Candide (protagonist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

( , ) is a French

Voltaire actively rejected Leibnizian optimism after the natural disaster, convinced that if this were the best possible world, it should surely be better than it is.Mason (1992), p. 4 In both ''Candide'' and ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), Voltaire attacks this optimist belief, sarcastically describing the catastrophe as one of the most horrible disasters "in the best of all possible worlds".Wade (1959b), p. 93 Immediately after the earthquake, unreliable rumours circulated around Europe, sometimes overestimating the severity of the event. Ira Wade, a noted expert on Voltaire and ''Candide'', has analyzed which sources Voltaire might have referenced, speculating that Voltaire's primary source was the 1755 work by Ange Goudar.Wade (1959b), pp. 88, 93

Apart from such events, contemporaneous stereotypes of the German personality may have been a source of inspiration for the text, as they were for , a 1669 satirical picaresque novel written by

Voltaire actively rejected Leibnizian optimism after the natural disaster, convinced that if this were the best possible world, it should surely be better than it is.Mason (1992), p. 4 In both ''Candide'' and ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), Voltaire attacks this optimist belief, sarcastically describing the catastrophe as one of the most horrible disasters "in the best of all possible worlds".Wade (1959b), p. 93 Immediately after the earthquake, unreliable rumours circulated around Europe, sometimes overestimating the severity of the event. Ira Wade, a noted expert on Voltaire and ''Candide'', has analyzed which sources Voltaire might have referenced, speculating that Voltaire's primary source was the 1755 work by Ange Goudar.Wade (1959b), pp. 88, 93

Apart from such events, contemporaneous stereotypes of the German personality may have been a source of inspiration for the text, as they were for , a 1669 satirical picaresque novel written by

By the time of the Lisbon earthquake, Voltaire was already a well-established author. ''Candide'' became part of his large, diverse body of philosophical, political, and artistic works expressing these views.Means (2006), pp. 1–3Gopnik (2005) It became a model for the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels called the '' contes philosophiques''. This genre included previous works of his such as ''

By the time of the Lisbon earthquake, Voltaire was already a well-established author. ''Candide'' became part of his large, diverse body of philosophical, political, and artistic works expressing these views.Means (2006), pp. 1–3Gopnik (2005) It became a model for the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels called the '' contes philosophiques''. This genre included previous works of his such as ''

At a

At a

In 1760, one year after Voltaire published ''Candide'', a sequel was published with the name .Astbury (2005), p. 503 This work is attributed both to Thorel de Campigneulles, a writer unknown today, and Henri Joseph Du Laurens, who is suspected of having habitually plagiarised Voltaire. The story continues in this sequel with Candide having new adventures in the

In 1760, one year after Voltaire published ''Candide'', a sequel was published with the name .Astbury (2005), p. 503 This work is attributed both to Thorel de Campigneulles, a writer unknown today, and Henri Joseph Du Laurens, who is suspected of having habitually plagiarised Voltaire. The story continues in this sequel with Candide having new adventures in the

''Candide''

at the

''Candide''

(; original version) with 2200+ English annotations at Tailored Texts

traduit de l'allemand. De Mr. le Docteur Ralph, 1759. ** , Par Mr. de Voltaire. Edition revue, corrigée & augmentée par L'Auteur

vol. 1vol. 2

aux delices, 1761–1763.

''La Vallière Manuscript'' at http://gallica.bnf.fr

bibliography of illustrated editions, list of available electronic editions and more useful information from Trier University Library

Voltaire's ''Candide''

a public wiki dedicated to ''Candide''

issued by the Voltaire Society of America

Podcast lecture on ''Candide''

from Dr Martin Evans at

satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

written by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, a philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, first published in 1759. The novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The Optimist'' (1762); and ''Candide: Optimism'' (1947). A young man, Candide, lives a sheltered life in an Edenic paradise

In religion and folklore, paradise is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical, eschatological, or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human ...

, being indoctrinated with Leibnizian optimism by his mentor, Professor Pangloss. This lifestyle is abruptly ended, followed by Candide's slow and painful disillusionment as he witnesses and experiences great hardships in the world. Voltaire concludes ''Candide'' with, if not rejecting Leibnizian optimism outright, advocating a deeply practical precept, "we must cultivate our garden", in lieu of the Leibnizian mantra of Pangloss, "all is for the best" in the "best of all possible worlds

The phrase "the best of all possible worlds" (; ) was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work '' Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal'' ...

".

''Candide'' is characterized by its tone as well as its erratic, fantastical, and fast-moving plot. A picaresque novel

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrup ...

with a story akin to a serious bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a bildungsroman () is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth and change of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age). The term comes from the German words ('formation' or 'edu ...

, it parodies many adventure and romance clichés, in a tone that is bitter and matter-of-fact. The events discussed are often based on historical happenings.Mason (1992), p. 10 As philosophers of Voltaire's day contended with the problem of evil

The problem of evil is the philosophical question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an Omnipotence, omnipotent, Omnibenevolence, omnibenevolent, and Omniscience, omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ...

, so does Candide, albeit more directly and humorously. Voltaire ridicules religion, theologians, governments, armies, philosophies, and philosophers. Through ''Candide'', he assaults Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

and his optimism.Aldridge (1975), p. 260

''Candide'' has enjoyed both great success and great scandal. Immediately after its secretive publication, the book was widely banned on the grounds of blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

and sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

. However, the novel has inspired many later authors and artists; today, ''Candide'' is considered Voltaire's ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

'' and is often listed as part of the Western canon

The Western canon is the embodiment of High culture, high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western culture, Western world, such works having achieved the status of classics.

Recent ...

. It is among the most frequently taught works of French literature

French literature () generally speaking, is literature written in the French language, particularly by French people, French citizens; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of Franc ...

. Martin Seymour-Smith

Martin Roger Seymour-Smith (24 April 1928 – 1 July 1998) was a British poet, literary critic, and biographer.

Biography

Seymour-Smith was born in London and educated at Highgate School and St Edmund Hall, Oxford, where he was editor of ''Isis ...

listed ''Candide'' as one of the 100 most influential books ever written.

Historical and literary background

Several historical events inspired Voltaire to write ''Candide'', most notably the publication of Leibniz's "Monadology

The ''Monadology'' (, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substances, or '' monads''.

Text

During his last stay in V ...

", the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, All Saints' Day, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In ...

