Brain Volume on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The brain is an

The shape and size of the brain varies greatly between species, and identifying common features is often difficult. Nevertheless, there are a number of principles of brain architecture that apply across a wide range of species. Some aspects of brain structure are common to almost the entire range of animal species; others distinguish "advanced" brains from more primitive ones, or distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates.

The simplest way to gain information about brain anatomy is by visual inspection, but many more sophisticated techniques have been developed. Brain tissue in its natural state is too soft to work with, but it can be hardened by immersion in alcohol or other fixatives, and then sliced apart for examination of the interior. Visually, the interior of the brain consists of areas of so-called

The shape and size of the brain varies greatly between species, and identifying common features is often difficult. Nevertheless, there are a number of principles of brain architecture that apply across a wide range of species. Some aspects of brain structure are common to almost the entire range of animal species; others distinguish "advanced" brains from more primitive ones, or distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates.

The simplest way to gain information about brain anatomy is by visual inspection, but many more sophisticated techniques have been developed. Brain tissue in its natural state is too soft to work with, but it can be hardened by immersion in alcohol or other fixatives, and then sliced apart for examination of the interior. Visually, the interior of the brain consists of areas of so-called

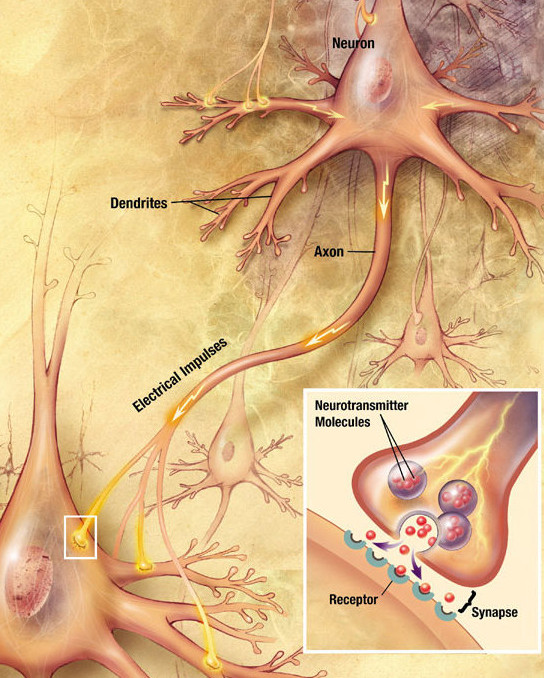

The brains of all species are composed primarily of two broad classes of

The brains of all species are composed primarily of two broad classes of

The brain develops in an intricately orchestrated sequence of stages. It changes in shape from a simple swelling at the front of the nerve cord in the earliest embryonic stages, to a complex array of areas and connections. Neurons are created in special zones that contain stem cells, and then migrate through the tissue to reach their ultimate locations. Once neurons have positioned themselves, their axons sprout and navigate through the brain, branching and extending as they go, until the tips reach their targets and form synaptic connections. In a number of parts of the nervous system, neurons and synapses are produced in excessive numbers during the early stages, and then the unneeded ones are pruned away.

For vertebrates, the early stages of neural development are similar across all species. As the embryo transforms from a round blob of cells into a wormlike structure, a narrow strip of ectoderm running along the midline of the back is cellular differentiation, induced to become the neural plate, the precursor of the nervous system. The neural plate folds inward to form the neural groove, and then the lips that line the groove merge to enclose the

The brain develops in an intricately orchestrated sequence of stages. It changes in shape from a simple swelling at the front of the nerve cord in the earliest embryonic stages, to a complex array of areas and connections. Neurons are created in special zones that contain stem cells, and then migrate through the tissue to reach their ultimate locations. Once neurons have positioned themselves, their axons sprout and navigate through the brain, branching and extending as they go, until the tips reach their targets and form synaptic connections. In a number of parts of the nervous system, neurons and synapses are produced in excessive numbers during the early stages, and then the unneeded ones are pruned away.

For vertebrates, the early stages of neural development are similar across all species. As the embryo transforms from a round blob of cells into a wormlike structure, a narrow strip of ectoderm running along the midline of the back is cellular differentiation, induced to become the neural plate, the precursor of the nervous system. The neural plate folds inward to form the neural groove, and then the lips that line the groove merge to enclose the

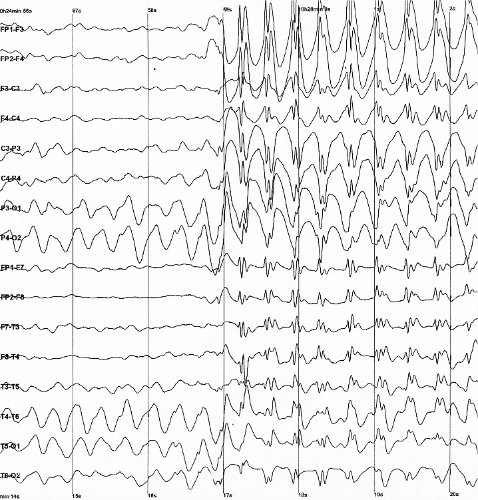

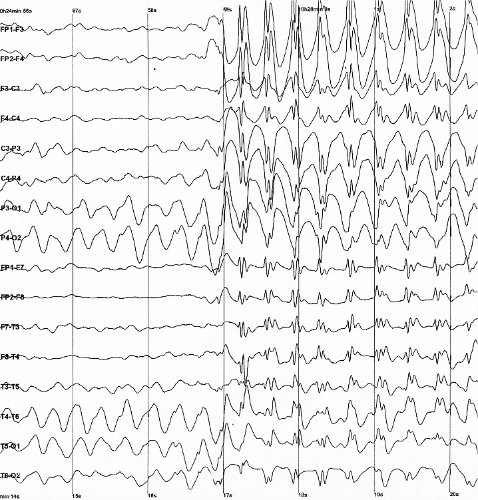

As a side effect of the electrochemical processes used by neurons for signaling, brain tissue generates electric fields when it is active. When large numbers of neurons show synchronized activity, the electric fields that they generate can be large enough to detect outside the skull, using electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG). EEG recordings, along with recordings made from electrodes implanted inside the brains of animals such as rats, show that the brain of a living animal is constantly active, even during sleep. Each part of the brain shows a mixture of rhythmic and nonrhythmic activity, which may vary according to behavioral state. In mammals, the cerebral cortex tends to show large slow delta waves during sleep, faster alpha waves when the animal is awake but inattentive, and chaotic-looking irregular activity when the animal is actively engaged in a task, called Beta wave, beta and gamma waves. During an epilepsy, epileptic seizure, the brain's inhibitory control mechanisms fail to function and electrical activity rises to pathological levels, producing EEG traces that show large wave and spike patterns not seen in a healthy brain. Relating these population-level patterns to the computational functions of individual neurons is a major focus of current research in neurophysiology.

As a side effect of the electrochemical processes used by neurons for signaling, brain tissue generates electric fields when it is active. When large numbers of neurons show synchronized activity, the electric fields that they generate can be large enough to detect outside the skull, using electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG). EEG recordings, along with recordings made from electrodes implanted inside the brains of animals such as rats, show that the brain of a living animal is constantly active, even during sleep. Each part of the brain shows a mixture of rhythmic and nonrhythmic activity, which may vary according to behavioral state. In mammals, the cerebral cortex tends to show large slow delta waves during sleep, faster alpha waves when the animal is awake but inattentive, and chaotic-looking irregular activity when the animal is actively engaged in a task, called Beta wave, beta and gamma waves. During an epilepsy, epileptic seizure, the brain's inhibitory control mechanisms fail to function and electrical activity rises to pathological levels, producing EEG traces that show large wave and spike patterns not seen in a healthy brain. Relating these population-level patterns to the computational functions of individual neurons is a major focus of current research in neurophysiology.

Information from the sense organs is collected in the brain. There it is used to determine what actions the organism is to take. The brain multisensory integration, processes the raw data to extract information about the structure of the environment. Next it combines the processed information with information about the current needs of the animal and with memory of past circumstances. Finally, on the basis of the results, it generates motor response patterns. These signal-processing tasks require intricate interplay between a variety of functional subsystems.

The function of the brain is to provide coherent control over the actions of an animal. A centralized brain allows groups of muscles to be co-activated in complex patterns; it also allows stimuli impinging on one part of the body to evoke responses in other parts, and it can prevent different parts of the body from acting at cross-purposes to each other.

Information from the sense organs is collected in the brain. There it is used to determine what actions the organism is to take. The brain multisensory integration, processes the raw data to extract information about the structure of the environment. Next it combines the processed information with information about the current needs of the animal and with memory of past circumstances. Finally, on the basis of the results, it generates motor response patterns. These signal-processing tasks require intricate interplay between a variety of functional subsystems.

The function of the brain is to provide coherent control over the actions of an animal. A centralized brain allows groups of muscles to be co-activated in complex patterns; it also allows stimuli impinging on one part of the body to evoke responses in other parts, and it can prevent different parts of the body from acting at cross-purposes to each other.

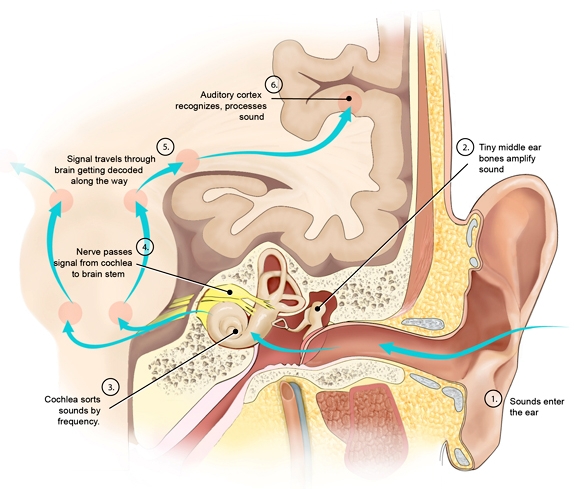

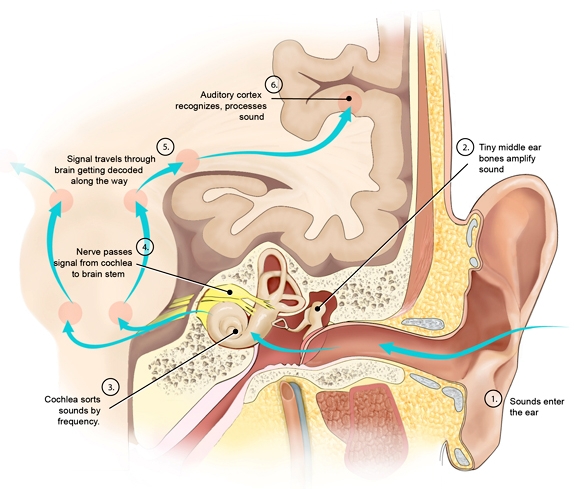

The human brain is provided with information about light, sound, the chemical composition of the atmosphere, temperature, the position of the body in space (proprioception), the chemical composition of the bloodstream, and more. In other animals additional senses are present, such as the Infrared sensing in snakes, infrared heat-sense of snakes, the Magnetoception, magnetic field sense of some birds, or the Electroreception, electric field sense mainly seen in aquatic animals.

Each sensory system begins with specialized receptor cells, such as photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye, or vibration-sensitive hair cells in the cochlea of the ear. The axons of sensory receptor cells travel into the spinal cord or brain, where they transmit their signals to a sensory system, first-order sensory nucleus dedicated to one specific Stimulus modality, sensory modality. This primary sensory nucleus sends information to higher-order sensory areas that are dedicated to the same modality. Eventually, via a way-station in the

The human brain is provided with information about light, sound, the chemical composition of the atmosphere, temperature, the position of the body in space (proprioception), the chemical composition of the bloodstream, and more. In other animals additional senses are present, such as the Infrared sensing in snakes, infrared heat-sense of snakes, the Magnetoception, magnetic field sense of some birds, or the Electroreception, electric field sense mainly seen in aquatic animals.

Each sensory system begins with specialized receptor cells, such as photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye, or vibration-sensitive hair cells in the cochlea of the ear. The axons of sensory receptor cells travel into the spinal cord or brain, where they transmit their signals to a sensory system, first-order sensory nucleus dedicated to one specific Stimulus modality, sensory modality. This primary sensory nucleus sends information to higher-order sensory areas that are dedicated to the same modality. Eventually, via a way-station in the

For any animal, survival requires maintaining a variety of parameters of bodily state within a limited range of variation: these include temperature, water content, salt concentration in the bloodstream, blood glucose levels, blood oxygen level, and others. The ability of an animal to regulate the internal environment of its body—the milieu intérieur, as the pioneering physiologist Claude Bernard called it—is known as homeostasis (Ancient Greek, Greek for "standing still"). Maintaining homeostasis is a crucial function of the brain. The basic principle that underlies homeostasis is negative feedback: any time a parameter diverges from its set-point, sensors generate an error signal that evokes a response that causes the parameter to shift back toward its optimum value. (This principle is widely used in engineering, for example in the control of temperature using a thermostat.)

In vertebrates, the part of the brain that plays the greatest role is the

For any animal, survival requires maintaining a variety of parameters of bodily state within a limited range of variation: these include temperature, water content, salt concentration in the bloodstream, blood glucose levels, blood oxygen level, and others. The ability of an animal to regulate the internal environment of its body—the milieu intérieur, as the pioneering physiologist Claude Bernard called it—is known as homeostasis (Ancient Greek, Greek for "standing still"). Maintaining homeostasis is a crucial function of the brain. The basic principle that underlies homeostasis is negative feedback: any time a parameter diverges from its set-point, sensors generate an error signal that evokes a response that causes the parameter to shift back toward its optimum value. (This principle is widely used in engineering, for example in the control of temperature using a thermostat.)

In vertebrates, the part of the brain that plays the greatest role is the

The individual animals need to express survival-promoting behaviors, such as seeking food, water, shelter, and a mate. The motivational system in the brain monitors the current state of satisfaction of these goals, and activates behaviors to meet any needs that arise. The motivational system works largely by a reward–punishment mechanism. When a particular behavior is followed by favorable consequences, the reward system, reward mechanism in the brain is activated, which induces structural changes inside the brain that cause the same behavior to be repeated later, whenever a similar situation arises. Conversely, when a behavior is followed by unfavorable consequences, the brain's punishment mechanism is activated, inducing structural changes that cause the behavior to be suppressed when similar situations arise in the future.

Most organisms studied to date use a reward–punishment mechanism: for instance, worms and insects can alter their behavior to seek food sources or to avoid dangers. In vertebrates, the reward-punishment system is implemented by a specific set of brain structures, at the heart of which lie the basal ganglia, a set of interconnected areas at the base of the forebrain. The basal ganglia are the central site at which decisions are made: the basal ganglia exert a sustained inhibitory control over most of the motor systems in the brain; when this inhibition is released, a motor system is permitted to execute the action it is programmed to carry out. Rewards and punishments function by altering the relationship between the inputs that the basal ganglia receive and the decision-signals that are emitted. The reward mechanism is better understood than the punishment mechanism, because its role in drug abuse has caused it to be studied very intensively. Research has shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a central role: addictive drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, and nicotine either cause dopamine levels to rise or cause the effects of dopamine inside the brain to be enhanced.

The individual animals need to express survival-promoting behaviors, such as seeking food, water, shelter, and a mate. The motivational system in the brain monitors the current state of satisfaction of these goals, and activates behaviors to meet any needs that arise. The motivational system works largely by a reward–punishment mechanism. When a particular behavior is followed by favorable consequences, the reward system, reward mechanism in the brain is activated, which induces structural changes inside the brain that cause the same behavior to be repeated later, whenever a similar situation arises. Conversely, when a behavior is followed by unfavorable consequences, the brain's punishment mechanism is activated, inducing structural changes that cause the behavior to be suppressed when similar situations arise in the future.

Most organisms studied to date use a reward–punishment mechanism: for instance, worms and insects can alter their behavior to seek food sources or to avoid dangers. In vertebrates, the reward-punishment system is implemented by a specific set of brain structures, at the heart of which lie the basal ganglia, a set of interconnected areas at the base of the forebrain. The basal ganglia are the central site at which decisions are made: the basal ganglia exert a sustained inhibitory control over most of the motor systems in the brain; when this inhibition is released, a motor system is permitted to execute the action it is programmed to carry out. Rewards and punishments function by altering the relationship between the inputs that the basal ganglia receive and the decision-signals that are emitted. The reward mechanism is better understood than the punishment mechanism, because its role in drug abuse has caused it to be studied very intensively. Research has shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a central role: addictive drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, and nicotine either cause dopamine levels to rise or cause the effects of dopamine inside the brain to be enhanced.

The field of neuroscience encompasses all approaches that seek to understand the brain and the rest of the nervous system. Psychology seeks to understand mind and behavior, and neurology is the medical discipline that diagnoses and treats diseases of the nervous system. The brain is also the most important organ studied in psychiatry, the branch of medicine that works to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders. Cognitive science seeks to unify neuroscience and psychology with other fields that concern themselves with the brain, such as computer science (artificial intelligence and similar fields) and philosophy.

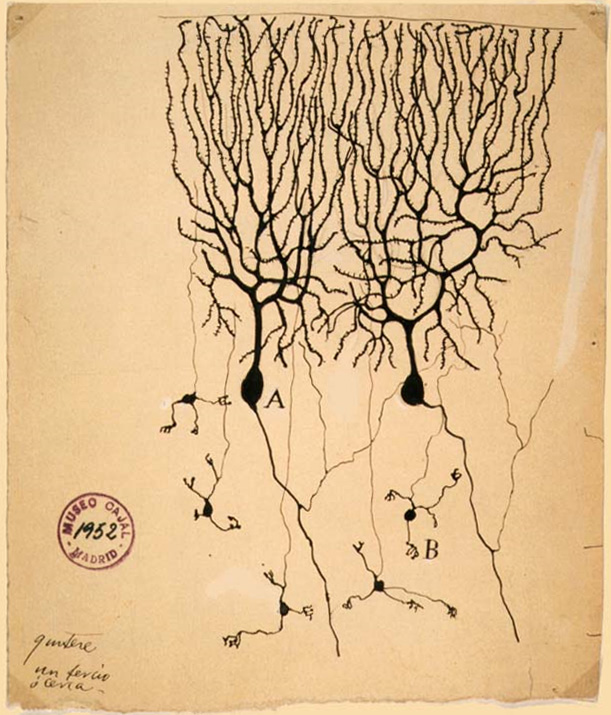

The oldest method of studying the brain is Neuroanatomy, anatomical, and until the middle of the 20th century, much of the progress in neuroscience came from the development of better cell stains and better microscopes. Neuroanatomists study the large-scale structure of the brain as well as the microscopic structure of neurons and their components, especially synapses. Among other tools, they employ a plethora of stains that reveal neural structure, chemistry, and connectivity. In recent years, the development of immunostaining techniques has allowed investigation of neurons that express specific sets of genes. Also, ''functional neuroanatomy'' uses medical imaging techniques to correlate variations in human brain structure with differences in cognition or behavior.

Neurophysiologists study the chemical, pharmacological, and electrical properties of the brain: their primary tools are drugs and recording devices. Thousands of experimentally developed drugs affect the nervous system, some in highly specific ways. Recordings of brain activity can be made using electrodes, either glued to the scalp as in electroencephalography, EEG studies, or implanted inside the brains of animals for extracellular recordings, which can detect action potentials generated by individual neurons. Because the brain does not contain pain receptors, it is possible using these techniques to record brain activity from animals that are awake and behaving without causing distress. The same techniques have occasionally been used to study brain activity in human patients with intractable epilepsy, in cases where there was a medical necessity to implant electrodes to localize the brain area responsible for epileptic seizures. Functional imaging techniques such as Functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI are also used to study brain activity; these techniques have mainly been used with human subjects, because they require a conscious subject to remain motionless for long periods of time, but they have the great advantage of being noninvasive.

Another approach to brain function is to examine the consequences of Brain damage, damage to specific brain areas. Even though it is protected by the skull and

The field of neuroscience encompasses all approaches that seek to understand the brain and the rest of the nervous system. Psychology seeks to understand mind and behavior, and neurology is the medical discipline that diagnoses and treats diseases of the nervous system. The brain is also the most important organ studied in psychiatry, the branch of medicine that works to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders. Cognitive science seeks to unify neuroscience and psychology with other fields that concern themselves with the brain, such as computer science (artificial intelligence and similar fields) and philosophy.

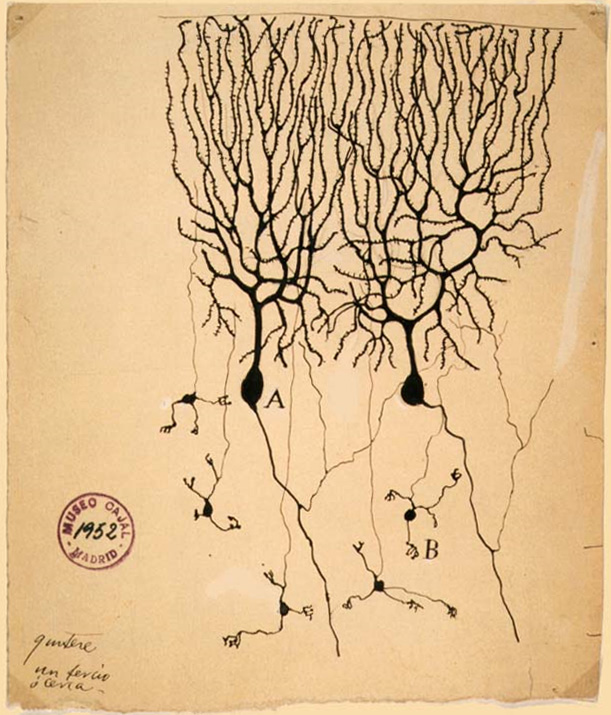

The oldest method of studying the brain is Neuroanatomy, anatomical, and until the middle of the 20th century, much of the progress in neuroscience came from the development of better cell stains and better microscopes. Neuroanatomists study the large-scale structure of the brain as well as the microscopic structure of neurons and their components, especially synapses. Among other tools, they employ a plethora of stains that reveal neural structure, chemistry, and connectivity. In recent years, the development of immunostaining techniques has allowed investigation of neurons that express specific sets of genes. Also, ''functional neuroanatomy'' uses medical imaging techniques to correlate variations in human brain structure with differences in cognition or behavior.

Neurophysiologists study the chemical, pharmacological, and electrical properties of the brain: their primary tools are drugs and recording devices. Thousands of experimentally developed drugs affect the nervous system, some in highly specific ways. Recordings of brain activity can be made using electrodes, either glued to the scalp as in electroencephalography, EEG studies, or implanted inside the brains of animals for extracellular recordings, which can detect action potentials generated by individual neurons. Because the brain does not contain pain receptors, it is possible using these techniques to record brain activity from animals that are awake and behaving without causing distress. The same techniques have occasionally been used to study brain activity in human patients with intractable epilepsy, in cases where there was a medical necessity to implant electrodes to localize the brain area responsible for epileptic seizures. Functional imaging techniques such as Functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI are also used to study brain activity; these techniques have mainly been used with human subjects, because they require a conscious subject to remain motionless for long periods of time, but they have the great advantage of being noninvasive.

Another approach to brain function is to examine the consequences of Brain damage, damage to specific brain areas. Even though it is protected by the skull and

The oldest brain to have been discovered was in Armenia in the Areni-1 cave complex. The brain, estimated to be over 5,000 years old, was found in the skull of a 12 to 14-year-old girl. Although the brains were shriveled, they were well preserved due to the climate found inside the cave.

Early philosophers were divided as to whether the seat of the soul lies in the brain or heart. Aristotle favored the heart, and thought that the function of the brain was merely to cool the blood. Democritus, the inventor of the atomic theory of matter, argued for a three-part soul, with intellect in the head, emotion in the heart, and lust near the liver. The unknown author of ''On the Sacred Disease'', a medical treatise in the Hippocratic Corpus, came down unequivocally in favor of the brain, writing:

The Roman physician Galen also argued for the importance of the brain, and theorized in some depth about how it might work. Galen traced out the anatomical relationships among brain, nerves, and muscles, demonstrating that all muscles in the body are connected to the brain through a branching network of nerves. He postulated that nerves activate muscles mechanically by carrying a mysterious substance he called ''pneumata psychikon'', usually translated as "animal spirits". Galen's ideas were widely known during the Middle Ages, but not much further progress came until the Renaissance, when detailed anatomical study resumed, combined with the theoretical speculations of René Descartes and those who followed him. Descartes, like Galen, thought of the nervous system in hydraulic terms. He believed that the highest cognitive functions are carried out by a non-physical ''res cogitans'', but that the majority of behaviors of humans, and all behaviors of animals, could be explained mechanistically.

The first real progress toward a modern understanding of nervous function, though, came from the investigations of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798), who discovered that a shock of static electricity applied to an exposed nerve of a dead frog could cause its leg to contract. Since that time, each major advance in understanding has followed more or less directly from the development of a new technique of investigation. Until the early years of the 20th century, the most important advances were derived from new methods for staining cells. Particularly critical was the invention of the Golgi's method, Golgi stain, which (when correctly used) stains only a small fraction of neurons, but stains them in their entirety, including cell body, dendrites, and axon. Without such a stain, brain tissue under a microscope appears as an impenetrable tangle of protoplasmic fibers, in which it is impossible to determine any structure. In the hands of Camillo Golgi, and especially of the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the new stain revealed hundreds of distinct types of neurons, each with its own unique dendritic structure and pattern of connectivity.

The oldest brain to have been discovered was in Armenia in the Areni-1 cave complex. The brain, estimated to be over 5,000 years old, was found in the skull of a 12 to 14-year-old girl. Although the brains were shriveled, they were well preserved due to the climate found inside the cave.

Early philosophers were divided as to whether the seat of the soul lies in the brain or heart. Aristotle favored the heart, and thought that the function of the brain was merely to cool the blood. Democritus, the inventor of the atomic theory of matter, argued for a three-part soul, with intellect in the head, emotion in the heart, and lust near the liver. The unknown author of ''On the Sacred Disease'', a medical treatise in the Hippocratic Corpus, came down unequivocally in favor of the brain, writing:

The Roman physician Galen also argued for the importance of the brain, and theorized in some depth about how it might work. Galen traced out the anatomical relationships among brain, nerves, and muscles, demonstrating that all muscles in the body are connected to the brain through a branching network of nerves. He postulated that nerves activate muscles mechanically by carrying a mysterious substance he called ''pneumata psychikon'', usually translated as "animal spirits". Galen's ideas were widely known during the Middle Ages, but not much further progress came until the Renaissance, when detailed anatomical study resumed, combined with the theoretical speculations of René Descartes and those who followed him. Descartes, like Galen, thought of the nervous system in hydraulic terms. He believed that the highest cognitive functions are carried out by a non-physical ''res cogitans'', but that the majority of behaviors of humans, and all behaviors of animals, could be explained mechanistically.

The first real progress toward a modern understanding of nervous function, though, came from the investigations of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798), who discovered that a shock of static electricity applied to an exposed nerve of a dead frog could cause its leg to contract. Since that time, each major advance in understanding has followed more or less directly from the development of a new technique of investigation. Until the early years of the 20th century, the most important advances were derived from new methods for staining cells. Particularly critical was the invention of the Golgi's method, Golgi stain, which (when correctly used) stains only a small fraction of neurons, but stains them in their entirety, including cell body, dendrites, and axon. Without such a stain, brain tissue under a microscope appears as an impenetrable tangle of protoplasmic fibers, in which it is impossible to determine any structure. In the hands of Camillo Golgi, and especially of the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the new stain revealed hundreds of distinct types of neurons, each with its own unique dendritic structure and pattern of connectivity.

In the first half of the 20th century, advances in electronics enabled investigation of the electrical properties of nerve cells, culminating in work by Alan Lloyd Hodgkin, Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley, and others on the biophysics of the action potential, and the work of Bernard Katz and others on the electrochemistry of the synapse. These studies complemented the anatomical picture with a conception of the brain as a dynamic entity. Reflecting the new understanding, in 1942 Charles Scott Sherrington, Charles Sherrington visualized the workings of the brain waking from sleep:

The invention of electronic computers in the 1940s, along with the development of mathematical information theory, led to a realization that brains can potentially be understood as information processing systems. This concept formed the basis of the field of cybernetics, and eventually gave rise to the field now known as computational neuroscience. The earliest attempts at cybernetics were somewhat crude in that they treated the brain as essentially a digital computer in disguise, as for example in John von Neumann's 1958 book, ''The Computer and the Brain''. Over the years, though, accumulating information about the electrical responses of brain cells recorded from behaving animals has steadily moved theoretical concepts in the direction of increasing realism.

One of the most influential early contributions was a 1959 paper titled ''What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain'': the paper examined the visual responses of neurons in the retina and

In the first half of the 20th century, advances in electronics enabled investigation of the electrical properties of nerve cells, culminating in work by Alan Lloyd Hodgkin, Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley, and others on the biophysics of the action potential, and the work of Bernard Katz and others on the electrochemistry of the synapse. These studies complemented the anatomical picture with a conception of the brain as a dynamic entity. Reflecting the new understanding, in 1942 Charles Scott Sherrington, Charles Sherrington visualized the workings of the brain waking from sleep:

The invention of electronic computers in the 1940s, along with the development of mathematical information theory, led to a realization that brains can potentially be understood as information processing systems. This concept formed the basis of the field of cybernetics, and eventually gave rise to the field now known as computational neuroscience. The earliest attempts at cybernetics were somewhat crude in that they treated the brain as essentially a digital computer in disguise, as for example in John von Neumann's 1958 book, ''The Computer and the Brain''. Over the years, though, accumulating information about the electrical responses of brain cells recorded from behaving animals has steadily moved theoretical concepts in the direction of increasing realism.

One of the most influential early contributions was a 1959 paper titled ''What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain'': the paper examined the visual responses of neurons in the retina and

Animal brains are used as food in numerous cuisines.

Animal brains are used as food in numerous cuisines.

The Brain from Top to Bottom

at McGill University

"The Brain"

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Vivian Nutton, Jonathan Sawday & Marina Wallace (''In Our Time (radio series), In Our Time'', May 8, 2008)

Our Quest to Understand the Brain – with Matthew Cobb

Royal Institution lecture. Archived a

Ghostarchive

{{Authority control Brain, Animal anatomy Human anatomy by organ Organs (anatomy)

organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

that serves as the center of the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

in all vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

and most invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s. It consists of nervous tissue

Nervous tissue, also called neural tissue, is the main tissue component of the nervous system. The nervous system regulates and controls body functions and activity. It consists of two parts: the central nervous system (CNS) comprising the brain ...

and is typically located in the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

(cephalization

Cephalization is an evolutionary trend in animals that, over a sufficient number of generations, concentrates the special sense organ (biology), organs and nerve ganglia towards the front of the body where the mouth is located, often producing a ...

), usually near organs for special senses

In medicine and anatomy, the special senses are the senses that have specialized organs devoted to them:

* vision (the eye)

* hearing and balance (the ear, which includes the auditory system and vestibular system)

* smell (the nose)

* taste (th ...

such as vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain und ...

, hearing

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory sci ...

, and olfaction

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

. Being the most specialized organ, it is responsible for receiving information

Information is an Abstraction, abstract concept that refers to something which has the power Communication, to inform. At the most fundamental level, it pertains to the Interpretation (philosophy), interpretation (perhaps Interpretation (log ...

from the sensory nervous system

The sensory nervous system is a part of the nervous system responsible for processing sense, sensory information. A sensory system consists of sensory neurons (including the sensory receptor cells), neural pathways, and parts of the brain invol ...

, processing that information (thought

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, and de ...

, cognition

Cognition is the "mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

, and intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

) and the coordination of motor control

Motor control is the regulation of movements in organisms that possess a nervous system. Motor control includes conscious voluntary movements, subconscious muscle memory and involuntary reflexes, as well as instinctual taxes.

To control ...

(muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

activity and endocrine system

The endocrine system is a messenger system in an organism comprising feedback loops of hormones that are released by internal glands directly into the circulatory system and that target and regulate distant Organ (biology), organs. In vertebrat ...

).

While invertebrate brains arise from paired segmental ganglia

The segmental ganglia (singular: s. ganglion) are ganglia of the annelid and arthropod central nervous system that lie in the segmented ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous syste ...

(each of which is only responsible for the respective body segment

Segmentation in biology is the division of some animal and plant body plans into a linear series of repetitive segments that may or may not be interconnected to each other. This article focuses on the segmentation of animal body plans, specifica ...

) of the ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous system. It is the functional equivalent of the vertebrate spinal cord. The ventral nerve cord coordinates neural signaling from the brain to the body and vice ve ...

, vertebrate brains develop axially from the midline dorsal nerve cord

The dorsal nerve cord is an anatomical feature found in chordate animals, mainly in the subphyla Vertebrata and Cephalochordata, as well as in some hemichordates. It is one of the five embryonic features unique to all chordates, the other fo ...

as a vesicular enlargement at the rostral

Rostral may refer to:

Anatomy

* Rostral (anatomical term), situated toward the oral or nasal region

* Rostral bone, in ceratopsian dinosaurs

* Rostral organ, of certain fish

* Rostral scale

The rostral scale, or rostral, in snakes and other sca ...

end of the neural tube

In the developing chordate (including vertebrates), the neural tube is the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. The neural groove gradually deepens as the neural folds become elevated, ...

, with centralize

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

d control over all body segments. All vertebrate brains can be embryonically divided into three parts: the forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain controls body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and the display of emotions.

Ve ...

(prosencephalon, subdivided into telencephalon

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olf ...

and diencephalon

In the human brain, the diencephalon (or interbrain) is a division of the forebrain (embryonic ''prosencephalon''). It is situated between the telencephalon and the midbrain (embryonic ''mesencephalon''). The diencephalon has also been known as t ...

), midbrain

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the uppermost portion of the brainstem connecting the diencephalon and cerebrum with the pons. It consists of the cerebral peduncles, tegmentum, and tectum.

It is functionally associated with vision, hearing, mo ...

(mesencephalon

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the uppermost portion of the brainstem connecting the diencephalon and cerebrum with the pons. It consists of the cerebral peduncles, tegmentum, and tectum.

It is functionally associated with vision, hearing, mo ...

) and hindbrain

The hindbrain, rhombencephalon (shaped like a rhombus) is a developmental categorization of portions of the central nervous system in vertebrates. It includes the medulla, pons, and cerebellum. Together they support vital bodily processes.

Met ...

(rhombencephalon

The hindbrain, rhombencephalon (shaped like a rhombus) is a developmental categorization of portions of the central nervous system in vertebrates. It includes the medulla, pons, and cerebellum. Together they support vital bodily processes.

Met ...

, subdivided into metencephalon

The metencephalon is the embryonic part of the hindbrain that differentiates into the pons and the cerebellum. It contains a portion of the fourth ventricle and the trigeminal nerve (CN V), abducens nerve (CN VI), facial nerve (CN VII), an ...

and myelencephalon

The myelencephalon or afterbrain is the most posterior region of the embryonic hindbrain, from which the medulla oblongata develops.

Myelencephalon is from myel- (bone marrow or spinal cord) and encephalon (the vertebrate brain).

Development

...

). The spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, which directly interacts with somatic functions below the head, can be considered a caudal extension of the myelencephalon enclosed inside the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

. Together, the brain and spinal cord constitute the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

in all vertebrates.

In human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s, the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. It is the largest site of Neuron, neural integration in the central nervous system, and plays ...

contains approximately 14–16 billion neurons, and the estimated number of neurons in the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

is 55–70 billion. Each neuron is connected by synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s to several thousand other neurons, typically communicating with one another via cytoplasmic process

Cellular extensions also known as cytoplasmic protrusions and cytoplasmic processes are those structures that project from different cells, in the body, or in other organisms. Many of the extensions are cytoplasmic protrusions such as the axon an ...

es known as dendrite

A dendrite (from Ancient Greek language, Greek δένδρον ''déndron'', "tree") or dendron is a branched cytoplasmic process that extends from a nerve cell that propagates the neurotransmission, electrochemical stimulation received from oth ...

s and axon

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis) or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, spelling differences) is a long, slender cellular extensions, projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, ...

s. Axons are usually myelinated

Myelin Sheath ( ) is a lipid-rich material that in most vertebrates surrounds the axons of neurons to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) pass along the axon. The myelinated axon can be lik ...

and carry trains of rapid micro-electric signal pulses called action potential

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific Cell (biology), cell rapidly ri ...

s to target specific recipient cells in other areas of the brain or distant parts of the body. The prefrontal cortex

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, ...

, which controls executive function

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions (collectively referred to as executive function and cognitive control) are a set of cognitive processes that support goal-directed behavior, by regulating thoughts and actions thro ...

s, is particularly well developed in humans.

Physiologically, brains exert centralized control over a body's other organs. They act on the rest of the body both by generating patterns of muscle activity and by driving the secretion of chemicals called hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of cell signaling, signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physio ...

s. This centralized control allows rapid and coordinated responses to changes in the environment. Some basic types of responsiveness such as reflex

In biology, a reflex, or reflex action, is an involuntary, unplanned sequence or action and nearly instantaneous response to a stimulus.

Reflexes are found with varying levels of complexity in organisms with a nervous system. A reflex occurs ...

es can be mediated by the spinal cord or peripheral ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

, but sophisticated purposeful control of behavior based on complex sensory input requires the information integrating capabilities of a centralized brain.

The operations of individual brain cells are now understood in considerable detail but the way they cooperate in ensembles of millions is yet to be solved. Recent models in modern neuroscience treat the brain as a biological computer, very different in mechanism from a digital computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as ''programs'', wh ...

, but similar in the sense that it acquires information from the surrounding world, stores it, and processes it in a variety of ways.

This article compares the properties of brains across the entire range of animal species, with the greatest attention to vertebrates. It deals with the human brain

The human brain is the central organ (anatomy), organ of the nervous system, and with the spinal cord, comprises the central nervous system. It consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. The brain controls most of the activi ...

insofar as it shares the properties of other brains. The ways in which the human brain differs from other brains are covered in the human brain article. Several topics that might be covered here are instead covered there because much more can be said about them in a human context. The most important that are covered in the human brain article are brain disease

Central nervous system diseases or central nervous system disorders are a group of neurological disorders that affect the structure or function of the human brain, brain or spinal cord, which collectively form the central nervous system (CNS). Th ...

and the effects of brain damage

Brain injury (BI) is the destruction or degeneration of brain cells. Brain injuries occur due to a wide range of internal and external factors. In general, brain damage refers to significant, undiscriminating trauma-induced damage.

A common ...

.

Structure

The shape and size of the brain varies greatly between species, and identifying common features is often difficult. Nevertheless, there are a number of principles of brain architecture that apply across a wide range of species. Some aspects of brain structure are common to almost the entire range of animal species; others distinguish "advanced" brains from more primitive ones, or distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates.

The simplest way to gain information about brain anatomy is by visual inspection, but many more sophisticated techniques have been developed. Brain tissue in its natural state is too soft to work with, but it can be hardened by immersion in alcohol or other fixatives, and then sliced apart for examination of the interior. Visually, the interior of the brain consists of areas of so-called

The shape and size of the brain varies greatly between species, and identifying common features is often difficult. Nevertheless, there are a number of principles of brain architecture that apply across a wide range of species. Some aspects of brain structure are common to almost the entire range of animal species; others distinguish "advanced" brains from more primitive ones, or distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates.

The simplest way to gain information about brain anatomy is by visual inspection, but many more sophisticated techniques have been developed. Brain tissue in its natural state is too soft to work with, but it can be hardened by immersion in alcohol or other fixatives, and then sliced apart for examination of the interior. Visually, the interior of the brain consists of areas of so-called grey matter

Grey matter, or gray matter in American English, is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil ( dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells ( astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, ...

, with a dark color, separated by areas of white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called Nerve tract, tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distr ...

, with a lighter color. Further information can be gained by staining slices of brain tissue with a variety of chemicals that bring out areas where specific types of molecules are present in high concentrations. It is also possible to examine the microstructure of brain tissue using a microscope, and to trace the pattern of connections from one brain area to another.

Cellular structure

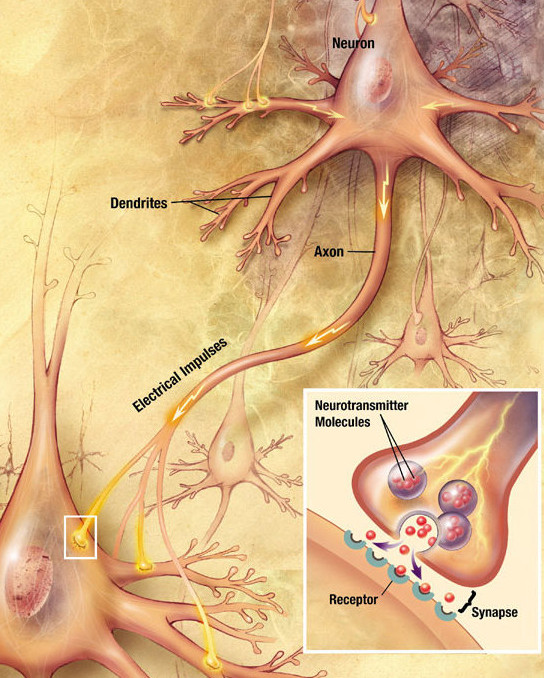

The brains of all species are composed primarily of two broad classes of

The brains of all species are composed primarily of two broad classes of brain cell

Brain cells make up the functional tissue of the brain. The rest of the brain tissue is the structural stroma that includes connective tissue such as the meninges, blood vessels, and ducts. The two main types of cells in the brain are neurons, ...

s: neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s and glial cells

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (the brain and the spinal cord) and in the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. The neuroglia make up ...

. Glial cells (also known as ''glia'' or ''neuroglia'') come in several types, and perform a number of critical functions, including structural support, metabolic support, insulation, and guidance of development. Neurons, however, are usually considered the most important cells in the brain. In humans, the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. It is the largest site of Neuron, neural integration in the central nervous system, and plays ...

contains approximately 14–16 billion neurons, and the estimated number of neurons in the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

is 55–70 billion. Each neuron is connected by synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s to several thousand other neurons. The property that makes neurons unique is their ability to send signals to specific target cells, sometimes over long distances. They send these signals by means of an axon

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis) or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, spelling differences) is a long, slender cellular extensions, projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, ...

, which is a thin protoplasmic fiber that extends from the cell body and projects, usually with numerous branches, to other areas, sometimes nearby, sometimes in distant parts of the brain or body. The length of an axon can be extraordinary: for example, if a pyramidal cell

Pyramidal cells, or pyramidal neurons, are a type of multipolar neuron found in areas of the brain including the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. Pyramidal cells are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cort ...

(an excitatory neuron) of the cerebral cortex were magnified so that its cell body became the size of a human body, its axon, equally magnified, would become a cable a few centimeters in diameter, extending more than a kilometer. These axons transmit signals in the form of electrochemical pulses called action potentials, which last less than a thousandth of a second and travel along the axon at speeds of 1–100 meters per second. Some neurons emit action potentials constantly, at rates of 10–100 per second, usually in irregular patterns; other neurons are quiet most of the time, but occasionally emit a burst of action potentials.

Axons transmit signals to other neurons by means of specialized junctions called synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s. A single axon may make as many as several thousand synaptic connections with other cells. When an action potential, traveling along an axon, arrives at a synapse, it causes a chemical called a neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

to be released. The neurotransmitter binds to receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and respond ...

molecules in the membrane of the target cell.

Synapses are the key functional elements of the brain. The essential function of the brain is cell-to-cell communication, and synapses are the points at which communication occurs. The human brain has been estimated to contain approximately 100 trillion synapses; even the brain of a fruit fly contains several million. The functions of these synapses are very diverse: some are excitatory (exciting the target cell); others are inhibitory; others work by activating second messenger system

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form of cell signaling, encompassing both first me ...

s that change the internal chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

of their target cells in complex ways. A large number of synapses are dynamically modifiable; that is, they are capable of changing strength in a way that is controlled by the patterns of signals that pass through them. It is widely believed that activity-dependent modification of synapses is the brain's primary mechanism for learning and memory.

Most of the space in the brain is taken up by axons, which are often bundled together in what are called ''nerve fiber tracts''. A myelinated axon is wrapped in a fatty insulating sheath of myelin

Myelin Sheath ( ) is a lipid-rich material that in most vertebrates surrounds the axons of neurons to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) pass along the axon. The myelinated axon can be lik ...

, which serves to greatly increase the speed of signal propagation. (There are also unmyelinated axons). Myelin is white, making parts of the brain filled exclusively with nerve fibers appear as light-colored white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called Nerve tract, tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distr ...

, in contrast to the darker-colored grey matter

Grey matter, or gray matter in American English, is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil ( dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells ( astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, ...

that marks areas with high densities of neuron cell bodies.

Evolution

Generic bilaterian nervous system

Except for a few primitive organisms such assponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s (which have no nervous system) and cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns (which have a diffuse nervous system consisting of a nerve net

''Nerve Net'' is the eleventh solo studio album by Brian Eno, released on 1 September 1992 on Opal and Warner Bros. Records. It marked a return to more rock-oriented material, mixed with heavily syncopated rhythms, experimental electronic com ...

), all living multicellular animals are bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

ns, meaning animals with a bilaterally symmetric body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

(that is, left and right sides that are approximate mirror images of each other). All bilaterians are thought to have descended from a common ancestor that appeared late in the Cryogenian

The Cryogenian (from , meaning "cold" and , romanized: , meaning "birth") is a geologic period that lasted from . It is the second of the three periods of the Neoproterozoic era, preceded by the Tonian and followed by the Ediacaran.

The Cryoge ...

period, 700–650 million years ago, and it has been hypothesized that this common ancestor had the shape of a simple tubeworm with a segmented body. At a schematic level, that basic worm-shape continues to be reflected in the body and nervous system architecture of all modern bilaterians, including vertebrates. The fundamental bilateral body form is a tube with a hollow gut cavity running from the mouth to the anus, and a nerve cord with an enlargement (a ganglion

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there are ...

) for each body segment, with an especially large ganglion at the front, called the brain. The brain is small and simple in some species, such as nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

worms; in other species, such as vertebrates, it is a large and very complex organ. Some types of worms, such as leech

Leeches are segmented parasitism, parasitic or Predation, predatory worms that comprise the Class (biology), subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the Oligochaeta, oligochaetes, which include the earthwor ...

es, also have an enlarged ganglion at the back end of the nerve cord, known as a "tail brain".

There are a few types of existing bilaterians that lack a recognizable brain, including echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as ...

s and tunicate

Tunicates are marine invertebrates belonging to the subphylum Tunicata ( ). This grouping is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ...

s. It has not been definitively established whether the existence of these brainless species indicates that the earliest bilaterians

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left–r ...

lacked a brain, or whether their ancestors evolved in a way that led to the disappearance of a previously existing brain structure.

Invertebrates

This category includestardigrade

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who called them . In 1776, th ...

s, arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

, and numerous types of worms. The diversity of invertebrate body plans is matched by an equal diversity in brain structures.

Two groups of invertebrates have notably complex brains: arthropods (insects, crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s, and others), and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s (octopuses, squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

s, and similar molluscs). The brains of arthropods and cephalopods arise from twin parallel nerve cords that extend through the body of the animal. Arthropods have a central brain, the supraesophageal ganglion, with three divisions and large optical lobes behind each eye for visual processing. Cephalopods such as the octopus and squid have the largest brains of any invertebrates.

There are several invertebrate species whose brains have been studied intensively because they have properties that make them convenient for experimental work:

* Fruit flies (''Drosophila''), because of the large array of techniques available for studying their genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

, have been a natural subject for studying the role of genes in brain development. In spite of the large evolutionary distance between insects and mammals, many aspects of ''Drosophila'' neurogenetics

Neurogenetics studies the role of genetics in the development and function of the nervous system. It considers neural characteristics as phenotypes (i.e. manifestations, measurable or not, of the genetic make-up of an individual), and is mainly ba ...

have been shown to be relevant to humans. The first biological clock genes, for example, were identified by examining ''Drosophila'' mutants that showed disrupted daily activity cycles. A search in the genomes of vertebrates revealed a set of analogous genes, which were found to play similar roles in the mouse biological clock—and therefore almost certainly in the human biological clock as well. Studies done on Drosophila, also show that most neuropil

Neuropil (or "neuropile") is any area in the nervous system composed of mostly unmyelinated axons, dendrites and glial cell processes that forms a synaptically dense region containing a relatively low number of cell bodies. The most prevalent ...

regions of the brain are continuously reorganized throughout life in response to specific living conditions.

* The nematode worm ''Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

'', like ''Drosophila'', has been studied largely because of its importance in genetics. In the early 1970s, Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to wo ...

chose it as a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

for studying the way that genes control development. One of the advantages of working with this worm is that the body plan is very stereotyped: the nervous system of the hermaphrodite

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

contains exactly 302 neurons, always in the same places, making identical synaptic connections in every worm. Brenner's team sliced worms into thousands of ultrathin sections and photographed each one under an electron microscope, then visually matched fibers from section to section, to map out every neuron and synapse in the entire body. The complete neuronal ''wiring diagram'' of ''C.elegans'' – its connectome

A connectome () is a comprehensive map of neural connections in the brain, and may be thought of as its " wiring diagram". These maps are available in varying levels of detail. A functional connectome shows connections between various brain ...

was achieved. Nothing approaching this level of detail is available for any other organism, and the information gained has enabled a multitude of studies that would otherwise have not been possible.

* The sea slug ''Aplysia

''Aplysia'' () is a genus of medium-sized to extremely large sea slugs, specifically sea hares, which are a kind of marine gastropod mollusk.

These benthic herbivorous creatures can become rather large compared with most other mollusks. They ...

californica'' was chosen by Nobel Prize-winning neurophysiologist Eric Kandel

Eric Richard Kandel (; born Erich Richard Kandel, November 7, 1929) is an Austrian-born American medical doctor who specialized in psychiatry, a neuroscientist and a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the College of Physicians and Surgeo ...

as a model for studying the cellular basis of learning

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, value (personal and cultural), values, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, non-human animals, and ...

and memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

, because of the simplicity and accessibility of its nervous system, and it has been examined in hundreds of experiments.

Vertebrates

The firstvertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s appeared over 500 million years ago ( Mya) during the Cambrian period

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordovici ...

, and may have resembled the modern jawless fish

Agnatha (; ) or jawless fish is a paraphyletic infraphylum of animals in the subphylum Vertebrata of the phylum Chordata, characterized by the lack of jaws. The group consists of both extant taxon, living (Cyclostomi, cyclostomes such as hagfish ...

(hagfish

Hagfish, of the Class (biology), class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and Order (biology), order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped Agnatha, jawless fish (occasionally called slime eels). Hagfish are the only known living Animal, animals that h ...

and lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are a group of Agnatha, jawless fish comprising the order (biology), order Petromyzontiformes , sole order in the Class (biology), class Petromyzontida. The adult lamprey is characterize ...

) in form. Jawed vertebrate

Gnathostomata (; from Ancient Greek: (') 'jaw' + (') 'mouth') are jawed vertebrates. Gnathostome diversity comprises roughly 60,000 species, which accounts for 99% of all extant vertebrates, including all living bony fishes (both ray-finned ...

s appeared by 445 Mya, tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s by 350 Mya, amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s by 310 Mya and mammaliaform

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a clade of synapsid tetrapods that includes the crown group mammals and their closest extinct relatives; the group radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic. It is defined a ...

s by 200 Mya (approximately). Each vertebrate clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

has an equally long evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary history, but the brains of modern fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s show a gradient of size and complexity that roughly follows the evolutionary sequence. All of these brains contain the same set of basic anatomical structures, but many are rudimentary in the hagfish, whereas in mammals the foremost part (forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain controls body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and the display of emotions.

Ve ...

, especially the telencephalon

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olf ...

) is greatly developed and expanded.

Brains are most commonly compared in terms of their mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

. The relationship between brain size