Carthago on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

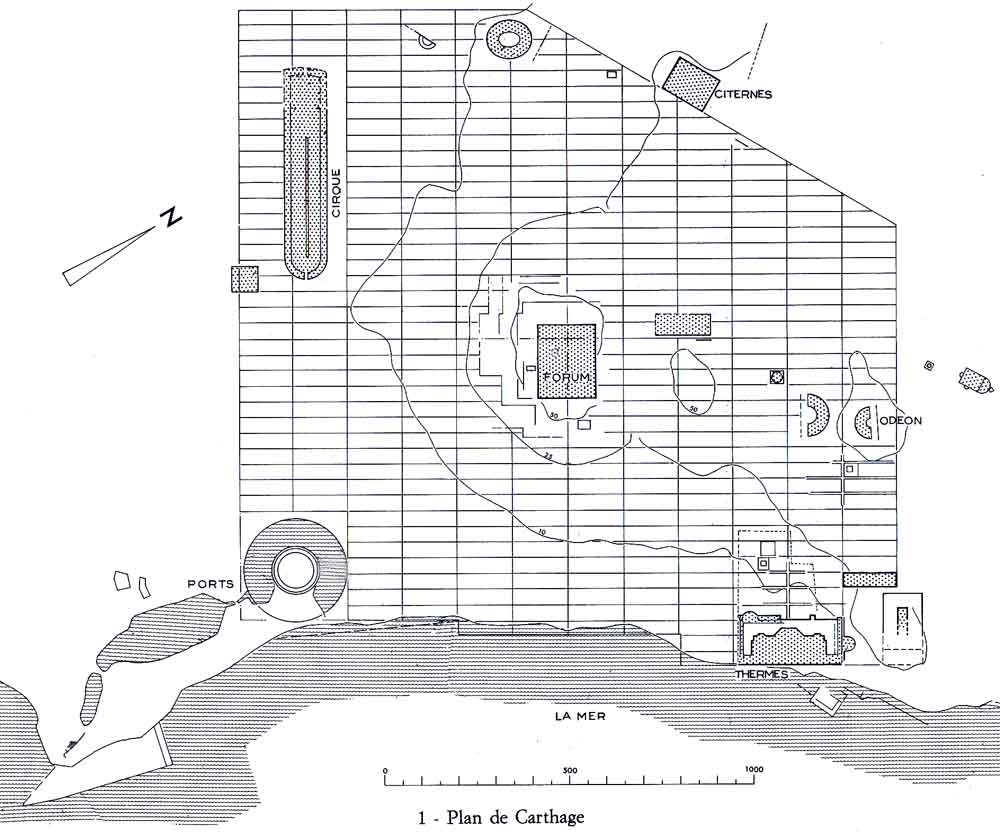

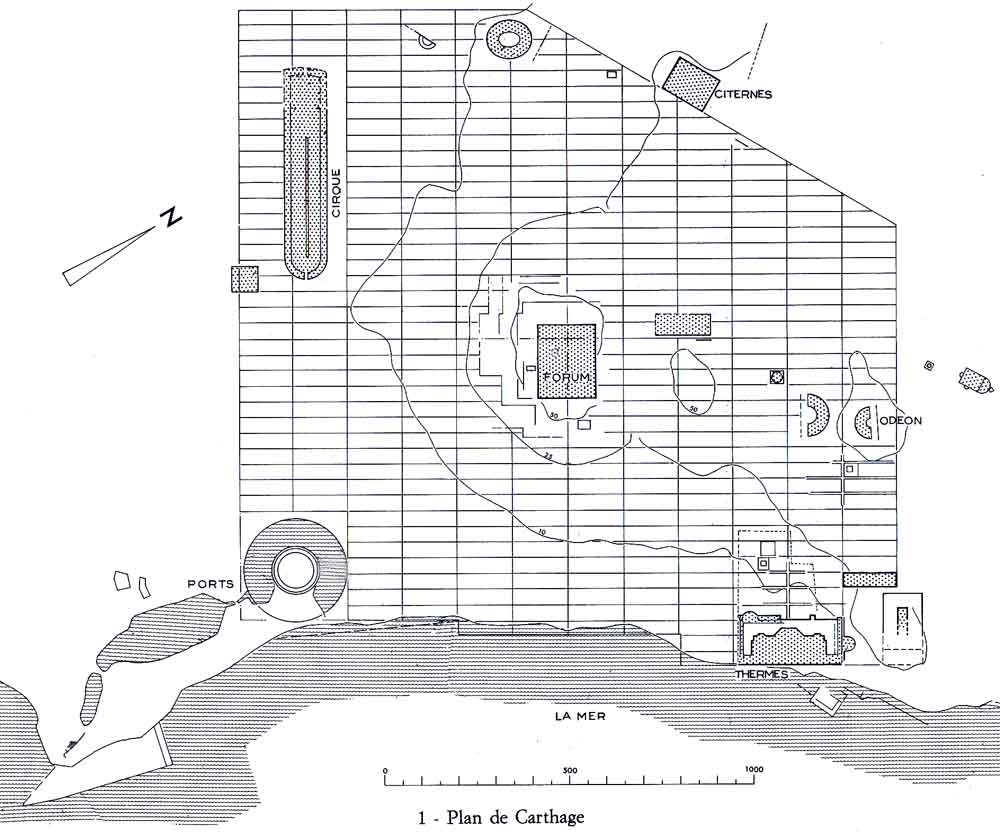

Roman Carthage was an important city in

Roman Carthage was an important city in

p. 27

/ref> It was the center of the Roman province of

The Vandals under

The Vandals under

The Odeon Hill has its name due to a misidentification of the building which was thought to be the Odeon, known to exist from

The Odeon Hill has its name due to a misidentification of the building which was thought to be the Odeon, known to exist from

Only traces of substructures of the Odeon remain, barely cleared at the beginning of the 20th century. It was rediscovered by who lead the excavations between 1900 and 1901. The Odeon was mentioned by the Christian theologist Tertullian and is where the Roman Emperor of African origin Septimus Severus shall have awarded the prize for the winner of the literary competition. The Odeon, which is considered to be the largest Roman Odeon, lies adjacent to the southern theatre and occupies three city blocks. It had a seating capacity of about 20,000 spectators and it was not assumed to be an Odeon were it not for the inscription ODEVM discovered in a cistern under the stage. In comparison, the second largest Roman Odeon in Athens had a seating capacity of 5,000.

Excavations took place again between 1994-2000 by researchers from the School of Architecture of the

Only traces of substructures of the Odeon remain, barely cleared at the beginning of the 20th century. It was rediscovered by who lead the excavations between 1900 and 1901. The Odeon was mentioned by the Christian theologist Tertullian and is where the Roman Emperor of African origin Septimus Severus shall have awarded the prize for the winner of the literary