Cello Technique on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

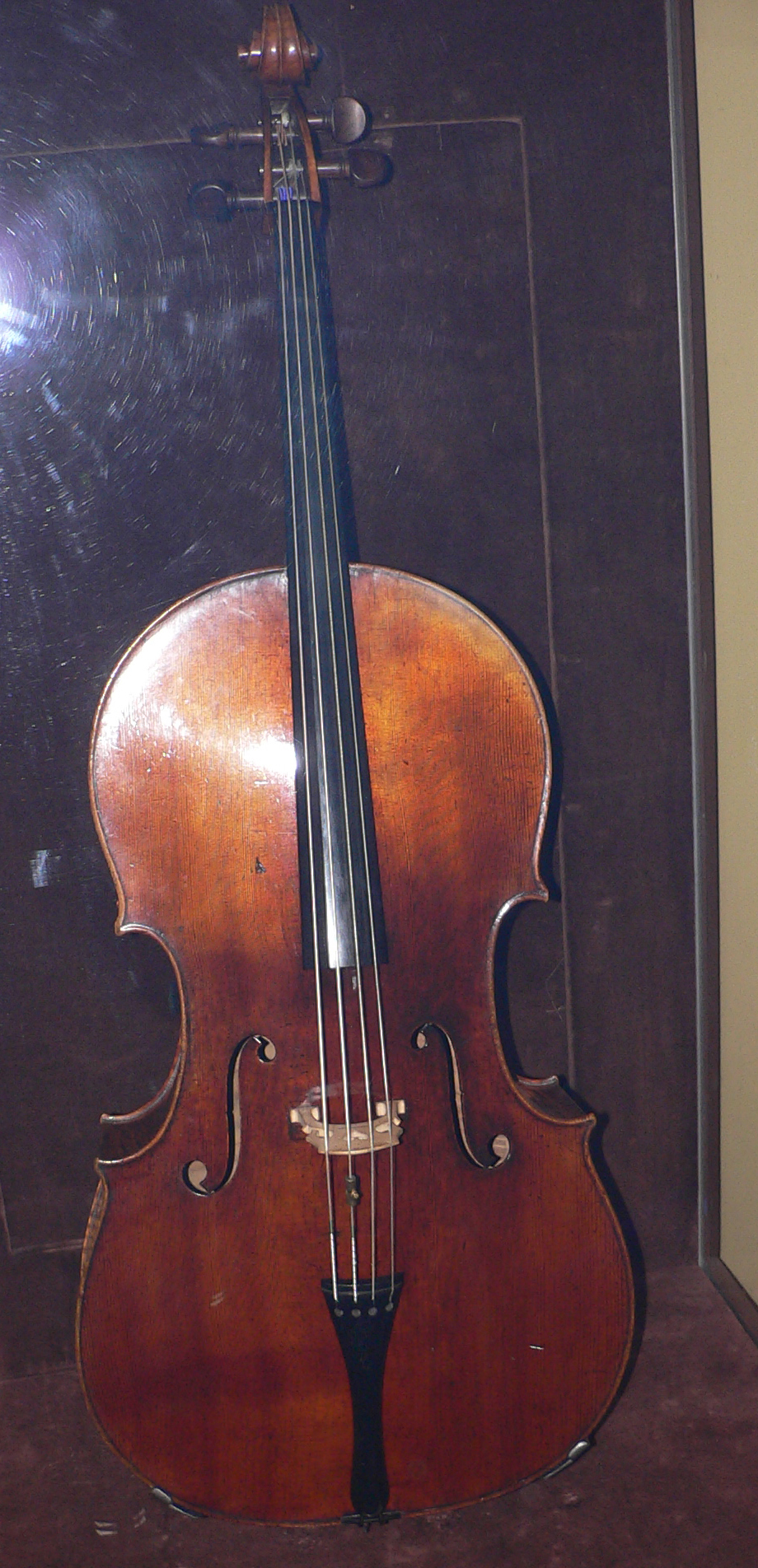

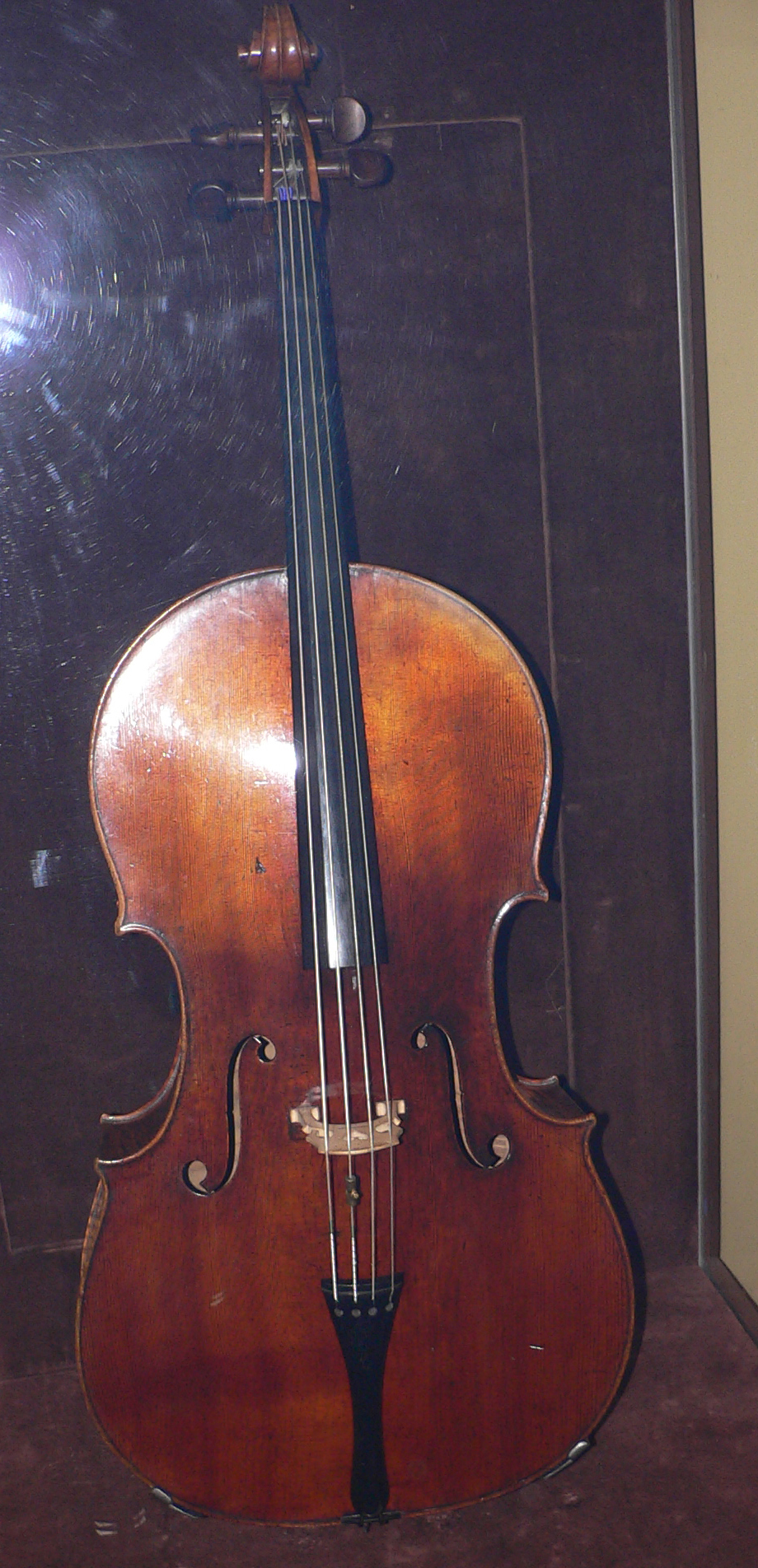

The violoncello ( , ), commonly abbreviated as cello ( ), is a middle pitched bowed (sometimes plucked and occasionally

