Bnot Ya'akov Bridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Daughters of Jacob Bridge (, ) is a bridge that spans the last natural ford of the

165

ff The bridge currently in civilian use was built in 2007. Within the vicinity of the ford is the location of a well known

261

/ref> and was the site of the Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub during

In the late Mamluk period, Sefad became a principal town and

In the late Mamluk period, Sefad became a principal town and

182−183

/ref> Edward Robinson noted that during the 14th century, travellers crossed the river Jordan below the Lake of Tiberias, while the first crossing in the area of ''Jisr Benat Yakob'' was noted in 1450 CE. The khan, at the eastern end of the bridge, and the bridge itself, were both probably built before 1450, according to Robinson. For the year 1555−1556 CE ( AH 963) the toll post at the bridge collected 25,000

The Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub was fought there on 27 September 1918 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of

The Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub was fought there on 27 September 1918 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of

77

ff. *

341

��344) * * *Murray, Alan V. editor. (2006), ''The Crusades: An Encyclopaedia'', * * * * * * * * * * * * *

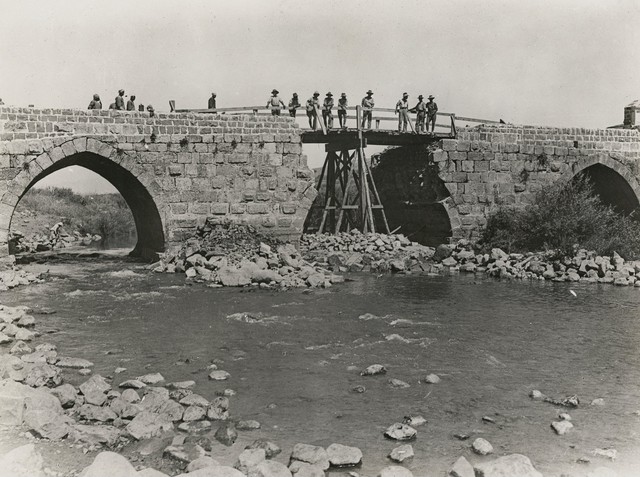

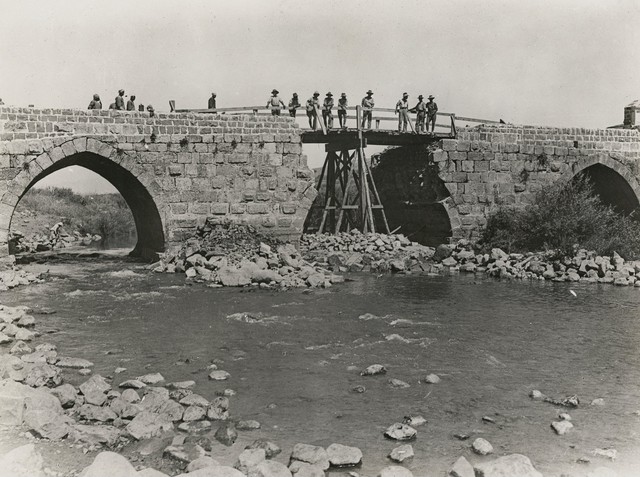

IAAWikimedia commonsBridge at Jisr Banat Ya'qub

12th-century bridge pictured early 20th century.

80th Brigade's Battles in the Six-Day War

Paratroopers Brigade website.

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov Acheulian Site Project

{{Authority control Bridges over the Jordan River Crusade places Hula Valley Mamluk architecture in Israel

Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains to the Dead ...

between the Korazim Plateau in northern Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

.

The area has been used as a crossing point for thousands of years; it was part of the recently dubbed Via Maris

Via Maris, or Way of Horus () was an ancient trade route, dating from the early Bronze Age, linking Egypt with the northern empires of Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia – along the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Egypt, Israel, Turkey and S ...

, and was strategically important to the Ancient Egyptians

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower ...

, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

ns, Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

, Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

(early Muslims), Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

, Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish ori ...

, Mamluks

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-sold ...

, Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

, and to modern inhabitants and armies who crossed the river at this place.

The site was named Jacob's Ford () by Europeans during the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. A stone bridge was built by the Mamluks sometime in the 13th century, who called it (). The medieval bridge was replaced in 1934 by a modern bridge further south during the draining of Lake Hula

The Hula Valley () is a valley and fertile agriculture, agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water that used to be Lake Hula before it was drained. It is a major stopover for birds migrating along the Great Rift Valley be ...

.Sufian, 2008, pp165

ff The bridge currently in civilian use was built in 2007. Within the vicinity of the ford is the location of a well known

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

archaeological site with Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with ''Homo ...

artifacts dated to around 780,000 years ago.

Located southwest of the medieval bridge are the remains of a crusader castle known as Chastelet and east of the bridge are the remains of a Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

khan (caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was an inn that provided lodging for travelers, merchants, and Caravan (travellers), caravans. They were present throughout much of the Islamic world. Depending on the region and period, they were called by a ...

). The old arched stone bridge marked the northernmost limit of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's campaign in Syria,Preston, 1921, p261

/ref> and was the site of the Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub during

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

The bridge is now part of the Israeli Highway 91 and straddles the border between the Galilee and the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

. It is of strategic military significance as it is one of the few fixed crossing points over the upper Jordan River that enable access from the Golan Heights to the Upper Galilee

The Upper Galilee (, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; , ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Part of the larger Galilee region, it is characterized by its higher elevations and mountainous terra ...

.

Etymology

The place was first associated with thebiblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

forefather of the Jews, Jacob

Jacob, later known as Israel, is a Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions. He first appears in the Torah, where he is described in the Book of Genesis as a son of Isaac and Rebecca. Accordingly, alongside his older fraternal twin brother E ...

, due to a confusion. The Crusader-era nunnery

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican Comm ...

of Saint James ( in French), from the nearby castellany

A castellan, or constable, was the governor of a castle in medieval Europe. Its surrounding territory was referred to as the castellany. The word stems from . A castellan was almost always male, but could occasionally be female, as when, in 1 ...

of Sephet (modern-day Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

), received part of the customs paid at the ford, and since is derived from Jacob

Jacob, later known as Israel, is a Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions. He first appears in the Torah, where he is described in the Book of Genesis as a son of Isaac and Rebecca. Accordingly, alongside his older fraternal twin brother E ...

, this led to the name Jacob's Ford.

History and archaeology of the ford site

Prehistory

Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

excavations at the prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov site have revealed evidence of human habitation in the area, from as early as 750,000 years ago. Archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; ) is an Israeli public university, public research university based in Jerusalem. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann in July 1918, the public university officially opened on 1 April 1925. ...

claim that the site provides evidence of "advanced human behavior" half a million years earlier than has previously been estimated as possible. Their report describes a layer at the site belonging to the Acheulian

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with ''Homo ...

(a culture dating to the Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears ...

, at the very beginning of the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

), where numerous stone tools, animal bones and plant remains have been found, including those of the large elephant '' Palaeoloxodon recki'' which is associated with stone tools, including a handaxe

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by kna ...

, and shows cut and fracture marks indicating that it was butchered by archaic humans

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively calle ...

. According to the archaeologists Paul Pettitt and Mark White, the site has produced the earliest widely accepted evidence for the use of fire, dated approximately 790,000 years ago. A Tel-Aviv University

Tel Aviv University (TAU) is a Public university, public research university in Tel Aviv, Israel. With over 30,000 students, it is the largest university in the country. Located in northwest Tel Aviv, the university is the center of teaching and ...

study found remains of a huge carp

The term carp (: carp) is a generic common name for numerous species of freshwater fish from the family (biology), family Cyprinidae, a very large clade of ray-finned fish mostly native to Eurasia. While carp are prized game fish, quarries and a ...

fish cooked with the use of fire at the site 780,000 years ago.

Crusader and Ayyubid period

Jacob's Ford was a key river crossing point and major trade route betweenAcre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

and Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

. It was utilized by Christian Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and Seljuk Seljuk (, ''Selcuk'') or Saljuq (, ''Saljūq'') may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* S ...

Syria as a major intersection between the two civilizations, making it strategically important. When Humphrey II of Toron Humphrey II of Toron (1117 – 22 April 1179) was lord of Toron and constable of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. He was the son of Humphrey I of Toron.

Biography

Humphrey had become lord of Toron sometime before 1140 when he married the daughter of ...

was besieged in the city of Banyas in 1157, King Baldwin III of Jerusalem

Baldwin III (1130 – 10 February 1163) was the king of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Queen Melisende and King Fulk. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he eventu ...

was able to break the siege, only to be ambushed at Jacob's Ford in June of that year.

Later in the twelfth century, Baldwin IV of Jerusalem

Baldwin IV (1161–1185), known as the Leper King, was the king of Jerusalem from 1174 until his death in 1185. He was admired by historians and his contemporaries for his dedication to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the face of his debilitating ...

and Saladin continually contested the area around Jacob's Ford. Baldwin allowed the Templars to build Chastelet castle overlooking Jacob's Ford known to the Arabs as ''Qasr al-'Ata'' commanding the road from Quneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; , ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in south-western Syria. It is situated in a high valley in the Golan ...

to Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

. On 23 August 1179, Saladin successfully conducted the siege of Jacob's Ford

The siege of Jacob's Ford was a victory of the Muslim Sultan Saladin over the Christian King of Jerusalem, Baldwin IV. It occurred in August 1179, when Saladin conquered and destroyed Chastelet, a new border castle built by the Knights Temp ...

, destroying the unfinished fortification, known as the castle of Vadum Iacob or Chastellet.

Mamluk and Ottoman bridge

In the late Mamluk period, Sefad became a principal town and

In the late Mamluk period, Sefad became a principal town and Baibars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari (; 1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), commonly known as Baibars or Baybars () and nicknamed Abu al-Futuh (, ), was the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, of Turkic Kipchak origin, in the Ba ...

' postal road from Cairo to Damascus was extended with a branch that went through the north of Palestine. To accomplish this, the bridge was built over the Crusaders' Vadum Jacob (Jacob's ford). The bridge had the Mamluk characteristic dual-slope pathway like the Yibna Bridge. Al-Dimashqi (1256–1327) noted that "the Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

traverses the district of ''Al Khaitah'' and comes to the ''Jisr Ya'kub'' (''lit.'' "Jacob's Bridge"), under ''Kasr Ya'kub'' (''lit.'' "Jacob's Castle"), and reaching the Sea of Tiberias

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth and the second-lowest la ...

, falls into it."

Before 1444, a merchant constructed a khan (caravanserai) on the eastern side of the bridge, one of a series of such khans built at the time.Petersen, 1991, pp182−183

/ref> Edward Robinson noted that during the 14th century, travellers crossed the river Jordan below the Lake of Tiberias, while the first crossing in the area of ''Jisr Benat Yakob'' was noted in 1450 CE. The khan, at the eastern end of the bridge, and the bridge itself, were both probably built before 1450, according to Robinson. For the year 1555−1556 CE ( AH 963) the toll post at the bridge collected 25,000

akçe

The ''akçe'' or ''akça'' (anglicized as ''akche'', ''akcheh'' or ''aqcha''; ; , , in Europe known as '' asper'') was a silver coin mainly known for being the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire. It was also used in other states includi ...

, and in 1577 (985 H) a firman

A firman (; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods such firmans were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The English word ''firman'' co ...

commanded that the place had post horses ready.

On June 4th 1771, a combined force of Zahir al Umar's men and mamluk commander Abu al-Dhahab

Muhammad Abu al-Dhahab (; 1735–1775), also just called Abu Dhahab (, a name apparently given to him on account of his generosity and wealth) was a Mamluk emir and regent of Ottoman Egypt.

Born in the North Caucasus region of Circassia ...

met the Damascene Pasha in battle, The result was a victory for the Zayadina coalition and established control of Irbid

Irbid (), known in ancient times as Arabella or Arbela (Άρβηλα in Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek), is the capital and largest city of Irbid Governorate. It has the second-largest metropolitan population in Jordan after Amman, with a ...

and Quneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; , ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in south-western Syria. It is situated in a high valley in the Golan ...

to Zahir al Umar. This also set in motion the later Final Invasion of Damascus Eyalet & Siege of Damascus by Abu al-Dhahab

The bridge was maintained through the Ottoman period, with a caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was an inn that provided lodging for travelers, merchants, and Caravan (travellers), caravans. They were present throughout much of the Islamic world. Depending on the region and period, they were called by a ...

on one end of the bridge, as shown in the 1799 Jacotin map. During the Egyptian campaign of 1799, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

sent his cavalry commander, general Murat

Murat may refer to:

Places Australia

* Murat Bay, a bay in South Australia

* Murat Marine Park, a marine protected area

France

* Murat, Allier, a commune in the department of Allier

* Murat, Cantal, a commune in the department of Cantal

Elsew ...

, to defend the bridge, as a measure of preempting reinforcement from Damascus being sent to Akko

Acre ( ), known in Hebrew as Akko (, ) and in Arabic as Akka (, ), is a city in the coastal plain region of the Northern District of Israel.

The city occupies a strategic location, sitting in a natural harbour at the extremity of Haifa Bay on ...

during the siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

laid by the French. Murat occupied nearby Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

and Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

, as well as the bridge and, by relying on the superior quality of French troops, managed to defeat Turkish units far outnumbering him. Jacotin's map marks the west side of the bridge with the name of General Murat and the date of 2 April 1799.

In 1881, the PEF's ''Survey of Western Palestine'' (SWP) also noted about ''Jisr Benat Yakub'': "The bridge itself appears to be of later date than the Crusader period."

20th century

The Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub was fought there on 27 September 1918 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of

The Battle of Jisr Benat Yakub was fought there on 27 September 1918 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, at the beginning of the pursuit by the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

of the retreating remnants of the Ottoman Yildirim Army Group

The Yıldırım Army Group or Thunderbolt Army Group of the Ottoman Empire or Army Group F (German: ''Heeresgruppe F'') was an Army Group of the Ottoman Army during World War I. While being an Ottoman unit, it also contained the German Asia Cor ...

towards Damascus, who destroyed the central arch of the bridge. The bridge was shortly repaired by ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was originally a First World War army corps of the British Empire under the command of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the ...

sappers, flattening the original dual-slope pathway, making it useful for modern vehicles.

In 1934, during the draining of Lake Hula as part of a Zionist land reclamation

Land reclamation, often known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new Terrestrial ecoregion, land from oceans, list of seas, seas, Stream bed, riverbeds or lake ...

project, the old bridge was replaced by a modern one further south.

On the "Night of the Bridges

The Night of the Bridges (formally Operation Markolet) was a Haganah venture on the night of 16 to 17 June 1946 in the British Mandate of Palestine, as part of the Jewish insurgency in Palestine (1944–47). Its aim was to destroy eleven brid ...

" between 16 and 17 June 1946, the bridge was again destroyed by the Jewish Haganah

Haganah ( , ) was the main Zionist political violence, Zionist paramilitary organization that operated for the Yishuv in the Mandatory Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine. It was founded in 1920 to defend the Yishuv's presence in the reg ...

. The Syrians captured the bridge on June 11, 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, but later withdrew as a result of the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,National Water Carrier of Israel

image:National Water Carrier of Israel -en.svg, National Water Carrier of Israel

The National Water Carrier of Israel (, ''HaMovil HaArtzi'') is the largest water project in Israel, completed in 1964. Its main purpose is to transfer water from ...

, but after US pressure, the intake was moved downstream to the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic languages, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth ...

at Eshed Kinrot,Sosland, 2007, p. 70 which later became known as the Sapir Pumping Station at Tel Kinrot/Tell el-'Oreimeh.

During the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, an Israeli paratrooper

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light infa ...

brigade captured the area, and after the war, the Israeli Combat Engineering Corps constructed a Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, Prefabrication, pre-fabricated, Truss Bridge, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British Empire in World War II, British for military use during the World War II, Second World War and saw ...

. In the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states led by Egypt and S ...

, Syrian forces approached the vicinity of the bridge. As a precaution, Israeli sappers placed explosives on the bridge but did not detonate them as the Syrians did not attempt to cross it.

21st century

In 2007, one of the two Bailey bridges at the site (one for traffic from east to west and the other handling traffic in the opposite direction) was replaced with a modern concrete span, while the other Bailey bridge was left intact for emergency use.See also

*Archaeology of Israel

The archaeology of Israel is the study of the archaeology of the present-day Israel, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. The ancient Land of Israel was a geographical bridge between the political and cultu ...

and Levantine archaeology

Levantine archaeology is the archaeological study of the Levant. It is also known as Syro-Palestinian archaeology or Palestinian archaeology (particularly when the area of inquiry centers on ancient Palestine (region), PalestineOn page 16 of his ...

* Barid, Muslim postal network renewed during Mamluk period (roads, bridges, khans)

**Jisr al- Ghajar, stone bridge south of Ghajar

** Al-Sinnabra Crusader bridge, with nearby Jisr Umm el-Qanatir/Jisr Semakh and Jisr es-Sidd further downstream

** Jisr al-Majami bridge over the Jordan, with Mamluk khan

** Jisr Jindas bridge over the Ayalon near Lydda and Ramla

** Yibna Bridge or "Nahr Rubin Bridge"

** Isdud Bridge (Mamluk, 13th century) outside Ashdod/Isdud

** Jisr ed-Damiye, bridges over the Jordan (Roman, Mamluk, modern)

* Bir Ma'in, Arab village near Ramle, connected by a foundation legend to Jacob/Ya'kub and Daughters of Jacob Bridge/Jisr Benat Ya'kub.Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, vol 2, pp77

ff. *

Jacob's Well

Jacob's Well, also known as Jacob's Fountain or the Well of Shechem, Sychar, is a List of Christian holy sites in the Holy Land, Christian holy site located in Balata village, a suburb of the State of Palestine, Palestinian city of Nablus in t ...

, site associated with biblical Jacob in Samaritan and Christian tradition

* Jubb Yussef (Joseph's Well), site associated with biblical Joseph in Muslim tradition

References

Bibliography

* * * * (pp341

��344) * * *Murray, Alan V. editor. (2006), ''The Crusades: An Encyclopaedia'', * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

*Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4IAA

12th-century bridge pictured early 20th century.

80th Brigade's Battles in the Six-Day War

Paratroopers Brigade website.

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov Acheulian Site Project

{{Authority control Bridges over the Jordan River Crusade places Hula Valley Mamluk architecture in Israel