Catharism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in

The Cathars also refused the sacrament of the

The Cathars also refused the sacrament of the

Catharism has been seen as giving women the greatest opportunities for independent action, since women were found as being believers as well as Perfecti, who were able to administer the sacrament of the ''consolamentum''.

Cathars believed that a person would be repeatedly reincarnated until they committed to self-denial of the material world. A man could be reincarnated as a woman and vice versa. The spirit was of utmost importance to the Cathars and was described as being immaterial and sexless. Because of this belief, the Cathars saw women as equally capable of being spiritual leaders.

Women accused of being

Catharism has been seen as giving women the greatest opportunities for independent action, since women were found as being believers as well as Perfecti, who were able to administer the sacrament of the ''consolamentum''.

Cathars believed that a person would be repeatedly reincarnated until they committed to self-denial of the material world. A man could be reincarnated as a woman and vice versa. The spirit was of utmost importance to the Cathars and was described as being immaterial and sexless. Because of this belief, the Cathars saw women as equally capable of being spiritual leaders.

Women accused of being

In 1147,

In 1147,

In January 1208, the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, a

In January 1208, the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, a  This war pitted the nobles of France against those of the Languedoc. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree that permitted the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. This angered not only the lords of the south, but also the King Philip II of France, who was at least nominally the

This war pitted the nobles of France against those of the Languedoc. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree that permitted the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. This angered not only the lords of the south, but also the King Philip II of France, who was at least nominally the

The official war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France dispossessed the House of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs, and the house of the Trencavels of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. In spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished, and Catholic forces would continue to pursue Cathars.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the

The official war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France dispossessed the House of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs, and the house of the Trencavels of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. In spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished, and Catholic forces would continue to pursue Cathars.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the  A popular though as yet unsubstantiated belief holds that a small party of Cathar Perfects escaped from the fortress prior to the massacre at . It is widely held in the Cathar region to this day that the escapees took with them "the Cathar treasure". What this treasure consisted of has been a matter of considerable speculation: claims range from sacred Gnostic texts to the Cathars' accumulated wealth, which might have included the

A popular though as yet unsubstantiated belief holds that a small party of Cathar Perfects escaped from the fortress prior to the massacre at . It is widely held in the Cathar region to this day that the escapees took with them "the Cathar treasure". What this treasure consisted of has been a matter of considerable speculation: claims range from sacred Gnostic texts to the Cathars' accumulated wealth, which might have included the

The term , French meaning "Cathar Country", is used to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the region in which Catharism was traditionally strongest. The area is centered around fortresses such as Montségur and Carcassonne; also, the French departments of France, département of the Aude uses the title in tourist brochures. The areas have ruins from the wars against the Cathars that are still visible today.

The term , French meaning "Cathar Country", is used to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the region in which Catharism was traditionally strongest. The area is centered around fortresses such as Montségur and Carcassonne; also, the French departments of France, département of the Aude uses the title in tourist brochures. The areas have ruins from the wars against the Cathars that are still visible today.

Jean Duvernoy, Jean: transcriptions of inquisitorial manuscripts

many hitherto unpublished * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . A collection of primary sources, some on Catharism. * * * * * * * * AVSA9873 A+C * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ce lieu est terrible, le Mont-Aimé en Champagne

Vendredi 13 mai 1239 Réf : Bibliothèque Nationale de France * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

, particularly in northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

and southern France

Southern France, also known as the south of France or colloquially in French as , is a geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', Atlas e ...

, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a heretical sect by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, its followers were attacked first by the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

and later by the Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition was a series of Inquisitions (Catholic Church bodies charged with suppressing heresy) from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). The Medieval Inquisition ...

, which eradicated the sect by 1350. Around 1 million were slaughtered, hanged, or burnt at the stake.

Followers were known as Cathars or Albigensians, after the French city Albi

Albi (; ) is a commune in France, commune in southern France. It is the prefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department, on the river Tarn (river), Tarn, 85 km northeast of Toulouse. Its inhabitants are called ...

where the movement first took hold, but referred to themselves as Good Christians. They famously believed that there were not one, but two Godsthe good God of Heaven and the evil god of this age (). According to tradition, Cathars believed that the good God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

was the God of the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

faith and creator of the spiritual realm. Many Cathars identified the evil god as Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

, the master of the physical world. The Cathars believed that human souls were the sexless spirits of angels trapped in the material realm of the evil god. They thought these souls were destined to be reincarnated until they achieved salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

through the " consolamentum", a form of baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

performed when death is imminent. At that moment, they believed they would return to the good God as " Cathar Perfect". Catharism was initially taught by ascetic leaders who set few guidelines, leading some Catharist practices and beliefs to vary by region and over time.

The first mention of Catharism by chroniclers was in 1143; four years later the Catholic Church denounced Cathar practices, particularly the ''consolamentum'' ritual. From the beginning of his reign, Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

attempted to end Catharism by sending missionaries and persuading the local authorities to act against the Cathars. In 1208, Pierre de Castelnau, Innocent's papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, was murdered while returning to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

after excommunicating Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, who, in his view, was too lenient with the Cathars. Pope Innocent III then declared de Castelnau a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

and launched the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

in 1209. The nearly twenty-year campaign succeeded in vastly weakening the movement. The Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition was a series of Inquisitions (Catholic Church bodies charged with suppressing heresy) from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). The Medieval Inquisition ...

that followed ultimately eradicated Catharism.

There is academic controversy about whether Catharism was a organized religion or whether the medieval Church imagined or exaggerated it. The lack of any central organisation among Cathars and regional differences in beliefs and practices has prompted some scholars to question whether the Church exaggerated its threat while others wonder whether it even existed.

Term

Though the term ''Cathar'' () has been used for centuries to identify the movement, whether it identified itself with the name is debated. In Cathar texts, the terms ''Good Men'' (), ''Good Women'' (), or ''Good Christians'' () are the common terms of self-identification. In the testimony of suspects who were put to the question by the Inquisition, the term 'Cathar' was not used amongst the group of accused heretics themselves. The word 'Cathar' (aka. Gazarri etc.) is coined by Catholic theologians and used exclusively by the inquisition or by authors otherwise identified with the Orthodox church—for example in the anonymous pamphlet of 1430, ''Errores Gazariorum'' (Re: ''Errors of the Cathars''). The full title of this treatise in English is, "''The errors of the Gazarri, or of those who travel riding a broom or a stick."'' However the presence of a variety of beliefs and spiritual practices in the French countryside of the 12th and 13th centuries that came to be seen as heterodox relative to the Church in Rome is not actually in question, as the primary documents of the period exhaustively demonstrate. Several of these groups under other names, e.g. theWaldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

or Valdeis, bear a close similarity to the 'creed' or matrix of beliefs and folk-traditions pieced together under the umbrella of the term 'Catharism.' The fact that there was clearly a spiritual and communal movement of some sort can scarcely be denied since legions of people were willing to part with their lives to defend it. Whether they acted in defense of the doctrine or in defense of the human community who held these beliefs, the fact that many gave themselves up willingly to the flames when the option to recant was given to them in many or most cases is significant.

As the scholar Claire Taylor puts it, " his issuematters at an ethical level, because by being cleverly iconoclastic and populist in suggesting that those using 'Cathar' have made 2+2=5, Pegg and Moore e: scholars questioning whether or not the Cathars existmake 2+2=3 by denying the existence of the persecuted group. The missing element is a dissident religious doctrine, for which historians using a fuller range of sources believe thousands of people were prepared to suffer extreme persecution and an agonising death."

Origins

The origins of the Cathars' beliefs are unclear, but most theories agree they came from theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, mostly by the trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a singl ...

s and spread from the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire (; was a medieval state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 680–681 after part of the Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, Asparuh, moved south to the northe ...

to the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. The movement was greatly influenced by the Bogomils

Bogomilism (; ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic, dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Peter I in the 10th century. I ...

of the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire (; was a medieval state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 680–681 after part of the Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, Asparuh, moved south to the northe ...

, and may have originated in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, namely through adherents of the Paulician movement in Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

and eastern Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

who were resettled in Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

( Philippopolis).

The name of Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

() was also applied to the Albigensians, and they maintained an association with the similar Christian movement of the Bogomils

Bogomilism (; ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic, dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Peter I in the 10th century. I ...

("Friends of God") of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

. "That there was a substantial transmission of ritual and ideas from Bogomilism to Catharism is beyond reasonable doubt." Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the Bogomils and the Paulicians, who influenced them, as well as the earlier Marcianists, who were found in the same areas as the Paulicians, the Manicheans and the Christian Gnostics

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

of the first few centuries AD, although, as many scholars, most notably Mark Pegg, have pointed out, it would be erroneous to extrapolate direct, historical connections based on theoretical similarities perceived by modern scholars.

John Damascene, writing in the 8th century AD, also notes of an earlier sect called the "Cathari", in his book ''On Heresies'', taken from the epitome provided by Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis (; – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the Christianity in the 4th century, 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic Churche ...

in his ''Panarion

In early Christianity, early Christian heresiology, the ''Panarion'' (, derived from Latin , meaning "bread basket"), to which 16th-century Latin translations gave the name ''Adversus Haereses'' (Latin: "Against Heresies"), is the most important o ...

''. He says of them: "They absolutely reject those who marry a second time, and reject the possibility of penance hat is, forgiveness of sins after baptism. These are probably the same Cathari (actually Novations) who are mentioned in Canon 8 of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in the year 325, which states "... those called Cathari come over o the faith

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), ...

let them first make profession that they are willing to communicate hare full communion">full_communion.html" ;"title="hare full communion">hare full communionwith the twice-married, and grant pardon to those who have lapsed ..."

The writings of the Cathars were mostly destroyed because of the doctrine's threat perceived by the Papacy; thus, the historical record of the Cathars is derived primarily from their opponents. Cathar ideology continues to be debated, with commentators regularly accusing opposing perspectives of speculation, distortion and bias. Only a few texts of the Cathars remain, as preserved by their opponents (such as the ) which give a glimpse into the ideologies of their faith. One large text has survived, ''The Book of Two Principles'' (), which elaborates the principles of dualistic theology from the point of view of some Albanenses Cathars.

It is now generally agreed by most scholars that identifiable historical Catharism did not emerge until at least 1143, when the first confirmed report of a group espousing similar beliefs is reported being active at Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

by the cleric

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

Eberwin of Steinfeld. A landmark in the "institutional history" of the Cathars was the Council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

, held in 1167 at Saint-Félix-Lauragais, attended by many local figures and also by the Bogomil

Bogomilism (; ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic, dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Peter I in the 10th century. I ...

''papa'' Nicetas, the Cathar bishop of (northern) France and a leader of the Cathars of Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

.

The Cathars were a largely local, Western European/Latin Christian phenomenon, springing up in the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

cities, particularly Cologne, in the mid-12th century

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar.

In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and overlaps with what is often called the Golden Age' of the ...

, northern France around the same time, and particularly the Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

—and the northern Italian cities in the mid-late 12th century. In the Languedoc and northern Italy, the Cathars attained their greatest popularity, surviving in the Languedoc, in much reduced form, up to around 1325 and in the Italian cities until the Inquisitions of the 14th century extirpated them.

Catharism is generally believed to be a syncretic form of Zoroastrianism and Gnosticism and the heir to Manichaeism.

Beliefs

Cosmology

Gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

cosmology identified two creator deities. The first was the creator of the spiritual realm contained in the New Testament, while the second was the demiurge depicted in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

who created the physical universe. The demiurge, often called ("King of the World"), was identified as the God of Judaism.

Some gnostic belief systems including Catharism began to characterise the duality of creation as a relationship between hostile opposing forces of good and evil. Although the demiurge was sometimes conflated with Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

or considered Satan's father, creator or seducer, these beliefs were far from unanimous. Some Cathar communities believed in a mitigated dualism similar to their Bogomil

Bogomilism (; ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic, dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Peter I in the 10th century. I ...

predecessors, stating that the evil god Satan had previously been the true God's servant before rebelling against him. Others, likely a majority over time given the influence reflected on the ''Book of the Two Principles'', believed in an absolute dualism, where the two gods were twin entities of the same power and importance.

All visible matter, including the human body, was created or crafted by this ; matter was therefore tainted with sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

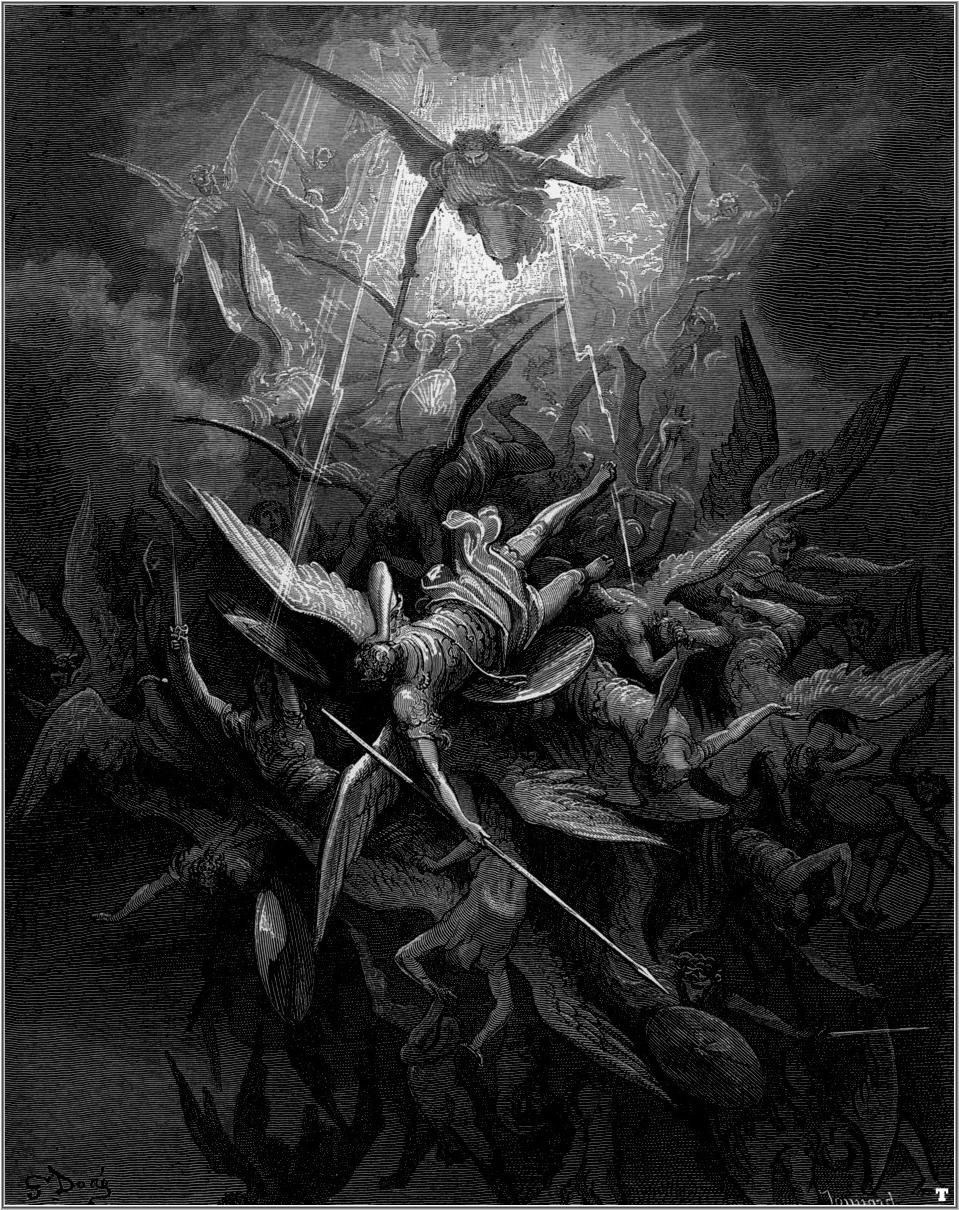

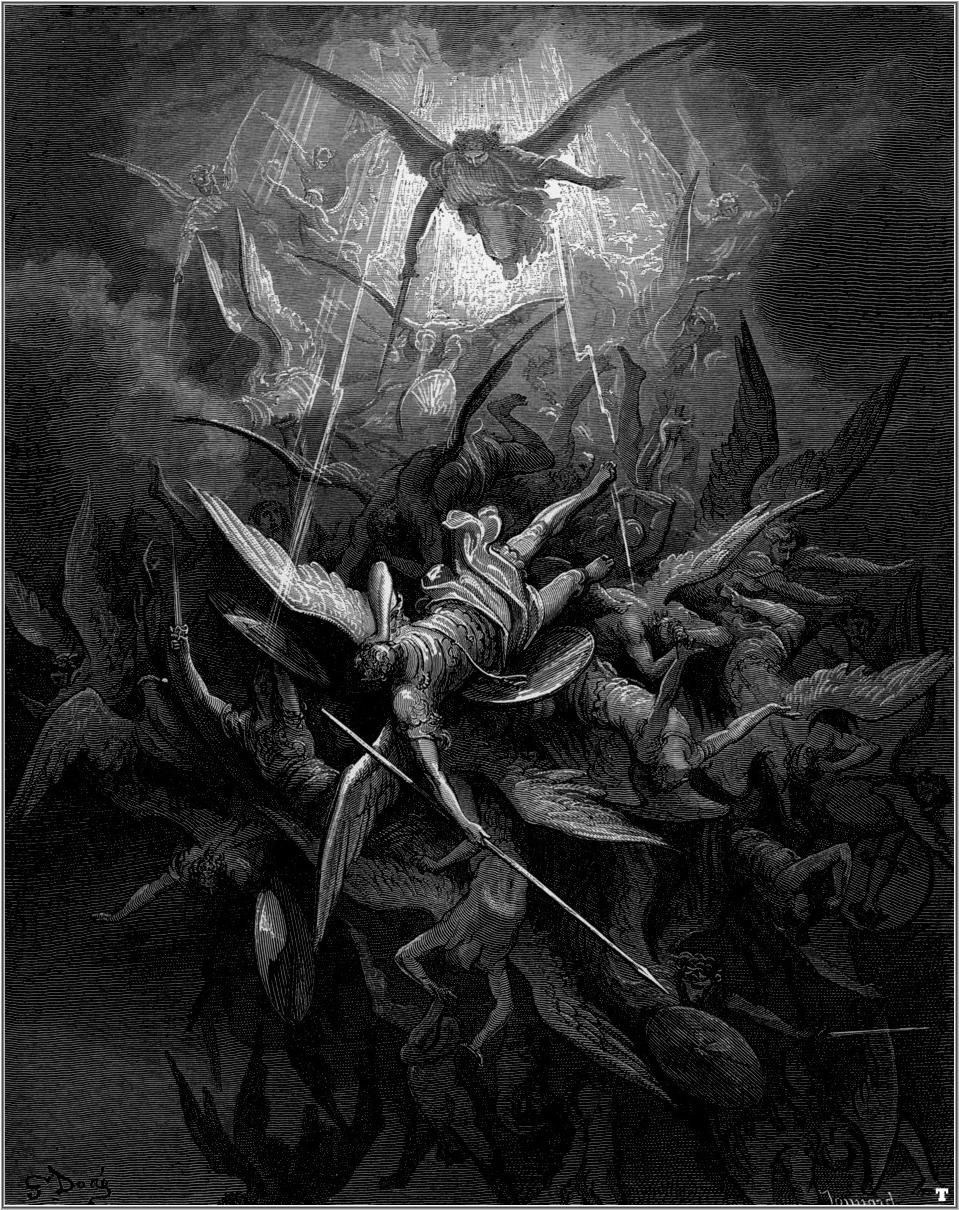

. Under this view, humans were actually angels seduced by Satan before a war in heaven

The War in Heaven is a mythical conflict between supernatural forces in traditional Christian cosmology, attested in the Book of Revelation alongside proposed parallels in the Hebrew Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is described as the res ...

against the army of Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* he He ..., a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name

* Michael (bishop elect)">Michael (surname)">he He ..., a given nam ...

, after which they would have been forced to spend an eternity trapped in the evil God's material realm. The Cathars taught that to regain angelic status one had to renounce the material self completely. Until one was prepared to do so, they would be stuck in a cycle of reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the Philosophy, philosophical or Religion, religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new lifespan (disambiguation), lifespan in a different physical ...

, condemned to suffer endless human lives on the corrupt Earth.

Zoé Oldenbourg compared the Cathars to "Western Buddhists" because she considered that their view of the doctrine of "resurrection" in Christianity was similar to the Buddhist doctrine of rebirth.

Christology

Cathars veneratedJesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

and followed what they considered to be his true teachings, labelling themselves as "Good Christians". However, they denied his physical incarnation and Resurrection. Authors believe that their conception of Jesus resembled Docetism, believing him the human form of an angel, whose physical body was only an appearance. This illusory form would have possibly been given by the Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, another angel in human form, or possibly a human born of a woman with no involvement of a man.

