Charles Vacquerie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

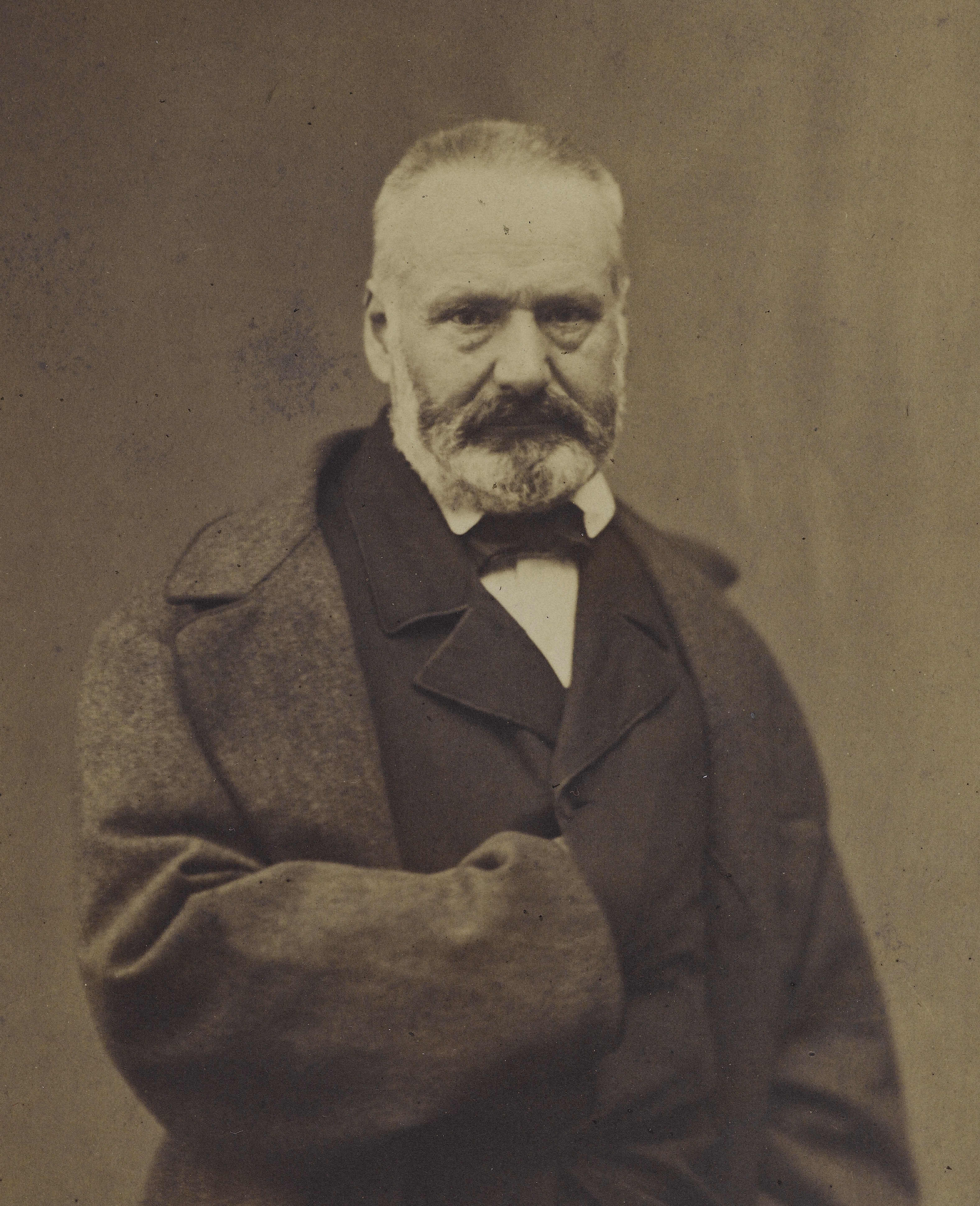

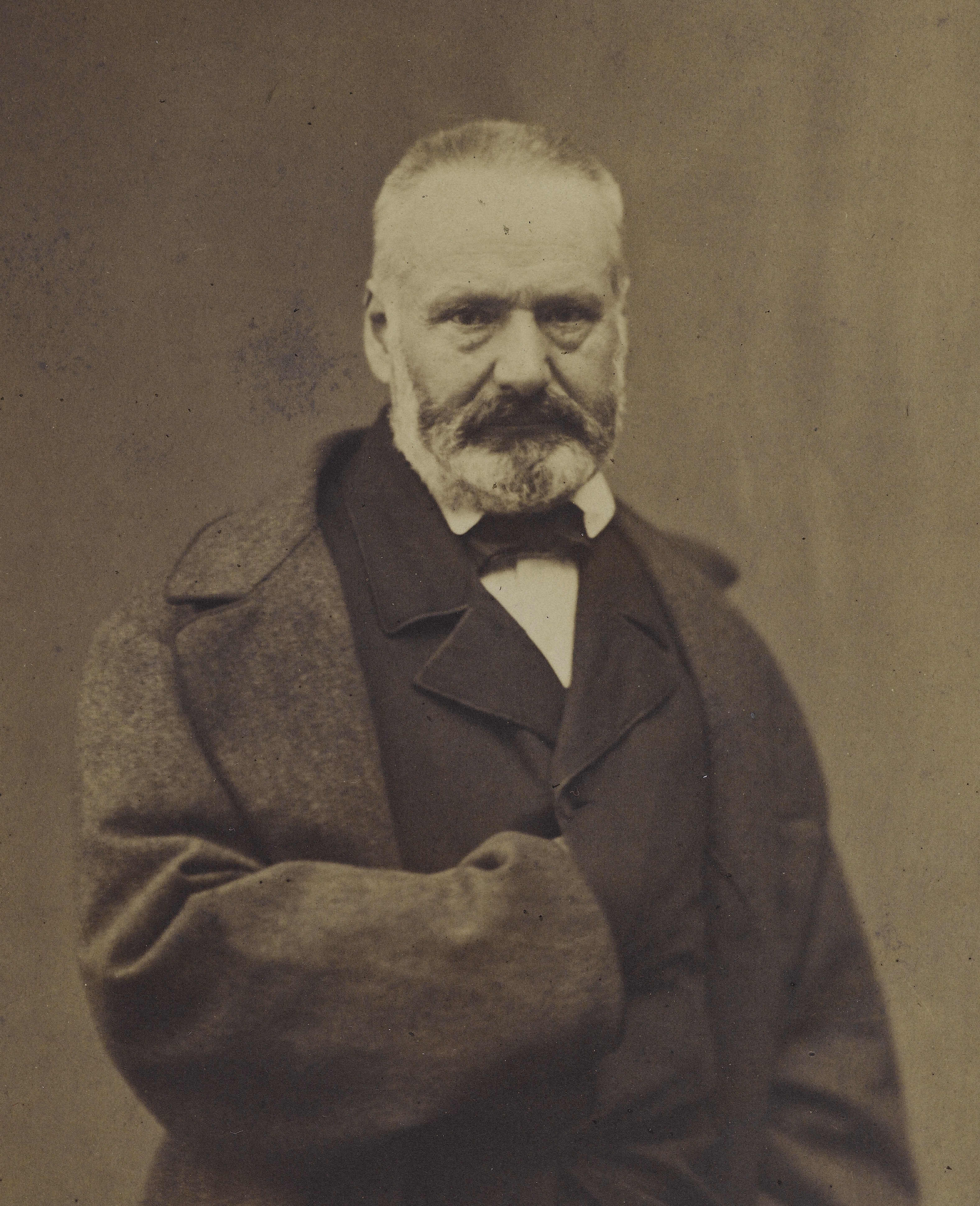

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: "I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing." In 1817, he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: "I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing." In 1817, he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the

