Berlin Congress on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the

After the Bulgarian April Uprising in 1876 and the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Russia had liberated almost all of the Ottoman European possessions. The Ottomans recognised

After the Bulgarian April Uprising in 1876 and the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Russia had liberated almost all of the Ottoman European possessions. The Ottomans recognised

The principal mission of the participants at the Congress was to deal a fatal blow to the burgeoning movement of

The principal mission of the participants at the Congress was to deal a fatal blow to the burgeoning movement of

File:Divided Bulgaria after the Congress of Berlin.jpg, Allegorical depiction of Bulgarian autonomy after the Treaty of Berlin.

Lithograph by Nikolai Pavlovich File:Greek-Delegation-Berlin-Congress.jpg, Greek Delegation in the Berlin Congress

online

* * *

The History of the Eastern Question

'. {{DEFAULTSORT:Congress of Berlin 1878 conferences 1878 in Germany 1878 in international relations 19th century in Berlin 19th-century diplomatic conferences Diplomatic conferences in Germany History of the Balkans July 1878 June 1878 Late modern Europe Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

on the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The Congress was the result of escalating tensions; particularly British opposition to Russian hegemony over the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, through the creation of a Russian-aligned ' Greater Bulgaria'. To secure the European balance of power in favour of its splendid isolation achieved after the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, Britain stationed the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

near Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to enforce British demands. To avoid war, Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of the newly formed German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, was asked to mediate a solution that would restore the Ottoman Empire's position as a counterbalance to Russian influence in the Mediterranean and the Balkans, in line with the principles of the 1856 Treaty of Paris.

Attended by delegates from Europe's then six great powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

: Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

; the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

as well as representatives of four Balkan states (Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

), the Congress culminated in the Treaty of Berlin (13 July 1878). This agreement essentially dismantled the autonomous Greater Bulgarian State envisaged at San Stefano, and reorganised the borders of south-eastern Europe. The main results were the Austro-Hungarian forcible occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the British de facto annexation of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

under false pretenses, and the formal recognition of the self-declared independence of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro; allies of Russia in the previous war. While the settlement averted war, it exacerbated nationalist grievances in the Balkans and deepened the rivalry between Britain and Russia ( The Great Game), contributing to long-term regional instability that foreshadowed the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

and World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

As mediator of the Congress, Otto von Bismarck negotiated along the lines laid down by Britain in its secret negotiations before the Congress. He also wanted to avoid Russian domination of the Balkans, or the formation of a Greater Bulgaria, and to keep Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in Ottoman hands. Finally, Bismarck helped to secure civil rights for Jews in the region, as a precondition for international recognition of the newly formed states.

