C-command on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The first major revision to binding theory is found in Chomsky (1980) with their standard definitions: ::a. An anaphor ''α'' is ''bound'' in ''β'' if there is a category c-commanding it and coindexed with it in ''β'' ::b. Otherwise, ''α'' is free in ''β''

According to this rule, it is essential that NP2 (denoted as NPy in the tree on the left) be a pronoun for the sentence to be grammatical, despite NP1 (denoted as NPx on the tree) being a pronoun or not. This can be shown through the examples below.

a) Lucy greets the customers she serves.

b) *She greets the customers Lucy serves.

c) *Lucy greets the customers Lucy serves.

d) She greets the customers she serves.

In this edition of coreference, Lasnik sets some restrictions on the permissible locations of NP1 and NP2, which hint at potential dominance.

According to this rule, it is essential that NP2 (denoted as NPy in the tree on the left) be a pronoun for the sentence to be grammatical, despite NP1 (denoted as NPx on the tree) being a pronoun or not. This can be shown through the examples below.

a) Lucy greets the customers she serves.

b) *She greets the customers Lucy serves.

c) *Lucy greets the customers Lucy serves.

d) She greets the customers she serves.

In this edition of coreference, Lasnik sets some restrictions on the permissible locations of NP1 and NP2, which hint at potential dominance.

c-command and pronouns

University of Pennsylvania

Some Basic Concepts in Government and Binding Theory

* {{DEFAULTSORT:C-Command Syntactic relationships Generative syntax Syntax

generative grammar

Generative grammar is a research tradition in linguistics that aims to explain the cognitive basis of language by formulating and testing explicit models of humans' subconscious grammatical knowledge. Generative linguists, or generativists (), ...

and related frameworks, a node in a parse tree

A parse tree or parsing tree (also known as a derivation tree or concrete syntax tree) is an ordered, rooted tree that represents the syntactic structure of a string according to some context-free grammar. The term ''parse tree'' itself is use ...

c-commands its sister node and all of its sister's descendants. In these frameworks, c-command plays a central role in defining and constraining operations such as syntactic movement

Syntactic movement is the means by which some theories of syntax address discontinuities. Movement was first postulated by structuralist linguists who expressed it in terms of ''discontinuous constituents'' or ''displacement''. Some constituen ...

, binding, and scope. Tanya Reinhart

Tanya Reinhart (; 1943 – 17 March 2007) was an Israeli linguist and political activist. A frequent writer on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, she contributed columns to the Israeli centrist newspaper '' Yedioth Ahronoth'' and longer articles ...

introduced c-command in 1976 as a key component of her theory of anaphora. The term is short for " constituent command".

Definition and examples

Standard Definition

Common terms to represent the relationships between nodes are below (refer to the tree on the right): *M is a parent or mother to A and B. *A and B are children or daughters of M. *A and B are sisters or siblings. *M is a grandparent or grandmother to C and D. The standard definition of c-command is based partly on the relationship of dominance: ''Node N1 dominates node N2 if N1 is above N2 in the tree and one can trace a path from N1 to N2 moving only downwards in the tree (never upwards)''; that is, if N1 is a parent, grandparent, etc. of N2. For a node (N1) to c-command another node (N2) the parent of N1 must establish dominance over N2. Based upon this definition of dominance, node N1 ''c-commands'' node N2 if and only if: *Node N1 does not dominate N2, *N2 does not dominate N1, and *The first (i.e. lowest) branching node that dominates N1 also dominates N2. For example, according to the standard definition, in the tree at the right, * M does not c-command any node because it dominates all other nodes. * A c-commands B, C, D, E, F, and G. * B c-commands A. * C c-commands D, F, and G. * D c-commands C and E. * E does not c-command any node because it does not have a sister node or any daughter nodes. * F c-commands G. * G c-commands F. If node A c-commands node B, and B also c-commands A, it can be said that A ''symmetrically c-commands'' B. If A c-commands B but B does not c-command A, then A ''asymmetrically c-commands'' B. The notion of asymmetric c-command plays a major role in Richard S. Kayne's theory ofAntisymmetry

In linguistics, antisymmetry, is a theory of syntax described in Richard S. Kayne's 1994 book ''The Antisymmetry of Syntax''. Building upon X-bar theory, it proposes a universal, fundamental word order for phrases (Branching (linguistics), branchin ...

.

Where c-command is used

Standard Definition

A simplification of the standard definition on c-command is as follows: A node ''A'' c-commands a node ''B'' iff *Neither A nor B dominates the other, and *Every branching node dominating A also dominates B As such, we get sentences like: ::(1) ohnlikes erWhere ode AJohn c-commands ode B This means that ode Aalso c-commands ode Cand ode D which means that John c-commands both ikesand erSyntax Tree

In aParse tree

A parse tree or parsing tree (also known as a derivation tree or concrete syntax tree) is an ordered, rooted tree that represents the syntactic structure of a string according to some context-free grammar. The term ''parse tree'' itself is use ...

(syntax tree), nodes A and B are replaced with a DP constituent, where the DP John c-commands DP he. In a more complex sentence, such as (2), the pronoun could interact with its antecedent and be interpreted in two ways.

::(2) ohnsub>i thinks that esub>i/m is smart

In this example, two interpretations could be made:

::(i) John thinks that he is smart

::

::(ii) John thinks that someone else is smart

In the first interpretation, John c-commands he and also co-references he. Co-reference is noted by the same subscript (i) present under both of the DP nodes. The second interpretation shows that John c-commands he but does not co-reference the DP he. Since co-reference is not possible, there are different subscripts under the DP John (i) and the DP he (m).

Definite Anaphora

Example sentences like these shows the basic relationship of pronouns with its antecedent expression. However, looking at definite anaphora where pronouns takes a definite descriptions as its antecedent, we see that pronouns with name cannot co-refer with its antecedent within its domain. ::(3) Hei thinks that Johni* is smart Where ec-commands ohnbut esub>i cannot co-refer to ohnsub>i*, and we can only interpret that someone else thinks that John is smart. In response of the limits of c-command, Reinhart proposes a constraint on definite anaphora: ::A given pronoun P e.g., he in (3)must be interpreted as non-coreferential with any distinct non-pronouns .g. Johnin its c-command domain

Binding Theory

In linguistics, binding is the phenomenon in which anaphoric elements such as pronouns are grammatically associated with their antecedents. For instance in the English sentence "Mary saw herself", the anaphor "herself" is bound by its anteceden ...

The notion of c-command can be found in frameworks such as Binding Theory, which shows the syntactic relationship between pronouns and its antecedent. The binding theory framework was first introduced by Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

in 1973 in relation to the treatment of various anaphoric phenomena, and has since been revised throughout the years. Chomsky's analysis places a constraint on the relationship between a pronoun and a variable antecedent. As such, a variable cannot be the antecedent of a pronoun to its left. The first major revision to binding theory is found in Chomsky (1980) with their standard definitions: ::a. An anaphor ''α'' is ''bound'' in ''β'' if there is a category c-commanding it and coindexed with it in ''β'' ::b. Otherwise, ''α'' is free in ''β''

Quantificational Binding

Compared to definite anaphora, quantificational expressions works differently and is more restrictive. As proposed by Reinhart in 1973, a quantificational expression must c-command any pronoun that it binds. ::(3) very manthinks that eis intelligent. :::a. ∀x(man(x)): x thinks x is intelligent. (bound) :::b. ∀x(man(x)): x thinks y is intelligent. (coreferential or 'free') In this example, the quantifier very manc-commands the other pronoun eand a bound variable reading is possible as the pronoun 'he' is bound by the universal quantifier 'every man'. The sentence in (3) show two possible readings as a result of the bounding of pronouns with the universal quantifier. The reading in (3a) states that for ''all man'', they each think that ''they (he)'' are intelligent. Meanwhile, sentence (3b) state that for ''all men'', they all think that ''someone (he)'' is intelligent. In general, for a pronoun to be bound by the quantifier and bound variable reading made possible, (i) the quantifier must c-command the pronoun and (ii) both the quantifier and pronoun have to occur in the same sentence.History

Relative to the history of the concept of c-command, one can identify two stages: (i) analyses focused on applying c-command to solve specific problems relating to coreference and non-coreference; (ii) analyses which focused on c-command as a structural on a wide range of natural language phenomena that include but are not limited to tracking coreference and non-coreference.Stage 1: Coreference

The development of ‘c-command’ is introduced by the notion ofcoreference

In linguistics, coreference, sometimes written co-reference, occurs when two or more expressions refer to the same person or thing; they have the same referent. For example, in ''Bill said Alice would arrive soon, and she did'', the words ''Alice'' ...

. This is denoted by the first stage of the concept of c-command. In the initial emergence of coreference, Jackendoff (1972). officially states...

''If for any NP1 and NP2 in a sentence, there is no entry in the table NP2 + coref NP2, enter in the table NP1 - coref NP2 (OBLIGATORY)''

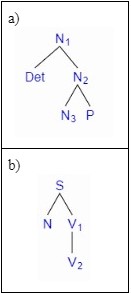

In other words, this rule states that any noun phrases that have not been associated with a coreference rule, are assumed to be noncoreferential. The tree to the right specifies this through the cyclical leftward movement of the pronoun and/or noun.

This is, then, edited by Lasnik (1976) in which...

''NP1 cannot be interpreted as coreferential with NP2 iff NP1 precedes and commands NP2 and NP2 is not a pronoun. If NP1 precedes and commands NP2, and NP2 is not a pronoun, then NP1 and NP1 are noncoreferential.'' According to this rule, it is essential that NP2 (denoted as NPy in the tree on the left) be a pronoun for the sentence to be grammatical, despite NP1 (denoted as NPx on the tree) being a pronoun or not. This can be shown through the examples below.

a) Lucy greets the customers she serves.

b) *She greets the customers Lucy serves.

c) *Lucy greets the customers Lucy serves.

d) She greets the customers she serves.

In this edition of coreference, Lasnik sets some restrictions on the permissible locations of NP1 and NP2, which hint at potential dominance.

According to this rule, it is essential that NP2 (denoted as NPy in the tree on the left) be a pronoun for the sentence to be grammatical, despite NP1 (denoted as NPx on the tree) being a pronoun or not. This can be shown through the examples below.

a) Lucy greets the customers she serves.

b) *She greets the customers Lucy serves.

c) *Lucy greets the customers Lucy serves.

d) She greets the customers she serves.

In this edition of coreference, Lasnik sets some restrictions on the permissible locations of NP1 and NP2, which hint at potential dominance.

Stage Two: Dominance

This leads to Stage 2 of the concept of c-command in which particular dominance is thoroughly explored. The term ''c-command'' was introduced byTanya Reinhart

Tanya Reinhart (; 1943 – 17 March 2007) was an Israeli linguist and political activist. A frequent writer on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, she contributed columns to the Israeli centrist newspaper '' Yedioth Ahronoth'' and longer articles ...

in her 1976 dissertation and is a shortened form of '' constituent command''. Reinhart thanks Nick Clements for suggesting both the term and its abbreviation. Reinhart (1976) states that...

''A commands node B iff the branching node ⍺1 most immediately dominating A either dominates B or is immediately dominated by a node ⍺2 which dominates B, and ⍺2 is of the same category type as ⍺1''

In other words, “⍺ c-commands β iff every branching node dominating ⍺ dominates β”

Chomsky adds a second layer to the previous edition of the c-command rule by introducing the requirement of maximal projections. He states...

''⍺ c-commands β iff every maximal projection dominating ⍺ dominates β''

This became known as "m-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, m-command is a syntactic relation between two nodes in a syntactic tree. A node X m-commands a node Y if the maximal projection of X dominates Y, but neither X nor Y dominates the other.

In govern ...

."

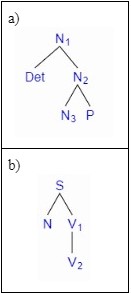

The tree to the right compares the two definitions in this stage. Reinhart's "c-command" focuses on the branching nodes whereas Chomsky's "m-command" focuses on the maximal projections.

The current and widely used definition of c-command that Reinhart had developed was not new to syntax. Similar configurational notions had been circulating for more than a decade. In 1964, Klima defined a configurational relationship between nodes he labeled "in construction with". In addition, Langacker proposed a similar notion of "command" in 1969. Reinhart's definition has also shown close relations to Chomsky's 'superiority relation.'

Criticism and Alternatives

Over the years, the validity and importance of c-command for the theory of syntax have been widely debated. Linguists such as Benjamin Bruening have provided empirical data to prove that c-command is flawed and fails to predict whether or not pronouns are being used properly.Bruening's take on c-command

In most cases, c-command correlates with precedence (linear order); that is, if node A c-commands node B, it is usually the case that node A also precedes node B. Furthermore, basic S(V)O (subject-verb-object)word order

In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how languages employ different orders. Correlatio ...

in English correlates positively with a hierarchy of syntactic function

In linguistics, grammatical relations (also called grammatical functions, grammatical roles, or syntactic functions) are functional relationships between constituents in a clause. The standard examples of grammatical functions from traditional g ...

s, subjects precede (and c-command) objects. Moreover, subjects typically precede objects in declarative sentences in English and related languages. Going back to Bruening (2014), an argument is presented which suggests that theories of the syntax that build on c-command have misconstrued the importance of precedence and/or the hierarchy of grammatical functions (i.e. the grammatical function of subject versus object). The grammatical rules of pronouns and the variable binding of pronouns that co-occur with quantified noun phrases and wh-phrases were originally grouped together and interpreted as being the same, but Bruening brings to light that there is a notable difference between the two and provides his own theory on this matter. Bruening suggests that the current function of c-command is inaccurate and concludes that what c-command is intended to address is more accurately analyzed in terms of precedence and grammatical functions. Furthermore, the c-command concept was developed primarily on the basis of syntactic phenomena of English, a language with relatively strict word order. When confronted with the much freer word order of many other languages, the insights provided by c-command are less compelling since linear order becomes less important.

As previously suggested, the phenomena that c-command is intended to address may be more plausibly examined in terms of linear order and a hierarchy of syntactic functions. Concerning the latter, some theories of syntax take a hierarchy of syntactic functions to be primitive. This is true of Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar

Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG) is a highly lexicalized, constraint-based grammar

developed by Carl Pollard and Ivan Sag. It is a type of phrase structure grammar, as opposed to a dependency grammar, and it is the immediate successor t ...

(HPSG), Lexical Functional Grammar

Lexical functional grammar (LFG) is a constraint-based grammar framework in theoretical linguistics. It posits several parallel levels of syntactic structure, including a phrase structure grammar representation of word order and constituency, an ...

(LFG), and dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern Grammar, grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of Phrase structure grammar, phrase structure) and that can be traced back prima ...

s (DGs). The hierarchy of syntactic functions that these frameworks posit is usually something like the following: SUBJECT > FIRST OBJECT > SECOND OBJECT > OBLIQUE OBJECT. Numerous mechanisms of syntax are then addressed in terms of this hierarchy

Barker's input on c-command

Like Bruening, Barker (2012) provides his own input on c-command, stating that it is not relevant for quantificational binding in English. Although not a complete characterization of the conditions in which a quantifier can bind a pronoun, Barker proposes a scope requirement.For more evidence and counterexamples to the requirement of c-command in quantificational binding, see Barker (2012). :Barker’s Scope Requirement: a quantifier must take scope over any pronoun that it binds : As such, a quantifier can take scope over a pronoun only if it can take scope over an existential inserted in the place of the pronoun ::(4) 'Each woman ''sub>i denied that 'she''sub>i met the shah ::(5) 'Each woman ''sub>i denied that 'someone''sub>i met the shah The sentence in (5) indicates that ach womanscopes over omeoneand this supports the claim that ach womancan take scope over a pronoun such as in (4). ::(6) The man who traveled with 'each woman ''sub>i denied that 'she''sub>j met the shah ::(7) The man who traveled with 'each woman ''sub>i denied that 'someone''sub>i met the shah* The sentence in (7) indicates that ach womancannot scope over omeoneand shows that the quantifier does not take scope over the pronoun. As such, there is no interpretation where ''each woman'' in a sentence (6) refers to ''she'' and coreference is not possible, which is indicated with a different subscript for ''she''. Bruening along with other linguists such as Chung-Chien Shan and Chris Barker has gone against Reinhart's claims by suggesting that variable binding and co-reference do not relate to each other. Barker (2012) aims to demonstrate how variable binding can function through the usage of continuations without c-command. This is achieved by avoiding the usage of c-command and instead focusing on the notion of precedence in order to present a system that is capable of binding variables and accounting events such as crossover violation. Barker shows that precedence, in the way of an evaluation order, can be used in the place of c-command.Wuijts' response to Barker's work

Another important work of criticism stems from Wuijts (2016) which is a response to Barker's stance on c-command and poses the question for Barker's work: How are “alternatives to c-command for the binding of pronouns justified and are these alternatives adequate?”. Wuijts dives deep into Barker's work and concludes that the semantic interpretation of pronouns serves as functions in their own context. Wuijts further claims that a binder can adopt the outcome as an argument and bind the pronoun all through a system that utilizes continuation without the notion of c-command. Both Bruening's and Barker's alternatives to c-command for the binding of pronouns are determined as ‘adequate alternatives’ which accurately show how co-reference and variable binding can operate without c-command. Wuijts brings forth two primary points that justify using a form of precedence: ::(1) Precedence is useful as it can be used to explain asymmetry which can not be explained through c-command ::(2) The natural utterance and construction of sentences justify using a form of precedence. Both Barker and Wuijts state that the goal is not to eliminate c-command entirely but to recognize that there are better alternatives that exist. In other words, c-command can still be used to effectively differentiate between strong and weak crossovers but it may not be as successful in other areas such as asymmetry which was previously mentioned. Wuijts concludes that a better alternative without c-command may be preferred and suggests that the current alternatives to c-command point to precedence, the binary relation between nodes in a tree structure, to be of great importance.Cho's investigation of Chomsky's binding theory

Keek Cho investigates Chomsky'sbinding theory

In linguistics, binding is the phenomenon in which anaphoric elements such as pronouns are grammatically associated with their antecedents. For instance in the English sentence "Mary saw herself", the anaphor "herself" is bound by its anteceden ...

and proposes that lexical items in the same argument structures that stem from the same predicates, require an m-command-based binding relation whereas lexical items in arguments structures that stem from different predicates require c-command based binding relations.

Cho (2019) challenges Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

’s binding theory (1995) by showing that its definition of c-command in binding principles B and C, fails to work in different argument structures of different predicates. Cho states that binding principles use m-command-based c-command for intra-argument structures and binding principles use command-based c-command for inter argument structure. With this statement, Cho implies that the notion of c-command used in binding principles is actually m-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, m-command is a syntactic relation between two nodes in a syntactic tree. A node X m-commands a node Y if the maximal projection of X dominates Y, but neither X nor Y dominates the other.

In govern ...

and both c-command and m-command have their own limitations.

Looking at Binding Relations in Intra-Argument Structures

By analyzing the following sentences, Cho is able to support the argument that the notion of c-command used in binding principles is actually m-command:

::(1a) The tall boyi will hurt himselfi

::(1b)*The short ladyi showed heri a picture of him

::(1c)*The matronly womani believes that we hate Jinai

By analyzing sentence (1a), it is apparent that the governing category for ''himself,'' the anaphor, is the entire sentence ''The tall boy will hurt himself.'' The antecedent, ''boy'', c-commands ''himself''. This is done in a way that allows for the categorial maximal projection of the former to c-command the categorial maximal projection of the latter. Cho argues that the notion of c-command in sentences (1a), (1b), and (1c) are in fact m-command and that the m-command-based binding principles deal with binding relations of lexical items and/or arguments that are in the same argument structure of a predicate.

In sentence (1a), ''boy'' and ''himself'' are lexical items that serve as external and internal arguments of ''hurt'', a two-place predicate. The two lexical items ''boy'' and ''himself'' are also in the same argument structure of the same predicate.

In sentence (1b), ''lady'' and ''her'' are lexical items that serve as external and internal arguments for ''showed'', a three-place predicate. The two lexical items ''lady'' and ''her'' are also in the same argument structure of the same predicate.

In sentence (1c), ''beliefs'' is a two-place main clause predicate and takes on ''woman,'' the subject, as its external argument and ''that we hate Jina,'' the embedded clause, as its internal argument.

Looking at Binding Relations in Inter-Argument Structures

Cho argues that binding relations in the intra-argument structures utilize m-command-based c-command which is limited to the binding relations of arguments and/or lexical items belonging to argument structures of the same predicate. Cho makes use of the following sentences to demonstrate how command-based c-command operates for inter-argument structure binding relations:

::(2a) The blond girl fainted when she heard the news

::(2b) She fainted when the blonde girl heard the news

::(2c) He has arrived and John will visit you

::(2d) John has arrived and he will visit you

::(2e) *John thinks she is good, and Tom thinks Mary is not good

::(2f) *He sat down after John entered the room

::(2g) After he entered the room, John sat down

Cho not only uses sentences (2a)-(2g) to explain command-based c-command and its role in inter-argument structure binding relations but also claims that command-based c-command can account for unexplained binding relations between different argument structures joined by a conjunctive phrase as well as explain why sentence (7d) is grammatical and (7e) is ungrammatical.

Implications

Memory

The notion of c-command shows the relation of pronouns with its antecedent expression. In general, pronouns, such as ''it'', are used to refer to previous concepts that are more prominent and highly predictable, and requires an antecedent representation that it refers back to. In order for a proper interpretation to occur, the antecedent representation must be made accessible within the comprehender's mind and then aligned with the appropriate pronoun, so that the pronoun will have something to refer to. There are studies that suggest that there is a connection between pronoun prominence and the referent in a comprehender's cognitive state. Research has shown that prominent antecedent representations are more active compared to less prominent ones. ::(i) "Where is my brush? Have you seen it?" In sentence (i), there is an active representation of the antecedent ''my brush'' in the comprehender's mind and it coreferences with the following pronoun ''it''. Pronouns tend to refer back to the salient object within the sentence, such as ''my brush'' in sentence (i). Furthermore, the more active an antecedent representation is the more it is readily available for interpretation when a pronoun emerges, which are then useful for operations such as pronoun resolution. ::(ii) "Where is my black bag with my brush and my hairties in it? Have you seen it?" In sentence (ii), ''my brush'' is less prominent as there are other objects within the sentence that are more prominent, such as ''my black bag''. The antecedent my black bag is more active in the representation in the comprehender's mind, as it is more prominent, and coreference for the pronoun ''it'' with the antecedent ''my brush'' is harder. Based on findings from memory retrieval studies, Foraker suggests that prominent antecedents have a higher retrieval time when a following pronoun is introduced. Furthermore, when sentences are syntactically clefted, antecedent representations, such as pronouns, become more distinctive in working memory, and are easily integrable in subsequent discourse operations. In other words, antecedent pronouns, when placed in the beginning of sentences, are easier to remember as it is held within their focal attention.See this website for focal attention definition. Thus, the sentences are easily interpreted and understood. They also found that gendered pronouns, such as ''he/she'', increases the prominence compared to unambiguous pronouns, such as ''it''. In addition, noun phrases also become more prominent in representation when syntactically clefted. It has also been suggested that there is a relationship between antecedent retrieval and its sensitivity to c-command restraints on quantificational binding, and that c-command facilitates the relational information, which help to retrieve antecedents and distinguish them from quantificational phrases that allows bound variable pronoun readings from quantificational phrases that do not.Autism

Recent research by Khetrapal and Thornton (2017) questioned whether children withAutism Spectrum Disorders

Autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by differences or difficulties in social communication and interaction, a preference for predictability and routine, sensory processing di ...

(ASD) are capable of computing the hierarchical structural relationship of c-command. Khetrapal and Thornton brought up the possibility that children with ASD may be relying on a form of linear strategy for reference assignment.Khetrapal and Thornton provide reasoning behind this hypothesis in Khetrapal and Thornton (2018). The study aimed to investigate the status of c-command in children with ASD by testing participants on their interpretation of sentences which incorporated the usage of c-command and a linear strategy for reference assignment. Researchers found that children with high-functioning autism (HFA) did not show any difficulties with computing the hierarchical relationship of c-command. The results suggest that children with HFA do not have syntactic deficiency however Kethrapal and Thornton stress that conducting further cross-linguistic investigation is essential.

See also

* Anaphora * Binding *Coreference

In linguistics, coreference, sometimes written co-reference, occurs when two or more expressions refer to the same person or thing; they have the same referent. For example, in ''Bill said Alice would arrive soon, and she did'', the words ''Alice'' ...

*Government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

*Government and Binding Government and binding (GB, GBT) is a theory of syntax and a phrase structure grammar in the tradition of transformational grammar developed principally by Noam Chomsky in the 1980s. This theory is a radical revision of his earlier theories and wa ...

*m-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, m-command is a syntactic relation between two nodes in a syntactic tree. A node X m-commands a node Y if the maximal projection of X dominates Y, but neither X nor Y dominates the other.

In govern ...

*Parse tree

A parse tree or parsing tree (also known as a derivation tree or concrete syntax tree) is an ordered, rooted tree that represents the syntactic structure of a string according to some context-free grammar. The term ''parse tree'' itself is use ...

* quantified expressions

Notes

References

*Ariel, M. (2016). ''Accessing noun-phrase antecedents''. London: Routledge. *Barker, C. (2012). Quantificational Binding Does Not Require C-command. ''Linguistic Inquiry'', (pp. 614–633). MIT Press. *Boeckx, C. (1999). Conflicting C-command requirements. ''Studia Linguistica'', 53(3), 227–250. *Bresnan, J. (2001). ''Lexical functional syntax''. Blackwell. *Bruening, B. (2014). Precede-and-command revisited. ''Language'', 90(1), 342–388. *Carminati, M. N., Frazier, L., and Rayner, K. (2002). Bound Variables and C-Command. ''Journal of Semantics''. 19(1): 1–34. *Carnie, A. (2002). ''Syntax: A generative introduction''. Oxford: Blackwell. *Carnie, A. (2013). ''Syntax: A generative introduction'', 3rd edition. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. *Cho, K. (2019). Two Different C-commands in Intra-Argument Structures and Inter-Argument Structures: Focus on Binding Principles B and A. ''British American Studies'' (pp. 79–100). Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. *Chomsky, N. (1995). "The Minimalist Program". MIT Press. *Frawley, W. (2003). C-command. "International Encyclopedia of Linguistics". *Foraker, S. (2004). The mechanisms involved in the prominence of referent representations during pronoun coreference (Doctoral dissertation, New York University, 2004). UMI ProQuest Digital Dissertations. *Foraker, S. and McElree, B. (2007). The role of prominence in pronoun resolution: Active versus passive representations. ''Journal of Memory and Language'', 56(3), 357–383. *Garnham, A. (2015). ''Mental models and the interpretation of anaphora''. New York. ISBN 9781138883123. *Garrod, S. and Terras, M. (May 2000). The Contribution of Lexical and Situational Knowledge to Resolving Discourse Roles: Bonding and Resolution. ''Journal of Memory and Language''. 42 (4): 526–544. *Haegeman, L. (1994). ''Introduction to Government and Binding Theory'', 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell. *Kayne, R. (1994). ''The antisymmetry of syntax''. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Twenty-Five. MIT Press. * Keshet, E. (2004-05-20). "24.952 Syntax Squib". MIT. *Khetrapal, Neha; Thornton, Rosalind (2017). "C-Command in the Grammars of Children with High Functioning Autism". Frontiers in Psychology. 8. . ISSN 1664-1078. *Klima, E. S. (1964). Negation in English. In J. A. Fodor and J. J. Katz (eds.), ''The structure of language: Readings in the philosophy of Language'' (pp. 246– 323). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. *Kush, D., Lidz, J., and Philips, C. (2015). Relation-sensitive retrieval: Evidence from bound variable pronouns. ''Journal of Memory and Language''. 82: 18–40. *Langacker, R. W. (1969). On pronominalization and the chain of command. In D. A. Reibel and S. A. Schane (eds), ''Modern studies in English: Readings in transformational grammar''(pp. 160–186). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. *Lasnik, H. (1976). Remarks on coreference. ''Linguistic Analysis'' 2, 1-22. *Lasnik, H. (1989). A selective history of modern binding theory. In: ''Essays on Anaphora''. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 16. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-2542-7_1 *Levine, R. and Hukari, T. (2006). ''The unity of unbounded dependency constructions''. Stanford, Calif.: CSLI Publications. *Lightfoot, D.W. (1975). Reviewed work: Semantic interpretation in generative grammar by Ray S. Jackendoff. ''Journal of Linguistics'', 11(1), 140-147 *Pollard, C. and Sag, I. (1994). ''Head-driven phrase structure grammar''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * Radford, A. (2004). ''English syntax: An introduction''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Reinhart, T. (1976). ''The syntactic domain of anaphora''. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (Available online at http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/16400). *Reinhart, T. (1981). Definite NP anaphora and C-command domains. ''Linguistic Inquiry'', 12(4), 605–635. *Reinhart, T. (1983). ''Anaphora and semantic interpretation''. London: Croom Helm. *Reuland, E. (2007). Binding Theory. In M. Everaert and H. van Riemsdijk (eds.), ''The Blackwell companion to syntax,'' ch.9. Oxford: Blackwell. *Shan, Chung-Chieh; Barker, Chris (2006). "Explaining Crossover and Superiority as Left-to-right Evaluation". Linguistics and Philosophy. 29 (1): 91–134. . ISSN 0165-0157. *Sportiche, D., Koopman, H. J., and Stabler, E. P. (2013; 2014). ''An introduction to syntactic analysis and theory''. Hoboken: John Wiley. *Wuijts, Rogier (October 29, 2015). "Binding pronouns with and without c-command". Utrecht University. *Zhang, H. (2016). The c-command condition in phonology. ''Syntax-Phonology Interface'' (pp. 71–116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781317389019-10External links

c-command and pronouns

University of Pennsylvania

Some Basic Concepts in Government and Binding Theory

* {{DEFAULTSORT:C-Command Syntactic relationships Generative syntax Syntax