Blacks And Blues on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Black is a

Numerous communities of dark-skinned peoples are present in

Numerous communities of dark-skinned peoples are present in  In the 18th century, the Moroccan Sultan

In the 18th century, the Moroccan Sultan

In the

In the

In the medieval Arab world, the ethnic designation of "Black" encompassed not only

In the medieval Arab world, the ethnic designation of "Black" encompassed not only

About 150,000 East African and black people live in

About 150,000 East African and black people live in

The

The

"Australian South Sea Islanders: A Century of Race Discrimination under Australian Law"

Australian Human Rights Commission. were brought from the

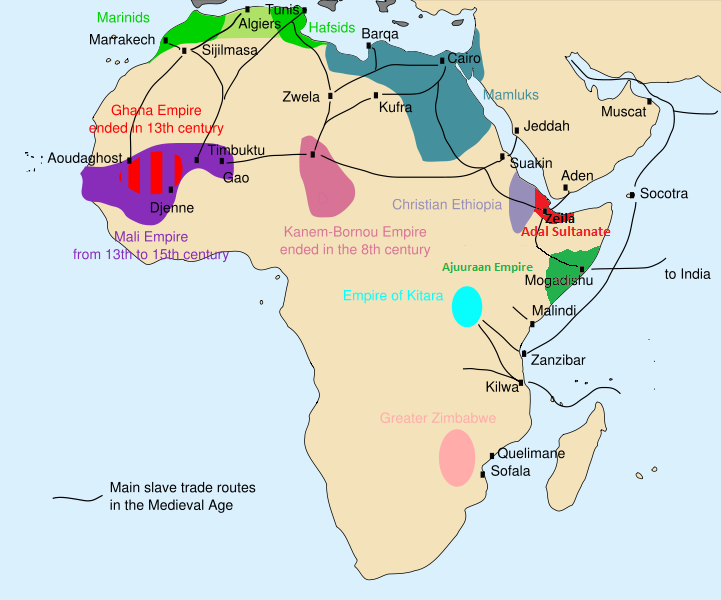

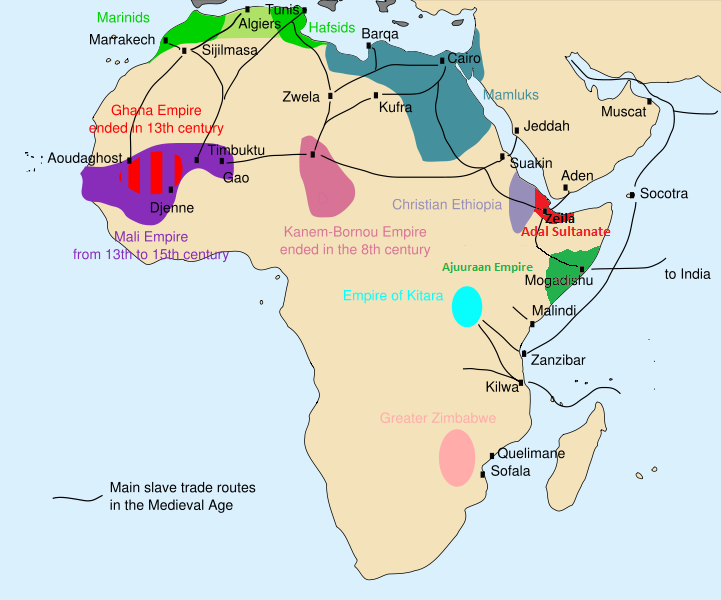

There were eight principal areas used by Europeans to buy and ship slaves to the

There were eight principal areas used by Europeans to buy and ship slaves to the

The concept of blackness in the United States has been described as the degree to which one associates themselves with mainstream African-American culture, politics, and values. To a certain extent, this concept is not so much about race but more about political orientation, culture and behavior. Blackness can be contrasted with "acting white", where black Americans are said to behave with assumed characteristics of stereotypical white Americans with regard to fashion, dialect, taste in music, and possibly, from the perspective of a significant number of black youth, academic achievement.

Due to the often political and cultural contours of blackness in the United States, the notion of blackness can also be extended to non-black people. Toni Morrison once described Bill Clinton as the first black President of the United States, because, as she put it, he displayed "almost every trope of blackness". Clinton welcomed the label.

The question of blackness also arose in the Democrat Barack Obama's 2008 United States presidential election, 2008 presidential campaign. Commentators questioned whether Obama, who was elected the first president with black ancestry, was "black enough", contending that his background is not typical because his mother was a white American and his father was a black student visitor from Kenya. Obama chose to identify as black and

The concept of blackness in the United States has been described as the degree to which one associates themselves with mainstream African-American culture, politics, and values. To a certain extent, this concept is not so much about race but more about political orientation, culture and behavior. Blackness can be contrasted with "acting white", where black Americans are said to behave with assumed characteristics of stereotypical white Americans with regard to fashion, dialect, taste in music, and possibly, from the perspective of a significant number of black youth, academic achievement.

Due to the often political and cultural contours of blackness in the United States, the notion of blackness can also be extended to non-black people. Toni Morrison once described Bill Clinton as the first black President of the United States, because, as she put it, he displayed "almost every trope of blackness". Clinton welcomed the label.

The question of blackness also arose in the Democrat Barack Obama's 2008 United States presidential election, 2008 presidential campaign. Commentators questioned whether Obama, who was elected the first president with black ancestry, was "black enough", contending that his background is not typical because his mother was a white American and his father was a black student visitor from Kenya. Obama chose to identify as black and

Approximately 12 million people were shipped from Africa to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade from 1492 to 1888. Of these, 11.5 million of those shipped to South America and the

Approximately 12 million people were shipped from Africa to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade from 1492 to 1888. Of these, 11.5 million of those shipped to South America and the

According to the 2022 census, 10.2% of Brazilians said they were black, compared with 7.6% in 2010, and 45.3% said they were racially mixed, up from 43.1%, while the proportion of self-declared white Brazilians has fallen from 47.7% to 43.5%. Activists from Brazil's Black movement attribute the racial shift in the population to a growing sense of pride among African-descended Brazilians in recognising and celebrating their ancestry.

The philosophy of the racial democracy in Brazil has drawn some criticism, based on economic issues. Brazil has one of the largest gaps in income distribution in the world. The richest 10% of the population earn 28 times the average income of the bottom 40%. The richest 10 percent is almost exclusively white or predominantly European in ancestry. One-third of the population lives under the Poverty threshold, poverty line, with blacks and other people of color accounting for 70 percent of the poor.

According to the 2022 census, 10.2% of Brazilians said they were black, compared with 7.6% in 2010, and 45.3% said they were racially mixed, up from 43.1%, while the proportion of self-declared white Brazilians has fallen from 47.7% to 43.5%. Activists from Brazil's Black movement attribute the racial shift in the population to a growing sense of pride among African-descended Brazilians in recognising and celebrating their ancestry.

The philosophy of the racial democracy in Brazil has drawn some criticism, based on economic issues. Brazil has one of the largest gaps in income distribution in the world. The richest 10% of the population earn 28 times the average income of the bottom 40%. The richest 10 percent is almost exclusively white or predominantly European in ancestry. One-third of the population lives under the Poverty threshold, poverty line, with blacks and other people of color accounting for 70 percent of the poor.

In 2015 United States, African Americans, including multiracial people, earned 76.8% as much as white people. By contrast, black and mixed race Brazilians earned on average 58% as much as whites in 2014. The gap in income between blacks and other non-whites is relatively small compared to the large gap between whites and all people of color. Other social factors, such as illiteracy and education levels, show the same patterns of disadvantage for people of color.

Some commentators observe that the United States practice of Racial segregation, segregation and white supremacy in the South, and discrimination in many areas outside that region, forced many African Americans to unite in the civil rights struggle, whereas the fluid nature of race in Brazil has divided individuals of African ancestry between those with more or less ancestry and helped sustain an image of the country as an example of post-colonial harmony. This has hindered the development of a common identity among black Brazilians.

Though Brazilians of at least partial African heritage make up a large percentageTom Phillips

In 2015 United States, African Americans, including multiracial people, earned 76.8% as much as white people. By contrast, black and mixed race Brazilians earned on average 58% as much as whites in 2014. The gap in income between blacks and other non-whites is relatively small compared to the large gap between whites and all people of color. Other social factors, such as illiteracy and education levels, show the same patterns of disadvantage for people of color.

Some commentators observe that the United States practice of Racial segregation, segregation and white supremacy in the South, and discrimination in many areas outside that region, forced many African Americans to unite in the civil rights struggle, whereas the fluid nature of race in Brazil has divided individuals of African ancestry between those with more or less ancestry and helped sustain an image of the country as an example of post-colonial harmony. This has hindered the development of a common identity among black Brazilians.

Though Brazilians of at least partial African heritage make up a large percentageTom Phillips

"Brazil census shows African-Brazilians in the majority for the first time"

''The Guardian'', 17 November 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2018. of the population, few blacks have been elected as politicians. The city of Salvador, Bahia, for instance, is 80% people of color, but voters have not elected a mayor of color. Patterns of discrimination against non-whites have led some academic and other activists to advocate for use of the Portuguese term ''negro'' to encompass all African-descended people, in order to stimulate a "black" consciousness and identity.

racial

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of va ...

classification of people, usually a political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and skin color

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is largely the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents), and in ...

-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion

Complexion in humans is the natural color, texture, and appearance of the skin, especially on the face.

History

The word "complexion" is derived from the Late Latin ''complexi'', which initially referred in general terms to a combination of t ...

. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin

Dark skin is a type of human skin color that is rich in melanin pigments. People with dark skin are often referred to as black people, although this usage can be ambiguous in some countries where it is also used to specifically refer to differe ...

and often additional phenotypical

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or phenotypic trait, traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (biology), morphology (physical form and structure), its Developmental biology, develo ...

characteristics are relevant, such as facial and hair-texture features; in certain countries, often in socially based systems of racial classification

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of va ...

in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, the term "black" is used to describe persons who are perceived as dark-skinned compared to other populations. It is most commonly used for people of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

n ancestry, Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

and Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and Indigenous peoples of Oceania, indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in an area stretching from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands. Most speak one of the many languages of the Austronesian languages, Austronesian l ...

, though it has been applied in many contexts to other groups, and is no indicator of any close ancestral relationship whatsoever. Indigenous African societies do not use the term ''black'' as a racial identity outside of influences brought by Western cultures.

Contemporary anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

s and other scientists, while recognizing the reality of biological variation between different human populations, regard the concept of a unified, distinguishable "Black race" as socially constructed

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

. Different societies apply different criteria regarding who is classified "black", and these social constructs have changed over time. In a number of countries, societal variables affect classification as much as skin color, and the social criteria for "blackness" vary. Some perceive the term 'black' as a derogatory, outdated, reductive or otherwise unrepresentative label, and as a result neither use nor define it, especially in African countries with little to no history of colonial racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

.

In the anglosphere

The Anglosphere, also known as the Anglo-American world, is a Western-led sphere of influence among the Anglophone countries. The core group of this sphere of influence comprises five developed countries that maintain close social, cultura ...

the term can carry a variety of meanings depending on the country. In the United Kingdom, "black" was historically equivalent with "person of color

The term "person of color" (: people of color or persons of color; abbreviated POC) is used to describe any person who is not considered "white". In its current meaning, the term originated in, and is associated with, the United States. From th ...

", a general term for non-European peoples. While the term "person of color" is commonly used and accepted in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the near-sounding term " colored person" is considered highly offensive, except in South Africa, where it is a descriptor for a person of mixed race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

. In other regions such as Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

, settlers applied the adjective "black" to the indigenous population. It was universally regarded as highly offensive in Australia until the 1960s and 70s. "Black" was generally not used as a noun, but rather as an adjective qualifying some other descriptor (e.g. "black ****"). As desegregation progressed after the 1967 referendum, some Aboriginals adopted the term, following the American fashion, but it remains problematic.

Several American style guides, including the ''AP Stylebook

''The Associated Press Stylebook'' (generally called the ''AP Stylebook''), alternatively titled ''The Associated Press Stylebook and Briefing on Media Law'', is a style and usage guide for American English grammar created by American journali ...

'', changed their guides to capitalize the 'b' in 'black', following the 2020 murder of George Floyd

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black American man, was murdered in Minneapolis by Derek Chauvin, a 44-year-old White police officer. Floyd had been arrested after a store clerk reported that he made a purchase using a c ...

, an African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

. The '' ASA Style Guide'' says that the 'b' should not be capitalized.

Africa

Northern Africa

Numerous communities of dark-skinned peoples are present in

Numerous communities of dark-skinned peoples are present in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, some dating from prehistoric communities. Others descend from migrants via the historical trans-Saharan trade or, after the Arab invasions of North Africa in the 7th century, from slaves from the trans-Saharan slave trade

The trans-Saharan slave trade, also known as the Arab slave trade, was a Slavery, slave trade in which slaves Trans-Saharan trade, were mainly transported across the Sahara. Most were moved from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa to be sold to ...

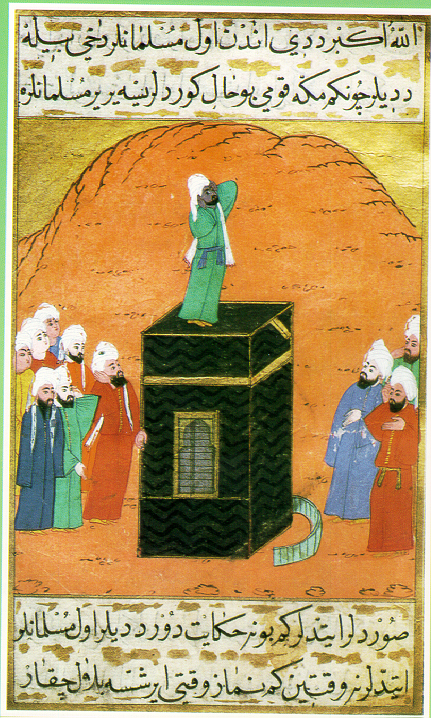

in North Africa. In the 18th century, the Moroccan Sultan

In the 18th century, the Moroccan Sultan Moulay Ismail

Moulay Ismail Ibn Sharif (, – 22 March 1727) was a Sultan of Morocco from 1672 to 1727, as the second ruler of the 'Alawi dynasty. He was the seventh son of Moulay Sharif and was governor of the province of Fez and the north of Morocco from ...

"the Warrior King" (1672–1727) raised a corps of 150,000 black soldiers, called his Black Guard.

According to Carlos Moore, resident scholar at Brazil's University of the State of Bahia, in the 21st century Afro-multiracials in the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, including Arabs in North Africa, self-identify in ways that resemble multi-racials in Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

. He claims that darker-toned Arabs, much like darker-toned Latin Americans

Latin Americans (; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America).

Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-ethnic and multi-racial. Latin Americans are ...

, consider themselves white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

because they have some distant white ancestry.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar es-Sadat (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until Assassination of Anwar Sadat, his assassination by fundame ...

had a mother who was a dark-skinned Nubian Sudanese ( Sudanese Arab) woman and a father who was a lighter-skinned Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

. In response to an advertisement for an acting position, as a young man he said, "I am not white but I am not exactly black either. My blackness is tending to reddish".

Due to the patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

nature of Arab society, Arab men, including during the slave trade in North Africa, enslaved more African women than men. The female slaves were often put to work in domestic service and agriculture. The men interpreted the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

to permit sexual relations between a male master and his enslaved females outside of marriage (see Ma malakat aymanukum and sex), leading to many mixed-race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

children. When an enslaved woman became pregnant with her Arab master's child, she was considered as ''umm walad

In the Muslim world, the title of ''umm al-walad'' () was given to a Concubinage in Islam, slave-concubine who had given birth to a child acknowledged by her master as his. These women were regarded as property and could be sold by their owners, ...

'' or "mother of a child", a status that granted her privileged rights. The child was given rights of inheritance to the father's property, so mixed-race children could share in any wealth of the father. Because the society was patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

, the children inherited their fathers' social status at birth and were born free.

Some mixed-race children succeeded their respective fathers as rulers, such as Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur

Ahmad al-Mansur (; 1549 – 25 August 1603), also known by the nickname al-Dhahabī () was the Saadi Sultanate, Saadi Sultan of Morocco from 1578 to his death in 1603, the sixth and most famous of all rulers of the Saadis. Ahmad al-Mansur was an ...

, who ruled Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

from 1578 to 1608. He was not technically considered as a mixed-race child of a slave; his mother was Fulani

The Fula, Fulani, or Fulɓe people are an ethnic group in Sahara, Sahel and West Africa, widely dispersed across the region. Inhabiting many countries, they live mainly in West Africa and northern parts of Central Africa, South Sudan, Darfur, ...

and a concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

of his father.

In early 1991, non-Arabs of the Zaghawa people

The Zaghawa people, also called Beri or Zakhawa, are an ethnic group primarily residing in southwestern Libya, northeastern Chad, and western Sudan, including Darfur.

Zaghawas speak the Zaghawa language, which is an eastern Saharan language. ...

of Sudan attested that they were victims of an intensifying Arab apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

campaign, segregating Arabs and non-Arabs (specifically, people of Nilotic

The Nilotic peoples are peoples Indigenous people of Africa, indigenous to South Sudan and the Nile Valley who speak Nilotic languages. They inhabit South Sudan and the Gambela Region of Ethiopia, while also being a large minority in Kenya, Uga ...

ancestry). Sudanese Arabs, who controlled the government, were widely referred to as practicing apartheid against Sudan's non-Arab citizens. The government was accused of "deftly manipulating Arab solidarity" to carry out policies of apartheid and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

.Vukoni Lupa Lasaga, "The slow, violent death of apartheid in Sudan," 19 September 2006, Norwegian Council for Africa.

Sudanese Arabs

Sudanese Arabs () are the inhabitants of Sudan who identify as Arabs and speak Sudanese Arabic, Arabic as their mother tongue.

Sudanese Arabs make up 70% of the population of Sudan, however prior to the independence of South Sudan in 2011, Suda ...

are also black people in that they are culturally and linguistically Arabized

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic language, culture, literature, art, music, and ...

indigenous peoples of Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

of mostly Nilo-Saharan

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of around 210 African languages spoken by somewhere around 70 million speakers, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers, including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributari ...

, Nubian,Richard A. Lobban Jr. (2004): "Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia". The Scarecrow Press, p. 37. and Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2 ...

Jakobsson, Mattias; Hassan, Hisham Y.; Babiker, Hiba; Günther, Torsten; Schlebusch, Carina M.; Hollfelder, Nina (24 August 2017). "Northeast African genomic variation shaped by the continuity of indigenous groups and Eurasian migrations". ''PLOS Genetics''. 13(8): e1006976. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006976. ISSN

An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) is an eight-digit to uniquely identify a periodical publication (periodical), such as a magazine. The ISSN is especially helpful in distinguishing between serials with the same title. ISSNs a ...

1553-7404. PMC 5587336. PMID

PubMed is an openly accessible, free database which includes primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of ...

28837655. ancestry; their skin tone and appearance resembles that of other black people.

American University

The American University (AU or American) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Its main campus spans 90-acres (36 ha) on Ward Circle, in the Spri ...

economist George Ayittey

George B. N. Ayittey (13 October 1945 – 28 January 2022) was a Ghanaian economist and author. He was president of the Free Africa Foundation in Washington, D.C., a professor at American University, and an associate scholar at the Foreign P ...

accused the Arab government of Sudan of practicing acts of racism against black citizens. According to Ayittey, "In Sudan... the Arabs monopolized power and excluded blacks – Arab apartheid." Many African commentators joined Ayittey in accusing Sudan of practicing Arab apartheid.

Sahara

In the

In the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

, the native Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

populations kept "negro

In the English language, the term ''negro'' (or sometimes ''negress'' for a female) is a term historically used to refer to people of Black people, Black African heritage. The term ''negro'' means the color black in Spanish and Portuguese (from ...

" slaves. Most of these captives were of Nilo-Saharan

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of around 210 African languages spoken by somewhere around 70 million speakers, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers, including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributari ...

extraction, and were either purchased by the Tuareg nobles from slave markets in the Western Sudan or taken during raids. Their origin is denoted via the Ahaggar Berber word '' Ibenheren'' (sing. ''Ébenher''), which alludes to slaves that only spoke a Nilo-Saharan

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of around 210 African languages spoken by somewhere around 70 million speakers, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers, including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributari ...

language. These slaves were also sometimes known by the borrowed Songhay term ''Bella''.

Similarly, the Sahrawi indigenous peoples of the Western Sahara

Western Sahara is a territorial dispute, disputed territory in Maghreb, North-western Africa. It has a surface area of . Approximately 30% of the territory () is controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR); the remaining 70% is ...

observed a class system consisting of high caste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

s and low castes. Outside of these traditional tribal boundaries were "Negro" slaves, who were drawn from the surrounding areas.

North-Eastern Africa

InEthiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

, the slave classes mainly consisted of captured peoples from the Sudanese-Ethiopian and Kenyan-Somali international borders or other surrounding areas of Nilotic

The Nilotic peoples are peoples Indigenous people of Africa, indigenous to South Sudan and the Nile Valley who speak Nilotic languages. They inhabit South Sudan and the Gambela Region of Ethiopia, while also being a large minority in Kenya, Uga ...

and Bantu peoples who were collectively known as '' Shanqella'' and ''Adone'' (both analogues to "negro" in an English-speaking context). Some of these slaves were captured during territorial conflicts in the Horn of Africa and then sold off to slave merchants. The earliest representation of this tradition dates from a seventh or eighth century BC inscription belonging to the Kingdom of Damat.

These captives and others of analogous morphology were distinguished as ''tsalim barya'' (dark-skinned slave) in contrast with the Afroasiatic-speaking nobles or ''saba qayh'' ("red men") or light-skinned slave; while on the other hand, western racial category standards do not differentiate between ''saba qayh'' ("red men"—light-skinned) or ''saba tiqur'' ("black men"—dark-skinned) Horn Africans (of either Afroasiatic-speaking, Nilotic-speaking or Bantu origin) thus considering all of them as "black people" (and in some case "negro") according to Western society's notion of race.

Southern Africa

InSouth Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, the period of colonisation resulted in many unions and marriages between European and Africans (Bantu peoples of South Africa

Bantu speaking people are the majority ethno-racial group in South Africa. They are descendants of Southern Bantu-speaking peoples who settled in South Africa during the Bantu expansion. They are referred to in various census as ''blacks'', or ...

and Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

s) from various tribes, resulting in mixed-race children. As the European colonialists acquired control of territory, they generally pushed the mixed-race and African populations into second-class status. During the first half of the 20th century, the white-dominated government classified the population according to four main racial groups: ''Black'', ''White'', '' Asian'' (mostly Indian), and ''Coloured

Coloureds () are multiracial people in South Africa, Namibia and, to a smaller extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia. Their ancestry descends from the interracial mixing that occurred between Europeans, Africans and Asians. Interracial mixing in South ...

''. The Coloured group included people of mixed Bantu, Khoisan, and European ancestry (with some Malay ancestry, especially in the Western Cape

The Western Cape ( ; , ) is a provinces of South Africa, province of South Africa, situated on the south-western coast of the country. It is the List of South African provinces by area, fourth largest of the nine provinces with an area of , an ...

). The Coloured definition occupied an intermediary political position between the Black and White definitions in South Africa. It imposed a system of legal racial segregation, a complex of laws known as apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

.

The apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

bureaucracy devised complex (and often arbitrary) criteria in the Population Registration Act

The Population Registration Act of 1950 required that each inhabitant of South Africa be classified and registered in accordance with their racial characteristics as part of the system of apartheid.

Social rights, political rights, educational ...

of 1945 to determine who belonged in which group. Minor officials administered tests to enforce the classifications. When it was unclear from a person's physical appearance whether the individual should be considered Coloured or Black, the " pencil test" was used. A pencil was inserted into a person's hair to determine if the hair was kinky enough to hold the pencil, rather than having it pass through, as it would with smoother hair. If so, the person was classified as Black. Such classifications sometimes divided families.

Sandra Laing is a South African woman who was classified as Coloured by authorities during the apartheid era, due to her skin colour

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is largely the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents), and in ...

and hair texture

Hair is a protein filament that grows from hair follicle, follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick ter ...

, although her parents could prove at least three generations of European ancestors. At age 10, she was expelled from her all-white school. The officials' decisions based on her anomalous appearance disrupted her family and adult life. She was the subject of the 2008 biographical dramatic film ''Skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

'', which won numerous awards. During the apartheid era, those classed as "Coloured" were oppressed and discriminated against. But, they had limited rights and overall had slightly better socioeconomic conditions than those classed as "Black". The government required that Blacks and Coloureds live in areas separate from Whites, creating large townships located away from the cities as areas for Blacks.

In the post-apartheid era, the Constitution of South Africa has declared the country to be a "Non-racial democracy". In an effort to redress past injustices, the ANC government has introduced laws in support of affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

policies for Blacks; under these they define "Black" people to include "Africans", "Coloureds" and "Asians". Some affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

policies favor "Africans" over "Coloureds" in terms of qualifying for certain benefits. Some South Africans categorized as "African Black" say that "Coloureds" did not suffer as much as they did during apartheid. "Coloured" South Africans are known to discuss their dilemma by saying, "we were not white enough under apartheid, and we are not black enough under the ANC (African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

)".

In 2008, the High Court in South Africa ruled that Chinese South Africans

Chinese South Africans () are Overseas Chinese who reside in South Africa, including those whose ancestors came to South Africa in the early 20th century until Chinese immigration was banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904. Chinese indu ...

who were residents during the apartheid era (and their descendants) are to be reclassified as "Black people", solely for the purposes of accessing affirmative action benefits, because they were also "disadvantaged" by racial discrimination. Chinese people who arrived in the country after the end of apartheid do not qualify for such benefits.

Other than by appearance, "Coloureds" can usually be distinguished from "Blacks" by language. Most speak Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

or English as a first language

A first language (L1), native language, native tongue, or mother tongue is the first language a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period hypothesis, critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' ...

, as opposed to Bantu languages

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu language, Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀), or Ntu languages are a language family of about 600 languages of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern, East Africa, Eastern and Southeast Africa, South ...

such as Zulu or Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

. They also tend to have more European-sounding names than Bantu names.

Asia

Afro-Asians

"Afro-Asians

Afro-Asians, African Asians, Blasians, or simply Black Asians are people of mixed Asian and African ancestry. Historically, Afro-Asian populations have been marginalised as a result of human migration and social conflict.

Africa

Democratic ...

" or "African-Asians" are persons of mixed sub-Saharan African and Asian ancestry. In the United States, they are also called "black Asians" or "Blasians". Historically, Afro-Asian populations have been marginalized as a result of human migration and social conflict.Western Asia

Arab world

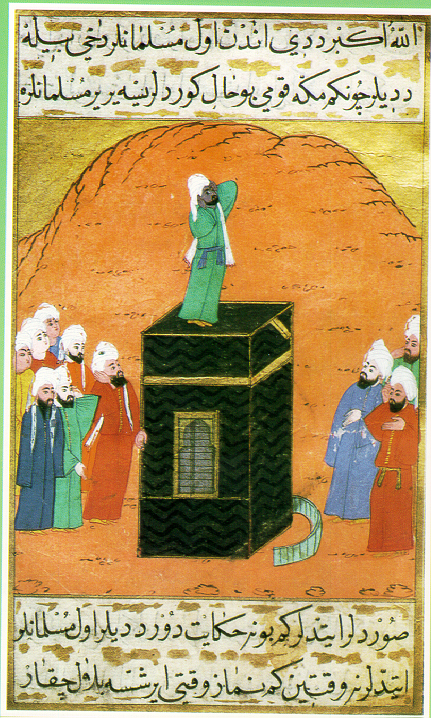

In the medieval Arab world, the ethnic designation of "Black" encompassed not only

In the medieval Arab world, the ethnic designation of "Black" encompassed not only Zanj

Zanj (, adj. , ''Zanjī''; from ) is a term used by medieval Muslim geographers to refer to both a certain portion of Southeast Africa (primarily the Swahili Coast) and to its Bantu inhabitants. It has also been used to refer to Africans col ...

, or Africans, but also communities like Zutt, Sindis and Indians from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

. Historians estimate that between the advent of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in 650 CE and the abolition of slavery in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

in the mid-20th century, 10 to 18 million black Africans (known as the Zanj) were enslaved by east African slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade, involved the capture and transportation of predominately slavery in Africa, sub-Saharan African slaves along the coasts, such as the Swahili Coast and the Horn of Afri ...

rs and transported to the Arabian Peninsula and neighboring countries. This number far exceeded the number of slaves who were taken to the Americas. Slavery in Saudi Arabia

Legal chattel slavery existed in Saudi Arabia from antiquity until its abolition in the 1960s.

Hejaz (the western region of modern day Saudi Arabia), which encompasses approximately 12% of the total land area of Saudi Arabia, was under th ...

and slavery in Yemen was abolished in 1962, slavery in Dubai in 1963, and slavery in Oman

Legal chattel slavery existed in the area which was later to become Oman from antiquity until the 1970s. Oman was united with Zanzibar from the 1690s until 1856, and was a significant center of the Indian Ocean slave trade from Zanzibar in ...

in 1970.

Several factors affected the visibility of descendants of this diaspora in 21st-century Arab societies: The traders shipped more female slaves than males, as there was a demand for them to serve as concubines

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar, but mutually exclusive.

During the e ...

in harems in the Arabian Peninsula and neighboring countries. Male slaves were castrated in order to serve as harem

A harem is a domestic space that is reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic Domestic worker, servants, and other un ...

guards. The death toll of black African slaves from forced labor was high. The mixed-race children of female slaves and Arab owners were assimilated into the Arab owners' families under the patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

kinship system

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says tha ...

. As a result, few distinctive Afro-Arab communities have survived in the Arabian Peninsula and neighboring countries.

Distinctive and self-identified black communities have been reported in countries such as Iraq, with a reported 1.2 million black people ( Afro-Iraqis), and they attest to a history of discrimination. These descendants of the Zanj have sought minority status from the government, which would reserve some seats in Parliament for representatives of their population. According to Alamin M. Mazrui et al., generally in the Arabian Peninsula and neighboring countries, most of these communities identify as both black and Arab.

Iran

Afro-Iranians are people of black African ancestry residing in Iran. During theQajar dynasty

The Qajar family (; 1789–1925) was an Iranian royal family founded by Mohammad Khan (), a member of the Qoyunlu clan of the Turkoman-descended Qajar tribe. The dynasty's effective rule in Iran ended in 1925 when Iran's '' Majlis'', conven ...

, many wealthy households imported black African women and children as slaves to perform domestic work. This slave labor was drawn exclusively from the Zanj, who were Bantu-speaking peoples that lived along the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

, in an area roughly comprising modern-day Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

and Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

.F.R.C. Bagley et al., ''The Last Great Muslim Empires'', (Brill: 1997), p.174.Bethwell A. Ogot, ''Zamani: A Survey of East African History'', (East African Publishing House: 1974), p.104.

Israel

About 150,000 East African and black people live in

About 150,000 East African and black people live in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, amounting to just over 2% of the nation's population. The vast majority of these, some 120,000, are Beta Israel

Beta Israel, or Ethiopian Jews, is a Jewish group originating from the territory of the Amhara Region, Amhara and Tigray Region, Tigray regions in northern Ethiopia, where they are spread out across more than 500 small villages over a wide ter ...

, most of whom are recent immigrants who came during the 1980s and 1990s from Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

. In addition, Israel is home to more than 5,000 members of the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem movement that are ancestry of African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

who emigrated to Israel in the 20th century, and who reside mainly in a distinct neighborhood in the Negev

The Negev ( ; ) or Naqab (), is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southern end is the Gulf of Aqaba and the resort town, resort city ...

town of Dimona

Dimona (, ) is an Israeli city in the Negev desert, to the south-east of Beersheba and west of the Dead Sea above the Arabah, Arava valley in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel. In , its population was . The Shimon Pere ...

. Unknown numbers of black converts to Judaism reside in Israel, most of them converts from the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States.

Additionally, there are around 60,000 non-Jewish African immigrants in Israel, some of whom have sought asylum. Most of the migrants are from communities in Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

and Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, particularly the Niger-Congo-speaking Nuba

The Nuba people are indigenous inhabitants of southern Sudan. The Nuba are made up of 50 various indigenous ethnic groups who inhabit the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, South Kordofan state in Sudan, encompassing multiple distinct people that ...

groups of the southern Nuba Mountains; some are illegal immigrants.

Turkey

Beginning several centuries ago, during the period of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, tens of thousands of Zanj

Zanj (, adj. , ''Zanjī''; from ) is a term used by medieval Muslim geographers to refer to both a certain portion of Southeast Africa (primarily the Swahili Coast) and to its Bantu inhabitants. It has also been used to refer to Africans col ...

captives were brought by slave traders to plantations and agricultural areas situated between Antalya

Antalya is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey and the capital of Antalya Province. Recognized as the "capital of tourism" in Turkey and a pivotal part of the Turkish Riviera, Antalya sits on Anatolia's southwest coast, flanked by the Tau ...

and Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, which gave rise to the Afro-Turk population in present-day Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. Some of their ancestry remained ''in situ'', and many migrated to larger cities and towns. Other black slaves were transported to Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, from where they or their descendants later reached the İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

area through the population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

in 1923, or indirectly from Ayvalık

Ayvalık (), formerly also known as Kydonies (), is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Balıkesir Province, Turkey. Its area is 305 km2, and its population is 75,126 (2024). It is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean Se ...

in pursuit of work.

Apart from the historical Afro-Turk presence Turkey also hosts a sizeable immigrant black population since the end of the 1990s. The community is composed mostly of modern immigrants from Ghana, Ethiopia, DRC, Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya, Eritrea, Somalia and Senegal. According to official figures 1.5 million Africans live in Turkey and around 25% of them are located in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. Other studies state the majority of Africans in Turkey lives in Istanbul and report Tarlabaşı, Dolapdere, Kumkapı, Yenikapı and Kurtuluş

Kurtuluş is a neighbourhood of the Şişli district of Istanbul that was originally called ''Tatavla,'' meaning 'stables' in Greek (). The modern Turkish name means "liberation", "salvation", "independence" or "deliverance". On 13 April 1929, si ...

as having a strong African presence.

Most of the African immigrants in Turkey come to Turkey to further migrate to Europe. Immigrants from Eastern Africa are usually refugees, meanwhile Western and Central African immigration is reported to be economically driven. It is reported that African immigrants in Turkey regularly face economic and social challenges, notably racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

and opposition to immigration

Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, is a political position that seeks to restrict immigration. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory in ...

by locals.

Southern Asia

The

The Siddi

The Siddi (), also known as the Sheedi, Sidi, or Siddhi, are an ethno-religious group living mostly in Pakistan. Some Siddis also live in India. They are primarily descended from the Bantu peoples of the Zanj coast in Southeast Africa, most ...

are an ethnic group inhabiting India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

. Members are descended from the Bantu peoples

The Bantu peoples are an Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct native Demographics of Africa, African List of ethnic groups of Africa, ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages. The language ...

of Southeast Africa

Southeast Africa, or Southeastern Africa, is an African region that is intermediate between East Africa and Southern Africa. It comprises the countries Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanza ...

. Some were merchants, sailors, indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

, slaves or mercenaries. The Siddi population is currently estimated at 270,000–350,000 individuals, living mostly in Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

, Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

, and Hyderabad

Hyderabad is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India. With an average altitude of , much ...

in India and Makran

Makran (), also mentioned in some sources as ''Mecran'' and ''Mokrān'', is the southern coastal region of Balochistan. It is a semi-desert coastal strip in the Balochistan province in Pakistan and in Iran, along the coast of the Gulf of Oman. I ...

and Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

in Pakistan. In the Makran

Makran (), also mentioned in some sources as ''Mecran'' and ''Mokrān'', is the southern coastal region of Balochistan. It is a semi-desert coastal strip in the Balochistan province in Pakistan and in Iran, along the coast of the Gulf of Oman. I ...

strip of the Sindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

and Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; , ), also spelled as Baluchistan or Baluchestan, is a historical region in West and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. This arid region o ...

provinces in southwestern Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

, these Bantu descendants are known as the Makrani. There was a brief "Black Power" movement in Sindh in the 1960s and many Siddi are proud of and celebrate their African ancestry.

Southeastern Asia

Negrito

The term ''Negrito'' (; ) refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, th ...

s, are a collection of various, often unrelated peoples, who were once considered a single distinct population of closely related groups, but genetic studies showed that they descended from the same ancient East Eurasian meta-population which gave rise to modern East Asian peoples

East Asian people (also East Asians) are the people from East Asia, which consists of China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. The total population of all countries within this region is estimated to be 1.677 billion and 21% ...

, and consist of several separate groups, as well as displaying genetic heterogeneity. They inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, and are now confined primarily to Southern Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, and the Andaman Islands of India.

Negrito means "little black people" in Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

(negrito is the Spanish diminutive of negro, i.e., "little black person"); it is what the Spaniards called the aborigines that they encountered in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. The term ''Negrito'' itself has come under criticism in countries like Malaysia, where it is now interchangeable with the more acceptable Semang

The Semang are an ethnic-minority group of the Malay Peninsula. They live in mountainous and isolated forest regions of Perak, Pahang, Kelantan and Kedah of Malaysia and the southern provinces of Thailand. The Semang are among the different eth ...

, although this term actually refers to a specific group.

They have dark skin, often curly-hair and Asiatic facial characteristics, and are stockily built.

Negritos in the Philippines frequently face discrimination. Because of their traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they are marginalized and live in poverty, unable to find employment.

Europe

Western Europe

France

While census collection of ethnic background is illegal inFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, it is estimated that there are about 2.5 – 5 million black people residing there.

Germany

As of 2020, there are approximately one million black people living in Germany.Netherlands

Afro-Dutch are residents of theNetherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

who are of Black African or Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean or African Caribbean people are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern Afro-Caribbean people descend from the Indigenous peoples of Africa, Africans (primarily fr ...

ancestry. They tend to be from the former and present Dutch overseas territories of Aruba

Aruba, officially the Country of Aruba, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the southern Caribbean Sea north of the Venezuelan peninsula of Paraguaná Peninsula, Paraguaná and northwest of Curaçao. In 19 ...

, Bonaire

Bonaire is a Caribbean island in the Leeward Antilles, and is a Caribbean Netherlands, special municipality (officially Public body (Netherlands), "public body") of the Netherlands. Its capital is the port of Kralendijk, on the west (Windward an ...

, Curaçao

Curaçao, officially the Country of Curaçao, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located in the southern Caribbean Sea (specifically the Dutch Caribbean region), about north of Venezuela.

Curaçao includ ...

, Sint Maarten

Sint Maarten () is a Countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean region of North America. With a population of 58,477 as of June 2023 on an area of , it encompasses ...

and Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

. The Netherlands also has sizable Cape Verde

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

an and other African communities.

Portugal

As of 2021, there were at least 232,000 people of recent Black-African immigrant background living inPortugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

. They mainly live in the regions of Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Porto

Porto (), also known in English language, English as Oporto, is the List of cities in Portugal, second largest city in Portugal, after Lisbon. It is the capital of the Porto District and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto c ...

, Coimbra

Coimbra (, also , , or ), officially the City of Coimbra (), is a city and a concelho, municipality in Portugal. The population of the municipality at the 2021 census was 140,796, in an area of .

The fourth-largest agglomerated urban area in Po ...

. As Portugal doesn't collect information dealing with ethnicity, the estimate includes only people that, as of 2021, hold the citizenship of a Sub Saharan African country or people who have acquired Portuguese citizenship

The primary law governing nationality of Portugal is the Nationality Act, which Coming into force, came into force on 3 October 1981. Portugal is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Portuguese nationals are Citizenship of the Eur ...

from 2008 to 2021, thus excluding descendants, people of more distant African ancestry or people who have settled in Portugal generations ago and are now Portuguese citizens.

Spain

The term "Moors

The term Moor is an Endonym and exonym, exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslims, Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a s ...

" has been used in Europe in a broader, somewhat derogatory sense to refer to Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s,Menocal, María Rosa (2002). ''Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain'', Little, Brown, & Co., p. 241. . especially those of Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

or Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

ancestry, whether living in North Africa or Iberia. Moors were not a distinct or self-defined people. Medieval and early modern Europeans applied the name to Muslim Arabs, Berbers, Sub-Saharan Africans and Europeans alike.

Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville (; 4 April 636) was a Spania, Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Seville, archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of the 19th-century historian Charles Forbes René de Montal ...

, writing in the 7th century, claimed that the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

word Maurus was derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

''mauron'', μαύρον, which is the Greek word for "black". Indeed, by the time Isidore of Seville came to write his ''Etymologies'', the word Maurus or "Moor" had become an adjective in Latin, "for the Greeks call black, mauron". "In Isidore's day, Moors were black by definition..."

Afro-Spaniards are Spanish nationals of West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

/Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

n ancestry. Today, they mainly come from Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

, Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea, officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. It has an area of . Formerly the colony of Spanish Guinea, its post-independence name refers to its location both near the Equ ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

, Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and Senegal. Additionally, many Afro-Spaniards born in Spain are from the former Spanish colony Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea, officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. It has an area of . Formerly the colony of Spanish Guinea, its post-independence name refers to its location both near the Equ ...

. Today, there are an estimated 683,000 Afro-Spaniards in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

.

United Kingdom

According to theOffice for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics (ONS; ) is the executive office of the UK Statistics Authority, a non-ministerial department which reports directly to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, UK Parliament.

Overview

The ONS is responsible fo ...

, at the 2001 census there were more than a million black people in the United Kingdom; 1% of the total population described themselves as "Black Caribbean", 0.8% as "Black African", and 0.2% as "Black other". Britain encouraged the immigration of workers from the Caribbean after World War II; the first symbolic movement was of those who came on the ship the '' Empire Windrush'' and, hence, those who migrated between 1948 and 1970 are known as the Windrush generation. The preferred official umbrella term

Hypernymy and hyponymy are the wikt:Wiktionary:Semantic relations, semantic relations between a generic term (''hypernym'') and a more specific term (''hyponym''). The hypernym is also called a ''supertype'', ''umbrella term'', or ''blanket term ...

is "black, Asian and minority ethnic" (BAME

A number of different systems of classification of ethnicity in the United Kingdom exist. These schemata have been the subject of debate, including about the nature of ethnicity, how or whether it can be categorised, and the relationship betwe ...

), but sometimes the term "black" is used on its own, to express unified opposition to racism, as in the Southall Black Sisters

Southall Black Sisters (SBS) is a non-profit organisation based in Southall, West London, England. This women's group was established in August 1979 in the aftermath of the death of anti-fascist activist Blair Peach, who had taken part in a dem ...

, which started with a mainly British Asian

British Asians (also referred to as Asian Britons) are British people of Asian people, Asian descent. They constitute a significant and growing minority of the people living in the United Kingdom, with a population of 5.76 million people or 8.6 ...

constituency, and the National Black Police Association, which has a membership of "African, African-Caribbean and Asian origin".

Eastern Europe

As African states became independent in the 1960s, theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

offered many of their citizens the chance to study in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...