Ben Jonson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Benjamin Jonson ( 11 June 1572 – ) was an English playwright, poet and actor. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence on English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the

"Ben Jonson"

''

the original

on 12 July 2024. Jonson was a classically educated, well-read and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual). His cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the

Jonson was born in June 1572—possibly on the 11th—in or near London. In midlife, Jonson said his paternal grandfather, who "served King Henry and was a gentleman", was a member of the extended Johnston family of Annandale in

Jonson was born in June 1572—possibly on the 11th—in or near London. In midlife, Jonson said his paternal grandfather, who "served King Henry and was a gentleman", was a member of the extended Johnston family of Annandale in

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career, writing masques for James's court. '' The Satyr'' (1603) and '' The Masque of Blackness'' (1605) are two of about two dozen masques which Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne, some of them performed at Apethorpe Palace when the King was in residence. ''The Masque of Blackness'' was praised by Algernon Charles Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing and spectacle. In July 1607, Jonson performed a poem at the great banquet given for the King by the Merchant Taylors' Company, for which he earned a fee of £20.

On many of these projects, he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career, writing masques for James's court. '' The Satyr'' (1603) and '' The Masque of Blackness'' (1605) are two of about two dozen masques which Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne, some of them performed at Apethorpe Palace when the King was in residence. ''The Masque of Blackness'' was praised by Algernon Charles Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing and spectacle. In July 1607, Jonson performed a poem at the great banquet given for the King by the Merchant Taylors' Company, for which he earned a fee of £20.

On many of these projects, he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer

There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with

There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with

The Cambridge edition of the works of Ben Jonson

* Digitised Facsimiles of Jonson's second folio, 1640/

Jonson's second folio, 1640/1

* Video interview with scholar David Bevingto

The Collected Works of Ben Jonson

Audio resources on Ben Jonson at TheEnglishCollection.com

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Jonson, Ben 1572 births 1637 deaths 16th-century English dramatists and playwrights 16th-century English male writers 16th-century English poets 17th-century English dramatists and playwrights 17th-century English poets 17th-century English male writers Anglo-Scots British poets laureate Burials at Westminster Abbey Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism English duellists English literary critics English male actors English male dramatists and playwrights English male poets English people convicted of manslaughter English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) English prisoners and detainees English Renaissance dramatists Linguists of English People associated with Shakespeare People educated at Westminster School, London Writers from Westminster English satirists English satirical poets

satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual arts, visual, literature, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently Nonfiction, non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ...

plays '' Every Man in His Humour'' (1598), '' Volpone, or The Fox'' (), '' The Alchemist'' (1610) and '' Bartholomew Fair'' (1614) and for his lyric and epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word derives from the Greek (, "inscription", from [], "to write on, to inscribe"). This literary device has been practiced for over two millennia ...

matic poetry. He is regarded as "the second most important English dramatist, after [ illiam Shakespeare, during the reign of James I."The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (12 June 2024)"Ben Jonson"

''

Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article (publishing), articles or entries that are arranged Alp ...

''. Archived frothe original

on 12 July 2024. Jonson was a classically educated, well-read and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual). His cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the

Jacobean era

The Jacobean era was the period in English and Scotland, Scottish history that coincides

with the reign of James VI and I, James VI of Scotland who also inherited the crown of England in 1603 as James I. The Jacobean era succeeds the Elizabeth ...

(1603–1625) and of the Caroline era

The Caroline era is the period in English and Scottish history named for the 24-year reign of Charles I of England, Charles I (1625–1649). The term is derived from ''Carolus'', Latin for Charles. The Caroline era followed the Jacobean era, the ...

(1625–1642)."Ben Jonson", ''Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge'', volume 10, p. 388.

Early life

Jonson was born in June 1572—possibly on the 11th—in or near London. In midlife, Jonson said his paternal grandfather, who "served King Henry and was a gentleman", was a member of the extended Johnston family of Annandale in

Jonson was born in June 1572—possibly on the 11th—in or near London. In midlife, Jonson said his paternal grandfather, who "served King Henry and was a gentleman", was a member of the extended Johnston family of Annandale in Dumfries and Galloway

Dumfries and Galloway (; ) is one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland, located in the western part of the Southern Uplands. It is bordered by East Ayrshire, South Ayrshire, and South Lanarkshire to the north; Scottish Borders to the no ...

, a genealogy that is attested by the three spindles (rhombi

In plane Euclidean geometry, a rhombus (: rhombi or rhombuses) is a quadrilateral whose four sides all have the same length. Another name is equilateral quadrilateral, since equilateral means that all of its sides are equal in length. The rhom ...

) in the Jonson family coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

: one spindle is a diamond-shaped heraldic device used by the Johnston family. His ancestors spelt the family name with a letter "t" (Johnstone or Johnstoun). While the spelling had eventually changed to the more common "Johnson", the playwright's own particular preference became "Jonson".

Jonson's father lost his property, was imprisoned, and, as a Protestant, suffered forfeiture under Queen Mary. Becoming a clergyman upon his release, he died a month before his son's birth. His widow married a master bricklayer

A bricklayer, which is related to but different from a mason, is a craftsperson and tradesperson who lays bricks to construct brickwork. The terms also refer to personnel who use blocks to construct blockwork walls and other forms of maso ...

two years later.Robert Chambers, Book of Days"Ben Jonson", ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 15th edition, p. 611. Jonson attended school in St Martin's Lane in London. Later, a family friend paid for his studies at Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

, where the antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

, historian, topographer and officer of arms William Camden was one of his masters. The pupil and master became friends, and the intellectual influence of Camden's broad-ranging scholarship upon Jonson's art and literary style remained notable, until Camden's death in 1623. At Westminster School he met the Welsh poet Hugh Holland, with whom he established an "enduring relationship". Both of them would write preliminary poems for illiam Shakespeare's First Folio">illiam Shakespeare's First Folio (1623).

On leaving Westminster School in 1589, Jonson attended St John's College, Cambridge, to continue his book learning. However, because of his unwilled apprenticeship to his bricklayer stepfather, he returned after a month. According to the churchman and historian Thomas Fuller, Jonson at this time built a garden wall in Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

. After having been an apprentice bricklayer, Jonson went to the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and volunteered to soldier with the English regiments of Sir Francis Vere in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

. England was allied with the Dutch in their fight for independence as well as the ongoing war with Spain.

The ''Hawthornden Manuscripts'' (1619), of the conversations between Ben Jonson and the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden, report that, when in Flanders, Jonson engaged, fought and killed an enemy soldier in single combat, and took for trophies the weapons of the vanquished soldier.

Jonson is reputed to have visited the antiquary Sir Robert Cotton at a residence of his in Chester

Chester is a cathedral city in Cheshire, England, on the River Dee, Wales, River Dee, close to the England–Wales border. With a built-up area population of 92,760 in 2021, it is the most populous settlement in the borough of Cheshire West an ...

early in the 17th century.

