Bob Hawke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the 23rd

In 1971, Hawke along with other members of the ACTU requested that South Africa send a non-racially biased team for the rugby union tour, with the intention of unions agreeing not to serve the team in Australia. Prior to arrival, the Western Australian branch of the Transport Workers' Union, and the Barmaids' and Barmens' Union, announced that they would serve the team, which allowed the Springboks to land in Perth. The tour commenced on 26 June and riots occurred as anti-apartheid protesters disrupted games. Hawke and his family started to receive malicious mail and phone calls from people who thought that sport and politics should not mix. Hawke remained committed to the ban on apartheid teams and later that year, the South African cricket team was successfully denied and no apartheid team was to ever come to Australia again. It was this ongoing dedication to racial equality in South Africa that would later earn Hawke the respect and friendship of

In 1971, Hawke along with other members of the ACTU requested that South Africa send a non-racially biased team for the rugby union tour, with the intention of unions agreeing not to serve the team in Australia. Prior to arrival, the Western Australian branch of the Transport Workers' Union, and the Barmaids' and Barmens' Union, announced that they would serve the team, which allowed the Springboks to land in Perth. The tour commenced on 26 June and riots occurred as anti-apartheid protesters disrupted games. Hawke and his family started to receive malicious mail and phone calls from people who thought that sport and politics should not mix. Hawke remained committed to the ban on apartheid teams and later that year, the South African cricket team was successfully denied and no apartheid team was to ever come to Australia again. It was this ongoing dedication to racial equality in South Africa that would later earn Hawke the respect and friendship of

In particular, the political partnership that developed between Hawke and his

In particular, the political partnership that developed between Hawke and his

The Hawke government oversaw significant economic reforms, and is often cited by economic historians as being a "turning point" from a protectionist, agricultural model to a more globalised and services-oriented economy. According to the journalist Paul Kelly, "the most influential economic decisions of the 1980s were the floating of the Australian dollar and the deregulation of the financial system".Kelly, P., (1992), p.76 Although the

The Hawke government oversaw significant economic reforms, and is often cited by economic historians as being a "turning point" from a protectionist, agricultural model to a more globalised and services-oriented economy. According to the journalist Paul Kelly, "the most influential economic decisions of the 1980s were the floating of the Australian dollar and the deregulation of the financial system".Kelly, P., (1992), p.76 Although the

As a former ACTU President, Hawke was well-placed to engage in reform of the industrial relations system in Australia, taking a lead on this policy area as in few others. Working closely with ministerial colleagues and the ACTU Secretary, Bill Kelty, Hawke negotiated with trade unions to establish the

As a former ACTU President, Hawke was well-placed to engage in reform of the industrial relations system in Australia, taking a lead on this policy area as in few others. Working closely with ministerial colleagues and the ACTU Secretary, Bill Kelty, Hawke negotiated with trade unions to establish the

Arguably the most significant foreign policy achievement of the Government took place in 1989, after Hawke proposed a south-east Asian region-wide forum for leaders and economic ministers to discuss issues of common concern. After winning the support of key countries in the region, this led to the creation of the

Arguably the most significant foreign policy achievement of the Government took place in 1989, after Hawke proposed a south-east Asian region-wide forum for leaders and economic ministers to discuss issues of common concern. After winning the support of key countries in the region, this led to the creation of the

Hawke benefited greatly from the disarray into which the Liberal Party fell after the resignation of Fraser following the 1983 election. The Liberals were torn between supporters of the more conservative

Hawke benefited greatly from the disarray into which the Liberal Party fell after the resignation of Fraser following the 1983 election. The Liberals were torn between supporters of the more conservative

After leaving Parliament, Hawke entered the business world, taking on a number of directorships and consultancy positions which enabled him to achieve considerable financial success. He avoided public involvement with the Labor Party during Keating's tenure as prime minister, not wanting to be seen as attempting to overshadow his successor. After Keating's defeat and the election of the

After leaving Parliament, Hawke entered the business world, taking on a number of directorships and consultancy positions which enabled him to achieve considerable financial success. He avoided public involvement with the Labor Party during Keating's tenure as prime minister, not wanting to be seen as attempting to overshadow his successor. After Keating's defeat and the election of the

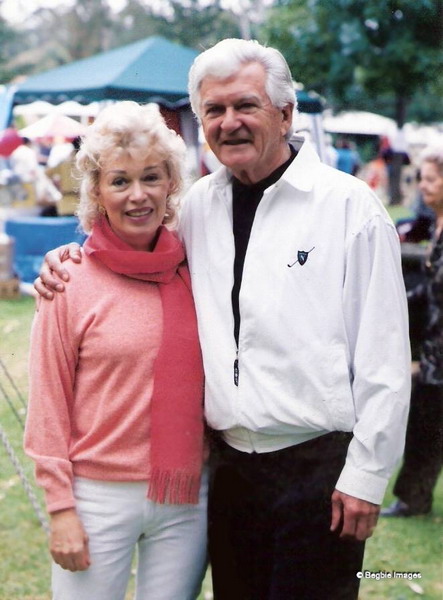

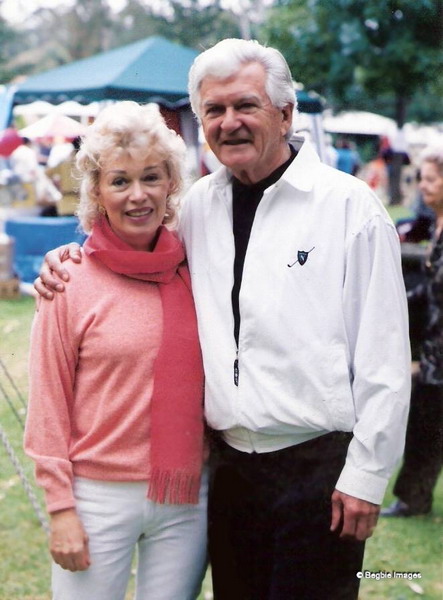

Hawke married Hazel Masterson in 1956 at Perth Trinity Church.Hurst, J., (1983), p.25 They had three children: Susan (born 1957), Stephen (born 1959) and Roslyn (born 1961). Their fourth child, Robert Jr, died in early infancy in 1963. Hawke was named Victorian Father of the Year in 1971, an honour which his wife disputed due to his heavy drinking and womanising. The couple divorced in 1994, after he left her for the writer Blanche d'Alpuget, and the two lived together in Northbridge, a suburb on the North Shore of Sydney. The divorce estranged Hawke from some of his family for a period, although they had reconciled by the 2010s.