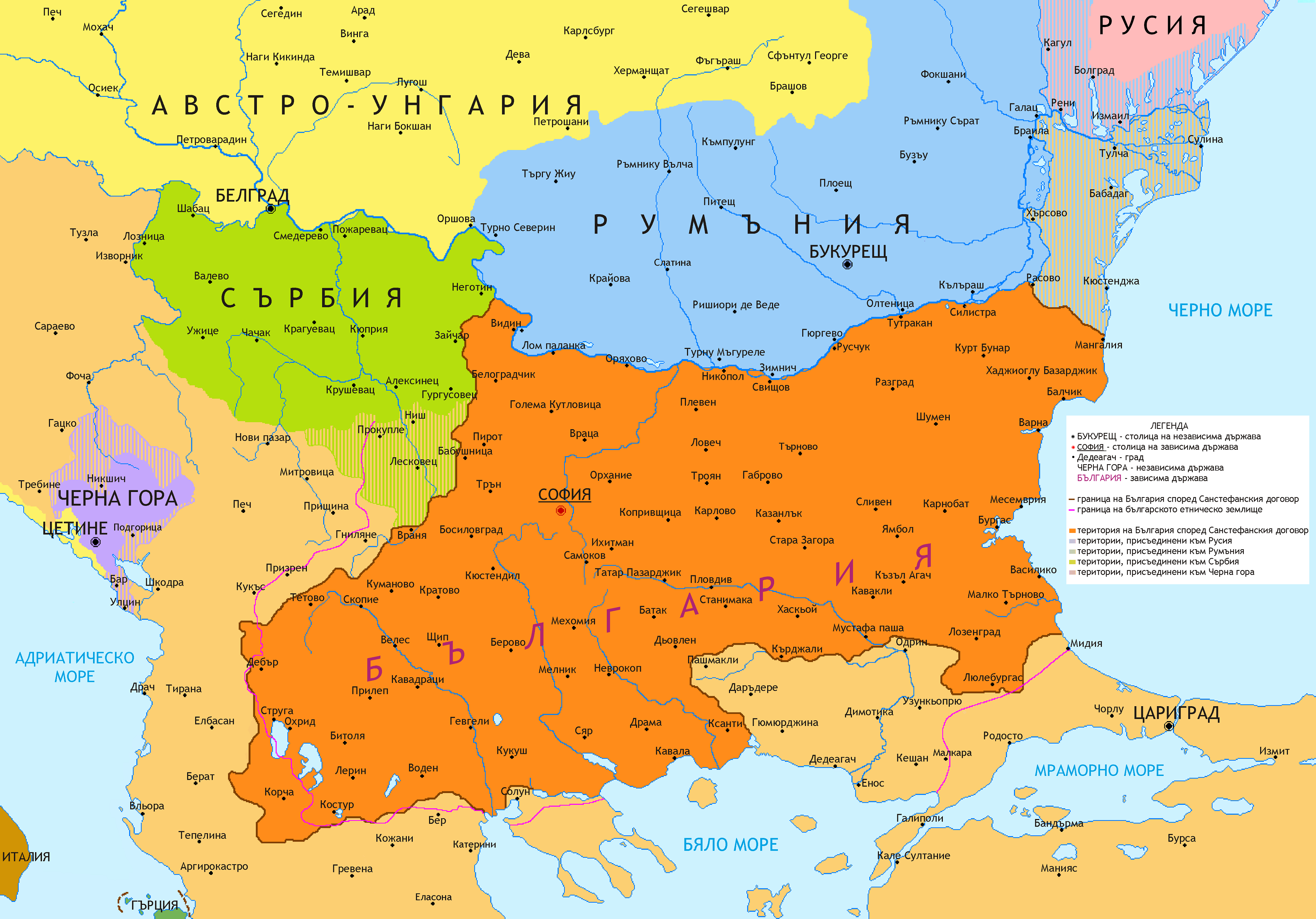

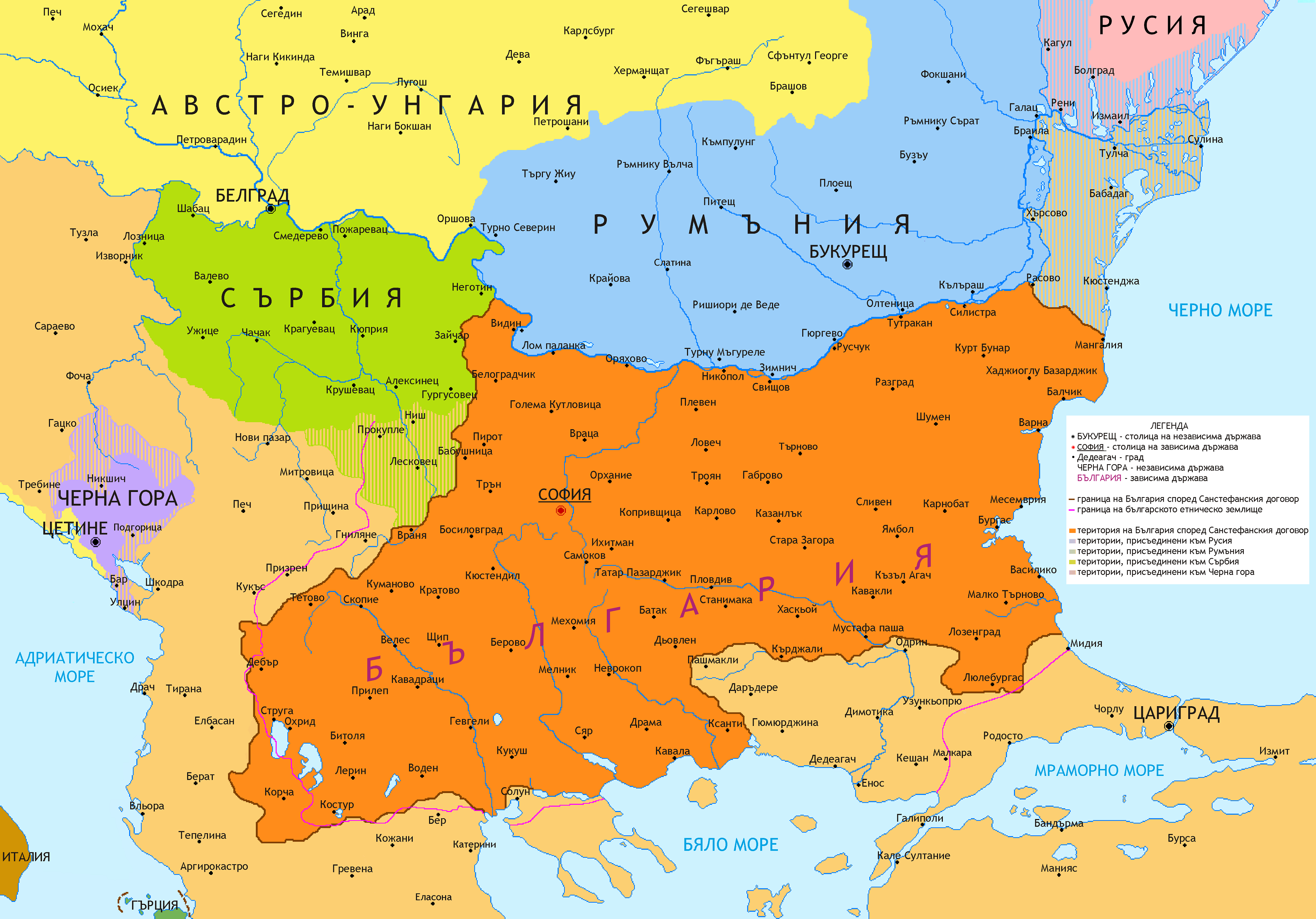

The affected territories were instead granted varying degrees of independence. Romania became fully independent, though was forced to give part of Bessarabia

Bessarabia () is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Bessarabia lies within modern-day Moldova, with the Budjak region covering the southern coa ...

to Russia, and gained Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

. Serbia and Montenegro were also granted full independence but lost territory, with Austria-Hungary occupying the Sanjak of Novi Pazar

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Novopazarski sandžak, Новопазарски санџак; ) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and 1902. The Ottoman rule ...

along with Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

. Britain took possession of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. Of the territory that remained within the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

was made a semi-independent principality, Eastern Rumelia became a special administration, and the region of Macedonia was returned to the Ottomans on condition of reforms to its governance.

The results were initially hailed as a success for peace in the region, but most of the participants were not satisfied with the outcome. The Ottomans were humiliated and had their weakness confirmed as the " sick man of Europe". Russia resented the lack of rewards, despite having won the war that the conference was supposed to resolve, and felt humiliated by the other great powers in their rejection of the San Stefano settlement. Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece all received far less than they thought they deserved, especially Bulgaria which was left with less than half of the territory envisioned by the Treaty of San Stefano. Bismarck became hated by Russian nationalists and Pan-Slavists, and later found that he had tied Germany too closely to Austria-Hungary in the Balkans. Although Austria-Hungary gained substantial territory, this angered the South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic people who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, ...

