Caves Of Kesh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Caves of Kesh, also known as the Keash Caves or the Caves of Keshcorran (), are a series of

The first thorough exploration of the caves at Keshcorran occurred during five weeks in 1901, and was initiated after a portion of a bear's skull had been discovered some years earlier. These excavations, headed by Robert Francis Scharff, R. J. Ussher, and

The first thorough exploration of the caves at Keshcorran occurred during five weeks in 1901, and was initiated after a portion of a bear's skull had been discovered some years earlier. These excavations, headed by Robert Francis Scharff, R. J. Ussher, and

The Memoirs of Gabriel Beranger

', p. 48

PDF here

/ref>

limestone caves

Limestone is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Limestone forms when t ...

located near the village of Keash, County Sligo

County Sligo ( , ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region and is part of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in ...

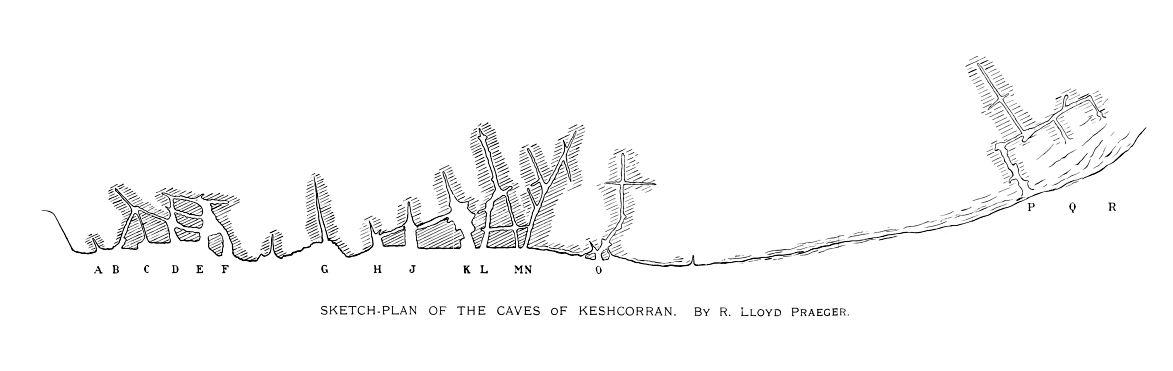

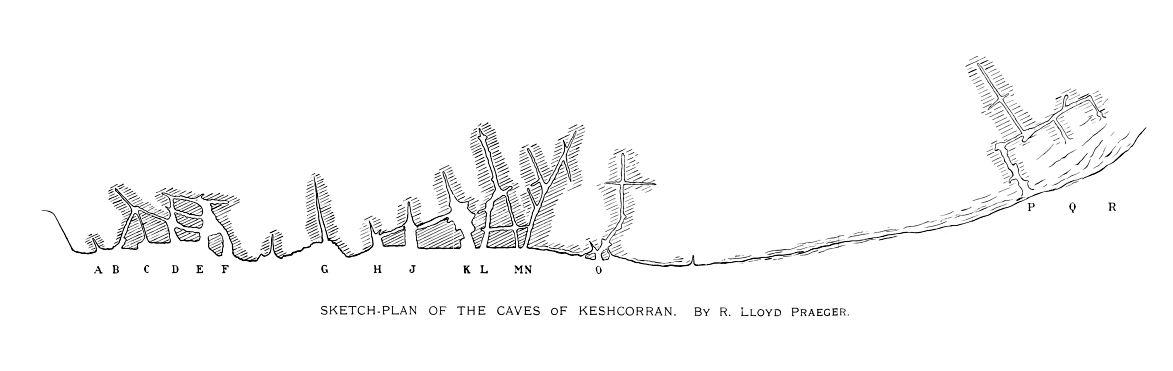

, Ireland. The caves are situated on the west side of Keshcorran Hill (part of the Bricklieve Mountains) and consist of sixteen simple chambers, some interconnecting.

The caves have been used by man over several millennia, and it has long been suggested that they were the site of ancient religious practice or gathering such as Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh, Lughnasa or Lúnasa ( , ) is a Gaels, Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Traditionally, it is held on 1 August, or abo ...

.

Excavations carried out in the early 20th century, particularly those by Robert Francis Scharff, discovered significant animal remains. Among others, these included bones of brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear native to Eurasia and North America. Of the land carnivorans, it is rivaled in size only by its closest relative, the polar bear, which is much less variable in size and slightly bigger on av ...

, arctic lemming

The Arctic lemming (''Dicrostonyx torquatus'') is a species of rodent in the family Cricetidae.

Although generally classified as a "least concern" species, the Novaya Zemlya subspecies ''(Dicrostonyx torquatus ungulatus)'' is considered a vulne ...

, Irish elk, and grey wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

.

Geology

The sixteen interconnecting caves of white cherty limestone are found at the base of a line of low cliffs, on the western slope of the hill. They were formed from the atmospheric weathering of carboniferous limestone, and run perpendicular to the rock face.Quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

crystals are abundant, and glacial boulder-beds can be found at the mouth of some of the caves, showing that Keshcorran was at one time buried beneath an ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

.Scharff, Robert Francis (1903), ''The Exploration of the Caves of Kesh, County Sligo]'' The caves bear evidence of being washed out by water, and a layer of breccia

Breccia ( , ; ) is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or Rock (geology), rocks cementation (geology), cemented together by a fine-grained matrix (geology), matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language ...

containing limestone blocks can be found in many of them. Stalagmite floors are rare, and when present appear to have been burrowed into by foxes and badgers.Gwynn, Arthur Montague (1940), ''Report on a Further Exploration (1929) of the Caves of Keshcorran, Co. Sligo''

History of exploration

The first thorough exploration of the caves at Keshcorran occurred during five weeks in 1901, and was initiated after a portion of a bear's skull had been discovered some years earlier. These excavations, headed by Robert Francis Scharff, R. J. Ussher, and

The first thorough exploration of the caves at Keshcorran occurred during five weeks in 1901, and was initiated after a portion of a bear's skull had been discovered some years earlier. These excavations, headed by Robert Francis Scharff, R. J. Ussher, and Robert Lloyd Praeger

Robert Lloyd Praeger (25 August 1865 – 5 May 1953) was an Irish naturalist, writer and librarian.

Biography Early life and education

From a Unitarian background, he was born and raised in Holywood, County Down; he had four brothers and a ...

, recovered bones of deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

, ox, goat, pig, bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

, horse, sheep, donkey, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores and live Solitary animal, solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are precociality, able to fend for themselves ...

, mouse, rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

, badger, fox, dog, wolf

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a Canis, canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of Canis lupus, subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, includin ...

, and stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine or ermine, is a species of mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern regions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Concern on th ...

. For the first time in Ireland, evidence of the Arctic lemming

The Arctic lemming (''Dicrostonyx torquatus'') is a species of rodent in the family Cricetidae.

Although generally classified as a "least concern" species, the Novaya Zemlya subspecies ''(Dicrostonyx torquatus ungulatus)'' is considered a vulne ...

was also discovered, drawing headlines around the country. Another important recovery was that of a metacarpus of reindeer, discovered above an area of burnt charcoal. This suggests that reindeer in Ireland survived until the human period.

Also recovered from the excavations were the four oldest species of molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

found in Ireland at the time, the remains of several fish, and numerous species of bird, most notably the ptarmigan

''Lagopus'' is a genus of birds in the grouse subfamily commonly known as ptarmigans (). The genus contains four living species with numerous described subspecies, all living in tundra or cold upland areas.

Taxonomy and etymology

The genus ''L ...

, smew

The smew (''Mergellus albellus'') is a species of duck and is the only living member of the genus ''Mergellus''. ''Mergellus'' is a diminutive of ''Mergus'' and ''albellus'' is from Latin ''albus'' "white". This genus is closely related to ''Me ...

, and little auk

The little auk (Europe) or dovekie (North America) ''Alle alle'' is a small auk, the only member of the genus ''Alle''. ''Alle'' is the Sami name of the long-tailed duck; it is onomatopoeic and imitates the call of the drake duck. Linnaeus was n ...