competition. The Odeon, which is considered to be the largest Roman Odeon, lies adjacent to the southern theatre and occupies three city blocks. It had a seating capacity of about 20,000 spectators and it was not assumed to be an Odeon were it not for the inscription ODEVM discovered in a cistern under the stage. In comparison, the second largest Roman Odeon in Athens had a seating capacity of 5,000.

Excavations took place again between 1994-2000 by researchers from the School of Architecture of the

The relics of the villas are in a mediocre state, except for those of the villa of the aviary. The main interest of the district consists in the vision of a neighbourhood of the ''Colonia Iulia Carthago'', organised in insulae or small islands of 35 meters by 141 meters.

The second-century district has orthogonal streets, "successive tiers crammed into the sides of the hill"; the upper tier is located in the ground, the lower tier opens onto the street above the lower tier. The flats were located on the upper floor, with the shops occupying the ground floor at street level.

The villa is the main feature of the park, due to the quality of the restoration carried out in the 1960s. The name of the villa comes from the

The relics of the villas are in a mediocre state, except for those of the villa of the aviary. The main interest of the district consists in the vision of a neighbourhood of the ''Colonia Iulia Carthago'', organised in insulae or small islands of 35 meters by 141 meters.

The second-century district has orthogonal streets, "successive tiers crammed into the sides of the hill"; the upper tier is located in the ground, the lower tier opens onto the street above the lower tier. The flats were located on the upper floor, with the shops occupying the ground floor at street level.

The villa is the main feature of the park, due to the quality of the restoration carried out in the 1960s. The name of the villa comes from the

The Circus of Carthage was modelled on the

The Circus of Carthage was modelled on the

The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History

'. Pan Macmillan. p. 402

Carthage Romaine, 146 avant Jésus-Christ — 698 après Jésus-Christ

', Paris. * Ernest Babelon,

', Paris (1896). * S. Raven (2002), ''Rome in Africa'', 3rd ed. {{Authority control

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, located in modern-day Tunisia. Approximately 100 years after the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of the same name (Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

'' Carthāgō'') was built on the same land by the Romans in the period from 49 to 44 BC. By the 3rd century, Carthage had developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, with a population of several hundred thousand.Likely the fourth city in terms of population during the imperial period, following Rome, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, in the 4th century also surpassed by Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

; also of comparable size were Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

and Pergamum

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; ), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Aeolis. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river ...

. Stanley D. Brunn, Maureen Hays-Mitchell, Donald J. Zeigler (eds.), ''Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development'', Rowman & Littlefield, 2012p. 27

/ref> It was the center of the Roman province of

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, which was a major breadbasket

The breadbasket of a country or of a region is an area which, because of the richness of the soil and/or advantageous climate, produces large quantities of wheat or other grain. Rice bowl is a similar term used to refer to Southeast Asia; Calif ...

of the empire. Carthage briefly became the capital of a usurper, Domitius Alexander

Lucius Domitius Alexander (died 310), probably born in Phrygia, was vicarius of Africa when Emperor Maxentius ordered him to send his son as hostage to Rome. Alexander refused and proclaimed himself emperor in 308.

The most detailed if somewhat ...

, in 308–311. Conquered by the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

in 439, Carthage served as the capital of the Vandal Kingdom

The Vandal Kingdom () or Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans () was a confederation of Vandals and Alans, which was a barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom established under Gaiseric, a Vandals, Vandalic warlord. It ruled parts of North Africa and th ...

for a century. Re-conquered by the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

in 533–534, it continued to serve as an Eastern Roman regional center, as the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa

The Praetorian Prefecture of Africa () was an administrative division of the Byzantine Empire in the Maghreb. With its seat at Carthage, it was established after the reconquest of northwestern Africa from the Vandals in 533–534 by the Byzantine ...

(after 590 the Exarchate of Africa

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in 591 and survived until t ...

).

The city was sacked and destroyed by Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

Arab forces after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire. A fortress on the site was garrisoned by Muslim forces until the Hafsid

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, w ...

period, when it was captured by Crusaders during the Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see an ...

. After the withdrawal of the Crusaders, the Hafsids decided to destroy the fortress to prevent any future use by a hostile power. Roman Carthage was used as a source of building materials for Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( , ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by the Umayyads around 670, in the period of Caliph Mu'awiya (reigned 661� ...

and Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

in the 8th century.

History

Foundation

After the Roman conquest of Carthage, its nearby rival Utica, a Roman ally, was made capital of the region and for a while replaced Carthage as the leading centre of Punic trade and leadership. It had the advantageous position of being situated on the outlet of theMedjerda River

The Medjerda River (), the classical antiquity, classical Bagradas, is a river in North Africa flowing from northeast Algeria through Tunisia before emptying into the Gulf of Tunis and Lake of Tunis. With a length of , it is the longest river of ...

, Tunisia's only river that flowed all year long. However, grain cultivation in the Tunisian mountains caused large amounts of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension (chemistry), suspension with water. Silt usually ...

to erode into the river. This silt accumulated in the harbour until it became useless, and so Rome looked for a new harbour town.

By 122 BC, Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

had founded a short-lived Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

, called Colonia Junonia

Colonia Junonia (sometimes ''Iunonia'') refers to an Ancient Roman colony established in 122 BC under the direction of Gaius Gracchus.

History

It is significant as it was the first 'transmarine' Roman colony.E. T. Salmon, Roman Colonization Under ...

. The purpose was to obtain arable lands for impoverished farmers. The Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

abolished the colony some time later, to undermine Gracchus' power.

After this failed effort, Carthage was rebuilt by Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

in the period from 49 to 44 BC, with the official name ''Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago''. By the first century, it had grown to be the second-largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. The geographer Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

wrote that when the third Punic War began in 149 BC, the Carthaginians ruled 300 cities in Libya and 700,000 people lived in Carthage. Dexter Hoyos writes that it was physically impossible in any period of its history for that many people to live within its walls. According to Hoyos, the population of Roman Carthage and its surrounding territory would have been around 575,000 in AD 149. It was the centre of the Roman province of Africa

Africa was a Roman province on the northern coast of the continent of Africa. It was established in 146 BC, following the Roman Republic's conquest of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisi ...

, which was a major breadbasket of the empire. Among its major monuments was an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (American English, U.S. English: amphitheater) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ('), meani ...

.

The temple of Juno Caelestis, dedicated to the City Protector Goddess Juno Caelestis, was one of the biggest building monuments of Carthage, and became a holy site for pilgrims from all Northern Africa and Spain.McHugh, J. S. (2015). The Emperor Commodus: God and Gladiator. (n.p.): Pen & Sword Books.

Early Christianity

Carthage became a centre of early Christianity. In the first of a string of rather poorly reported councils at Carthage a few years later, 70 bishops attended.Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

later broke with the mainstream that was increasingly represented in the West by the primacy of the Bishop of Rome

Papal primacy, also known as the primacy of the bishop of Rome, is an ecclesiological doctrine in the Catholic Church concerning the respect and authority that is due to the pope from other bishops and their episcopal sees. While the doctrin ...

, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, against which Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

spent much time and parchment arguing. At the Council of Carthage (397)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Early centers of Christianity#Carthage, Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, as ...

, the biblical canon for the western Church was confirmed. The Christians at Carthage conducted persecutions against the pagans, during which the pagan temples, including the Temple of Juno Caelesti, were destroyed.

The great fire of the second century, which swept through the capital of the governor of the province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

, made it possible to develop a hilly area of the city as part of an important urban planning project. A vast district of luxurious dwellings, including the "Villa de la volière", was built on this occasion. A circular monument, which was excavated during the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

campaign, called "rotonde sur podium carré", is sometimes dated to the Christian period and identified by some researchers as a mausoleum. A huge inscription to Aesculapius was found nearby, which suggests that the Punic temple of Eshmun

Eshmun (or Eshmoun, less accurately Esmun or Esmoun; '; ''Yasumunu'') was a Phoenician god of healing and the tutelary god of Sidon. His name, which means "eighth," may reference his status as the eighth son of the god Sydyk.

History

Eshm ...

was located on this site. Texts indicate that the Romans built the temple to the corresponding deity of their pantheon on the same site. The last fundamental element of the building program is a large leisure area, with a theatre dating from the second century and an odeon built in the third century. According to Victor de Vita, the whole area was destroyed by the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

. However, a remaining population lived there and a settlement persisted in the ruins.

Vandal period

The Vandals under

The Vandals under Gaiseric

Gaiseric ( – 25 January 477), also known as Geiseric or Genseric (; reconstructed Vandalic: ) was king of the Vandals and Alans from 428 to 477. He ruled over a kingdom and played a key role in the decline of the Western Roman Empire during ...

landed at the Roman province of Africa

Africa was a Roman province on the northern coast of the continent of Africa. It was established in 146 BC, following the Roman Republic's conquest of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisi ...

in 429, either at the request of Bonifacius

Bonifatius (or Bonifacius; also known as Count Boniface or Comes Bonifacius; died 432) was a Roman general and governor of the diocese of Africa. He campaigned against the Visigoths in Gaul and the Vandals in North Africa. An ally of Galla Plac ...

, a Roman general and the governor of the Diocese of Africa

The Diocese of Africa () was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, incorporating the provinces of North Africa, except Mauretania Tingitana. Its seat was at Carthage, and it was subordinate to the Praetorian prefecture of Italy.

The diocese in ...

, or as migrants in search of safety. They subsequently fought against the Roman forces there and by 435 had defeated the Roman forces in Africa and established the Vandal Kingdom

The Vandal Kingdom () or Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans () was a confederation of Vandals and Alans, which was a barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom established under Gaiseric, a Vandals, Vandalic warlord. It ruled parts of North Africa and th ...

. As an Arian

Arianism (, ) is a Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius (). It is considered he ...

, Gaiseric was considered a heretic by the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Christians, but a promise of religious toleration might have caused the city's population to accept him.

The 5th-century Roman bishop Victor Vitensis

Victor Vitensis (or Victor of Vita; born circa 430) was an African bishop of the Province of Byzacena (called Vitensis from his See of Vita). His importance rests on his ''Historia persecutionis Africanae Provinciae, temporibus Genserici et Hunir ...

mentions in ''Historia Persecutionis Africanae Provincia'' that the Vandals destroyed parts of Carthage, including various buildings and churches. Once in power, the ecclesiastical authorities were persecuted, the locals were aggressively taxed, and naval raids were routinely launched on Romans in the Mediterranean.

Byzantine period

After two failed attempts byMajorian

Majorian (; 7 August 461) was Western Roman emperor from 457 to 461. A prominent commander in the Late Roman army, Western military, Majorian deposed Avitus in 457 with the aid of his ally Ricimer at the Battle of Placentia (456), Battle of Place ...

and Basiliscus

Basiliscus (; died 476/477) was Eastern Roman emperor from 9 January 475 to August 476. He became in 464, under his brother-in-law, Emperor Leo I (457–474). Basiliscus commanded the army for an invasion of the Vandal Kingdom in 468, which ...

to recapture the city in the 5th century, the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire, using the deposition of Gaiseric's grandson Hilderic

Hilderic (460s – 533) was the penultimate king of the Vandals and Alans in North Africa in Late Antiquity (523–530). Although dead by the time the Vandal Kingdom was overthrown in 534, he nevertheless played a key role in that event.

Life ...

by his cousin Gelimer

Gelimer (original form possibly Geilamir, 480–553), was a Germanic king who ruled the Vandal Kingdom in antique North Africa from 530 to 534. He became ruler on 15 June 530 after deposing his first cousin twice removed, Hilderic, who had a ...

as a "casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one bou ...

", finally subdued the Vandals in the Vandalic War

The Vandalic War (533–534) was a conflict fought in North Africa between the forces of the Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire) and the Germanic Vandal Kingdom. It was the first war of Emperor Justinian I's , wherein the ...

of 533–534, the Roman general Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

, accompanied by his wife Antonina, made his formal entry into Carthage in October 533. Thereafter, for the next 165 years, the city was the capital of Byzantine North Africa

Byzantine rule in North Africa spanned around 175 years. It began in the years 533/534 with the reconquest of territory formerly belonging to the Western Roman Empire by the Byzantine Empire, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire under Justinian I and ...

, first organised as the praetorian prefecture of Africa

The Praetorian Prefecture of Africa () was an administrative division of the Byzantine Empire in the Maghreb. With its seat at Carthage, it was established after the reconquest of northwestern Africa from the Vandals in 533–534 by the Byzantine ...

, which later became the Exarchate of Africa

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in 591 and survived until t ...

during the emperor Maurice's reign. Along with the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna (; ), also known as the Exarchate of Italy, was an administrative district of the Byzantine Empire comprising, between the 6th and 8th centuries, the territories under the jurisdiction of the exarch of Italy (''exarchus ...

, these two regions were the western bulwarks of the Byzantine Empire, all that remained of its power in the West. In the early seventh century Heraclius the Elder

Heraclius the Elder (; died 610) was a Byzantine Roman general and the father of Byzantine Roman emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641). Heraclius the Elder distinguished himself in the war against the Sassanid Persians in the 580s. As a subordinate ...

, the Exarch

An exarch (;

from Ancient Greek ἔξαρχος ''exarchos'') was the holder of any of various historical offices, some of them being political or military and others being ecclesiastical.

In the late Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire, ...

of Africa, rebelled against the Byzantine emperor Phocas

Phocas (; ; 5475 October 610) was Eastern Roman emperor from 602 to 610. Initially a middle-ranking officer in the East Roman army, Roman army, Phocas rose to prominence as a spokesman for dissatisfied soldiers in their disputes with the cour ...

, whereupon his son Heraclius

Heraclius (; 11 February 641) was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

Heraclius's reign was ...

succeeded to the imperial throne.

Islamic conquest

The Exarchate of Africa first faced Muslim expansion fromEgypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in 647, but without lasting effect. A more protracted campaign lasted from 670 to 683 but ended in a Muslim defeat in the battle of Vescera

The Battle of Vescera (modern Biskra in Algeria) was fought in 682 or 683 between the Romano-Berbers of King Kusaila and their Byzantine allies from the Exarchate of Carthage against an Umayyad Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi (the founder of Ka ...

. Captured by the Muslims in 695, it was recaptured by the Byzantines in 697, but was finally conquered in 698 by the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

forces of Hassan ibn al-Nu'man

Hassan ibn al-Nu'man al-Ghassani () was an Arab general of the Umayyad Caliphate who led the final Muslim conquest of Ifriqiya, firmly establishing Islamic rule in the region. Appointed by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Abd al-Malik (), Hassan la ...

. Fearing that the Eastern Roman Empire might reconquer it, the Umayyads decided to destroy Roman Carthage in a scorched earth policy

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

and establish their centre of government further inland at Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

. The city walls were torn down, the water supply cut off, the agricultural land ravaged and its harbours made unusable. The destruction of the Roman Carthage and the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to Roman rule in the region, which had largely been in place since the 2nd century BC.

It is visible from archaeological evidence that the town of Carthage continued to be occupied, particularly the neighbourhood of Bjordi Djedid. The Baths of Antoninus

The Baths of Antoninus or Baths of Carthage, located in Carthage, Tunisia, are the largest set of Roman thermae built on the African continent and one of three largest built in the Roman Empire. They are the largest outside mainland Italy. The ...

continued to function in the Arab period and the historian Al-Bakri

Abū ʿUbayd ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb ibn ʿAmr al-Bakrī (), or simply al-Bakrī (c. 1040–1094) was an Arab Andalusian historian and a geographer of the Muslim West.

Life

Al-Bakri was born in Huelva, the ...

stated that they were still in good condition. They also had production centres nearby. It is difficult to determine whether the continued habitation of some other buildings belonged to Late Byzantine or Early Arab period. The Bir Ftouha church might have continued to remain in use though it is not clear when it became uninhabited. Constantine the African

Constantine the African, (; died before 1098/1099, Monte Cassino) was a physician who lived in the 11th century. The first part of his life was spent in Ifriqiya and the rest in Italy. He first arrived in Italy in the coastal town of Salerno, h ...

was born in Carthage.

The fortress of Carthage continued to be used by the Muslims until the Hafsid era and was captured in 1270 by Christian forces during the Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see an ...

. After the withdrawal of the Crusaders, Muhammad I al-Mustansir

Muhammad I al-Mustansir (; ) was the second Sultan of Ifriqiya of the Hafsid dynasty and the first to claim the title of Khalif. Al-Mustansir concluded a peace agreement to end the Eighth Crusade launched by Louis IX of France in 1270. Muhamm ...

decided to completely destroy it to prevent a repetition.

Rediscovery

The ruins of Carthage were rediscovered at the end of the 19th century. The Odeon was excavated in 1900–1901, and the amphitheatre was excavated in 1904.Amphitheatre

Odeon Hill

Odeon Hill, located to the north-east of the archaeological site of Carthage, is the site of numerous Roman ruins, including the theatre, the odeon, and the park of the Roman villas. The park includes the villa of the aviary, the best preserved Roman villa of the site of Carthage. The House of the Horses contains a mosaic of more than fifty circus horses, bordered by hunting scenes.Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

, but what tuned out to be a theatre. Odeon hill and the park of the Roman villas are located to the east of the Roman colony of Carthage, and to the north of the park of the Baths of Antoninus

The Baths of Antoninus or Baths of Carthage, located in Carthage, Tunisia, are the largest set of Roman thermae built on the African continent and one of three largest built in the Roman Empire. They are the largest outside mainland Italy. The ...

. On its outskirts is now located the area of the presidential palace in the south, while in the north the Mâlik ibn Anas mosque has been built.

Theatre

Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

mentions in his introduction to the ''Florides'' the richness of the decoration, the splendour of the marbles of the cavea, the parquet floor of the proscenium

A proscenium (, ) is the virtual vertical plane of space in a theatre, usually surrounded on the top and sides by a physical proscenium arch (whether or not truly "arched") and on the bottom by the stage floor itself, which serves as the frame ...

and the haughty beauty of the pillars. There was a colonnade of marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

and porphyry on the frons scænae, numerous statues and quality epigraphic ornaments. The theatre extends over an area equivalent of about four blocks and dates probably to the times of Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

. By size it is the second largest Roman theatre in Africa, only the one in Utica is larger.

Fragments of inscriptions found in the theatre refer to repairs made in the fourth century.

The theatre is a mixture of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Roman theatre: the tiers are supported by a system of vaults, but take advantage of the slope of the hill. The cavea

The ''cavea'' (Latin language, Latin for "enclosure") are the seating sections of Theatre of ancient Greece, Greek and Roman theatre (structure), Roman theatres and Roman amphitheatre, amphitheatres. In Roman theatres, the ''cavea'' is tradition ...

consisted of sections with tiers separated by stairs. The orchestra, with its more comfortable movable seats, was intended for VIP spectators. The pulpitum was a wall separating the orchestra from the stage, while the frons scænae formed the backdrop to the building. The odeon was entirely built, as it did not take advantage of the topography.

There are very few Roman remains of the stands in the present building. The theatre was renovated and since 1964 it is the site of the International Festival of Carthage. The semicircular walls also date from the early 20th century when it was used for costume production.

Odeon

Only traces of substructures of the Odeon remain, barely cleared at the beginning of the 20th century. It was rediscovered by who lead the excavations between 1900 and 1901. The Odeon was mentioned by the Christian theologist Tertullian and is where the Roman Emperor of African origin Septimus Severus shall have awarded the prize for the winner of the literary competition. The Odeon, which is considered to be the largest Roman Odeon, lies adjacent to the southern theatre and occupies three city blocks. It had a seating capacity of about 20,000 spectators and it was not assumed to be an Odeon were it not for the inscription ODEVM discovered in a cistern under the stage. In comparison, the second largest Roman Odeon in Athens had a seating capacity of 5,000.

Excavations took place again between 1994-2000 by researchers from the School of Architecture of the

Only traces of substructures of the Odeon remain, barely cleared at the beginning of the 20th century. It was rediscovered by who lead the excavations between 1900 and 1901. The Odeon was mentioned by the Christian theologist Tertullian and is where the Roman Emperor of African origin Septimus Severus shall have awarded the prize for the winner of the literary competition. The Odeon, which is considered to be the largest Roman Odeon, lies adjacent to the southern theatre and occupies three city blocks. It had a seating capacity of about 20,000 spectators and it was not assumed to be an Odeon were it not for the inscription ODEVM discovered in a cistern under the stage. In comparison, the second largest Roman Odeon in Athens had a seating capacity of 5,000.

Excavations took place again between 1994-2000 by researchers from the School of Architecture of the University of Waterloo

The University of Waterloo (UWaterloo, UW, or Waterloo) is a Public university, public research university located in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is on of land adjacent to uptown Waterloo and Waterloo Park. The university also op ...

in Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

and the Trinity University in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

. Although the site is located in a ''non aedificandi'' zone, it is now situated in the immediate vicinity of the Mâlik ibn Anas Mosque. The building, which stood against the theater and was built entirely above ground level, had semi-circular corridors for the circulation of visitors. Tertullian mentions the discovery of burial sites during the construction of the building. Timothy Barnes assumed it to have been built around 200 BC.

Roman villas

The relics of the villas are in a mediocre state, except for those of the villa of the aviary. The main interest of the district consists in the vision of a neighbourhood of the ''Colonia Iulia Carthago'', organised in insulae or small islands of 35 meters by 141 meters.

The second-century district has orthogonal streets, "successive tiers crammed into the sides of the hill"; the upper tier is located in the ground, the lower tier opens onto the street above the lower tier. The flats were located on the upper floor, with the shops occupying the ground floor at street level.

The villa is the main feature of the park, due to the quality of the restoration carried out in the 1960s. The name of the villa comes from the

The relics of the villas are in a mediocre state, except for those of the villa of the aviary. The main interest of the district consists in the vision of a neighbourhood of the ''Colonia Iulia Carthago'', organised in insulae or small islands of 35 meters by 141 meters.

The second-century district has orthogonal streets, "successive tiers crammed into the sides of the hill"; the upper tier is located in the ground, the lower tier opens onto the street above the lower tier. The flats were located on the upper floor, with the shops occupying the ground floor at street level.

The villa is the main feature of the park, due to the quality of the restoration carried out in the 1960s. The name of the villa comes from the mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

of the aviary, marked by the presence of birds among the foliage

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, f ...

, which occupies the garden, in the centre of the ''viridarium'', the heart of a square courtyard framed by a portico decorated with pink marble pillars.

To the southwest is a terrace that opens onto the street. To the west, a vaulted gallery also serves as a relief from the pressure of the ground, while the building's atrium is located to the east. To the north are all the prestige rooms, the ceremonial flats, the ''laraire'' and the vestibule.

Upstairs were the baths and shops. On the upper floor were the private flats of the owners, with shops under the terraced portico. Below the cryptoporticus

In Ancient Roman architecture

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural styl ...

was a weatherproof promenade.

Baths of Antoninus

The Baths of Antoninus or Baths of Carthage are the largest set of Romanthermae

In ancient Rome, (from Greek , "hot") and (from Greek ) were facilities for bathing. usually refers to the large Roman Empire, imperial public bath, bath complexes, while were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed i ...

built on the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and one of three largest built in the Roman Empire. They are the largest outside mainland Italy. The baths are also the only remaining Thermae of Carthage that dates back to the Roman Empire's era. The baths were built during the reign of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (; ; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held var ...

. The baths continued to function in the Arab period: the historian Al-Bakri

Abū ʿUbayd ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb ibn ʿAmr al-Bakrī (), or simply al-Bakrī (c. 1040–1094) was an Arab Andalusian historian and a geographer of the Muslim West.

Life

Al-Bakri was born in Huelva, the ...

stated that they were still in good condition.

The baths are at the South-East of the archaeological site, near the presidential Carthage Palace

Carthage Palace () is the presidential palace of Tunisia, and the official residence and seat of the President of Tunisia. It is located along the Mediterranean Sea at the current city of Carthage, near the archaeological site of the ancient c ...

. The archaeological excavations started during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and concluded by the creation of an archaeological park for the monument. It is also one of the most important landmarks of Tunisia.

Circus

The Circus of Carthage was modelled on the

The Circus of Carthage was modelled on the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian language, Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot racing, chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine Hill, Avent ...

in Rome. Measuring more than 470 m in length and 30 m in width, it could house up to 45,000 spectators, roughly one third of the Circus Maximus, and was used for chariot racing

Chariot racing (, ''harmatodromía''; ) was one of the most popular Ancient Greece, ancient Greek, Roman Empire, Roman, and Byzantine Empire, Byzantine sports. In Greece, chariot racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games from ...

.

The building appears to have been constructed sometime around 238 AD, and was used for several years before its official dedication.

Remains from the Circus Maximus, specifically the marble "spina" (a dividing barrier) were used in the Circus of Carthage, as well as the Circus of Maxentius and the city of Vienne located in France.

See also

* Bardo National Museum *Baths of Antoninus

The Baths of Antoninus or Baths of Carthage, located in Carthage, Tunisia, are the largest set of Roman thermae built on the African continent and one of three largest built in the Roman Empire. They are the largest outside mainland Italy. The ...

* Carthage National Museum

Carthage National Museum () is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthag ...

* Carthage Paleo-Christian Museum

The Carthage Paleo-Christian Museum is an archaeological museum of Paleochristian artifacts, located in Carthage, Tunisia. Built on an excavation site, it lies above the former Carthaginian basilica.

History

The Danish consul, Christia ...

* Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

* History of Carthage

The city of Carthage was founded in the 9th century BC on the coast of Northwest Africa, in what is now Tunisia, as one of a number of Phoenician settlements in the western Mediterranean created to facilitate trade from the city of Tyre on ...

* Mosaic of the Horses of Carthage

References

;Sources * * * Heather, Peter (2004).The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History

'. Pan Macmillan. p. 402

Further reading

*Auguste Audollent

Auguste Audollent (14 July 1864 – 7 April 1943) was a French historian, archaeologist and Latin epigrapher, specialist of ancient Rome, in particular the magical inscriptions ('' tabellæ defixionum''). His main thesis was devoted to ''Roman C ...

(1901), Carthage Romaine, 146 avant Jésus-Christ — 698 après Jésus-Christ

', Paris. * Ernest Babelon,

', Paris (1896). * S. Raven (2002), ''Rome in Africa'', 3rd ed. {{Authority control

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

Roman towns and cities in Tunisia

Populated places of the Byzantine Empire

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

7th-century disestablishments in the Exarchate of Africa

7th-century disestablishments in Africa

Destroyed populated places

Carthage