Blakeney Point on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Blakeney Point (designated as Blakeney National Nature Reserve) is a national nature reserve situated near to the villages of Blakeney, Morston and

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

Port of Cley and Blakeney

in appendix to Blakeney's shipping trade benefited from the silting up of its nearby rival, and in 1817 the channel to the Haven was deepened to improve access.

In the decades preceding

In the decades preceding

Blakeney Point has been designated as one of the most important sites in Europe for nesting terns by the government's

Blakeney Point has been designated as one of the most important sites in Europe for nesting terns by the government's

Blakeney Point has a mixed colony of about 500

Blakeney Point has a mixed colony of about 500

Grasses such as sea couch grass and sea poa grass have an important function in the driest areas of the marshes, and on the coastal dunes, where

Grasses such as sea couch grass and sea poa grass have an important function in the driest areas of the marshes, and on the coastal dunes, where

The 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million who made overnight stays on the Norfolk coast in 1999 are estimated to have spent £122 million, and secured the equivalent of 2,325 full-time jobs in that area. A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites, including Blakeney, Cley and Morston found that 39 per cent of visitors gave

The 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million who made overnight stays on the Norfolk coast in 1999 are estimated to have spent £122 million, and secured the equivalent of 2,325 full-time jobs in that area. A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites, including Blakeney, Cley and Morston found that 39 per cent of visitors gave

The spit is a relatively young feature in

The spit is a relatively young feature in

North Norfolk Coast

in May (2003) pp. 1–19. The northernmost part of Snitterley (now Blakeney) village was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.Muir (2008) p. 103. In the last two hundred years, maps have been accurate enough for the distance from the Blakeney Chapel ruins to the sea to be measured. The in 1817 had become by 1835, in 1907, and by the end of the 20th century. The spit is moving towards the mainland at about per year;Gray (2004) pp. 363–365. and several former raised islands or "eyes" have already disappeared, first covered by the advancing shingle, and then lost to the sea. The massive 1953 flood overran the main beach, and only the highest dune tops remained above water. Sand was washed into the salt marshes, and the extreme tip of the point was breached, but as with other purely natural parts of the coast, like Scolt Head Island, little lasting damage was done.Allison H & Morley J in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 7–8. Landward movement of the shingle meant that the channel of the Glaven was becoming blocked increasingly often by 2004. This led to flooding of Cley village and the environmentally important Blakeney freshwater marshes. The

Open Street MapOfficial website: Blakeney National Nature Reserve

{{Authority control Blakeney, Norfolk Coastal features of Norfolk Landforms of Norfolk National nature reserves in England National Trust properties in Norfolk Nature reserves in Norfolk North Norfolk Spits of England Special Protection Areas in England Beaches of Norfolk Protected areas established in 1912

Cley next the Sea

Cley next the Sea (, ) is a village and civil parish on the River Glaven in the England, English county of Norfolk, England, Norfolk.

Cley next the Sea is located north-west of Holt, Norfolk, Holt and north-west of Norwich.

History

The vil ...

on the north coast of Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, England. Its main feature is a spit of shingle and sand dunes

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat ...

, but the reserve also includes salt marsh

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. I ...

es, tidal mudflats and reclaimed farmland. It has been managed by the National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

since 1912, and lies within the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest

The North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is an area of European importance for wildlife in Norfolk, England. It comprises 7,700 ha (19,027 acres) of the county's north coast from just west of Holme-next-the-Se ...

, which is additionally protected through Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a network of nature protection areas in the territory of the European Union. It is made up of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas designated under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive, respectiv ...

, Special Protection Area

A special protection area (SPA) is a designation under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds. Under the Directive, Member States of the European Union (EU) have a duty to safeguard the habitats of migratory birds and cer ...

(SPA), International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

(IUCN) and Ramsar listings. The reserve is part of both an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is one of 46 areas of countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Since 2023, the areas in England an ...

(AONB), and a World Biosphere Reserve

The UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR) covers internationally designated protected areas, known as biosphere or nature reserves, which are meant to demonstrate a balanced relationship between people and nature (e.g. encourage sust ...

. The Point has been studied for more than a century, following pioneering ecological

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

studies by botanist Francis Wall Oliver

Francis Wall Oliver FRS (10 May 1864 – 14 September 1951) was an English botanist whose interests evolved from plant anatomy to palaeobotany to ecology.

Oliver was from a Quaker (Society of Friends) family and was educated first at the Friends ...

and a bird ringing

Bird ringing (UK) or bird banding (US) is the attachment of a small, individually numbered metal or plastic tag to the leg or wing of a wild bird to enable individual identification. This helps in keeping track of the movements of the bird an ...

programme initiated by ornithologist Emma Turner.

The area has a long history of human occupation; ruins of a medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

and "Blakeney Chapel

Blakeney Chapel is a ruined building on the coast of North Norfolk, England. Despite its name, it was probably not a chapel, nor is it in the adjoining village of Blakeney, Norfolk, Blakeney, but rather in the parish of Cley next the Sea. The ...

" (probably a domestic dwelling) are buried in the marshes. The towns sheltered by the shingle spit were once important harbours, but land reclamation

Land reclamation, often known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new Terrestrial ecoregion, land from oceans, list of seas, seas, Stream bed, riverbeds or lake ...

schemes starting in the 17th century resulted in the silting up of the river channels. The reserve is important for breeding birds, especially tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae, subfamily Sterninae, that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated in eleven genera in a subgroup of the family Laridae, which also ...

s, and its location makes it a major site for migrating birds

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

in autumn. Up to 500 seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

may gather at the end of the spit, and its sand and shingle hold a number of specialised invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s and plants, including the edible samphire

Samphire is a name given to a number of succulent salt-tolerant plants (halophytes) that tend to be associated with water bodies.

* Rock samphire ('' Crithmum maritimum'') is a coastal species with white flowers that grows in Ireland, the Uni ...

, or "sea asparagus".

