexaploid'', having six copies of seven different chromosome types for a total of 42 chromosomes.

Normal members of a particular eukaryotic species all have the same number of nuclear chromosomes. Other eukaryotic chromosomes, i.e., mitochondrial and plasmid-like small chromosomes, are much more variable in number, and there may be thousands of copies per cell.

Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes that are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid.

Asexually reproducing species have one set of chromosomes that are the same in all body cells. However, asexual species can be either haploid or diploid.

Sexually reproducing

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete (haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote that d ...

species have somatic cell

In cellular biology, a somatic cell (), or vegetal cell, is any biological cell forming the body of a multicellular organism other than a gamete, germ cell, gametocyte or undifferentiated stem cell. Somatic cells compose the body of an organism ...

s (body cells) that are diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

n having two sets of chromosomes (23 pairs in humans), one set from the mother and one from the father. Gamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s (reproductive cells) are haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

having one set of chromosomes. Gametes are produced by meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

of a diploid germline

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that develop into germ cells. In other words, they are the cells that form gametes ( eggs and sperm), which can come together to form a zygote. They dif ...

cell, during which the matching chromosomes of father and mother can exchange small parts of themselves (crossover

Crossover may refer to:

Entertainment

Music

Albums

* ''Cross Over'' (album), a 1987 album by Dan Peek, or the title song

* ''Crossover'' (Dirty Rotten Imbeciles album), 1987

* ''Crossover'', an album by Intrigue

* ''Crossover'', an album by ...

) and thus create new chromosomes that are not inherited solely from either parent. When a male and a female gamete merge during fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give ...

, a new diploid organism is formed.

Some animal and plant species are polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning ...

n having more than two sets of homologous chromosome

Homologous chromosomes or homologs are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during meiosis. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci, where they provide points along e ...

s. Important crops such as tobacco or wheat are often polyploid, compared to their ancestral species. Wheat has a haploid number of seven chromosomes, still seen in some cultivar

A cultivar is a kind of Horticulture, cultivated plant that people have selected for desired phenotypic trait, traits and which retains those traits when Plant propagation, propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root a ...

s as well as the wild progenitors. The more common types of pasta and bread wheat are polyploid, having 28 (tetraploid) and 42 (hexaploid) chromosomes, compared to the 14 (diploid) chromosomes in wild wheat.

In prokaryotes

Prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

species generally have one copy of each major chromosome, but most cells can easily survive with multiple copies. For example, '' Buchnera'', a symbiont

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

of aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects in the Taxonomic rank, family Aphididae. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white Eriosomatinae, woolly ...

s, has multiple copies of its chromosome, ranging from 10 to 400 copies per cell. However, in some large bacteria, such as ''Epulopiscium fishelsoni

''Candidatus Epulopiscium'' is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria that have a symbiotic relationship with surgeonfish. These bacteria are known for their unusually large size, many ranging from 0.2 - 0.7 mm (200–700 μm) in length. Until the di ...

'' up to 100,000 copies of the chromosome can be present. Plasmids and plasmid-like small chromosomes are, as in eukaryotes, highly variable in copy number. The number of plasmids in the cell is almost entirely determined by the rate of division of the plasmid – fast division causes high copy number.

See also

* Chromomere *Cohesin

Cohesin is a protein complex that mediates Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion, sister chromatid cohesion, homologous recombination, and Topologically associating domain, DNA looping. Cohesin is formed of SMC3, SMC1A, SMC1, RAD21, SCC1 an ...

* Epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

* Genetic genealogy

Genetic genealogy is the use of genealogical DNA tests, i.e., DNA profiling and DNA testing, in combination with traditional genealogical methods, to infer genetic relationships between individuals. This application of genetics came to be use ...

* Lampbrush chromosome

* Locus (genetics)

In genetics, a locus (: loci) is a specific, fixed position on a chromosome where a particular gene or genetic marker is located. Each chromosome carries many genes, with each gene occupying a different position or locus; in humans, the total numb ...

– explains gene location nomenclature

* Minichromosome

A minichromosome is a small chromatin-like structure resembling a chromosome and consisting of centromeres, telomeres and replication origins but little additional genetic material. They replicate autonomously in the cell during cellular divisio ...

* Neochromosome

* Nondisjunction

Nondisjunction is the failure of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids to separate properly during cell division (mitosis/meiosis). There are three forms of nondisjunction: failure of a pair of homologous chromosomes to separate in meiosis I ...

* Parasitic chromosome

Parasitic chromosomes are "selfish" chromosomes that propagate throughout cell divisions, even if they confer no benefit to the overall organism's survival. Parasitic chromosomes can persist even if slightly detrimental to survival, as is characte ...

* Polytene chromosome

* Secondary chromosome

* Sex-determination system

A sex-determination system is a biological system that determines the development of sexual characteristics in an organism. Most organisms that create their offspring using sexual reproduction have two common sexes, males and females, and in ...

** Maternal influence on sex determination

** Temperature-dependent sex determination

Temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) is a type of environmental sex determination in which the temperatures experienced during embryonic/larval development determine the sex of the offspring. It is observed in reptiles and teleost fish, ...

Notes and references

External links

An Introduction to DNA and Chromosomes

from HOPES: Huntington's Outreach Project for Education at Stanford

Chromosome Abnormalities at AtlasGeneticsOncology

On-line exhibition on chromosomes and genome (SIB)

What Can Our Chromosomes Tell Us?

from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

Try making a karyotype yourself

from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

Chromosome News from Genome News Network

European network for Rare Chromosome Disorders on the Internet

Ensembl.org

Ensembl

Ensembl genome database project is a scientific project at the European Bioinformatics Institute, which provides a centralized resource for geneticists, molecular biologists and other researchers studying the genomes of our own species and other v ...

project, presenting chromosomes, their gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s and syntenic loci graphically via the web

Genographic Project

Home reference on Chromosomes

from the U.S. National Library of Medicine

Visualisation of human chromosomes

and comparison to other species

Unique – The Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group

Support for people with rare chromosome disorders {{Authority control Nuclear substructures Cytogenetics