Charles Hercules Green on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Hercules Green (26 December 19191 November 1950) was an Australian military officer who was the youngest

On 25 June 1950, the

On 25 June 1950, the

The two companies attacked before dusk, D Company being supported by US tanks, and despite the heavy enemy fire, both secured their objectives on the ridge by 17:30. Eleven T-34 tanks and two

The two companies attacked before dusk, D Company being supported by US tanks, and despite the heavy enemy fire, both secured their objectives on the ridge by 17:30. Eleven T-34 tanks and two

Green was initially buried in the Christian churchyard at Pakchon on the day he died, but his body was soon exhumed and buried in the

Green was initially buried in the Christian churchyard at Pakchon on the day he died, but his body was soon exhumed and buried in the

Guide to the papers of Papers of Charles and Olwyn Green

Collection Number: PR00466, Australian War Memorial {{DEFAULTSORT:Green, Charles Hercules 1919 births 1950 deaths Military personnel from New South Wales Australian colonels Australian Army personnel of World War II Australian military personnel killed in the Korean War Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Foreign recipients of the Silver Star People from Grafton, New South Wales Burials at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia. It is a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF), along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army ...

infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

commander during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He went on to command the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

The Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) is the parent administrative regiment for regular infantry battalions of the Australian Army and is the senior infantry regiment of the Royal Australian Infantry Corps. It was originally formed in 1948 as a t ...

(3 RAR), during the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, where he died of wounds. He remains the only commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

of a Royal Australian Regiment battalion to die on active service. Green joined the part-time Militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

in 1936, and before the outbreak of World War II had been commissioned as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

. He volunteered for overseas service soon after the war began in September 1939, and served in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and the Battle of Greece

The German invasion of Greece or Operation Marita (), were the attacks on Greece by Italy and Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Greco-Italian War, was followed by the German invasi ...

with the 2/2nd Battalion. After the action at Pineios Gorge on 18 April 1941, Green became separated from the main body of the battalion, and made his way through Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

to Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, to rejoin the reformed 2/2nd Battalion. The 2/2nd Battalion returned to Australia in August 1942 via Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

(modern Sri Lanka), to meet the threat posed by the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

.

Green performed instructional duties and attended courses until July 1943 when he rejoined the 2/2nd Battalion as its second-in-command

Second-in-command (2i/c or 2IC) is a title denoting that the holder of the title is the second-highest authority within a certain organisation.

Usage

In the British Army or Royal Marines, the second-in-command is the deputy commander of a unit, f ...

. At the time, the unit was training in Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

. From March to July 1945, Green commanded the 2/11th Battalion during the Aitape-Wewak campaign in New Guinea. For his performance during the campaign, Green was appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful command and leadership during active operations, typicall ...

. After the war, Green briefly returned to civilian life and part-time military service as commanding officer of the 41st Battalion. When the Regular Army was formed, Green returned to full-time service in early 1949.

He was attending Staff College when the Korean War broke out in June 1950, and Army Headquarters selected him to command 3 RAR, which deployed as part of the United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

formed to fight the North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

ns. After a brief period of training in Japan, where 3 RAR was part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was the British Commonwealth taskforce consisting of Australian, British, Indian, and New Zealander military forces in occupied Japan, from 1946 until the end of occupation in 1952.

At its pe ...

, Green led the battalion to Korea in late September. Immediately pressed into action as part of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade

The 27th Infantry Brigade was an infantry brigade of the British Army that saw service in the First World War, the Second World War, and the Korean War. In Korea, the brigade was known as 27th British Commonwealth Brigade due to the addition of Ca ...

, the battalion advanced as part of the UN offensive into North Korea

The UN offensive into North Korea was a large-scale offensive in late 1950 by United Nations (UN) forces against North Korean forces during the Korean War.

On 27 September near Osan, UN forces coming from Inchon linked up with UN forces that had ...

. Sharp fighting followed between 3 RAR and Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

(KPA) forces, during the Battle of the Apple Orchard, the Battle of the Broken Bridge and the Battle of Chongju. The day after the latter battle, 30 October, Green was resting in his tent in a reserve position when he was wounded in the abdomen by a shell fragment. Evacuated to hospital, he died two days later, aged 30, and was posthumously awarded the US Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

. Green was a popular and respected commanding officer, whose loss was keenly felt by his men. According to three officers who served with 3 RAR in Korea, he is considered one of the Australian Army's better unit-level commanders. As recently as 1996, his career was described as an inspiration to serving Australian soldiers.