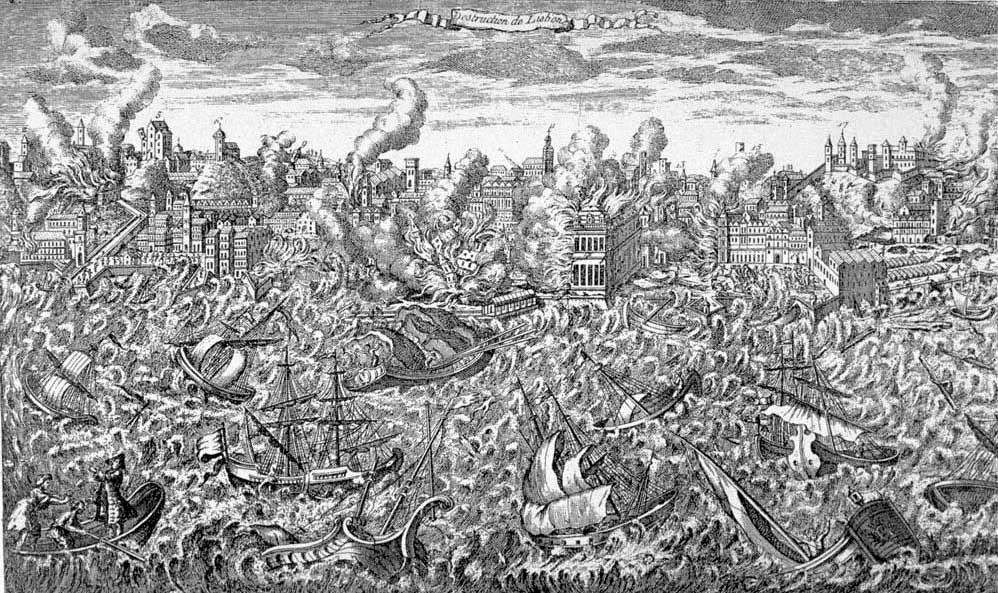

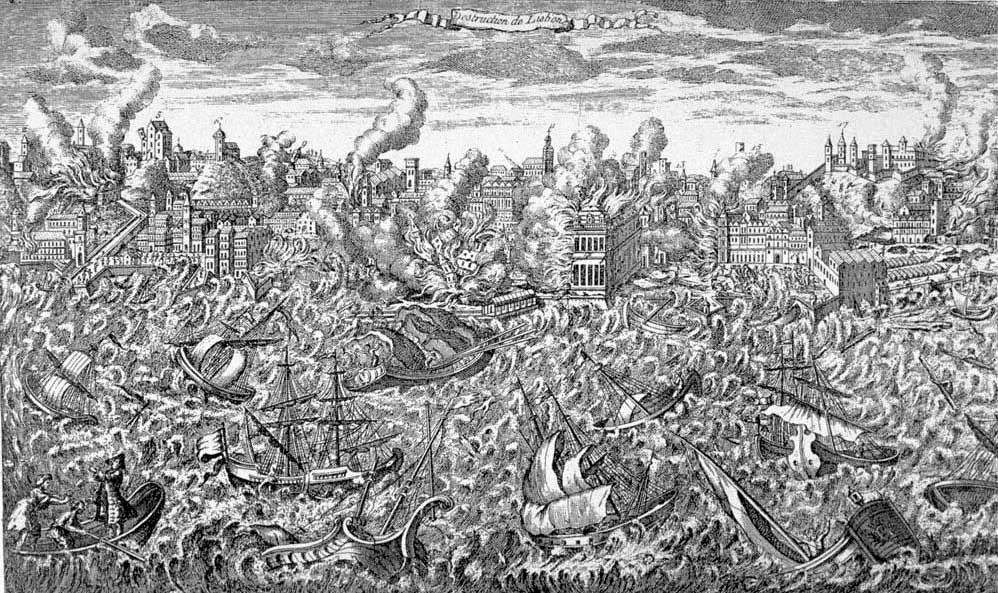

. Both of the latter catastrophes are frequently referred to in ''Candide''.Wade (1959b), p. 88 The earthquake, tsunami, and resulting fires of All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the Church, whether they are know ...

had a strong influence on theologians of the day and on Voltaire, who was himself disillusioned by them. It had an especially large effect on the contemporary doctrine of optimism, a philosophical system founded on the theodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

, which insisted on God's benevolence in spite of such events. This concept is often put in the form, "all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds" (). Philosophers had trouble fitting the horrors of this earthquake into their optimistic world view

A worldview (also world-view) or is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. However, when two parties view the s ...

.Radner & Radner (1998), pp. 669–686

Voltaire actively rejected Leibnizian optimism after the natural disaster, convinced that if this were the best possible world, it should surely be better than it is.Mason (1992), p. 4 In both ''Candide'' and ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), Voltaire attacks this optimist belief, sarcastically describing the catastrophe as one of the most horrible disasters "in the best of all possible worlds".Wade (1959b), p. 93 Immediately after the earthquake, unreliable rumours circulated around Europe, sometimes overestimating the severity of the event. Ira Wade, a noted expert on Voltaire and ''Candide'', has analyzed which sources Voltaire might have referenced, speculating that Voltaire's primary source was the 1755 work by Ange Goudar.Wade (1959b), pp. 88, 93

Apart from such events, contemporaneous stereotypes of the German personality may have been a source of inspiration for the text, as they were for , a 1669 satirical picaresque novel written by

Voltaire actively rejected Leibnizian optimism after the natural disaster, convinced that if this were the best possible world, it should surely be better than it is.Mason (1992), p. 4 In both ''Candide'' and ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), Voltaire attacks this optimist belief, sarcastically describing the catastrophe as one of the most horrible disasters "in the best of all possible worlds".Wade (1959b), p. 93 Immediately after the earthquake, unreliable rumours circulated around Europe, sometimes overestimating the severity of the event. Ira Wade, a noted expert on Voltaire and ''Candide'', has analyzed which sources Voltaire might have referenced, speculating that Voltaire's primary source was the 1755 work by Ange Goudar.Wade (1959b), pp. 88, 93

Apart from such events, contemporaneous stereotypes of the German personality may have been a source of inspiration for the text, as they were for , a 1669 satirical picaresque novel written by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen

Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1621/22 – 17 August 1676) was one of the most notable German authors of the 17th century. He is best known for his 1669 picaresque novel ''Simplicius Simplicissimus'' () and the accompanying ''Simplic ...

and inspired by the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. The protagonist of this novel, supposed to embody stereotypically German characteristics, is quite similar to the protagonist of ''Candide''. These stereotypes, according to Voltaire biographer Alfred Owen Aldridge, include "extreme credulousness or sentimental simplicity", two of Candide's and Simplicius's defining qualities. Aldridge writes, "Since Voltaire admitted familiarity with fifteenth-century German authors who used a bold and buffoonish style, it is quite possible that he knew as well."

A satirical and parodic precursor of ''Candide'', Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

's ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', originally titled ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'', is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clerg ...

'' (1726) is one of ''Candide''s closest literary relatives. This satire tells the story of "a gullible ingenue", Gulliver, who (like Candide) travels to several "remote nations" and is hardened by the many misfortunes which befall him. As evidenced by similarities between the two books, Voltaire probably drew upon ''Gulliver's Travels'' for inspiration while writing ''Candide''. Other probable sources of inspiration for ''Candide'' are (1699) by François Fénelon

François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon, PSS (), more commonly known as François Fénelon (6 August 1651 – 7 January 1715), was a French Catholic archbishop, theologian, poet and writer. Today, he is remembered mostly as the author of ' ...

and (1753) by Louis-Charles Fougeret de Monbron. ''Candide''s parody of the bildungsroman is probably based on , which includes the prototypical parody of the tutor on whom Pangloss may have been partly based. Likewise, Monbron's protagonist undergoes a disillusioning series of travels similar to those of Candide.

Creation

By the time of the Lisbon earthquake, Voltaire was already a well-established author. ''Candide'' became part of his large, diverse body of philosophical, political, and artistic works expressing these views.Means (2006), pp. 1–3Gopnik (2005) It became a model for the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels called the '' contes philosophiques''. This genre included previous works of his such as ''

By the time of the Lisbon earthquake, Voltaire was already a well-established author. ''Candide'' became part of his large, diverse body of philosophical, political, and artistic works expressing these views.Means (2006), pp. 1–3Gopnik (2005) It became a model for the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels called the '' contes philosophiques''. This genre included previous works of his such as ''Zadig

''Zadig; or, The Book of Fate'' (; 1747) is a novella and work of philosophical fiction by the Enlightenment writer Voltaire. It tells the story of Zadig, a Zoroastrian philosopher in ancient Babylonia. The story of Zadig is a fictional story. ...

'' and '' Micromegas''.

It is unknown exactly when Voltaire wrote ''Candide.'' Scholars estimate that it was primarily composed in late 1758 and begun as early as 1757. Voltaire is believed to have written a portion of it while living at Les Délices

Les Délices ("The Delights") was from 1755 to 1760 the home of the French philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778) in Geneva, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe ...

near Geneva and also while visiting Charles Théodore, the Elector-Palatinate, at Schwetzingen

Schwetzingen (; ) is a German town in northwest Baden-Württemberg, around southwest of Heidelberg and southeast of Mannheim.

Schwetzingen is one of the five biggest cities of the Rhein-Neckar-Kreis district and a medium-sized centre between ...

for three weeks in the summer of 1758. Despite solid evidence for these claims, a popular legend persists that he wrote ''Candide'' in three days. This idea is probably based on a misreading of the 1885 work by Lucien Pereyand Gaston Maugras.

There is only one extant manuscript of ''Candide'' that was written before the work's 1759 publication, discovered in 1956 by Wade and since named the ''La Vallière Manuscript''. It is believed to have been sent, chapter by chapter, by Voltaire to the Duke and Duchess La Vallière in the autumn of 1758. The manuscript was sold to the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in the late eighteenth century, where it remained undiscovered for almost two hundred years.Rouillard (1962) The ''La Vallière Manuscript'', the most original and authentic of all surviving copies of ''Candide'', was probably dictated by Voltaire to his secretary, Jean-Louis Wagnière

Jean-Louis Wagnière (15 October 1739, Rueyres, Vaud, Switzerland7 April 1802, Ferney-Voltaire) was Voltaire's secretary from 1756 to 1778, when Voltaire died.

In Voltaire’s Service

Wagnière entered Voltaire’s service as his valet de cha ...

, then edited directly. In addition to this manuscript, there is believed to have been another, one copied by Wagnière for the Elector Charles-Théodore, who hosted Voltaire during the summer of 1758. The existence of this copy was first postulated by Norman L. Torrey in 1929. If it exists, it remains undiscovered.Wade (1956), pp. 3–4

Voltaire published ''Candide'' simultaneously in five countries no later than 15 January 1759, although the exact date is uncertain. Seventeen versions of ''Candide'' from 1759, in the original French, are known today, and there has been great controversy over which is the earliest. More versions were published in other languages: ''Candide'' was translated once into Italian and thrice into English that same year.Davidson (2005), pp. 52–53 The complicated science of calculating the relative publication dates of all of the versions of ''Candide'' is described at length in Wade's article "The First Edition of ''Candide'': A Problem of Identification". The publication process was extremely secretive, probably the "most clandestine work of the century", because of the book's obviously illicit and irreverent content. The greatest number of copies of ''Candide'' were published concurrently in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

by Cramer Cramer may refer to:

Businesses

* Cramer brothers, 18th century publishers

* Cramer Systems, a software company

* Cramer & Co., a former musical-related business in London

Other uses

* Cramer (surname), including a list of people and fictional ...

, in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

by Marc-Michel Rey, in London by Jean Nourse, and in Paris by Lambert.Wade (1959a), pp. 63–88

''Candide'' underwent one major revision after its initial publication, in addition to some minor ones. In 1761, a version of ''Candide'' was published that included, along with several minor changes, a major addition by Voltaire to the twenty-second chapter, a section that had been thought weak by the Duke of Vallière. The English title of this edition was ''Candide, or Optimism, Translated from the German of Dr. Ralph. With the additions found in the Doctor's pocket when he died at Minden

Minden () is a middle-sized town in the very north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, the largest town in population between Bielefeld and Hanover. It is the capital of the district () of Minden-Lübbecke, situated in the cultural region ...

, in the Year of Grace 1759.''Voltaire 759

__NOTOC__

Year 759 ( DCCLIX) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 759 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe ...

(1959) The last edition of ''Candide'' authorised by Voltaire was the one included in Cramer's 1775 edition of his complete works, known as , in reference to the border or frame around each page.

Voltaire strongly opposed the inclusion of illustrations

An illustration is a decoration, interpretation, or visual explanation of a text, concept, or process, designed for integration in print and digitally published media, such as posters, flyers, magazines, books, teaching materials, animations, vi ...

in his works, as he stated in a 1778 letter to the writer and publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke:

Despite this protest, two sets of illustrations for ''Candide'' were produced by the French artist Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune. The first version was done, at Moreau's own expense, in 1787 and included in Kehl's publication of that year, ''Oeuvres Complètes de Voltaire''.Bellhouse (2006), p. 756 Four images were drawn by Moreau for this edition and were engraved by Pierre-Charles Baquoy.Bellhouse (2006), p. 757 The second version, in 1803, consisted of seven drawings by Moreau which were transposed by multiple engravers.Bellhouse (2006), p. 769 The twentieth-century modern artist Paul Klee

Paul Klee (; 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented wi ...

stated that it was while reading ''Candide'' that he discovered his own artistic style. Klee illustrated the work, and his drawings were published in a 1920 version edited by Kurt Wolff.

List of characters

Main characters

* Candide: The title character. The illegitimate son of the sister of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh. In love with Cunégonde. *Cunégonde

Cunégonde is a fictional character in Voltaire's 1759 novel ''Candide''. She is the title character's aristocratic cousin and love interest.

At the beginning of the story, the protagonist Candide is chased away from his uncle's home after he is ...

: The daughter of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh. In love with Candide.

* Professor Pangloss: The royal educator of the court of the baron. Described as "the greatest philosopher of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

".

* The Old Woman: Cunégonde's maid while she is the mistress of Don Issachar and the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal. Flees with Candide and Cunégonde to the New World. Illegitimate daughter of Pope Urban X.

* Cacambo: Born from a Mestizo

( , ; fem. , literally 'mixed person') is a term primarily used to denote people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry in the former Spanish Empire. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturall ...

father and an Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

mother. Lived half his life in Spain and half in Latin America. Candide's valet while in America.

* Martin: Dutch amateur philosopher and Manichaean

Manichaeism (; in ; ) is an endangered former major world religion currently only practiced in China around Cao'an,R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''. SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 found ...

. Meets Candide in Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

, travels with him afterwards.