. Another recovery of note was that of several fossilised frog bones found in the lowest stratum, which disproved a common belief that the species had only been introduced in 1699.

Finally, the excavations found evidence of occasional human habitation going as far back as the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

, with more regular occupation being identified from the 10th century onward. Five human teeth and the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

of a male were found in the caves, and man-made artefacts that were recovered include two bone needles, a bone comb, a stone celt

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

, an iron saw, two bronze pins, and a stone axe of adze

An adze () or adz is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing or carving wood in ha ...

type. Shells of mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

and oyster were also found, further supporting human settlement.

Further explorations took place in 1929 and 1930, and these led to the recovery of more bones of lemming, reindeer, mouse, pig, hare, horse, frog, rabbit, sheep, fox, stoat, bear, dog, ox, badger and rat. The excavations also discovered remains of elk, cat, shrew, and duck.

In more recent times, some of the mammal bones recovered from these excavations have been re-analysed with radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

, confirming a late-glacial estimate for the bones found in the lower layers. Those of the bear, deer, hare, and wolf were dated to around 10,000 BC, while those of the stoat and horse were dated to around 6000 BC and 400 BC respectively.

The most recent discovery from the caves occurred in 1971, when a left tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

of an adult was recovered in a pool of water. It has subsequently been dated to the turn of the 11th century, coinciding with an entry in the Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' () or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' () are chronicles of Middle Ages, medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Genesis flood narrative, Deluge, dated as 2,242 Anno Mundi, years after crea ...

for 1007 AD;

: ''"Muireadhach, a distinguished bishop, son of the brother of Ainmire Bocht, was suffocated in a cave, in Gaileanga of Corann."''

Folklore and mythology

The Kesh Caves featured prominently in medievalmyths

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

and stories, with folk versions of these tales continuing in oral transmission Oral transmission, literally meaning "passing by mouth", may refer to:

*Oral tradition of stories, texts, music, laws and other cultural elements

** Oral gospel traditions, referring specifically to the Christian Gospels

*Pathogen transmission

...

until the 20th century. The caves are often presented as being associated with the otherworld

In historical Indo-European religion, the concept of an otherworld, also known as an otherside, is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other world/side"), a term used by Lucan in his desc ...

, and as places to be respected and feared. '' Cath Maige Mucrama'' tells of the birth of Cormac mac Airt

Cormac mac Airt, also known as Cormac ua Cuinn (grandson of Conn) or Cormac Ulfada (long beard), was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He is probably the most famous of the ancient High Kings ...

at the foot of Keshcorran. He is reputed to have been raised by a wolf in the caves, in a tale reminiscent of Romulus and Remus

In Roman mythology, Romulus and (, ) are twins in mythology, twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the Founding of Rome, founding of the History of Rome, city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his frat ...

.

The caves also feature in three stories about Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill, often anglicised Finn McCool or MacCool, is a hero in Irish mythology, as well as in later Scottish and Manx folklore. He is the leader of the ''Fianna'' bands of young roving hunter-warriors, as well as being a seer a ...

. The first, found in Duanaire Finn, relates a journey by Fionn to an otherworld smithy located inside the caves. The second tale, known as ''Bruidhean Cheise Corainn'', tells of the warrior being captured and bound in the caves by the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuatha Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deities of pre-Christian Gaelic ...

. Another tale, ''the Death of Diarmuid in the Boar Hunt'', mentions Diarmuid and Gráinne as taking refuge in the caves from a vengeful Fionn.

A more modern tale regarding the caves of Keshcorran can be found in a 1779 diary of Gabriel Beranger;

: ''"This cavern is said to communicate with that in the county of Roscommon ... called the Hellmouth door of Ireland t Rathcroghan of which is told (and believed in both counties) that a woman in the county of Roscommon having an unruly calf could never get him home unless driving him by holding him by the tail; that one day he tried to escape and dragged the woman, against her will into the Hellmouth door ... and continued running until next morning. She came out at Kishcorren ic to her own amazement and that of the neighbouring people. We believed it rather than try it."'' Wilde, William (1880), The Memoirs of Gabriel Beranger

', p. 48

PDF here

/ref>

References

{{reflist Geography of County Sligo Caves of the Republic of Ireland