After his military activity on the Continent, Jonson returned to England and worked as an actor and as a playwright. As an actor, he was the protagonist "Hieronimo" (Geronimo) in the play ''The Spanish Tragedy

''The Spanish Tragedy'', or ''Hieronimo is Mad Again'' is an Elizabethan tragedy written by Thomas Kyd between 1582 and 1592. Highly popular and influential in its time, ''The Spanish Tragedy'' established a new genre in English theatre: the re ...

'' (), by Thomas Kyd, the first revenge tragedy in English literature. By 1597, he was a working playwright employed by Philip Henslowe, the leading producer for the English public theatre; by the next year, the production of '' Every Man in His Humour'' (1598) had established Jonson's reputation as a dramatist.

Jonson described his wife to William Drummond as "a shrew, yet honest". The identity of Jonson's wife is obscure, though she sometimes is identified as "Ann Lewis", the woman who married a Benjamin Jonson in 1594, at the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr, near London Bridge."Ben Jonson", ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 15th edition, p. 612.

The registers of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

record that Mary Jonson, their eldest daughter, died in November 1593, at six months of age. A decade later, in 1603, Benjamin Jonson, their eldest son, died of bubonic plague when he was seven years old, upon which Jonson wrote the elegiac " On My First Sonne" (1603). A second son, also named Benjamin Jonson, died in 1635.

During that period, Jonson and his wife lived separate lives for five years; Jonson enjoying the residential hospitality of his patrons, Esme Stuart, 3rd Duke of Lennox and 7th Seigneur d'Aubigny and Sir Robert Townshend.

Career

By summer 1597, Jonson had a fixed engagement in the Admiral's Men, then performing under Philip Henslowe's management at The Rose.John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He was a pioneer archaeologist, who recorded (often for the first time) numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England ...

reports, on uncertain authority, that Jonson was not successful as an actor; whatever his skills as an actor, he was more valuable to the company as a writer.

By this time Jonson had begun to write original plays for the Admiral's Men; in 1598 he was mentioned by Francis Meres in his ''Palladis Tamia'' as one of "the best for tragedy." None of his early tragedies survive, however. An undated comedy, '' The Case is Altered'', may be his earliest surviving play.

In 1597, a play which he co-wrote with Thomas Nashe, '' The Isle of Dogs'', was suppressed after causing great offence. Arrest warrants for Jonson and Nashe were issued by Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

's so-called interrogator, Richard Topcliffe. Jonson was jailed in Marshalsea Prison and charged with "Leude and mutynous behaviour", while Nashe managed to escape to Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

. Two of the actors, Gabriel Spenser and Robert Shaw, were also imprisoned. A year later, Jonson was again briefly imprisoned, this time in Newgate Prison, for killing Spenser in a duel on 22 September 1598 in Hogsden Fields (today part of Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. It was Historic counties of England, historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. Hoxton lies north-east of the City of London, is considered to be a part of London's East End ...

). Tried on a charge of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

, Jonson pleaded guilty but was released by benefit of clergy, a legal ploy through which he gained leniency by reciting a brief Bible verse (the neck-verse), forfeiting his "goods and chattels" and being branded with the so-called Tyburn T on his left thumb.

While in jail Jonson converted to Catholicism, possibly through the influence of fellow-prisoner Father Thomas Wright, a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest.

In 1598 Jonson produced his first great success, '' Every Man in His Humour'', capitalising on the vogue for humorous plays which George Chapman

George Chapman ( – 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman is seen as an anticipator of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. He is ...

had begun with '' An Humorous Day's Mirth''. [ illiam Shakespeare was among the first actors to be cast. Jonson followed this in 1599 with '' Every Man out of His Humour'', a pedantic attempt to imitate Aristophanes. It is not known whether this was a success on stage, but when published it proved popular and went through several editions.

Jonson's other work for the theatre in the last years of Elizabeth I's reign was marked by fighting and controversy. '' Cynthia's Revels'' was produced by the Children of the Chapel Royal at Blackfriars Theatre in 1600. It satirised both John Marston, who Jonson believed had accused him of lustfulness in '' Histriomastix'', and Thomas Dekker. Jonson attacked the two poets again in ''Poetaster

Poetaster (), like rhymester or versifier, is a derogatory term applied to bad or inferior poets. Specifically, ''poetaster'' has implications of unwarranted pretensions to artistic value. The word was coined in Latin by Erasmus in 1521. It was f ...

'' (1601). Dekker responded with '' Satiromastix'', subtitled "the untrussing of the humorous poet". The final scene of this play, while certainly not to be taken at face value as a portrait of Jonson, offers a caricature that is recognisable from Drummond's report – boasting about himself and condemning other poets, criticising performances of his plays and calling attention to himself in any available way.

This " War of the Theatres" appears to have ended with reconciliation on all sides. Jonson collaborated with Dekker on a pageant welcoming James I to England in 1603 although Drummond reports that Jonson called Dekker a rogue. Marston dedicated '' The Malcontent'' to Jonson and the two collaborated with Chapman on '' Eastward Ho!'', a 1605 play whose anti-Scottish sentiment briefly landed both Jonson and Chapman in jail.

Royal patronage

At the beginning of the English reign ofJames VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 M ...

in 1603 Jonson joined other poets and playwrights in welcoming the new king. Jonson quickly adapted himself to the additional demand for masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

s and entertainments introduced with the new reign and fostered by both the king and his consort Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

. In addition to his popularity on the public stage and in the royal hall, he enjoyed the patronage of aristocrats such as Elizabeth Sidney (daughter of Sir Philip Sidney) and Lady Mary Wroth. This connection with the Sidney family provided the impetus for one of Jonson's most famous lyrics, the country house poem ''To Penshurst

Penshurst is a historic village and civil parishes in England, civil parish located in a valley upon the northern slopes of the Weald, Kentish Weald, at the confluence of the River Medway and the River Eden, Kent, River Eden, within the Seveno ...

''.

In February 1603 John Manningham reported that Jonson was living on Robert Townsend, son of Sir Roger Townshend, and "scorns the world." Perhaps this explains why his trouble with English authorities continued. That same year he was questioned by the Privy Council about ''Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Sejanus ( – 18 October AD 31), commonly known as Sejanus (), was a Roman soldier and confidant of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. Of the Equites class by birth, Sejanus rose to power as prefect of the Praetorian Guard, the imperia ...

'', a politically themed play about corruption in the Roman Empire. He was again in trouble for topical allusions in a play, now lost, in which he took part. Shortly after his release from a brief spell of imprisonment imposed to mark the authorities' displeasure at the work, in the second week of October 1605, he was present at a supper party attended by most of the Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

conspirators. After the plot's discovery, he appears to have avoided further imprisonment; he volunteered what he knew of the affair to the investigator Robert Cecil and the Privy Council. Father Thomas Wright, who heard Fawkes's confession, was known to Jonson from prison in 1598 and Cecil may have directed him to bring the priest before the council, as a witness.

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career, writing masques for James's court. '' The Satyr'' (1603) and '' The Masque of Blackness'' (1605) are two of about two dozen masques which Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne, some of them performed at Apethorpe Palace when the King was in residence. ''The Masque of Blackness'' was praised by Algernon Charles Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing and spectacle. In July 1607, Jonson performed a poem at the great banquet given for the King by the Merchant Taylors' Company, for which he earned a fee of £20.