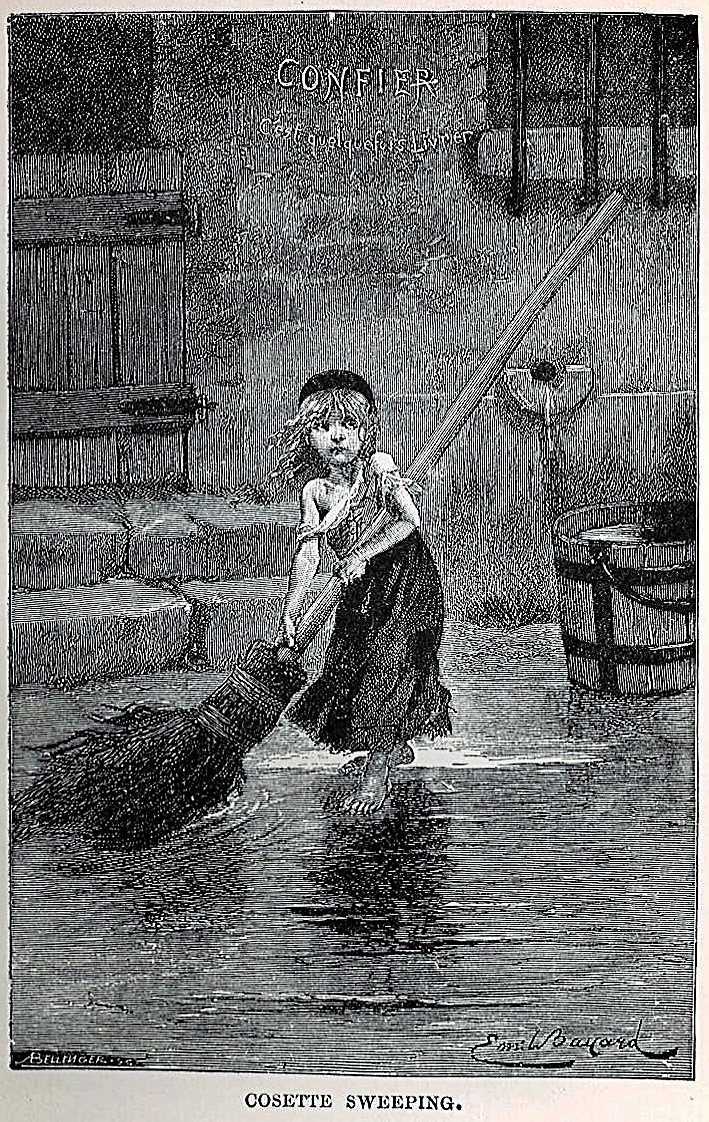

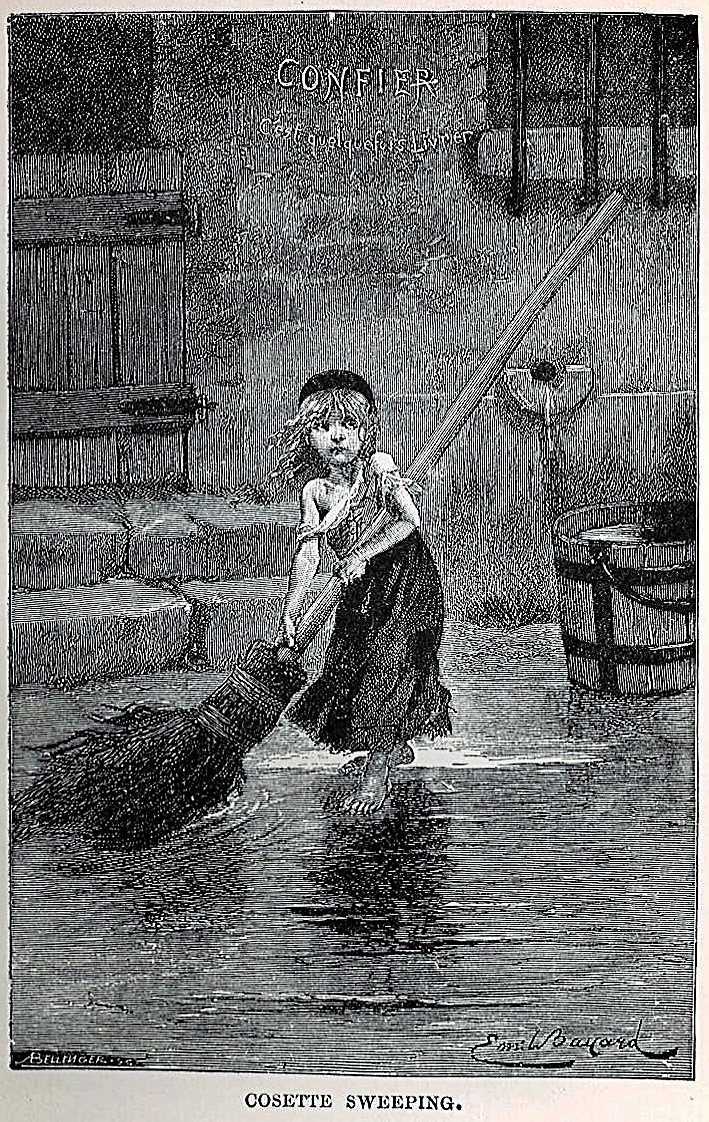

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; found it insincere, complained of its vulgarity, found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the brothers lambasted its artificiality, and —despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers—castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". However, ''Les Misérables'' proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; found it insincere, complained of its vulgarity, found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the brothers lambasted its artificiality, and —despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers—castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". However, ''Les Misérables'' proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. A group of French academicians, particularly , were fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election. Thereafter, he became increasingly involved in French politics.

On the nomination of King , Hugo entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament as a in 1845, where he spoke against the

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. A group of French academicians, particularly , were fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election. Thereafter, he became increasingly involved in French politics.

On the nomination of King , Hugo entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament as a in 1845, where he spoke against the  When Louis Napoleon (

When Louis Napoleon ( After coming in contact with

After coming in contact with  During the

During the

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He was confident that he would be offered the dictatorship, as shown by the notes he kept at the time: "Dictatorship is a crime. This is a crime I am going to commit," but he felt he had to assume that responsibility. Despite his popularity, Hugo lost his bid for re-election to the National Assembly in 1872.

Throughout his life Hugo kept believing in unstoppable humanistic progress. In his last public address on 3 August 1879 he prophesied, in an over-optimistic way, "In the twentieth century war will be dead, the scaffold will be dead, hatred will be dead, frontier boundaries will be dead, dogmas will be dead; man will live."

Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle was interned in an

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He was confident that he would be offered the dictatorship, as shown by the notes he kept at the time: "Dictatorship is a crime. This is a crime I am going to commit," but he felt he had to assume that responsibility. Despite his popularity, Hugo lost his bid for re-election to the National Assembly in 1872.

Throughout his life Hugo kept believing in unstoppable humanistic progress. In his last public address on 3 August 1879 he prophesied, in an over-optimistic way, "In the twentieth century war will be dead, the scaffold will be dead, hatred will be dead, frontier boundaries will be dead, dogmas will be dead; man will live."

Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle was interned in an

From February 1833 until her death in 1883,

From February 1833 until her death in 1883,

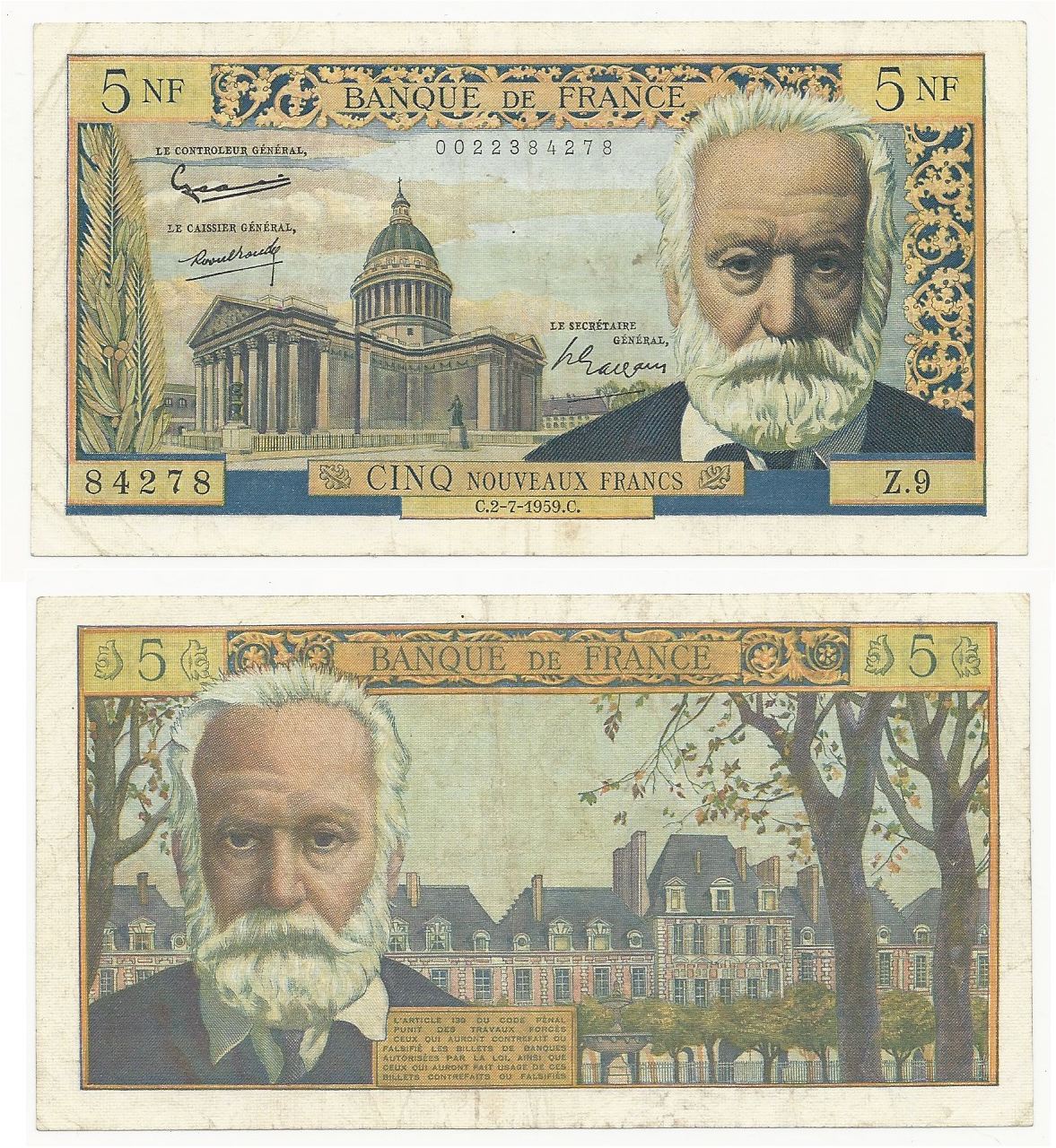

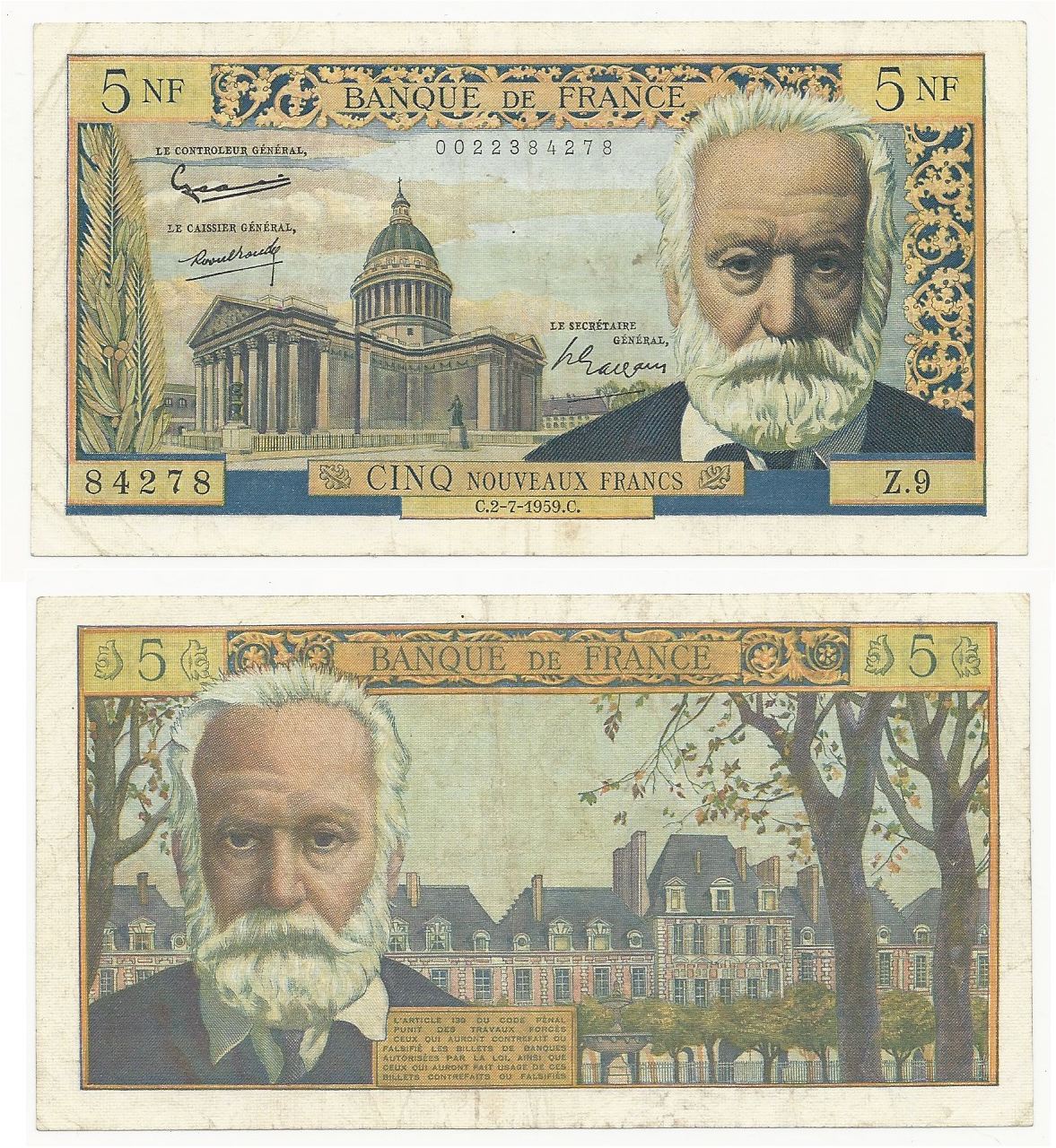

His legacy has been honored in many ways, including his portrait being placed on French currency.

The people of

His legacy has been honored in many ways, including his portrait being placed on French currency.

The people of  In the city of

In the city of

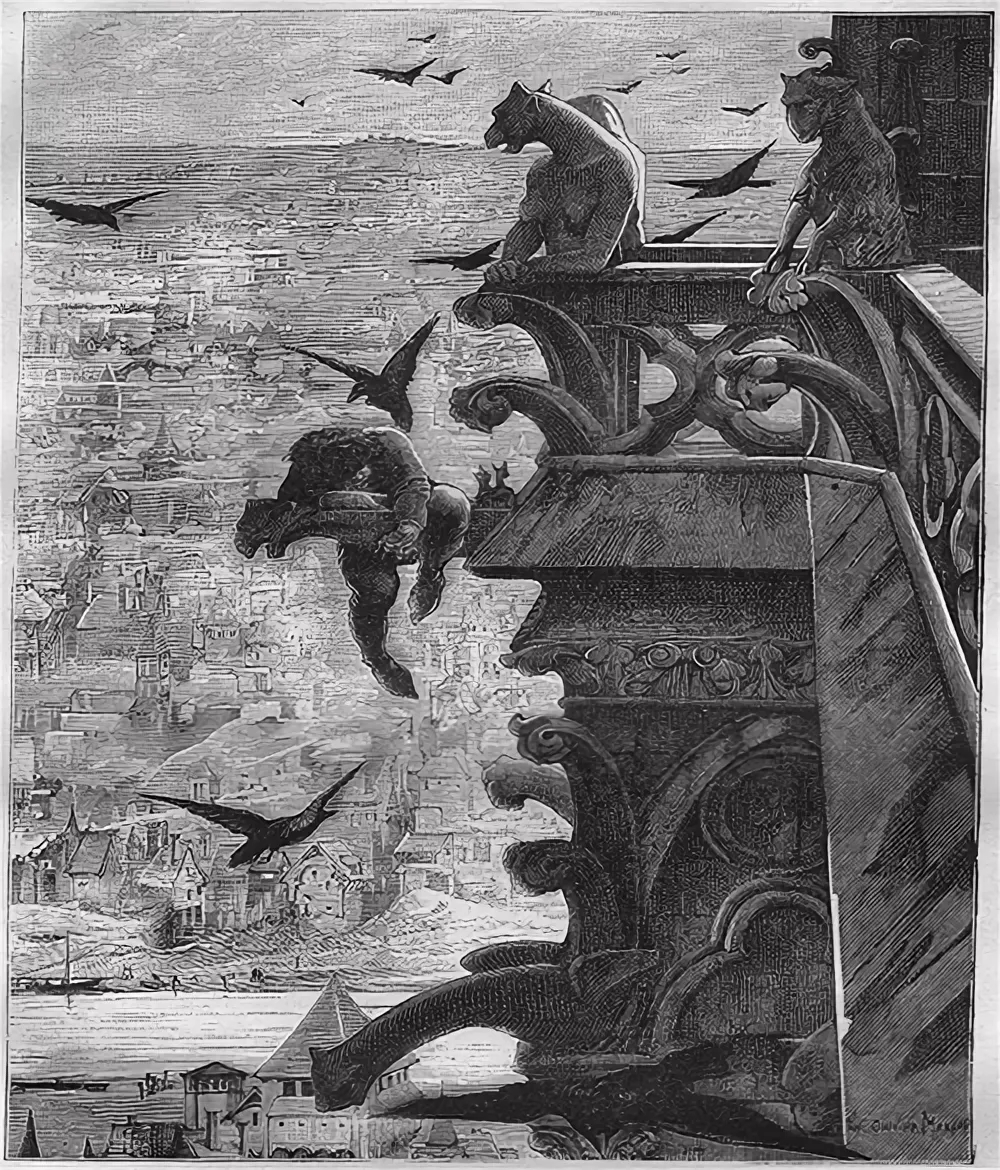

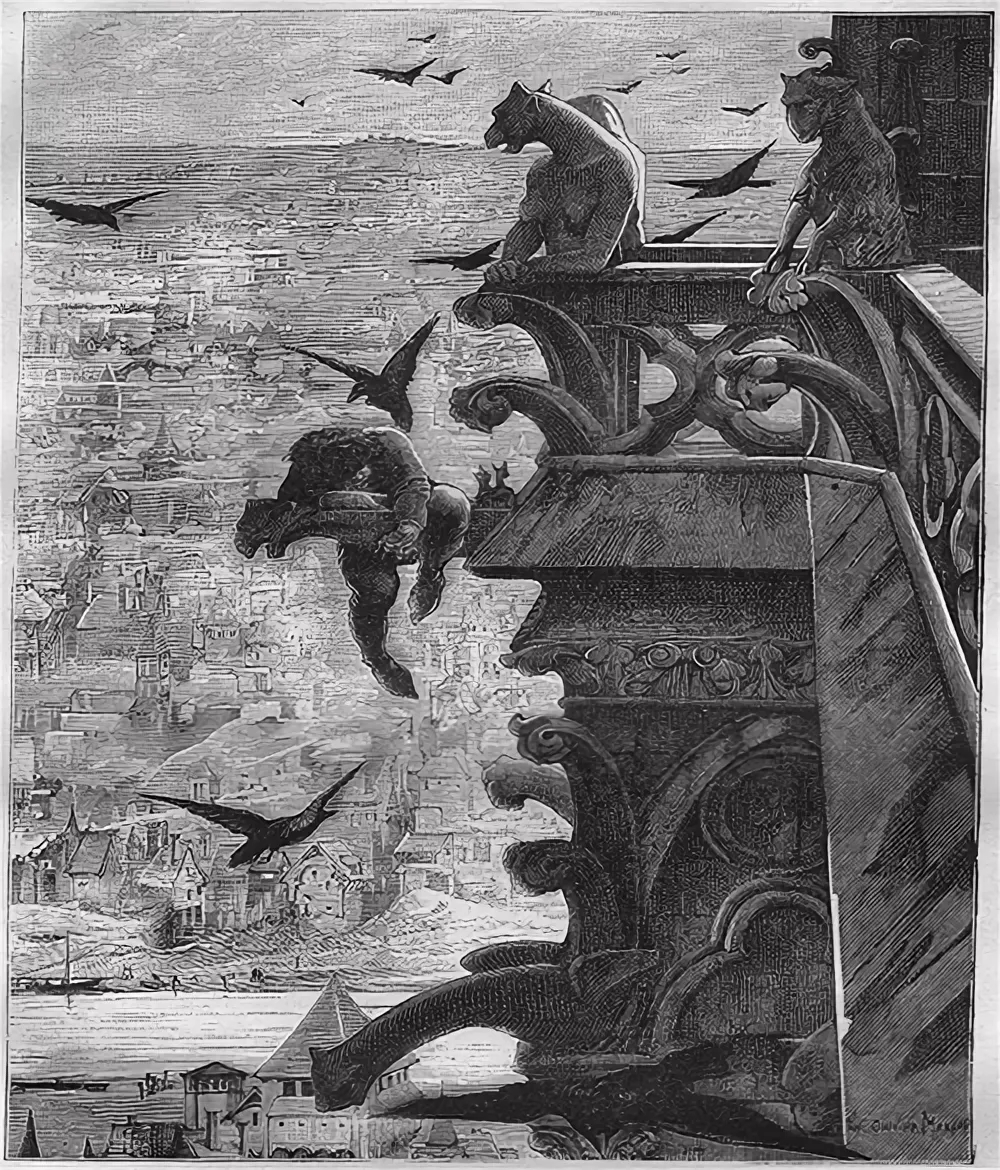

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (, originally titled ''Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482'') is a French Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The title refers to the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which features prominently throughout the novel. I ...

'' (1831) and ''Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' (, ) is a 19th-century French literature, French Epic (genre), epic historical fiction, historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published on 31 March 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century. '' ...

'' (1862). In France, Hugo is renowned for his poetry collections, such as and (''The Legend of the Ages''). Hugo was at the forefront of the Romantic literary movement with his play ''Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially a ...

'' and drama '' Hernani''. His works have inspired music, both during his lifetime and after his death, including the opera ''Rigoletto

''Rigoletto'' is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi. The Italian libretto was written by Francesco Maria Piave based on the 1832 play '' Le roi s'amuse'' by Victor Hugo. Despite serious initial problems with the Austrian censors who had c ...

'' and the musicals ''Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' (, ) is a 19th-century French literature, French Epic (genre), epic historical fiction, historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published on 31 March 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century. '' ...

'' and ''Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Medieval architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissemen ...

''. He produced more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime, and campaigned for social causes such as the abolition of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

and slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

.

Although he was a committed royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

when young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed, and he became a passionate supporter of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, serving in politics as both deputy and senator. His work touched upon most of the political and social issues and the artistic trends of his time. His opposition to absolutism, and his literary stature, established him as a national hero. Hugo died on 22 May 1885, aged 83. He was given a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

in the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, which was attended by over two million people, the largest in French history.

Early life

Victor-Marie Hugo was born on 26 February 1802 (7Ventôse

Ventôse (; also ''Ventose'') was the sixth month in the French Republican Calendar. The month was named after the Latin word ''ventosus'' 'windy'.

Ventôse was the third month of the winter quarter (''mois d'hiver''). It started between 19 an ...

, year X of the Republic) in in Eastern France. He was the youngest son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo

Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo, Count Hugo de Cogolludo y Sigüenza (; 15 November 1773 – 29 January 1828) was a French general in the Napoleonic Wars. He was the husband of Sophie Trébuchet and the father of four sons. He is best known f ...

, a general in the Napoleonic army

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, and Sophie Trébuchet

Sophie Françoise Trébuchet (19 June 1772 in Nantes – 27 June 1821 in Paris) was a French painter and the mother of Victor Hugo.

Early life

Sophie Françoise Trébuchet was born on June 19, 1772, in Nantes, rue des Carmélites, the fourth of e ...

. The couple had two other sons: Abel Joseph and . The Hugo family came from Nancy in Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

, where Hugo's grandfather was a wood merchant. Léopold enlisted in the army of Revolutionary France at fourteen. He was an atheist and an ardent supporter of the Republic. Hugo's mother Sophie was loyal to the deposed dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

but would declare her children to be Protestants. They met in Châteaubriant

Châteaubriant (; ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Châtiaoberiant'') is a town in western France, about southwest of Paris, and one of the three Subprefectures in France, sous-préfectures of the Loire-Atlantique departments of France, department. C ...

in 1796 and married the following year.

Since Hugo's father was an officer in Napoleon's army, the family moved frequently from posting to posting. Léopold Hugo wrote to his son that he had been conceived on one of the highest peaks in the Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; ; Franconian (linguistics), Franconian and ) is a range of medium mountains in Eastern France, near its France–Germany border, border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the bor ...

, on a journey from Lunéville to Besançon. "This elevated origin," he went on, "seems to have had effects on you so that your muse is now continually sublime." Hugo believed himself to have been conceived on 24 June 1801, which is the origin of Jean Valjean

Jean Valjean () is the protagonist of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel ''Les Misérables''. The story depicts the character's struggle to lead a normal life and redeem himself after serving a 19-year-long prison sentence for stealing bread to feed his ...

's prisoner number 24601.

In 1810, Hugo's father was made Count Hugo de Cogolludo y Sigüenza by then King of Spain Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the Napoleonic Wars, the latter made him King of Naples (1806–1808), an ...

, though it seems that the Spanish title was not legally recognized in France. Hugo later titled himself as a viscount, and it was as "Vicomte Victor Hugo" that he was appointed a peer of France

The Peerage of France () was a hereditary distinction within the French nobility which appeared in 1180 during the Middle Ages.

