Billy Graham (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Franklin Graham Jr. (; November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American evangelist, ordained

Wheaton.edu. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018. That same year,

''ABC Eyewitness News''. February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018. While serving in this position, Charles Templeton urged him to apply to

By the time of his last crusade in 2005 in New York City, he had preached 417 live crusades, including 226 in the US and 195 abroad.

By the time of his last crusade in 2005 in New York City, he had preached 417 live crusades, including 226 in the US and 195 abroad.

11 Alive, February 21, 2018, Accessed October 6, 2020 Lewis described Graham as a "saint" and someone who "taught us how to live and who taught us how to die". Graham's faith prompted his maturing view of race and segregation. He told a member of the

Graham played multiple roles that reinforced each other. Grant Wacker identified eight major roles that he played: preacher, icon, Southerner, entrepreneur, architect (bridge builder), pilgrim, pastor, and his widely recognized status as America's Protestant patriarch, which was on a par with Martin Luther King and

Graham played multiple roles that reinforced each other. Grant Wacker identified eight major roles that he played: preacher, icon, Southerner, entrepreneur, architect (bridge builder), pilgrim, pastor, and his widely recognized status as America's Protestant patriarch, which was on a par with Martin Luther King and

Q & A: Billy Graham on Aging, Regrets, and Evangelicals

christianitytoday.com, USA, January 21, 2011 Additionally, he said he would have participated in fewer conferences. He also said he had a habit of advising evangelists to save their time and avoid having too many commitments.

PBS Frontline, October 2010, program available online This was shortly before Kennedy's speech in

Graham had a personal audience with many sitting US presidents, from

Graham had a personal audience with many sitting US presidents, from  In 1970, Nixon appeared at a Graham revival in

In 1970, Nixon appeared at a Graham revival in

''The New York Times'', March 17, 2002 Captured on the tapes, Graham agreed with Nixon that Jews control the

/ref> Her obituary states that in addition to his two sons, all three of Graham's daughters would become Christian ministers as well.''Los Angeles'' "Ruth Graham, 87; had active role as wife of evangelist" June 15, 2007

/ref>

"In the News: Billy Graham on 'Most Admired' List 61 Times"

Gallup, February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018. In 1967, he was the first

''GMA Gospel Music Hall of Fame''. Retrieved March 3, 2018. Graham was the first non-musician inducted,CNN. "Remembering Billy Graham: A timeline of the evangelist's life and ministry".

''ABC Action News''. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018. and had also helped to revitalize interest in hymns and create new favorite songs."Singing to save".

''Billy Graham: American Pilgrim''. 2017. Edited by Andrew Finstuen, Grant Wacker & Anne Blue Wills. Oxford University Press. pp.75–76. Retrieved March 3, 2018. Singer Michael W. Smith was active in Billy Graham Crusades as well as

''Christianity Today''. February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018. which he co-wrote and produced with

patbooneus. September 16, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2018. who digitally combined studio recordings of various artists into what has been called a "'

''Metro Voice and wire services''. Retrieved March 3, 2018. Titled "Thank You Billy Graham", the song's video"Thank You Billy Graham".

GoldLabelArtists. August 13, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2018. was introduced by

Billy Dean. March 26, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2018. It was directed by Brian Lockwood, as a tribute album."Thank you Billy Graham : a musical tribute to one who changed our world with one message".

WorldCat. Retrieved March 5, 2018. In 2013, the album ''My Hope: Songs Inspired by the Message and Mission of Billy Graham'' was recorded by

''Christian Cinema.com''. Retrieved March 5, 2018. Other songs written to honor Graham include "Hero of the Faith" written by Eddie Carswell of

''All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music''. 2001. Edited by Vladimir Bogdanov, Chris Woodstra & Stephen Thomas Erlewine. Hal Leonard Corp. p. 610. Retrieved March 3, 2018. . "Billy, You're My Hero" by Greg Hitchcock,"The Billy Graham Song – "Billy, You're My Hero".

Greg Hitchcock Music. September 25, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2018. "Billy Graham" by The Swirling Eddies, "Billy Graham's Bible" by

''Billy Graham Movie Prepares for Oct 10 Release''

June 29, 2008. Graham did not comment on the film, but his son Franklin released a critical statement on August 18, 2008, noting that the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association "has not collaborated with nor does it endorse the movie".BGEA

"Franklin Graham Among 'Billy' Movie Critics"

''Christian Post'', August 26, 2008

''Examining Billy Graham's Theology of Evangelism''.

''Billy Graham Evangelistic Association''. Retrieved March 2, 2018. *

Academy of Achievement. Retrieved March 1, 2018. *

''Courier-Journal'' of Rochester, New York. March 24, 1971. Retrieved March 1, 2018. * Distinguished Service Award from the

The National Association of United Methodist Evangelists. Retrieved March 3, 2018. *

''Uneasy Allies?: Evangelical and Jewish Relations''. Lexington Books. Edited by Alan Mittleman, Byron Johnson and Nancy Isserman. 2007. p. 53. Retrieved March 3, 2018. . *

''The Telegraph''. December 7, 2001. Retrieved March 2, 2018. * Many honorary degrees including

''HuffPost''. October 6, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2018. * ''Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, and Our Life Beyond the Now'' (2015)Zaimov, Stoyan. "Billy Graham coming out with new book on 'Heaven, Eternity and Our Life Beyond'.

''The Christian Post''. August 31, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

''Sword of the Lord: the roots of fundamentalism in an American family''

Seattle: Chiara Press. * * * * scholarly biography, updated from 1991 edition published by William Morrow. * Middle-school version. * * * * * * *

Billy Graham Archive and Research Center

Billy Graham Center

at Wheaton College

Billy Graham Resources

Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections

Billy Graham

on ''American Experience'',

Southern Baptist

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), alternatively the Great Commission Baptists (GCB), is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptist organization, the largest Protestantism in the United States, Pr ...

minister, and civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

advocate, whose broadcasts and world tours featuring live sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

s became well known in the mid- to late 20th century. Throughout his career, spanning over six decades, Graham rose to prominence as an evangelical Christian

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

figure in the United States and abroad.

According to a biographer, Graham was considered "among the most influential Christian leaders" of the 20th century. Beginning in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Graham became known for filling stadiums and other massive venues around the world where he preached live sermons; these were often broadcast via radio and television with some continuing to be seen into the 21st century. During his six decades on television, Graham hosted his annual "crusades", evangelistic live-campaigns, from 1947 until his retirement in 2005. He also hosted the radio show ''Hour of Decision

The ''Hour of Decision'' was a live weekly radio broadcast produced by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. First broadcast in 1950 by the American Broadcasting Company, it was a half-hour program featuring sermons from noted evangelist ...

'' from 1950 to 1954. He repudiated racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

, at a time of intense racial strife in the United States, insisting on racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation), leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of Race (classification of human beings), race, and t ...

for all of his revivals and crusades, as early as 1953. He also later invited Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

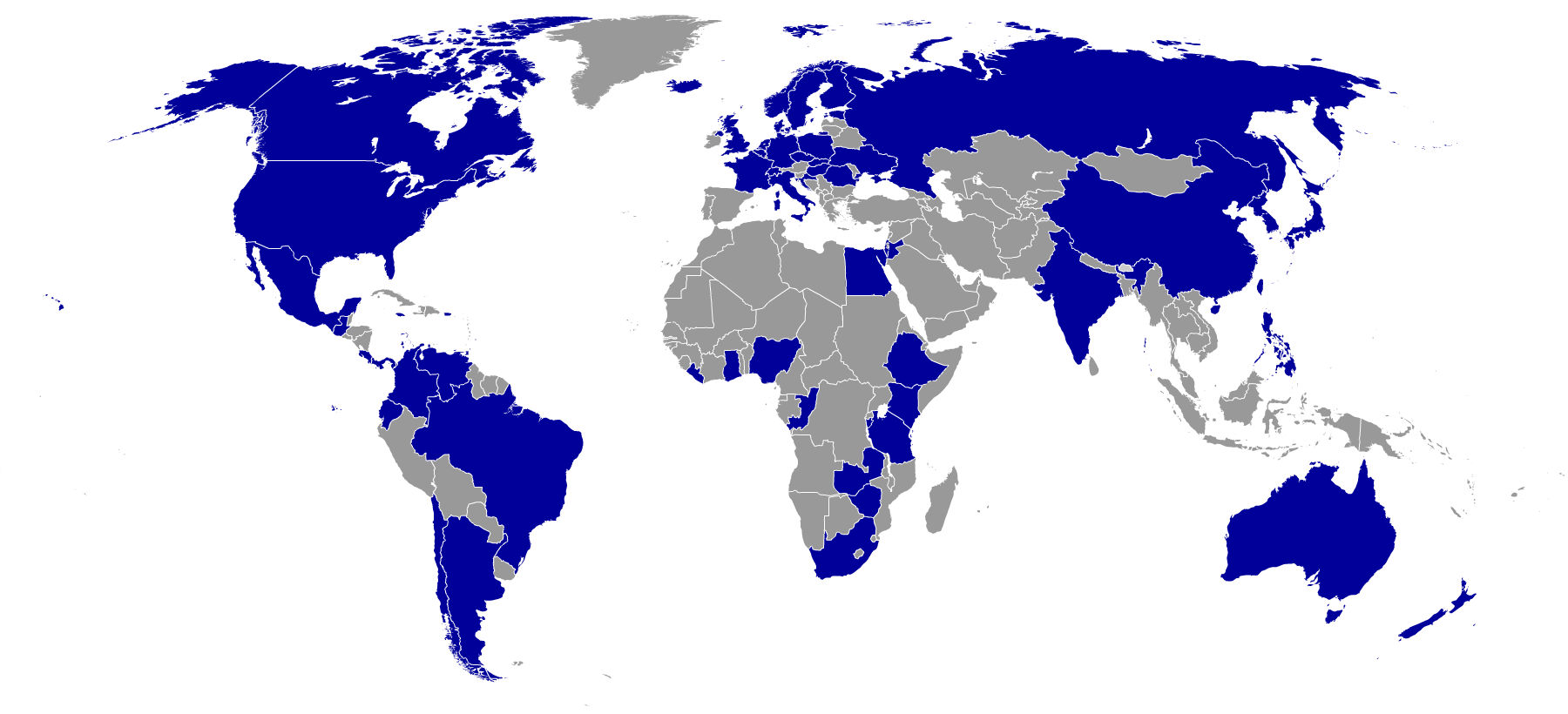

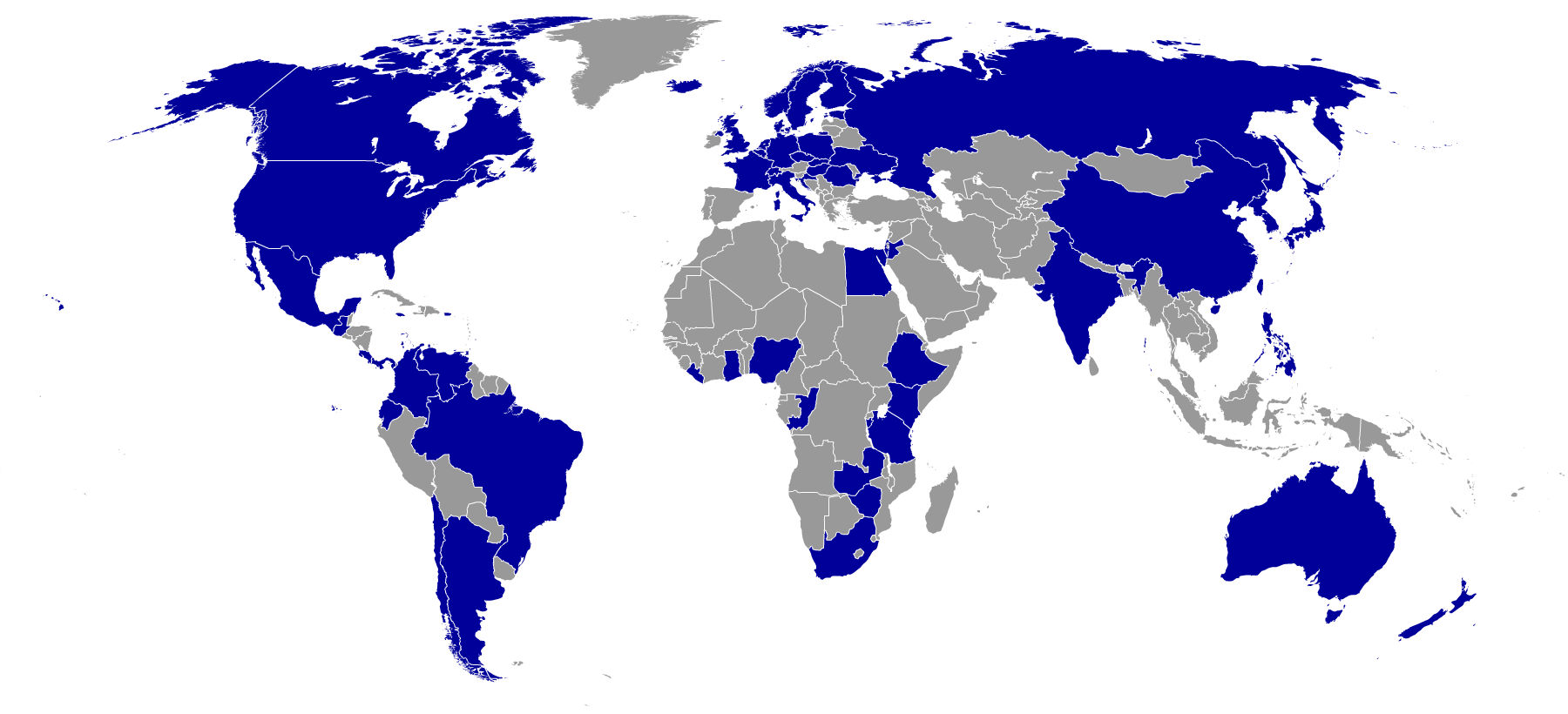

to preach jointly at a revival in New York City in 1957. In addition to his religious aims, he helped shape the worldview of a huge number of people who came from different backgrounds, leading them to find a relationship between the Bible and contemporary secular viewpoints. According to his website, Graham spoke to live audiences consisting of at least 210 million people, in more than 185 countries and territories, through various meetings, including BMS World Mission

BMS World Mission, officially Baptist Missionary Society, is a Christian missionary society founded by Baptists from England in 1792. The headquarters is in Didcot, England.

History

The BMS was formed in 1792 as the ''Particular Baptist Societ ...

and Global Mission event.

Graham was close to US presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

(one of his closest friends), and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. He was also lifelong friends with Robert Schuller

Robert Harold Schuller (September 16, 1926 – April 2, 2015) was an American Christian televangelist, pastor, motivational speaker, and author. Over five decades, Schuller pastored his church in Garden Grove, California starting in 1955. The ...

, another televangelist

Televangelism (from ''televangelist'', a blend of ''television'' and ''evangelist'') and occasionally termed radio evangelism or teleministry, denotes the utilization of media platforms, notably radio and television, for the marketing of relig ...

and the founding pastor of the Crystal Cathedral

Christ Cathedral (Latin: ''Cathedralis Christi''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Catedral de Cristo''; Vietnamese language, Vietnamese: ''Nhà Thờ Chính Tòa Chúa Kitô''), formerly the Crystal Cathedral, is an American church building in Ga ...

, whom Graham talked into starting his own television ministry. Graham's evangelism was appreciated by mainline Protestant

The mainline Protestants (sometimes also known as oldline Protestants) are a group of Protestantism in the United States, Protestant denominations in the United States and Protestantism in Canada, Canada largely of the Liberal Christianity, theolo ...

denominations, as he encouraged mainline Protestants, who were converted to his evangelical message, to remain within or return to their mainline churches. Despite early suspicions and apprehension on his part towards Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

—common among contemporaneous evangelical Protestants—Graham eventually developed amicable ties with many American Catholic Church figures, later encouraging unity between Catholics and Protestants.

Graham operated a variety of media and publishing outlets; according to his staff, more than 3.2 million people have responded to the invitation at Billy Graham Crusades to "accept Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

as their personal savior". Graham's lifetime audience, including radio and television broadcasts, likely surpassed billions of people. As a result of his crusades, Graham preached the gospel to more people, live and in-person, than anyone in the history of Christianity. Graham was on Gallup's list of most admired men and women a record-61 times. Grant Wacker wrote that, by the mid-1960s, he had become the "Great Legitimator", saying: "By then his presence conferred status on presidents, acceptability on wars, shame on racial prejudice, desirability on decency, dishonor on indecency, and prestige on civic events."

Early life

William Franklin Graham Jr. was born on November 7, 1918, in the downstairs bedroom of a farmhouse nearCharlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina and the county seat of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 United ...

. Of Scots-Irish descent, he was the eldest of four children born to Morrow (née Coffey) and dairy farmer William Franklin Graham Sr. Graham was raised on the family dairy farm with his two younger sisters Catherine Morrow and Jean and younger brother Melvin Thomas. When he was nine years old, the family moved about from their white frame house to a newly built red brick house. He was raised by his parents in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church

The Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (ARPC) is a theologically conservative denomination in North America. The ARPC was formed by the merger of the Associate Presbytery ( seceder) with the Reformed Presbytery (covenanter) in 1782. It is one ...

. Graham attended the Sharon Grammar School. He started to read books from an early age and loved to read novels for boys, especially ''Tarzan

Tarzan (John Clayton, Viscount Greystoke) is a fictional character, a feral child raised in the African jungle by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization, only to reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adventurer.

Creat ...

''. Like Tarzan, he would hang on the trees and gave the popular Tarzan yell

The Tarzan yell or Tarzan's jungle call is the distinctive, ululating yell of the character Tarzan as portrayed by actor Johnny Weissmuller in the films based on the character created by Edgar Rice Burroughs starting with '' Tarzan the Ape Man' ...

. According to his father, that yelling led him to become a minister. Graham was 15 when Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

ended in December 1933, and his father forced him and his sister Catherine to drink beer until they became sick. This created such an aversion that the two siblings avoided alcohol and drugs for the rest of their lives.

Graham was turned down for membership in a local youth group for being "too worldly". Albert McMakin, who worked on the Graham farm, persuaded him to go see evangelist Mordecai Ham. According to his autobiography, Graham was 16 when he was converted during a series of revival meetings that Ham led in Charlotte in 1934.

After graduating from Sharon High School in May 1936, Graham attended Bob Jones College. After one semester, he found that the coursework and rules were too legalistic. He was almost expelled, but Bob Jones Sr.

Robert Reynolds Jones Sr. (October 30, 1883 – January 16, 1968) was an American evangelist, pioneer religious broadcaster, and the founder and first president of Bob Jones University.

Early years

Bob Davis Reynolds Jones was the eleven ...

warned him not to throw his life away: "At best, all you could amount to would be a poor country Baptist preacher somewhere out in the sticks... You have a voice that pulls. God can use that voice of yours. He can use it mightily."

In 1937, Graham transferred to the Florida Bible Institute in Temple Terrace, Florida

Temple Terrace is a city in northeastern Hillsborough County, Florida, United States, adjacent to Tampa. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 26,690. It is the third and smallest incorporated municipality in Hillsborough County, ...

. While still a student, Graham preached his first sermon at Bostwick Baptist Church near Palatka, Florida

Palatka () is a city in and the county seat of Putnam County, Florida, Putnam County, Florida, United States. Palatka is the principal city of the Palatka Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is home to 72,893 residents. The Palatka micropolitan ...

. In his autobiography, Graham wrote of receiving his calling on the 18th green of the Temple Terrace Golf and Country Club, which was adjacent to the institute's campus. Reverend Billy Graham Memorial Park was later established on the Hillsborough River, directly east of the 18th green and across from where Graham often paddled a canoe to a small island in the river, where he would practice preaching to the birds, alligators, and cypress stumps. In 1939, Graham was ordained by a group of Southern Baptist clergy at Peniel Baptist Church in Palatka, Florida

Palatka () is a city in and the county seat of Putnam County, Florida, Putnam County, Florida, United States. Palatka is the principal city of the Palatka Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is home to 72,893 residents. The Palatka micropolitan ...

. In 1940, he graduated with a Bachelor of Theology

The Bachelor of Theology degree (BTh, ThB, or BTheol) is a two- to five-year undergraduate degree or graduate degree in theological disciplines and is typically (but not exclusively) pursued by those seeking ordination for ministry in a church, de ...

degree.

Graham then enrolled in Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois

Wheaton is a city in and the county seat of DuPage County, Illinois, United States. It is located in Milton and Winfield Townships, approximately west of Chicago. As of the 2020 census, Wheaton's population was 53,970, making it the 27th-mos ...

. During his time there, he decided to accept the Bible as the infallible

Infallibility refers to unerring judgment, being absolutely correct in all matters and having an immunity from being wrong in even the smallest matter. It can be applied within a specific domain, or it can be used as a more general adjective. Th ...

word of God. Henrietta Mears

Henrietta Cornelia Mears (October 23, 1890 – March 19, 1963) was a Christian educator, evangelist, and author who had a significant impact on evangelical Christianity in the 20th century and one of the founders of the National Sunday School Assoc ...

of the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood in California was instrumental in helping Graham wrestle with the issue. He settled it at Forest Home Christian Camp (now called Forest Home Ministries) southeast of the Big Bear Lake area in southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural List of regions of California, region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. Its densely populated coastal reg ...

. While attending Wheaton, Graham was invited to preach one Sunday in 1941 at the United Gospel Tabernacle church. After that, the congregation repeatedly asked Graham to preach at their church and later asked him to become the pastor of their church. After Graham prayed and sought advice from his friend Dr. Edman, Graham became their church's pastor.

In June 1943, Graham graduated from Wheaton College with a degree in anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

."Wheaton College Alumnus Billy Graham: 1918–2018".Wheaton.edu. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018. That same year,

Robert Van Kampen

Robert D. Van Kampen (December 16, 1938 – October 29, 1999) was an American businessman, who served as a member of various organizational boards in the business world and Christian ministry.

Van Kampen's business career took him into the invest ...

, treasurer of the National Gideon Association, invited Graham to preach at Western Springs Baptist Church, and Graham accepted the opportunity on the spot. While there, his friend Torrey Johnson, pastor of the Midwest Bible Church in Chicago, told Graham that his radio program, ''Songs in the Night'', was about to be canceled due to lack of funding. Consulting with the members of his church in Western Springs, Graham decided to take over Johnson's program with financial support from his congregation. Launching the new radio program on January 2, 1944, still called ''Songs in the Night'', Graham recruited the bass-baritone

A bass-baritone is a high-lying bass or low-lying "classical" baritone voice type which shares certain qualities with the true baritone voice. The term arose in the late 19th century to describe the particular type of voice required to sing three ...

George Beverly Shea

George Beverly Shea (February 1, 1909 – April 16, 2013) was a Canadian-born American gospel singer and hymn composer. Shea was often described as "America's beloved gospel singer"Michael Ireland, "America's 'Beloved Gospel Singer,' George Beve ...

as his director of radio ministry.

With World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

underway, Graham applied to become a chaplain in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

. After he was initially turned down for being underweight, Graham was awarded a commission as a Second Lieutenant, but came down with a severe case of mumps

MUMPS ("Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-Programming System"), or M, is an imperative, high-level programming language with an integrated transaction processing key–value database. It was originally developed at Massachusetts Gen ...

in October 1944 before he could begin chaplain training at Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the religious studies, academic study of religion or for leadership role ...

and was bedridden for six weeks. Due to his illness and the fact that the war was expected to end soon, he was discharged from the army. After a period of recuperation in Florida, he was hired as the first full-time evangelist of the new Youth for Christ

Youth For Christ (YFC) is a worldwide Christian movement working with young people, whose main purpose is evangelism among teenagers. It began informally in New York City in 1940, when Jack Wyrtzen held evangelical Protestant rallies for teenager ...

(YFC), co-founded by Torrey Johnson

Torrey Maynard Johnson (March 15, 1909 – May 15, 2002) was a Chicago Baptist who is best remembered as the founder of Youth for Christ in 1944. For a time Johnson had his own local radio program called ''Songs in the Night'', which he later tu ...

and the Canadian evangelist Charles Templeton

Charles Bradley Templeton (October 7, 1915 – June 7, 2001) was a Canadian media figure and a former Christian evangelist. Known in the 1940s and 1950s as a leading evangelist, he became an agnostic and later embraced atheism after stru ...

. In his first year as a YFC evangelist, Graham spoke in 47 US states. He traveled extensively as an evangelist in the United States and Europe in the immediate post-war era, making his first overseas trip in 1946.

In 1948, in a Modesto, California

Modesto ( ; ) is the county seat and largest city of Stanislaus County, California, United States. With a population of 218,069 according to 2022 United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau estimates, it is the List of cities and towns in Ca ...

hotel room, Graham and his evangelistic team established the Modesto Manifesto: a code of ethics for life and work to protect against accusations of financial, sexual, and power abuse. The code includes rules for collecting offerings in churches, working only with churches supportive of cooperative evangelism, using official crowd estimates at outdoor events, and a commitment to never be alone with a woman other than his wife (which become known as the "Billy Graham rule").

Graham was 29 when he became president of Northwestern Bible College in Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

in 1948. He was the youngest president of a college or university in the country, and held the position for four years before he resigned in 1952.AP and Hauser, Tom. "Evangelist Billy Graham, a former Minnesota College president, dies at 99".''ABC Eyewitness News''. February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018. While serving in this position, Charles Templeton urged him to apply to

Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a Private university, private seminary, school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Establish ...

for an advanced theological degree after he himself had done so, but Graham declined and continued in his position as president of Northwestern Bible College.''Farewell to God: My Reasons for Rejecting the Christian Faith''Crusades

The first Billy Graham Crusade was held on September 13–21, 1947, at the Civic Auditorium inGrand Rapids, Michigan

Grand Rapids is the largest city and county seat of Kent County, Michigan, United States. With a population of 198,917 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 200,117 in 2024, Grand Rapids is the List of municipalities ...

, and was attended by 6,000 people. Graham was 28 years old then, and would rent a large venue (such as a stadium, park, or even a street); as the crowds became larger, he arranged for a group of up to 5,000 people to sing in a choir. He would preach the gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

and invite individuals to come forward (a practice begun by Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 22, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Mas ...

); such people were called "inquirers" and were given the chance to speak one-on-one with a counselor to clarify questions and pray together. The inquirers were often given a copy of the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

or a Bible study booklet.

In 1949, Graham scheduled a series of revival meeting

A revival meeting is a series of Christian religious services held to inspire active members of a church body to gain new converts and to call sinners to repent. Those who lead revival services are known as revivalists (or evangelists). Nineteent ...

s in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, for which he erected circus tents in a parking lot. He attracted national media coverage, especially in the conservative Hearst chain of newspapers, although Hearst and Graham never met. The crusade event ran for eight weeks–five weeks longer than originally planned. Graham became a national figure, with heavy coverage from the wire services and national magazines. Pianist Rudy Atwood

Rudolph Atwood (December 16, 1912 – October 16, 1992) was an American Christian music pianist, known primarily for his years as accompanist on the long-running ''Old Fashioned Revival Hour'' radio program led by Charles E. Fuller from 1937 to ...

, who played for the tent meetings, wrote that they "rocketed Billy Graham into national prominence, and resulted in the conversion of a number of show-business personalities".

In 1953, Graham was offered a five-year, $1 million contract from NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

to appear on television opposite Arthur Godfrey

Arthur Morton Godfrey (August 31, 1903 – March 16, 1983) was an American radio and television broadcaster and entertainer. At the peak of his success, in the early to mid-1950s, Godfrey was heard on radio and seen on television up to six days ...

, but he had prior commitments and turned-down the offer to continue his live touring revivals. Graham held crusades in London that lasted 12 weeks, and a New York City crusade at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as the Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh and Eighth Avenue (Manhattan), Eig ...

, in 1957, ran nightly for 16 weeks. At a 1973 rally, attended by 100,000 people, in Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, South Africa—the first large mixed-race event in apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

South Africa—Graham openly declared that "apartheid is a sin". In Moscow, Russia

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, in 1992, one-quarter of the 155,000 people in Graham's audience went-forward at his call. During his crusades, he frequently used the altar call song, " Just As I Am". In 1995, during the Global Mission event, he preached a sermon at Estadio Hiram Bithorn in San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John (disambiguation), Saint John, most commonly refers to:

* San Juan, Puerto Rico

* San Juan, Argentina

* San Juan, Metro Manila, a highly urbanized city in the Philippines

San Juan may also refer to:

Places Arge ...

, Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, that was transmitted by satellite to 185 countries and translated into 116 languages.

By the time of his last crusade in 2005 in New York City, he had preached 417 live crusades, including 226 in the US and 195 abroad.

By the time of his last crusade in 2005 in New York City, he had preached 417 live crusades, including 226 in the US and 195 abroad.

Student ministry

Graham spoke at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship's Urbana Student Missions Conference at least nine times – in 1948, 1957, 1961, 1964, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1984, and 1987. At each Urbana conference, he challenged the thousands of attendees to make a commitment to follow Jesus Christ for the rest of their lives. He often quoted a six-word phrase that was reportedly written in the Bible of William Whiting Borden, the son of a wealthy silver magnate: "No reserves, no retreat, no regrets". Borden had died in Egypt on his way to the mission field. Graham also held evangelistic meetings on a number of college campuses: at the University of Minnesota during InterVarsity's "Year of Evangelism" in 1950–51, a 4-day mission at Yale University in 1957, and a week-long series of meetings at the University of North Carolina's Carmichael Auditorium in September 1982. In 1955, he was invited by Cambridge University students to lead the mission at the university; the mission was arranged by theCambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union

The Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union, usually known as CICCU, is the University of Cambridge's most prominent student Christian organisation, and was the first university Christian Union to have been founded. It was formed in 1877, bu ...

, with London pastor-theologian John Stott

John Robert Walmsley Stott (27 April 1921 – 27 July 2011) was a British Anglican pastor and theologian who was noted as a leader of the worldwide evangelical movement. He was one of the principal authors of the Lausanne Covenant in 1974. I ...

serving as Graham's chief assistant. This invitation was greeted with much disapproval in the correspondence columns of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

''.

Evangelistic association

In 1950, Graham founded theBilly Graham Evangelistic Association

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) is a non-profit Christian outreach organization that promotes multimedia evangelism, conducts evangelistic crusades, and engages in disaster response. The BGEA operates the Billy Graham Train ...

(BGEA) with its headquarters in Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

. The association relocated to Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina and the county seat of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 United ...

, in 2003, and maintains a number of international offices, such as in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

. BGEA ministries have included:

* ''Hour of Decision

The ''Hour of Decision'' was a live weekly radio broadcast produced by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. First broadcast in 1950 by the American Broadcasting Company, it was a half-hour program featuring sermons from noted evangelist ...

'', a weekly radio program broadcast around the world for 66 years (1950–2016)

* Mission television specials broadcast in almost every market in the US and Canada

* A syndicated newspaper column, ''My Answer'', carried by newspapers across the United States and distributed by Tribune Content Agency

Tribune Content Agency (TCA) is a syndication company owned by Tribune Publishing. TCA had previously been known as the Chicago Tribune Syndicate, the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate (CTNYNS), Tribune Company Syndicate, and Tribune Media ...

* ''Decision'' magazine, the official publication of the association

* ''Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "eva ...

,'' started in 1956 with Carl F. H. Henry as its first editor

* Passageway.org, the website for a youth discipleship program created by BGEA

* World Wide Pictures

World Wide Pictures (WWP) was a film distributor and production company established as a subsidiary of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) in 1951. It is involved in the production and distribution of evangelistic films, the produc ...

, which has produced and distributed more than 130 films

In April 2013, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association started "My Hope With Billy Graham", the largest outreach in its history. It encouraged church members to spread the gospel in small group meetings, after showing a video message by Graham. "The idea is for Christians to follow the example of the disciple Matthew in the New Testament and spread the gospel in their own homes." "The Cross" video is the main program in the My Hope America series, and was also broadcast the week of Graham's 95th birthday.

Civil rights movement

Graham's early crusades were segregated, but he began adjusting his approach in the 1950s. During a 1953 rally in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Graham tore down the ropes that organizers had erected to segregate the audience into racial sections. In his memoirs, he recounted that he told two ushers to leave the barriers down "or you can go on and have the revival without me." During a sermon held atVanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private university, private research university in Nashville, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provide ...

in Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

on August 23, 1954, he warned a white audience, "Three-fifths of the world is not white. They are rising all over the world. We have been proud and thought we were better than any other race, any other people. Ladies and gentlemen, I want to tell you that we are going to stumble into hell because of our pride."

In 1957, Graham's stance towards integration became more publicly shown when he allowed black ministers Thomas Kilgore and Gardner C. Taylor to serve as members of his New York Crusade's executive committee. He also invited Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, whom he first met during the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

in 1955, to join him in the pulpit at his 16-week revival in New York City, where 2.3 million gathered at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as the Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh and Eighth Avenue (Manhattan), Eig ...

, Yankee Stadium

Yankee Stadium is a baseball stadium located in the Bronx in New York City. It is the home field of Major League Baseball’s New York Yankees and New York City FC of Major League Soccer.

The stadium opened in April 2009, replacing the Yankee S ...

, and Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and Neighborhoods in New York City, neighborhood in the Midtown Manhattan section of New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway (Manhattan), ...

to hear them. Graham recalled in his autobiography that during this time, he and King developed a close friendship and that he was eventually one of the few people who referred to King as "Mike", a nickname which King asked only his closest friends to call him. Following King's assassination in 1968, Graham mourned that the US had lost "a social leader and a prophet". In private, Graham advised King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., ...

(SCLC).

Despite their friendship, tensions between Graham and King emerged in 1958, when the sponsoring committee of a crusade that took place in San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Texas, on July 25 arranged for Graham to be introduced by that state's segregationist governor, Price Daniel

Marion Price Daniel Sr. (October 10, 1910August 25, 1988), was an American jurist and politician who served as a Democratic Party (United States), Democratic United States Senate, U.S. Senator and the 38th governor of Texas. He was appointed by Ly ...

. On July 23, King sent a letter to Graham and informed him that allowing Daniel to speak at a crusade which occurred the night before the state's Democratic Primary "can well be interpreted as your endorsement of racial segregation and discrimination." Graham's advisor, Grady Wilson, replied to King that "even though we do not see eye to eye with him on every issue, we still love him in Christ." Though Graham's appearance with Daniel dashed King's hopes of holding joint crusades with Graham in the Deep South, the two remained friends; the next year King told a Canadian television audience that Graham had taken a "very strong stance against segregation." Graham and King would also come to differ on the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. After King's " Beyond Vietnam" speech denouncing US intervention in Vietnam, Graham castigated him and others for their criticism of US foreign policy.

By the middle of 1960, King and Graham traveled together to the Tenth Baptist World Congress of the Baptist World Alliance

The Baptist World Alliance (BWA) is an international communion of Baptists, with an estimated 51 million people from 266 member bodies in 134 countries and territories as of 2024. A voluntary association of Baptist churches, the BWA accounts f ...

. In 1963, Graham posted bail for King to be released from jail during the Birmingham (Alabama) campaign, according to Michael Long, and the King Center acknowledged that Graham had bailed King out of jail during the Albany Movement

The Albany Movement was a desegregation and voters' rights coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. This movement was founded by local black leaders and ministers, as well as members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Commi ...

, although historian Steven Miller told CNN he could not find any proof of the incident. Graham held integrated crusades in Birmingham on Easter of 1964, in the aftermath of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and toured Alabama again in the wake of the violence that accompanied the first Selma to Montgomery march

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-Amer ...

in 1965.

Following Graham's death, former SCLC official and future Atlanta politician Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christia ...

(who spoke alongside Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was the wife of Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his assassination in 1968. As an advocate for African-Ameri ...

at Graham's 1994 crusade in Atlanta), acknowledged his friendship with Graham and stated that Graham did in fact travel with King to the 1965 European Baptist Convention. Young also claimed that Graham had often invited King to his crusades in the Northern states. Former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

(SNCC) leader and future United States Congressman John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American civil rights activist and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

also credited Graham as a major inspiration for his activism.Billy Graham passes away: Congressman John Lewis remembers the reverend11 Alive, February 21, 2018, Accessed October 6, 2020 Lewis described Graham as a "saint" and someone who "taught us how to live and who taught us how to die". Graham's faith prompted his maturing view of race and segregation. He told a member of the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

that integration was necessary, primarily for religious reasons. "There is no scriptural basis for segregation," Graham argued. "The ground at the foot of the cross is level, and it touches my heart when I see whites standing shoulder to shoulder with blacks at the cross."

Lausanne Movement

The friendship between Graham and John Stott led to a further partnership in theLausanne Movement

The Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, more commonly known as the Lausanne Movement, is a global movement that mobilizes Christian leaders to collaborate for world evangelization. The movement's fourfold vision is to see 'the gospel for e ...

, of which Graham was a founder. It built on Graham's 1966 World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. In collaboration with ''Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "eva ...

'', Graham convened what ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine described as "a formidable forum, possibly the widest–ranging meeting of Christians ever held" with 2,700 participants from 150 nations gathering for the International Congress on World Evangelization. Women were represented by Millie Dienert, who chaired the prayer committee. This took place in Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, Switzerland (July 16–25, 1974), and the movement which ensued took its name from the host city. Its purpose was to strengthen the global church for world evangelization, and to engage ideological and sociological trends which bore on this. Graham invited Stott to be chief architect of the Lausanne Covenant

The Lausanne Covenant is a July 1974 religious manifesto promoting active worldwide Christian evangelism. One of the most influential documents in modern evangelicalism, it was written at the First International Congress on World Evangelization ...

, which issued from the Congress and which, according to Graham: "helped challenge and unite evangelical Christians in the great task of world evangelization." The movement remains a significant fruit of Graham's legacy, with a presence in nearly every nation.

Multiple roles

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

.

He served as a trustee of the International Mission Board

The International Mission Board (or IMB, formerly the Foreign Mission Board) is a Baptist Christian missionary society affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). The headquarters is in Richmond, Virginia.

History

Thousands of sma ...

in the late 1950s and trustee of the SBC's Radio and Television Commission in the late 1960s.

Graham deliberately reached into the secular world as a bridge builder. For example, as an entrepreneur he built his own pavilion for the 1964 New York World's Fair

The 1964 New York World's Fair (also known as the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair) was an world's fair, international exposition at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York City, United States. The fair included exhibitions, activ ...

. He appeared as a guest on a 1969 Woody Allen

Heywood Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg; November 30, 1935) is an American filmmaker, actor, and comedian whose career spans more than six decades. Allen has received many List of awards and nominations received by Woody Allen, accolade ...

television special, in which he joined the comedian in a witty exchange on theological matters. During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Graham became the first evangelist of note to speak behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

, addressing large crowds in countries throughout Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union, calling for peace. During the apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

era, Graham consistently refused to visit South Africa until its government allowed integrated seating for audiences. During his first crusade there in 1973, he openly denounced apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

. Graham also corresponded with imprisoned South African leader Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

during the latter's 27-year imprisonment.

In 1984, he led a series of summer meetings—Mission England—in the United Kingdom, and he used outdoor football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

(soccer) fields for his venues.

Graham was interested in fostering evangelism around the world. In 1983, 1986 and 2000 he sponsored, organized and paid for massive training conferences for Christian evangelists; this was, at the time, the largest representation of nations ever held. Over 157 nations were gathered in 2000 at the RAI Convention Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. At one revival in Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

, South Korea, Graham attracted more than one million people to a single service. He appeared in China in 1988; for his wife, Ruth, this was a homecoming, since she had been born in China to missionary parents. He appeared in North Korea in 1992.

On October 15, 1989, Graham received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a landmark which consists of 2,813 five-pointed terrazzo-and-brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in the Hollywood, Los Angeles, Hollywood dist ...

. He was the only person functioning as a minister who received a star in that capacity.

On September 22, 1991, Graham held his largest event in North America on the Great Lawn of Manhattan's Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

. City officials estimated that more than 250,000 were in attendance. In 1998, Graham spoke to a crowd of scientists and philosophers at the Technology, Entertainment, Design Conference.

On September 14, 2001 (only three days after the World Trade Center attacks), Graham was invited to lead a service at Washington National Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Episcopal Diocese of Washington, commonly known as Washington National Cathedral or National Cathedral, is a cathedral of the Episcopal Church. The cathedral is located in Wa ...

; the service was attended by President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

and past and present leaders. He also spoke at the memorial service following the Oklahoma City bombing

The Oklahoma City bombing was a domestic terrorist truck bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, United States, on April 19, 1995. The bombing remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history. Perpetr ...

in 1995. On June 24–26, 2005, Graham began what he said would be his last North American crusade: three days at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park (often referred to as Flushing Meadows Park or simply Flushing Meadows or Corona Park) is a public park in the northern part of Queens in New York City, New York, U.S. It is bounded by Interstate 678 (New York), ...

in the borough of Queens, New York City. On the weekend of March 11–12, 2006, Graham held the "Festival of Hope" with his son, Franklin Graham

William Franklin Graham III (born July 14, 1952) is an American evangelist and missionary in the evangelical movement. He frequently engages in Christian revival tours and political commentary. The son of Billy Graham, he is president and CEO ...

. The festival was held in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, which was recovering from Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a powerful, devastating and historic tropical cyclone that caused 1,392 fatalities and damages estimated at $125 billion in late August 2005, particularly in the city of New Orleans and its surrounding area. ...

.

Graham prepared one last sermon, "My Hope America", which was released on DVD and played around America and possibly worldwide between November 7–10, 2013. November 7 was Graham's 95th birthday, and he hoped to cause a revival.

Later life

Graham said that his planned retirement was a result of his failing health; he had suffered fromhydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up within the brain, which can cause pressure to increase in the skull. Symptoms may vary according to age. Headaches and double vision are common. Elderly adults with n ...

from 1992 on. In August 2005, Graham appeared at the groundbreaking for his library in Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina and the county seat of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 United ...

. Then 86, he used a walker during the ceremony. On July 9, 2006, he spoke at the Metro Maryland Franklin Graham Festival, held in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, Maryland, at Oriole Park at Camden Yards

Oriole Park at Camden Yards, commonly known as Camden Yards, is a ballpark in Baltimore, Maryland. It is the home of Major League Baseball (MLB)'s Baltimore Orioles, and the first of the "retro" major league ballparks constructed during the ...

.

In April 2010, Graham was 91 and experiencing substantial vision, hearing, and balance loss when he made a rare public appearance at the re-dedication of the renovated Billy Graham Library.

There was controversy within his family over Graham's proposed burial place. He announced in June 2007 that he and his wife would be buried alongside each other at the Billy Graham Library in his hometown of Charlotte. Graham's younger son Ned argued with older son Franklin about whether burial at a library would be appropriate. Ruth Graham had said that she wanted to be buried in the mountains at the Billy Graham Training Center at The Cove near Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville ( ) is a city in Buncombe County, North Carolina, United States. Located at the confluence of the French Broad River, French Broad and Swannanoa River, Swannanoa rivers, it is the county seat of Buncombe County. It is the most populou ...

, where she had lived for many years; Ned supported his mother's choice. Novelist Patricia Cornwell

Patricia Cornwell (born Patricia Carroll Daniels; June 9, 1956) is an American crime writer. She is known for her best-selling novels featuring medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, of which the first was inspired by a series of sensational murders ...

, a family friend, also opposed burial at the library, calling it a tourist attraction. Franklin wanted his parents to be buried at the library site. When Ruth Graham died, it was announced that they would be buried at the library site.

In 2011, when asked if he would have done things differently, he said he would have spent more time at home with his family, studied more, and preached less.Sarah Pulliam BaileyQ & A: Billy Graham on Aging, Regrets, and Evangelicals

christianitytoday.com, USA, January 21, 2011 Additionally, he said he would have participated in fewer conferences. He also said he had a habit of advising evangelists to save their time and avoid having too many commitments.

Politics

After his close relationships withLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, Graham tried to avoid explicit partisanship. Bailey says: "He declined to sign or endorse political statements, and he distanced himself from the Christian right ... His early years of fierce opposition to communism gave way to pleas for military disarmament and attention to AIDS, poverty and environmental threats."

Graham was a lifelong registered member of the Democratic Party. In 1960, he opposed the candidacy of John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, fearing that Kennedy, as a Catholic, would be bound to follow the Pope. Graham worked "behind the scenes" to encourage influential Protestant ministers to speak out against Kennedy. During the 1960 campaign, Graham met with a conference of Protestant ministers in Montreux

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, Swiss municipality and List of towns in Switzerland, town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Swiss Alps, Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut (district), Riviera-Pays ...

, Switzerland, to discuss their mobilization of congregations to defeat Kennedy. According to the PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

'' Frontline'' program, ''God in America'', Graham organized a meeting of hundreds of Protestant ministers in Washington, D.C., in September 1960 for this purpose; the meeting was led by Norman Vincent Peale

Norman Vincent Peale (May 31, 1898 – December 24, 1993) was an American Protestant clergyman, and an author best known for popularizing the concept of positive thinking, especially through his best-selling book '' The Power of Positiv ...

.Study Guide: ''God in America'', Episode 5, "The Soul of America"PBS Frontline, October 2010, program available online This was shortly before Kennedy's speech in

Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

, Texas, on the separation of church and state; the speech was considered to be successful in meeting the concerns of many voters. After his election, Kennedy invited Graham to play golf in Palm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. Located on a barrier island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from West Palm Beach, Florida, West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach, Florida, ...

, after which Graham acknowledged Kennedy's election as an opportunity for Catholics and Protestants to come closer together. After they had discussed Jesus Christ at that meeting, the two remained in touch, meeting for the last time at a National Day of Prayer

The National Day of Prayer is an annual day of observance designated by the United States Congress and held on the first Thursday of May, when people are asked "to turn to God in prayer and meditation". The president is required by law () to si ...

meeting in February 1963. In his autobiography, Graham claimed to have felt an "inner foreboding" in the week before Kennedy's assassination, and to have tried to contact him to say, "Don't go to Texas!"

Graham opposed the large majority of abortions, but supported it as a legal option in a very narrow range of circumstances: rape, incest

Incest ( ) is sexual intercourse, sex between kinship, close relatives, for example a brother, sister, or parent. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by lineag ...

, and the life of the mother. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) is a non-profit Christian outreach organization that promotes multimedia evangelism, conducts evangelistic crusades, and engages in disaster response. The BGEA operates the Billy Graham Train ...

states that "Life is sacred, and we must seek to protect all human life: the unborn, the child, the adult, and the aged."

Graham leaned toward the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

during the presidency of Richard Nixon, whom he had met and befriended as vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

. He did not completely ally himself with the later religious right, saying that Jesus did not have a political party. He gave his support to various political candidates over the years.

In 2007, Graham explained his refusal to join Jerry Falwell

Jerry Laymon Falwell Sr. (August 11, 1933 – May 15, 2007) was an American Baptist pastor, televangelist, and conservatism in the United States, conservative activist. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, a megachurch ...

's Moral Majority

The Moral Majority was an American political organization and movement associated with the Christian right and the Republican Party in the United States. It was founded in 1979 by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell Sr. and associates, and dissolv ...

in 1979, saying: "I'm for morality, but morality goes beyond sex to human freedom and social justice. We as clergy know so very little to speak with authority on the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

or superiority of armaments. Evangelists cannot be closely identified with any particular party or person. We have to stand in the middle to preach to all people, right and left. I haven't been faithful to my own advice in the past. I will be in the future."

According to a 2006 ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

'' interview, "For Graham, politics is a secondary to the Gospel ... When ''Newsweek'' asked Graham whether ministers – whether they think of themselves as evangelists, pastors or a bit of both – should spend time engaged with politics, he replied: 'You know, I think in a way that has to be up to the individual as he feels led of the Lord. A lot of things that I commented on years ago would not have been of the Lord, I'm sure, but I think you have some – like communism, or segregation, on which I think you have a responsibility to speak out.'"

In 2011, although grateful to have met politicians who have spiritual needs like everyone else, he said he sometimes crossed the line and would have preferred to avoid politics.

In 2012, Graham endorsed the Republican presidential candidate, Mitt Romney

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American businessman and retired politician. He served as a United States Senate, United States senator from Utah from 2019 to 2025 and as the 70th governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007 ...

. Shortly after, apparently to accommodate Romney, who is a Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

, references to Mormonism as a religious cult ("A cult is any group which teaches doctrines or beliefs that deviate from the biblical message of the Christian faith.") were removed from Graham's website. Observers have questioned whether the support of Republican and religious right politics on issues such as same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same legal Legal sex and gender, sex. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 38 countries, with a total population of 1.5 ...

coming from Graham – who stopped speaking in public or to reporters – in fact reflects the views of his son, Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People and characters

* Franklin (given name), including list of people and characters with the name

* Franklin (surname), including list of people and characters with the name

* Franklin (class), a member of a historic ...

, head of the BGEA. Franklin denied this, and said that he would continue to act as his father's spokesperson rather than allowing press conferences. In 2016, according to his son Franklin, Graham voted for Donald Trump. This statement has been disputed by other children and grandchildren of Billy Graham, who argue that he was too ill to vote (even absentee), and who reiterated that Billy Graham's stated greatest regret in life was becoming involved in partisan politics.

Pastor to presidents

Graham had a personal audience with many sitting US presidents, from

Graham had a personal audience with many sitting US presidents, from Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

to Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

– 12 consecutive presidents. After meeting with Truman in 1950, Graham told the press he had urged the president to counter communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

in North Korea. Truman disliked him and did not speak with him for years after that meeting. Later he always treated his conversations with presidents as confidential.

Truman made his contempt for Graham public. He wrote about Graham in his 1974 autobiography ''Plain Speaking'': "But now we've got just this one evangelist, this Billy Graham, and he's gone off the beam. He's ... well, I hadn't ought to say this, but he's one of those counterfeits I was telling you about. He claims he's a friend of all the presidents, but he was never a friend of mine when I was President. I just don't go for people like that. All he's interested in is getting his name in the paper."

Graham became a regular visitor during the tenure of Dwight D. Eisenhower. He purportedly urged him to intervene with federal troops in the case of the Little Rock Nine

The Little Rock Nine were a group of nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was followed by the Little Rock Crisis, in which the students were initially prevented from entering th ...

to gain admission of black students to public schools. House Speaker Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

persuaded Congress to allow Graham to conduct the first religious service on the steps of the Capitol building in 1952. Eisenhower asked for Graham while on his deathbed.

Graham met and became a close friend of Vice President Richard Nixon, and supported Nixon, a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

, for the 1960 presidential election. He convened an August strategy session of evangelical leaders in Montreux, Switzerland

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Swiss municipality and town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps. It belongs to the Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut district in the canton of Vaud, having a population of approximately 26,500, with about 85,00 ...

, to plan how best to oppose Nixon's Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

opponent, Senator John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

. Though a registered Democrat, Graham also maintained firm support of aggression against the foreign threat of communism and strongly sympathized with Nixon's views regarding American foreign policy. Thus, he was more sympathetic to Republican administrations.

On December 16, 1963, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was impressed by the way Graham had praised the work of his great-grandfather, George Washington Baines, invited Graham to the White House to receive spiritual counseling. After this visit, Johnson frequently called on Graham for more spiritual counseling as well as companionship. As Graham recalled to his biographer Frady, "I almost used the White House as a hotel when Johnson was President. He was always trying to keep me there. He just never wanted me to leave."