On many of these projects, he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career, writing masques for James's court. '' The Satyr'' (1603) and '' The Masque of Blackness'' (1605) are two of about two dozen masques which Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne, some of them performed at Apethorpe Palace when the King was in residence. ''The Masque of Blackness'' was praised by Algernon Charles Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing and spectacle. In July 1607, Jonson performed a poem at the great banquet given for the King by the Merchant Taylors' Company, for which he earned a fee of £20.

On many of these projects, he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

. For example, Jones designed the scenery for Jonson's masque '' Oberon, the Faery Prince'' performed at Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

on 1 January 1611 in which Prince Henry, eldest son of James I, appeared in the title role. Perhaps partly as a result of this new career, Jonson gave up writing plays for the public theatres for a decade. He later told Drummond that he had made less than two hundred pounds on all his plays together.

In 1616 Jonson received a yearly pension of 100 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

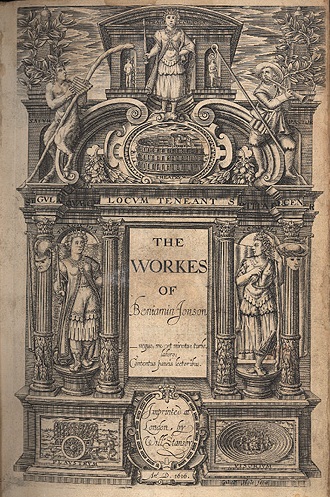

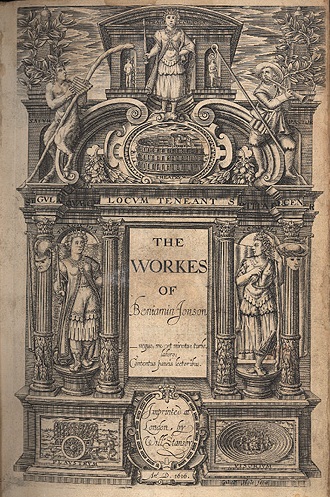

(about £60), leading some to identify him as England's first Poet Laureate. This sign of royal favour may have encouraged him to publish the first volume of the folio-collected edition of his works that year. Other volumes followed in 1640–41 and 1692. (See: Ben Jonson folios)

On 8 July 1618 Jonson set out from Bishopsgate in London to walk to Edinburgh, arriving in Scotland's capital on 17 September. For the most part he followed the Great North Road, and was treated to lavish and enthusiastic welcomes in both towns and country houses. On his arrival he lodged initially with John Stuart, a cousin of King James, in Leith, and was made an honorary burgess of Edinburgh at a dinner laid on by the city on 26 September. He stayed in Scotland until late January 1619, and the best-remembered hospitality he enjoyed was that of the Scottish poet, William Drummond of Hawthornden, sited on the River Esk. Drummond undertook to record as much of Jonson's conversation as he could in his diary, and thus recorded aspects of Jonson's personality that would otherwise have been less clearly seen. Jonson delivers his opinions, in Drummond's terse reporting, in an expansive and even magisterial mood. Drummond noted he was "a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemner and scorner of others".

On returning to England, he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

degree from Oxford University.

The period between 1605 and 1620 may be viewed as Jonson's heyday. By 1616 he had produced all the plays on which his present reputation as a dramatist is based, including the tragedy '' Catiline'' (acted and printed 1611), which achieved limited success and the comedies '' Volpone'' (acted 1605 and printed in 1607), '' Epicoene, or the Silent Woman'' (1609), '' The Alchemist'' (1610), '' Bartholomew Fair'' (1614) and '' The Devil Is an Ass'' (1616). ''The Alchemist'' and ''Volpone'' were immediately successful. Of ''Epicoene'', Jonson told Drummond of a satirical verse which reported that the play's subtitle was appropriate since its audience had refused to applaud the play (i.e., remained silent). Yet ''Epicoene'', along with ''Bartholomew Fair'' and (to a lesser extent) ''The Devil is an Ass'' have in modern times achieved a certain degree of recognition. While his life during this period was apparently more settled than it had been in the 1590s, his financial security was still not assured.

Religion

Jonson recounted that his father had been a prosperousProtestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

landowner until the reign of " Bloody Mary" and had suffered imprisonment and the forfeiture of his wealth during that monarch's attempt to restore England to Catholicism. On Elizabeth's accession, he had been freed and had been able to travel to London to become a clergyman. (All that is known of Jonson's father, who died a month before his son was born, comes from the poet's own narrative.) Jonson's elementary education was in a small church school attached to St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

parish, and at the age of about seven he secured a place at Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

, then part of Westminster Abbey.

Notwithstanding this emphatically Protestant grounding, Jonson maintained an interest in Catholic doctrine throughout his adult life and, at a particularly perilous time while a religious war with Spain was widely expected and persecution of Catholics was intensifying, he converted to the faith.Riggs (1989: 51–52). This took place in October 1598, while Jonson was on remand in Newgate Gaol charged with manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

. Jonson's biographer Ian Donaldson is among those who suggest that the conversion was instigated by Father Thomas Wright, a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest who had resigned from the order over his acceptance of Queen Elizabeth's right to rule in England.Donaldson (2011: 134–140). Wright, although placed under house arrest

House arrest (also called home confinement, or nowadays electronic monitoring) is a legal measure where a person is required to remain at their residence under supervision, typically as an alternative to imprisonment. The person is confined b ...

on the orders of Lord Burghley, was permitted to minister to the inmates of London prisons. It may have been that Jonson, fearing that his trial would go against him, was seeking the unequivocal absolution

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Priest#Christianity, Christian priests and experienced by Penance#Christianity, Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, alth ...

that Catholicism could offer if he were sentenced to death. Alternatively, he could have been looking to personal advantage from accepting conversion since Father Wright's protector, the Earl of Essex, was among those who might hope to rise to influence after the succession of a new monarch. Jonson's conversion came at a weighty time in affairs of state; the royal succession, from the childless Elizabeth, had not been settled and Essex's Catholic allies were hopeful that a sympathetic ruler might attain the throne.

Conviction, and certainly not expedience alone, sustained Jonson's faith during the troublesome twelve years he remained a Catholic. His stance received attention beyond the low-level intolerance to which most followers of that faith were exposed. The first draft of his play '' Sejanus His Fall'' was banned for " popery", and did not re-appear until some offending passages were cut. In January 1606 he (with Anne, his wife) appeared before the Consistory Court in London to answer a charge of recusancy, with Jonson alone additionally accused of allowing his fame as a Catholic to "seduce" citizens to the cause. This was a serious matter (the Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

was still fresh in people's minds) but he explained that his failure to take communion was only because he had not found sound theological endorsement for the practice, and by paying a fine of thirteen shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s (156 pence) he escaped the more serious penalties at the authorities' disposal. His habit was to slip outside during the sacrament, a common routine at the time—indeed it was one followed by the royal consort, Queen Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

, herself—to show political loyalty while not offending the conscience. Leading church figures, including John Overall, Dean of St Paul's, were tasked with winning Jonson back to Protestantism, but these overtures were resisted.Donaldson (2011: 228–9).