and led to decades of tensions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, culminating in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was one of the key events that led to World War I. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg ...

.

In the long term, the settlement led to rising tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary, and disputes over nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

in the Balkans. Grievances with the results of the congress festered until they exploded in the First and Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

s (1912 and 1913 respectively). Continuing nationalism in the Balkans was was a major factor for the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914.

Background

In the decades leading up to the congress, Russia and the Balkans had been gripped byPan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South ...

, a movement to unite all the Balkan Slavs under one rule. The Treaty of San Stefano, which had created a " Greater Bulgaria", was opposed as a display of Pan-Slavic hegemonic ambition in southeastern Europe. In Imperial Russia, Pan-Slavism meant the creation of a unified Slavic state, under Russian direction, and was essentially a byword for Russian conquest of the Balkan peninsula. The realisation of the goal would have given Russia control of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

and the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

, thus economic control of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

and substantially greater geopolitical power. Pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking people, and possibly also non-German Germanic peoples – into a sin ...

and Pan-Italianism reflected similar nationalist desires and had resulted in two unifications; it took different forms in the various Slavic nations.

Balkan Slavs felt they needed both an equivalent to Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

to serve as a base and an outside sponsor corresponding to France. The state that was meant to serve as the locus for unification of the Balkans under a "Slavic" rule was not always clear, as initiative wafted between Serbia and Bulgaria. Italian rhetoric by contrast cast Romania as Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, a "second Piedmont".