The prestigious title and position of Peer of France () was held by the greatest, highest-ranking members of the Fr ...

on 13 April 1845.

Weary of the constant moving required by military life, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold and settled in Paris in 1803 with her sons. There, she began seeing General Victor Fanneau de La Horie

Victor Claude Alexandre Fanneau de La Horie (Javron-les-Chapelles; 5 January 1766 - Paris; 29 October 1812) was a French general, conspirator against Napoleon, and godfather of Victor Hugo.

Biography

Victor Fanneau de La Horie served the First ...

, Hugo's godfather, who had been a comrade of General Hugo's during the campaign in Vendee. In October 1807, the family rejoined Leopold, now Colonel Hugo, Governor of the province of Avellino

Avellino () is a city and ''comune'', capital of the province of Avellino in the Campania region of southern Italy. It is situated in a plain surrounded by mountains east of Naples and is an important hub on the road from Salerno to Benevento.

...

. There, Hugo was taught mathematics by Giuseppe de Samuele Cagnazzi, elder brother of Italian scientist Luca de Samuele Cagnazzi

Luca de Samuele Cagnazzi (28 October 1764 – 26 September 1852) was an Italian archdeacon, scientist, mathematician, political economist. He also wrote a book about pedagogy and invented the tonograph.

Life

Early years

Luca de Samuele Ca ...

. Sophie found out that Leopold had been living in secret with an Englishwoman called Catherine Thomas.

Soon, Hugo's father was called to Spain to fight the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

. Madame Hugo and her children were sent back to Paris in 1808, where they moved to an old convent, 12 , an isolated mansion in a deserted quarter of the left bank of the Seine. Hiding in a chapel at the back of the garden was de La Horie, who had conspired to restore the Bourbons and been condemned to death a few years earlier. He became a mentor to Hugo and his brothers.

In 1811, the family joined their father in Spain. Hugo and his brothers were sent to school in Madrid at the while Sophie returned to Paris on her own, now officially separated from her husband. In 1812, as the Peninsular War was turning against France, de La Horie was arrested and executed. In February 1815, Hugo and Eugène were taken away from their mother and placed by their father in the Pension Cordier, a private boarding school in Paris, where Hugo and Eugène remained for three years while also attending lectures at Lycée Louis le Grand.

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: "I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing." In 1817, he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: "I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing." In 1817, he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the Academie Française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

, for which he received an honorable mention. The Academicians refused to believe that he was only fifteen. Hugo moved in with his mother to 18 the following year and began attending law school. Hugo fell in love and secretly became engaged, against his mother's wishes, to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher

Adèle Foucher (27 September 1803 – 27 August 1868) was the wife of French writer Victor Hugo, with whom she was acquainted from childhood. Her affair with the critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve became the raw material for Sainte-Beuve's ...

. In June 1821, Sophie Trebuchet died, and Léopold married his long-time mistress Catherine Thomas a month later. Hugo married Adèle the following year. In 1819, Hugo and his brothers began publishing a periodical called .

Career

Hugo published his first novel ('' Hans of Iceland'', 1823) the year following his marriage, and his second three years later ('' Bug-Jargal'', 1826). Between 1829 and 1840, he published five more volumes of poetry:Les Orientales

''Les Orientales'' () is a collection of poems by Victor Hugo, inspired by the Greek War of Independence. They were first published in January 1829.

Of the forty-one poems, thirty-six were written during 1828. They offer a series of highly colou ...

, 1829; Les Feuilles d'automne

''Les Feuilles d'Automne'' (, ) is a collection of poems written by Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, huma ...

, 1831; , 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les Ombres, 1840. This cemented his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by , the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

and France's pre-eminent literary figure during the early 19th century. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be " or nothing", and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor in many ways. Like , Hugo furthered the cause of Romanticism, became involved in politics (though mostly as a champion of Republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

), and was forced into exile due to his political stances. Along with Chateaubriand he attended the Coronation of Charles X

The coronation of Charles X of France, Charles X took place on 29 May 1825 in Reims, where he was crowned King of France and Navarre. The ceremony was held at the Reims Cathedral, Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Reims in Reims, the traditional site for ...

in Reims

Reims ( ; ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French Departments of France, department of Marne (department), Marne, and the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, 12th most populous city in Fran ...

in 1825.

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry () was published in 1822 when he was only 20 years old and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, the collection that followed four years later in 1826 () revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction was published in February 1829 by Charles Gosselin without the author's name and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. (''The Last Day of a Condemned Man

''The Last Day of a Condemned Man'' () is a novella by Victor Hugo first published in 1829. It recounts the thoughts of a man condemned to die. Victor Hugo wrote this novel to express his feelings that the death penalty should be abolished.

Gene ...

'') would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, journalist, world federalist, and political activist. He was the recipient of the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the s ...

, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

. ''Claude Gueux,'' a documentary short story about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, was published in 1834. Hugo himself later considered it to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, .

Hugo became the figurehead of the Romantic literary movement with the plays ''Cromwell'' (1827) and ''Hernani'' (1830). ''Hernani'' announced the arrival of French romanticism: performed at the Comédie-Française

The Comédie-Française () or Théâtre-Français () is one of the few state theatres in France. Founded in 1680, it is the oldest active theatre company in the world. Established as a French state-controlled entity in 1995, it is the only state ...

, it was greeted with several nights of rioting as romantics and traditionalists clashed over the play's deliberate disregard for neo-classical rules. Hugo's popularity as a playwright grew with subsequent plays, such as ''Marion Delorme'' (1831), '' Le roi s'amuse'' (1832), and ''Ruy Blas'' (1838). Hugo's novel (''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (, originally titled ''Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482'') is a French Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The title refers to the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which features prominently throughout the novel. I ...

'') was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris into restoring the much neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Medieval architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissemen ...

, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but a full 17 years were needed for to be realised and finally published in 1862. Hugo had previously used the departure of prisoners for the Bagne of Toulon

The Bagne of Toulon was a notorious bagne, or penal establishment in Toulon, France, made famous as the place of imprisonment of the fictional Jean Valjean, the hero of Victor Hugo's novel ''Les Misérables''. It was opened in 1748 and closed in ...

in ''Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné''. He went to Toulon to visit the Bagne in 1839 and took extensive notes, though he did not start writing the book until 1845. On one of the pages of his notes about the prison, he wrote in large block letters a possible name for his hero: "JEAN TRÉJEAN". When the book was finally written, Tréjean became Jean Valjean

Jean Valjean () is the protagonist of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel ''Les Misérables''. The story depicts the character's struggle to lead a normal life and redeem himself after serving a 19-year-long prison sentence for stealing bread to feed his ...

.

Hugo was acutely aware of the quality of the novel, as evidenced in a letter he wrote to his publisher, Albert Lacroix, on 23 March 1862: "My conviction is that this book is going to be one of the peaks, if not the crowning point of my work." Publication of ''Les Misérables'' went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house and undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel ("Fantine

Fantine (French pronunciation: ) is a fictional character in Victor Hugo's 1862 novel ''Les Misérables''. She is a young ''Grisette (person), grisette'' in Paris who is impregnated by a rich student. After he abandons her, she is forced to look ...

"), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours and had an enormous impact on French society.

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; found it insincere, complained of its vulgarity, found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the brothers lambasted its artificiality, and —despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers—castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". However, ''Les Misérables'' proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; found it insincere, complained of its vulgarity, found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the brothers lambasted its artificiality, and —despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers—castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". However, ''Les Misérables'' proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the National Assembly of France

The National Assembly (, ) is the lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral French Parliament under the French Fifth Republic, Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (France), Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known ...

. Today, the novel remains his best-known work. It is popular worldwide and has been adapted for cinema, television, and stage shows.

An apocryphal tale has circulated, describing the shortest correspondence in history as having been between Hugo and his publisher Hurst and Blackett

Hurst and Blackett was a publisher founded in 1852 by Henry Blackett (26 May 1825 – 7 March 1871), the grandson of a London shipbuilder, and Daniel William Stow Hurst (17 February 1802 – 6 July 1870). Shortly after the formation of their partn ...

in 1862. Hugo was on vacation when was published. He queried the reaction to the work by sending a single-character telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pi ...

to his publisher, asking . The publisher replied with a single to indicate its success. Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, (''Toilers of the Sea

''Toilers of the Sea'' () is a novel by Victor Hugo published in 1866. The book is dedicated to the island of Guernsey, where Hugo spent 15 years in exile. Hugo uses the setting of a small island community to transmute seemingly mundane events i ...