They firmly rejected the Resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus () is Christianity, Christian belief that God in Christianity, God Resurrection, raised Jesus in Christianity, Jesus from the dead on the third day after Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion, starting—or Preexis ...

, seeing it as representing reincarnation, and the Christian symbol of the cross, considering it to be no more than a material instrument of torture and evil. They also saw John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

, identified as the same entity as the prophet Elijah

Elijah ( ) or Elias was a prophet and miracle worker who lived in the northern kingdom of Israel during the reign of King Ahab (9th century BC), according to the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible.

In 1 Kings 18, Elijah defended the worsh ...

, as an evil being sent to hinder Jesus's teaching through the false sacrament of baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

. For the Cathars, the "resurrection" mentioned in the New Testament was only a symbol of re-incarnation.

Most Cathars did not accept the normative Trinitarian understanding of Jesus, instead resembling nontrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ( ...

modalistic Monarchianism

Modalistic Monarchianism, also known as Modalism or Oneness Christology, is a Christian theology upholding the unipersonal oneness of God while also affirming the divinity of Jesus. As a form of Monarchianism, it stands in contrast with Dynamic M ...

( Sabellianism) in the West and adoptionism

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an early Christian nontrinitarian theological doctrine, subsequently revived in various forms, which holds that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ...

in the East, which might or might not be combined with the mentioned Docetism. Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

's biographer and other sources accuse some Cathars of Arianism

Arianism (, ) is a Christology, Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius (). It is co ...

, and some scholars see Cathar Christology as having traces of earlier Arian roots.

Some communities might have believed in the existence of a spirit realm created by the good God, the "Land of the Living", whose history and geography would have served as the basis for the evil god's corrupt creation. Under this view, the history of Jesus would have happened roughly as told, only in the spirit realm. The physical Jesus from the material world would have been evil, a false messiah and a lustful lover of the material Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cr ...

. However, the true Jesus would have influenced the physical world in a way similar to the Harrowing of Hell

In Christian theology, the Harrowing of Hell (; Greek language, Greek: – "the descent of Christ into Christian views on Hell, Hell" or Christian views on Hades, Hades) is the period of time between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his Resurre ...

, only by inhabiting the body of Paul. 13th century chronicler Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay recorded those views.

