Censorship in Italy applies to all media and print media. Many of the laws regulating

freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

in the modern

Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

come from the liberal reform promulgated by

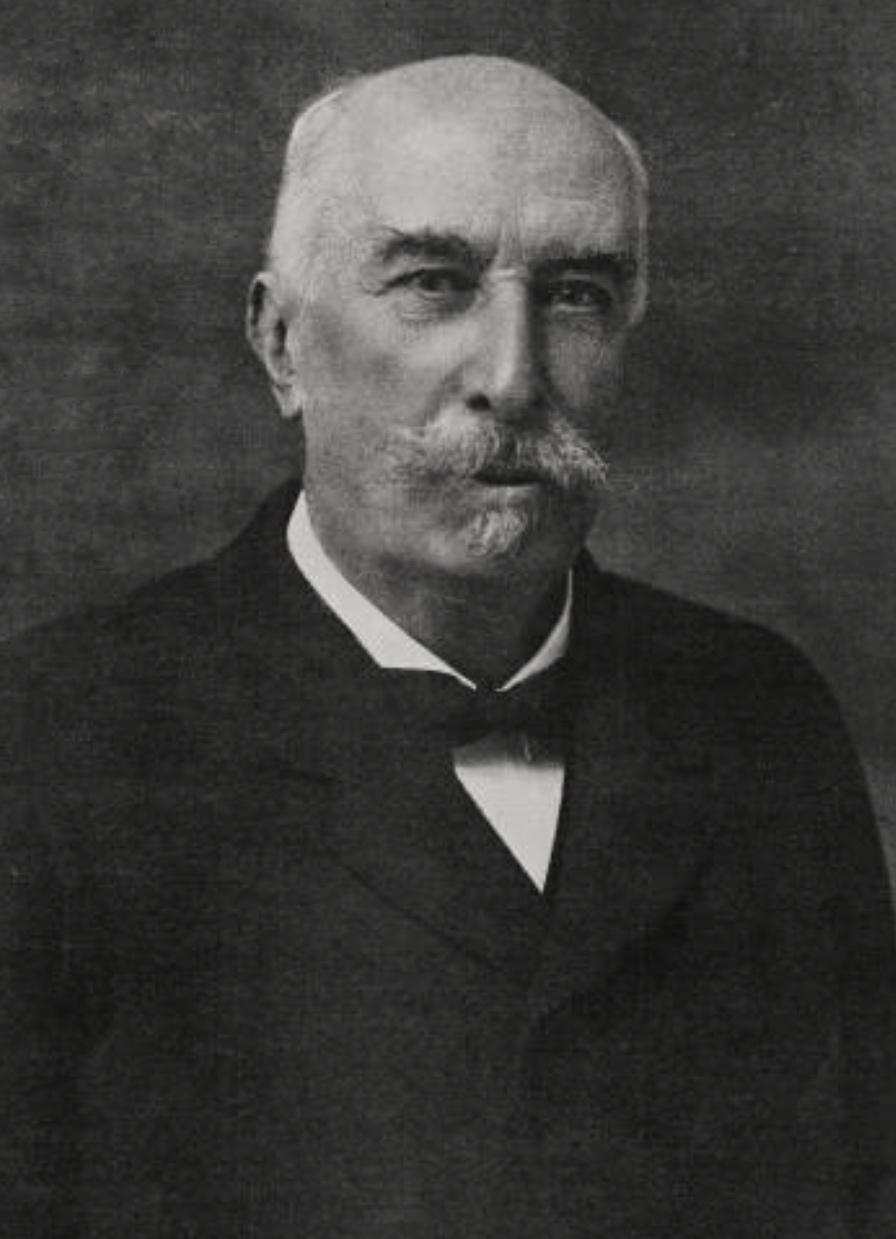

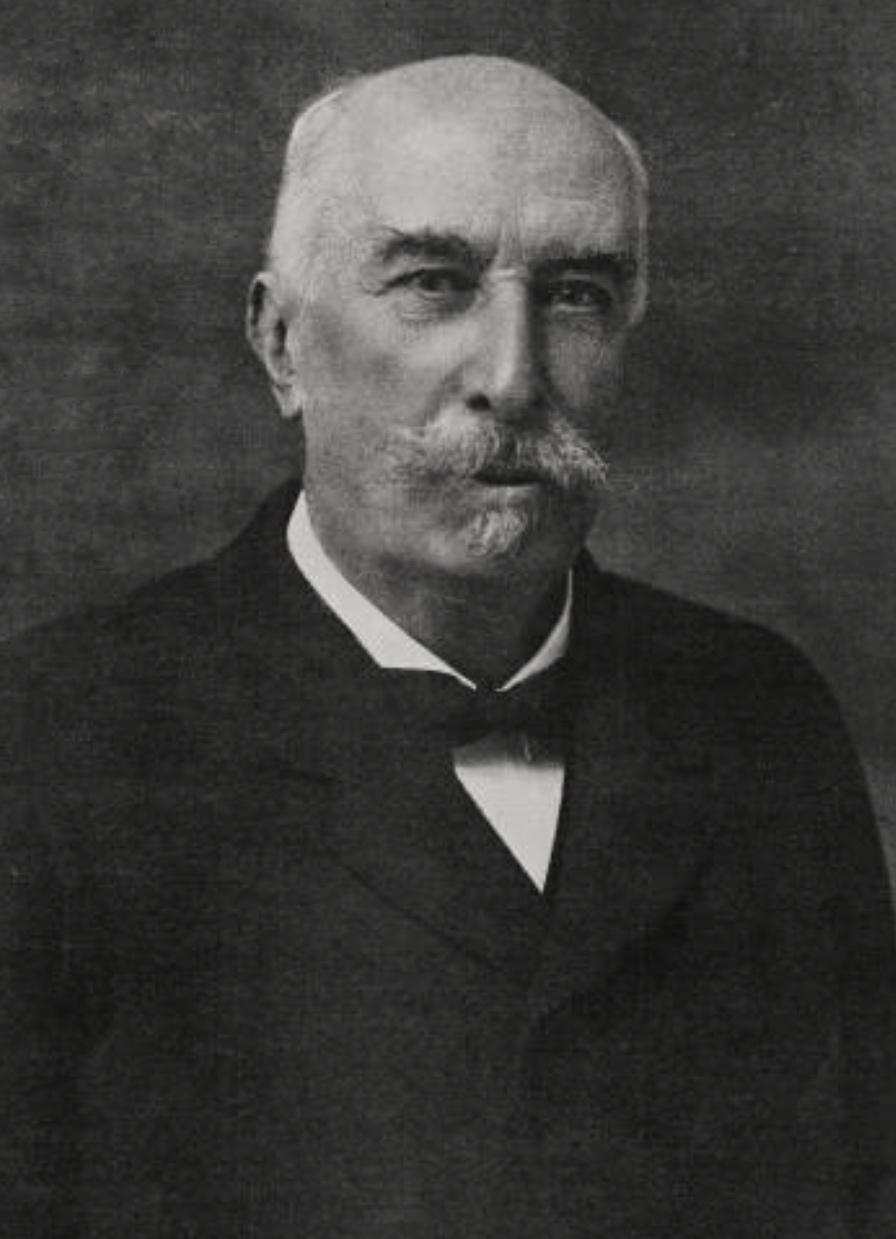

Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

in 1912, which also established

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

for all male citizens of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. Many of these liberal laws were repealed by the

Mussolini government already during the first years of government (think of the "ultra-fascist" laws of 1926).