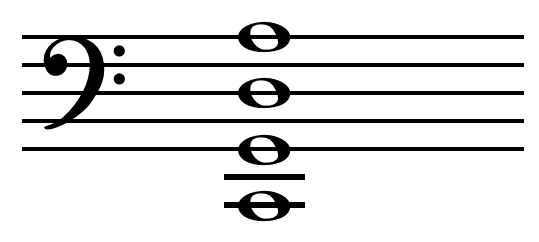

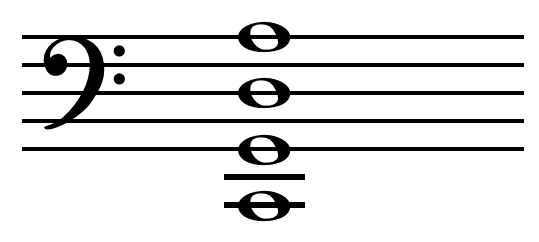

Cellos are tuned in fifths, starting with C2 (two

Cellos are tuned in fifths, starting with C2 (two

The invention of wire-wound

The invention of wire-wound

The cello is less common in

The cello is less common in

The cello is typically made from carved wood, although other materials such as

The cello is typically made from carved wood, although other materials such as

The

The

Traditionally, bows are made from

Traditionally, bows are made from

A played note of E or F has a frequency that is often very close to the natural resonating frequency of the body of the instrument, and if the problem is not addressed this can set the body into near resonance. This may cause an unpleasant sudden amplification of this pitch, and additionally a loud beating sound results from the interference produced between these nearby frequencies; this is known as the " wolf tone" because it is an unpleasant growling sound. The wood resonance appears to be split into two frequencies by the driving force of the sounding string. These two periodic resonances beat with each other. This wolf tone must be eliminated or significantly reduced for the cello to play the nearby notes with a pleasant tone. This can be accomplished by modifying the cello front plate, attaching a wolf eliminator (a metal cylinder or a rubber cylinder encased in metal), or moving the soundpost.

When a string is bowed or plucked to produce a note, the fundamental note is accompanied by higher frequency overtones. Each sound has a particular recipe of frequencies that combine to make the total sound.

A played note of E or F has a frequency that is often very close to the natural resonating frequency of the body of the instrument, and if the problem is not addressed this can set the body into near resonance. This may cause an unpleasant sudden amplification of this pitch, and additionally a loud beating sound results from the interference produced between these nearby frequencies; this is known as the " wolf tone" because it is an unpleasant growling sound. The wood resonance appears to be split into two frequencies by the driving force of the sounding string. These two periodic resonances beat with each other. This wolf tone must be eliminated or significantly reduced for the cello to play the nearby notes with a pleasant tone. This can be accomplished by modifying the cello front plate, attaching a wolf eliminator (a metal cylinder or a rubber cylinder encased in metal), or moving the soundpost.

When a string is bowed or plucked to produce a note, the fundamental note is accompanied by higher frequency overtones. Each sound has a particular recipe of frequencies that combine to make the total sound.

Playing the cello is done while seated with the instrument supported on the floor by the endpin. The right hand bows (or sometimes plucks) the strings to sound the notes. The left-hand fingertips stop the strings along their length, determining the pitch of each fingered note. Stopping the string closer to the bridge results in a higher-pitched sound because the vibrating string length has been shortened. On the contrary, a string stopped closer to the tuning pegs produces a lower sound. In the ''neck'' positions (which use just less than half of the fingerboard, nearest the top of the instrument), the thumb rests on the back of the neck, some people use their thumb as a marker of their position; in ''

Playing the cello is done while seated with the instrument supported on the floor by the endpin. The right hand bows (or sometimes plucks) the strings to sound the notes. The left-hand fingertips stop the strings along their length, determining the pitch of each fingered note. Stopping the string closer to the bridge results in a higher-pitched sound because the vibrating string length has been shortened. On the contrary, a string stopped closer to the tuning pegs produces a lower sound. In the ''neck'' positions (which use just less than half of the fingerboard, nearest the top of the instrument), the thumb rests on the back of the neck, some people use their thumb as a marker of their position; in ''

Standard-sized cellos are referred to as "full-size" or "" but are also made in smaller (fractional) sizes, including , , , , , , , and . The fractions refer to volume rather than length, so a size cello is much longer than half the length of a full size. The smaller cellos are identical to standard cellos in construction, range, and usage, but are simply scaled-down for the benefit of children and shorter adults.

Cellos in sizes larger than do exist, and cellists with unusually large hands may require such a non-standard instrument. Cellos made before tended to be considerably larger than those made and commonly played today. Around 1680, changes in string-making technology made it possible to play lower-pitched notes on shorter strings. The cellos of

Standard-sized cellos are referred to as "full-size" or "" but are also made in smaller (fractional) sizes, including , , , , , , , and . The fractions refer to volume rather than length, so a size cello is much longer than half the length of a full size. The smaller cellos are identical to standard cellos in construction, range, and usage, but are simply scaled-down for the benefit of children and shorter adults.

Cellos in sizes larger than do exist, and cellists with unusually large hands may require such a non-standard instrument. Cellos made before tended to be considerably larger than those made and commonly played today. Around 1680, changes in string-making technology made it possible to play lower-pitched notes on shorter strings. The cellos of

There are many accessories for the cello.

* Cases are used to protect the cello and bow (or multiple bows).

*

There are many accessories for the cello.

* Cases are used to protect the cello and bow (or multiple bows).

*

Specific instruments are famous (or become famous) for a variety of reasons. An instrument's notability may arise from its age, the fame of its maker, its physical appearance, its acoustic properties, and its use by notable performers. The most famous instruments are generally known for all of these things. The most highly prized instruments are now collector's items and are priced beyond the reach of most musicians. These instruments are typically owned by some kind of organization or investment group, which may loan the instrument to a notable performer. For example, the Davidov Stradivarius, which is currently in the possession of one of the most widely known living cellists, Yo-Yo Ma, is actually owned by the Vuitton Foundation.

Some notable cellos:

*the "King", by

Specific instruments are famous (or become famous) for a variety of reasons. An instrument's notability may arise from its age, the fame of its maker, its physical appearance, its acoustic properties, and its use by notable performers. The most famous instruments are generally known for all of these things. The most highly prized instruments are now collector's items and are priced beyond the reach of most musicians. These instruments are typically owned by some kind of organization or investment group, which may loan the instrument to a notable performer. For example, the Davidov Stradivarius, which is currently in the possession of one of the most widely known living cellists, Yo-Yo Ma, is actually owned by the Vuitton Foundation.

Some notable cellos:

*the "King", by

grovemusic.com

(subscription access). * * * * * * * With a preface by

"My Cello"

In ''Evocative Objects: Things We Think With'', Turkle, Sherry (editor), Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

The Violoncello Foundation

{{Authority control C instruments Articles containing video clips String section Basso continuo instruments Italian inventions

hit

Hit means to strike someone or something.

Hit or HIT may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional entities

* Hit, a fictional character from ''Dragon Ball Super''

* Homicide International Trust or HIT, a fictional organization i ...

) string instrument

In musical instrument classification, string instruments, or chordophones, are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer strums, plucks, strikes or sounds the strings in varying manners.

Musicians play some ...

of the violin family

The violin family of musical instruments was developed in Italy in the 16th century. At the time the name of this family of instruments was viole da braccio which was used to distinguish them from the viol family (viole ''da gamba''). The standa ...

. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifth

In music theory, a perfect fifth is the Interval (music), musical interval corresponding to a pair of pitch (music), pitches with a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

In classical music from Western culture, a fifth is the interval f ...

s: from low to high, C2, G2, D3 and A3. The viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

's four strings are each an octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

higher. Music for the cello is generally written in the bass clef

A clef (from French: 'key') is a musical symbol used to indicate which notes are represented by the lines and spaces on a musical staff. Placing a clef on a staff assigns a particular pitch to one of the five lines or four spaces, whi ...

; the tenor clef

A clef (from French: 'key') is a Musical notation, musical symbol used to indicate which Musical note, notes are represented by the lines and spaces on a musical staff (music), staff. Placing a clef on a staff assigns a particular pitch ...

and treble clef

A clef (from French: 'key') is a musical symbol used to indicate which notes are represented by the lines and spaces on a musical staff. Placing a clef on a staff assigns a particular pitch to one of the five lines or four spaces, whi ...

are used for higher-range passages.

Played by a ''cellist

The violoncello ( , ), commonly abbreviated as cello ( ), is a middle pitched bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), tuned i ...

'' or ''violoncellist'', it enjoys a large solo repertoire with

With or WITH may refer to:

* With, a preposition in English

* Carl Johannes With (1877‚Äď1923), Danish doctor and arachnologist

* With (character), a character in ''D. N. Angel''

* ''With'' (novel), a novel by Donald Harrington

* ''With'' (album ...

and without accompaniment, as well as numerous concerti

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ty ...

. As a solo instrument, the cello uses its whole range, from bass to soprano, and in chamber music

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of Musical instrument, instruments‚ÄĒtraditionally a group that could fit in a Great chamber, palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music ...

, such as string quartet

The term string quartet refers to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two Violin, violini ...

s and the orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, ...

's string section

The string section of an orchestra is composed of bowed instruments belonging to the violin family. It normally consists of first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses. It is the most numerous group in the standard orchestra. In ...

, it often plays the bass part, where it may be reinforced an octave lower by the double bass

The double bass (), also known as the upright bass, the acoustic bass, the bull fiddle, or simply the bass, is the largest and lowest-pitched string instrument, chordophone in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding rare additions ...

es. Figured bass

Figured bass is musical notation in which numerals and symbols appear above or below (or next to) a bass note. The numerals and symbols (often accidental (music), accidentals) indicate interval (music), intervals, chord (music), chords, and non- ...

music of the Baroque era

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s. It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo (i ...

typically assumes a cello, viola da gamba

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

or bassoon

The bassoon is a musical instrument in the woodwind family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuosity ...

as part of the basso continuo

Basso continuo parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600‚Äď1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing th ...

group alongside chordal instruments such as organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

, harpsichord

A harpsichord is a musical instrument played by means of a musical keyboard, keyboard. Depressing a key raises its back end within the instrument, which in turn raises a mechanism with a small plectrum made from quill or plastic that plucks one ...

, lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck (music), neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lu ...

, or theorbo

The theorbo is a plucked string instrument of the lute family, with an extended neck that houses the second pegbox. Like a lute, a theorbo has a curved-back sound box with a flat top, typically with one or three sound holes decorated with rose ...

. Cellos are found in many other ensembles, from modern Chinese orchestra

The term Chinese orchestra is most commonly used to refer to the modern Chinese orchestra that is found in China and various overseas Chinese communities. This modern Chinese orchestra first developed out of Jiangnan sizhu ensemble in the 1920s ...

s to cello rock

Cello rock is a subgenre of rock music characterized by the use of cellos (as well as other bowed string instruments such as the violin and viola) as primary instruments, alongside or in place of more traditional rock instruments such as electri ...

bands.

Etymology

The name ''cello'' is derived from the ending of theItalian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

''violoncello'', which means "little violone

The term violone (; literally 'large viol', being the augmentative suffix) can refer to several distinct large, bowed musical instruments which belong to either the viol or violin family. The violone is sometimes a fretted instrument, and may ...

". Violone

The term violone (; literally 'large viol', being the augmentative suffix) can refer to several distinct large, bowed musical instruments which belong to either the viol or violin family. The violone is sometimes a fretted instrument, and may ...

("big viola") was a large-sized member of viol

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

(viola da gamba) family or the violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

(viola da braccio

Viola da braccio (from Italian "arm viola", plural ''viole da braccio'') is a term variously applied during the baroque period to instruments of the violin family, in distinction to the viola da gamba ("leg viola") and the viol family to whic ...

) family. The term "violone" today usually refers to the lowest-pitched instrument of the viols, a family of stringed instruments that went out of fashion around the end of the 17th century in most countries except England and, especially, France, where they survived another half-century before the louder violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

family came into greater favour in that country as well.

In modern symphony orchestras

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, a ...

, it is the second largest stringed instrument (the double bass

The double bass (), also known as the upright bass, the acoustic bass, the bull fiddle, or simply the bass, is the largest and lowest-pitched string instrument, chordophone in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding rare additions ...

is the largest). Thus, the name "violoncello" contained both the augmentative

An augmentative (abbreviated ) is a morphological form of a word which expresses greater intensity, often in size but also in other attributes. It is the opposite of a diminutive.

Overaugmenting something often makes it grotesque and so in so ...

"''-one''" ("big") and the diminutive

A diminutive is a word obtained by modifying a root word to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment, and sometimes to belittle s ...

"''-cello''" ("little"). By the turn of the 20th century, it had become common to shorten the name to 'cello, with the apostrophe indicating the missing stem. It is now customary to use "cello" without apostrophe as the full designation. ''Viol'' is derived from the root ''viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

'', which was derived from Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

, meaning stringed instrument.

General description

Tuning

Cellos are tuned in fifths, starting with C2 (two

Cellos are tuned in fifths, starting with C2 (two octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

s below middle C

C or Do is the first note of the C major scale, the third note of the A minor scale (the relative minor of C major), and the fourth note (G, A, B, C) of the Guidonian hand, commonly pitched around 261.63 Hz. The actual frequency has d ...

), followed by G2, D3, and then A3. It is tuned in the exact same intervals and strings as the viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

, but an octave lower. Similar to the double bass

The double bass (), also known as the upright bass, the acoustic bass, the bull fiddle, or simply the bass, is the largest and lowest-pitched string instrument, chordophone in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding rare additions ...

, the cello has an endpin

An endpin, more commonly spelled end pin and also called tailpin,https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/endpin is the component of a cello or double bass that makes contact with the floor to support the instrument's weight. It is made of meta ...

that rests on the floor to support the instrument's weight. The cello is most closely associated with European classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be #Relationship to other music traditions, distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical mu ...

. The instrument is a part of the standard orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, ...

, as part of the string section

The string section of an orchestra is composed of bowed instruments belonging to the violin family. It normally consists of first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses. It is the most numerous group in the standard orchestra. In ...

, and is the bass voice of the string quartet

The term string quartet refers to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two Violin, violini ...

(although many composers give it a melodic role as well), as well as being part of many other chamber groups.

Works

Among the most well-known Baroque works for the cello areJohann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: Help:IPA/Standard German, ąjoňźhan zeňąbastiŐĮan baŌá ( ‚Äď 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety ...

's six unaccompanied Suites. Other significant works include Sonatas and Concertos by Antonio Vivaldi

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 ‚Äď 28 July 1741) was an Italian composer, virtuoso violinist, impresario of Baroque music and Roman Catholic priest. Regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, Vivaldi's influence during his lif ...

, and solo sonatas by Francesco Geminiani

Francesco Xaverio Geminiani (baptised 5 December 1687 ‚Äď 17 September 1762) was an Italian violinist, composer, and music theorist. BBC Radio 3 once described him as "now largely forgotten, but in his time considered almost a musical god, deem ...

and Giovanni Bononcini

Giovanni Bononcini (or Buononcini) (18 July 1670 ‚Äď 9 July 1747) (sometimes cited also as Giovanni Battista Bononcini) was an Italian Baroque composer, cellist, singer and teacher, one of a family of string players and composers. He was a rival ...

. Domenico Gabrielli

Domenico Gabrielli (15 April 1651 or 19 October 1659 ‚Äď 10 July 1690) was an Italian Baroque composer and one of the earliest known virtuoso cello players, as well as a pioneer of cello music writing. Born in Bologna, he worked in the orchestra of ...

was one of the first composers to treat the cello as a solo instrument. As a basso continuo

Basso continuo parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600‚Äď1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing th ...

instrument the cello may have been used in works by Francesca Caccini

Francesca Caccini (; 18 September 1587 ‚Äď most likely between 1641 and 1645) was an Italian composer, singer, lutenist, poet, and music teacher of the early Baroque era. She was also known by the nickname La Cecchina , given to her by the Floren ...

(1587‚Äď1641), Barbara Strozzi

Barbara Strozzi (also called Barbara Valle; baptised 6 August 1619 ‚Äď 11 November 1677) was an Italian composer and singer of the Baroque Period. During her lifetime, Strozzi published eight volumes of her own music, and had more secular ...

(1619‚Äď1677) with pieces such as ''Il primo libro di madrigali, per 2‚Äď5 voci e basso continuo, op. 1'' and Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Empress Elisabeth (disambiguation), lists various empresses named ''Elisabeth'' or ''Elizabeth''

* Princess Elizabeth ( ...

(1665‚Äď1729), who wrote six sonatas for violin and basso continuo. Francesco Supriani's ''Principij da imparare a suonare il violoncello e con 12 Toccate a solo'' (before 1753), an early manual for learning the cello, dates from this era. As the title of the work suggests, it contains 12 toccatas for solo cello, which along with Johann Sebastian Bach's Cello Suites, are some of the first works of that type.

From the Classical era

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

, the two concertos by Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

in C major

C major is a major scale based on C, consisting of the pitches C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. C major is one of the most common keys used in music. Its key signature has no flats or sharps. Its relative minor is A minor and its parallel min ...

and D major

D major is a major scale based on D (musical note), D, consisting of the pitches D, E (musical note), E, F‚ôĮ (musical note), F, G (musical note), G, A (musical note), A, B (musical note), B, and C‚ôĮ (musical note), C. Its key signature has two S ...

stand out, as do the five sonatas for cello and pianoforte of Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

, which span the important three periods of his compositional evolution. Other outstanding examples include the three Concerti by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (8 March 1714 ‚Äď 14 December 1788), also formerly spelled Karl Philipp Emmanuel Bach, and commonly abbreviated C. P. E. Bach, was a German composer and musician of the Baroque and Classical period. He was the fifth ch ...

, Capricci by dall'Abaco, and Sonatas by Flackton, Boismortier, and Luigi Boccherini

Ridolfo Luigi Boccherini (, also , ; 19 February 1743 ‚Äď 28 May 1805) was an Italian composer and cellist of the Classical era whose music retained a courtly and '' galante'' style even while he matured somewhat apart from the major classi ...

. A ''Divertimento for Piano, Clarinet, Viola and Cello'' is among the surviving works by Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenb√ľttel

Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenb√ľttel (24 October 173910 April 1807), was a German princess and composer. She became the duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach by marriage, and was also regent of the states of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach from 1758 t ...

(1739‚Äď1807). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 ‚Äď 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

supposedly wrote a Cello Concerto in F major, K. 206a in 1775, but this has since been lost. His Sinfonia Concertante in A major, K. 320e includes a solo part for cello, along with the violin and viola, although this work is incomplete and only exists in fragments, therefore it is given an Anhang number (Anh. 104).

Well-known works of the Romantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

include the Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

Concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ...

, the Anton√≠n DvoŇô√°k

Anton√≠n Leopold DvoŇô√°k ( ; ; 8September 18411May 1904) was a Czech composer. He frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia, following the Romantic-era nationalist example of his predec ...

Concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ...

, the first Camille Saint-Sa√ęns

Charles-Camille Saint-Sa√ęns (, , 9October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano ...

Concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ...

, as well as the two sonatas and the Double Concerto by Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; ; 7 May 1833 ‚Äď 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period (music), Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, oft ...

. A review of compositions for cello in the Romantic era must include the German composer Fanny Mendelssohn

Fanny Mendelssohn (14 November 1805 ‚Äď 14 May 1847) was a German composer and pianist of the early Romantic era who was known as Fanny Hensel after her marriage. Her compositions include a string quartet, a piano trio, a piano quartet, an or ...

(1805‚Äď1847), who wrote Fantasia in G Minor for cello and piano and a Capriccio in A-flat for cello.

Compositions from the late 19th and early 20th century include three cello sonatas (including the Cello Sonata in C Minor written in 1880) by Dame Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended ...

(1858‚Äď1944), Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 ‚Äď 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

's Cello Concerto in E minor, Claude Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 ‚Äď 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

's Sonata for Cello and Piano

A cello sonata is piece written sonata form, often with the instrumentation of a cello taking solo role with piano accompaniment. Some of the earliest cello sonatas were composed in the 18th century by Francesco Geminiani and Antonio Vivaldi, and ...

, and unaccompanied cello sonatas by Zolt√°n Kod√°ly

Zolt√°n Kod√°ly (, ; , ; 16 December 1882 ‚Äď 6 March 1967) was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, music pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is well known internationally as the creator of the Kod√°ly method of music education.

...

and Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith ( ; ; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German and American composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advo ...

. Pieces including cello were written by American Music Center

New Music USA is a new music organization formed by the merging of the American Music Center with Meet The Composer on November 8, 2011. The new organization retains the granting programs of the two former organizations as well as two media progr ...

founder Marion Bauer

Marion Eug√©nie Bauer (15 August 1882 ‚Äď 9 August 1955) was an American composer, teacher, writer, and music critic. She played an active role in shaping American musical identity in the early half of the twentieth century.

As a composer, ...

(1882‚Äď1955) (two trio sonatas for flute, cello, and piano) and Ruth Crawford Seeger

Ruth Crawford Seeger (born Ruth Porter Crawford; July 3, 1901 ‚Äď November 18, 1953) was an American composer and musicologist. Her music heralded the emerging modernist aesthetic, and she became a central member of a group of American composers ...

(1901‚Äď1953) (Diaphonic suite No. 2 for bassoon and cello).

The cello's versatility made it popular with many composers in this era, such as Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''. , group=n ( ‚Äď 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who l ...

, Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

, Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 ‚Äď 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

, György Ligeti

Gy√∂rgy S√°ndor Ligeti (; ; 28 May 1923 ‚Äď 12 June 2006) was a Hungarian-Austrian composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important avant-garde music, avant-garde composers in the latter half of the ...

, Witold Lutoslawski and Henri Dutilleux

Henri Paul Julien Dutilleux (; 22 January 1916 ‚Äď 22 May 2013) was a French composer of late 20th-century classical music. Among the leading French composers of his time, his work was rooted in the Impressionistic style of Debussy and R ...

. Polish composer GraŇľyna Bacewicz

GraŇľyna Bacewicz Biernacka (; 5 February 1909 ‚Äď 17 January 1969) was a Polish composer and violinist of Lithuanian origin. She is the second Polish female composer to have achieved national and international recognition, the first being Ma ...

(1909‚Äď1969) was writing for cello in the mid 20th century with Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra (1951), Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra (1963) and in 1964 composed her Quartet for four cellos.

Today it is sometimes featured in pop

Pop or POP may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Pop music, a musical genre

Artists

* POP, a Japanese idol group now known as Gang Parade

* Pop! (British group), a UK pop group

* Pop! featuring Angie Hart, an Australian band

Album ...

and rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

recordings, examples of which are noted later in this article. The cello has also appeared in major hip-hop

Hip-hop or hip hop (originally disco rap) is a popular music genre that emerged in the early 1970s from the African-American community of New York City. The style is characterized by its synthesis of a wide range of musical techniques. Hi ...

and R & B

Rhythm and blues, frequently abbreviated as R&B or R'n'B, is a genre of popular music that originated within African American communities in the 1940s. The term was originally used by record companies to describe recordings marketed predomina ...

performances, such as singers Rihanna

Robyn Rihanna Fenty ( ; born February 20, 1988) is a Barbadian singer, businesswoman, and actress. One of the List of music artists by net worth, wealthiest musicians in the world, List of awards and nominations received by Rihanna, her vario ...

and Ne-Yo

Shaffer Chimere Smith (born October 18, 1979), known professionally as Ne-Yo ( ), is an American singer and songwriter. Regarded as a leading figure of Contemporary R&B#2000s, 2000s R&B music, he is the recipient of numerous accolades, includi ...

's 2007 performance at the American Music Awards

The American Music Awards (AMAs) is an annual American music awards show produced by Dick Clark Productions since 1974. Nominees are selected on commercial performance such as sales and airplay. Winners are determined by a poll of the public and ...

. The instrument has also been modified for Indian classical music

Indian classical music is the art music, classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It is generally described using terms like ''Shastriya Sangeet'' and ''Marg Sangeet''. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as ...

by Nancy Lesh and Saskia Rao-de Haas Saskia Rao-de Haas (born 1971) is a virtuoso cellist and composer from the Netherlands based in New Delhi, India. She is married to the sitarist Shubhendra Rao.

Early life

Saskia was born in Abcoude, the Netherlands in a family of music lovers. ...

. /sup>

History

Theviolin family

The violin family of musical instruments was developed in Italy in the 16th century. At the time the name of this family of instruments was viole da braccio which was used to distinguish them from the viol family (viole ''da gamba''). The standa ...

, including cello-sized instruments, emerged as a family of instruments distinct from the viola da gamba

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

family. The earliest depictions of the violin family, from Italy , show three sizes of instruments, roughly corresponding to what we now call violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

s, viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

s, and cellos. Contrary to a popular misconception, the cello did not evolve from the viola da gamba, but existed alongside it for about two and a half centuries. The violin family is also known as the viola da braccio (meaning viola for the arm) family, a reference to the primary way the members of the family are held. This is to distinguish it from the viola da gamba (meaning viola for the leg) family, in which all the members are all held with the legs. The likely predecessors of the violin family include the lira da braccio

The lira da braccio (or ''lira de braccio'' or ''lyra de bracio''Michael Praetorius. Syntagma Musicum Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia Wolfenb√ľttel 1620) was a European Bow (music), bowed string instrument of the Renaissance music, Renaiss ...

and the rebec

The rebec (sometimes rebecha, rebeckha, and other spellings, pronounced or ) is a bowed stringed instrument of the Medieval era and the early Renaissance. In its most common form, it has a narrow boat-shaped body and one to five strings.

Origins ...

. The earliest surviving cellos are made by Andrea Amati

Andrea Amati ('' ca.'' 1505 - 1577, Cremona) was a luthier, from Cremona, Italy.

Amati is credited with making the first instruments of the violin family that are in the form we use today.

Several of his instruments survive to the present day ...

, the first known member of the celebrated Amati

Amati (, ) is the last name of a family of Italian violin makers who lived at Cremona from about 1538 to 1740. Their importance is considered equal to those of the Bergonzi, Guarneri, and Stradivari families. Today, violins created by Nico ...

family of luthier

A luthier ( ; ) is a craftsperson who builds or repairs string instruments.

Etymology

The word ' is originally French and comes from ''luth'', the French word for "lute". The term was originally used for makers of lutes, but it came to be ...

s.

The direct ancestor to the violoncello was the bass violin

Bass violin is the modern term for various 16th- and 17th-century bass instruments of the violin (i.e. '' viola da braccio'') family. They were the direct ancestor of the modern cello. Bass violins were usually somewhat larger than the modern ce ...

. 'unt. library''/sup> Monteverdi referred to the instrument as "basso de viola da braccio" in ''Orfeo'' (1607). Although the first bass violin

Bass violin is the modern term for various 16th- and 17th-century bass instruments of the violin (i.e. '' viola da braccio'') family. They were the direct ancestor of the modern cello. Bass violins were usually somewhat larger than the modern ce ...

, possibly invented as early as 1538, was most likely inspired by the viol, it was created to be used in consort with the violin. The bass violin was actually often referred to as a "''violone''", or "large viola", as were the viols of the same period. Instruments that share features with both the bass violin and the ''viola da gamba'' appear in Italian art of the early 16th century.

strings

String or strings may refer to:

*String (structure), a long flexible structure made from threads twisted together, which is used to tie, bind, or hang other objects

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Strings'' (1991 film), a Canadian anim ...

(fine wire around a thin gut core), in Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, allowed for a finer bass sound than was possible with purely gut strings on such a short body. Bolognese makers exploited this new technology to create the cello, a somewhat smaller instrument suitable for solo repertoire due to both the timbre of the instrument and the fact that the smaller size made it easier to play virtuosic

A virtuoso (from Italian ''virtuoso'', or ; Late Latin ''virtuosus''; Latin ''virtus''; 'virtue', 'excellence' or 'skill') is an individual who possesses outstanding talent and technical ability in a particular art or field such as fine arts, m ...

passages. This instrument had disadvantages as well, however. The cello's light sound was not as suitable for church and ensemble playing, so it had to be doubled by organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

, theorbo

The theorbo is a plucked string instrument of the lute family, with an extended neck that houses the second pegbox. Like a lute, a theorbo has a curved-back sound box with a flat top, typically with one or three sound holes decorated with rose ...

, or violone

The term violone (; literally 'large viol', being the augmentative suffix) can refer to several distinct large, bowed musical instruments which belong to either the viol or violin family. The violone is sometimes a fretted instrument, and may ...

.

Around 1700, Italian players popularized the cello in northern Europe, although the bass violin (basse de violon) continued to be used for another two decades in France. Many existing bass violins were literally cut down in size to convert them into cellos according to the smaller pattern developed by Stradivarius

A Stradivarius is one of the string instruments, such as violins, violas, cellos, and guitars, crafted by members of the Stradivari family, particularly Antonio Stradivari (Latin: Antonius Stradivarius), in Cremona, Italy, during the late 17th ...

, who also made a number of old pattern large cellos (the 'Servais').

The sizes, names, and tunings of the cello varied widely by geography and time. The size was not standardized until .

Despite similarities to the viola da gamba

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

, the cello is actually part of the viola da braccio

Viola da braccio (from Italian "arm viola", plural ''viole da braccio'') is a term variously applied during the baroque period to instruments of the violin family, in distinction to the viola da gamba ("leg viola") and the viol family to whic ...

family, meaning "viol of the arm", which includes, among others, the violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

and viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

. Though paintings like Bruegel's "The Rustic Wedding", and Jambe de Fer

Philibert Jambe de Fer (fl. 1548‚Äď1564) was a French Renaissance composer of religious music.

This composer is only known from his publications. The first known publication is a chanson for 4 voices (a motet), which dates from 1548. It appeared i ...

in his ''Epitome Musical'' suggest that the bass violin had alternate playing positions, these were short-lived and the more practical and ergonomic ''a gamba'' position eventually replaced them entirely.

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

-era cellos differed from the modern instrument in several ways. The neck has a different form and angle, which matches the baroque bass-bar and stringing. The fingerboard is usually shorter than that of the modern cello, as the highest notes are not often called for in baroque music. Modern cellos have an endpin at the bottom to support the instrument (and transmit some of the sound through the floor), while Baroque cellos are held only by the calves of the player. Modern bows curve in and are held at the frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely semiaquatic group of short-bodied, tailless amphibian vertebrates composing the order (biology), order Anura (coming from the Ancient Greek , literally 'without tail'). Frog species with rough ski ...

; Baroque bows curve out and are held closer to the bow's point of balance. Modern strings are normally flatwound with a metal (or synthetic) core; Baroque strings are made of gut, with the G and C strings wire-wound. Modern cellos often have fine tuners connecting the strings to the tailpiece, which makes it much easier to tune the instrument, but such pins are rendered ineffective by the flexibility of the gut strings used on Baroque cellos. Overall, the modern instrument has much higher string tension than the Baroque cello, resulting in a louder, more projecting tone, with fewer overtones. In addition, the instrument was less standardized in size and number of strings; a smaller, five-string variant (the violoncello piccolo) was commonly used as a solo instrument and five-string instruments are occasionally specified in the Baroque repertoire. BWV 1012 (Bach's 6th Cello Suite) was written for 5-string cello. The additional high E string on the five-string cello is an octave below the same string on the Violin, so anything written for the violin can be played on the 5 string cello, sounding an octave lower than written.

Few educational works specifically devoted to the cello existed before the 18th century and those that do exist contain little value to the performer beyond simple accounts of instrumental technique. One of the earliest cello manuals is Michel Corrette

Michael Corrette (10 April 1707 – 21 January 1795) was a French composer, organist and author of musical method books.

Life

Corrette’s father, Gaspard Corrette, was an organist and composer. Little is known of his early life.

In 1726, ...

's ''Méthode, thèorique et pratique pour apprendre en peu de temps le violoncelle dans sa perfection'' (Paris, 1741).

Modern use

Orchestral

Cellos are part of the standardsymphony orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, ...

, which usually includes eight to twelve cellists. The cello section, in standard orchestral seating, is located on stage left (the audience's right) in the front, opposite the first violin section. However, some orchestras and conductors prefer switching the positioning of the viola and cello sections. The ''principal'' cellist is the section leader, determining bowings for the section in conjunction with other string principals, playing solos, and leading entrances (when the section begins to play its part). Principal players always sit closest to the audience.

The cellos are a critical part of orchestral music; all symphonic works involve the cello section, and many pieces require cello soli or solos. Much of the time, cellos provide part of the low-register harmony for the orchestra. Often, the cello section plays the melody for a brief period, before returning to the harmony role. There are also cello concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ...

s, which are orchestral pieces that feature a solo cellist accompanied by an entire orchestra.

Solo

There are numerouscello concerto A cello concerto (sometimes called a violoncello concerto) is a concerto for solo cello with orchestra or, very occasionally, smaller groups of instruments.

These pieces have been written since the Baroque era if not earlier. However, unlike instru ...

s ‚Äď where a solo cello is accompanied by an orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families. There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* String instruments, such as the violin, viola, cello, ...

‚Äď notably 25 by Vivaldi

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 ‚Äď 28 July 1741) was an Italian composer, virtuoso violinist, impresario of Baroque music and Roman Catholic priest. Regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, Vivaldi's influence during his lif ...

, 12 by Boccherini, at least three by Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

, three by C. P. E. Bach, two by Saint-Sa√ęns, two by DvoŇô√°k, and one each by Robert Schumann, Lalo, and Elgar. There were also some composers who, while not otherwise cellists, did write cello-specific repertoire, such as Nikolaus Kraft

Nikolaus Kraft (14 December 1778, Eszterh√°za, Hungary ‚Äď 18 May 1853, Cheb, Bohemia) was an Austrian cellist and composer (six cello concertos). He was the son of Anton√≠n Kraft, under whom he first studied. He then trained under Jean-Louis Dup ...

, who wrote six cello concertos. Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

's Triple Concerto for Cello, Violin and Piano and Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; ; 7 May 1833 ‚Äď 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, often set within studied ye ...

' Double Concerto for Cello and Violin are also part of the concertante repertoire, although in both cases the cello shares solo duties with at least one other instrument. Moreover, several composers wrote large-scale pieces for cello and orchestra, which are concertos in all but name. Some familiar "concertos" are Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; ; 11 June 1864 ‚Äď 8 September 1949) was a German composer and conductor best known for his Tone poems (Strauss), tone poems and List of operas by Richard Strauss, operas. Considered a leading composer of the late Roman ...