Other beliefs

Some Cathars told a version of the Enochian narrative, according to whichEve

Eve is a figure in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. According to the origin story, "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develop through oral traditions and there ...

's daughters copulated with Satan's demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in folklore, mythology, religion, occultism, and literature; these beliefs are reflected in Media (communication), media including

f ...

s and bore giants

A giant is a being of human appearance, sometimes of prodigious size and strength, common in folklore.

Giant(s) or The Giant(s) may also refer to:

Mythology and religion

*Giants (Greek mythology)

* Jötunn, a Germanic term often translated as 'g ...

. The Deluge

A deluge is a large downpour of rain, often a flood.

The Deluge refers to the flood narrative in the biblical book of Genesis.

Deluge or Le Déluge may also refer to:

History

*Deluge (history), the Swedish and Russian invasion of the Polish-L ...

would have been provoked by Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

, who disapproved of the demons revealing he was not the real god, or alternatively, an attempt by the Invisible Father to destroy the giants. The Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

was sometimes counted as one single entity, but to others it was considered the collective groups of unfallen angels who had not followed Satan in his rebellion.

Cathars believed that the sexual allure of women impeded a man's ability to reject the material world. Despite this stance on sex and reproduction, some Cathar communities made exceptions. In one version, the Invisible Father had two spiritual wives, Collam and Hoolibam (identified with Oholah and Oholibah), and would himself have provoked the war in heaven by seducing the wife of Satan, or perhaps the reverse. Cathars adhering to this story would believe that having families and sons would not impede them from reaching God's kingdom.

Some communities also believed in a Day of Judgment that would come when the number of the just equalled that of angels who fell, when the believers would ascend to the spirit realm, while the sinners would be thrown to everlasting fire along with Satan.

The Cathars ate a pescatarian diet. They did not eat cheese, eggs, meat, or milk because these are all by-products of sexual intercourse. The Cathars believed that animals were carriers of reincarnated souls, and forbade the killing of all animal life, apart from fish, which they believed were produced by spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

.

The Cathars could be seen as prefiguring Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

in that they denied transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

, purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

, prayers for the dead and prayers to saints. They also believed that the scriptures should be read in the vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

.

Texts

The alleged sacred texts of the Cathars, besides the New Testament, included theBogomil

Bogomilism (; ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic, dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Peter I in the 10th century. I ...

text '' The Gospel of the Secret Supper'' (also called ''John's Interrogation''), a modified version of '' Ascension of Isaiah'', and the Cathar original work ''The Book of the Two Principles'' (possibly penned by Italian Cathar John Lugio of Bergamo). They regarded the Old Testament as written by Satan, except for a few books which they accepted, and considered the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

not a prophecy about the future, but an allegorical chronicle of what had transpired in Satan's rebellion. Their reinterpretation of those texts contained numerous elements characteristic of Gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

literature.

Organization

Sacraments

Cathars, in general, formed an anti- sacerdotal party in opposition to the pre-Reformation Catholic Church, protesting against what they perceived to be the moral, spiritual and political corruption of the Church. In contrast, the Cathars had but one central rite, the Consolamentum, or Consolation. This involved a brief spiritual ceremony to remove all sin from the believer and to induct him into the next higher level as a Perfect. Many believers would receive the Consolamentum as death drew near, performing the ritual of liberation at a moment when the heavy obligations of purity required of Perfecti would be temporally short. Some of those who received the sacrament of the consolamentum upon their death-beds may thereafter have shunned further food with an exception of cold water until death. This has been termed the . It was claimed by some of the church writers that when a Cathar, after receiving the Consolamentum, began to show signs of recovery he or she would be smothered in order to ensure his or her entry into paradise. Other than extreme cases, little evidence exists to suggest this was a common Cathar practice. The Cathars also refused the sacrament of the

The Cathars also refused the sacrament of the eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

, saying that it could not possibly be the body of Christ. They also refused to partake in the practice of Baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

by water. The following two quotes are taken from the Inquisitor Bernard Gui's experiences with the Cathar practices and beliefs:

Social relationships

Killing was abhorrent to the Cathars. Consequently, abstention from all animal food, sometimes exempting fish, was enjoined of the Perfecti. The Perfecti avoided eating anything considered to be a by-product of sexual reproduction. War andcapital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

were condemned—an abnormality in Medieval Europe, despite the fact that the sect had armed combatants prepared to engage in combat and commit murder on its behalf. For example, the Papal Legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, Pierre de Castelnau, was assassinated in January 1208 in Provence.

To the Cathars, reproduction was a moral evil to be avoided, as it continued the chain of reincarnation and suffering in the material world. Such was the situation that a charge of heresy levelled against a suspected Cathar was usually dismissed if the accused could show he was legally married.

Despite the implicit anti-Semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

of their views on the Old Testament God, the Cathars had little hostility to Jews as an ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

: probably, Jews had a higher status in Cathar territories than they had elsewhere in Europe at the time. Cathars appointed Jews as bailiffs and to other roles as public officials, which further increased the Catholic Church's anger at the Cathars.

Despite their condemnation of reproduction, the Cathars grew in numbers in southeastern France. By 1207, shortly before the murder of the Papal Legate Castelnau, many towns in that region, i.e. Provence and its vicinity, were almost completely populated by Cathari, and the Cathari population had many ties to nearby communities. When Bishop Fulk of Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, a key leader of the anti-Cathar persecutions, excoriated the Languedoc Knights for not pursuing the heretics more diligently, he received the reply, "We cannot. We have been reared in their midst. We have relatives among them and we see them living lives of perfection."

Hierarchy

It has been alleged that the Cathar Church of the Languedoc had a relatively flat structure, distinguishing between the baptised (a term they did not use; instead, ) and ordinary unbaptised believers (). By about 1140, liturgy and a system of doctrine had been established. They created a number ofbishoprics

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

, first at Albi

Albi (; ) is a commune in France, commune in southern France. It is the prefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department, on the river Tarn (river), Tarn, 85 km northeast of Toulouse. Its inhabitants are called ...

around 1165 and after the 1167 Council at Saint-Félix-Lauragais sites at Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, Carcassonne

Carcassonne is a French defensive wall, fortified city in the Departments of France, department of Aude, Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the department.

...

, and Agen

Agen (, , ) is the prefecture of the Lot-et-Garonne department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Southwestern France. It lies on the river Garonne, southeast of Bordeaux. In 2021, the commune had a population of 32,485.

Geography

The city of Agen l ...

, so that four bishoprics were in existence by 1200.

In about 1225, during a lull in the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

, the bishopric of Razès was added. Bishops were supported by their two assistants: a (typically the successor) and a , who were further assisted by deacons. The were the spiritual elite, highly respected by many of the local people, leading a life of austerity and charity. In the apostolic fashion, they ministered to the people and travelled in pairs.

Role of women

heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

in early medieval Christianity included those labelled Gnostics

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

, Cathars, and, later, the Beguines, as well as several other groups that were sometimes "tortured and executed". Cathars, like the Gnostics who preceded them, assigned more importance to the role of Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cr ...

in the spread of early Christianity than the church previously did. Her vital role as a teacher contributed to the Cathar belief that women could serve as spiritual leaders. Women were included in the Perfecti in significant numbers, with numerous receiving the after being widowed. Having reverence for the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

, the Cathars saw Mary Magdalene as perhaps even more important than Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

, the founder of the church.

Catharism attracted numerous women with the promise of a leadership role that the Catholic Church did not allow. Catharism let women become a Perfect. These female Perfects were required to adhere to a strict and ascetic lifestyle, but were still able to have their own houses. Although many women found something attractive in Catharism, not all found its teachings convincing. A notable example is Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen Benedictines, OSB (, ; ; 17 September 1179), also known as the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictines, Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mysticism, mystic, visiona ...

, who in 1163 gave a rousing exhortation against the Cathars in Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

. During this discourse, Hildegard announced God's eternal damnation

Damnation (from Latin '' damnatio'') is the concept of divine punishment after death for sins that were committed, or in some cases, good actions not done, on Earth.

In Ancient Egyptian religious tradition, it was believed that citizens woul ...

on all who accepted Cathar beliefs.

While women Perfects rarely travelled to preach the faith, they still played a vital role in the spreading of Catharism by establishing group homes for women. Though it was extremely uncommon, there were isolated cases of female Cathars leaving their homes to spread the faith. In Cathar communal homes (ostals), women were educated in the faith. These women would go on to bear children who would then become believers. Through this pattern, the faith grew exponentially through the efforts of women, as each generation passed.

Despite women having a role in the growth of the faith, Catharism was not completely equal. For example, the belief that one's last incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It is the Conception (biology), conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or an Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic form of a god. It is used t ...

had to be experienced as a man to break the cycle. This belief was inspired by later French Cathars, who taught that women must be reborn as men in order to achieve salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

. Toward the end of the Cathar movement, Catharism became less equal and started the practice of excluding women Perfects. However, this trend remained limited. For example, later on, Italian Perfects still included women.

Suppression

In 1147,

In 1147, Pope Eugene III

Pope Eugene III (; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He was the first Cist ...

sent a legate to the Cathar district in order to arrest the progress of the Cathars. The few isolated successes of Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

could not obscure the poor results of this mission, which clearly showed the power of the sect in the Languedoc at that period. The missions of Cardinal Peter of Saint Chrysogonus to Toulouse and the Toulousain in 1178, and of Henry of Marcy, cardinal-bishop of Albano, in 1180–81, obtained merely momentary successes. Henry's armed expedition, which took the stronghold at Lavaur, did not extinguish the movement.

Decisions of Catholic Church councils—in particular, those of the Council of Tours (1163) and of the Third Council of the Lateran

The Third Council of the Lateran met in Rome in March 1179. Pope Alexander III presided and 302 bishops attended. The Catholic Church regards it as the eleventh ecumenical council.

By agreement reached at the Peace of Venice in 1177 the bitt ...

(1179)—had scarcely more effect upon the Cathars. When Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

came to power in 1198, he was resolved to deal with them.

At first, Innocent tried peaceful conversion, and sent a number of legates into the Cathar regions. They had to contend not only with the Cathars, the nobles who protected them, and the people who respected them, but also with many of the bishops of the region, who resented the considerable authority the Pope had conferred upon his legates. In 1204, Innocent III suspended a number of bishops in Occitania

Occitania is the historical region in Southern Europe where the Occitan language was historically spoken and where it is sometimes used as a second language. This cultural area roughly encompasses much of the southern third of France (except ...

. In 1205, he appointed a new and vigorous bishop of Toulouse

The Archdiocese of Toulouse (–Saint Bertrand de Comminges–Rieux) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese comprises the Department of Haute-Garonne and its seat is Toulouse Cathedral. Archbi ...

, the former troubadour

A troubadour (, ; ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a ''trobairitz''.

The tr ...

Foulques. In 1206, Diego of Osma and his canon, the future Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic, (; 8 August 1170 – 6 August 1221), also known as Dominic de Guzmán (), was a Castilians, Castilian Catholic priest and the founder of the Dominican Order. He is the patron saint of astronomers and natural scientists, and he a ...

, began a programme of conversion in Languedoc. As part of this, Catholic–Cathar public debates were held at Verfeil, Servian, Pamiers, Montréal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

and elsewhere.

Dominic met and debated with the Cathars in 1203 during his mission to the Languedoc. He concluded that only preachers who displayed real sanctity, humility and asceticism could win over convinced Cathar believers. The institutional Church as a general rule did not possess these spiritual warrants. His conviction eventually led to the establishment of the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic Church, Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilians, Castilian priest named Saint Dominic, Dominic de Gu ...

in 1216. The order was to live up to the terms of his rebuke, "Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth." However, even Dominic managed only a few converts among the Cathars.

Albigensian Crusade

In January 1208, the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, a

In January 1208, the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, a Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

monk, theologian and canon lawyer, was sent to meet the ruler of the area, Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse

Raymond VI (; 27 October 1156 – 2 August 1222) was Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence from 1194 to 1222. He was also Count of Melgueil (as Raymond IV) from 1173 to 1190.

Early life

Raymond was born at Saint-Gilles, Gard, the son of ...

. Known for excommunicating noblemen who protected the Cathars, Castelnau excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in communion with other members of the con ...

Raymond for abetting heresy, following an allegedly fierce argument during which Raymond supposedly threatened Castelnau with violence. Shortly thereafter, Castelnau was murdered as he returned to Rome, allegedly by a knight in the service of Count Raymond. His body was returned and laid to rest in the Abbey of Saint-Gilles.

As soon as he heard of the murder, the Pope ordered the legates to preach a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

against the Cathars, and wrote a letter to Philip Augustus, King of France, appealing for his intervention—or an intervention led by his son, Louis

Louis may refer to:

People

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

Other uses

* Louis (coin), a French coin

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

...

. This was not the first appeal, but some see the murder of the legate as a turning point in papal policy, which had hitherto refrained from the use of military force. Raymond of Toulouse was excommunicated, the second such instance, in 1209.

King Philip II of France refused to lead the crusade himself, and could not spare his son, Prince Louis VIII, to do so either—despite his victory against John, King of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Empi ...

, as there were still pressing issues with Flanders and the empire along with the threat of an Angevin revival. While King Philip II could not lead the crusade nor spare his son, he sanctioned the participation of some of his barons, notably Simon de Montfort and Bouchard de Marly. The twenty years of war against the Cathars and their allies in the Languedoc that followed were called the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

, derived from Albi

Albi (; ) is a commune in France, commune in southern France. It is the prefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department, on the river Tarn (river), Tarn, 85 km northeast of Toulouse. Its inhabitants are called ...

, the capital of the Albigensian district, the district corresponding to the present-day French department of Tarn.

This war pitted the nobles of France against those of the Languedoc. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree that permitted the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. This angered not only the lords of the south, but also the King Philip II of France, who was at least nominally the

This war pitted the nobles of France against those of the Languedoc. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree that permitted the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. This angered not only the lords of the south, but also the King Philip II of France, who was at least nominally the suzerain

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy and economic relations of another subordinate party or polity, but allows i ...

of the lords whose lands were now open to seizure. King Philip II wrote to Pope Innocent in strong terms to point this out—but Pope Innocent refused to change his decree. As the Languedoc was supposedly teeming with Cathars and Cathar sympathisers, this made the region a target for northern French noblemen looking to acquire new fiefs.

The first target for the barons of the North were the lands of the Trencavel, powerful lords of Carcassonne, Béziers, Albi, and the Razes. Little was done to form a regional coalition, and the crusading army was able to take Carcassonne, the Trencavel capital, incarcerating Raymond Roger Trencavel in his own citadel, where he died within three months. Champions of the Occitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

cause claimed that he was murdered. Simon de Montfort was granted the Trencavel lands by Pope Innocent, thus incurring the enmity of Peter II of Aragon

Peter II the Catholic (; ) (July 1178 – 12 September 1213) was the King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona from 1196 to 1213.

Background

Peter was born in Huesca, the son of Alfonso II of Aragon and Sancha of Castile, Queen of Aragon, Sancha ...

, who previously had been aloof from the conflict, even acting as a mediator at the time of the siege of Carcassonne.

The remainder of the first of the two Cathar wars now focused on Simon de Monfort's attempt to hold on to his gains through the winters. With a small force of confederates operating from the main winter camp at Fanjeaux, he was faced with the desertion of local lords who had sworn fealty to him out of necessity—and attempts to enlarge his newfound domain during the summer. His forces were then greatly augmented by reinforcements from northern France, Germany, and elsewhere.

De Montfort's summer campaigns recaptured losses sustained in winter months, in addition to attempts to widen the crusade's sphere of operation. Notably he was active in the Aveyron

Aveyron (; ) is a Departments of France, department in the Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Southern France. It was named after the river Aveyron (river), Aveyron. Its inhabitants are known as ''Aveyro ...

at St. Antonin and on the banks of the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

at Beaucaire. Simon de Monfort's greatest triumph was the victory against superior numbers at the Battle of Muret in 1213—a battle in which de Montfort's much smaller force, composed entirely of cavalry, decisively defeated the much-larger, by some estimates 5–10 times larger and combined-force allied armies of Raymond of Toulouse, his Occitan allies, and Peter II of Aragon

Peter II the Catholic (; ) (July 1178 – 12 September 1213) was the King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona from 1196 to 1213.

Background

Peter was born in Huesca, the son of Alfonso II of Aragon and Sancha of Castile, Queen of Aragon, Sancha ...

. The battle saw the death of Peter II, which effectively ended the ambitions and influence of the house of Aragon/Barcelona in the Languedoc.

In 1214, Philip II's victory at Bouvines near Lille ended the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214, dealt a death blow to the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

, and freed Philip II to concentrate more of his attentions to the Albigensian Crusade underway in the south of France. In addition, the victory at Bouvines was against an Anglo-German force that was attempting to undermine the power of the French crown. An Anglo-German victory would have been a serious setback to the crusade. Full French royal intervention in support of the crusade occurred in early 1226, when Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As a prince, he invaded Kingdom of England, England on 21 May 1216 and was Excommunication in the Catholic Church, excommunicated by a ...

led a substantial force into southeastern France.

Massacre

The crusader army came under the command, both spiritually and militarily, of the papal legateArnaud Amalric

Arnaud Amalric (; died 1225), also known as Arnaud Amaury, was a Cistercians, Cistercian abbot who played a prominent role in the Albigensian Crusade. It is purported that prior to the Massacre at Béziers, massacre of Béziers, Amalric, when aske ...

, Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

of Cîteaux. In the first significant engagement of the war, the town of Béziers

Béziers (; ) is a city in southern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Hérault Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region. Every August Béziers ho ...

was besieged on 22 July 1209. The Catholic inhabitants of the city were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but many refused and opted to stay and fight alongside the Cathars.

The townsmen spent much of 1209 fending off the crusaders. The Béziers army attempted a sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

but was quickly defeated, then pursued by the crusaders back through the gates and into the city. Arnaud Amalric

Arnaud Amalric (; died 1225), also known as Arnaud Amaury, was a Cistercians, Cistercian abbot who played a prominent role in the Albigensian Crusade. It is purported that prior to the Massacre at Béziers, massacre of Béziers, Amalric, when aske ...

, the Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

abbot-commander, wrote to Pope Innocent III, that during negotiations his soldiers had taken the initiative without waiting for orders. The doors of the church of St Mary Magdalene were broken down and the refugees dragged out and slaughtered. Reportedly, at least 7,000 men, women and children were killed there by Catholic forces, though some scholars dispute this number. Elsewhere in the town, many more thousands were mutilated and killed. Prisoners were blinded, dragged behind horses, and used for target practice. What remained of the city was razed by fire.

Arnaud Amalric wrote "Today your Holiness, twenty thousand heretics were put to the sword, regardless of rank, age, or sex." The permanent population of Béziers at that time was then between 10,000 and 14,500, but local refugees seeking shelter within the city walls could conceivably have increased the number to 20,000, though scholars dispute the figure as figurative.

According to a report thirty years later by a non-witness, Arnaud Amalric is supposed to have been asked how to tell Cathars from Catholics. His alleged reply, according to Caesarius of Heisterbach, a fellow Cistercian, was —"Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own".

After the success of his siege of Carcassonne, which followed the massacre at Béziers in 1209, Simon de Montfort was designated as leader of the Crusader army. Prominent opponents of the Crusaders were Raymond Roger Trencavel, viscount of Carcassonne, and his feudal overlord Peter II of Aragon

Peter II the Catholic (; ) (July 1178 – 12 September 1213) was the King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona from 1196 to 1213.

Background

Peter was born in Huesca, the son of Alfonso II of Aragon and Sancha of Castile, Queen of Aragon, Sancha ...

, who held fiefdoms and had a number of vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s in the region. Peter died fighting against the crusade on 12 September 1213 at the Battle of Muret. Simon de Montfort was killed on 25 June 1218 after maintaining a siege of Toulouse for nine months.

Treaty and persecution

The official war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France dispossessed the House of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs, and the house of the Trencavels of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. In spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished, and Catholic forces would continue to pursue Cathars.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the

The official war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France dispossessed the House of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs, and the house of the Trencavels of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. In spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished, and Catholic forces would continue to pursue Cathars.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the Fourth Council of the Lateran

The Fourth Council of the Lateran or Lateran IV was convoked by Pope Innocent III in April 1213 and opened at the Lateran Palace in Rome on 11 November 1215. Due to the great length of time between the council's convocation and its meeting, m ...

under Pope Innocent III. Part of the agenda was combating the Cathar heresy.

The Inquisition was established in 1233 to uproot the remaining Cathars. Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it succeeded in crushing Catharism as a popular movement, driving its remaining adherents underground. Cathars who refused to recant or relapsed were hanged, or burnt at the stake.

On Friday 13 May 1239, in Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, 183 men and women convicted of Catharism were burned at the stake on the orders of the Dominican inquisitor and former Cathar Perfect . Mount Guimar, in northeastern France, had already been denounced as a place of heresy in a letter of the Bishop of Liège

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Liège Province, province of Liège, Belgium. The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east o ...

to Pope Lucius II in 1144.

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged by the troops of the seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne. On 16 March 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, wherein over 200 Cathar Perfects were burnt in an enormous pyre at the ("field of the burned") near the foot of the castle. The Church, at the 1235 Council of Narbonne, decreed lesser chastisements against laymen suspected of sympathy with Cathars.

Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (, , , ) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenanc ...

(see below).

Hunted by the Inquisition and deserted by the nobles of their districts, the Cathars became more and more scattered fugitives, meeting surreptitiously in forests and mountain wilds. Later insurrections broke out under the leadership of Roger-Bernard II, Count of Foix, Aimery III of Narbonne, and Bernard Délicieux, a Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

friar later prosecuted for his adherence to another heretical movement, that of the Fraticelli, Spiritual Franciscans at the beginning of the 14th century. By this time, the Inquisition had grown very powerful. Consequently, many presumed to be Cathars were summoned to appear before it.

Precise indications of this are found in the registers of the Inquisitors Bernard de Caux, Bernard of Caux, Jean de St Pierre, Geoffroy d'Ablis, and others. The ''perfects'', it was said, only rarely recanted, and hundreds were burnt. Repentant laity, lay believers were punished, but their lives were spared as long as they did not relapse. Having recanted, they were obliged to sew yellow crosses onto their outdoor clothing and to live apart from other Catholics, at least for a time.

Annihilation

After several decades of harassment and re-proselytising, and, perhaps even more important, the systematic destruction of their religious texts, the sect was exhausted and could find no more adepts. In April 1310, the leader of a Cathar revival in the Pyrenees, Pyrenean foothills, Peire Autier, was captured and executed inToulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

. After 1330, the records of the Inquisition contain very few proceedings against Cathars. In the autumn of 1321, the last known Cathar ''perfect'' in the Languedoc, Guillaume Bélibaste, was executed.

From the mid-12th century onwards, Italian Catharism came under increasing pressure from the Pope and the Inquisition, "spelling the beginning of the end." Other movements, such as the Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

and the pantheistic Brethren of the Free Spirit, which suffered persecution in the same area, survived in remote areas and in small numbers through the 14th and 15th centuries. The Waldensian movement continues today. Waldensian ideas influenced other proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant sects, such as the Hussites, Lollards, and the Moravian Church.

Genocide

Later history