Bowerchalke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bowerchalke is a village and

Chalke was a comparatively large, disconnected estate that was separated into the two ecclesiastical parishes of Broad Chalk and Bowerchalke in 1880. In 1885, 283 acres were transferred to Bower Chalke from

Chalke was a comparatively large, disconnected estate that was separated into the two ecclesiastical parishes of Broad Chalk and Bowerchalke in 1880. In 1885, 283 acres were transferred to Bower Chalke from

The

The

Bowerchalke

at the

Images of Bowerchalke

at Geograph.com

at Romans in Britain

Bowerchalke at Wiltshire Community History

Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's 1773 map

Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's 1810 map

{{authority control Villages in Wiltshire Bowerchalke inlier Civil parishes in Wiltshire

civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

, England, about southwest of Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

. It is in the south of the county, about from the boundary with Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

and from that with Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

. The parish includes the hamlets of Mead End, Misselfore and Woodminton.

Bowerchalke is in the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs

Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs, marketed as the Cranborne Chase National Landscape, is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) covering of Dorset, Hampshire, Somerset and Wiltshire. It is the sixth largest AONB in England.

The ar ...

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is one of 46 areas of countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Since 2023, the areas in England an ...

, which is part of the Southern England Chalk Formation

Downland, chalkland, chalk downs or just downs are areas of open chalk hills, such as the North Downs. This term is used to describe the characteristic landscape in southern England where chalk is exposed at the surface. The name "downs" is deriv ...

. The River Chalke

The River Chalke is a small river within the English county of Wiltshire. It is the most significant tributary of the River Ebble.

The river rises at Mead End near Bowerchalke and flows 1.2 miles north through the Chalke Valley to join the Ebb ...

, a classic chalk stream

Chalk streams are rivers that rise from springs in landscapes with chalk bedrock. Since chalk is permeable, water easily percolates through the ground to the water table and chalk streams therefore receive little surface runoff. As a result, th ...

, rises in the village and joins the River Ebble

The River Ebble is one of the five rivers of the English city of Salisbury. Rising at Alvediston to the west of the city, it joins the River Avon at Bodenham, near Nunton.

Description

The Ebble rises at Alvediston, to the west of Salisbur ...

at Broad Chalke

Broad Chalke, sometimes spelled Broadchalke, Broad Chalk or Broadchalk, is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about west of the city of Salisbury. The civil parish includes the hamlets of Knapp, Mount Sorrel and Stoke Farthing.

...

, flowing into the Hampshire Avon

The River Avon ( ) is in the south of England, rising in Wiltshire, flowing through that county's city of Salisbury and then west Hampshire, before reaching the English Channel through Christchurch Harbour in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and ...

south of Salisbury.

The Grade II* listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, H ...

church of the Holy Trinity dates from the 13th century, and Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

winning novelist William Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel '' Lord of the Flies'' (1954), Golding published another 12 volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 19 ...

is buried in the churchyard.

History

It is not known when Bowerchalke was first inhabited or what it was called but fragmentary records from Saxon times indicate that the whole Chalke Valley area was thriving, the River Ebble also being known as the River Chalke.Prehistory

The earliest known sign of habitation is thebowl barrow

A bowl barrow is a type of burial mound or tumulus. A barrow is a mound of earth used to cover a tomb. The bowl barrow gets its name from its resemblance to an upturned bowl. Related terms include ''cairn circle'', ''cairn ring'', ''howe'', ''ker ...

on Marleycombe Down, which was probably built in either the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

or the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

(3300–1200 BCE). The Bowerchalke Barrel Urn was excavated here in 1925 by Dr R Clay, and the repaired urn is part of the collection at the Wiltshire Museum

The Wiltshire Museum, formerly known as Wiltshire Heritage Museum and Devizes Museum, is a museum, archive and library and art gallery established in 1874 in Devizes, Wiltshire, England. The museum was created and is run by the Wiltshire Archae ...

, Devizes.

4th century

Two hoards of gold and silver coins and rings from the 4th century were discovered bymetal detector

A metal detector is an instrument that detects the nearby presence of metal. Metal detectors are useful for finding metal objects on the surface, underground, and under water. A metal detector consists of a control box, an adjustable shaft, and ...

ists near Bowerchalke in the 20th and 21st centuries. They were used by the Durotriges

The Durotriges were one of the Celtic tribes living in British Iron Age, Britain prior to the Roman invasion of Britain, Roman invasion. The tribe lived in modern Dorset, south Wiltshire, south Somerset and Devon east of the River Axe (Lyme Bay), ...

, a Celt

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

ic tribe that lived in South Wiltshire and Dorset before the Roman occupation, became Romanised by c.79 and gave their name to Dorset. The first discovery was a hoard of 17 gold stater

The stater (; ) was an ancient coin used in various regions of Greece. The term is also used for similar coins, imitating Greek staters, minted elsewhere in ancient Europe.

History

The stater, as a Greek silver currency, first as ingots, and ...

s (coins), examples of which are now displayed in the Salisbury Museum

The Salisbury Museum (previously The Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum) is a museum in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. It houses one of the best collections relating to Stonehenge and local archaeology.

The museum is housed in The King's Hou ...

. The second hoard of 2 gold rings and 5 silver coin

Silver coins are one of the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Silver has been used as a coinage metal since the times of the Greeks; their silver drachmas were popular trade coins. The ancient Persians used silver coins between 612–330 B ...

s dated to 380 was found in 2002 near the first.

9th century

AnAnglo-Saxon charter

Anglo-Saxon charters are documents from the History of Anglo-Saxon England, early medieval period in England which typically made a grant of Real Estate, land or recorded a Privilege (legal ethics), privilege. The earliest surviving charters were ...

of 826 records the name of the area including Bowerchalke and Broad Chalke as ''Cealcan gemere''.

10th century

In 955 the Anglo-Saxon King Eadwig granted thenuns

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of Evangelical counsels, poverty, chastity, and obedience in the Enclosed religious orders, enclosure of a monastery or convent.' ...

of Wilton Abbey

Wilton Abbey was a Benedictine convent in Wiltshire, England, three miles west of Salisbury, probably on the site now occupied by Wilton House. It was active from the early tenth century until 1539.

History Foundation

Wilton Abbey is first re ...

an estate called Chalke which included land in Broad Chalke and Bowerchalke. The charter records the village name as ''aet Ceolcan''.''Broad Chalke, A History of a South Wiltshire Village, its Land & People Over 2,000 years''. By 'The People of the Village', 1999 A charter in 974 records the name as ''Cheolca'' or ''Cheolcam''.

11th century

TheDomesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

in 1086 divided the Chalke Valley into eight manors, ''Chelke'' or ''Chelce'' or ''Celce'' (Bowerchalke and Broad Chalke

Broad Chalke, sometimes spelled Broadchalke, Broad Chalk or Broadchalk, is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about west of the city of Salisbury. The civil parish includes the hamlets of Knapp, Mount Sorrel and Stoke Farthing.

...

), ''Eblesborne'' (Ebbesbourne Wake

Ebbesbourne Wake or Ebbesborne Wake is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, some south-west of Salisbury, near the head of the valley of the small River Ebble. The parish includes the hamlets of Fifield Bavant and West End. In 201 ...

), ''Fifehide'' (Fifield), ''Cumbe'' (Coombe Bissett

Coombe Bissett is a village and civil parish in the English county of Wiltshire in the River Ebble valley, southwest of Salisbury on the A354 road that goes south towards Blandford Forum. The parish includes the village of Homington, to the e ...

), ''Humitone'' (Homington), ''Odestoche'' (Odstock

Odstock is a village and civil parish south of Salisbury in Wiltshire, England. The parish includes the village of Nunton with its nearby hamlet of Bodenham. The parish is in the valley of the River Ebble, which joins the Hampshire Avon near ...

), ''Stradford'' (Stratford Tony

Stratford Tony, also spelt Stratford Toney, formerly known as Stratford St Anthony and Toney Stratford, is a small village and civil parish in southern Wiltshire, England. It lies on the River Ebble and is about southwest of Salisbury.

and Bishopstone) and ''Trow'' (approximately Alvediston and Tollard Royal

Tollard Royal is a village and civil parish on Cranborne Chase, Wiltshire, England. The parish is on Wiltshire's southern boundary with Dorset and the village is southeast of the Dorset town of Shaftesbury, on the B3081 road between Shaftesbur ...

).

12th century

In the 12th century the area was known primarily as the StowfordHundred

100 or one hundred (Roman numerals, Roman numeral: C) is the natural number following 99 (number), 99 and preceding 101 (number), 101.

In mathematics

100 is the square of 10 (number), 10 (in scientific notation it is written as 102). The standar ...

then subsequently as the Chalke Hundred. This included the parishes of Berwick St John

Berwick St John is a village and civil parish in southwest Wiltshire, England, about east of Shaftesbury in Dorset. The parish includes the Ashcombe Park estate, part of the Ferne Park estate, and most of Rushmore Park (since 1939 the home o ...

, Ebbesbourne Wake

Ebbesbourne Wake or Ebbesborne Wake is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, some south-west of Salisbury, near the head of the valley of the small River Ebble. The parish includes the hamlets of Fifield Bavant and West End. In 201 ...

, Fifield Bavant

Fifield Bavant (/'fʌɪfiːld 'bavənt/) is a small village in the civil parish of Ebbesborne Wake, in Wiltshire, England, about southwest of Wilton, midway between Ebbesbourne Wake and Broad Chalke on the north bank of the River Ebble. Fifiel ...

, Semley

Semley is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Sedgehill and Semley, in Wiltshire, England, about north-east of Shaftesbury in neighbouring Dorset. The hamlet of Sem Hill lies about a quarter of a mile west of the village. I ...

, Tollard Royal

Tollard Royal is a village and civil parish on Cranborne Chase, Wiltshire, England. The parish is on Wiltshire's southern boundary with Dorset and the village is southeast of the Dorset town of Shaftesbury, on the B3081 road between Shaftesbur ...

and 'Chalke'. A charter of 1165 records the village name as ''Chalca'', and the Pipe Rolls

The Pipe rolls, sometimes called the Great rollsBrown ''Governance'' pp. 54–56 or the Great Rolls of the Pipe, are a collection of financial records maintained by the English Exchequer, or Treasury, and its successors, as well as the Exche ...

in 1174 record it as ''Chalche''.

13th century

The Curia Regis Rolls of 1207 records the village name as ''ChelkFeet of Fines'', and another of 1242 records it as ''Chalke''. The name Bower Chalke was apparently given to that part of the Chalke estate where lands were in 'bower hold' tenure. The name ''Burchelke'' first appeared in 1225. The church of the HolyTrinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

dates from this century.

14th century

A Saxon charter of 1304 records the village name as ''Cheolc'' and ''Cheolcan''. The Feudal Aids of 1316 uses ''Chawke'', whilst a SaxonCartulary

A cartulary or chartulary (; Latin: ''cartularium'' or ''chartularium''), also called ''pancarta'' or ''codex diplomaticus'', is a medieval manuscript volume or roll ('' rotulus'') containing transcriptions of original documents relating to the fo ...

of 1321 uses ''Cealce''. The Tax lists of 1327, 1332 and 1377 variously record the name as ''Chalk Magna'' and '' Chalke Magna''. ''Brode Chalk'' was first mentioned in 1380. Bower Chalke had become a separate parish by the early 14th century.

16th century

c. 1536Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

granted Chalke to William Herbert (later Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke) during the dissolution of the monasteries. Henry VIII 'much valued' Herbert, a successful and ambitious soldier, who also became his brother-in-law through his marriage to Anne Parr, sister of Henry's last wife Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr ( – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until Henry's death on 28 January 1547. Catherine was the final queen consort o ...

. Henry heaped favours and honours (a knighthood) upon Herbert and granted him the estates of Wilton, Remesbury (north Wiltshire), and Cardiff Castle

Cardiff Castle () is a medieval castle and Victorian Gothic revival mansion located in the city centre of Cardiff, Wales. The original motte and bailey castle was built in the late 11th century by Norman invaders on top of a 3rd-century Roma ...

.

19th century

Chalke was a comparatively large, disconnected estate that was separated into the two ecclesiastical parishes of Broad Chalk and Bowerchalke in 1880. In 1885, 283 acres were transferred to Bower Chalke from

Chalke was a comparatively large, disconnected estate that was separated into the two ecclesiastical parishes of Broad Chalk and Bowerchalke in 1880. In 1885, 283 acres were transferred to Bower Chalke from Fifield Bavant

Fifield Bavant (/'fʌɪfiːld 'bavənt/) is a small village in the civil parish of Ebbesborne Wake, in Wiltshire, England, about southwest of Wilton, midway between Ebbesbourne Wake and Broad Chalke on the north bank of the River Ebble. Fifiel ...

, increasing its area to 3,260 acres (1,319 ha).

From 1878 until 1924 a unique village newspaper was written, printed, published and sold for a farthing by the Reverend Edward Collett, documenting the social history of the village. Two original sets of the papers still exist. One set is retained by Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

at Oxford and the second is on loan to the Wiltshire and Swindon Archives by its custodian Paul Lee, where it can be viewed in their offices at Chippenham. The papers were researched and published by Rex Sawyer as ''The Bowerchalke Parish Papers'' in 1989 after he had discovered the original printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

in his garden. In 2004 they were republished by The Hobnob Press as ''Collett's Farthing Newspaper: the Bowerchalke Village Newspaper, 1878–1924.'' (). Collett was also a keen amateur photographer and the majority of the photographs featured in the book are from his album.

20th century

In 1919Reginald Herbert, 15th Earl of Pembroke

Lt.-Col. Reginald Herbert, 15th Earl of Pembroke and 12th Earl of Montgomery (8 September 1880 – 13 January 1960), styled Lord Herbert from 1895 to 1913, was a British Army officer and peer from the Herbert family.

Early life and education

Her ...

started to sell the individual farms.

The village school closed in 1976 and children from Bowerchalke now attend the school in neighbouring Broad Chalke

Broad Chalke, sometimes spelled Broadchalke, Broad Chalk or Broadchalk, is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about west of the city of Salisbury. The civil parish includes the hamlets of Knapp, Mount Sorrel and Stoke Farthing.

...

. The old school buildings now serve as the Village Hall. The village pub, The Bell Inn, closed in 1988 and is now a residential dwelling known as Bell House.

The once renowned village cricket

Village cricket is a term, sometimes pejorative, given to the playing of cricket in rural villages in Britain. Many villages have their own teams that play at varying levels in local or regional club cricket leagues.

When organised cricket first ...

team, thanks in part to the dynasty of 'cricketing Gullivers' (Brian, David, Derek, Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

and Robin), closed c. 1973/74.

21st century

The villagepost office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letter (message), letters and parcel (package), parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post o ...

and general stores closed in 2003. The nearest post office is in Broad Chalke. An article about the closures called ''Village of the Damned'', written by David McKie

David McKie (born 1935) is a British journalist and historian.

He was deputy editor of ''The Guardian'' and continued to write a weekly column for that paper until 4 October 2007, called "Elsewhere". Until 10 September 2005, he also wrote a sec ...

, was published in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' on 30 June 2005. A response titled ''Bowerchalke is not the village of the Damned'' was written by Will Heaven, Assistant Comment Editor of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' on 30 August 2009.

In 2010 the Chalke Valley Cricket Club moved their cricket ground from the Chalke Valley Sports Centre in Broad Chalke to a new ground at Butt's Field, Bowerchalke, behind the Church under Marleycombe Hill, to allow a longer season and better facilities.

In 2011 Bowerchalke's new cricket ground became the main venue for the first annual Chalke Valley History Festival, co-organised by local author James Holland.

Religious sites

Parish church

A church was built at Bowerchalke c.1300. Pevsner and Orbach assess the style of the transept arches, andlancet window

A lancet window is a tall, narrow window with a sharp pointed arch at its top. This arch may or may not be a steep lancet arch (in which the compass centres for drawing the arch fall outside the opening). It acquired the "lancet" name from its rese ...

s in the nave and chancel, as consistent with that date, indicating that the building's cruciform plan was already in place. The north tower, with porch below, was added in the 15th century; the upper stage of the tower was rebuilt higher in the 19th century. The 16th century saw the addition of the north chapel (now used as the vestry) and the rebuilding of the transepts.

Restoration in 1886 by T.H. Wyatt included the rebuilding of the chancel and the addition of the south aisle. The roofs, pulpit, pews and polychrome tiled floor are all 19th-century work. The church was designated as Grade II* listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, H ...

in 1960.

The plain stone bowl of the font is 12th-century. There is a stone memorial to Alice Good (died 1735) and other tablets of the same family from the late 17th century and 18th century. The heaviest of the ring of bells was cast c.1400 at Salisbury, and another is dated 1611. In 1999 a new frame was installed and the number of bells increased from three to five.

Before and after the church was built, the area was part of the large Broad Chalke parish. Burials continued to take place at Broad Chalke until 1506. From the 16th century the living was a combined vicarage of Broad Chalke with Bower Chalke and Alvediston; in 1880 a separate perpetual curacy

Perpetual curate was a class of resident Parish (Church of England)#Parish priest, parish priest or Incumbent (ecclesiastical), incumbent curate within the United Church of England and Ireland (name of the combined Anglican churches of England an ...

was created for Bowerchalke. The living was reunited with Broad Chalke in 1952 and a group ministry was formed in 1972; today the parish is part of the Chalke Valley group, alongside twelve others.

Baptist church

A small chapel was built in stone in 1863–4, close to the church. In 1897 a larger chapel was built next to it in red brick, and the older building converted to a schoolroom. The chapel was still in use in 2007.

Amenities

Marleycombe Down, Knowle Down and Woodminton Down arechalk grassland

Calcareous grassland (or alkaline grassland) is an ecosystem associated with thin basic soil, such as that on chalk and limestone downland.

There are large areas of calcareous grassland in northwestern Europe, particularly areas of southern Engl ...

s which comprise the entire southern outlook of the village. They are jointly known as the Bowerchalke Downs

Bowerchalke Downs () (also known as Woodminton, Marleycombe Down and Knowle Down), is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest in southern Wiltshire, England, notified in 1971.

The downs encompass the entire southern outlook of the vil ...

, a Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain, or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle ...

with many species of plants, insects and butterflies.

The slopes of Marleycombe Down are used for hang gliding

Hang gliding is an air sports, air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised, fixed-wing aircraft, fixed-wing heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium al ...

and paragliding

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or in a cocoon-like 'pod' suspended be ...

.

The RSPB

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a Charitable_organization#United_Kingdom, charitable organisation registered in Charity Commission for England and Wales, England and Wales and in Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, ...

's Garston Wood nature reserve lies immediately beyond the southern boundary of the parish.

Notable people

* John Drew, schoolteacher, astronomer and meteorologist, was born at Bower Chalke in 1809. * William Thick was born in 1845 at Misselfore Green but left the village in 1868 to join the Metropolitan Police atWhitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

in London (warrant number 49989). In 1889, while investigating the Whitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the impoverished Whitechapel District (Metropolis), Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unso ...

, Sergeant Thick was named in letters as a prospective perpetrator, to wit ''I have very good grounds to believe that the person who has committed the Whitechapel Murders is a member of the police force.'' ... ''Sergeant William Thick''. (He is no longer a suspect.)

* Anglo-Canadian poet Marjorie Pickthall

Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall (14 September 1883, in Gunnersbury, London – 22 April 1922, in Vancouver) was a Canadian writer who was born in England but lived in Canada from the time she was seven. She was once "thought to be the best Can ...

(1883–1922) lived in Bowerchalke from 1913 to 1919, spending summers at Chalke Cottage where she wrote prolifically. She also attempted to start an enterprise in market gardening as part of the war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

effort.

* The Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

winning novelist William Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel '' Lord of the Flies'' (1954), Golding published another 12 volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 19 ...

, author of ''Lord of the Flies

''Lord of the Flies'' is the 1954 debut novel of British author William Golding. The plot concerns a group of prepubescent British boys who are stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempts to govern themselves that led to ...

'', '' The Inheritors'', etc. is buried in the village churchyard, having lived the middle part of his life in a cottage on the banks of the River Chalke. He named the Gaia hypothesis

The Gaia hypothesis (), also known as the Gaia theory, Gaia paradigm, or the Gaia principle, proposes that living organisms interact with their Inorganic compound, inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a Synergy, synergistic and Homeostasis, s ...

which was conceived by his walking companion Dr James Lovelock who lived in the village from c. 1960–1980 at both Pixies Cottage at Misselfore and at Clovers Cottage, Mead End.

* International violinist Iona Brown

Iona Brown, OBE, (7 January 19415 June 2004) was a British violinist and conductor.

Early life and education

Elizabeth Iona Brown was born in Salisbury and was educated at Cranborne Chase School, Dorset. Her parents, Antony and Fiona, were bo ...

lived in the village at Misselfore Cottage from 1968 until her death in 2004. When she took part in the BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

programme ''Kaleidoscope

A kaleidoscope () is an optical instrument with two or more reflecting surfaces (or mirrors) tilted to each other at an angle, so that one or more (parts of) objects on one end of these mirrors are shown as a symmetrical pattern when viewed fro ...

'', explaining how hard it was to play her signature piece ''The Lark Ascending

"The Lark Ascending" is a poem of 122 lines by the English poet George Meredith about the song of the skylark. Siegfried Sassoon called it matchless of its kind, "a sustained lyric which never for a moment falls short of the effect aimed at, s ...

'' by Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams ( ; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

, she said that the singing of lark

Larks are passerine birds of the family Alaudidae. Larks have a cosmopolitan distribution with the largest number of species occurring in Africa. Only a single species, the horned lark, occurs in North America, and only Horsfield's bush lark occ ...

s she heard during long walks on nearby Marleycombe Down influenced the way she played it.

Geology

The rocks of Bowerchalke that can be seen today were deposited underwater between 120 and 70 million years ago (mya) until they were then uplifted from the sea and have been sculpted byperiglacial

Periglaciation (adjective: "periglacial", referring to places at the edges of glacial areas) describes geomorphic processes that result from seasonal thawing and freezing, very often in areas of permafrost. The meltwater may refreeze in ice wedg ...

weathering and erosion over the last 1 million years.

The unseen underlying rocks of Bowerchalke started to form in shallow seas surrounding volcanic islands up to 1,000 million years ago (Proterozoic

The Proterozoic ( ) is the third of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8 Mya, and is the longest eon of Earth's geologic time scale. It is preceded by the Archean and followed by the Phanerozo ...

), about 60- 70 degrees south of the equator, the latitude of present-day Argentina. 'Proto-Bowerchalke' and the rest of England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

are part of Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent are terranes in parts of the eastern coast of North America: Atlantic Canada, and parts of the East Coast of the United States, East Coast of the ...

, a micro-continent that broke away from the southern landmass, and was 50 degrees south

Following are circles of latitude between the 45th parallel south and the 50th parallel south:

46th parallel south

The 46th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 46 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlant ...

of the equator about 500 mya. It joined with Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, i ...

just south of the equator 400 mya, and was crushed between Baltica, and Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

(North America), and Gondwanaland

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, Zealandia, Arabia, and the ...

(Africa, Australia, Antarctica and South America) 350 mya whilst near the equator (Variscan orogeny

The Variscan orogeny, or Hercynian orogeny, was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

Nomenclature

The name ''Varis ...

). Avalonia was landlocked and buffeted within Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea ( ) was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous period approximately 335 mi ...

just north of the equator 270 mya, and became part of a desert in the northern tropics 230 mya. Eventually it formed the west coast of Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

as America split away to form the Atlantic Ocean 120 mya. Bowerchalke then laid under warm chalk forming seas until being uplifted 70 mya as Africa started to collide with the European plate in the (Alpine Orogeny

The Alpine orogeny, sometimes referred to as the Alpide orogeny, is an orogenic phase in the Late Mesozoic and the current Cenozoic which has formed the mountain ranges of the Alpide belt.

Cause

The Alpine orogeny was caused by the African c ...

), and in the cooler shallow water river clay sediments capped the chalk. In the last million years the periglacial weathering has completely removed several hundred feet of chalk.

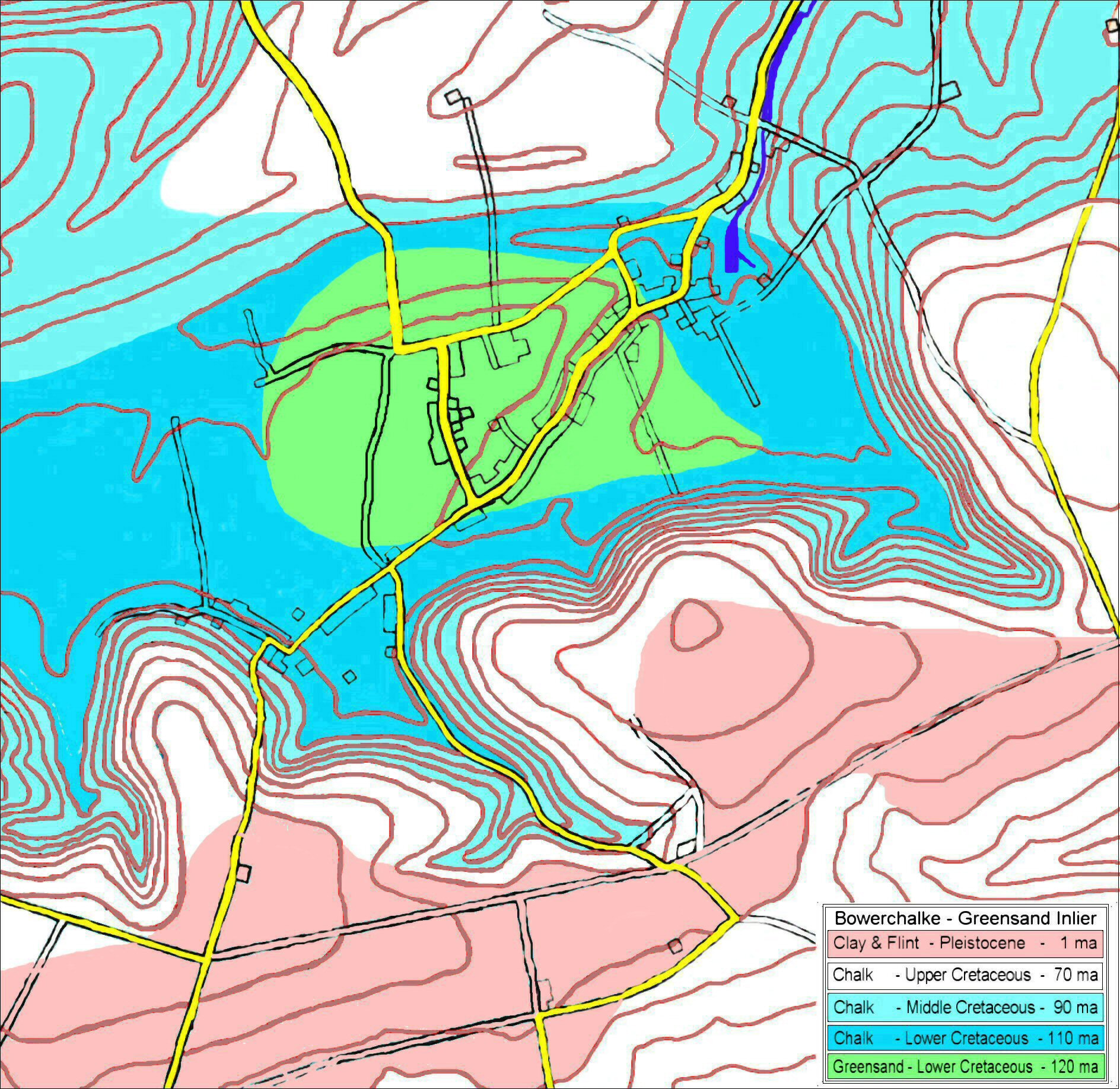

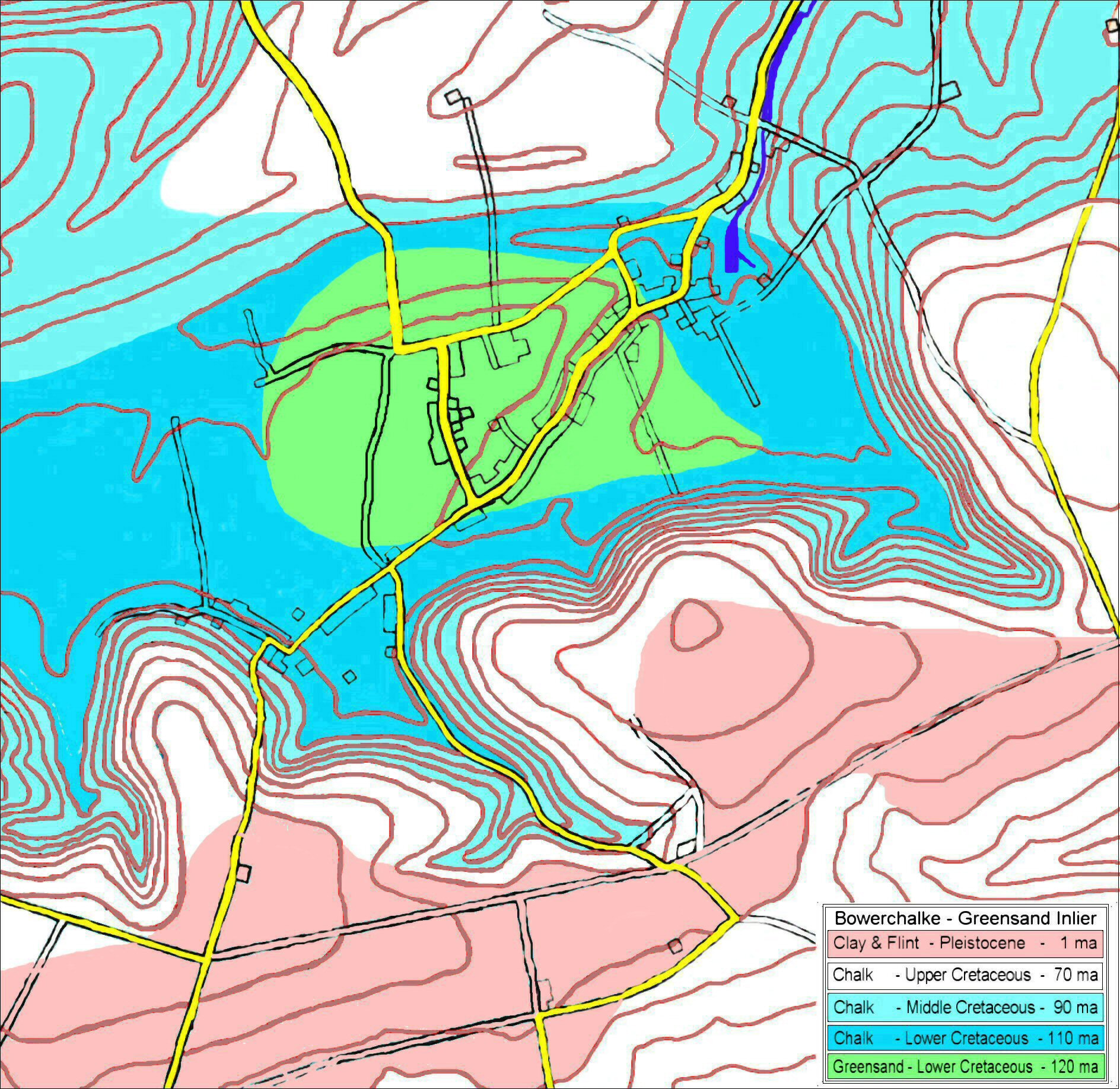

The main portion of the village is formed on the unique 'Bowerchalke greensand inlier

An inlier is an area of older rocks surrounded by younger rocks. Inliers are typically formed by the erosion of overlying younger rocks to reveal a limited exposure of the older underlying rocks. Faulting or folding may also contribute to the o ...

' (an area of older rock completely surrounded by younger layers), highlighted in green on the adjacent map. It is not immediately obvious to the naked eye or on the standard Ordnance Survey

The Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain. The agency's name indicates its original military purpose (see Artillery, ordnance and surveying), which was to map Scotland in the wake of the Jacobite rising of ...

maps with 10 metre contours but the apex is strikingly characterised by the 'island' drawn on the Andrews' and Dury's 1773 map. Its presence can be detected in the friable sandy soils in the centre of the village.

The

The Greensand

Greensand or green sand is a sand or sandstone which has a greenish color. This term is specifically applied to shallow marine sediment that contains noticeable quantities of rounded greenish grains. These grains are called ''glauconies'' and co ...

inlier is a dome shaped area of hard, coarse, olive-green coloured sandstone rock which has had its covering of softer chalk eroded away by 60 million years of weathering since the region was lifted out of the sea. The Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

Upper Greensand

Greensand or green sand is a sand or sandstone which has a greenish color. This term is specifically applied to shallow marine sediment that contains noticeable quantities of rounded greenish grains. These grains are called ''glauconies'' and co ...

is about 120 million years old and was deposited in brackish, oxygen depleted, water when Bowerchalke was located at around 35 degrees north of the equator, roughly equivalent to southern Spain and Portugal. At that time it was still part of the supercontinent Pangea which was just starting to split and form the Atlantic Ocean. The nearest continuous Upper Greensand exposure is along the A30 in the Nadder valley at Fovant

Fovant is a village and civil parish in southwest Wiltshire, England, lying about west of Salisbury on the A30 Salisbury-Shaftesbury road, on the south side of the Nadder valley.

History

The name is derived from the Old English ''Fobbefun ...

. The closest 'unique greensand inlier' is near Andover in Hampshire.

Surrounding the greensand is a ring of younger Lower Cretaceous

Lower may refer to:

* ''Lower'' (album), 2025 album by Benjamin Booker

* Lower (surname)

* Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

* Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

* Nizhny

{{Disambiguation ...

Chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

which is about 100 million years old (darker blue on the adjacent map). The chalk was formed in warm, shallow, well oxygenated waters from the remains of micro-organisms

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in Ja ...

(coccolithophores), over millions of years. At this time the Atlantic Ocean was about 100 miles wide and Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Somerset were a single island with rivers draining their nutrients into the warm sea that covered Wiltshire, Hampshire, the east of England

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sunrise, Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact ...

, Northern France, Denmark and northern Germany

Northern Germany (, ) is a linguistic, geographic, socio-cultural and historic region in the northern part of Germany which includes the coastal states of Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lower Saxony and the two city-states Hambur ...

.

Surrounding the lower chalk is a ringlike region of still younger Middle Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ninth and longest geologi ...

chalk (about 80 my)(light blue on the adjacent map). The whole area is bounded by the 'vast expanse' of Upper Cretaceous chalk (shown white on the adjacent map) that continued to form when Bowerchalke was about 45 degrees north, roughly equivalent to Bordeaux or the Dordogne in France. It was still under a shallow sea but Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, Ireland and Scotland had become separate islands. Bowerchalke was probably 15–30 miles offshore from the 'coast' between Shaftesbury

Shaftesbury () is a town and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is on the A30 road, west of Salisbury, Wiltshire, Salisbury and north-northeast of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester, near the border with Wiltshire. It is the only significant hi ...

and Dorchester.

Above the exposed Cretaceous chalk slopes of Marleycombe the hilltops are covered with a very young layer of Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

'clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

with flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

' that is about 1–10 million years old and formed by alluvial

Alluvium (, ) is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluvium is also sometimes called alluvial deposit. Alluvium is ...

sediments in cold shallow waters (pink on the adjacent map). The flints were formed in multiple layers as the clay sediment built up, and were then concentrated into a single dense layer as the last million years of sub glacial weathering washed the minute clay particles away.

The steepness of the north facing Marleycombe Down contrasts with the gentle rolling slopes towards Ebbesbourne Wake

Ebbesbourne Wake or Ebbesborne Wake is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, some south-west of Salisbury, near the head of the valley of the small River Ebble. The parish includes the hamlets of Fifield Bavant and West End. In 201 ...

. This is mainly due to erosion during the sustained permafrost

Permafrost () is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below ...

and tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

-like conditions in the periglacial zones of multiple ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

s. Although the southern limit of the main glaciation is a line across North Wiltshire

North Wiltshire was a Districts of England, local government district in Wiltshire, England, between 1974 and 2009, when it was superseded by the unitary area of Wiltshire (district), Wiltshire.

The district was formed on 1 April 1974 by a me ...

that corresponds to the M4 corridor

The M4 corridor is an area in the United Kingdom adjacent to the M4 motorway, which runs from London to South Wales. It is a major hi-tech hub. Important cities and towns linked by the M4 include (from east to west) London, Slough, Bracknell, M ...

, the sun rarely melted the north-facing snow pockets on Marlecombe Down, thus they eroded the soft chalks and clays by eating back into them, leaving the very steep scarp faces. The sporadic melting of snow and ice was forced to drain north east along the course of the River Chalke and River Ebble

The River Ebble is one of the five rivers of the English city of Salisbury. Rising at Alvediston to the west of the city, it joins the River Avon at Bodenham, near Nunton.

Description

The Ebble rises at Alvediston, to the west of Salisbur ...

in occasional summers, plus scouring the now dry channel that forms Church Street and Costers Lane. The southern boundary between the greensand and chalk is concealed beneath a layer of heavy clay that has accumulated at the bottom of Marleycombe Down due to the periglacial solifluction

Solifluction is a collective name for gradual processes in which a mass moves down a slope ("mass wasting") related to freeze-thaw activity. This is the standard modern meaning of solifluction, which differs from the original meaning given to i ...

. This scouring has also created the natural spring that supplies the River Chalke, whereby the rainfall from the surrounding watershed, having been filtered and channelled through the porous chalk, rises at the natural spring at 'Mead End' where the water table

The water table is the upper surface of the phreatic zone or zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with groundwater, which may be fresh, saline, or brackish, depending on the loc ...

sits on the underlying impervious greensand layer.

References

External links

Bowerchalke

at the

BBC Domesday Project

The BBC Domesday Project was a partnership between Acorn Computers, Philips, Logica, and the BBC (with some funding from the European Commission's ESPRIT programme) to mark the 900th anniversary of the original ''Domesday Book'', an 11th-centu ...

Images of Bowerchalke

at Geograph.com

at Romans in Britain

Bowerchalke at Wiltshire Community History

Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's 1773 map

Wiltshire Community History copy of Andrews' and Dury's 1810 map

{{authority control Villages in Wiltshire Bowerchalke inlier Civil parishes in Wiltshire