' tone poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement (music), movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. T ...

''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'', Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 ‚Äď 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

's ''Variations on a Rococo Theme

The ''Variations on a Rococo Theme'', Op. 33, for cello and orchestra was the closest Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ever came to writing a full concerto for cello and orchestra. The style was inspired by Mozart, Tchaikovsky's role model, and makes it c ...

'', Bloch

Bloch is a surname of German origin. Notable people with this surname include:

A

*Adele Bloch-Bauer (1881‚Äď1925), Austrian entrepreneur

*Albert Bloch (1882‚Äď1961), American painter

*Alexandre Bloch (1857‚Äď1919), French painter

*Alfred Bloch ( ...

's ''Schelomo

''Schelomo: Rhapsodie H√©bra√Įque for Violoncello and Orchestra'' was the final work of composer Ernest Bloch's ''Jewish Cycle''. ''Schelomo'' (the Hebrew form of "Solomon"), which was written in 1915 to 1916, premiered on May 3, 1917, played by ce ...

'' and Bruch's ''Kol Nidrei

Kol Nidre (also known as Kol Nidrei or Kol Nidrey; Aramaic: ''kńĀl niŠłŹrńď'') is an Aramaic declaration which begins Yom Kippur services in the synagogue. Strictly speaking, it is not a prayer, even though it is commonly spoken of as if it w ...

''.

In the 20th century, the cello repertoire grew immensely. This was partly due to the influence of virtuoso cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who inspired, commissioned, and premiered dozens of new works. Among these, Prokofiev's '' Symphony-Concerto'', Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 ‚Äď 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

's '' Cello Symphony'', the concertos of Shostakovich and LutosŇāawski as well as Dutilleux's '' Tout un monde lointain...'' have already become part of the standard repertoire. Other major composers who wrote concertante works for him include Messiaen

Olivier Eug√®ne Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 ‚Äď 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithology, ornithologist. One of the major composers of the 20th-century classical music, 20th century, he was also an ou ...

, Jolivet, Berio, and Penderecki

Krzysztof Eugeniusz Penderecki (; 23 November 1933 ‚Äď 29 March 2020) was a Polish composer and conductor. His best-known works include '' Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima'', Symphony No. 3, his '' St Luke Passion'', '' Polish Requiem'', '' ...

. In addition, Arnold

Arnold may refer to:

People

* Arnold (given name), a masculine given name

* Arnold (surname), a German and English surname

Places Australia

* Arnold, Victoria, a small town in the Australian state of Victoria

Canada

* Arnold, Nova Scotia

U ...

, Barber

A barber is a person whose occupation is mainly to cut, dress, groom, style and shave hair or beards. A barber's place of work is known as a barbershop or the barber's. Barbershops have been noted places of social interaction and public discourse ...

, Glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

, Hindemith

Paul Hindemith ( ; ; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German and American composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major ad ...

, Honegger, Ligeti, Myaskovsky

Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky (; ; 20 April 18818 August 1950), was a Russian and Soviet composer. He is sometimes referred to as the "Father of the Soviet Symphony". Myaskovsky was awarded the Stalin Prize five times.

Early years

Myaskovsky ...

, Penderecki, Rodrigo

Rodrigo () is a Spanish, Portuguese and Italian name derived from the Germanic name ''Roderick'' ( Gothic ''*Hro√ĺareiks'', via Latinized ''Rodericus'' or ''Rudericus''), given specifically in reference to either King Roderic (d. 712), the la ...

, Villa-Lobos Villa-Lobos is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Dado Villa-Lobos (born 1965), Belgian-born Brazilian musician

*Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887‚Äď1959), Brazilian composer, conductor, cellist, and classical guitarist

**Villa-Lobos Museu ...

and Walton Walton may refer to:

People

* Walton (given name)

* Walton (surname)

* Susana, Lady Walton (1926‚Äď2010), Argentine writer

Places

Canada

* Walton, Nova Scotia, a community

** Walton River (Nova Scotia)

*Walton, Ontario, a hamlet

United Kingd ...

wrote major concertos

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The ty ...

for other cellists, notably for Gaspar Cassadó

Gaspar Cassadó i Moreu (30 September or 5 October 1897 Р24 December 1966) was a Catalan cellist and composer of the early 20th century.

Biography

Gaspar Cassadó i Moreu was born in Barcelona to a church musician father, Joaquim Cass ...

, Aldo Parisot

Aldo Simoes Parisot (September 30, 1918 ‚Äď December 29, 2018) was a Brazilian-born American cellist and cello teacher. He was first a member of the Juilliard School faculty, and then went on to serve as a music professor at the Yale School of Mu ...

, Gregor Piatigorsky, Siegfried Palm

Siegfried Palm (25 April 1927 ‚Äď 6 June 2005) was a German cellist who is known worldwide for his interpretations of contemporary music. Many 20th-century composers like Kagel, Ligeti, Xenakis, Penderecki and Zimmermann wrote music for ...

and Julian Lloyd Webber

Julian Lloyd Webber (born 14 April 1951) is a British solo cellist, conductor and broadcaster, a former principal of Royal Birmingham Conservatoire and the founder of the In Harmony music education programme.

Early years and education

Julia ...

.

There are also many sonatas

In music a sonata (; pl. ''sonate'') literally means a piece ''played'' as opposed to a cantata (Latin and Italian ''cantare'', "to sing"), a piece ''sung''. The term evolved through the Music history, history of music, designating a variety of ...

for cello and piano

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an Action (music), action mechanism where hammers strike String (music), strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a c ...

. Those written by Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

, Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonie ...

, Chopin, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; ; 7 May 1833 ‚Äď 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, often set within studied ye ...

, Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg ( , ; 15 June 18434 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the leading Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use of N ...

, Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

, Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 ‚Äď 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

, Fauré, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Poulenc

Francis Jean Marcel Poulenc (; 7 January 189930 January 1963) was a French composer and pianist. His compositions include mélodie, songs, solo piano works, chamber music, choral pieces, operas, ballets, and orchestral concert music. Among th ...

, Carter

Carter(s), or Carter's, Tha Carter, or The Carter(s), may refer to:

Geography United States

* Carter, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Montana, a census-designated place

* Carter ...

, and Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 ‚Äď 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

are particularly well known.

Other important pieces for cello and piano include Schumann's five ''St√ľcke im Volkston'' and transcriptions like Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

's '' Arpeggione Sonata'' (originally for arpeggione and piano), César Franck

C√©sar Auguste Jean Guillaume Hubert Franck (; 10 December 1822 ‚Äď 8 November 1890) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer, pianist, organist, and music teacher born in present-day Belgium.

He was born in Liège (which at the time of h ...

's Cello Sonata

A cello sonata is piece written sonata form, often with the instrumentation of a cello taking solo role with piano accompaniment. Some of the earliest cello sonatas were composed in the 18th century by Francesco Geminiani and Antonio Vivaldi, and ...

(originally a violin sonata, transcribed by Jules Delsart

Jules Delsart (24 November 1844 ‚Äď 3 July 1900) was a French cellist and teacher. He is best known for his arrangement for cello and piano of C√©sar Franck's Violin Sonata in A major. Musicologist Lynda MacGregor described Delsart as "one of th ...

with the composer's approval), Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ( ‚Äď 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of ...

's ''Suite italienne

''Pulcinella'' is a 21-section ballet by Igor Stravinsky with arias for soprano, tenor and bass vocal soloists, and two sung trios. It is based on the 18th-century play ''Quatre Polichinelles semblables'', or ''Four similar Pulcinellas'', revol ...

'' (transcribed by the composer ‚Äď with Gregor Piatigorsky ‚Äď from his ballet ''Pulcinella'') and Bart√≥k's first rhapsody (also transcribed by the composer, originally for violin and piano).

There are pieces for cello solo, Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: Help:IPA/Standard German, ąjoňźhan zeňąbastiŐĮan baŌá ( ‚Äď 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety ...

's six Suites for Cello (which are among the best-known solo cello pieces), Kod√°ly's Sonata for Solo Cello and Britten's three Cello Suites

The six Cello Suites, BWV 1007‚Äď1012, are suites for unaccompanied cello by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685‚Äď1750). They are some of the most frequently performed solo compositions ever written for cello. Bach most likely composed them during the p ...

. Other notable examples include Hindemith

Paul Hindemith ( ; ; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German and American composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major ad ...

's and Ysa√Ņe's Sonatas for Solo Cello, Dutilleux's ''Trois Strophes sur le Nom de Sacher'', Berio's ''Les Mots Sont All√©s'', Cassad√≥'s Suite for Solo Cello, Ligeti's Solo Sonata, Carter's two ''Figment''s and Xenakis Xenakis is a Greek surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Constantin Xenakis (1931‚Äď2020), Greek artist

* Fran√ßoise Xenakis (1930‚Äď2018), French novelist

* Iannis Xenakis (1922‚Äď2001), Greek composer and architect

* Jason Xenakis ...

' '' Nomos Alpha'' and ''Kottos''.

There are also modern solo pieces written for cello, such as Julie-O by Mark Summer

The Turtle Island Quartet is a string quartet that plays hybrids of jazz, classical, and rock music. The group was formed in 1985 by David Balakrishnan, Darol Anger, and Mark Summer in San Francisco. They released their first album on Windha ...

.

Quartets and other ensembles

The cello is a member of the traditionalstring quartet

The term string quartet refers to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two Violin, violini ...

as well as string quintets, sextet

A sextet (or hexad) is a formation containing exactly six members. The former term is commonly associated with vocal ensembles (e.g. The King's Singers, Affabre Concinui) or musical instrument groups, but can be applied to any situation where six ...

or trios

Trio may refer to:

Music Groups

* Trio (music), an ensemble of three performers, or a composition for such an ensemble

** Jazz trio, pianist, double bassist, drummer

** Minuet and trio, a form in classical music

** String trio, a group of three ...

and other mixed ensembles.

There are also pieces written for two, three, four, or more cellos; this type of ensemble is also called a "cello choir" and its sound is familiar from the introduction to Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 ‚Äď 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano p ...

's William Tell Overture

The ''William Tell'' Overture is the overture to the opera '' William Tell'' (original French title ''Guillaume Tell''), composed by Gioachino Rossini. ''William Tell'' premiered in 1829 and was the last of Rossini's 39 operas, after which he w ...

as well as Zaccharia's prayer scene in Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( ; ; 9 or 10 October 1813 ‚Äď 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma, to a family of moderate means, recei ...

's Nabucco

''Nabucco'' (; short for ''Nabucodonosor'' , i.e. "Nebuchadnezzar II, Nebuchadnezzar") is an Italian-language opera in four acts composed in 1841 by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera. The libretto is based on the biblic ...

. Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 ‚Äď 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

's 1812 Overture

''The Year 1812, Solemn Overture'', Op. 49, popularly known as the ''1812 Overture'', is a concert overture in E major written in 1880 by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The piece commemorates Russia's successful defense against the ...

also starts with a cello ensemble, with four cellos playing the top lines and two violas playing the bass lines. As a self-sufficient ensemble, its most famous repertoire is Heitor Villa-Lobos

Heitor Villa-Lobos (March 5, 1887November 17, 1959) was a Brazilian composer, conductor, cellist, and classical guitarist described as "the single most significant creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music". Villa-Lobos has globally bec ...

' first of his Bachianas Brasileiras for cello ensemble (the fifth is for soprano and 8 cellos). Other examples are Offenbach's cello duets, quartet, and sextet, Pärt's Fratres

' (meaning "brothers" in Latin) is a musical work by the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt exemplifying his tintinnabuli style of composition. It is three-part music, written in 1977, ''without fixed instrumentation'' and has been described as a "me ...

for eight cellos and Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 19255 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war contemporary classical music.

Born in Montb ...

' '' Messagesquisse'' for seven cellos, or even Villa-Lobos' rarely played ''Fantasia Concertante'' (1958) for 32 cellos. The 12 cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonic () is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

Throughout the 20th century, the orchestra was led by conductors Wilhelm Furtwängler (1922†...

(or "the Twelve" as they have since taken to being called) specialize in this repertoire and have commissioned many works, including arrangements of well-known popular songs.

Popular music, jazz, world music and neoclassical

The cello is less common in

The cello is less common in popular music

Popular music is music with wide appeal that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training.Popular Music. (2015). ''Fun ...

than in classical music. Several bands feature a cello in their standard line-up, including Hoppy Jones of the Ink Spots

The Ink Spots were an American vocal pop group who gained international fame in the 1930s and 1940s. Their unique musical style predated the rhythm and blues and rock and roll musical genres, and the subgenre doo-wop. The Ink Spots were widely ...

and Joe Kwon of the Avett Brothers

The Avett Brothers are an American folk rock band from Concord, North Carolina. The band is made up of two brothers, Scott Avett (banjo, lead vocals, guitar, piano, kick-drum) and Seth Avett (guitar, lead vocals, piano, hi-hat) along with Bob Cr ...

. The more common use in pop

Pop or POP may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Pop music, a musical genre

Artists

* POP, a Japanese idol group now known as Gang Parade

* Pop! (British group), a UK pop group

* Pop! featuring Angie Hart, an Australian band

Album ...

and rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

is to bring the instrument in for a particular song. In the 1960s, artists such as the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

and Cher

Cher ( ; born Cheryl Sarkisian, May 20, 1946) is an American singer, actress and television personality. Dubbed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Goddess of Pop", she is known for her Androgyny, androgynous contralto voice, Music an ...

used the cello in popular music, in songs such as The Beatles' " Yesterday", "Eleanor Rigby

"Eleanor Rigby" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album ''Revolver''. It was also issued on a double A-side single, paired with " Yellow Submarine". Credited to the Lennon‚ÄďMcCartney songwriting partnership, the s ...

" and "Strawberry Fields Forever

"Strawberry Fields Forever" is a song by the English Rock music, rock band the Beatles, written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon‚ÄďMcCartney. It was released on 13 February 1967 as a double A-side single with "Penny Lane". It represented ...

", and Cher's "Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)

"Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)" is the second single by American singer-actress Cher from her second album, '' The Sonny Side of Chér'' (1966). It was written by her husband Sonny Bono and released in 1966. It reached No. 3 in the UK Singles ...

". "Good Vibrations