In May 1610 Henry IV of France was assassinated, purportedly in the name of the Pope; he had been a Catholic monarch respected in England for tolerance towards Protestants, and his murder seems to have been the immediate cause of Jonson's decision to rejoin the Church of England.Donaldson (2011: 272). He did this in flamboyant style, pointedly drinking a full chalice of communion wine at the eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

to demonstrate his renunciation of the Catholic rite, in which the priest alone drinks the wine.Riggs (1989: 177). The exact date of the ceremony is unknown. However, his interest in Catholic belief and practice remained with him until his death.

Decline and death

Jonson's productivity began to decline in the 1620s, but he remained well-known. In that time, the Sons of Ben or the "Tribe of Ben", those younger poets such as Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, and Sir John Suckling who took their bearing in verse from Jonson, rose to prominence. However, a series of setbacks drained his strength and damaged his reputation. He resumed writing regular plays in the 1620s, but these are not considered among his best. They are of significant interest, however, for their portrayal of Charles I's England. ''The Staple of News

''The Staple of News'' is an early Literature in English#Caroline and Cromwellian literature, Caroline era play, a satire by Ben Jonson. The play was first performed in late 1625 by the King's Men (playing company), King's Men at the Blackfriars ...

'', for example, offers a remarkable look at the earliest stage of English journalism. The lukewarm reception given that play was, however, nothing compared to the dismal failure of '' The New Inn''; the cold reception given this play prompted Jonson to write a poem condemning his audience (''An Ode to Himself''), which in turn prompted Thomas Carew, one of the "Tribe of Ben", to respond in a poem that asks Jonson to recognise his own decline.

The principal factor in Jonson's partial eclipse was, however, the death of James and the accession of King Charles I in 1625. Jonson felt neglected by the new court. A decisive quarrel with Jones harmed his career as a writer of court masques, although he continued to entertain the court on an irregular basis. For his part, Charles displayed a certain degree of care for the great poet of his father's day: he increased Jonson's annual pension to £100 and included a tierce of wine and beer.

Despite the strokes that he suffered in the 1620s, Jonson continued to write. At his death in 1637 he seems to have been working on another play, '' The Sad Shepherd''. Though only two acts are extant, this represents a remarkable new direction for Jonson: a move into pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

drama. During the early 1630s, he also conducted a correspondence with James Howell, who warned him about disfavour at court in the wake of his dispute with Jones.

According to a contemporary letter written by Edward Thelwall of Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wale ...

, Jonson died on 18 August 1637 (O.S. 6 August). He died in London. His funeral was held the next day. It was attended by "all or the greatest part of the nobility then in town". He is buried in the north aisle of the nave in Westminster Abbey, with the inscription "O Rare Ben Johnson 'sic'' set in the slab over his grave. John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He was a pioneer archaeologist, who recorded (often for the first time) numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England ...

, in a more meticulous record than usual, notes that a passer-by, John Young of Great Milton, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, saw the bare grave marker and on impulse paid a workman eighteen pence to make the inscription. Another theory suggests that the tribute came from William Davenant, Jonson's successor as Poet Laureate (and card-playing companion of Young), as the same phrase appears on Davenant's nearby gravestone, but essayist Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

contends that Davenant's wording represented no more than Young's coinage, cheaply re-used. The fact that Jonson was buried in an upright position was an indication of his reduced circumstances at the time of his death, although it has also been written that he asked for a grave exactly 18 inches square from the monarch and received an upright grave to fit in the requested space.

It has been pointed out that the inscription could be read "Orare Ben Jonson" (pray for Ben Jonson), possibly in an allusion to Jonson's acceptance of Catholic doctrine during his lifetime (although he had returned to the Church of England); the carving shows a distinct space between "O" and "rare".

A monument to Jonson was erected in about 1723 by the Earl of Oxford and is in the eastern aisle of Westminster Abbey's Poets' Corner. It includes a portrait medallion and the same inscription as on the gravestone. It seems Jonson was to have had a monument erected by subscription soon after his death but the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

intervened.

His work

Drama

Apart from two tragedies, ''Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Sejanus ( – 18 October AD 31), commonly known as Sejanus (), was a Roman soldier and confidant of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. Of the Equites class by birth, Sejanus rose to power as prefect of the Praetorian Guard, the imperia ...

'' and '' Catiline'', that largely failed to impress Renaissance audiences, Jonson's work for the public theatres was in comedy. These plays vary in some respects. The minor early plays, particularly those written for boy player

A boy player was a male child or teenager who performed in Medieval theatre, Medieval and English Renaissance theatre, English Renaissance playing companies. Some boy players worked for adult companies and performed the female roles, since women ...

s, present somewhat looser plots and less-developed characters than those written later, for adult companies. Already in the plays which were his salvos in the Poets' War, he displays the keen eye for absurdity and hypocrisy that marks his best-known plays; in these early efforts, however, the plot mostly takes second place to a variety of incident and comic set-pieces. They are, also, notably ill-tempered. Thomas Davies called ''Poetaster'' "a contemptible mixture of the serio-comic, where the names of Augustus Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

, Maecenas

Gaius Cilnius Maecenas ( 13 April 68 BC – 8 BC) was a friend and political advisor to Octavian (who later reigned as emperor Augustus). He was also an important patron for the new generation of Augustan poets, including both Horace and Virgil. ...

, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

, Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

and Tibullus, are all sacrificed upon the altar of private resentment". Another early comedy in a different vein, '' The Case is Altered'', is markedly similar to Shakespeare's romantic comedies in its foreign setting, emphasis on genial wit and love-plot. Henslowe's diary indicates that Jonson had a hand in numerous other plays, including many in genres such as English history with which he is not otherwise associated.

The comedies of his middle career, from '' Eastward Hoe'' to '' The Devil Is an Ass'' are for the most part city comedy, with a London setting, themes of trickery and money, and a distinct moral ambiguity, despite Jonson's professed aim in the Prologue to '' Volpone'' to "mix profit with your pleasure". His late plays or " dotages", particularly '' The Magnetic Lady'' and '' The Sad Shepherd'', exhibit signs of an accommodation with the romantic tendencies of Elizabethan comedy.

Within this general progression, however, Jonson's comic style remained constant and easily recognisable. He announces his programme in the prologue to the folio

The term "folio" () has three interconnected but distinct meanings in the world of books and printing: first, it is a term for a common method of arranging Paper size, sheets of paper into book form, folding the sheet only once, and a term for ...

version of '' Every Man in His Humour'': he promises to represent "deeds, and language, such as men do use". He planned to write comedies that revived the classical premises of Elizabethan dramatic theory—or rather, since all but the loosest English comedies could claim some descent from Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus ( ; 254 – 184 BC) was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by Livius Andro ...

and Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a playwright during the Roman Republic. He was the author of six Roman comedy, comedies based on Greek comedy, Greek originals by Menander or Apollodorus of Carystus. A ...

, he intended to apply those premises with rigour. This commitment entailed negations: after ''The Case is Altered'', Jonson eschewed distant locations, noble characters, romantic plots and other staples of Elizabethan comedy, focusing instead on the satiric and realistic inheritance of new comedy. He set his plays in contemporary settings, peopled them with recognisable types, and set them to actions that, if not strictly realistic, involved everyday motives such as greed and jealousy. In accordance with the temper of his age, he was often so broad in his characterisation that many of his most famous scenes border on the farcical (as William Congreve, for example, judged ''Epicoene''). He was more diligent in adhering to the classical unities than many of his peers—although as Margaret Cavendish noted, the unity of action in the major comedies was rather compromised by Jonson's abundance of incident. To this classical model, Jonson applied the two features of his style which save his classical imitations from mere pedantry: the vividness with which he depicted the lives of his characters and the intricacy of his plots. Coleridge, for instance, claimed that '' The Alchemist'' had one of the three most perfect plots in literature.

Poetry

Jonson's poetry, like his drama, is informed by his classical learning. Some of his better-known poems are close translations of Greek or Roman models; all display the careful attention to form and style that often came naturally to those trained in classics in thehumanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

manner. Jonson largely avoided the debates about rhyme and meter that had consumed Elizabethan classicists such as Thomas Campion

Thomas Campion (sometimes spelled Campian; 12 February 1567 – 1 March 1620) was an English composer, poet, and physician. He was born in London, educated at Cambridge, and studied law in Gray's Inn. He wrote over a hundred lute songs, masque ...

and Gabriel Harvey. Accepting both rhyme and stress, Jonson used them to mimic the classical qualities of simplicity, restraint and precision.

"Epigrams" (published in the 1616 folio) is an entry in a genre that was popular among late-Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences, although Jonson was perhaps the only poet of his time to work in its full classical range. The epigrams explore various attitudes, most from the satiric stock of the day: complaints against women, courtiers and spies abound. The condemnatory poems are short and anonymous; Jonson's epigrams of praise, including a famous poem to Camden and lines to Lucy Harington, are longer and are mostly addressed to specific individuals. Although it is included among the epigrams, " On My First Sonne" is neither satirical nor very short; the poem, intensely personal and deeply felt, typifies a genre that would come to be called "lyric poetry." It is possible that the spelling of 'son' as 'Sonne' is meant to allude to the sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

form, with which it shares some features. A few other so-called epigrams share this quality. Jonson's poems of "The Forest" also appeared in the first folio. Most of the fifteen poems are addressed to Jonson's aristocratic supporters, but the most famous are his country-house poem "To Penshurst" and the poem " To Celia" ("Come, my Celia, let us prove") that appears also in '' Volpone''.

''Underwood'', published in the expanded folio of 1640, is a larger and more heterogeneous group of poems. It contains '' A Celebration of Charis'', Jonson's most extended effort at love poetry; various religious pieces; encomiastic poems including the poem to Shakespeare and a sonnet on Mary Wroth; the ''Execration against Vulcan'' and others. The 1640 volume also contains three elegies which have often been ascribed to Donne (one of them appeared in Donne's posthumous collected poems).

Relationship with Shakespeare

There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with

There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

. William Drummond reports that during their conversation, Jonson scoffed at two apparent absurdities in Shakespeare's plays: a nonsensical line in ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

'' and the setting of '' The Winter's Tale'' on the non-existent seacoast of Bohemia. Drummond also reported Jonson as saying that Shakespeare "wanted art" (i.e., lacked skill).

In "De Shakespeare Nostrat" in ''Timber'', which was published posthumously and reflects his lifetime of practical experience, Jonson offers a fuller and more conciliatory comment. He recalls being told by certain actors that Shakespeare never blotted (i.e., crossed out) a line when he wrote. His own claimed response was "Would he had blotted a thousand!" However, Jonson explains, "Hee was (indeed) honest, and of an open, and free nature: had an excellent ''Phantsie''; brave notions and gentle expressions: wherein hee flow'd with that facility, that sometime it was necessary he should be stopp'd". Jonson concludes that "there was ever more in him to be praised than to be pardoned." When Shakespeare died, he said, "He was not of an age, but for all time."

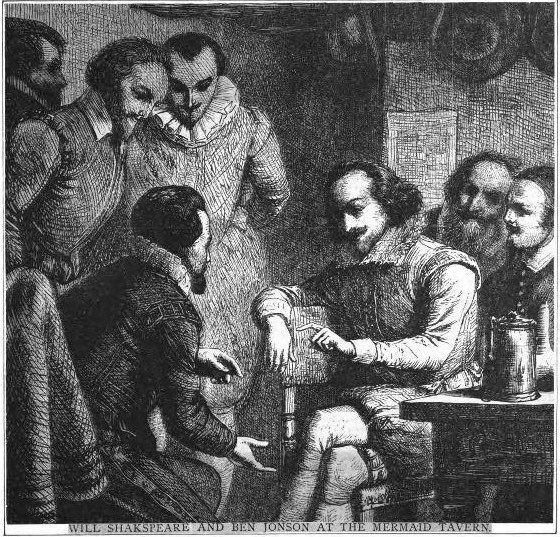

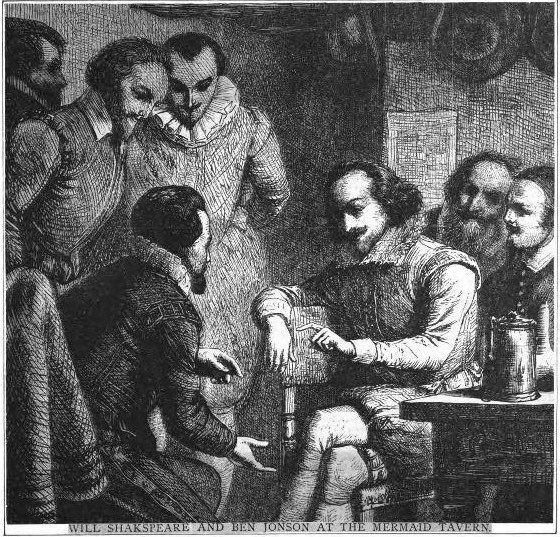

Thomas Fuller relates stories of Jonson and Shakespeare engaging in debates at the Mermaid Tavern; Fuller imagines conversations in which Shakespeare would run rings around the more learned but more ponderous Jonson. That the two men knew each other personally is beyond doubt, not only because of the tone of Jonson's references to him but because Shakespeare's company produced a number of Jonson's plays, at least two of which ('' Every Man in His Humour'' and '' Sejanus His Fall'') Shakespeare certainly acted in. However, it is now impossible to tell how much personal communication they had, and tales of their friendship cannot be substantiated.

Jonson's most influential and revealing commentary on Shakespeare is the second of the two poems that he contributed to the prefatory verse that opens Shakespeare's First Folio

''Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies'' is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is cons ...

. This poem, "To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us", did a good deal to create the traditional view of Shakespeare as a poet who, despite "small Latine, and lesse Greeke", had a natural genius. The poem has traditionally been thought to exemplify the contrast which Jonson perceived between himself, the disciplined and erudite classicist, scornful of ignorance and sceptical of the masses, and Shakespeare, represented in the poem as a kind of natural wonder whose genius was not subject to any rules except those of the audiences for which he wrote. But the poem itself qualifies this view:

Some view this elegy as a conventional exercise, but others see it as a heartfelt tribute to the "Sweet Swan of Avon", the "Soul of the Age!" It has been argued that Jonson helped to edit the First Folio, and he may have been inspired to write this poem by reading his fellow playwright's works, a number of which had been previously either unpublished or available in less satisfactory versions, in a relatively complete form.

Reception and influence

Jonson was a towering literary figure, and his influence was enormous for he has been described as "One of the most vigorous minds that ever added to the strength of English literature". Before the English Civil War, the "Tribe of Ben" touted his importance, and during the Restoration Jonson's satirical comedies and his theory and practice of "humour characters" (which are often misunderstood; see William Congreve's letters for clarification) was extremely influential, providing the blueprint for many Restoration comedies.John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He was a pioneer archaeologist, who recorded (often for the first time) numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England ...

wrote of Jonson in '' Brief Lives''. By 1700, Jonson's status began to decline. In the Romantic era, Jonson suffered the fate of being unfairly compared and contrasted to Shakespeare, as the taste for Jonson's type of satirical comedy decreased. Jonson was at times greatly appreciated by the Romantics, but overall he was denigrated for not writing in a Shakespearean vein.

In 2012, after more than two decades of research, Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

published the first new edition of Jonson's complete works for 60 years.

Drama

As G. E. Bentley notes in ''Shakespeare and Jonson: Their Reputations in the Seventeenth Century Compared'', Jonson's reputation was in some respects equal to Shakespeare's in the 17th century. After the English theatres were reopened on the Restoration of Charles II, Jonson's work, along with Shakespeare's and Fletcher's, formed the initial core of the Restoration repertory. It was not until after 1710 that Shakespeare's plays (ordinarily in heavily revised forms) were more frequently performed than those of his Renaissance contemporaries. Many critics since the 18th century have ranked Jonson below only Shakespeare among English Renaissance dramatists. Critical judgment has tended to emphasise the very qualities that Jonson himself lauds in his prefaces, in ''Timber'', and in his scattered prefaces and dedications: the realism and propriety of his language, the bite of his satire, and the care with which he plotted his comedies. For some critics, the temptation to contrast Jonson (representing art or craft) with Shakespeare (representing nature, or untutored genius) has seemed natural; Jonson himself may be said to have initiated this interpretation in the second folio, and Samuel Butler drew the same comparison in his commonplace book later in the century. At the Restoration, this sensed difference became a kind of critical dogma. Charles de Saint-Évremond placed Jonson's comedies above all else in English drama, and Charles Gildon called Jonson the father of English comedy.John Dryden

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration (En ...

offered a more common assessment in the "Essay of Dramatic Poesie," in which his Avatar

Avatar (, ; ) is a concept within Hinduism that in Sanskrit literally means . It signifies the material appearance or incarnation of a powerful deity, or spirit on Earth. The relative verb to "alight, to make one's appearance" is sometimes u ...

Neander compares Shakespeare to Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

and Jonson to Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

: the former represented profound creativity, the latter polished artifice. But "artifice" was in the 17th century almost synonymous with "art"; Jonson, for instance, used "artificer" as a synonym for "artist" (''Discoveries,'' 33). For Lewis Theobald, too, Jonson "ow dall his Excellence to his Art," in contrast to Shakespeare, the natural genius. Nicholas Rowe, to whom may be traced the legend that Jonson owed the production of ''Every Man in his Humour'' to Shakespeare's intercession, likewise attributed Jonson's excellence to learning, which did not raise him quite to the level of genius. A consensus formed: Jonson was the first English poet to understand classical precepts with any accuracy, and he was the first to apply those precepts successfully to contemporary life. But there were also more negative spins on Jonson's learned art; for instance, in the 1750s, Edward Young casually remarked on the way in which Jonson's learning worked, like Samson's strength, to his own detriment. Earlier, Aphra Behn, writing in defence of female playwrights, had pointed to Jonson as a writer whose learning did not make him popular; unsurprisingly, she compares him unfavourably to Shakespeare. Particularly in the tragedies, with their lengthy speeches abstracted from Sallust and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, Augustan critics saw a writer whose learning had swamped his aesthetic

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,'' , acces ...

judgment.

In this period, Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

is exceptional in that he noted the tendency to exaggeration in these competing critical portraits: "It is ever the nature of Parties to be in extremes; and nothing is so probable, as that because Ben Jonson had much the most learning, it was said on the one hand that Shakespear had none at all; and because Shakespear had much the most wit and fancy, it was retorted on the other, that Jonson wanted both." For the most part, the 18th century consensus remained committed to the division that Pope doubted; as late as the 1750s, Sarah Fielding could put a brief recapitulation of this analysis in the mouth of a "man of sense" encountered by David Simple.

Though his stature declined during the 18th century, Jonson was still read and commented on throughout the century, generally in the kind of comparative and dismissive terms just described. Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg translated parts of Peter Whalley's edition into German in 1765. Shortly before the Romantic revolution, Edward Capell offered an almost unqualified rejection of Jonson as a dramatic poet, who (he writes) "has very poor pretensions to the high place he holds among the English Bards, as there is no original manner to distinguish him and the tedious sameness visible in his plots indicates a defect of Genius." The disastrous failures of productions of ''Volpone'' and ''Epicoene'' in the early 1770s no doubt bolstered a widespread sense that Jonson had at last grown too antiquated for the contemporary public; if he still attracted enthusiasts such as Earl Camden and William Gifford, he all but disappeared from the stage in the last quarter of the century.

The romantic revolution in criticism brought about an overall decline in the critical estimation of Jonson. Hazlitt refers dismissively to Jonson's "laborious caution." Coleridge, while more respectful, describes Jonson as psychologically superficial: "He was a very accurately observing man; but he cared only to observe what was open to, and likely to impress, the senses." Coleridge placed Jonson second only to Shakespeare; other romantic critics were less approving. The early 19th century was the great age for recovering Renaissance drama. Jonson, whose reputation had survived, appears to have been less interesting to some readers than writers such as Thomas Middleton or John Heywood, who were in some senses "discoveries" of the 19th century. Moreover, the emphasis which the romantic writers placed on imagination, and their concomitant tendency to distrust studied art, lowered Jonson's status, if it also sharpened their awareness of the difference traditionally noted between Jonson and Shakespeare. This trend was by no means universal, however; William Gifford, Jonson's first editor of the 19th century, did a great deal to defend Jonson's reputation during this period of general decline. In the next era, Swinburne, who was more interested in Jonson than most Victorians, wrote, "The flowers of his growing have every quality but one which belongs to the rarest and finest among flowers: they have colour, form, variety, fertility, vigour: the one thing they want is fragrance" – by "fragrance," Swinburne means spontaneity.

In the 20th century, Jonson's body of work has been subject to a more varied set of analyses, broadly consistent with the interests and programmes of modern literary criticism. In an essay printed in ''The Sacred Wood'', T. S. Eliot attempted to repudiate the charge that Jonson was an arid classicist by analysing the role of imagination in his dialogue. Eliot was appreciative of Jonson's overall conception and his "surface", a view consonant with the modernist reaction against Romantic criticism, which tended to denigrate playwrights who did not concentrate on representations of psychological depth. Around mid-century, a number of critics and scholars followed Eliot's lead, producing detailed studies of Jonson's verbal style. At the same time, study of Elizabethan themes and conventions, such as those by E. E. Stoll and M. C. Bradbrook, provided a more vivid sense of how Jonson's work was shaped by the expectations of his time.

The proliferation of new critical perspectives after mid-century touched on Jonson inconsistently. Jonas Barish was the leading figure among critics who appreciated Jonson's artistry. On the other hand, Jonson received less attention from the new critics than did some other playwrights and his work was not of programmatic interest to psychoanalytic critics. But Jonson's career eventually made him a focal point for the revived sociopolitical criticism. Jonson's works, particularly his masques and pageants, offer significant information regarding the relations of literary production and political power, as do his contacts with and poems for aristocratic patrons; moreover, his career at the centre of London's emerging literary world has been seen as exemplifying the development of a fully commodified literary culture. In this respect he is seen as a transitional figure, an author whose skills and ambition led him to a leading role both in the declining culture of patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

and in the rising culture of mass media.

Poetry

Jonson has been called "the first poet laureate". If Jonson's reputation as a playwright has traditionally been linked to Shakespeare, his reputation as a poet has, since the early 20th century, been linked to that ofJohn Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

. In this comparison, Jonson represents the cavalier

The term ''Cavalier'' () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of Charles I of England and his son Charles II of England, Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum (England), Int ...

strain of poetry, emphasising grace and clarity of expression; Donne, by contrast, epitomised the metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

school of poetry, with its reliance on strained, baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

metaphors and often vague phrasing. Since the critics who made this comparison ( Herbert Grierson for example), were to varying extents rediscovering Donne, this comparison often worked to the detriment of Jonson's reputation.

In his time Jonson was at least as influential as Donne. In 1623, historian Edmund Bolton named him the best and most polished English poet. That this judgment was widely shared is indicated by the admitted influence he had on younger poets. The grounds for describing Jonson as the "father" of cavalier poets are clear: many of the cavalier poets described themselves as his "sons" or his "tribe". For some of this tribe, the connection was as much social as poetic; Herrick described meetings at "the Sun, the Dog, the Triple Tunne". All of them, including those like Herrick whose accomplishments in verse are generally regarded as superior to Jonson's, took inspiration from Jonson's revival of classical forms and themes, his subtle melodies, and his disciplined use of wit. In these respects, Jonson may be regarded as among the most important figures in the prehistory of English neoclassicism

Neoclassicism, also spelled Neo-classicism, emerged as a Western cultural movement in the decorative arts, decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiq ...

.

The best of Jonson's lyrics have remained current since his time; periodically, they experience a brief vogue, as after the publication of Peter Whalley's edition of 1756. Jonson's poetry continues to interest scholars for the light which it sheds on English literary history, such as politics, systems of patronage and intellectual attitudes. For the general reader, Jonson's reputation rests on a few lyrics that, though brief, are surpassed for grace and precision by very few Renaissance poems: " On My First Sonne"; " To Celia"; "To Penshurst"; and the epitaph on Salomon Pavy, a boy player

A boy player was a male child or teenager who performed in Medieval theatre, Medieval and English Renaissance theatre, English Renaissance playing companies. Some boy players worked for adult companies and performed the female roles, since women ...

abducted from his parents who acted in Jonson's plays.

Jonson's works

Plays

* ''A Tale of a Tub

''A Tale of a Tub'' was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. The ''Tale'' is a prose parody divided into sections of "digression" and a "tale" of three brothers, each representin ...

'', comedy ( revised performed 1633; printed 1640)

* '' The Isle of Dogs'', comedy (1597, with Thomas Nashe; lost)

* '' The Case is Altered'', comedy (–98; printed 1609), possibly with Henry Porter and Anthony Munday

* '' Every Man in His Humour'', comedy (performed 1598; printed 1601)

* '' Every Man out of His Humour'', comedy (performed 1599; printed 1600)

* '' Cynthia's Revels'' (performed 1600; printed 1601)

* '' The Poetaster'', comedy (performed 1601; printed 1602)

* '' Sejanus His Fall'', tragedy (performed 1603; printed 1605)

* '' Eastward Ho'', comedy (performed and printed 1605), a collaboration with John Marston and George Chapman

George Chapman ( – 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman is seen as an anticipator of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. He is ...

* '' Volpone'', comedy (–06; printed 1607)

* '' Epicoene, or the Silent Woman'', comedy (performed 1609; printed 1616)

* '' The Alchemist'', comedy (performed 1610; printed 1612)

* '' Catiline His Conspiracy'', tragedy (performed and printed 1611)

* '' Bartholomew Fair'', comedy (performed 31 October 1614; printed 1631)

* '' The Devil is an Ass'', comedy (performed 1616; printed 1631)

* ''The Staple of News

''The Staple of News'' is an early Literature in English#Caroline and Cromwellian literature, Caroline era play, a satire by Ben Jonson. The play was first performed in late 1625 by the King's Men (playing company), King's Men at the Blackfriars ...

'', comedy (completed by Feb. 1626; printed 1631)

* '' The New Inn, or The Light Heart'', comedy (licensed 19 January 1629; printed 1631)

* '' The Magnetic Lady, or Humours Reconciled'', comedy (licensed 12 October 1632; printed 1641)

* '' The Sad Shepherd,'' pastoral (, printed 1641), unfinished

* '' Mortimer His Fall'', history (printed 1641), a fragment

Masques

* '' The Coronation Triumph'', or ''The King's Entertainment'' (performed 15 March 1604; printed 1604); with Thomas Dekker * ''A Private Entertainment of the King and Queen on May-Day (The Penates)'' (1 May 1604; printed 1616) * '' The Entertainment of the Queen and Prince Henry at Althorp (The Satyr)'' (25 June 1603; printed 1604) * '' The Masque of Blackness'' (6 January 1605; printed 1608) * '' Hymenaei'' (5 January 1606; printed 1606) * '' The Entertainment of the Kings of Great Britain and Denmark (The Hours)'' (24 July 1606; printed 1616) * '' The Masque of Beauty'' (10 January 1608; printed 1608) * '' The Masque of Queens'' (2 February 1609; printed 1609) * '' The Hue and Cry After Cupid'', or ''The Masque at Lord Haddington's Marriage'' (9 February 1608; printed ) * '' The Entertainment at Britain's Burse'' (11 April 1609; lost, rediscovered 1997) * '' The Speeches at Prince Henry's Barriers'', or ''The Lady of the Lake'' (6 January 1610; printed 1616) * '' Oberon, the Faery Prince'' (1 January 1611; printed 1616) * '' Love Freed from Ignorance and Folly'' (3 February 1611; printed 1616) * '' Love Restored'' (6 January 1612; printed 1616) * ''A Challenge at Tilt, at a Marriage'' (27 December 1613/1 January 1614; printed 1616) * '' The Irish Masque at Court'' (29 December 1613; printed 1616) * '' Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists'' (6 January 1615; printed 1616) * '' The Golden Age Restored'' (1 January 1616; printed 1616) * '' Christmas, His Masque'' (Christmas 1616; printed 1641) * '' The Vision of Delight'' (6 January 1617; printed 1641) * '' Lovers Made Men'', or ''The Masque of Lethe,'' or ''The Masque at Lord Hay's'' (22 February 1617; printed 1617) * '' Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue'' (6 January 1618; printed 1641) The masque was a failure; Jonson revised it by placing the anti-masque first, turning it into: * '' For the Honour of Wales'' (17 February 1618; printed 1641) * '' News from the New World Discovered in the Moon'' (7 January 1620: printed 1641) * ''The Entertainment at Blackfriars, or The Newcastle Entertainment'' (May 1620?; MS) * '' Pan's Anniversary, or The Shepherd's Holy-Day'' (19 June 1620?; printed 1641) * '' The Gypsies Metamorphosed'' (3 and 5 August 1621; printed 1640) * '' The Masque of Augurs'' (6 January 1622; printed 1622) * '' Time Vindicated to Himself and to His Honours'' (19 January 1623; printed 1623) * '' Neptune's Triumph for the Return of Albion'' (26 January 1624; printed 1624) * '' The Masque of Owls at Kenilworth'' (19 August 1624; printed 1641) * '' The Fortunate Isles and Their Union'' (9 January 1625; printed 1625) * '' Love's Triumph Through Callipolis'' (9 January 1631; printed 1631) * '' Chloridia: Rites to Chloris and Her Nymphs'' (22 February 1631; printed 1631) * '' The King's Entertainment at Welbeck in Nottinghamshire'' (21 May 1633; printed 1641) * '' Love's Welcome at Bolsover'' (30 July 1634; printed 1641)Other works

* ''Epigrams'' (1612) * ''The Forest'' (1616), including ''To Penshurst'' * ''On My First Sonne'' (1616), elegy * ''A Discourse of Love'' (1618) * Barclay's '' Argenis'', translated by Jonson (1623) * ''The Execration against Vulcan'' (1640) * ''Horace's Art of Poetry'', translated by Jonson (1640), with a commendatory verse by Edward Herbert * ''Underwood'' (1640) * ''English Grammar'' (1640) * ''Timber, or Discoveries made upon men and matter, as they have flowed out of his daily readings, or had their reflux to his peculiar notion of the times'', (London, 1641) a commonplace book * '' To Celia'' ''(Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes)'', poem It is in Jonson's ''Timber, or Discoveries...'' that he famously quipped on the manner in which language became a measure of the speaker or writer: As with other English Renaissance dramatists, a portion of Ben Jonson's literary output has not survived. In addition to '' The Isle of Dogs'' (1597), the records suggest these lost plays as wholly or partially Jonson's work: ''Richard Crookback'' (1602); ''Hot Anger Soon Cold'' (1598), with Porter and Henry Chettle; ''Page of Plymouth'' (1599), with Dekker; and ''Robert II, King of Scots'' (1599), with Chettle and Dekker. Several of Jonson's masques and entertainments also are not extant: ''The Entertainment at Merchant Taylors'' (1607); ''The Entertainment at Salisbury House for James I'' (1608); and ''The May Lord'' (1613–19). Finally, there are questionable or borderline attributions. Jonson may have had a hand in '' Rollo, Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother'', a play in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators. The comedy '' The Widow'' was printed in 1652 as the work of Thomas Middleton, Fletcher and Jonson, though scholars have been intensely sceptical about Jonson's presence in the play. A few attributions of anonymous plays, such as '' The London Prodigal'', have been ventured by individual researchers, but have met with cool responses.In fiction

Ben Johnson features as a character in Jean Findlay's historical novel, ''The Queen's Lender'' (2022).Findlay, Jean (2022), ''The Queen's Lender'', Scotland Street Press, Edinburgh,Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* . * . * . * * Chute, Marchette. ''Ben Jonson of Westminster.'' New York: E.P. Dutton, 1953 * * Doran, Madeline. ''Endeavors of Art''. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1954 * Eccles, Mark. "Jonson's Marriage." ''Review of English Studies'' 12 (1936) * Eliot, T. S. "Ben Jonson." ''The Sacred Wood''. London: Methuen, 1920 * Jonson, Ben. ''Discoveries 1641'', ed. G. B. Harrison. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966 * Jonson, Ben, David M. Bevington, Martin Butler, and Ian Donaldson. 2012. The Cambridge edition of the works of Ben Jonson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Knights, L. C. ''Drama and Society in the Age of Jonson''. London: Chatto and Windus, 1968 * Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith. ''The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama.'' Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 1975 * MacLean, Hugh, editor. ''Ben Jonson and the Cavalier Poets''. New York: Norton Press, 1974 * Ceri Sullivan, ''The Rhetoric of Credit. Merchants in Early Modern Writing'' (Madison/London: Associated University Press, 2002) * Teague, Frances. "Ben Jonson and the Gunpowder Plot." ''Ben Jonson Journal'' 5 (1998). pp. 249–52 * Thorndike, Ashley. "Ben Jonson." ''The Cambridge History of English and American Literature''. New York: Putnam, 1907–1921 * *Further reading

* Martin Butler & Jane Rickard (eds.). ''Ben Jonson and Posterity: Reception, Reputation, Legacy (Cambridge University Press, 2022) * D. H. Craig (ed.). ''Ben Jonson: The Critical Heritage'' (Routledge, 1990) * Ian Donaldson. ''Ben Jonson: A Life'' (Oxford University Press, 2011) * Douglas Duncan. ''Ben Jonson and the Lucianic Tradition'' (Cambridge University Press, 1979) * Richard Harp & Stanley Stewart (eds.). ''The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson'' (Cambridge University Press, 2000) * W. David Kay. ''Ben Jonson: A Literary Life'' (Macmillan, Basingstoke 1995) * Tom Lockwood. ''Ben Johnson in the Romantic Age'' (Oxford University Press, 2005) * Lynn S. Meskill. ''Ben Jonson and Envy'' (Cambridge University Press, 2009) * Rosalind Miles. ''Ben Jonson: His Craft and Art'' (Routledge, London 2017) * Rosalind Miles. ''Ben Jonson: His Life and Work'' (Routledge, London 1986) * George Parfitt. ''Ben Jonson: Public Poet and Private Man'' (J. M. Dent, 1976) * Richard S. Peterson. ''Imitation and Praise in the Poems of Ben Jonson'' (Routledge, 2011) * David Riggs. ''Ben Jonson: A Life'' (1989) * Stanley Wells. ''Shakespeare & Co.'' (Allen Lane, 2006)External links

* * *The Cambridge edition of the works of Ben Jonson

* Digitised Facsimiles of Jonson's second folio, 1640/

Jonson's second folio, 1640/1

* Video interview with scholar David Bevingto

The Collected Works of Ben Jonson

Audio resources on Ben Jonson at TheEnglishCollection.com