The recognition of the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

by the Ottomans in 1870 had been intended to separate the Bulgarians, religiously from the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the List of ecumenical patriarchs of Constantinople, archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox ...

, and politically from Serbia. Pan-Slavism required the end of Ottoman rule in the Balkans. How and whether that goal would be realised was the major question to be answered at the Congress of Berlin.

Great powers in the Balkans

The Balkans were a major stage for competition between the Europeangreat powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

in the second half of the 19th century. Britain and Russia had interests in the fate of the Balkans. Russia was interested in the region, both ideologically, as a pan-Slavist unifier, and practically, to secure greater control of the Mediterranean. Britain was interested in preventing Russia from accomplishing its goals. Furthermore, the Unifications of Italy and of Germany had stymied the ability of a third European power, Austria-Hungary, to expand its domain to the southwest any further. Germany, as the most powerful continental nation since the 1871 Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

had little direct interest in the settlement and so was the only power that could mediate the Balkan question credibly.

Russia and Austria-Hungary, the two powers that were most invested in the fate of the Balkans, were allied with Germany in the conservative League of Three Emperors, which had been founded to preserve the monarchies of Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

. The Congress of Berlin was thus mainly a dispute among supposed allies of Bismarck. The German Empire, the arbiter of the discussion, would thus have to choose before the end of the congress which of their allies to support. That decision was to have direct consequences on the future of European geopolitics.

Ottoman brutality in the Serbian–Ottoman War and the violent suppression of the Herzegovina Uprising fomented political pressure within Russia, which saw itself as the protector of the Serbs, to act against the Ottoman Empire. David MacKenzie writes that within Russia "sympathy for the Serbian Christians existed in Court circles, among nationalist diplomats, and in the lower classes, and was actively expressed through the Slav committees".

Eventually, Russia sought and obtained Austria-Hungary's pledge of benevolent neutrality

A neutral country is a state that is neutral towards belligerents in a specific war or holds itself as permanently neutral in all future conflicts (including avoiding entering into military alliances such as NATO, CSTO or the SCO). As a type o ...

in the coming war, in return for ceding Bosnia Herzegovina to Austria-Hungary in the Budapest Convention of 1877. act: The Berlin Congress in effect postponed resolution of the Bosnian question and left Bosnia and Herzegovina under Habsburg control. This was the goal of Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count Gyula Andrássy.

Treaty of San Stefano

After the Bulgarian April Uprising in 1876 and the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Russia had liberated almost all of the Ottoman European possessions. The Ottomans recognised

After the Bulgarian April Uprising in 1876 and the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Russia had liberated almost all of the Ottoman European possessions. The Ottomans recognised Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

as independent, and the territories of all three of them were expanded. Russia created a large Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

as an autonomous vassal of the sultan. That expanded Russia's sphere of influence to encompass the entire Balkans, which alarmed other powers in Europe. Britain, which had threatened war with Russia if it occupied Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, and France did not want another power meddling in either the Mediterranean or the Middle East, where both powers were prepared to make large colonial gains. Austria-Hungary desired Habsburg control over the Balkans, and Germany wanted to prevent its ally from going to war. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

thus called the Congress of Berlin to discuss the partition of the Ottoman Balkans among the European powers and to preserve the League of Three Emperors in the face of the spread of European liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

.

The Congress was attended by Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, Russia and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Delegates from Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro attended the sessions that concerned their states, but they were not members.

The Congress was solicited by Russia's rivals, particularly Austria-Hungary and Britain, and was hosted in 1878 by Bismarck. It proposed and ratified the Treaty of Berlin. The meetings were held at Bismarck's Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery () was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared since 1875, was the fo ...

, the former Radziwill Palace, from 13 June to 13 July 1878. The congress revised or eliminated 18 of the 29 articles in the Treaty of San Stefano. Furthermore, by using as a foundation the Treaties of Paris (1856) and of Washington (1871), the treaty rearranged the East.

Other powers' fear of Russian influence

The principal mission of the participants at the Congress was to deal a fatal blow to the burgeoning movement of

The principal mission of the participants at the Congress was to deal a fatal blow to the burgeoning movement of pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South ...

. The movement caused serious concern in Berlin and even more so in Vienna, which was afraid that the repressed Slavic nationalities would revolt against the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

. The British and the French governments were nervous about both the diminishing influence of the Ottoman Empire and the cultural expansion of Russia to the south, where both Britain and France were poised to colonise Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. By the Treaty of San Stefano, the Russians, led by Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov, had managed to create in Bulgaria an autonomous principality, under the nominal rule of the Ottoman Empire.

That sparked the Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British Empire, British and Russian Empire, Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Emirate of Afghanistan, Afghanistan, Qajar Iran, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonia ...

, the massive British fear of the growing Russian influence in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. The new principality, including a very large portion of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

as well as access to the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

, could easily threaten the Dardanelles Straits, which separate the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

The arrangement was not acceptable to the British, who considered the entire Mediterranean to be a British sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

and saw any Russian attempt to gain access there as a grave threat to British power. On 4 June, before the Congress opened on 13 June, British Prime Minister Lord Beaconsfield (Disraeli) had already concluded the Cyprus Convention, a secret alliance with the Ottomans against Russia in which Britain was allowed to occupy the strategically-placed island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. The agreement predetermined Beaconsfield's position during the Congress and led him to issue threats to unleash a war against Russia if it did not comply with Ottoman demands.

Negotiations between Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy and British Foreign Secretary Marquess of Salisbury had already "ended on 6 June by Britain agreeing to all the Austrian proposals relative to Bosnia-Herzegovina about to come before the congress while Austria would support British demands".

Bismarck as host

The Congress of Berlin is frequently viewed as the culmination of the battle between Alexander Gorchakov of Russia andOtto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

of Germany. Both were able to persuade other European leaders that a free and independent Bulgaria would greatly improve the security risks posed by a disintegrating Ottoman Empire. According to historian Erich Eyck, Bismarck supported Russia's position that "Turkish rule over a Christian community (Bulgaria) was an anachronism which undoubtedly gave rise to insurrection and bloodshed and should therefore be ended".Erich Eyck, ''Bismarck and the German Empire'' (New York: W.W. Norton, 1964), pp. 245–46. He used the Great Eastern Crisis

The Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–1878 began in the Ottoman Empire's Rumelia, administrative territories in the Balkan Peninsula in 1875, with the outbreak of several uprisings and wars that resulted in the intervention of international powers, ...

of 1875 as proof of growing animosity in the region.

Bismarck's ultimate goal during the Congress of Berlin was not to upset Germany's status on the international platform. He did not wish to disrupt the League of the Three Emperors by choosing between Russia and Austria as an ally. To maintain peace in Europe, Bismarck sought to convince other European diplomats that dividing up the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

would foster greater stability. One reason that Bismarck was able to mediate the various tensions at the Congress of Berlin was his diplomatic persona. He sought peace and stability when international affairs did not pertain to Germany directly. Since he viewed the current situation in Europe as favourable for Germany, any conflicts between the major European powers that threatened the status quo was against German interests. Also, at the Congress of Berlin, "Germany could not look for any advantage from the crisis" that had occurred in the Balkans in 1875. Therefore, Bismarck claimed impartiality on behalf of Germany at the Congress, which enabled him to preside over the negotiations with a keen eye for foul play.

Though most of Europe went into the Congress expecting a diplomatic show, much like the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, they were to be sadly disappointed. Bismarck, unhappy to be conducting the Congress in the heat of the summer, had a short temper and a low tolerance for malarky. Thus, any grandstanding was cut short by the testy German chancellor. The ambassadors from the small Balkan territories whose fate was being decided were barely even allowed to attend the diplomatic meetings, which were between mainly the representatives of the great powers.

According to Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

, the congress saw a shift in Bismarck's Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' ( ; ) is the approach of conducting diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly following ideological, moral, or ethical premises. In this respect, ...

. Until then, as Germany had become too powerful for isolation, his policy was to maintain the League of the Three Emperors. Now that he could no longer rely on Russia's alliance, he began to form relations with as many potential enemies as possible.

Legacy

Owing to Russia's insistence, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro were all given the status of independent principalities. Russia recovered Southern Bessarabia, which it had annexed at the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–1812, and lost to Moldavia/Romania in 1856, after the end of theCrimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. The Bulgarian state that Russia had created by the Treaty of San Stefano was divided into the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

and Eastern Rumelia, both of which were given nominal autonomy, under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Bulgaria was promised autonomy, and guarantees were made against Turkish interference, but they were largely ignored. Romania received Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

as a compensation for Southern Bessarabia, but even so it did not benefit of substantial gain of territory despite its consistent war effort alongside Russia. Romanians deeply resented the loss of Southern Bessarabia and Russo-Romanian relationship remained very cold for decades. Montenegro obtained Nikšić

Nikšić (Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Никшић, ), is the second largest city in Montenegro, with a total population of 32,046 (2023 census) located in the west of the country, in the centre of the spacious Nikšić field at the foot of Trebjesa ...

, Podgorica

Podgorica ( cnr-Cyrl, Подгорица; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Montenegro, largest city of Montenegro. The city is just north of Lake Skadar and close to coastal destinations on the Adriatic Sea. Histor ...

, Bar and Plav-Gusinje. The Ottoman government, or Porte, agreed to obey the specifications contained in the Organic Law of 1868 and to guarantee the civil rights of non-Muslim subjects. The region of Bosnia-Herzegovina was handed over to the administration of Austria-Hungary, which also obtained the right to garrison the Sanjak of Novi Pazar

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Novopazarski sandžak, Новопазарски санџак; ) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and 1902. The Ottoman rule ...

, a small border region between Montenegro and Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina were put on the fast track to eventual annexation. Russia agreed that Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, the most important strategic section of the Balkans, was too multinational to be part of Bulgaria and permitted it to remain under the Ottoman Empire. Eastern Rumelia, which had its own large Turkish and Greek minorities, became an autonomous province under a Christian ruler, with its capital at Philippopolis. The remaining portions of the original "Greater Bulgaria" became the new state of Bulgaria.

In Russia, the Congress of Berlin was considered to be a dismal failure. After finally defeating the Turks despite many past inconclusive Russo-Turkish wars, many Russians had expected "something colossal", a redrawing of the Balkan borders in support of Russian territorial ambitions. Instead, the victory resulted in an Austro-Hungarian gain on the Balkan front that was brought about by the rest of the European powers' preference for a stronger Austria-Hungarian Empire, which threatened basically no one, to a powerful Russia, which had been locked in competition with Britain in the so-called Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British Empire, British and Russian Empire, Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Emirate of Afghanistan, Afghanistan, Qajar Iran, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonia ...

for most of the century. Gorchakov said, "I consider the Berlin Treaty the darkest page in my life". Many Russians were furious over the European repudiation of their political gains, and though there was some thought that it represented only a minor stumble on the road to Russian hegemony in the Balkans, it actually gave Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia over to Austria-Hungary's sphere of influence and essentially removed all Russian influence from the area.

The Serbs were upset with "Russia... consenting to the cession of Bosnia to Austria":

Italy was dissatisfied with the results of the Congress, and the tensions between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were left unresolved. Bosnia-Herzegovina would also prove to be problematic for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in later decades. The League of the Three Emperors, established in 1873, was destroyed since Russia saw lack of German support on the issue of Bulgaria's full independence as a breach of loyalty and the alliance. The border between Greece and Turkey was not resolved. In 1881, after protracted negotiations, a compromise border was accepted after a naval demonstration of the great powers had resulted in the cession of Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

and the Arta Prefecture to Greece.

Two states that didn't participate in the war, Great Britain and Austria-Hungary, achieved great benefits from this Congress. The former was granted administrative control of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

in exchange for guarantees that Britain would use the island as a base to protect the Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression. The latter obtained the administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina and secured the control of a corridor leading to the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. Both of these territories had to remain de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

part of the Ottoman Empire, but in 1914 the British Empire formally annexed Cyprus, whereas Bosnia-Herzegovina was annexed by Austria in 1908.

Thus, the Berlin Congress sowed the seeds of further conflicts, including the Balkan Wars and (ultimately) the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In the 'Salisbury Circular' of 1 April 1878, the British Foreign Secretary, the Marquess of Salisbury, clarified the objections of him and the government to the Treaty of San Stefano because of the favorable position in which it left Russia.

In 1954, the British historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote:

Though the Congress of Berlin constituted a harsh blow to Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South ...

, it, by no means, solved the question of the area. The Slavs in the Balkans were still mostly under non-Slavic rule, split between the rule of Austria-Hungary and the ailing Ottoman Empire. The Slavic states of the Balkans had learned that banding together as Slavs benefited them less than playing to the desires of a neighboring great power. That damaged the unity of the Balkan Slavs and encouraged competition between the fledgling Slav states.

The underlying tensions of the region would continue to simmer for thirty years until they again exploded in the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

of 1912–1913. In 1914, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian heir, led to the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In hindsight, the stated goal of maintaining peace and balance of powers in the Balkans obviously failed since the region would remain a source of conflict between the great powers well into the 20th century.

Lithograph by Nikolai Pavlovich File:Greek-Delegation-Berlin-Congress.jpg, Greek Delegation in the Berlin Congress

Internal opposition to Andrássy's objectives

Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy and the occupation and administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina also obtained the right to station garrisons in theSanjak of Novi Pazar

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Novopazarski sandžak, Новопазарски санџак; ) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and 1902. The Ottoman rule ...

, which remained under Ottoman administration. The Sanjak preserved the separation of Serbia and Montenegro, and the Austro-Hungarian garrisons there would open the way for a dash to Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

that "would bring the western half of the Balkans under permanent Austrian influence". "High ustro-Hungarianmilitary authorities desired... nimmediate major expedition with Salonika as its objective".

On 28 September 1878 the Finance Minister, Koloman von Zell, threatened to resign if the army, behind which stood the Archduke Albert, were allowed to advance to Salonika. In the session of the Hungarian Parliament of 5 November 1878 the Opposition proposed that the Foreign Minister should be impeached for violating the constitution by his policy during the Near East Crisis and by the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The motion was lost by 179 to 95. By the Opposition rank and file the gravest accusations were raised against Andrassy.

Delegates

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

* Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

Earl of Beaconsfield (Prime Minister)

* Marquess of Salisbury (Foreign Secretary)

* Baron Ampthill (Ambassador to Germany)

* Richard B.P. Lyons (Ambassador to France)

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

* Prince Gorchakov (Foreign Minister)

* Count Shuvalov (Ambassador to Great Britain)

* Baron d'Oubril (Ambassador to Germany)

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

* Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

(Chancellor)

* Prince Hohenlohe (Ambassador to France)

* Bernhard Ernst von Bülow (State Secretary for Foreign Affairs)

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

* Count Andrássy (Foreign Minister)

* Count Károlyi (Ambassador to Germany)

* Baron Heinrich Karl von Haymerle

Baron Heinrich Karl von Haymerle (7 December 1828 – 10 October 1881) was an Austrian statesman born and educated in Vienna. He took part in the students' uprising in the revolution of 1848 and narrowly escaped execution. He served in the dipl ...

(Ambassador to Italy)

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

* Monsieur Waddington (Foreign Minister)

* Comte de Saint-Vallier

* Monsieur Desprey

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

* Count Corti (Foreign Minister)

* Count De Launay

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

* Karatheodori Pasha

* Sadullah Pasha

* Mehmed Ali Pasha

* Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian (representing Armenian population)

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

* Ion C. Brătianu

* Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian Liberalism, liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on Octo ...

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

* Theodoros Deligiannis

Theodoros Diligiannis (also transliterated as Deligiannis;Konstantinos Apostolou Vakalopoulos, ''Modern History of Macedonia (1830-1912)'', Barbounakis, 1988, p. 95. ; 1826–1905) was a Greek politician, minister and member of the Greek Parlia ...

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

* Jovan Ristić

Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

* Božo Petrović

* Stanko Radonjić

Albanians in the Congress

* Abdyl Frasheri

* Jani Vreto

See also

*International relations (1814–1919)

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end o ...

* Berlin Conference (1884)

* Armenian delegation at the Berlin Congress

Notes

References and further reading

* * Djordjevic, Dimitrije. "The Berlin Congress of 1878 and the Origins of World War I". ''Serbian Studies'' (1998) 12 #1 pp 1–10. * * * * Medlicott, William Norton. ''Congress of Berlin and After'' (1963) * * Millman, Richard. ''Britain and the Eastern Question, 1875–78'' (1979) * * Seton-Watson, R.W. ''Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern question: a study in diplomacy and party politics'' (1935) pp 431–89online

* * *

External links

* * Full text of the Treaty of Berlin inThe History of the Eastern Question

'. {{DEFAULTSORT:Congress of Berlin 1878 conferences 1878 in Germany 1878 in international relations 19th century in Berlin 19th-century diplomatic conferences Diplomatic conferences in Germany History of the Balkans July 1878 June 1878 Late modern Europe Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury