Charles X Of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

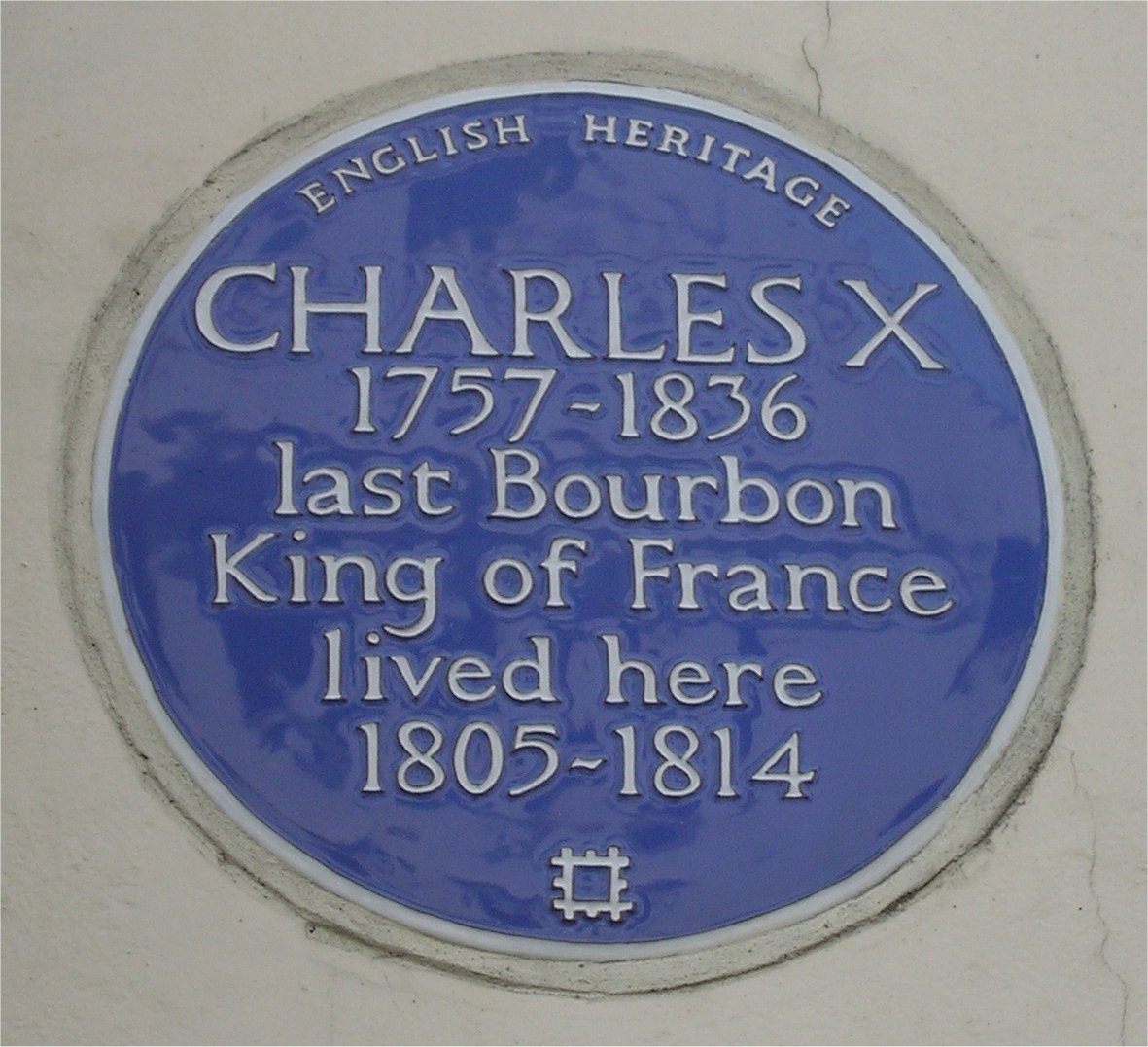

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces in

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces in

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such as Jules de Polignac, the writer

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such as Jules de Polignac, the writer

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold general elections, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.

The elections of 23 June did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of emergency. On 25 July, at the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, Charles issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold general elections, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.

The elections of 23 June did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of emergency. On 25 July, at the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, Charles issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August, embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamers provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, that they needed to arrive in Britain as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonyms; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the British, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tricolour flags at them.Nagel, pp. 318–325.

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be repaid in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle in Dorset, but quickly moved to

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August, embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamers provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, that they needed to arrive in Britain as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonyms; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the British, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tricolour flags at them.Nagel, pp. 318–325.

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be repaid in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle in Dorset, but quickly moved to

King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII

Louis XVII (born Louis Charles, Duke of Normandy; 27 March 1785 – 8 June 1795) was the younger son of King Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette. His older brother, Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France, died in June 1789, a little over ...

and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

and Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

, he supported the latter in exile. After the Bourbon Restoration in 1814, Charles (as heir-presumptive) became the leader of the ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (, collectively Ultras) were a Politics of France, French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who str ...

s, a radical monarchist faction within the French court that affirmed absolute monarchy by divine right and opposed the constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

concessions towards liberals and the guarantees of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

granted by the Charter of 1814. Charles gained influence within the French court after the assassination of his son Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, in 1820 and succeeded his brother Louis XVIII in 1824.

Charles's reign of almost six years proved to be deeply unpopular amongst the liberals in France from the moment of his coronation in 1825, in which he tried to revive the practice of the royal touch. The governments appointed under his reign reimbursed former landowners for the abolition of feudalism at the expense of bondholders, increased the power of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, and reimposed capital punishment for sacrilege

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object, site or person. This can take the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things. When the sacrilegious offence is verbal, it is called blasphemy, and when physical ...

, leading to conflict with the liberal-majority Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

. Charles also approved the French conquest of Algeria as a way to distract his citizens from domestic problems, and forced Haiti to pay a hefty indemnity in return for lifting a blockade and recognizing Haiti's independence. He eventually appointed a conservative government under the premiership of Prince Jules de Polignac, who was defeated in the 1830 French legislative election. He responded with the July Ordinances disbanding the Chamber of Deputies, limiting franchise, and reimposing press censorship. Within a week Paris faced urban riots which led to the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Cha ...

of 1830, which resulted in his abdication and the election of Louis Philippe I

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

as King of the French. Exiled once again, Charles died in 1836 in Gorizia

Gorizia (; ; , ; ; ) is a town and (municipality) in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It is the capital of the Province of Gorizia, Region ...

, then part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. He was the last of the French rulers from the senior branch of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

.

Although extinct in male line after Charles X's grandson Henri died childless fifty years after the king was deposed, the senior branch of the House of Bourbon still exists to this day in the female line through his granddaughter Princess Louise of Artois, Henri's older sister: Louise married her distant relative Charles III of Parma, who came from the Spanish collateral branch of Bourbon-Parma, and was the mother of the last Duke of Parma

The Duke of Parma and Piacenza () was the ruler of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, a List of historic states of Italy, historical state of Northern Italy. It was created by Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese) for his son Pier Luigi Farnese, Du ...

, Robert I. One of Robert's many children, Felix, married Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg and became the grandfather of the current Grand Duke of Luxembourg

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg is the head of state of Luxembourg. Luxembourg has been a grand duchy since 15 March 1815, when it was created from territory of the former Duchy of Luxembourg. It was in personal union with the United Kingdom of ...

, Henri. As a result, Charles X is an ancestor of the House of Luxembourg-Nassau, which currently reigns in Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

.

Childhood and adolescence

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at thePalace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

. Charles was created Count of Artois

The count of Artois (, ) was the ruler over the County of Artois from the 9th century until the abolition of the countship by the French Revolution, French revolutionaries in 1790.

House of Artois

*Odalric ()

*Altmar ()

*Adelelm (?–932)

*''C ...

at birth by his grandfather, the reigning King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

. As the youngest male in the family, Charles seemed unlikely ever to become king. His eldest brother, Louis, Duke of Burgundy, died unexpectedly in 1761, which moved Charles up one place in the line of succession. He was raised in early childhood by Madame de Marsan, the Governess of the Children of France. At the death of his father in 1765, Charles's oldest surviving brother, Louis Auguste, became the new Dauphin (the heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

to the French throne). Their mother Marie Josèphe, who never recovered from the loss of her husband, died in March 1767 from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. This left Charles an orphan at the age of nine, along with his siblings Louis Auguste, Louis Stanislas, Count of Provence, Clotilde ("Madame Clotilde"), and Élisabeth ("Madame Élisabeth").

Louis XV fell ill on 27 April 1774 and died on 10 May of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

at the age of 64.Antonia Fraser, ''Marie Antoinette: the Journey'', pp. 113–116. His grandson Louis-Auguste succeeded him as King Louis XVI.

Marriage and private life

In November 1773, Charles married Marie Thérèse of Savoy. In 1775, Marie Thérèse gave birth to a boy, Louis Antoine, who was created Duke of Angoulême by Louis XVI. Louis-Antoine was the first of the next generation of Bourbons, as the king and the Count of Provence had not fathered any children yet, causing the Parisian ''libellistes'' (pamphleteer

A pamphleteer is a historical term used to describe someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articu ...

s who published scandalous leaflets about important figures in court and politics) to lampoon Louis XVI's alleged impotence. Three years later, in 1778, Charles' second son, Charles Ferdinand, was born and given the title of Duke of Berry. In the same year Queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

gave birth to her first child, Marie Thérèse, quelling all rumours that she could not bear children.

Charles was thought of as the most attractive member of his family, bearing a strong resemblance to his grandfather Louis XV.Fraser, pp. 80–81. His wife was considered quite ugly by most contemporaries, and he looked for company in numerous extramarital affairs. According to the Count of Hézecques, "few beauties were cruel to him." Among his lovers was notably Anne Victoire Dervieux. Later, he embarked upon a lifelong love affair with the beautiful Louise de Polastron, the sister-in-law of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

's closest companion, the Duchess of Polignac.

Charles also struck up a firm friendship with Marie Antoinette herself, whom he had first met upon her arrival in France in April 1770 when he was twelve. The closeness of the relationship was such that he was falsely accused by Parisian rumour mongers of having seduced her. As part of Marie Antoinette's social set, Charles often appeared opposite her in the private theatre of her favourite royal retreat, the Petit Trianon

The Petit Trianon (; French for 'small Trianon') is a Neoclassical architecture, Neoclassical style château located on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, France. It was built between 1762 and 1768 ...

. They were both said to be very talented amateur actors. Marie Antoinette played milkmaids, shepherd

A shepherd is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations; it exists in many parts of the globe, and it is an important part of Pastoralism, pastoralist animal husbandry. ...

esses, and country ladies, whereas Charles played lovers, valets, and farmers.

A famous story concerning the two involves the construction of the Château de Bagatelle. In 1775, Charles purchased a small hunting lodge in the Bois de Boulogne. He soon had the existing house torn down with plans to rebuild. Marie Antoinette wagered her brother-in-law that the new château could not be completed within three months. Charles engaged the neoclassical architect François-Joseph Bélanger to design the building.Fraser, p. 178.

He won his bet, with Bélanger completing the house in sixty-three days. It is estimated that the project, which came to include manicured gardens, cost over two million livres. Throughout the 1770s, Charles spent lavishly. He accumulated enormous debts, totalling 21 million livres. In the 1780s, King Louis XVI paid off the debts of both his brothers, the Counts of Provence and Artois.

In March 1778, Charles caused a scandal when he assaulted the Duchess of Bourbon, Bathilde d'Orléans, at a masked ball, while "escorting adameCanillac, a lady of the town ..After exchanging a few words, the irritated Duchess reached up and snatched off his mask whereupon he pulled her nose so hard and painfully that she wept." Her husband, Louis Henri, Prince of Condé, challenged him to a duel, during which Charles was wounded in the hand. When the Bourbons later attended a play, they were received with "enthusiastic cheers", although the two men were reconciled the next year. This affair became known as: An Incident at the Opera Ball on Mardi Gras in 1778.

In 1781, Charles acted as a proxy for Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Joseph II at the christening of his godson, the Dauphin Louis Joseph.

Crisis and French Revolution

Charles's political awakening started with the first great crisis of the monarchy in 1786, when it became apparent that the kingdom was bankrupt from previous military endeavours (in particular theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

and the American War of Independence) and needed fiscal reform to survive. Charles supported the removal of the aristocracy's financial privileges, but was opposed to any reduction in the social privileges enjoyed by either the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

or the nobility. He believed that France's finances should be reformed without the monarchy being overthrown. In his own words, it was "time for repair, not demolition."

King Louis XVI eventually convened the Estates General, which had not been assembled for over 150 years, to meet in May 1789 to ratify financial reforms. Along with his sister Élisabeth, Charles was the most conservative member of the family and opposed the demands of the Third Estate (representing the commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s) to increase their voting power. This prompted criticism from his brother, who accused him of being "plus royaliste que le roi" ("more royalist than the king"). In June 1789, the representatives of the Third Estate declared themselves a National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

intent on providing France with a new constitution.

In conjunction with the Baron de Breteuil, Charles had political alliances arranged to depose the liberal minister of finance, Jacques Necker. These plans backfired when Charles attempted to secure Necker's dismissal on 11 July without Breteuil's knowledge, much earlier than they had originally intended. It was the beginning of a decline in his political alliance with Breteuil, which ended in mutual loathing.

Necker's dismissal provoked the storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille ( ), which occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, was an act of political violence by revolutionary insurgents who attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison k ...

on 14 July. With the concurrence of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Charles and his family left France three days later, on 17 July, along with several other courtiers. These included the Duchess of Polignac, the queen's favourite. His flight was historically attributed to personal fears for his own safety. However recent research indicates that the King had approved his brother's departure in advance, seeing it as a means of ensuring that one close relative would be free to act as a spokesman for the monarchy, after Louis himself had been moved from Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

to Paris.

Life in exile

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, his wife's native country, where they were joined by some members of the Condé family. Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis XVI was struggling with the National Assembly, which was committed to radical reforms and had enacted the Constitution of 1791. In March 1791, the Assembly also enacted a regency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

bill that provided for the case of the king's premature death. While his heir Louis-Charles was still a minor, the Count of Provence

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

, the Duke of Orléans or, if either was unavailable, someone chosen by election should become regent, completely passing over the rights of Charles who, in the royal lineage, stood between the Count of Provence and the Duke of Orléans.

Charles meanwhile left Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

(in Italy) and moved to Trier

Trier ( , ; ), formerly and traditionally known in English as Trèves ( , ) and Triers (see also Names of Trier in different languages, names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle (river), Moselle in Germany. It lies in a v ...

in Germany, where his uncle, Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony, was the incumbent Archbishop-Elector. Charles prepared for a counter-revolutionary invasion of France, but a letter by Marie Antoinette postponed it until after the royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

had escaped from Paris and joined a concentration of regular troops under François Claude Amour, marquis de Bouillé at Montmédy.

After the attempted flight was stopped at Varennes, Charles moved on to Koblenz

Koblenz ( , , ; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz'') is a German city on the banks of the Rhine (Middle Rhine) and the Moselle, a multinational tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman military p ...

, where he, the recently escaped Count of Provence and the Princes of Condé jointly declared their intention to invade France. The Count of Provence was sending dispatches to various European sovereigns for assistance, while Charles set up a court-in-exile in the Electorate of Trier

The Electorate of Trier ( or '; ) was an Hochstift, ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that existed from the end of the 9th to the early 19th century. It was the temporal possession of the prince-archbishop of Trier (') wh ...

. On 25 August, the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which called on other European powers to intervene in France.

On New Year's Day 1792, the National Assembly declared all emigrants

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

traitors, repudiated their titles and confiscated their lands. This measure was followed by the suspension and eventually the abolition of the monarchy in September 1792. The royal family was imprisoned, and the former king and former queen were eventually executed in 1793. The young former dauphin died of illnesses and neglect in 1795.

When the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

broke out in 1792, Charles escaped to Great Britain, where King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

gave him a generous allowance. Charles lived in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

and London with his mistress Louise de Polastron. His older brother, dubbed Louis XVIII after the death of his nephew in June 1795, relocated to Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

and then to Jelgava Palace, Mitau, where Charles' son Louis Antoine married Louis XVI's only surviving child, Marie Thérèse, on 10 June 1799. In 1802, Charles supported his brother with several thousand pounds. In 1807, Louis XVIII moved to the United Kingdom.

Bourbon Restoration

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces in

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces in southern France

Southern France, also known as the south of France or colloquially in French as , is a geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', Atlas e ...

. Louis XVIII, by then reliant on a wheelchair, supplied Charles with letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

creating him Lieutenant General of the Kingdom of France. On 31 March, the Allies captured Paris. A week later, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

abdicated. The Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

declared the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, with Louis XVIII as King of France. Charles (now heir-presumptive) arrived in the capital on 12 April and acted as Lieutenant General of the realm until Louis XVIII arrived from the United Kingdom. During his brief tenure as regent, Charles created an ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (, collectively Ultras) were a Politics of France, French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who str ...

secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

that reported directly back to him without Louis XVIII's knowledge. It operated for over five years.

Louis XVIII was greeted with great rejoicing from the Parisians and proceeded to occupy the Tuileries Palace.Nagel, pp. 253–254. The Count of Artois lived in the ''Pavillon de Mars'', and the Duke of Angoulême in the '' Pavillon de Flore'', which overlooked the River Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

. The Duchess of Angoulême fainted upon arriving at the palace, as it brought back terrible memories of her family's incarceration there, and of the storming of the palace and the massacre of the Swiss Guards on 10 August 1792.

Following the advice of the occupying allied army, Louis XVIII promulgated a liberal constitution, the Charter of 1814, which provided for a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate Deliberative assembly, assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate ...

legislature, an electorate of 90,000 men and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

.

After the Hundred Days, Napoleon's brief return to power in 1815, the White Terror focused mainly on the purging of a civilian administration which had almost completely turned against the Bourbon monarchy. About 70,000 officials were dismissed from their positions. The remnants of the Napoleonic army were disbanded after the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

and its senior officers cashiered. Marshal Ney was executed for treason, and Marshal Brune was murdered by a crowd. Approximately 6,000 individuals who had rallied to Napoleon were brought to trial. There were about 300 mob lynchings in southern France, notably in Marseille where a number of Napoleon's Mamluks preparing to return to Egypt, were massacred in their barracks.

King's brother and heir presumptive

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such as Jules de Polignac, the writer

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such as Jules de Polignac, the writer François-René de Chateaubriand

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand (4 September 1768 – 4 July 1848) was a French writer, politician, diplomat and historian who influenced French literature of the nineteenth century. Descended from an old aristocratic family from Bri ...

and Jean-Baptiste de Villèle. On several occasions, Charles voiced his disapproval of his brother's liberal ministers and threatened to leave the country unless Louis XVIII dismissed them. Louis, in turn, feared that his brother's and heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

's ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (, collectively Ultras) were a Politics of France, French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who str ...

tendencies would send the family into exile once more (which they eventually did).

On 14 February 1820, Charles's younger son, the Duke of Berry, was assassinated at the Paris Opera

The Paris Opera ( ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be kn ...

. This loss not only plunged the family into grief but also put the succession in jeopardy, as Charles's elder son, the Duke of Angoulême, was childless. The lack of male heirs in the Bourbon main line raised the prospect of the throne passing to the Duke of Orléans and his heirs, which horrified the more conservative ultras. Parliament debated the abolition of the Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

, which excluded females from the succession and was long held inviolable. However, the Duke of Berry's widow, Caroline of Naples and Sicily, was found to be pregnant and on 29 September 1820 gave birth to a son, Henry, Duke of Bordeaux. His birth was hailed as "God-given", and the people of France purchased for him the Château de Chambord in celebration of his birth. As a result, his granduncle, Louis XVIII, added the title Count of Chambord, hence Henri, Count of Chambord, the name by which he is usually known.

Reign

Ascension and Coronation

Charles' brother King Louis XVIII's health had been worsening since the beginning of 1824. Having both dry and wet gangrene in his legs and spine, he died on 16 September of that year, aged almost 69. Charles, by now aged 66, succeeded him to the throne as King Charles X. On 29 May 1825, King Charles was anointed at the cathedral ofReims

Reims ( ; ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French Departments of France, department of Marne (department), Marne, and the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, 12th most populous city in Fran ...

, the traditional site of consecration of French kings; it had been unused since 1775, as Louis XVIII had forgone the ceremony to avoid controversy and because his health was too precarious.Price, pp. 119–121. It was in the venerable cathedral of Notre-Dame at Paris that Napoleon had consecrated his revolutionary empire; but in ascending the throne of his ancestors, Charles reverted to the old place of coronation used by the kings of France from the early ages of the monarchy. The last coronation to be held there was the Coronation of Louis XVI in 1775.

Like the regime of the Restoration itself, the coronation was conceived as a compromise between the monarchical tradition and the Charter of 1814: it took up the main phases of traditional ceremonial such as the seven anointings or the oaths on the Gospels, all by associating with it the oath of fidelity taken by the King to the Charter of 1814 or the participation of the great princes in the ceremonial as assistants of the Archbishop of Reims.

A commission was charged with simplifying and modernizing the ceremony and making it compatible with the principles of the monarchy according to the Charter (deletion of the promises of struggle against heretics and infidels, of the twelve peers, of references to Hebrew royalty, etc.) – it lasted three and a half hours.

In fact, the choice of the coronation was applauded by the royalists in favor of a constitutional and parliamentary monarchy and not only by those nostalgic for the Ancien Régime; the fact that the ceremony was modernized and adapted to new times encouraged Chateaubriand, a non-absolutist royalist and enthusiastic supporter of the Charter of 1814, to invite the king to be crowned. In the brochure

A brochure is an promotional document primarily used to introduce a company, organization, products, or services and inform prospective customers or members of the public of the benefits. Although, initially, a paper document that can be folded ...

''The King is Dead! Long live the king!'' Chateaubriand explains that a coronation would have being the "link in the chain which united the oath of the new monarchy to the oath of the old monarchy"; it is continuity with the Ancien Régime more than its return that the royalists extol, Charles X having inherited the qualities of his ancestors: "pious like Saint Louis, affable, compassionate and vigilant like Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), also known as Louis of Orléans was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples (as Louis III) from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Cleves, he succeeded his second ...

, courteous like Francis I, frank as Henry IV".

The coronation showed that dynastic continuity went hand in hand with political continuity; for Chateaubriand: "The current constitution is only the rejuvenated text of the code of our old franchises".

This coronation took several days: the May 28, vespers ceremony; May 29, ceremony of the coronation itself, chaired by the Archbishop of Reims, Mgr. Jean-Baptiste de Latil, in the presence in particular of Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, and a large audience; May 30, award ceremony for the Knights of the Order of the Holy Spirit and finally, May 31, the Royal touch of scrofula.

The coronation of Charles X therefore appeared to be a compromise between the tradition of the Ancien Régime and the political changes that had taken place since the Revolution. The coronation nevertheless had a limited influence on the population, mentalities no longer being those of yesteryear. From then on, the coronation caused incomprehension in certain sectors of public opinion.

It was Luigi Cherubini who composed the music for the Coronation Mass. For the occasion, the composer Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote man ...

composed the Opera '' Il Viaggio a Reims.''

Domestic policies

Like Napoleon and then Louis XVIII before him, Charles X resided mainly at the Tuileries Palace and, in summer, at the Château de Saint-Cloud, two buildings that no longer exist today. Occasionally he stayed at theChâteau de Compiègne

The Château de Compiègne is a French château, a former royal residence built for Louis XV and later restored by Napoleon. Compiègne was one of three seats of royal government, the others being Versailles and Fontainebleau. It is located i ...

and the Château de Fontainebleau, while the Palace of Versailles, where he was born, remained uninhabited.

The reign of Charles X began with some liberal measures such as the abolition of press censorship, but the king renewed the term of Joseph de Villèlle, president of the council since 1822, and gave the reins of government to the ultraroyalists.

He got closer to the population by the trip he made to the north of France in September 1827, then to the east of France in September 1828. He was accompanied by his eldest son and heir-apparent, the Duke of Angoulême, now Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' is French for dolphin and ...

.

In his first act as king, Charles attempted to bring comity to the House of Bourbon by granting the style of Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Kings and their female consorts, as well as queens regnant, are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of a ...

to his cousins of the House of Orléans, a title denied by Louis XVIII because of the former Duke of Orléans' vote for the death of Louis XVI.

Charles gave his prime minister, Villèlle lists of laws to be ratified in each parliament. In April 1825, the government approved legislation originally proposed by Louis XVIII to pay an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

(the '' biens nationaux'') to nobles whose estates had been confiscated during the Revolution. The law gave approximately 988 million francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' ( King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centur ...

worth of government bonds to those who had lost their lands, in exchange for their renunciation of their ownership. In the same month, the Anti-Sacrilege Act was passed. Charles's government attempted to re-establish male-only primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

for families paying over 300 francs in tax, but this was voted down in the Chamber of Deputies.Price, pp. 116–118.

That Charles was not a popular ruler in the mostly-liberal minded urban Paris became apparent in April 1827, when chaos ensued during the king's review of the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

in Paris. In retaliation, the National Guard was disbanded but, as its members were not disarmed, it remained a potential threat. After losing his parliamentary majority in a general election in November 1827, Charles dismissed Prime Minister Villèle on 5 January 1828 and appointed Jean-Baptise de Martignac, a man the king disliked and thought of only as provisional. On 5 August 1829, Charles dismissed Martignac and appointed Jules de Polignac, who, however, lost his majority in parliament at the end of August, when the Chateaubriand faction defected. Regardless, Polignac retained power and refused to recall the Chambers until March 1830.Price, pp. 122–128.

Conquest of Algeria

On 31 January 1830, the Polignac government decided to send a military expedition to Algeria to end the threat of Algerian pirates toMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

trade, hoping also to increase his government's popularity through a military victory. The pretext for the war was an outrage by the Viceroy of Algeria, who had struck the French consul with the handle of his fly swat in a rage over French failure to pay debts from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt. French troops occupied Algiers on 5 July.Price, pp. 136–138.

July Revolution

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold general elections, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.

The elections of 23 June did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of emergency. On 25 July, at the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, Charles issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold general elections, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.

The elections of 23 June did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of emergency. On 25 July, at the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, Charles issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the electoral system

An electoral or voting system is a set of rules used to determine the results of an election. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, nonprofit organizations and inf ...

, and called for elections under the new system in September.

The Ordinances were intended to quell the popular discontent but had the opposite effect. Journalists gathered in protest at the headquarters of the '' National'' daily, founded in January 1830 by Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( ; ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian who served as President of France from 1871 to 1873. He was the second elected president and the first of the Third French Republic.

Thi ...

, Armand Carrel, and others. On Monday, 26 July, the government newspaper '' Le Moniteur Universel'' published the ordinances, and Thiers published a call to revolt signed by forty-three journalists:

"The legal regime has been interrupted: that of force has begun... Obedience ceases to be a duty!" In the evening, crowds assembled in the gardens of the Palais-Royal, shouting "Down with the Bourbons!" and "Long live the Charter!". As the police closed off the gardens, the crowd regrouped in a nearby street where they shattered streetlamps.

The next morning of 27 July, police raided and shut down newspapers including '' Le National''. When the protesters, who had re-entered the Palais-Royal gardens, heard of this, they threw stones at the soldiers, prompting them to shoot. By evening, the city was in chaos and shops were looted. On 28 July, the rioters began to erect barricades in the streets. Marshal Marmont, who had been called in the day before to remedy the situation, took the offensive, but some of his men defected to the rioters, and by afternoon he had to retreat to the Tuileries Palace.

The members of the Chamber of Deputies sent a five-man delegation to Marmont, urging him to advise the king to assuage the protesters by revoking the four Ordinances. On Marmont's request, the prime minister applied to the king, but Charles refused all compromise and dismissed his ministers that afternoon, realizing the precariousness of the situation. That evening, the members of the Chamber assembled at Jacques Laffitte's house and elected Louis Philippe d'Orléans to take the throne from King Charles, proclaiming their decision on posters throughout the city. By the end of the day, the authority of Charles' government had evaporated.

A few minutes after midnight on 31 July, warned by General Gresseau that Parisians were planning to attack the Saint-Cloud residence, Charles X decided to seek refuge in Versailles with his family and the court, with the exception of the Duke of Angoulême, who stayed behind with the troops, and the Duchess of Angoulême, who was taking the waters at Vichy. Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis Philippe assumed the post of Lieutenant General of the Kingdom. Charles' road to Versailles was filled with disorganized troops and deserters. The Marquis de Vérac, governor of the Palace of Versailles, came to meet the king before the royal cortège entered the town, to tell him that the palace was not safe, as the Versailles national guards wearing the revolutionary tricolor were occupying the ''Place d'Armes''. Charles then set out for the Trianon at five in the morning. Later that day, after the arrival of the Duke of Angoulême from Saint-Cloud with his troops, Charles ordered a departure for Rambouillet, where they arrived shortly before midnight. On the morning of 1 August, the Duchess of Angoulême, who had rushed from Vichy after learning of events, arrived at Rambouillet.

The following day, 2 August, King Charles X abdicated, bypassing his son the Dauphin in favor of his grandson Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who was not yet ten years old. At first, the Duke of Angoulême (the Dauphin) refused to countersign the document renouncing his rights to the throne of France. According to the Duchess of Maillé, "there was a strong altercation between the father and the son. We could hear their voices in the next room." Finally, after twenty minutes, the Duke of Angoulême reluctantly countersigned his father's declaration:

Louis Philippe ignored the document and on 9 August had himself proclaimed King of the French by the members of the Chamber.

Second exile and death

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August, embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamers provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, that they needed to arrive in Britain as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonyms; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the British, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tricolour flags at them.Nagel, pp. 318–325.

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be repaid in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle in Dorset, but quickly moved to

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August, embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamers provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, that they needed to arrive in Britain as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonyms; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the British, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tricolour flags at them.Nagel, pp. 318–325.

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be repaid in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle in Dorset, but quickly moved to Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly known as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood has s ...

in Edinburgh, near the Duchess of Berry at Regent Terrace.

Charles' relationship with his daughter-in-law proved uneasy, as the Duchess declared herself regent for her son Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who was now the legitimist pretender to the French throne. Charles at first denied her this role, but in December agreed to support her claimNagel, pp. 327–328. once she had landed in France. In 1831 the Duchess made her way from Britain by way of the Netherlands, Prussia and Austria to her family in Naples.

Having gained little support, she arrived in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

in April 1832, and made her way to the Vendée

Vendée () is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442. He was further dismayed when after her release the Duchess married the Count of Lucchesi Palli, a minor Neapolitan noble. In response to this morganatic match, Charles banned her from seeing her children.

At the invitation of Emperor Francis I of Austria, the Bourbons moved to

The King Charles Pub in

The King Charles Pub in

p. 53

/ref>

online free

* Artz, Frederick B. ''Reaction and Revolution 1814–1832'' (1938), covers Europe

online

* Brown, Bradford C. "France, 1830 Revolution." in by Immanuel Ness, ed., ''The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest'' (2009): 1–8. * Frederking, Bettina. "'Il ne faut pas être le roi de deux peuples': strategies of national reconciliation in Restoration France." ''French History'' 22.4 (2008): 446–468. in English * Rader, Daniel L. ''The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830'' (Springer, 2013). * Weiner, Margery. ''The French Exiles, 1789–1815'' (Morrow, 1961). * Wolf, John B. ''France 1814–1919: the Rise of a Liberal Democratic Society'' (1940) pp 1–58.

Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

in winter 1832/33 and were given lodging at the Hradschin Palace. In September 1833, Bourbon legitimists gathered in Prague to celebrate the Duke of Bordeaux's thirteenth birthday. They expected grand celebrations, but Charles X merely proclaimed his grandson's majority.Nagel, pp. 340–342.

On the same day, after much cajoling by Chateaubriand, Charles agreed to a meeting with his daughter-in-law, which took place in Leoben

Leoben () is a Styrian city in central Austria, located on the Mur River, Mur river. With a population in 2023 of about 25,140 it is a local industrial centre and hosts the University of Leoben, which specialises in mining. The Peace of Leoben, ...

on 13 October 1833. The children of the Duchess refused to meet her after they learned of her second marriage. Charles refused the Duchess' demands, but after protests from his other daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Angoulême, he acquiesced. In the summer of 1834, he again allowed the Duchess of Berry to see her children.

Upon the death of the Austrian emperor Francis in March 1835, the Bourbons left Prague Castle, as the new emperor Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "courage" or "ready, prepared" related to Old High German "to risk, ventu ...

wished to use it for coronation ceremonies. The Bourbons moved initially to Teplitz. Then, as Ferdinand continued his use of Prague Castle, Kirchberg Castle was purchased for them. Moving there was postponed due to an outbreak of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

in the locality.Nagel, pp. 349–350.

