Broad-billed Parrot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The broad-billed parrot or raven parrot (''Lophopsittacus mauritianus'') is a large

In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway speculated that reports of grey Mauritian parrots referred to the broad-billed parrot. In 1973, based on remains collected by the French amateur naturalist Louis Etienne Thirioux in the early 20th century, the British ornithologist Daniel T. Holyoak placed a small subfossil Mauritian parrot in the same genus as the broad-billed parrot and named it '' Lophopsittacus bensoni''. In 2007, on the basis of a comparison of subfossils, and correlated with old descriptions of small grey parrots, the British

In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway speculated that reports of grey Mauritian parrots referred to the broad-billed parrot. In 1973, based on remains collected by the French amateur naturalist Louis Etienne Thirioux in the early 20th century, the British ornithologist Daniel T. Holyoak placed a small subfossil Mauritian parrot in the same genus as the broad-billed parrot and named it '' Lophopsittacus bensoni''. In 2007, on the basis of a comparison of subfossils, and correlated with old descriptions of small grey parrots, the British

The broad-billed parrot had a disproportionately large head and jaws, and the skull was flattened from top to bottom, unlike in other Mascarene parrots. Ridges on the skull indicate that its distinct frontal crest of feathers was firmly attached, and that the bird, unlike cockatoos, could not raise or lower it. The width of the hind edge of the

The broad-billed parrot had a disproportionately large head and jaws, and the skull was flattened from top to bottom, unlike in other Mascarene parrots. Ridges on the skull indicate that its distinct frontal crest of feathers was firmly attached, and that the bird, unlike cockatoos, could not raise or lower it. The width of the hind edge of the

Sexual dimorphism in beak size may have affected behaviour. Such dimorphism is common in other parrots, for example in the

Sexual dimorphism in beak size may have affected behaviour. Such dimorphism is common in other parrots, for example in the

Species that are morphologically similar to the broad-billed parrot, such as the

Species that are morphologically similar to the broad-billed parrot, such as the  The Brazilian ornithologist Carlos Yamashita suggested in 1997 that macaws once depended on now-extinct South American

The Brazilian ornithologist Carlos Yamashita suggested in 1997 that macaws once depended on now-extinct South American

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

parrot

Parrots (Psittaciformes), also known as psittacines (), are birds with a strong curved beak, upright stance, and clawed feet. They are classified in four families that contain roughly 410 species in 101 genus (biology), genera, found mostly in ...

in the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Psittaculidae

Psittaculidae is a family of parrots, commonly known as Old World parrots, though this term is a misnomer, as not all its members occur in the Old World and Psittacinae also occurs in the Old World. It consists of six subfamilies: Psittricha ...

. It was endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to the Mascarene

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of Réunion. Their na ...

island of Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

. The species was first referred to as the "''Indian raven''" in Dutch ships' journals from 1598 onwards. Only a few brief contemporary descriptions and three depictions are known. It was first scientifically described

A species description is a formal scientific description of a newly encountered species, typically articulated through a scientific publication. Its purpose is to provide a clear description of a new species of organism and explain how it diffe ...

from a subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

mandible in 1866, but this was not linked to the old accounts until the rediscovery of a detailed 1601 sketch that matched both the subfossils and the accounts. It is unclear what other species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

it was most closely related to, but it has been classified as a member of the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

Psittaculini, along with other Mascarene parrots. It had similarities with the Rodrigues parrot (''Necropsittacus rodricanus''), and may have been closely related.

The broad-billed parrot's head was large in proportion to its body, and there was a distinct crest of feathers on the front of the head. The bird had a very large beak, comparable in size to that of the hyacinth macaw

The hyacinth macaw (''Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus''), or hyacinthine macaw, is a parrot native to central and eastern South America. With a length (from the top of its head to the tip of its long pointed tail) of about one meter it is longer tha ...

, which would have enabled it to crack hard seeds. Its bones indicate that the species exhibited greater sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in overall size and head size than any living parrot. The exact colouration is unknown, but a contemporary description indicates that it had multiple colours, including a blue head, and perhaps a red body and beak. It is believed to have been a weak flier, but not flightless

Flightless birds are birds that cannot fly, as they have, through evolution, lost the ability to. There are over 60 extant species, including the well-known ratites ( ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwis) and penguins. The smal ...

. The species became extinct sometime in the late 17th century due to deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

, predation by introduced invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

, and possibly hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

.

Taxonomy

The earliest known descriptions of the broad-billed parrot were provided by Dutch travellers during the Second Dutch Expedition to Indonesia, led by the Dutch Admiral Jacob Cornelis van Neck in 1598. They appear in reports published in 1601, which also contain the first illustration of the bird, along with the first of adodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

. The description for the illustration reads: "5* Is a bird which we called the ''Indian Crow'', more than twice as big as the parroquets, of two or three colours". The Dutch sailors who visited Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

categorised the broad-billed parrots separately from parrots, and referred to them as "''Indische ravens''" (translated as either "Indian raven

A raven is any of several large-bodied passerine bird species in the genus '' Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between crows and ravens; the two names are assigne ...

s" or "''Indian crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly, a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not linked scientifically to any certain trait but is rathe ...

s''") without accompanying useful descriptions, which caused confusion when their journals were studied. The Dutch painter Jacob Savery lived in a house in Amsterdam called "''In de Indische Rave''" (Dutch for "''in the Indian raven''") until 1602, since Dutch houses had signboards instead of numbers at the time. While he and his brother, the painter Roelant Savery

Roelant Savery (or ''Roeland(t) Maertensz Saverij'', or ''de Savery'', or many variants; 1576 – buried 25 February 1639) was a Flanders-born Dutch Golden Age painter.

Life

Savery was born in Kortrijk. Like so many other artists, he belonged ...

, did not paint this species and it does not appear to have been transported from Mauritius, they may have read about it or heard about it from the latter's contacts in the court of Emperor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the H ...

(Roelant painted other extinct Mauritian species in the emperor's menagerie).

The British naturalist Hugh Edwin Strickland

Hugh Edwin Strickland (2 March 1811 – 14 September 1853) was an English geologist, ornithology, ornithologist, naturalist and systematist. Through the British Association, he proposed a series of rules for the nomenclature of organisms in zool ...

assigned the "''Indian ravens''" to the hornbill

Hornbills are birds found in tropical and subtropical Africa, Asia and Melanesia of the family Bucerotidae. They are characterized by a long, down-curved bill which is frequently brightly coloured and sometimes has a horny casque on the upper ...

genus '' Buceros'' in 1848, because he interpreted the projection on the forehead in the 1601 illustration as a horn. The Dutch and the French also referred to South American macaw

Macaws are a group of Neotropical parrot, New World parrots that are long-tailed and often colorful, in the Tribe (biology), tribe Arini (tribe), Arini. They are popular in aviculture or as companion parrots, although there are conservation con ...

s as "''Indian ravens''" during the 17th century, and the name was used for hornbills by Dutch, French, and English speakers in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

. The British traveller Sir Thomas Herbert referred to the broad-billed parrot as "''Cacatoes''" (cockatoo

A cockatoo is any of the 21 species of parrots belonging to the family Cacatuidae, the only family in the superfamily Cacatuoidea. Along with the Psittacoidea ( true parrots) and the Strigopoidea (large New Zealand parrots), they make up t ...

) in 1634, with the description "birds like Parrats, fierce and indomitable", but naturalists did not realise that he was referring to the same bird. Even after subfossils of a parrot matching the descriptions were found, the French zoologist

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one ...

Emile Oustalet argued in 1897 that the "''Indian raven''" was a hornbill whose remains awaited discovery. The Mauritian ornithologist France Staub was in favour of this idea as late as 1993. No remains of hornbills have ever been found on the island, and apart from an extinct species from New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

, hornbills are not found on any oceanic island

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

s.

The first known physical remain of the broad-billed parrot was a subfossil mandible collected along with the first batch of dodo bones found in the Mare aux Songes

The Mare aux Songes (English: "pond of taro"; ) swamp is a lagerstätte located close to the sea in south eastern Mauritius. Many subfossils of recently extinct animals have accumulated in the swamp, which was once a lake, and some of the first sub ...

swamp. The British biologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

described the mandible in 1866 and identified it as belonging to a large parrot species, to which he gave the binomial name ''Psittacus

''Psittacus'' is a genus of African grey parrots in the subfamily Psittacinae. It contains two species: the grey parrot (''Psittacus erithacus'') and the Timneh parrot (''Psittacus timneh'').

For many years, the grey parrot and Timneh parrot we ...

mauritianus''. This holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

specimen is now lost. The common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often con ...

"broad-billed parrot" was first used by Owen in a 1866 lecture. In 1868, shortly after the 1601 journal of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

ship ''Gelderland'' had been rediscovered, the German ornithologist Hermann Schlegel

Hermann Schlegel (10 June 1804 – 17 January 1884) was a German ornithologist, herpetologist and ichthyologist.

Early life and education

Schlegel was born at Altenburg, the son of a brassfounder. His father collected butterflies, which stimulated ...

examined an unlabelled pen-and-ink sketch in it. Realising that the drawing, which is attributed to the Dutch artist Joris Joostensz Laerle, depicted the parrot described by Owen, Schlegel made the connection with the old journal descriptions. Because its bones and crest are significantly different from those of ''Psittacus'' species, the British zoologist Alfred Newton

Alfred Newton Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS HFRSE (11 June 18297 June 1907) was an England, English zoologist and ornithologist. Newton was Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge University from 1866 to 1907. Among his numerous public ...

assigned it to its own genus in 1875, which he called ''Lophopsittacus''. ''Lophos'' is the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word for crest, referring here to the bird's frontal crest, and ''psittakos'' means parrot. More fossils were later found by Theodore Sauzier, and described by the British ornithologists Edward Newton and Hans Gadow in 1893. These included previously unknown elements such as the sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

(breast-bone), femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

, metatarsus

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

, and a lower jaw larger than the one that was originally described.

In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway speculated that reports of grey Mauritian parrots referred to the broad-billed parrot. In 1973, based on remains collected by the French amateur naturalist Louis Etienne Thirioux in the early 20th century, the British ornithologist Daniel T. Holyoak placed a small subfossil Mauritian parrot in the same genus as the broad-billed parrot and named it '' Lophopsittacus bensoni''. In 2007, on the basis of a comparison of subfossils, and correlated with old descriptions of small grey parrots, the British

In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway speculated that reports of grey Mauritian parrots referred to the broad-billed parrot. In 1973, based on remains collected by the French amateur naturalist Louis Etienne Thirioux in the early 20th century, the British ornithologist Daniel T. Holyoak placed a small subfossil Mauritian parrot in the same genus as the broad-billed parrot and named it '' Lophopsittacus bensoni''. In 2007, on the basis of a comparison of subfossils, and correlated with old descriptions of small grey parrots, the British palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Julian Hume reclassified it as a species in the genus '' Psittacula'' and called it Thirioux's grey parrot. Hume also reidentified a skull found by Thirioux that was originally assigned to the Rodrigues parrot (''Necropsittacus rodricanus'') as belonging to the broad-billed parrot instead, making it only the second skull known of this species.

Evolution

The taxonomic affinities of the broad-billed parrot are undetermined. Considering its large jaws and other osteological features, Newton and Gadow thought it to be closely related to the Rodrigues parrot in 1893, but were unable to determine whether they both belonged in the same genus, since a crest was only known from the latter. The British ornithologist Graham S. Cowles instead found their skulls too dissimilar for them to be close relatives in 1987. Many endemic Mascarene birds, including the dodo, are derived from South Asian ancestors, and the British ecologist Anthony S. Cheke and Hume have proposed that this may be the case for all the parrots there as well. Sea levels were lower during thePleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, so it was possible for species to colonise some of the then less isolated islands. Although most extinct parrot species of the Mascarenes are poorly known, subfossil remains show that they shared features such as enlarged heads and jaws, reduced pectoral

Pectoral may refer to:

* The chest region and anything relating to it.

* Pectoral cross, a cross worn on the chest

* a decorative, usually jeweled version of a gorget

* Pectoral (Ancient Egypt), a type of jewelry worn in ancient Egypt

* Pectora ...

bones, and robust leg bones. Hume has suggested that they have a common origin in the radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

of the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

Psittaculini, basing this theory on morphological features and the fact that parrots from that group have managed to colonise many isolated islands in the Indian Ocean. The Psittaculini may have invaded the area several times, as many of the species were so specialised that they may have evolved significantly on hotspot islands before the Mascarenes emerged from the sea.

Description

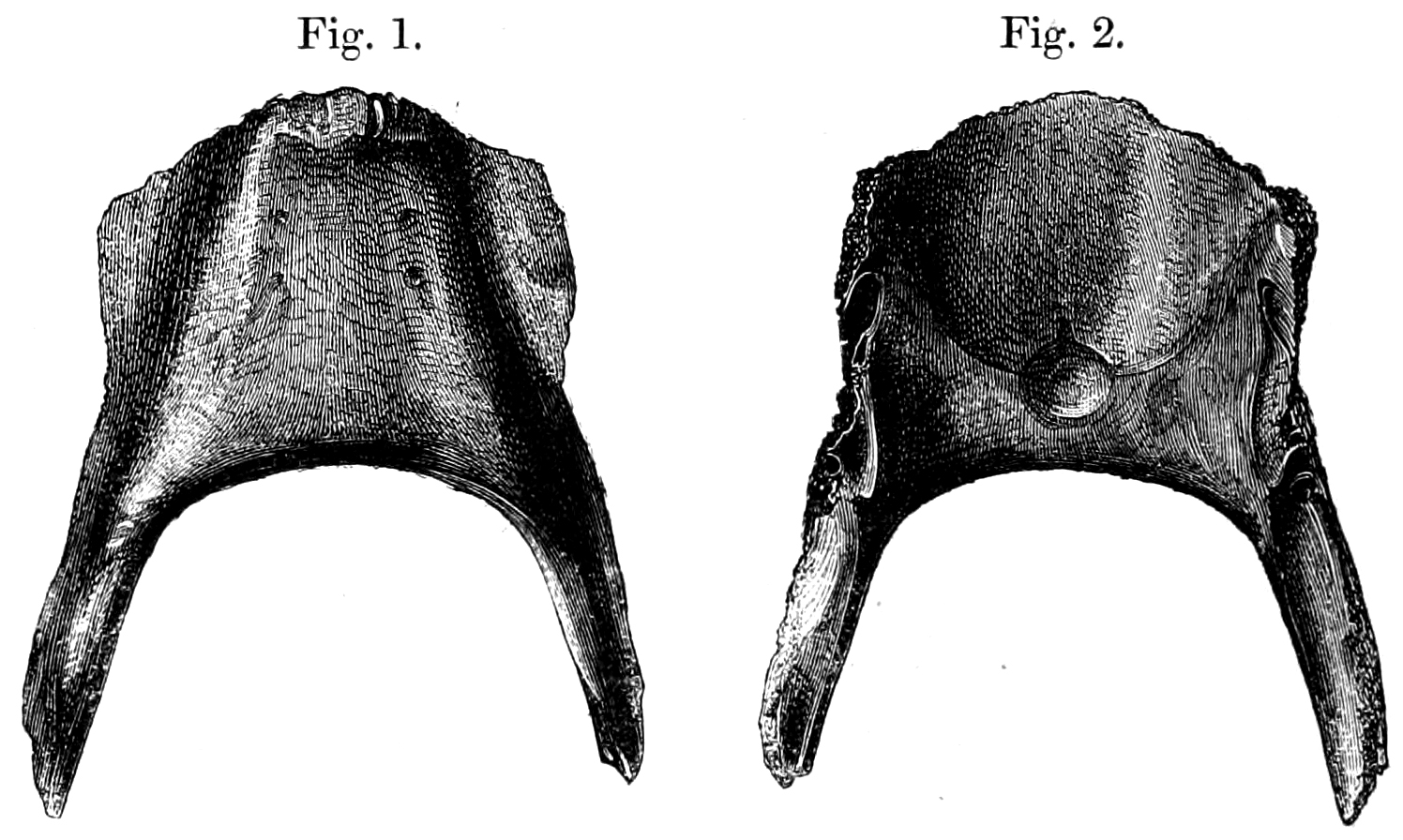

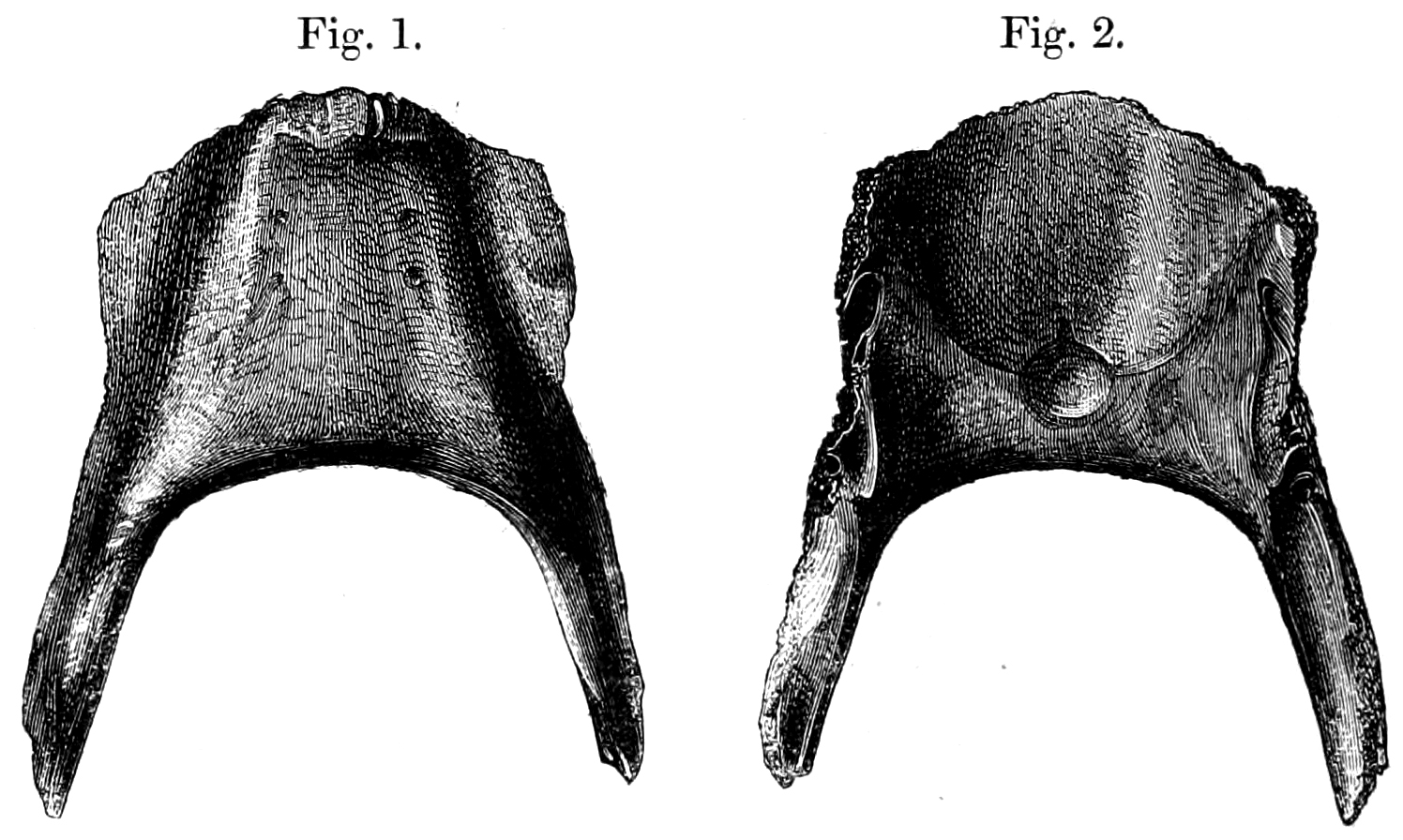

The broad-billed parrot had a disproportionately large head and jaws, and the skull was flattened from top to bottom, unlike in other Mascarene parrots. Ridges on the skull indicate that its distinct frontal crest of feathers was firmly attached, and that the bird, unlike cockatoos, could not raise or lower it. The width of the hind edge of the

The broad-billed parrot had a disproportionately large head and jaws, and the skull was flattened from top to bottom, unlike in other Mascarene parrots. Ridges on the skull indicate that its distinct frontal crest of feathers was firmly attached, and that the bird, unlike cockatoos, could not raise or lower it. The width of the hind edge of the mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral ha ...

(where the two halves of the lower jaw connected) indicate that the jaws were comparatively broad. The 1601 ''Gelderland'' sketch was examined in 2003 by Hume, who compared the ink finish with the underlying pencil sketch and found that the latter showed several additional details. The pencil sketch depicts the crest as a tuft of rounded feathers attached to the front of the head at the base of the beak, and shows rounded wings with long primary covert feathers

A covert feather or tectrix on a bird is one of a set of feathers, called coverts (or ''tectrices''), which cover other feathers. The coverts help to smooth airflow over the wings and tail.

Ear coverts

The ear coverts are small feathers behind t ...

, large secondary feathers

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the Bird wing, wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those ...

, and a slightly bifurcated tail, with the two central feathers longer than the rest. Measurements of some of the first known bones show that the mandible was in length, in width, the femur was in length, the tibia was , and the metatarsus . The sternum was relatively reduced.

Subfossils show that the males were larger, measuring to the females' . The sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in size between male and female skulls is the largest among parrots. Differences in the bones of the rest of the body and limbs are less pronounced; nevertheless, it had greater sexual dimorphism in overall size than any living parrot. The size differences between the two birds in the 1601 sketch may be due to this feature. A 1602 account by the Dutch sailor Reyer Cornelisz has traditionally been interpreted as the only contemporary mention of size differences among broad-billed parrots, listing "large and small ''Indian crows''" among the animals of the island. A full transcript of the original text was only published in 2003, and showed that a comma had been incorrectly placed in the English translation; "large and small" instead referred to "field-hens", possibly the red rail and the smaller Cheke's wood rail.

Possible colouration

There has been some confusion over the colouration of the broad-billed parrot. The report of van Neck's 1598 voyage, published in 1601, contained the first illustration of the parrot, with a caption stating that the bird had "two or three colours". The last account of the bird, and the only mention of specific colours, was by the German preacher Johann Christian Hoffman in 1673–75: In spite of the mention of several colours, authors such as the British naturalist Walter Rothschild claimed that the ''Gelderland'' journal described the bird as entirely blue-grey, and it was restored this way in Rothschild's 1907 book '' Extinct Birds''. Examination of the journal by Hume in 2003 revealed only a description of the dodo. He suggested that the distinctively drawn facial mask may represent a separate colour. Hume suggested in 1987 that in addition to size dimorphism, the sexes may have had different colours, which would explain some of the discrepancies in the old descriptions. The head was evidently blue, and in 2007, Hume suggested the beak may have been red, and the rest of the plumage greyish or blackish, which also occurs in other members of Psittaculini. In 2015, a translation of the 1660s report of the Dutch soldier Johannes Pretorius about his stay on Mauritius (from 1666 to 1669) was published, wherein he described the bird as "very beautifully coloured". Hume accordingly reinterpreted Hoffman's account, and suggested the bird may have been brightly coloured with a red body, blue head, and red beak; the bird was illustrated as such in the paper. Possibleiridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

or glossy feathers that changed appearance according to angle of light may also have given the impression that it had even more colours. The Australian ornithologist Joseph M. Forshaw agreed in 2017 that the bill was red (at least in males), but interpreted Hoffman's account as suggesting a more subdued reddish-brown colouration in general, with a pale bluish-grey head, similar to the Mascarene parrot.

Behaviour and ecology

Pretorius kept various now-extinct Mauritian birds in captivity, and described the behaviour of the broad-billed parrot as follows: Though the broad-billed parrot may have fed on the ground and been a weak flier, itstarsometatarsus

The tarsometatarsus is a bone that is only found in the lower leg of birds and some non-avian dinosaurs. It is formed from the fusion of several bird bones found in other types of animals, and homologous to the mammalian tarsus (ankle bones) a ...

(lower leg bone) was short and stout, implying some arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

(tree-dwelling) characteristics. The Newton brothers and many authors after them inferred that it was flightless

Flightless birds are birds that cannot fly, as they have, through evolution, lost the ability to. There are over 60 extant species, including the well-known ratites ( ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwis) and penguins. The smal ...

, due to the apparent short wings and large size shown in the 1601 ''Gelderland'' sketch. According to Hume, the underlying pencil sketch actually shows that the wings are not particularly short. They appear broad, as they commonly are in forest-adapted species, and the alula

The alula , or bastard wing, (plural ''alulae'') is a small projection on the anterior edge of the wing of modern birds and a few non-avian dinosaurs. The word is Latin and means "winglet"; it is the diminutive of ''ala'', meaning "wing". The a ...

appears large, a feature of slow-flying birds. Its sternal keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

was reduced, but not enough to prevent flight, as the adept flying '' Cyanoramphus'' parrots also have reduced keels, and even the flightless kākāpō

The kākāpō (; : ; ''Strigops habroptilus''), sometimes known as the owl parrot or owl-faced parrot, is a species of large, nocturnal, ground-dwelling parrot of the superfamily Strigopoidea. It is endemic to New Zealand.

Kākāpō can be u ...

, with its vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

keel, is capable of gliding. Furthermore, Hoffman's account states that it could fly, albeit with difficulty, and the first published illustration shows the bird on top of a tree, an improbable position for a flightless bird. The broad-billed parrot may have been behaviourally near-flightless, like the now-extinct Norfolk Island kaka.

Sexual dimorphism in beak size may have affected behaviour. Such dimorphism is common in other parrots, for example in the

Sexual dimorphism in beak size may have affected behaviour. Such dimorphism is common in other parrots, for example in the palm cockatoo

The palm cockatoo (''Probosciger aterrimus''), also known as the goliath cockatoo or great black cockatoo, is a large, smoky-grey/black Psittaciformes, parrot of the cockatoo family native to New Guinea, the Aru Islands Regency, Aru Islands and ...

and the New Zealand kaka. In species where it occurs, the sexes prefer food of different sizes, the males use their beaks in rituals, or the sexes have specialised roles in nesting and rearing. Similarly, the large difference between male and female head size may have been reflected in the ecology of each sex, though it is impossible to determine how.

In 1953, the Japanese ornithologist Masauji Hachisuka

, 18th Marquess Hachisuka, was a Japanese nobleman, ornithologist and aviculturist.Delacour, J. (1953) The Dodo and Kindred Birds by Masauji Hachisuka (Review). The Condor 55 (4): 223.Peterson, A. P. (2013Author Index: Hachisuka, Masauji (Masa U ...

suggested the broad-billed parrot was nocturnal

Nocturnality is a ethology, behavior in some non-human animals characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnality, diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatur ...

, like the kākāpō and the night parrot, two extant ground-dwelling parrots. Contemporary accounts do not corroborate this, and the orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

are of similar size to those of other large diurnal parrots. The broad-billed parrot was recorded on the dry leeward

In geography and seamanship, windward () and leeward () are directions relative to the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e., towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point o ...

side of Mauritius, which was the most accessible for people, and it was noted that birds were more abundant near the coast, which may indicate that the fauna of such areas was more diverse. It may have nested in tree cavities or rocks, like the Cuban amazon. The terms ''raven'' or ''crow'' may have been suggested by the bird's harsh call, its behavioural traits, or just its dark plumage. The following description by the Dutch bookkeeper Jacob Granaet from 1666 mentions some of the broad-billed parrot's co-inhabitants of the forests, and might indicate its demeanour:

Many other endemic species of Mauritius were lost after human colonisation, so the ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

of the island is severely damaged and hard to reconstruct. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was entirely covered in forests, almost all of which have since been lost to deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

. The surviving endemic fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

is still seriously threatened. The broad-billed parrot lived alongside other recently extinct Mauritian birds such as the dodo, the red rail, the Mascarene grey parakeet, the Mauritius blue pigeon, the Mauritius scops owl, the Mascarene coot, the Mauritius sheldgoose, the Mascarene teal, and the Mauritius night heron. Extinct Mauritian reptiles include the saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise, the domed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Mauritian giant skink, and the Round Island burrowing boa. The small Mauritian flying fox and the snail '' Tropidophora carinata'' lived on Mauritius and Réunion but became extinct in both islands. Some plants, such as '' Casearia tinifolia'' and the palm orchid

''Angraecum palmiforme'' is a species of orchid. It existed on Mauritius and Réunion

Réunion (; ; ; known as before 1848) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and regi ...

, have also become extinct.

Diet

Species that are morphologically similar to the broad-billed parrot, such as the

Species that are morphologically similar to the broad-billed parrot, such as the hyacinth macaw

The hyacinth macaw (''Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus''), or hyacinthine macaw, is a parrot native to central and eastern South America. With a length (from the top of its head to the tip of its long pointed tail) of about one meter it is longer tha ...

and the palm cockatoo, may provide insight into its ecology. '' Anodorhynchus'' macaws, which are habitual ground dwellers, eat very hard palm nuts. Many types of palms and palm-like plants on Mauritius produce hard seeds that the broad-billed parrot may have eaten, including '' Latania loddigesii'', '' Mimusops maxima'', '' Sideroxylon grandiflorum'', '' Diospyros egrettorium'', and ''Pandanus utilis

''Pandanus utilis'', the common screwpine is, despite its name, a monocot and not a pine.

It is native to Madagascar and naturalised in Mauritius and the Seychelles.

Description

The trunk features aerial prop roots. The leaves are linear and spi ...

''. The broad-billed parrot and other extinct Mascarene birds, such as the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire could only reach seeds at low heights, and were therefore probably important seed-dispeersers, able to destroy the largest seeds among the Mascarene flora.

On the basis of radiograph

Radiography is an imaging technique using X-rays, gamma rays, or similar ionizing radiation and non-ionizing radiation to view the internal form of an object. Applications of radiography include medical ("diagnostic" radiography and "therapeu ...

s, Holyoak claimed that the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

of the broad-billed parrot was weakly constructed and suggested that it would have fed on soft fruits rather than hard seeds. As evidence, he pointed out that the internal trabeculae

A trabecula (: trabeculae, from Latin for 'small beam') is a small, often microscopic, tissue element in the form of a small beam, strut or rod that supports or anchors a framework of parts within a body or organ. A trabecula generally has a ...

were widely spaced, that the upper bill was broad whereas the palatines

Palatines () were the citizens and princes of the Palatinates, Holy Roman States that served as capitals for the Holy Roman Emperor. After the fall of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the nationality referred more specifically to residents of the ...

were narrow, and the fact that no preserved upper rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

had been discovered, which he attributed to its delicateness. The British ornithologist George A. Smith, however, pointed out that the four genera Holyoak used as examples of "strong jawed" parrots based on radiographs, ''Cyanorhamphus'', '' Melopsittacus'', ''Neophema

The genus ''Neophema'' is an Australian genus with six or seven species. They are small, dull green parrots differentiated by patches of other colours, and are commonly known as grass parrots. The genus has some sexual dichromatism, with males h ...

'' and '' Psephotus'', actually have weak jaws in life, and that the morphologies cited by Holyoak do not indicate strength. Hume pointed out in 2007 that the mandible morphology of the broad-billed parrot is comparable to that of the largest living parrot, the hyacinth macaw, which cracks open palm nuts with ease. It is therefore probable that the broad-billed parrot fed in the same manner.

The Brazilian ornithologist Carlos Yamashita suggested in 1997 that macaws once depended on now-extinct South American

The Brazilian ornithologist Carlos Yamashita suggested in 1997 that macaws once depended on now-extinct South American megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

to eat fruits and excrete the seeds, and that they later relied on domesticated cattle to do this. Similarly, in Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

the palm cockatoo feeds on undigested seeds from cassowary

Cassowaries (; Biak: ''man suar'' ; ; Papuan: ''kasu weri'' ) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'', in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites, flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones. Cassowaries a ...

droppings. Yamashita also suggested that the abundant '' Cylindraspis'' tortoises and dodos performed the same function on Mauritius, and that the broad-billed parrot, with its macaw-like beak, depended on them to obtain cleaned seeds.

Extinction

Though Mauritius had previously been visited byArab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

vessels in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and Portuguese ships between 1507 and 1513, they did not settle on the island. The Dutch Empire acquired the island in 1598, renaming it after the Dutch stadtholder Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange (; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was ''stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death on 23 April 1625. Before he became Prince of Orange upo ...

, and it was used from then on for the provisioning of trade vessels of the Dutch East India Company. To the Dutch sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. Of the eight or so parrot species endemic to the Mascarenes, only the echo parakeet of Mauritius has survived. The others were likely all made extinct by a combination of excessive hunting and deforestation.

Because of its poor flying ability, large size and possible island tameness

Island tameness is the tendency of many populations and species of animals living on isolated islands to lose their wariness of potential predators, particularly of large animals. The term is partly synonymous with ecological naïveté, which als ...

, Hume stated in 2007 the broad-billed parrot was easy prey for sailors who visited Mauritius, and their nests would have been extremely vulnerable to predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

by introduced crab-eating macaque

The crab-eating macaque (''Macaca fascicularis''), also known as the long-tailed macaque or cynomolgus macaque, is a cercopithecine primate native to Southeast Asia. As a synanthropic species, the crab-eating macaque thrives near human settlem ...

s and rats. Various sources indicate the bird was aggressive, which may explain why it held out so long against introduced animals after all. The bird is believed to have become extinct by the 1680s, when the palms it may have sustained itself on were harvested on a large scale. Unlike other parrot species, which were often taken as pets

A pet, or companion animal, is an animal kept primarily for a person's company or entertainment rather than as a working animal, livestock, or a laboratory animal. Popular pets are often considered to have attractive/ cute appearances, int ...

by sailors, there are no records of broad-billed parrots being transported from Mauritius either live or dead, perhaps because of the stigma associated with ravens. The birds would not in any case have survived such a journey if they refused to eat anything but seeds. Cheke pointed out in 2013 that hunting of this species was never reported and that deforestation was minimal at the time. He also suggested that old birds would have survived long after reproduction was possible.

References

External links

* * {{Taxonbar, from=Q93553 Psittacinae Extinct birds of Indian Ocean islands † † Extinct animals of Africa Extinct flightless birds Bird extinctions since 1500 † Birds described in 1866 Extinct animals of Mauritius Species that are or were threatened by invasive species Species made extinct by human activities Taxa with lost type specimens