* The Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh: Brother of Cunégonde. Is seemingly killed by the Bulgarians, but becomes a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

in Paraguay. Disapproves of Candide and Cunégonde's marriage.

Secondary characters

* The baron and baroness of Thunder-ten-Tronckh: Father and mother of Cunégonde and the second baron. Both slain by the Bulgars. * The king of the Bulgars: Frederick II * Jacques theAnabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

: Dutch manufacturer who takes Candide in after his escape from the Prussian Army. Drowns in the port of Lisbon after saving a sailor's life.

* Don Issachar: Jewish banker in Portugal. Cunégonde becomes his mistress, shared with the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal. Killed by Candide.

* The Grand Inquisitor

Grand Inquisitor (, literally ''Inquisitor General'' or ''General Inquisitor'') was the highest-ranked official of the Inquisition. The title usually refers to the inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition, in charge of appeals and cases of aristoc ...

of Portugal: Sentences Candide and Pangloss at the ''auto-da-fé

An ''auto-da-fé'' ( ; from Portuguese language, Portuguese or Spanish language, Spanish (, meaning 'act of faith') was a ritualized or public penance carried out between the 15th and 19th centuries in condemnation of heresy, heretics, Aposta ...

''. Cunégonde is his mistress jointly with Don Issachar. Killed by Candide.

* Don Fernando d'Ibarra y Figueroa y Mascarenes y Lampourdos y Souza: Spanish governor of Buenos Aires. Wants Cunégonde as a mistress.

* The king of El Dorado

El Dorado () is a mythical city of gold supposedly located somewhere in South America. The king of this city was said to be so rich that he would cover himself from head to foot in gold dust – either daily or on certain ceremonial occasions � ...

, who helps Candide and Cacambo out of El Dorado, lets them pick gold from the grounds, and makes them rich.

* Mynheer Vanderdendur: Dutch ship captain/pirate and slave holder. Offers to take Candide from America to France for 30,000 gold coins, but then departs without him, stealing most of his riches. Dies after his ship sinks.

* The abbot of Périgord: Befriends Candide and Martin in the hopes of scamming them. Tries to have them arrested.

* The marchioness of Parolignac: Parisian wench who takes an elaborate title.

* The scholar: One of the guests of the "marchioness". Argues with Candide about art.

* Paquette: A chambermaid from Thunder-ten-Tronckh who gave Pangloss syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

after getting it herself from her Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

confessor. After the slaying by the Bulgars, works as a prostitute in Venice and becomes entangled with Friar Giroflée.

* Friar Giroflée: Theatine

The Theatines, officially named the Congregation of Clerics Regular (; abbreviated CR), is a Catholic order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men founded by Archbishop Gian Pietro Carafa on 14 September 1524.

Foundation

The order was f ...

friar. In love with the prostitute Paquette.

* Signor Pococurante: A Venetian noble. Candide and Martin visit his estate, where he discusses his disdain of most of the canon of great art.

* In an inn in Venice, Candide and Martin dine with six men who turn out to be deposed monarchs:

** Ahmed III

Ahmed III (, ''Aḥmed-i sālis''; was sultan of the Ottoman Empire and a son of sultan Mehmed IV (r. 1648–1687). His mother was Gülnuş Sultan, originally named Evmania Voria, who was an ethnic Greek. He was born at Hacıoğlu Pazarcık, ...

** Ivan VI of Russia

Ivan VI Antonovich (; – ), also known as Ioann Antonovich, was Emperor of Russia from October 1740 until he was overthrown by his cousin Elizabeth Petrovna in December 1741. He was only two months old when he was proclaimed emperor and his mo ...

** Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, ...

** Augustus III of Poland

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was List of Polish monarchs, King of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as List of rulers of Saxony, Elector of Saxony i ...

** Stanisław Leszczyński

Stanisław I Leszczyński (Stanisław Bogusław; 20 October 1677 – 23 February 1766), also Anglicized and Latinized as Stanislaus I, was twice King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and at various times Prince of Deux-Ponts, Duk ...

** Theodore of Corsica

Theodore I of Corsica (25 August 169411 December 1756), born Freiherr Theodor Stephan von Neuhoff, was a low-ranking German title of nobility, usually translated "Baron". was a German adventurer who was briefly Kingdom of Corsica, King of Corsica. ...

Synopsis

''Candide'' contains thirty episodic chapters, which may be grouped into two main schemes: one consists of two divisions, separated by the protagonist'shiatus

Hiatus may refer to:

* Hiatus (anatomy), a natural fissure in a structure

* Hiatus (stratigraphy), a discontinuity in the age of strata in stratigraphy

*''Hiatus'', a genus of picture-winged flies with sole member species '' Hiatus fulvipes''

* G ...

in El Dorado

El Dorado () is a mythical city of gold supposedly located somewhere in South America. The king of this city was said to be so rich that he would cover himself from head to foot in gold dust – either daily or on certain ceremonial occasions � ...

; the other consists of three parts, each defined by its geographical setting. By the former scheme, the first half of ''Candide'' constitutes the rising action and the last part the resolution. This view is supported by the strong theme of travel and quest, reminiscent of adventure and picaresque

The picaresque novel (Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt ...

novels, which tend to employ such a dramatic structure

Story structure or narrative structure is the recognizable or comprehensible way in which a narrative's different elements are unified, including in a particularly chosen order and sometimes specifically referring to the ordering of the plot: ...

.Williams (1997), pp. 26–27 By the latter scheme, the thirty chapters may be grouped into three parts each comprising ten chapters and defined by locale: I–X are set in Europe, XI–XX are set in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, and XXI–XXX are set in Europe and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.Beck (1999), p. 203 The plot summary that follows uses this second format and includes Voltaire's additions of 1761.

Chapters I–X

The tale of ''Candide'' begins in the castle of the Baron Thunder-ten-Tronckh inWestphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

, home to the Baron's daughter, Lady Cunégonde; his bastard

Bastard or The Bastard may refer to:

Parentage

* Illegitimate child, a child born to unmarried parents, in traditional Western family law

** Bastard, an archaic term used in English and Welsh bastardy laws, reformed in 1926

People

* "The Bastard" ...

nephew, Candide; a tutor, Pangloss; a chambermaid

A maid, housemaid, or maidservant is a female domestic worker. In the Victorian era, domestic service was the second-largest category of employment in England and Wales, after agricultural work. In developed Western nations, full-time maids a ...

, Paquette; and the rest of the Baron's family. The protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

, Candide, is romantically attracted to Cunégonde. He is a young man of "the most unaffected simplicity" (), whose face is "the true index of his mind" (). Dr. Pangloss, professor of "" (English: " metaphysico- theologo-cosmolonigology") and self-proclaimed optimist, teaches his pupils that they live in the "best of all possible worlds

The phrase "the best of all possible worlds" (; ) was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work '' Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal'' ...

" and that "all is for the best".

All is well in the castle until Cunégonde sees Pangloss sexually engaged with Paquette in some bushes. Encouraged by this show of affection, Cunégonde drops her handkerchief next to Candide, enticing him to kiss her. For this infraction, Candide is evicted from the castle, at which point he is captured by Bulgar (Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n) recruiters and coerced into military service, where he is flogged

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on a ...

, nearly executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, and forced to participate in a major battle between the Bulgars and the Avars (an allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

representing the Prussians and the French). Candide eventually escapes the army and makes his way to Holland where he is given aid by Jacques, an Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

, who strengthens Candide's optimism. Soon after, Candide finds his master Pangloss, now a beggar with syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

. Pangloss reveals he was infected with this disease by Paquette and shocks Candide by relating how Castle Thunder-ten-Tronckh was destroyed by Bulgars, that Cunégonde and her whole family were killed, and that Cunégonde was rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

d before her death. Pangloss is cured of his illness by Jacques, losing one eye and one ear in the process, and the three set sail to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

.

In Lisbon's harbor, they are overtaken by a vicious storm which destroys the boat. Jacques attempts to save a sailor, and in the process is thrown overboard. The sailor makes no move to help the drowning Jacques, and Candide is in a state of despair until Pangloss explains to him that Lisbon harbor was created in order for Jacques to drown. Only Pangloss, Candide, and the "brutish sailor" who let Jacques drownSmollett (2008), Ch. 4. ("") survive the wreck and reach Lisbon, which is promptly hit by an earthquake, tsunami, and fire that kill tens of thousands. The sailor leaves in order to loot the rubble while Candide, injured and begging for help, is lectured on the optimistic view of the situation by Pangloss.

The next day, Pangloss discusses his optimistic philosophy with a member of the Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in 15 ...

, and he and Candide are arrested for heresy, set to be tortured and killed in an "" set up to appease God and prevent another disaster. Candide is flogged and sees Pangloss hanged, but another earthquake intervenes and he escapes. He is approached by an old woman, who leads him to a house where Lady Cunégonde waits, alive. Candide is surprised: Pangloss had told him that Cunégonde had been raped and disemboweled. She had been, but Cunégonde points out that people survive such things. However, her rescuer sold her to a Jewish merchant, Don Issachar, who was then threatened by a corrupt Grand Inquisitor

Grand Inquisitor (, literally ''Inquisitor General'' or ''General Inquisitor'') was the highest-ranked official of the Inquisition. The title usually refers to the inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition, in charge of appeals and cases of aristoc ...

into sharing her (Don Issachar gets Cunégonde on Mondays, Wednesdays, and the sabbath day). Her owners arrive, find her with another man, and Candide kills them both. Candide and the two women flee the city, heading to the Americas. Along the way, Cunégonde falls into self-pity, complaining of all the misfortunes that have befallen her.

Chapters XI–XX

The old woman reciprocates by revealing her own tragic life: born the daughter of Pope Urban X and the Princess ofPalestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; , ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon ...

, she was kidnapped and enslaved by Barbary pirates

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

, witnessed violent civil wars in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

under the bloodthirsty king Moulay Ismaïl (during which her mother was drawn and quartered), suffered constant hunger, nearly died from a plague in Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

, and had a buttock cut off to feed starving Janissaries

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted du ...

during the Russian capture of Azov. After traversing all the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, she eventually became a servant of Don Issachar and met Cunégonde.

The trio arrives in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

, where Governor Don Fernando d'Ibarra y Figueroa y Mascarenes y Lampourdos y Souza asks to marry Cunégonde. Just then, an ''alcalde

''Alcalde'' (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and Administration (government), administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor (position), corregidor, the presiding officer o ...

'' (a Spanish magistrate) arrives, pursuing Candide for killing the Grand Inquisitor. Leaving the women behind, Candide flees to Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

with his practical and heretofore unmentioned manservant, Cacambo.

At a

At a border post

A border checkpoint is a location on an international border where travelers or goods are inspected and allowed (or denied) passage through. Authorization often is required to enter a country through its borders. Access-controlled borders of ...

on the way to Paraguay, Cacambo and Candide speak to the commandant

Commandant ( or ; ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ...

, who turns out to be Cunégonde's unnamed brother. He explains that after his family was slaughtered, the Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s' preparation for his burial revived him, and he has since joined the order. When Candide proclaims he intends to marry Cunégonde, her brother attacks him, and Candide runs him through with his rapier

A rapier () is a type of sword originally used in Spain (known as ' -) and Italy (known as '' spada da lato a striscia''). The name designates a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It wa ...

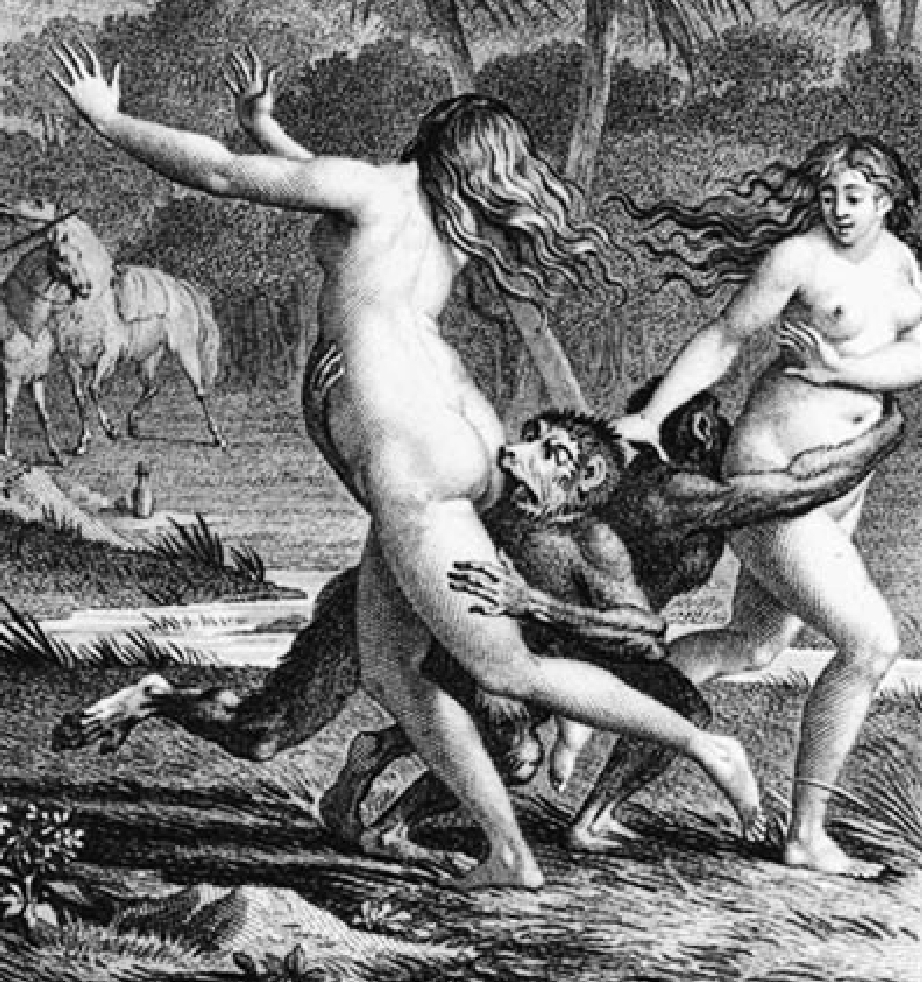

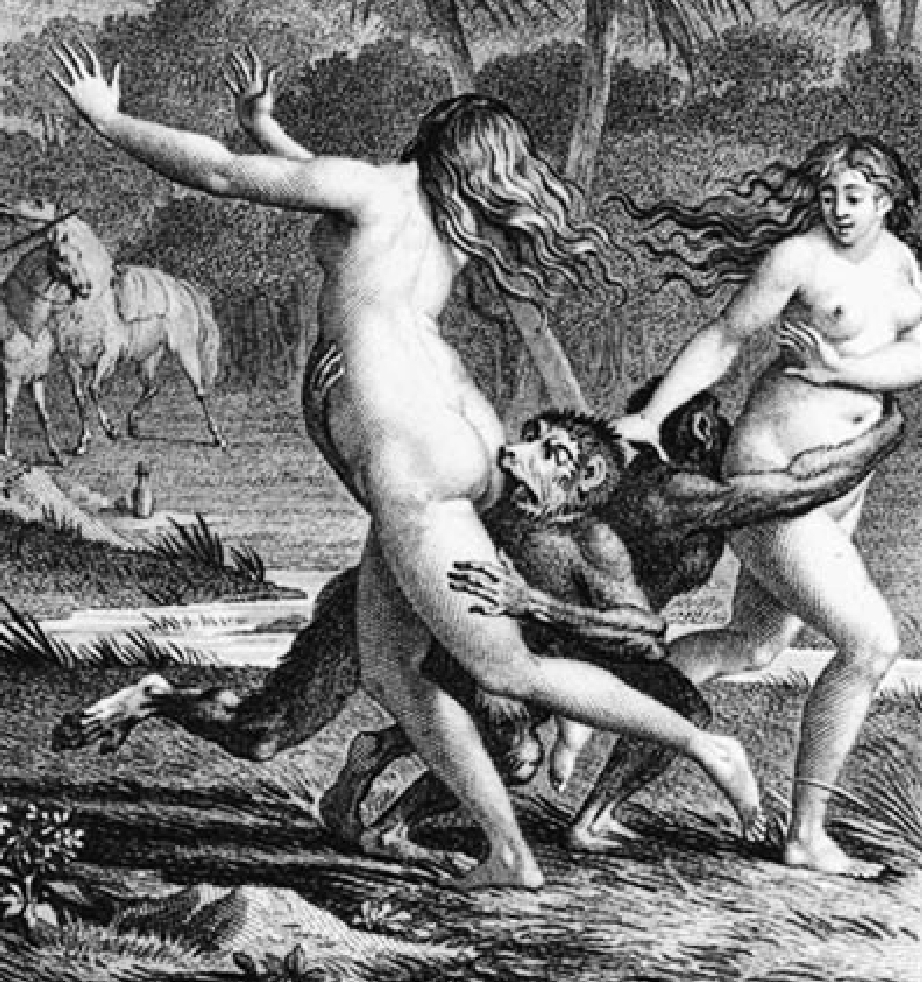

. After lamenting all the people (mainly priests) he has killed, he and Cacambo flee. In their flight, Candide and Cacambo come across two naked women being chased and bitten by a pair of monkeys. Candide, seeking to protect the women, shoots and kills the monkeys, but is informed by Cacambo that the monkeys and women were probably lovers.

Cacambo and Candide are captured by Oreillons, or Orejones; members of the Inca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

nobility who widened the lobes of their ears, and are depicted here as the fictional inhabitants of the area. Mistaking Candide for a Jesuit by his robes, the Oreillons prepare to cook Candide and Cacambo; however, Cacambo convinces the Oreillons that Candide killed a Jesuit to procure the robe. Cacambo and Candide are released and travel for a month on foot and then down a river by canoe, living on fruits and berries.

After a few more adventures, Candide and Cacambo wander into El Dorado

El Dorado () is a mythical city of gold supposedly located somewhere in South America. The king of this city was said to be so rich that he would cover himself from head to foot in gold dust – either daily or on certain ceremonial occasions � ...

, a geographically isolated utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

where the streets are covered with precious stones, there exist no priests, and all of the king's jokes are funny. Candide and Cacambo stay a month in El Dorado, but Candide is still in pain without Cunégonde, and expresses to the king his wish to leave. The king points out that this is a foolish idea, but generously helps them do so. The pair continue their journey, now accompanied by one hundred red pack sheep carrying provisions and incredible sums of money, which they slowly lose or have stolen over the next few adventures.

Candide and Cacambo eventually reach Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

where they split up: Cacambo travels to Buenos Aires to retrieve Lady Cunégonde, while Candide prepares to travel to Europe to await the two. Candide's remaining sheep are stolen, and Candide is fined heavily by a Dutch magistrate for petulance over the theft. Before leaving Suriname, Candide feels in need of companionship, so he interviews a number of local men who have been through various ill-fortunes and settles on a man named Martin.

Chapters XXI–XXX

This companion, Martin, is aManichaean

Manichaeism (; in ; ) is an endangered former major world religion currently only practiced in China around Cao'an,R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''. SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 found ...

scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

based on the real-life pessimist Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. He is best known for his '' Historical and Critical Dictionary'', whose publication began in 1697. Many of the more controversial ideas ...

, who was a chief opponent of Leibniz. For the remainder of the voyage, Martin and Candide argue about philosophy, Martin painting the entire world as occupied by fools. Candide, however, remains an optimist at heart, since it is all he knows. After a detour to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

and Paris, they arrive in England and see an admiral (based on Admiral Byng) being shot for not killing enough of the enemy. Martin explains that Britain finds it necessary to shoot an admiral from time to time "''pour encourager les autres''" (to encourage the others). Candide, horrified, arranges for them to leave Britain immediately. Upon their arrival in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Candide and Martin meet Paquette, the chambermaid who infected Pangloss with his syphilis. She is now a prostitute, and is spending her time with a Theatine

The Theatines, officially named the Congregation of Clerics Regular (; abbreviated CR), is a Catholic order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men founded by Archbishop Gian Pietro Carafa on 14 September 1524.

Foundation

The order was f ...

monk, Brother Giroflée. Although both appear happy on the surface, they reveal their despair: Paquette has led a miserable existence as a sexual object since she was forced to become a prostitute, and the monk detests the religious order in which he was indoctrinated. Candide gives two thousand piastre

The piastre or piaster () is any of a number of units of currency. The term originates from the Italian for "thin metal plate". The name was applied to Spanish and Hispanic American pieces of eight, or pesos, by Venetian traders in the Le ...

s to Paquette and one thousand to Brother Giroflée.

Candide and Martin visit the Lord Pococurante, a noble Venetian. That evening, Cacambo—now a slave—arrives and informs Candide that Cunégonde is in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. Prior to their departure, Candide and Martin dine with six strangers who had come for the Carnival of Venice

The Carnival of Venice (; ) is an annual festival held in Venice, Italy, famous throughout the world for its elaborate costumes and masks. The Carnival ends on Shrove Tuesday (''Martedì Grasso'' or Mardi Gras), which is the day before the star ...

. These strangers are revealed to be dethroned kings: the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III

Ahmed III (, ''Aḥmed-i sālis''; was sultan of the Ottoman Empire and a son of sultan Mehmed IV (r. 1648–1687). His mother was Gülnuş Sultan, originally named Evmania Voria, who was an ethnic Greek. He was born at Hacıoğlu Pazarcık, ...

, Emperor Ivan VI of Russia

Ivan VI Antonovich (; – ), also known as Ioann Antonovich, was Emperor of Russia from October 1740 until he was overthrown by his cousin Elizabeth Petrovna in December 1741. He was only two months old when he was proclaimed emperor and his mo ...

, Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, ...

(an unsuccessful pretender to the English throne), Augustus III of Poland

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was List of Polish monarchs, King of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as List of rulers of Saxony, Elector of Saxony i ...

(deprived, at the time of writing, of his reign in the Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony ( or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356 to 1806 initially centred on Wittenberg that came to include areas around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz. It was a ...

due to the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

), Stanisław Leszczyński

Stanisław I Leszczyński (Stanisław Bogusław; 20 October 1677 – 23 February 1766), also Anglicized and Latinized as Stanislaus I, was twice King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and at various times Prince of Deux-Ponts, Duk ...

, and Theodore of Corsica

Theodore I of Corsica (25 August 169411 December 1756), born Freiherr Theodor Stephan von Neuhoff, was a low-ranking German title of nobility, usually translated "Baron". was a German adventurer who was briefly Kingdom of Corsica, King of Corsica. ...

.

On the way to Constantinople, Cacambo reveals that Cunégonde—now horribly ugly—currently washes dishes on the banks of the Propontis

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

as a slave for a fugitive Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

n prince by the name of Rákóczi

The House of Rákóczi (older spelling Rákóczy) was a Hungarian nobility, Hungarian noble family in the Kingdom of Hungary between the 13th century and 18th century. Their name is also spelled ''Rákoci'' (in Slovakia), ''Rakoczi'' and ''Rako ...

. After arriving at the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

, they board a galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

where, to Candide's surprise, he finds Pangloss and Cunégonde's brother among the rowers. Candide buys their freedom and further passage at steep prices.Ayer (1986), pp. 143–145 They both relate how they survived, but despite the horrors he has been through, Pangloss's optimism remains unshaken: "I still hold to my original opinions, because, after all, I'm a philosopher, and it wouldn't be proper for me to recant, since Leibniz cannot be wrong, and since pre-established harmony is the most beautiful thing in the world, along with the plenum

Plenum may refer to:

* Plenum chamber, a chamber intended to contain air, gas, or liquid at positive pressure

* Plenism, or ''Horror vacui'' (physics) the concept that "nature abhors a vacuum"

* Plenum (meeting), a meeting of a deliberative assem ...

and subtle matter."Voltaire 759

__NOTOC__

Year 759 ( DCCLIX) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 759 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe ...

(1959), pp. 107–108

Candide, the baron, Pangloss, Martin, and Cacambo arrive at the banks of the Propontis, where they rejoin Cunégonde and the old woman. Cunégonde has indeed become hideously ugly, but Candide nevertheless buys their freedom and marries Cunégonde to spite her brother, who forbids Cunégonde from marrying anyone but a baron of the Empire (he is secretly sold back into slavery). Paquette and Brother Giroflée—having squandered their three thousand piastres—are reconciled with Candide on a small farm () which he just bought with the last of his finances.

One day, the protagonists seek out a dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from ) in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage is found particularly in Persi ...

known as a great philosopher of the land. Candide asks him why Man is made to suffer so, and what they all ought to do. The dervish responds by asking rhetorically why Candide is concerned about the existence of evil and good. The dervish describes human beings as mice on a ship sent by a king to Egypt; their comfort does not matter to the king. The dervish then slams his door on the group. Returning to their farm, Candide, Pangloss, and Martin meet a Turk whose philosophy is to devote his life only to simple work and not concern himself with external affairs. He and his four children cultivate a small area of land, and the work keeps them "free of three great evils: boredom, vice, and poverty."Voltaire 759

__NOTOC__

Year 759 ( DCCLIX) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 759 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe ...

(1959), p. 112,113 Candide, Pangloss, Martin, Cunégonde, Paquette, Cacambo, the old woman, and Brother Giroflée all set to work on this "commendable plan" () on their farm, each exercising his or her own talents. Candide ignores Pangloss's insistence that all turned out for the best by necessity, instead telling him "we must cultivate our garden" ().

Style

As Voltaire himself described it, the purpose of ''Candide'' was to "bring amusement to a small number of men of wit". The author achieves this goal by combining wit with a parody of the classic adventure-romance plot. Candide is confronted with horrible events described in painstaking detail so often that it becomes humorous. Literary theorist Frances K. Barasch described Voltaire's matter-of-fact narrative as treating topics such as mass death "as coolly as a weather report".Barasch (1985), p. 3 The fast-paced and improbable plot—in which characters narrowly escape death repeatedly, for instance—allows for compounding tragedies to befall the same characters over and over again.Starobinski (1976), p. 194 In the end, ''Candide'' is primarily, as described by Voltaire's biographer Ian Davidson, "short, light, rapid and humorous".Wade (1959b), p. 133 Behind the playful façade of ''Candide'' which has amused so many, there lies very harsh criticism of contemporary European civilization which angered many others. European governments such as France, Prussia, Portugal and England are each attacked ruthlessly by the author: the French and Prussians for the Seven Years' War, the Portuguese for theirInquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

, and the British for the execution of John Byng

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral John Byng (baptised 29 October 1704 – 14 March 1757) was a Royal Navy officer and politician who was court-martialled and executed by firing squad. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen, he participate ...

. Organised religion, too, is harshly treated in ''Candide''. For example, Voltaire mocks the Jesuit order

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 by ...

of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Aldridge provides a characteristic example of such anti-clerical passages for which the work was banned: while in Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

, Cacambo remarks, " he Jesuitsare masters of everything, and the people have no money at all …". Here, Voltaire suggests the Christian mission in Paraguay is taking advantage of the local population. Voltaire depicts the Jesuits holding the indigenous peoples as slaves while they claim to be helping them.

Satire

The main method of ''Candide''s satire is to contrast ironically great tragedy and comedy. The story does not invent or exaggerate evils of the world—it displays real ones starkly, allowing Voltaire to simplify subtle philosophies and cultural traditions, highlighting their flaws. Thus ''Candide'' derides optimism, for instance, with a deluge of horrible, historical (or at least plausible) events with no apparent redeeming qualities. A simple example of the satire of ''Candide'' is seen in the treatment of the historic event witnessed by Candide and Martin inPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

harbour. There, the duo spy an anonymous admiral, supposed to represent John Byng

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral John Byng (baptised 29 October 1704 – 14 March 1757) was a Royal Navy officer and politician who was court-martialled and executed by firing squad. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen, he participate ...

, being executed for failing to properly engage a French fleet. The admiral is blindfolded and shot on the deck of his own ship, merely "to encourage the others" (, an expression Voltaire is credited with originating). This depiction of military punishment trivializes Byng's death. The dry, pithy explanation "to encourage the others" thus satirises a serious historical event in characteristically Voltairian fashion. For its classic wit, this phrase has become one of the more often quoted from ''Candide''.Havens (1973), p. 843

Voltaire depicts the worst of the world and his pathetic hero's desperate effort to fit it into an optimistic outlook. Almost all of ''Candide'' is a discussion of various forms of evil: its characters rarely find even temporary respite. There is at least one notable exception: the episode of El Dorado

El Dorado () is a mythical city of gold supposedly located somewhere in South America. The king of this city was said to be so rich that he would cover himself from head to foot in gold dust – either daily or on certain ceremonial occasions � ...

, a fantastic village in which the inhabitants are simply rational, and their society is just and reasonable. The positivity of El Dorado may be contrasted with the pessimistic attitude of most of the book. Even in this case, the bliss of El Dorado is fleeting: Candide soon leaves the village to seek Cunégonde, whom he eventually marries only out of a sense of obligation.

Another element of the satire focuses on what William F. Bottiglia, author of many published works on ''Candide'', calls the "sentimental foibles of the age" and Voltaire's attack on them.Bottiglia (1968), pp. 89–92 Flaws in European culture are highlighted as ''Candide'' parodies adventure and romance clichés, mimicking the style of a picaresque novel

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrup ...

. A number of archetypal characters thus have recognisable manifestations in Voltaire's work: Candide is supposed to be the drifting rogue of low social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

, Cunégonde the sex interest, Pangloss the knowledgeable mentor, and Cacambo the skillful valet.Aldridge (1975), pp. 251–254 As the plot unfolds, readers find that Candide is no rogue, Cunégonde becomes ugly and Pangloss is a stubborn fool. The characters of ''Candide'' are unrealistic, two-dimensional, mechanical, and even marionette

A marionette ( ; ) is a puppet controlled from above using wires or strings depending on regional variations. A marionette's puppeteer is called a marionettist. Marionettes are operated with the puppeteer hidden or revealed to an audience by ...

-like; they are simplistic and stereotypical.Wade (1959b), pp. 303–305 As the initially naïve protagonist eventually comes to a mature conclusion—however noncommittal—the novella is a ''bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a bildungsroman () is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth and change of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age). The term comes from the German words ('formation' or 'edu ...

'', if not a very serious one.

Garden motif

Gardens are thought by many critics to play a critical symbolic role in ''Candide''. The first location commonly identified as a garden is the castle of the Baron, from which Candide and Cunégonde are evicted much in the same fashion asAdam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

are evicted from the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

in the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

. Cyclically, the main characters of ''Candide'' conclude the novel in a garden of their own making, one which might represent celestial paradise. The third most prominent "garden" is El Dorado

El Dorado () is a mythical city of gold supposedly located somewhere in South America. The king of this city was said to be so rich that he would cover himself from head to foot in gold dust – either daily or on certain ceremonial occasions � ...

, which may be a false Eden. Other possibly symbolic gardens include the Jesuit pavilion, the garden of Pococurante, Cacambo's garden, and the Turk's garden.Bottiglia (1951), pp. 727, 731

These gardens are probably references to the Garden of Eden, but it has also been proposed, by Bottiglia, for example, that the gardens refer also to the ''Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

'', and that Candide's conclusion to cultivate "his garden" symbolises Voltaire's great support for this endeavour. Candide and his companions, as they find themselves at the end of the novella, are in a very similar position to Voltaire's tightly knit philosophical circle which supported the : the main characters of ''Candide'' live in seclusion to "cultivate heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

garden", just as Voltaire suggested his colleagues leave society to write. In addition, there is evidence in the epistolary

Epistolary means "relating to an epistle or letter". It may refer to:

* Epistolary (), a Christian liturgical book containing set readings for church services from the New Testament Epistles

* Epistolary novel, a novel written as a series of lette ...

correspondence of Voltaire that he had elsewhere used the metaphor of gardening to describe writing the . Another interpretative possibility is that Candide cultivating "his garden" suggests his engaging in only necessary occupations, such as feeding oneself and fighting boredom. This is analogous to Voltaire's own view on gardening: he was himself a gardener at his estates in Les Délices

Les Délices ("The Delights") was from 1755 to 1760 the home of the French philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778) in Geneva, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe ...

and Ferney

Ferney-Voltaire () is a commune in the Ain department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of eastern France. It lies between the Jura Mountains and the Swiss border; it forms part of the metropolitan area of Geneva. It is named for Voltaire, ...

, and he often wrote in his correspondence that gardening was an important pastime of his own, it being an extraordinarily effective way to keep busy.Scherr (1993)

Philosophy

Optimism

''Candide'' satirises various philosophical and religious theories that Voltaire had previously criticised. Primary among these is Leibnizian optimism (sometimes called ''Panglossianism'' after its fictional proponent), which Voltaire ridicules with descriptions of seemingly endless calamity.Davidson (2005), p. 54 Voltaire demonstrates a variety of irredeemable evils in the world, leading many critics to contend that Voltaire's treatment of evil—specifically the theological problem of its existence—is the focus of the work. Heavily referenced in the text are the Lisbon earthquake, disease, and the sinking of ships in storms. Also, war, thievery, and murder—evils of human design—are explored as extensively in ''Candide'' as are environmental ills. Bottiglia notes Voltaire is "comprehensive" in his enumeration of the world's evils. He is unrelenting in attacking Leibnizian optimism. Fundamental to Voltaire's attack is Candide's tutor Pangloss, a self-proclaimed follower of Leibniz and a teacher of his doctrine. Ridicule of Pangloss's theories thus ridicules Leibniz himself, and Pangloss's reasoning is silly at best. For example, Pangloss's first teachings of the narrative absurdly mix up cause and effect: Following such flawed reasoning even more doggedly than Candide, Pangloss defends optimism. Whatever their horrendous fortune, Pangloss reiterates "all is for the best" ("") and proceeds to "justify" the evil event's occurrence. A characteristic example of suchtheodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

is found in Pangloss's explanation of why it is good that syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

exists:

Candide, the impressionable and incompetent student of Pangloss, often tries to justify evil, fails, invokes his mentor and eventually despairs. It is by these failures that Candide is painfully cured (as Voltaire would see it) of his optimism.

This critique of Voltaire's seems to be directed almost exclusively at Leibnizian optimism. ''Candide'' does not ridicule Voltaire's contemporary Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

, a later optimist of slightly different convictions. ''Candide'' does not discuss Pope's optimistic principle that "all is right", but Leibniz's that states, "this is the best of all possible worlds". However subtle the difference between the two, ''Candide'' is unambiguous as to which is its subject. Some critics conjecture that Voltaire meant to spare Pope this ridicule out of respect, although Voltaire's ''Poème'' may have been written as a more direct response to Pope's theories. This work is similar to ''Candide'' in subject matter, but very different from it in style: the ''Poème'' embodies a more serious philosophical argument than ''Candide''.Aldridge (1975), pp. 251–254, 361

Conclusion