In the meantime, Charles left for the warmer climate on Austria's Mediterranean coast in October 1835. Upon his arrival at Görz (Gorizia) in the Kingdom of Illyria, he caught cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and died on 6 November 1836. The townspeople draped their windows in black mourning. Charles was interred in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady, in the Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

Kostanjevica Monastery (now in Nova Gorica

Nova Gorica () is a town in western Slovenia, on the border with Italy. It is the seat of the Municipality of Nova Gorica. Nova Gorica is a planned town, built according to the principles of modernist architecture after 1947, when the Treaty of pe ...

, Slovenia), where his remains lie in a crypt with those of his family. He is the only King of France to be buried outside the country.

A movement reportedly began in 2016 advocating for Charles X's remains to be buried along with other French monarchs in the Basilica of St Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and archite ...

, although Louis Alphonse, current head of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

, stated in 2017 that he wished the remains of his ancestors to lie undisturbed.

Legacy

The King Charles Pub in

The King Charles Pub in Poole

Poole () is a coastal town and seaport on the south coast of England in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area in Dorset, England. The town is east of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east ...

was renamed after Charles in 1830.

Honours

*Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

:

** Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit, ''1 January 1771''

** Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

, ''3 July 1816''

** Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Louis, ''10 July 1816''

** Grand Master and Knight of the Order of St. Michael

** Grand Master and Grand Cross of the Order of St. Lazarus

** Décoration de la Fidélité

** Decoration of The Lily

* : Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, ''1825''

* : Knight of the Order of the Elephant

The Order of the Elephant () is a Denmark, Danish order of chivalry and is Denmark's highest-ranked honour. It has origins in the 15th century, but has officially existed since 1693, and since the establishment of constitutional monarchy in ...

, ''2 October 1824''

* : Grand Cross of the Military William Order, ''13 May 1825''

* Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, ''4 October 1824''

* :

** Knight of the Order of St. Andrew, ''June 1815''

** Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, ''June 1815''

* : Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, ''1827''

* Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece (, ) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in 1430 in Brugge by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, to celebrate his marriage to Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy, Isabella of Portugal. T ...

, ''6 October 1761''

* :

** Knight of the Order of St. Januarius

** Grand Cross of the Order of St. Ferdinand and Merit

* : Stranger Knight of the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

, ''9 March 1825''Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) ''The Knights of England'', I, Londonp. 53

/ref>

Ancestry

Marriage and issue

Charles X married Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy, the daughter of Victor Amadeus III, King of Sardinia, and Maria Antonietta of Spain, on 16 November 1773. The couple had four children – two sons and two daughters – but the daughters did not survive childhood. Only the oldest son survived his father. The children were: # Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême (6 August 1775 – 3 June 1844), sometimes called Louis XIX. Married first cousin Marie Thérèse of France, no issue. # Sophie, Mademoiselle d'Artois (5 August 1776 – 5 December 1783), died in childhood. # Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry (24 January 1778 – 13 February 1820), married Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile, had issue. # Marie Thérèse, Mademoiselle d'Angoulême (6 January 1783 – 22 June 1783), died in childhood.In fiction and film

The Count of Artois is portrayed by Al Weaver inSofia Coppola

Sofia Carmina Coppola ( , ; born May 14, 1971) is an American filmmaker and former actress. She has List of awards and nominations received by Sofia Coppola, won an Academy Awards, Academy Award, two Golden Globe Awards, a Golden Lion, and a Can ...

's motion picture ''Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

''.

Notes

References

Further reading

* Artz, Frederick Binkerd. ''France Under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814–1830'' (1931)online free

* Artz, Frederick B. ''Reaction and Revolution 1814–1832'' (1938), covers Europe

online

* Brown, Bradford C. "France, 1830 Revolution." in by Immanuel Ness, ed., ''The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest'' (2009): 1–8. * Frederking, Bettina. "'Il ne faut pas être le roi de deux peuples': strategies of national reconciliation in Restoration France." ''French History'' 22.4 (2008): 446–468. in English * Rader, Daniel L. ''The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830'' (Springer, 2013). * Weiner, Margery. ''The French Exiles, 1789–1815'' (Morrow, 1961). * Wolf, John B. ''France 1814–1919: the Rise of a Liberal Democratic Society'' (1940) pp 1–58.

Historiography

*External links

* * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Charles 10 of France 1757 births 1836 deaths Royalty from Versailles 18th-century French people 19th-century monarchs of France 19th-century princes of Andorra 19th-century regents People of the Bourbon Restoration Kings of France French Roman Catholics People of the French Revolution Monarchs who abdicated Dukes of Berry Counts of Artois French counter-revolutionaries Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Dethroned monarchs Princes of France (Bourbon) Burials at Kostanjevica Monastery Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William Heirs presumptive to the French throne Deaths from cholera 18th-century peers of France Members of the Chamber of Peers of the Bourbon Restoration Navarrese titular monarchs Legitimist pretenders to the French throne Dukes of Mercœur French Ultra-royalists French expatriates in Austria French expatriates in Italy French expatriates in Germany Expatriates in the Holy Roman Empire French expatriates in the United Kingdom French generals People of the French conquest of Algeria