''), published in 1866. The book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of . Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, where Hugo spent 15 years of exile, the novel tells of a man who attempts to win the approval of his beloved's father by rescuing his ship, intentionally marooned by its captain who hopes to escape with a treasure of money it is transporting, through an exhausting battle of human engineering against the force of the sea and an almost mythical beast of the sea, a giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, ...

. Superficially an adventure, one of Hugo's biographers calls it a "metaphor for the 19th century–technical progress, creative genius and hard work overcoming the immanent evil of the material world."

The word used in Guernsey to refer to squid (, also sometimes applied to octopus) was to enter the French language as a result of its use in the book. Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, (''The Man Who Laughs

''The Man Who Laughs'' (also published under the title ''By Order of the King'' from its subtitle in French) is a Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, originally published in April 1869 under the French title ''L'Homme qui rit''. It takes place in Engl ...

''), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. The novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as and , whose realist and naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work.

His last novel, (''Ninety-Three

''Ninety-Three'' (''Quatrevingt-treize'') is the last novel by the French writer Victor Hugo. Published in 1874, three years after the bloody upheaval of the Paris Commune that resulted out of popular reaction to Napoleon III's failure to win ...

''), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

during the French Revolution. Though Hugo's popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider ''Ninety-Three'' to be a work on par with Hugo's better-known novels.

Political life and exile

death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

and social injustice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has ofte ...

, and in favour of freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

and self-government

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

for Poland.

In 1848, Hugo was elected to the National Assembly of the Second Republic as a conservative. In 1849, he broke with the conservatives when he gave a noted speech calling for the end of misery and poverty. Other speeches called for universal suffrage and free education for all children. Hugo's advocacy to abolish the death penalty was renowned internationally.

When Louis Napoleon (

When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor to France. He moved to Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

, then Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

, from which he was expelled for supporting ''L'Homme'', a local newspaper that had published a letter to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

by a French republican deemed treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

ous. He finally settled with his family at Hauteville House

Hauteville House is a house where Victor Hugo lived during his exile from France, located at 38 Hauteville in St. Peter Port in Guernsey. In March 1927, the centenary year of Romanticism, Hugo's descendants Jeanne, Jean, Marguerite and Franço ...

in Saint Peter Port

St. Peter Port () is a town and one of the ten parishes on the island of Guernsey in the Channel Islands. It is the capital of the Bailiwick of Guernsey as well as the main port. The population in 2019 was 18,958.

St. Peter Port is a small tow ...

, Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, where he would live in exile from October 1855 until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, and . The pamphlets were banned in France but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed or published some of his best work during his period in Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, including , and three widely praised collections of poetry (, 1853; , 1856; and , 1859).

However, Víctor Hugo said in ''Les Misérables'':

Like most of his contemporaries, Hugo justified colonialism in terms of a civilizing

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of the state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond signed or spoken language ...

mission and putting an end to the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

on the Barbary coast. In a speech delivered on 18 May 1879, during a banquet to celebrate the abolition of slavery, in the presence of the French abolitionist writer and parliamentarian Victor Schœlcher, Hugo declared that the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

formed a natural divide between "ultimate civilisation and... utter barbarism." Hugo declared that "God offers Africa to Europe. Take it" and "in the nineteenth century the white man made a man out of the black, in the twentieth century Europe will make a world out of Africa".

This might partly explain why, in spite of his deep interest and involvement in political matters, he remained silent on the Algerian issue. He knew about the atrocities committed by the French Army during the French conquest of Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Regency of Algiers, and the French consul (representative), consul escalated into a blockade, following which the Jul ...

as evidenced by his diary but he never denounced them publicly; however, in ''Les Misérables'', Hugo wrote: "Algeria too harshly conquered, and, as in the case of India by the English, with more barbarism than civilization."

After coming in contact with

After coming in contact with Victor Schœlcher

Victor Schœlcher (; 22 July 1804 – 25 December 1893) was a French abolitionist, writer, politician and journalist, best known for his leading role in the End of slavery in France, abolition of slavery in France in 1848, during the French Secon ...

, a writer who fought for the abolition of slavery and French colonialism in the Caribbean, he started strongly campaigning against slavery. In a letter to American abolitionist Maria Weston Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery journ ...

, on 6 July 1851, Hugo wrote: "Slavery in the United States! It is the duty of this republic to set such a bad example no longer... The United States must renounce slavery, or they must renounce liberty." In 1859, he wrote a letter asking the United States government, for the sake of their own reputation in the future, to spare abolitionist John Brown's life, Hugo justified Brown's actions by these words: "Assuredly, if insurrection is ever a sacred duty, it must be when it is directed against Slavery." Hugo agreed to diffuse and sell one of his best known drawings, "Le Pendu", an homage to John Brown, so one could "keep alive in souls the memory of this liberator of our black brothers, of this heroic martyr John Brown, who died for Christ just as Christ.

As a novelist, diarist, and member of Parliament, Victor Hugo fought a lifelong battle for the abolition of the death penalty. ''The Last Day of a Condemned Man

''The Last Day of a Condemned Man'' () is a novella by Victor Hugo first published in 1829. It recounts the thoughts of a man condemned to die. Victor Hugo wrote this novel to express his feelings that the death penalty should be abolished.

Gene ...

'' published in 1829 analyses the pangs of a man awaiting execution; several entries in ''Things Seen'' (''Choses vues''), the diary he kept between 1830 and 1885, convey his firm condemnation of what he regarded as a barbaric sentence; on 15 September 1848, seven months after the Revolution of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, he delivered a speech before the Assembly and concluded, "You have overthrown the throne. ... Now overthrow the scaffold." His influence was credited in the removal of the death penalty from the constitutions of Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, and Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

. He had also pleaded for Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican politician, military commander, and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. A Zapotec peoples, Zapotec, he w ...

to spare the recently captured emperor Maximilian I of Mexico

Maximilian I (; ; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian archduke who became Emperor of Mexico, emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from 10 April 1864 until his execution by the Restored Republic (Mexico), Mexican Republ ...

, but to no avail.

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He was in Paris during the siege by the Prussian Army in 1870, famously eating animals given to him by the Paris Zoo. As the siege continued, and food became ever more scarce, he wrote in his diary that he was reduced to "eating the unknown".

During the

During the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

—the revolutionary government that took power on 18 March 1871 and was toppled on 28 May—Victor Hugo was harshly critical of the atrocities committed on both sides. On 9 April, he wrote in his diary, "In short, this Commune is as idiotic as the National Assembly is ferocious. From both sides, folly." Yet he made a point of offering his support to members of the Commune subjected to brutal repression. He had been in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

since 22 March 1871 when in the 27 May issue of the Belgian newspaper ''l'Indépendance'' Victor Hugo denounced the government's refusal to grant political asylum to the Communards threatened with imprisonment, banishment or execution. This caused so much uproar that in the evening a mob of fifty to sixty men attempted to force their way into the writer's house shouting, "Death to Victor Hugo! Hang him! Death to the scoundrel!"

Hugo, who said "A war between Europeans is a civil war," was a strong advocate for the creation of the United States of Europe

A federal Europe, also referred to as the United States of Europe (USE) or a European federation, is a hypothetical scenario of European integration leading to the formation of a sovereign superstate (similar to the United States of America), ...

. He expounded his views on the subject in a speech he delivered during the International Peace Congress

International Peace Congress, or International Congress of the Friends of Peace, was the name of a series of international meetings of representatives from peace societies from throughout the world held in various places in Europe from 1843 to 185 ...

which took place in Paris in 1849. Here he declared "nations of the continent, will, without losing your distinctive qualities and glorious individuality, be blended into a superior unity and constitute a European fraternity, just as Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

, Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

, have been blended into France", this new state would be administered by "a great Sovereign senate which will be to Europe what the Parliament is to England".

Because of his concern for the rights of artists and copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, ...

, he was a founding member of the , which led to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. However, in 's published archives, he states strongly that "any work of art has two authors: the people who confusingly feel something, a creator who translates these feelings, and the people again who consecrate his vision of that feeling. When one of the authors dies, the rights should totally be granted back to the other, the people." He was one of the earlier supporters of the concept of '' domaine public payant'', under which a nominal fee would be charged for copying or performing works in the public domain, and this would go into a common fund dedicated to helping artists, especially young people.

Religious views

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

views. He frequented spiritism

Spiritism may refer to:

Religion

* Espiritismo, a Latin American and Caribbean belief that evolved and less evolved spirits can affect health, luck and other aspects of human life

* Kardecist spiritism, a new religious movement established in ...

during his exile (where he participated also in many séance

A séance or seance (; ) is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word ''séance'' comes from the French language, French word for "session", from the Old French , "to sit". In French, the word's meaning is quite general and mundane: one ma ...

s conducted by Madame Delphine de Girardin

Delphine de Girardin (24 January 1804 – 29 June 1855), pen name ''Vicomte Delaunay'', was a French writer.

Life

de Girardin was born in Aachen, and christened Delphine Gay. Her mother, the well-known Madame Sophie Gay, brought her up in the mi ...

) and in later years settled into a rationalist deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

similar to that espoused by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

. A census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, and he replied, "No. A Freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an unorthodox attitude or belief.

A freethinker holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and should instead be reached by other meth ...

."

After 1872, Hugo never lost his antipathy towards the Catholic Church. He felt the Church was indifferent to the plight of the working class under the oppression of the monarchy. Perhaps he also was upset by the frequency with which his work appeared on the Church's list of banned books. Hugo counted 740 attacks on ''Les Misérables'' in the Catholic press. When Hugo's sons Charles and died, he insisted that they be buried without a crucifix

A crucifix (from the Latin meaning '(one) fixed to a cross') is a cross with an image of Jesus on it, as distinct from a bare cross. The representation of Jesus himself on the cross is referred to in English as the (Latin for 'body'). The cru ...

or priest. In his will, he made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral.

Yet he believed in life after death and prayed every single morning and night, convinced as he wrote in ''The Man Who Laughs

''The Man Who Laughs'' (also published under the title ''By Order of the King'' from its subtitle in French) is a Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, originally published in April 1869 under the French title ''L'Homme qui rit''. It takes place in Engl ...

'' that "Thanksgiving has wings and flies to its right destination. Your prayer knows its way better than you do."

Hugo's rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

can be found in poems such as ''Torquemada Torquemada may refer to:

People

* Juan de Torquemada (cardinal) (1388–1468), Spanish cardinal and ecclesiastical writer

* Tomás de Torquemada (1420–1498), prominent leader of the Spanish Inquisition

* Antonio de Torquemada (c. 1507� ...

'' (1869, about religious fanaticism

Religious fanaticism or religious extremism is a pejorative designation used to indicate uncritical zeal or obsessive enthusiasm that is related to one's own, or one's group's, devotion to a religion – a form of human fanaticism that cou ...

), ''The Pope'' (1878, anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

), ''Religions and Religion'' (1880, denying the usefulness of churches) and, published posthumously, ''The End of Satan'' and ''God'' (1886 and 1891 respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (; Classical Latin: ''gryps'' or ''grypus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk ...

and rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

as an angel

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

).

''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

''The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (, originally titled ''Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482'') is a French Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The title refers to the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which features prominently throughout the novel. I ...

'' also garnered attention due to its portrayal of the abuse of power by the church, even getting listed as one of the "forbidden books" by it. In fact, earlier adaptations had to change the villain, Claude Frollo

Claude Frollo () is a fictional Christian clergyman and the main antagonist of Victor Hugo's 1831 novel '' The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (original French title: ''Notre-Dame de Paris''). He is also an alchemist, Renaissance humanist, and intell ...

from being a priest to avoid backlash.

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (; 30 March 185329 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who is among the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade, he created approximately 2,100 artworks ...

ascribed the saying "Religions pass away, but God remains," actually by Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

, to Hugo.

Relationship with music

Although Hugo's many talents did not include exceptional musical ability, he nevertheless had a great impact on the music world through the inspiration that his works provided for composers of the 19th and 20th centuries. Hugo himself particularly enjoyed the music ofGluck

Christoph Willibald ( Ritter von) Gluck (; ; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire at ...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

, Weber

Weber may refer to:

Places United States

* Weber, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Weber City, Virginia, a town

* Weber City, Fluvanna County, Virginia, an unincorporated community

* Weber County, Utah

* Weber Canyon, Utah

* Weber R ...

and Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Meyer Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Ro ...

. In , he calls the huntsman's chorus in Weber's ''Euryanthe

''Euryanthe'' ( J. 291, Op. 81) is a German grand heroic-romantic opera by Carl Maria von Weber, first performed at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna on 25 October 1823.Brown, p. 88 Though acknowledged as one of Weber's most important operas, ...

'', "perhaps the most beautiful piece of music ever composed". He also greatly admired Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

and, rather unusually for his time, appreciated works by composers from earlier centuries such as Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; , ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon ...

and Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considere ...

."", ed. Arnaud Laster, , no. 208 (2002).

Two famous musicians of the 19th century were friends of Hugo: Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

and Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

. The latter played Beethoven in Hugo's home, and Hugo joked in a letter to a friend that, thanks to Liszt's piano lessons, he learned how to play a favourite song on the piano – with only one finger. Hugo also worked with composer Louise Bertin

Louise-Angélique Bertin (; 15 January 1805 – 26 April 1877) was a French composer and poet.Hugh Macdonald, "Bertin, Louise", in: ''Grove Music Online'Oxford Music Online(subscription required) (accessed 30 December 2010).

Life and music

Ber ...

, writing the libretto for her 1836 opera '' La Esmeralda'', which was based on the character in ''The Hunchback of Notre Dame''. Although for various reasons the opera closed soon after its fifth performance and is little known today, it has enjoyed a modern revival, both in a piano/song concert version by Liszt at the 2007 and in a full orchestral version presented in July 2008 at . He was also on friendly terms with Frederic Chopin Frederic may refer to:

Places United States

* Frederic, Wisconsin, a village in Polk County

* Frederic Township, Michigan, a township in Crawford County

** Frederic, Michigan, an unincorporated community

Other uses

* Frederic (band), a Japanese r ...

. He introduced him to George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

who would be his lover for years. In 1849, Hugo attended Chopin's funeral.

On the other hand, he had low esteem for Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, whom he described as "a man of talent coupled with imbecility."

Well over one thousand musical compositions have been inspired by Hugo's works from the 19th century until the present day. In particular, Hugo's plays, in which he rejected the rules of classical theatre in favour of romantic drama, attracted the interest of many composers who adapted them into operas. More than one hundred operas are based on Hugo's works and among them are Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian Romantic composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the ''bel canto'' opera ...

's ''Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was an Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the illegitimate daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She was a former governor of Spoleto.

Her family arranged ...

'' (1833), Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( ; ; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma, to a family of moderate means, recei ...

's (1851) and ''Ernani

''Ernani'' is an operatic ''dramma lirico'' in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, based on the 1830 play ''Hernani (drama), Hernani'' by Victor Hugo.

Verdi was commissioned by the Teatro La Fenice in Ve ...

'' (1844), and Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

, and .

Today, Hugo's work continues to stimulate musicians to create new compositions. For example, Hugo's novel against capital punishment, ''The Last Day of a Condemned Man'', was adapted into an opera by , with a libretto by and premièred by their brother, tenor , in 2007. In Guernsey, every two years, the Victor Hugo International Music Festival attracts a wide range of musicians and the premiere of songs specially commissioned from such composers as , , , and and based on Hugo's poetry.

Remarkably, not only has Hugo's literary production been the source of inspiration for musical works, but also his political writings have received attention from musicians and have been adapted to music. For instance, in 2009, Italian composer Matteo Sommacal was commissioned by Festival "Bagliori d'autore" and wrote a piece for speaker and chamber ensemble entitled ''Actes et paroles'', with a text elaborated by Chiara Piola Caselli after Victor Hugo's last political speech addressed to the Assemblée législative, "Sur la Revision de la Constitution" (18 July 1851), and premiered in Rome on 19 November 2009, in the auditorium of the Institut français, Centre Saint-Louis, French Embassy to the Holy See, by Piccola Accademia degli Specchi featuring the composer .

Declining years and death

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He was confident that he would be offered the dictatorship, as shown by the notes he kept at the time: "Dictatorship is a crime. This is a crime I am going to commit," but he felt he had to assume that responsibility. Despite his popularity, Hugo lost his bid for re-election to the National Assembly in 1872.

Throughout his life Hugo kept believing in unstoppable humanistic progress. In his last public address on 3 August 1879 he prophesied, in an over-optimistic way, "In the twentieth century war will be dead, the scaffold will be dead, hatred will be dead, frontier boundaries will be dead, dogmas will be dead; man will live."

Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle was interned in an

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He was confident that he would be offered the dictatorship, as shown by the notes he kept at the time: "Dictatorship is a crime. This is a crime I am going to commit," but he felt he had to assume that responsibility. Despite his popularity, Hugo lost his bid for re-election to the National Assembly in 1872.

Throughout his life Hugo kept believing in unstoppable humanistic progress. In his last public address on 3 August 1879 he prophesied, in an over-optimistic way, "In the twentieth century war will be dead, the scaffold will be dead, hatred will be dead, frontier boundaries will be dead, dogmas will be dead; man will live."

Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle was interned in an insane asylum

The lunatic asylum, insane asylum or mental asylum was an institution where people with mental illness were confined. It was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Modern psychiatric hospitals evolved from and eventually replace ...

, and his two sons died. (Adèle's biography inspired the movie '' The Story of Adele H.'') His wife Adèle had died in 1868.

His faithful mistress, Juliette Drouet

Juliette Drouet (), born Julienne Josephine Gauvain (; 10 April 1806 – 11 May 1883), was a French actress. She abandoned her career on the stage after becoming the mistress of Victor Hugo, to whom she acted as a secretary and travelling compan ...

, died in 1883, only two years before his own death. Despite his personal loss, Hugo remained committed to the cause of political change. On 30 January 1876, he was elected to the newly created Senate. This last phase of his political career was considered a failure. Hugo was a maverick and achieved little in the Senate. He suffered a mild stroke on 27 June 1878. To honour the fact that he was entering his 80th year, he received one of the greatest tributes to a living writer ever held. The celebrations began on 25 June 1881, when Hugo was presented with a vase, the traditional gift for sovereigns. On 27 June, one of the largest parades in French history was held.

Marchers stretched from the , where the author was living, down the , and all the way to the centre of Paris. The paraders marched for six hours past Hugo as he sat at the window at his house. Every inch and detail of the event was for Hugo; the official guides even wore cornflowers as an allusion to Fantine's song in . On 28 June, the city of Paris changed the name of the Avenue d'Eylau to Avenue Victor-Hugo. Letters addressed to the author were from then on labelled "To Mister Victor Hugo, In his avenue, Paris". Two days before dying, he left a note with these last words: "To love is to act."

On 20 May 1885, ''le Petit Journal'' published the official medical bulletin on Hugo's health condition. "The illustrious patient" was fully conscious and aware that there was no hope for him. They also reported from a reliable source that at one point in the night he had whispered the following , "En moi c’est le combat du jour et de la nuit."—"In me, this is the battle between day and night." ''Le Matin'' published a slightly different version: "Here is the battle between day and night."

Hugo died on 22 May 1885, at 50 Avenue Victor Hugo (now number 124). His death, from pneumonia, generated intense national mourning. He was not only revered as a towering figure in literature, he was a statesman who shaped the Third Republic and democracy in France. All his life he remained a defender of liberty, equality and fraternity as well as an adamant champion of French culture. In 1877, aged 75, he wrote, "I am not one of these sweet-tempered old men. I am still exasperated and violent. I shout and I feel indignant and I cry. Woe to anyone who harms France! I do declare I will die a fanatic patriot."

Although he had requested a pauper's funeral, by decree of President Jules Grévy

François Judith Paul Grévy (15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891), known as Jules Grévy (), was a French people, French lawyer and politician who served as President of France from 1879 to 1887. He was a leader of the Opportunist Republicans, M ...

he was awarded a state funeral, an event described by Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

as a "veritable orgy of bad taste". More than two million people joined Hugo's funeral procession in Paris from the to the , where he was buried. He shares a crypt within the with and . Most large French towns and cities have a street or square named after him.

Hugo left five sentences as his last will, to be officially published:

Drawings

Hugo produced more than 4,000 drawings, with about 3,000 drawings still in existence. Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile when he made the decision to stop writing to devote himself to politics. Drawing became his exclusive creative outlet between 1848 and 1851. Hugo worked only on paper, and on a small scale; usually in dark brown or black pen-and-ink wash, sometimes with touches of white, and rarely with colour.Personal life

Family

Marriage

Hugo marriedAdèle Foucher

Adèle Foucher (27 September 1803 – 27 August 1868) was the wife of French writer Victor Hugo, with whom she was acquainted from childhood. Her affair with the critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve became the raw material for Sainte-Beuve's ...

in October 1822. Despite their respective affairs, they lived together for nearly 46 years until she died in August 1868. Hugo, who was still banished from France, was unable to attend her funeral in Villequier, where their daughter Léopoldine was buried. From 1830 to 1837, Adèle had an affair with Charles-Augustin Sainte Beuve, a reviewer and writer.

Children

Adèle and Victor Hugo had their first child, Léopold, in 1823, but the boy died in infancy. On 28 August 1824, the couple's second child, Léopoldine, was born, followed byCharles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

on 4 November 1826, François-Victor on 28 October 1828, and Adèle on 28 July 1830.

Hugo's eldest and favourite daughter, Léopoldine, died in 1843 at the age of 19, shortly after her marriage to Charles Vacquerie. On 4 September, she drowned in the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

at Villequier when the boat she was in overturned. Her young husband died trying to save her. The death left her father devastated; Hugo was travelling at the time, in the south of France, when he first learned about Léopoldine's death from a newspaper that he read in a café.

He describes his shock and grief in his famous poem "À Villequier":

He wrote many poems afterward about his daughter's life and death. His most famous poem is "Demain, dès l'aube" (Tomorrow, at Dawn), in which he describes visiting her grave.

Exile

Hugo decided to live in exile afterNapoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's coup d'état at the end of 1851. After leaving France, Hugo lived in Brussels briefly in 1851, and then moved to the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

, first to Jersey (1852–1855) and then to the smaller island of Guernsey in 1855, where he stayed until Napoleon III's fall from power in 1870. Although Napoleon III proclaimed a general amnesty in 1859, under which Hugo could have safely returned to France, the author stayed in exile, only returning when Napoleon III was removed from power by the creation of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

in 1870, as a result of the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Napoleon III, Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and ...

in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. After the Siege of Paris from 1870 to 1871, Hugo lived again in Guernsey from 1872 to 1873, and then finally returned to France for the remainder of his life. In 1871, after the death of his son Charles, Hugo took custody of his grandchildren Jeanne and Georges-Victor.

Other relationships

Juliette Drouet

From February 1833 until her death in 1883,

From February 1833 until her death in 1883, Juliette Drouet

Juliette Drouet (), born Julienne Josephine Gauvain (; 10 April 1806 – 11 May 1883), was a French actress. She abandoned her career on the stage after becoming the mistress of Victor Hugo, to whom she acted as a secretary and travelling compan ...

devoted her whole life to Victor Hugo, who never married her even after his wife died in 1868. He took her on his numerous trips and she followed him in exile on Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

. There Hugo rented a house for her near Hauteville House

Hauteville House is a house where Victor Hugo lived during his exile from France, located at 38 Hauteville in St. Peter Port in Guernsey. In March 1927, the centenary year of Romanticism, Hugo's descendants Jeanne, Jean, Marguerite and Franço ...

, his family home. She wrote some 20,000 letters in which she expressed her passion or vented her jealousy on her womanizing lover.

On 25 September 1870 during the Siege of Paris (19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871) Hugo feared the worst. He left his children a note reading as follows:

"J.D.

She saved my life in December 1851. For me she underwent exile. Never has her soul forsaken mine. Let those who have loved me love her. Let those who have loved me respect her.

She is my widow."

V.H.

Léonie d'Aunet

For more than seven years, Léonie d'Aunet, who was a married woman, was involved in a love relationship with Hugo. Both were caught in adultery on 5 July 1845. Hugo, who had been a Member of the Chamber of Peers since April, avoided condemnation whereas his mistress had to spend two months in prison and six in a convent. Many years after their separation, Hugo made a point of supporting her financially.Others

Hugo gave free rein to his libido until a few weeks before his death. He sought a wide variety of women of all ages, be they courtesans, actresses, prostitutes, admirers, servants or revolutionaries likeLouise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and prominent figure during the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she began to embrace anarchism, and upon her return to France she emerged as an im ...

for sexual activity. He systematically reported his casual affairs using his own code, as Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

did, to make sure they would remain secret. For instance, he resorted to Latin abbreviations (''osc.'' for kisses) or to Spanish (''Misma. Mismas cosas'': The same. Same things). Homophones are frequent: ''Seins'' (Breasts) becomes Saint; ''Poële'' (Stove) actually refers to ''Poils'' (Pubic hair). Analogy also enabled him to conceal the real meaning: A woman's ''Suisses'' (Swiss) are her breasts—because Switzerland is renowned for its milk. After a rendezvous with a young woman named ''Laetitia'' he would write ''Joie'' (Happiness) in his diary. If he added ''t.n.'' (''toute nue'') he meant she stripped naked in front of him. The initials ''S.B.'' discovered in November 1875 may refer to Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including by Alexandre Dumas fils, ...

.

Nicknames

Victor Hugo acquired several nicknames. The first one originated from his own description ofShakespeare