Chernobyl - Final Warning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the

The city's name is the same as one of the

The city's name is the same as one of the

Chornobyl

''.

"Chernobyl"

'' The Sarmatian Review, vol. 15'', No. 1, Polish Institute of Houston at

On 26 April 1986, one of the reactors at the

On 26 April 1986, one of the reactors at the

State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management

– official information on public works, zone status, visits, etc.

– State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management

Online map

Chernobyl

– History of Jewish Communities in Ukraine ''JewUa.org''

The Chernobyl Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chernobyl (City) 1193 establishments in Europe 12th-century establishments in Ukraine * Cities in Kyiv Oblast Cities of district significance in Ukraine Cossack Hetmanate Environmental disaster ghost towns Ghost towns in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone Holocaust locations in Ukraine Radomyslsky Uyezd Kiev Voivodeship Historic Jewish communities in Poland Jewish Ukrainian history Rus' settlements Shtetls

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, Belarusian: Хона адчужэння Чарнобыльскай АЭС, ''Zona adčužennia Čarnobyĺskaj AES'', russian: Зона отчуждения Чернобыльской АЭС, ...

, situated in the Vyshhorod Raion

Vyshhorod Raion () is a raion (district) in Kyiv Oblast of Ukraine. Its administrative center is the city of Vyshhorod. It has a population of

On 18 July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, the number of raions of Kyiv Oblast ...

of northern Kyiv Oblast

Kyiv Oblast ( uk, Ки́ївська о́бласть, translit=Kyïvska oblast), also called Kyivshchyna ( uk, Ки́ївщина), is an oblast (province) in central and northern Ukraine. It surrounds, but does not include, the city of Kyiv, w ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

. Chernobyl is about north of Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

, and southwest of the Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

ian city of Gomel

Gomel (russian: Гомель, ) or Homiel ( be, Гомель, ) is the administrative centre of Gomel Region and the second-largest city in Belarus with 526,872 inhabitants (2015 census).

Etymology

There are at least six narratives of the or ...

. Before its evacuation, the city had about 14,000 residents, while around 1,000 people live in the city today.

First mentioned as a ducal

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

hunting lodge in 1193, the city has changed hands multiple times over the course of history. Jews moved into the city in the 16th century, and a now-defunct monastery was established in the area in 1626. By the end of the 18th century, Chernobyl was a major centre of Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

under the Twersky Dynasty

Chernobyl ( yi, טשערנאָביל) is a Hasidic dynasty that was founded by Grand Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky, known by the name of his work as the ''Meor Einayim''. The dynasty is named after the northern Ukrainian town of Chernobyl, wher ...

, who left Chernobyl after the city was subject to pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian E ...

in the early 20th century. The Jewish community was later murdered during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. Chernobyl was chosen as the site of Ukraine's first nuclear power plant in 1972, located north of the city, which opened in 1977. Chernobyl was evacuated on 5 May 1986, nine days after a catastrophic nuclear disaster at the plant, which was the largest nuclear disaster in history. Along with the residents of the nearby city of Prypiat

Pripyat ( ; russian: При́пять), also known as Prypiat ( uk, При́пʼять, , ), is an abandoned city in northern Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 19 ...

, which was built as a home for the plant's workers, the population was relocated to the newly built city of Slavutych

Slavutych ( uk, Славу́тич) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, purpose-built for the evacuated personnel of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant after the 1986 disaster that occurred near the city of Pripyat. Geographically ...

, and most have never returned.

The city was the administrative centre

An administrative center is a seat of regional administration or local government, or a county town, or the place where the central administration of a commune is located.

In countries with French as administrative language (such as Belgium, L ...

of Chernobyl Raion

The Chernobyl Raion (russian: Чернобыльский район, translit=Chernobyl'skiy rayon) or Chornobyl Raion ( uk, Чорнобильський район, translit=Chornobylskyi raion) was one of 26 administrative raions (districts) o ...

(district) from 1923. After the disaster, in 1988, the raion was dissolved and administration was transferred to the neighbouring Ivankiv Raion

Ivankiv Raion () was a raion (district) in Kyiv Oblast of Ukraine. Its administrative center was the urban-type settlement of Ivankiv. The raion was abolished on 18 July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the numbe ...