Hawke was a supporter of

Hawke married Hazel Masterson in 1956 at Perth Trinity Church.Hurst, J., (1983), p.25 They had three children: Susan (born 1957), Stephen (born 1959) and Roslyn (born 1961). Their fourth child, Robert Jr, died in early infancy in 1963. Hawke was named Victorian Father of the Year in 1971, an honour which his wife disputed due to his heavy drinking and womanising. The couple divorced in 1994, after he left her for the writer Blanche d'Alpuget, and the two lived together in Northbridge, a suburb on the North Shore of Sydney. The divorce estranged Hawke from some of his family for a period, although they had reconciled by the 2010s.

Hawke was a supporter of

"Hawke Swoops into Power"

nbsp;– ''Time'', 14 March 1983

Robert Hawke

– Australia's Prime Ministers / National Archives of Australia

Bob Hawke Prime Ministerial Centre

* , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawke, Bob 1929 births 2019 deaths Alumni of University College, Oxford Australian agnostics Australian former Christians Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Leaders of the opposition (Australia) Australian National University alumni Australian people of Cornish descent Australian republicans Australian Rhodes Scholars Australian social democrats Australian trade unionists Australian Zionists Companions of the Order of Australia Former Congregationalists Grand Companions of the Order of Logohu Leaders of the Australian Labor Party Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Wills Members of the Cabinet of Australia People educated at Perth Modern School People from South Australia Politicians from Melbourne Prime ministers of Australia 20th-century prime ministers of Australia Trade unionists from Melbourne Treasurers of Australia University of Western Australia alumni Australian MPs 1980–1983 Australian MPs 1983–1984 Australian MPs 1984–1987 Australian MPs 1987–1990 Australian MPs 1990–1993

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

from 1983 to 1991. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party The title Leader of the Labour Party may refer to:

*Leader of the Labour Party (Ireland)

*Leader of the Labour Party (Netherlands)

*Leader of the Labour Party (UK)

**Leader of the Scottish Labour Party

*Leader of the New Zealand Labour Party

See al ...

(ALP), having previously served as president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), originally the Australasian Council of Trade Unions, is the largest peak body representing workers in Australia. It is a national trade union centre of 46 affiliated trade union, unions and eight t ...

from 1969 to 1980 and president of the Labor Party national executive from 1973 to 1978.

Hawke was born in Border Town

A border town is a town or city close to the boundary between two countries, states, or regions. Usually the term implies that the nearness to the border is one of the things the place is most famous for. With close proximities to a different coun ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

. He attended the University of Western Australia

University of Western Australia (UWA) is a public research university in the Australian state of Western Australia. The university's main campus is in Crawley, Western Australia, Crawley, a suburb in the City of Perth local government area. UW ...

and went on to study at University College, Oxford

University College, formally The Master and Fellows of the College of the Great Hall of the University commonly called University College in the University of Oxford and colloquially referred to as "Univ", is a Colleges of the University of Oxf ...

as a Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international Postgraduate education, postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Esta ...

. In 1956, Hawke joined the Australian Council of Trade Unions

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), originally the Australasian Council of Trade Unions, is the largest peak body representing workers in Australia. It is a national trade union centre of 46 affiliated trade union, unions and eight t ...

(ACTU) as a research officer. Having risen to become responsible for national wage case arbitration, he was elected as president of the ACTU in 1969, where he achieved a high public profile. In 1973, he was appointed as president of the Labor Party.

In 1980, Hawke stood down from his roles as ACTU and Labor Party president to announce his intention to enter parliamentary politics, and was subsequently elected to the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Australian Senate, Senate. Its composition and powers are set out in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

...

as a member of parliament (MP) for the division of Wills

The Division of Wills is an Australian Electoral Division, Australian electoral division of Victoria (Australia), Victoria. It is currently represented by Peter Khalil of the Australian Labor Party.

The electorate encompasses many of the subur ...

at the 1980 federal election. Three years later, he was elected unopposed to replace Bill Hayden as leader of the Australian Labor Party

The leader of the Australian Labor Party is the highest political office within the federal Australian Labor Party (ALP). Leaders of the party are chosen from among the sitting members of the parliamentary caucus either by members alone or wi ...

, and within five weeks led Labor to a landslide victory

A landslide victory is an election result in which the winning Candidate#Candidates in elections, candidate or political party, party achieves a decisive victory by an overwhelming margin, securing a very large majority of votes or seats far beyo ...

at the 1983 election, and was sworn in as prime minister. He led Labor to victory a further three times, with successful outcomes in 1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

, 1987

Events January

* January 1 – Bolivia reintroduces the Boliviano currency.

* January 2 – Chadian–Libyan conflict – Battle of Fada: The Military of Chad, Chadian army destroys a Libyan armoured brigade.

* January 3 – Afghan leader ...

and 1990 elections, making him the most electorally successful prime minister in the history of the Labor Party.

The Hawke government

The Hawke government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Bob Hawke of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1983 to 1991. The government followed the Liberal-National Coalition Fraser government and was su ...

implemented a significant number of reforms, including major economic reforms, the establishment of Landcare, the introduction of the universal healthcare

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured right to health, access to health care. It is genera ...

scheme Medicare, brokering the Prices and Incomes Accord

The Prices and Incomes Accord (also known as The Accord, the ALP–ACTU Accord, or ACTU–Labor Accord) was a series of agreements between the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), in effect from ...

, creating APEC

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC ) is an inter-governmental forum for 21 member economy , economies in the Pacific Rim that promotes free trade throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Following the success of Association of Southeast Asia ...

, floating the Australian dollar

The Australian dollar (currency sign, sign: $; ISO 4217, code: AUD; also abbreviated A$ or sometimes AU$ to distinguish it from other dollar, dollar-denominated currencies; and also referred to as the dollar or Aussie dollar) is the official ...

, deregulating the financial sector, introducing the Family Assistance Scheme, enacting the Sex Discrimination Act to prevent discrimination in the workplace, declaring "Advance Australia Fair

"Advance Australia Fair" is the national anthem of Australia. Written by Scottish-born Australian composer Peter Dodds McCormick, the song was first performed as a patriotic song in Australia in 1878. It replaced "God Save the King, God Save th ...

" as the country's national anthem, initiating superannuation pension schemes for all workers, negotiating a ban on mining in Antarctica and overseeing passage of the Australia Act that removed all remaining jurisdiction by the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

from Australia.

In June 1991, Hawke faced a leadership challenge by the Treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

, Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and trade unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously ser ...

, but Hawke managed to retain power; however, Keating mounted a second challenge six months later, and won narrowly, replacing Hawke as prime minister. Hawke subsequently retired from parliament, pursuing both a business career and a number of charitable causes, until his death in 2019, aged 89. Hawke remains his party's longest-serving Prime Minister, and Australia's third-longest-serving prime minister behind Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

and John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

. He is also the only prime minister to be born in South Australia and the only one raised and educated in Western Australia. Hawke holds the highest-ever approval rating for an Australian prime minister, reaching 75% approval in 1984. Hawke is frequently ranked within the upper tier of Australian prime ministers by historians.

Early life and family

Bob Hawke was born on 9 December 1929 inBorder Town

A border town is a town or city close to the boundary between two countries, states, or regions. Usually the term implies that the nearness to the border is one of the things the place is most famous for. With close proximities to a different coun ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

, the second child of Arthur "Clem" Hawke (1898–1989), a Congregationalist minister, and his wife Edith Emily (Lee) (1897–1979) (known as Ellie), a schoolteacher. His uncle, Bert, was the Labor premier of Western Australia

The premier of Western Australia is the head of government of the state of Western Australia. The role of premier at a state level is similar to the role of the prime minister of Australia at a federal level. The premier leads the executive br ...

between 1953 and 1959.

Hawke's brother Neil, who was seven years his senior, died at the age of seventeen after contracting meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

, for which there was no cure at the time. Ellie Hawke subsequently developed an almost messianic belief in her son's destiny, and this contributed to Hawke's supreme self-confidence throughout his career. At the age of fifteen, he presciently boasted to friends that he would one day become the prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

.

At the age of seventeen, Hawke had a serious crash while riding his Panther motorcycle that left him in a critical condition for several days. This near-death experience acted as his catalyst, driving him to make the most of his talents and not let his abilities go to waste. He joined the Labor Party in 1947 at the age of eighteen.

Education and early career

Hawke was educated at West Leederville State School, Perth Modern School and theUniversity of Western Australia

University of Western Australia (UWA) is a public research university in the Australian state of Western Australia. The university's main campus is in Crawley, Western Australia, Crawley, a suburb in the City of Perth local government area. UW ...

, graduating in 1952 with Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws degrees. He was also president of the university's guild during the same year. The following year, Hawke won a Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Established in 1902, it is ...

to attend University College, Oxford

University College, formally The Master and Fellows of the College of the Great Hall of the University commonly called University College in the University of Oxford and colloquially referred to as "Univ", is a Colleges of the University of Oxf ...

, where he began a Bachelor of Arts course in philosophy, politics and economics

Philosophy, politics and economics, or politics, philosophy and economics (PPE), is an interdisciplinary undergraduate or postgraduate academic degree, degree which combines study from three disciplines. The first institution to offer degrees in P ...

(PPE). He soon found he was covering much the same ground as he had in his education at the University of Western Australia, and transferred to a Bachelor of Letters

Bachelor of Letters (BLitt or LittB; Latin ' or ') is a second bachelor's degree in which students specialize in an area of study relevant to their own personal, professional, or academic development. This area of study may have been touched on in ...

course. He wrote his thesis on wage-fixing in Australia and successfully presented it in January 1956.Hawke, Bob (1994), p. 28

In 1956, Hawke accepted a scholarship to undertake doctoral studies in the area of arbitration law in the law department at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public university, public research university and member of the Group of Eight (Australian universities), Group of Eight, located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton, A ...

in Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

. Soon after his arrival at ANU, he became the students' representative on the University Council. A year later, he was recommended to the President of the ACTU

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), originally the Australasian Council of Trade Unions, is the largest peak body representing workers in Australia. It is a national trade union centre of 46 affiliated trade union, unions and eight t ...

to become a research officer, replacing Harold Souter who had become ACTU Secretary. The recommendation was made by Hawke's mentor at ANU, H. P. Brown, who for a number of years had assisted the ACTU in national wage cases. Hawke decided to abandon his doctoral studies and accept the offer, moving to Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

with his wife Hazel

Hazels are plants of the genus ''Corylus'' of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family, Betulaceae,Germplasmgobills Information Network''Corylus''Rushforth, K ...

.

World record beer skol (scull)

Hawke is well known for a "world record" allegedly achieved at Oxford University for a beer skol (scull) of a yard of ale in 11 seconds. The record is widely regarded as having been important to his career and ocker chic image. A 2023 article in the ''Journal of Australian Studies'' by C. J. Coventry concluded that Hawke's achievement was "possibly fabricated" and "cultural propaganda" designed to make Hawke appealing to unionised workers and nationalistic middle-class voters. The article contends that "its location and time remain uncertain; there are no known witnesses; the field of competition was exclusive and with no scientific accountability; the record was first published in a beer pamphlet; and Hawke's recollections were unreliable."Australian Council of Trade Unions

Not long after Hawke began work at the ACTU, he became responsible for the presentation of its annual case for higher wages to the national wages tribunal, the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. He was first appointed as an ACTU advocate in 1959. The 1958 case, under previous advocate R.L. Eggleston, had yielded only a five-shilling increase. The 1959 case found for a fifteen-shilling increase, and was regarded as a personal triumph for Hawke. He went on to attain such success and prominence in his role as an ACTU advocate that, in 1969, he was encouraged to run for the position of ACTU President, despite the fact that he had never held elected office in a trade union. He was elected ACTU President in 1969 on a modernising platform by the narrow margin of 399 to 350, with the support of the left of the union movement, including some associated with theCommunist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia (CPA), known as the Australian Communist Party (ACP) from 1944 to 1951, was an Australian communist party founded in 1920. The party existed until roughly 1991, with its membership and influence having been ...

. He later credited Ray Gietzelt

Ray Gietzelt Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (29 September 192212 October 2012) was a major figure in the Australian union movement in the latter part of the 20th century. He led the Federated Miscellaneous Workers' Union of Australia (FM ...

, General Secretary of the FMWU, as the single most significant union figure in helping him achieve this outcome. Questioned after his election on his political stance, Hawke stated that "socialist is not a word I would use to describe myself", saying instead his approach to politics was pragmatic. His commitment to the cause of Jewish Refuseniks purportedly led to a planned assassination attempt on Hawke by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP; ) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organization founded in 1967 by George Habash. It has consistently been the second-largest of the groups forming the Palestine Liberation ...

, and its Australian operative Munif Mohammed Abou Rish.

In 1971, Hawke along with other members of the ACTU requested that South Africa send a non-racially biased team for the rugby union tour, with the intention of unions agreeing not to serve the team in Australia. Prior to arrival, the Western Australian branch of the Transport Workers' Union, and the Barmaids' and Barmens' Union, announced that they would serve the team, which allowed the Springboks to land in Perth. The tour commenced on 26 June and riots occurred as anti-apartheid protesters disrupted games. Hawke and his family started to receive malicious mail and phone calls from people who thought that sport and politics should not mix. Hawke remained committed to the ban on apartheid teams and later that year, the South African cricket team was successfully denied and no apartheid team was to ever come to Australia again. It was this ongoing dedication to racial equality in South Africa that would later earn Hawke the respect and friendship of

In 1971, Hawke along with other members of the ACTU requested that South Africa send a non-racially biased team for the rugby union tour, with the intention of unions agreeing not to serve the team in Australia. Prior to arrival, the Western Australian branch of the Transport Workers' Union, and the Barmaids' and Barmens' Union, announced that they would serve the team, which allowed the Springboks to land in Perth. The tour commenced on 26 June and riots occurred as anti-apartheid protesters disrupted games. Hawke and his family started to receive malicious mail and phone calls from people who thought that sport and politics should not mix. Hawke remained committed to the ban on apartheid teams and later that year, the South African cricket team was successfully denied and no apartheid team was to ever come to Australia again. It was this ongoing dedication to racial equality in South Africa that would later earn Hawke the respect and friendship of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

.

In industrial matters, Hawke continued to demonstrate a preference for, and considerable skill at, negotiation, and was generally liked and respected by employers as well as the unions he advocated for. As early as 1972, speculation began that he would seek to enter the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the Monarchy of Australia, monarch of Australia (repr ...

and eventually run to become the Leader of the Australian Labor Party

The leader of the Australian Labor Party is the highest political office within the federal Australian Labor Party (ALP). Leaders of the party are chosen from among the sitting members of the parliamentary caucus either by members alone or wi ...

. But while his professional career continued successfully, his heavy drinking and womanising placed considerable strains on his family life.

In June 1973, Hawke was elected as the Federal President of the Labor Party. Two years later, when the Whitlam government

The Whitlam government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party. The government commenced when Labor defeated the McMahon government at the 1972 Australian federal elect ...

was controversially dismissed by the Governor-General, Hawke showed an initial keenness to enter Parliament at the ensuing election. Harry Jenkins, the MP for Scullin, came under pressure to step down to allow Hawke to stand in his place, but he strongly resisted this push. Hawke eventually decided not to attempt to enter Parliament at that time, a decision he soon regretted. After Labor was defeated at the election, Whitlam initially offered the leadership to Hawke, although it was not within Whitlam's power to decide who would succeed him. Despite not taking on the offer, Hawke remained influential, playing a key role in averting national strike action.

During the 1977 federal election, he emerged as a strident opponent of accepting Vietnamese boat people

Vietnamese boat people () were refugees who fled Vietnam by boat and ship following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. This migration and humanitarian crisis was at its highest in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but continued well into the earl ...

as refugees into Australia, stating that they should be subject to normal immigration requirements and should otherwise be deported. He further stated only refugees selected off-shore should be accepted.

Hawke resigned as President of the Labor Party in August 1978. Neil Batt was elected in his place. The strain of this period took its toll on Hawke and in 1979 he suffered a physical collapse. This shock led Hawke to publicly announce his alcoholism in a television interview, and that he would make a concerted—and ultimately successful—effort to overcome it. He was helped through this period by the relationship that he had established with writer Blanche d'Alpuget, who, in 1982, published a biography of Hawke. His popularity with the public was, if anything, enhanced by this period of rehabilitation, and opinion polling suggested that he was a more popular public figure than either Labor Leader Bill Hayden or Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

.

Informer for the United States

During the period of 1973 to 1979, Hawke acted as aninformant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a "snitch", "rat", "canary", "stool pigeon", "stoolie", "tout" or "grass", among other terms) is a person who provides privileged information, or (usually damaging) information inten ...

for the United States government. According to Coventry, Hawke as concurrent leader of the ACTU and ALP informed the US of details surrounding labour disputes, especially those relating to American companies and individuals, such as union disputes with Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

and the black ban of Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Honorific nicknames in popular music, Nicknamed the "Chairman of the Board" and "Ol' Blue Eyes", he is regarded as one of the Time 100: The Most I ...

. The major industrial action taken against Sinatra came about because Sinatra had made sexist comments against female journalists. The dispute was the subject of the 2003 film '' The Night We Called It a Day''.

Hawke was described by US diplomats as "a bulwark against anti-American sentiment and resurgent communism during the economic turmoil of the 1970s", and often disputed with the Whitlam government

The Whitlam government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party. The government commenced when Labor defeated the McMahon government at the 1972 Australian federal elect ...

over issues of foreign policy and industrial relations. US diplomats played a major role in shaping Hawke's consensus politics and economics. Although Hawke was the most prolific Australian informer for the United States in the 1970s, there were other prominent people at that time who secretly gave information. Biographer Troy Bramston rejects the view that Hawke's prolonged, discreet involvement with known members of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

within the US Embassy amounted to Hawke being a CIA "spy".

Member of Parliament

Hawke's first attempt to enter Parliament came during the 1963 federal election. He stood in the seat of Corio inGeelong

Geelong ( ) (Wathawurrung language, Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in Victoria, Australia, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon River (Victo ...

and managed to achieve a 3.1% swing against the national trend, although he fell short of ousting longtime Liberal incumbent Hubert Opperman. Hawke rejected several opportunities to enter Parliament throughout the 1970s, something he later wrote that he "regretted". He eventually stood for election to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

at the 1980 election for the safe Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

seat of Wills, winning it comfortably. Immediately upon his election to Parliament, Hawke was appointed to the Shadow Cabinet by Labor Leader Bill Hayden as Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations.

Hayden, after having led the Labor Party to narrowly lose the 1980 election, was increasingly subject to criticism from Labor MPs over his leadership style. To quell speculation over his position, Hayden called a leadership spill on 16 July 1982, believing that if he won he would be guaranteed to lead Labor through to the next election. Hawke decided to challenge Hayden in the spill, but Hayden defeated him by five votes; the margin of victory, however, was too slim to dispel doubts that he could lead the Labor Party to victory at an election. Despite his defeat, Hawke began to agitate more seriously behind the scenes for a change in leadership, with opinion polls continuing to show that Hawke was a far more popular public figure than both Hayden and Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

. Hayden was further weakened after Labor's unexpectedly poor performance at a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, or a bypoll in India, is an election used to fill an office that has become vacant between general elections.

A vacancy may arise as a result of an incumben ...

in December 1982 for the Victorian seat of Flinders, following the resignation of the sitting member, former deputy Liberal leader Phillip Lynch. Labor needed a swing of 5.5% to win the seat and had been predicted by the media to win, but could only achieve 3%.Hurst, J., (1983), p. 270

Labor Party power-brokers, such as Graham Richardson and Barrie Unsworth

Barrie John Unsworth (born 16 April 1934) is an Australian former politician, representing the Labor Party in the Parliament of New South Wales from 1978 to 1991. He served as the 36th Premier from July 1986 to March 1988. Since the death o ...

, now openly switched their allegiance from Hayden to Hawke. More significantly, Hayden's staunch friend and political ally, Labor's Senate Leader John Button, had become convinced that Hawke's chances of victory at an election were greater than Hayden's. Initially, Hayden believed that he could remain in his job, but Button's defection proved to be the final straw in convincing Hayden that he would have to resign as Labor Leader.Hurst, J., (1983), p. 273 Less than two months after the Flinders by-election result, Hayden announced his resignation as Leader of the Labor Party on 3 February 1983. Hawke was subsequently elected as Leader unopposed on 8 February, and became Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

in the process. Having learned that morning about the possible leadership change, on the same that Hawke assumed the leadership of the Labor Party, Malcolm Fraser called a snap election for 5 March 1983, unsuccessfully attempting to prevent Labor from making the leadership change. However, he was unable to have the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

confirm the election before Labor announced the change.

At the 1983 election, Hawke led Labor to a landslide victory, achieving a 24-seat swing and ending seven years of Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

rule.

With the election called at the same time that Hawke became Labor leader this meant that Hawke never sat in Parliament as Leader of the Opposition having spent the entirety of his short Opposition leadership in the election campaign which he won.

Prime Minister of Australia (1983–1991)

Leadership style

After Labor's landslide victory, Hawke was sworn in as the Prime Minister by the Governor-General Ninian Stephen on 11 March 1983. The style of theHawke government

The Hawke government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Bob Hawke of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1983 to 1991. The government followed the Liberal-National Coalition Fraser government and was su ...

was deliberately distinct from the Whitlam government

The Whitlam government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party. The government commenced when Labor defeated the McMahon government at the 1972 Australian federal elect ...

, the Labor government that preceded it. Rather than immediately initiating multiple extensive reform programs as Whitlam had, Hawke announced that Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

's pre-election concealment of the budget deficit meant that many of Labor's election commitments would have to be deferred. As part of his internal reforms package, Hawke divided the government into two tiers, with only the most senior ministers sitting in the Cabinet of Australia

The Cabinet of Australia, also known as the Federal Cabinet, is the chief decision-making body of the Australian government. The Cabinet is selected by the prime minister and is composed of senior government ministers who administer the exec ...

. The Labor caucus was still given the authority to determine who would make up the Ministry, but this move gave Hawke unprecedented powers to empower individual ministers.Kelly, P., (1992), p. 30

After Australia won the America's Cup

The America's Cup is a sailing competition and the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one from the yacht club that currently holds the trophy (known ...

in 1983 Hawke said "any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up today is a bum", effectively declaring an impromptu national public holiday.

In particular, the political partnership that developed between Hawke and his

In particular, the political partnership that developed between Hawke and his Treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

, Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and trade unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously ser ...

, proved to be essential to Labor's success in government, with multiple Labor figures in years since citing the partnership as the party's greatest ever. The two men proved a study in contrasts: Hawke was a Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international Postgraduate education, postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Esta ...

; Keating left high school early. Hawke's enthusiasms were cigars, betting and most forms of sport; Keating preferred classical architecture

Classical architecture typically refers to architecture consciously derived from the principles of Ancient Greek architecture, Greek and Ancient Roman architecture, Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or more specifically, from ''De archit ...

, Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

symphonies and collecting British Regency

The Regency era of British history is commonly understood as the years between and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820. King George III first suffered debilitating illness in the lat ...

and French Empire antiques. Despite not knowing one another before Hawke assumed the leadership in 1983, the two formed a personal as well as political relationship which enabled the Government to pursue a significant number of reforms, although there were occasional points of tension between the two.

The Labor Caucus under Hawke also developed a more formalised system of parliamentary factions, which significantly altered the dynamics of caucus operations. Unlike many of his predecessor leaders, Hawke's authority within the Labor Party was absolute. This enabled him to persuade MPs to support a substantial set of policy changes which had not been considered achievable by Labor governments in the past. Individual accounts from ministers indicate that while Hawke was not often the driving force behind individual reforms, outside of broader economic changes, he took on the role of providing political guidance on what was electorally feasible and how best to sell it to the public, tasks at which he proved highly successful. Hawke took on a very public role as Prime Minister, campaigning frequently even outside of election periods, and for much of his time in office proved to be incredibly popular with the Australian electorate; to this date he still holds the highest ever AC Nielsen approval rating of 75%.

Economic policy

The Hawke government oversaw significant economic reforms, and is often cited by economic historians as being a "turning point" from a protectionist, agricultural model to a more globalised and services-oriented economy. According to the journalist Paul Kelly, "the most influential economic decisions of the 1980s were the floating of the Australian dollar and the deregulation of the financial system".Kelly, P., (1992), p.76 Although the

The Hawke government oversaw significant economic reforms, and is often cited by economic historians as being a "turning point" from a protectionist, agricultural model to a more globalised and services-oriented economy. According to the journalist Paul Kelly, "the most influential economic decisions of the 1980s were the floating of the Australian dollar and the deregulation of the financial system".Kelly, P., (1992), p.76 Although the Fraser government

The Fraser government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. It was made up of members of a Liberal–Country party coalition in the Australian Parliament from November 1975 to March 1983. Init ...

had played a part in the process of financial deregulation by commissioning the 1981 Campbell Report, opposition from Fraser himself had stalled this process. Shortly after its election in 1983, the Hawke government took the opportunity to implement a comprehensive program of economic reform, in the process "transform(ing) economics and politics in Australia".

Hawke and Keating together led the process for overseeing the economic changes by launching a "National Economic Summit" one month after their election in 1983, which brought together business and industrial leaders together with politicians and trade union leaders; the three-day summit led to a unanimous adoption of a national economic strategy, generating sufficient political capital for widespread reform to follow. Among other reforms, the Hawke government floated the Australian dollar, repealed rules that prohibited foreign-owned banks to operate in Australia, dismantled the protectionist tariff system, privatised several state sector industries, ended the subsidisation of loss-making industries, and sold off part of the state-owned Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), also known as Commonwealth Bank or simply CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of fi ...

.

The taxation system was also significantly reformed, with income tax rates reduced and the introduction of a fringe benefits tax and a capital gains tax; the latter two reforms were strongly opposed by the Liberal Party at the time, but were never reversed by them when they eventually returned to office in 1996. Partially offsetting these imposts upon the business community—the "main loser" from the 1985 Tax Summit according to Paul Kelly—was the introduction of full dividend imputation

Dividend imputation is a corporate tax system in which some or all of the tax paid by a company may be attributed, or imputed, to the shareholders by way of a tax credit to reduce the income tax payable on a distribution. In comparison to the c ...

, a reform insisted upon by Keating. Funding for schools was also considerably increased as part of this package, while financial assistance was provided for students to enable them to stay at school longer; the number of Australian children completing school rose from 3 in 10 at the beginning of the Hawke government to 7 in 10 by its conclusion in 1991. Considerable progress was also made in directing assistance "to the most disadvantaged recipients over the whole range of welfare benefits."

Social and environmental policy

Although criticisms were leveled against the Hawke government that it did not achieve all it said it would do on social policy, it nevertheless enacted a series of reforms which remain in place to the present day. From 1983 to 1989, the Government oversaw the permanent establishment ofuniversal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized a ...

in Australia with the creation of Medicare, doubled the number of subsidised childcare places, began the introduction of occupational superannuation, oversaw a significant increase in school retention rates, created subsidised homecare services, oversaw the elimination of poverty traps in the welfare system, increased the real value of the old-age pension, reintroduced the six-monthly indexation of single-person unemployment benefits, and established a wide-ranging programme for paid family support, known as the Family Income Supplement.Whitlam, Wran and the Labor tradition: Labor history essays, volume two By Gough Whitlam, Australian Labor Party, New South Wales Branch

A number of other new social security benefits were introduced under the Hawke-Keating Government. In 1984, for instance, a remote area allowance was introduced for pensioners and beneficiaries residing in special areas of Tax Zone A, and in 1985 a special addition to family allowances was made payable (as noted by one study) “to certain families with multiple births (three children or more) until the children reach six years of age.” The following year, rent assistance was extended to unemployment beneficiaries, together with a young homeless allowance for sickness and unemployment beneficiaries under the age of 18 who were homeless and didn't have parental or custodial support. However, the payment of family allowances for student children reaching the age of 18 was discontinued except in the case of certain families on low incomes.

During the 1980s, the proportion of total government outlays allocated to families, the sick, single parents, widows, the handicapped, and veterans was significantly higher than under the previous Fraser and Whitlam governments.

In 1984, the Hawke government enacted the landmark Sex Discrimination Act 1984

The ''Sex Discrimination Act 1984'' is an Act of the Parliament of Australia which prohibits discrimination on the basis of mainly sexism, homophobia, transphobia and biphobia, but also sex, marital or relationship status, actual or potentia ...

, which eliminated discrimination on the grounds of sex within the workplace. In 1989, Hawke oversaw the gradual re-introduction of some tuition fees for university study, setting up the Higher Education Contributions Scheme (HECS). Under the original HECS, a fee of , equivalent to in , was charged to all university students, and the Commonwealth paid the balance. A student could defer payment of this HECS amount and repay the debt through the tax system, when the student's income exceeds a threshold level. As part of the reforms, Colleges of Advanced Education entered the university sector by various means. By doing so, university places were able to be expanded. Further notable policy decisions taken during the Government's time in office included the public health campaign regarding HIV/AIDS, and Indigenous land rights reform, with an investigation of the idea of a treaty between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the Government being launched, although the latter would be overtaken by events, notably the Mabo court decision.

The Hawke government also drew attention for a series of notable environmental decisions, particularly in its second and third terms. In 1983, Hawke personally vetoed the construction of the Franklin Dam in Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, responding to a groundswell of protest around the issue. Hawke also secured the nomination of the Wet Tropics of Queensland

The Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Site consists of approximately 8,940 km2 of Australian wet tropical forests growing along the north-east Queensland portion of the Great Dividing Range. The Wet Tropics of Queensland meets all f ...

as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1987, preventing the forests there from being logged. Hawke would later appoint Graham Richardson as Environment Minister, tasking him with winning the second-preference support from environmental parties, something which Richardson later claimed was the major factor in the government's narrow re-election at the 1990 election. In the Government's fourth term, Hawke personally led the Australian delegation to secure changes to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, ultimately winning a guarantee that drilling for minerals within Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

would be totally prohibited until 2048 at the earliest. Hawke later claimed that the Antarctic drilling ban was his "proudest achievement".

Industrial relations policy

As a former ACTU President, Hawke was well-placed to engage in reform of the industrial relations system in Australia, taking a lead on this policy area as in few others. Working closely with ministerial colleagues and the ACTU Secretary, Bill Kelty, Hawke negotiated with trade unions to establish the

As a former ACTU President, Hawke was well-placed to engage in reform of the industrial relations system in Australia, taking a lead on this policy area as in few others. Working closely with ministerial colleagues and the ACTU Secretary, Bill Kelty, Hawke negotiated with trade unions to establish the Prices and Incomes Accord

The Prices and Incomes Accord (also known as The Accord, the ALP–ACTU Accord, or ACTU–Labor Accord) was a series of agreements between the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), in effect from ...

in 1983, an agreement whereby unions agreed to restrict their demands for wage increases, and in turn the Government guaranteed to both minimise inflation and promote an increased social wage, including by establishing new social programmes such as Medicare.

Inflation had been a significant issue for the previous decade prior to the election of the Hawke government, regularly running into double-digits. The process of the Accord, by which the Government and trade unions would arbitrate and agree upon wage increases in many sectors, led to a decrease in both inflation and unemployment through to 1990. Criticisms of the Accord would come from both the right and the left of politics. Left-wing critics claimed that it kept real wages stagnant, and that the Accord was a policy of class collaboration and corporatism

Corporatism is an ideology and political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come toget ...

. By contrast, right-wing critics claimed that the Accord reduced the flexibility of the wages system. Supporters of the Accord, however, pointed to the improvements in the social security system that occurred, including the introduction of rental assistance for social security recipients, the creation of labour market schemes such as NewStart, and the introduction of the Family Income Supplement. In 1986, the Hawke government passed a bill to de-register the Builders Labourers Federation federally due to the union not following the Accord agreements.

Despite a percentage fall in real money wages from 1983 to 1991, the social wage of Australian workers was argued by the Government to have improved drastically as a result of these reforms, and the ensuing decline in inflation. The Accord was revisited six further times during the Hawke government, each time in response to new economic developments. The seventh and final revisiting would ultimately lead to the establishment of the enterprise bargaining system, although this would be finalised shortly after Hawke left office in 1991.

Foreign policy

Arguably the most significant foreign policy achievement of the Government took place in 1989, after Hawke proposed a south-east Asian region-wide forum for leaders and economic ministers to discuss issues of common concern. After winning the support of key countries in the region, this led to the creation of the

Arguably the most significant foreign policy achievement of the Government took place in 1989, after Hawke proposed a south-east Asian region-wide forum for leaders and economic ministers to discuss issues of common concern. After winning the support of key countries in the region, this led to the creation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC ) is an inter-governmental forum for 21 member economy , economies in the Pacific Rim that promotes free trade throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Following the success of Association of Southeast Asia ...

(APEC). The first APEC meeting duly took place in Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

in November 1989; the economic ministers of Australia, Brunei

Brunei, officially Brunei Darussalam, is a country in Southeast Asia, situated on the northern coast of the island of Borneo. Apart from its coastline on the South China Sea, it is completely surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak, with ...

, Canada, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and the United States all attended. APEC would subsequently grow to become one of the most pre-eminent high-level international forums in the world, particularly after the later inclusions of China and Russia, and the Keating government's later establishment of the APEC Leaders' Forum.

Elsewhere in Asia, the Hawke government played a significant role in the build-up to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

peace process

A peace process is the set of political sociology, sociopolitical negotiations, agreements and actions that aim to solve a specific armed conflict.

Definitions

Prior to an armed conflict occurring, peace processes can include the prevention of ...

for Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, culminating in the Transitional Authority; Hawke's Foreign Minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

Gareth Evans was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

for his role in negotiations. Hawke also took a major public stand after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre

The Tiananmen Square protests, known within China as the June Fourth Incident, were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China, lasting from 15 April to 4 June 1989. After weeks of unsuccessful attempts between t ...

; despite having spent years trying to get closer relations with China, Hawke gave a tearful address on national television describing the massacre in graphic detail, and unilaterally offered asylum to over 42,000 Chinese students who were living in Australia at the time, many of whom had publicly supported the Tiananmen protesters. Hawke did so without even consulting his Cabinet, stating later that he felt he simply had to act.

The Hawke government pursued a close relationship with the United States, assisted by Hawke's close friendship with US Secretary of State George Shultz

George Pratt Shultz ( ; December 13, 1920February 6, 2021) was an American economist, businessman, diplomat and statesman. He served in various positions under two different Republican presidents and is one of the only two persons to have held f ...

; this led to a degree of controversy when the Government supported the US's plans to test ballistic missiles off the coast of Tasmania in 1985, as well as seeking to overturn Australia's long-standing ban on uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

exports. Although the US ultimately withdrew the plans to test the missiles, the furore led to a fall in Hawke's approval ratings. Shortly after the 1990 election, Hawke would lead Australia into its first overseas military campaign since the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, forming a close alliance with US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed For ...

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

to join the coalition

A coalition is formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political, military, or economic spaces.

Formation

According to ''A G ...

in the Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

. The Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

contributed several destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s to the war effort, which successfully concluded in February 1991, with the expulsion of Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

i forces from Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

. The success of the campaign, and the lack of any Australian casualties, led to a brief increase in the popularity of the Government.

Through his role on the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM; or) is a wiktionary:biennial, biennial summit meeting of the List of current heads of state and government, governmental leaders from all Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth nations. ...

, Hawke played a leading role in ensuring the Commonwealth initiated an international boycott on foreign investment into South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, building on work undertaken by his predecessor Malcolm Fraser, and in the process clashing publicly with Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, who initially favoured a more cautious approach. The resulting boycott, led by the Commonwealth, was widely credited with helping bring about the collapse of apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

, and resulted in a high-profile visit by Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

in October 1990, months after the latter's release from a 27-year stint in prison. During the visit, Mandela publicly thanked the Hawke government for the role it played in the boycott.

Election wins and leadership challenges

Hawke benefited greatly from the disarray into which the Liberal Party fell after the resignation of Fraser following the 1983 election. The Liberals were torn between supporters of the more conservative

Hawke benefited greatly from the disarray into which the Liberal Party fell after the resignation of Fraser following the 1983 election. The Liberals were torn between supporters of the more conservative John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

and the more liberal Andrew Peacock, with the pair frequently contesting the leadership. Hawke and Keating were also able to use the concealment of the size of the budget deficit by Fraser before the 1983 election to great effect, damaging the Liberal Party's economic credibility as a result.

However, Hawke's time as Prime Minister also saw friction develop between himself and the grassroots of the Labor Party, many of whom were unhappy at what they viewed as Hawke's iconoclasm and willingness to cooperate with business interests. Hawke regularly and publicly expressed his willingness to cull Labor's "sacred cows". The Labor Left

The Labor Left (LL), also known as the Progressive Left, Socialist Left or simply the Left, is one of the two major political factions within the Australian Labor Party (ALP). It is nationally characterised by social progressivism and democra ...

faction, as well as prominent Labor backbencher Barry Jones, offered repeated criticisms of a number of government decisions. Hawke was also subject to challenges from some former colleagues in the trade union movement over his "confrontationalist style" in siding with the airline companies in the 1989 Australian pilots' strike.

Nevertheless, Hawke was able to comfortably maintain a lead as preferred prime minister in the vast majority of opinion polls carried out throughout his time in office. He recorded the highest popularity rating ever measured by an Australian opinion poll, reaching 75% approval in 1984. After leading Labor to a comfortable victory in the snap 1984 election, called to bring the mandate of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

back in line with the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, Hawke was able to secure an unprecedented third consecutive term for Labor with a comfortable victory in the double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks in the bicameral Parliament of Australia between the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). A double dissolutio ...

election of 1987

Events January

* January 1 – Bolivia reintroduces the Boliviano currency.

* January 2 – Chadian–Libyan conflict – Battle of Fada: The Military of Chad, Chadian army destroys a Libyan armoured brigade.

* January 3 – Afghan leader ...

. Hawke was subsequently able to lead the nation in the bicentennial __NOTOC__

A bicentennial or bicentenary is the two-hundredth anniversary of a part, or the celebrations thereof. It may refer to:

Europe

* French Revolution bicentennial, commemorating the 200th anniversary of 14 July 1789 uprising, celebrated ...

celebrations of 1988, culminating with him welcoming Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

to open the newly constructed Parliament House.

The late-1980s recession, and the accompanying high interest rates, saw the Government fall in opinion polls, with many doubting that Hawke could win a fourth election. Keating, who had long understood that he would eventually succeed Hawke as prime minister, began to plan a leadership change; at the end of 1988, Keating put pressure on Hawke to retire in the new year. Hawke rejected this suggestion but reached a secret agreement with Keating, the so-called " Kirribilli Agreement", stating that he would step down in Keating's favour at some point after the 1990 election. Hawke subsequently won that election, in the process leading Labor to a record fourth consecutive electoral victory, albeit by a slim margin. Hawke appointed Keating as deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a Minister (government), government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to th ...

to replace the retiring Lionel Bowen.

By the end of 1990, frustrated by the lack of any indication from Hawke as to when he might retire, Keating made a provocative speech to the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery. Hawke considered the speech disloyal, and told Keating he would renege on the Kirribilli Agreement as a result. After attempting to force a resolution privately, Keating finally resigned from the Government in June 1991 to challenge Hawke for the leadership. His resignation came soon after Hawke vetoed in Cabinet a proposal backed by Keating and other ministers for mining to take place at Coronation Hill in Kakadu National Park

Kakadu National Park is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia, southeast of Darwin. It is a World Heritage Site. Kakadu is also gazetted as a locality, covering the same area as the national park, with 313 people recorded l ...

. Hawke won the leadership spill, and in a press conference after the result, Keating declared that he had fired his "one shot" on the leadership. Hawke appointed John Kerin to replace Keating as Treasurer.

Despite his victory in the June spill, Hawke quickly began to be regarded by many of his colleagues as a "wounded" leader; he had now lost his long-term political partner, his ratings in opinion polls were beginning to fall significantly, and after nearly nine years as Prime Minister, there was speculation that it would soon be time for a new leader. Hawke's leadership was ultimately irrevocably damaged at the end of 1991; after Liberal Leader John Hewson released ' Fightback!', a detailed proposal for sweeping economic change, including the introduction of a goods and services tax, Hawke was forced to sack Kerin as Treasurer after the latter made a public gaffe attempting to attack the policy. Keating duly challenged for the leadership a second time on 19 December, arguing that he would be better placed to defeat Hewson; this time, Keating succeeded, narrowly defeating Hawke by 56 votes to 51.

In a speech to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

following the vote, Hawke declared that his nine years as prime minister had left Australia a better and wealthier country, and he was given a standing ovation by those present. He subsequently tendered his resignation to the Governor-General and pledged support to his successor. Hawke briefly returned to the backbench, before resigning from Parliament on 20 February 1992, sparking a by-election