The many visitors who come to birdwatch, sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

or for other outdoor recreations are important to the local economy, but the land-based activities jeopardize nesting birds and fragile habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

s, especially the dunes. Some access restrictions on humans and dogs help to reduce the adverse effects, and trips to see the seals are usually undertaken by boat. The spit is a dynamic structure, gradually moving towards the coast and extending to the west. Land is lost to the sea as the spit rolls forward. The River Glaven

The River Glaven in the eastern English county of Norfolk is long and flows through picturesque North Norfolk countryside to the North Sea. Rising from a tiny headwater in Bodham the river starts miles before Selbrigg Pond where three small ...

can become blocked by the advancing shingle and cause flooding of Cley village, Cley Marshes nature reserve, and the environmentally important reclaimed grazing pastures, so the river has to be realigned every few decades.

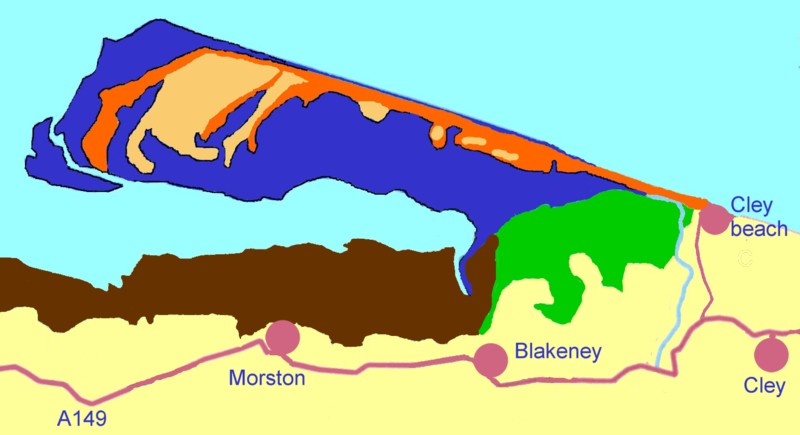

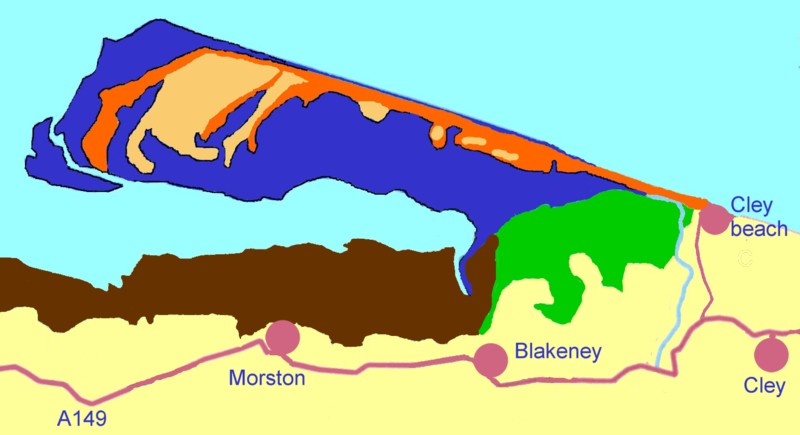

Description

Blakeney Point, like most of the northern part of the marshes in this area, is part of the parish ofCley next the Sea

Cley next the Sea (, ) is a village and civil parish on the River Glaven in the England, English county of Norfolk, England, Norfolk.

Cley next the Sea is located north-west of Holt, Norfolk, Holt and north-west of Norwich.

History

The vil ...

. The main spit runs roughly west to east, and joins the mainland at Cley Beach before continuing onwards as a coastal ridge to Weybourne. It is approximately long, and is composed of a shingle bank which in places is in width and up to high. It has been estimated that there are 2.3 million m3 (82 million ft3) of shingle in the spit, 97 per cent of which is derived from flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

.Steers, J A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 24.

The Point was formed by longshore drift

Longshore drift from longshore current is a geological process that consists of the transportation of sediments (clay, silt, pebbles, sand, shingle, shells) along a coast parallel to the shoreline, which is dependent on the angle of incoming w ...

and this movement continues westward; the spit lengthened by between 1886 and 1925. At the western end, the shingle curves south towards the mainland. This feature has developed several times over the years, giving the impression from the air of a series of hooks along the south side of the spit.Tansley (1939) pp. 848–849. Salt marshes

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open Seawater, saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the ti ...

have formed between the shingle curves and in front of the coasts sheltered by the spit, and sand dunes

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat ...

have accumulated at the Point's western end. Some of the shorter side ridges meet the main ridge at a steep angle due to the southward movement of the latter.Steers, J A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 19. There is an area of reclaimed farmland, known as Blakeney Freshes, to the west of Cley Beach Road.

Norfolk Coast Path, an ancient long distance footpath

A long-distance trail (or long-distance footpath, track, way, greenway) is a longer recreational trail mainly through rural areas used for hiking, backpacking, cycling, equestrianism or cross-country skiing. They exist on all continents exce ...

, cuts across the south eastern corner of the reserve along the sea wall Sea Wall or The Sea Wall may refer to:

* Seawall, a constructed coastal defence

* Sea Wall, Guyana

* ''The Sea Wall'' (novel), 1950 French novel by Marguerite Duras

* ''The Sea Wall'' (film), 2008 film based on Duras' novel

See also

*'' This Ang ...

between the farmland and the salt marshes, and further west at Holme-next-the-Sea

Holme-next-the-Sea is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

Holme-next-the-Sea is located north-east of Hunstanton and north-west of Norwich.

History

Holme-next-the-Sea's name is of Anglo-Saxon origin and derives f ...

the trail joins Peddars Way

The Peddars Way is a long distance footpath that passes through Suffolk and Norfolk, England.

Route

The Peddars Way is 46 miles (74 km) long and follows the route of a Roman road. It has been suggested by more than one writer that it was ...

. Retrieved 7 June 2012. The tip of Blakeney Point can be reached by walking up the shingle spit from the car park at Cley Beach, or by boats from the quay at Morston. The boat gives good views of the seal colonies and avoids the long walk over a difficult surface. The National Trust has an information centre and tea room at the quay, Retrieved 16 August 2012. and a visitor centre on the Point. The centre was formerly a lifeboat station and is open in the summer months.Dorling Kindersley (2009) p. 214. Halfway House, or the Watch House, is a building from Cley Beach car park. Originally built in the 19th century as a look-out for smugglers

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations. More broadly, soc ...

, it was used in succession as a coast guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a Maritime Security Regimes, maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with cust ...

station, by the Girl Guides

Girl Guides (or Girl Scouts in the United States and some other countries) are organisations within the Scout Movement originally and largely still for girls and women only. The Girl Guides began in 1910 with the formation of Girlguiding, The ...

, and as a holiday let.

History

To 1912

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

, and has produced many significant archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

finds. Both modern

Modern may refer to:

History

*Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Philosophy ...

and Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

people were present in the area between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago, before the last glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate be ...

, and humans returned as the ice retreated northwards. The archaeological record is poor until about 20,000 years ago, partly because of the very cold conditions that existed then, but also because the coastline was much further north than at present. As the ice retreated during the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

(10,000–5,000 BCE), the sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

rose, filling what is now the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. This brought the Norfolk coastline much closer to its present line, so that many ancient sites are now under the sea in an area now known as Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

. Retrieved 18 September 2012.Robertson ''et al.'' (2005) pp. 9–22. Early Mesolithic flint tools with characteristic long blades up to Murphy (2009) p. 14. long found on the present-day coast at Titchwell Marsh

Titchwell Marsh is an English nature reserve owned and managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Located on the north coast of the county of Norfolk, between the villages of Titchwell and Thornham, Norfolk, Thornham, about ...

date from a time when it was from the sea. Other flint tools have been found dating from the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories ...

(50,000–10,000 BCE) to the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

(5,000–2,500 BCE).

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Blakeney's former Carmelite

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

friary

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which may ...

, founded in 1296 and dissolved in 1538, was built in such a location,Robertson ''et al.'' (2005) p. 36. and several fragments of plain roof tile and pantiles

The Pantiles is a Georgian colonnade in the town of Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England. Formerly known as "The Walks" and the (Royal) "Parade", it leads from the well that gave the town its name. The area, developed following the discove ...

dating back to the 13th century have been found near the site of its ruins.Robertson ''et al.'' (2005) p. 143. Originally on the south side of the Glaven, Blakeney Eye had a ditched enclosure during the 11th and 12th centuries, and a building known as "Blakeney Chapel

Blakeney Chapel is a ruined building on the coast of North Norfolk, England. Despite its name, it was probably not a chapel, nor is it in the adjoining village of Blakeney, Norfolk, Blakeney, but rather in the parish of Cley next the Sea. The ...

", which was occupied from the 14th century to around 1600, and again in the late 17th century. Despite its name, it is unlikely that it had a religious function. Nearly a third of the mostly 14th- to 16th-century pottery found within the larger and earlier of the two rooms was imported from the continent,Birks (2003) pp. 1–28. suggesting significant international trade at this time.Robinson (2006) pp. 3–5.Pevsner & Wilson (2002) pp. 394–397.

The spit sheltered the Glaven ports, Blakeney, Cley-next-the-Sea and Wiveton

Wiveton is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the west bank of the River Glaven, inland from the coast and directly across the river from the village of Cley next the Sea. The larger village of Bl ...

, which were important medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

harbours. Blakeney sent ships to help Edward I's war efforts in 1301, and between the 14th and 16th centuries it was the only Norfolk port between King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is north-east of Peterborough, north-north-east of Cambridg ...

and Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

to have customs officials. Blakeney Church has a second tower at its east end, an unusual feature in a rural parish church. It has been suggested that it acted as a beacon for mariners, Retrieved 10 September 2011. perhaps by aligning it with the taller west tower to guide ships into the navigable channel between the inlet's sandbanks; that this was not always successful is demonstrated by a number of wrecks in the haven

Haven or The Haven may refer to:

* Harbor or haven, a sheltered body of water where ships can be docked

Arts and entertainment

Fictional characters

* Haven (Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter), from the novel series

* Haven (comics), from the ''X-Men ...

, including a carvel-built

Carvel built or carvel planking is a method of boat building in which hull planks are laid edge to edge and fastened to a robust frame, thereby forming a smooth surface. Traditionally the planks are neither attached to, nor slotted into, each ...

wooden ship.

Land reclamation

Land reclamation, often known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new Terrestrial ecoregion, land from oceans, list of seas, seas, Stream bed, riverbeds or lake ...

schemes, especially those by Henry Calthorpe in 1640 just to the west of Cley, led to the silting up of the Glaven shipping channel and relocation of Cley's wharf

A wharf ( or wharfs), quay ( , also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more Berth (mo ...

. Further enclosure in the mid-1820s aggravated the problem, and also allowed the shingle ridge at the beach to block the former tidal channel to the Salthouse marshes to the east of Cley. In an attempt to halt the decline, Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford (9 August 1757 – 2 September 1834) was a Scottish civil engineer. After establishing himself as an engineer of road and canal projects in Shropshire, he designed numerous infrastructure projects in his native Scotland, as well ...

was consulted in 1822, but his recommendations for reducing the silting were not implemented, and by 1840 almost all of Cley's trade had been lost.Pevsner & Wilson (2002) p. 435. The population stagnated, and the value of all property decreased sharply.Hume, Joseph.Port of Cley and Blakeney

in appendix to Blakeney's shipping trade benefited from the silting up of its nearby rival, and in 1817 the channel to the Haven was deepened to improve access.

Packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed mainly for domestic mail and freight transport in European countries and in North American rivers and canals. Eventually including basic passenger accommodation, they were used extensively during t ...

s ran to Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

and London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

from 1840, but this trade declined as ships became too large for the harbour.

National Trust era

In the decades preceding

In the decades preceding World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, this stretch of coast became famous for its wildfowling

Waterfowl hunting is the practice of hunting Water bird, aquatic birds such as ducks, geese and other Anseriformes, waterfowls or Wader, shorebirds for sport and meat. Waterfowl are hunted in crop fields where they feed, or in areas with bodies ...

; locals were looking for food, but some more affluent visitors hunted to collect rare birds;Bishop (1983) pp. 9–13. Norfolk's first barred warbler

The barred warbler (''Curruca nisoria'') is a typical warbler which breeds across temperate regions of central and eastern Europe and western and central Asia. This passerine bird is strongly migratory, and winters in tropical eastern Africa.De ...

was shot on the point in 1884. In 1901, the Blakeney and Cley Wild Bird Protection Society created a bird sanctuary and appointed as its "watcher", Bob Pinchen, the first of only six men, up to 2012, to hold that post.

In 1910, the owner of the Point, Augustus Cholmondeley Gough-Calthorpe, 6th Baron Calthorpe, leased the land to University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

(UCL), who also purchased the Old Lifeboat House at the end of the spit. When the baron died later that year, his heirs put Blakeney Point up for sale, raising the possibility of development.Ayres (2012) p. 123. In 1912, a public appeal initiated by Charles Rothschild

Nathaniel Charles Rothschild (9 May 1877 – 12 October 1923) was an English banker and entomologist and a member of the Rothschild family. He is remembered for 'the Rothschild List', a list he made in 1915 of 284 sites across Britain that he c ...

and organised by UCL Professor Francis Wall Oliver

Francis Wall Oliver FRS (10 May 1864 – 14 September 1951) was an English botanist whose interests evolved from plant anatomy to palaeobotany to ecology.

Oliver was from a Quaker (Society of Friends) family and was educated first at the Friends ...

and Dr Sidney Long enabled the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe estate, and the land was then donated to the National Trust. UCL established a research centre at the Old Lifeboat House in 1913, where Oliver and his college pioneered the scientific study of Blakeney Point. The building is still used by students, and also acts as an information centre. Despite formal protection, the tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae, subfamily Sterninae, that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated in eleven genera in a subgroup of the family Laridae, which also ...

colony was not fenced off until the 1960s.

In 1930, the Point's first "watcher", Bob Pinchen, retired and was replaced by Billy Eales, who had assisted Pinchen the previous summer to "learn the job". His son, Ted Eales, succeeded him as warden when he died in early 1939. Ted Eales went on to work as a wildlife cameraman for Anglia Television

ITV Anglia, previously known as Anglia Television, is the ITV franchise holder for the East of England. The station is based at Anglia House in Norwich, with regional news bureaux in Cambridge and Northampton. ITV Anglia is owned and operated b ...

during the winter and served as the Point's warden until retiring in March 1980. Subsequent wardens have included Joe Reed and wildlife presenter Ajay Tegala. Bob Pinchen, Ted Eales and Ajay Tegala have all written books about their experiences on Blakeney Point as watcher, warden and ranger respectively.

The Point was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain, or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle ...

(SSSI) in 1954, along with the adjacent Cley Marshes reserve, and subsumed into the newly created North Norfolk Coast SSSI in 1986. The larger area is now additionally protected through Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a network of nature protection areas in the territory of the European Union. It is made up of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas designated under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive, respectiv ...

, Special Protection Area

A special protection area (SPA) is a designation under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds. Under the Directive, Member States of the European Union (EU) have a duty to safeguard the habitats of migratory birds and cer ...

(SPA) and Ramsar listings, IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

category IV (habitat/species management area) and is part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Retrieved 8 November 2011. The Point became a National Nature Reserve (NNR) in 1994, and the coast from Holkham NNR to Salthouse, together with Scolt Head Island

Scolt Head Island is an offshore barrier island between Brancaster and Wells-next-the-Sea in north Norfolk. It is in the parish of Burnham Norton and is accessed by a seasonal ferry from the village of Overy Staithe. The shingle and sand islan ...

, became a Biosphere Reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, funga, or features of geologic ...

in 1976.Liley (2008) pp. 4–6.

Fauna and flora

Birds

Blakeney Point has been designated as one of the most important sites in Europe for nesting terns by the government's

Blakeney Point has been designated as one of the most important sites in Europe for nesting terns by the government's Joint Nature Conservation Committee

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) is the public body that advises the Government of the United Kingdom and devolved administrations on UK-wide and international nature conservation.

Originally established under the Environmental Pro ...

. In the early 1900s, the small colonies of common

Common may refer to:

As an Irish surname, it is anglicised from Irish Gaelic surname Ó Comáin.

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Com ...

and little tern

The little tern (''Sternula albifrons'') is a seabird of the family Laridae. It was first described by the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas in 1764 and given the binomial name ''Sterna albifrons''. It was moved to the genus '' Sternula'' whe ...

s were badly affected by egg-taking, disturbance and shooting, but as protection improved the common terns population rose to 2,000 pairs by mid-century, although it subsequently declined to no more than 165 pairs by 2000, perhaps due to predation. Sandwich tern

The Sandwich tern (''Thalasseus sandvicensis'') is a tern in the family Laridae. It is very closely related to the lesser crested tern (''T. bengalensis''), Chinese crested tern (''T. bernsteini''), Cabot's tern (''T. acuflavidus''), and el ...

s were a scarce breeder until the 1970s, but there were 4,000 pairs by 1992. Blakeney is the most important site in Britain for both Sandwich and little terns, the roughly 200 pairs of the latter species amounting to eight per cent of the British population. The 2,000 pairs of black-headed gull

The black-headed gull (''Chroicocephalus ridibundus'') is a small gull that breeds in much of the Palearctic in Europe and Asia, and also locally in smaller numbers in coastal eastern Canada. Most of the population is migratory and winters fu ...

s sharing the breeding area with the terns are believed to protect the colony as a whole from predators like red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe and Asia, plus ...

es. Other nesting birds include about 20 pairs of Arctic tern

The Arctic tern (''Sterna paradisaea'') is a tern in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar breeding distribution covering the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe (as far south as Brittany), Asia, and North America (as far south ...

s and a few Mediterranean gull

The Mediterranean gull (''Ichthyaetus melanocephalus'') is a small gull. The scientific name is from Ancient Greek. The genus ''Ichthyaetus'' is from ''ikhthus'', "fish", and ''aetos'', "eagle", and the specific ''melanocephalus'' is from ''mel ...

s in the tern colony, ringed plovers and oystercatchers

The oystercatchers are a group of waders forming the family Haematopodidae, which has a single genus, ''Haematopus''. They are found on coasts worldwide apart from the polar regions and some tropical regions of Africa and South East Asia. The e ...

on the shingle and common redshank

The common redshank or simply redshank (''Tringa totanus'') is a Eurasian wader in the large family Scolopacidae.

Taxonomy

The common redshank was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of hi ...

s on the salt marsh. The wader

245px, A flock of Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflats in order to foraging, ...

s' breeding success has been compromised by human disturbance and predation by gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the subfamily Larinae. They are most closely related to terns and skimmers, distantly related to auks, and even more distantly related to waders. Until the 21st century, most gulls were placed ...

s, weasels

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets, and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slender b ...

and stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine or ermine, is a species of mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern regions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Concern on th ...

s, with ringed plovers particularly affected, declining to 12 pairs in 2012 compared to 100 pairs twenty years previously. The pastures contain breeding northern lapwing

The northern lapwing (''Vanellus vanellus''), also known as the peewit or pewit, tuit or tewit, green plover, or (in Ireland and Great Britain) pyewipe or just lapwing, is a bird in the lapwing subfamily. It is common through temperate Palearcti ...

s, and species such as sedge

The Cyperaceae () are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as wikt:sedge, sedges. The family (biology), family is large; botanists have species description, described some 5,500 known species in about 90 ...

and reed warblers

The ''Acrocephalus'' warblers are small, insectivorous passerine birds belonging to the genus ''Acrocephalus''. Formerly in the paraphyletic Old World warbler assemblage, they are now separated as the namesake of the marsh and tree warbler famil ...

and bearded tit

The bearded reedling (''Panurus biarmicus'') is a small, long-tailed passerine bird found in reed beds near water in the temperate zone of Eurasia. It is frequently known as the bearded tit or the bearded parrotbill, as it historically was beli ...

s are found in patches of common reed

''Phragmites australis'', known as the common reed, is a species of flowering plant in the grass family Poaceae. It is a wetland grass that can grow up to tall and has a cosmopolitan distribution worldwide.

Description

''Phragmites australis' ...

. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

The Point juts into the sea on a north-facing coast, which means that migrant birds may be found in spring and autumn, sometimes in huge numbers when the weather conditions force them towards land. Numbers are relatively low in spring, but autumn can produce large "falls", such as the hundreds of European robin

The European robin (''Erithacus rubecula''), known simply as the robin or robin redbreast in the British Isles, is a small insectivorous passerine bird that belongs to the Old World flycatcher family Muscicapidae. It is found across Europe, ea ...

s on 1 October 1951 or more than 400 common redstart

The common redstart (''Phoenicurus phoenicurus''), or often simply redstart, is a small passerine bird in the genus '' Phoenicurus''. Like its relatives, it was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family, (Turdidae), but is now known to be ...

s, on 18 September 1995. The common birds are regularly accompanied by scarcer species like greenish warbler

The greenish warbler (''Phylloscopus trochiloides'') is a widespread leaf warbler with a breeding range in northeastern Europe, and temperate to subtropical continental Asia. This warbler is strongly bird migration, migratory and Winter, winters ...

s, great grey shrike

The great grey shrike (''Lanius excubitor'') is a large and predatory songbird species in the shrike family (biology), family (Laniidae). It forms a superspecies with its parapatric southern relatives, the Iberian grey shrike (''L. meridionalis' ...

s or Richard's pipit

Richard's pipit (''Anthus richardi'') is a medium-sized passerine bird which breeds in open grasslands in the East Palearctic. It is a long-distance bird migration, migrant moving to open lowlands in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It ...

s. Seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

s may be sighted passing the Point, and migrating waders feed on the marshes at this time of year. Vagrant rarities have turned up when the weather is appropriate, including a Fea's or Zino's petrel

Zino's petrel (''Pterodroma madeira'') or the freira, is a species of small seabird in the gadfly petrel genus, Endemism, endemic to the island of Madeira. This long-winged petrel has a grey back and wings, with a dark "W" marking across the wings ...

in 1997, a trumpeter finch

The trumpeter finch (''Bucanetes githagineus'') is a small passerine bird in the finch Family (biology), family Fringillidae. It is mainly a desert species which is found in North Africa and Spain through to southern Asia. It has occurred as a V ...

in 2008, and an alder flycatcher

The alder flycatcher (''Empidonax alnorum'') is a small insect-eating bird of the tyrant flycatcher family. The genus name ''Empidonax'' is from Ancient Greek ''empis'', "gnat", and ''anax'', "master". The specific ''alnorum'' is Latin and means ...

in 2010. Ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

and pioneering bird photographer Emma Turner started ringing

Ringing may mean:

Vibrations

* Ringing (signal), unwanted oscillation of a signal, leading to ringing artifacts

* Vibration of a harmonic oscillator

** Bell ringing

* Ringing (telephony), the sound of a telephone bell

* Ringing (medicine), a ri ...

common terns on the Point in 1909, and the use of this technique for migration studies has continued since. A notable recovery was a Sandwich tern killed for food in Angola, and a Radde's warbler

Radde's warbler (''Phylloscopus schwarzi'') is a leaf warbler which breeds in Siberia. This warbler is strongly migratory and winters in Southeast Asia. The genus name ''Phylloscopus'' is from Ancient Greek ''phullon'', "leaf", and ''skopos'', ...

trapped for ringing in 1961 was only the second British record of this species at that time. In the winter, the marshes hold golden plover

'' Pluvialis '' is a genus of plovers, a group of wading birds comprising four species that breed in the temperate or Arctic Northern Hemisphere.

In breeding plumage, they all have largely black underparts, and golden or silvery upperparts. The ...

s and wildfowl

The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating o ...

including common shelduck

The common shelduck (''Tadorna tadorna'') is a waterfowl species of the shelduck genus, ''shelduck, Tadorna''. It is widespread and common in the Euro-Siberian region of the Palearctic realm, Palearctic, mainly breeding in temperate and wintering ...

, Eurasian wigeon

The Eurasian wigeon or European wigeon (''Mareca penelope''), also known as the widgeon or the wigeon, is one of three species of wigeon in the dabbling duck genus ''Mareca''. It is common and widespread within its Palearctic range.

Taxonomy

T ...

, brent geese

The brant or brent goose (''Branta bernicla'') is a small goose of the genus ''Branta''. There are three subspecies, all of which winter along temperate-zone sea-coasts and breed on the high-Arctic tundra.

The Brent oilfield was named after ...

and common teal

The Eurasian teal (''Anas crecca''), common teal, or Eurasian green-winged teal is a common and widespread duck that breeds in temperate Eurosiberia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian teal is often called simply the teal due to being th ...

, while common scoter

The common scoter (''Melanitta nigra'') is a large sea duck, in length, which breeds over the far north of Europe and the Palearctic east to the Olenyok River. The black scoter (''M. americana'') of North America and eastern Siberia was formerl ...

s, common eider

The common eider (pronounced ) (''Somateria mollissima''), also called St. Cuthbert's duck or Cuddy's duck, is a large ( in body length) sea-duck that is distributed over the northern coasts of Europe, North America and eastern Siberia. It breed ...

s, common goldeneye

The common goldeneye or simply goldeneye (''Bucephala clangula'') is a medium-sized sea duck of the genus ''Goldeneye (duck), Bucephala'', the goldeneyes. Its closest relative is the similar Barrow's goldeneye. The genus name is derived from th ...

s and red-breasted merganser

The red-breasted merganser (''Mergus serrator'') is a duck species that is native to much of the Northern Hemisphere. The red breast that gives the species its common name is only displayed by males in breeding plumage. Individuals fly rapidly ...

s swim offshore.

Other animals

Blakeney Point has a mixed colony of about 500

Blakeney Point has a mixed colony of about 500 harbour

A harbor (American English), or harbour (Commonwealth English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences), is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be Mooring, moored. The t ...

and grey seal

The grey seal (''Halichoerus grypus'') is a large seal of the family Phocidae, which are commonly referred to as "true seals" or "earless seals". The only species classified in the genus ''Halichoerus'', it is found on both shores of the Nort ...

s. The harbour seals have their young between June and August, and the pups, which can swim almost immediately, may be seen on the mud flats. Grey seals breed in winter, between November and January; their young cannot swim until they have lost their first white coat, so they are restricted to dry land for their first three or four weeks, and can be viewed on the beach during this period. Grey seals colonised a site in east Norfolk in 1993, and started breeding regularly at Blakeney in 2001. It is possible that they now outnumber harbour seals off the Norfolk coast. Seal-watching boat trips run from Blakeney and Morston harbours, giving good views without disturbing the seals. The corpses of 24 female or juvenile harbour seals were found in the Blakeney area between March 2009 and August 2010, each with spirally cut wounds consistent with the animal having been drawn through a ducted propeller

A ducted propeller, also known as a Kort nozzle, is a marine propeller shrouded with a non-rotating nozzle. It is used to improve the efficiency of the propeller and is especially used on heavily loaded propellers or propellers with limited d ...

.Thompson ''et al'' (2010) pp. 1–4.

The rabbit

Rabbits are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also includes the hares), which is in the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). They are familiar throughout the world as a small herbivore, a prey animal, a domesticated ...

population can grow to a level at which their grazing and burrowing adversely affects the fragile dune vegetation. When rabbit numbers are reduced by myxomatosis

Myxomatosis is a disease caused by '' Myxoma virus'', a poxvirus in the genus '' Leporipoxvirus''. The natural hosts are tapeti (''Sylvilagus brasiliensis'') in South and Central America, and brush rabbits (''Sylvilagus bachmani'') in North ...

, the plants recover, although those that are toxic to rabbits, like ragwort

''Jacobaea vulgaris'', syn. ''Senecio jacobaea'', is a very common wild flower in the family Asteraceae that is native to northern Eurasia, usually in dry, open places, and has also been widely distributed as a weed elsewhere.

Common names inc ...

, then become less common due to increased competition from the edible species.Elton (1979) pp. 167–168. The rabbits may be killed by carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they ar ...

s such as red foxes, weasels and stoats. Records of mammals that are rare in the NNR area include red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

swimming in the haven, a hedgehog

A hedgehog is a spiny mammal of the subfamily Erinaceinae, in the eulipotyphlan family Erinaceidae. There are 17 species of hedgehog in five genera found throughout parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and in New Zealand by introduction. The ...

and a beached Sowerby's beaked whale

Sowerby's beaked whale (''Mesoplodon bidens''), also known as the North Atlantic or North Sea beaked whale, is a species of toothed whale. It was the first mesoplodont whale to be described. James Sowerby, an English naturalist and artist, fir ...

. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

An insect survey in September 2009 recorded 187 beetle species, including two new to Norfolk, the rove beetle

The rove beetles are a family (biology), family (Staphylinidae) of beetles, primarily distinguished by their short elytra (wing covers) that typically leave more than half of their abdominal segments exposed. With over 66,000 species in thousand ...

'' Phytosus nigriventris'' and the fungus beetle ''Leiodes ciliaris

''Leiodes'' is a genus of round fungus beetles in the family Leiodidae. There are at least 110 described species in ''Leiodes''.

ITIS Taxonomic note:

* Published before 13 Jan 1797 per Bouchard et al. (2011).

See also

* List of Leiodes species ...

'', and two very rarely seen in the county, the sap beetle

The sap beetles, also known as Nitidulidae, are a family (biology), family of beetles.

They are small (2–6 mm) ovoid, usually dull-coloured beetles, with knobbed antenna (biology), antennae. Some have red or yellow spots or bands. They fe ...

'' Nitidula carnaria'' and the clown beetle

Histeridae is a family of beetles commonly known as clown beetles or hister beetles. There are more than 410 genera and 4,800 described species in Histeridae worldwide, with more than 500 species in North America. They can be identified by their ...

'' Gnathoncus nanus''. There were also 24 types of spider, and the five ant species included the nationally rare'' Myrmica specioides''. Retrieved 16 September 2012. The rare millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

'' Thalassisobates littoralis'', a specialist of coastal shingle habitats, was found here in 1972,Blower (1985) pp. 98–101. and a red-veined darter

The red-veined darter or nomad (''Sympetrum fonscolombii'') is a dragonfly of the genus ''Sympetrum''.

Taxonomy

There is genetic and behavioural evidence that ''S. fonscolombii'' is not closely related to the other members of the genus ''Sympetr ...

appeared in 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012. Tens of thousands of migrant turnip sawflies were recorded for a few days in late summer 2006, along with red-eyed damselflies. The silver Y

The silver Y (''Autographa gamma'') is a migratory moth of the family Noctuidae which is named for the silvery Y-shaped mark on each of its forewings.

Description

The silver Y is a medium-sized moth with a wingspan of 30 to 45 mm. The win ...

moth also appears in large numbers in some years.Foster, W A in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 79.

The many inhabitants of the tidal flats include lugworm

''Arenicola'', also known as sandworms, is a genus of capitellid annelid worms comprising the lugworms and black lugs.

''A.cristata'' is the dominant warm-water lugworm on the shores of North America and Humboldt Bay, California. ''A. caroledna' ...

s, polychaete worms

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class of generally marine annelid worms, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called chaetae, which are mad ...

, sand hoppers and other amphipod crustaceans, and gastropod molluscs. These molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

feed on the algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

growing on the surface of the mud, and include the tiny ''Hydrobia

''Hydrobia'' is a genus of very small brackish water snails with a gill and an operculum, aquatic gastropod mollusks in the family Hydrobiidae.Gofas, S. (2011). Hydrobia Hartmann, 1821. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http ...

'', an important food for waders because of its abundance at densities of more than 130,000 m−2. Bivalve molluscs

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

include the edible common cockle

The common cockle (''Cerastoderma edule'') is a species of edible saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Cardiidae, the cockles. It is found in waters off Europe, from Iceland in the north, south into waters off western Africa a ...

, although it is not harvested here.Barnes, R S K in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 67–75.

Plants

marram grass

''Ammophila'' (synonymous with ''Psamma'' P. Beauv.) is a genus of flowering plants consisting of two or three very similar species of grasses. The genus name ''Ammophila'' originates from the Greek words ἄμμος (''ámmos''), meaning "sand ...

, sand couch-grass, lyme-grass

''Leymus arenarius'' is a psammophilic (sand-loving) species of grass in the family Poaceae, native to the coasts of Atlantic and Northern Europe. ''Leymus arenarius'' is commonly known as sand ryegrass, sea lyme grass, or simply lyme grass.

and grey hair-grass help to bind the sand. Sea holly Sea holly is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Acanthus ebracteatus''

* ''Eryngium'' species, especially:

** ''Eryngium maritimum

''Eryngium maritimum'', the sea holly or sea eryngo, or sea eryngium, is a perennial species o ...

, sand sedge

''Carex arenaria'', or sand sedge, is a species of perennial sedge of the genus ''Carex'' which is commonly found growing in dunes and other sandy habitats, as the species epithet suggests (Latin , "sandy"). It grows by long stolons under the soi ...

, bird's-foot trefoil

''Lotus corniculatus'' is a flowering plant in the pea family Fabaceae. Common names include common bird's-foot trefoil, eggs and bacon, birdsfoot deervetch, and just bird's-foot trefoil (a name also often applied to other ''Lotus'' spp.). It ha ...

and pyramidal orchid

''Anacamptis pyramidalis'', the pyramidal orchid, is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the genus '' Anacamptis'' of the family Orchidaceae. The scientific name ''Anacamptis'' derives from Greek ανακάμτειν 'anakamptein' meaning ' ...

are other specialists of this arid habitat. Some specialised moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s are found on the dunes, and help to consolidate the sand;Tansley (1939) p. 855. a survey in September 2009 found 41 lichen species. The plant distribution is influenced by the dunes' age as well as their moisture content, the deposits becoming less alkaline as calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

from animal shells is leached out of the sand to be replaced by more acidic humus

In classical soil science, humus is the dark organic matter in soil that is formed by the decomposition of plant and animal matter. It is a kind of soil organic matter. It is rich in nutrients and retains moisture in the soil. Humus is the Lati ...

from plant decomposition products. Marram grass is particularly discouraged by the change in acidity. A similar pattern is seen with mosses

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta ('' sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and ho ...

and lichens, with the various areas of the dunes containing different species according to the acidity of the sand. At least four moss species have been identified as important in dune stabilization, since they help to consolidate the sand, add nutrients as they decompose, and pave the way for more exacting plant species.Lodge, E in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 60–63. The moss and lichen flora of Blakeney Point differs markedly from that of lime-rich dunes on the western coasts of the UK. Non-native tree lupins have become established near the Lifeboat House, where they now grow wild.White, D J B in Allison & Morley (1989) p. 41.Mabey (1996) p. 226.

The shingle ridge attracts biting stonecrop, sea campion

''Silene uniflora'' is a species of flowering plant in the carnation family known by the common name sea campion.

Description

''Silene uniflora'' is a perennial plant that forms a mat with stems growing outwards to as much as 30 cm. The ste ...

, yellow horned poppy, sea thrift

''Armeria maritima'', the thrift, sea thrift or sea pink, is a species of flowering plant in the family Plumbaginaceae. It is a compact evergreen perennial which grows in low clumps and sends up long stems that support globes of bright pink flow ...

, bird's foot trefoil and sea beet

The sea beet, ''Beta vulgaris'' subsp. ''maritima'' (L.) Arcangeli., is an Old World perennial plant with edible leaves, leading to the common name wild spinach.

Description

Sea beet is an erect and sprawling perennial plant up to high with da ...

. In the damper areas, where the shingle adjoins salt marsh, rock sea lavender

''Limonium binervosum'', commonly known as rock sea-lavender, is an aggregate species in the family Plumbaginaceae.

Despite the common name, rock sea-lavender is not related to the lavenders or to rosemary but is a perennial herb with small viol ...

, matted sea lavender and scrubby sea-blite also thrive, although they are scarce in Britain away from the Norfolk coast. The saltmarsh contains European glasswort and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first sea aster

''Tripolium pannonicum'', called sea aster or seashore aster and often known by the synonyms ''Aster tripolium'' or ''Aster pannonicus'', is a flowering plant, native to Eurasia and northern Africa, that is confined in its distribution to salt ma ...

, then mainly sea lavender, with sea purslane in the creeks, and smaller areas of sea plantain

''Plantago maritima'', the sea plantain, seaside plantain or goose tongue, is a species of flowering plant in the plantain family Plantaginaceae. It has a subcosmopolitan distribution in temperate and Arctic regions, native to most of Europe, n ...

and other common marsh plants. Six previously unknown diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

species were found in the waters around the point in 1952, along with six others not previously recorded in Britain.

European glasswort is picked between May and September and sold locally as "samphire".Stannard & Smith (2005) p. 34 It is a fleshy plant which when blanched or steamed has a taste which leads to its alternative name of "sea asparagus", and it is often eaten with fish.Knights & Phillips (1979) p. 49.Sweetser & Laurie (2009) p. 187. It can also be eaten raw when young. Retrieved 21 October 2012. Glasswort is also a favourite food for the rabbits, which will venture onto the saltmarsh in search of this succulent plant.

Recreation

The 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million who made overnight stays on the Norfolk coast in 1999 are estimated to have spent £122 million, and secured the equivalent of 2,325 full-time jobs in that area. A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites, including Blakeney, Cley and Morston found that 39 per cent of visitors gave

The 7.7 million day visitors and 5.5 million who made overnight stays on the Norfolk coast in 1999 are estimated to have spent £122 million, and secured the equivalent of 2,325 full-time jobs in that area. A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites, including Blakeney, Cley and Morston found that 39 per cent of visitors gave birdwatching

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device such as binoculars or a telescop ...

as the main purpose of their visit. The villages nearest to the Point, Blakeney and Cley, had the highest ''per capita'' spend per visitor of those surveyed, and Cley was one of the two sites with the highest proportion of pre-planned visits. The equivalent of 52 full-time jobs in the Cley and Blakeney area are estimated to result from the £2.45 million spent locally by the visiting public. Retrieved 29 June 2012. In addition to birdwatching and boat trips to see the seals, sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

and walking are the other significant tourist activities

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the Commerce, commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. World Tourism Organization, UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as ...

in the area.

The large number of visitors at coastal sites sometimes has negative effects. Wildlife may be disturbed, a frequent difficulty for species that breed in exposed areas such as ringed plovers and little terns, and also for wintering geese. During the breeding season, the main breeding areas for terns and seals are fenced off and signposted. Plants can be trampled, which is a particular problem in sensitive habitats such as sand dunes and vegetated shingle.Liley (2008) pp. 10–14. A boardwalk made from recycled plastic crosses the large sand dunes near the end of the Point, which helps to reduce erosion. It was installed in 2009 at a cost of £35,000 to replace its much less durable wooden predecessor. Dogs are not allowed from April to mid-August because of the risk to ground-nesting birds, and must be on a lead or closely controlled at other times. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

The Norfolk Coast Partnership, a grouping of conservation and environmental bodies, divide the coast and its hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning the 'land behind' a city, a port, or similar. Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associated wi ...

into three zones for tourism development purposes. Blakeney Point, along with Holme Dunes and Holkham dunes, is considered to be a sensitive habitat already suffering from visitor pressure, and therefore designated as a red-zone area with no development or parking improvements to be recommended. The rest of the reserve is placed in the orange zone, for locations with fragile habitats but less tourism pressure.Scott Wilson Ltd (2006) pp. 5–6.

Coastal changes

The spit is a relatively young feature in

The spit is a relatively young feature in geological

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth s ...

terms, and in recent centuries it has been extending westwards and landwards through tidal and storm action. This growth is thought to have been enhanced by the reclamation of the salt marshes along this coast in recent centuries, which removed a natural barrier to the movement of shingle.East Anglia Coastal Group (2010) pp. 13–14. The amount of shingle moved by a single storm can be "spectacular"; Retrieved 23 November 2011. the spit has sometimes been breached, becoming an island for a time, and this may happen again.May, V J (2003)North Norfolk Coast

in May (2003) pp. 1–19. The northernmost part of Snitterley (now Blakeney) village was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.Muir (2008) p. 103. In the last two hundred years, maps have been accurate enough for the distance from the Blakeney Chapel ruins to the sea to be measured. The in 1817 had become by 1835, in 1907, and by the end of the 20th century. The spit is moving towards the mainland at about per year;Gray (2004) pp. 363–365. and several former raised islands or "eyes" have already disappeared, first covered by the advancing shingle, and then lost to the sea. The massive 1953 flood overran the main beach, and only the highest dune tops remained above water. Sand was washed into the salt marshes, and the extreme tip of the point was breached, but as with other purely natural parts of the coast, like Scolt Head Island, little lasting damage was done.Allison H & Morley J in Allison & Morley (1989) pp. 7–8. Landward movement of the shingle meant that the channel of the Glaven was becoming blocked increasingly often by 2004. This led to flooding of Cley village and the environmentally important Blakeney freshwater marshes. The

Environment Agency

The Environment Agency (EA) is a non-departmental public body, established in 1996 and sponsored by the United Kingdom government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, with responsibilities relating to the protection and enha ...

considered several remedial options. It concluded that attempting to hold back the shingle or breaching the spit to create a new outlet for the Glaven would be expensive and probably ineffective, and doing nothing would be environmentally damaging. The Agency decided to create a new route for the river to the south of its original line, and work to realign a stretch of river further south was completed in 2007 at a cost of about £1.5 million. Retrieved 4 December 2011. The Glaven had previously been realigned from an earlier, more northerly, course in 1922. The ruins of Blakeney Chapel are now to the north of the river embankment, and essentially unprotected from coastal erosion, since the advancing shingle will no longer be swept away by the stream. The chapel will be buried by a ridge of shingle as the spit continues to move south, and then lost to the sea, Retrieved 19 September 2011. perhaps within 20–30 years.Murphy (2009) p. 9.

Notes

References

Cited texts

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Open Street Map

{{Authority control Blakeney, Norfolk Coastal features of Norfolk Landforms of Norfolk National nature reserves in England National Trust properties in Norfolk Nature reserves in Norfolk North Norfolk Spits of England Special Protection Areas in England Beaches of Norfolk Protected areas established in 1912