. The raion was abolished on 18 July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Kyiv Oblast to seven. The area of Ivankiv Raion was merged into Vyshhorod Raion

Vyshhorod Raion () is a raion (district) in Kyiv Oblast of Ukraine. Its administrative center is the city of Vyshhorod. It has a population of

On 18 July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, the number of raions of Kyiv Oblast ...

.

Although Chernobyl is primarily a ghost town today, a small number of people still live there, in houses marked with signs that read, "Owner of this house lives here", and a small number of animals live there as well. Workers on watch and administrative personnel of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, Belarusian: Хона адчужэння Чарнобыльскай АЭС, ''Zona adčužennia Čarnobyĺskaj AES'', russian: Зона отчуждения Чернобыльской АЭС, ...

are also stationed in the city. The city has two general stores and a hotel.

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chernobyl became the site of the Battle of Chernobyl

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was captured on 24 February (the first day of the invasion) by the Russian Armed Forces, who entered Ukrainian territory from neighbouring Belarus and seized the entire ...

and Russian forces occupied the city between 24 February and 2 April. After its capture, it was reported that radiation levels began rising.

Etymology

The city's name is the same as one of the

The city's name is the same as one of the Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* Som ...

names for ''Artemisia vulgaris

''Artemisia vulgaris'', the common mugwort, is a species of flowering plant in the daisy family Asteraceae. It is one of several species in the genus '' Artemisia'' commonly known as mugwort, although ''Artemisia vulgaris'' is the species most ...

'', mugwort

Mugwort is a common name for several species of aromatic flowering plants in the genus ''Artemisia.'' In Europe, mugwort most often refers to the species ''Artemisia vulgaris'', or common mugwort. In East Asia the species ''Artemisia argyi'' is ...

or common wormwood

Wormwood may refer to:

Biology

* Several plants of the genus ''Artemisia'':

** ''Artemisia abrotanum'', southern wormwood

** '' Artemisia absinthium'', common wormwood, grande wormwood or absinthe wormwood

** ''Artemisia annua'', sweet wormwood o ...

: (or more commonly , 'common artemisia').Etymology from O. S. Melnychuk, ed. (1982–2012), ''Etymolohichnyi slovnyk ukraïnsʹkoï movy'' (Etymological dictionary of the Ukrainian language) v 7, Kyiv: Naukova Dumka. The name is inherited from or , a compound of + , the parts related to and , 'stalk', so named in distinction to the lighter-stemmed wormwood '' A. absinthium''.

The name in languages used nearby is:

* uk, Чорнобиль, Chornobyl′,

* be, Чарнобыль, Čarnobyĺ,

*, .

The name in languages formerly used in the area is:

* pl, Czarnobyl,

* yi, טשערנאָבל, Tshernobl, .

In English, the Russian-derived spelling ''Chernobyl'' has been commonly used, but some style guides recommend the spelling ''Chornobyl'', or the use of romanized Ukrainian names for Ukrainian places generally.

History

The PolishGeographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland

The Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and other Slavic Countries ( pl, Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich) is a monumental Polish gazetteer, published 1880–1902 in Warsaw by Filip Sulimie ...

of 1880–1902 states that the time the city was founded is not known.

Identity of Ptolemy's "Azagarium"

Some older geographical dictionaries and descriptions of modernEastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

mention "Czernobol" (Chernobyl) with reference to Ptolemy's world map

The Ptolemy world map is a map of the world known to Greco-Roman societies in the 2nd century. It is based on the description contained in Ptolemy's book ''Geography'', written . Based on an inscription in several of the earliest surviving manusc ...

(2nd century AD). Czernobol is identified as Azagarium k "oppidium Sarmatiae" (Lat., "a city in Sarmatia"), by the 1605 ''Lexicon geographicum'' of Filippo Ferrari

Filippo Ferrari (Philippus Ferrarius) (1551 – 1626) was an Italian Servite monk and scholar, known as a geographer, and also noted as a hagiographer.

Life

He was born at Oviglio in Piedmont. It is near Alessandria, and he was nicknamed ''Al ...

and the 1677 ''Lexicon Universale

The ''Lexicon Universale'' of 1698 is an early modern humanist encyclopedia in Latin by Johann Jacob Hofmann of Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen ...

'' of Johann Jakob Hofmann. According to the ''Dictionary of Ancient Geography'' of Alexander Macbean

Alexander Macbean (died 1784) was a British writer and amanuensis, known as a lexicographer.

Life

Macbean worked as amanuensis for Ephraim Chambers; and then was one of the six amanuenses employed '' Johnson's Dictionary''. About 1758 he obtained ...

(London, 1773), Azagarium is "a town of Sarmatia Europaea

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th centur ...

, on the Borysthenes

Borysthenes (; grc, Βορυσθένης) is a geographical name from classical antiquity. The term usually refers to the Dnieper River and its eponymous river god, but also seems to have been an alternative name for Pontic Olbia, a town situate ...

" (Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine ...

), 36° East longitude and 50°40' latitude. The city is "now supposed to be ''Czernobol'', a town of Poland, in Red Russia nowiki/>Red Ruthenia">Red_Ruthenia.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Red Ruthenia">nowiki/>Red Ruthenia in the Palatinate of Kiow [see Kiev Voivodeship], not far from the Borysthenes."

Whether Azagarium is indeed Czernobol is debatable. The question of Azagarium's correct location was raised in 1842 by Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg-Slovaks, Slovak historian, Pavel Jozef Šafárik

Pavel Jozef Šafárik ( sk, Pavol Jozef Šafárik; 13 May 1795 – 26 June 1861) was an ethnic Slovak philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavists.

Fam ...

, who published a book titled "Slavic Ancient History" ("Sławiańskie starożytności"), where he claimed Azagarium to be the hill of Zaguryna, which he found on an old Russian map "Bolzoj czertez" (Big drawing) near the city of Pereiaslav

Pereiaslav ( uk, Перея́слав, translit=Pereiaslav, yi, פּרעיאַסלעוו, Periyoslov) is a historical city in the Boryspil Raion, Kyiv Oblast (province) of central Ukraine, located near the confluence of Alta and Trubizh rivers ...

, now in central Ukraine

Central Ukraine ( uk, Центральна Україна, ''Tsentralna Ukraina'') consists of historical regions of left-bank Ukraine and right-bank Ukraine that reference to the Dnipro River. It is situated away from the Black Sea Littoral ...

.

In 2019, Ukrainian architect Boris Yerofalov-Pylypchak published a book, ''Roman Kyiv or Castrum Azagarium at Kyiv-Podil

Podil ( uk, Поділ) or the Lower cityIvankin, H., Vortman, D. Podil (ПОДІЛ)'. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. is a historic neighborhood in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. It is located on a floodplain terrace over the Dnieper betwe ...

''.

12th to 18th century

The archaeological excavations that were conducted in 2005–2008 found a cultural layer from the 10–12th centuries AD, which predates the first documentary mention of Chernobyl. Around the 12th century Chernobyl was part of the land of Kievan Rus′. The first known mention of the settlement as Chernobyl is from an 1193 charter, which describes it as a hunting lodge ofKnyaz

, or (Old Church Slavonic: Кнѧзь) is a historical Slavic title, used both as a royal and noble title in different times of history and different ancient Slavic lands. It is usually translated into English as prince or duke, dependi ...

Rurik Rostislavich Rurik Rostislavich ( Russian and Ukrainian: Рюрик Ростиславич) (died 1215), Prince of Novgorod (1170–1171), Belgorod Kievsky (currently Bilohorodka; 1173–1194), Grand Prince of Kiev (Kyiv, 1173, 1180–1181, 1194–1201, 1203� ...

.Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor a ...

, '' Europe: A History'', Oxford University Press, 1996, In 1362Petro Tronko

Petro Timofiyovich Tronko ( uk, Петро́ Тимофі́йович Тронько́; 12 July 1915 - 12 September 2011) was a Ukrainian academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and veteran of World War II.

He was a head of edit ...

. Chornobyl

''.

The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR

''The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR'' ( uk, Історія міст і сіл Української РСР) is a Ukrainian encyclopedia, published in 26 volumes. It provides knowledge about the history of all populated place ...

. it was a crown village of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

. Around that time the town had own castle which was ruined at least on two occasions in 1473 and 1482. The Chernobyl castle was rebuilt in the first quarter of the 16th century being located nearby the settlement in a hard to reach area. With revival of the castle, Chernobyl became a county seat. In 1552 it accounted for 196 buildings with 1,372 residents, out of which over 1,160 were considered city dwellers. In the city were developing various crafts professions such as blacksmith, cooper among others. Near Chernobyl has been excavated bog iron

Bog iron is a form of impure iron deposit that develops in bogs or swamps by the chemical or biochemical oxidation of iron carried in solution. In general, bog ores consist primarily of iron oxyhydroxides, commonly goethite (FeO(OH)).

Iron-bear ...

, out of which was produced iron. The village was granted to Filon Kmita

Filon Kmita (1530 Kyiv Voivodeship – 1587), also known as Kmita the Chernobylan, was a noble in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Filon Kmita was notable for conducting counter-intelligence in the Muscovite wa ...

, a captain of the royal cavalry, as a fiefdom

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of ...

in 1566. Following the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

, the province where Chernobyl is located was transferred to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland in 1569. Under the Polish Crown, Chernobyl became a seat of eldership (starostwo

Starostwo (literally "eldership") ; be, староства, translit=starostva; german: Starostei is an administrative unit established from the 14th century in the Polish Crown and later in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the part ...

). During that period Chernobyl was inhabited by Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* Som ...

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s, some Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

people and a relatively large number of Jews. Jews were brought to Chernobyl by Filon Kmita

Filon Kmita (1530 Kyiv Voivodeship – 1587), also known as Kmita the Chernobylan, was a noble in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Filon Kmita was notable for conducting counter-intelligence in the Muscovite wa ...

, during the Polish campaign of colonization. The first mentioning of Jewish community in Chernobyl is in the 17th century. In 1600 in the city was built the first kosciol (Polish word for the Roman Catholic church). Local population was persecuted for holding Eastern Orthodox rite services. The traditionally Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canoni ...

Ukrainian peasantry around the town were forcibly converted, by Poland, to the Ruthenian Uniate Church

The Ruthenian Uniate Church (Belarusian: Руская Уніяцкая Царква; Ukrainian: Руська Унійна Церква; la, Ecclesia Ruthena unita; pl, Ruski Kościół Unicki) was a particular church of the Catholic Church i ...

. In 1626, during the Counter-reformation, a Dominican church and monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

were founded by Lukasz Sapieha. A group of Old Catholics

The terms Old Catholic Church, Old Catholics, Old-Catholic churches or Old Catholic movement designate "any of the groups of Western Christians who believe themselves to maintain in complete loyalty the doctrine and traditions of the undivide ...

opposed the decrees of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

. The Chernobyl residents actively supported the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising,; in Ukraine known as Khmelʹnychchyna or uk, повстання Богдана Хмельницького; lt, Chmelnickio sukilimas; Belarusian: Паўстанне Багдана Хмяльніцкага; russian: в ...

(1648–1657).

With the signing of the Truce of Andrusovo

The Truce of Andrusovo ( pl, Rozejm w Andruszowie, russian: Андрусовское перемирие, ''Andrusovskoye Pieriemiriye'', also sometimes known as Treaty of Andrusovo) established a thirteen-and-a-half year truce, signed in 1667 be ...

in 1667, Chernobyl was secured after the Sapieha family

The House of Sapieha (; be, Сапега, ''Sapieha''; lt, Sapiega) is a Polish-Lithuanian noble and magnate family of Lithuanian and Ruthenian origin,Энцыклапедыя ВКЛ. Т.2, арт. "Сапегі" descending from the medie ...

. Sometime in the 18th century, the place was passed on to the Chodkiewicz

The House of Chodkiewicz ( be, Хадкевіч; lt, Chodkevičius) was one of the most influential noble families of Lithuanian- Ruthenian descent within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th and 17th century.Chester S. L. Dunning, ...

family. In the mid-18th century the area around Chernobyl was engulfed in a number of peasant riots, which caused Prince Riepnin to write from Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

to Major General Krechetnikov, requesting hussars to be sent from Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the Polish–Russian ...

, in 1793 Chernobyl was annexed by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

Davies, Norman

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor at ...

(1995"Chernobyl"

'' The Sarmatian Review, vol. 15'', No. 1, Polish Institute of Houston at

Rice University

William Marsh Rice University (Rice University) is a private research university in Houston, Texas. It is on a 300-acre campus near the Houston Museum District and adjacent to the Texas Medical Center. Rice is ranked among the top universit ...

, . and became part of Radomyshl

Radomyshl ( uk, Радомишль, translit., ''Radomyshl’'', pl, Radomyśl, yi, ראַדאָמישל, russian: Радомышль) is a historic city in Zhytomyr Raion, Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. Prior to 2020, it was t ...

county (''uezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd; rus, уе́зд, p=ʊˈjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context ( uk, повіт), or Kreis in Baltic-German context, was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Russian Empire, and the e ...

'') as a supernumerary town

Supernumerary town (russian: Заштатный город, zashtatny gorod; russian: безуездный город, bezuyezdny gorod, lit=county-less city, label=none, ") was a type of a city in the Russian Empire which was not an administrativ ...

("zashtatny gorod"). Many of the Uniate Church

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

converts returned to Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canoni ...

y.

In 1832, following the failed Polish November Uprising, the Dominican monastery was sequestrated. The church of the Old Catholics was disbanded in 1852.

Until the end of the 19th century, Chernobyl was a privately owned city that belonged to the Chodkiewicz

The House of Chodkiewicz ( be, Хадкевіч; lt, Chodkevičius) was one of the most influential noble families of Lithuanian- Ruthenian descent within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th and 17th century.Chester S. L. Dunning, ...

family. In 1896 they sold the city to the state, but until 1910 they owned a castle and a house in the city.

In the second half of the 18th century, Chernobyl became a major centre of Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

. The Chernobyl Hasidic dynasty had been founded by Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky

Menachem Nochum Twersky of Chernobyl (born 1730, , Volhynia - died 1787, Chernobyl, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) was a Ukrainian rabbi, and the founder of the Chernobyl Hasidic dynasty. He was a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid o ...

. The Jewish population suffered greatly from pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s in October 1905 and in March–April 1919; many Jews were killed or robbed at the instigation of the Russian nationalist Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in ...

. When the Twersky Dynasty left Chernobyl in 1920, it ceased to exist as a center of Hasidism.

Chernobyl had a population of 10,800 in 1898, including 7,200 Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

. In the beginning of March 1918 Chernobyl was occupied in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

by German forces (see Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

).

Soviet times (1920–1991)

Ukrainians andBolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

fought over the city in the ensuing Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

. In the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

of 1919–20, Chernobyl was taken first by the Polish Army and then by the cavalry of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. From 1921 onwards, it was officially incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

.

Between 1929 and 1933, Chernobyl suffered from killings during Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

campaign. It was also affected by the famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accom ...

that resulted from Stalin's policies. The Polish and German community of Chernobyl was deported to Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

in 1936, during the Frontier Clearances The Polish minority in the Soviet Union are Polish diaspora who used to reside near or within the borders of the Soviet Union before its dissolution. Some of them continued to live in the post-Soviet states, most notably in Lithuania, Belarus, and U ...

.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Chernobyl was occupied by the German Army from 25 August 1941 to 17 November 1943. The Jewish community was murdered during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

.

In 1972, the Duga-1 radio receiver, part of the larger Duga over-the-horizon radar

Over-the-horizon radar (OTH), sometimes called beyond the horizon radar (BTH), is a type of radar system with the ability to detect targets at very long ranges, typically hundreds to thousands of kilometres, beyond the radar horizon, which is ...

array, began construction west-northwest of Chernobyl. It was the origin of the Russian Woodpecker and was designed as part of an anti-ballistic missile early warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum t ...

network.

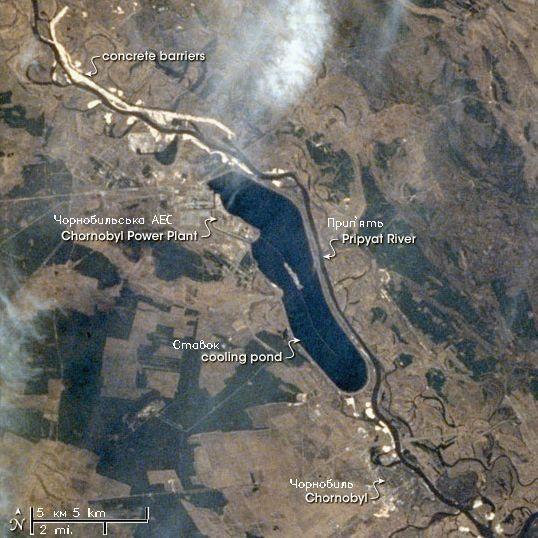

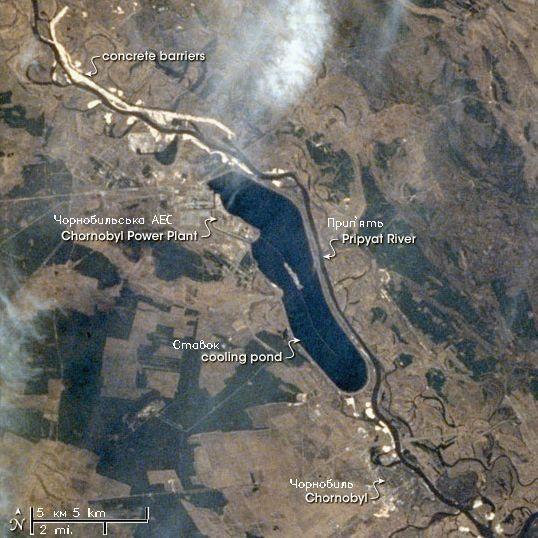

On 15 August 1972, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP; ; ), is a nuclear power plant undergoing decommissioning. ChNPP is located near the abandoned city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine northwest of the city of Chernobyl, from the Belarus–Ukraine bor ...

(officially the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant) began construction about northwest of Chernobyl. The plant was built alongside Pripyat

Pripyat ( ; russian: При́пять), also known as Prypiat ( uk, При́пʼять, , ), is an abandoned city in northern Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 1 ...

, an "atomograd

A closed city or closed town is a settlement where travel or residency restrictions are applied so that specific authorization is required to visit or remain overnight. Such places may be sensitive military establishments or secret research ins ...

" city founded on 4 February 1970 that was intended to serve the nuclear power plant. The decision to build the power plant was adopted by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union

The Council of Ministers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( rus, Совет министров СССР, r=Sovet Ministrov SSSR, p=sɐˈvʲet mʲɪˈnʲistrəf ɛsɛsɛˈsɛr; sometimes abbreviated to ''Sovmin'' or referred to as the '' ...

on recommendations of the State Planning Committee

The State Planning Committee, commonly known as Gosplan ( rus, Госплан, , ɡosˈpɫan),

was the agency responsible for economic planning, central economic planning in the Soviet Union. Established in 1921 and remaining in existence until ...

that the Ukrainian SSR be its location. It was the first nuclear power plant to be built in Ukraine.

Independent Ukraine (1991–present)

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Chernobyl remained part ofUkraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, Belarusian: Хона адчужэння Чарнобыльскай АЭС, ''Zona adčužennia Čarnobyĺskaj AES'', russian: Зона отчуждения Чернобыльской АЭС, ...

which Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

Russian occupation (February–April 2022)

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chernobyl became the site of theBattle of Chernobyl

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was captured on 24 February (the first day of the invasion) by the Russian Armed Forces, who entered Ukrainian territory from neighbouring Belarus and seized the entire ...

and Russian forces captured the city on 24 February. After its capture, Ukrainian officials reported that the radiation levels started to rise due to recent military activity causing radioactive dust to ascend into the air. Hundreds of Russian soldiers were suffering from radiation poisoning after digging trenches in a contaminated area, and one died. On 31 March it was reported that Russian forces had left the exclusion zone. Ukrainian authorities reasserted control over the area on 2 April.

Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster

On 26 April 1986, one of the reactors at the

On 26 April 1986, one of the reactors at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP; ; ), is a nuclear power plant undergoing decommissioning. ChNPP is located near the abandoned city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine northwest of the city of Chernobyl, from the Belarus–Ukraine bor ...

exploded after unsanctioned experiments on the reactor by plant operators were done improperly. The resulting loss of control was due to design flaws of the RBMK

The RBMK (russian: реактор большой мощности канальный, РБМК; ''reaktor bolshoy moshchnosti kanalnyy'', "high-power channel-type reactor") is a class of graphite moderated reactor, graphite-moderated nuclear react ...

reactor, which made it unstable when operated at low power, and prone to thermal runaway where increases in temperature increase reactor power output.

Chernobyl city was evacuated nine days after the disaster. The level of contamination with caesium-137

Caesium-137 (), cesium-137 (US), or radiocaesium, is a radioactive isotope of caesium that is formed as one of the more common fission products by the nuclear fission of uranium-235 and other fissionable isotopes in nuclear reactors and nucl ...

was around 555 kBq

The becquerel (; symbol: Bq) is the unit of radioactivity in the International System of Units (SI). One becquerel is defined as the activity of a quantity of radioactive material in which one nucleus decays per second. For applications relat ...

/m2 (surface ground deposition in 1986).

Later analyses concluded that, even with very conservative estimates, relocation of the city (or of any area below 1500 kBq

The becquerel (; symbol: Bq) is the unit of radioactivity in the International System of Units (SI). One becquerel is defined as the activity of a quantity of radioactive material in which one nucleus decays per second. For applications relat ...

/m2) could not be justified on the grounds of radiological health.

This however does not account for the uncertainty in the first few days of the accident about further depositions and weather patterns.

Moreover, an earlier short-term evacuation could have averted more significant doses from short-lived isotope radiation (specifically iodine-131

Iodine-131 (131I, I-131) is an important radioisotope of iodine discovered by Glenn Seaborg and John Livingood in 1938 at the University of California, Berkeley. It has a radioactive decay half-life of about eight days. It is associated with nu ...

, which has a half-life of about eight days).

Estimates of health effects are a subject of some controversy, see Effects of the Chernobyl disaster

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster triggered the release of radioactive contamination into the atmosphere in the form of both particulate and gaseous radioisotopes. , it was the world's largest known release of radioactivity into the environment. ...

.

In 1998, average caesium-137 doses from the accident (estimated at 1–2 mSv per year) did not exceed those from other sources of exposure. Current effective caesium-137 dose rates as of 2019 are 200–250 nSv/h, or roughly 1.7–2.2 mSv per year,

which is comparable to the worldwide average background radiation

Background radiation is a measure of the level of ionizing radiation present in the environment at a particular location which is not due to deliberate introduction of radiation sources.

Background radiation originates from a variety of source ...

from natural sources.

The base of operations for the administration and monitoring of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was moved from Pripyat to Chernobyl. Chernobyl currently contains offices for the State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management and accommodations for visitors. Apartment blocks have been repurposed as accommodations for employees of the State Agency. The length of time that workers may spend within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is restricted by regulations that have been implemented to limit radiation exposure. Today, visits are allowed to Chernobyl but limited by strict rules.

In 2003, the United Nations Development Programme

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)french: Programme des Nations unies pour le développement, PNUD is a United Nations agency tasked with helping countries eliminate poverty and achieve sustainable economic growth and human dev ...

launched a project, called the Chernobyl Recovery and Development Programme (CRDP)

Chernobyl Recovery and Development Programme (CRDP) is developed by the United Nations Development Programme and aims at ensuring return to normal life as a realistic prospect for people living in regions affected by Chernobyl disaster. The Progra ...

, for the recovery of the affected areas. The main goal of the CRDP's activities is supporting the efforts of the Government of Ukraine

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine ( uk, Кабінет Міністрів України, translit=Kabinet Ministriv Ukrainy; shortened to CabMin), commonly referred to as the Government of Ukraine ( uk, Уряд України, ''Uriad Ukrai ...

to mitigate the long-term social, economic, and ecological consequences of the Chernobyl disaster.

The city has become overgrown and many types of animals live there. According to census information collected over an extended period of time, it is estimated that more mammals live there now than before the disaster.

Notably, Mikhail Gorbachev, the final leader of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, stated in respect to the Chernobyl disaster that, "More than anything else, (Chernobyl) opened the possibility of much greater freedom of expression, to the point that the (Soviet) system as we knew it could no longer continue."

People

*Aaron Twersky of Chernobyl

Aaron Twersky of Chernobyl (1784–1871) was a Ukrainian rabbi. He succeeded his father Rabbi Mordechai Twersky as rebbe of the Chernobler chasidim.

Biography

Aaron Twersky was born in Chernobyl in 1784, the first-born of Rabbi Mordechai Twers ...

(1784–1871), rabbi

* Aleksander Franciszek Chodkiewicz (1776–1838), Polish politician and lithographer

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

*Alexander Krasnoshchyokov

Alexander Mikhailovich Krasnoshchyokov (russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Краснощёков, real name – Avraam Moiseevich Krasnoshchyok, russian: Абра́м Моисе́евич Краснощёк, October 10, 1880 – ...

(1880–1937), politician

*Andriy Smalko

Andriy Oleksiyovych Smalko ( ua, Андрій Олексійович Смалько; born 12 January 1981) is a Ukrainian retired football player.

Career

In 1997, he started his career for Borysfen Boryspil, where he stayed for five seasons, an ...

(1981–), football player

*Arnold Lakhovsky

Arnold Borisovich Lakhovsky ( uk, Арнольд Борисович Лаховський, russian: link=no, Арнольд Борисович Лаховский, also known as Aaron Berkovich; born 1880 – 1937) was a painter and sculptor ...

(1880–1937), artist

*Jan Mikołaj Chodkiewicz

Count Jan Mikołaj Chodkiewicz (14 December 1738, Gdańsk - 2 February 1781, Chernobyl) was the Starost of Żmudź and Wielona; Count of Szkłów and .

Biography

His father, , was the Voivode of Brest-Litovsk. In 1757, after completing his stud ...

(1738–1781), Polish nobleman, father of Rozalia Lubomirska

* Ekaterina Scherbachenko (1977–), opera singer

* Grigory Irmovich Novak (1919–1980), Jewish Soviet weightlifter

*Joshua ben Aaron Zeitlin Joshua ben Aaron Zeitlin (October 10, 1823, in Kiev – January 11, 1888, in Dresden), was a Jewish and Russian scholar and philanthropist.

While he was still young his parents removed to Chernobyl, where he associated with the Chasidim, later ...

(1823–1888), scholar and philanthropist

* Markiyan Kamysh (1988–), novelist and son of a liquidator

*Rozalia Lubomirska

Rozalia Lubomirska (16 September 1768 in Chernobyl – 29 June 1794 in Paris) was a Polish noblewoman, most noted for her death.

Life

Born Countess Rozalia Chodkiewicz, she was the daughter of Count Jan Mikołaj Chodkiewicz and Countess Maria ...

(1768–1794), Polish noblewoman guillotined during the French Revolution

*Volodymyr Pravyk

Volodymyr Pavlovych Pravyk ( uk, Володимир Павлович Правик, russian: Владимир Павлович Правик, translit=Vladimir Pravik; 13 June 1962 – 11 May 1986) was a Soviet firefighter notable for his role ...

(1962–1986), firefighter and liquidator

Climate

Chernobyl has ahumid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freez ...

(Dfb DFB may refer to:

* Deerfield Beach, Florida, a city

* Decafluorobutane, a fluorocarbon gas

* Dem Franchize Boyz, former hip hop group, Atlanta, Georgia

* Dfb, Köppen climate classification for Humid continental climate

* Distributed-feedback las ...

) with very warm, wet summers with cool nights and long, cold, and snowy winters.

See also

*List of Chernobyl-related articles

This is a list of Chernobyl-related articles.

Disaster and effects

* Comparison of Chernobyl and other radioactivity releases

** Comparison of the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear accidents

* Chernobyl disaster

* Effects of the Chernobyl dis ...

References

External links

State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management

– official information on public works, zone status, visits, etc.

– State Agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone Management

Online map

Chernobyl

– History of Jewish Communities in Ukraine ''JewUa.org''

The Chernobyl Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chernobyl (City) 1193 establishments in Europe 12th-century establishments in Ukraine * Cities in Kyiv Oblast Cities of district significance in Ukraine Cossack Hetmanate Environmental disaster ghost towns Ghost towns in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone Holocaust locations in Ukraine Radomyslsky Uyezd Kiev Voivodeship Historic Jewish communities in Poland Jewish Ukrainian history Rus' settlements Shtetls