In Italy, freedom of the press is guaranteed by the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

of 1948. This freedom was specifically established in response to the censorship which occurred during the fascist regime of

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

(1922–1943). Censorship continues to be an issue of debate in the modern era. In 2015,

Freedom House

Freedom House is a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. It is best known for political advocacy surrounding issues of democracy, Freedom (political), political freedom, and human rights. Freedom House was founded in October 1941, wi ...

classified the Italian press as "partly free", while in the report of the same year

Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB; ; RSF) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organisation, non-governmental organization headquartered in Paris, which focuses on safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its a ...

placed Italy in 73rd place in the world for freedom of the press.

Censorship during Italian unification (1814–1861)

During

Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

, in the period following the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

(1814–1815), incisive control over the press by the monarchies was in place on Italian territory. In the capitals of the various states, and in the most important urban centres, generally only one official sheet of the monarchy was issued, generally entitled Gazzetta, which was used for the publication of laws and carefully selected news.

In addition to these, however, there were literary and cultural periodicals, where new ideas could be expressed. In 1816, on the initiative of the Austrians, a literary monthly magazine entitled ''Biblioteca Italiana'' was founded in Milan, in which over 400 intellectuals and

men of letters from all over Italy were invited to collaborate (not always successfully). This magazine was counterbalanced by ''

Il Conciliatore

''Il Conciliatore'' was a progressive bi-weekly scientific and literary journal, influential in the early Risorgimento. The journal was published in Milan from September 1818 until October 1819 when it was closed by the Austrian censors. Its writ ...

'', a statistical-literary periodical close to the

romantic ideas of

Madame de Staël Madame may refer to:

* Madam, civility title or form of address for women, derived from the French

* Madam (prostitution), a term for a woman who is engaged in the business of procuring prostitutes, usually the manager of a brothel

* ''Madame'' ( ...

, which continued to appear until 1819 when it was forced to close.

The situation of Italian journalism began to change with the foundation of numerous clandestine newspapers, printed by Carbonari nuclei and underground revolutionary movements, which led to the

uprisings of 1820–1821. One of the best-known newspapers of this period is ''L'Illuminismo'', published in the

Papal Legations

The delegations as they existed in 1859

Between the Congress of Vienna (1815) and the capture of Rome (1870), the Papal State was subdivided geographically into 17 apostolic delegations (''delegazioni apostoliche'') for a ...

in 1820, along with ''La Minerva'' of Naples and ''La Sentinella Subalpina'' of Turin. In the same period, there was also a certain journalistic activism in Italian liberal circles. In fact, ''Antologia'', a journal of science, literature and arts, founded in Florence in 1821, the Genoese ''Corriere Mercantile'' of 1824 and ''L'Indicatore genovese'', to which the young

Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

also collaborated, date back to those years.

Changes regarding

freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

occurred in 1847 and 1848 during the

popular uprisings that occurred in those years, following new measures:

* Edict of

Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

of 15 March 1847;

* Law of

Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, of 6 May 1847;

* Edict of King

Charles Albert of Sardinia

Charles Albert (; 2 October 1798 – 28 July 1849) was the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), King of Sardinia and ruler of the Savoyard state from 27 April 1831 until his abdication in 1849. His name is bound up with the first Italian constit ...

of 26 March 1848;

* Decree of King

Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand II (; ; ; 12 January 1810 – 22 May 1859) was King of the Two Sicilies from 1830 until his death in 1859.

Family

Ferdinand was born in Palermo to King Francis I of the Two Sicilies and his second wife Maria Isabella of Spain. ...

of 29 January 1848.

These measures had the effect of limiting preventive censorship of the press.

In Florence the following were published: ''La Zanzara'' (1849); ''La Frusta'' (1849); ''Il Popolano'' (1848–1849); ''L'Arte'' (1848–1859) in which

Carlo Collodi

Carlo Lorenzini (; 24 November 1826 – 26 October 1890), better known by the pen name Carlo Collodi ( ; ), was an Italian author, humourist, and journalist, widely known for his fairy tale novel '' The Adventures of Pinocchio''.

Early lif ...

collaborated, ''Buon gusto'' (1851–1864); La Speranza (1851–1859); ''Etruria'' (1851–1852); ''Il Genio'' (23 December 1852–31 June 1854); ''Lo Scaramuccia'' (1853–1859); ''La Polimazia di famiglia'' (1854–1856); ''L'Eco d'Europa'' (1854–1856); ''L'Eco dei Teatri'' (1854–1856); ''L'Indicatore Teatrale'' (1855–1858); ''L'Avvisatore'' (1856–1859); ''L'Imparziale'' (1856–1867); ''Lo Spettatore'' (1855–59); ''Il Passatempo'' (1856–1858); ''La Lanterna di Diogene'' (1856–1859); ''La Lente'' (1856–1861) in which Carlo Collodi collaborated; ''L'Arlecchino'' (1858); ''Il Caffè'' (1858); ''Il Carlo Goldoni'' (1858); ''Piovano Arlotto'' (1858–1862); and ''Il Poliziano'', from January to June 1859.

The

Agenzia Stefani Agenzia Stefani was the leading press agency in Italy from the mid-19th century until the end of World War II. It was founded by Guglielmo Stefani on 26 January 1853 in Turin, and was closed on 29 April 1945 in Milan.

History

Early years

''Tel ...

was founded in 1853 in Turin by

Guglielmo Stefani. In Genoa in 1860, at the instigation of Giuseppe Mazzini, ''L'Unità Italiana'' was founded. In the wake of the

Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand () was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Ki ...

, the following were founded in the same year: ''L'Ineditore'' in Palermo and in Naples the Mazzinian ''Il Popolo d'Italia''.

Censorship in liberal Italy (1861–1922)

Many of the laws regulating freedom of the press in the modern

Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

come from the liberal reform promulgated by

Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

in 1912, which also established

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

for all male citizens of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. Many of these liberal laws were repealed by the

Mussolini government already during the first years of government.

The first law that introduced a real censorship intervention in the

unified Italy was the one relating to cinema screenings and dates back to 1913. With this law the representation of obscene or shocking shows or those contrary to decency, decorum, public order and the prestige of institutions and authorities was prevented. The subsequent regulation, issued in 1914, listed a long series of prohibitions and transferred the power of intervention from the local public security authorities to the

Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry or ministry of the interior (also called ministry of home affairs or ministry of internal affairs) is a government department that is responsible for domestic policy, public security and law enforcement.

In some states, the ...

. In 1920, with a Royal Decree, a commission was established, which among other things had the task of preventively viewing the film script before filming began.

On 23 May 1915, during

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, with decrees nos. 674, 675 and 689, censorship of the press and mail was established. Newspapers cannot provide information on the number of wounded, prisoners and fallen, on appointments and changes in military high command, other than that contained in official press releases.

Some changes were introduced to the public security law; the prefects have the power to order the seizure of a newspaper and its suspension after two subsequent seizures.

For the entire duration of the war, the authorities responsible for controlling the press, eager to present an optimistic picture of the situation to the public, suggested to the newspapers how to select the news. The pressure from the authorities, combined with the expectations of the public, who wanted to read only positive news in the newspapers, caused the Italian press to self-censor.

The newspapers, despite receiving well-detailed news from the front from their war correspondents, did not publish everything. They voluntarily concealed part of the news from the reading public, publishing articles that hid, and in some cases falsified, much of the truth. On 19 November 1918, after the end of the war, the causes of seizure of periodic publications were limited to information of a military nature and untruthful news that could cause alarm in public opinion or disturb international relations. With the decree of 29 June 1919, the restrictive regulations that came into force in the spring of 1915 were repealed; at the same time, the general director of public security, Vincenzo Quaranta, reduced surveillance on the media.

Censorship in Italy under Fascism (1922–1943)

Censorship in Italy was not created with

Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, nor did it end with it, but it had a heavy influence in the life of Italians under the Regime.