Early life

Born on 26 December 1919 at Grafton in north-easternNew South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, Charles Hercules Green was the second of three children of his parents, Australian-born Hercules John Green and Bertha . He attended school at Swan Creek Public School and Grafton High School. In 1933, Green began working for his father on the family dairy farm

Dairy farming is a class of agriculture for the long-term production of milk, which is processed (either on the farm or at a dairy plant, either of which may be called a dairy) for the eventual sale of a dairy product. Dairy farming has a h ...

. He also did ploughing and road construction work using two draught horse

A draft horse (US) or draught horse (UK), also known as dray horse, carthorse, work horse or heavy horse, is a large horse bred to be a working animal hauling freight and doing heavy agricultural tasks such as plough, plowing. There are a nu ...

s he acquired. Green was enthusiastic about the sport of cricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

as well as horse riding. On 28 October 1936, at the age of 16, he enlisted in the 41st Battalion, a part-time infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

unit of the Militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

. In 1938 Green was promoted to sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

, and was commissioned as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

on 20 March 1939, aged 19.

World War II

Middle East and Greece

With the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Green volunteered for overseas service and on 13 October 1939, he enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initial strength of one ...

(2nd AIF) which was being raised for that purpose. He was posted to the 2/2nd Battalion, which was one of the first units raised upon the outbreak of the war and formed part of the 16th Brigade that was assigned to the 6th Division. The 2/2nd Battalion was deployed to the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

in February 1940. Green initially served as one of the 2/2nd's platoon commanders, but accidentally injured himself, and missed out on taking part in 6th Division's first combat action, which took place during the North African campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

between December 1940 and January 1941.

On 12 March he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

, and on the 22nd the battalion arrived in Greece to repel the anticipated German invasion. The battalion was deployed north into the Macedonia region

Macedonia ( ) is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well ...

to face the German assault, which began on 6 April. It took up positions at Veria

Veria (; ), officially transliterated Veroia, historically also spelled Beroea or Berea, is a city in Central Macedonia, in the geographic region of Macedonia, northern Greece, capital of the regional unit of Imathia. It is located north-nor ...

on 7 April, but the Allied armies withdrew, so the battalion did not fight until mid-April. Green and the rest of the 2/2nd Battalion saw action at Pineios Gorge on 18 April. The British and Commonwealth forces attempted to block the German advance at the Gorge. They were quickly overwhelmed by the larger German forces, the 2/2nd Battalion losing 44 killed or wounded and 55 taken prisoner

A prisoner, also known as an inmate or detainee, is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement or captivity in a prison or physical restraint. The term usually applies to one serving a Sentence (law), se ...

in desperate fighting. This resulted in the members of the battalion being dispersed into the surrounding hills. While elements of the battalion were able to rejoin the main forces withdrawing south to embark on ships, others were forced to make their escape independently.

Green and many other members of the battalion evaded capture by undertaking a hazardous journey through the Aegean Islands, then Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, to Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, which Green reached on 23 May. Green reached the island of Euboea

Euboea ( ; , ), also known by its modern spelling Evia ( ; , ), is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete, and the sixth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by ...

in the Aegean on 7 May, where he met several other members of the battalion. They travelled on to the island of Skyros

Skyros (, ), in some historical contexts Romanization of Greek, Latinized Scyros (, ), is an island in Greece. It is the southernmost island of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC, the island was known as ...

, and after narrow escapes from detection by German troops and aircraft, reached Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

(modern İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

) on the Turkish coast, where they obtained the assistance of two Turkish officers who had fought the Australians at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Disguised as "English civil engineers" they caught a train to Alexandretta (modern İskenderun), from where they boarded a Norwegian ship to Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

, Egypt. Green learned a great deal from his experiences in Greece. According to Margaret Barter, the author of his entry in the ''Australian Dictionary of Biography

The ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'' (ADB or AuDB) is a national co-operative enterprise founded and maintained by the Australian National University (ANU) to produce authoritative biographical articles on eminent people in Australia's ...

'', he contributed a "sensitive account" of the campaign to a battalion history, ''Nulli Secundus Log'', which was published in 1946. During his time in Greece, Green developed a reputation as a calm and reassuring leader who communicated clearly with the soldiers under his command, a fellow officer observing that " oops would follow Charlie anywhere because he understood them and they understood he was fair dinkum eaning: authentic.

After being rebuilt in Palestine, the 2/2nd Battalion was sent to undertake garrison duties in northern Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

between October 1941 and January 1942. On 11 March it left the Middle East to return to Australia to meet the threat posed by the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. On the way home, the 16th Brigade was diverted to defend Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

(modern Sri Lanka), where the 2/2nd Battalion was part of the garrison between 27 March and 13 July. Green was temporarily promoted to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 19 June.

Australia

The battalion finally disembarked at Melbourne on 4 August. Having injured his foot and contractedtyphoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

while in Ceylon, when the 2/2nd was sent to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

in September, Green was unable to join them. On 30 December, having been substantively promoted to major in September, he was posted as an instructor to the First Australian Army's Junior Tactical School in Southport, Queensland

Southport is a coastal town and the most populous suburb in the City of Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia. It contains the Gold Coast central business district. In the , Southport had a population of 36,786 people.

Geography

Southport is ...

. He married Edna Olwyn Warner at St Paul's Anglican Church, Ulmarra, New South Wales

Ulmarra is a small town on the south bank of the Clarence River (New South Wales), Clarence River in New South Wales, Australia in the Clarence Valley, New South Wales, Clarence Valley district. At the , Ulmarra had a population of 418 people.

...

, on 30 January 1943; his best man was his former commanding officer, Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Frederick Chilton

Dr. Frederick Chilton is a fictional character appearing in Thomas Harris's novels '' Red Dragon'' (1981) and '' The Silence of the Lambs'' (1988), along with the film and television adaptations of Harris's novels.

In the novels

''Red Dragon'' ...

. Green's posting to the First Army Junior Tactical School ended on 31 March 1943. On 26 June he took up an instructional position at the Junior Wing of the Land Headquarters Tactical School at Beenleigh, Queensland

Beenleigh is a town and Suburbs and localities (Australia), suburb in the City of Logan, Queensland, Australia. In the , the suburb of Beenleigh had a population of 8,425 people.

A government survey for the new town was conducted in 1866. The ...

.

Green returned to regimental duties in July 1943 and was made second-in-command

Second-in-command (2i/c or 2IC) is a title denoting that the holder of the title is the second-highest authority within a certain organisation.

Usage

In the British Army or Royal Marines, the second-in-command is the deputy commander of a unit, f ...

of the 2/2nd Battalion, which had returned from New Guinea after fighting in the Kokoda Trail campaign

The Kokoda Track campaign or Kokoda Trail campaign was part of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign consisted of a series of battles fought between July and November 1942 in what was then the Australian Territory of Papua. It was primar ...

and the subsequent Battle of Buna–Gona

The battle of Buna–Gona was part of the New Guinea campaign in the Pacific War, Pacific theatre during World War II. It followed the conclusion of the Kokoda Track campaign and lasted from 16 November 1942 until 22 January 1943. The battle wa ...

, and was training in north Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

. Although Green was considered the natural successor to the previous commanding officer, now-Brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

Cedric Edgar, his posting as second-in-command alleviated the tensions created by the appointment of an "outsider"—Lieutenant Colonel Allan Cameron—to command the battalion. Green undertook the senior officers' course at the Land Headquarters Tactical School between 18 August and 1 November 1944. During this course he was described as an "outstanding student". Chilton later observed, "Although quite young at the time he was very mature; a quiet, calm man, obviously with exceptional reserves of and force of character".

Aitape-Wewak campaign

On 30 December 1944, Green arrived in the town ofAitape

Aitape is a small town of about 18,000 people on the north coast of Papua New Guinea in the Sandaun Province. It is a coastal settlement that is almost equidistant from the provincial capitals of Wewak and Vanimo, and marks the midpoint of th ...

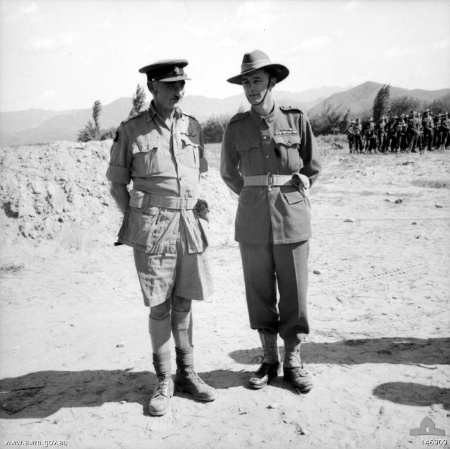

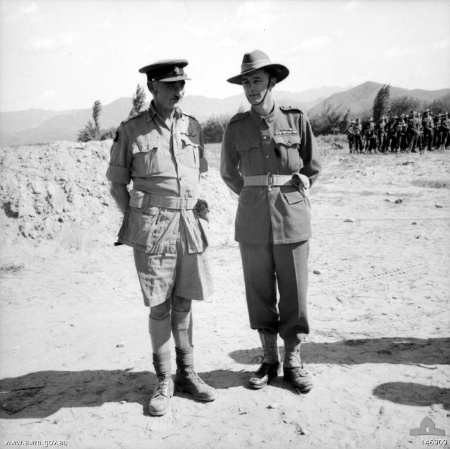

, on the north coast of New Guinea, where the 6th Division was taking over responsibility for the area from US forces. On 9 March 1945, Green took over command of the 2/11th Battalion, part of Brigadier James Martin's 19th Brigade of the 6th Division. At the age of only 25 he was the youngest Australian battalion commander during the war. Green was promoted to temporary lieutenant colonel five days later.

The battalion had landed at Aitape on 13 November 1944 to take part in the Aitape-Wewak campaign against the Japanese 18th Army. For the 2/11th Battalion, the campaign consisted mainly of arduous patrolling operations. Before Green took command, the unit had been part of the push by the 19th Brigade along the coast east of the Danmap River from 17 December to 20 January 1945. During this advance, the battalion lost 20 killed and 29 wounded, and killed 118 Japanese.

In early April, after Green had taken charge, the 19th Brigade was committed to an offensive against Wewak

Wewak is the capital of the East Sepik province of Papua New Guinea. It is on the northern coast of the island of New Guinea. It is the largest town between Madang and Jayapura. It is the see city (seat) of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wewak. ...

, and concentrated at the base at the village of But. As part of this offensive, the 2/11th and the 2/7th Commando Squadron were sent on a wide sweeping movement inland to cut off the Japanese, who were abandoning Wewak in the face of pressure from the 2/4th Battalion and withdrawing their main force into the Prince Alexander Mountains

The Prince Alexander Mountains are a mountain range in Papua New Guinea. The range is located on the northern coast of New Guinea. The Torricelli Mountains lie to the west, and the basin of the Sepik River lies to the south. Mount Turu is a nota ...

. After an arduous cross-country march across a swamp, the battalion arrived near Wirui Mission on 10 May and killed three Japanese who stumbled into their perimeter. This was followed by a series of clashes, culminating in the capture of a hill on 15 May by a company that lost four killed and 18 wounded, while killing 16 Japanese and capturing four machine guns. This was considered the hardest fighting the battalion had been involved in since arriving in New Guinea. This fighting in the foothills continued until the 27th when Green ordered a two-company attack to clear a pocket of Japanese. Supported by a 2,360-round artillery bombardment, the two companies killed 15 Japanese for the loss of two killed and six wounded. In total, during the May offensive, the 2/11th lost 23 killed and 63 wounded, and by the end of the month it was only 552 strong from a strength of 627 at the beginning of May, and only fielded 223 riflemen instead of 397. Soldiers from Headquarters Company were redistributed to the rifle companies to bring them closer to establishment strength.

At the end of May, the 19th Brigade received orders to capture Mount Tazaki and Mount Shiburangu in the Prince Alexander Mountains. Initially, the 2/11th was placed in reserve, as it was depleted and its soldiers were weary. On 10 June, the battalion was given the task of protecting the area from Boram airfield to Cape Moem, and on the 19th the battalion contributed one company for an attack on Mount Tazaki. After an airstrike and artillery bombardment, B Company of the 2/11th secured its objective which had been abandoned by the Japanese. In early July, the 8th Brigade relieved elements of the 19th Brigade, including the 2/11th. During the Aitape-Wewak campaign, the 2/11th suffered 144 casualties.

