Chilembwe Uprising on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chilembwe uprising was a rebellion against British colonial rule in

British colonial rule in the region of modern-day

British colonial rule in the region of modern-day

Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland in 1900 and, with the assistance of the African-American National Baptist Convention, he founded his independent church, the

Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland in 1900 and, with the assistance of the African-American National Baptist Convention, he founded his independent church, the

The major action of the Chilembwe uprising involved an attack on the Bruce plantation at Magomero. The plantation spanned about and grew both cotton and tobacco. Around 5,000 locals worked on it as part of their ''thangata'' obligations. The plantation had a reputation locally for the poor treatment of its workers and for the brutality of its managers, who closed local schools, beat their workers and paid them less than had been promised. Their burning of Chilembwe's church in November 1913 created a personal animosity with the rebel leadership. The insurgents launched two roughly concurrent attacks—one group targeted Magomero, the plantation headquarters and home of the main manager William Jervis Livingstone and a few other white staff, while a second assaulted the plantation-owned village of Mwanje, where there were two white households.

The rebels moved into Magomero in the early evening, while Livingstone and his wife were entertaining some dinner guests. The estate official, Duncan MacCormick, was in another house nearby. A third building, occupied by Emily Stanton, Alyce Roach and five children, contained a small cache of weapons and ammunition belonging to the local rifle club. The insurgents quietly broke into the Livingstone's house and injured him during hand-to-hand fighting, prompting him to take refuge in the bedroom, where his wife attempted to treat his wounds. The rebels forced their way into the bedroom, and after capturing his wife, decapitated Livingstone. MacCormick, who had been alerted, was killed by a rebel spear. The attackers took the women and children of the village prisoner but shortly released them unhurt, having reportedly treated them well. It has been suggested that Chilembwe may have hoped to use the women and children as hostages, but this remains unclear. The attack on Magomero, and in particular the killing of Livingstone, had great symbolic significance for Chilembwe's men. The two

The major action of the Chilembwe uprising involved an attack on the Bruce plantation at Magomero. The plantation spanned about and grew both cotton and tobacco. Around 5,000 locals worked on it as part of their ''thangata'' obligations. The plantation had a reputation locally for the poor treatment of its workers and for the brutality of its managers, who closed local schools, beat their workers and paid them less than had been promised. Their burning of Chilembwe's church in November 1913 created a personal animosity with the rebel leadership. The insurgents launched two roughly concurrent attacks—one group targeted Magomero, the plantation headquarters and home of the main manager William Jervis Livingstone and a few other white staff, while a second assaulted the plantation-owned village of Mwanje, where there were two white households.

The rebels moved into Magomero in the early evening, while Livingstone and his wife were entertaining some dinner guests. The estate official, Duncan MacCormick, was in another house nearby. A third building, occupied by Emily Stanton, Alyce Roach and five children, contained a small cache of weapons and ammunition belonging to the local rifle club. The insurgents quietly broke into the Livingstone's house and injured him during hand-to-hand fighting, prompting him to take refuge in the bedroom, where his wife attempted to treat his wounds. The rebels forced their way into the bedroom, and after capturing his wife, decapitated Livingstone. MacCormick, who had been alerted, was killed by a rebel spear. The attackers took the women and children of the village prisoner but shortly released them unhurt, having reportedly treated them well. It has been suggested that Chilembwe may have hoped to use the women and children as hostages, but this remains unclear. The attack on Magomero, and in particular the killing of Livingstone, had great symbolic significance for Chilembwe's men. The two

The rebels cut the Zomba–

The rebels cut the Zomba–

KAR troops launched a tentative attack on Mbombwe on 25 January but the engagement proved inconclusive. Chilembwe's forces held a strong defensive position along the Mbombwe river and could not be pushed back. Two KAR soldiers were killed and three were wounded; Chilembwe's losses have been estimated as about 20.

On 26 January, a group of rebels attacked a

KAR troops launched a tentative attack on Mbombwe on 25 January but the engagement proved inconclusive. Chilembwe's forces held a strong defensive position along the Mbombwe river and could not be pushed back. Two KAR soldiers were killed and three were wounded; Chilembwe's losses have been estimated as about 20.

On 26 January, a group of rebels attacked a

Despite its failure, the Chilembwe uprising has since gained an important place in the modern Malawian cultural memory, with Chilembwe himself gaining "iconic status". The uprising had "local notoriety" in the years immediately after it, and former rebels were kept under police observation. Over the next three decades, local anti-colonial activists idealised Chilembwe and began to see him as a semi-mythical figure. The

Despite its failure, the Chilembwe uprising has since gained an important place in the modern Malawian cultural memory, with Chilembwe himself gaining "iconic status". The uprising had "local notoriety" in the years immediately after it, and former rebels were kept under police observation. Over the next three decades, local anti-colonial activists idealised Chilembwe and began to see him as a semi-mythical figure. The

"John Chilembwe: Brief life of an anticolonial rebel: 1871?–1915"

at ''

Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After ...

(modern-day Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

) which took place in January 1915. It was led by John Chilembwe

John Chilembwe (June 1871 – 3 February 1915) was a Baptist pastor, educator and revolutionary who trained as a minister in the United States, returning to Nyasaland in 1901. He was an early figure in the resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland ...

, an American-educated Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister. Based around his church in the village of Mbombwe in the south-east of the colony, the leaders of the revolt were mainly from an emerging black middle class. They were motivated by grievances against the British colonial system, which included forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

, racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their Race (human categorization), race, ancestry, ethnicity, ethnic or national origin, and/or Human skin color, skin color and Hair, hair texture. Individuals ...

and new demands imposed on the African population following the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

The revolt broke out in the evening of 23 January 1915 when rebels, incited by Chilembwe, attacked the headquarters of the A. L. Bruce Estates at Magomero

Magomero is an estate and a village in Malawi. It is situated south of Zomba.

History

Although Alexander Low Bruce never visited Nyasaland, he obtained title to some 170,000 acres of land there through his association with the African Lakes Comp ...

and killed three white settlers. A largely unsuccessful attack on a weapons store in Blantyre

Blantyre is Malawi's centre of finance and commerce, and its second largest city, with a population of 800,264 . It is sometimes referred to as the commercial and industrial capital of Malawi as opposed to the political capital, Lilongwe. It is ...

followed during the night. By the morning of 24 January, the colonial authorities had mobilised the Nyasaland Volunteer Reserve (NVR) and called in regular troops from the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces regiment raised from Britain's East African colonies in 1902. It primarily carried out internal security duties within these colonies along with military service elsewher ...

(KAR). After a failed attack by KAR troops on Mbombwe on 25 January, the rebels attacked a Christian mission at Nguludi and burned it down. The KAR and NVR captured Mbombwe without encountering any resistance on 26 January. Many of the rebels, including Chilembwe himself, fled towards Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique () or Portuguese East Africa () were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese overseas province. Portuguese Mozambique originally constituted a str ...

, hoping to reach safety there, but many were captured. About 40 rebels were executed in the revolt's aftermath, and 300 were imprisoned; Chilembwe was shot dead by a police patrol near the border on 3 February.

Although the rebellion did not itself achieve success, it is commonly cited as a watershed moment in Malawian history. The rebellion had lasting effects on the British system of administration in Nyasaland, and some reforms were enacted in its aftermath. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the growing Malawian nationalist movement reignited interest in the Chilembwe revolt, and after the independence of Malawi in 1964 it became celebrated as a key moment in the nation's history. Chilembwe's memory, which remains prominent in the collective national consciousness, has often been invoked in symbolism and rhetoric by Malawian politicians. Today, the uprising is celebrated annually and Chilembwe himself is considered a national hero.

Background

British colonial rule in the region of modern-day

British colonial rule in the region of modern-day Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

, where the revolt occurred, began between 1899 and 1900, when the British sought to increase their formal control over the territory to preempt encroachment by the Portuguese or German colonial empire

The German colonial empire () constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies, and territories of the German Empire. Unified in 1871, the chancellor of this time period was Otto von Bismarck. Short-lived attempts at colonization by Kleinstaat ...

s. The region became a British protectorate

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

in 1891 as the British Central Africa Protectorate

The British Central Africa Protectorate (BCA) was a British protectorate proclaimed in 1889 and ratified in 1891 that occupied the same area as present-day Malawi: it was renamed Nyasaland in 1907. British interest in the area arose from visits ...

and in 1907 was named Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After ...

. Unlike many other parts of Africa, where British rule was dependent on the support of local factions, in Nyasaland British control rested on military superiority. During the 1890s the colonial authorities suppressed numerous rebellions by the local Yao, Ngoni and Chewa people

The Chewa are a Bantu ethnic group primarily found in Malawi and Zambia, with few populations in Zimbabwe and Mozambique. The Chewa are closely related to people in surrounding regions such as the Tumbuka. As with the Nsenga and Tumbuka, a sm ...

s.

British rule in Nyasaland radically altered the local indigenous power structures. The early colonial period saw some immigration and settlement by white colonists, who bought large swathes of territory from local chiefs, often for token payments in beads or guns. Most of the land acquired by white settlers, particularly in the Shire Highlands, was converted into plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

s where tea, coffee, cotton and tobacco were grown. The enforcement of colonial institutions, such as the Hut Tax

The hut tax was a form of taxation introduced by European colonial powers in their African colonies on a "per hut" (or other forms of household) basis. Colonised peoples paid the tax variously in money, labour, grain or stock. This benefited the ...

, compelled many indigenous people to find paid work and the demand for labour created by the plantations led to their becoming a major employer. Once employed on the plantations, black workers found that they were frequently beaten and subject to racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their Race (human categorization), race, ancestry, ethnicity, ethnic or national origin, and/or Human skin color, skin color and Hair, hair texture. Individuals ...

. Increasingly, the plantations were also forced to rely on a system, known locally as '' thangata'', which at best involved exacting considerable labour as rent in kind and frequently degenerated into forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

.

Chilembwe and his Church

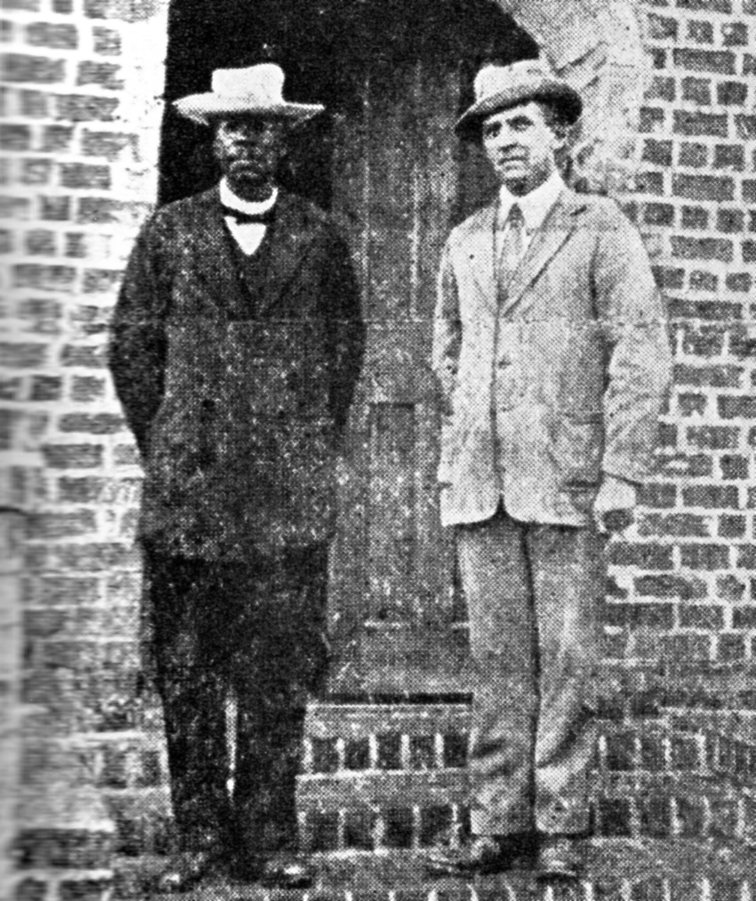

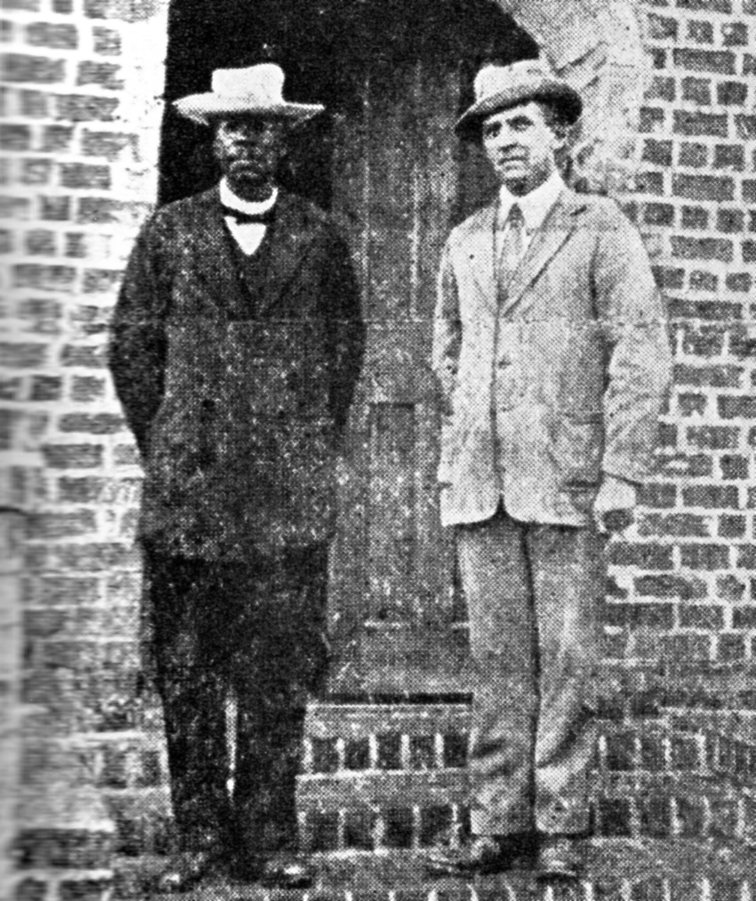

John Chilembwe

John Chilembwe (June 1871 – 3 February 1915) was a Baptist pastor, educator and revolutionary who trained as a minister in the United States, returning to Nyasaland in 1901. He was an early figure in the resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland ...

, born locally in around 1871, received his early education at a Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

mission and later met Joseph Booth, a radical Baptist missionary who ran the Zambezi Industrial Mission. Booth preached a form of egalitarianism and his progressive attitude towards race attracted Chilembwe's attention. Under Booth's patronage, Chilembwe travelled to the United States in 1897 for the purposes of higher education and to fundraise for Booth, beginning studies at the Virginia Theological Seminary

Virginia Theological Seminary (VTS), formally the Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary in Virginia, is an Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopal seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. It is the largest and second-oldest such accredited se ...

in Lynchburg in 1898. There he mixed in African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

circles and was influenced by stories of the abolitionist John Brown and the egalitarianist Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite#United S ...

.

Despite his Christian pacifist and visionary temperament, Booth was also highly critical of established institutions such as the colonial government and Protestant churches in Nyasaland. He was particularly hostile towards Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

missionaries in Blantyre

Blantyre is Malawi's centre of finance and commerce, and its second largest city, with a population of 800,264 . It is sometimes referred to as the commercial and industrial capital of Malawi as opposed to the political capital, Lilongwe. It is ...

, criticizing their affluent lifestyle in comparison to the poverty of local peasants. Both the colonial government and Presbyterian missionaries were concerned by Booth's "dangerous egalitarian spirit" and being "a determined advocate of racial equality, as well as being fundamentally opposed to the colonial state". Booth was also a staunch advocate of establishing his own industrial mission in addition to the religious one, and acquired 26,537 acres of land at Mitsidi with the help of Harry Johnston

Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927) was a British explorer, botanist, artist, colonial administrator, and linguist who travelled widely across Africa to speak some of the languages spoken by people on that continent. ...

. Despite the fact that Booth was an avid anti-colonialist and Johnston a colonial advocate, both men were united by their disdain for the Church of Scotland, and Johnston was eager to aid Booth in order to undermine the efforts of Scottish missionaries. Booth's industrial missions were to be "self-managed by educated Africans, and to be largely focussed on agricultural and industrial production". The missions were to be self-supporting and managed by African themselves, with European settlers only serving as guides and advisors. Booth had profound influence on Chilembwe, and his egalitarian and proto-nationalist ideals shaped Chilembwe's own views as well as his Baptist faith.

Having managed to become a competition to other Protestant missionaries, Booth attracted many missionary-educated Africans away from the Presbyterians by offering them exorbitant wages - an African worker was paid 18 shillings a month by Booth, whereas the normal rate in the 1890s was only around three shillings. However, he paid his own African labourers in calico

Calico (; in British usage since 1505) is a heavy plain-woven textile made from unbleached, and often not fully processed, cotton. It may also contain unseparated husk parts. The fabric is far coarser than muslin, but less coarse and thick than ...

, worth only around two shillings, which was actually less than the salary offered by the rest of European settlers. He founded the African Christian Union, where he emphasized the need for Africans themselves to govern their economy, rather than have the European colonists "drain the wealth of Africa". His organisation had three goals, namely "to spread the Christian gospel throughout the African continent; to establish what he termed 'Industrial Missions'; and finally, to restore Africa to the African". He advocated for African self-government, and envisioned self-sustainable African economies managed by educated Africans, placing particular emphasis on the production of tea, coffee, cocoa and sugar, as well as mining and manufacturing. Anthropologist Brian Morris notes a significant contradiction in Booth's views that Chilembwe ended up inheriting, being a staunch egalitarianist while also calling for a hierarchical plantation economy and highly capitalist society. To this end, both Chilembwe and Booth were "the embodiment of the protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism".

Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland in 1900 and, with the assistance of the African-American National Baptist Convention, he founded his independent church, the

Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland in 1900 and, with the assistance of the African-American National Baptist Convention, he founded his independent church, the Providence Industrial Mission

Providence Industrial Mission (PIM) was an independent church in Nyasaland, modern-day Malawi. The PIM was founded by John Chilembwe, who would later lead a rebellion against colonial rule, upon his return to Nyasaland in 1900 from the United S ...

, in the village of Mbombwe. He was considered a "model of non-violent African advancement" by the colonial authorities during the mission's early years. He established a chain of independent black African schools, with over 900 pupils in total and founded the Natives' Industrial Union, a form of cooperative union

A cooperative federation or secondary cooperative is a cooperative in which all members are, in turn, cooperatives.

Historically, cooperative federations have predominantly come in the form of cooperative wholesale societies and cooperative unions ...

that has been described as an "embryo chamber of commerce

A chamber of commerce, or board of trade, is a form of business network. For example, a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to a ...

". Nevertheless, Chilembwe's activities led to friction with the managers of the A. L. Bruce Estates, who feared Chilembwe's influence over their workers. In November 1913, employees of the A. L. Bruce Estates burnt down churches that Chilembwe or his followers had built on estate land.

Information about Chilembwe's Church before the rebellion is scant, but his ideology proved popular and he developed a strong local following. For at least the first 12 years of his ministry, he preached ideas of African self-respect and advancement through education, hard work and personal responsibility, as advocated by Booker T. Washington, and he encouraged his followers to adopt European-style dress and habits. His activities were initially supported by white Protestant missionaries. The Mission's schools meanwhile began teaching racial equality, based on Christian teaching and anti-colonialism. Many of his leading followers, several of whom participated in the uprising, came from the local middle-class, who had similarly adopted European customs. Chilembwe's acceptance of European culture created an unorthodox anti-colonial ideology based around a form of nationalism, rather than a desire to restore the pre-colonial social order.

Following Booth's example, Chilembwe engaged not only in educational work and evangelism, but also attempted to establish his own agricultural estate. He employed local Lomwe labourers on his plots of coffee, rubber, pepper ad cotton. He won the respect of both fellow Africans and European landowners, and until 1914 "government officials and European missionaries alike regarded Chilembwe with some favour". He became the local leader of emerging African planters and entrepreneurs, particularly attracted to his own Protestant church congregation. It was during this time that Chilembwe started identifying with the discontent of both African classes - the Lomwe immigrants whom he employed, as well as emerging African entrepreneurs. Both African classes were highly alienated by the ''thangata'' system, which required every tenant to work for the estate owner in order to pay their rent and "hut tax". Labour rent was imposed during the brief rainy season, which forced Africans to work on their landowner's land while having no time to tend to their own at the critical time of the year. African tenants also had to follow strict regulations, and were prohibited from acquiring timber or hunting animals. In addition, European landowners would often force their tenants to work for far more than the system allowed for, beat their workers with a whip and forced African widows to work on the land too. Chilembwe acted as a spokesman for the local Lomwe people.

Meanwhile, the African planters were frustrated by economic restrictions and social discrimination that they had to endure despite adopting the European way of life. They were unable to obtain freehold land or credit and didn't have the right to sign the labour-tax certificates of their employees, which undermined their chances of attracting workers. Additionally, the colonial government openly favoured the white landowners, who acted like "feudal lords" on their own. Every African planter was "obliged to take off his hat for any European, whether government official or not", and a failure to do so often meant physical and verbal abuse. White settlers and even Protestant ministers, despite preaching equality, resented the African planters, as the fact that educated Africans embraced European fashion and expected to be treated equally was considered "above their station". William Jervis Livingstone was particularly known for using derogatory phrases towards educated and landowning Africans, asking "whose slave they are". Morris identifies this discrimination as one of the main causes for the rebellion.

After 1912, Chilembwe became more radical and began to predict the liberation of the Africans and the end of colonial rule, and began to foster closer links with a number of other independent African churches. From 1914, he preached more militant sermons, often referring to Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

themes, concentrating on such aspects as the Israelites' escape from slavery in Egypt , Chilembwe himself was not part of the apocalyptic Watch Tower movement, which was popular in central Africa at the time and later became known as ''Kitawala'' in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but some of his followers may have been influenced by it. The leader of Watch Tower, Charles Taze Russell

Charles Taze Russell (February 16, 1852 – October 31, 1916), or Pastor Russell, was an American Adventist minister from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and founder of the Bible Student movement. He was an early Christian Zionist.

In July ...

had predicted that Armageddon

Armageddon ( ; ; ; from ) is the prophesied gathering of armies for a battle during the end times, according to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. Armageddon is variously interpreted as either a literal or a ...

would begin in October 1914, which some of Chilembwe's followers equated to an end to colonial rule.

World War I

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in July 1914. By September 1914, the war had spread to Africa as British and Belgian forces began the East African campaign against the German colonial empire. In Nyasaland, the major effect of the war was massive recruitment of Africans to serve as porters in support of Allied troops. Porters lived in extremely poor conditions which left them exposed to disease and mortality rates among them during the campaigns were high. At the same time, the recruitment of porters created a shortage of labour which increased the economic pressures on Africans in Nyasaland. Millenarians at the time believed that World War I would be a form of Armageddon

Armageddon ( ; ; ; from ) is the prophesied gathering of armies for a battle during the end times, according to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. Armageddon is variously interpreted as either a literal or a ...

, which they believed would destroy the colonial powers and pave the way for the emergence of independent African states.

Chilembwe opposed the recruitment of the Nyasan people to fight what he considered to be a war totally unconnected to them. He promoted a form of Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the Christian theology, theological and Christian ethics, ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is inco ...

and argued that the lack of civil rights for Africans in the colonial system should exempt them from the duties of military service. In November 1914, following reports of large loss of life during fighting at Karonga

Karonga is a township in the Karonga District in Northern Region of Malawi. Located on the western shore of Lake Nyasa, it was established as a slaving centre sometime before 1877. As of 2018 estimates, Karonga has a population of 61,609. Th ...

, Chilembwe wrote a letter to '' The Nyasaland Times'' in Blantyre, explicitly appealing to the colonial authorities not to recruit black troops:

Preparations

Preparations for the uprising had begun by the end of 1914. Exactly what Chilembwe's objectives were remains unclear but some contemporaries believed that he planned to make himself "King of Nyasaland". He soon acquired a military textbook and began to organise his followers and wider support. In particular, he formed close ties with Filipo Chinyama in Ncheu, to the north-west and received his assurance that he would also mobilise his followers to join the rebellion when it broke out. The colonial authorities received two warnings that a revolt was imminent. A disaffected follower of Chilembwe reported the preacher's "worrying intentions" to Philip Mitchell, a colonial civil servant (and future governor ofUganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

and Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

), in August 1914. A Catholic mission was also warned but neither took any action. Morris notes that no action was taken as the colonial authorities had no way to confirm the rumours, given the secretive way of the uprising.

Rebellion

Outbreak

During the night of Saturday 23–24 January, the rebels met at the Mission church in Mbombwe, where Chilembwe gave a speech stressing that none of them should expect to survive the reprisals that would follow the revolt but that the uprising would draw greater attention to their conditions and destabilise the colonial system. This, Chilembwe believed, was the only way change would ever occur. A contingent of rebels was sent toBlantyre

Blantyre is Malawi's centre of finance and commerce, and its second largest city, with a population of 800,264 . It is sometimes referred to as the commercial and industrial capital of Malawi as opposed to the political capital, Lilongwe. It is ...

and Limbe, about to the south, where most of the white settlers lived and where the insurgents hoped to capture the African Lakes Corporation

The African Lakes Corporation plc was a British company originally set-up in 1877 by Scottish businessmen to co-operate with Presbyterian missions in what is now Malawi. Despite its original connections with the Free Church of Scotland, it operated ...

(ALC)'s store of weapons. Another group headed towards the Alexander Livingstone Bruce Plantation's headquarters at Magomero

Magomero is an estate and a village in Malawi. It is situated south of Zomba.

History

Although Alexander Low Bruce never visited Nyasaland, he obtained title to some 170,000 acres of land there through his association with the African Lakes Comp ...

. Chilembwe sent a messenger to Ncheu to alert Chinyama that the rebellion was starting.

Chilembwe also sought support for his uprising from the colonial authorities in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

, on Nyasaland's far northern border, hoping that a German-led offensive from the north combined with an African insurrection in the south might force the British out of Nyasaland permanently. On 24 January, he sent a letter to the governor of German East Africa Heinrich Schnee

Heinrich Albert Schnee (Albert Hermann Heinrich Schnee; 4 February 1871 – 23 June 1949) was a German lawyer, colonial civil servant, politician, writer, and association official. He served as the last Governor of German East Africa.

Early ...

via courier through Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique () or Portuguese East Africa () were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese overseas province. Portuguese Mozambique originally constituted a str ...

. The courier was intercepted and Schnee never received the letter. During the latter stages of the East African campaign, after their invasion of Portuguese Mozambique, German colonial troops helped to suppress the anti-Portuguese Makombe and Barue uprisings, worrying that African rebellions would destabilise the colonial order.

Attack on the Livingstone Bruce Plantation

Mauser

Mauser, originally the Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik, was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols was produced beginning in the 1870s for the German armed forces. In the late 19th and ...

rifles captured from the plantation formed the basis of the rebel armoury for the rest of the uprising.

Mwanje had little military value but it has been proposed that the rebels may have hoped to find weapons and ammunition there. Led by Jonathan Chigwinya, the insurgents stormed one of the houses and killed the plantation's stock manager, Robert Ferguson, with a spear as he lay in bed reading a newspaper. Two of the colonists, John Robertson and his wife Charlotte, escaped into the cotton fields and walked to a neighbouring plantation to raise the alarm. One of the Robertsons' African servants, who remained loyal, was killed by the attackers.

Later actions

Tete

Tete may refer to:

* Tete, Mozambique, a city in Mozambique

*Tété (born 1975), a French musician

*Tetê (born 2000), a Brazilian footballer

*Tete Montoliu (1933–1997), Spanish jazz pianist

**''Tete!'', an album by Tete Montoliu

*Tete Province ...

and Blantyre– Mikalongwe telephone lines, delaying the spread of the news. At around 02:00 on 24 January, the ALC weapons store in Blantyre was attacked by a force of around 100 rebels before the general alarm had been raised by news of the Magomero and Mwanje attacks. Local settlers mobilised after an African watchman was shot dead by the rebels. The rebels were repulsed, but not before they had captured five rifles and some ammunition, which were taken back to Mbombwe. A number of rebels were taken prisoner during the retreat from Magomero.

After the initial attacks on the Bruce plantation, the rebels returned home. Livingstone's head was taken back and displayed at the Providence Industrial Mission on the second day of the uprising as Chilembwe preached a sermon. During much of the rebellion, Chilembwe remained in Mbombwe praying and leadership of the rebels was taken by David Kaduya, a former King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces regiment raised from Britain's East African colonies in 1902. It primarily carried out internal security duties within these colonies along with military service elsewher ...

(KAR) soldier. Under Kaduya's command, the rebels successfully ambushed a small party of KAR troops near Mbombwe on 24 January, described as the "one reverse suffered by the government" during the uprising.

By the morning of 24 January the colonial government had mustered the Nyasaland Volunteer Reserve (NVR), a unit that consisted of settler reservists

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person ca ...

, and redeployed the 1st Battalion of the KAR from the north of the colony. The rebels did not further attack any of the many other isolated plantations in the region. They also did not occupy the '' boma'' (fort) at Chiradzulu just from Mbombwe, even though it was ungarrisoned at the time. Rumours of rebel attacks spread, but despite earlier offers of support, there were no parallel uprisings elsewhere in Nyasaland and the promised reinforcements from Ncheu did not materialise. The Mlanje or Zomba regions likewise refused to join the uprising.

Siege of Mbombwe and attempted escape

KAR troops launched a tentative attack on Mbombwe on 25 January but the engagement proved inconclusive. Chilembwe's forces held a strong defensive position along the Mbombwe river and could not be pushed back. Two KAR soldiers were killed and three were wounded; Chilembwe's losses have been estimated as about 20.

On 26 January, a group of rebels attacked a

KAR troops launched a tentative attack on Mbombwe on 25 January but the engagement proved inconclusive. Chilembwe's forces held a strong defensive position along the Mbombwe river and could not be pushed back. Two KAR soldiers were killed and three were wounded; Chilembwe's losses have been estimated as about 20.

On 26 January, a group of rebels attacked a Catholic mission

Missionary work of the Catholic Church has often been undertaken outside the geographically defined parishes and dioceses by religious orders who have people and material resources to spare, and some of which specialized in missions. Eventually, p ...

at Nguludi belonging to Father Swelsen. The mission was defended by four African armed guards, one of whom was killed; Father Swelsen was also wounded in the fighting and the church was burnt down, resulting in the death of a young girl who was inside at the time. KAR and NVR troops assaulted Mbombwe again the same day but encountered no resistance. Many rebels, including Chilembwe, had fled the village disguised as civilians. Mbombwe's fall and the subsequent demolition of Chilembwe's church with dynamite by government soldiers ended the rebellion. Kaduya was captured and brought back to Magomero where he was publicly executed. This was the final attack of the rebellion, and Morris attributed the decision to attack the Catholic mission to "the pervasive anti-Catholic sentiments expressed by the independent Baptists".

Following the attacks, Chilembwe meditated on the summit of Chilimankhanje hill instead of attempting to regroup the now dispersed rebel troops. He was eventually convinced to leave the hill and escape to Mozambique, a land that he had already been to numerous times during his hunting trips. Chilembwe also wrote a letter to the German colonial authorities in Tunduru, asking for aid. He never received a response, and the letter was considered an embarrassment to his supporters, given Germany's reputation as a particularly oppressive colonial power.

After the defeat of the rebellion, most of the remaining insurgents attempted to escape eastwards across the Shire Highlands, towards Portuguese East Africa

Portuguese Mozambique () or Portuguese East Africa () were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese overseas province. Portuguese Mozambique originally constituted a str ...

, from where they hoped to head north to German-controlled territory. Chilembwe was spotted by a Nyasaland Police patrol and shot dead on 3 February near Mlanje. Many other rebels were captured; 300 were imprisoned following the rebellion and 40 were executed. Around 30 rebels evaded capture and settled in Portuguese territory near the Nyasaland border.

Aftermath

The colonial authorities responded quickly to the uprising with as much force and as many troops, policemen and settler volunteers it could muster to hunt down and kill suspected rebels. There was no official death toll, but perhaps 50 of Chilembwe's followers were killed in the fighting, when trying to escape after or summarily executed.S Hynde, (2010). ‘‘The extreme penalty of the law’’: mercy and the death penalty as aspects of state power in colonial Nyasaland, c. 1903 47. Journal of Eastern African Studies Vol. 4, No. 3, p. 547. Worrying that the rebellion might rapidly reignite and spread, the authorities instigated arbitrary reprisals against the local African population, including mass hut burnings. All weapons were confiscated and fines of 4 shillings per person were levied in the districts affected by the revolt, regardless of whether the people in question had been involved. As part of the repression, a series of courts were hastily convened which passed death sentences on forty-six men for the offences of murder and treason and 300 others were given prison sentences. Thirty-six were executed and, to increase the deterrent effect, some of the ringleaders were hanged in public on a main road close to the Magomero Estate where Europeans had been killed.D D Phiri, (1999). Let Us Die for Africa: An African Perspective on the Life and Death of John Chilembwe of Nyasaland. Central Africana, Blantyre, pp. 86–7. . The colonial government also began restricting the rights of Christian missionaries in Nyasaland and, although Anglican missions, those of the Scottish churches and Catholic missions were not affected, it banned many smaller, often American-originated churches, including the Churches of Christ and Watchtower Society, from Nyasaland, and placed restrictions on other African-run churches. Public gatherings, especially those associated with African-initiated religious groups, were banned until 1919. Fear of similar uprisings in other British colonies, notablyNorthern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North ...

, also led to similar repression of independent churches and foreign missions beyond Nyasaland.

Though the rebellion failed, the threat to British rule posed by the revolt compelled the colonial government to introduce some reform. The authorities proposed to undermine the power of independent churches like Chilembwe's by promoting secular education, but a lack of funding made this impossible. Colonial officials in Nyasaland began to promote tribal loyalties through the system of indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of public administration, governance used by imperial powers to control parts of their empires. This was particularly used by colonial empires like the British Empire to control their possessions in Colonisation of Afri ...

, which was expanded after the revolt. In particular, the Muslim Yao people, who attempted to distance themselves from Chilembwe, were given more power and autonomy. Although delayed by the war, the Nyasaland Police, which had been primarily composed of Africans conscripted by colonial officials, was restructured as a professional force of white settlers. Forced labour was retained, and would remain a source of resentment among Africans for decades afterwards.

While the uprising enjoyed levels of sympathy amongst Yao commoners, none of the Yao chiefs in the Shire Highlands supported it. Most of them embraced Islam instead of Christianity and considered African planters a threat to their political hegemony. The Commission of Enquiry dismissed the uprising as a localised affair caused by the harsh mistreatment of Africans by the Magomero

Magomero is an estate and a village in Malawi. It is situated south of Zomba.

History

Although Alexander Low Bruce never visited Nyasaland, he obtained title to some 170,000 acres of land there through his association with the African Lakes Comp ...

estate. However, the grievances expressed by Chilembwe were not unique to his area, and Africans across Nyasaland identified with his struggle. Africans had no rights as tenants under the ''thangata'' system, had to pay rent in labour and were prohibited from gathering wood or hunting wild animals in the woodlands surrounding European estates, even though they considered woodland resources to be common property. Historians have noted that while the colonial authorities did suppress slave trading in Nyasaland, the ''thangata'' system was seen by many Africans as a new form of slavery.

The rebels were of diverse social and economic backgrounds, consisting of Yao people, Lomwe immigrants, agricultural farmers and African petty bourgeoisie. The colonial authorities ignored African petitions and failed to translate their laws into local languages, leading to many locals not understanding them at all. Morris noted that Africans of Nyasaland were becoming increasingly hostile to colonial rule due to mistreatment they experienced on white-owned plantations, and if the rebels had managed to acquire German support and acquire weapon caches during the attack on the ALC weapons store in Blantyre, it could have turned into "a wider and more protracted struggle". Morris concludes that the rebellion was a response to colonial oppression, particularly towards racial injustice. It was a "struggle for freedom" with elements of Christian utopianism, with Chilembwe expressing two contrasting political traditions - Booth's radical egalitarianism and a "petty capitalist orientation" of the Protestant churches, which stressed the right to private property, wage labour and commercial agriculture.

Commission of Enquiry

In the aftermath of the revolt, the colonial administration formed a Commission of Enquiry to examine the causes and handling of the rebellion. The Commission, which presented its conclusions in early 1916, found that the revolt was chiefly caused by mismanagement of the Bruce plantation. The Commission also blamed Livingstone himself for "treatment of natives hat wasoften unduly harsh" and for poor management of the estate. The Commission found that the systematic discrimination, lack of freedoms and respect were key causes of resentment among the local population. It also emphasised the effect of Booth's ideology on Chilembwe. The Commission's reforms were not far-reaching—though it criticised the ''thangata'' system, it made only minor changes aimed at ending "casual brutality". Though the government passed laws banning plantation owners from using the services of their tenants as payment of rent in 1917, effectively abolishing ''thangata'', it was "uniformly ignored". A further Commission in 1920 concluded that the ''thangata'' could not be effectively abolished, and it remained a constant source of friction into the 1950s.In later culture

Despite its failure, the Chilembwe uprising has since gained an important place in the modern Malawian cultural memory, with Chilembwe himself gaining "iconic status". The uprising had "local notoriety" in the years immediately after it, and former rebels were kept under police observation. Over the next three decades, local anti-colonial activists idealised Chilembwe and began to see him as a semi-mythical figure. The

Despite its failure, the Chilembwe uprising has since gained an important place in the modern Malawian cultural memory, with Chilembwe himself gaining "iconic status". The uprising had "local notoriety" in the years immediately after it, and former rebels were kept under police observation. Over the next three decades, local anti-colonial activists idealised Chilembwe and began to see him as a semi-mythical figure. The Nyasaland African Congress

The Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) was an organisation that evolved into a political party in Nyasaland during the colonial period. The NAC was suppressed in 1959, but was succeeded in 1960 by the Malawi Congress Party, which went to on decisiv ...

(NAC) of the 1940s and 1950s used him as a symbolic figurehead, partly because its president, James Chinyama, had a family connection to Filipo Chinyama, who had been believed to be an ally of Chilembwe's. When the NAC announced that it intended to mark 15 February annually as Chilembwe Day, colonial officials were scandalised. One wrote that to "venerate the memory of the fanatic and blood thirsty Chilembwe seems to us to be nothing less than a confession of violent intention."

Historian Desmond Dudwa Phiri characterised Chilembwe's uprising as an early expression of Malawian nationalism, as did George Shepperson and Thomas Price in their 1958 book ''Independent African'', an exhaustive study of Chilembwe and his rebellion that was banned during the colonial era but still widely read by Nyasaland's educated class. Chilembwe became viewed as an "unproblematic" hero by many of the country's people. The Malawi Congress Party

The Malawi Congress Party (MCP) is a political party in Malawi. It was formed as a successor party to the banned Nyasaland African Congress when the country, then known as Nyasaland, was under British rule. The MCP, under Hastings Banda, pre ...

, which ultimately led the country to independence in 1964, made a conscious effort to identify its leader Hastings Banda

Hastings Kamuzu Banda ( – 25 November 1997) was a Malawian politician and statesman who served as the leader of Malawi from 1964 to 1994. He served as Prime Minister of Malawi, Prime Minister from independence in 1964 to 1966, when Malawi was ...

with Chilembwe through speeches and radio broadcasts. Bakili Muluzi

Elson Bakili Muluzi (born 17 March 1943) is a Malawian politician who was President of Malawi from 1994 to 2004. He was also chairman of the United Democratic Front (UDF) until 2009. He succeeded Hastings Kamuzu Banda as Malawi's president. He al ...

, who succeeded Banda in 1994, similarly invoked Chilembwe's memory to win popular support, inaugurating a new annual national holiday, Chilembwe Day, on 16 January 1995. Chilembwe's portrait was soon added to the national currency, the kwacha, and reproduced on Malawian stamps. It has been argued that for Malawian politicians, Chilembwe has become "symbol, legitimising myth, instrument and propaganda".

Historical analysis

The revolt has been the subject of much research and has been interpreted in various ways by historians. At the time, the uprising was generally considered to mark a turning point in British colonial rule. The governor of Nyasaland, George Smith, declared that the revolt marked a "new phase in the existence of Nyasaland". According to historianHew Strachan

Sir Hew Francis Anthony Strachan, ( ; born 1 September 1949) is a British military historian, well known for his leadership in scholarly studies of the British Army and the history of the First World War. He is currently professor of internatio ...

, the Chilembwe uprising tarnished British prestige in East Africa which contributed, after the appointment of the future Prime Minister Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law (; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a Canadi ...

as Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, to renewed pressure for an Anglo-Belgian offensive against German East Africa.

Chilembwe's aims have also come under scrutiny. According to Robert I. Rotberg, Chilembwe's speech of 23 January appeared to stress the importance and inevitability of martyrdom as a principal motivation. The same speech depicted the uprising as a manifestation of desperation but because of his desire to "strike a blow and die", he did not have any idea of what he would replace colonialism with if the revolt succeeded. Rotberg concludes that Chilembwe planned to seize power in the Shire Highlands or perhaps in all of Nyasaland. John McCracken attacks the idea that the revolt could be considered nationalist, arguing that Chilembwe's ideology was instead fundamentally utopian and created in opposition to localised abuses of the colonial system, particularly ''thangata''. According to McCracken, the uprising failed because Chilembwe was over-reliant on a small Europeanised ''petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

'' and did not gain enough mass support. Rotberg's examination the Chilembwe revolt from a psychoanalytical perspective concludes that Chilembwe's personal situation, his psychosomatic asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

and financial debt may have been contributory factors in his decision to plot the rebellion.

See also

* Bussa rebellion—A 1915 uprising against British indirect rule in northernNigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

* ''Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in Shona. The Ndebele equivalent is not as widely used since most Zimbabweans speak Shona; it is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical terms, it also refers to the Ndebele ...

''—A rebellion against the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal: the process of dealing with or controlling things or people.

** Administrative assistant, traditionally known as a se ...

in nearby Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

in 1896–97

* History of Malawi

The history of Malawi covers the area of present-day Malawi. The region was once part of the Maravi Empire (Maravi was a kingdom which straddled the current borders of Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia, in the 16th century). In colonial times, ...

* Maji Maji Rebellion

The Maji Maji Rebellion (, ) was an armed rebellion of Africans against German colonial rule in German East Africa (modern-day Tanzania). The war was triggered by German colonial policies designed to force the indigenous population to grow cott ...

—A war against German colonial rule in East Africa, 1905–08

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

"John Chilembwe: Brief life of an anticolonial rebel: 1871?–1915"

at ''

Harvard Magazine

''Harvard Magazine'' is an independently edited magazine and separately incorporated affiliate of Harvard University. It is the only publication covering the entire university and regularly distributed to all graduates, faculty, and staff.

The ...

''

{{British colonial campaigns

1910s in Nyasaland

1915 in Africa

1915 in the British Empire

20th century in Malawi

20th-century rebellions

African resistance to colonialism

African theatre of World War I

Conflicts in 1915

January 1915

Millenarianism

Nyasaland in World War I

Opposition to World War I

Rebellions against the British Empire

Rebellions in Africa

Wars involving Malawi