The main goals of censorship under fascism were, concisely:

*Control over the public appearance of the regime, also obtained with the deletion of any content that could allow opposition, suspicions, or doubts about fascism.

*Constant check of the public opinion as a measure of

consensus.

*Creation of national and local archives (''schedatura'') in which each citizen was filed and classified depending on their ideas, habits, relationships and any shameful acts or situations which had arisen; in this way, censorship was used as an instrument for the creation of a

police state

A police state describes a state whose government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the exec ...

.

Censorship fought ideological and defeatist contents, and any other work or content that would not enforce nationalist fascism.

Censorship in public communications

This branch of the activity was mainly ruled by the ''Ministero della Cultura Popolare'' (

Ministry of popular culture), commonly abbreviated as "Min. Cul. Pop.". This administration had authority over all the contents that could appear in newspapers, radio, literature, theatre, cinema, and generally any other form of communication or art.

In literature, editorial industries had their own controlling servants steadily on site, but sometimes it could happen that some texts reached the libraries and in this case, an efficient organization was able to capture all the copies in a very short time.

On the issue of censoring foreign language use, the idea of

autarky

Autarky is the characteristic of self-sufficiency, usually applied to societies, communities, states, and their economic systems.

Autarky as an ideology or economic approach has been attempted by a range of political ideologies and movement ...

effectively banned foreign languages, and any attempt to use a non-Italian word resulted in a formal censoring action. Reminiscences of this ban could be detected in the

dubbing

Dubbing (also known as re-recording and mixing) is a post-production process used in filmmaking and the video production process where supplementary recordings (known as doubles) are lip-synced and "mixed" with original production audio to cr ...

of all foreign movies broadcast on

RAI (Italian state owned public service broadcaster):

captioning is very rarely used.

Censorship did not however impose heavy limits on foreign literature, and many works by foreign authors were freely readable. Those authors could freely frequent Italy and even write about it, with no reported troubles.

In 1930, it was forbidden to distribute books that contained

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

,

Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

or Anarchist like ideologies, but these books could be collected in public libraries in special sections not open to the general public. The same happened for the books that were sequestrated. All these texts could be read under authorization for scientific or cultural purposes, but it is said that this permission was quite easy to obtain. In 1938, there were public

bonfire

A bonfire is a large and controlled outdoor fire, used for waste disposal or as part of a religious feast, such as Saint John's Eve.

Etymology

The earliest attestations date to the late 15th century, with the Catholicon Anglicum spelling i ...

s of forbidden books, enforced by fascist militias ("

camicie nere"). Any work containing themes about Jewish culture, freemasonry, communist, or socialist ideas, was removed also by libraries (but it has been said that effectively the order was not executed with zeal, being a very unpopular position of the Regime).

Censorship and press

It has been said that the Italian press censored itself before the censorship commission could do it. Effectively the actions against the press were formally very few, but it has been noted that due to press hierarchical organization, the regime felt to be quite safe, controlling it by the direct naming of directors and editors through the ''"

Ordine dei Giornalisti"''.

Most of the intellectuals, who after the war would have freely expressed their

anti-fascism

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

, were however journalists during fascism, and quite comfortably could find a way to work in a system in which news directly came from the government.

Newer revisionists talk about the servility of journalists, but are surprisingly followed in this concept by many other authors and by some leftist ones too, since the same suspect was always attributed to the Italian press, before, during and after the Ventennio, and still in recent times the category has not completely demonstrated yet its independence from "strong powers". A well-known Italian journalist writer,

Ennio Flaiano, certainly an anti-fascist, used to say that journalists do not need to care of "that irrelevant majority of Italians".

Independent (illegal) press used clandestine print and distribution and were mainly connected with the activities of local political groups.

The control of legitimate papers was practically operated by faithful civil servants at the printing machines and this allowed reporting a common joke affirming that any text that could reach readers had been "written by the ''Duce'' and approved by the foreman".

Fascist censorship promoted papers with wider attention to mere chronology of delicate political moments, to distract public opinion from dangerous passages of the government. Press then focused on other terrifying figures (murderers, serial killers, terrorists, paedophiles, etc.). When needed, an image of a safe ordered State was instead to be stressed, then police were able to capture all the criminals and, as a famous topic says, trains were always in perfect time. All these manoeuvres were commonly directed by MinCulPop directly.

After fascism, the democratic republic did not change the essence of the fascist law on press, which is now organized as it was before, like the law on access to the profession of journalist remained unaltered.

About satire and related press, Fascism was not more severe, and in fact, a famous magazine, ''

Marc'Aurelio'', was able to operate with little trouble. In 1924–1925, during the most violent times of fascism (when squads used brutality against opposition) with reference to the death of

Giacomo Matteotti

Giacomo Matteotti (; 22 May 1885 – 10 June 1924) was an Italian socialist politician and secretary of the Unitary Socialist Party (PSU). He was elected deputy of the Chamber of Deputies three times, in 1919, 1921 and in 1924. On 30 May 19 ...

killed by fascists, ''Marc'Aurelio'' published a series of heavy jokes and "comic" drawings describing dictator

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

finally distributing peace. Marc'Aurelio however would have turned to a more integrated tone during the following years and in 1938 (the year of the racial laws) published tasteless anti-Semitic content.

Censorship in private communications

Quite obviously, any telephone call was at risk of being intercepted and, sometimes, interrupted by censors.

Not all the letters were opened, but not all those read by censors had the regular stamp that recorded the executed control. Most of the censorship was probably not declared, to secretly consent to further police investigations.

Chattering ''en plein air'' was indeed very risky, as a special section of investigators dealt with what people were saying on the roads; an eventual accusation by some policeman in disguise was evidently very hard to disprove and many people reported having been falsely accused of anti-national sentiments, just for personal interests of the spy. Consequently, after the first cases, people commonly avoided talking publicly.

Military censorship

The greatest amount of documents about fascist censorship came from the military commissions for censorship. The military censorship commissions compiled the opinions and feelings of the soldiers at the front in a note, which was received daily by Mussolini or his apparatus.

This was due to several factors. The war had brought many Italians far from their homes, creating a need for writing to their families that previously did not exist. In a critical situation such as war, military authorities were compelled to control eventual internal oppositions, spies or defeatists. Finally, the result of the war could not allow fascists to hide or delete these documents or remain in public offices where they could be found by occupying troops.

Italians' reaction against censorship

The fact that Italians were well aware that any communication could be intercepted, recorded, analyzed and eventually used against them, caused censorship, in time, to become a sort of usual rule to consider, and soon most people used jargon or other conventional systems to overtake the rules.

In most of the small villages, life continued as before, since the local authorities used a very familiar style in executing such orders. Also in many urban realities, civil servants used little zeal and more humanity. But the general effect was indeed relevant.

In theatre, censorship caused a revival of "canovaccio" and Commedia dell'arte given that all the stories had to obtain prior permission before being performed.

Censorship during the Italian Civil War (1943–1945)

Fascism fell during the third year of the war, 1943. In July the Allies began the liberation of Italy by

landing in Sicily. A few weeks later, on 25 July, the Mussolini regime fell, triggering the start of the

Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (, ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during the Liberation of Italy, Italian campaign of World War II between Italian fascists and Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically organized ...

. The effect on Italian newspapers was immediate. All editors who were members of the

National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party (, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of It ...

, or militants, were dismissed and replaced. Just 45 days later Germany invaded Italy and there was a new change. All newspapers in Northern Italy remained under Nazi-Fascist control until April 1945.

The new Prime Minister, General

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

, instead of suppressing the

Ministry of Popular Culture, suspended its activities and used it to transmit new orders aimed at controlling the press. The decree of 9 August 1943, n. 727, dictated very restrictive rules on freedom of the press:

* Any transfer of ownership of a newspaper or periodical had to have the approval of the Ministry of Popular Culture;

* The appointment of the director responsible for newspapers or periodicals had to be authorized by the said ministry;

* News agencies that received state contributions or subsidies were required to submit accounting records upon request from the ministry itself.

The effects of the decree ceased less than a month later, with the unconditional surrender to the Allies. The

Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

, signed on 3 September 1943, in fact, contained rules regarding the regulation of the press:

* Control of the radio, communications and transceiver systems passed to the Allies. The media would also be under the control and subject to authorization of the Allied Command (art. 16);

* All newspapers compromised with the

Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

ceased publication: the factories would have been seized pending closure or a change of name and editorial line.

* The armistice also provided for the restoration of the most basic freedoms of thought and expression prohibited by the past regime. The Act in fact sanctioned the suppression of the spread of fascist ideology and teaching and the dissolution of its institutions and organizations, especially military, paramilitary, espionage and propaganda (art. 30).

* Likewise, all Italian laws involving discrimination based on race, colour, faith or political opinion were abolished and any impediment or prohibition resulting from them was eliminated, and the release of anyone who had been deprived of freedom or these rights due to such laws (art. 31).

Writers, journalists, playwrights and political exponents whose work had been prohibited, interdicted or forced underground by censorship and the abolition of the freedom of the press during the years of fascism resumed writing and publishing articles, books and other literary productions.

In the same period, the Allies increased the hours of

Radio Londra programming that could be received in Northern Italy. In 1943 they reached the duration of 4 hours and 15 minutes. Radios were also used to send coded messages, passwords and other communications to fighters in areas still in conflict or under Nazi-Fascist occupation.

Starting in 1944, the reorganization of executive power between central and peripheral bodies began in liberated Italy. The decrees no. 13 and 14 of 14 January 1944 assigned the prefects the power to grant printing licenses and established the obligation for publishers to report stocks of paper and printing materials. With the legislative decree of 31 May 1946, n. 561, the rules of the past regime on the seizure of publications were cancelled and the pre-existing situation was returned.

Censorship in the modern Italian Republic (1946–present)

One of the most important cases of censorship in Italy was the banning of one episode of the TV show ''

Le Iene'' showing use of

cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

in the Italian Parliament.

As with all the other

media of Italy, the Italian television industry is widely considered both inside and outside the country to be overtly

politicized

Politicisation (also politicization; see English spelling differences) is a concept in political science and theory used to explain how ideas, entities or collections of facts are given a political tone or character, and are consequently assigned ...

. According to a December 2008 poll, only 24% of Italians trust television

news programmes, compared unfavourably to the British rate of 38%, making Italy one of only three examined countries where online sources are considered more reliable than television ones for information.

Italy put an

embargo

Economic sanctions or embargoes are commercial and financial penalties applied by states or institutions against states, groups, or individuals. Economic sanctions are a form of coercion that attempts to get an actor to change its behavior throu ...

on foreign

bookmaker

A bookmaker, bookie, or turf accountant is an organization or a person that accepts and pays out bets on sporting and other events at agreed-upon odds

In probability theory, odds provide a measure of the probability of a particular outco ...

s over the Internet (in violation of EU market rules) by mandating certain edits to DNS host files of Italian ISPs. Italy also blocks access to websites containing child pornography.

Advertisements promoting ''

Videocracy'', a Swedish documentary examining the influence of television on Italian culture over the last 30 years, was refused airing purportedly because it says the spots are an offence to Premier

Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

.

Films, anime and cartoons are often modified or cut on national television networks such as

Mediaset

Mediaset S.p.A. is an Italian mass media and television production and distribution company that is the largest commercial broadcaster in the country. The company is controlled by the holding company MFE – MediaForEurope (the original ...

or

RAI. An example of this occurred in December 2008, when ''

Brokeback Mountain

''Brokeback Mountain'' is a 2005 American neo-Western romantic drama film directed by Ang Lee and produced by Diana Ossana and James Schamus. Adapted from Brokeback Mountain (short story), the 1997 short story by Annie Proulx, the screenplay ...

'' was aired on

Rai 2

Rai 2 is an Italian free-to-air television channel owned and operated by state-owned public broadcaster RAI – Radiotelevisione italiana. It is the company's second television channel, and is known for broadcasting '' TG2'' news bulletins, ta ...

during primetime. Several scenes featuring mildly sexual (or even just romantic) behaviour of the two protagonists were cut. This act was severely criticized by Italian LGBT activist organizations and others.

Guareschi case

In 1950 a cartoon published in ''

Candido'' (n. 25 of 18 June), drawn by Carletto Manzoni, cost

Giovannino Guareschi

Giovannino Oliviero Giuseppe Guareschi (; 1 May 1908 – 22 July 1968) was an Italian journalist, cartoonist, and humorist whose best known creation is the priest Don Camillo and Peppone, Don Camillo.

Life and career

Guareschi was born into a ...

, co-director of the weekly at the time, his first conviction for contempt of the

President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

,

Luigi Einaudi

Luigi Numa Lorenzo Einaudi (; 24 March 1874 – 30 October 1961) was an Italian politician, economist and banker who served as President of Italy from 1948 to 1955 and is considered one of the founding fathers of the 1946 Italian institutional ...

. The cartoon, entitled ''Al Quirinale'', depicted a double row of bottles with, at the bottom, the figurine of a man with a stick, like a great officer reviewing two groups of

Corazzieri ("The Corazzieri" was the caption of the cartoon). ''Candido'' had highlighted the fact that Einaudi, on the labels of the wine he produced (a

Nebbiolo

Nebbiolo (, ; ) is an Italian red wine grape variety predominantly associated with its native Piedmont region, where it makes the ''Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita'' (DOCG) wines of Barolo, Barbaresco, Gattinara, Ghemme, a ...

), allowed his public office as President of Italy to be highlighted. The bottle of wine, in fact, had "Nebbiolo, the President's wine" on the label. There were also other cartoons, besides the ''Al Quirinale'' one, such as that of the

Giro d'Italia

The Giro d'Italia (; ), also known simply as the Giro, is an annual stage race, multiple-stage bicycle racing, bicycle race primarily held in Italy, while also starting in, or passing through, other countries. The first race was organized in 19 ...

with the motto "Toast Einaudi!" or the little man who had the "bottle of Damocles" on his head. Sentenced to eight months in prison, the execution of the sentence was suspended as Guareschi had no criminal record.

Cinema

With the

birth of the Italian Republic, as regards film censorship, no substantial changes were introduced compared to the censorship provided for by the laws approved during the fascist regime, despite Article 21 of the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

allowing freedom of the press and all forms of expression. Under pressure mainly from the Catholic world, the paragraph was added which establishes a ban on shows and all other demonstrations contrary to morality. A central office for cinematography was established at the

Presidency of the Council, where the opinions of the first and second-degree commissions converged, essentially remaining those of 1923, even if slightly changed in their composition.

In 1949 a law was issued, presented by the then undersecretary for entertainment

Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti ( ; ; 14 January 1919 – 6 May 2013) was an Italian politician and wikt:statesman, statesman who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy in seven governments (1972–1973, 1976–1979, and 1989–1992), and was leader of th ...

, which was supposed to support and promote the growth of

Italian cinema

The cinema of Italy (, ) comprises the films made within Italy or by List of Italian film directors, Italian directors. Since its beginning, Italian cinema has influenced film movements worldwide. Italy is one of the birthplaces of art cinema and ...

and at the same time slow down the advance of American films, but also the embarrassing "excesses" of

Italian neorealism

Italian neorealism (), also known as the Golden Age of Italian Cinema, was a national film movement characterized by stories set amongst the poor and the working class. They are filmed on location, frequently with non-professional actors. They p ...

(which remained famous in this regard his statement according to which "Dirty laundry is washed in the family"). Following this rule, the screenplay had to be approved by a state commission before it could receive public funding. Furthermore, if it was believed that a film defamed Italy, the export license could be denied.

In 1962, a new law on the review of films and theatrical works was approved, which remained in force until 2021: although it brought about some changes, it confirmed the maintenance of a preventive system of censorship and made screening subject to the release of authorization. publishes films and exports them abroad. Based on this law, the opinion on the film was expressed by a specific first-level Commission (and by a second-level one for appeals), while the authorization was issued by the Ministry of Tourism and Entertainment (established in 1959).

In addition to total censorship, from the 1930s to the 1990s another form of censorship was in vogue in Italy, that of targeted cuts. In practice, it was customary to cut the parts of the film that were not wanted to be shown, while still allowing the manipulated film to be shown. On 5 April 2021, the total abolition of film censorship in Italy was announced.

Music

Immediately after the end of World War II, with the rise to power of the

Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

, censorship of music targeted references that could cause disturbance. Thus religion is the object of censorship, a particularly sensational case of ''Dio è morto'' ("God is dead") sung by

Nomadi, which is censored by

RAI but regularly broadcast by

Vatican Radio

Vatican Radio (; ) is the official broadcasting service of Vatican City.

Established in 1931 by Guglielmo Marconi, today its programs are offered in 47 languages, and are sent out on short wave, DRM, medium wave, FM, satellite and the Internet. ...

.

Another sensitive topic is sex, the object of particularly ferocious censorship, as happens for example in the case of ''

Je t'aime... moi non-plus'', sung by

Serge Gainsbourg

Serge Gainsbourg (; born Lucien Ginsburg; 2 April 1928 – 2 March 1991) was a French singer-songwriter, actor, composer, and director. Regarded as one of the most important figures in French pop, he was renowned for often provocative rel ...

and

Jane Birkin

Jane Mallory Birkin ( ; 14 December 1946 – 16 July 2023) was a British and French actress, singer, and designer. She had a prolific career as an actress, mostly in French cinema.

A native of London, Birkin began her career as an actress, ...

in 1969, a record which was seized and its sale permanently prohibited.

The Catholic "censorship" began to loosen in the second half of the 1970s, however, numerous censorships continued to be practised in the following decades.

The "Report" case

In 2009, the board of state television RAI cut funds for legal assistance to the investigative journalism TV programme ''

Report

A report is a document or a statement that presents information in an organized format for a specific audience and purpose. Although summaries of reports may be delivered orally, complete reports are usually given in the form of written documen ...

'' (aired by

Rai 3

Rai 3 (formerly Rai Tre) is an Italian free-to-air television channel owned and operated by state-owned public broadcaster RAI – Radiotelevisione italiana. It was launched on 15 December 1979 and its programming is centred towards cultural a ...

, a state-owned channel). The program had tackled sensitive issues in the past that exposed the journalists to legal action (for example the authorization of buildings that did not meet earthquake-resistance specifications, cases of overwhelming bureaucracy, the slow process of justice, prostitution, health care scandals, bankrupt bankers secretly owning multimillion-dollar paintings, waste mismanagement involving

dioxin toxic waste, cancers caused by

asbestos

Asbestos ( ) is a group of naturally occurring, Toxicity, toxic, carcinogenic and fibrous silicate minerals. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous Crystal habit, crystals, each fibre (particulate with length su ...

anti-fire shielding (

Eternit

Eternit is a registered trademark for a brand of fibre cement currently owned by the Belgian company Etex. Fibre is often applied in building and construction materials, mainly in roofing and facade products.

Material description

The term ...

) and environmental pollution caused by a coal

power station

A power station, also referred to as a power plant and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility for the electricity generation, generation of electric power. Power stations are generally connected to an electr ...

near the city of

Taranto

Taranto (; ; previously called Tarent in English) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Taranto, serving as an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base.

Founded by Spartans ...

). An accumulation of lawsuits against the journalists in the absence of the funds to handle them could bring the program to an end.

"Freedom of the Press" report

Before 2004, in the "Freedom of the Press" report, published by the American organization Freedom House, Italy had always been classified as "Free" (regarding the freedom of the press). In 2004, it was demoted to "Partly Free", due to "20 years of failed political administration", the "controversial Gasparri's Law of 2003" and the "possibility for prime minister to influence the RAI (Italian state-owned Radio-Television), a

conflict of interest

A conflict of interest (COI) is a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple wikt:interest#Noun, interests, financial or otherwise, and serving one interest could involve working against another. Typically, this relates t ...

s among the most blatant in the World".

Italy's status was upgraded to "free" in 2007 and 2008 under the

Prodi II Cabinet, to come back as "partly free" in 2009 with the

Berlusconi IV Cabinet

The fourth Berlusconi government was the 60th Cabinet (government), government of Politics of Italy, Italy, in office from 8 May 2008 to 16 November 2011. It was the fourth government led by Silvio Berlusconi, who then became the longest-serving ...

. Freedom House noted that Italy constitutes "a regional outlier" and particularly quoted the "increased government attempts to interfere with editorial policy at state-run broadcast outlets, particularly regarding coverage of scandals surrounding prime minister Silvio Berlusconi." In their 2011 report, Freedom House continued to list Italy as "partly free" and ranked the country 24th out of 25 in the Western European region, ahead of

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. In 2020 Italy was listed again in The Freedom House report as Free.

Anti-defamation actions

Defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

is a crime in Italy with the possibility of large fines and/or prison terms. Thus anti-defamation actions may intimidate reporters and encourage

self-censorship Self-censorship is the act of censoring or classifying one's own discourse, typically out of fear or deference to the perceived preferences, sensibilities, or infallibility of others, and often without overt external pressure. Self-censorship is c ...

.

In February 2004, the journalist Massimiliano Melilli was sentenced to 18 months in prison and a €100,000 fine for two articles, published on 9and 16 November 1996, that reported rumours of "erotic parties" supposedly attended by members of Trieste high society.

In July, magistrates in Naples placed

Lino Jannuzzi, a 76-year-old journalist and senator, under house arrest, although they allowed him the possibility of attending the work of the parliament during daytime. In 2002, he was arrested, found guilty of "defamation through the press" ("diffamazione a mezzo stampa"), and sentenced to 29 months' imprisonment because of articles that appeared in a local paper for which he was editor-in-chief. The articles revealed the irresponsible operation of the judiciary and highlighted what Jannuzzi called wrong and unjust sentences. Therefore, it was widely perceived that his sentence was given as revenge by the judiciary. Following heavy criticism from home and abroad, in February 2005, Italian

President Ciampi pardoned Jannuzzi.

Mediaset and Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

's extensive control over the media has been widely criticised by both analysts and press freedom organisations, who allege Italy's media has limited freedom of expression. The ''Freedom of the Press 2004 Global Survey'', an annual study issued by the American organization

Freedom House

Freedom House is a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. It is best known for political advocacy surrounding issues of democracy, Freedom (political), political freedom, and human rights. Freedom House was founded in October 1941, wi ...

, downgraded Italy's ranking from 'Free' to 'Partly Free' due to Berlusconi's influence over RAI, a ranking that, in "Western Europe" was shared only with Turkey ().

Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB; ; RSF) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organisation, non-governmental organization headquartered in Paris, which focuses on safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its a ...

states that in 2004, "The conflict of interests involving prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and his vast media empire was still not resolved and continued to threaten news diversity". In April 2004, the

International Federation of Journalists

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) is the largest global union federation of journalists' trade unions in the world. It represents more than 600,000 media workers from 187 organisations in 146 countries.

The IFJ is an associate ...

joined the criticism, objecting to the passage of a law vetoed by

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician, statesman and banker who was the President of Italy from 1999 to 2006 and the Prime Minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994.

A World War II veteran, C ...

in 2003, which critics believed was designed to protect Berlusconi's reported 90% control of the Italian television system.

"Editto Bulgaro"

Berlusconi's influence over RAI became evident when in

Sofia, Bulgaria

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

he expressed his views on journalists

Enzo Biagi and

Michele Santoro, and comedian

Daniele Luttazzi. Berlusconi said that they "use television as a criminal means of communication". They lost their jobs as a result. This statement was called by critics "''

Editto Bulgaro''".

The TV broadcasting of a satirical program called ''

RAIot – Armi di distrazione di massa'' (''Raiot-Weapons of mass distraction'', where "Raiot" is a mangling of

RAI which sounds like the English riot) was censored in November 2003 after the comedian

Sabina Guzzanti

Sabina Guzzanti (born 25 July 1963) is an Italian satire, satirist, actress, writer, and producer whose work is devoted to examining social and political life in Italy.

Early life

Born in Rome as the eldest daughter of celebrated Italian Pundit ...

(daughter of

Paolo Guzzanti

Paolo Guzzanti (born 1 August 1940) is an Italian journalist and politician.

Early life

Born in Rome, Guzzanti is the nephew of Elio Guzzanti and father to actors Corrado, Sabina, and Caterina. As a journalist, he worked for '' Avanti!'', '' ...

, former senator of

Forza Italia

(FI; ) was a centre-right liberal-conservative political party in Italy, with Christian democratic,Chiara Moroni, , Carocci, Rome 2008 liberalOreste Massari, ''I partiti politici nelle democrazie contempoiranee'', Laterza, Rome-Bari 2004 (esp ...

) made outspoken criticism of the Berlusconi media empire.

''Par condicio''

Mediaset

Mediaset S.p.A. is an Italian mass media and television production and distribution company that is the largest commercial broadcaster in the country. The company is controlled by the holding company MFE – MediaForEurope (the original ...

, Berlusconi's television group, has stated that it uses the same criteria as the public (state-owned) television

RAI in assigning proper visibility to all the most important political parties and movements (the so-called ''par condicio'', Latin for 'equal treatment' or '

Fairness Doctrine')—which has been since often disproved.

On 24 June 2009, during the

Confindustria

The General Confederation of Italian Industry (), commonly known as Confindustria, is the Italy, Italian small, medium, and big enterprises federation, acting as a private and autonomous chamber of commerce, founded in 1910. The association netwo ...

young members congress in

Santa Margherita Ligure, Italy, Silvio Berlusconi invited advertisers to interrupt or boycott advertising contracts with the magazines and newspapers published by

Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso

GEDI Gruppo Editoriale S.p.A., formerly known as S.p.A., is an Italian media conglomerate. Founded in 1955, it is based in Turin, Italy, and controlled by the Agnelli family through Exor. The company is known for publishing newspapers ''La Re ...

,

in particular the newspaper ''

la Repubblica

(; English: "the Republic") is an Italian daily general-interest newspaper with an average circulation of 151,309 copies in May 2023. It was founded in 1976 in Rome by Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso (now known as GEDI Gruppo Editoriale) and l ...

'' and the news-magazine ''

L'espresso

() is an Italian progressive weekly news magazine. It is one of the two most prominent Italian weeklies; the other is the conservative magazine . Since 2022, it has been published by BFC Media. From 7 August 2016 to 10 September 2023, it was ...

'', calling the publishing group "shameless"

for fueling the economic crisis by bringing attention to it. He also accused them of making a "subversive attack" against him.

The publishing group announced possible legal proceedings against Berlusconi to protect the image and the interests of the group.

In October 2009,

Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB; ; RSF) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organisation, non-governmental organization headquartered in Paris, which focuses on safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its a ...

Secretary-General

Jean-François Julliard declared that Berlusconi "is on the verge of being added to our list of Predators of Press Freedom", which would be a first for a European leader. In the event, Berlusconi was not declared a Predator of Press Freedom, but RWB continued to warn of "the continuing

concentration of media ownership

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', '' molar concentration'', '' number concentration'', ...

, displays of contempt and impatience on the part of government officials towards journalists and their work" in Italy.

["Press Freedom Index 2010"](_blank)

, Reporters Without Borders, 2010 Julliard added that Italy will probably be ranked last in the European Union in the upcoming edition of the RWB

press freedom index

The World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) is an annual ranking of Country, countries compiled and published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) since 2002 based upon the non-governmental organization's own assessment of the countries' Freedom of the ...

. Italy was in fact ranked last in the EU in RWB's "Press Freedom Index 2010".

Internet censorship

Italy is listed as engaged in selective Internet filtering in the social area and no evidence of filtering was found in the political, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by the

OpenNet Initiative

The OpenNet Initiative (ONI) was a joint project whose goal was to monitor and report on internet filtering and surveillance practices by nations. Started in 2002, the project employed a number of technical means, as well as an international netwo ...

in December 2010. Access to almost 7,000 websites is filtered in the country.

Filtering in Italy is applied against child pornography,

gambling, and some P2P web sites. Starting in February 2009,

The Pirate Bay

The Pirate Bay, commonly abbreviated as TPB, is a free searchable online index of Film, movies, music, video games, Pornographic film, pornography and software. Founded in 2003 by Swedish think tank , The Pirate Bay facilitates the connection ...

website and

IP address

An Internet Protocol address (IP address) is a numerical label such as that is assigned to a device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication. IP addresses serve two main functions: network interface i ...

are unreachable from Italy, blocked directly by

Internet service provider

An Internet service provider (ISP) is an organization that provides a myriad of services related to accessing, using, managing, or participating in the Internet. ISPs can be organized in various forms, such as commercial, community-owned, no ...

s. A controversial verdict issued by the Court of Bergamo, and later confirmed by the Supreme Court, allowed the blocking, stating that it was useful to prevent copyright infringement. Pervasive filtering is applied to gambling websites that do not have a local license to operate in Italy.

Several legal tools are in development to monitor and censor Internet access and content. Examples include the Romani law, a special law proposed by parliament after Facebook cases of a group against Prime Minister Berlusconi.

An

anti-terrorism law, amended in 2005, by then-

Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

Giuseppe Pisanu

Giuseppe "Beppe" Pisanu (born 2 January 1937 in Ittiri, province of Sassari) is an Italian politician, longtime member of the Chamber of Deputies for the Christian Democracy (1972–1992) and then for Forza Italia (1994–2006).

Biography

P ...

, after the terrorist attacks in

Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

and

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

,

used to restrict the opening of new

Wi-Fi hotspots.

Interested entities were required to first apply for permission to open the hotspot at the local

police headquarters

The police are a constituted body of people empowered by a state with the aim of enforcing the law and protecting the public order as well as the public itself. This commonly includes ensuring the safety, health, and possessions of citizens ...

.

The law required potential hotspot and

Internet café

An Internet café, also known as a cybercafé, is a Coffeehouse, café (or a convenience store or a fully dedicated Internet access business) that provides the use of computers with high bandwidth Internet access on the payment of a fee. Usage ...

users to present an

identity document

An identity document (abbreviated as ID) is a documentation, document proving a person's Identity (social science), identity.

If the identity document is a plastic card it is called an ''identity card'' (abbreviated as ''IC'' or ''ID card''). ...

.

This has inhibited the opening of hotspots across Italy,

with the number of hotspots five times lower than France and led to an absence of

municipal wireless network

A municipal wireless network is a citywide wireless network. This usually works by providing municipal broadband via Wi-Fi to large parts or all of a municipal area by deploying a wireless mesh network. The typical deployment design uses hundreds ...

s.

In 2009, only 32% of Italian Internet users had Wi-Fi access.

After some unsuccessful

proposals

Proposal(s) or The Proposal may refer to:

* Proposal (business)

* Research proposal

* Marriage proposal

* Proposition, a proposal in logic and philosophy

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Proposal'' (album), an album by Ransom & Statik Se ...

to facilitate the opening of and access to Wi-Fi hotspots,

the original 2005 law was repealed in 2011. In 2013, a new text was approved clarifying that operators are not required to identify users, nor to log the traffic.

Access to the

white nationalist

White nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that white people are a Race (human categorization), raceHeidi Beirich and Kevin Hicks. "Chapter 7: White nationalism in America". In Perry, Barbara ...

forum

Stormfront has also been blocked from Italy since 2012.

List of censored films

From the Unification of Italy to the fascist regime (1861–1922)

* ''

L'Inferno'' (1911) by

Francesco Bertolini,

Adolfo Padovan and

Giuseppe De Liguoro, managed to obtain a visa after cutting the final scene.

* ''

Floretta and Patapon'' by

Mario Caserini (1913), managed to obtain a visa after cutting two scenes.

From the fascist regime to the Italian Republic (1922–1946)

During

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

the following films were prohibited or cut:

* ''

Westfront 1918'' (1930) by

Georg Wilhelm Pabst, released only in 1962.

* ''

All Quiet on the Western'' (1930) by

Lewis Milestone

Lewis Milestone (born Leib Milstein (Russian: Лейб Мильштейн); September 30, 1895 – September 25, 1980) was an American film director. Milestone directed '' Two Arabian Knights'' (1927) and '' All Quiet on the Western Front'' (1 ...

, released only in 1956.

* ''

Street Scene'' (1931) by

King Vidor

King Wallis Vidor ( ; February 8, 1894 – November 1, 1982) was an American film director, film producer, and screenwriter whose 67-year film-making career successfully spanned the silent and sound eras. His works are distinguished by a vivid, ...

.

* ''

Mountains on Fire'' (1931) by

Luis Trenker

Luis Trenker (born Alois Franz Trenker, 4 October 1892 – 12 April 1990) was a South Tyrolean film producer, director, writer, actor, architect, alpinist, and bobsledder.

Biography Early life

Alois Franz Trenker was born on 4 October 1892 in ...

, released only in 1951.

* ''

The Public Enemy'' (1931) by

William A. Wellman.

* ''

Little Caesar'' (1931) by

Mervyn LeRoy

Mervyn LeRoy (; October 15, 1900 – September 13, 1987) was an American film director and producer. During the 1930s, he was one of the two great practitioners of economical and effective film directing at Warner Bros., Warner Brothers studios, ...

.

* ''

Freaks'' (1932) by

Tod Browning

Tod Browning (born Charles Albert Browning Jr.; July 12, 1880 – October 6, 1962) was an American film director, film actor, screenwriter, vaudeville performer, and carnival sideshow and circus entertainer. He directed a number of films of var ...

.

* ''

A Farewell to Arms

''A Farewell to Arms'' is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant () in the a ...

'' (1932) by

Frank Borzage

Frank Borzage ( né Borzaga; April 23, 1894 – June 19, 1962) was an American film director and actor. He was the first person to win the Academy Awards, Academy Award for Academy Award for Best Director, Best Director for his film ''7th Heaven ...

, released only in 1956.

* ''

Rasputin and the Empress'' (1932) by

Richard Boleslawski

Richard Boleslawski (born Bolesław Ryszard Srzednicki; February 4, 1889 – January 17, 1937) was a Polish theatre and film director, actor and teacher of acting.

Biography

Richard Boleslawski was born Bolesław Ryszard Srzednicki on February ...

, released only in 1960.

* ''

Scarface'' (1932) by

Howard Hawks

Howard Winchester Hawks (May 30, 1896December 26, 1977) was an American film director, Film producer, producer, and screenwriter of the Classical Hollywood cinema, classic Hollywood era. Critic Leonard Maltin called him "the greatest American ...

, released only in 1947 with a ban on children under 16.

* ''

Ragazzo'' (1933) by

Ivo Perilli.

* ''

The Lives of a Bengal Lance'' (1935) by

Henry Hathaway

Henry Hathaway (March 13, 1898 – February 11, 1985) was an American film director and producer. He is best known as a director of Western (genre), Westerns, especially starring Randolph Scott and John Wayne. He directed Gary Cooper in seven f ...

.

* ''

The Three-Cornered Hat'' (1935) by

Mario Camerini

Mario Camerini (6 February 1895 – 4 February 1981) was an Italian film director and screenwriter.

Camerini began his career in the film industry in 1920, working for his cousin the director Augusto Genina. Camerini went on to direct his own fi ...

.

* ''

The 39 Steps'' (1935) by

Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English film director. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featu ...

.

* ''

The Green Pastures'' (1936) by

William Keighley

William Jackson Keighley (August 4, 1889 – June 24, 1984) was an American stage actor and Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood film director.

Career

After graduating from the Ludlum School of Dramatic Art, Keighley began acting at the age of ...

.

* ''

The Charge of the Light Brigade'' (1936) by

Michael Curtiz

Michael Curtiz (; born Manó Kaminer; from 1905 Mihály Kertész; ; December 24, 1886 April 10, 1962) was a Hungarian-American film director, recognized as one of the most prolific directors in history. He directed classic films from the silen ...

.

* ''

The Lower Depths

''The Lower Depths'' (, literally: ''At the bottom'') is a play by Russian dramatist Maxim Gorky written in 1902 and produced by the Moscow Arts Theatre on December 18, 1902, under the direction of Konstantin Stanislavski. It became his first ma ...

'' (1936), ''

La Grande Illusion

''La Grande Illusion'' (French for "The Grand Illusion") is a 1937 French war drama film directed by Jean Renoir, who co-wrote the screenplay with Charles Spaak. The story concerns class relationships among a small group of French officers who ...

'' (1937) and ''

La Bête Humaine'' (1938) by

Jean Renoir

Jean Renoir (; 15 September 1894 – 12 February 1979) was a French film director, screenwriter, actor, producer and author. His '' La Grande Illusion'' (1937) and '' The Rules of the Game'' (1939) are often cited by critics as among the greate ...

.

* ''

Dead End'' (1937) by

William Wyler

William Wyler (; born Willi Wyler (); July 1, 1902 – July 27, 1981) was a German-born American film director and producer. Known for his work in numerous genres over five decades, he received numerous awards and accolades, including three Aca ...

, released only in 1948.

* ''

The Life of Emile Zola'' (1937) by

William Dieterle

William Dieterle (July 15, 1893 – December 9, 1972) was a German-born actor and film director who emigrated to the United States in 1930 to leave a worsening political situation. He worked in Cinema of the United States, Hollywood primarily a ...

, released in 1946.

* ''

Port of Shadows'' (1938) by

Marcel Carné

Marcel Albert Carné (; 18 August 1906 – 31 October 1996) was a French film director. A key figure in the poetic realism movement, Carné's best known films include ''Port of Shadows'' (1938), ''Le Jour Se Lève'' (1939), ''Les Visiteurs du Soi ...

.

* ''

The Adventures of Marco Polo'' (1938) by

Archie Mayo

Archibald L. Mayo (January 29, 1891 – December 4, 1968) was a film director, screenwriter and actor.

Early years

The son of a tailor, Mayo was born in New York City. After attending the city's public schools, he studied at Columbia Unive ...

, was released in 1939 under the name A Scotsman in the Court of the Great Khan.

* ''

Orage'' (1938) by

Marc Allégret

Marc Allégret (22 December 1900 – 3 November 1973) was a French screenwriter, photographer and film director.

Biography

Born in Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland, he was the elder brother of Yves Allégret. Marc was educated to be a lawyer in ...

.

* ''

The Baker's Wife'' (1938) by

Marcel Pagnol

Marcel Paul Pagnol (, also ; ; 28 February 1895 – 18 April 1974) was a French novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Regarded as an auteur, in 1946, he became the first filmmaker elected to the . Pagnol is generally regarded as one of France's ...

.

* ''

The End of the Day

''The End of the Day'' () is a 1939 French drama film directed by Julien Duvivier and starring Victor Francen, Michel Simon, Madeleine Ozeray and Louis Jouvet. It was shot at the Epinay Studios in Paris and on location around the city as wel ...

'' (1938) by

Julien Duvivier

Julien Duvivier (; 8 October 1896 – 29 October 1967) was a French film director and screenwriter. He was prominent in French cinema in the years 1930–1960. Amongst his most original films, chiefly notable are ''La Bandera (film), La Bandera'', ...

.

* ''

The Shanghai Drama'' (1938) by

Georg Wilhelm Pabst.

* ''

Idiot's Delight'' (1939) by

Clarence Brown

Clarence Leon Brown (May 10, 1890 – August 17, 1987) was an American film director.

Early life

Born in Clinton, Massachusetts, to Larkin Harry Brown, a cotton manufacturer, and Katherine Ann Brown (née Gaw), Brown moved to Tennessee when h ...

.

* ''

The Great Dictator

''The Great Dictator'' is a 1940 American political satire black comedy film written, directed, produced by, and starring Charlie Chaplin. Having been the only Hollywood filmmaker to continue to make silent films well into the period of sound f ...

'' (1940) by

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, blocked by the Italian fascist regime until 1943 (in southern Italy) and 1945 (in northern Italy).

* ''

Ossessione'' (1943) by

Luchino Visconti

Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo (; 2 November 1906 – 17 March 1976) was an Italian filmmaker, theatre and opera director, and screenwriter. He was one of the fathers of Italian neorealism, cinematic neorealism, but later ...

, distributed in some theatres, but shortly afterwards it was banned and all copies found by the fascist authorities were destroyed. The copies distributed starting from 1945 were derived from a copy of the negative saved by Luchino Visconti.

* All communist, socialist or Russian-made films were forbidden.

Italian Republic (1946–present)

* ''

Rope

A rope is a group of yarns, Plying, plies, fibres, or strands that are plying, twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have high tensile strength and can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger ...

'' (1948) by

Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English film director. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featu ...

, blocked by censors in 1949 and released only in 1956.

* ''

Toto and Carolina'' (1955) by

Mario Monicelli

Mario Alberto Ettore Monicelli (; 16 May 1915 – 29 November 2010) was an Italian film director and screenwriter, one of the masters of the ''commedia all'italiana'' ("Italian-style comedy"). He was nominated six times for an Academy Awards, Os ...

, blocked by censors in February 1954, was distributed in 1955 only after numerous cuts.

* ''

Different from You and Me'' (1957) by

Veit Harlan

Veit Harlan (22 September 1899 – 13 April 1964) was a German film director and actor. Harlan reached the high point of his career as a director in the Nazi era; most notably his antisemitic film '' Jud Süß'' (1940) makes him controversial. W ...

, blocked by censors three times and released only in 1962 with the new definitive title of Trial Behind Closed Doors.

* ''

The Howl'' (1968) by

Tinto Brass

Giovanni "Tinto" Brass (born 26 March 1933) is an Italian film director and screenwriter. In the 1960s and 1970s, he directed many critically acclaimed avant-garde films of various genres. Today, he is mainly known for his later work in the Erot ...

was blocked by censors from 1969 until 1974.

* ''

Deep Throat'' (1972 pornographic film) by

Gerard Damiano, was blocked by censors for three years in 1972; It was released in 1975 with the title ''The Real Deep Throat''.

* ''

Last Tango in Paris

''Last Tango in Paris'' (; ) is a 1972 Erotic film, erotic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. The film stars Marlon Brando, Maria Schneider (actor), Maria Schneider and Jean-Pierre Léaud, and portrays a rec ...

'' (1972) by

Bernardo Bertolucci

Bernardo Bertolucci ( ; ; 16 March 1941 – 26 November 2018) was an Italian film director and screenwriter with a career that spanned 50 years. Considered one of the greatest directors in the history of cinema, Bertolucci's work achieved inte ...

, blocked by censorship until 1987.

* ''

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom

''Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom'' (), billed on-screen as ''Pasolini's 120 Days of Sodom'' on English-language prints and commonly referred to as simply ''Salò'' (), is a 1975 political art horror film directed and co-written by Pier Paolo P ...

'' (1976) by

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini (; 5 March 1922 – 2 November 1975) was an Italian poet, film director, writer, actor and playwright. He is considered one of the defining public intellectuals in 20th-century Italian history, influential both as an artist ...

, rejected in the first instance by the commission and forbidden to minors under 18 in the second instance, was then seized by the judiciary. The film was only broadcast on TV for the first time in 2005 (on

Pay television

Pay television, also known as subscription television, premium television or, when referring to an individual service, a premium channel, refers to Subscription business model, subscription-based television services, usually provided by multichan ...

).

* ''

Sesso nero'' (1978) by

Joe D'Amato

Aristide Massaccesi (15 December 1936 – 23 January 1999), known professionally as Joe D'Amato, was an Italian film director, producer, cinematographer, and screenwriter who worked in many genres (western (genre), westerns, ''Commedia sexy all' ...

, blocked by censors from 1978 until 1980.

* ''

Cannibal Holocaust

''Cannibal Holocaust'' is a 1980 Italian cannibal film directed by Ruggero Deodato and written by Gianfranco Clerici. It stars Robert Kerman as Harold Monroe, an anthropologist who leads a rescue team into the Amazon rainforest to locate a ...

'' (1980) by

Ruggero Deodato

Ruggero Deodato (; 7 May 1939 – 29 December 2022) was an Italian film director, screenwriter, and actor.

His career spanned a wide-range of genres including Sword-and-sandal, peplum, Comedy film, comedy, Drama (film and television), drama, P ...

, blocked by censors from 1980 to 1984 and then heavily cut, to be published in full version in the DVD edition.

* ''

Lion of the Desert

''Lion of the Desert'' (alternative titles: ''Omar Mukhtar'' and ''Omar Mukhtar: Lion of the Desert'') is a 1981 epic film, epic historical film, historical war film about the Second Italo-Senussi War, starring Anthony Quinn as Libyan tribal leade ...

'' (1980) by

Moustapha Akkad

Moustapha al Akkad (; July 1, 1930 – November 11, 2005) was a Syrian Americans, Syrian-American film producer and Film director, director, best known for producing the original series of ''Halloween (franchise), Halloween'' films and dire ...

, blocked by

Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti ( ; ; 14 January 1919 – 6 May 2013) was an Italian politician and wikt:statesman, statesman who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy in seven governments (1972–1973, 1976–1979, and 1989–1992), and was leader of th ...

in 1982, finally broadcast in 2009 by the pay television

SKY

The sky is an unobstructed view upward from the planetary surface, surface of the Earth. It includes the atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere and outer space. It may also be considered a place between the ground and outer space, thus distinct from ...

.

* ''

Totò che visse due volte'' (1998) by