As a result of his efforts while commanding the 2/11th, Green was later appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful command and leadership during active operations, typicall ...

(DSO). The citation highlighted: the challenging terrain and conditions throughout the campaign; the interdiction of the battalion's supply lines by the Japanese early in the campaign; the particularly stiff and determined enemy resistance and considerable casualties; Green's deft handling of his logistics; his outstanding leadership which helped him maintain morale and efficiency within the battalion; and the fact that all objectives assigned to the unit during the campaign were achieved. After the Japanese surrendered on 15 August, members of the battalion began to be sent home in groups to Australia for demobilisation. The last members of the unit left Wewak on 10 November.

Post World War II

After being discharged from the 2nd AIF on 23 November 1945, Green was placed on the Reserve of Officers List on 21 December. He returned to Grafton where he worked as a clerk at the Producers' Co-operative Distributing Society Ltd. He also studied accountancy on a part-time basis. During this time he and his wife had a daughter, Anthea, and his award of the DSO was announced on 6 March 1947. When Australia's part-time military force was re-raised under the guise of Citizens Military Forces, Green returned to the 41st Battalion, serving as its commanding officer from 1 April 1948. With the establishment of the Regular Army, Green returned to full-time military service on 6 January 1949. In 1950 he was selected to attend Staff College atFort Queenscliff

Fort Queenscliff, in Victoria, Australia, dates from 1860 when an open battery was constructed on Shortland's Bluff to defend the entrance to Port Phillip. The Fort, which underwent major redevelopment in the late 1870s and 1880s, became the he ...

, Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

.

Korean War

On 25 June 1950, the

On 25 June 1950, the Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

(KPA) crossed the border from North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

into South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

and advanced towards the capital Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

, which fell in less than a week. The KPA continued toward the port of Pusan

Busan (), officially Busan Metropolitan City, is South Korea's second most populous city after Seoul, with a population of over 3.3 million as of 2024. Formerly romanized as Pusan, it is the economic, cultural and educational center of southe ...

and two days later, the United States offered its assistance to South Korea. In response, the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

requested United Nations (UN) member states to assist in repelling the North Korean attack. Australia initially committed North American P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in 1940 by a team headed by James H. Kin ...

fighter-bomber

A fighter-bomber is a fighter aircraft that has been modified, or used primarily, as a light bomber or attack aircraft. It differs from bomber and attack aircraft primarily in its origins, as a fighter that has been adapted into other roles, wh ...

s from No. 77 Squadron RAAF and infantry from the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

The 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) is the armoured infantry battalion of the Australian Army, based in Kapyong Lines, Townsville as part of the 3rd Brigade (Armoured Amphibious). 3 RAR traces its lineage to 1945 and has seen ...

(3 RAR), both of which were stationed in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was the British Commonwealth taskforce consisting of Australian, British, Indian, and New Zealander military forces in occupied Japan, from 1946 until the end of occupation in 1952.

At its pe ...

(BCOF). When the war broke out, 3 RAR was understaffed, underequipped and unprepared for combat as a unit. Immediate action was taken to bring it up to strength with reinforcements and new equipment from Australia, along with an intense training program.

When the Australian government committed 3 RAR, Army Headquarters determined that it would be led by an officer who had served in World War II and had a distinguished record. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel F. S. Walsh, who had been in command of the battalion for a year, was to be replaced. Still attending Staff College, Green was chosen. He left Australia for Japan on 8 September, and took over command of 3 RAR on 12 September. He oversaw another two weeks of unit training in Japan, then flew to South Korea on 25 September to await the battalion's arrival. 3 RAR arrived in Pusan on 28 September. By that time, the KPA was retreating back into North Korea following the Inchon landings and Pusan Perimeter Offensive. Green's battalion joined Brigadier Basil Coad

Major General Basil Aubrey Coad, (27 September 1906 – 26 March 1980) was a senior British Army officer. He held battalion, brigade and divisional commands during the Second World War and immediately after, but is best known as the commander ...

's 27th British Commonwealth Brigade

The 27th Infantry Brigade was an infantry brigade of the British Army that saw service in the First World War, the Second World War, and the Korean War. In Korea, the brigade was known as 27th British Commonwealth Brigade due to the addition of Ca ...

, part of the force under the Commander-in-Chief United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

, General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

. On 5 October, the entire brigade was airlifted by the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

(USAF) from Taegu

Daegu (; ), formerly spelled Taegu and officially Daegu Metropolitan City (), is a city in southeastern South Korea. It is the third-largest urban agglomeration in South Korea after Seoul and Busan; the fourth-largest List of provincial-level ci ...

to Kimpo Air Base

Gimpo International Airport , sometimes referred to as Seoul–Gimpo International Airport but formerly rendered in English as Kimpo International Airport, is located in the far western end of Seoul, some west of the central district of Seou ...

outside Seoul, their vehicles driving the intervening and only arriving in Seoul on 9 October. The brigade then moved north under the operational control of the US 1st Cavalry Division.

The 27th British Commonwealth Brigade advanced towards Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

via Kaesong

Kaesong (, ; ) is a special city in the southern part of North Korea (formerly in North Hwanghae Province), and the capital of Korea during the Taebong kingdom and subsequent Goryeo dynasty. The city is near the Kaesong Industrial Region cl ...

, Kumchon ''Geumcheon'' () is a Korean-language term that may refer to:

Administrative divisions

* Geumcheon District in Seoul, South Korea

* Geumcheon-myeon, Cheongdo County in North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea

* in South Jeolla Province, South Ko ...

and Hungsu-ri to Sariwon

Sariwŏn (; ) is a city in North Korea. It is the capital and largest city of North Hwanghae Province.

Population

The city's population as of 2008 is 307,764.

Administrative divisions

Sariwŏn is divided into 31 '' tong'' (neighbourhoods) and ...

. Attached to Green's battalion were a platoon

A platoon is a Military organization, military unit typically composed of two to four squads, Section (military unit), sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the Military branch, branch, but a platoon can ...

of US M4 Sherman

The M4 Sherman, officially medium tank, M4, was the medium tank most widely used by the United States and Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman proved to be reliable, relatively cheap to produce, and available in great numbers. I ...

tanks and a US field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support army, armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the ear ...

battery

Battery or batterie most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

* Battery indicator, a device whic ...

. On 16 October, the brigade led the division towards the outskirts of Sariwon. During that and the following day, 3 RAR advanced from Kumchon to Sariwon, and entered that town on the evening of the 17th. In chaotic scenes, the brigade and elements of a KPA division both occupied the centre of town for some time. In one incident, Green's second-in-command, Major Ian Bruce Ferguson

Colonel Ian Bruce Ferguson, (13 April 1917 – 21 December 1988) was an officer in the Australian Army who served in the Second World War and Korean War.

Early life

Ferguson was born on 13 April 1917 in Wellington, New Zealand, the only c ...

, captured 1,600 North Koreans with just an interpreter, a loudspeaker and a tank. There was no rest for the brigade as it continued its push through Pyongyang to the village of Sangapo. To cut off KPA units retreating towards the Yalu River

The Yalu River () or Amnok River () is a river on the border between China and North Korea. Together with the Tumen River to its east, and a small portion of Paektu Mountain, the Yalu forms the border between China and North Korea. Its valle ...

, the US 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team

The 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment (Rakkasans) is a regiment of the 101st Airborne Division.

, the 1st and 3rd battalions are the only active elements of the regiment; they are assigned to the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Divisio ...

was parachuted around Yongju north of Pyongyang. The 27th British Commonwealth Brigade advanced almost to Yongju against minor opposition, and initial contact was made between the Commonwealth and US airborne forces on the evening of 21 October.

Battle of the Apple Orchard

Green's battalion was involved in its first major action on 22 October. The battle began as 3 RAR led the brigade north of Yongju when C Company and Green's battalion tactical headquarters following it were attacked from front and rear by a KPA force of around 1,000 soldiers. C Company aggressivelycounter-attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in " war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

ed, and while the KPA troops fought "with desperate bravery" and regrouped in an apple orchard to the east of the road, the Australians, supported by US tanks, quickly prevailed. By the time mopping up was completed, 3 RAR had suffered seven wounded, but had killed between 150 and 200 KPA troops and taken 239 prisoners. The battle was the first large-scale engagement fought by a battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment

The Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) is the parent administrative regiment for regular infantry battalions of the Australian Army and is the senior infantry regiment of the Royal Australian Infantry Corps. It was originally formed in 1948 as a t ...

, which had only been established on 23 November 1948. A US Army historian wrote that 3 RAR had fought "with a dash that brought forth admiration from all who witnessed it". Green has been credited with the excellent performance of the battalion in its first major action, Coad observing that he was "a fine fighting soldier, so quiet in his manner... he inspired confidence, both with his superiors and subordinates".

Battle of the Broken Bridge

Three days later, Green's battalion was again the brigadevanguard

The vanguard (sometimes abbreviated to van and also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

...

after it had crossed the Chongchon River

The Ch'ŏngch'ŏn is a river in North Korea having its source in the Rangrim Mountains of Chagang Province and emptying into the Yellow Sea at Sinanju. The river flows past Myohyang-san and through the city of Anju, South P'yŏngan Provi ...

and advanced towards Pakchon. When the lead elements of 3 RAR reached the Taeryong River

Taeryong River () is a river of North Korea. The river is a tributary of the Ch'ongch'on River.

See also

*Rivers of Korea

The Korean peninsula is mainly mountainous along its east coast, so most of its river water flows west, emptying into th ...

near Kujin it found KPA engineers had destroyed the centre span of the bridge. A reconnaissance patrol crossed the river using debris. When aerial reconnaissance identified KPA forces on the high ground, Green ordered the patrol to withdraw to the near side of the river, which they did, bringing ten prisoners with them. Airstrikes and the battalion mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a village i ...

were called in onto the KPA positions across the river, and Green ordered D Company to clear nearby Pakchon. Once this was achieved—D Company returned with 225 prisoners—he sent A and B Companies across the river to establish a bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

, commencing at 19:00. Using the broken bridge, the two companies crossed without KPA resistance and established positions on both sides of the road about north of the river, with A Company on the left and B Company on the right.

That night, the KPA made several concerted attacks on both forward companies, B Company suffering the worst. Green sent reinforcements from C Company across the river to bolster B Company. About 04:00 on 26 October, the KPA launched an attack on both forward companies supported by T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank from World War II. When introduced, its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was more powerful than many of its contemporaries, and its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against Anti-tank warfare, ...

tanks, but the level of coordination needed to push the Australians from the bridgehead was lacking, and while the KPA assault was renewed, by dawn the two companies remained in position. Airstrikes, including napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated aluminium ...

, were called in on the KPA elements holding the ridges north of the river, and late that morning the remaining rifle companies of 3 RAR joined the forward companies, and after a flanking effort by other elements of the brigade, the KPA withdrew. KPA casualties in the battle were 100 killed and 350 captured, Green's battalion suffering eight killed—its first fatalities of the war—and 22 wounded.

Battle of Chongju and death

The brigade continued its advance, and Green's battalion again took over the vanguard role on 29 October about from Chongju. Aerial reconnaissance indicated that a KPA force of around 500–600, supported by tanks andself-propelled gun

Self-propelled artillery (also called locomotive artillery) is artillery equipped with its own propulsion system to move toward its firing position. Within the terminology are the self-propelled gun, self-propelled howitzer, self-propelled mo ...

s (SPGs), had established well-constructed and camouflaged defensive positions on a thickly wooded ridgeline south of the town. A series of airstrikes was called in, and by 14:00 the USAF were claiming considerable success. With only a few hours of daylight left, Green ordered a battalion attack with D Company on the left of the road and A Company on the right, following an artillery bombardment.

The two companies attacked before dusk, D Company being supported by US tanks, and despite the heavy enemy fire, both secured their objectives on the ridge by 17:30. Eleven T-34 tanks and two

The two companies attacked before dusk, D Company being supported by US tanks, and despite the heavy enemy fire, both secured their objectives on the ridge by 17:30. Eleven T-34 tanks and two SU-76

The SU-76 ('' Samokhodnaya Ustanovka 76'') was a Soviet light self-propelled gun used during and after World War II. The SU-76 was based on a lengthened version of the T-70 light tank chassis and armed with the ZIS-3 mod. 1942 76-mm divisional ...

SPGs were destroyed by 3 RAR and the accompanying tanks, contrary to the reports of their destruction by USAF airstrikes earlier in the day. Green moved B Company up to occupy the road between the two assault companies, moved battalion headquarters in behind them, and held C and Support Companies in reserve at the rear. A hasty and limited resupply followed as the unit dug in.

The KPA counter-attacked in battalion strength following preparatory artillery fire beginning at 19:00, first against D Company. Although the North Koreans managed to overrun parts of the company position, counter-attacks restored the situation after two hours of fierce fighting. D Company was cut off from battalion headquarters for some time by infiltrating KPA troops, who were cleared away by Headquarters Company. A second assault fell on A Company, but it was beaten off in heavy fighting, the company commander calling in artillery within of his forward positions. The KPA withdrew about 22:15. In the morning, 150 dead KPA soldiers were found inside the 3 RAR perimeter. The total KPA casualties in the battle were 162 killed and ten captured, while Green's battalion suffered nine dead and 30 wounded. The fighting around Chongju was the heaviest undertaken by the Australians since they had entered the war.

The battalion moved forward to a reserve position on the Talchon River on 30 October, while other brigade elements cleared Chongju itself, securing it by 17:00. For protection, Green sited his battalion headquarters on the reverse slope, with the rifle companies on the forward slope. Around dusk at 18:10, six high-velocity shells, likely from a KPA SPG or tank, hit the battalion position. Five of the shells landed on the forward slope, while the sixth cleared the crest and detonated to the rear of the C Company position after hitting a tree. In his tent on a stretcher after 36 hours without sleep, Green was severely wounded in the abdomen by a fragment from the wayward round. He was evacuated to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital

Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH) were U.S. Army field hospital units conceptualized in 1946 as replacements for the obsolete World War II-era Auxiliary Surgical Group hospital units. MASH units were in operation from the Korean War to the ...

at Anju but succumbed to his wounds and died two days later on 1 November, aged 30. Forty other men who had been in the vicinity when the shell exploded were unhurt.

A popular and respected commanding officer, Green's loss was keenly felt by the Australians, and according to Barter, "cast a pall of gloom over his battalion". Ferguson, who was soon appointed to command 3 RAR, asserted that Green was "the best commander any man could ever have", and according to three officers that served with 3 RAR in Korea, he was one of the Australian Army's better unit-level commanders. Coad kept a photograph of Green in his study for the remainder of his life. Green remains the only commanding officer of a battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment to die on active service.

Legacy

Green was initially buried in the Christian churchyard at Pakchon on the day he died, but his body was soon exhumed and buried in the

Green was initially buried in the Christian churchyard at Pakchon on the day he died, but his body was soon exhumed and buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery

The United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Korea (UNMCK; ), located at Tanggok in the Nam District, Busan, Nam District,; also seeKorea 1:50,000 Pusan Sheet 7019 III (1947) an of Busan,As a transliteration from Korean, the city name 부산 () was ...

(UNMC) in Pusan. He was posthumously awarded the US Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

in June 1951. According to Barter, Green's career as a battalion commander in New Guinea and Korea had been "exemplary", and serving Australian soldiers were still inspired by it at the time she wrote his entry in 1996. A commemorative cairn

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehistory, t ...

was erected at the barracks of the 41st Battalion, Royal New South Wales Regiment, in Lismore, New South Wales

Lismore is a city located in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, Australia and the main population centre in the City of Lismore Local government in Australia, local government area, it is also a regional centre in the Northern River ...

, and as of 1996, a United Nations emblem was affixed to the gates of the Swan Creek farm where he grew up.

Green's wife, Olwyn, who survived him along with their daughter, wrote his biography, ''The Name's Still Charlie'', which was published in 1993 and republished in 2010. Following her death, Olwyn’s remains were buried with Green’s at the UNMC on 21 September 2023.

Notes

Footnotes

References

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Gazettes, unit diaries and websites

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Guide to the papers of Papers of Charles and Olwyn Green

Collection Number: PR00466, Australian War Memorial {{DEFAULTSORT:Green, Charles Hercules 1919 births 1950 deaths Military personnel from New South Wales Australian colonels Australian Army personnel of World War II Australian military personnel killed in the Korean War Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Foreign recipients of the Silver Star People from Grafton, New South Wales Burials at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery