Bølling–Allerød Interstadial on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

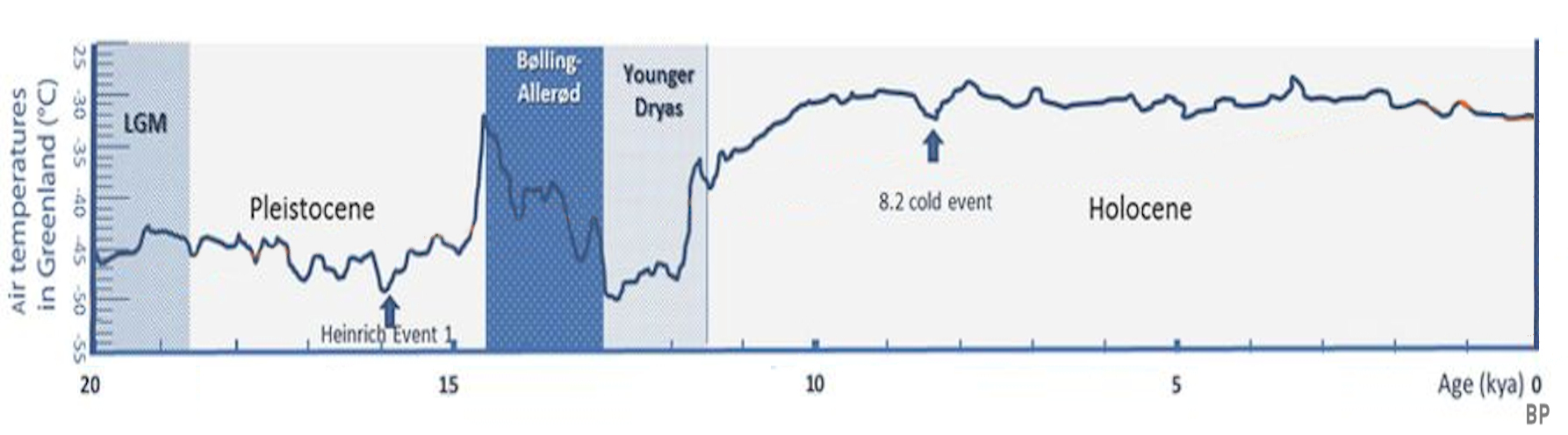

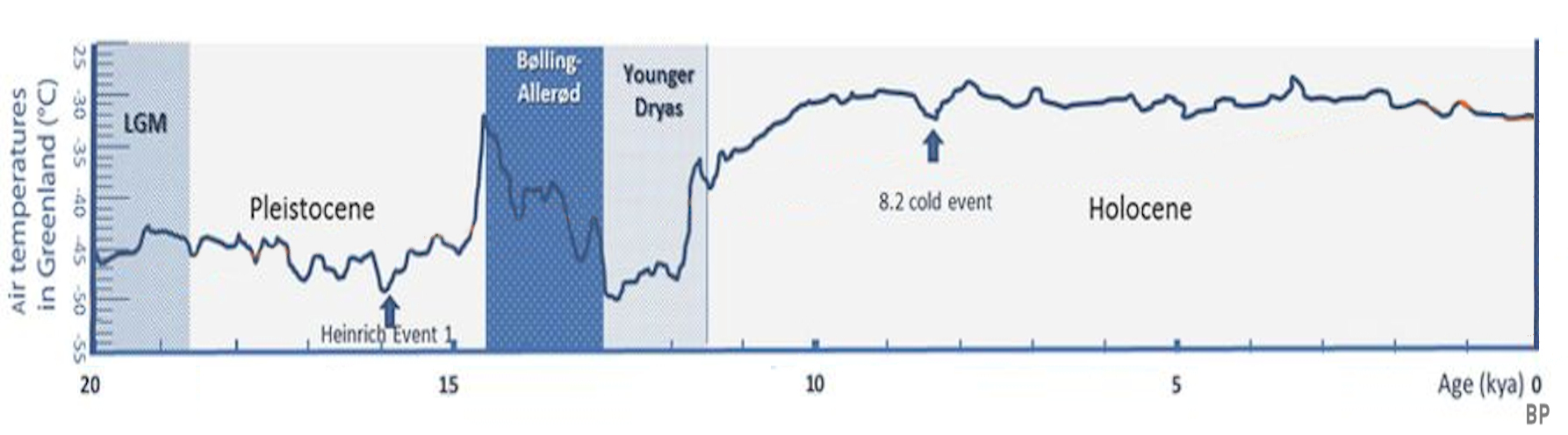

The Bølling–Allerød Interstadial (), also called the Late Glacial Interstadial (LGI), was an

In 1901, Danish geologists Nikolaj Hartz (1867–1937) and Vilhelm Milthers (1865–1962) found deposits of

In 1901, Danish geologists Nikolaj Hartz (1867–1937) and Vilhelm Milthers (1865–1962) found deposits of

interstadial

Stadials and interstadials are phases dividing the Quaternary period, or the last 2.6 million years. Stadials are periods of colder climate, and interstadials are periods of warmer climate.

Each Quaternary climate phase has been assigned with a ...

period which occurred from 14,690 to years Before Present

Before Present (BP) or "years before present (YBP)" is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because ...

, during the final stages of the Last Glacial Period. It was defined by abrupt warming in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

, and a corresponding cooling in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as a period of major ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

collapse and corresponding sea level rise

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

known as Meltwater pulse 1A

Meltwater pulse 1A (MWP1a) is the name used by Quaternary geologists, paleoclimatologists, and oceanographers for a period of rapid post-glacial sea level rise, between 14,700 and 13,500 years ago, during which the global sea level rose betwee ...

. This period was named after two sites in Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

where paleoclimate

Paleoclimatology ( British spelling, palaeoclimatology) is the scientific study of climates predating the invention of meteorological instruments, when no direct measurement data were available. As instrumental records only span a tiny part of ...

evidence for it was first found, in the form of vegetation fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s that could have only survived during a comparatively warm period in Northern Europe. It is also referred to as Interstadial 1 or Dansgaard–Oeschger event

A Dansgaard–Oeschger event (often abbreviated D–O event), is a rapid climate fluctuation; such events occurred 25 times during the last glacial period. Some scientists say that the events occur quasi-periodically with a recurrence time being ...

1.

This interstadial followed the Oldest Dryas period, which lasted from ~18,000 to 14,700 BP. While Oldest Dryas was still significantly colder than the current epoch, the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

, globally it was a period of warming from the very cold Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

, caused by a gradual increase in concentrations. A warming of around had occurred during this period, nearly half of which had taken place during its last couple of centuries. In contrast, the entire Bølling–Allerød Interstadial experienced very little change in global temperature. Instead, the rapid warming was limited to the Northern Hemisphere, while the Southern Hemipshere had experienced equivalent cooling. This "polar seesaw

A seesaw (also sometimes known as a teeter-totter in North America) is a long, narrow board supported by a single pivot point, most commonly located at the midpoint between both ends; as one end goes up, the other goes down. These are most comm ...

" pattern had occurred due to the strengthening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is the main ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean.IPCC, 2021Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Sem ...

(and the corresponding weakening of the Southern Ocean overturning circulation). These changes in thermohaline circulation had caused far more heat to be transferred from the Southern Hemisphere to the North.

For human populations of the Northern Hemisphere, Bølling–Allerød Interstadial had represented the first pronounced warming since the end of the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

(LGM). The cold had previously forced them into refuge areas, but the warming of the interstadial enabled them to begin repopulating the Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

n landmass. The abrupt Northern cooling of the subsequent Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

may have triggered the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

, with the adoption of agriculture in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

.

Discovery

In 1901, Danish geologists Nikolaj Hartz (1867–1937) and Vilhelm Milthers (1865–1962) found deposits of

In 1901, Danish geologists Nikolaj Hartz (1867–1937) and Vilhelm Milthers (1865–1962) found deposits of birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

trees in a clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

pit near Allerød Municipality

Allerød Kommune is a municipality (Danish language, Danish, ''Commune (country subdivision), kommune'') on the island of Zealand (Denmark), Zealand (''Sjælland'') in eastern Denmark. The municipality covers an area of 67 km2, and has a popul ...

on Zealand

Zealand ( ) is the largest and most populous islands of Denmark, island in Denmark proper (thus excluding Greenland and Disko Island, which are larger in size) at 7,031 km2 (2715 sq. mi.). Zealand had a population of 2,319,705 on 1 Januar ...

island and later in the drained peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

deposits at Bølling Lake Bølling can refer to:

* Bølling lake, Denmark – a shallow lake in central Jutland, after which the following are named:

*The Bølling Oscillation or Interstadial – a warm phase during the last phase of the Weichsel glaciation in Europe; ofte ...

in Jutland

Jutland (; , ''Jyske Halvø'' or ''Cimbriske Halvø''; , ''Kimbrische Halbinsel'' or ''Jütische Halbinsel'') is a peninsula of Northern Europe that forms the continental portion of Denmark and part of northern Germany (Schleswig-Holstein). It ...

peninsula (both parts of Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

). This provided proxy evidence for consistent warming at these sites during the last glacial period, because the temperatures were warm enough to support these trees. In contrast, the rest of the glacial period was so cold that the dominant plant in the area was a small, cold-adapted flower called ''Dryas octopetala

''Dryas octopetala'', the mountain avens, eightpetal mountain-avens, white dryas or white dryad, is an Arctic–alpine flowering plant in the family Rosaceae. It is a small prostrate evergreen subshrub forming large colonies. The specific epithe ...

''. Thus, the cold period which preceded this interstadial is known as the Oldest Dryas, and the two subsequent cold periods as the Older

Older is the comparative form of " old". It may refer to:

Music

* ''Older'' (George Michael album), 1996

** "Older" (George Michael song), 1996

* ''Older'' (Lizzy McAlpine album), 2024

** "Older" (Lizzy McAlpine song), 2024

* "Older" (5 Seco ...

and Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

.

Additional evidence for this period involves the gathering of oxygen isotope stages (OIS) from stratified deep-sea sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

cores. Samples are gathered and measured for change in isotope levels to determine temperature fluctuation for given periods of time.

Timing

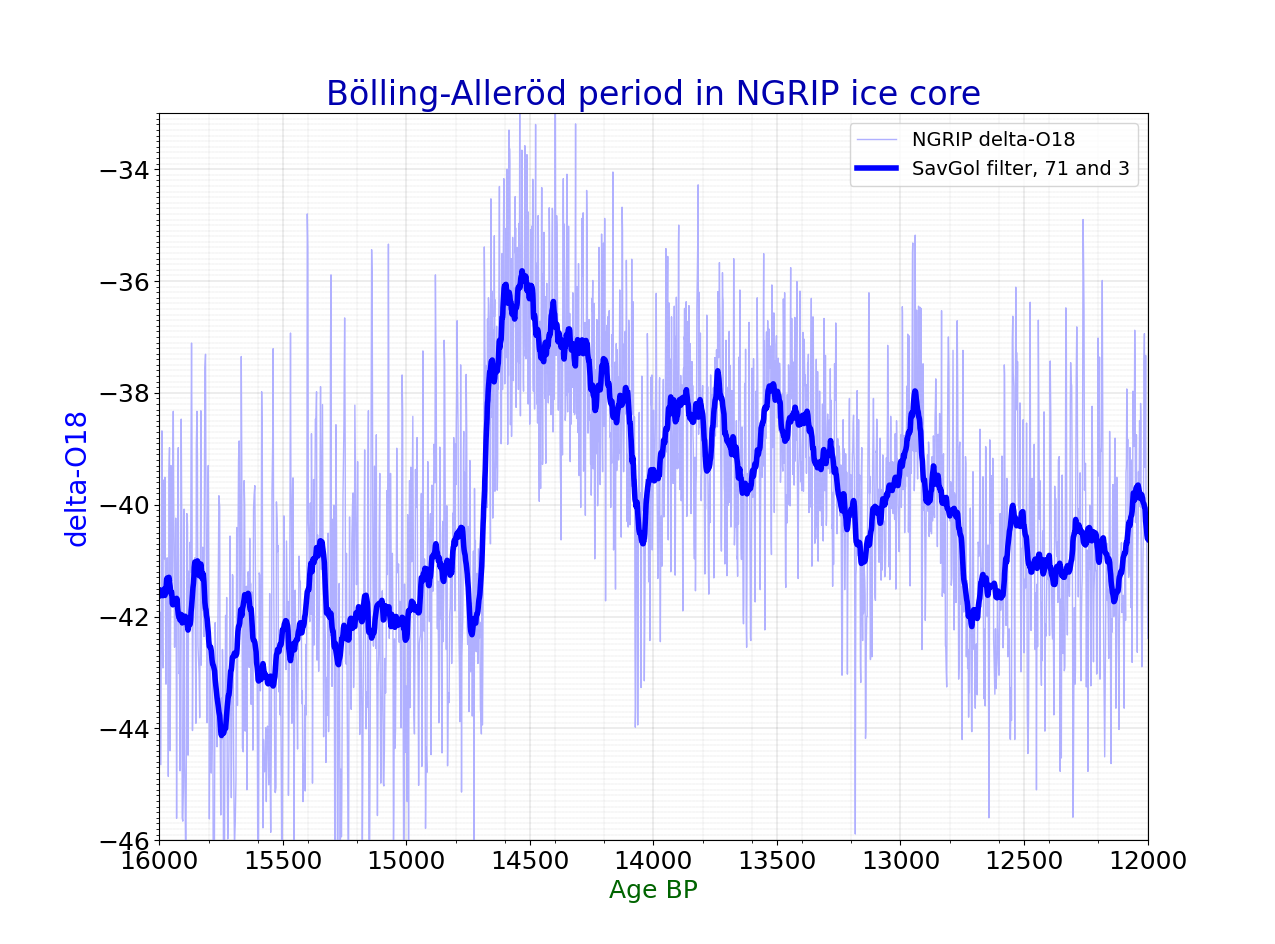

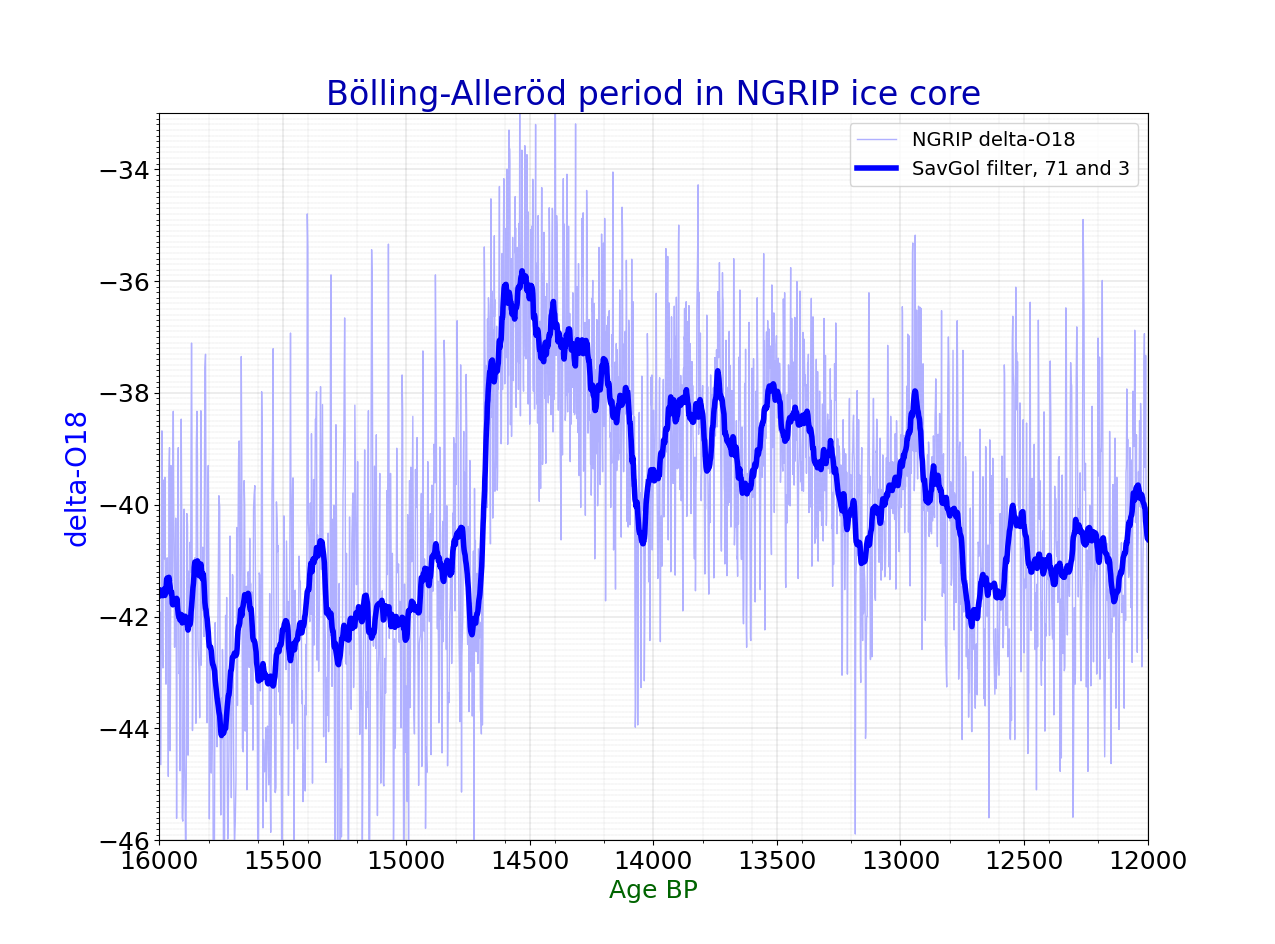

This interstadial is commonly divided into three stages. The initial Bølling stage had the largest hemispheric temperature change, and it is also the stage when Meltwater Pulse 1A had occurred. The beginning of the Bølling is also end of the Oldest Dryas at approximately 14,600 years BP. The Oxygen isotope record fromGreenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

ice indicates that the Bølling stage lasted approximately 600 years.

It was then interrupted by the older Older Dryas (after ''Dryas octopetala

''Dryas octopetala'', the mountain avens, eightpetal mountain-avens, white dryas or white dryad, is an Arctic–alpine flowering plant in the family Rosaceae. It is a small prostrate evergreen subshrub forming large colonies. The specific epithe ...

'', an Arctic plant widespread during such cold periods in the Northern Hemisphere). The Older Dryas lasted approximately one century. before northern hemisphere warming returned during the Allerød stage.

The Allerød stage was a warm and moist global interstadial

Stadials and interstadials are phases dividing the Quaternary period, or the last 2.6 million years. Stadials are periods of colder climate, and interstadials are periods of warmer climate.

Each Quaternary climate phase has been assigned with a ...

that occurred c.13,900 to 12,900 BP. It raised temperatures in the northern Atlantic region to almost present-day levels, before they declined again in the Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

, which was followed by the present warm Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

. The interstadial stage started abruptly with a decline in temperatures within a decade and the onset of the glacial Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

. Global temperatures declined only slightly during YD, and they had steadily climbed alongside the concentrations once that period had transitioned to Holocene. There may have also been another brief cold stage during Allerød.

In regions where the Older Dryas is not detected in climatological evidence, the Bølling–Allerød is considered a single interstadial period.

Causes

The strengthening of theAtlantic meridional overturning circulation

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is the main ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean.IPCC, 2021Annex VII: Glossary While increase had also occurred during this interstadial, it was at a rate of 20–35 ppmv within 200 years, or less than half of the increase of the recent 50 years, and role in global warming was dwarfed by the opposing hemispheric changes caused by thermohaline circulation.

Some research shows that a warming of had occurred at intermediate depths in the North Atlantic over the preceding several millennia during Heinrich event">Heinrich stadial 1 (HS1). The authors postulated that this warm salty water (WSW) layer, situated beneath the colder surface freshwater in the North Atlantic, generated ocean convective available potential energy (OCAPE) over decades at the end of HS1. According to fluid modelling, at one point the accumulation of OCAPE was released abruptly (c. 1 month) into kinetic energy of thermobaric cabbeling convection (TCC), resulting in the warmer salty waters getting to the surface and subsequently warming the sea surface by approximately .

The climate began to improve rapidly throughout

The climate began to improve rapidly throughout

Belarus

The Bølling–Allerød

Climate change clues revealed by ice sheet collapse

Sensitivity and rapidity of vegetational response to abrupt climate change

{{Timeline of the history of Scandinavia Last Glacial Period History of climate variability and change Nordic Stone Age Pleistocene Historical eras

Geophysical effects

Records obtained from the Gulf of Alaska show abrupt sea-surface warming of about 3 °C (in less than 90 years), matching ice-core records that register this transition as occurring within decades. Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) cooled slightly during this interstadial. TheMeltwater pulse 1A

Meltwater pulse 1A (MWP1a) is the name used by Quaternary geologists, paleoclimatologists, and oceanographers for a period of rapid post-glacial sea level rise, between 14,700 and 13,500 years ago, during which the global sea level rose betwee ...

event coincides with or closely follows the abrupt onset of the Bølling–Allerød (BA), when global sea level rose about 16 m during this event at rates of 26–53 mm/yr. In the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

, the Bølling–Allerød period is associated with a substantial accumulation of calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

, which is consistent with the modelled cooling of the region.

A 2017 study attributed the second Weichselian Icelandic ice sheet collapse, onshore (est. net wastage 221 gigatons of ice per year over 750 years) and similar to today's Greenland rates of mass loss, to atmospheric Bølling–Allerød warming. The melting of the glaciers of Hardangerfjord

The Hardangerfjord () is the fifth longest fjord in the world, and the second longest fjord in Norway. It is located in Vestland county in the Hardanger region. The fjord stretches from the Atlantic Ocean into the mountainous interior of No ...

began during this interstadial. Boknafjord had already begun to deglaciate before the onset of the Bølling–Allerød interstadial. Some research suggests that isostatic rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound ...

in response to glacier retreat (unloading) and an increase in local salinity (i.e., δ18Osw) was associated with increased volcanic activity at the onset of Bølling–Allerød. Notably, volcanic ash fallout on glacier surfaces could have had enhanced their melting through ice-albedo feedback.

The deep oceans were depleted in radiocarbon

Carbon-14, C-14, C or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic matter is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

during the deglaciation following the LGM, which has been hypothesised to be the result of sluggish meridional overturning circulation or due to a release of volcanic carbon or methane clathrates into abyssal waters. The Eastern Tropical Pacific Oxygen Minimum Zone (ETP-OMZ) witnessed high oxygen depletion during the early stages of the deglaciation following the LGM, most likely as a result of a weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is the main ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean.IPCC, 2021Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Sem ...

(AMOC) and an increased influx of nutrient-rich waters due to intensified upwelling.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the weakened Southern Ocean overturning circulation caused the expansion of Antarctic Intermediate Water, which sequesters less effectively than the Antarctic bottom water, and this was likely the main reason for the increase in concentrations during the interstadial. The Bølling–Allerød was almost completely synchronous across the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

.

Effects on humans

Western Europe and the North European Plain

The climate began to improve rapidly throughout

The climate began to improve rapidly throughout Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and the North European Plain

The North European Plain ( – North German Plain; ; – Central European Plain; and ; French: ''Plaine d'Europe du Nord'') is a geomorphological region in Europe that covers all or parts of Belgium, the Netherlands (i.e. the Low Countries), ...

c. 16,000-15,000 years ago. The environmental landscape became increasingly boreal, except in the far north, where conditions remained arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

. Sites of human occupation reappeared in northern France, Belgium, northwest Germany, and southern Britain between 15,500 and 14,000 years ago. Many of these sites are classified as Magdalenian

Magdalenian cultures (also Madelenian; ) are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years before present. It is named after the type site of Abri de la Madeleine, a ro ...

. In Britain, the Creswellian culture developed as an offshoot of the Magdalenian

Magdalenian cultures (also Madelenian; ) are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years before present. It is named after the type site of Abri de la Madeleine, a ro ...

.

As the Fennoscandian ice sheet continued to shrink, plants and people began to repopulate the freshly deglaciated areas of southern Scandinavia. Large parts of what is now the southern part of the North Sea became dry land, now named Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

. This was a low landscape with soft hills, rivers, and lakes. By the end of the interstadial, Doggerland was probably covered by a sparse birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

woodland, with flourishing fauna such as mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

s and red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

.

Prey favored by European hunters included reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

, wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

, European fallow deer

The European fallow deer (''Dama dama''), also known as the common fallow deer or simply fallow deer, is a species of deer native to Eurasia. It is one of two living species of fallow deer alongside the Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamica'' ...

, red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

, and European wild ass

The European wild ass (''Equus hydruntinus'' or ''Equus hemionus hydruntinus'') or hydruntine is an extinct equine from the Middle Pleistocene to Late Holocene of Europe and West Asia, and possibly North Africa. It is a member of the subgenus ''A ...

.

East European Plain

Periglacialloess

A loess (, ; from ) is a clastic rock, clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loesses or similar deposition (geology), deposits.

A loess ...

-steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

environments prevailed across the East European Plain

The East European Plain (also called the Russian Plain, "Extending from eastern Poland through the entire European Russia to the Ural Mountains, the ''East European Plain'' encompasses all of the Baltic states and Belarus, nearly all of Ukraine, ...

, but climates improved slightly during several brief interstadials and began to warm significantly after the beginning of the Late Glacial Maximum. Pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by most types of flowers of seed plants for the purpose of sexual reproduction. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced Gametophyte#Heterospory, microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm ...

profiles for this time indicate a pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

-birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

interspersed with the steppe in the deglaciated northern plain, birch-pine forest

A forest is an ecosystem characterized by a dense ecological community, community of trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, ...

with some broadleaf trees in the central region, and steppe in the south. The pattern reflects the reemergence of a marked zonation of biome

A biome () is a distinct geographical region with specific climate, vegetation, and animal life. It consists of a biological community that has formed in response to its physical environment and regional climate. In 1935, Tansley added the ...

s with the decline of glacial conditions. Human site occupation density was most prevalent in the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

region and increased as early as around 16,000 years ago. Reoccupation of northern territories of the East European Plain did not occur until 13,000 years ago.

Generally, lithic technology is dominated by blade production and typical Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories ...

tool forms such as burins and backed blades (the most persistent). Kostenki archaeological sites of multiple occupation layers

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

persist from the Last Glacial Maximum on the eastern edge of the Central Russian Upland

The Central Russian Upland (also: Middle Russian Upland () and East European Upland) is an upland area of the East European Plain and is an undulating plateau with an average elevation of . Its highest peak is measured at . The southeastern porti ...

, along the Don River

The Don () is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its basin is betwee ...

. Epigravettian archaeological sites, similar to Eastern Gravettian

The Gravettian is an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by ...

sites, are common in the southwest, central, and southern regions of the East European Plain about 17,000 to 10,000 years BP and are also present in the Crimea and Northern Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

.

The time of the Epigravettian also reveals evidence for tailored clothing production, a tradition persisting from preceding Upper Paleolithic archaeological horizons. Fur-bearing small mammal remains abound such as Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small species of fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Tundra#Arctic tundra, Arctic tundra biome. I ...

and paw bones of hares

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The genu ...

, reflecting pelt removal. Large and diverse inventories of bone, antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the Cervidae (deer) Family (biology), family. Antlers are a single structure composed of bone, cartilage, fibrous tissue, skin, nerves, and blood vessels. They are generally fo ...

, and ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

implements are common, and ornamentation and art are associated with all major industries. Insights into the technology of the time can also be seen in features such as structures, pits, and hearths mapped on open-air occupation areas scattered across the East European Plain.

Mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

were typically hunted for fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

, bone shelter, and bone fuel. In the southwest region around the middle Dnestr Valley, sites are dominated by reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

and horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

, accounting for 80 to 90% of the identifiable large mammal remains. Mammoth is less common, typically 15% or less, as the availability of wood eliminated the need for heavy consumption of bone fuel and collection of large bones for construction. Mammoth remains may have been collected for other raw material, namely ivory. Other large mammals in modest numbers include steppe bison

The steppe bison (''Bison'' ''priscus'', also less commonly known as the steppe wisent and the primeval bison) is an extinct species of bison which lived from the Middle Pleistocene to the Holocene. During the Late Pleistocene, it was widely dist ...

and red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

.

Plant foods more likely played an increasing role in the southwest region than in the central and southern plains since southwest sites consistently yield grinding stones widely thought to have been used for preparation of seeds, roots, and other plant parts.

Siberian Plain

During the interstadial, Siberian human occupations sites are confined to latitudes below 57°N and most are C14 dated from 19,000 to 14,000 years ago. Settlements differed from those of the East European Plain as they reflected a more mobile lifestyle by the absence of mammoth-bone houses and storage pits, all indicators of long-term settlement. Visual art was uncommon. Fauna remained red deer, reindeer, and moose and indicate a mainly meat-oriented diet. The habitat of Siberia was far harsher than anywhere else and often did not provide enough survival opportunities for its human inhabitants. That is what forced human groups to remain dispersed and mobile, as is reflected in the lithic technology, as tiny blades were typically manufactured, often termed microblades less than 8 mm wide with unusually sharp edges indicating frugality from low resource levels. They were fixed into grooves along one or both edges of a sharpened bone or antler point. Specimens of complete microblade-inset points have been recovered from both Kokorevo and Chernoozer'e. At Kokorevo, one was found embedded in abison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

shoulder blade.

As climates warmed further around 15,000 years ago, fish began to populate rivers, and technology used to harvest them, such as barbed harpoons, first appeared on the Upper Angara River. People expanded northwards into the Middle Lena Basin.

The Dyuktai culture, near Dyuktai Cave, on the Aldan River at 59°N, is similar to southern Siberian sites and includes the wedge-shaped cores and microblades, along with some bifacial tools, burins, and scrapers. The site likely represents the material remains of the people who spread across the Bering Land Bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72° north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of the ...

and into the New World.

Asia

''δ''18O records from Valmiki Cave insouthern India

South India, also known as Southern India or Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of ...

indicate extreme shifts in Indian Summer Monsoon intensity at Termination 1a, which marks the start of the Bølling–Allerød and occurred about 14,800 BP.

In the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, the pre-agricultural Natufian

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

settled around the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

coast to exploit wild cereals, such as emmer

Emmer is a hybrid species of wheat, producing edible seeds that have been used as food since ancient times. The domesticated types are ''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccum'' and ''T. t. ''conv.'' durum''. The wild plant is called ''T. t.'' s ...

and two-row barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

. By the time of the Allerød, the Natufians may have started to domesticate grain, bake bread, and ferment alcohol.

North America

Over the land between the Lena Basin and northwestCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, increased aridity occurred during the Last Glacial Maximum. Sea level fell to about 120 m below its present position, exposing a dry plain between Chukotka and western Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. Clear skies reduced precipitation, and loess

A loess (, ; from ) is a clastic rock, clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loesses or similar deposition (geology), deposits.

A loess ...

deposition promoted well-drained, nutrient-rich soils that supported diverse steppic plant communities and herds of large grazing mammals. The wet tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

soils and spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' ( ), a genus of about 40 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal (taiga) regions of the Northern hemisphere. ''Picea'' ...

bogs that exist today were absent.

Cold temperatures and massive ice sheets covered most of Canada and the northwest coast, thus preventing human colonization of North America prior to 16,000 years ago. An "ice-free corridor" through western Canada to the northern plains is thought to have opened up no earlier than 13,500 years ago. However, deglaciation in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

may have taken place more rapidly and a coastal route could have been available by 17,000 years ago. Rising temperatures and increased moisture accelerated environmental change after 14,000 years ago, as shrub tundra replaced dry steppe in many parts of Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 70th parallel north, 72° north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south ...

.

Camp settlement sites are found along Tanana River

The Tanana River (Lower Tanana language, Lower Tanana: Tth'eetoo', Upper Tanana language, Upper Tanana: ''Tth’iitu’ Niign'') is a tributary of the Yukon River in the U.S. state of Alaska. According to linguist and anthropologist William Brig ...

in central Alaska by 14,000 years ago. Earliest occupation levels at the Tanana Valley sites contain artifacts similar to the Siberian Dyuktai culture. At Swan Point, these comprise microblades, burins, and flakes struck from bifacial tools. Artifacts at the nearby site of Broken Mammoth are few, but include several rods of mammoth ivory. The diet was of large mammals and birds, as indicated by fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

l remains.

Earliest site occupation at Ushki sites of central Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and western coastlines, respectively.

Immediately offshore along the Pacific ...

(about 13,000 years ago) display evidence of small oval houses and bifacial points. Stone pendants, beads, and a burial pit are present. In central Alaska up the northern foothills at the Dry Creek site c. 13,500-13,000 years ago near Nenana Valley, small bifacial points were found. People were thought to have moved into this area to hunt elk and sheep on a seasonal basis. Microblade sites typologically similar to Dyuktai appear about 13,000 years ago in central Kamchatka and throughout many parts of Alaska.

Genetics

The European distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroup I and various associated subclades has also been explained as resulting from male postglacial recolonization of Europe from refugia in the Balkans, Iberia, and the Ukraine/Central Russian Plain. Males possessing haplogroup Q are postulated as representing a significant portion of the population who crossed Beringia and populated North America for the first time. The distribution of mtDNA haplogroup H has been postulated as representing the major female repopulating of Europe from the Franco-Cantabrian region after the Last Glacial Maximum. mtDNA haplogroups A, B, C, D and X are interpreted according to some as supporting a single pre-Clovis populating of the Americas via a coastal route.See also

*Antarctic Cold Reversal

The Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR) was a climatic event of intense atmospheric and oceanic cooling across the southern hemisphere (>40°S) between 14,700 and 13,000 years before present ( BP) that interrupted the most recent deglacial climate warm ...

* Dansgaard–Oeschger event

A Dansgaard–Oeschger event (often abbreviated D–O event), is a rapid climate fluctuation; such events occurred 25 times during the last glacial period. Some scientists say that the events occur quasi-periodically with a recurrence time being ...

* Hiawatha Glacier

* Ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

* Mammoth steppe

The mammoth steppe, also known as steppe-tundra, was once the Earth's most extensive biome. During glacial periods in the later Pleistocene, it stretched east-to-west, from the Iberian Peninsula in the west of Europe, then across Eurasia and thr ...

References

External links

Belarus

The Bølling–Allerød

Climate change clues revealed by ice sheet collapse

{{Timeline of the history of Scandinavia Last Glacial Period History of climate variability and change Nordic Stone Age Pleistocene Historical eras