Cabbage tree (New Zealand) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cordyline australis'', commonly known as the cabbage tree, or by its

File:Cordyline australis (III).jpg, alt=Close-up of three flowers growing from a thin stem, plus some unopened buds, Magnified view of flowers of ''C. australis''.

File:Cabbage Tree Flowers.jpg, alt=Large branched flower spikes coming out of the top of a tree. Spikes are covered in hundreds of tiny flowers, The

In

In

''Cordyline australis'' was collected in 1769 by

''Cordyline australis'' was collected in 1769 by

Many plants and animals are associated with ''C. australis'' in healthy ecosystems. The most common

Many plants and animals are associated with ''C. australis'' in healthy ecosystems. The most common

Cases of sick and dying trees of ''C. australis'' were first reported in the northern part of the North Island in 1987. The syndrome, eventually called sudden decline, soon reached epidemic proportions in Northland and Auckland. Affected trees usually suffer total defoliation within 2 to 12 months. The foliage turns yellow, and the oldest leaves wither and fall off. Growth of leaves ceases, and eventually all the leaves fall, leaving dead branches, often with the dried-out flowering panicles still attached. At the same time, the bark on the trunk becomes loose and detaches easily. The greatest number of dead trees (18 to 26 percent) was recorded around Auckland.

For some years, the cause of the disease was unknown, and hypotheses included tree ageing, fungi, viruses, and environmental factors such as an increase in ultra-violet light. Another hypothesis was that a genetic problem may have been induced in Northland and Auckland by the thousands of cabbage trees brought into the area from elsewhere and planted in gardens and parks. The Lands and Survey Department had a native plant nursery at

Cases of sick and dying trees of ''C. australis'' were first reported in the northern part of the North Island in 1987. The syndrome, eventually called sudden decline, soon reached epidemic proportions in Northland and Auckland. Affected trees usually suffer total defoliation within 2 to 12 months. The foliage turns yellow, and the oldest leaves wither and fall off. Growth of leaves ceases, and eventually all the leaves fall, leaving dead branches, often with the dried-out flowering panicles still attached. At the same time, the bark on the trunk becomes loose and detaches easily. The greatest number of dead trees (18 to 26 percent) was recorded around Auckland.

For some years, the cause of the disease was unknown, and hypotheses included tree ageing, fungi, viruses, and environmental factors such as an increase in ultra-violet light. Another hypothesis was that a genetic problem may have been induced in Northland and Auckland by the thousands of cabbage trees brought into the area from elsewhere and planted in gardens and parks. The Lands and Survey Department had a native plant nursery at

In traditional times, Māori had a rich knowledge of the cabbage tree, including spiritual, ecological and many practical aspects of its use. While much of that specialised knowledge was lost after the European settlement of New Zealand, the use of the tree as food and medicine has persisted, and the use of its fibres for weaving is becoming more common.

In traditional times, Māori had a rich knowledge of the cabbage tree, including spiritual, ecological and many practical aspects of its use. While much of that specialised knowledge was lost after the European settlement of New Zealand, the use of the tree as food and medicine has persisted, and the use of its fibres for weaving is becoming more common.

The 2006 Banks Memorial Lecture: Cultural uses of New Zealand native plants

''New Zealand Garden Journal'' 1:10–16. Retrieved 2010-04-04. *

Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

name of ''tī'' or ''tī kōuka'', is a widely branched monocot

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae ''sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are flowering plants whose seeds contain only one Embryo#Plant embryos, embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. A monocot taxon has been in use for several decades, but ...

tree endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to New Zealand.

It grows up to tall with a stout trunk and sword-like leaves, which are clustered at the tips of the branches and can be up to long. With its tall, straight trunk and dense, rounded heads, it is a characteristic feature of the New Zealand landscape. It is common over a wide latitudinal range from the far north of the North Island

The North Island ( , 'the fish of Māui', historically New Ulster) is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but less populous South Island by Cook Strait. With an area of , it is the List ...

to the south of the South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

. It grows in a broad range of habitats

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

. The largest known tree, growing at Pākawau, Golden Bay / Mohua

Golden Bay / Mohua is a large shallow bay in New Zealand's Tasman District, near the northern tip of the South Island. An arm of the Tasman Sea, the bay lies northwest of Tasman Bay / Te Tai-o-Aorere and Cook Strait. It is protected in the nor ...

, is estimated to be 400 or 500 years old, and stands tall with a circumference of at the base.

Known to Māori as , the tree was used as a source of food, particularly in the South Island, where it was cultivated in areas where other crops would not grow. It provided durable fibre

Fiber (spelled fibre in British English; from ) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorp ...

for textiles

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, and different types of #Fabric, fabric. ...

. Hardy and fast growing, it is widely planted in New Zealand gardens, parks and streets, and numerous cultivar

A cultivar is a kind of Horticulture, cultivated plant that people have selected for desired phenotypic trait, traits and which retains those traits when Plant propagation, propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root a ...

s are available. The tree can also be found in large numbers in island restoration

The ecological restoration of islands, or island restoration, is the application of the principles of ecological restoration to islands and island groups. Islands, due to their isolation, are home to many of the world's endemic (ecology), endemic ...

projects such as Tiritiri Matangi Island

Tiritiri Matangi Island is located in the Hauraki Gulf of New Zealand, east of the Whangaparāoa Peninsula in the North Island and north east of Auckland. The island is an open nature reserve managed by the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Incor ...

, where it was among the first seedling trees to be planted.

It is also grown as an ornamental tree in higher latitude Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

countries with maritime climates, including parts of the upper West Coast of the United States, Canada and the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, where its common names include Cornish palm, cabbage palm, Torbay palm and Torquay palm.

Description

''Cordyline australis'' grows up to tall with a stout trunk in diameter. Before it flowers, it has a slender unbranched stem. The first flowers typically appear at 6 to 10 years old, in spring. The right conditions can reduce the first flowering age to 3 years (Havelock North, 2015 mast year). After the first flowering, it divides to form a much-branched crown with tufts of leaves at the tips of the branches. Each branch may fork after producing a flowering stem. The pale to dark grey bark is corky, persistent and fissured, and feels spongy to the touch. The long narrow leaves are sword-shaped, erect, dark to light green, long and wide at the base, with numerous parallel veins. The leaves grow in crowded clusters at the ends of the branches, and may droop slightly at the tips and bend down from the bases when old. They are thick and have an indistinctmidrib

A primary vein, also known as the midrib, is the main vascular structure running through the center of a leaf. The primary vein is crucial for the leaf’s efficiency in photosynthesis and overall health, as it ensures the proper flow of material ...

. The fine nerves are more or less equal and parallel. The upper and lower leaf surfaces are similar.

In spring and early summer, sweetly perfumed flowers are produced in large, dense panicle

In botany, a panicle is a much-branched inflorescence. (softcover ). Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers (and fruit) be pedicellate (having a single stem per flower). The branches of a p ...

s (flower spikes) long, bearing well-spaced to somewhat crowded, almost sessile to sessile flowers and axes. The flowers are crowded along the ultimate branches of the panicles. The bract

In botany, a bract is a modified or specialized leaf, associated with a reproductive structure such as a flower, inflorescence axis or cone scale.

Bracts are usually different from foliage leaves in size, color, shape or texture. They also lo ...

s which protect the developing flowers often have a distinct pink tinge before the flowers open. In south Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

and North Otago

North Otago is an area in New Zealand that covers the area of the Otago region between Shag Point and the Waitaki River, and extends inland to the west as far as the village of Omarama (which has experienced rapid growth as a developing centre f ...

the bracts are green.

The individual flowers are in diameter, the tepal

A tepal is one of the outer parts of a flower (collectively the perianth). The term is used when these parts cannot easily be classified as either sepals or petals. This may be because the parts of the perianth are undifferentiated (i.e. of very ...

s are free almost to the base, and reflexed. The stamen

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

s are about the same length as the tepals. The stigmas are short and trifid. The fruit is a white berry in diameter which is greedily eaten by birds. The flowers have a "strong and sweet scent", and the nectar attracts great numbers of insects to the flowers.

Large, peg-like rhizome

In botany and dendrology, a rhizome ( ) is a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and Shoot (botany), shoots from its Node (botany), nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks or just rootstalks. Rhizomes develop from ...

s, covered with soft, purplish bark, up to long in old plants, grow vertically down beneath the ground. They serve to anchor the plant and to store fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

in the form of fructan

A fructan is a polymer of fructose molecules. Fructans with a short chain length are known as fructooligosaccharides. Fructans can be found in over 12% of the angiosperms including both monocots and dicotyledon, dicots such as agave, artichokes, a ...

. When young, the rhizomes are mostly fleshy and are made up of thin-walled storage cells. They grow from a layer called the secondary thickening meristem

In cell biology, the meristem is a structure composed of specialized tissue found in plants, consisting of stem cells, known as meristematic cells, which are undifferentiated cells capable of continuous cellular division. These meristematic c ...

.inflorescence

In botany, an inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a plant's Plant stem, stem that is composed of a main branch or a system of branches. An inflorescence is categorized on the basis of the arrangement of flowers on a mai ...

, or flower spike, produced in spring and early summer

File:Cabbagetreebark2.jpg, alt=Close-up of a tree trunk covered with rough bark, The corky, fissured bark of ''C. australis'' feels spongy to the touch.

Regional diversity

New Zealand's native ''Cordyline'' species are relics of an influx of tropical plants that arrived from the north 15 million years ago in the warmMiocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

era. Because it has evolved in response to the local climate, geology and other factors, ''C. australis'' varies in appearance from place to place. This variation can alter the overall appearance of the tree, canopy shape and branch size, the relative shape and size of the leaves, and their colour and stiffness. There may also be invisible adaptations for resistance to disease or insect attack. Some of these regional provenances are different enough to have been named by North Island Māori: in the north, in the central uplands, in the east and in the west.

In Northland, ''C. australis'' shows a great deal of genetic diversity—suggesting it is where old genetic lines have endured. Some trees in the far north have floppy, narrow leaves, which botanist Philip Simpson attributes to hybridisation with '' C. pumilio'', the dwarf cabbage tree.

In eastern Northland, ''C. australis'' generally has narrow, straight dark green leaves, but some trees have much broader leaves than normal and may have hybridised with the Three Kings cabbage tree, ''C. obtecta'', which grows at North Cape and on nearby islands. These ''obtecta''-like characteristics appear in populations of ''C. australis'' along parts of the eastern coastline from the Karikari Peninsula to the Coromandel Peninsula

The Coromandel Peninsula () on the North Island of New Zealand extends north from the western end of the Bay of Plenty, forming a natural barrier protecting the Hauraki Gulf and the Firth of Thames in the west from the Pacific Ocean ...

. In western Northland and Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

, a form often called grows. When young, are generally very spindly, and are common in young kauri

''Agathis'', commonly known as kauri or dammara, is a genus of evergreen coniferous trees, native to Australasia and Southeast Asia. It is one of three extant genera in the family Araucariaceae, alongside '' Wollemia'' and ''Araucaria'' (being ...

forests. When growing in the open, can become massive trees with numerous, long thin branches and relatively short, broad leaves.

In the central Volcanic Plateau, cabbage trees are tall, with stout, relatively unbranched stems and large stiff straight leaves. Fine specimens are found along the upper Whanganui River

The Whanganui River is a major river in the North Island of New Zealand. It is the country's third-longest river, and has special status owing to its importance to the region's Māori people. In March 2017 it became the world's second natur ...

. On old trees, the leaves tend to be relatively broad. The leaves radiate strongly, suggesting that tī manu is adapted to the cold winters of the upland central plateau. It may have originated in the open country created by lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

, volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

, and pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of extremely vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicula ...

. Trees of the tī manu type are also found in northern Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

, the King Country

The King Country ( Māori: ''Te Rohe Pōtae'' or ''Rohe Pōtae o Maniapoto'') is a region of the western North Island of New Zealand. It extends approximately from Kawhia Harbour and the town of Ōtorohanga in the north to the upper reaches of th ...

and the Bay of Plenty

The Bay of Plenty () is a large bight (geography), bight along the northern coast of New Zealand's North Island. It stretches from the Coromandel Peninsula in the west to Cape Runaway in the east. Called ''Te Moana-a-Toitehuatahi'' (the Ocean ...

lowlands.

Tarariki are found in the east of the North Island from East Cape

East Cape is the easternmost point of the main islands of New Zealand. It is at the northern end of the Gisborne District of the North Island. East Cape was originally named "Cape East" by British explorer James Cook during his 1769–1779 voy ...

to the Wairarapa

The Wairarapa (; ), a geographical region of New Zealand, lies in the south-eastern corner of the North Island, east of metropolitan Wellington and south-west of the Hawke's Bay Region. It is lightly populated, having several rural service t ...

. Māori valued the narrow spiky leaves as a source of particularly tough, durable fibre. Tarariki's strong leaf fibres may be an adaptation to the region's hot, dry summers. In parts of the Wairarapa, the trees are particularly spiky, with stiff leaves and partially rolled leaf-blades. The trees near East Cape, by contrast, have leaves that hang laxly on the tree. In Hawke's Bay

Hawke's Bay () is a region on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island. The region is named for Hawke Bay, which was named in honour of Edward Hawke. The region's main centres are the cities of Napier and Hastings, while the more rural ...

, some trees have greener, broader leaves, and this may be because of wharanui characteristics brought in across the main divide through the Manawatū Gorge

The Manawatū Gorge () is a steep-sided gorge formed by the Manawatū River in the North Island of New Zealand. At long, the Manawatū Gorge divides the Ruahine and Tararua Ranges, linking the Manawatū and Tararua Districts. It lies to the ...

.

Wharanui grow to the west of the North Island's main divide. They have long, broad flaccid leaves, which may be an adaptation to persistent westerly winds. The wharanui type occurs in Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

, Horowhenua and Whanganui

Whanganui, also spelt Wanganui, is a city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest navigable waterway. Whanganui is ...

, and extends with some modifications to the southern Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

coast. In Taranaki, cabbage trees generally have a compact canopy with broad straight leaves. In the South Island, wharanui is the most common form, but it is variable. The typical form grows, with little variation, from Cape Campbell to the northern Catlins

The Catlins (sometimes referred to as The Catlins Coast) comprise an area in the southeastern corner of the South Island of New Zealand. The area lies between Balclutha, New Zealand, Balclutha and Invercargill, straddling the boundary between ...

, and from the eastern coast to the foothills of the Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana. In Marlborough

Marlborough or the Marlborough may refer to:

Places Australia

* Marlborough, Queensland

* Principality of Marlborough, a short-lived micronation in 1993

* Marlborough Highway, Tasmania; Malborough was an historic name for the place at the sou ...

's Wairau Valley, cabbage trees tend to retain their old, dead leaves, lending them an untidy appearance. The climate there is an extreme one, with hot, dry summers and cold winters.

In north-west Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, there are three ecotype

Ecotypes are organisms which belong to the same species but possess different phenotypical features as a result of environmental factors such as elevation, climate and predation. Ecotypes can be seen in wide geographical distributions and may event ...

s defined by soil and exposure. Trees growing on limestone bluffs have stiff, blue-green leaves. On the river flats, the trees are tall with narrow, lax, dark green leaves, and an uneven canopy. They resemble the cabbage trees of the North Island's East Cape. Along the coast to the far west, the trees are robust with broad, bluish leaves. The latter two forms extend down the West Coast, with the lax-leaved forms growing in moist, fertile, sheltered river valleys while the bluish-leaved forms prefer rocky slopes exposed to the full force of the salt-laden coastal winds.

In

In Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

, cabbage trees gradually become less common towards the south until they come to an end in the northern Catlins. They reappear on the south coast at Waikawa, Southland, but they are not the wharanui type. Rather they are vigorous trees with broad, green leaves and broad canopies. Absent from much of Fiordland

Fiordland (, "The Pit of Tattooing", and also translated as "the Shadowlands"), is a non-administrative geographical region of New Zealand in the south-western corner of the South Island, comprising the western third of Southland. Most of F ...

, it was probably introduced by Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

to the Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ; Moriori language, Moriori: , 'Misty Sun'; ) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island, administered as part of New Zealand, and consisting of about 10 islands within an approxima ...

at 44° 00′S and to Stewart Island / Rakiura

Stewart Island (, 'Aurora, glowing skies', officially Stewart Island / Rakiura, formerly New Leinster) is New Zealand's third-largest island, located south of the South Island, across Foveaux Strait.

It is a roughly triangular island wit ...

at 46° 50′S. They extend along the coast towards Fiordland

Fiordland (, "The Pit of Tattooing", and also translated as "the Shadowlands"), is a non-administrative geographical region of New Zealand in the south-western corner of the South Island, comprising the western third of Southland. Most of F ...

, and inland to the margins of some of the glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

-fed lakes. Very vigorous when they are young, these trees seem well adapted to the very cold winters of the south.

A study of seedlings grown from seed collected in 28 areas showed a north-south change in leaf shape and dimensions. Seedling leaves get longer and narrower southwards. Seedlings often have leaves with red-brown pigmentation which disappears in older plants, and this colouration becomes increasingly common towards the south. The changes in shape—leaves getting narrower and more robust from north to south and from lowland to montane

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures lapse rate, fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is ...

—suggest adaptations to colder weather.

Taxonomy and names

''Cordyline australis'' was collected in 1769 by

''Cordyline australis'' was collected in 1769 by Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James Co ...

and Dr Daniel Solander, naturalists on the '' Endeavour'' during Lieutenant James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

's first voyage to the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

. The type locality is Queen Charlotte Sound / Tōtaranui. It was named ''Dracaena australis'' by Georg Forster

Johann George Adam Forster, also known as Georg Forster (; 27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German geography, geographer, natural history, naturalist, ethnology, ethnologist, travel literature, travel writer, journalist and revol ...

who published it as entry 151 in his ''Florulae Insularum Australium Prodromus'' of 1786. It is sometimes still sold as a '' Dracaena'', particularly for the house plant market in Northern Hemisphere countries. In 1833, Stephan Endlicher

Stephan Friedrich Ladislaus Endlicher, also known as Endlicher István László (24 June 1804 – 28 March 1849), was an Austrian Empire, Austrian botanist, numismatist and Sinologist. He was a director of the Botanical Garden of Vienna.

Biog ...

reassigned the species to the genus ''Cordyline

''Cordyline'' is a genus of about 24 species of woody monocotyledonous flowering plants in family (biology), family Asparagaceae, subfamily Lomandroideae. The subfamily has previously been treated as a separate family Laxmanniaceae, or Lomandrace ...

''.

The genus name ''Cordyline'' derives from an Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word for a club (''kordyle''), a reference to the enlarged underground stems or rhizome

In botany and dendrology, a rhizome ( ) is a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and Shoot (botany), shoots from its Node (botany), nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks or just rootstalks. Rhizomes develop from ...

s, while the species name ''australis'' is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for "southern". The common name ''cabbage tree'' is attributed by some sources to early settlers having used the young leaves as a substitute for cabbage. However, the name probably predates the settlement of New Zealand — Georg Forster, writing in his '' Voyage round the World'' of 1777 about the events of Friday, April 23, 1773, refers on page 114 to the discovery of a related species in Fiordland

Fiordland (, "The Pit of Tattooing", and also translated as "the Shadowlands"), is a non-administrative geographical region of New Zealand in the south-western corner of the South Island, comprising the western third of Southland. Most of F ...

as "not the true cabbage palm" and says "the central shoot, when quite tender, tastes something like an almond's kernel, with a little of the flavour of cabbage." Forster may have been referring to the cabbage palmetto (''Sabal palmetto'') of Florida, which resembles the Cordyline somewhat, and was named for the cabbage-like appearance of its terminal bud.

''Cordyline australis'' is the tallest of New Zealand's five native ''Cordyline'' species. Of these, the commonest are '' C. banksii'', which has a slender, sweeping trunk, and '' C. indivisa'', a handsome plant with a trunk up to tall bearing a massive head of broad leaves up to long. In the far north of New Zealand, ''C. australis'' can be distinguished by its larger heavily branched tree form, narrower leaves and smaller seeds from '' C. obtecta'', the Three Kings cabbage tree, its closest relative. ''C. australis'' is rather variable, and forms from the northern offshore islands may be hybrids with ''C. obtecta''. Hybrids with '' C. pumilio'' and ''C. banksii'' also occur often where the plants are in close vicinity, because they flower at about the same time and share the chromosome number

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

2n=38, with ''C. australis''.

The tree was well known to Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

before its scientific discovery. The generic Māori language

Māori (; endonym: 'the Māori language', commonly shortened to ) is an Eastern Polynesian languages, Eastern Polynesian language and the language of the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. The southernmost membe ...

term for plants in the genus ''Cordyline'' is ''tī'', cognate with Tongan ''sī'' and Hawaiian ''kī'' (from Proto-Austronesian

Proto-Austronesian (commonly abbreviated as PAN or PAn) is a proto-language. It is the reconstructed ancestor of the Austronesian languages, one of the world's major language families. Proto-Austronesian is assumed to have begun to diversify in ...

*''siRi'', ''C. fruticosa'' or ''C. terminalis''). Names recorded as specific to ''C. australis'' include ''tī kōuka'', ''tī kāuka'', ''tī rākau'', ''tī awe'', ''tī pua'', and ''tī whanake''. Each tribe had names for the tree depending on its local uses and characteristics. Simpson reports that the names highlight the characteristics of the tree that were important to Māori. These include what the plant looked like—whether it was a large tree (''tī rākau'', ''tī pua''), the whiteness of its flowers (''tī puatea''), whether its leaves were broad (''tī wharanui''), twisted along the edges (''tī tahanui''), or spiky (''tī tarariki''). Other names refer to its uses—whether its fruit attracted birds (''tī manu''), or the leaves were particularly suitable for making ropes (''tī whanake'') and nets (''tī kupenga''). The most widely used name, ''tī kōuka'', refers to the use of the leaf hearts as food.

Ecology

Habitat

A quote from Philip Simpson sums up the wide range of habitats the cabbage tree occupied in early New Zealand, and how much its abundance and distinctive form shaped the impression travellers received of the country:"In primeval New Zealand cabbage trees occupied a range of habitats, anywhere open, moist, fertile and warm enough for them to establish and mature: with forest; around the rocky coast; in lowland swamps, around the lakes and along the lower rivers; and perched on isolated rocks. Approaching the land from the sea would have reminded a Polynesian traveller of home, and for a European traveller, conjured up images of the tropical Pacific".''Cordyline australis'' occurs from North Cape to the very south of the South Island, where it becomes less and less common, until it reaches its southernmost natural limits at Sandy Point (46° 30' S), west of

Invercargill

Invercargill ( , ) is the southernmost and westernmost list of cities in New Zealand, city in New Zealand, and one of the Southernmost settlements, southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland Region, Southlan ...

near Oreti Beach. It is absent from much of Fiordland, probably because there is no suitable habitat, and is unknown on the subantarctic islands to the south of New Zealand, probably because it is too cold. It occurs on some offshore islands— Poor Knights, Stewart and the Chathams—but was probably introduced by Māori. In the Stewart Island region, it is rare, growing only on certain islands, headlands and former settlement sites where it may have been introduced by muttonbird collectors, while on the Chatham Islands it is also largely "a notable absentee".

Generally a lowland species, it grows from sea level to about , reaching its upper limits on the volcanoes of the central North Island, where eruptions have created open spaces for it to exploit, and in the foothills of the Southern Alps in the South Island, where deforestation may have played a part in giving it room to grow. In the central North Island, it has evolved a much sturdier form (with the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

name ''tī manu'', meaning "with branches bearing broad, straight upright leaves"). This form resembles that found in the far south of the South Island, suggesting that they are both adapted to cold conditions.

''Cordyline australis'' is a light-demanding pioneer species, and seedlings die when overtopped by other trees. To grow well, young plants require open space so they are not shaded out by other vegetation. Another requirement is water during the seedling stage. Although adult trees can store water and are drought resistant, seedlings need a good supply of water to survive. This stops the species from growing in sand dunes unless there are wet depressions present, and from hillsides unless there is a seepage area. The fertility of the soil is another factor—settlers in Canterbury used the presence of the species to situate their homesteads and gardens. The fallen leaves of the tree also help to raise the fertility of the soil when they break down. Another factor is temperature, especially the degree of frost. Young trees are killed by frost, and even old trees can be cut back. This is why ''C. australis'' is absent from upland areas and from very frosty inland areas.

Early European explorers of New Zealand described "jungles of cabbage trees" along the banks of streams and rivers, in huge swamps and lowland valleys. Few examples of this former abundance survive today—such areas were the first to be cleared by farmers looking for flat land and fertile soil. In modern New Zealand, cabbage trees usually grow as isolated individuals rather than as parts of a healthy ecosystem.

Reproduction

The cabbage tree's year begins in autumn among the tight spike of unopened leaves projecting from the centre of each tuft of leaves. Some of the growing tips have changed from making leaves to producinginflorescence

In botany, an inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a plant's Plant stem, stem that is composed of a main branch or a system of branches. An inflorescence is categorized on the basis of the arrangement of flowers on a mai ...

s for the coming spring, and around these, two or three buds begin to produce leaves. The inflorescence and the leaf buds pass the winter protected by the enveloping spike of unopened leaves. Months later in spring or early summer, it bears its flowers on the outside of the tree, exposed to insects and birds.

Flowering takes place over a period of four to six weeks, giving maximum exposure to pollinating insects. The flowers produce a sweet perfume which attracts large numbers of insects. The nectar produced by the flowers contains aromatic compounds, mainly ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

s and terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s, which are particularly attractive to moths. Bees use the nectar to produce a light honey to feed their young and increase the size of the hive in the early summer. It takes about two months for the fruit to ripen, and by the end of summer a cabbage tree can have thousands of small fruits available for birds to eat and disperse. The strong framework of the inflorescence can easily bear the weight of heavy birds like the New Zealand pigeon, which was formerly the major disperser of the seeds.

Each fruit contains three to six shiny, black seeds which are coated in a charcoal-like substance called phytomelan. The latter may serve to protect the seeds from the digestive process in the gut of a bird. The seeds are also rich in linoleic acid

Linoleic acid (LA) is an organic compound with the formula . Both alkene groups () are ''cis''. It is a fatty acid sometimes denoted 18:2 (n−6) or 18:2 ''cis''-9,12. A linoleate is a salt or ester of this acid.

Linoleic acid is a polyunsat ...

as a food source for the developing embryo plant, a compound which is also important in the egg-laying cycle of birds. Because it takes about two years for a particular stem to produce an inflorescence, cabbage trees tend to flower heavily in alternative years, with a bumper flowering every three to five years. Each inflorescence bears 5,000 to 10,000 flowers, so a large inflorescence may carry about 40,000 seeds, or one million seeds for the whole tree in a good flowering year—hundreds of millions for a healthy grove of trees.

Response to fire

''Cordyline australis'' is one of the few New Zealand forest trees that can recover from fire. It can renew its trunk from buds on the protected rhizomes under the ground. This gives the tree an advantage because it can regenerate itself quickly and the fire has eliminated competing plants. Cabbage tree leaves contain oils which make them burn readily. The same oils may also slow down the decay of fallen leaves, so that they build up a dense mat that prevents the seeds of other plants from germinating. When the leaves do break down, they form a fertile soil around the tree. Cabbage tree seed also has a store of oil, which means it remains viable for several years. When a bushfire has cleared the land of vegetation, cabbage tree seeds germinate in great numbers to make the most of the light and space opened up by the flames. Older trees sometimes growepicormic shoot

An epicormic shoot is a Shoot (botany), shoot growing from an epicormic bud, which lies underneath the Bark (botany), bark of a Trunk (botany), trunk, plant stem, stem, or branch of a plant.

Epicormic buds lie Dormancy, dormant beneath the bark, ...

s directly from their trunks after storm or fire damage. Aerial rhizomes can also be produced from the trunk if it sustains damage or has become hollow and grow down into the soil to regenerate the plant. Such regeneration can lead to trees of great age with multiple trunks.

Biodiversity

Many plants and animals are associated with ''C. australis'' in healthy ecosystems. The most common

Many plants and animals are associated with ''C. australis'' in healthy ecosystems. The most common epiphyte

An epiphyte is a plant or plant-like organism that grows on the surface of another plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphyt ...

s are ferns, astelias and orchids. Old trees often carry large clumps of the climbing fern ''Asplenium

''Asplenium'' is a genus of about 700 species of ferns, often treated as the only genus in the family (biology), family Aspleniaceae, though other authors consider ''Hymenasplenium'' separate, based on molecular phylogenetic analysis of DNA seque ...

'', and in moist places, filmy ferns and kidney ferns cling to the branches. ''Astelia

''Astelia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the recently named family Asteliaceae. They are rhizomatous tufted perennial plant, perennials native to various islands in the Pacific, Indian, and South Atlantic Oceans, as well as to Australia an ...

'' species and '' Collospermum'' often establish in the main fork of the tree, and one tree can host several species of native orchid. Other common epiphytes include '' Griselinia lucida'', as well as a range of mosses, liverworts, lichens and fungi. Two fungus species which infect living tissue—'' Phanaerochaeta cordylines'' and '' Sphaeropsis cordylines''—occur almost exclusively on ''C. australis''.

Animals and birds associated with ''C. australis'' include lizards which forage among the flowers, including the gold-striped gecko which is well camouflaged for life among the leaves of the tree. New Zealand bellbirds like to nest under the dead leaves or among the flower stalks, and paradise shelduck

The paradise shelduck (''Tadorna variegata''), also known as the paradise duck, or in Māori, is a species of shelduck, a group of goose-like ducks, which is endemic to New Zealand. Johann Friedrich Gmelin placed it in the genus '' Anas'' w ...

s commonly build their nests in the base of an old cabbage tree standing in the middle of a field. Red-crowned parakeet

The red-crowned parakeet (''Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae''), also known as red-fronted parakeet and by its Māori language, Māori name of ,Parr, M., Juniper, T., D'Silva, C., Powell, D., Johnston, D., Franklin, K., & Restall, R. (2010). Parrots ...

s are often seen foraging in cabbage trees. In South Canterbury, long-tailed bats shelter during the day in the hollow branches, which would once have provided nesting holes for many birds.

The berries of ''C. australis'' are enjoyed by bellbirds, tūī

The tūī (''Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae'') is a medium-sized bird native to New Zealand. It is blue, green, and bronze coloured with a distinctive white throat tuft (poi). It is an endemism, endemic passerine bird of New Zealand, and the on ...

, and kererū

The kererū (''Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae''), also known as kūkupa (Māori language#Northern dialects, northern Māori dialects), New Zealand pigeon or wood pigeon, is a species of pigeon native to New Zealand. Johann Friedrich Gmelin describ ...

. Māori sometimes planted groves of cabbage trees () to attract kererū which could be snared when they came to eat the berries. Reminiscing in 1903 about life in New Zealand sixty or more years earlier, George Clarke describes how such a tapu grove of cabbage trees would attract huge numbers of pigeons: "About four miles from our house, there was a great preserve of wood pigeons, that was made as tapu as the native chiefs could devise. At a certain season, the pigeons came in vast flocks to feed on the white berries of the Ti tree (bracœna) icand got so heavy with fat that they could hardly fly from one tree to another. No gun was allowed in the place. The Māoris, with a long slender rod and a slip noose at the end, squatted under the leaves and noiselessly slipped the noose over the necks of the stupid pigeons as they were feeding." As the native birds have vanished from much of New Zealand with the clearing of forests, it is now flocks of starling

Starlings are small to medium-sized passerine (perching) birds known for the often dark, glossy iridescent sheen of their plumage; their complex vocalizations including mimicking; and their distinctive, often elaborate swarming behavior, know ...

s which descend upon the fruit.

The nectar of the flowers is sought after by insects, bellbirds, tūī, and stitchbirds. The leaves and the rough bark provide excellent homes for insects such as caterpillars and moths, small beetles, fly larvae, wētā

Wētā (also spelled weta in English) is the common name for a group of about 100 insect species in the families Anostostomatidae and Rhaphidophoridae endemism, endemic to New Zealand. They are giant wingless insect, flightless cricket (insect ...

, snails and slugs. Many of these are then eaten by birds such as saddlebacks and robins. The rough bark also provides opportunities for epiphytes to cling and grow, and lizards hide amongst the dead leaves, coming out to drink the nectar and to eat the insects. Good flowering seasons occur every few years only. While it is said that they foretell dry summers, it has been observed that they tend to follow dry seasons.

Insects, including beetles, moths, wasps and flies, use the bark, leaves and flowers of the tree in various ways. Some feed or hide camouflaged in the skirt of dead leaves, a favourite dry place for wētā to hide in winter. Many of the insect companions of the tree have followed it into the domesticated surroundings of parks and home gardens. If the leaves are left to decay, the soil underneath cabbage trees becomes a black humus that supports a rich array of amphipods, earthworms and millipedes.

There are nine species of insect only found on ''C. australis'', of which the best known is '' Epiphryne verriculata'', the cabbage tree moth, which is perfectly adapted to hide on a dead leaf. Its caterpillars eat large holes and wedges in the leaves. The moth lays its eggs at the base of the central spike of unopened leaves. The caterpillars eat holes in the surface of the leaves and leave characteristic notches in the leaf margins. They can infest young trees but seldom damage older trees, which lack the skirt of dead leaves where the parent moths like to hide.

Threats, pests and diseases

Sudden decline

Cases of sick and dying trees of ''C. australis'' were first reported in the northern part of the North Island in 1987. The syndrome, eventually called sudden decline, soon reached epidemic proportions in Northland and Auckland. Affected trees usually suffer total defoliation within 2 to 12 months. The foliage turns yellow, and the oldest leaves wither and fall off. Growth of leaves ceases, and eventually all the leaves fall, leaving dead branches, often with the dried-out flowering panicles still attached. At the same time, the bark on the trunk becomes loose and detaches easily. The greatest number of dead trees (18 to 26 percent) was recorded around Auckland.

For some years, the cause of the disease was unknown, and hypotheses included tree ageing, fungi, viruses, and environmental factors such as an increase in ultra-violet light. Another hypothesis was that a genetic problem may have been induced in Northland and Auckland by the thousands of cabbage trees brought into the area from elsewhere and planted in gardens and parks. The Lands and Survey Department had a native plant nursery at

Cases of sick and dying trees of ''C. australis'' were first reported in the northern part of the North Island in 1987. The syndrome, eventually called sudden decline, soon reached epidemic proportions in Northland and Auckland. Affected trees usually suffer total defoliation within 2 to 12 months. The foliage turns yellow, and the oldest leaves wither and fall off. Growth of leaves ceases, and eventually all the leaves fall, leaving dead branches, often with the dried-out flowering panicles still attached. At the same time, the bark on the trunk becomes loose and detaches easily. The greatest number of dead trees (18 to 26 percent) was recorded around Auckland.

For some years, the cause of the disease was unknown, and hypotheses included tree ageing, fungi, viruses, and environmental factors such as an increase in ultra-violet light. Another hypothesis was that a genetic problem may have been induced in Northland and Auckland by the thousands of cabbage trees brought into the area from elsewhere and planted in gardens and parks. The Lands and Survey Department had a native plant nursery at Taupō

Taupō (), sometimes written Taupo, is a town located in the central North Island of New Zealand. It is situated on the edge of Lake Taupō, which is the largest freshwater lake in New Zealand. Taupō was constituted as a borough in 1953. It h ...

in the central North Island, which was used to grow plants for use in parks, reserves and carparks. In many Northland parks, cabbage trees from the central North Island were growing and flowering within metres of natural forms. Any offspring produced might have been poorly adapted to local conditions. After nearly five years of work, scientists found the cause was a bacterium '' Phytoplasma australiense'', which may be spread from tree to tree by a tiny sap-sucking insect, the introduced passion vine hopper.

Populations of ''C. australis'' were decimated in some parts of New Zealand because of sudden decline. In some areas, particularly in the north, no big trees are left. Although sudden decline often affects cabbage trees in farmland and open areas, trees in natural forest patches continue to do well. Trees in the southern North Island and northern South Island are generally unaffected with few dead branches and no symptoms of sudden decline. By 2010, there was evidence to suggest the severity of the disease was lessening.

Rural decline

The plight of ''Cordyline australis'' in the sudden decline epidemic drew attention to another widespread threat to the tree in rural areas throughout New Zealand. Rural Decline was the name proposed by botanists to refer to a decline in health of older trees in pasture and grazed shrubland, leading over many years to the loss of upper branches and eventual death. Often farmers would leave a solitary cabbage tree—or even groves of trees—standing after the swamps were drained. Most of these trees will slowly die out because livestock eat the seedlings and damage the trunks and roots of adult trees. When a cabbage tree is the only shade in a field, stock will shelter underneath it, damaging the bark by rubbing against it, and compacting the soil around the tree. Cows, sheep, goats, and deer eat the nutritious tissue under the bark of cabbage trees. Once the trunk has been damaged by animals, it seldom heals and the wounds get bigger over time. Eventually the tissue in the centre of the stem rots away and a cavity forms along its entire length. The trunk becomes misshapen or completely ring-barked for a metre above the ground. Often the growth layer dies and the injuries may lead to bacterial or fungal infections that spread into the branches until the canopy too begins to die. Other factors thought to contribute to Rural Decline include wood-rotting fungi like ''Phanerochaete cordylines'', micro-organisms which cause saprobic decay and leaf-feeding caterpillars. Other mammals can be destructive.Possums

Possum may refer to:

Animals

* Didelphimorphia, or (o)possums, an order of marsupials native to the Americas

** Didelphis, a genus of marsupials within Didelphimorphia

*** Common opossum, native to Central and South America

*** Virginia opossum, ...

tend not to eat the leaves of the tree but are very fond of eating the sugar-rich flowering stalks as they emerge. They also like using the tree as a sleeping place. Rabbits can be more destructive, especially during periods of drought, when they have been seen to eat through the base until a tree falls, and then eating the fallen tree completely. Horses can also fell a tree by eating through the trunk.

Māori cultural uses

Food

The stems and fleshy rhizomes of ''C. australis'' are high in natural sugars and were steam-cooked inearth oven

An earth oven, ground oven or cooking pit is one of the simplest and most ancient cooking structures. The earliest known earth oven was discovered in Central Europe and dated to 29,000 BC. At its most basic, an earth oven is a pit in the ground ...

s (''umu tī'', a large type of ''hāngī

Hāngī () is a traditional New Zealand Māori method of cooking food using heated rocks buried in a pit oven, called an ''umu''. It is still used for large groups on special occasions, as it allows large quantities of food to be cooked witho ...

'') to produce ''kāuru'', a carbohydrate-rich food used to sweeten other foods. The growing tips or leaf hearts were stripped of leaves and eaten raw or cooked as a vegetable, when they were called ''kōuka''—the origin of the Māori name of the tree. The southern limit of kūmara

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of the ...

(sweet potato) cultivation was at Banks Peninsula at 43°S, and south of there a culture developed around ''C. australis''. Natural and planted groves of the cabbage tree were harvested.

Large parties trimmed the cut stems and left them to dry for days or weeks. As well as stems, the rhizomes—extensions of the trunk below the surface of the ground shaped like enormous carrots—were also dug up to be cooked. In the early 1840s, Edward Shortland said Māori preferred rhizomes from trees growing in deep rich soil. They dug them in spring or early summer just before the flowering of the plant, when they were at their sweetest. November was the favourite month for preparing kāuru in the South Island.

After drying, the harvested stems or rhizomes were steamed for 24 hours or more in the umu tī pit. Steaming converted the carbohydrate fructan

A fructan is a polymer of fructose molecules. Fructans with a short chain length are known as fructooligosaccharides. Fructans can be found in over 12% of the angiosperms including both monocots and dicotyledon, dicots such as agave, artichokes, a ...

in the stems to very sweet fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

. The cooked stems or rhizomes were then flattened by beating and carried back to villages for storage. Kāuru could be stored dry until the time came to add it to fern root and other foods to improve their palatability. The sugar in the stems or rhizomes would be partially crystallised, and could be found mixed in a sugary pulp with other matter between the fibres of the root, which were easily separated by tearing them apart. Kāuru could also be dipped in water and chewed and was said to smell and taste like molasses

Molasses () is a viscous byproduct, principally obtained from the refining of sugarcane or sugar beet juice into sugar. Molasses varies in the amount of sugar, the method of extraction, and the age of the plant. Sugarcane molasses is usuall ...

.

Evidence of large cooking pits (umu tī) can still be found in the hills of South Canterbury

South Canterbury is the area of the Canterbury Region of the South Island of New Zealand bounded by the Rangitata River in the north and the Waitaki River (the border with the Otago Region) to the south. The Pacific Ocean and ridge of the S ...

and North Otago

North Otago is an area in New Zealand that covers the area of the Otago region between Shag Point and the Waitaki River, and extends inland to the west as far as the village of Omarama (which has experienced rapid growth as a developing centre f ...

, where large groves of cabbage trees still stand. Europeans used the plant to make alcohol, and the often alcoholically potent brews were relished by whalers and sealers.

The kōata, the growing tip of the plant, was eaten raw as medicine. When cooked, it was called the kōuka. If the spike of unopened leaves and a few outer leaves is gripped firmly at the base and bent, it will snap off. The leaves can be removed, and what remains is like a small artichoke heart that can be steamed, roasted or boiled to make kōuka, a bitter vegetable available at any time of the year. Kōuka is delicious as a relish with fatty foods like eel, muttonbirds, or pigeons, or in modern times, pork, mutton and beef. Different trees were selected for their degree of bitterness, which should be strong for medicinal use, but less so when used as a vegetable.

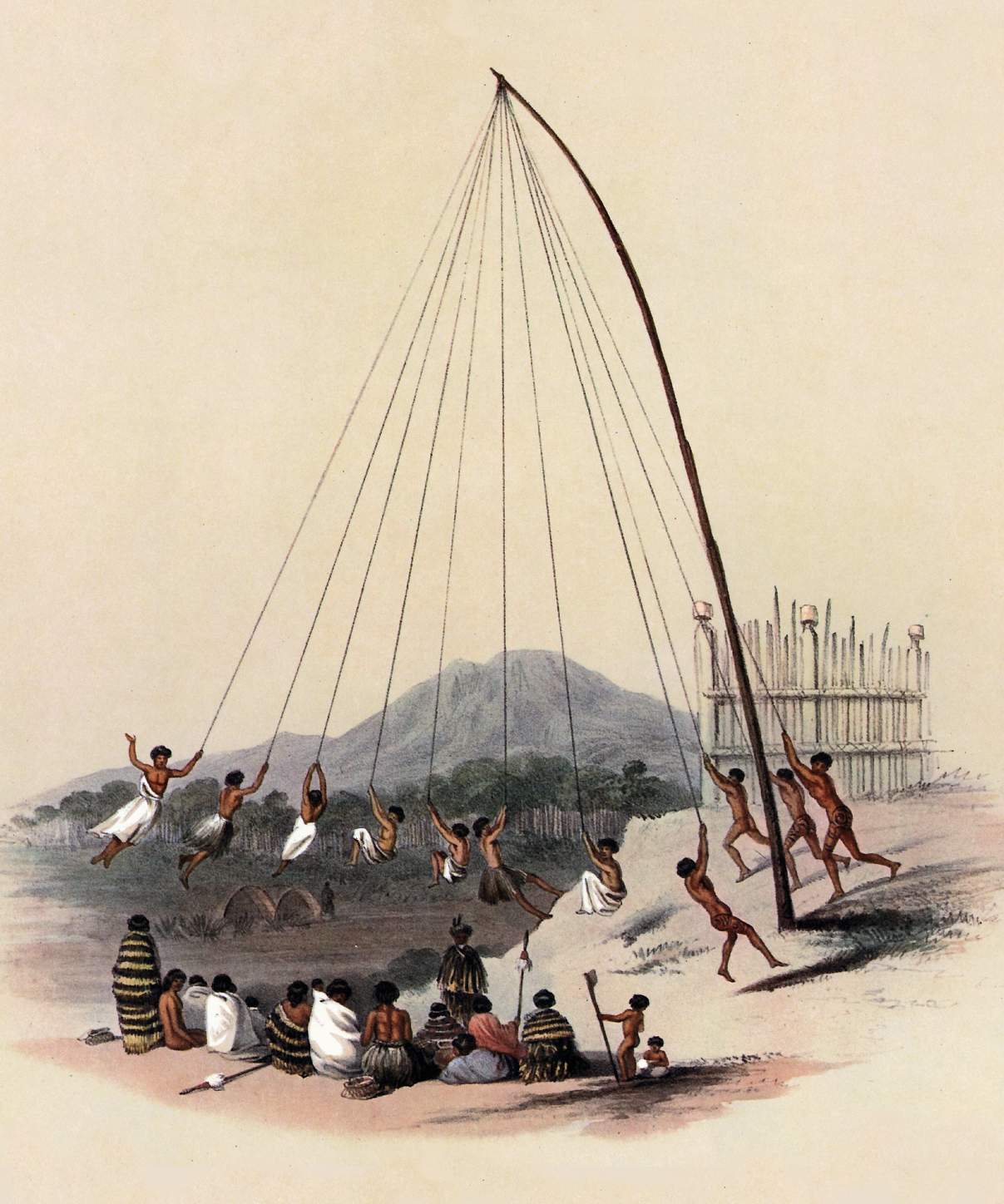

Fibre

A tough fibre was extracted from the leaves of ''C. australis'', and was valued for its strength and durability especially in seawater. The leaves are suitable for weaving in its raw state, without any need to further process the fibres. The leaves were used for making anchor ropes and fishing lines, cooking mats, baskets, sandals and leggings for protection when travelling in the South Island high country, home of the prickly speargrasses ('' Aciphylla'') and tūmatakuru or matagouri ('' Discaria toumatou''). Because of the water-resistant properties of the plant, the leaves were traditionally used for cooking baskets. Mōrere swings provided a source of amusement for Māori children. The ropes had to be strong, so they were often made from the leaves or fibre of ''C. australis'', which were much tougher than the fibres ofNew Zealand flax

New Zealand flax describes the common New Zealand perennial plants ''Phormium tenax'' and '' Phormium colensoi'', known by the Māori names ''harakeke'' and ''wharariki'' respectively. Although given the common name 'flax' they are quite disti ...

. The leaves were also used for rain capes, although the mountain cabbage tree ''C. indivisa'', was preferred. The fibre made from cabbage tree leaves is stronger than that made from New Zealand flax

New Zealand flax describes the common New Zealand perennial plants ''Phormium tenax'' and '' Phormium colensoi'', known by the Māori names ''harakeke'' and ''wharariki'' respectively. Although given the common name 'flax' they are quite disti ...

.

Medicine

In traditional rongoā medicinal practices, Māori used various parts of ''Cordyline australis'' to treat injuries and illnesses, either boiled up into a drink or pounded into a paste. The kōata, the growing tip of the plant, was eaten raw as a blood tonic or cleanser. Juice from the leaves was used for cuts, cracks and sores. An infusion of the leaves was taken internally for diarrhoea and used externally for bathing cuts. The leaves were rubbed until soft and applied either directly or as an ointment to cuts, skin cracks and cracked or sore hands. The young shoot was eaten by nursing mothers and given to children for colic. The liquid from boiled shoots was taken for other stomach pains. The seeds of ''Cordyline australis'' are high inlinoleic acid

Linoleic acid (LA) is an organic compound with the formula . Both alkene groups () are ''cis''. It is a fatty acid sometimes denoted 18:2 (n−6) or 18:2 ''cis''-9,12. A linoleate is a salt or ester of this acid.

Linoleic acid is a polyunsat ...

, one of the essential fatty acids.

Early European uses

''Cordyline australis'' was the first native plant in New Zealand used by early European settlers to produceliquor

Liquor ( , sometimes hard liquor), spirits, distilled spirits, or spiritous liquor are alcoholic drinks produced by the distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar that have already gone through ethanol fermentation, alcoholic ferm ...

. In the 1850s, distiller Owen McShane created a liquor made from ''Cordyline australis'' rhizomes, known variously as Cooper's Schnapps or McShane's Chained Lightning. McShane sold this to settlers and Māori in the lower South Island. Other early uses included woven hats worn by early settlers, and toboggan

A toboggan is a simple sled used in snowy winter recreation. It is also a traditional form of cargo transport used by the Innu, Cree and Ojibwe of North America, sometimes part of a dog train.

It is used on snow to carry one or more people (o ...

s made for children.

Cultivation today

''Cordyline australis'' is one of the most widely cultivated New Zealand native trees. In Northwest Europe and other cooloceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen climate classification, Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

s, it is very popular as an ornamental tree because it looks like a palm tree. Hardy forms from the coldest areas of the southern or inland South Island tolerate Northern Hemisphere conditions best, while North Island forms are much more tender. It can also be grown successfully in Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

s. It is easily grown from fresh seed — seedlings often spontaneously appear in gardens from bird-dispersed seed. It can also be propagated easily from shoot, stem and even trunk cuttings. It does well in pots and tubs.

It grows well as far north as the eastern coast of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, including the village of Portgower. It is more common in Southern England

Southern England, also known as the South of England or the South, is a sub-national part of England. Officially, it is made up of the southern, south-western and part of the eastern parts of England, consisting of the statistical regions of ...

and in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

where it is grown all over the island. Although not a palm, it is locally named Cornish palm, Manx palm or Torbay palm. The last name is due to its extensive use in Torbay

Torbay is a unitary authority with a borough status in the ceremonial county of Devon, England. It is governed by Torbay Council, based in the town of Torquay, and also includes the towns of Paignton and Brixham. The borough consists of ...

, it being the official symbol of that area, used in tourist posters promoting South Devon

South Devon is the southern part of Devon, England. Because Devon has its major population centres on its two coasts, the county is divided informally into North Devon and South Devon.For exampleNorth DevonanSouth Devonnews sites. In a narrower s ...

as the English Riviera. Even though its natural distribution ranges from 34° S to 46°S, and despite its ultimately subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones immediately to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Ge ...

origins, it also grows at about five degrees from the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

in Masfjorden, Norway, latitude 61ºN, in a microclimate

A microclimate (or micro-climate) is a local set of atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric conditions that differ from those in the surrounding areas, often slightly but sometimes substantially. The term may refer to areas as small as a few square m ...

protected from arctic winds and moderated by the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

.

Cultivars

In the North Island, Māori cultivated selected forms of ''C. australis'' for food. One of these, called tī para or tī tāwhiti, was grown because it suckers readily and forms multiple fleshy rhizomes. A dwarf non-flowering selection of ''C. australis'', it has a rubbery, pulpy stem, and thick green leaves. Although it was recorded by the early naturalists, botanists only rediscovered it in the 1990s, being grown by gardeners as the cultivar ''Cordyline'' 'Thomas Kirk'. Recent and unpublished DNA work suggests it derives from ''C. australis'' of the central North Island. ''Cordyline'' 'Tī Tawhiti' was "the subject of an intense discussion amongst the leading botanists of New Zealand at a meeting of the Royal Society ... in Wellington 100 years ago. It was saved from extinction because its dwarf form found favour with gardeners and it came to be known as Cordyline 'Kirkii' recording the interest Thomas Kirk had in the plant. Its origin as a Māori selection was forgotten until rediscovered in 1991. The name 'Tawhiti' is equivalent to 'Hawaiki' and indicates the traditional belief that the plant was introduced toAotearoa

''Aotearoa'' () is the Māori name for New Zealand. The name was originally used by Māori in reference only to the North Island, with the whole country being referred to as ''Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu'' – where ''Te Ika-a-Māui'' means N ...

by the ancestral canoes of Māori. However, it is more probable that the name arose from it being moved around its native land as a domesticated plant."

Numerous cultivars

A cultivar is a kind of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and which retains those traits when propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue cult ...

of ''C. australis'' are sold within New Zealand and around the world. Like other ''Cordyline'' species, ''C. australis'' can produce sports

Sport is a physical activity or game, often competitive and organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The number of participants in ...

which have very attractive colouration, including pink stripes and leaves in various shades of green, yellow or red. An early cultivar was published in France and England in 1870: ''Cordyline australis'' 'Lentiginosa' was described as having tinted leaves with brownish red spots. Other early cultivars included 'Veitchii' (1871) with crimson midribs, 'Atrosanguinea' (1882) with bronze leaves infused with red, 'Atropurpurea' (1886) and 'Purpurea' (1890) with purple leaves, and a range of variegated forms: 'Doucetiana' (1878), 'Argento-striata' (1888) and 'Dalleriana' (1890). In New Zealand and overseas, hybrids with other ''Cordyline'' species feature prominently in the range of cultivars available. New Plymouth

New Plymouth () is the major city of the Taranaki region on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the English city of Plymouth, in Devon, from where the first English settlers to New Plymouth migrated. The New Pl ...

plant breeders Duncan and Davies included hybrids of ''C. australis'' and ''C. banksii'' in their 1925 catalogue and have produced many new cultivars since. In New Zealand, some of the coloured forms and hybrids seem to be more susceptible to attacks from the cabbage tree moth.

Immature forms have become a popular annual house or ornamental plant under the name 'Spikes', or '' Dracaena'' 'Spikes'.

To add to the confusion, these may be misidentified as '' Cordyline indivisa'' ( syn. ''Dracaena indivisa'').

''C. australis'' is hardy to USDA zones 8–11.

AGM cultivars

In cultivation in the United Kingdom, the following have received theRoyal Horticultural Society

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), founded in 1804 as the Horticultural Society of London, is the UK's leading gardening charity.

The RHS promotes horticulture through its five gardens at Wisley (Surrey), Hyde Hall (Essex), Harlow Carr ...

's Award of Garden Merit

The Award of Garden Merit (AGM) is a long-established award for plants by the British Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). It is based on assessment of the plants' performance under UK growing conditions.

It includes the full range of cultivated p ...

:

*''C. australis''

*'Albertii'

*'Sundance'

*'Torbay Dazzler',

*'Torbay Red' (confirmed 2017)

See also

* Barry L. Frankhauser, an archaeologist and anthropologist, whose Ph.D. thesis (published 1986) was a study of historical uses of the cabbage treeNotes

Bibliography

* *Scheele, S. (2007)The 2006 Banks Memorial Lecture: Cultural uses of New Zealand native plants

''New Zealand Garden Journal'' 1:10–16. Retrieved 2010-04-04. *

Further reading

*Arkins, A. (2003). ''The Cabbage Tree''. Auckland.Reed Publishing

Reed Publishing (NZ) Ltd (formerly A. H. Reed Ltd and A. H. and A. W. Reed Ltd) was one of the leading publishers in New Zealand. It was founded by Alfred Hamish Reed and his wife Isabel in 1907. Reed's nephew Alexander Wyclif Reed joined the ...

.

*Harris, W. (2001). Horticultural and conservation significance of the genetic variation of cabbage trees (Cordyline spp.). In: Oates, M. R. ed. ''New Zealand plants and their story: proceedings of a conference held in Wellington 1–3 October 1999''. Lincoln, Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

The Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture (RNZIH) is a horticultural society in New Zealand.

History

According to its website, the RNZIH was founded in 1923. New Zealand's National Library holds minute books from the Institute dating back ...

. pp. 87–91.

*Harris, W. (2002). The cabbage tree. ''Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture'', 5, 3–9.

*Harris, W. (2003). Genotypic variation of height growth and trunk diameter of ''Cordyline australis'' (Lomandraceae) grown at three locations in New Zealand. ''New Zealand Journal of Botany'', 41, 637–652.

*Harris, W. (2004). Genotypic variation of dead leaf retention by ''Cordyline australis'' (Lomandraceae) populations and influence on trunk surface. ''New Zealand Journal of Botany'', 42, 833–844.

{{Authority control

australis

Endemic flora of New Zealand

Trees of New Zealand

Ornamental trees

Trees of mild maritime climate

Root vegetables

Taxa named by Stephan Endlicher

Plants described in 1786

Austronesian agriculture